1. Introduction

Coffee is one of the most popular beverages worldwide, with an estimated daily consumption exceeding 2 billion cups [

1]. This phenomenon has increased considerably in recent years partially due to the growth of specialty coffee shops [

1]. In Chile, according to the latest Chilean Coffee Census (Censo Cafetero Chile 2022) [

2], the coffee shop market has been growing from 2019 to 2022, with a significant increase in new coffee shops, representing 39% of the total number of coffee shops in the country and according to this survey, both commercial and specialty coffee shops mainly sell coffee beans or their derivatives, rather than instant coffee [

2]. Furthermore, over 80% of the Chilean population purchases coffee in bean format when they go to commercial or specialty coffee shops, and 45% of the coffee shops surveyed had coffee consumption in the range of 6 to 20 kg in 2022 [

2]. Coffee consumption is primarily associated with caffeine intake; however, this beverage contains over 1000 bioactive compounds with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties [

3]. Several studies have linked coffee consumption to reduced risk of mortality from various causes [

4,

5] including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and some types of cancer due to their potential to influence carcinogenesis [

3,

4].

Caffeine is one of the main compounds found in coffee, a natural alkaloid present in numerous plant species [

6,

7] and regarded as one of the most commonly consumed psychoactive substances worldwide [

6]. Although rigorous studies indicate that moderate doses of caffeine (up to 400 mg/day) are generally safe for healthy adults, evidence on long-term effects and interactions with other risk factors [

6]. Another highly relevant compound present in coffee beans is Chlorogenic Acids (CGAs) [

8], the main group of phenolic compounds that make up the chemical matrix of green coffee [

8], which are constituted by a large family of natural esters formed by the union of quinic acid with one, two or even three groups of cinnamic acids or their derivatives, the most common being caffeic, ferulic and p-coumaric acids [

9]. Within this family, caffeic acid esters represent the predominant class, with 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid (5-CQA) being the most abundant and widely distributed in nature [

9,

10]. CGAs are present in coffee drinks, many fruits and vegetables such as apples, pears, blueberries, carrots and tomatoes, among others [

11]. This group of compounds have remarkable antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial properties and have been appreciated for their beneficial effects against hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity and Alzheimer’s disease [

8,

11]. The bioavailability of CGAs may be affected by the processing of the coffee bean (drying and roasting) for consumption [

12]. This could lead to the destruction of this biomolecule in a progressive manner, generating losses of around 8-10% for every 1% loss of dry matter in the early stages of processing [

12]. A study by Kim et al. [

13], which compared green coffee beans fermented with

Bacillus subtilis versus non-fermented beans, reported that the CGAs content of fermented beans was 9.2 times higher than non-fermented beans. This finding shows that, in addition to roasting and drying, the fermentation process can significantly influence the bioavailability of these compounds [

13].

Therefore, given the role of CGAs as the main antioxidant present in coffee beans and their preparations, and caffeine as one of the most consumed bioactive compounds by the local population, as well as the absence of studies in products from the Chilean market to evaluate these compounds, it is relevant to investigate how the concentrations of caffeine and total CGAs vary in preparations that reproduce daily consumption in the country. This study considers the types of coffee (powder, freeze-dried and beans) and the most common preparation practices in the coffee-consuming population (instant preparations, filter coffee machine), both in caffeinated and decaffeinated coffees.

2. Materials and Methods

Coffee bean and soluble coffee products were purchased in commercial establishments (supermarkets and specialized coffee shops) located in Santiago, Chile. The soluble products analyzed correspond to instant and freeze-dried formats. Instant coffee whose label does not specify the type or origin of the beans used in its production was classified as a blend. All bean and instant coffee samples were checked to ensure that they had an expiry date after the date of analysis. Samples were stored in their original sealed containers in dark conditions at a controlled temperature of 20°C until analysis.

