1. Introduction

The dog population can be conventionally divided into three groups: purebred dogs, mixed-breed dogs (mongrels – without a known share of parent breeds), or hybrid dogs, sometimes called "designer" breeds, where the share of parent breeds is known or even desired [

1]. The term purebred dog refers to an individual whose parents belong to the same breed – they are characterised by the same exterior and interior, i.e. they meet the requirements of the breed standard and have documented origin. Many of today's dog breeds were created by crossing other breeds with each other in order to achieve the effect of cumulating the positive traits of the parent breeds. Currently, we can come across so-called “designer” dog breeds, such as the increasingly popular Labradoodle, Goldendoodle, and Cockapoo, or the lesser known Bernendoodle, Chorkie or the excellent, working sled dog Greyster. Designer breeds are currently causing great controversy due to their growing popularity, but also because of the threats they pose to established breeds and their breeders. However, it cannot be forgotten that in the case of descriptions of the origins of the vast majority of dog breeds recorded and registered today by kennel clubs or cynological organisations, other groups or dog breeds known at the time participated in their creation. Therefore, it can be argued that many of today's recorded breeds originate from so-called designer or hybrid breeds, which were created based on crosses of various original breeds. For example, it is believed that the modern Doberman was bred by a German tax collector of the same name by crossing old-type German Shepherds, Rottweilers and German Pinschers, also known as German Terriers [

2]. Another excellent example is the Kromfohländer registered in group IX Toy and Companion Dogs (as the only one in its section), derived from crossing the Fox Terrier and the Vendeen Griffon [

3]. Mixed dogs, often called mongrels, unlike purebred dogs, are usually the result of accidental, unplanned mating, and may be the result of crossbreeding different purebred dogs or other mixed breed dogs. Mixed breed dogs do not have described and registered breed standards, i.e. a detailed description of the interior and exterior features required for purebred dogs [

1]. Their appearance and also psychological traits are very diverse and in the case of a puppy we cannot predict what it will look like in the future or how it will behave. On the other hand, the deliberate mixing of breeds, as a result of which we get so-called "hybrid" or "designer" dogs, aims to create new, previously unseen individuals with desired traits, usually related to a specific appearance, but also taking into account desirable behavioral traits. The best example of this would be the Labradoodle breed, which was intentionally created by Wally Conron in 1989 to combine the coat characteristics of the Poodle (no or very little shedding, less allergenic properties) with the temperament, intelligence, and personality of the Labrador, known as an excellent service dog. Since Poodles come in three sizes, Labradoodle puppies also vary in both size and coat quality - sometimes they may look more like a Poodle and sometimes more like a Labrador.

Since the end of the 20th century, we have been observing a growing interest in dogs originating from crossbreeding of different breeds. In addition to the Labradoodle, the Maltipoo, Cavapoo and Cockapoo are also popular, which originated from crossbreeding poodles with the Maltese, Cavalier and Cocker Spaniel, respectively. They are not only considered to be non-shedding, hypoallergenic dogs, but are also pretty - their coat is wavy or curly, they come in different coat colors, and they are known for their friendly, cheerful and nice disposition. "Hybrid" dogs often command higher prices than their purebred parents. This results in a fairly rapid increase in the number of breeders focused on breeding dog hybrids. These breeders try to perpetuate the desired traits in subsequent generations so that the "hybrid variety" can be recognized as a true breed in the future. An example is the Maltipoo breed, which has been recognized in the USA for 30 years. The great popularity and demand for such dogs also caused an increase in the number of so-called "pseudo-breeding", "puppy mills" or "puppy farms" focused on financial profits and operating similarly to factories of saleable goods. Such "production" is burdened with a high risk: puppies from parents of 2 different breeds may differ significantly in size, type of coat, or body structure. There is no guarantee that after crossing individuals of two different breeds we will receive the desired phenotype in the first generation. We are also not able to predict in any way which genes will be revealed in them. In addition, dogs from "puppy farms" are often not tested and treated, they may be burdened with genetic defects, be ill or be carriers of undesirable genes characteristic of the parent's breeds. Often, such puppies are not dewormed or vaccinated. Therefore, it seems extremely important to be able to genetically control "hybrid" dogs, which may prove important for the protection of purebred dogs in order to maintain the purity of breeds.

Another problem that can be observed in the breeding of hybrid or mixed-breed dogs is double mating. This involves mating a given female dog in the same heat with two different sires in order to obtain puppies from two fathers (i.e. two different "hybrids") in one litter. It can be planned by the breeder or happen randomly, without the breeder's knowledge. Even planned double mating is not in line with the breeding regulations of most respectable kennel clubs. This widespread practice has led to the creation of different rapid identification tests for breeds or mixed breeds, it also led to the need of developing DNA tests to confirm genetic affiliation to a given breed or the identification of breeds in hybrids and mixed breeds. These tests are becoming increasingly popular, but unfortunately, they are not always reliable and effective. An investigative study was conducted to test the accuracy of commercially available DNA genetic tests. Biological material was collected from two mixed-breed dogs, one pedigree dog, and one human and sent to four companies for testing. Except for the case of a pedigree dog, for which two genetic tests showed the correct result, the others were contradictory [

4]. Only the use of validated genetic tests provides a basis for conducting a reliable analysis of the breed identification of a dog. For such tests, a set of 21 DNA microsatellite markers (STR - short tandem repeat) can be used, which is recommended by the International Society of Animal Genetics (ISAG) for routine pedigree tests of dogs [

5,

6,

7]. The use of the developed STR set for individual and pedigree identification of dogs in combination with the Bayesian model of assigning individuals to a cluster or clusters implemented in the STRUCTURE program can distinguish a genetically pure breed from crossbreeds and statistically assign individual individuals to breeds [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Another frequently used method that uses STR markers to demonstrate genetic similarity and group individuals according to their breed affiliation is principal coordinate analysis - PCoA [

13,

14]. In our research, we used both the STRUCTURE and PCoA methods to analyse two interesting cases: 1) a litter of 11 Golden Retriever (GR) puppies, almost half of which were black at birth (a coat color unacceptable for GR), suggesting the involvement of another male in the fertilization process; 2) a puppy that was purchased as a Chinese Crested Dog (CC), but during development began to exhibit surprising coat-related characteristics characteristic of the Poodle breed (PD).

