Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Treatments and Experimental Design

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Growth Rate

2.3.2. Yield and Yield Components

2.3.3. Grain Size

2.3.4. Grain Protein Content

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

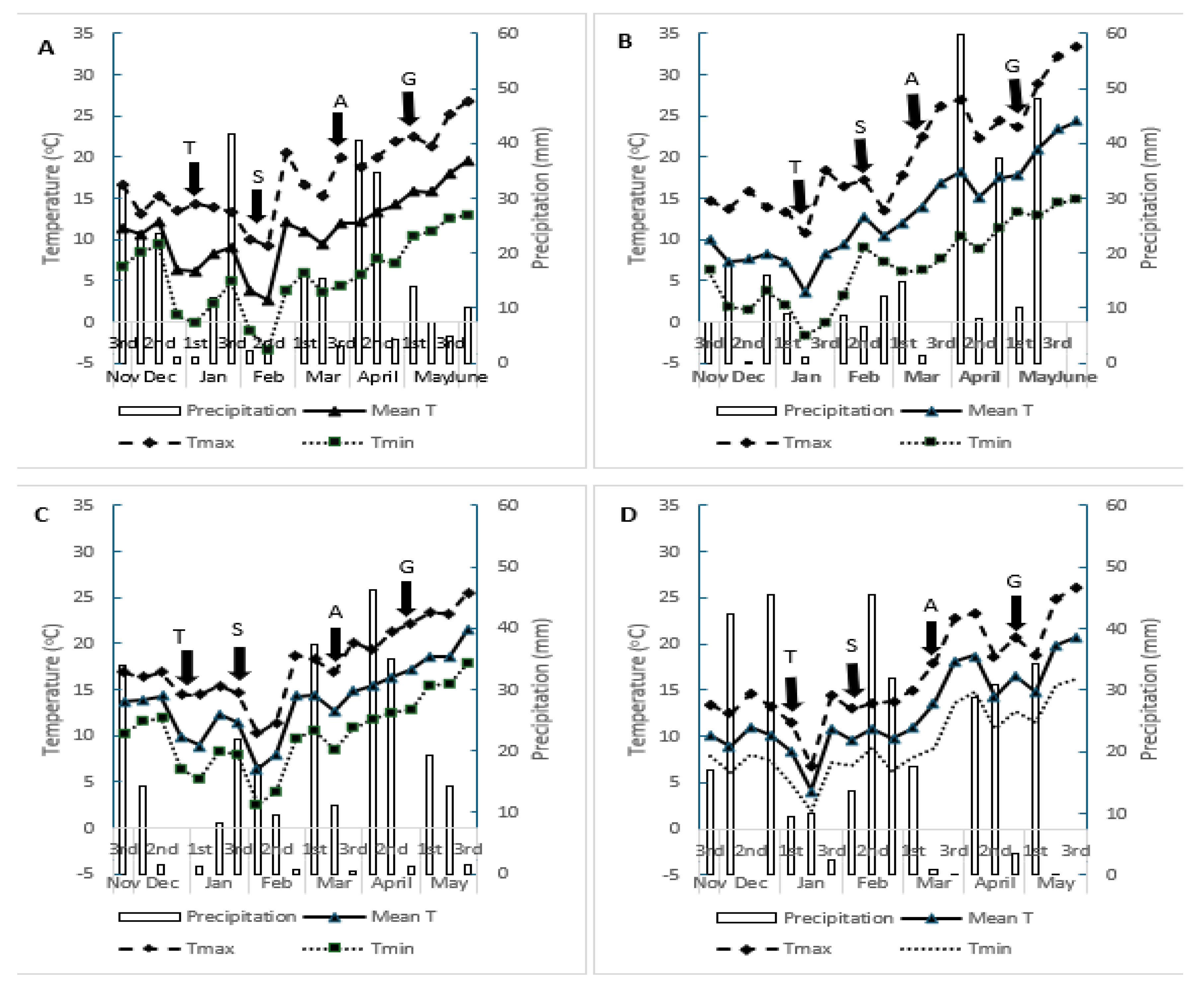

3.1. Meteorological Data

3.2. Impact of Treatments on Quantitative Traits

3.2.1. Effects of Biostimulant and Fertilization at Early Stages on Quantitative Traits

3.2.2. Effects of Biostimulant and Fertilization at Mid-Stages on Quantitative Traits

3.3. Impact of Treatments on Qualitative Traits

Effects of Biostimulant and Fertilization at Mid-Stages on Qualitative Traits

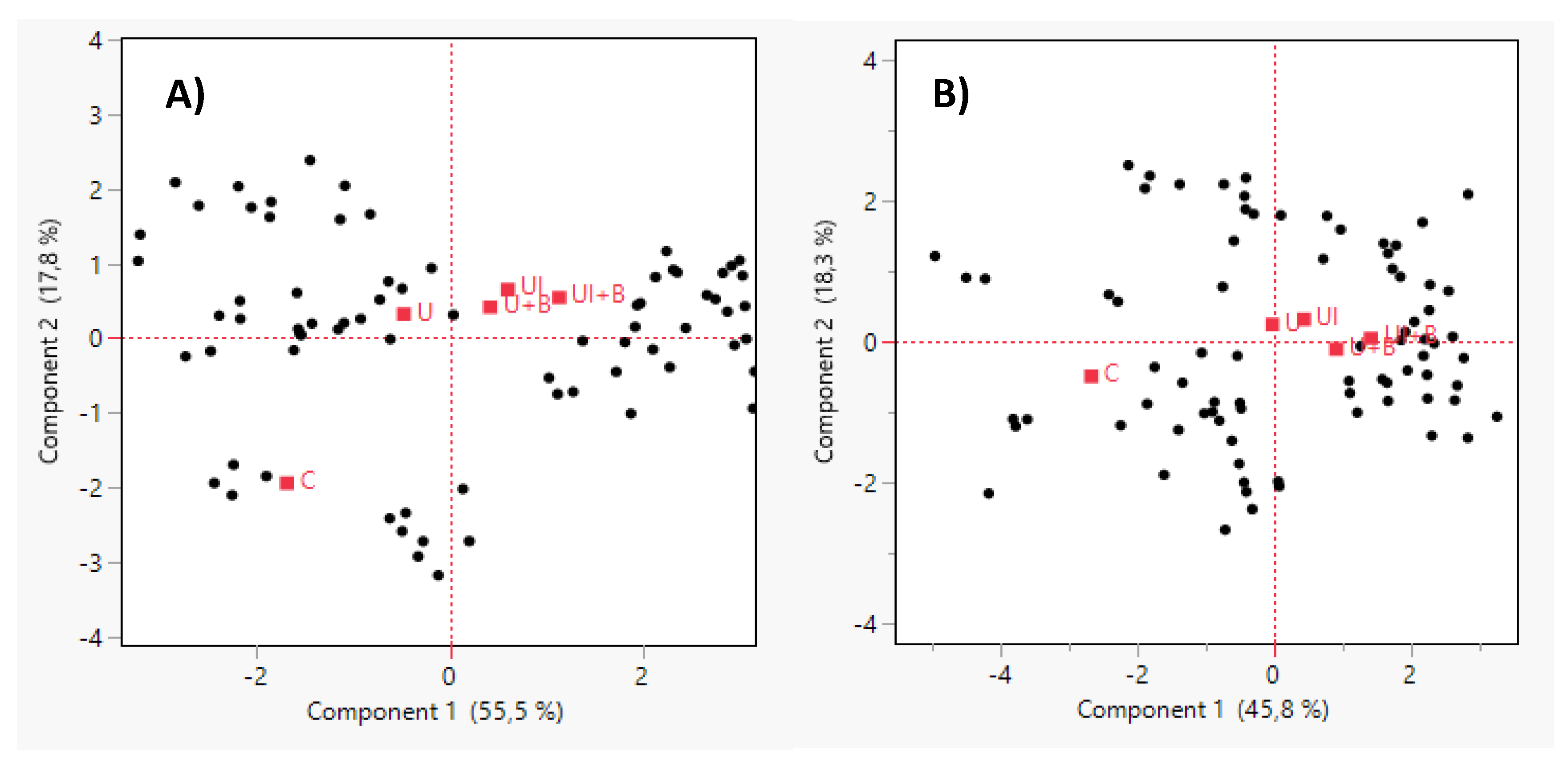

3.4. Principal Component Analysis

3.4.1. Impact of Environmental and Treatment Factors at Early Stages

3.4.2. Impact of Environmental and Treatment Factors at Mid-Stages

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Environmental and Treatment Factors at Early Stages

4.2. Impact of Environmental and Treatment Factors at Mid-Stages

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GPC | Grain Protein Content |

| UI | Urease Inhibitor |

| UI+B | Urea with Urease Inhibitor and Biostimulan |

| U | Urea |

| U+B | Urea with Biostimulant |

| ANE | Ascophyllum nodosum Extract |

| TGW | Thousand Grain Weight |

| RCB | Randomized Complete Block design |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| LSD | Least Significant Difference |

| E1, E2, E3, E4 | Experimental Environments (different locations/seasons in Thessaly) |