2.1. Reagents and Solvents

Chlorogenic acid standard, (purity ≥95%) was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Michigan, USA). Caffeine (purity 98.5%) was obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Alemania). Methanol (purity 99.8%) and HPLC-grade water were obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Alemania). 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) was purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Alemania).

2.2. Preparation and Extraction of Coffee Samples for Ultra High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC)

The preparations were carried out following the manufacturer

’s instructions, differentiating the protocols according to the type of coffee. The coffee bean samples were ground using a Jubake

® (model JU-7711, Guangdong, China) coffee grinder for 25 seconds. The infusions were prepared in a Hamilton Beach

® (model 49615-CL, Wisconsin, USA) coffee machine with 200 mL of distilled water. 11.10 g of medium roast and decaffeinated coffee was dosed, meanwhile 8.00 g of dark roast coffee was used. Instant and freeze-dried coffee powder were prepared in a final volume of 200 mL. The dosage was 3 g for

blend instant coffee and 3.33 g for medium and dark roasted coffees. For freeze-dried coffee, 2.22 g were used. In the case of decaffeinated coffees, 5.00 g were used (

Table A1). In all cases, the coffee was left to macerate for 5 min at 90 °C in a thermoregulated bath. Once the samples reached room temperature, were filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter. The solutions were diluted to 0.1%v/v in methanol and stored at -80 °C until analysis by UHPLC.

2.3. Preparation of Caffeine and CGAs Calibration Curve by UHPLC

A caffeine calibration curve was prepared with the following concentrations: 10, 5, 1, 0.5 and 0.1 µg/mL in methanol. The CGAs calibration curve was worked out at a concentration of 20, 15, 10, 5, 1 µg/mL in methanol.

