1. Introduction

Fuel cell based electric generators are emerging as a clean, quiet and modular light-weight alternative to power supply options such as diesel gensets and battery banks [

1]. Hydrogen Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFC) and deliver electricity on demand with zero local NOx, SOx or particulate emissions, while emitting only water [

2]. In contrast, diesel generators require exhaust handling, fuel storage, frequent maintenance and ventilation; and large battery-only solutions can be heavy, space-intensive and limited by autonomy. Properly engineered PEMFC systems combine a continuous fuel supply with a right-sized battery buffer for peaks and seamless black-start, providing long-duration, low-maintenance backup and off-grid power. The key advantages of fuel cell generators, when compared to fossil fuel-powered gensets and large battery banks, can be summarized as follows:

Zero emissions and indoor-friendliness than diesel-based generators;

Higher efficiency, scalable runtime with instant start;

Lower noise and reduced thermal signature than diesel-based generators, improving suitability for various applications;

Modular and portable rack.

Hydrogen fuel cells by electrochemical reactions convert hydrogen to electricity and heat, offering high energy density and efficiency. The efficiency of diesel-based generators is 40% whereas for hydrogen fuel cell generators typical efficiency is around 40-55% [

3]. As the technology advancement in the field of material development for catalyst, flow-fields, gas diffusion layer, membrane, etc. and design of flow-field, end plates, and fuel cell stack assembly contributes for the enhancement of fuel cell stack used especially in power generator applications. For higher power fuel cell-based generators improved manufacturing techniques, operational procedures, diagnostics [

4], water management, and thermal management contribute to higher performance, efficiency, cost, and longevity of the stack and its components [

5]. Further, the control techniques used for the hydrogen generators [

6,

7,

8] are difficult other than stacking the fuel cells [

6,

7,

8].

Therefore, an appropriate selection and integration of balance-of-plant components, such as fans, air filters, valves, pressure regulators, and sensors, are crucial to ensure the efficient functioning of both the fuel cell stack and the generator system.

With the increasing fuel cell-based power generation devices, especially power generators Ghenai et al. [

9] developed fuel cell generators for ferry systems. Recently, Ghimire et al. [

10] has done techno-economic assessment of fuel cell generators in hospitals in Nepal. Additionally, Inal et al. [

11] conducted a case study for hydrogen based electric power generators for maritime applications highlighting the effect on reduction in emission gases, while comparing capital and operational expenditure for fuel cell systems. A very important Lolland hydrogen community where hydrogen CHP systems were installed for residential use of power rating 2-6.5 kW [

12]. Another project, Calistoga Resiliency Center (California, USA), replaces noisy diesel generators for emergency backup during wildfire-related public safety power shutoffs [

13]. Some of the key notable projects for hydrogen fuel cell power generators are:

The project FC powered RBS has been to carry out a set of field trials to demonstrate the industrial readiness and market appeal of power generation systems based on Fuel Cell technology of power re-quirement 2.5-5kW [

14];

Emergency communication system station in Iceland deployed by GenCell Ltd. in 2021 with power rating of 4kW [

15];

In 2023, NATO’s Energy Security Centre of Excellence (ENSEC CoE) conducted field experiments with the French Armed Forces, deploying hydrogen fuel cells ranging from 400 W to 1 kW [

16].

The deployment of fuel cell generators across various applications and major projects highlights the significance of these power systems and their potential for the future.

Although much research has been done for fuel cell stacks and systems of various power requirements and applications [

3,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], the Current literature review focuses and presents the recent current technological review, market, and comparative landscape for fuel cell generators for a small to a medium power rating 200W to 6kW fuel cell-based generators.

2. Market Segments for Fuel Cell-Based Power Generators

With their higher efficiency, modular and portable design, and stealth operation, fuel cell-based power generators offer valuable solutions across multiple segments, including:

Bulleted lists look like this:

Telecommunications sector where the fuel cell-based power generators can be used as base-station backup and power autonomy;

Defense and security: Due to minimum noise and vibrations, unlike diesel generators these fuel cell generators can be useful for tactical operations;

Construction and utilities where such fuel cell generators are useful as secondary power sources;

Shelters and civil protection: During disaster and calamity situations such as storms, tornadoes, wars etc. fuel cell generators can be used to supply power to these locations;

Healthcare, pharmacies and clinics where fuel cell power generators can be used as primary or secondary sources for hospitals, cold-storage, medicine storage, etc.;

Remote sites and research facilities: The modular fuel cell generator systems can be used to provide power supplies to remote sites.