References

- El-Hashash, E.F.; El-Absy, K.M. Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) breeding. In Adv. Plant Breed. Strateg.: Cereals, Vol. 5; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Purewal, S.S.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Punia Bangar, S. Unraveling the hidden potential of barley (Hordeum vulgare): An important review. Plants 2024, 13, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G.P.; Bettenhausen, H.M. Variation in quality of grains used in malting and brewing. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1172028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahamidis, P.; Stefopoulou, A.; Kotoulas, V.; Lyra, D.; Dercas, N.; Economou, G. Yield, grain size, protein content and water use efficiency of null-LOX malt barley in a semiarid Mediterranean agroecosystem. Field Crops Res. 2017, 206, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahamidis, P.; Stefopoulou, A.; Kotoulas, V.; Voloudakis, D.; Dercas, N.; Economou, G. A further insight into the environmental factors determining potential grain size in malt barley under Mediterranean conditions. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 122, 126184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Schwarz, P.B.; Barr, J.M.; Horsley, R.D. Factors predicting malt extract within a single barley cultivar. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, E.; Di Mola, I.; Ottaiano, L.; Nocerino, S.; Sifola, M.I.; El-Nakhel, C.; Rouphael, E.; Mori, M. Can seaweed extract improve yield and quality of brewing barley subjected to different levels of nitrogen fertilization? Agronomy 2021, 11, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asres, T.; Tadesse, D.; Wossen, T.; Sintayehu, A. Performance evaluation of malt barley: From malting quality and breeding perspective. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 21, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillouin, D.; Leclere, M.; Barbu, C.M.; Benezit, M.; Trépos, R.; Gauffreteau, A.; Jeuffroy, M.H. Azodyn-Barley, a winter-barley crop model for predicting and ranking genotypic yield, grain protein and grain size in contrasting pedoclimatic conditions. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 262, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahamidis, P.; Stefopoulou, A.; Kotoulas, V.; Bresta, P.; Nikolopoulos, D.; Karabourniotis, G.; Mantonakis, G.; Vlachos, C.; Dercas, N.; Economou, G. Grain size variation in two-rowed malt barley under Mediterranean conditions: Phenotypic plasticity and relevant trade-offs. Field Crops Res. 2022, 279, 108454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin Tan, W.; Li, M.; Devkota, L.; Attenborough, E.; Dhital, S. Mashing performance as a function of malt particle size in beer production. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 5372–5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltonen-Sainio, P.; Jauhiainen, L.; Sadras, V.O. Phenotypic plasticity of yield and agronomic traits in cereals and rapeseed at high latitudes. Field Crops Res. 2011, 124, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Mahadevan, M.; Zwer, P.K. Oat phenotypes for drought adaptation and yield potential. Field Crops Res. 2017, 212, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bergen, E.; Atencio, G.; Saastamoinen, M.; Beldade, P. Thermal plasticity in protective wing pigmentation is modulated by genotype and food availability in an insect model of seasonal polyphenism. Funct. Ecol. 2024, 38, 1765–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmec, A.; de Leon, N.; Schnable, P.S. Harnessing phenotypic plasticity to improve maize yields. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Tan, X.; Zou, W.; Hu, Z.; Fox, G.P.; Gidley, M.J.; Gilbert, R.G. Relationships between protein content, starch molecular structure and grain size in barley. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 155, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, M.; Lepiarczyk, A.; Filipek-Mazur, B.; Lisowska, A. Efficiency of nitrogen fertilization of winter wheat depending on sulfur fertilization. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Yildirim, S.; Andrikopoulos, B.; Wille, U.; Roessner, U. Deciphering the interactions in the root–soil nexus caused by urease and nitrification inhibitors: A review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahamidis, P.; Stefopoulou, A.; Kotoulas, V. Optimizing sustainability in malting barley: A practical approach to nitrogen management for enhanced environmental, agronomic, and economic benefits. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bordoloi, N. Role of slow-release fertilizers and nitrification inhibitors in greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N₂O) emission reduction from rice–wheat agroecosystem. In Agric. Greenh. Gas Emiss.: Probl. Solut.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.U.; Aamer, M.; Mahmood, A.; Awan, M.I.; Barbanti, L.; Seleiman, M.F.; Bakhsh, G.; Alkharabsheh, H.M.; Babur, E.; Shao, J.; Rasheed, A.; Huang, G. Management strategies to mitigate N₂O emissions in agriculture. Life 2022, 12, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, N.; Belec, C. Adapting nitrogen fertilization to unpredictable seasonal conditions with the least impact on the environment. HortTechnology 2006, 16, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Xu, X.; Zhou, W.; Smith, W.; He, W.; Grant, B.; Ding, W.; Qiu, S.; Zhao, S. Ensuring future agricultural sustainability in China utilizing an observationally validated nutrient recommendation approach. