1. Introduction

The international trade and transport of live animals can result in species being introduced accidently or maliciously to countries outside their native range. When this occurs, they are classified as a non-native species (NNS). If NNS reach the wild non-native range, either intentionally or accidentally, they may establish themselves, become invasive, and negatively impact local biodiversity. Invasive NNS disrupt ecosystems by introducing disease, preying on native species, and outcompeting them for food, territory, and mates [

1]. Additionally, the economic burden of managing non-native aquaculture introductions in the UK has risen sharply, with costs increasing by 139.5% annually to £18 million [

2], highlighting the growing strain on national resources.

American lobsters (

Homarus americanus) are a non-native species to Europe, and are imported as live seafood, but they have been detected in the wild. They can carry pathogens such as gaffkaemia [

3] which threaten European lobsters (

Homarus gammarus), evidence also suggests that

H. americanus prey on

H. gammarus [

4]. Furthermore, there are concerns about interbreeding

between H. gammarus and

H. americanus, which can result in hybrid offspring [

5]. Effective regulations and monitoring are essential to protect local ecosystems from both intentional and accidental invasions [

6]. Rapid and accurate methods to identify NNS and trace their origins are urgently needed. These tools would enable the implementation of movement restrictions, eradication measures, and, where appropriate, prosecutions against those endangering native biodiversity.

Previously, identification of

H. americanus and

H. gammarus has been carried by morphological criteria such as exoskeleton colouration, and presence/absence of the ventral spines on the rostrum. However, it has been demonstrated that identification based solely on morphological criteria can lead to potential misidentification [

7,

8,

9]. Another method of identification is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of specific loci which produce different sized products [

9], these regions’ sequences are currently not published, and so the reason for the differences is uncertain, potentially limiting the accuracy of its use in speciation. Most recently there have been advances in single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array analysis [

7], which can differentiate

H. gammarus,

H. americanus, and determine the likelihood of a specimen being a hybrid. However, this method requires specific equipment that not all laboratories have access to and is better suited to definitive analysis of pre-flagged sample batches rather than ad-hoc screening and/or small-scale sampling due to cost per sample.

Here, we outline the process of sequencing the Hgam98 locus, a previously described diagnostic nuclear locus [

9], and the COI gene for possible primer design locations. Since COI is mitochondrial, a COI-based assay would detect any purebred American lobsters (both male and female).

Homarus species tend to prefer conspecific [

10], and the chances of European females finding only American males in their local environment seems unlikely, whereas American females may find dominant European males. This would mean the likelihood that a hybrid animal would have American mitochondrial DNA. However, it is worth noting that American male parentage is also possible, which would not be detected by this assay. During the design process of this project, two animals were discovered off the coast of Cornwall (50°18'44.1"N 4°40'09.0"W), displaying potential

H. americanus and

H. gammarus mixed morphologies, which were also assessed for hybridisation, highlighting the importance of molecular analysis over morphological identification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Material and DNA Extraction

Tissues of American and European lobsters were collected from adults sourced from their native ranges (

Table 1), via the sub-lethal excision of pleopod and/or pereiopod sections [

9,

11]. Hybrids of the two species were collected as the larval offspring of an American female captured in Sweden and fertilised by a European male, as ascertained by previous research [

9]. All samples were preserved in absolute ethanol and stored at -20 °C, prior to DNA being isolated via a modified salting-out protocol [

11]. DNA from six individuals from each of these European, American and hybrid lobster cohorts were obtained (

Table 1).

Additionally, pleopod tissues were supplied from two adult lobsters captured in Cornwall, U.K., by the Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authorities (IFCA); these lobsters both exhibited the presence of a sub-rostral ‘tooth’ and reddish coloured spines, traits typically associated with American lobsters, albeit with broader morphologies characteristic of the European lobster.

DNA from these two samples was extracted by taking 0.1 g of tissue in a 1:10 dilution of G2 buffer and proteinase K at 0.2ug/ml (Qiagen) into a 2 ml lysing matrix A tube (MP biomedicals). The contents of these tubes were then subjected to mechanical disruption using a fast-prep 24 classic (MP biomedicals) at 4 m/s for sixty seconds before incubation overnight at 56 °C. Digests were then subject to extraction with the DNA tissue kit (Qiagen) via an EZ1 Extraction robot (Qiagen) and the nucleic acid was eluted into a 50 µl volume.

