1. Introduction

Plastics are lightweight, durable, and inexpensive materials produced on a massive scale for applications ranging from packaging and construction, to transportation, recreation, and medicine [

1]. They provide diverse benefits, including food preservation, fuel savings, improved healthcare, and access to clean water [

2]. However, most plastics are derived from fossil fuel-based polymers that resist degradation, persisting in the environment for centuries. Global plastic production now exceeds 400 million tonnes annually, with a substantial fraction entering aquatic environments [

3,

4]. Recent studies indicate that plastic concentrations in some freshwater lakes, including the North American Great Lakes, can surpass those found in oceanic gyres, underscoring the significance of freshwater systems as significant sinks for plastic debris [

3,

5]. Growing awareness of plastic pollution has prompted regulatory action. The United States enacted the Microbead-Free Waters Act in 2015, with a prohibition on plastic microbeads in personal care products taking effect on July 1, 2017. In 2018, Canada enacted a ban on single-use plastics, accompanied by a prohibition on the manufacture and sale of microbeads in toiletries (Single-use Plastics Prohibition Regulations - Technical guidelines) [

6]. In addition to bans, strategies such as improved recycling, ecolabelling, behavioural interventions, and biotechnological innovations are being explored to mitigate microplastic pollution [

7,

8,

9]. Continued research and monitoring are essential to track contamination trends and inform adaptive management of freshwater ecosystems [

5,

10]. This review synthesizes data on microbead accumulation in the Canadian Great Lakes prior to the ban between 2013 and 2017, providing a baseline for future assessments of regulatory effectiveness, and presents new data from samples collected in the same region after the ban, between 2018 and 2021.

Plastics encompass a family of petroleum-derived polymers, including polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene terephthalate (PETE), and polyurethane (PU) [

11]. Macroplastics are defined as >5 mm, microplastics as <5 mm, and nanoplastics as <100 nm [

12]. Microplastics comprise up to 92% of plastic debris at the ocean surface [

13], and can be categorized by shape, size, and origin. Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured at micro-scale, including microbeads and virgin pellets, while secondary microplastics result from the breakdown of larger items [

14]. Sources include wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), industrial facilities, and diffuse runoff from urban, agricultural, and industrial areas [

15]. Although WWTPs remove most larger microplastics, smaller particles often escape, contributing to downstream contamination [

16,

17]. Most plastic accumulates first in landfills or on surface environments, then can later partition into soils, freshwater systems, and eventually oceans [

1], with lakes and rivers serving as the most important microplastic carrier pathways [

18]. Microplastics are now ubiquitous in terrestrial and aquatic environments, including remote regions such as the Arctic and far-north Canadian lakes [

1,

10,

11,

18,

20,

21]. Their distribution correlates with population density and anthropogenic activity [

21]. In freshwater, microplastics have been detected in surface waters, sediments, and biota, with concentrations in Great Lakes tributaries ranging from 0.05 to 32 items per cubic meter [

22]. Factors such as polymer type, density, and environmental conditions influence their fate and impact [

1,

10,

17,

23]. For example, low-density plastics (PP, LDPE) are buoyant, while high-density types (PVC, PS, HDPE, PA) tend to accumulate in sediments [

11].

Microplastics can act as vectors for hazardous chemicals and microbial communities, posing risks to ecosystems and human health [

18]. Human exposure to microplastics occurs via ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact, with recent estimates suggesting adults consume over 300,000 microplastic particles annually, leading to an irreversible accumulation of 8,000 to 50,000 particles in the body [

24,

25]. Microplastics can carry persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which may leach upon ingestion [

25,

26,

27]. The surface chemistry of microplastics, especially after environmental aging, becomes more reactive, enhancing their ability to carry and release pollutants [

22,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Animal studies indicate microplastics can cross biological barriers and exert toxic effects on development, reproduction, and immune function [

26,

27]. In aquatic organisms, microplastics disrupt feeding, growth, and reproduction, and can bioaccumulate across trophic levels [

21,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Microbeads, a subset of primary microplastics, have attracted particular attention due to their deliberate inclusion in personal care and cleaning products [

31,

32,

33]. Typically ranging from 10 μm to 5 mm, microbeads are most commonly composed of PE, but may also include PP, PETE, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), and nylon [

31]. Their physical properties influence environmental behaviour and detection, with studies noting significant underestimation of microbead abundance due to variability in size and colour [

34].

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of various microbeads extracted from personal care products [

32].

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of various microbeads extracted from personal care products [

32].

This paper reviews ten representative studies conducted across the five Great Lakes between 2013 and 2017, providing a comprehensive overview of microbead pollution prior to the 2018 Canadian ban on microbeads in personal care products. Additionally, we present new data from sampling locations downstream of the Great Lakes, collected between 2018 and 2021, to offer an assessment of post-ban microbead accumulation. The sampling regions include remote rivers in Quebec, the Ottawa River, and the St. Lawrence Seaway at Montreal, to assess microplastic and microbead contamination across contrasting environments.

2. Household Use of Plastic Microbeads and Disposal in Wastewater

Microbeads are intentionally designed for disposal down household drains, providing a uniquely direct pathway for their entry into freshwater systems [

35]. A 2017 study estimated that at least 8 trillion microbeads were released daily into aquatic environments via effluent in the United States, with residents of New York State alone washing approximately 20 tonnes of microbeads down the drain each year [

36]. Once rinsed down the drain, microbeads enter municipal water collection systems and subsequently wastewater treatment plants, where wastewater undergoes a series of filtration, sedimentation, and chemical treatment processes. However, there are inherent limitations to these filtration systems: employing mesh sizes fine enough to capture microbeads would result in clogging and unacceptable reductions in flow rates. During physical treatment, wastewater is allowed to settle in tanks to reduce turbulence, facilitating the separation of sludge and other heavy suspended solids from the lighter liquid effluent [

13,

34]. This process is generally effective at removing larger and denser contaminant particles. Studies have shown that up to 95–99.9% of microbeads can be trapped in the resulting sludge [

37,

38], but a fraction still escapes into the effluent. The efficiency of microbead removal is strongly influenced by the density of the polymer used in their manufacture, making polymer selection a critical factor. The accumulation of microbeads in sludge is particularly concerning, as this sludge is often applied as fertilizer to agricultural land, creating a secondary contamination pathway. Through this practice, microbeads are introduced into soils, where they can persist and disperse for decades, resulting in long-term, uncontrolled environmental contamination [

39,

40,

41].

Legislative measures in North America targeting microbead use include the U.S. Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015, which prohibits the manufacture and interstate commerce of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics intended for exfoliation or cleansing, and Canada’s Single-use Plastics Prohibition Regulations, which ban the manufacture and sale of microbeads in toiletries as of 2018. These laws specifically address primary microplastics intentionally added to personal care products, but do not cover other sources such as industrial abrasives, cleaning products, or microbeads already present in the environment, including those found in sewage sludge and agricultural soils [

42]. Environmental monitoring studies conducted after the implementation of these bans have reported decreased detection of microbeads, indicating that the legislation has successfully reduced new inputs of microbeads into freshwater systems [

42]. Nevertheless, the persistence of legacy microbeads and the continued use of products not covered by current legislation remain ongoing challenges.

3. Microbead Composition and Degradation

The vast majority of commercially produced microbeads are composed of petroleum-derived polymers, with polyethylene (PE) accounting for approximately 93% of those found in cosmetic products [

31]. Other polymers, such as polystyrene (PS) and polyurethane (PU), are also present but in much smaller proportions. The physical characteristics of microbeads, including their size, shape, and surface topography, play a significant role in their environmental fate. For example, rougher PE microbeads have a higher capacity to adsorb organic pollutants compared to smoother ones, which can influence their ecological impact [

43]. Once microbeads enter the environment, usually through wastewater effluent, their behavior is largely dictated by their density relative to freshwater. Most commodity plastics used for microbeads, such as PE, PS, and PU, have densities close to or slightly above that of freshwater, causing them to sink slowly or remain suspended. This property makes them difficult to remove during conventional wastewater treatment and facilitates their accumulation in aquatic environments like the Great Lakes. Polypropylene (PP) is an exception, as it is less dense than water and tends to float, but it is less commonly used in microbeads [

44,

45].

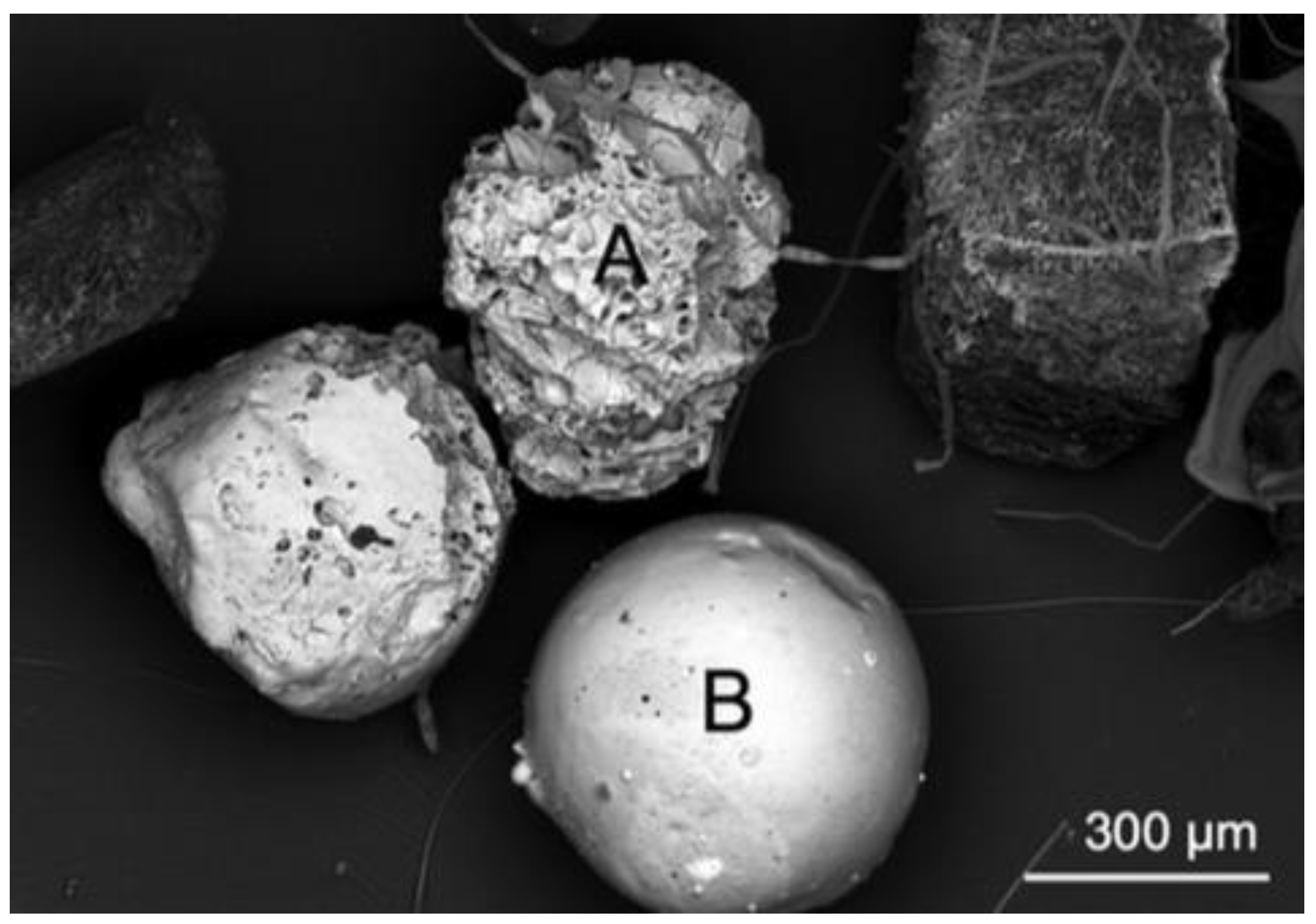

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy images of PE pellets found in commercially available face washes: (

