1. Introduction

Chitosan (CHI) is a linear polysaccharide composed of a copolymeric structure, consisting of (1-4) linked units of 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranose and 2-amino-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranose [

1,

2,

3]. It is primarily derived through the deacetylation of chitin [

4]. CHI is regarded as the second most abundant natural polysaccharide, following cellulose [

5,

6,

7,

8], and is extracted from crustacean shells and cephalopod endoskeletons [

9,

10,

11]. Recent interest in chitosan has surged within the fields of bioengineering and biomedicine [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], owing to its favorable biological characteristics, including bioactivity[

17], biocompatibility, biodegradability, low toxicity, and hemostatic properties [

4,

10,

18]. The mechanical properties of chitosan are largely determined by its macromolecular structure and the degree of deacetylation [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Additionally, its solubility in acidic aqueous environments makes CHI suitable for various processing techniques, including wet spinning [

22,

24,

25]. Wet-spun chitosan fibers have been previously produced using either multifilament spinning, which involves washing the fibers in organic solvents to prevent them from adhering to each other in the yarn [

26], or monofilament spinning, which eliminates this issue [

21,

27,

28]. In previous studies, yarns made from multifilament spun fibers have been washed with solvents such as acetone or methanol [

29]. Additionally, chitosan solutions for wet spinning have been formulated with organic cosolvents, including methanol [

30], isopropyl alcohol [

31], and propane-1,2-diol [

32].

Cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs), known for their exceptional mechanical properties, are considered promising reinforcement agents due to their nanometric size, high aspect ratio, elevated crystallinity, and ability to form both intramolecular and intermolecular networks through hydrogen bonding [

33]. These properties, coupled with their sustainability, stemming from abundant plant sources, make CNFs a promising biobased reinforcement material for composites [

34]. The reinforcement of polysaccharide hydrogels with nanocellulose has been previously reported [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], primarily in the form of films produced through a straightforward casting-evaporation technique [

40,

41]. In contrast, wet spinning necessitates precise management of solution viscosity and efficient material flow through spinneret orifices to prevent clogging [

42]. Furthermore, during the wet-spinning process, uniaxial alignment of both chitosan polymer chains and nanoparticles is anticipated to occur during extrusion, drawing, and drying stages [

28,

43,

44].

Low molecular weight chitosan (LMW) is another potential reinforcing material for chitosan fibers. Polymeric chitosan and chitosan oligomers have been demonstrated to increase the formation of phytoalexins or antimicrobial chemicals, which help to restrict disease transmission, owing to chitosan’s strong antibacterial capabilities [

45]. Kuyama et al. described the chemical synthesis of various sizes of chitosan oligomers, which resulted in particular biological activity [

46]. Lower molecular weight chitosan variations exhibit higher crystallinity, which is a key element in chitosan crystallization during wet spinning process optimization. Moreover, the biological activity of chitosan is strongly regulated by its molecular weight, degree of deacetylation, solution pH, and other variables, as well as the target organism [

47,

48]. In biomedical settings, LMW chitosan is notably efficient for anticancer activity [

49], oral insulin administration [

50], treatment of gastric ulcers [

51], liver protection [

52], blood cholesterol reduction [

53], diabetic control [

54], and antioxidant benefits [

55,

56].

Wet spinning of chitosan represents an important research area, addressing the limitations of chitosan-based materials, particularly in enhancing their mechanical properties [

57,

58]. These properties are often diminished in the wet state due to the highly hydrophilic nature of chitosan. The primary objective of this study is to combine high molecular weight (HMW) chitosan solutions with small amounts of CNFs and low molecular weight chitosan (LMW, “oligomers”), to develop chitosan-based spun composite fibers of high strength, by modulating the microstructure and properties of fibers in a wet-spinning process. This approach aims to enhance the performance of chitosan-based bioactive materials, with potential applications in biomedicine like tissue engineering, suture threads, knitted fabrics, wound healing, repairing of mechanical demanding tissues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Starting High Molecular Weight Chitosan and Its Depolymerization into Low Molecular Weight Chitosan

Chitosan of high molecular weight (HMW) derived from squid pen chitin was supplied by Mahtani company (Type: CHITOSAN 144, Batch No. 20120926, Veraval, Gujarat, India) The degree of acetylation (DA) was 2.5%. It was determined using H1 NMR spectroscopy, as described by Hirai et al.[

55] Chitosan (10 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of D2O that had been acidified with 5 L of strong HCl (12 M). The experiment was carried out using a Bruker ALS 300 spectrometer (300 MHz) at 298 K (Bruker GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany).

CHI of low molecular weight (LMW) was obtained by depolymerization of the above HMW chitosan. The depolymerization was carried out by nitrous deamination with sodium nitrite (NaNO

2). Each CHI solution starts with a concentration of 4% (w/v), which was dissolved in a stoichiometric amount of acetic acid to protonate the chitosan amine groups and then NaNO

2 is added in different ratios which are calculated using Equation (1).

Equation (1) shows the molar ratio CHI/NaNO2. The base solution of NaNO2 is added dropwise to each of the chitosan sample solutions while stirred vigorously for 24 h at room temperature (RT), allowing the NaNO2 to react with the glucosamine units and depolymerize the chitosan chains. Then, the chitosan was precipitated, centrifuged, washed and lyophilized. First, the precipitation of chitosan was carried out with NaOH and at a pH of 9. Second, the centrifugation was realized at 1000 rpm for 10min at 20 °C. While the supernatant was carefully poured into a beaker to avoid loss of coagulated chitosan, deionized water was added to the centrifugation vessels to wash the precipitated chitosan. The pH of the discarded liquid was measured to confirm that the CHI was completely washed. Third, the lyophilization was performed at -80 °C for 24 hours.

2.2. Cellulose Nanofibers (CNFs)

Gel-like suspensions of nanofibrillated cellulose (CNF) were created at the Centre Technique du Papier (CTP, Grenoble, France) from bleached pine sulfite dissolving pulp using a mechano-enzymatic process developed from Pääkkö et al. [

56]. The pulp was refined at 4.5% consistency for 25 minutes with a 12” single disk refiner before 1 hour incubation at 50 °C with a solution of endoglucanase FiberCare R

® (Novozymes Biologicals, Paris, France) at pH 5.0. The digested samples were processed further to generate a pulp solution with an SR (Schop-per-Riegler) value more than 80 and a mean fiber length less than 300 m. An Ariete homogenizer was used to process 2% (w/w) fiber suspensions, with one pass at 1000 pressure followed by three passes at 1500 bar. The surface charge density of the obtained CNFs was 40-80 mmol/kg. In other words, they had carboxylate moieties that were weakly charged. As previously reported, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to characterize the cellulose nanofiber morphology, which revealed an entangled network of linked nanofibrils with an average width of 35.2± 8.1 nm and bundles up to 100 nm wide.

2.3. Size Exclusion Chromatography/Multi-Angle Laser Light Scattering (SEC/MALLS) Characterization of Chitosan Molecular Weight

The chitosan molecular weight was measured using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and multi-angle laser light scattering (MALLS) [

57]. To prepare the eluent, a 0.1% (w/v) chitosan solution was made in an acetic acid/ammonium acetate buffer with a pH of 4.5 (AcOH (0.2 M)/AcONH4 (0.15 M). Prior to SEC measurements, the fluid was filtered via 0.22 µm pore size membranes (Millipore). The chromatographic apparatus consisted of an IsoChrom. The LC pump (Spectra-Physics, Charbonnières les Bains, France) was linked to a Protein Pack 200 SW column (WATERS, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France) and a TSK gel G6000 PWXL column (Merck, Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). A Dawn DSP (Wyatt Technology, Toulouse, France) Multi-Angle Laser Light Scattering (MALLS) detector at 632.8 nm was connected to a WATERS 410 differential refractometer in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France.

2.4. Preparation of Viscous Collodions Containing Low- (LMW) and High-Molecular Weight (HMW) Chitosans with Cellulose Nanofibrils

To spun yarns, viscous solutions with low and high molecular weights (LMW and HMW) with nanofibrillated cellulose (CNF) were created. A fine powder of high-molecular-weight (HMW) chitosan was mixed with different percentages of low-molecular-weight (LMW) chitosan (molar ratio of 20 and 50 wt%) to yield mixed chitosan acetate solutions (hereafter named collodions or dopes) containing a total polymer concentration of 4% (w/w). The dispersions were sonicated with a SONOPULS ultrasonic homogenizer (Bandelin electronic GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for 5 min at 40% amplitude. Then, acetic acid was added in stoichiometric amounts to protonate the amine moieties of chitosan (DA = 2.5%) to solubilize the chitosan. The mixture was kept under mechanical stirring overnight.

Table 1.

Summary of Composition of Formulations of Low (LMW) and High Molecular Weight (HMW) Chitosan Filled with Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF) Used in the Fiber Spinning.

Table 1.

Summary of Composition of Formulations of Low (LMW) and High Molecular Weight (HMW) Chitosan Filled with Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF) Used in the Fiber Spinning.

| Formulation |

HMW |

LMW |

CNF |

| % (w/v) |

% (w/v) |

% (w/w) |

| |

r20 |

r50 |

|

| F1) |

CHI/r20 |

3.4 |

0.6 |

0 |

0 |

| F2) |

CHI/r20/CNF0.3 |

3.4 |

0.6 |

0 |

0.3 |

| F3) |

CHI/r20/CNF0.4 |

3.4 |

0.6 |

0 |

0.4 |

| F4) |

CHI/r20/CNF0.5 |

3.4 |

0.6 |

0 |

0.5 |

| F5) |

CHI/r50 |

3.4 |

0 |

0.6 |

0 |

| F6) |

CHI/r50/CNF0.3 |

3.4 |

0 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

| F7) |

CHI/r50/CNF0.4 |

3.4 |

0 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

| F8) |

CHI/r50/CNF0.5 |

3.4 |

0 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

| F9) |

CHI |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| F10) |

CHI/CNF0.3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0.3 |

| F11) |

CHI/CNF0.4 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0.4 |

| F12) |

CHI/CNF0.5 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0.5 |

2.5. Rheological Analysis of of Cellulose Nanofiber-Filled High/Low Molecular Weight Chitosan Viscous Formulations

An AR2000 rheometer (TA Instruments Ltd., New Castle, DE, USA) with a cone-plate geometry (diameter: 25 mm; angle: 4°) was used to assess the rheological properties of various chitosan-based viscous formulations at 25°C. The gap size was 0.116 mm, and a solvent trap was employed to prevent drying or evaporation. The cone-plate design ensures a consistent shear rate throughout the sample. The analysis was conducted in triplicate, operating in continuous mode within a shear rate range of 0.01 to 500 s⁻¹. Flow curves, which are plots of steady-state shear viscosity against shear rate for the viscous collodions, were generated to determine the Newtonian viscosity in the low shear rate range plateau.

2.6. Gel Spinning of Chitosan Mixture Collodions

For the processing of the fibers, it was used a gel spinning setup that consisted of a 30 mL syringe barrel that contained the chitosan/cellulose nanofibers viscous formulation, which was connected to a controlled air-pressure clip of a Performus I Nordson EFD dispenser linked to a compressed air source.[

32] The syringe was attached to a conic needle with a tip diameter of 0.58 mm (gauge 20, pink, Nordson EDF). Briefly, the biopolymer viscous extrudate was directed into a coagulation bath containing 3M NaOH The coagulated hydrogel macrofilament was pulled with aid of a first DC motor. Afterward, the hydrogel macrofiber passed through a washing bath of deionized water, stretched and pulled through a second spinning motor. Third and fourth spinning motors were implemented to further stretch the fibers, while allowing them to dry. Finally, the spun fibers were collected onto a bobbin. Composite fibers of CHI/CNF were processed using viscous formulations with a total CHI concentration (LMW and HMW) of 4 wt %, and CNF contents of 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 wt %, respectively.

2.7. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR)

The chitosan/cellulose nanofiber spun fibers were characterized by FTIR in attenuated (ATR) mode using an FTIR-ATR Spectrum 65 spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Spectra in the range of 400–4000 cm−1 were recorded by the scans. Reference spectra of the used chitosans powder and of the nanofibrillated (CNF) were also recorded.

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The fracture and the lateral surfaces of the CHI/CNF spun fibers were observed using a FEI Scios DualBeam FIB/SEM microscope at an accelerated voltage of 5 kV after sputter-coating an ultrathin Au layer.

