Submitted:

06 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

Spatial patterns

Institutional links

3. Materials and Methods

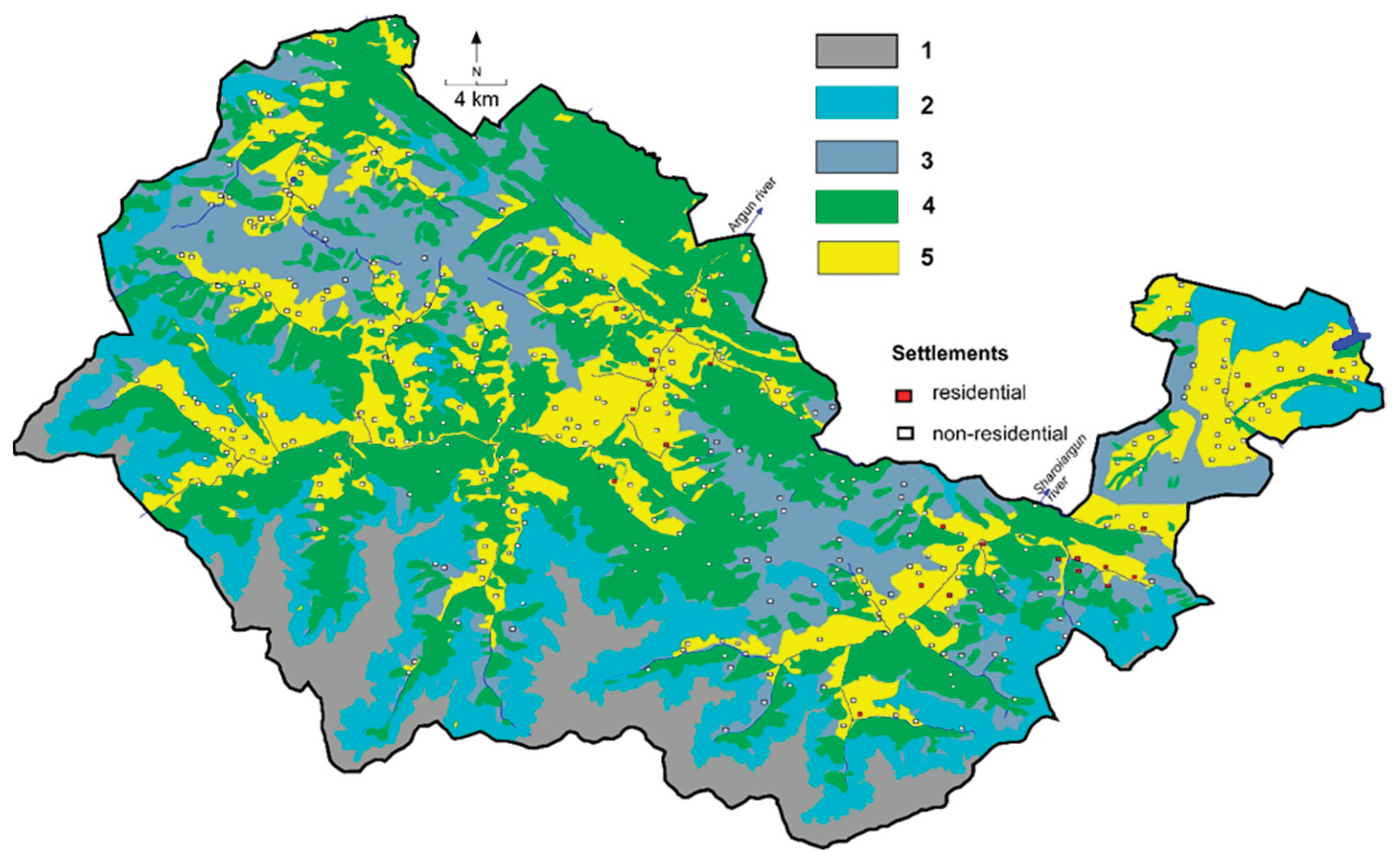

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data and Methods