a) Rough topography microbead pellet; (

b) surface microbead topography; (

c) cracked smooth spherical microbead pellet [

34].

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy images of PE pellets found in commercially available face washes: (

a) Rough topography microbead pellet; (

b) surface microbead topography; (

c) cracked smooth spherical microbead pellet [

34].

The degradation of conventional microbeads in the environment is extremely slow. These oil-derived polymers lack natural chemical or biological degradation pathways; their primary breakdown mechanism is photodegradation, which occurs when deep-blue visible and ultraviolet sunlight excites the polymer molecules, leading to the slow decomposition of molecular bonds. The spherical shape of microbeads, which results in a low surface area-to-volume ratio, further slows this process, allowing them to persist in the environment for extended periods. Some studies have indicated that certain microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, worms, and biofilms, may contribute to the degradation of plastics, but these processes are not yet significant for conventional microbeads in natural environments [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Recent advances in materials science have enabled the development of biodegradable microbeads made from natural polymers such as starch, cellulose, chitosan, and polylactic acid (PLA). These materials are capable of breaking down through natural chemical or biological processes in both aquatic and terrestrial environments, offering a significant potential to reduce the environmental persistence associated with traditional petroleum-derived plastic microbeads [

51,

52,

53]. However, the widespread commercial adoption of these biodegradable alternatives is currently limited by higher production costs and challenges in achieving the same mechanical strength, stability, and scalability as conventional polyethylene-based microbeads [

54].

4. Great Lakes Regions Studied

The Laurentian Great Lakes—Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario—form the largest contiguous surface freshwater system on Earth, containing approximately 21% of the world’s surface fresh water and 84% of North America’s surface freshwater resources [

55,

56]. These lakes, created by glacial activity during the Pleistocene epoch, span roughly 95,000 square miles (245,000 km²) and their drainage basin encompasses significant portions of both the United States and Canada [

57,

58,

59] Hydrologically, Lake Superior drains into Lake Huron, which then flows into Lake Erie and subsequently Lake Ontario; Lake Michigan, although entirely within the United States, is connected to Lake Huron via the Straits of Mackinac and shares a common water level, functioning as a single hydrological unit with Lake Huron [

59]. The system ultimately discharges into the Atlantic Ocean through the St. Lawrence Seaway.

The Great Lakes basin supports a population exceeding 40 million, providing drinking water to about 10% of the U.S. population and over 30% of the Canadian population [

58,

60]. Beyond potable water, the lakes supply an average of 56 billion gallons daily for agricultural, municipal, and industrial purposes, underpinning the region’s economic vitality [

59]. The lakes’ vast expanse, sea-like features, including strong currents, significant wave action, and considerable depths, and proximity to major urban and industrial centers contribute to their ecological and economic importance, supporting the world’s largest freshwater fishery and extensive recreational activities [

56,

57,

60].

Each of the Great Lakes has unique characteristics with respect to size, morphology, hydrological retention time, and patterns of waste effluent inflow, that significantly influence the distribution and accumulation of microbead pollution. Studies in other lake systems have shown that factors like watershed-to-surface area ratio, urban development, and land use are major drivers of microplastic concentrations, with higher levels found in lakes with larger watersheds and more urbanized catchments [