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 132, 126409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolajsen, M.T.; Pacholski, A.S.; Sommer, S.G. Urea ammonium nitrate solution treated with inhibitor technology: Effects on ammonia emission reduction, wheat yield, and inorganic N in soil. Agronomy 2020, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende-Montalbán, R.; Martín-Lammerding, D.; Delgado, M.D.M.; Porcel, M.A.; Gabriel, J.L. Urease inhibitors effects on the nitrogen use efficiency in a maize–wheat rotation with or without water deficit. Agriculture 2021, 11, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalos, D.; Jeffery, S.; Sanz-Cobena, A.; Guardia, G.; Vallejo, A. Meta-analysis of the effect of urease and nitrification inhibitors on crop productivity and nitrogen use efficiency. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 189, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.O.; Fugice, J.; Singh, U.; Lewis, T.D. Development of fertilizers for enhanced nitrogen use efficiency – Trends and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 139113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Yin, X.; Savoy, H.J.; McClure, A.; Essington, M.E. Ammonia volatilization loss and corn nitrogen nutrition and productivity with efficiency enhanced UAN and urea under no-tillage. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodley, A.L.; Drury, C.F.; Yang, X.Y.; Phillips, L.A.; Reynolds, D.W.; Calder, W.; Oloya, T.O. Ammonia volatilization, nitrous oxide emissions, and corn yields as influenced by nitrogen placement and enhanced efficiency fertilizers. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbessa, Y.; Juskiw, P. Nitrogen fertilizer rate and cultivar interaction effects on nitrogen recovery, utilization efficiency, and agronomic performance of spring barley. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 531647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Steep, cheap and deep: An ideotype to optimize water and N acquisition by maize root systems. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.; Foulkes, M.J.; Slafer, G.A.; Berry, P.; Parry, M.A.; Snape, J.W.; Angus, W.J. Raising yield potential in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1899–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khush, G.S. Green revolution: The way forward. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001, 2, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, R.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Cho, Y.B.; Ermakova, M.; Harbinson, J.; Lawson, T.; Zhu, X.G. Perspectives on improving photosynthesis to increase crop yield. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3944–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, A.; Santana, A.S.; Uberti, A.; Dias, F.D.S.; Dos Reis, H.M.; Destro, V.; DeLima, R.O. Genetic diversity, relationships among traits and selection of tropical maize inbred lines for low-P tolerance based on root and shoot traits at seedling stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1429901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J.; Xu, G. Plant nitrogen uptake and assimilation: Regulation of cellular pH homeostasis. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 4380–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, N.; Sethi, M.; Kumar, A.; Dang, D.; Singh, J.; Chhuneja, P. Biochemical and genetic approaches improving nitrogen use efficiency in cereal crops: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 657629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masclaux-Daubresse, C.; Daniel-Vedele, F.; Dechorgnat, J.; Chardon, F.; Gaufichon, L.; Suzuki, A. Nitrogen uptake, assimilation and remobilization in plants: Challenges for sustainable and productive agriculture. Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perchlik, M.; Tegeder, M. Improving plant nitrogen use efficiency through alteration of amino acid transport processes. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.E.; Chen, H.Y.; Tseng, C.S.; Tsay, Y.F. Improving nitrogen use efficiency by manipulating nitrate remobilization in plants. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, O.V.; Ghai, S.; Paul, D.; Jain, R.K. Genetically modified crops: success, safety assessment, and public concern. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 71, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Hu, B.; Yuan, D.; Liu, Y.; Che, R.; Hu, Y.; Chu, C. Expression of the nitrate transporter gene OsNRT1.1A/OsNPF6.3 confers high yield and early maturation in rice. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Sario, L.; Boeri, P.; Matus, J.T.; Pizzio, G.A. Plant biostimulants to enhance abiotic stress resilience in crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosten, M.J.; Pepe, O.; De Pascale, S.; Silletti, S.; Maggio, A. The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Sehrawat, K.D.; Phogat, D.; Sehrawat, A.R.; Chaudhary, R.; Sushkova, S.N.; Voloshina, M.S.; Rajput, V.D.; Shmaraeva, A.N.; Marc, R.A.; Shende, S.S. Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jolis, a pivotal biostimulant toward sustainable agriculture: A comprehensive review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: Implications towards sustainable crop production. Plants 2021, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, O.; Fort, A.; Quille, P.; McKeown, P.C.; Spillane, C.; O’Connell, S. Comparative transcriptome analysis of two Ascophyllum nodosum extract biostimulants: Same seaweed but different. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 2980–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craigie, J.S. Seaweed extract stimuli in plant science and agriculture. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battacharyya, D.; Babgohari, M.Z.; Rathor, P.