4. Results

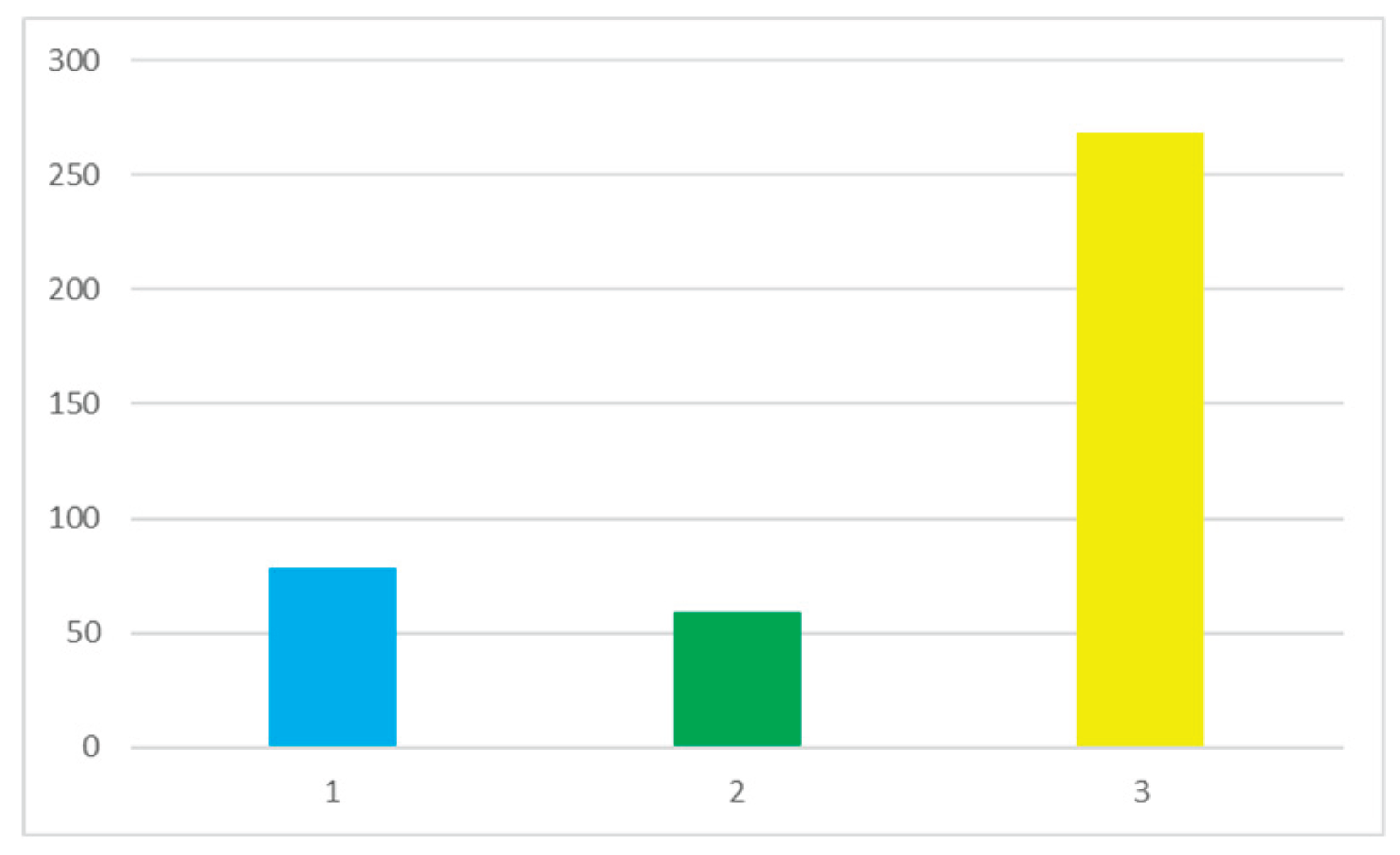

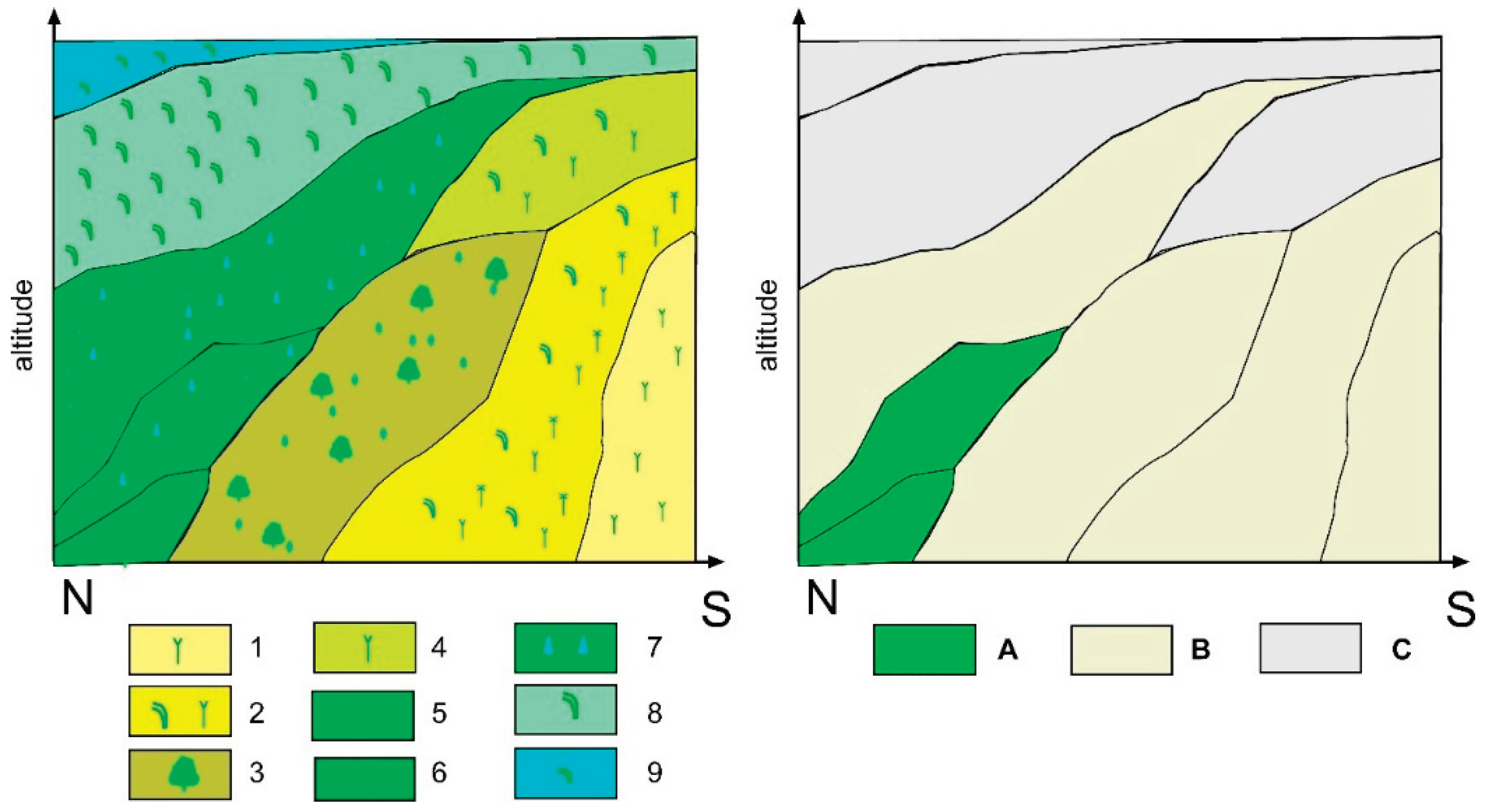

4.1. Mountain Forestscape and Humans: Natural Boundaries and Ecotones

4.2. Mountain Forestscapes and Institutions

| Period | Actors | Key resources | Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Until the mid-19th century | The local community, represented by family-clan and tukhums | Firewood, building materials, forest products, hunting – everything for natural farming | Adat |