This study aimed to verify whether the analysis of DNA microsatellite polymorphism using 21 STR routinely used for dog identification and pedigree control can also be effectively used for the genetic identification of a dog breed – a mixed breed – two-breed crosses using a reference population of purebred individuals of selected breeds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

For population studies, calculation of statistical parameters, and analysis of the genetic structure of selected breeds of dogs, the results of pedigree studies collected in the DNA database National Research Institute of Animal Production (NRIAP) in 2018–2023 were used. Blood samples were collected from dogs undergoing routine parentage testing at NRIAP. All the sampled animals were registered with the Polish Kennel Club. A total of 473 unrelated dogs have been chosen to collect reference groups, representative samples of the Polish population, including a Poodle (PUD, n=85), a Chinese Crested Dog (CC, n=84), a Bernese Mountain Dog (BM, n=114), and a Golden Retriever (GR, n=190).

The analysis of two cases was carried out upon request of dog owners. The first case concerned 11 puppies from the same litter probably from double mating. The mother of the puppies was a Golden Retriever, and the potential fathers were - one Golden Retriever and one Bernese Mountain Dog. The second case concerned confirmation of the puppy's breed purchased as a Chinese Crested Dog that did not correspond phenotypically to the breed pattern.

2.2. Methods

DNA was extracted from swabs and blood samples using the Sherlock AX Kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). In the analysis, we selected 21 loci from the recommended ISAG core panel for the identification of individuals and parentage testing in the dogs: AHTk211, CXX279, REN169O18, INU055, REN54P11, INRA21, AHT137, REN169D01, AHTh260, AHTk253, INU005, INU030, FH2848, AHT121, FH2054, REN162C04, AHTh171, REN247M23, AHTH130, REN105L03, REN64E19, and Amel locus. The markers and used primer sequences are presented by Goleman et al. [

15]. The STR loci were amplified using Phusion U Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The PCR reaction was performed on Veriti® Thermal Cycler amplifier (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), using the following thermal profile: 5 min of initial DNA denaturation at 98°C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 15 s, annealing at 58°C for 75 s, elongation of starters at 72°C for 30 s, and final elongation of starters at 72°C for 5 min. The obtained PCR products were analysed using an ABI 3130xl capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The amplified DNA fragments were subjected to electrophoresis in 7% denaturing POP-7 polyacrylamide gel in the presence of a standard length of 500 Liz and a reference sample. The results of the electrophoretic separation were analyzed automatically using the GeneMapper® Software 4.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

2.2.1. Data Analysis

The statistical analysis of the obtained results was carried out based on the genetics parameters: observed heterozygosity – HO, expected heterozygosity – HE, and inbreeding coefficient – F

IS for each marker were calculated according to Nei and Roychoudhury [

16], and Wright’s [

17]. Polymorphic information content – PIC was estimated by Bostein [

18]. The probability of parentage exclusion was calculated for two cases when the genotypes of one and both parents are known - PE

1 and PE

2 [

19]. The statistical analysis was carried out using the IMGSTAT software, ver. 2.10.1 (2009), which supports the laboratory of the National Research Institute of Animal Production.

Population Structure was analysed using a Bayesian clustering algorithm implemented in STRUCTURE software version 2.3.4 [

20], considering an admixture model with correlated allele frequencies between breeds. The lengths of the burn-in and Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) simulations were 100,000 and 500,000, respectively, in 5 runs for each number of clusters (K) ranging between 2 and 6. The population relationships based on principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) were obtained using the GenAlEx ver. 6.51 software [

21].

3. Results and Discussion

Mixed-breed dogs that do not have any purebred ancestors within several generations are often difficult or impossible to identify. The inherited variants of DNA that are unique to specific breeds get lost with each generation of mixed-breed progeny which is why mixed-breed dogs that do not have any purebred ancestors within 2-3 generations are often difficult or impossible to identify. In contrast to first-generation crosses between two purebred parents which are relatively easy to identify. However, to carry out such breed identification it is necessary to have a reference population representing these breeds.

In our study, we have used reference populations representing 4 dog breeds, which enabled the analysis of 2 cases of breed identification of puppies. First concerning the confirmation of the breed affiliation of puppies to the breeds of alleged fathers - GR and BM from an unplanned double mating (

Figure 1). The second - confirmation or exclusion of the breed of a purchased puppy as a Chinese Crested dog, whose appearance raised suspicions that another breed participated in its phenotype and with the continuous growth of the puppy, the deviation from the Chinese Crested breed standard increased (

Figure 2).