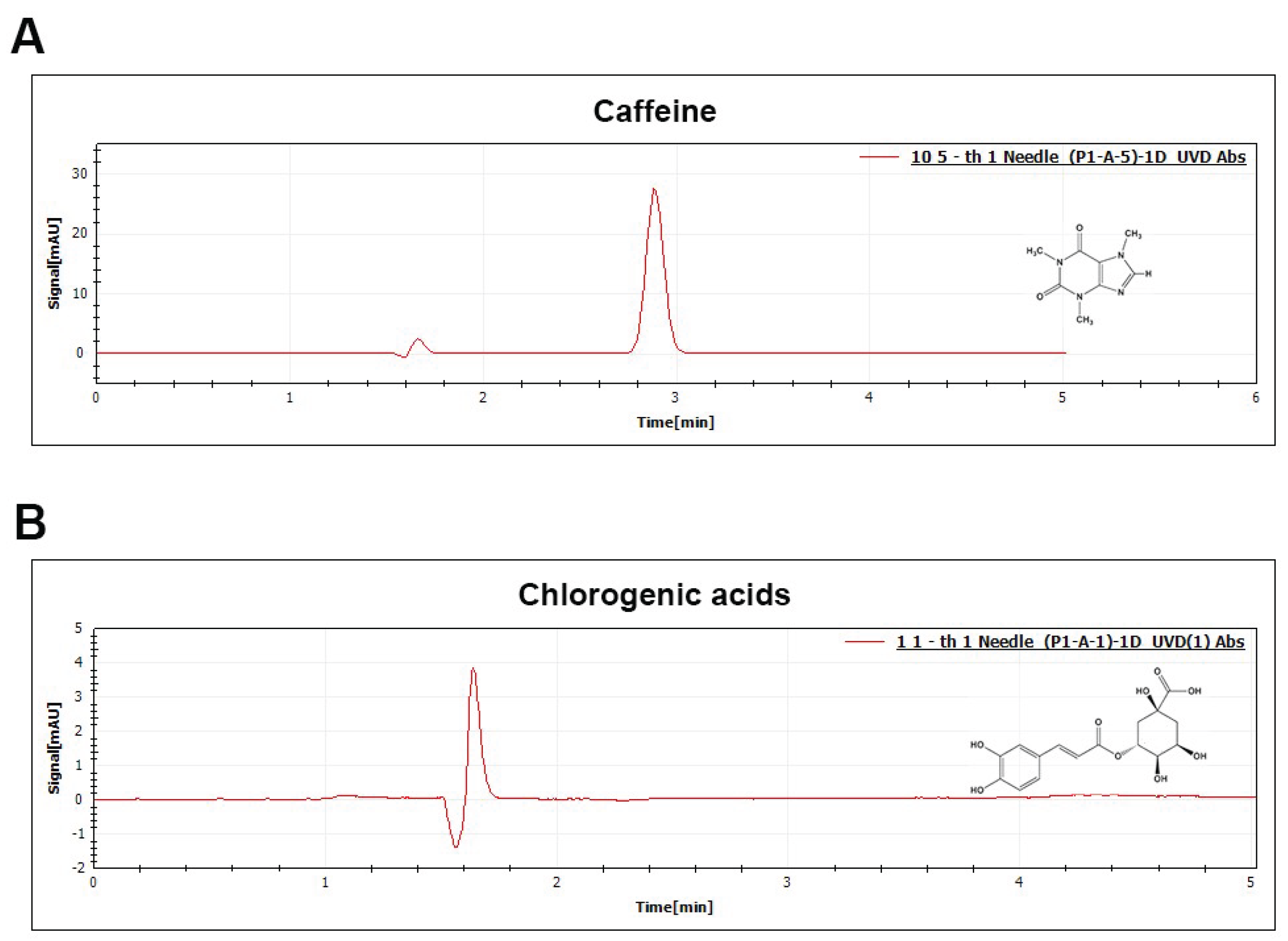

2.4. Identification and Quantification of Caffeine and CGAs by UHPLC

UHPLC analysis was performed according to Jeon et al

. [

14]. UHPLC-1511 UV-Tech (Beijing, China) with ANAVO technologies Inc. (Beijing, China) C18 5 µm column was used. For caffeine measurement, the column was maintained at 40 °C, and for CGAs at 25 °C during the whole process. A calibration curve was performed with the caffeine and CGAs standard. Caffeine was measured at 272 nm and CGAs was measured at 278 nm (

Figure 1).

2.5. Determination of the Antioxidant Capacity of Coffee

The antioxidant capacity was evaluated by the DPPH radical scavenging assay according to Brand-Williams et al

. [

15], with modifications proposed by Marinova & Batchvarov [

16] and adaptations to scale down to 96-well microplates. A stock solution of 0.6 mM DPPH in ethanol was prepared and stored at 4 °C in the dark. This solution was diluted for assays to a concentration of 0.06 mM. In each row of the microplate a serial dilution of the extracts was performed with a dilution factor of 2 from an initial 10% v/v dilution to the concentration recommended by the manufacturer for consumption. To perform the assay, 100 µL of 0.06 mM DPPH solution and 100 µL sample were added to each well and incubated for 30 min in the dark, absorbance was measured at 517 nm in TECAN

® (Infinite 200 pro, Grödig, Austria). Controls were performed for each component to avoid absorbance interferences.

2.6. Analysis of Results

The following equation was used to determine the percentage of radical inhibition:

%Inhibition = ((Abs radical – Abs sample) / Abs radical) * 100

Where:

Abs radical: corresponds to the absorbance of the negative control (radical + water).

Abs sample: Corresponds to the difference between the absorbance of the preparation control (ethanol + water) and the absorbance of the sample (sample + radical).