| Mid-19th century – 1944 | The local community, represented by family-clan and tukhums, the state | Firewood, building materials, forest products, hunting for natural farming, timber | Adat, state forest management |

| From 1944 to the early 1990s | The state, collective and state farms located on the plain, forestry enterprises, protected areas | Firewood for residents of the foothills, building materials, local forest products, beekeeping | State forest management, environmental legislation, adat |

| Since the 2000s | The state, teips, private entrepreneurs | recreation, spiritual and sacred space, local forest products, beekeeping | State forest management, adat, state development programmes |

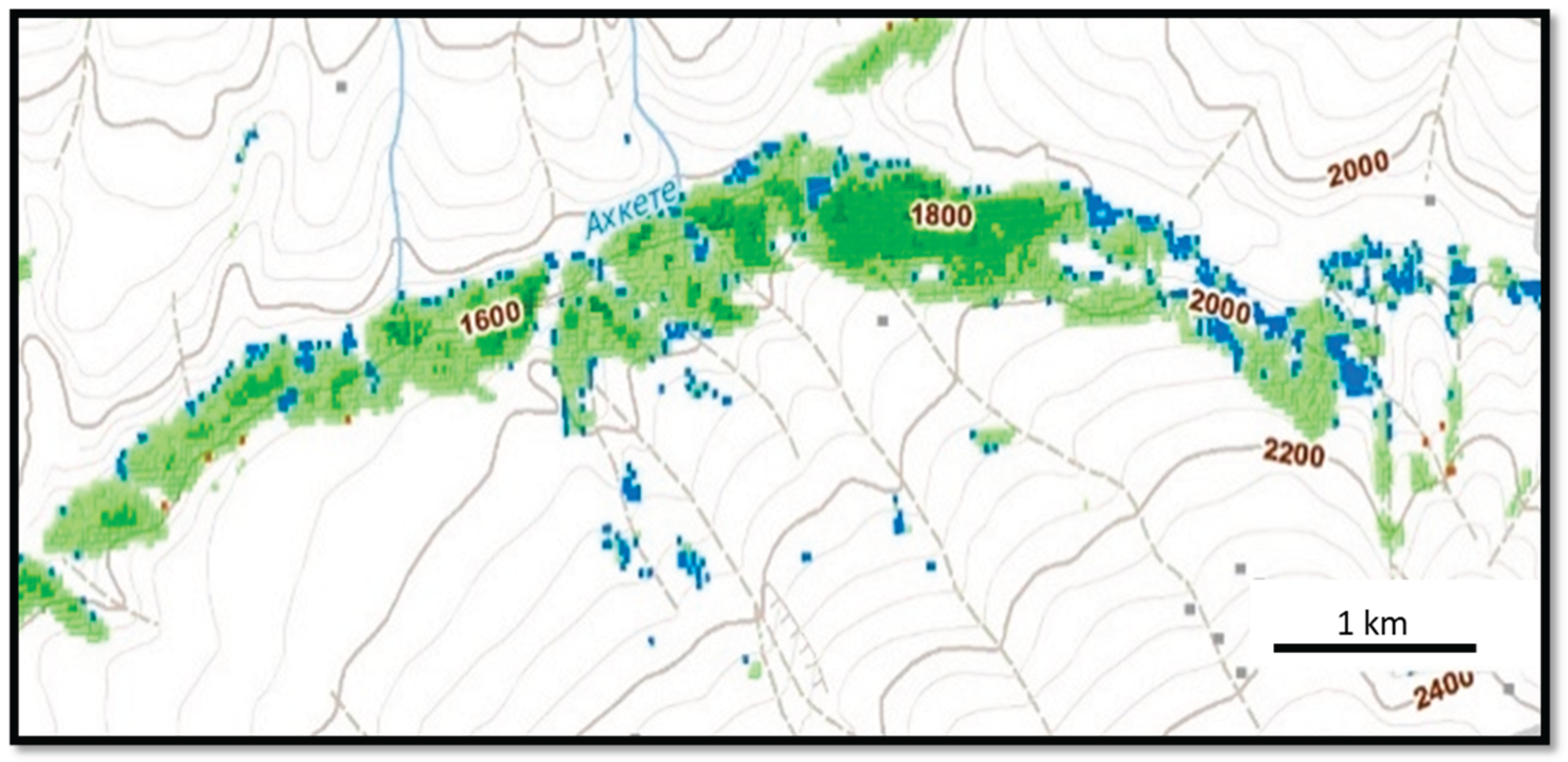

4.3. Current Dynamics of Mountain Forestscapes

- Mountain forestscapes of the Makazhoi intermountain basin

| Ecotones (see Figure 12) |

Until the mid-19th century | From the mid-19th century to 1944 | 1944-1991 | From the 2000s to the present day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Family, teip. Settlements, winter pastures | Collective use of pasture | Winter pastures in actual use by families, teips. Settlements | |

| 2-3 | Family, tape. Settlements, arable land, hay-fields |

De facto: family, tape, private owner-ship. Settlements, arable land, hayfields, recreation | ||

| 4 | Collectively used pastures, all-season | |||

| 5-6 | Common use forests | state forests | ||

| 7 | Family, tape. Settlements, hayfields, pastures |

Collectively used pastures | De facto: family, tape. Settlements, hay-fields, pastures, rec-reation |

|

| 8-9 | Collectively used pastures, mainly summer pastures | |||