2.2. DNA Amplification and Sequencing

To amplify the Hgam98 locus, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in a 50 µl volume containing 2.5 µl of the DNA elution, 0.5 µl of 25 mM dNTPs, 10 µl of 5x green GoTaq flexi buffer, 5 µl of 25 mM MgCl

2, 0.25 µl of GoTaq G2 Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega), 0.5 µl of forward and reverse Hgam98 primers at 10 µM (

Table 2) and made up to 50 µl with molecular biology grade water. The cycling program had an initial denaturation at 94 °C for five minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for one minute, 55 °C for one minute and 72 °C for one minute, with a final extension of 72 °C for ten minutes. PCR products were resolved on 3% agarose gel (w/v) agarose/TAE (40 mM Tris-acetate, pH 7.2, 1 mM EDTA) containing 1.0 µg/ml ethidium bromide, at 120 V for thirty minutes. Products of the expected size were excised, and the DNA purified using spin modules (MP Biomedicals). Both strands of the DNA were sequenced by Sanger sequencing using Big Dye Terminator 3.1 methodology (Life Technologies) using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol and the sequences were analysed on a 3500xl genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems) and consensus sequences generated using CLC workbench 24 software (Qiagen). Contigs were then aligned and compared using MEGA 7 software [

12].

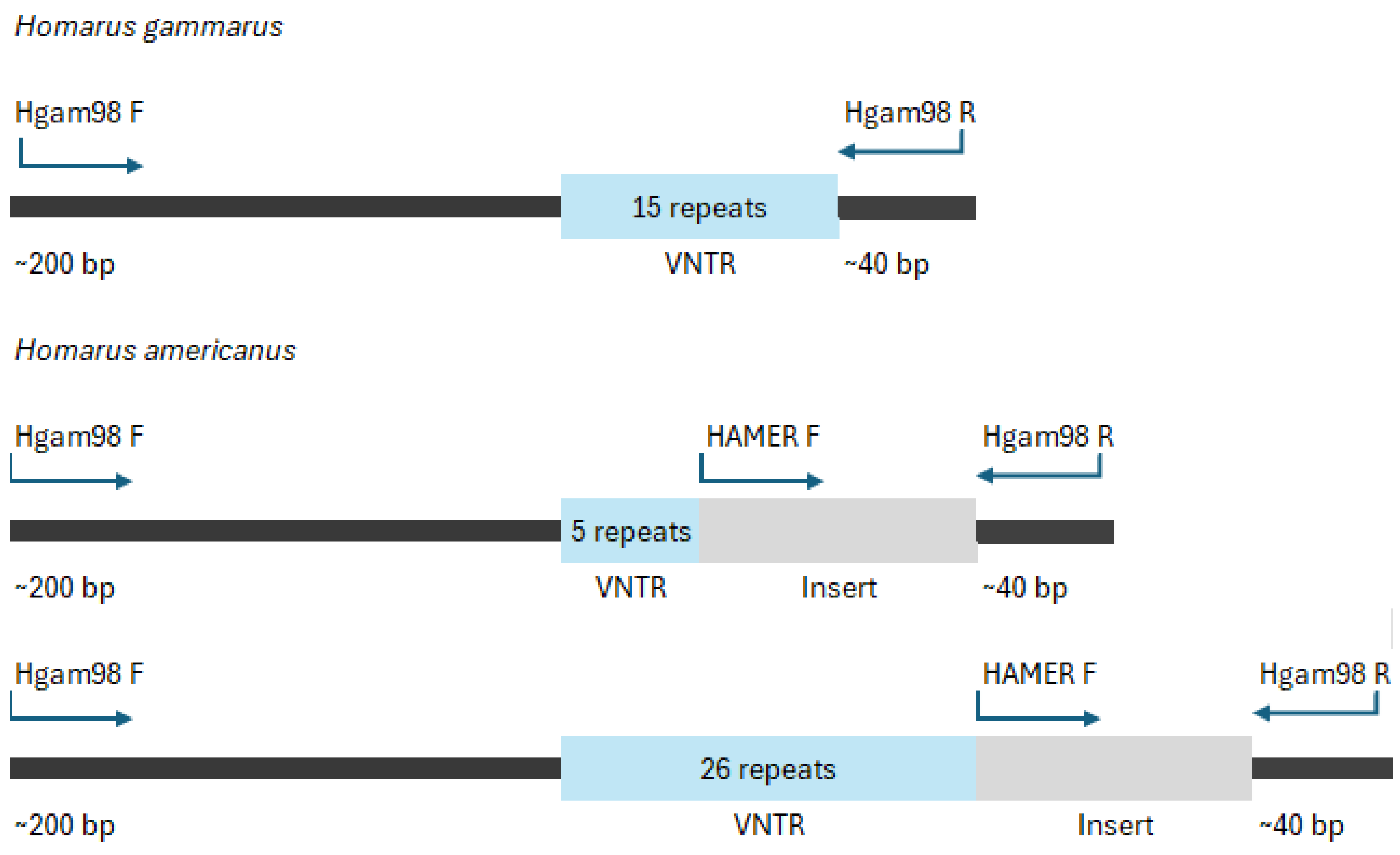

2.3. Duplex Conventional PCRs

Using the sequencing data from the Hgam98, an additional primer (HAMER) was designed located in the

H. americanus insert (

Table 2 and

Figure 1), which was combined with the primers of the Hgam98 assay. This PCR was conducted using the same method as above, but with the addition of 0.5 µl of the HAMER F primer.

2.4. Real-Time PCR Design and Application

A Real-Time PCR assay was developed targeting the Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COXI) since regions of this gene can be used to identify

H. americanus and

H. gammarus. The primer pair COI_H_SP_F/R (

Table 2) was designed to amplify a 90 bp fragment of COI. Primers and probes were designed

in silico by aligning sequences obtained from Blastn search engine (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool [

13]). The real-time assays were performed in a 20 µl duplex reaction volume containing 2.5 µl of DNA template extracted from American and European lobster samples 10 µl of TaqMan universal master mix (Life technologies), 1 µl of each primer and probe, and made up to 20 µl with molecular grade water. Assays were performed on a Quantstudios 3 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems) using cycling settings with an initial hold stage of 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, and 62 °C for 1 minute. Each plate included two negative controls (NEG) to ensure the absence of contamination.