The IC50 parameter was also calculated in the units of portions per 200 mL serving and milligrams per milliliter by interpolation of the curve obtained by the dilutions.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed with STATA/IC (version 15.0, Texas, USA) software and a significance level of α=0.05 and an confidence interval (CI) of 95% was considered. The normal distribution of the data was verified with the Shapiro-Wilk test. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to determine variations in the means of CGAs and caffeine among the samples (bean, freeze-dried, instant - powder). Also, a Tukey post hoc test was applied to analyze the differences between each group, where different letters between groups represent significant differences between groups (p<0.05). The measurements of the coffee sample were performed in triplicates. The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

For the statistical analysis of antioxidant capacity, the Shapiro-Wilk Normality test was performed. ANOVA was applied to determine variations in IC50 means. Post hoc Tukey analysis was performed for IC50 values to identify differences between each group, where different letters between groups represent significant differences between groups (p<0.05). The measurements of the coffee sample were performed in triplicates. The results were expressed as mean ± SD.

3. Results

3.1. Quantification of Caffeine in Instant Coffee Samples

The sample corresponding to the medium roast coffee powder showed the highest concentration, with an average value of 94.98 ± 3.69 mg/serving, significantly higher than the rest of the samples (p<0.05). It was followed by commercial freeze-dried coffee, with an average of 76.30 ± 3.68 mg/serving, with no statistical differences with respect to dark roast instant coffee, which had an average of 74.65 ± 4.88 mg/serving. Finally, the lowest concentration of caffeine corresponds to blend-type powdered coffee, whose average concentration was 43.55 ± 3.32 mg/serving. No caffeine was detected in decaffeinated coffees (p<0.05) (

Table 1).

3.2. Quantification of Caffeine in Coffee Bean Samples

Statistically significant differences were observed only between the caffeinated samples and the decaffeinated sample (p<0.05). There are no significant differences between the caffeinated coffee bean preparations. However, a trend towards higher caffeine concentration was observed in medium roast coffee compared to dark roast coffee (

Table 2).

3.3. Quantification of Total CGAs in Instant Coffee Samples

The highest concentrations were observed in freeze-dried coffee and medium roast coffee powder, with mean values of 68.21 ± 6.17 mg/serving and 64.17 ± 6.01 mg/serving, respectively, with no statistical differences between the two samples. These values were significantly higher compared to the other samples analysed (p<0.05). The lowest CGAs concentrations were recorded in decaffeinated coffees, both powdered and freeze-dried, with mean values of 10.33 ± 7.51 mg/serving and 7.11 ± 3.17 mg/serving, respectively, showing no statistical differences between them (

Table 1).

3.4. Quantification of Total CGAs in Coffee Bean Samples

The comparison between the coffee bean samples shows higher concentrations of total CGAs in the medium roasted coffee than in the other two samples, with a mean value of 111.67 ± 6.51 mg/serving, which is statistically significant (p<0.05), while the decaffeinated dark roasted coffee beans show a lower concentration of this polyphenol, with a mean value of 31.17 ± 4.25 mg/serving (

Table 2).

3.5. Analysis of Antioxidant Capacity in Instant Coffees Samples

Antioxidant capacity of the six instant coffee samples analysed (powder and freeze-dried) is presented in

Table 3. Among the instant coffees, the highest antioxidant capacity of the decaffeinated coffee powder preparation per serving stands out, represented by an IC

50 of 0.0053 ± 1.8772 * 10

-4 portion/serving, while the other preparations, regardless of the type of roasting or the production method, showed no statistically significant differences in their antioxidant capacity. However, when standardising the preparations to the same concentration (mg/mL), no statistically significant differences were found between any of the preparations (

Table 3).

3.6. Analysis of Antioxidant Capacity in Coffee Beans Samples

It can be seen that the medium roast coffee has the highest antioxidant capacity per serving, with a IC

50 of 0.0156 ± 0.0009 portion/serving, being this difference statistically significant in comparision with the other samples (p<0.05). The lowest antioxidant capacity is in the decaffeinated coffee preparation with a IC

50 of 0.0299 ± 0.0018 portion/serving, being this difference also statistically significant (p<0.05). When standardising the concentrations (mg/mL), there is only a statistically significant difference between the medium roast coffee and the other samples (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Caffeine, an alkaloid recognized for its stimulant effect on the central nervous system and is one of the most widely consumed psychoactive substances worldwide [