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHAMR | The Argun Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve |

References

- Price, M.F.; Gratzer, G.; Duguma, L.A.; Kohler, T.; Maselli, D.; Romeo, R. Mountain forests in a changing world: realising values, addressing challenges. FAO, Rome, Italy, 2011, p. 84. [CrossRef]

- Berger, F.; Rey, F. Mountain Protection Forests against Natural Hazards and Risks: New French Developments by Integrating Forests in Risk Zoning. Natural Hazards, 2004; 33, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, P.; Das, S.; Hölscher, D.; Pierick, K.; Seidel, D. Drivers of Forest Structural Complexity in Mountain Forests of Nepal. Mountain Research and Development, 2025; 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T; Soma, T. Local Ecological Knowledge, Reforestation, and Vegetation Recovery: A Remote Sensing Based Assessment in Gandaki Province, Nepal. Mountain Research and Development, 2025; 45, 14–24. [CrossRef]

- Undurraga, T.; Márquez, F. The Unfinished Development of the Frontier: A Karl Polanyi Reading of the Conflict between the Forestry Industry, Mapuche Communities and the Chilean State. Sociologia and Antropologia, 2023; 11, 1, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinyue, H.; Alan, D. Z.; Paul, R. E.; Yu, F.; Jessica, C.A. B.; Shijing, L.; Joseph, H.; Dominick, V. S.; Zhenzhong, Z. Accelerating global mountain forest loss threatens biodiversity hotspots. One Earth, 2023; 6, 3, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.F.; Butt, N. Forests in sustainable mountain development: a state of knowledge report for 2000. CABI, Wallingford, 2000; p. 590. https://doi. org/10.1079/9780851994468.0004.