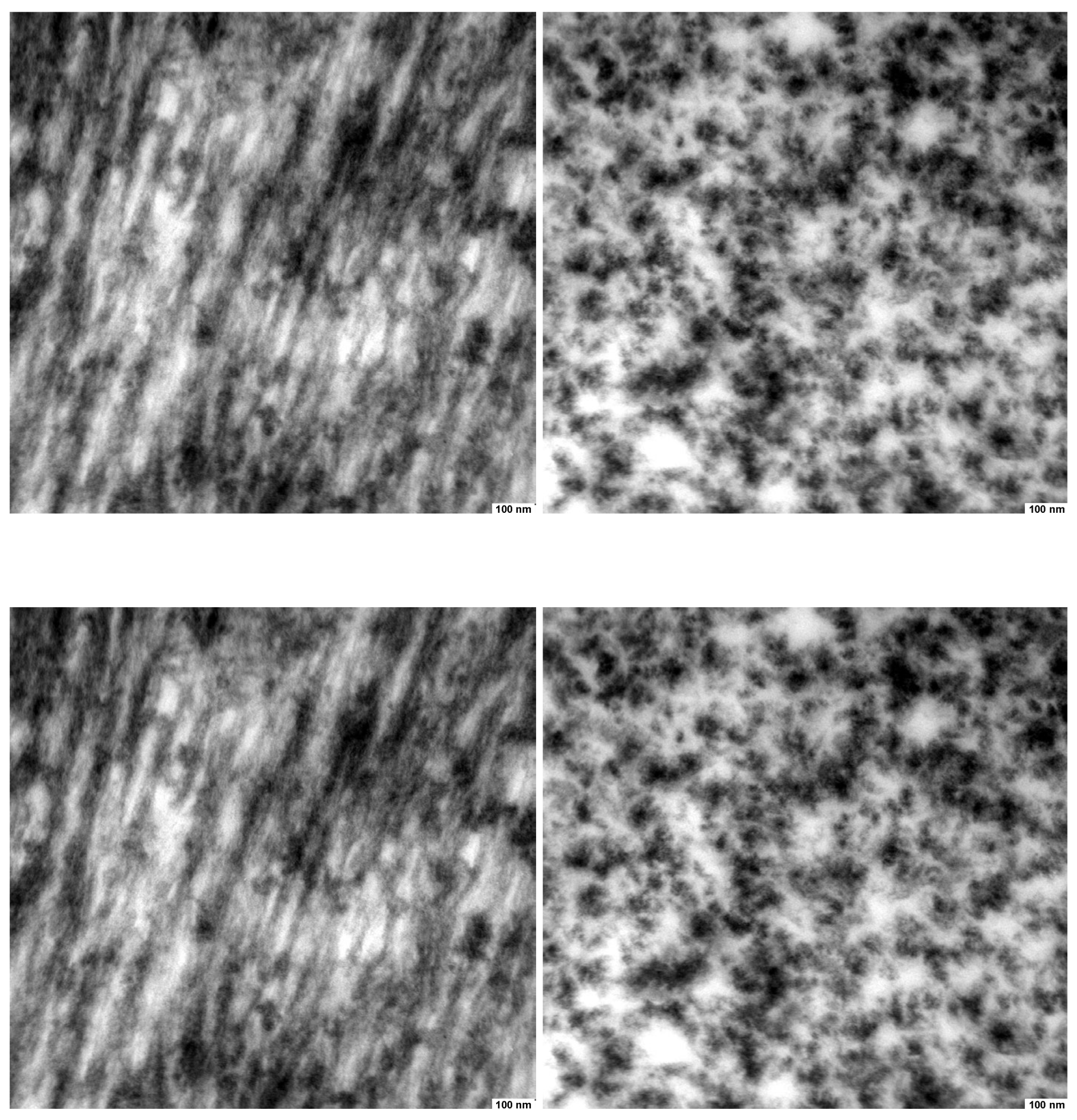

2.9. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) of Ultrathin Fiber Section

Spun fibers were fixed in 10% formalin, 2% glutaraldehyde in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) overnight at 4 °C. The sample was then incubated in 1% uranyl acetate in 70% ethyl alcohol overnight at 4 °C and further dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethyl alcohol and finally acetone. After embedding in Durcupan resin, ultrathin sections containing the spun fiber were cut either parallelly to the fiber axis, or perpendicular (cross section view) by using a UC7 Ultramicrotome (Leica), and collected on Formvar-coated copper grids. Post staining was done for 1 min with 3% lead citrate followed by imaging using a Zeiss Leo 912 transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

2.10. X-Ray Synchrotron Scattering (WAXS and SAXS)

X-ray scattering analyses at wide angles (WAXS) of the collected spun fibers were performed by using synchrotron and/or laboratory X-ray sources. Synchrotron X-ray analyses were performed at the D2AM/BM2 beamline at the European synchrotron radiation facility ESRF (Grenoble, France). The processed fibers were wrapped 10 times around a metal sample holder with a hollow center to allow the X-ray beam to pass through a bundle of fibers as previously described [

32]. The setup allowed for X-ray scattering/diffraction analyses in transmission mode. Synchrotron wide angle X-ray scattering data were collected at a wavelength λ= 0.77 Å using a 2D detector WOS (IMXPAD company, La Ciotat, France). Chromium oxide was used as standard to calibrate the scattering vector q-range. In the data treatment, transmission corrections and background subtraction were performed.

2.11. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis of the CHI/CNF spun fibers was performed on a STA449 F5 Netzsch thermal gravimetric analyzer. Approximatively 10 mg of cut fibers were weighed in a platinum pan and heated from room temperature (~25 °C) up to 650 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min, under nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 100 mL/min.

2.12. Tensile Testing

Microtensile tests of the CHI/CNF spun fibers were performed using a DEBEN minitester equipped with a 20 N load cell. All tests were carried out at room temperature and a constant strain rate of 0.5 mm/min. Fiber segments were fixed to the tester allowing a span length of 3 mm between the clamps, corresponding to the initial length (L0) for tensing of the fiber. The nominal stress σ was calculated as the ratio of the applied force F to the initial cross-sectional area A of the fiber (σ = F/A), whose dimension was determined using a light optical microscope (Olympus BX Series, Hamburg, Germany). The nominal strain ε was expressed as the ratio of the extension of the fiber with respect to its initial length L0 (ε = ΔL/L0 = (L-L0)/L0). The Young’s modulus (E), yield stress (σy) and strain (εy), ultimate stress (σb) and strain at break (εb) were determined from the obtained stress–strain curves, considering at least ten replicates (n = 10) for each spun fiber formulation.

3. Results

3.1. Rheological Behavior of Mixture Solutions of Low (LMW) and High-Molecular Weight (HMW) Chitosan Viscous Formulations Filled with Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF)

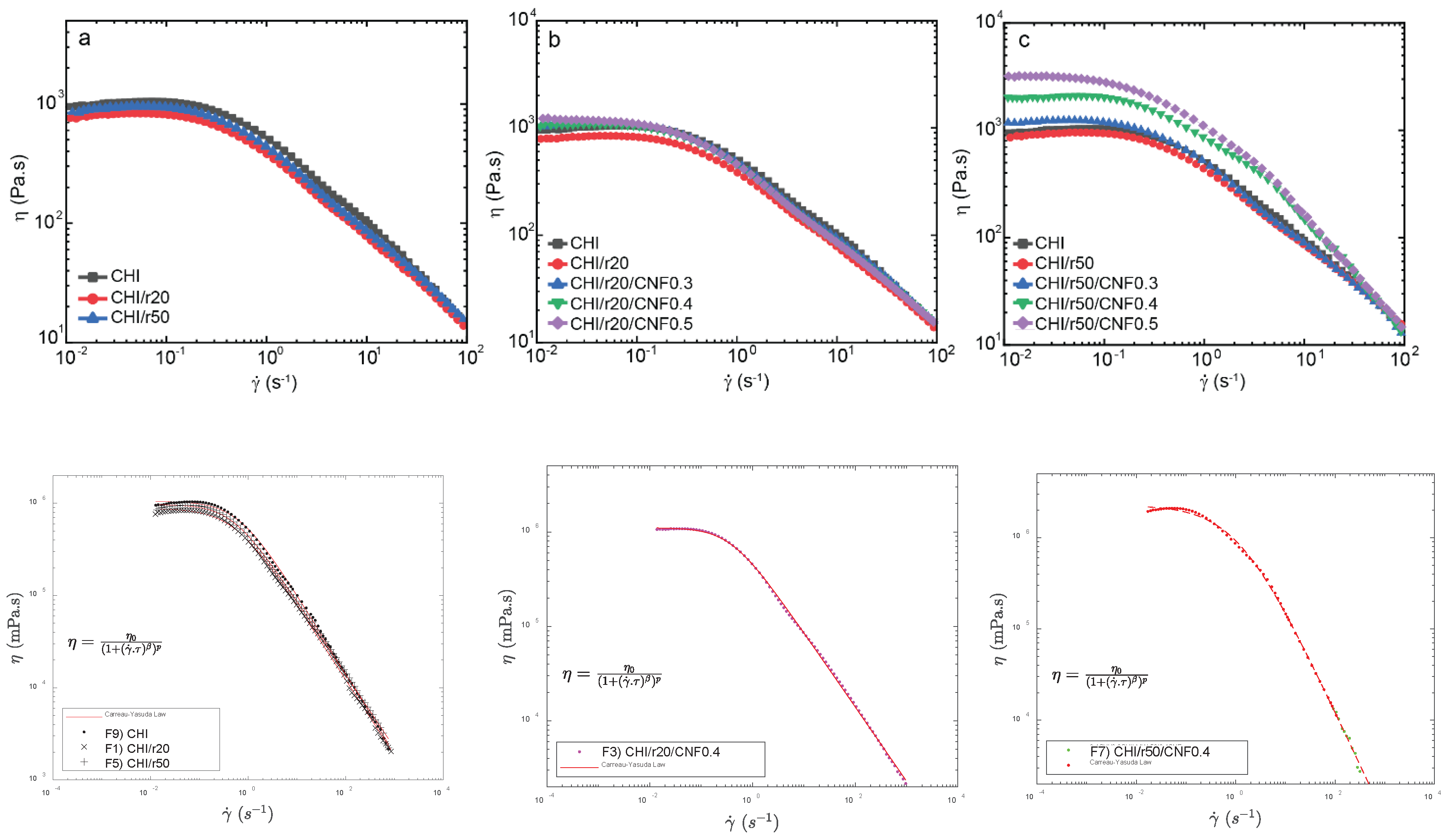

Figure 1 shows the flow diagrams of the different formulations wnen adding to the chitosan/cellulose nanofiber formulations the produced low molecular weight chitosans (synthesized for molar ratio r of glucosamine to NaNO2 of 20, and of 50). As expected, at adding low molecular weight to the system initially consisting of high molecular weight reduced the Newtonian viscosity of the collodions. The HMW chitosan will have a reduced polymer movement, leading to a higher viscosity compared to LMW chitosan [

34]. Thus, chitosan concentration and average molecular weight of the mixture allows for control over viscosity. Then, the incorporation of CNF into the mixture of high and low molecular weight chitosans re-increased the zero-shear viscosity, with this effect being enhanced when adding the chitosan of intermediate low molecular weight, this is, of “higher” low molecular weight as for r50 to the systems having the highest contents of CNF (0.4 and 0.5 % (w/w)). This might be explained due to strong interactions between CNF and chitosan macromolecules in those suspensions of higher concentrations of CNF and higher average molecular weight of chitosan [

32].

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between viscosity (η) and shear rate (γ̇) for suspensions containing high (HMW) and low molecular weight chitosan (LMW for ratios r20 and r50), reinforced with varying CNF contents (0, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 wt%). Each dispersion exhibits a non-linear, non-Newtonian shear-thinning behavior typical of CHI solutions, where η decreases as γ̇ increases due to the disentanglement of polymer chains and the disruption of the initial polymer solution structure, which enhances chain orientation [

18,

31,

33]. Further comparisons were made for the systems of CHI/r20/CNF and CHI/r50/CNF at different CNF contents (Figure 1b,c). The use of low molecular weight produced for r50 introduces longer chains than those produced for r20. Together with CNFs, they form intermolecular aggregates that limit polymer chain movement and disentanglement, resulting in a more rigid structure [

34], also increasing shearing effects.