At the first stage of the study, the polymorphism of 21 STR markers was assessed in the established reference populations for the studied breeds. Estimates of within-breeds genetic diversity are summarized in

Table 1. The highest average heterozygosity was found for the Chinese Crested Dog (Ho=0.56 and HE=0.61). Similar Ho and HE >0.5 values were obtained in the rest of the breeds. Similar Ho and He values had low Fis values ruling out the occurrence of inbreeding in these populations. The population inbreeding coefficient – FIS was low and ranged from 0.003 (BM and PD) to 0.053 (CC). Mean PIC values for the studied breeds were at the same level of PIC>0.5. The degree of polymorphism and heterozygosity observed and expected at a level above 50% is similar to the variability observed in many other dog breeds in the world [

6,

7,

12,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], and it indicates the usefulness of this panel for further research.

Parentage confirmation from the indicated parents was carried out through a comparative analysis of the established DNA profiles, and the assessment of the genetic structure of the examined breeds was made using two different approaches: STRUCTURE and PCoA. The probability of exclusion was calculated for two situations with one parental genotype available (CPE

1) and two parental genotypes available (CPE

2). The cumulative exclusion probability for CPE

1 and CPE

2 was higher than 0.99 and 0.9999, respectively, which indicates that in the studied breeds, we can exclude the origin of the dog with 99% probability when we know the genotype of one of the parents and with over 99.99% when we know the genotype of both parents (

Table 1). Such exclusion probability allows for a reliable analysis of the parentage verification of the presumed/indicated parents [

29,

30,

31,

32].

The genetic population structure of each study breed was determined based on the admixture level for each dog using the correlated allele frequencies model implemented within the STRUCTURE software. For some breeds, such as Pitbull or the Doberman above-mentioned, genotypes do not refer to a single group of individuals of a recognized breed, but to the genetically diverse groups, most often depending on the breeding region [

33,

34], which share similar physical features. For such breeds, creating a reference population that creates one coherent cluster is difficult or even impossible, which does not allow for genetic breed identification of dogs that can be phenotypically classified as a given breed. In addition, it must be borne in mind that when the dog comes from a foreign breeding, or its parents come from another, separate population, the test may not confirm belonging to the expected breed. This is due to genotypic differences between a given individual and a reference population created from the national population. Variants of the genetic markers (alleles) used may be incompatible with marker variants in our native population. However, it has been shown that canine STRs exhibit breed-specific genotype patterns and that STR panels could be suitable for differentiating dog breeds [

7,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In the study by Leroy et al. 2009, covering 1514 dogs representing 61 dog breeds, 95.4% of dogs were correctly assigned to their breed, of which in the case of 44 breeds, including Golden Retriever, Bernese Mountain Dog, the percentage of correct assignment was close to 100% [

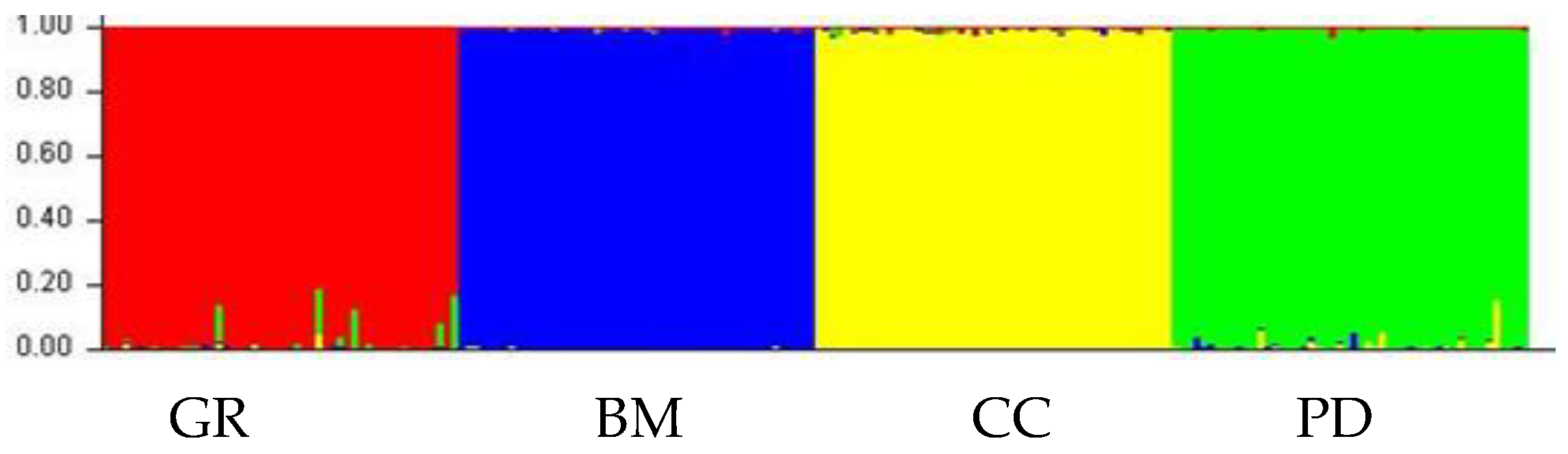

35]. Reference populations based on 21 STRs for 4 studied breeds: Golden Retriever, Bernese Mountain Dog, Chinese Crested Dog, and Poodle allowed for the establishment of genetically uniform clusters composed of individuals with similar genetic structure for each breed. Bayesian analysis of the structure of 473 reference dogs showed the existence of 4 genetic clusters (K=4,

Figure 3). All reference dogs of each breed were assigned to a separate cluster with an average probability ranging from 97.7% to 99.9%, similar to the study by Schelling et al. [

36], who, based on the same set of 21 STRs, 311 animals and 7 breeds, obtained 96.5% correct assignment. This indicates that this method can be successfully applied to further studies.