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing the Hgam98 Locus

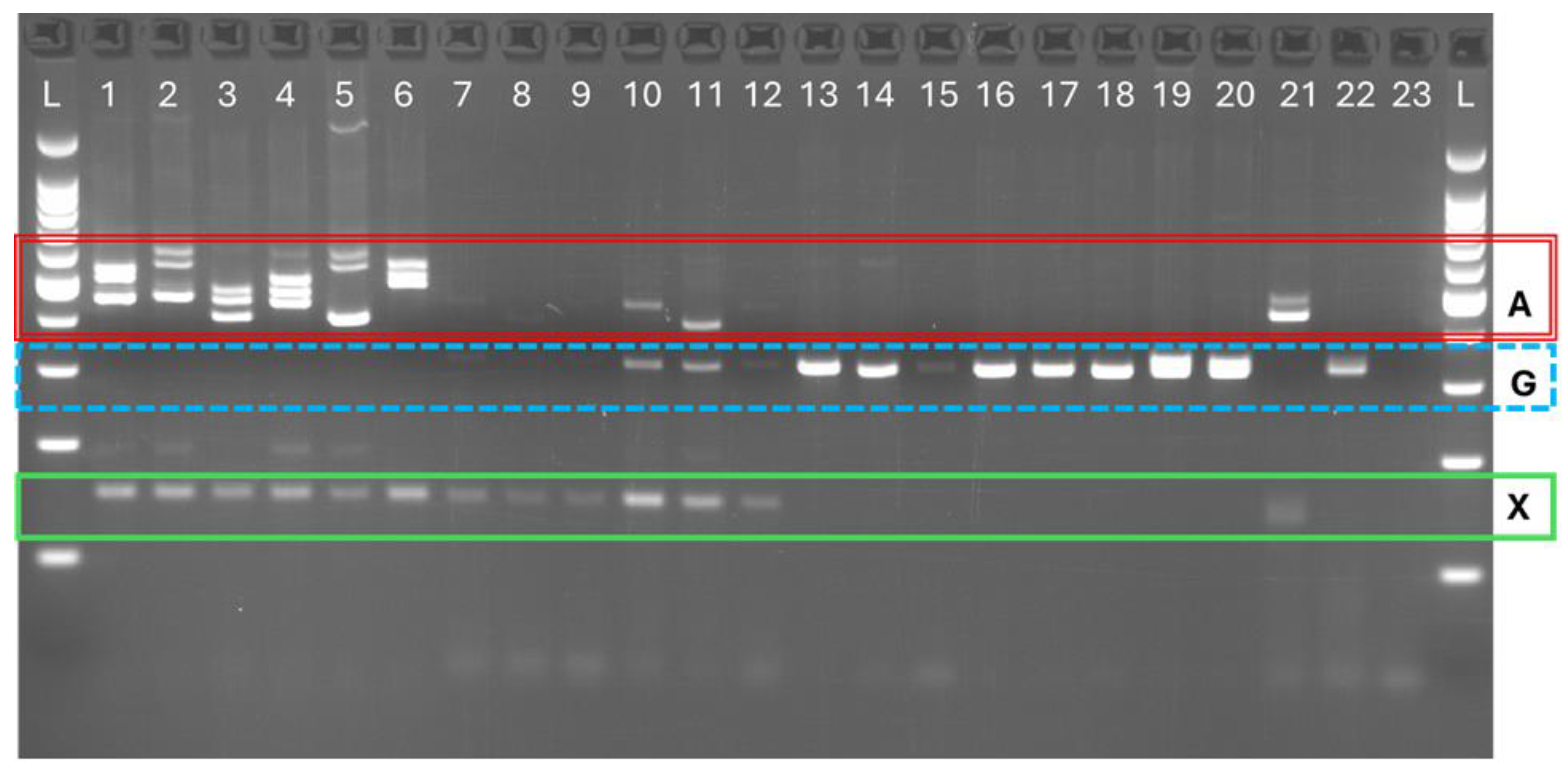

The Hgam98 PCR products showed the expected size for

H. americanus (~440 - 500 bp) and

H. gammarus (~290 - 330 bp) (

Figure 2). The sequencing of six

H. americanus and six

H. gammarus animals showed a segmental similarity where

H. americanus and

H. gammarus share an identical 5` 211 bp region before diverging into variable nucleotide tandem repeat (VNTR) regions. In

H. gammarus samples, the number of repeats remains mostly the same whereas

H. americanus samples showed a greater range of sizes (

Table 1). Additionally,

H. americanus has a 120 bp insert that is absent in

H. gammarus. The two species then reconverge with an identical 40 bp sequence at the 3` end (

Figure 2). In the case of hybrids, alleles with the expected size for

H. americanus and

H. gammarus were observed in some of the individuals genotyped (lanes 10 and 11). However, for other individuals very faint or no bands were observed for Hgam98 (lanes 7, 8, and 9), but a clear band with the expected size was observed using the HAMER primer (lane 7 to 12).

