1. Introduction

The threat of temperate forest degradation due to the effects of climate change is steadily escalating [

1,

2,

3]. Forests provide numerous indispensable ecosystem services, especially the reduction and storage of atmospheric carbon [

4,

5], cooling of the land surface [

6,

7] and regulation of the hydrosphere [

8,

9]. Consequently, the loss of trees, and therefore vital forest structure, compromises the climate buffering function of forests (Mann et al., 2023). Reduced forest area together with an increase in the number of isolated forest patches can furthermore have consequences for forest species and ecosystem functioning as interactions between them may change unpredictably. Thus, analyzing spatial patterns of forests is essential for understanding their role in maintaining biodiversity, supporting ecosystem functions, and enhancing climate resilience.

1.1. Fragmentation Versus Forest Loss

Fragmentation refers to the discontinuous pattern of forest patches within a landscape. Such patterns can arise from human activities (logging, historical land use or land use conversion, construction of infrastructure, soil pollution), from natural causes (windthrow, insect infestations, drought, floods, wildfire), the underlying properties of the substrate (soil type & texture, hydrology, persistence of rock outcrops) or other biophysical constraints (temperature, elevation/terrain, precipitation, solar irradiance) which contribute to the natural patchiness of landscapes. The combination of these drivers results in a landscape mosaic, which is characterized by a spatially uneven distribution of landcover types, comprised of for example forests, agriculture, water bodies, and infrastructure. Except for the most remote forests, anthropologically developed regions exhibit patchy forest patterns. In other words, landscape patchiness is the rule, not the exception [

11,

12].

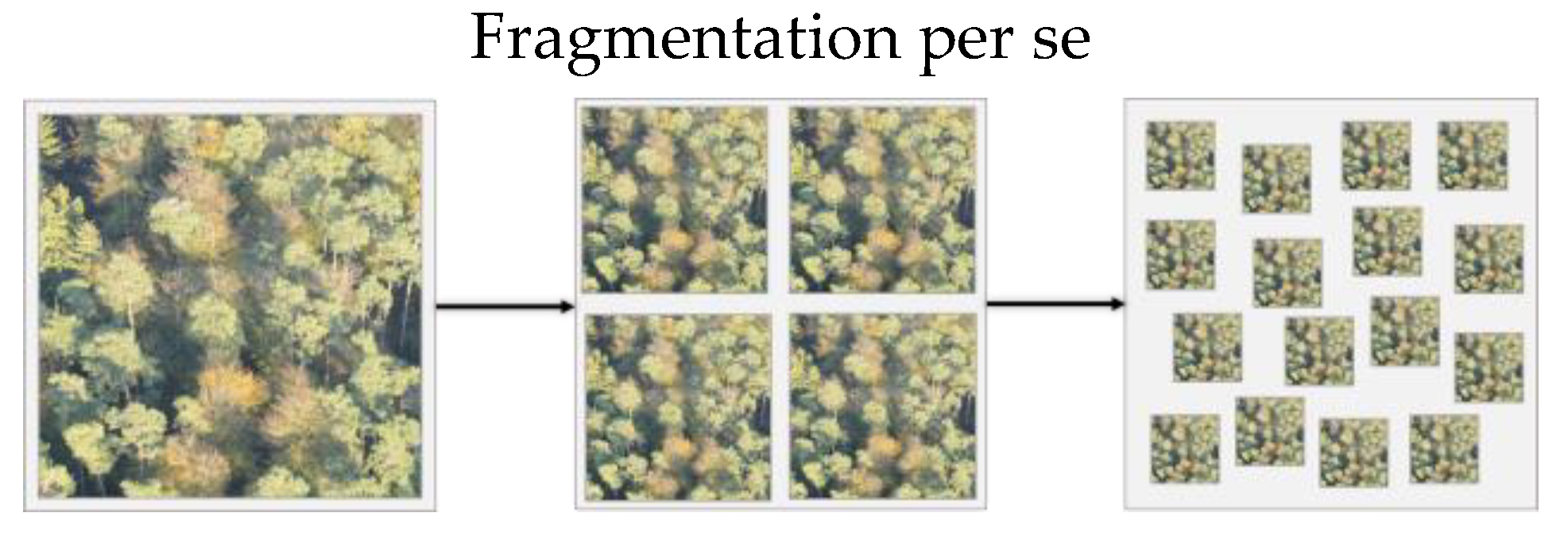

Fragmentation occurs when forests are broken apart into more numerous and disconnected patches, and can be considered as a distinct process from habitat loss [

13,

14]. With fragmentation per se, patches can become disconnected but the same amount of habitat area within a given landscape can still be maintained. Habitat loss, on the other hand, is a process whereby the area of forest is reduced over time.

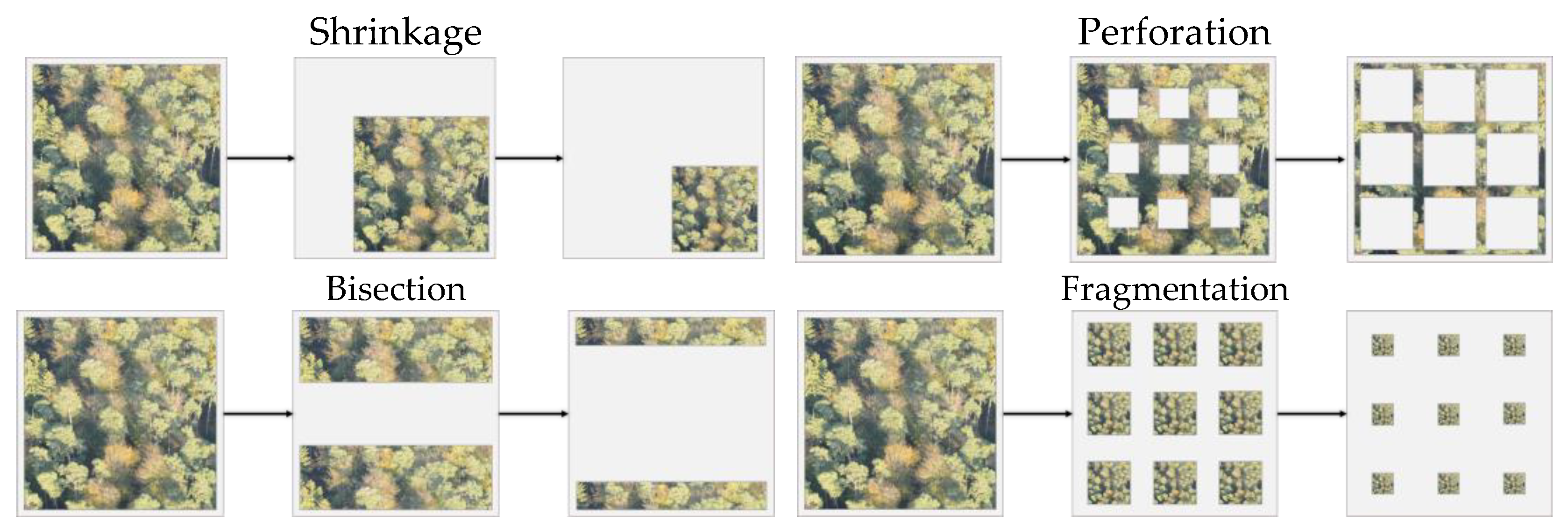

Figure 1 illustrates this concept using four scenarios of habitat loss. In the first frame, the forest covers 100% of the landscape, in the next the forest is reduced to 50%. Finally, the forest is reduced to 25% of the original size in the last frame. In the shrinkage scenario, forest habitat is lost, but not fragmented. This is also true in the perforation scenario, because forest connectivity is maintained even as the forested area is reduced.

Bisection and fragmentation are characterized by the dis-connectivity of forest area, which we refer to as fragmentation. The figure illustrates both forest loss and fragmentation of remaining habitat but it is important to distinguish this phenomenon from landscapes where the overall forest area is maintained across an increased number of individual patches. This scenario is typically referred to as ‘fragmentation per se’ as opposed to merely fragmentation [

15].

Figure 2 exemplifies the fragmentation of forest without a reduction in overall forest area within the landscape. This distinction is significant, because the maintenance of habitat area within a specified landscape despite fragmentation, can still support animal habitats and ecosystem functioning [

13].