- Sarmiento, F. O.; Rodríguez, J.; Yepez-Noboa, A. Forest transformation in the wake of colonization: The Quijos Andean-Amazonian Flank, Past and Present. Forests, 2022; 13, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrer, F.; Walsh, K.; Mocci, F. Ecology. Economy, and Upland Landscapes: Socio-Ecological Dynamics in the Alps during the Transition to Modernity. Hum Ecol, 2020; 48, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwörer, C.; Colombaroli, D.; Kaltenrieder, P.; Rey, F.; Tinner, W. Early human impact (5000–3000 BC) affects mountain forest dynamics in the Alps. Journal of Ecology, 2015; 103, 2, 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, J. K. Toward Adaptive Community Forest Management: Integrating Local Forest Knowledge with Scientific Forestry. Economic Geography, 2002; 78, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. S.; Gunderson, L. H.; Ludwig, D. In quest of a theory of adaptive changes. Panarchy: understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Gunderson, L.H.; Holling, C.S. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA, 2002, pp. 3-22.

- Fausto, O. S.; Gunya, A.N. An Introductory Cautionary Note on Mountain Terminology. In: Mountain Lexicon. A Corpus of Montology and Innovation. Springer Cham. 2024; 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Purekhovsky, A.G. : Gunya, A.N.; Kolbowsky, E.Yu., Aleinikov, A.A. Methods of Studying The Alpine Treeline: A Systematic Review. Geography, Environment, Sustainability 2025; Volume 18, pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M. Vegetationszonen der Erde. Gotha; Stuttgart: Klett-Perthes, Germany, 2001; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Pini, R.; Ravazzi, C.; Raiteri, L.; Guerreschi, A.; Castellano, L.; Comolli, R. From pristine forests to high-altitude pastures: an ecological approach to prehistoric human impact on vegetation and landscapes in the western Italian Alps. Journal of Ecology, 2017; 105, 1580–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlanetto, G.; Perego, R.; Caccianiga, M. S.; Comolli, R.; Ferigato, L.; Frigerio, G.; Ravazzi, C. Pastoralism and mining activities affecting timberline ecosystems in the Italian Alps during the last millennia. Anthropocene, 2025; 51, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandra, F.; Vitali, A.; Urbinati, C.; Weisberg, P. J.; Garbarino, M. Patterns and drivers of forest landscape change in the Apennines range, Italy. Regional Environmental Change 2019, Volume 19, pp. 1973–1985. 2019; 19, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleinikov, A.A.; Aleksutin, V.E.; Vozmitel, F.K.; Gunya, A.N. Long-term dynamics of forests with Pinus sibirica in the upper reaches of the River Kolva (Northern Pre-Urals, Russia) from 1938 to 2023. Nature Conservation Research, 2024; 9, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E.G.A.; Austrheim, G.; Grenne, S.N. Landscape change patterns in mountains, land use and environmental diversity, Mid-Norway 1960–1993. Landscape Ecology, 2000; 15, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy-Sais, S.; Castillo, A.; Garcia-Frapolli, E.; Ibarra-Manriquez, G. Ecological variability and rule-making processes for forest management institutions: a social-ecological case study in the Jalisco coast, Mexico. International Journal of the Commons, 2016; 10, 1144–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M. A.; Anderies, J. M.; Ostrom, E. . Robustness of SocialEcological Systems to Spatial and Temporal Variability. Society & Natural Resources, 2007; 20, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A. General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science, 2009; 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.; McKean, M.A.; Ostrom, E. People and Forests: Communities, Institutions and Governance. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; p. 274.

- Ostrom, E. Designing complexity to govern complexity. Property rights and the environment: social and ecological issues. Beijer International Institute of Ecological Economics and The World Bank. Hanna, S.; Munasinghe, M., editors. Washington, D.C., USA, 1995; pp. 33-45.

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Haller, A.; Marchant, C.; Yoshida, M.; Leigh, D.S.; Woosnam, K.; Porinchu, D.F.; Gandhi, K.; King, E.G.; Pistone, M.; Kavoori, A.; Calabria, J.; Alcántara-Ayala, I.; Chávez, R.; Gunya, A.; Yépez, A.; Lee, S.; Reap, J. 4D global montology: toward convergent and transdisciplinary mountain sciences across time and space. Pirineos, 2023; 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.К. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge, Cambridge UP, USA, 1990, p. 152.