At higher shear rates, the typical non-Newtonian shear thinning behavior of chitosan solutions is observed, with a Power law decrease of viscosity with increasing shear rates [

33]. The flow behavior is related to the disentanglement of the chitosan chains, also inducing chain orientation. Overall, flow-induced orientation tends to form an anisotropic structure under the action of a shear field [

18,

31]. In the highest shear range, the viscosity similarly decreased in the “pure” chitosan solutions and in the chitosan/cellulose nanofiber viscous suspensions, revealing that the shear-thinning behavior in the latter is governed by the disentanglement of chitosan chains and practically not affected by the presence of the nanofibers, which should get oriented in the flow direction [

33,

59]. This is advantageous to achieve the extrusion of nanofiber reinforced viscous chitosan systems without compromising the extrudability of chitosan systems themselves as in fiber spinning processes. This should be the first premise to achieve the processing of nanofiber-filled chitosan fibers by wet spinning to develop fibers of improved mechanical performance, as envisaged in this work.

A Carreau-Yasuda law (Equation (1)) was used to model the flow diagrams (

η vs. shear rate) of the chitosan solutions [

60,

61,

62,

63] and the chitosan/cellulose nanofiber viscous suspensions that also contained low molecular weight chitosan as illustrated in

Figure 1 (Bottom).

where

η0 is the Newtonian or zero-shear viscosity, τ is the transition time, β ist the exponent that accounts for the width of the transition region between the zero-shear viscosity and the Power law region, and p=(1-β)/β is the viscous exponent. The parameters obtained for the different formulations after modelling with the Carreau-Yasuda law are displayed in

Table 2.

For the CNF 0.4 and 0.5, having LowMW of r50, a second fast flow mode had to be introduced to have a good fit with model. This could be explained to a representative interaction between the CNF and the low molecular weight chitosan of intermediate Mw (for r50) specially bein significant at those high contents of cellulose nanofibers (0.4 and 0.5 % (w/w))

3.2. Spun Fiber Spun Fibers Chemical Structure. Macromolecular Structure of Chitosan and Chemical Composition of Composite Fibers. Size-Exclusion Chromatography Coupled to Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC/MALLS)

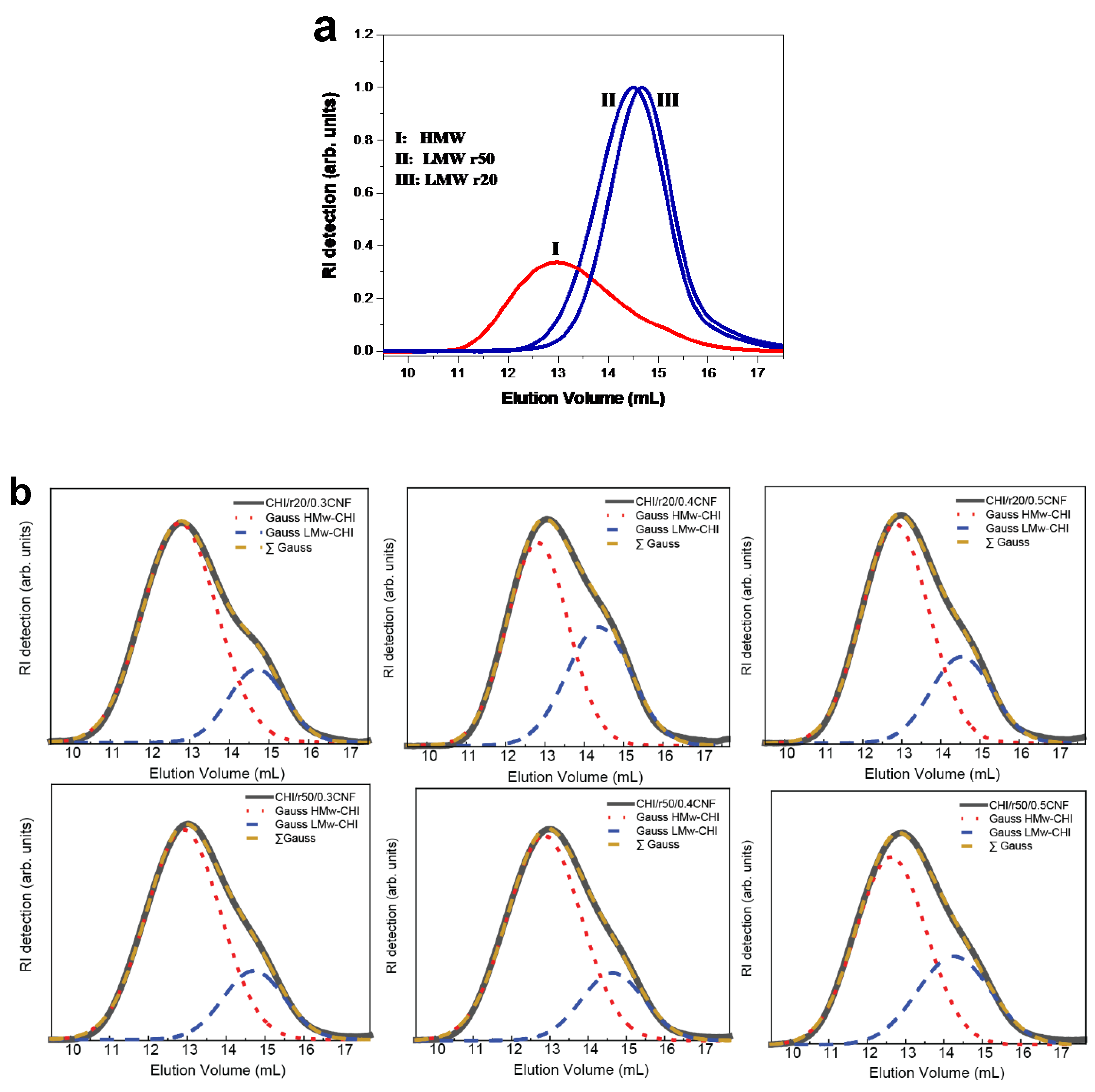

Figure 2a displays the size-exclusion chromatograms (SEC) of the starting chitosan of high molecular weight (HMW) as well as of the low molecular weight chitosans (LMW) produced by nitrous deamination polymerization of the HMW sample. Figure 8 confirmed the decreasing of chitosan molecular weight by varying the molar ratio r of glucosamine to NaNO

2 (for example: r20 and r50).

Figure 2 also shows the chromatograms of the chitosans contained in the different fiber formulations. For this analysis, the spun fibers were redissolved in buffer pH 4.5 (AcOH (0.2 M)/AcONH4 (0.15 M) for solubilization of chitosan and the obtained system was subsequently filtered through 0.22 µm pore size membranes (Millipore). SEC analysis allowed verifying the obtaining of bimodal distribution of molecular weights, containing chitosan of high and low molecular weight after the fiber spinning process, with elution volumes corresponding to that of the HMW and LMW chitosans used in viscous collodion. Due to the non-solubility of CNF in buffer pH 4.5, it was possible to reconstruct the chitosan weight distribution within the fiber composite.

Figure 2b shows, for each formulation, two Gaussian curves, representing the distribution of components of HMW and LMW chitosans, respectively. It confirmed that despite the mobility of the low molecular weight chains, they were not removed during coagulation in base or water washing baths and remain present in the final fibers (

Figure 2b).

Table 2 summarizes the obtained molecular weight and polydispersity index (Đ) of chitosan in the different samples.

Table 2 shows the molecular weight and polydispersity index (Đ) of the different CHI samples. Pure CHI exhibits a relatively low Đ (≤ 1.6), indicating a narrow distribution of molecular weights. However, the addition of CNF significantly increases the overall dispersity due to the size difference between CNF (larger) and CHI (smaller). It is important to note that the degree of acetylation (DA) in CHI remains unchanged after the depolymerization reactions by nitrous deamination, suggesting that the acetylation process is not affected by the changes in molecular weight during this reaction.

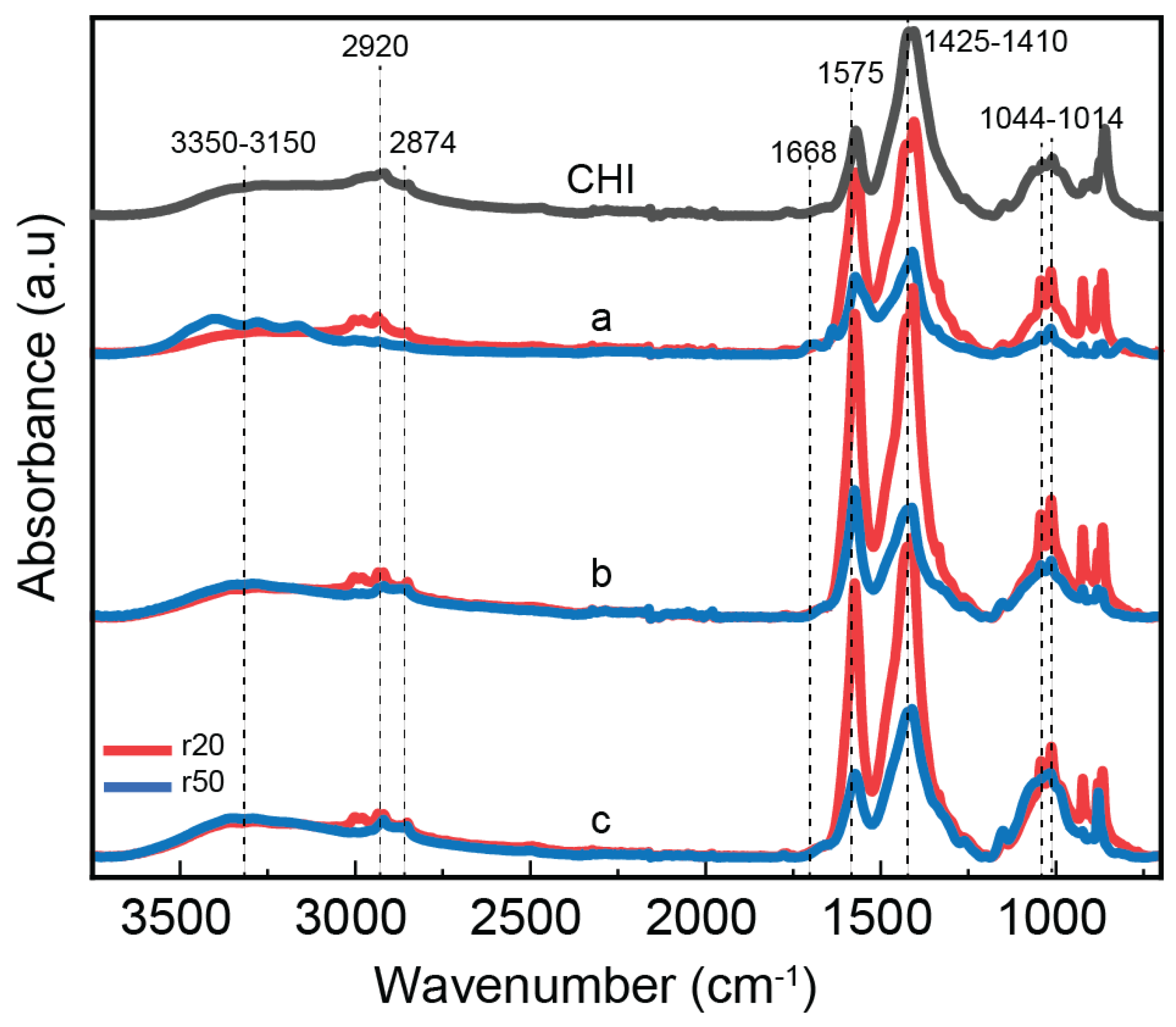

3.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

The bonding mechanism between chitosan and CNF in the composite fibers was investigated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (

Figure 3). Both chitosan alone and chitosan/CNF composite fibers exhibit a broad absorption band between 3350-3150 cm-1, corresponding to O-H and N-H stretching vibrations. This indicates the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds between CNFs and CHI molecules [

43]. The peaks at 2934 and 2852 cm-1 are attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the C-H group, respectively [

45]. A characteristic absorption related to the amide I group in CHI is observed as a shoulder at 1671 cm-1, corresponding to C=O stretching [

46,

47]. Additionally, the amide II group presents a peak at 1574 cm-1, which corresponds to both N-H bending vibration and NH3+ symmetric deformation. An increase in CNF content leads to a rise in the intensity of the latter peak, indicating favorable interactions (electrostatic and hydrogen bonding) between the COO- group of cellulose and the amine group of CHI [

45,

48]. Furthermore, methylene and methyl groups are visible in the range of 1425-1409 cm-1, and the stretching of the C–O groups from primary and secondary hydroxyl groups shows characteristic bands at 1044 and 1013 cm-1, respectively [

48,

49]. Finally, CHI and other polysaccharides exhibit a fingerprint region with peaks between 1250 and 800 cm-1.