6,

7]. This study confirms that the concentration of caffeine per serving is not standard, due to different factors. In the instant coffee samples, the medium roast product had the highest concentration, followed by freeze-dried coffee, while the lowest concentrations were found in blended preparations and decaffeinated, which do not contain the compound. This heterogeneity is consistent with the literature, which attributes differences in caffeine concentration to variables ranging from bean origin (including species, altitude and microclimatic conditions [

17,

18,

19] to industrial processes and

blend formulation [

20]. Indeed, environmental factors such as altitude and solar radiation have been shown to positively modulate caffeine accumulation in the coffee bean [

21,

22], introducing background variability that carries over to the commercial product. As expected, decaffeinated coffees showed an absence of caffeine, validating the efficacy of industrial extraction processes, mainly employ organic solvents, water or supercritical carbon dioxide [

23].

However, the most significant difference emerged when comparing formats per serving of consumption. A standard 200 mL serving prepared from coffee beans (medium roast) delivered a caffeine dose almost double that of the more concentrated instant coffee sample. This is explained by the preparation from beans being an in situ solid liquid extraction, a highly efficient process for releasing caffeine from the cellular matrix of the freshly ground bean [

24]. In contrast, instant coffee is a pre-processed and dehydrated industrial extract, involving extraction, concentration and drying (spray or freeze-drying) steps [

25,

26], which, while optimized for standardization and solubility of the final product, may not maximize the concentration of caffeine in the resulting solid compared to the potential of a fresh extraction [

25,

26]. The relative thermostability of caffeine, evidenced by the lack of significant differences between our medium- and dark-roasted beans, reinforces that the determining factor in this gap is not the degree of roast, but the fundamental difference between a fresh infusion and rehydration of a processed extract [

27].

Unlike caffeine, CGAs, coffee’s main phenolic compound and a potent antioxidant [

8,

11] is highly thermolabile [

28,

29]. This characteristic was a clear differentiator between the results obtained. In coffee beans, the concentration of CGAs was significantly higher in the medium roast than in the dark roast, confirming its degradation at higher roasting temperatures [

28,

29,

30]. This differential degradation is quantitatively evidenced by the caffeine:CGAs ratio, which increased from 1.77 in the medium roast to 1.92 in the dark roast, reflecting a loss of this compound to caffeine. Among instant coffees, the freeze-dried product stood out for its high CGAs retention, comparable to that of medium-roast instant coffee. Freeze-drying, a low-temperature drying process, is known to preserve heat-sensitive compounds more effectively [

31,

32]. The notably lower caffeine:CGAs ratio in freeze-dried coffee (ratio: 1.12) compared to its powdered counterparts (ratio: 1.48) reinforces that this processing method offers an advantage in preserving the phenolic profile. This finding demonstrates that the superiority of filtered coffee in terms of CGAs dose per serving goes beyond the mass of product used. It represents the fundamental 327 difference between an in-situ extraction from a more phytochemically intact matrix and the rehydration of an industrial extract [

26,

33]. The soluble coffee manufacturing process, which includes large-scale extraction, concentration and thermal drying steps, subjects the compounds to prolonged thermal and oxidative stress [

34]. Given the known thermolability of CGAs [

28], cumulative degradation is inevitable along this production chain [

28]. Consequently, coffee beans, when subjected only to roasting prior to final infusion by the consumer, retain a higher CGAs potential that is efficiently released during fresh preparation [

35]. Therefore, with respect to the results of this work, the higher CGAs concentration per cup of filtered coffee is a direct reflection of the superior preservation of the compound in a product that bypasses intensive post roast industrial processing.