- Molnar, Z.; Gelleni, K.; Margotsi, K.; Biro, M. Landscape ethnoecological knowledge base and management of ecosystem services in a Székely-Hungarian pre-capitalistic village system (Transylvania, Romania). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2015, Volume 11(3), p. 40. [CrossRef]

- Jenal, C. , Berr, K. Wald in der Vielfalt Möglicher Perspektiven: Von der Pluralität Lebensweltlicher Bezüge und Wissenschaftlichen Thematisierungen. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; p. 542. [CrossRef]

- Bolte, A.; Ammer, C.; Löf, M.; Madsen, P.; Nabuurs, G.-J.; Schall, P.; Spathelf, P.; Rock, J. Adaptive forest management in central Europe: Climate change impacts, strategies and integrative concept. Journal of Forest Research, 2009; 24, 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- James, C. S. . Seeing like a state. Yale University Press, USA, 1998; p. 464.

- Arnold, J. E. M. . Managing forests as common property. FAO Forestry Paper 136. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, 1998, pp. 59-64.

- Tucker, C.; Hribar, M.; Urbanc, M.; Bogataj, N.; Gunya, A.; Rodela, R.; Sigura, M.; Piani, L. Governance of interdependent ecosystem services and common-pool resources. Land Use Policy, 2023; 127, 106575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townshend, J. R. Improved Global Data for Land Applications: a Proposal for a New High Resolution Data Set, in Report of the land cover working group of IGBP-DIS. IGBP Secretariat; the Royal Swedish Academy of Science, Sweden, 1992; p.87.

- Lambin, E.F.; Turner, B.L.; Geist, H.J.; Agbola, S.B.; Angelsen, A.; Bruce, J.W.; Coomes, O.T.; Dirzo, R.; Fischer, G.; Folke, C.; George, P. The causes of land-use and land-cover change: moving beyond the myths. Global environmental change, 2001, Volume 11(4), pp. 261-269.

- Lambin, E.F. , Geist, H.; Rindfuss, R.R. Introduction: local processes with global impacts. In Land-use and land-cover change. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Verburg, P.H.; Erb, K.H.; Mertz, O.; Espindola, G. Land System Science: between global challenges and local realities. Current opinion in environmental sustainability 2013, Volume 5(5), pp. 433-437.

- Purekhovsky, A. Zh.; Gunya, A. N.; Kolbovsky, E. Y. Dynamics of high-mountain landscapes of the North Caucasus based on remote sensing data for 2000–2020. Proceedings of Dagestan State Pedagogical University. Natural and Exact Sciences, 2022; 16, 72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Alekseeva, N.N. , Gunya, A.N., Cherkasova, A.A. Dynamics of land cover in mountain protected natural areas of the North Caucasus (based on the example of the Alania National Park). Bulletin of Moscow State University, Series 5, 2021; 2, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Petrushina, M. N.; Gunya, A. N. Semiarid Intermontane Basins of the North Caucasus: Landscapes and Land Use Transformations. Arid Ecosystems, 2021; 11, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Adat. Caucasian Cultural Circle. Traditions and Modernity. Dmitriev V.A. (ed.). International Research Institute of the Peoples of the Caucasus. Moscow-Tbilisi, MNIINK, 2003. (In Russ.).