Because of the heterogeneity of landscapes, the degree of fragmentation of forests within them is variable. To understand the relative intensity of fragmentation, it is useful to assess landscape patterns in terms of forested area and number of fragments, or the ‘patchiness’ of forests, within the landscape.

Table 1 summarizes the degree or intensity of expected fragmentation based on these factors, resulting in different levels of forest fragmentation.

1.2. Aggregation and Isolation

Although disconnected patches may have altered functional capacity in terms of ecosystem services, biodiversity, habitats and resilience against the effects of climate change [

17,

18,

19], counterintuitively, fragmentation can favor some species whilst disadvantaging others. This depends on the scale, distribution (isolation or aggregation of patches), cause, frequency and degree of forest loss (if any) and the affected species. This paradox has been investigated in a wide range of habitat types, climate zones and under various drivers of habitat loss [

16]. In the majority of cases, Fahrig et al. determined a net positive effect of fragmentation independent of habitat loss.

Furthermore, while larger forests reliably support more species, disconnected habitats can genetically isolate populations thereby contributing to speciation over long time scales. However, the lack of incoming genetic diversity can also lead to population decline. Moreover, reduction in habitat area predictably reduces species richness within patches. These principles were the foundation of the theory of island biogeography [

20].

Although initially developed for oceanic islands, this theory came to dominate the conceptual understanding of early investigations of fragmented terrestrial habitats. However, it is important to note that islands in an ocean are not directly analogous to terrestrial habitat patches. Forests are embedded in a mosaic of other landcover types that have distinctive properties which can facilitate or hinder animal movement and plant dispersion. To simplify this concept, we focus on the number of neighboring forests to each forest and their distance to understand the isolation or aggregation of forest patches within a landscape.

Table 2 summarizes these concepts below.

The degree or intensity of patch isolation can thus limit or enhance the quality and quantity of species interactions. Species interactions drive underlying processes such as forest seed dispersal by birds or rodents, the movement of pathogens or infectious diseases, facilitation of gene flow or reproduction. These processes require the interaction of species within available habitat which is further modulated by habitat configuration and distribution. Fragmentation of forests therefore has species-specific effects.

1.3. Edge Structure

In unmanaged forests, where human inventions are minimal or absent, forest is lost by the aforementioned natural causes which occur at less frequent intervals than anthropogenic drivers, but can nevertheless cover large spatial areas. However, remaining forest structure (vertical layers, lying deadwood) and perimeter morphology (straight versus sinuous) are typically more heterogenous compared to human-caused forest loss [

11,

12,

21]. The resulting structural differences between natural and anthropogenic fragmentation can favor some forest species while harming others. This is especially true for the region where interior forest is lost (perforated) where, like forest edges, microclimatic conditions differ from the interior of a forest. These abiotic conditions can furthermore be modulated by the remaining forest structure, perimeter morphology, and the adjacent landcover type [

21]. This may increase biodiversity by favoring generalist species which can easily colonize disturbed areas and prefer higher light, temperature and windy conditions [

22].

Forest structure can vary by species, management practices, age class, and distance to the forest perimeter [

23]. For example, trees along a mature perimeter, where the vegetation has developed according to the edge conditions, often exhibit branches at lower positions on stems. Whereas a newly exposed (disturbed) perimeter, where trees had developed with greater light competition within the forest interior, branches tend to dominate higher positions. Thus, stems become exposed to abrupt changes in abiotic conditions. This difference in structure modulates a profound ‘edge-effect’ which is caused by the penetration of sunlight, thereby creating microclimatic conditions along perimeters and in edge zones [

24]. Although disturbances are usually transient, the effect on growth of surrounding trees can persist even after perforations or edges have regrown [

25].

Figure 3 characterizes the variability along a mature perimeter (A) and a recently disturbed perimeter (B, C) of spruce-dominated forest near Garmish-Partenkirchen (A, B) and Wessling (C).

To conceptualize the amount of edge in a forest or landscape, it is necessary to also account for the area of forests. If the overall amount of forest is large, the area where edge effects occur is relatively small. By the same token, in landscapes or patches with a small forested area, perimeters and thus edge effects, will tend to dominate the forest. This is significant, because trees stressed by temperature may be less resilient to droughts, insect infestations, or other disturbances [

26].

Table 2 summarizes the so-called edginess potential for different ratios of forest area to perimeter length.

Table 2.

The ‘edginess’ or amount of edge is a function of the length of the perimeter of forest patches and the area of patches within the landscape.

Table 2.

The ‘edginess’ or amount of edge is a function of the length of the perimeter of forest patches and the area of patches within the landscape.

| Perimeter length |

Patch area |

Interpretation |

Edginess |

| High |

Low |

Patches are likely long and narrow with very little if any core area |

High |

| High |

High |

Patches are large and may have numerous perforations, edge effects are likely minimal |

Low to moderate |

| Low |

Low |

Patches are likely small, geometric, perhaps without any core area |

Moderate to high |

| Low |

High |

Patches may be medium sized with few or small perforations |

Low |

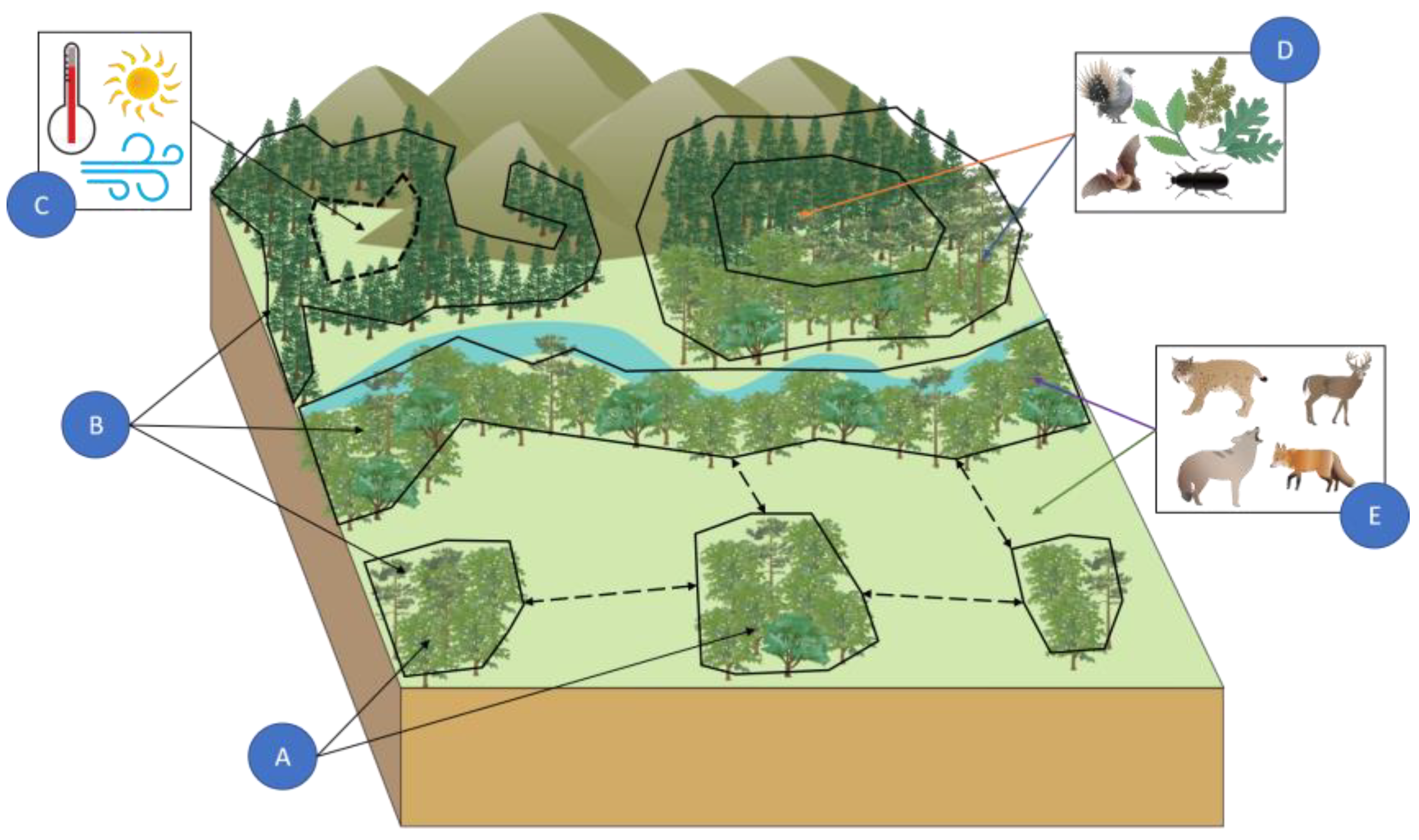

Geospatial forest fragmentation analysis focuses on three essential zones of the forest; the perimeter, edge zone, and the core of individual patches. The edge zone is a transitional region of forest up to 100m interior to a forest perimeter which can act as a microclimatic buffer for the core zone, which is the remaining interior region [

27]. Depending on management practices, perimeters and edge zones usually exhibit different biotic and abiotic characteristics and conditions compared to forest interiors in addition to increased occurrence of invasive species (

Figure 4, A-E) [

28].