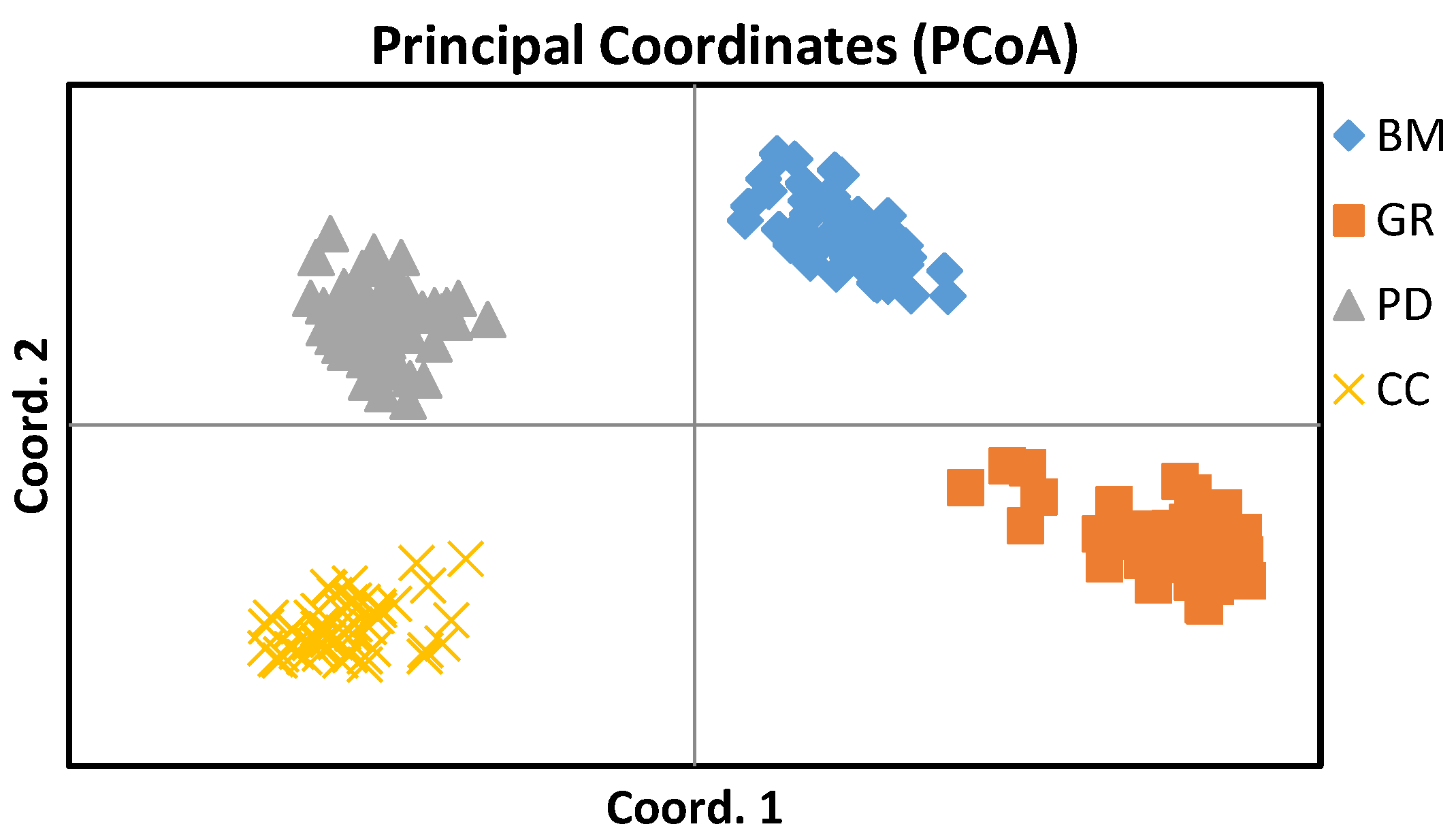

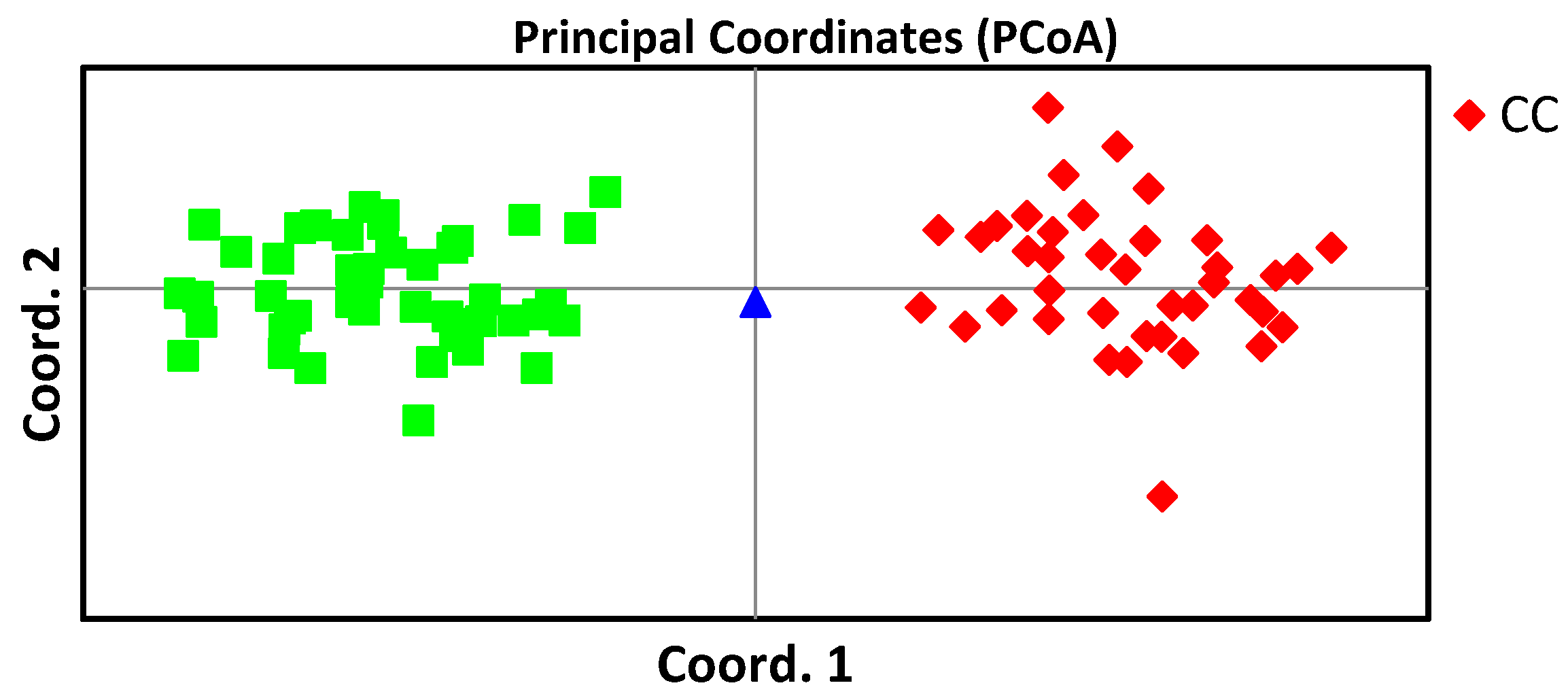

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was also used to estimate the genetic distance between the studied canine breeds. The pattern genotype distributions on the plot showed separate clustering of the study breeds and revealed a high pattern of groupings. PCoA results obtained with clearly separated 4 groups are in perfect concordance with the results of STRUCTURE