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, I.; Chojnacka, K. Algal extracts: Technology and advances. Eng. Life Sci. 2014, 14, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babazadeh, B.A.; Sadeghzadeh, N.; Hajiboland, R. The impact of algal extract as a biostimulant on cold stress tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 2919–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Abdi, G.; Saleem, M.H.; Ali, B.; Ullah, S.; Shah, W.; Mumtaz, S.; Yasin, G.; Muresan, C.C.; Marc, R.A. Plants’ physio-biochemical and phyto-hormonal responses to alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress: A comprehensive review. Plants 2022, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, F.; Olivos-Hernández, K.; Stange, C.; Handford, M. Abiotic stress in crop species: Improving tolerance by applying plant metabolites. Plants 2021, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koprna, R.; Humplík, J.F.; Špíšek, Z.; Bryksová, M.; Zatloukal, M.; Mik, V.; Novák, O.; Nisler, J.; Doležal, K. Improvement of tillering and grain yield by application of cytokinin derivatives in wheat and barley. Agronomy 2020, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadoks, J.C.; Chang, T.T.; Konzak, C.F. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Res. 1974, 14, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Slafer, G.A. Environmental modulation of yield components in cereals: Heritabilities reveal a hierarchy of phenotypic plasticities. Field Crops Res. 2012, 127, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Tang, Y.; Li, C.; Wu, C. Characterization of the rate and duration of grain filling in wheat in southwestern China. Plant Prod. Sci. 2018, 21, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.A.; Serrago, R.A.; Dreccer, M.F.; Miralles, D.J. Post-anthesis warm nights reduce grain weight in field-grown wheat and barley. Field Crops Res. 2016, 195, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Expansive growth of plant cell walls. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2000, 38, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, K.; Jauhiainen, L.; Rajala, A.A.; Jalli, M.; Kujala, M.; Laine, A. Different responses to weather events may change the cultivation balance of spring barley and oats in the future. Field Crops Res. 2020, 259, 107956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseva, J.; Hakala, K.; Högnäsbacka, M.; Jauhiainen, L.; Himanen, S.J.; Rötter, R.P.; Balek, J.; Trnka, M.; Kahiluoto, H. Assessing climate resilience of barley cultivars in northern conditions during 1980–2020. Field Crops Res. 2023, 293, 108856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, F.R.; Frenck, G.; van der Linden, L.; Mikkelsen, T.N.; Jørgensen, R.B. Can barley (Hordeum vulgare L. sl) adapt to fast climate changes? A controlled selection experiment. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quille, P.; Claffey, A.; Feeney, E.; Kacprzyk, J.; Ng, C.K.Y.; O’Connell, S. The effect of an engineered biostimulant derived from Ascophyllum nodosum on grass yield under a reduced nitrogen regime in an agronomic setting. Agronomy 2022, 12, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, O.; Łangowski, Ł.; Feeney, E.; Quille, P.; O’Connell, S. Reducing nitrogen input in barley crops while maintaining yields using an engineered biostimulant derived from Ascophyllum nodosum to enhance nitrogen use efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 664682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatiadis, S.; Evangelou, L.; Yvin, J.C.; Tsadilas, C.; Mina, J.M.G.; Cruz, F. Responses of winter wheat to Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol. extract application under the effect of N fertilization and water supply. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, E.A.; Ahmed, N.; Durieu, C.; Grieu, P.; Lamaze, T. Marine and fungal biostimulants improve grain yield, nitrogen absorption and allocation in durum wheat plants. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 158, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łangowski, Ł.; Goñi, O.; Ikuyinminu, E.; Feeney, E.; O'Connell, S. Investigation of the direct effect of a precision Ascophyllum nodosum biostimulant on nitrogen use efficiency in wheat seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 179, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quille, P.; Kacprzyk, J.; O’Connell, S.; Ng, C.K. Reducing fertiliser inputs: Plant biostimulants as an emerging strategy to improve nutrient use efficiency. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Niu, G.; Masabni, J.; Ferrante, A.; Cocetta, G. Integrated nutrient management of fruits, vegetables, and crops through the use of biostimulants, soilless cultivation, and traditional and modern approaches—A mini review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, V.; Coquerel, R.; Géliot, P.; Avice, J.C. VNT4, a derived formulation of Glutacetine® biostimulant, improved yield and N-related traits of bread wheat when mixed with urea–ammonium–nitrate solution. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Caparros, P.; Ciriello, M.; Rouphael, Y.; Giordano, M. The role of organic extracts and inorganic compounds as alleviators of drought stress in plants. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, A.; Wang, Z.; Roelcke, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, X. Effect of a new urease inhibitor on ammonia volatilization and nitrogen utilization in wheat in north and northwest China. Field Crops Res. 2015, 175, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swify, S.; Mažeika, R.; Baltrusaitis, J.; Drapanauskaitė, D.; Barčauskaitė, K. Modified urea fertilizers and their effects on improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). Sustainability 2023, 16, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, D.J.; Forrestal, P.J.; Wall, D.; Lanigan, G.J.; Sanz-Gomez, J.; Richards, K.G. Nitrogen fertilisers with urease inhibitors reduce nitrous oxide and ammonia losses, while retaining yield in temperate grassland. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrestal, P.J.; Wall, D.; Carolan, R.; Harty, M.A.; Roche, L.; Krol, D.; Watson, C.J.; Lanigan, G.; Richards, K.G. Effects of urease and nitrification inhibitors on yields and emissions in grassland and spring barley. Int. Fertil. Soc. 2016, September. [Google Scholar]