1.4. Fragmentation Analysis

Importantly, fragmentation must be analyzed within the context of a defined landscape area [

30]. Characteristics of forest patches such as amount & distribution, perimeter length, core and edge area, shape, and neighboring patch configurations can then be aggregated within landscape boundaries. Landscapes can thus be utilized as units for ecological investigations, for example investigations regarding forest species abundance based on total habitat amount within or amongst discontinuous patches. To determine the intensity of fragmentation, the number of fragments, patch distribution, and edginess can then be related to the remaining metrics within a landscape unit.

Analysis of remotely sensed imagery is an effective approach for monitoring forest condition and disturbance [

31], is an under-utilized tool in the study of forest fragmentation, and is furthermore ideal for large-scale applications [

32]. Given the profound differences between fragmented forests and contiguous forest ecosystems [

33], an assessment of fragmentation in the largest and most forested state in Germany is needed. Furthermore, the topic has not yet been investigated on the state-scale using Earth observation (EO) data [

34]. Understanding landscape patterns and processes is moreover important for the formulation and assessment of forest management strategies within the context of climate change and conservation. Therefore, fragmentation across Bavaria can be efficiently investigated by analyzing satellite data and is the subject of this inquiry. We present:

A characterization of forests using structural and functional fragmentation metrics based on patch size categorization

The spatial and terrain distribution of fragmentation

State-, county-, and district-level results which can support data-driven forest policy and management decisions

3. Results

We delineated 83,253 individual forest polygons (hereafter patches) which contained roughly 2.384 million hectares of forest in Bavaria. Patches ranged in size from 0.1 (based on the minimum forest size, defined by the German Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Regional Identity, BMEL [

59]) to ~ 48,703 hectares, however the distribution of patch sizes is not normal.

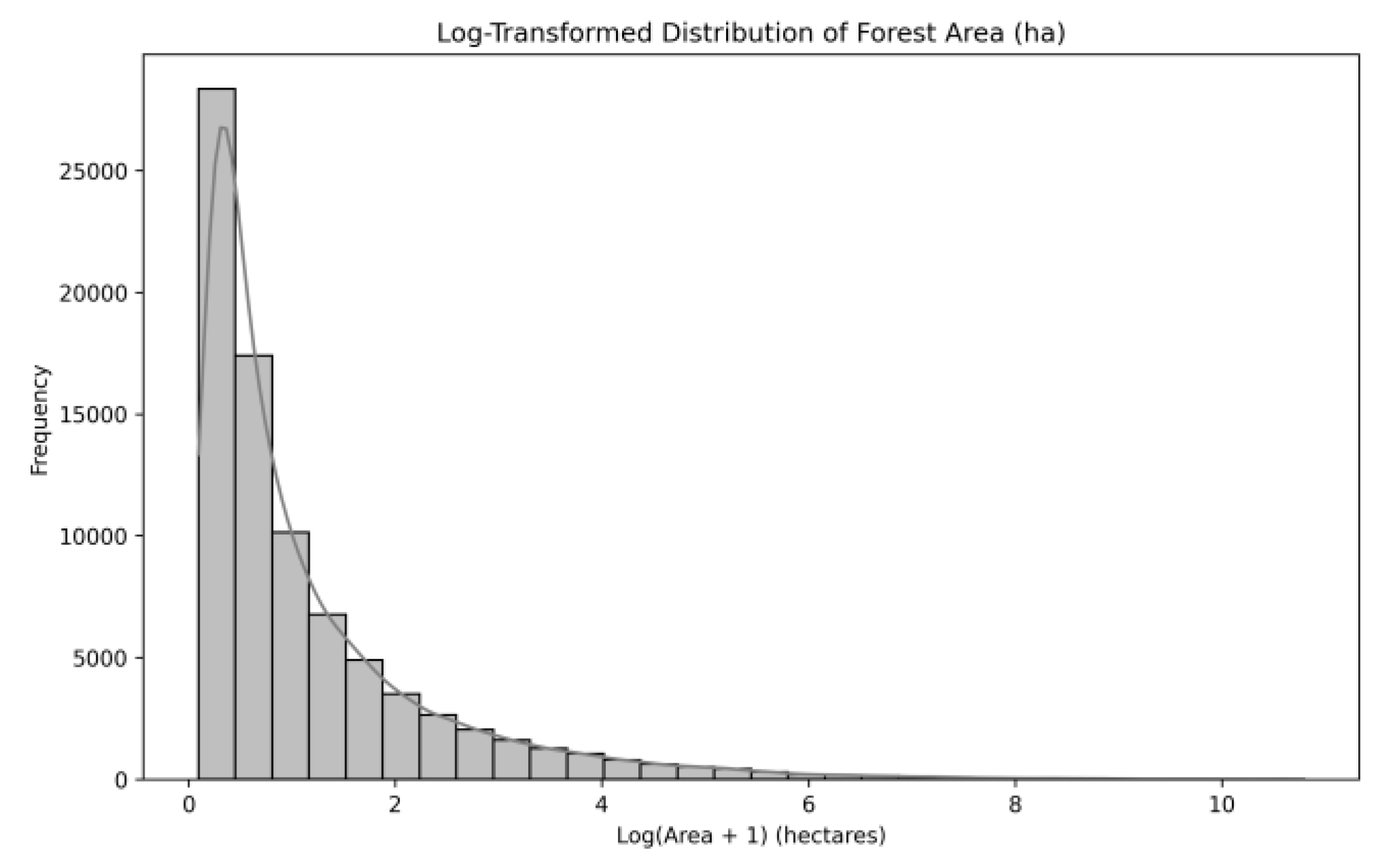

Figure 7 visualizes the distribution of patch sizes after applying a log-transformation of the data. Due to the skewed nature of these data, we present the fragmentation characterization in categories based on forest patch size.

Size categorization or binning was performed on the state-wide dataset using the Jenks-Caspall method [

60] for clustering geospatial data. JenksCaspall optimizes bins to minimize variance within and maximize differences between bins, and is therefore well-suited for skewed data. The operation was conducted using the mapclassify library in Jupyter Lab (version 4.0.6) using Python (version 3.10.12), resulting in 5 size bins. The smallest size bin, 0.1-25 hectares is hereafter referred to as the XS size class. In order of increasing forest size, patch categorization is as follows: 25-160 hectares (S), 160-789 hectares (M), 785-3,594 hectares (L), and 3,594-48,703 hectares (XL).