analyses, which indicated the 4 clusters, representing 4 dog breeds. (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Case Study 1

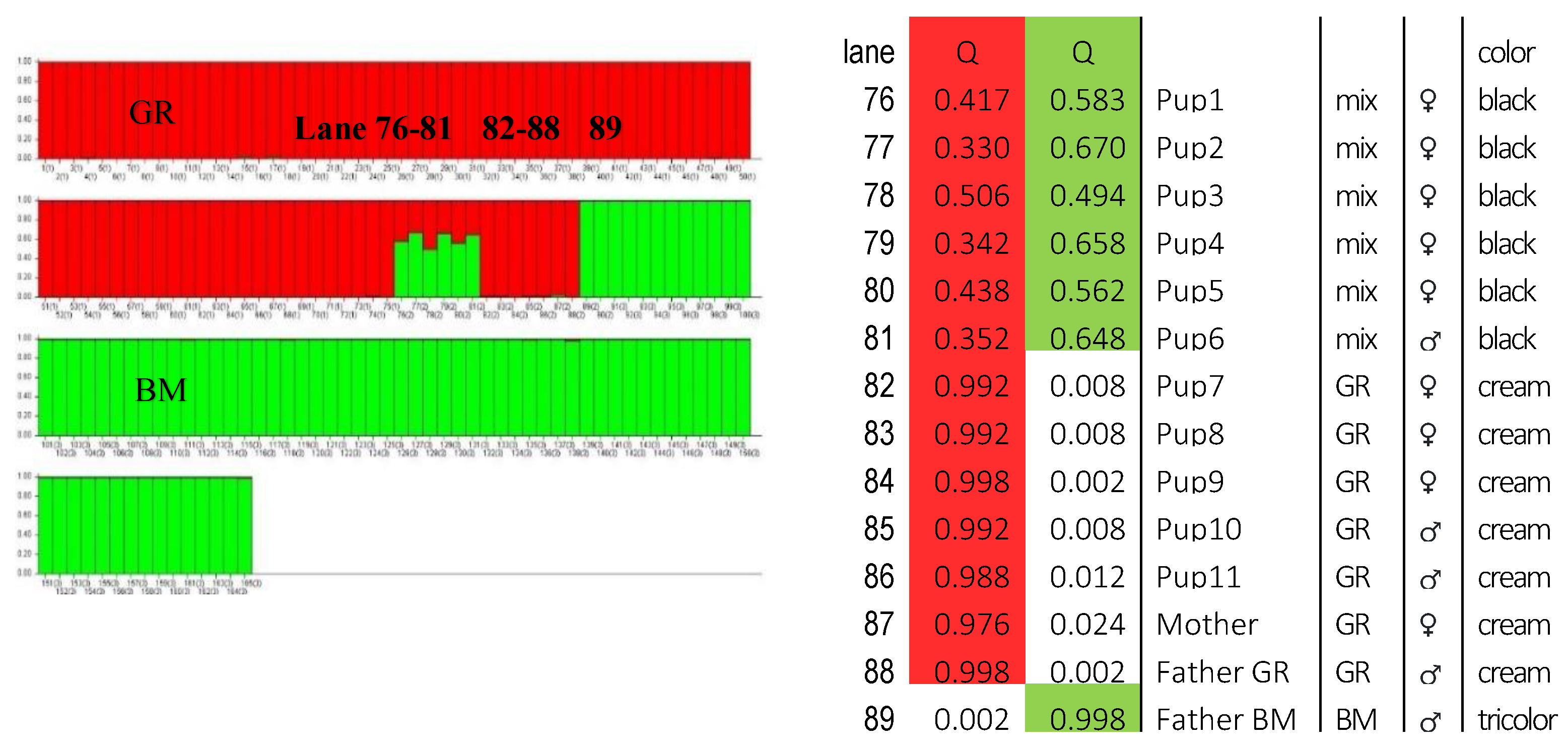

DNA profile analysis at 21 microsatellite loci in 11 puppies from a litter suspected of double mating confirmed the origin of all puppies from the indicated mother - a GR bitch and from two alleged fathers. Of the examined puppies, 6 were consistent with a BM dog and 5 with GR (Supplementary,