- Harty, M.A.; Forrestal, P.J.; Carolan, R.; Watson, C.J.; Hennessy, D.; Lanigan, G.J.; Wall, D.P.; Richards, K.G. Temperate grassland yields and nitrogen uptake are influenced by fertilizer nitrogen source. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Ding, K.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Global meta-analysis of individual and combined nitrogen inhibitors: Enhancing plant productivity and reducing environmental losses. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2024, 30, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brace, B.E.; Schlossberg, M.J. Field evaluation of urea fertilizers enhanced by biological inhibitors or dual coating. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G.P.; Bettenhausen, H.M. Variation in quality of grains used in malting and brewing. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1172028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.E.; Paynter, B.H.; Izydorczyk, M.S.; Li, C. The impact of terroir on barley and malt quality–A critical review. J. Inst. Brew. 2023, 129, 211–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hřivna, L.; Maco, R.; Dufková, R.; Kouřilová, V.; Burešová, I.; Gregor, T. Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare. Open Agric. 2024, 9, 20220270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.S.; Mantin, E.G.; Adil, M.; Bajpai, S.; Critchley, A.T.; Prithiviraj, B. Ascophyllum nodosum-based biostimulants: Sustainable applications in agriculture for the stimulation of plant growth, stress tolerance, and disease management. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 462648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chloupek, O.; Dostál, V.; Středa, T.; Psota, V.; Dvořáčková, O.J.P.B. Drought tolerance of barley varieties in relation to their root system size. Plant Breed. 2010, 129, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettl, B.; DeSutter, T.; Bu, H.; Wick, A.; Franzen, D. Managing nitrogen to promote quality and profitability of North Dakota two-row malting barley. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, R.; Nicolas, M.E. Effects of short periods of drought and high temperature on grain growth and starch accumulation of two malting barley cultivars. Funct. Plant Biol. 1996, 23, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakita, S.; Torbica, A.; Pezo, L.; Nikolić, I. Effect of climatic conditions on wheat starch granule size distribution, gelatinization and flour pasting properties. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabwalo, D.N.; Berzonsky, W.A.; Brabec, D.; Pearson, T.; Glover, K.D.; Kleinjan, J.L. Impact of grain morphology and the genotype by environment interactions on test weight of spring and winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Euphytica 2018, 214, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craine, E.B.; Choi, H.; Schroeder, K.L.; Brueggeman, R.; Esser, A.; Murphy, K.M. Spring barley malt quality in eastern Washington and northern Idaho. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 1148–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatiadis, S.; Evangelou, E.; Jamois, F.; Yvin, J.C. Targeting Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol. extract application at five growth stages of winter wheat. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nephali, L.; Piater, L.A.; Dubery, I.A.; Patterson, V.; Huyser, J.; Burgess, K.; Tugizimana, F. Biostimulants for plant growth and mitigation of abiotic stresses: A metabolomics perspective. Metabolites 2020, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Panda, R.K.; Chakraborty, A.; Halder, D. Enhancing grain yield, biomass and nitrogen use efficiency of maize by varying sowing dates and nitrogen rate under rainfed and irrigated conditions. Field Crops Res. 2018, 221, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ji, D.; Peng, S.; Loladze, I.; Harrison, M.T.; Davies, W.J.; Smith, P.; Xia, L.; Wang, B.; Liu, K.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, W.; Ouyang, L.; Liu, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, F. Eco-physiology and environmental impacts of newly developed rice genotypes for improved yield and nitrogen use efficiency coordinately. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 896, 165294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Peng, J.; Dong, W.; Wei, Z.; Zafar, S.U.; Jin, T.; Liu, E. Optimizing irrigation and nitrogen fertilizer regimes to increase the yield and nitrogen utilization of Tibetan barley in Tibet. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djanaguiraman, M.; Narayanan, S.; Erdayani, E.; Prasad, P.V. Effects of high temperature stress during anthesis and grain filling periods on photosynthesis, lipids and grain yield in wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, M.; Slafer, G.A.; Savin, R. Yield and grain weight responses to post-anthesis increases in maximum temperature under field grown wheat as modified by nitrogen supply. Field Crops Res. 2018, 221, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugarte, C.; Calderini, D.F.; Slafer, G.A. Grain weight and grain number responsiveness to pre-anthesis temperature in wheat, barley and triticale. Field Crops Res. 2007, 100, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.N.; Tanveer, M.; Rehman, A.U.; Anjum, S.A.; Iqbal, J.; Ahmad, R. Lodging stress in cereals—Effects and management: An overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 5222–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya-Sereno, M.D.; Pancorbo, J.L.; Alonso-Ayuso, M.; Gabriel, J.L.; Quemada, M. Winter wheat genotype ability to recover nitrogen supply by precedent crops under combined nitrogen and water scenarios. Field Crops Res. 2023, 290, 108758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, I.; Kiær, L.P.; Bergkvist, G.; Weih, M.; Ninkovic, V. Plasticity of barley in response to plant neighbors in cultivar mixtures. Plant Soil 2020, 447, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Á.; Gilliland, T.J.; Delaby, L.; Patton, D.; Creighton, P.; Forrestal, P.J.; McCarthy, B. Can a urease inhibitor improve the efficacy of nitrogen use under perennial ryegrass temperate grazing conditions? J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 161, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, D.J.; Abeledo, L.G.; Alvarez Prado, S.; Chenu, K.; Serrago, R.A.; Savin, R. Barley. In Crop Physiology: Case Histories for Major Crops, 2nd ed.; Sadras, V.O., Calderini, D.F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 164–195. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Hamani, A.K.M.; Si, Z.; Abubakar, S.A.; Liang, Y.; Liu, K.; Gao, Y. Effects of timing in irrigation and fertilization on soil NO₃⁻-N distribution, grain yield and water–nitrogen use efficiency of drip-fertigated winter wheat in the North China Plain. Water 2022, 14, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić, M.M.; Tagarakis, A.C.; Ljubičić, N.; Blagojević, D.; Radulović, M.; Ivošević, B.; Rakić, D. The effect of N fertilizer application timing on wheat yield on chernozem soil. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Köbke, S.; Dittert, K. Use of urease and nitrification inhibitors to reduce gaseous nitrogen emissions from fertilizers containing ammonium nitrate and urea. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczyk, M.; Siczek, A.; Schimmelpfennig, L. Improving the efficiency of urea-based fertilization leading to reduction in ammonia emission. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 145483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrago, R.A.; García, G.A.; Savin, R.; Miralles, D.J.; Slafer, G.A. Determinants of grain number responding to environmental and genetic factors in two- and six-rowed barley types. Field Crops Res. 2023, 302, 109073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, N.A.R.; Lateef, D.D.; Mustafa, K.M.; Rasul, K.S. Under natural field conditions, exogenous application of moringa organ water extract enhanced the growth- and yield-related traits of barley accessions. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, M.S.; Edney, M. Barley: Grain-quality characteristics and management of quality requirements. In Cereal Grains, 2nd ed.; Wrigley, C., Batey, I., Miskelly, D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 195–234. [Google Scholar]