61,

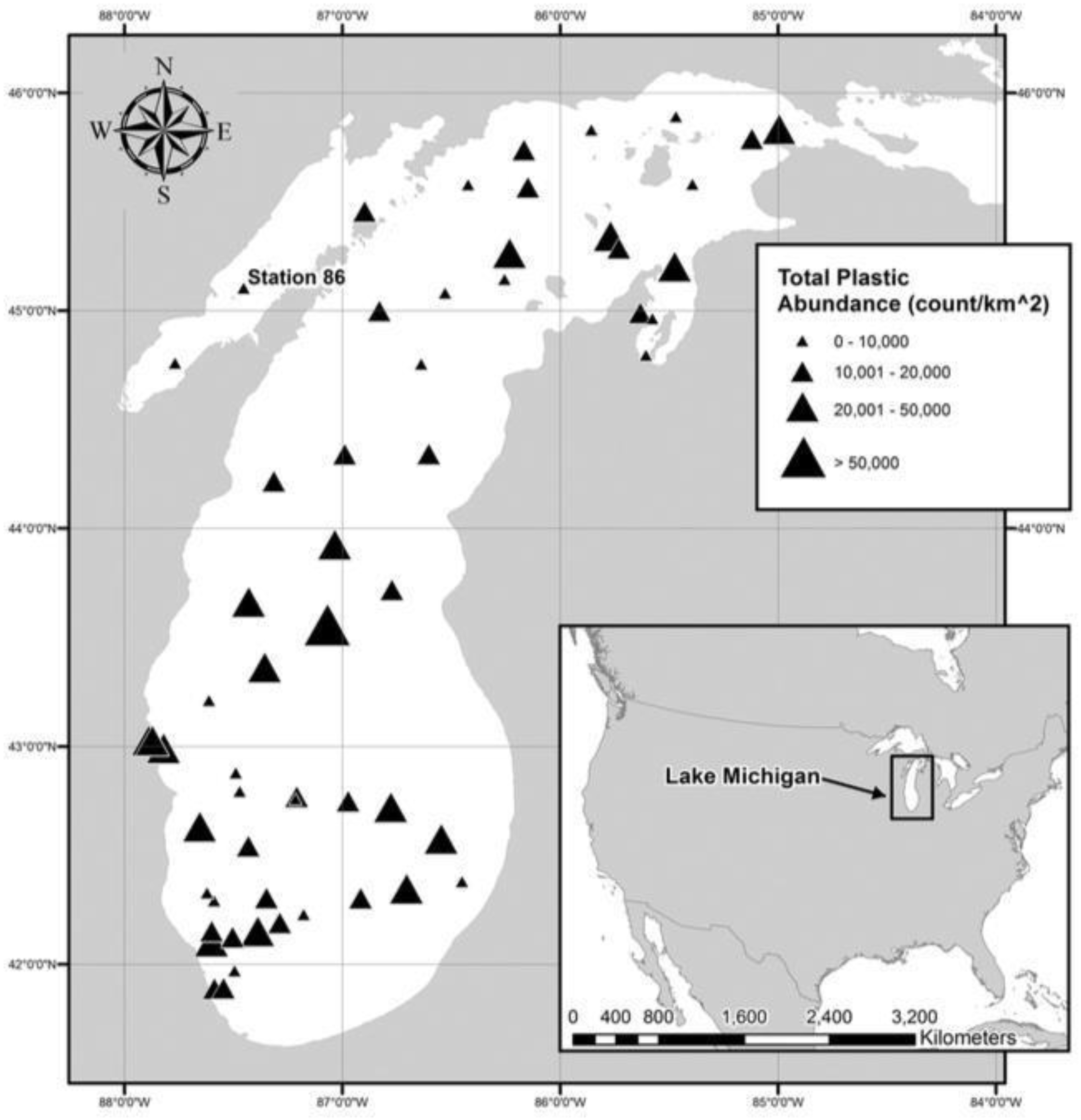

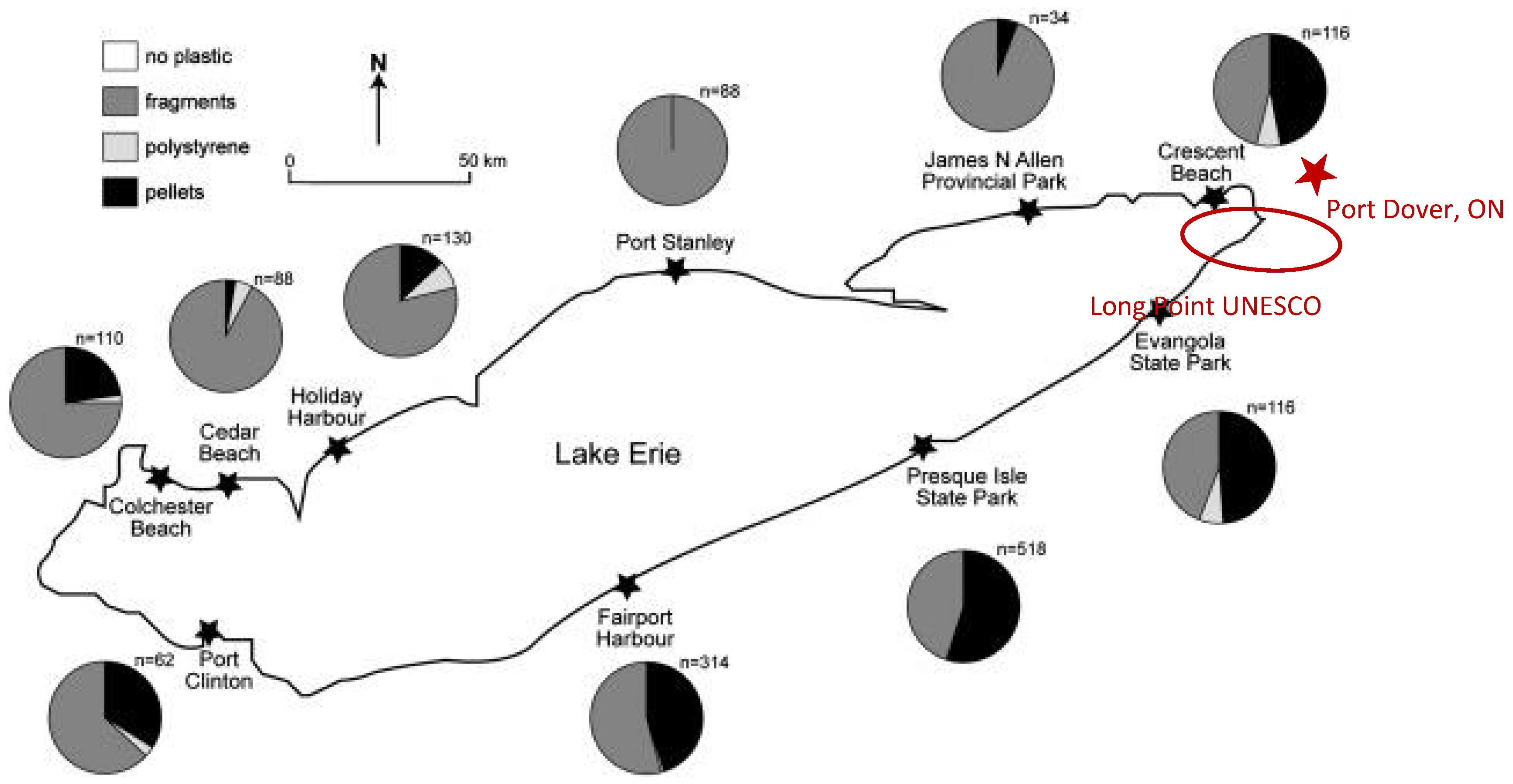

62]. This variability underscores the necessity for spatially distributed sampling across all five Great Lakes to accurately capture the scope and sources of microbead contamination. For these reasons, this paper reviews data from 10 major studies conducted across the five Great Lakes between 2013 and 2017, along with additional samples collected and analysed by the authors in 2018 and 2019 near Montreal, Quebec, at the outflow, and in 2020 and 2021 in Long Point Bay on Lake Erie. The map in

Figure 3 displays the location of the studies, which together represents geographically and methodologically diverse sampling area to understand the full extent of microplastic pollution in large and complex lake systems [

63,

64].

In 2013, Erisksen et al. conducted to test for microplastic pollution in the surface waters of Lake Superior, Lake Huron and Lake Erie [

65]. The expedition began in Lake Superior and ended in Lake Erie, extracting five samples from the former and eight from the latter and Lake Huron. In 2014, three notable studies were conducted in different regions of the Great Lakes in Canada. Castañeda et al. conducted a study of microplastic pollution in the St. Lawrence River, testing sediment specifically at ten different sites along the river [

66]. Notably, four of these sites were located downstream of municipal or industrial plants, and one was located downstream of a nuclear power plant. Across the border in the U.S., a similar study by McCormick et al. was undertaken in the North Shore Channel in Chicago, which links Lake Michigan with the Mississippi River [

67]. This channel also contains several wastewater treatment plants along its stretch. Finally, a third study was conducted in 2014 by Zbyszewski et al., but this time widely surveying a number of the Great Lakes [

68], including Lake Huron, Lake Erie, and smaller Lake St. Clair that connects them and that also makes up part of the Great Lakes system. In 2015, Lake Ontario, more specifically the Humber Bay region near metropolitan Toronto, was tested for plastic pollution by Corcoran et al. [

69]. Samples were taken from the beach, along the bank of the Humber River, and from the lake sediment. In 2016, Ballent et al. tested Lake Ontario again, this time sampling from nearshore, tributary, beach sediment, and even parts of the St. Lawrence River connected to the lake [

45]. A more extensive study was conducted by Baldwin et al., sampling from 29 of the Great Lakes tributaries, spanning six different states and accounting for 22% of total tributary contribution to the Great Lakes [

22]. This report included a map highlighting the tributaries sampled, and went further to indicate the uses of the tributaries in the different states, shown in

Figure 4. Finally, in 2016, Mason et al. examined plastic pollution in the surface waters of Lake Michigan, in the lake’s open water and at a variety of sites on the lake, as is identified in

Figure 5 [

70].

Cable et al. examined the distribution of microplastic pollution across 38 different stations in the surface waters of Lake Superior, Lake Huron, Lake St. Clair, and Lake Erie [

71]. In a second study finished in 2017, Vermaire et Al. observed microplastic pollution in the Ottawa River (draining much of Eastern Ontario and flowing into the St. Lawrence River at Montreal) and several of its tributaries, from the water column and surface water [

72]. Finally, our studies conducted in the summers of 2018–2021 examined microplastic abundance observed in Long Point Bay Biosphere of Lake Erie, and across 29 sampling sites in the surface waters of the Kenauk Nature Reserve, a large human-free protected wilderness watershed area in Quebec whose rivers empty into the Ottawa River near the village of Montebello; secondly, the Ottawa River, downstream from habitat for approx. 1–2 million humans; and lastly in the St. Lawrence River, which drains the entire Great Lakes Region, home to more than 40 million human inhabitants in the United States and Canada.

5. Techniques Used for Water Sampling

One of the largest challenges facing direct comparisons between various field studies is the use of diverse field sampling techniques, lab methods, and measurement units [

73]. Sampling methods from surface waters include pumping, trawling, or filling bottles or buckets, followed by sieving to isolate particles of the desired size [

74]. Each studies included in this review used sampling techniques similar to at least one other study. The most commonly used technique was the manta trawl [

75], which is specifically engineered for surface sampling, featuring a rectangular mouth with stabilizing wings that keep the net consistently at the water’s surface. This design ensures that the manta trawl skims only the top few centimeters of the water column, where floating microplastics and microbeads are most concentrated [

65,

70,

71,

72]. The mesh size of the net can vary, with the largest and most common being 0.333 mm [

75]. After collection, manta trawl nets are rinsed into a vial that is then brought to the laboratory for further inspection. Two studies included in this review used neuston nets to collect samples: one in some of the tributaries of the Great Lakes watershed [

22], and the other in the North Shore Channel in Chicago [

67]. Neuston nets are similar in theory to manta trawls, but are more general-purpose surface nets, often with a rectangular or trapezoidal opening but lacking the specialized flotation and wing system of the manta trawl. As a result, the neuston net may dip below the surface or ride higher depending on water conditions and towing speed, potentially sampling a slightly deeper or more variable layer of water [

76]. However, neuston nets allow access to shallower waters as they can be used manually, which would not be possible with the use of only manta trawls, thus providing a better geographically unrestricted representation of microplastic, and effectively microbead, concentration in fresh water.

Three of the studies reviewed focused on microplastics found present in sediment, therefore requiring different sampling techniques. The study conducted along the St. Lawrence River used a combination of two sample collection techniques: first with a petite ponar grab, then with a Peterson grab [

65]. The former allows for sampling of depths up to 10 cm, while the latter allows for sampling further to depths of 15 cm. The second study, published two years later, extracts sediment samples using a petite ponar grab and stainless steel split spoon corer [

45]. Samples that were taken from shallower depths were completed using a Glew gravity corer and a Shipek grab sampler. The final study included sediment sampling and used a mini box corer at different depths of Lake Ontario: one closer to shore, and the other in a deeper, more central location [

69]. Finally, two of the studies collected plastic from land, on the beaches of several Great Lakes. Collection was carried out by simply measuring out a quadrant and taking samples to later be inspected in the lab [

68,

69]. One of the studies specified the instrument used to collect plastic debris on the beach: a stainless steel trowel [

68].

In general, analyzing microplastics from aquatic or sediment samples involves separation from organic matter, microscopic visual observation, and chemical analysis [

77]. Separation from organic matter is normally accomplished with acidic, oxidative, alkaline, or enzymatic digestion using chemicals such as hydrogen peroxide, sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, or potassium hydroxide [

78]. Other methods include density separation [

79], and oil extractions that take advantage of the oleophilic properties of plastics [

80]. The latter methods can offer some benefits, in that they do not cause discolouration or physical alteration of plastic particles as does acid digestion, which can render visual assessment difficult [

81]. Further laboratory treatment was generally similar across all studies reviewed, following the procedure outlined by Ballent et al. [

45], in which samples were dried, weighed, and sieved several times through filters of varying mesh sizes to divide plastics into size classes [

81]. Further separation can be accomplished with a procedure based on density, for example, separating plastic that floats from plastic that sinks [

45]. Microplastics can then be further examined for chemical composition and by morphology. The wet peroxide oxidation technique is used to remove organic material from microplastic so it can be observed under a variety of microscopes, including stereo microscopes, which allow microplastics to be more easily quantified and separated into different morphology types.

Following extraction, microplastics can be identified with light microscopy and visual sorting [

79]. Visual keys often describe identifying microplastics based on the absence of organic or cellular structures, homogeneity across particles, and consistent colours or gloss. While visual identification is quick and relatively available and inexpensive, it is prone to high error rates, so secondary analyses are often employed to confirm the polymer’s identity. Such analyses include the ‘hot needle test’, polarized light microscopy, thermal analytical techniques [

82], or more advanced chemical techniques, including vibrational spectroscopy, densitometry, and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry [

83]. Two major spectroscopic methods are FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) and Raman, both of which employ vibrational spectroscopy to obtain the frequency spectrum of a particle, specifically the tell-tale ‘fingerprint regions’, unique to each polymer’s molecular structure. Both methods exploit the fact that molecules absorb frequencies characteristic of their structure. A particle’s IR spectrum can thus be used to positively and conclusively identify the chemical polymer type of microplastic found [

78]. Across these studies, FTIR and Raman spectroscopy represent the most frequently used techniques to determine polymer composition [

45], while additionally, Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) has also been used successfully to assess composition of beads [

65].

6. Findings of the Great Lakes Studies

For studies focused on surface water and the upper water column, the most reliable comparison is through average abundances or concentrations of plastic particles per unit volume. However, because the reported volume units varied widely across studies, a practical alternative is to compare results by percentages, specifically, the proportion of microbead pellets or spheres relative to the total microplastics sampled. For comparison,

Table 1 presents these percentages of microbeads (also referred to as “pellets” in some studies), organized by study and year.