Table S1). In the analysis of the genetic structure of the litter conducted in the STRUCTURE program, the mother (lane 87), one of the fathers (lane 88) and 5 puppies were clearly assigned to the GR breed (lane 82-86). The mother with a probability of 97%, while the father and puppies with a probability of > 98%. The remaining 6 puppies (lanes 76-81) were assigned to both the BM breed and the GR breed with a probability of 34% to 60%. The second father (lane 89) clearly clustered with BM individuals with a high – 99.8% probability (

Figure 5).

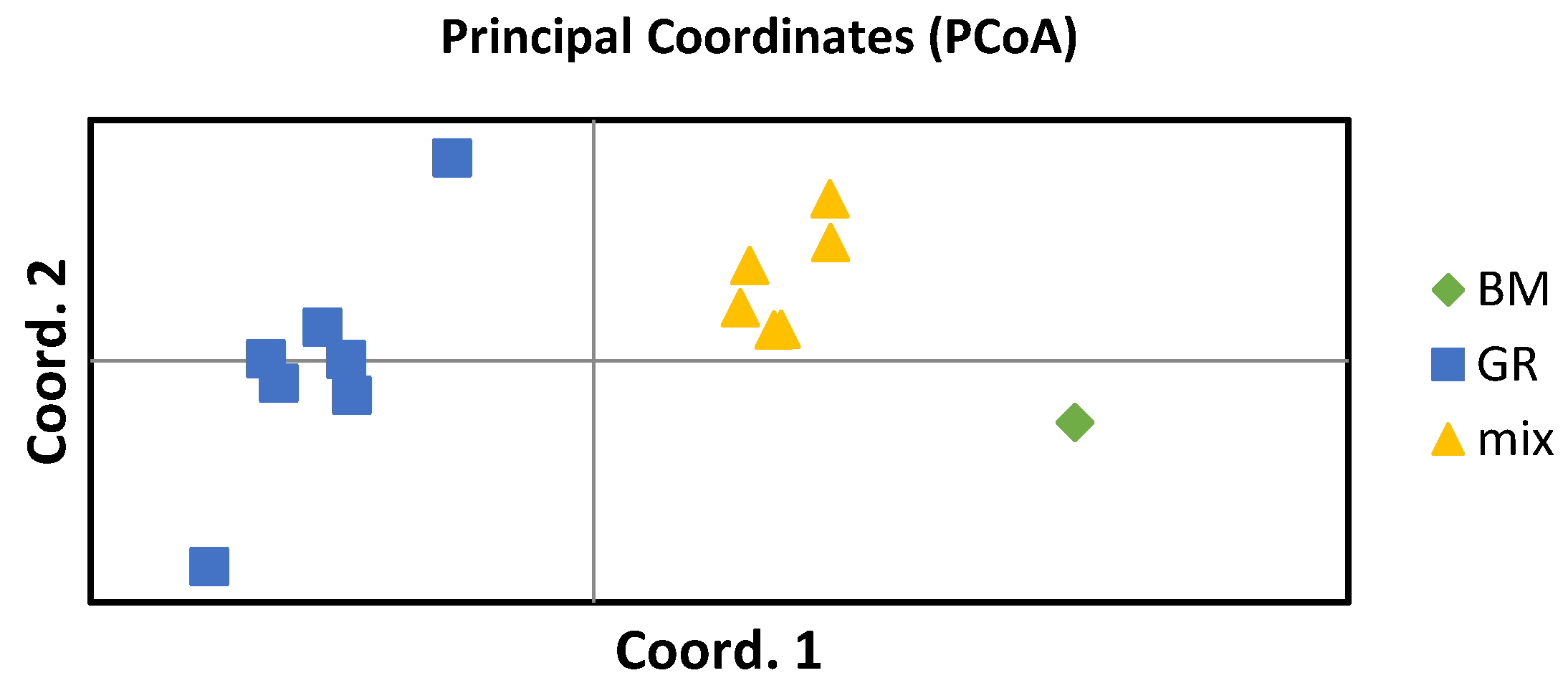

The differentiation between the GR and GR-BM crossbreed puppies was confirmed by Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA). It separated the littermates into two clusters, a group of 5 individuals that were inferred as GR dogs by STRUCTURE analysis and a group of 6 individuals that were inferred as GR-BM crossbreeds, showing clear differentiation between these groups. The sire and dam identified as GR dogs clustered together with the GR puppies and were separated by the Coord.1 axis from the crossbreeds and the BM dog sire, while the BM dog was separated from the crossbreed puppies by the Coord.2 axis (

Figure 6).