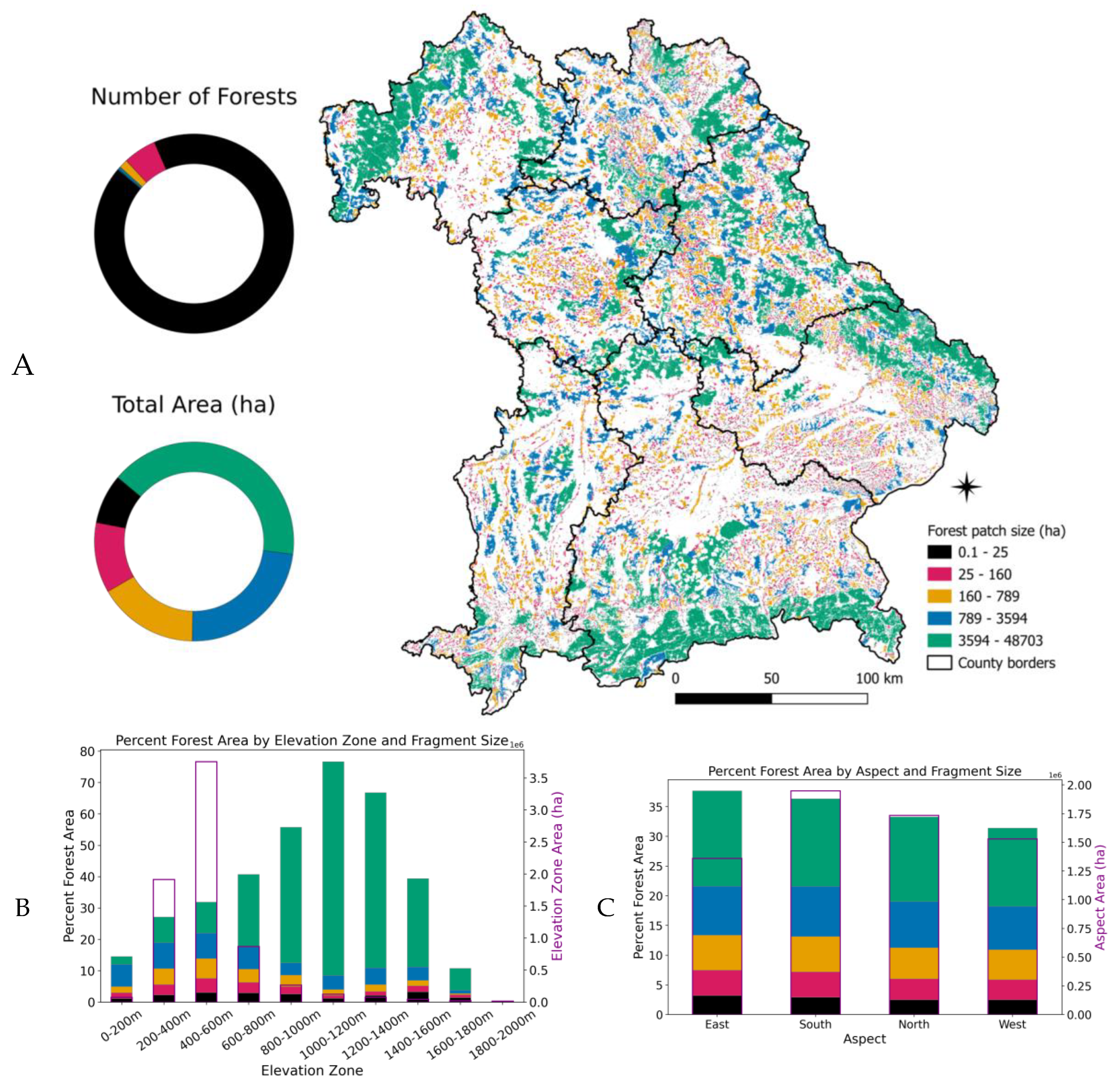

The spatial distribution of patch sizes across the state of Bavaria is heterogenous. The largest forest polygons are located around the periphery of the state, namely in the northwest corner of Lower Franconia, the central and eastern regions of Upper Franconia, Upper Palatinate, and Lower Bavaria, and the southern regions of both Swabia and Upper Bavaria. The distribution roughly follows both the terrain of the state, with the largest contiguous forest polygons located at higher elevations, as well as the areas with a status of varying degrees of forest protection as nature areas, reserves, or parks at both the state and federal levels.

Figure 8 (A) presents an overview of the spatial and size category distribution with inset examples of fragmentation patterns.

Figure 8 (B and C) summarize the distribution of patches with regards to terrain. In

Figure 8 (B), above 2000m there is no forest cover and was therefore omitted from this figure. The total area of each elevational zone is represented on the right y-axis with bars outlined in black (1x10

6 ha). The 1000-1200m elevational zone contains the highest percent of forest cover at just over 60% however this zone is among the smallest, covering about 120,000 ha. The lowest elevational zone, 0-200m, is covered by less forest than each subsequent zone until the climatic conditions limit tree growth above 1400m. The smallest forest patches are relatively evenly distributed across the elevational zones compared to L and XL patches which make up the largest share of forest coverage as elevation increases. Most of the land surface area of the state falls within the 400-600m elevation zone (about 3.75 million ha), however only about 30% is covered by forested area.

The total area is not evenly distributed amongst the four aspect directions (

Figure 8 C). The majority of slopes are south-facing and have the second highest percent forest cover. The smallest slope category was East; however, these slopes have the highest percent coverage of forest. West-facing slopes had the smallest coverage overall.

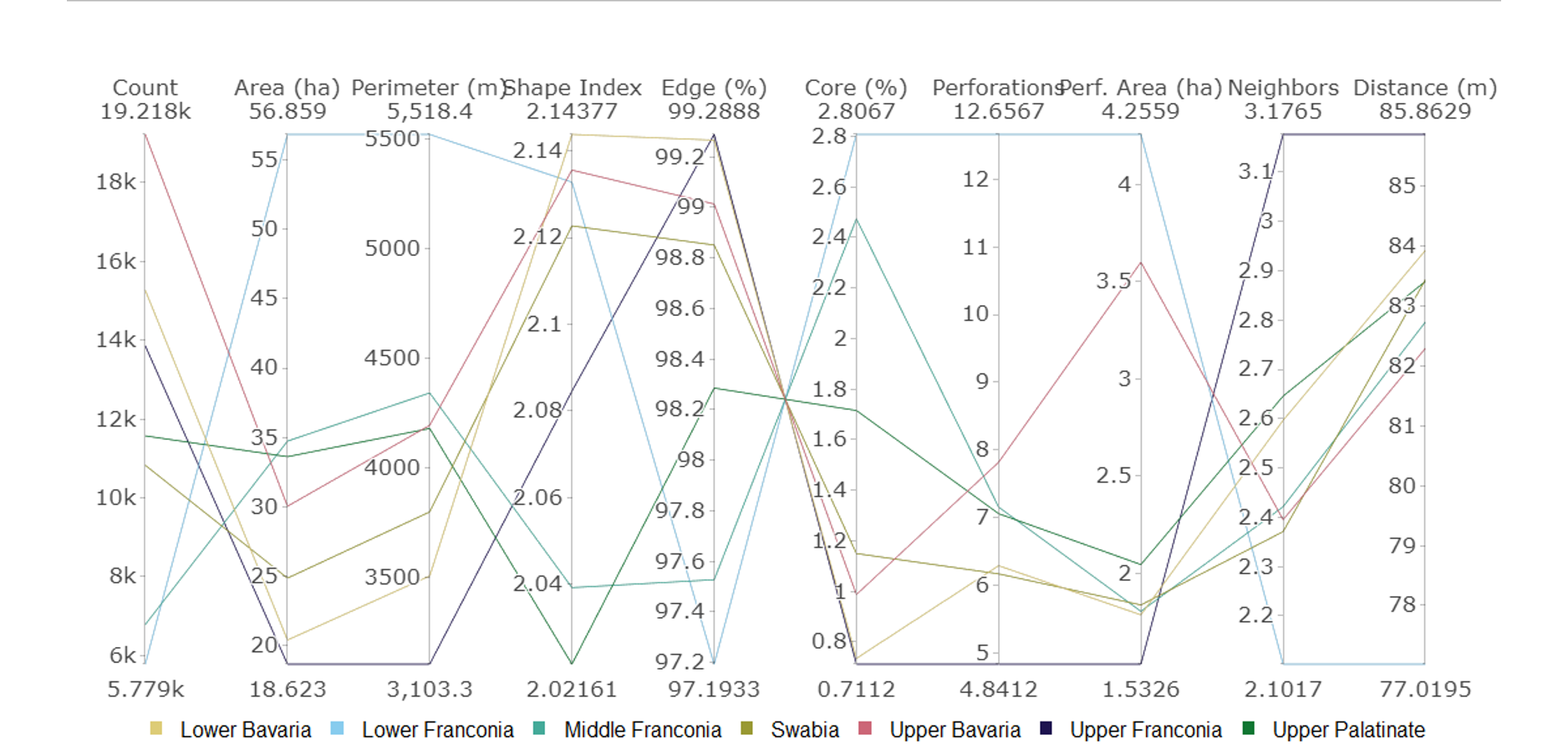

Figure 9 visualizes the state-wide results of forest fragmentation pattern characterization covering the whole of Bavaria using min-max scaling. Results are organized by the abovementioned patch size bin categorization. For detailed results tables for the state and each county of Bavaria, we refer the reader to the

Supplementary Materials.