To draw meaningful conclusions, it is essential to consider both where and when samples were collected in each study (e.g., sediment, surface water). Accordingly, results are grouped and presented by the type of environment sampled. First, studies examining surface waters across the different Great Lakes will be compared. Next, findings from sediment samples will be reviewed, followed by those from shoreline and beach samples.

Table 1.

Percentage of microbeads reported in reviewed studies.

Table 1.

Percentage of microbeads reported in reviewed studies.

| Location of Study |

Percentage of Microbeads Found |

Year |

| Lake Ontario [65] |

shoreline 74%; sediment <6% |

2015 |

| St. Lawrence River [62] |

80% |

2014 |

| Ottawa River and Tributaries [68] |

6% |

2017 |

| Lake Superior, Huron, & Erie [61] |

48% |

2013 |

| Lake Michigan [66] |

4% |

2016 |

| 29 Great Lakes Tributaries [18] |

<2% |

2016 |

| North Shore Channel, Chicago [63] |

2.26% |

2014 |

| Lake Ontario [55] |

<10% |

2016 |

| Lake St. Clair & Erie [64] |

St. Clair – 13%; Erie – 39% |

2014 |

| Lakes Superior, Huron, St. Clair, & Erie [67] |

0.2% |

2017 |

From the study conducted by Erisksen et al. on the Great Lakes of Superior, Huron, and Erie in 2013, it was determined that approximately 48% of all plastic collected during sampling was composed of pellets, while non-spherical plastic fragments made up the other majority [

65]. In this study, it proved crucial to assess the composition, which was completed using electron dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM/EDS). What was at first identified as a microbead (particle labelled B) based on its size, shape, and colour, was found instead by chemical analysis to be coal fly ash, shown in

Figure 6. This distinction is important to consider in future studies, as the Great Lakes region has historically been subject to fallout from coal-fired electricity generation plants.

In contrast, both our study and other investigations of surface waters reported much lower contributions of pellets/microbeads than those observed in the 2013 study. All five of these subsequent studies were conducted after 2013, with reported percentages ranging from a high of 6% [

72] to 4% [

70], 2.26% [

67], less than 2% [

22], and as low as 0.2% [

71]. It is important to note that plastic pollution overall was significant; in every study, plastic was found in either all samples or all except for one. The discrepancy with the microbead percentages reported in the 2013 study on Lakes Superior, Huron, and Erie [

65] could be due to particles being misidentified as plastic microbeads, as described previously. Lake Erie is reported to be especially polluted with plastic debris, considering the multiple points of high population along its shore and relatively low volume compared to its neighbouring lakes. However, a study in 2017 by Cable et al. also sampling from Lake Erie [

71] reported the lowest of all concentrations of microbeads. A final possibility for this discrepancy could be inconsistent methodology used for both sampling and counting microbeads, which has been cited as an issue for comparison of studies. The depth of sampling, as well as more localized factors including water flow, could also explain the discrepancy, since microplastic fate heavily depends on properties such as density. Nonetheless, it is crucial to understand that the data reported above together comprise a consensus of a significant plastic microbead accumulation in these aquatic environments, and though pellets/microbeads may not make up a large percentage of plastic waste found, they still cause adverse effects to the ecosystem and represent a significant contribution to the already immense problem of plastic pollution in freshwater environments.

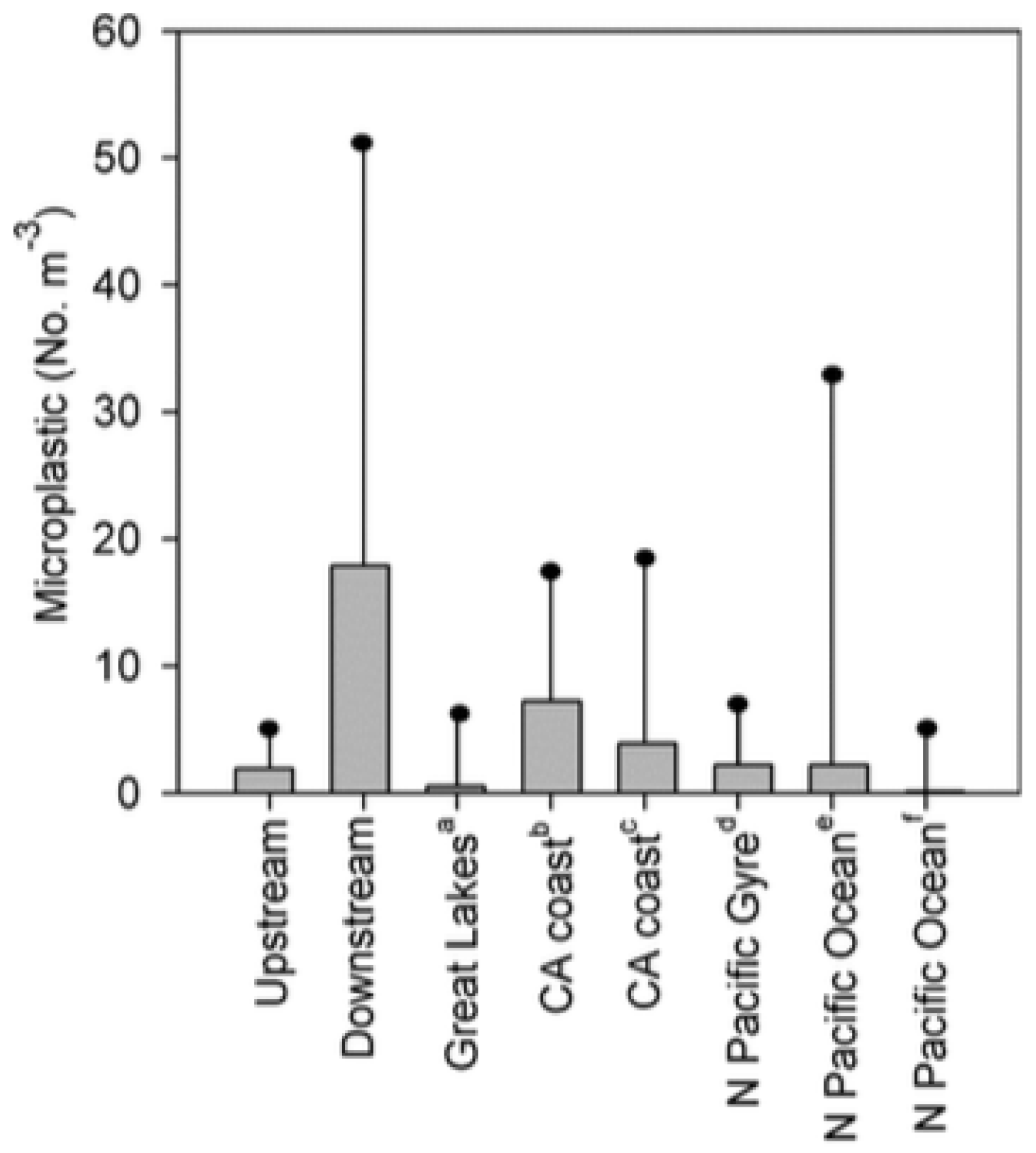

In one study by McCormick et al. focusing on the surface water of the North Shore Channel in Chicago [

67], the difference between surface water concentration of microplastic upstream of an urban wastewater treatment plant was compared with concentrations from downstream of the plant. Not only did pellet/microbead concentration increase from upstream to downstream locations, but overall microplastic concentration increased further downstream from the treatment plant. The study included a bar graph, which is reproduced here as

Figure 7, comparing the upstream and downstream microplastic absolute concentrations in the Great Lakes with the concentrations found off the California coast and in parts of the Pacific Ocean. Overall, a greater amount was found in the Great Lakes than in these ocean locales.

The data in

Figure 7 indicate that wastewater treatment plants can act as a direct and major route of plastic debris’s entrance into freshwater systems. The microplastic concentration upstream in the North Pacific Gyre shows that although wastewater treatment plants act as a source of entry, they are not the only conduit for plastics to enter the environment. Gyres are large systems of rotating ocean currents where ocean plastics have been shown to collect and accumulate, making them regions of some of the highest plastic concentrations observed in the ocean [

84]. The comparison of river microplastic concentrations to oceanic concentrations suggests that research must focus not only on plastic accumulation in oceans but also in freshwater systems, since freshwater has shown higher microplastic concentrations and is likely a major source of plastic debris in the ocean.

The studies that investigated microplastics in sediment did not consistently provide detailed breakdowns of the morphologies of all plastic particles extracted. Notably, a study conducted in the St. Lawrence River by Castañeda et al. focused exclusively on the presence of microbeads within sediment samples [

66]. Microbeads were detected at eight out of ten sampling sites, corresponding to an 80% recovery rate as summarized in

Table 1, with a mean density of approximately 13,800 microbeads per square meter of bottom surface area [

66].

Figure 8 visually documents the diversity of microbeads recovered from these sites, illustrating the range of shapes, sizes, colors, and transparencies present in sediment samples.