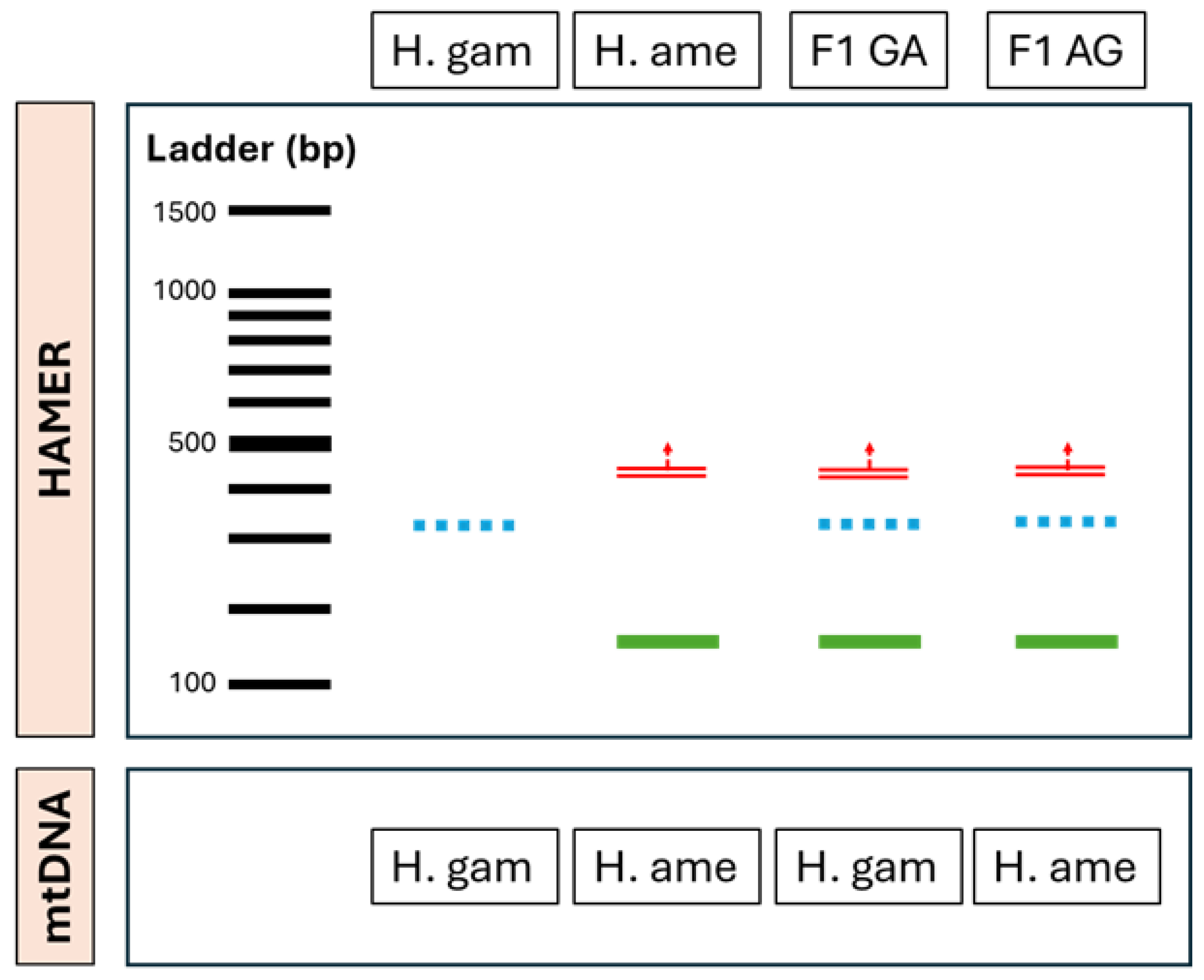

3.2. Duplex Conventional PCR

When used in conjunction with the Hgam98 assay, the HAMER primer produced no additional product for

H. gammarus samples but did produce PCR products of ~150 bp for

H. americanus (

Figure 3). When sequenced, these products showed 100% nucleotide sequence similarity to the

H. americanus insert. In the hybrids tested, the 152 bp insert was observed, and again, with 100% nucleotide similarity to

H. americanus insert.

The putative hybrids from Cornwall showed only H. gammarus products, and no H. americanus, or HAMER products.

3.3. Real-Time PCR

The linearity of the assays was checked through the analysis of three replicates of a ten-fold serial dilution of known DNA (108 to 10 copies of template). The regression coefficient (R2) and slope for the H. americanus assay was 0.990 and –3.383, respectively. For the H. gammarus assay, the R2 and slope were 0.999 and –3.333, respectively. These results indicate that, within the range of DNA amounts tested, the assays gave reliable results, and both assays could detect positives at 10 copies with Ct values of 34.7 for H. americanus and 33.7 for H. gammarus.

The potential hybrid material from Cornwall produced only positives with the

H. gammarus probe. These animals were then subjected to the SNP analysis [

9] to confirm results as part of the validation, formally identifying these animals as native European lobsters (

H. gammarus).

4. Discussion

The results obtained have explained the reason for the product size differences between H. americanus and H. gammarus when using the HGAM98 PCR assay, this aids in the justification of its use, but highlights limitations as fewer repeats could be misread as a H. gammarus positive. The further development of the HAMER duplex protocol helps identify not only NNS American lobsters, but potentially also H. americanus X H. gammarus F1 hybrids. Additionally, the results also suggest that the Real-Time PCR assay can accurately differentiate between H. americanus and H. gammarus mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), with each specific probe detecting its respective species as seen in the real-time graphs. Since the assays could detect DNA at 10 copies and the detections of the hybrid material as H. americanus it highlights the potential to detect American maternal F1 hybrid animals rapidly, and more cost effectively on an ad hoc sample basis.

In the case of the lobsters of mixed morphology captured off the coast of Cornwall, all tests identified the individuals as being

H. gammarus, a determination confirmed by the SNP-based method of Ellis et al [

9] (data not presented). This highlights the importance of having additional reliable molecular methods of species determination, since morphological traits are unreliable and can show signatures of mixture that cannot be attributed to hybridisation, and SNP-based methods may be too expensive for some authorities to set-up if only sporadic testing is likely.