3.1. Area and Number of Patches

Most forests (77,175 patches) were categorized as XS (< 25 ha), however this category covered the smallest area overall. More than 92% of forest patches cover an area less than 25 ha each, with a total area of 192,177 ha or about 8% of the total forested area in the state. The mean area of XS patches was 2.5 ha and this varies by district. The largest patches (XL), those at least 3,594 ha cover a total of 976,504 ha amongst 101 patches, which is 41% of forested area in Bavaria. Upper Bavaria had both the largest area of XL patches (296,475 ha) distributed amongst 21 forest polygons, and the highest number of XS forest patches (17,847).

3.2. Core and Edge Area

A 100m edge depth was considered in this analysis. The remaining interior forest area not contained within the edge zone is considered core forest. Among the XS fragments, 99.8% lies within the 100m edge zone. The resulting mean core areas in these patches is 0.2 ha. Edge and core area increased with increasing patch size category. However only among patches L or larger is the average core area higher than 30%. This suggests the patch shape is highly irregular, with longer perimeter lengths and more perforations with respect to forest patch areas. For the largest fragments (XL), the average core area is 38%.

3.3. Perimeter

Total perimeter length did not have a strictly positive or negative correlation with patch size category. Instead, both the XS patch and XL patch categories had the longest total perimeter lengths; about 83.9 and 84.6 million meters respectively. Whereas the S, M, and L patch size categories had total perimeter lengths of ~51.5, ~52, and ~57 million meters respectively. Due to the total length of perimeter and small individual patch areas, the perimeter-area ratio, or ‘paratio’, was highest among fragments in the XS category.

3.4. Shape

Patch shape was measured using two metrics; the ‘paratio’ and the shape index. Paratio decreased with increasing patch size, which reflects the larger patch area with respect to patch perimeter length. Shape index increased with patch size which suggests an increase in shape complexity, meaning shapes diverge from simple geometric forms (circles, squares). Shape complexity also increases with the occurrence of perforations (see

3.5.). In

Figure 10, we present examples of increasing shape complexity (A-H).

3.5. Perforations

The number and total area of forest perforations or gaps increased with patch size and varied widely between counties. Less than one gap existed per XS patch on average meanwhile the largest fragments contained on average more than 2,300 gaps across the state. Upper Bavaria had the largest area of perforations (69,164 ha), while Middle Franconia had the smallest area (12,237 ha).

3.6. Neighborhood

With respect to functional fragmentation, the patterns were not necessarily linearly correlated to patch size. Instead, XS forests had the highest total number of neighboring patches within a 200m buffer area, followed by S, M, XL, and L fragments. However, the average number of neighbors increases based on patch size category. XS patches on average have 2.1 neighbors which increased with each successive larger patch. XL patches had an average of 99 neighbors each. Although the mean area of neighboring forest polygons varied by patch size, neighboring forest patches to XL fragments were on average the largest compared to other patch sizes.

The distance between neighboring patches also varied between patches sizes and counties. In general, the distance between patches increased depending on the size of the patch. The nearest or most aggregated patches were among the XL patches and surrounding neighboring patches in Lower Franconia which were on average 58.3 meters apart (considering patches within the 200m buffer), while the longest distance between neighbors on average was 86.3 meters amongst the XS patches in Upper Franconia.

3.7. Spatial Distribution

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 visualize the spatial distribution of fragmentation density patterns, aggregated at the district level in Bavaria. The metrics have been normalized by district area in order to make meaningful comparisons, and the sparse data within municipalities has been masked (grey polygons) to remove noise from the district dataset.

3.7.1. Patch Count Density

Kronach district in the northeastern region of Bavaria has the highest density of forest fragments (total number of fragments normalized by district area), followed by neighboring Kulmbach and Hof districts, and Passau district in the east.

Figure 11 (A, a) highlights the high number of fragments in Passau district. Districts with lower patch densities were more evenly distributed across the state, with the county surrounding the city of Munich in the southern district of Upper Bavaria having the lowest density of patches per district area.

3.7.2. Area Density

Districts with the largest total forest area with respect to district area include Main-Spessart (inset,

Figure 11 B, b), Aschaffenburg and Miltenberg in Lower Franconia; Regen and Freyung-Grafenau (corresponding to the Bavarian Forest National Park - BFNP) in the east, and Miesbach, Bad Tolz-Wolfratshausen, and Garmisch-Partenkirchen districts in southern Upper Bavaria.

3.7.3. Core Area Density

The ratio of core forest with respect to the total area per district follows similar trends as the total forested area. Districts surrounding the city of Munich have the least core forest including Dachau, Freising, Erding, Landshut, and Mühldorf. Kronach district is shown in the inset map (

Figure 11 C, c) with low core forest area density.

3.7.4. Perimeter Density

Density of forest perimeter lengths tended to be higher in the north, east, and south of Bavaria. This was especially the case in Kronach and surrounding districts in Upper Franconia and the area surrounding the BFNP in the east. Oberallgau district is shown in the inset map (

Figure 11 D, d).

3.7.5. Shape Complexity Density

Figure 12 (A) presents the distribution of the mean shape complexity index. As the index increases, forest patch shape deviates from simple geometry becoming increasingly complex especially for patches with long perimeter lengths and perforations. Patch shape complexity is distributed relatively evenly across the state with some exceptions of low mean complexity including Cham and the districts surrounding Nuremburg (Forchheim, Erlangen-Höchstadt, and Fürth). The inset map (

Figure 12 a) presents the index in Altötting district where long narrow forest patches with perforations are common.

3.7.6. Perforation Density

Forest perforations (

Figure 12 B) are particularly abundant in districts Kronach, Regen, Freyung-Grafenau, Traunstein (inset map,

Figure 12 b), and Berchtesgadener Land which are also heavily forested districts, whereas districts with the smallest patch sizes also had the fewest number of forest gaps (those situated outside of Munich and Nuremberg). The highest density of perforations was found in the southern districts of Miesbach and Garmisch-Partenkirchen (inset map,

Figure 12 c); as well as in Berchtesgadener Land, Regen, and Freyung-Grafenau in the east. Eichstatt in the center of Bavaria north of Ingolstadt has a notable density of perforations, unlike the surrounding districts.

3.7.7. Perforated Area Density

The highest density of perforated area was found in Miesbach district followed by Garmish-Partenkirchen (

Figure 12 C and inset, c) and Regen districts. Berchtesgadener Land, Freyung-Grafenau, Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen, Eichstätt, Forcheim, and Miltenberg districts also had high densities of perforated area. Districts with the least perforated area density were also districts with the smallest overall density of forest area, namely those east of Munich in Upper and Lower Bavaria.

3.7.8. Neighborhood density

The number of neighboring patches found within a 200m buffer of every forest fragment was highest in Kronach district, a region with high total forest area and a high density of patches relative to the area of the district. In Donau-Ries district, forest patches have few neighboring patches, meaning forest patches are more isolated (

Figure 12 D, d).

4. Discussion

4.1. Number of Forests, Core Area, and General Distribution

Large forests represent roughly one-third of the total forested area of the state. The largest forests are located primarily in remote mountainous regions of the state, above 600 m.a.s.l., are typically state-owned, dominated by spruce and classified as parks or reserves.

The value of ecosystem services provided by large forests, including regulation of the hydrosphere, cannot be replaced by any other means [

8]. Therefore, the protection and management of large forests is vital [

61]. Large, continuous core areas are especially important for carbon reduction & storage, and land surface temperature regulation (Mann et al., 2023). In Bavaria, XL forest patches together contain over 180 times the core forest area of the XS patches combined. However, due to drought and bark beetle disturbances to spruce, recent large-scale forest loss has caused a major shift. Since 2017, the forests of Germany are now a source of carbon rather than a sink [

59]. How long this trend continues is a question of forest management particularly in terms of nature conservation and tree species composition.