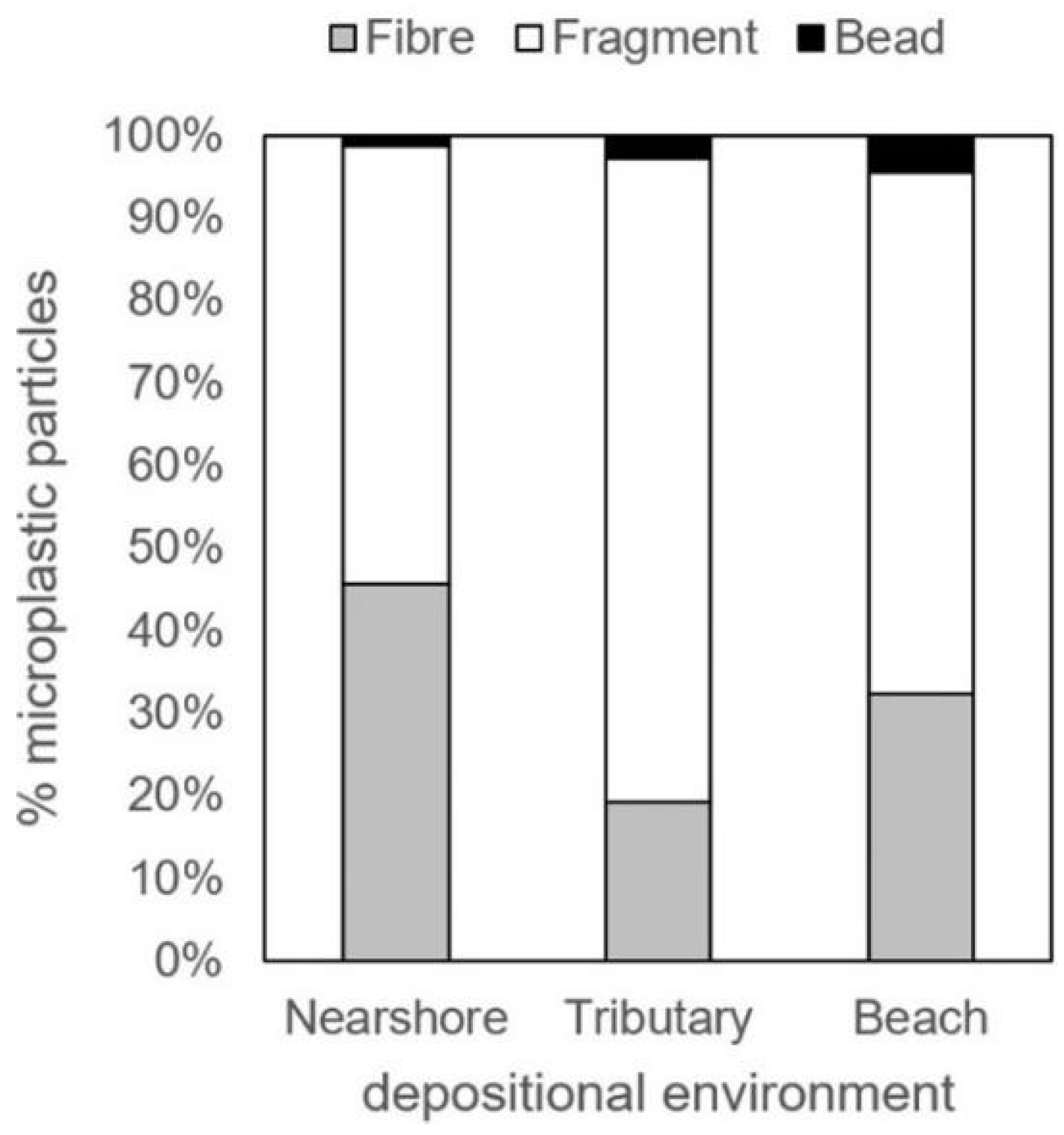

In contrast, the study by Ballent et al. examining microplastic pollution in sediments at various locations in Lake Ontario provided a more comprehensive comparison of microplastic types, with graphical data revealing the relative abundances of fibers, fragments, and beads at different sites [

45]. From these data, the average proportion of microbeads among total microplastics in Lake Ontario sediments was estimated to be less than 10% (see

Table 1).

Figure 9 further illustrates the comparative abundance of fibers, fragments, and beads across the three sediment sampling locations, highlighting the predominance of non-bead microplastic morphologies in these environments.

Figure 9 indicates that microbeads constitute only a small fraction of the total microplastics present in Lake Ontario sediments, with their highest abundance observed in beach sediments, where they likely represent no more than 5% of the extracted microplastic particles. Similarly, a 2015 study focusing on the Humber Bay region near Toronto reported low levels of microbeads or pellets in sediment samples [

70]. Specifically, only two out of 35 plastic particles identified in the sediment exhibited a "rounded" morphology characteristic of microbeads, corresponding to less than 6% of the total microplastics recovered. These findings suggest that microbeads are less prevalent in lake sediments compared to river sediments, where higher concentrations have been observed. This disparity may be linked to the proximity and capacity of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), which are more numerous and larger along the St. Lawrence River than near the Lake Ontario sampling sites. The interaction between WWTP effluent, hydrodynamic conditions, and sedimentation processes in riverine environments may facilitate greater microbead accumulation in river sediments compared to lakes. Collectively, these observations underscore the significant role of wastewater treatment plants as point sources of microbead pollution in freshwater environments.

We compared two studies that surveyed plastic debris on the beaches of the Great Lakes. In a 2014 investigation by Zbyszewski et al., sediments of varying composition (sandy, gravelly, and muddy) were sampled from beaches along Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair [

68]. The results revealed that pellets comprised 39% of the plastic debris recovered from Lake Erie beaches. Notably, the highest overall abundance of plastic debris, as well as some of the greatest concentrations of pellets, were observed along shorelines adjacent to the most densely populated areas, specifically Presque Isle (Erie, PA) and Fairport Harbor (Cleveland, OH). This spatial pattern is illustrated in

Figure 10, which presents the abundance of plastic debris (n) at each site and uses pie charts to depict the composition of debris types, with pellets indicated in black. These findings highlight the influence of population density and urban proximity on the distribution and composition of plastic debris, particularly microbead pellets, along Great Lakes shorelines

Approximately 13% of the plastic debris recovered from Lake St. Clair beaches consisted of pellets, a proportion notably lower than that reported in a previous study of Lake Huron beaches, where pellets accounted for 94% of the plastic debris. Similarly, in the initial phase of a study conducted on Lake Ontario by Corcoran et al., sampling of Humber Bay beach revealed that pellets were the dominant form of plastic debris, comprising 74% of all plastics collected [

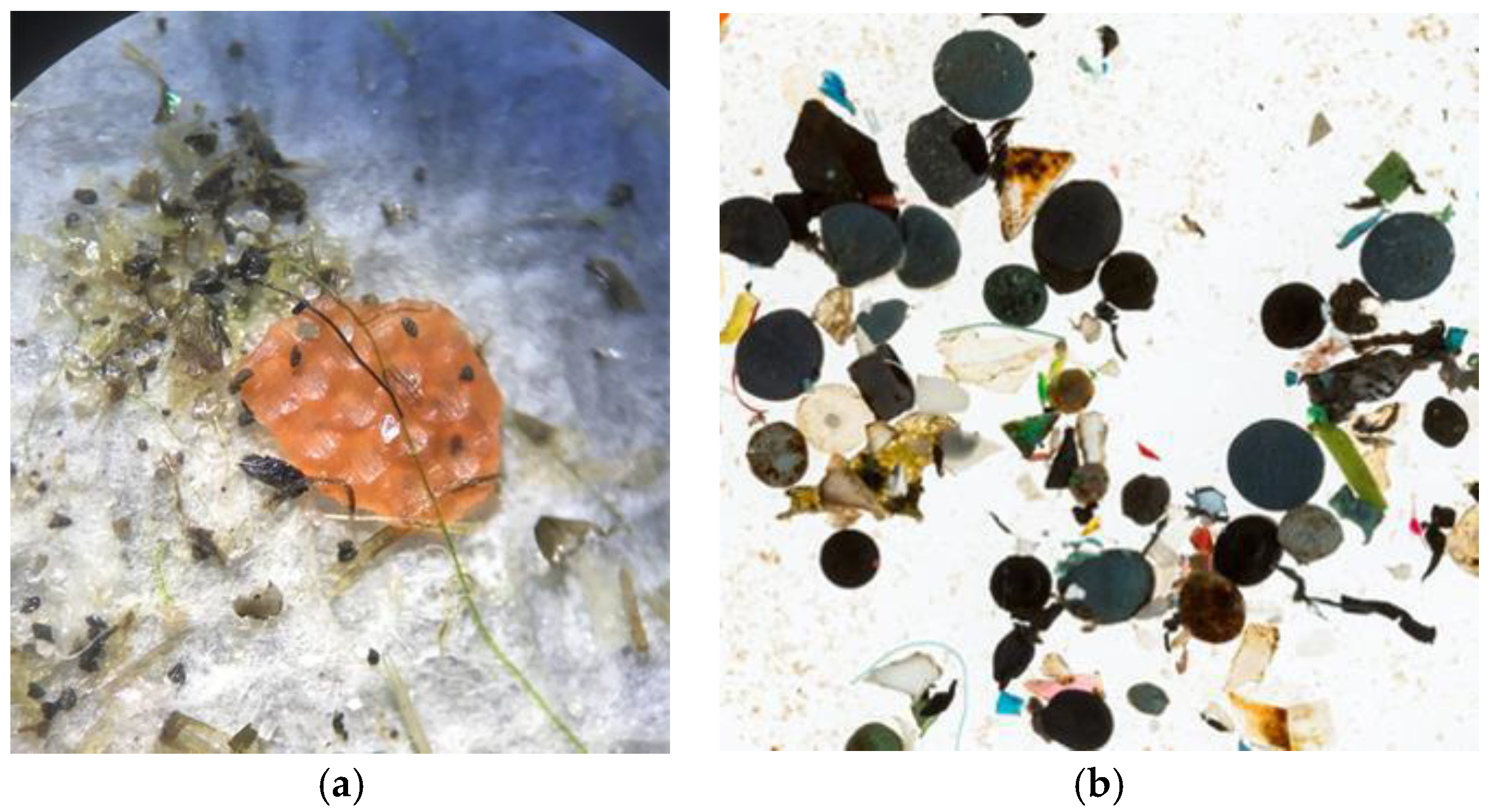

69]. Although Lake Erie is surrounded by densely populated urban areas on both the U.S. and Canadian sides, Long Point—a 40 km sandspit on the northern Canadian shore designated as a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve—offers a unique opportunity to study lake-derived plastic deposition with minimal direct human influence. Access to Long Point is restricted, limiting pedestrian and boat traffic, and thus reducing the likelihood of local contamination. Beach wash samples collected by kayak from locations such as Port Dover, Ontario (see

Figure 10), can therefore be considered representative of plastics deposited by lake currents rather than by visitors. In the next section,

Figure 11 presents a typical sample of microplastics recovered from these secluded beaches, with the identity of plastic microbeads confirmed through spectroscopic and NMR analysis (Chemistry Department, McGill University, Montreal).

The high proportion of microbeads and pellets found on lake beaches suggests that a significant fraction of these microplastics remain buoyant or suspended in the water column, which may explain their lower abundance in lake sediments compared to river sediments. The deposition of microplastics on shorelines is influenced by a range of factors, including particle size, shape, beach morphology, and hydrodynamic conditions such as water velocity, as well as recent wind, wave, and weather events. Despite this variability, studies consistently report the highest concentrations of plastic debris, including microbeads, on beaches adjacent to densely populated areas, which are typically served by a greater number of wastewater treatment plants. This spatial pattern underscores the critical role of wastewater treatment infrastructure in mitigating microbead pollution; effective capture of microbeads at these facilities is essential for reducing their environmental release. While the distribution of microbeads varies across shorelines, surface waters, and sediments, their persistent presence and accumulation in freshwater systems are well documented. Given their resistance to natural degradation, microbeads can persist in the environment for decades to centuries, posing long-term ecological risks. Population density and downstream transport are key drivers of microplastic abundance: for example, studies conducted at Fredonia in 2012 and 2013 estimated plastic particle densities of approximately 7,000 particles/km² in Lakes Superior and Huron, 17,000 in Lake Michigan, 46,000 in Lake Erie, and a striking 248,000 particles/km² in Lake Ontario, the most downstream and densely populated of the Great Lakes, with concentrations nearly 40 times higher than those observed in Lake Superior. These findings highlight the cumulative impact of urbanization and hydrological connectivity on microbead pollution in the Great Lakes basin.