3.4. Morphology and Microstructure of Fiber Yarns

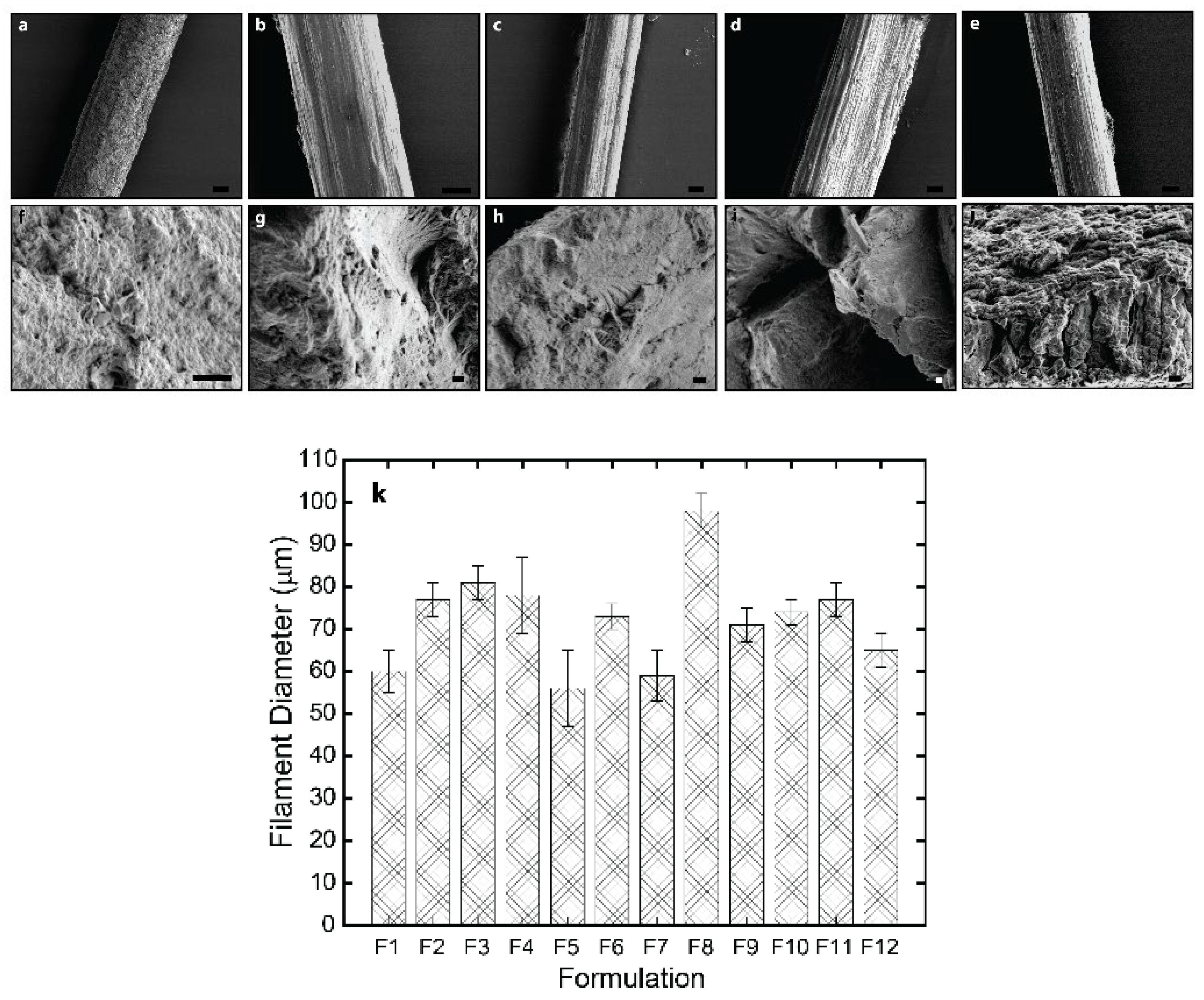

The lateral and cross-sectional surface morphology of the spun fibers was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy of ultrathin sections, which analyses were performed transversally (cross-section) or along the axial direction of fibers. The SEM micrographs in

Figure 4 reveal good interface between the CNF and chitosan(s) matrix due to the similar structures of polysaccharides chitosan and cellulose as well as the possibility of electrostatic interaction between them at the surface of cellulose nanofibers. The spun fibers display a relatively homogeneous inner microstructure, which confirms strong compatibility between nanofiber filler and matrix and thereby an effective formation of composite, with the presence of also low molecular weight chitosan into the matrix, and low contents of CNF [

32]. For the higher CNF contents (0.4, and 0.5 % (w/w)), the outer surface of fibers is characterized by a fibrillar topography for formulations containing any of the synthesized low molecular weight chitosans (for r20 and for r50), which effect should result from the spinning and stretching process and specially enhanced for higher nanofiber contents in composites. The orientation of that outer fibrillar microstructure observed by SEM aligns parallel to the stretching direction [

12]. In the cross-sectional microstructure, an internal homogeneity is also observed for all spun fibers with CNF contents 0.3 and 0.4 % (w/w) as well as for the fibers with CNF content of 0.5% with the low molecular weight chitosan of lower Mw (for r20). In contrast, for spun fibers with that higher CNF content of 0.5% incorporating low molecular weight chitosan of higher Mw (for r50) it seems that the homogeneous microstructure starts to be disrupted, due to the higher concentration of nanofibers and increase of average molecular mass of chitosan chains.

Figure 4k shows that the average diameter of the spun fibers ranged from 60 to 98 microns, with the presence of r50 “oligomers” and highest CNF content (0.5 % (w/w)) contributing to an increase in diameter.

Microscopy observations at higher resolution, which were performed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of ultrathin fiber sections, allowed better characterizing the inner microstructure of the fibers. In the micrographs of

Figure 5, a pattern of parallel arrangements with a period width of 50-100 nm is observed when looking at sections cut along the spun fiber axis (

Figure 5 Top). This observed period in the patterns is in the range of the average width of the nanofibrils constituting the nanofibrillated cellulose filler CNF, which nanofibrils have average width of 35.2± 8.1 nm with bundles up to 100 nm (see section §2.2 Cellulose nanofibers). The TEM results might reveal the good dispersion of the cellulose nanofibers in the chitosan matrix, even at the resolution of single nanofibril bundles as present in the starting cellulose nanofiber material (CNF suspension) which was added to the chitosan-based viscous collodion to be spun into hybrid fibers. It is worth noticing that a preferential orientation in the direction of the fiber axis is observed in the patterns, which might coincide with the orientation of cellulose nanofibers inside the composite, and/or the orientation of the semicrystalline chitosan produced after stretching and drying while spinning. The cross-sectional ultrathin section of the spun fibers in TEM micrographs (

Figure 5 Bottom) shows homogeneously distributed bright and dark regions, which might corresponds to regions containing cellulose nanofiber and chitosan, respectively, matching with the patterns observed when looking at orientation along fiber direction as described above (

Figure 5 Top).

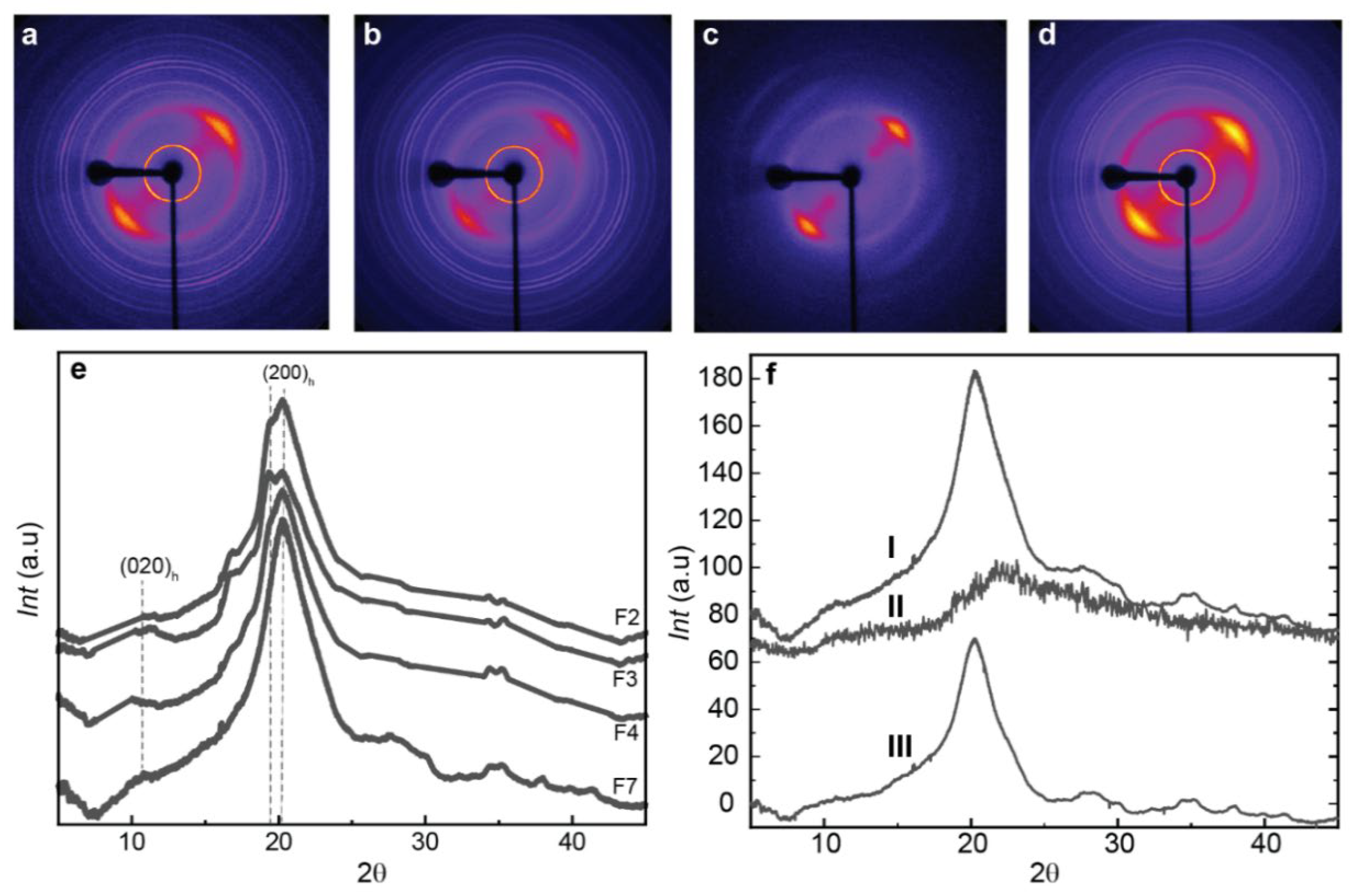

3.5. Crystalline Microstructure of Spun Fibers. Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (WAXS)

The hybrid chitosan/cellulose nanofiber spun fiber composites were examined using X-ray diffraction, which shows appropriate anisotropic behavior along the direction of fiber stretching (

Figure 6), with preferential orientation of the hydrated chitosan allomorph as displayed in the 2D diffraction images by the arc signal of the corresponding crystallographic planes [

64].