- Akhter, Z.; Bi, Z.; Ali, K.; Sun, C.; Fiaz, S.; Haider, F.U.; Bai, J. In response to abiotic stress, DNA methylation confers epigenetic changes in plants. Plants 2021, 10, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephatsi, M.; Nephali, L.; Meyer, V.; Piater, L.A.; Buthelezi, N.; Dubery, I.A.; Opperman, H.; Brand, M.; Huyser, J.; Tugizimana, F. Molecular mechanisms associated with microbial biostimulant-mediated growth enhancement, priming and drought stress tolerance in maize plants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.B.; Angessa, T.T.; Westcott, S.; McFawn, L.A.; Shirdelmoghanloo, H.; Han, Y.; Li, C. Evaluation of the impact of heat stress at flowering on spikelet fertility and grain quality in barley. Agric. Commun. 2024, 2, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirdelmoghanloo, H.; Chen, K.; Paynter, B.H.; Angessa, T.T.; Westcott, S.; Khan, H.A.; Hill, C.B.; Li, C. Grain-filling rate improves physical grain quality in barley under heat stress conditions during the grain-filling period. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 858652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Biostimulants in agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Properties | ||||||||||||

| Soil Texture |

Organic matter (%) |

pH | Total Nitrogen (%) |

Phosphorus (ppm) | Potassium (ppm) | |||||||

| E1 | Clay | 2.02 | 7.05 | 0.147 | 20.12 | 266 | ||||||

| E2 | Clay | 2.34 | 7.10 | 0.161 | 23.66 | 224 | ||||||

| E3 | Clay loam | 1.95 | 7.20 | 0.133 | 19.57 | 172 | ||||||

| E4 | Clay loam | 1.86 | 7.22 | 0.129 | 16.53 | 281 | ||||||

| Quantitative Traits | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboveground Biomass | Yield | HI | Spikelets*m-2 | TGW | Grains* Spike-1 | ||

| Environment (E) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | |

| Genotype (G) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Treatment (T) | *** | *** | * | *** | *** | ** | |

| E*G | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | |

| E*T | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | *** | |

| G*T | ns | ** | ns | ** | ** | *** | |

| E*G*T | ** | *** | ns | * | ** | *** | |

| Aboveground Biomass | Yield | HI | ||||||||||||||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | |||||

| G45 | U | 12.85ab | 6.46ad | 11.25abc | 6.72bc | 6.68cd | 3.19ac | 6.13b | 3.28ac | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.55cde | 0.49 | |||

| U+B | 15c | 8.24ab | 11.9ab | 8abc | 6.74cd | 3.5ab | 6.99c | 3.49ac | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.58ce | 0.44 | ||||

| UI | 12.25b | 8.45abc | 11.3abc | 8.62ab | 7.18c | 3.68ab | 7.07c | 3.52ac | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.63c | 0.40 | ||||

| UI+B | 13.85abc | 9.45bc | 12.05ab | 9.46ad | 7.62c | 4.02abd | 7.36c | 4.32ab | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.62c | 0.46 | ||||

| Control | 9d | 5.51d | 9.65c | 5.35c | 4.62ae | 2.51c | 4.91d | 2.42c | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.51ade | 0.49 | ||||

| G20 | U | 13 ab | 7.25abd | 12.4ab | 12.16dei | 5.26ab | 3.44abc | 5.43ad | 4.63b | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.44ab | 0.38 | |||

| U+B | 14.25ac | 10.63c | 12.65a | 14.17e | 5.43ab | 4.24bd | 5.73ab | 4.65b | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.45ab | 0.32 | ||||

| UI | 13.1abc | 8.46abc | 12.15ab | 10.08ad | 5.33ab | 3.35abc | 5.68ab | 3.65a | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.44ab | 0.36 | ||||

| UI+B | 14.2ac | 9.24bc | 12.35ab | 13.54e | 5.73bd | 4.94d | 5.88ab | 4.69b | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.49ad | 0.30 | ||||

| Control | 9.3d | 5.6d | 10.45bc | 9.03ab | 3.95e | 2.57c | 3.86e | 3.49ac | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.37b | 0.39 | ||||