- Potapov, P.; Hansen, M. C.; Kommareddy, I.; Kommareddy, A.; Turubanova, S.; Pickens, A. Landsat Analysis Ready Data for Global Land Cover and Land Cover Change Mapping. Remote Sensing, 2020; 12, 426. [Google Scholar]

- Purekhovsky, A. G. , Petrov, L. A., Kolbovsky E. Yu., Sonyushkin, A. V. Big Data for Assessing the Ecological Rehabilitation of Cultural Landscapes in Mountainous Chechnya. Dagestan State Pedagogical University. Journal. Natural and Exact Sciences, 2022; 16, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Potapov, P.; Li, X.; Hernandez-Serna, A.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M. C.; Kommareddy, A.; Pickens, A.; Turubanova, S.; Tang, H.; Silva, C.E.; Armston, J.; Dubayah, R.; Blair, J. B.; Hofton, M. Mapping Global forest Canopy Height through Integration of GEDI and Landsat Data. Remote Sensing Environ, 2021; 253, 112165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toropov, P.A.; Aleshina, M.A.; Grachev, A.M. Large-scale climatic factors driving glacier recession in the Greater Caucasus, 20th–21st century. International Journal of Climatology, 2019; 39, 4703–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunya, A.; Lysenko, A.; Lysenko, I.; Mitrofanenko, L. Transformation of Nature Protection Institutions in the North Caucasus: From a State Monopoly of Governance to Multi-Actor Management. Sustainability, 2021; 13, 12145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debarbieux, B.; Rudaz, G. The mountain: a political history from the enlightenment to the present. The University of Chicago Press, USA, 2015; p. 354.

- Debarbieux, B.; Price, M. F.; Balsiger, J. The institutionalization of mountain regions in Europe. Regional Studies, 2013; 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgärtner, J.; Tikubet, G.; Gilioli, G. Towards adaptive governance of common-pool mountainous agropastoral systems. Sustainability, 2010; 2, 1448–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Phalan, B.T. What have we learned from the land sparing-sharing model? Sustainability, 2018; 10, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunya, A.N.; Gairabekov, U.T.; Makhmudova, L.Sh. Features of the biogeocycle and carbon dynamics in the landscape ecotone ‘mountains – plains’ (based on the example of the Carbon polygon of the Chechen Republic). South of Russia: ecology, development, 2025; 20, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Rodríguez, V.; Fahrig, L.; Tabarelli, M.; Watling, J.I.; Tischendorf, L.; Benchimol, M.; Cazetta, E.; Faria, D.; Leal, I.R.; Melo, F.P.L.; Morante-Filho, J.C.; Santos, B.A.; Arasa-Gisbert, R.; Arce-Peña, N.; Cervantes-López, M.J.; Cudney-Valenzuela, S.; Galán-Acedo, C.; San-José, M.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Slik, J.W.F.; Nowakowski, A.J.; Tscharntke, T. Designing optimal human-modified landscapes for forest biodiversity conservation. Ecology Letters, 2020; 23, 1404–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongruel, R.; Prou, J.; Ballé-Béganton, J.; Lample, M.; Vanhoutte-Brunier, A. ; Réthoret,H.; Agúndez, J. P.; Vernier, F.; Bordenave, P.; Bacher, C. Modeling soft institutional change and the improvement of freshwater governance in the coastal zone. Ecology and Society, 2011; 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Forest subtypes | Seasonal maximums of above-ground phytomass, dry weight (t/ha) | Average number of tree-shrub/herbaceous species |

|---|---|---|

| Forest-meadow | 20-30 | 2-3/30-40 |

| Small-leaved and coniferous-small-leaved | 50-100 | 3-5/40-50 |

| Broad-leaved | 200-360 | 6-8/10-15 |

| Meadow-steppe shrub | 2-7 | 5-8/40-60 |

| Forest-steppe |

5 (up to 50 in park groves) |

5-7/30-50 |

| Nival-glacial | High-altitude meadows | High-altitude forests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease | Growth | Decrease | Growth | Decrease | Growth | |

| Area ha | 6 521,98 | 0 | 39 785,39 | 20 906,25 | 14 384,27 | 39 785,39 |

| % | 100% | 0 | 65,55% | 34,45% | 26,55% | 73,45% |

| Total ha | 6 521,98 | 60 691,64 | 54 169,66 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).