Among the smallest patches, the ratio of edge to core is such that only a small percent of forest can provide valuable core-specific habitats and ecosystem services. Meanwhile edge effects dominate small forests and stress edge zone buffer trees, which can lead to further forest loss. Regardless, small forest patches can still deliver ecosystem services, provide habitats, and habitat connectivity across a landscape, and should therefore not be discounted as valueless [

13,

63]. In a study related to the effects of small woody features (comprised of trees and/or shrubs and smaller than XS forest patches) on land surface temperatures, the authors identified a cooling effect on adjacent agricultural fields which was modulated by patch orientation and shape [

64].

4.2. Perimeter, Edge Zones, Perforations, and Shape Complexity

Total forest perimeter length for the smallest patches (~83.9 mil m) was relatively similar to that of the largest forests (~84.7 mil m) in comparison to other forest sizes across Bavaria. Due to the apparent stochasticity of climate-driven tree mortality, forest patch shapes can become increasingly complex, therefore complex forest shapes contribute to the length of the forest perimeter. This exposes trees to so-called edge effects which vary considerably from conditions within the forest interior [

65]. The consequences can include degraded ecosystems, biodiversity loss, and disruptions to animal movement and plant dispersion as forest species run out of contiguous habitat [

63]. However, disturbance outcomes are not always unidirectional. Increased penetration of sunlight in gaps drives succession of forest species and moreover provides vital habitat, moisture retention, and nutrients via fallen deadwood.

Forest edges and interiors have distinctive microclimates which generate so-called edge effects. Vegetation structure, species composition, microclimate, nutrient cycling, and biodiversity within edges function as a buffer for forest interiors. This functionality is furthermore influenced by both latitude and management practices [

58]. Therefore, a gradient can exist between the perimeter of the forest, penetrating the depth of the edge zone towards the core.

Forest edges play an important role both as buffer zones for continuous forest interior core zones, but moreover as regions where generalist species proliferate, especially following disturbances. Biodiversity (of particularly forest specialists) can be negatively impacted as forest area and connectivity of patches decreases, however, increased light penetration tends to initially benefit both early successional generalist and alien species [

66,

67]. In a study investigating forest edges (ecotones) in central Europe, Czaja et al. found especially vertical structural but also species differences between the edge and the interior. Their work also suggests a migration of wind-pollinated species towards the perimeter of the forests which indicates a preference or adaptation for the abiotic microclimates present along forest edges [

22].

Because new perforations within the core area results in fresh edges, depending on the size of the gap, they exhibit similar microclimatic conditions as the forest perimeter. Conditions within perforations can stress newly exposed trees, which leave spruce more vulnerable to bark beetle infestations, which persist in subsequent years [

68]. Moreover, perforations within a forest can increase in size over time; in the protected and largely unmanaged Berchtesgaden National Park, Kruger et al. found that expansion rates of gaps in spruce forests were higher than other forest types [

69]. The sudden increase in light availability can also be favorable even for established interior trees. In a study of mixed mountain forests on the southern border of Bavaria, both coniferous and deciduous species experienced increased growth rates along the fresh edges of forest perforations larger than 80m

2 [

25].

4.3. Functional Metrics – Neighborhood & Connectivity

The number of neighboring patches within a 200m buffer increased with forest size category. Larger patches constitute longer perimeters, and thus a higher proximity to more neighboring patches. However, amongst the smallest patches, the mean number of neighbors was 2.1. With few neighboring patches together with small size of nearby forests (2,468 ha for XS and 12,708 ha for XL patches) this pattern suggests forest patch isolation and reduced habitat area which can influence habitats and animal movement in addition to plant dispersal and reduced biodiversity.

Habitat isolation and patch size are key considerations underpinning the theory of island biogeography, which has often been applied to forested landscapes and may be useful for managing forested landscapes where maintaining biodiversity is a desired outcome [

20]. However, an alternative theory (the habitat amount hypothesis) proposes the conservation of a minimum habitat amount within a landscape, regardless of patch size or isolation, in order to achieve the same biodiversity goals [

13]. In practice, these management considerations depend regionally and on the purpose (and thus species composition) and foresters must weigh the cost of each theoretic approach against the benefit whether it be economic or environmental [

70].

Connectivity of small patches may be enhanced by the presence of hedgerows which typically border agricultural fields, however this approach was not investigated in this study. Hedgerows, analogous to the aforementioned small woody features (smaller than forests by definition), have a heterogenous distribution in Bavaria, and may act as corridors for supporting connectivity of forest patches and thus promote the integrity of ecosystem functioning [

71].

4.4. Fragmentation Intensity – Landscape Patchiness, Aggregation, & Edginess

Taken together, the relative patchiness, aggregation of patches, and the edginess (see Tables 1, 2, & 3) help to understand the level of fragmentation intensity within a landscape. The metrics approximating these concepts were patch density, perimeter length density (including perforations) and shape complexity, and neighborhood (number of neighbors and mean distance to nearest neighbors), respectively. All of these metrics were particularly important in the northern Kronach district. Therefore, it suggests that this district may have a relatively higher intensity of fragmentation compared to other landscape units (districts). Future work could therefore concentrate on this and other similar landscape patterns to uncover drivers of forest loss and the subsequent effects on the forest ecosystem.

4.5. Terrain Distribution – Elevation & Orientation of Forest Patches

In this investigation, we included a brief description of topographical patterns of forested area. Elevation varies across the state with most of the land surface located below 600 m.a.s.l. however, the largest forests are primarily located at elevations above this and are predominantly east-oriented, although eastern slopes cover less total area than other aspects.

Temperature and precipitation vary with elevation and are thus limiting growth factors especially in mountainous terrain, meanwhile sunlight, wind and precipitation are influenced by aspect orientation. Topographically modulated microclimates can have an effect on tree height, aboveground biomass, basal area, and species distribution [

72]. Elevation, aspect, and slope (not investigated in this study) interactively effect tree growth whereby the optimal orientation is determined by elevation [

73]. With respect to disturbances, the magnitude of the forest loss can depend on elevation and slope orientation [

74,

75].

Abiotic conditions are influenced by the orientation of edges which can support temperature-dependent insects like the European spruce bark beetle (

Ips typographus). Therefore, understanding the distribution of forests with respect to fragmentation metrics and terrain can supplement spruce forest management given that bark beetles prefer warmer, drier conditions which can be useful in predicting and managing future outbreaks [

76]. In the BFNP, south-facing edges were twice as likely than north-facing edges to be infested in subsequent years following a nearby infestation [

68].

4.6. Methodology, Further Considerations, & Limitations of the Study

Metrics for this analysis were selected from FRAGSTATS definitions of forest zones, shapes, and distributions. We found the FRAGSTATS methodology well-established, comprehensive, and widely applied to various ecological habitats (Google Scholar returns over 7,000 related publications since 2021). We therefore built our calculation processing chain based on these definitions. Other methods based on definitions of forest connector types, for example bridges, islets, loops and branches, following [

77] (732 citations at the time of writing this manuscript) are equally valid, would produce similar outcomes, and may be considered in future analysis. Furthermore, this analysis presents the current status of forest fragments, a broader analysis of the process of forest fragmentation development will be the subject of a follow-on investigation.

Fragmentation is a process that can alter the structure of a forest over time. The resulting fragmented forest patches may therefore function differently than the original continuous forest. In this analysis we have presented a description of the current status of extant forest patches across the state of Bavaria. Therefore, whether the process of fragmentation is occurring is dependent on further analysis of time-series data. However, a characterization of the distribution and amount of the basic elements within forest patches (perimeter, edge zones, and core area) was not until now available for the entire state of Bavaria or at aggregated administrative levels.

Natural disturbances along edges are a key factor influencing local biodiversity meanwhile highly managed core areas are often species-poor monocultures [

78]. Therefore, management plays a significant role in determining the future of forests, since the determination of which species are propagated after losses is vital for the outcome of services provided by Bavarian forests. In future studies of forest fragmentation in Bavaria, analyses based on forest ownership (state or private) may useful for reaching a target audience of managers, owners, and/or policy-makers. Furthermore, an analysis based on protected status could determine the effectiveness of management schemes in the context of fragmentation patterns. Furthermore, additional connectivity-focused analyses are needed for understanding the distribution of forests in the context of habitats and conservation.

Figure 1.