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||||||

| Genotype (G) | * | *** | ** | *** | *** | * | *** | ** | *** | ns | *** | * | ||||

| Treatment (T) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | *** | ns | ||||

| G*T | * | * | * | *** | * | ** | * | *** | ns | ns | * | ns | ||||

| Spikelets*m-2 | TGW | Grains*Spike-1 | ||||||||||||||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | |||||

| G45 | U | 745c | 423abc | 657b | 448bc | 38.80c | 35.60d | 38.59ade | 35.4ac | 29.5ab | 27.8a | 27.5ae | 28.3abc | |||

| U+B | 822cd | 476abd | 736bc | 546abc | 42.48bd | 39.45a | 39.97abd | 35.7ac | 28a | 27a | 28a | 28.8ab | ||||

| UI | 834cd | 478abd | 691bc | 583ab | 44.17ab | 40.52a | 40.22abd | 36.92a | 29.3ab | 27.7a | 28.3ac | 28.8ab | ||||

| UI+B | 880d | 535d | 768c | 615a | 46.22a | 42.40ab | 41.64abc | 38.26ad | 28a | 28ac | 31bc | 28.5ab | ||||

| Control | 597a | 371ace | 543a | 409c | 37.77c | 34.65d | 35.64e | 32.73c | 24.3c | 26.2a | 25de | 26c | ||||

| G20 | U | 582ab | 368ce | 531a | 552ab | 44.21ab | 43.92bc | 40.99abc | 40.75bd | 30.2ab | 28.2ac | 30.3abc | 28abc | |||

| U+B | 623a | 456abcd | 567a | 584ab | 44.66ab | 44.40bc | 43.11bc | 42.85b | 27.5ad | 30.5b | 31.2b | 30bd | ||||

| UI | 576ab | 410abc | 522a | 480ab | 44.71ab | 44.49bc | 41.20abc | 40.95bd | 27.8a | 29.8b | 29abc | 29.2 | ||||

| UI+B | 612a | 486bd | 546a | 551abc | 47.13a | 46.92c | 43.86c | 43.67b | 31.5b | 31b | 31.3b | 32d | ||||

| Control | 479b | 281e | 500a | 467bc | 40.49cd | 40.25a | 37.52de | 37.3a | 24.5cd | 27a | 22.8d | 27.3ac | ||||

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||||||

| Genotype (G) | *** | ** | *** | * | *** | *** | ** | *** | ns | *** | * | *** | ||||

| Treatment (T) | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||||

| G*Te | * | * | ** | * | ** | * | ns | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | ||||

| Qualitative Traits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPC | Maltable (>2.2mm) | Retention (>2.5mm) | >2.8mm | ||

| Environment (E) | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Genotype (G) | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Treatment (T) | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| E*G | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| E*T | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| G*T | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| E*G*T | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| GPC (%) | Maltable (>2.2mm) (%) | Retention (>2.5mm) (%) | >2.8mm (%) | ||||||||||||||||||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | ||||||

| G45 | U | 7.96a | 9.78c | 9.46ab | 11.06abc | 98.31ab | 92.05a | 98.89ab | 75.45b | 87.61c | 49.82c | 88.62d | 22.46de | 56.82c | 6.46a | 54.63cde | 1.91a | ||||

| U+B | 8.61bc | 10.34cd | 11.22de | 9.09de | 98.93a | 92.28a | 98.99ab | 76.53bc | 89.45a | 53.29c | 89.31cd | 29.29de | 60.06b | 8.66abc | 57.37cd | 3.80ac | |||||

| UI | 9.77a | 11.08ae | 9.28a | 11.99cf | 98.97a | 92.35a | 98.98ab | 81.88cd | 89.79a | 67.17a | 90.55cd | 37.99d | 61.39b | 11.28bc | 59.15bcd | 0.93a | |||||

| UI+B | 10.33d | 10.47be | 10.71cd | 10.25ae | 99.06a | 93.58ab | 99.06b | 86.57d | 90.67a | 70.03a | 98.74a | 38.91d | 64.42ab | 12.61c | 62.11bc | 0.95a | |||||

| Control | 6.95c | 7.44e | 7.66b | 7.95d | 96.31b | 88.85f | 98.43cd | 74.68b | 84.54b | 40.62d | 84.04e | 11.66f | 42.18d | 5.57a | 41.71 | 0.71a | |||||

| G20 | U | 9.95ac | 11.71ab | 13.55e | 10.69ab | 98.59a | 95.37bcd | 98.69ad | 94.41a | 86.83c | 84.33e | 92.48c | 74.45ab | 60.74b | 28.73d | 67.1abc | 24.40a | ||||

| U+B | 9.88a | 11.95b | 10.70d | 11.85bcf | 98.99a | 96.72cde | 98.7ab | 95.79a | 89.51a | 86.43be | 92.95bc | 77.15a | 65.07ab | 31.84d | 69.09ab | 26.11a | |||||

| UI | 9.80a | 12.78d | 9.89c | 12.73f | 99.03a | 97.21de | 98.82ab | 96.02a | 89.79a | 89.65b | 93.24bc | 77.78a | 66.11a | 50.74e | 70.4ab | 17.35b | |||||

| UI+B | 10.95d | 11.39ab | 11.31de | 10.93abc | 99.09a | 97.61de | 98.89ab | 95.62a | 90.47a | 90.59b | 93.71bc | 79.87a | 67.40a | 56.56f | 72.45a | 27.44a | |||||

| Control | 8.18bc | 9.08c | 9.40ab | 9.14de | 96.48b | 94.86bc | 98.12c | 86.01d | 84.41b | 66.33ad | 88.21d | 68.35c | 48.09d | 7.49ab | 52.66e | 15.12b | |||||

| ANOVA | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Genotype (G) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |||||

| Treatment (T) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |||||

| G*Te | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | * | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | * | *** | ** | *** | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).