7. Results of Downstream Study of 3 Contrasting Sample Locations Near Montreal

In the summer of 2018, the authors conducted a comprehensive sampling campaign within the Great Lakes watershed, focusing on regions downstream of the main lake system. Sampling was performed at 29 sites across three interconnected freshwater systems: (1) rivers and lakes within the Kenauk Nature Reserve, a 65,000-acre protected wilderness area near Montebello, Quebec, characterized by restricted access and minimal anthropogenic disturbance, which drains into the Ottawa River either directly or via the Riviere Rouge; (2) the Ottawa River itself, sampled downstream of moderate development after traversing extensive areas of Eastern Ontario and Western Quebec; and (3) the St. Lawrence River along the shores of Montreal Island, where the Ottawa River converges with the St. Lawrence, forming the primary outflow for the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. Surface water samples were collected using a ‘scoop and filter’ technique (see Supplementary Information for methodological details), followed by oil extraction to isolate microplastics. The recovered microplastics were subsequently examined and characterized at the Chemistry Department of McGill University.

In summary, microplastics were detected in every sample collected, including the control sample of municipal tap water obtained from a nearby kitchen faucet. Across all sites, the mean microplastic abundance was 6.7 particles per site, corresponding to approximately 0.0084 particles per liter. Fibers were the predominant microplastic type, accounting for 67% of all particles identified, while microbeads comprised only 0.003% of the total microplastics at these locations. Sites situated near areas of boating and recreational activity generally exhibited higher microplastic concentrations, and elevated levels were observed across all study regions (Kenauk Nature Reserve, the Ottawa River, and the St. Lawrence River). Although it was anticipated that microplastic abundance would be lower in Kenauk due to minimal human activity, statistical analysis did not reveal a significant difference between Kenauk and the more developed regions. In other words, even waters sampled within the protected Kenauk Nature Reserve exhibited microplastic contamination comparable to sites downstream of moderate or substantial human habitation, indicating that microplastics are widely distributed throughout the watershed and are present in virtually all sampled environments.

8. Discussion

The collective evidence from studies across the Great Lakes and their tributaries reveals that microbeads, although not the predominant form of microplastic pollution, are a persistent and widespread contaminant in surface waters, sediments, and shorelines. Their highest concentrations are consistently observed in proximity to urban centers and wastewater treatment plants, underscoring the critical role of these facilities as point sources. However, the variability in reported microbead abundances, driven by differences in sampling methodologies, environmental conditions, and the potential for misidentification, highlights the urgent need for standardized protocols in microplastic research.

The studies reviewed, along our own findings, consistently report the presence of plastic microbeads in a range of freshwater environments, including shorelines, surface waters, water columns, and sediments. While the abundance and composition of microbeads vary between locations and studies, it is clear that microbeads are widely distributed and are accumulating in significant quantities. Notably, microbeads have been detected at nearly every site sampled, even within large, protected nature reserves that are ostensibly isolated from direct human influence. The physical stability and chemical persistence of microbeads, coupled with their resistance to natural degradation processes, enable them to persist in freshwater systems for decades to centuries.

There is a pronounced correlation between microplastic abundance and both population density, and downstream transport from wastewater treatment plant effluent. For example, studies from Fredonia in 2012 and 2013 estimated microplastic densities of approximately 7,000 particles per square kilometer in the upstream Lakes Superior and Huron, increasing to 17,000 in Lake Michigan, 46,000 in Lake Erie, and reaching a striking 248,000 particles per square kilometer in Lake Ontario, the most downstream and densely populated of the Great Lakes. This nearly 40-fold increase from Lake Superior to Lake Ontario underscores the cumulative impact of urbanization and hydrological connectivity on microbead pollution within the basin.

In our sampling campaign across the Kenauk Nature Reserve, Ottawa River, and St. Lawrence River, we detected an average of 8.4 microplastic particles per cubic meter, with microbeads comprising only 0.003% of the total microplastics, equivalent to 2.52×10−4 microbeads/m³. While direct comparison of absolute concentrations with previous studies is limited by differences in sampling methodologies, the proportion of microbeads we measured from samples collected after the ban on microbeads is significantly lower than those reported in the ten pre-ban studies reviewed in this paper (see

Table 1), where the minimum reported value is 0.2% [

71] and typical values range from 2% to 5% [

22,

45,

67,

69,

70,

72]. This substantial reduction in microbead prevalence may be a significant finding, potentially reflecting the effectiveness of the 2018 ban on plastic microbeads in personal care products.

A 2024 study by Akhbarizadeh et al. examined wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents in Toronto and adjacent Lake Ontario surface waters, covering both pre- and post-ban periods (93). This study found that after the Canadian (2018) and U.S. (2017) bans on plastic microbeads in personal care products, the abundance of regulated (polyethylene) plastic microbeads in WWTP effluents declined by up to 86%, dropping from 8.4–14.3 particles/m³ before the bans to 2.0–2.2 particles/m³ after. A similar decline was observed in Lake Ontario surface waters, indicating that the bans have been effective in reducing plastic microbead pollution entering the lake via WWTPs. The post-ban microbead contamination estimate reported by Akhbarizadeh et al. is significantly higher than our measured value of 2.52×10−4 microbeads/m³. However, the variation in sampling techniques and analysis protocols between the two studies makes direct comparison difficult. Finally, Akhbarizadeh et al. also note that while the abundance of irregular (polyethylene) microbeads decreased significantly, the levels of spherical microbeads, often made of synthetic or polyethylene wax and not classified as plastic under current regulations, did not change significantly. This suggests that while the bans have been effective for regulated plastic microbeads, some nonplastic or unregulated microbead types persist, likely due to product reformulation. Although there are limited published post-ban quantitative data from other Canadian lakes, the evidence from Lake Ontario demonstrates a rapid and substantial reduction in plastic microbead pollution following regulatory action. The overall trend is positive, with a marked decrease in regulated microbead types, though continued monitoring is needed to assess the presence and impact of nonplastic alternatives.

From a broader perspective, these findings emphasize several priorities for future research and management. First, microbeads pose ecological risks disproportionate to their abundance due to their persistence, resistance to degradation, and potential for bioaccumulation and trophic transfer [

11]. Second, there is a clear need for technological innovation in microbead capture and removal at wastewater treatment facilities, as well as the development of biodegradable alternatives to conventional plastic microbeads. Third, the spatial patterns of microbead accumulation, especially near densely populated regions, highlight the necessity for targeted mitigation strategies and robust policy interventions, such as microbead bans and improved waste management practices.

Recent advancements in microbead technology and management focus on three main areas: the development of biodegradable alternatives, improvements in wastewater treatment for microbead removal, and novel biodegradation strategies, alongside the continued relevance of traditional cleaning agents. Biodegradable microbead alternatives have seen significant progress. Chitin-based materials, derived from shrimp shell waste, could offer an attractive alternative to plastic as they are both biodegradable and reusable [

85]. In recent studies, chitin-based materials are used to develop sponge-like structures designed to efficiently capture microplastics from water [

86]. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) microbeads are another promising alternative, designed for use in personal care products and capable of rapid sinking and biodegradation in aquatic environments [

87]. Additionally, core-shell microbeads have been created, where the core consists of natural abrasive particles such as sawdust or oat husk cellulose, and the shell is a hydrogel, providing effective exfoliation while being environmentally friendly [

88]. Wastewater treatment technologies have also advanced. Bio-based adsorbents like chitosan nanocomposites are used in fixed-bed continuous flow columns to remove various pollutants, including microplastics, from wastewater [

89]. Chitosan-coated microalgae-fungal pellets have been developed to enhance bioremediation of secondary effluent, improving the removal of microplastics and other contaminants [

90]. These approaches can be integrated into existing wastewater treatment infrastructure to increase microbead capture efficiency. Novel biodegradation strategies are emerging, particularly the use of biological agents such as microalgae and fungi. These organisms can break down microplastics in wastewater through enzymatic processes, offering a sustainable pathway for microbead removal and degradation [

91,

92]. Finally, traditional cleaning agents, such as well-rounded beach sand, remain relevant due to their non-toxic, naturally occurring properties. Beach sand has been used as an abrasive cleaning agent for centuries, avoiding the environmental risks associated with synthetic microbeads.

9. Conclusions

The ubiquitous presence of microplastics in all sampled environments, including protected reserves, underscores the global scale of the issue and the need for coordinated, basin-wide monitoring and management efforts. Notably, our finding of a markedly reduced percentage of microbeads in microplastic pollutants sampled in Quebec and Ontario, just 0.003% of total microplastics, compared to previously reported values (typically 2–5%), suggests that regulatory actions, such as the 2018 ban on plastic microbeads in personal care products, have been effective in curbing microbead pollution in freshwater systems. Moving forward, effective mitigation will depend on advances in microbead design, improved removal technologies at wastewater treatment plants, and harmonized monitoring and policy frameworks. Given the persistence and ecological risks associated with microbeads, their continued accumulation in freshwater systems represents a long-term threat to ecosystem health and water quality. These findings establish a critical baseline for future research and reinforce the necessity for comprehensive, multi-scale approaches to address microplastic pollution in freshwater environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., M.T., E.G; methodology, C.B., E.G; formal analysis, C.B.; E.G., T.B.; investigation, E.G., M.T., A.S., C.C-L., C.B.; resources, C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G., M.T., T.B., A.S., C.C.-L.; writing—review and editing, C.C-L., C.B.; supervision, C.B.; project administration, C.B.; funding acquisition, C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and McGill University through the Trottier Institute for Sustainable Engineering Design (TISED), and McGill’s Sustainability Systems Research Institute (SSRI). M.T. is grateful for a McGill Sustainability Fellowship to conduct this research, and C.J.B. thanks a Fulbright Fellowship and Eco-Leader Award funding for joint USA/Canada environmental research. A Kolbe Family travel grant is gratefully acknowledged for funding Lake Erie beach research sampling.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Kayrel Edwards and Dr. Mikhail Kim of McGill University Chemistry, for helpful suggestions regarding the proposal of alternative engineering approaches, including beach sand-substitution for plastic microbead exfoliants, and cellulose- and chitosan-based replacements. Prof. George McCourt of McGill’s School of Environment and Natural Resource Sciences is thanked for many helpful discussions. Appreciation is also extended to McGill University’s Building21 openlab for helpful perspectives on environmental writing, especially B21 Director Dr. Anita Parmar, and Dr. Alison Hirukawa. Holling C. Holling is acknowledged for providing geographical illustration of the watershed flow from Paddle to the Sea (1941). Lake Erie beach research sampling was assisted by summer students Jessica Sitko (Trent U./Toronto Metropolitan U.) and Michael Palmer (Western U.). During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used GEMA (Amass, accessed on 2025/05/21-26 and 2025/08/07-09/03) for the purposes of polishing the text with the help of the AI's writer assistant function, to enhance the clarity, coherence, and style of the scientific texts. GEMA's scientific assistant function was used to suggest relevant and up-to-date literature tailored to the research topics; and to help synthesize and summarize scientific papers for improved understanding and integration of findings. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EDCs |