The antioxidant capacity of coffee is a complex property that does not depend exclusively on CGAs [

26]. In coffee beans, this correlation was direct: the medium roast, with the highest CGAs content, had a significantly higher antioxidant capacity than the other coffee bean samples. However, in instant coffees, the picture was different. Despite variations in CGAs content, no significant differences in antioxidant capacity were observed between the different brewed coffees when normalized by concentration (mg/mL). This apparent discrepancy between CGAs concentration and reported antioxidant capacity suggests a contribution from other antioxidants compounds, such as CGAs-derived lactones, which arise from the degradation of CGAs, and may have antioxidant properties [

35]. These are formed due to the coffee roasting process [

35] or the process of generating instant coffee [

26]. This could explain the robust antioxidant capacity of instant decaffeinated coffee, which, despite its low CGAs content, was not significantly lower than the others [

35,

36].

The results of this study show that, although medium-roasted coffee beans have the highest CGAs content, instant coffee preparations demonstrate greater antioxidant capacity per unit mass (mg/ml). This reinforces the hypothesis that industrial processing, while reducing the native CGAs content, enriches the final product with a set of antioxidant compounds that modify its functional properties [

26], whereas in coffee beans CGAs is the main predictor of antioxidant capacity, in instant coffee this property is the result of a more complex balance between the original phenols and compounds generated during processing [

37,

38].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the concentration of caffeine and CGAs in commercially available coffee products shows a marked variability determined by the type of format, degree of roasting and industrial processing. While medium roast coffee beans provide the highest concentration of caffeine and CGAs per serving, instant coffee - particularly in its freeze-dried format - exhibits a more favorable retention of phenolic compounds relative to instant coffee powder, despite its lower total caffeine content. Furthermore, the antioxidant capacity is not only explained by CGAs, but by a more complex web of metabolites derived from thermal and industrial processing.

Significantly, this work is the first systematic characterization of caffeine, CGAs and antioxidant capacity in instant and whole bean coffees available on the Chilean market, providing unprecedented evidence for the national context. The absence of previous studies of this type in Chile reinforces the importance of these findings and opens up the need for future research that considers both the diversity of commercial matrices and the impact of these variations on the dietary exposure of the population.

It is important to move towards studies that integrate these chemical profiles with clinical and nutritional assessments in order to understand how differences between instant and whole bean coffees affect the bioavailability of bioactive compounds and their effects on health. It would also be relevant to explore the development of optimized soluble products that preserve the integrity of the phenolic compounds, offering more standardized functional alternatives for mass consumption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A, R.C, P.N and S.E.; methodology, I.A, R.C, S.E, and P.N.; software, I.A and F.P.; validation, I.A, P.N and M.C.; formal analysis, I.A. P.N. D.S and N.E.; investigation, I.A, P.N.; resources, I.A, R.C, F.P and S.E.; data curation, I.A, R.C and S.E.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A, P.N, R.C, S.E.; writing—review and editing, I.A, P.N and R.C.; visualization, I.A R.C, P.N.; supervision, P.N, M.C; project administration, P.N, M.C.; funding acquisition, P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Miguel Castro, who provided materials and equipment to carry out this work. Thanks also to Austral Biotech Research Center for funding the publication of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA |

One-way analysis of variance. |

| CGAs |

Chlorogenic Acids. |

| CI |

Confidence Interval. |

| DPPH |

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl. |

| SD |

Standard Deviation. |

| UHPLC |

Ultra High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography. |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Coffee samples and quantities used for beverage preparation (200 mL).

Table A1.

Coffee samples and quantities used for beverage preparation (200 mL).

| Instant Coffee Samples |

Mass (g) / 200 mL |

| Instant (blend) |

3 |

| Dark roast instant |

3.3 |

| Medium roast instant |

3.3 |

| Decaffeinated instant |

5 |

| Freeze-dried |

2.22 |

| Freeze-dried decaffeinated |

5 |

| Bean Coffee Samples |

Mass (g) / 200 mL |

| Medium roast. |

11.1 |

| Dark roast |

8 |

| Decaffeinated dark roast |

11.1 |

The table summarizes the amount of coffee powder or ground coffee (in grams) required for the preparation of 200 mL beverages across different commercial presentations. Instant coffee (blend, dark roast, medium roast, and decaffeinated), freeze-dried samples (regular and decaffeinated) and beans coffee preparation were weighed according to label instructions or standardized serving sizes.