Figure 6e displays the X-ray scattering radial average profile curves with the main crystallographic peaks of the biopolymers. These peaks are observed at 2θ = 10.61° for the (020)h planes of the hydrated crystalline polymorph of chitosan, and at 19.85° and 20.38° for the reflections of the (200)

h and (220)

h planes of the hydrated polymorph. The overall spectra are characteristic of hydrated CHI, like those described by Clark and Smith [

35,

42]. It is worth remarking that in some samples, the washing with water did not effectively remove the salt sodium acetate produced as byproduct during neutralization, and crystallographic signal of that salt was observed in the WAXS pattern of some fiber samples. For quantitative analyses of WAXS data, the sharp peak signals of salt were removed in the WAXS radial profile, to better investigate the crystalline aspects related to chitosan and cellulose.

Chitosan is a semicrystalline polymer, composed of both amorphous and crystalline phases. The crystallinity index (CrI) gives insight into the percentage of crystalline regions with respect to the sum of amorphous and crystalline phases. Moreover, higher crystallinity typically leads to increased rigidity and thereby stiffness and strength of the material. To calculate the crystallinity index (CrI), we used the diffractogram of an experimentally obtained amorphous chitosan. The amorphous diffractogram was adjusted by a coefficient, to match the amorphous background in the diffractograms obtained for the spun fibers (

Figure 6f). The CrI was determined by comparing the amorphous contribution with the total area of the diffractogram.

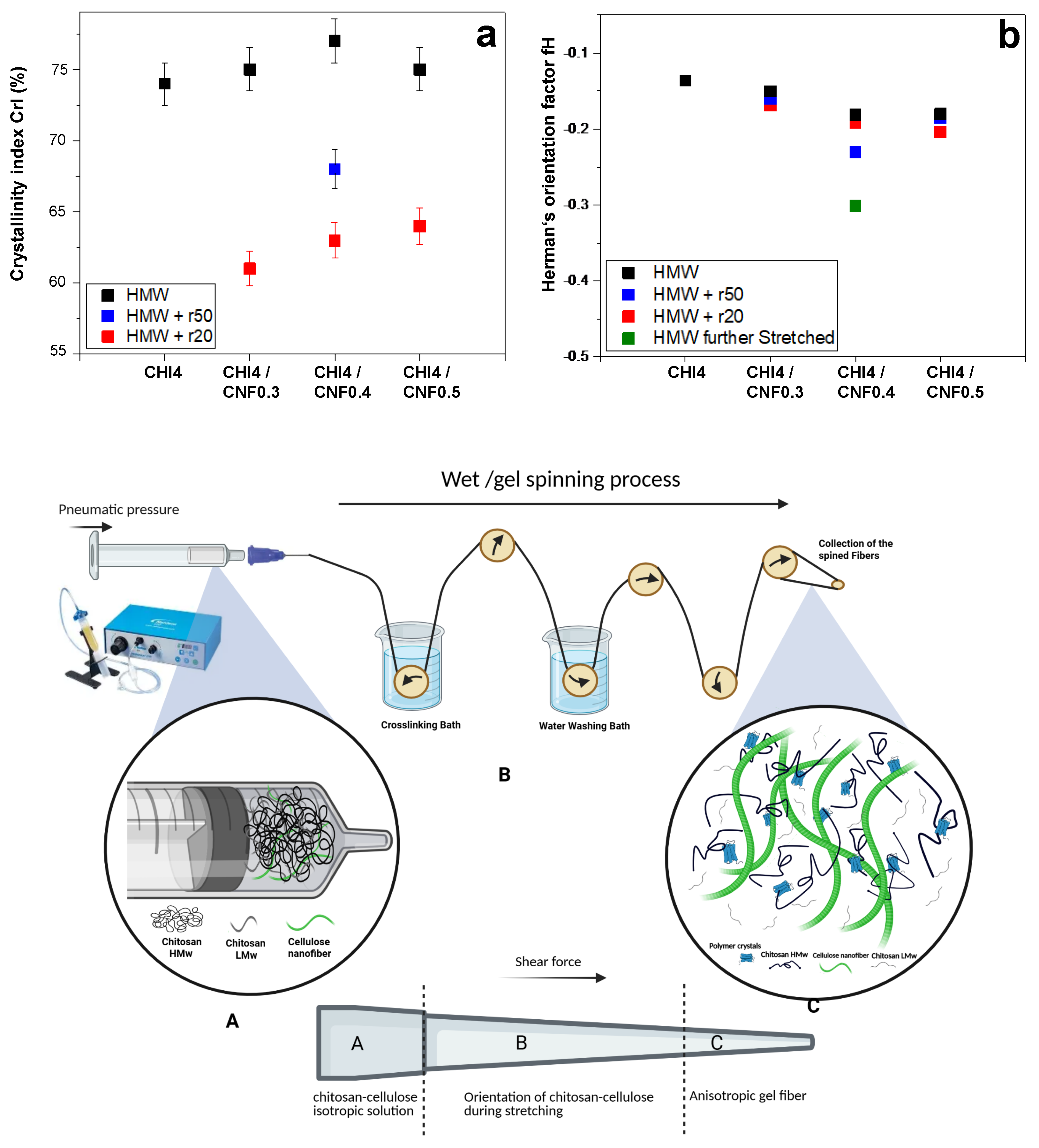

Figure 7 presents the CrI values obtained for spun fibers of different formulations. It can be observed that the combined addition of LMW chitosan and CNF to HMW chitosan contributes to increasing the crystallinity in the fibers, with a hugher contribution being observed when adding low molecular weight produced for r50 than for r20. This is a higher average molecular mass of chitosan will contribute to obtaining fibers of higher crystallinity. The observed increase in CrI is primarily associated with the presence of CNF, as chitosan polymer chains adsorb to the CNF surface during the coagulation and stretching processes, acting the nanofiber as nucleating points to promote the growth of chitosan crystals [

32].

The Herman orientation factor (fH) can be calculated from the 2D WAXS images. The Herman equation (Equation (2)) defines and relates the orientation factor to the amount of crystallites within the fibers. The value used is the average cosine of

φℎ,

k,

l, which corresponds to the angle between the fiber axis and the normal to the crystallite planes. This angle is obtained from the intensity and the diffraction values (q) derived from the X-ray diffraction patterns [

44].

Herman’s factor values closer to -0.50 indicate a higher orientation of the crystals within the fibers, while values closer to 0 signify isotropic behavior. Interestingly, the addition of both chitosan “oligomers” and cellulose nanofibers contribute to enhance orientation (

Figure 7). Herman’s orientation factor values around -0.20 were achieved, with further enhanced orientation values of -0.23 for the formulation F7 (CHI/r50/CNF0.4), consisting of low molecular weight chitosan of intermediate Mw, of cellulose nanofiber content 0.4% (w/w), and of high molecular weight chitosan. Then, a further stretching of this fiber led to further increase alignment within the fibers and Herman’s orientation factor of -0.3 was achieved (

Figure 7).

To summarize, the schematics in

Figure 7 illustrates how the contribution of cellulose nanofibers, serving as nanoreinforcement and surface for nucleation of chitosan crystallites, contributes to the increase crystallinity and orientation. This effect combined with the shearing during extrusion, the stretching and drying during spinning, yields fiber composites of enhanced crystallite orientation. This is specially enhanced when incorporating into the CHI/CNF formulation a chitosan of intermediate low molecular weight chitosan like Mw: 4.4 x 10

4 g/mol produced for r50. This could be attributed to the presence of shorter chains, but not that short as for r20 (Mw: 2.9 x 10

4 g/mol), which ensures higher molecular mobility of shorter chains, but still allowing for some entanglement of intermediate Mw chains to sense shearing and contribute to orientation (

Figure 7). These interpretations could serve as the basis for the analysis of the spun fiber composite properties like thermal and mechanical in the following sections.

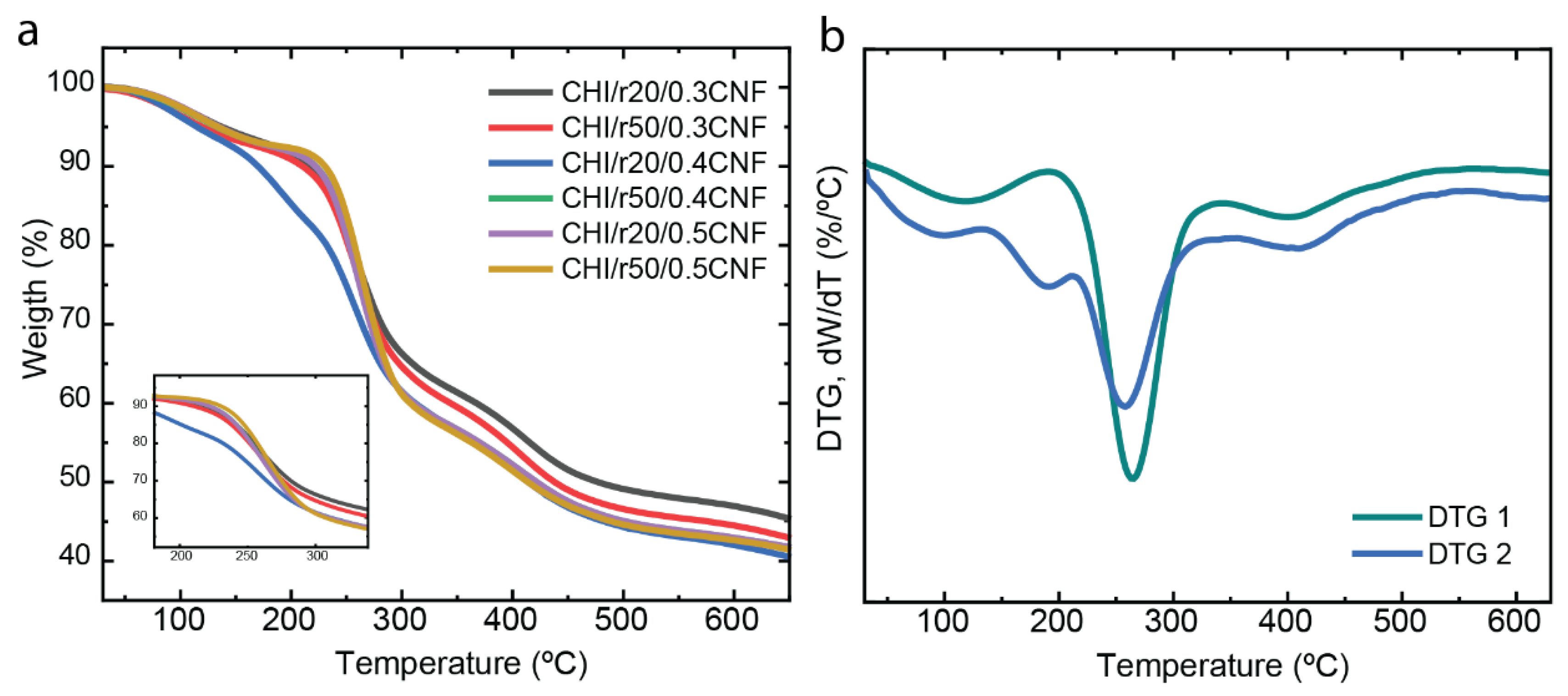

3.6. Thermal Properties

The thermal stability and decomposition patterns of the composite fibers (CHI/LMW/CNF) were evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA).

Figure 8 demonstrates how the presence of chitosan “oligomers” and nanometric CNF influences the thermal behavior of the CHI matrix. The use of CNF fibers is known to enhance the thermal stability of composite fibers [

32,

50,

51]. Most of the samples exhibit similar decomposition patterns, with an initial mass reduction observed at around 100 ºC, which corresponds to water desorption associated with the hydrogen-bonding in the polysaccharide/water structure. The next phase, visible at 260 ºC, corresponds to the decomposition of the polysaccharide macromolecules of both CHI and CNFs. Finally, at approximately 400 ºC, the degradation of any residual sodium acetate from the neutralization step occurs, which was not entirely removed during the washing steps with water when spinning the composite fibers [

32,

52,

53,

54].

Interestingly, the CHI/r20/CNF0.4 formulation shows a different behavior compared to the other samples, with three distinct degradation steps after water desorption (around 100 ºC). The first degradation step, at 189 °C, is likely related to the breakdown of the “weak link” of CHI chains and added oligomers [

42]. The subsequent degradation steps around 260 ºC and 400 ºC, corresponds to the decomposition of the macromolecules and the residual sodium acetate, respectively.