2.1. Indoor Use

The fuel cell utilizes hydrogen and oxygen gases for electrochemical reactions and generate heat, water, and electricity. Electrochemical reactions do not produce carbon monoxide, NOx and soot typically formed in combustion engines. Therefore, these hydrogen fuel cell generator units can be installed for indoor use, with proper hydrogen safety codes/standards [

22]. The hydrogen safety includes provision for ventilation, leak detection, safe cylinder storage, and appropriate electrical identification/classification. For example, standards and codes such as NFPA 2 (Hydrogen Technologies Code) and IEC 62282-3-100 covers details such as sitting, ventilation, gas detection, purging and electrical safety. In practice, modern fuel cell cabinets and racks integrate forced ventilation, H2 sensors, automatic shut-off valves and online cloud monitoring. Compared to diesel generators, which require dedicated exhaust systems and fire rated generator rooms, fuel cells generators can often be placed indoors with proper safety compliance [

23].

2.2. Defense and Security

Fuel-cell generators provide a tactical advantage in modern defense operations. Unlike diesel generators, which produce high infrared emissions detectable by drones with thermal cameras, hydrogen fuel cells operate at much lower external surface temperatures. This significantly reduces their visibility to adversarial targeting systems [

24].

Moreover, combustion generators radiate substantial heat and acoustic noise, creating visible infrared and audible signatures. Hydrogen fuel cells operate quietly and at lower external temperatures, reducing detection risk for thermal imagers and enabling. These attributes have been highlighted by defense R&D programs and field experiments and align lessons from recent conflicts where thermal sensors on unmanned systems can strikes on hot and noisy targets. The war in Ukraine has highlighted the vulnerability of conventional generators, as drones equipped with thermal sensors have a higher possibility of targeting high temperature generators running on fossil fuels. In addition to reduced IR signatures, fuel cells also produce near-silent operation, eliminating acoustic cues that adversaries could exploit. This makes them ideal for silent watch missions, mobile command centers, and covert forward operating bases where stealth is critical. Ongoing NATO and national defense trials confirm these advantages, with hydrogen FCs demonstrating improved survivability and mission endurance in contested environments.

2.3. Civil Protection

In shelters designed for civil protection-including bomb shelters, storm safe rooms, and underground bunkers, reliable power is critical to sustain lighting, communications, ventilation, and medical equipment. Diesel generators, though widely used, require dedicated exhaust ducts, fireproof enclosures, and outdoor fuel storage facilities that are difficult to implement in dense urban or underground structures.

Fuel cells, by contrast, produce only water vapor and low-grade heat, allowing them to be safely placed indoors when codes are followed. Their compact form and quiet operation make them ideal for retrofitting into civil defense shelters where space and air circulation are constrained. Furthermore, fuel cells do not add to indoor CO risks, a key safety factor in sealed environments. Governments in Europe and Asia are now exploring fuel-cell integration into municipal and community shelter programs to strengthen resilience against both natural disasters and security threats.

Storm and community safe rooms (ICC 500 / FEMA P-361) require reliable, long-duration emergency power to maintain lighting, communications and ventilation. Because diesel exhaust must be sent outdoors and fuel stored safely, sitting can be complex especially in retrofits. Compact fuel-cell racks with indoor H₂ bottles or outdoor cylinder banks can meet runtime requirements with minimal emissions and low noise, an advantage for sealed or densely occupied shelters.

2.4. Telecommunications Backup Power

Telecommunications is one of the largest and most mature market segments for hydrogen fuel cells. Mobile base stations, particularly in 5G networks, require uninterrupted power to maintain connectivity [

25]. Outages, even for a few minutes, can impact thousands of users and critical digital services.