References

- Safe S, Kothari J, Hailemariam A, Upadhyay S, Davidson LA, Chapkin RS. Health Benefits of Coffee Consumption for Cancer and Other Diseases and Mechanisms of Action. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter P, Yuan S, Kar S, Vithayathil M, Mason AM, Burgess S, Larsson SC. Coffee consumption and cancer risk: a Mendelian randomisation study. Clin Nutr. 2022, 41, 2113–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbaere K, Close JC, Brodaty H, Sachdev P, Lord SR. Determinants of disparities between perceived and physiological risk of falling among elderly people: cohort study. BMJ. 2010, 341, c4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Je Y, Giovannucci E. Coffee consumption and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a meta-analysis by potential modifiers. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 731–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expocafé. Censo cafetero Chile. 2022 Dec.

- Čižmárová, B.; Kraus, V., Jr.; Birková, A. Caffeinated Beverages—Unveiling Their Impact on Human Health. Beverages. 2025, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalo, R. Coffee and Caffeine Consumption for Human Health. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajik N, Tajik M, Mack I, Enck P. The potential effects of chlorogenic acid, the main phenolic components in coffee, on health: a comprehensive review of the literature. Eur J Nutr. 2017, 56, 2215–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawidowicz AL, Typek R, Hołowiński P, Olszowy-Tomczyk M. The hydrates of chlorogenic acid in its aqueous solution and in stored food products. European Food Research and Technology. 2024, 250, 2669–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu H, Tian Z, Cui Y, Liu Z, Ma X. Chlorogenic acid: A comprehensive review of the dietary sources, processing effects, bioavailability, beneficial properties, mechanisms of action, and future directions. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3130–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed MAE, Mohanad M, Ahmed AAE, Aboulhoda BE, El-Awdan SA. Mechanistic insights into the protective effects of chlorogenic acid against indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer in rats: Modulation of the cross talk between autophagy and apoptosis signaling. Life Sci. 2021, 15, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, MN. Chlorogenic acids and other cinnamates - nature, occurrence, dietary burden, absorption and metabolism. J Sci Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1033–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim B, Lee DS, Kim HS, Park T, Kim JK, Kim SW, et al. Bioactivity of Fermented Green Coffee Bean Extract Containing High Chlorogenic Acid and Surfactin. J Med Food. 2019, 22, 305–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon JS, Kim HT, Jeong IH, Hong SR, Oh MS, Park KH, et al. Determination of chlorogenic acids and caffeine in homemade brewed coffee prepared under various conditions. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2017, 1064, 115–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova G, Batchvarov V. Evaluation of the methods for determination of the free radical scavenging activity by DPPH. Bulg J Agric Sci. 2011, 17, 11–24.

- Kim JS, Pak J, Choi J, Park SE, Bae S, Cho H, Kwak S, Son HS. Factors influencing metabolite profiles in global Arabica green coffee beans: Impact of continent, altitude, post-harvest processing, and variety. Food Res Int. 2025, 208, 116187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell JA, Loftfield E, Wedekind R, Freedman N, Kambanis 457 C, Scalbert A, et al. A metabolomic study of the variability of the chemical composition of commonly consumed coffee brews. Metabolites. 2019, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaliyah S, Widiyanto SNB, Maulani RR, Hidayat A, Husyari UD, Syamsudin TS, et al. Correlation of Microclimate of West Java on Caffeine and Chlorogenic acid in Coffea canephora var. robusta. 3BIO: J Biol Sci Technol Manag. 2022, 4, 54–60. [CrossRef]