3.7. Micromechanical Properties

The incorporation of CNFs up to 0.4 wt% into the CHI matrix leads to a significant enhancement in the overall mechanical performance of the composite fibers. The addition of CNFs improves the nanocomposite’s mechanical properties, attributed to the high aspect ratio of the nanofiber reinforcement, which promotes efficient stress transfer between the matrix and the fibers [

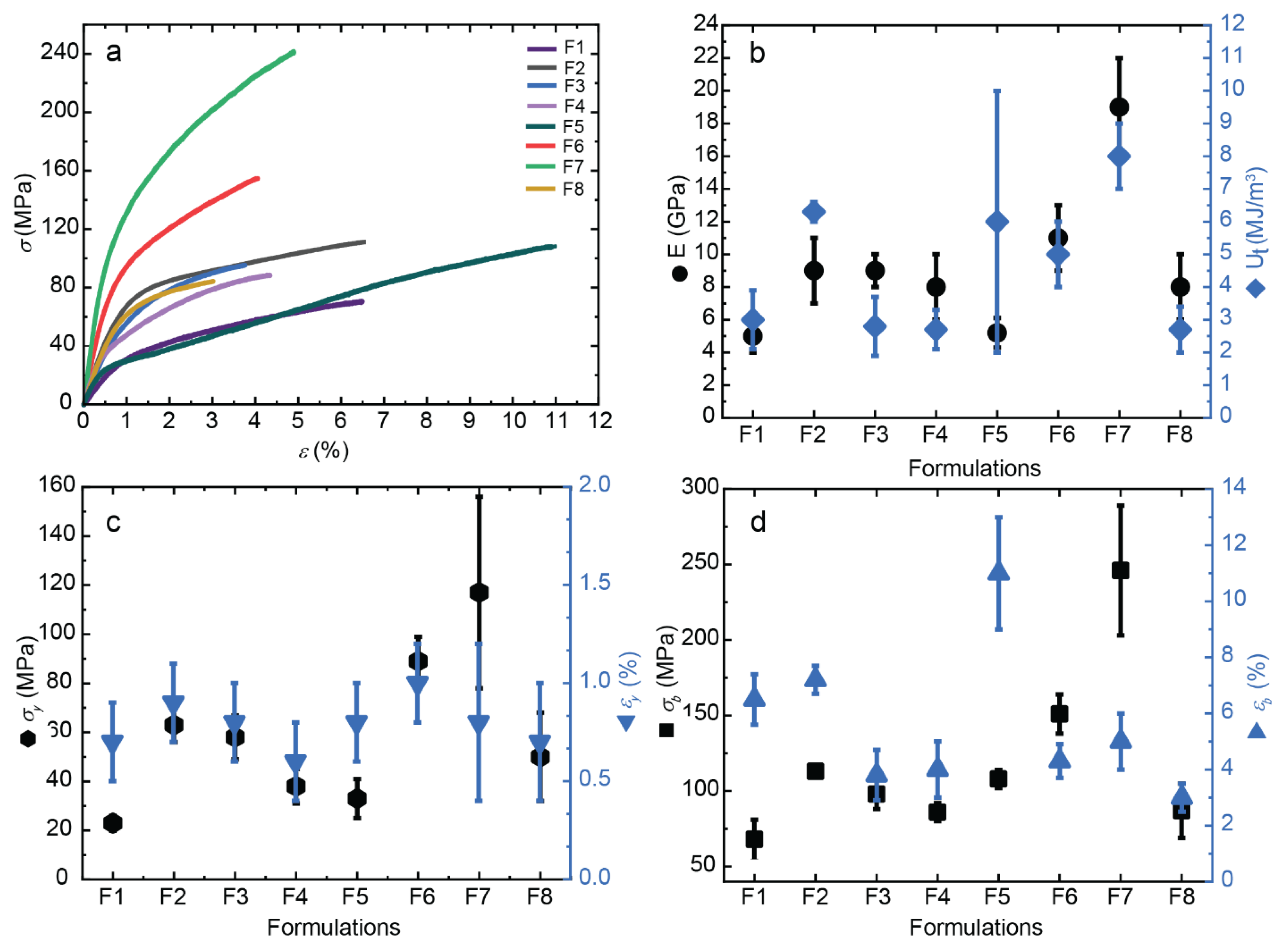

32]. This study focuses on examining the influence of “oligomers” on the mechanical behavior of the composite fibers, specifically evaluating parameters such as the Young’s modulus (E), yield point (σy and εy), stress-at-break (σb), elongation-at-break (εb), and toughness (Ut).

Figure 9 illustrates the stress-strain curves for all formulations. When comparing composite fibers with different oligomers, r50 (F5-F8) demonstrates superior properties compared to those with r20 (F1-F4). Previous studies have shown that an optimal CNF content of 0.4 wt% yields the best results, which is why this condition was also selected for combination with the “oligomers” in this study. The oligomers significantly influence the stiffness (E) of the samples, with r50 reaching 19 GPa, while r20 remains at 9 GPa. Furthermore, the yield and tensile strength (σy and σb) of the composite fibers with r50 are 101% and 151% higher, respectively, compared to those with r20. The increase in the crystallinity index in fibers with LMW chitosan for r50 contributes to the highest stiffness of composites, whereas the shorter chains produced for r20 allowed for higher molecular mobility, leading to a reduction in overall mechanical performance.

To achieve the highest stiffness (E modulus) and strength (σ

y) of spun fibers, in terms of chitosan molecular, the optimum composition seems to be that containing high molecular chitosan combined with a low molecular weight chitosan of not too short chains, this is, of intermediate Mw. The low molecular weight chitosan should have a Mw between that for r50 (Mw: 4.4 x 10

4 g/mol) and that of HMW itself (Mw: 5.5 x 10

5 g/mol). The results showed that both, low molecular weight chitosan and CNF content positively influence on Young’s modulus and yield stress of spun hybrid fibers. However, only the chitosan molecular weight seems to have significant influence on fiber toughness. Thus, the highest Young’s modulus, yield stress and toughness are achieved at adding a low molecular weight chitosan of intermediate Mw value (e.g., for r50 sample) and cellulose nanofibers to the high molecular weight chitosan collodion, with the remark that the variation of CNF content is not significantly affecting toughness. to conclude, The best mechanical properties were achieved at combining low molecular weight from r50 with CNF at content 0.4 % (w/w) with high molecular weight chitosan, when using collodions containing a total chitosan percentage of 4 % (w/w). This composition also corresponds to the highest achieved values of crystallinity index (CrI) and Herman’s orientation factor (fH) as illustrated in

Figure 7. It can be concluded that the crystallization, molecular mobility and shearing associated with the addition of low molecular weight chitosan of intermediate Mw, leads to an improvement of the fiber mechanical properties. It demonstrates the major role of introducing low molecular weight chitosan of intermediate Mw and cellulose nanofibers into chitosan collodions, to combine enhancement of crystallization and crystallites orientation in spinning process for the development of high strength fibers.

4. Discussion

Chitosan-based fibers with enhanced mechanical functionality were developed by incorporating small amounts of nanofibrillated cellulose (CNF) into a viscous chitosan (CHI) collodion solution of both high and low molecular weight chitosans in a gel spinning process. This approach resulted in anisotropic, nanofiber-reinforced biocomposite fibers with superior mechanical properties. The inclusion of CNFs in the CHI matrix plays a crucial role in shaping the morphological, thermal, and mechanical characteristics of the spun composite fibers. The CNFs significantly enhanced the stiffness, tensile strength, ductility, and toughness of the CHI-based fibers, owing to the remarkable mechanical properties, high aspect ratio, and strong compatibility of the cellulose nanofiber reinforcement with chitosan. This led to robust interfacial bonding between the components, involving both physical and covalent interactions.

Additionally, it was found that the mechanical and structural properties of these fibers are heavily influenced by the proportion of chitosan short chains (LMW) in the dope. As the chitosan short-chain content increases, the viscosity of the dope decreases, potentially facilitating the spinning process of collodions with higher polymer concentrations. Results from X-ray diffraction analysis show that the addition of LMW chitosan of intermediate Mw around 4.4 x 104 g/mol produced the highest increase of crystallinity index (CrI) and orientation in the fibers, yielding to the best mechanical performance.

Funding

Funding by the Emmy Noether Programme of the German Research Foundation DFG (Grant number: OS 497/6-1, AOBJ: 660891), the Priority Programme SPP 2416 “CodeChi” of the German Research Foundation DFG (Grant number: OS 497/7-1), and the Walter Benjamin Programme of the German Research Foundation DFG (Grant number: KA 6604/2-1, AOBJ: 708768). Funding by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the University of Bayreuth.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Emmy Noether Programme of the German Research Foundation DFG (Grant number: OS 497/6-1, AOBJ: 660891), the Priority Programme SPP 2416 “CodeChi” of the German Research Foundation DFG (Grant number: OS 497/7-1), and the Walter Benjamin Programme of the German Research Foundation DFG (Grant number: KA 6604/2-1, AOBJ: 708768) for funding. We thank Laurent David and Ruben Vera for fruitful discussion, X-ray scattering experiments at the Centre of Diffraction of University Claude Bernard Lyon 1, France and at D2AM/BM2 synchrotron beamline at the ESRF-Grenoble, France, as well as for their support with data modelling. We thank Agnès Crépet and the efforts of the Plateforme de Chromatographie ICL—IMP, France and Andreas Warmbold for technical assistance. We thank Shaghayegh Jahangir for support with format design. We also acknowledge funding by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the University of Bayreuth.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gorzelanny, C.; Pöppelmann, B.; Pappelbaum, K.; Moerschbacher, B.M.; Schneider, S.W. Human macrophage activation triggered by chitotriosidase-mediated chitin and chitosan degradation. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8556–8563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.B.; Sharma, C.P. Use of chitosan as a biomaterial: Studies on its safety and hemostatic potential. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1997, 34, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.K.; Ray, A.R. Biomedical Applications of Chitin, Chitosan, and Their Derivatives. J. Macromol. Sci. Part C: Polym. Rev. 2000, 40, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatelet, C.; Damour, O.; Domard, A. Influence of the Degree of Acetylation on Some Biological Properties of Chitosan Films. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abushammala, H.; Pontes, J.F.; Gomes, G.H.; Osorio-Madrazo, A.; Thiré, R.M.; Pereira, F.V.; Laborie, M.-P.G. Swelling, viscoelastic, and anatomical studies on ionic liquid-swollen Norway spruce as a screening tool toward ionosolv pulping. Holzforschung 2015, 69, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Osorio-Madrazo, A.; Laborie, M.-P. Preparation of cellulose I nanowhiskers with a mildly acidic aqueous ionic liquid: reaction efficiency and whiskers attributes. Cellulose 2013, 20, 1829–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Mao, A. Osorio-Madrazo, M.-P. Laborie, Novel Preparation Route for Cellulose Nanowhiskers, Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society, American Chemical Society, 2013.

- Tamo, A.K.; Doench, I.; Deffo, G.; Jiokeng, S.L.Z.; Doungmo, G.; Fotsop, C.G.; Temgoua, R.C.T.; Montembault, A.; Serghei, A.; Njanja, E.; et al. Lignocellulosic biomass and its main structural polymers as sustainable materials for (bio)sensing applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 24185–24253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-B.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-H. Low molecular weight chitosan prepared with the aid of cellulase, lysozyme and chitinase: Characterisation and antibacterial activity. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, V.E.; Stepnova, E.A.; Babak, V.G.; Yamskov, I.A.; Palma-Guerrero, J.; Jansson, H.-B.; Lopez-Llorca, L.V.; Salinas, J.; Gerasimenko, D.V.; Avdienko, I.D.; et al. Bactericidal and antifungal activities of a low molecular weight chitosan and its N-/2(3)-(dodec-2-enyl)succinoyl/-derivatives. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 64, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samyn, P.; Osorio-Madrazo, A. Native Crystalline Polysaccharide Nanofibers: Processing and Properties, in: A. Barhoum, M. Bechelany, A.S.H. Makhlouf (Eds.), Handbook of Nanofibers, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019, pp. 287–321.