Fuel cells extend backup runtimes provided by lithium-ion batteries, without requiring oversized battery banks that are costly and space-prohibitive. Hybrid fuel cell and battery solutions can autonomously power telecom towers for long periods of time, thanks to simple hydrogen cylinder replacement.

In countries like Japan, Sweden, Germany, and the United States, telecom operators are already piloting fuel-cell deployments as part of their climate and resiliency strategies. This aligns with net-zero targets and ensures grid-independent communication during blackouts, natural disasters, or cyber incidents. The ability to locally produce hydrogen via electrolysis further enhances operational resilience by reducing dependence on complex fuel logistics.

As networks densify and 5G loads rise, site power draws commonly range from ~3-7 kW and higher in urban areas. Fuel-cell and Li-ion battery hybrids extend autonomy beyond typical battery-only windows while preserving cabinet space and lowering maintenance. Hydrogen logistics (cylinder swaps or microbulk) provide predictable OPEX, and cloud monitoring simplifies fleet operations.

2.5. Pharmacies & Clinics

The healthcare sector relies heavily on reliable power supply, not only for medical devices but also for cold-chain pharmaceuticals such as vaccines and biologics [

26]. Even short blackouts can compromise temperature-sensitive medicines, leading to financial loss and patient risk. Beyond refrigeration, digitalization of healthcare workflows, e-prescriptions, insurance claims, and medical records - means that clinics and pharmacies cannot operate without uninterrupted IT infrastructure.

Hydrogen fuel-cell generators provide a safe, quiet, and emission-free backup solution that ensures continuous refrigeration, IT systems, and life-supporting devices. Unlike diesel, which requires outdoor installation and generates harmful emissions, fuel cells can be safely integrated indoors with proper ventilation. This allows clinics in urban centers or remote rural areas to secure resilient energy without the regulatory burdens of combustion-based generators. Fuel cells therefore represent a future-proof solution for decentralized healthcare resiliency, especially in regions facing aging grids and increasing blackout risks.

Vaccines and many biologics must be kept at 2-8 °C; prolonged outages force disposal and interrupt care [

27]. Moreover, pharmacy dispensing today depends on online prescriptions and real-time claims. Large-scale IT outages in 2024 in the United States showed that when digital rails go down, pharmacies experience backlogs and cannot process many prescriptions even if staff are on site. Fuel-cell UPS solutions keep refrigeration, IT racks, and point-of-sale online through multi-hour blackouts, ensuring continuity of operations.

2.6. Construction Market

The construction industry is another key market segment where hydrogen-based fuel cell generators can provide transformative advantages. On many sites, especially in the urban areas, connection to the local electrical grid is either unavailable or prohibitively slow and expensive. As a result, contractors often rely on diesel generators for temporary power. However, diesel use in construction is increasingly problematic due to both environmental and regulatory factors.

Diesel generators are noisy and polluting, creating difficulties in densely populated areas where residents and local authorities are sensitive to air quality and noise levels. Studies show that diesel generators contribute significant levels of particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen oxides, while also producing sound levels often exceeding 85 dB(A) - a threshold regulated by occupational health standards in many regions. Regulations are becoming stricter: for example, several European cities have limited construction site generator usage during nighttime hours, while in Australia fines for noise violations can exceed $1 million. India has enforced retrofitting requirements for diesel gensets in NCR cities due to their heavy contribution to urban air pollution, and Oslo has gone further by mandating that all municipal construction sites must use zero-emission machinery from 2025 onward.

Hydrogen fuel cell generators provide a compelling alternative. They are silent in operation, produce zero local emissions, and can be safely deployed within urban areas without triggering nuisance complaints or regulatory non-compliance. Their ability to operate without frequent refueling or exhaust infrastructure makes them particularly attractive for modern construction projects in cities striving to reach climate and air quality goals.