During this experiment, it was discovered that the salting-out method (Jenkins et al 2019) incurred PCR inhibitors [

14], which were mitigated by diluting each sample 1:10 with molecular biology grade water. It is also worth noting that sequence data for hybrids is extremely limited due to their rare occurrence, in this study, all six hybrid animals were full siblings that were hatchery produced. This means there is the possibility that this range of methods may not detect certain types of hybrids, such as

H. gammarus (female) X

H. americanus (male) X, or any potential F2 or backcrossed hybrids. However, it is hoped that the methods outlined in this study will not only improve the efficiency and practicality of monitoring for non-native

H. americanus but also aid in the detection of hybridisation amongst wild lobster stocks. The HAMER duplex protocol adequately detected the hybrid siblings we tested, and the Real-Time PCR assay for COI could provide rapid flagging of hybrids with

H. americanus maternity, even if they displayed European morphologies. These molecular resources can enhance the toolkit available to monitor the presence of

H. americanus, H. gammarus and F1 hybrids in regions where they might have been introduced, offering rapid and cheap screening compatible with bulk sample processing or routine monitoring.

To surmise, we believe due to the low cost and rapid results, the addition of these assays to the suite of tests, like SNP analysis can greatly improve detection rate in NNS monitoring. This study had a limited sample size, especially with regards the hybrid material, but it is felt this project demonstrates a proof of concept, and future studies with additional hybrid lineages, and qPCR analysis on eDNA samples would further validate the approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.E.; methodology, M.E. and C.E.; resources, M.E. and C.E.; writing: original draft preparation, M.E.; writing: review and editing, C.E. and F.B.; supervision, F.B.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and granted an exemption by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Bodies (AWERB). No live animals were handled and all samples of Homarus americanus and Homarus gammarus were collected post-mortem, and therefore the work did not fall under regulations requiring ethical approval. The study was conducted in accordance with international standards for research integrity and animal welfare (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carly Daniels for supplying samples from the Cornish Inshore Fisheries & Conservation Authority (IFCA)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COX1 |

Cytochrome c Oxidase gene 1 |

| NNS |

Non-Native Species |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SNP |

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| IFCA |

Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authorities |

| VNTR |

Variable Nucleotide Tandem Repeat |

References

- Manchester S.J.; Bullock J.M. The impacts of non-native species on UK biodiversity and the effectiveness of control. Journal of Applied Ecology 2000, 37(5), 845–864. [CrossRef]

- Eschen, R., Kadzamira, M., Stutz, S. et al. An updated assessment of the direct costs of invasive non-native species to the United Kingdom. Biol Invasions 2023, 25, 3265–3276. [CrossRef]

- Stewart J.E. Gaffkemia, the Fatal Infection of Lobsters (Genus Homarus) Caused by Aerococcus viridans (var.) homari: A Review. Marine Fisheries Review 1975, 37(5–6), 20–24.

- Øresland V., Ulmestrand M., Agnalt A.L., Oxby G. Recorded captures of American lobster (Homarus Americanus) in Swedish waters and an observation of predation on the European lobster (Homarus Gammarus). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2017, 74(10), 1503–1506. [CrossRef]

- Stebbing P., Johnson P., Delahunty A., Clark P.F., McCollin T., Hale C., Clark S. Reports of american lobsters, homarus americanus (H. milne edwards, 1837), in British waters. BioInvasions Records 2012, 1(1), 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Mozer A., Prost S. An introduction to illegal wildlife trade and its effects on biodiversity and society. Forensic Science International: Animals and Environments 2023, 100064. [CrossRef]

- Ellis C.D., Jenkins T.L., Svanberg L., Eriksson S.P., Stevens J.R. Crossing the pond: genetic assignment detects lobster hybridisation. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Jacquet J.L., Pauly D. Trade secrets: Renaming and mislabeling of seafood. Marine Policy 2008, 32(3), 309–318. [CrossRef]

- Jørstad K.E., Prodohl P.A., Agnalt A.L., Hughes M., Farestveit E., Ferguson A.F. Comparison of genetic and morphological methods to detect the presence of American lobsters, Homarus americanus H. Milne Edwards, 1837 (Astacidea: Nephropidae) in Norwegian waters. Hydrobiologia 2007, 590(1), 103–114. [CrossRef]

- van der Meeren G.I., Chandrapavan A., Breithaupt T. Sexual and aggressive interactions in a mixed species group of lobsters Homarus gammarus and H. americanus. Aquatic Biology 2008, 2(2), 191–200. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins T.L., Ellis C.D., Stevens J.R., Jenkins T.L. SNP discovery in European lobster (Homarus gammarus) using RAD sequencing. Conservation Genetics Resources 2019, 11(3), 253–257. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2016, 33(7), 1870–1874.

- Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 1990, 215(3). 403-410. [CrossRef]

- Schrader C., Schielke A., Ellerbroek L., Johne R. PCR inhibitors – occurrence, properties and removal. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2012, 113(5), 1014–1026. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).