- Notin, L.; Viton, C.; David, L.; Alcouffe, P.; Rochas, C.; Domard, A. Morphology and mechanical properties of chitosan fibers obtained by gel-spinning: Influence of the dry-jet-stretching step and ageing. Acta Biomater. 2006, 2, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamo, A.K.; Doench, I.; Walter, L.; Montembault, A.; Sudre, G.; David, L.; Morales-Helguera, A.; Selig, M.; Rolauffs, B.; Bernstein, A.; et al. Development of Bioinspired Functional Chitosan/Cellulose Nanofiber 3D Hydrogel Constructs by 3D Printing for Application in the Engineering of Mechanically Demanding Tissues. Polymers 2021, 13, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamo, A.K.; Doench, I.; Roshanbinfar, K.; Montembault, A.; Serghei, A.; Engel, F.B.; Osorio-Madrazo, A. Electrically conductive biopolymer-based hydrogels and fibrous materials fabricated using 3D printing and electrospinning for cardiac tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 51, 650–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamo, A.K.; Tran, T.A.; Doench, I.; Jahangir, S.; Lall, A.; David, L.; Peniche-Covas, C.; Walther, A.; Osorio-Madrazo, A. 3D Printing of Cellulase-Laden Cellulose Nanofiber/Chitosan Hydrogel Composites: Towards Tissue Engineering Functional Biomaterials with Enzyme-Mediated Biodegradation. Materials 2022, 15, 6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwieger, J.; Kakuan, N.; Osorio-Madrazo, A.; Lenarz, T.; Scheper, V. Neuritenregeneration primärer auditorischer Neurone in Hydrogelen. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie 2019, 98, 11232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Palubitzki, L.; Wang, Y.; Hoffmann, S.; Vidal-Y-Sy, S.; Zobiak, B.; Failla, A.V.; Schmage, P.; John, A.; Osorio-Madrazo, A.; Bauer, A.T.; et al. Differences of the tumour cell glycocalyx affect binding of capsaicin-loaded chitosan nanocapsules. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notin, L.; Viton, C.; Lucas, J.; Domard, A. Pseudo-dry-spinning of chitosan. Acta Biomater. 2006, 2, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Khalil, H.P.S.; Saurabh, C.K.; Adnan, A.S.; Nurul Fazita, M.R.; Syakir, M.I.; Davoudpour, Y.; Rafatullah, M.; Abdullah, C.K.; Haafiz, M.K.M.; Dungani, R. A review on chitosan-cellulose blends and nanocellulose reinforced chitosan biocomposites: Properties and their applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 150, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, S.; Montembault, A.; Fumagalli, M.; Osorio-Madrazo, A.; David, L. Controlled Polyelectrolyte Association of Chitosan and Carboxylated Nano-Fibrillated Cellulose by Desalting. Polymers 2021, 13, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peniche Agüero, H.; David, L.; Peniche Covas, C.; Osorio-Madrazo, A. Bioinspired chitosan-BSA fifibres for applications in intervertebral disc annulus fifibrosus tissue engineering. Rev. Cuba. Investig. Biomédicas 2017, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Peniche, H.; Razonado, I.A.; Alcouffe, P.; Sudre, G.; Peniche, C.; Osorio-Madrazo, A.; David, L. Wet-Spun Chitosan–Sodium Caseinate Fibers for Biomedicine: From Spinning Process to Physical Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toeri, J.; Osorio-Madrazo, A.; Laborie, M.-P. Preparation and Chemical/Microstructural Characterization of Azacrown Ether-Crosslinked Chitosan Films. Materials 2017, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lossada, F.; Jiao, D.; Guo, J.; Hoenders, D.; Eckert, A.; Walther, A. Outstanding Synergies in Mechanical Properties of Bioinspired Cellulose Nanofibril Nanocomposites using Self-Cross-Linking Polyurethanes. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 3334–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Farnood, R.; O’kElly, K.; Chen, B. Mechanical behavior of transparent nanofibrillar cellulose–chitosan nanocomposite films in dry and wet conditions. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 32, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.K.; Chung, M.J.; Choi, H.N.; Park, Y.I. Effects of the Molecular Weight and the Degree of Deacetylation of Chitosan Oligosaccharides on Antitumor Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N.A. Qinna, Q.G. Karwi, N. Al-Jbour, M.A. Al-Remawi, T.M. Alhussainy, Al-So, #039, K.A. ud, M.M.H.A. Omari, A.A. Badwan, Influence of Molecular Weight and Degree of Deacetylation of Low Molecular Weight Chitosan on the Bioactivity of Oral Insulin Preparations. Marine Drugs 2015, 13, 1710–1725.

- Bentley, F.E.; Passieux, R.; David, L.; Osorio-Madrazo, A. Pure Chitosan Biomedical Textile Fibers from Mixtures of Low- and High-Molecular Weight Bidisperse Polymer Solutions: Processing and Understanding of Microstructure–Mechanical Properties’ Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Y.; Yuguang, D.; Junzeng, Z. Low Molecular Weight and Oligomeric Chitosans and Their Bioactivities. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2009, 9, 1546–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.N.V.R. Chitin and chitosan fibres: A review. Bull. Mater. Sci. 1999, 22, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudin, V.E.; Dobrovolskaya, I.P.; Neelov, I.M.; Dresvyanina, E.N.; Popryadukhin, P.V.; Ivan’kOva, E.M.; Elokhovskii, V.Y.; Kasatkin, I.A.; Okrugin, B.M.; Morganti, P. Wet spinning of fibers made of chitosan and chitin nanofibrils. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 108, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Bravo, S.; Doench, I.; Molina, P.; Bentley, F.E.; Tamo, A.K.; Passieux, R.; Lossada, F.; David, L.; Osorio-Madrazo, A. Functional Bionanocomposite Fibers of Chitosan Filled with Cellulose Nanofibers Obtained by Gel Spinning. Polymers 2021, 13, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.; Chornet, E.; Rodrigue, D. STEADY-SHEAR RHEOLOGY OF CONCENTRATED CHITOSAN SOLUTIONS. J. Texture Stud. 2004, 35, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, D.P.; Inamdar, M.S. Aqueous Behaviour of Chitosan. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2010, 2010, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.L.; Smith, A.F. X-ray Diffraction Studies of Chitin, Chitosan, and Derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. 1936, 40, 863–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Madrazo, A.; Eder, M.; Rueggeberg, M.; Pandey, J.K.; Harrington, M.J.; Nishiyama, Y.; Putaux, J.-L.; Rochas, C.; Burgert, I. Reorientation of Cellulose Nanowhiskers in Agarose Hydrogels under Tensile Loading. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Madrazo, P. Fratzl, L. David, G. Urban, A. Montembault, A. Crepet, C. Gorzelanny, C. Mochales-Palau, L. Heux, J.-L. Putaux, T. Cachon, E. Viguier, C. Peniche, G. Sudre, Y. Politi, Hydrogel nanocomposite biomaterials for intervertebral disc tissue engineering. Preparation, characterization and application. BioNanoMaterials 2015, 16, 239–258.

- Morcos, L. David, G. Sudre, V. Mai, T.A. Tran, A. Osorio-Madrazo, E.-J. Courtial, P. Bruyère, C. Boulocher, R. Rieger, Structural anisotropy characterization of fiber-reinforced hydrogels scaffolds during extrusion-based 3D printing for soft tissue repair, European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (2024).

- Osorio-Madrazo, L. David, A. Montembault, E. Viguier, T. Cachon, Hydrogel Composites Comprising Chitosan and Cellulose Nanofibers. International Patent Ap-plication No. WO 2019/175279 A1, 19 September 2019, US Patent Application 16/980383, 18 February 2021., 2021.

- Osorio-Madrazo, M.-P. Laborie, Morphological and Thermal Investigations of Cellulosic Bionanocomposites, in: A. Dufresne, S. Thomas, L. Pothen (Eds.), Biopolymer Nanocomposites, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken (New Jersey), 2013, pp. 411–436.

- P. Samyn, P. Billen, D. Vandamme, P. Adriaensens, Y. Politi, A. Osorio-Madrazo, Raman spectroscopy and imaging in organization, processing and functionalization of polysaccharide materials, (2020).

- Osorio-Madrazo, A.; David, L.; Trombotto, S.; Lucas, J.-M.; Peniche-Covas, C.; Domard, A. Kinetics Study of the Solid-State Acid Hydrolysis of Chitosan: Evolution of the Crystallinity and Macromolecular Structure. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Geng, L.; Chen, S.; Shi, S.; Hsiao, B.S.; Peng, X. Hierarchical Assembly of Nanocellulose into Filaments by Flow-Assisted Alignment and Interfacial Complexation: Conquering the Conflicts between Strength and Toughness. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 32090–32098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, P.H.; Hermans, J.J.; Vermaas, D.; Weidinger, A. Deformation mechanism of cellulose gels. III. Changes in orientation upon drying. J. Polym. Sci. 1947, 2, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, A.; Tamo, A.K.; Doench, I.; David, L.; de Oliveira, P.N.; Gorzelanny, C.; Osorio-Madrazo, A. Nanoparticles and Colloidal Hydrogels of Chitosan–Caseinate Polyelectrolyte Complexes for Drug-Controlled Release Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaul, J.Z.; Hudson, S.M.; Creber, K.A.M. Improved mechanical properties of chitosan fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 72, 1721–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Silva, D.A.; Rivero, S.; Pinotti, A. Chitosan-based nanocomposite matrices: Development and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Qi, C. Preparation of a Novel Chitosan Based Biopolymer Dye and Application in Wood Dyeing. Polymers 2016, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Cao, S.; Luo, X.; Liu, K. Novel antimicrobial chitosan–cellulose composite films bioconjugated with silver nanoparticles. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 70, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Lu, L.; Xu, Q. Morphological and Thermal Investigations of Chitin--Based Nanocomposites, Biopolymer Nanocomposites: Processing, Properties, and Applications (2013) 83-110.

- Poyraz, B.; Tozluoğlu, A.; Candan, Z.; Demir, A. Matrix impact on the mechanical, thermal and electrical properties of microfluidized nanofibrillated cellulose composites. J. Polym. Eng. 2017, 37, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.C.; Freire, C.S.; Silvestre, A.J.; Neto, C.P.; Gandini, A.; Berglund, L.A.; Salmén, L. Transparent chitosan films reinforced with a high content of nanofibrillated cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohuriaan, M.; Shokrolahi, F. Thermal studies on natural and modified gums. Polym. Test. 2004, 23, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaul, J.; Hooper, M.; Chanyi, C.; Creber, K.A.M. Improvements in the drying process for wet-spun chitosan fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1998, 69, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, A.; Odani, H.; Nakajima, A. Determination of degree of deacetylation of chitosan by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Polym. Bull. 1991, 26, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pääkkö, M.; Ankerfors, M.; Kosonen, H.; Nykänen, A.; Ahola, S.; Österberg, M.; Ruokolainen, J.; Laine, J.; Larsson, P.T.; Ikkala, O.; et al. Enzymatic Hydrolysis Combined with Mechanical Shearing and High-Pressure Homogenization for Nanoscale Cellulose Fibrils and Strong Gels. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1934–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Madrazo, A.; David, L.; Trombotto, S.; Lucas, J.-M.; Peniche-Covas, C.; Domard, A. Highly crystalline chitosan produced by multi-steps acid hydrolysis in the solid-state. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 1730–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doench, I.; Tran, T.A.; David, L.; Montembault, A.; Viguier, E.; Gorzelanny, C.; Sudre, G.; Cachon, T.; Louback-Mohamed, M.; Horbelt, N.; et al. Cellulose Nanofiber-Reinforced Chitosan Hydrogel Composites for Intervertebral Disc Tissue Repair. Biomimetics 2019, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F.; Iwata, T. Estimation of the Elastic Modulus of Cellulose Crystal by Molecular Mechanics Simulation. Cellulose 2006, 13, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, N.; Muñoz, J.; Ramírez, P.; Guerrero, A. Flow behaviour, linear viscoelasticity and surface properties of chitosan aqueous solutions. Food Hydrocoll. 2010, 24, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.M. Rheology of non-Newtonian fluids: A new flow equation for pseudoplastic systems. J. Colloid Sci. 1965, 20, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doench, I.; Torres-Ramos, M.E.W.; Montembault, A.; de Oliveira, P.N.; Halimi, C.; Viguier, E.; Heux, L.; Siadous, R.; Thiré, R.M.S.M.; Osorio-Madrazo, A. Injectable and Gellable Chitosan Formulations Filled with Cellulose Nanofibers for Intervertebral Disc Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2018, 10, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimi, C.; Montembault, A.; Guerry, A.; Delair, T.; Viguier, E.; Fulchiron, R.; David, L. Chitosan solutions as injectable systems for dermal filler applications: Rheological characterization and biological evidence. 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 2596–2599.