Scenarios of habitat loss where forest is reduced to 50% and 25%. In each scenario habitat is lost, but only in the ‘bisection’ and ‘fragmentation’ scenarios is the forest both lost and fragmented. Adapted from [

11].

Figure 1.

Scenarios of habitat loss where forest is reduced to 50% and 25%. In each scenario habitat is lost, but only in the ‘bisection’ and ‘fragmentation’ scenarios is the forest both lost and fragmented. Adapted from [

11].

Figure 2.

Fragmentation without forest loss. Forest patches are more numerous in the subsequent frames; however, the overall area of forest within the landscape is unchanged. Adapted from [

16].

Figure 2.

Fragmentation without forest loss. Forest patches are more numerous in the subsequent frames; however, the overall area of forest within the landscape is unchanged. Adapted from [

16].

Figure 3.

A mature forest perimeter where tree architecture has developed according to abiotic to conditions along the forest perimeter (A). Recently disturbed perimeters expose spruce stems to increased sunlight, wind, and temperatures (B, C).

Figure 3.

A mature forest perimeter where tree architecture has developed according to abiotic to conditions along the forest perimeter (A). Recently disturbed perimeters expose spruce stems to increased sunlight, wind, and temperatures (B, C).

Figure 4.

Simplified examples of fragmentation patterns with polygons outlined. Numerous small patches have no distinct core zone (A), variation in patch shapes (simple/geometric, linear, highly complex) (B), perforations within forests result in longer perimeters and exposure to increased sunlight, temperature, and wind (C), large continuous forests have a distinctive buffer region (100m, blue); the ‘edge’, and interior (orange); the ‘core’, which can support greater number of species (D), linear patches can act as corridors to support animal movement (purple), meanwhile decreased connectivity between patches can have species-specific impacts on animal movement and migration (green) (E). Adapted graphics are courtesy of the University of Maryland (Center for Environmental Science, Integration and Application Network) Media Library, CC BY-SA [

29].

Figure 4.

Simplified examples of fragmentation patterns with polygons outlined. Numerous small patches have no distinct core zone (A), variation in patch shapes (simple/geometric, linear, highly complex) (B), perforations within forests result in longer perimeters and exposure to increased sunlight, temperature, and wind (C), large continuous forests have a distinctive buffer region (100m, blue); the ‘edge’, and interior (orange); the ‘core’, which can support greater number of species (D), linear patches can act as corridors to support animal movement (purple), meanwhile decreased connectivity between patches can have species-specific impacts on animal movement and migration (green) (E). Adapted graphics are courtesy of the University of Maryland (Center for Environmental Science, Integration and Application Network) Media Library, CC BY-SA [

29].

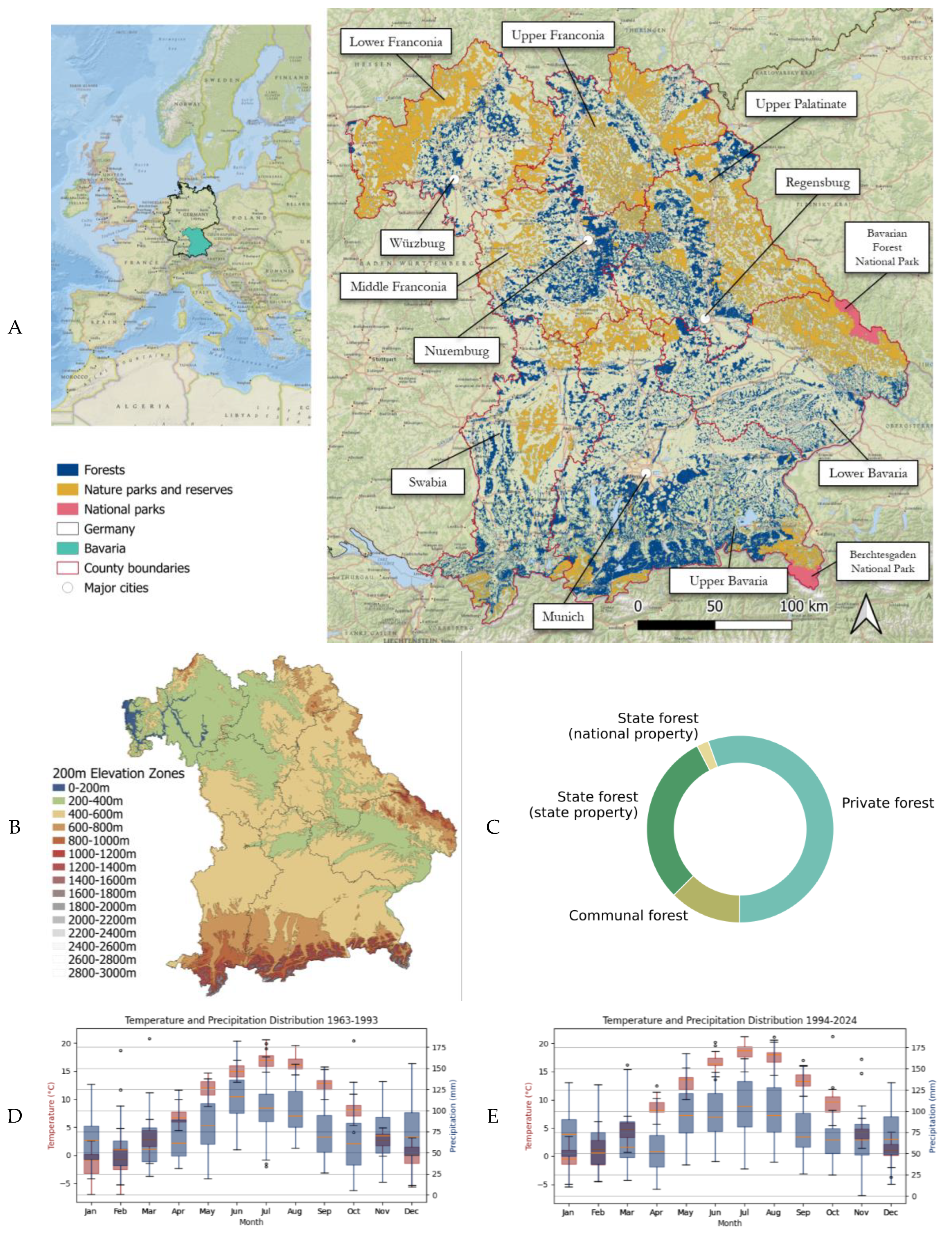

Figure 5.

Overview of Bavaria: Forests and protected areas (A), topography (B), forest ownership (C) and climate (D, E). Adapted from [

34].

Figure 5.

Overview of Bavaria: Forests and protected areas (A), topography (B), forest ownership (C) and climate (D, E). Adapted from [

34].