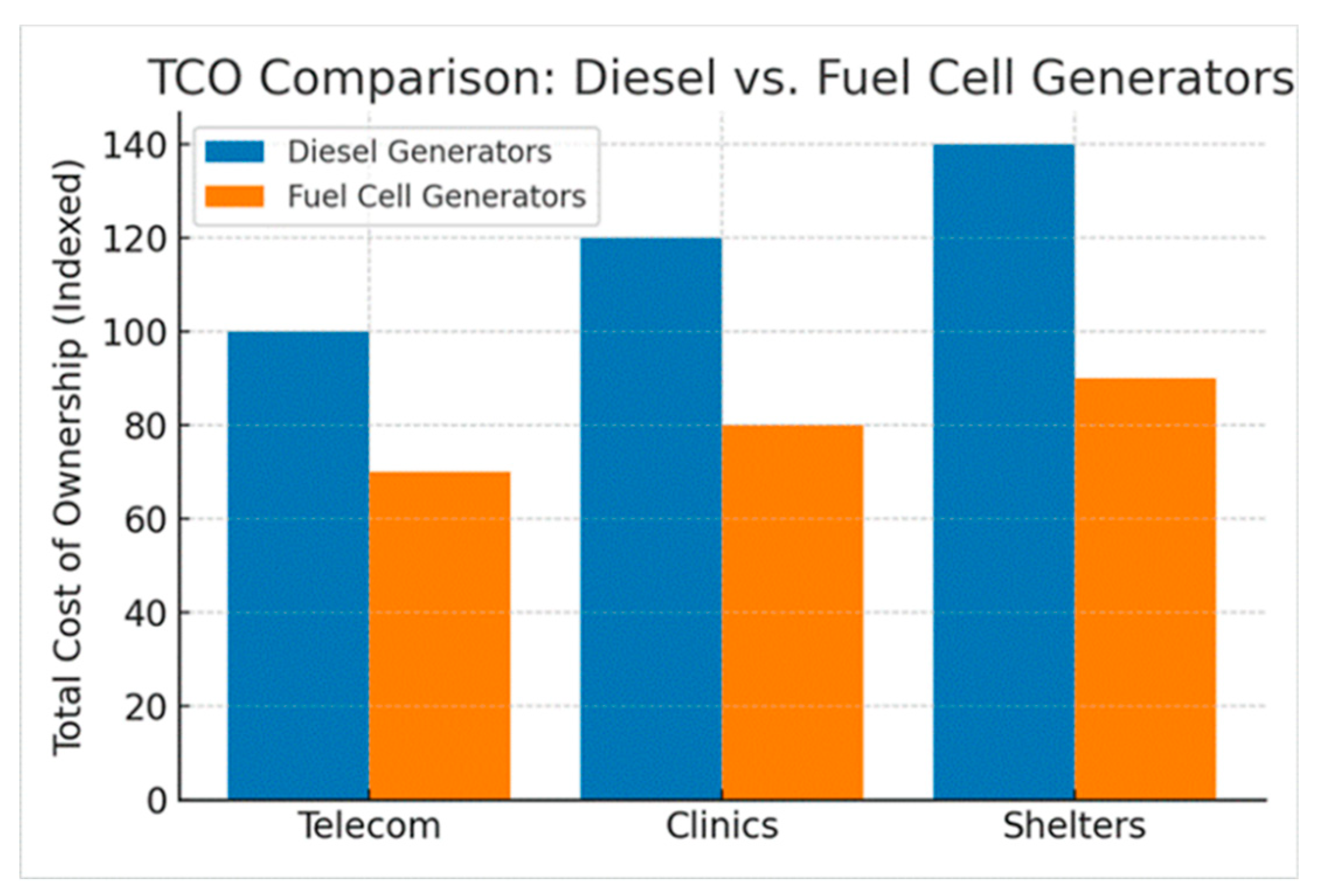

3. Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) Comparison

Figure 1 compares the TCO of diesel generators and hydrogen fuel cell generators across three typical duty cycles: telecommunications sites, healthcare clinics, and civil defense shelters. While diesel generators have traditionally dominated these markets, their TCO is higher due to fuel logistics, ventilation requirements, and intensive maintenance [

28]. Fuel cell generators, by contrast, reduce maintenance needs, eliminate costly exhaust infrastructure, and offer long-term savings especially where local hydrogen production is feasible. The comparison shows that fuel cell systems consistently provide a lower TCO profile across key market segments.