- Davila C, Sîrbu R. Determination of Caffeine Content in Arabica and Robusta Green Coffee of Indian Origin. J Nat Sci Med. 2021, 4, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joët T, Laffargue A, Descroix F, Doulbeau S, Bertrand B, kochko A de, et al. Influence of environmental factors, wet processing and their interactions on the biochemical composition of green Arabica coffee beans. Food Chem. 2010, 118, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar Y, Alya MR, Karim A, Fazlina YD. Effect of variety and farm altitude on chemical content of Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) grown in Gayo Highland, Indonesia. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2024, 1356, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park H, Noh E, Kim M, Lee KG. Analysis of volatile and nonvolatile compounds in decaffeinated and regular coffee prepared under various roasting conditions. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang D, Lin CY, Hu CT, Lee S. Caffeine Extraction from Raw and Roasted Coffee Beans. J Food Sci. 2018, 83, 975–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghirişan A, Miclăuş V. Comparative study of spray-drying and freeze drying on the soluble coffee properties. Studia UBB Chemia. 2017, 62, 309–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Parra MB, Gómez-Domínguez I, Iriondo-DeHond M, Villamediana Merino E, Sánchez-Martín V, Mendiola JA, et al. The Impact of the Drying Process on the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Dried Ripe Coffee Cherry Pulp Soluble Powder. Foods, 1114; 13. [CrossRef]

- Honda M, Takezaki D, Tanaka M, Fukaya M, Goto M. Effect of roasting degree on major coffee compounds: a comparative study between coffee beans with and without supercritical CO2 decaffeination treatment. J Oleo Sci. 2022, 71, ess22194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim YK, Lim JM, Kim YJ, Kim W. Alterations in pH of Coffee Bean Extract and Properties of Chlorogenic Acid Based on the Roasting Degree. Foods. 2024, 13, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, S.; Issa, R.; Alnsour, L.; Albals, D.; Al-Momani, I. Quantification of Caffeine and Chlorogenic Acid in Green and Roasted Coffee Samples Using HPLC-DAD and Evaluation of the Effect of Degree of Roasting on Their Levels. Molecules 2021, 26, 7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan Ayseli M, Kelebek H, Selli S. Elucidation of aroma-active compounds and chlorogenic acids of Turkish coffee brewed from medium and dark roasted Coffea arabica beans. Food Chem. 2021, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deotale SM, Dutta S, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C. Influence of drying techniques on sensory profile and chlorogenic acid content of instant coffee powders. Measurement: Food. 2022, 6. [CrossRef]

- Jiamjariyatam R, Samosorn S, Dolsophon K, Tantayotai P, Lorliam W, Krajangsang S. Effects of drying processes on the quality of coffee pulp. J Food Process Preserv. 2022, 46. [CrossRef]

- Anh-Dao LT, Chi-Thien T, Nhut-Truong N, Tu-Chi T, Minh-Huy D, Thanh-Nho N, et al. Changes in the total phenolic contents, chlorogenic acid, and caffeine of coffee cups regarding different brewing methods. Food Res. 2024, 8, 71-9. 8,. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Gu J, BK A, Nawaz MA, Barrow CJ, Dunshea FR, et al. Effect of processing on bioaccessibility and bioavailability of bioactive compounds in coffee beans. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101373. [CrossRef]

- Farah A, De Paulis T, Trugo LC, Martin PR. Effect of roasting on the formation of chlorogenic acid lactones in coffee. J Agric Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1505–13. [CrossRef]

- Shofinita D, Lestari D, Purwadi R, Sumampouw GA, Gunawan KC, Ambarwati SA, et al. Effects of different decaffeination methods on caffeine contents, physicochemical, and sensory properties of coffee. Int. J. Food Eng. 2024, 20, 561–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Lu P, Liu Z, Sharifi-Rad J, Suleria HAR. Impact of roasting on the phenolic and volatile compounds in coffee beans. Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 10, 2408–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corso MP, Vignoli JA, Benassi Mde T. Development of an instant coffee enriched with chlorogenic acids. J Food Sci Technol. 2016, 53, 1380–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).