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HDPE |

High-density polyethylene |

| LDPE |

Low-density polyethylene |

| PA |

Polyamide |

| PE |

Polyethylene |

| PETE |

Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PLA |

Polylactic acid |

| PMMA |

Poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| POPs |

Persistent organic pollutants |

| PP |

Polypropylene |

| PS |

Polystyrene |

| PU |

Polyurethane |

| PVC |

Polyvinyl chloride |

| SEM/EDS |

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy |

| WWTPs |

Wastewater treatment plants |

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An Overview of Chemical Additives Present in Plastics: Migration, Release, Fate and Environmental Impact during Their Use, Disposal and Recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava, V.; Chandra, S.; Aherne, J.; Alfonso, M.B.; Antão-Geraldes, A.M.; Attermeyer, K.; Bao, R.; Bartrons, M.; Berger, S.A.; Biernaczyk, M.; et al. Plastic Debris in Lakes and Reservoirs. Nature 2023, 619, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, A. (Anya); Meissner, K.; Humphrey, J.; Ross, H. Plastic Pollution and Packaging: Corporate Commitments and Actions from the Food and Beverage Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusaucy, J.; Gateuille, D.; Perrette, Y.; Naffrechoux, E. Microplastic Pollution of Worldwide Lakes. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, L.; Lucas, Z.; Walker, T.R. Evaluating Canada’s Single-Use Plastic Mitigation Policies via Brand Audit and Beach Cleanup Data to Reduce Plastic Pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 176, 113460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.; Liao, C.; Moon, H.-B. Severe Contamination and Time Trend of Legacy and Alternative Plasticizers in a Highly Industrialized Lake Associated with Regulations and Coastal Development. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 171, 112787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunola, O.S.; Onada, O.A.; Falaye, A.E. Mitigation Measures to Avert the Impacts of Plastics and Microplastics in the Marine Environment (a Review). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 9293–9310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyena, A.; Aniche, D.; Ogbolu, B.; Rakib, Md.; Uddin, J.; Walker, T. Governance Strategies for Mitigating Microplastic Pollution in the Marine Environment: A Review. Microplastics 2021, 1, 15–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, P.A. Basin. In Contaminants of the Great Lakes; Crossman, J., Weisener, C., Eds.; Occurrence, Sources, Transport, and Fate of Microplastics in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence River. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-57873-2. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Park, B.J.; Palace, V.P. Microplastics in Aquatic Environments: Implications for Canadian Ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.M.; Waldron, S.; Phoenix, V.; Gauchotte-Lindsay, C. Micro- and Nanoplastic Pollution of Freshwater and Wastewater Treatment Systems. Springer Sci. Rev. 2017, 5, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conkle, J.L.; Báez Del Valle, C.D.; Turner, J.W. Are We Underestimating Microplastic Contamination in Aquatic Environments? Environ. Manage. 2018, 61, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalčíková, G.; Alič, B.; Skalar, T.; Bundschuh, M.; Gotvajn, A.Ž. Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents as Source of Cosmetic Polyethylene Microbeads to Freshwater. Chemosphere 2017, 188, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallenbach, E.M.F.; Eriksen, T.E.; Hurley, R.R.; Jacobsen, D.; Singdahl-Larsen, C.; Friberg, N. Plastic Recycling Plant as a Point Source of Microplastics to Sediment and Macroinvertebrates in a Remote Stream. Microplastics Nanoplastics 2022, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, G.; Uchida, N.; Tuyen, L.H.; Tanaka, K.; Matsukami, H.; Kunisue, T.; Takahashi, S.; Viet, P.H.; Kuramochi, H.; Osako, M. Mechanical Recycling of Plastic Waste as a Point Source of Microplastic Pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 303, 119114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Huang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, F.; Chen, H.; Quan, G.; Yan, J.; Li, T.; et al. Environmental Occurrences, Fate, and Impacts of Microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 184, 109612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, A.K.; Jalil, A.A.; Dutta, K.; Rajendran, S.; Vasseghian, Y.; Qin, J.; Soto-Moscoso, M. Microplastics in the Environment: Recent Developments in Characteristic, Occurrence, Identification and Ecological Risk. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.J.; Warrack, S.; Langen, V.; Challis, J.K.; Hanson, M.L.; Rennie, M.D. Microplastic Contamination in Lake Winnipeg, Canada. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 225, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Collard, F.; Fabres, J.; Gabrielsen, G.W.; Provencher, J.F.; Rochman, C.M.; Van Sebille, E.; Tekman, M.B. Plastic Pollution in the Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, B.Y.; Corcoran, P.L.; Helm, P.A. Factors Influencing Microplastic Abundances in Nearshore, Tributary and Beach Sediments along the Ontario Shoreline of Lake Erie. J. Gt. Lakes Res. 2018, 44, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.K.; Corsi, S.R.; Mason, S.A. Plastic Debris in 29 Great Lakes Tributaries: Relations to Watershed Attributes and Hydrology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10377–10385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.; Gaur, A.; Suravajhala, R.; Chauhan, U.; Pant, M.; Tripathi, V.; Pant, G. Microplastic Pollution: Understanding Microbial Degradation and Strategies for Pollutant Reduction. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Kooi, M.; Diepens, N.J.; Koelmans, A.A. Lifetime Accumulation of Microplastic in Children and Adults. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 5084–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, D.; Prabhakar, R.; Barua, V.B.; Zekker, I.; Burlakovs, J.; Krauklis, A.; Hogland, W.; Vincevica-Gaile, Z. Microplastics in Aquatic Systems: A Comprehensive Review of Its Distribution, Environmental Interactions, and Health Risks. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 32, 56–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, K.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Negrei, C.; Moroșan, E.; Drăgănescu, D.; Preda, O.-T. Microplastics: A Real Global Threat for Environment and Food Safety: A State of the Art Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. ; Singh, S.K. Microplastics in Freshwater Ecosystems: Sources, Transport and Ecotoxicological Impacts on Aquatic Life and Human Health. Environ. Ecol. 2025, 43, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkovicova, N.; Hollerova, A.; Svobodova, Z.; Faldyna, M.; Faggio, C. Effects of Plastic Particles on Aquatic Invertebrates and Fish – A Review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 96, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Occurrence and Ecological Impact of Microplastics in Aquaculture Ecosystems. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoegbu, O.; Onuwa, P.O.; Kelle, H.I.; Onogwu, S.U.; Ajakaye, O.J.; Lullah-Deh, J.A.; Egwumah, J.; Unongul, T.P. The Environmental and Health Implications of Microplastics on Human and Aquatic Life. Int. J. Res. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2024, IX, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Bakir, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C. Characterisation, Quantity and Sorptive Properties of Microplastics Extracted from Cosmetics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 99, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendall, L.S.; Sewell, M.A. Contributing to Marine Pollution by Washing Your Face: Microplastics in Facial Cleansers. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 1225–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Pang, L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Zhao, S.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Li, F. Occurrence of Microplastics in Three Types of Household Cleaning Products and Their Estimated Emissions into the Aquatic Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 165903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nel, H.A.; Dalu, T.; Wasserman, R.J.; Hean, J.W. Colour and Size Influences Plastic Microbead Underestimation, Regardless of Sediment Grain Size. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanentzap, A.J.; Cottingham, S.; Fonvielle, J.; Riley, I.; Walker, L.M.; Woodman, S.G.; Kontou, D.; Pichler, C.M.; Reisner, E.; Lebreton, L. Microplastics and Anthropogenic Fibre Concentrations in Lakes Reflect Surrounding Land Use. PLOS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. International Policies to Reduce Plastic Marine Pollution from Single-Use Plastics (Plastic Bags and Microbeads): A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 118, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercauteren, M.; Semmouri, I.; Van Acker, E.; Pequeur, E.; Janssen, C.R.; Asselman, J. Toward a Better Understanding of the Contribution of Wastewater Treatment Plants to Microplastic Pollution in Receiving Waterways. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, M.; Huang, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhao, J.; Chan, F.; Yu, X. Effects of Different Treatment Processes in Four Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants on the Transport and Fate of Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalu, T.; Banda, T.; Mutshekwa, T.; Munyai, L.F.; Cuthbert, R.N. Effects of Urbanisation and a Wastewater Treatment Plant on Microplastic Densities along a Subtropical River System. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 36102–36111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagg, A.S.; Brandes, E.; Fischer, F.; Fischer, D.; Brandt, J.; Labrenz, M. Agricultural Application of Microplastic-Rich Sewage Sludge Leads to Further Uncontrolled Contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.J.; Santowski, A.; Chifflard, P. Investigating the Dispersal of Macro- and Microplastics on Agricultural Fields 30 Years after Sewage Sludge Application. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, S.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Shaari, K.; Amal, M.N.A.; Saad, M.Z.; Mat Isa, N.; Nazarudin, M.F.; Zulkifli, S.Z.; Sutra, J.; Ibrahim, M.A. Microplastics Pollution as an Invisible Potential Threat to Food Safety and Security, Policy Challenges and the Way Forward. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 9591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, W.; Fang, J.K.H.; Mo, J.; Li, L.; Pan, M.; Li, R.; Zeng, X.; Lai, K.P. A Review on the Combined Toxicological Effects of Microplastics and Their Attached Pollutants. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Busquets, R.; Campos, L.C. Enhancing Microplastic Removal from Natural Water Using Coagulant Aids. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballent, A.; Corcoran, P.L.; Madden, O.; Helm, P.A.; Longstaffe, F.J. Sources and Sinks of Microplastics in Canadian Lake Ontario Nearshore, Tributary and Beach Sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 110, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paço, A.; Duarte, K.; Da Costa, J.P.; Santos, P.S.M.; Pereira, R.; Pereira, M.E.; Freitas, A.C.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P. Biodegradation of Polyethylene Microplastics by the Marine Fungus Zalerion Maritimum. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geuskens, G. Chapter 3 Photodegradation of Polymers. In Comprehensive Chemical Kinetics; Elsevier, 1975; Vol. 14, pp. 333–424 ISBN 978-0-444-41155-6.