4. Company & Product Landscape for Hydrogen Generators with Power 200W to 6kW

PEM fuel cell generators, Direct Methanol Fuel Cells (DMFCs), and conventional propane and natural gas generators all serve the same purpose of providing distributed or backup power, but they operate very differently. PEM systems rely on hydrogen and achieve high electrical efficiencies - up to about 60% on pure hydrogen and around 40% when reforming hydrocarbons - while also starting quickly and following load changes smoothly. DMFCs, in contrast, offer easier fuel logistics since liquid methanol is simple to handle and store, though they typically operate at lower efficiencies in the 20-30% range and have slower transient performance. Propane and natural gas generators, based on internal combustion engines, are more widely available and generally inexpensive, delivering efficiencies of around 28-35% for small sets, but they depend on combustion, which inherently generates more heat, noise, and emissions.

However, these generator technologies vary significantly in their heat, acoustic signatures, and overall performance. PEM and DMFC units operate at low temperatures (around 80 °C), producing only low-grade waste heat and minimal infrared signatures, whereas propane and natural gas generators expel hot exhaust gases often exceeding 370-500 °C, making their thermal footprint much higher. Similarly, fuel cell systems are quiet, with typical hydrogen units operating at less than 45-65 dB, compared to the 80-90 dB levels common for small internal combustion generators. In terms of performance, PEM fuel cells provide fast start-up, efficient load following, and clean operation, while DMFCs trade efficiency for liquid fuel convenience. Propane and natural gas units, though less efficient and noisier, excel in availability and low upfront cost, making them practical for households or facilities with ready fuel supply.

4.1. PowerUP Energy Technologies

Figure 2 shows the PowerUP Energy Technologies of power rating of 6kW, the presented system also has integrated battery systems.

PowerUP offers portable generators (UP400, UP1K, UP3K) and rack systems (UPSystem 3K/6K) that pair PEM fuel cells with integrated batteries. UPSystem 6K delivers 6 kW continuous with 10 kW peak from the battery bank; typical H₂ consumption is ~65 g/kWh [

29]. Form factors suit indoor telecom shelters, clinics and mission-critical rooms; cloud/IoT monitoring and CAN/RS-485 are supported.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the PowerUP system of different power ratings.

4.2. SFC Energy (EFOY)

SFC EFOY Hydrogen Fuel Cell 2.5 kW modules can be combined in cabinets (e.g., X5.0) for 5 kW applications, as shown in

Figure 5. EFOY systems are widely used in remote power and telecom. Depending on the configuration, integrated buffer capacity may be limited, so external batteries are typically added for peak loads [

30].

4.3. GenCell

GenCell markets alkaline fuel cell (AFC) systems such as the GenCell BOX of power rating 5kW. The AFC can be effective for long duration backup, though the liquid electrolyte and CO2 sensitivity imply different maintenance and sitting considerations versus PEM systems.

4.4. Panasonic (KIBOU Pure-Hydrogen Fuel Cell)

Panasonic’s industrial KIBOU 5 kW PEFC is slightly above the 6kW scope when stacked, but the single 5 kW unit is a relevant benchmark. It features ~56% electrical efficiency at rated output and ~54 g/kWh H₂ consumption, with a compact 205 kg cabinet.

Figure 6.

Panasonic KIBOU 5 kW Pure-Hydrogen Fuel Cell [

32].

Figure 6.

Panasonic KIBOU 5 kW Pure-Hydrogen Fuel Cell [

32].

5. Comparative Summary (Selected 5–6 kW Systems)

To provide an overview of the current state of commercial mid-scale fuel cell generators,

Table 1 summarizes selected systems in the 5–6 kW range. The comparison includes key technical characteristics such as rated and peak power, efficiency, hydrogen consumption, weight, volume, integration with battery packs, and other specific features. This highlights the diversity of available technologies (PEM, AFC, PEFC) and their varying trade-offs in terms of performance, portability, and system integration.

6. Hydrogen as a Resiliency Solution

One of the most significant advantages of hydrogen-based electric generators is their role in energy resiliency. Unlike diesel, which requires refining, supply chains, and has limited storage stability (6-12 months without additives), hydrogen can be produced locally via electrolysis using water and renewable electricity. This allows critical facilities, including telecom stations, healthcare providers, and civil defense shelters, to ensure fuel availability even during crises or supply chain disruptions.