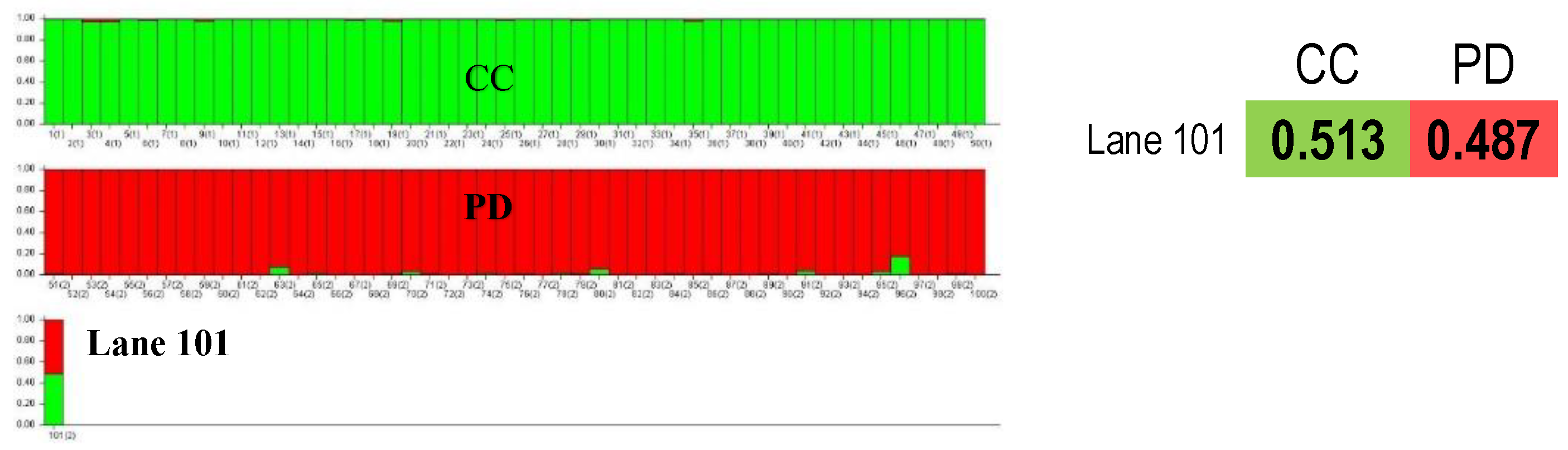

Case Study 2

Chinese Crestepoos are a breed that results from crossing a Chinese Crested Dog with a Poodle. They are popular pets because they are appropriate for many different owners, such as singles, seniors, families with children, and people with allergies. They are both ideal lap dogs and animals to playing. That is why Chinese Crestepoos are very popular which causes the possibility of making a breed mistake, that is sometimes also intended. Case 2 concerns a puppy bought as a Chinese Crested Dog, however with his growth its appearance was different from that of the CC (

Figure 2). DNA profile analysis in 21 microsatellite loci in the puppy and its father excluded its origin from the indicated father. In 4 loci: AHTh171, Fh2848, INU005, and INU055 (Supplementary,

Table S2) the identified alleles were not consistent in the offspring and its father, which excludes the relationship of these dogs. Material from the mother was unavailable. In addition, the genetic structure analysis conducted in the STRUCTURE program showed that the tested puppy was assigned to both the Chinese Crested breed with a probability of 51% and to the Poodle breed with a probability of 49% (

Figure 7 lane 101). The indicated father of the puppy showed a structure consistent with the Crested at a level of > 98% (

Figure 7 lane 50).

The analysis of the puppy and his alleged father, who on the base DNA profiling was excluded as a father, was confirmed by PCoA (

Figure 8). PCoA analysis separated the samples from PD and CC breeds into two clear clusters separated by a Coord.1, and a sample corresponding to the putative hybrid dog - Chinese Crestepoos was located between them (

Figure 8).

4. Conclusions

Application of the study STR panel and the model-based Bayesian clustering method implemented in the STRUCTURE software to breed assignment proved sufficient to clearly define 4 separate genetic clusters for the 4 dog breeds. It that can be successfully used to identify dog hybrid breeds. The result obtained was confirmed using the principal coordinates - PCoA analysis. In case of both studies, DNA profiling allowed to determine the parentage of the puppies after their parents, or to exclude the dog's father. In addition, the obtained results confirmed the correct inference of the belonging of the examined dogs to the breed.

Given that in both cases dogs were correctly assigned to the breed using 21 microsatellite markers (ISAG) routinely used for pedigree testing, it can be concluded, that our approach proved appropriate and that this panel can be successfully used in the identification of the breed and diagnosis of hybrid breeds in different breeds of dogs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary material contains Table S1 and Table S2 with the canine DNA profiles obtained for case 1 and case 2, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R, M.P.; methodology, A.R, A.S.; software, A.R.; formal analysis, A.R, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R. and M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dog Owners for their cooperation. Special thanks for sharing the photos.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ackerman, L.; Milne, E.G.; Bell, J.S.; Oberbauer, A.M.; Nicholas, J.C.; Boss, N.; Englar, R.E.; Grubb, T.; Dowling, P.; Burns, K.M. and Haeussler, D.J., Jr. In Pet-Specific Care for the Veterinary Team, L. Ackerman. Hereditary Considerations, 1002. [Google Scholar]

- Doberman Pinscher History: From Guard Dog to Showman. Available online: https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/dog-breeds/doberman-pinscher-history/ (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Kromfohrlander-The Youngest Breed in Germany. Available online: https://caninechronicle.com/dog-show-history/remembering-our-past%E2%80%8E/kromfohrlander-the-youngest-breed-in-germany (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- How accurate are dog DNA tests? We unleash the truth. Jenny Cowley, Travis Dhanraj. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/marketplace-dog-dna-test-1.6763274 (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- ISAG Conference 2014, Xi’an, China. Applied Genetics of Companion Animals. Available online: https://www.isag.us/Docs/AppGenCompAnim2014_cor.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2014).