- Osorio-Madrazo, A.; David, L.; Peniche-Covas, C.; Rochas, C.; Putaux, J.-L.; Trombotto, S.; Alcouffe, P.; Domard, A. Fine microstructure of processed chitosan nanofibril networks preserving directional packing and high molecular weight. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 131, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Flow diagrams show the evolution of the viscosity (η) vs shear rate (γ) of: a) HMW chitosan with LMW chitosan (“oligomers”) produced for ratio r=20 or r=50, and CHI reference solution b) CNF-filled CHI/LMWr20 suspensions and CHI reference solution c) b) CNF-filled CHI/LMWr50 suspensions and CHI reference solution. (Bottom) Examples of modeling of flow diagrams with Carreau-Yasuda law (Equation (1)).

Figure 1.

Flow diagrams show the evolution of the viscosity (η) vs shear rate (γ) of: a) HMW chitosan with LMW chitosan (“oligomers”) produced for ratio r=20 or r=50, and CHI reference solution b) CNF-filled CHI/LMWr20 suspensions and CHI reference solution c) b) CNF-filled CHI/LMWr50 suspensions and CHI reference solution. (Bottom) Examples of modeling of flow diagrams with Carreau-Yasuda law (Equation (1)).

Figure 2.

SEC/MALLS analysis of the colloidal dispersions: a) low (LMW) and high molecular weight (HMW) chitosan weight distribution; b) chitosan molecular weight distribution in the processed spun fibers containing low (LMW) and high molecular weight (HMW) chitosan. The curves in b) are deconvoluted using the two Gaussian (Gauss HMw-CHI for HMW chitosan, and Gauss LMw-CHI for LMW chitosan), with a sum (ΣGauss) that coindides with the experimental curve of SEC chromatogram.

Figure 2.

SEC/MALLS analysis of the colloidal dispersions: a) low (LMW) and high molecular weight (HMW) chitosan weight distribution; b) chitosan molecular weight distribution in the processed spun fibers containing low (LMW) and high molecular weight (HMW) chitosan. The curves in b) are deconvoluted using the two Gaussian (Gauss HMw-CHI for HMW chitosan, and Gauss LMw-CHI for LMW chitosan), with a sum (ΣGauss) that coindides with the experimental curve of SEC chromatogram.

Figure 3.

ATR-FTIR spectra of spun composite fibers consisting of high molecular weight chitosan (HMW), low molecular weight chitosan (LMW) as obtained using different molar ratios of glucosamine to NaNO2 (r20: red; r50: blue), and cellulose nanofibers (CNF) at different contents: a) 0.3; b) 0.4 and c) 0.5%; as well as CHI) the reference spectrum of the pure high molecular weight chitosan fibers (HMW).

Figure 3.

ATR-FTIR spectra of spun composite fibers consisting of high molecular weight chitosan (HMW), low molecular weight chitosan (LMW) as obtained using different molar ratios of glucosamine to NaNO2 (r20: red; r50: blue), and cellulose nanofibers (CNF) at different contents: a) 0.3; b) 0.4 and c) 0.5%; as well as CHI) the reference spectrum of the pure high molecular weight chitosan fibers (HMW).

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of the lateral (top) and fracture cross-section (bottom) surface of the spun HMW/LMW/CNF composite fibers of: (a,f) CHI/r20/CNF0.3; (b,g) CHI/r20/CNF0.4; (c,h) CHI/r50/CNF0.4; (d,i) CHI/r20/CNF0.5 and (e,j) CHI/r50/CNF0.5. Scale bars lateral surface 20µm and scale bars fracture cross-section surface 2 µm. k) Histogram showing the mean fiber diameter obtained with the different HMW/LMW/CNF collodion formulations (F1-F12, see

Table 1).

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of the lateral (top) and fracture cross-section (bottom) surface of the spun HMW/LMW/CNF composite fibers of: (a,f) CHI/r20/CNF0.3; (b,g) CHI/r20/CNF0.4; (c,h) CHI/r50/CNF0.4; (d,i) CHI/r20/CNF0.5 and (e,j) CHI/r50/CNF0.5. Scale bars lateral surface 20µm and scale bars fracture cross-section surface 2 µm. k) Histogram showing the mean fiber diameter obtained with the different HMW/LMW/CNF collodion formulations (F1-F12, see

Table 1).

Figure 5.

TEM micrographs of ultrathin section of spun hybrid fiber produced from formulation F7 (CHI/r50/CNF0.4), which consists of low molecular weight chitosan (for r50) at 0.6 % (w/w), cellulose nanofiber content 0.4% (w/w), and high molecular weight chitosan at 3.4 % (w/w). (Top-left) Fiber cut parallel to the fiber axis. (Top-right) Fiber cut perpendicular to the fiber axis (cross-section). (Bottom-left) Higher magnification for fiber cut parallel to the fiber axis. (Bottom-right) Higher magnification for fiber cut perpendicular to the fiber axis (cross-section).

Figure 5.

TEM micrographs of ultrathin section of spun hybrid fiber produced from formulation F7 (CHI/r50/CNF0.4), which consists of low molecular weight chitosan (for r50) at 0.6 % (w/w), cellulose nanofiber content 0.4% (w/w), and high molecular weight chitosan at 3.4 % (w/w). (Top-left) Fiber cut parallel to the fiber axis. (Top-right) Fiber cut perpendicular to the fiber axis (cross-section). (Bottom-left) Higher magnification for fiber cut parallel to the fiber axis. (Bottom-right) Higher magnification for fiber cut perpendicular to the fiber axis (cross-section).

Figure 6.

(Top) Two-dimensional wide-angle X-ray scattering (2D-WAXS) images of the spun CHI/OLIG/CNF fibers of (a) CHI/r20/CNF0.3, (b) CHI/r20/CNF0.4, (c) CHI/r50/CNF0.4 and (d) CHI/r20/CNF0.5 with fiber axis tilted by -45º from the vertical position. (Bottom) (e) Radial average over the 360 azimuth of the above 2D-WAXS images of spun fibers of varied CHI/OLIG/CNF formulations. (f) Procedures for the calculation of crystallinity indexes from WAXS diffraction patterns of the fibers. (fII) Diffraction diagram of the original CHI/r50/CNF0.4 fiber. (fII) Diffraction diagram of the amorphous chitosan sample. (fIII) Estimated crystalline contribution of CHI/r50/CNF0.4 fiber after subtraction of the area of the amorphous diffractogram II.

Figure 6.

(Top) Two-dimensional wide-angle X-ray scattering (2D-WAXS) images of the spun CHI/OLIG/CNF fibers of (a) CHI/r20/CNF0.3, (b) CHI/r20/CNF0.4, (c) CHI/r50/CNF0.4 and (d) CHI/r20/CNF0.5 with fiber axis tilted by -45º from the vertical position. (Bottom) (e) Radial average over the 360 azimuth of the above 2D-WAXS images of spun fibers of varied CHI/OLIG/CNF formulations. (f) Procedures for the calculation of crystallinity indexes from WAXS diffraction patterns of the fibers. (fII) Diffraction diagram of the original CHI/r50/CNF0.4 fiber. (fII) Diffraction diagram of the amorphous chitosan sample. (fIII) Estimated crystalline contribution of CHI/r50/CNF0.4 fiber after subtraction of the area of the amorphous diffractogram II.

Figure 7.

a) Crystallinity index (CrI) and b) Herman’s orientation factor (fH) values of spun fibers obtained for different formulations containing high (HMW) and low molecular chitosans (LMW, with used ratio of glucosamine to NaNO2 of: r20 or r50), and cellulose nanofibers (CNF). (Bottom) Schematics summarizing the transition from isotropic collodions to anisotropic spun fibers, involving formation and orientation of crystalline materials due to shearing and molecular mobility during extrusion, stretching and drying in spinning of chitosan/cellulose nanofiber hybrid fibers.

Figure 7.

a) Crystallinity index (CrI) and b) Herman’s orientation factor (fH) values of spun fibers obtained for different formulations containing high (HMW) and low molecular chitosans (LMW, with used ratio of glucosamine to NaNO2 of: r20 or r50), and cellulose nanofibers (CNF). (Bottom) Schematics summarizing the transition from isotropic collodions to anisotropic spun fibers, involving formation and orientation of crystalline materials due to shearing and molecular mobility during extrusion, stretching and drying in spinning of chitosan/cellulose nanofiber hybrid fibers.

Figure 8.

(a) Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and (b) derivative thermogravimetry (DTG).

Figure 8.

(a) Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and (b) derivative thermogravimetry (DTG).

Figure 9.

Tensile mechanical properties of spun CHI/LMW/CNF fibers obtained for different formulations. (a) Nominal stress–strain curves. Evolution of: (b) Young’s modulus E and toughness Ut, (c) the stress (σy) and strain (εy) values at the yield point, (d) the stress-at-break (σb) and strain-at-break (εb), with the increase of CNF content in spun fibers.

Figure 9.

Tensile mechanical properties of spun CHI/LMW/CNF fibers obtained for different formulations. (a) Nominal stress–strain curves. Evolution of: (b) Young’s modulus E and toughness Ut, (c) the stress (σy) and strain (εy) values at the yield point, (d) the stress-at-break (σb) and strain-at-break (εb), with the increase of CNF content in spun fibers.

Table 2.

Flow parameters determined from the fitting of the viscosity vs. shear rate curves of different chitosan/cellulose nanofiber collodions also containing low molecular weight chitosans r20 or r50 (

Figure 1), by using the Carreau-Yasuda (Equation (2)).

Table 2.

Flow parameters determined from the fitting of the viscosity vs. shear rate curves of different chitosan/cellulose nanofiber collodions also containing low molecular weight chitosans r20 or r50 (

Figure 1), by using the Carreau-Yasuda (Equation (2)).

| Formulation |

Log10(η0/mPa.s) |

τ (s) |

p |

β |

| F1) CHI/r20 |

5.9448 |

1.8582 |

0.7408 |

1.1043 |

| F2) CHI/r20/0.3CNF |

6.0558 |

2.3068 |

0.6299 |

1.2686 |

| F3) CHI/r20/0.4CNF |

6.0459 |

2.5849 |

0.5926 |

1.3280 |

| F4) CHI/r20/0.5CNF |

6.0878 |

2.9427 |

0.6281 |

1.2493 |

| F5) CHI/r50 |

5.9867 |

2.0874 |

0.6140 |

1.2932 |

| F6) CHI/r50/0.3CNF |

6.0926 |

2.7594 |

0.4994 |

1.6075 |

| F7) CHI/r50/0.4CNF |

6.3558 |

0.8584 |

1.4199 |

0.8217 |

| F8) CHI/r50/0.5CNF |

6.5297 |

1.5515 |

1.2003 |

0.8862 |

| F9) CHI |

6.0229 |

1.4948 |

0.7200 |

1.1963 |

Table 2.

Molecular weight and polydispersity index of CHI formulations.

Table 2.

Molecular weight and polydispersity index of CHI formulations.

| |

Formulation |

Chitosan Mw (g/mol) |

Chitosan polydispersity index Đ |

| F1) |

CHIr20 |

29340 (±0.63%) |

1.3 (±1.33%) |

| F2) |

CHI/r20/0.3CNF |

378100 (±0.91%) |

2.8 (±1.35%) |

| F3) |

CHI/r20/0.4CNF |

243600 (±0.62%) |

2.3 (±1.02%) |

| F4) |

CHI/r20/0.5CNF |

284100 (±0.69%) |

2.4 (±0.91%) |

| F5) |

CHIr50 |

43840 (±0.49%) |

1.5 (±0.89%) |

| F6) |

CHI/r50/0.3CNF |

365500 (±0.98%) |

2.8 (±1.37%) |

| F7) |

CHI/r50/0.4CNF |

427100 (±1.03%) |

2.7 (±1.65%) |

| F8) |

CHI/r50/0.5CNF |

434600 (±1.04%) |

2.7 (±1.79%) |

| F9) |

CHI |

554000 (±1.06%) |

1.6 (±1.59%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).