Hydrogen, when stored in high-pressure cylinders of higher hydrogen certified standards such as metal hydride tanks, does not degrade over time like diesel or gasoline. Studies and industrial safety data confirm that compressed hydrogen gas remains chemically stable indefinitely under proper conditions, meaning cylinders can be stored for years without fuel quality degradation (with the caveat that periodic safety inspections of valves and tanks are still required). This makes hydrogen a superior choice for long-term emergency preparedness and strategic stockpiling of fuel. These factors-local production and chemical stability-make hydrogen fuel cell generators uniquely suited to provide resilient, long-duration backup power across diverse market segments.

5. Conclusions

Small- and medium-scale fuel cell generators (200 W to 6 kW) emerge as a critical alternative to diesel gensets and heavy battery systems. They offer silent operation, low thermal signature, zero harmful emissions, and flexible sitting options, including indoors with appropriate ventilation. Applications span telecom towers, defense and dual-use military systems, emergency shelters, pharmacies and clinics, and construction projects.

Compared with diesel, hydrogen systems provide higher operational resiliency- hydrogen can be locally produced, safely stored for years, and deployed rapidly without major infrastructure. Compared with batteries, fuel cells ensure long-duration autonomy without impractical size or weight increases. In addition, their low acoustic and thermal signature make them particularly valuable in conflict zones and defense applications.

The current pace for advances in electrolyzer efficiency, falling renewable electricity costs, and growing emphasis on resilient infrastructure are likely to accelerate adoption of fuel cell backup systems. With clear advantages in sustainability, resiliency, and safety, hydrogen-based electric generators are positioned to play a decisive role in powering the critical infrastructure for future energy requirements.

References

- Agnolucci, P. (2007). Economics and market prospects of portable fuel cells. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., & Sehgal, M. (2018). Hydrogen fuel cell technology for a sustainable future: A review. SAE Technical Paper 2018-01-1307. SAE International. [CrossRef]

- Pedro, M., Franceschini, A. E., Levitan, D., Rodriguez, R., Humana, T., & Perelmuter, G. B. (2022). Comparative analysis of cost, emissions and fuel consumption of diesel, natural gas, electric and hydrogen urban buses. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 257, 115412. [CrossRef]

- Hassle, D., Péra, M. C., & Kauffmann, J. M. (2004). Diagnosis of automotive fuel cell power generators. Journal of Power Sources, 128, 239–246. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K., Farrok, O., Rahman, M. M., Ali, M. S., Haque, M. M., & Azad, A. K. (2020). Proton exchange membrane hydrogen fuel cell as the grid-connected power generator. Energies, 13, 6679. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Nehrir, M. H., & Gao, H. (2006). Control of PEM fuel cell distributed generation systems. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, 21, 586–595. [CrossRef]

- Ashitha, P. N., & Lather, J. S. (2016). Fuzzy PI-based power sharing controller for grid-tied operation of a fuel cell. In Proceedings of IEEE SCEECS (pp. 1–6). Bhopal, India. [CrossRef]

- Kirubakaran, A., Jain, S., & Nema, R. K. (2019). A review on fuel cell technologies and power electronic interface. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 13, 2430–2440. [CrossRef]

- Ghlani, C., Al-Ani, I., Khalifeh, F., Alamaari, T., & Hamid, A. K. (2019). Design of solar PV/fuel cell/diesel generator energy system for Dubai ferry. In Proceedings of 2019 ASET International Conference (pp. 1–5). Dubai, UAE. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R., Niroula, S., Pandey, B., Subedi, A., & Thapa, B. S. (2024). Techno-economic assessment of fuel cell-based power backup system as an alternative to diesel generators in Nepal: A case study for hospital applications. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 56, 289–301. [CrossRef]

- Inal, O. B., Zinir, B., Dere, C., & Charpentier, J. F. (2024). Hydrogen fuel cell as an electric generator: A case study for a general cargo ship. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 12, 432. [CrossRef]

- 100% Renewable Energy Atlas. (2019, February 20). Lolland, Denmark. https://www.100-percent.org/lolland-denmark/.