- Zhang, K.; Hamidian, A.H.; Tubić, A.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J.K.H.; Wu, C.; Lam, P.K.S. Understanding Plastic Degradation and Microplastic Formation in the Environment: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 274, 116554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanek, A.K.; Rymowicz, W.; Mirończuk, A.M. Degradation of Plastics and Plastic-Degrading Bacteria in Cold Marine Habitats. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7669–7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundungal, H.; Gangarapu, M.; Sarangapani, S.; Patchaiyappan, A.; Devipriya, S.P. Efficient Biodegradation of Polyethylene (HDPE) Waste by the Plastic-Eating Lesser Waxworm (Achroia Grisella). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 18509–18519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrapani, I.S.; Priyadarshini, A.I.; Srinivas, N.; Srinivas, K. Biodegradable Nanomaterials For Removal Of Microplastics Removal In Aquatic Ecosystems. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, T.; Rahman, N.M.M.A.; Olivito, F.; Ilham, Z.; Ahmad, R.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I. Agricultural Waste-Derived Biopolymers for Sustainable Food Packaging: Challenges and Future Prospects. Polymers 2025, 17, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzidi, S.; Ben Ayed, E.; Tarrés, Q.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Boufi, S. Processing Polymer Blends of Mater-Bi® and Poly-L-(Lactic Acid) for Blown Film Application with Enhanced Mechanical Strength. Polymers 2022, 15, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Topete, G.O.; Castanier-Rivas, J.D.; Bahena-Osorio, M.F.; Krause, S.; Larsen, J.R.; Loge, F.J.; Mahlknecht, J.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S.; González-López, M.E. Compounding One Problem with Another? A Look at Biodegradable Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 944, 173735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbari, A.; Ackerman, J.D.; Boegman, L.; Zhao, Y. Increases in Great Lake Winds and Extreme Events Facilitate Interbasin Coupling and Reduce Water Quality in Lake Erie. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, A.; Ranjan, R.; Bonina, S.M.C.; Izadmehr, M.; Giesy, J.P.; Li, A.; Sturchio, N.C.; Rockne, K.J. Aqueous Geochemical Controls on the Sestonic Microbial Community in Lakes Michigan and Superior. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, R.K.; David, N.P.; Buckman, S.; Koman, P.D. Overlooking the Coast: Limited Local Planning for Coastal Area Management along Michigan’s Great Lakes. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, C.; Vlodarchyk, B. Impact of COVID-19 on Drowning Patterns in the Great Lakes Region of North America. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 205, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, P.A.; Driscoll, D.G.; Carter, J.M. Climate, Streamflow, and Lake-level Trends in the Great Lakes Basin of the United States and Canada, water years 1960–2015. Scientific Investigations Report 2019, 2019-5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schantz, S.L. Editorial: Lakes in Crisis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conowall, P.; Schreiner, K.M.; Minor, E.C.; Hrabik, T.; Schoenebeck, C.W. Variability of Microplastic Loading and Retention in Four Inland Lakes in Minnesota, USA. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 328, 121573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanentzap, A.J.; Cottingham, S.; Fonvielle, J.; Riley, I.; Walker, L.M.; Woodman, S.G.; Kontou, D.; Pichler, C.M.; Reisner, E.; Lebreton, L. Microplastics and Anthropogenic Fibre Concentrations in Lakes Reflect Surrounding Land Use. PLOS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusaucy, J.; Gateuille, D.; Perrette, Y.; Naffrechoux, E. Microplastic Pollution of Worldwide Lakes. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zhang, W.; Yu, H.; Hai, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S.; Tsedevdorj, S.-O. Research Status and Prospects of Microplastic Pollution in Lakes. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksen, M.; Mason, S.; Wilson, S.; Box, C.; Zellers, A.; Edwards, W.; Farley, H.; Amato, S. Microplastic Pollution in the Surface Waters of the Laurentian Great Lakes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, R.A.; Avlijas, S.; Simard, M.A.; Ricciardi, A. Microplastic Pollution in St. Lawrence River Sediments. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 71, 1767–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, A.; Hoellein, T.J.; Mason, S.A.; Schluep, J.; Kelly, J.J. Microplastic Is an Abundant and Distinct Microbial Habitat in an Urban River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 11863–11871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbyszewski, M.; Corcoran, P.L.; Hockin, A. Comparison of the Distribution and Degradation of Plastic Debris along Shorelines of the Great Lakes, North America. J. Gt. Lakes Res. 2014, 40, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, P.L.; Norris, T.; Ceccanese, T.; Walzak, M.J.; Helm, P.A.; Marvin, C.H. Hidden Plastics of Lake Ontario, Canada and Their Potential Preservation in the Sediment Record. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 204, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Kammin, L.; Eriksen, M.; Aleid, G.; Wilson, S.; Box, C.; Williamson, N.; Riley, A. Pelagic Plastic Pollution within the Surface Waters of Lake Michigan, USA. J. Gt. Lakes Res. 2016, 42, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, R.N.; Beletsky, D.; Beletsky, R.; Wigginton, K.; Locke, B.W.; Duhaime, M.B. Distribution and Modeled Transport of Plastic Pollution in the Great Lakes, the World’s Largest Freshwater Resource. Front. Environ. Sci. 2017, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaire, J.C.; Pomeroy, C.; Herczegh, S.M.; Haggart, O.; Murphy, M. Microplastic Abundance and Distribution in the Open Water and Sediment of the Ottawa River, Canada, and Its Tributaries. FACETS 2017, 2, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Goonetilleke, A.; Ayoko, G.A.; Rintoul, L. Abundance, Distribution Patterns, and Identification of Microplastics in Brisbane River Sediments, Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Hermsen, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.M.; De France, J. Microplastics in Freshwaters and Drinking Water: Critical Review and Assessment of Data Quality. Water Res. 2019, 155, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquier, G.; Doyen, P.; Kazour, M.; Dehaut, A.; Diop, M.; Duflos, G.; Amara, R. Manta Net: The Golden Method for Sampling Surface Water Microplastics in Aquatic Environments. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 811112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, N.; Hamidian, A.H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M. Microplastic Sampling Techniques in Freshwaters and Sediments: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4225–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Rahman, M.S.; Uddin, M.N.; Sharifuzzaman, S.M.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Sarker, S.; Nawaz Chowdhury, M.S. Microplastic Contamination in Penaeid Shrimp from the Northern Bay of Bengal. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, S.; Song, B.; Burbage, C. Quantifying and Identifying Microplastics in the Effluent of Advanced Wastewater Treatment Systems Using Raman Microspectroscopy. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusher, A.L.; Welden, N.A.; Sobral, P.; Cole, M. Sampling, Isolating and Identifying Microplastics Ingested by Fish and Invertebrates *. In Analysis of Nanoplastics and Microplastics in Food; Nollet, L.M.L., Siddiqi, K.S., Eds.; CRC Press: First edition. | Boca Raton : CRC Press, 2020. | Series: Food analysis and properties, 2020; ISBN 978-0-429-46959-6. [Google Scholar]

- Crichton, E.M.; Noël, M.; Gies, E.A.; Ross, P.S. A Novel, Density-Independent and FTIR-Compatible Approach for the Rapid Extraction of Microplastics from Aquatic Sediments. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.E.; Kroon, F.J.; Motti, C.A. Recovering Microplastics from Marine Samples: A Review of Current Practices. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 123, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalver, R.; Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; López-García, I.; Hernández-Córdoba, M. An Overview of Microplastics Characterization by Thermal Analysis. Chemosphere 2020, 242, 125170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.F.; Nolasco, M.M.; Ribeiro, A.M.P.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A. Identification of Microplastics Using Raman Spectroscopy: Latest Developments and Future Prospects. Water Res. 2018, 142, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolaosho, T.L.; Rasaq, M.F.; Omotoye, E.V.; Araomo, O.V.; Adekoya, O.S.; Abolaji, O.Y.; Hungbo, J.J. Microplastics in Freshwater and Marine Ecosystems: Occurrence, Characterization, Sources, Distribution Dynamics, Fate, Transport Processes, Potential Mitigation Strategies, and Policy Interventions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.A.; Shamshina, J.L.; Zavgorodnya, O.; Cutfield, T.; Block, L.E.; Rogers, R.D. Porous Chitin Microbeads for More Sustainable Cosmetics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 11660–11667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Chen, L.; Li, F. Biodegradable and Re-Usable Sponge Materials Made from Chitin for Efficient Removal of Microplastics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volant, C.; Balnois, E.; Vignaud, G.; Magueresse, A.; Bruzaud, S. Design of Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Microbeads with Tunable Functional Properties and High Biodegradability in Seawater 2021.

- Chang Theresa, Fang Ye, Henry David, Weeks Wendell Porter, Wei Ying Biodegradable Microbeads.

- Leudjo Taka, A.; Klink, M.J.; Yangkou Mbianda, X.; Naidoo, E.B. Chitosan Nanocomposites for Water Treatment by Fixed-Bed Continuous Flow Column Adsorption: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 255, 117398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maneechote, W.; Cheirsilp, B.; Angelidaki, I.; Suyotha, W.; Boonsawang, P. Chitosan-Coated Oleaginous Microalgae-Fungal Pellets for Improved Bioremediation of Non-Sterile Secondary Effluent and Application in Carbon Dioxide Sequestration in Bubble Column Photobioreactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 372, 128675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanien, A.; Saadaoui, I.; Schipper, K.; Al-Marri, S.; Dalgamouni, T.; Aouida, M.; Saeed, S.; Al-Jabri, H.M. Genetic Engineering to Enhance Microalgal-Based Produced Water Treatment with Emphasis on CRISPR/Cas9: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 10, 1104914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangovan, B.; Detchanamurthy, S.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Rajarathinam, R.; Deepa, V.S. Biotreatment of Industrial Wastewater Using Microalgae: A Tool for a Sustainable Bioeconomy. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).