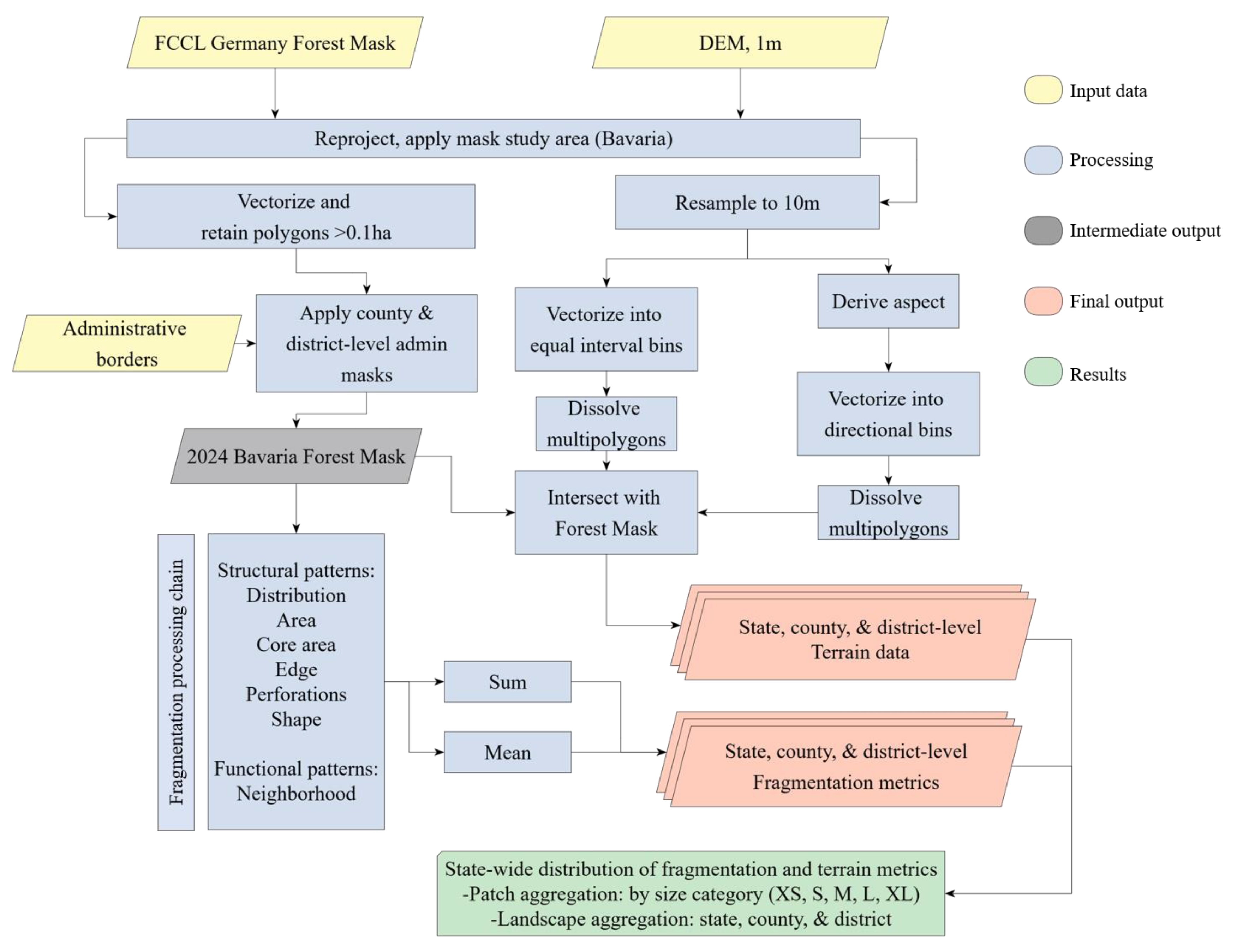

Figure 6.

Summary of workflow.

Figure 6.

Summary of workflow.

Figure 7.

Log-transformed distribution of patch sizes. Small patches are over represented in the dataset.

Figure 7.

Log-transformed distribution of patch sizes. Small patches are over represented in the dataset.

Figure 8.

Overview of forest patch size and distribution (A). Elevations less than 600 m.a.s.l comprise the majority of area in the state, however forest cover is highest at elevations between 800-1400 m.a.s.l. (B). Most hillsides are oriented to the south, however east-facing slopes account for the highest forest cover (C).

Figure 8.

Overview of forest patch size and distribution (A). Elevations less than 600 m.a.s.l comprise the majority of area in the state, however forest cover is highest at elevations between 800-1400 m.a.s.l. (B). Most hillsides are oriented to the south, however east-facing slopes account for the highest forest cover (C).

Figure 9.

Comparison of fragmentation metrics across fragment size categories.

Figure 9.

Comparison of fragmentation metrics across fragment size categories.

Figure 10.

Examples of increasing values of the shape complexity metric: 1.2 (A), 2.3 (B), 4.0 (C), 5.7 (D), 6.3 (E, e), 8.0 (F, f), 15.0 (G, g), 60.0 and (H, h). Values close to 1 indicate basic geometric shapes whereas high values indicate highly complex shapes which include perforations. Dark green represents core forest area while lavender represents the edge area at a depth of 100m.

Figure 10.

Examples of increasing values of the shape complexity metric: 1.2 (A), 2.3 (B), 4.0 (C), 5.7 (D), 6.3 (E, e), 8.0 (F, f), 15.0 (G, g), 60.0 and (H, h). Values close to 1 indicate basic geometric shapes whereas high values indicate highly complex shapes which include perforations. Dark green represents core forest area while lavender represents the edge area at a depth of 100m.

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of selected fragmentation densities.

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of selected fragmentation densities.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of selected fragmentation densities.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of selected fragmentation densities.

Table 1.

Fragmentation intensity based on forest amount relative to the number of fragments.

Table 1.

Fragmentation intensity based on forest amount relative to the number of fragments.

| Forest area |

Number of fragments |

Interpretation |

Fragmentation |

| High |

Low |

Fragmentation intensity is low, forests likely have larger core areas |

Low |

| High |

High |

Fragmentation per se is high however, forest amount is preserved |

Moderate to high |

| Low |

Low |

Forest is aggregated but scarce or potentially isolated |

Low to moderate |

| Low |

High |

Intense fragmentation, forest areas are scarce and disaggregated |

High |

Table 2.

The number of neighbors and the distance between patches can conceptualize how isolated or aggregated forest patches are within a landscape.

Table 2.

The number of neighbors and the distance between patches can conceptualize how isolated or aggregated forest patches are within a landscape.

| Number of neighbors |

Distance to neighbors |

Interpretation |

Aggregation |

| High |

Low |

Fragmentation intensity is high but patches are less isolated |

High |

| High |

High |

Fragmentation is high, and patches are more isolated or dispersed |

Low to moderate |

| Low |

Low |

Fragmentation is low and patches are tightly aggregated |

Moderate to high |

| Low |

High |

Patches are few and quite isolated |

Low |

Table 4.

Datasets used.

| Dataset |

Description |

Type |

Spatial resolution |

Author |

Pub. Date |

Access |

| Forest Canopy Cover Loss (FCCL) Forest Mask |

Detection based on Disturbance Index (DI) |

Raster |

10m |

Thonfeld et al. |

2025 |

DLR geoservice, https://doi.org/10.15489/ef9wwc5sff75 |

| Digital elevation model (DEM) |

High-resolution DEM based on ALS data |

Raster |

1m |

Bavarian Surveying Authority |

|

Bavarian Geoportal, www.geoportal.bayern.de |

Table 5.

Description of fragmentation metrics.

Table 5.

Description of fragmentation metrics.

| Landscape pattern |

Category |

Metric (aggregation) |

Unit |

Description or formula |

Interpretation |

| Structural |

Distribution |

Number of patches (sum) |

n/a |

The total number of patches within a given landscape or administrative unit |

High values suggest discontinuous forest within a given landscape. |

| Structural |

Area |

Area (sum, mean) |

Hectares |

Area of forest patch(es) |

Higher values suggest more continuous forest when number of patches is low. |

| Structural |

Core Area |

Core area (sum, mean) |

Hectares |

Core forest area considering an edge depth of 100m |

Value indicates size of core forest. |

| |

|

Core area % (mean) |

Hectares |

Percent of core area, considering an edge depth of 100m |

High values suggest a higher ratio of core to edge area. |

| Structural |

Edge |

Perimeter (sum, mean) |

Meters |

Patch perimeter length |

High values suggest greater exposure to edge effects. |

| |

|

Edge area (sum, mean) |

Hectares |

Edge depth (100m) is a measure of the region of forest from the perimeter edge toward the core area |

Trees inside edges experience higher sunlight, wind, temperatures and drier soil conditions. |

| |

|

Edge area % (mean) |

n/a |

The ratio of edge area (100m edge depth) to overall area |

Higher values may equate to lower overall core area. |

| Structural |

Perforations |

Number of perforations (sum, mean) |

n/a |

Number of perforations in a forest patch or landscape |

Highly complex patch shapes and increased exposure to edge effects. |

| |

|

Perforated area (sum, mean) |

Hectares |

Area of perforations in a forest or landscape |

High values can suggest increases in shape complexity. |

| Structural |

Shape |

Paratio (mean) |

n/a |

|

Higher values equate to higher shape complexity (varies with size of patch). |

| |

|

Shape index (mean) |

n/a |

|

Higher values equate to higher shape complexity (employs a constant to correct for size). |

| Functional |

Neighbor-hood |

Number of neighbors (sum, mean) |

n/a |

Counts neighboring forests based on edge-to-edge distance within 200m buffer of each patch. |

Increases over time can indicate higher fragmentation intensity. |

| |

|

Area of neighbors (sum, mean) |

Hectares |

Area of neighboring patches within 200m buffer. |

High values indicate large nearby forests. |