- Associated Press. (2023, March 2). Napa Valley town that once rode out emergencies with diesel gets a clean-power backup. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/california-wildfires-calistoga-energy-vault-hydrogen-batteries-2949e405ac9ce5e52eff835d2fbd4c10.

- European Commission. (2015). Demonstration project for power supply to telecom stations through fuel cell technology (FCpoweredRBS). CORDIS. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/278921/reporting.

- GenCell. (2021). Unit for Israel microgrid, emergency comms in Iceland. Fuel Cell Bulletin, 2, 8. [CrossRef]

- NATO Energy Security Centre of Excellence. (2024, June 10). Executive summary of the field experiment conducted by NATO ENSEC CoE in the summer of 2023, utilizing hydrogen fuel cell technology within the military environment.

- Inci, M. (2022). Future vision of hydrogen fuel cells: A statistical review and research on applications, socio-economic impacts and forecasting prospects. Energy Reports, 53, 102739. [CrossRef]

- Manzo, D., Thai, R., Le, H. T., & Venayagamoorthy, G. K. (2025). Fuel cell technology review: Types, economy, applications, and vehicle-to-grid scheme. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 75, 104229. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Zhu, J., & Han, M. (2023). Industrial development status and prospects of the marine fuel cell: A review. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 11, 238. [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, O. Z., & Orhan, M. F. (2014). An overview of fuel cell technologies for transport and power generation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 32, 810–853. [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N., & Abdulrahman, G. (2024). A recent comprehensive review of fuel cells: History, types, and applications. International Journal of Energy Research, 36, 7271748. [CrossRef]

- Specht, M., Sauer, M., & Witzmann, R. (2017). Overview of the DOE hydrogen safety, codes and standards program, part 3: Advances in research and development to enhance the scientific basis for hydrogen regulations, codes and standards. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 42, 7263–7274. [CrossRef]

- Fuster, B., Houssin-Agbomson, D., Jallais, S., Vyazmina, E., Dang-Nhu, G., Bernard-Michel, G., Kuznetsov, M., Molkov, V., Chernyavskiy, B., Shentsov, V., et al. (2017). Guidelines and recommendations for indoor use of fuel cells and hydrogen systems. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 42(11), 7600–7607. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. M., Lakeman, J. B., & Mepsted, G. O. (2002). Development of a PEM fuel cell powered portable field generator for the dismounted soldier. Journal of Power Sources, 106(1–2), 16–20. [CrossRef]

- Perry, M. L., & Strayer, E. (2006). Fuel-cell based back-up power for telecommunication applications: Developing a reliable and cost-effective solution. INTELEC 06 – Twenty-Eighth International Telecommunications Energy Conference. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, O., Ishaq, H., & Dincer, I. (2021). Development and performance assessment of new solar and fuel cell-powered oxygen generators and ventilators for COVID-19 patients. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 46, 33053–33067. [CrossRef]

- Calise, F., Cappiello, F. L., Cimmino, L., Dentice d’Accadia, M., & Vicidomini, M. (2024). A novel layout for combined heat and power production for a hospital based on a solid oxide fuel cell. Energies, 17(5), 979. [CrossRef]

- Zoulias, E. I., & Lymberopoulos, N. (2007). Techno-economic analysis of the integration of hydrogen energy technologies in renewable energy-based stand-alone power systems. Renewable Energy, 32(4), 680–696. [CrossRef]

- PowerUP Energy Technologies. (2025). Transforming the way we power up: Hydrogen fuel cell solutions.

- Caravan and Motorhome. (2007). European RV makers offer EFOY fuel cells. Caravan and Motorhome. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- SFC Energy AG., EFOY Hydrogen 2.5 fuel cell. https://www.efoy-pro.com/en/efoy/efoy-hydrogen/ (accessed on 01 September 2025).

- Panasonic Holdings Corporation. (2024, April 25). Panasonic Launches 10 kW Pure Hydrogen Fuel Cell Generator in Europe, Australia, and China. Panasonic Newsroom. https://news.panasonic.com/global/press/en240425-1 (accessed on 01 September 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).