- Goleman, M.; Balicki, I.; Radko, A.; Jakubczak, A.; Fornal, A. Genetic diversity of the Polish Hunting Dog population based on pedigree analyses and molecular studies. Livest. Sci. 2019, 229, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radko, A.; Podbielska, A. Microsatellite DNA Analysis of Genetic Diversity and Parentage Testing in the Popular Dog Breeds in Poland. Genes 2021, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, H.G.; Kim, L.V.; Sutter, N.B.; Carlson, S.; Lorentzen, T.D.; Malek, T.B.; Johnson, G.S.; DeFrance, H.B.; Ostrander, E.A.; Kruglyak, L. Genetic structure of the purebred domestic dog. Science 2004, 21;304 (5674):1160-4. [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.E.; Amorim, I.R.; Ginja, C.; Gomes, M.; Godinho, I.; Simões. F.; Oom, M.; Petrucci-Fonseca, F.; Matos, J.; Bruford, M.W.; Molecular structure in peripheral dog breeds: Portuguese native breeds as a case study. Anim Genet. 2009 40(4):383-92. [CrossRef]

- Berger, B.; Berger, C.; Heinrich, J., Niederstätter, H., Hecht, W., Hellmann, A., ... & Parson, W. Dog breed affiliation with a forensically validated canine STR set. Forensic Science International: Genetics. 2018, 37, 126-134.

- García, L.S.A.; Vergara, A.M.C.; Herrera, P.Z.; Puente, J.M.A.; Barro, Á.L.P.; Dunner, S.; Marques, C.S.J.; Bermejo, J.V.D.; Martínez, A.M. Genetic Structure of the Ca Rater Mallorquí Dog Breed Inferred by Microsatellite Markers. Animals 2022, 12 (20):2733. [CrossRef]

- Perfilyeva, A.; Bespalova, K.; Bespalov, S.; Begmanova, М.; Kuzovleva, Y.; Zhaniyazov, Z.; et al. Kazakh national dog breed Tazy: What do we know? PLoS ONE 2023, 18(3): e0282041. [CrossRef]

- Pallotti, S.; La Terza, A.; De Cosmo, A.; Pediconi, D.; Pazzaglia, I,; Nocelli, C.; Renieri, C. Genetic variability of the short-haired and rough-haired Segugio Italiano dog breeds andtheir genetic distance from the other related Segugiobreeds. Ital J Anim Sci. 2017, 16(4): 531–537.

- Vychodilova, L.; Necesankova, M.; Albrechtova, K.; Hlavac, J.; Modry, D.; Janova, E.; et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of African village dogs based on microsatellite and immunity-related molecular markers. PLoS ONE 2018, 13 (6): e0199506.

- Goleman, M.; Balicki, I.; Radko, A.; Rozempolska-Rucinska, I.; Zieba, G. Pedigree and Molecular Analyses in the Assessment of Genetic Variability of the Polish Greyhound. Animals 2021, 11, 353. [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Roychoudhury, A.K. Sampling variances of heterozygosity and genetic distance. Genetics 1974, 76, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S. Evolution and the Genetics of Populations; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Botstein, D.; White, R.L.; Skolnick, M.; Davis, R.W. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1980, 32, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, A.; Taylor, S.C.S. Comparisons of three probability formulae for parentage exclusion. Anim. Genet. 1997, 28, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R; Smouse PE.. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research – an update. Bioinformatics 2012 28: 2537–2539.

- Radko, A.; Słota, E. Application of 19 microsatellite DNA markers for parentage control in Borzoi dogs. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2009, 12, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ciampolini, R.; Cecchi, F.; Bramante, A.; Casetti, F.; Presciuttini, S. Genetic variability of the Bracco Italiano dog breed based on microsatellite polymorphism. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 10, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellanby, R.J.; Ogden, R.; Clements, D.N.; French, A.T.; Gow, A.G.; Powell, R.; Corcoran, B.; Schoeman, J.P.; Summers, K.M. Population structure and genetic heterogeneity in popular dog breeds in the UK. Vet. J. 2013, 196, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, M.S.; Hussain, T.; Babar, M.E.; Nadeem, A.; Naseer, M.; Ullah, Z.; Intizar, M.; Hussain, S.M. A panel of microsatellite markers for genetic diversity and parentage analysis of dog breeds in Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2015, 25, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Bigi, D.; Marelli, S.P.; Randi, E.; Polli, M. Genetic characterization of four native Italian shepherd dog breeds and analysis of their relationship to cosmopolitan dog breeds using microsatellite markers. Animal 2015, 9, 1921–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, D.; Marelli, S.P.; Liotta, L.; Frattini, S.; Talenti, A.; Pagnacco, G.; Polli M.; Crepaldi, P. Investigating the population structure and genetic differentiation of livestock guard dog breeds. Animal. 2018, 12(10): 2009-2016. [CrossRef]

- Radko, A.; Rubi´s, D.; Szumiec, A. Analysis of microsatellite DNA polymorphism in the Tatra Shepherd Dog. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2017, 46, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J.N.; Morris, B.G.; Oliveira, D.A.A.; Bernoco, D. DNA testing for parentage verification and individual identification in seven breeds of dogs. Rev. Bras. Reprod. Anim. 2001, 25, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- DeNise S.; Johnston, E.; Halverson, J.; Marshall, K.; Rosenfeld, D.; McKenna, S.; Sharp, T., Edwards, J. Power of exclusion for parentage verification and probability of match for identity in American Kennel Club breeds using 17 canine microsatellite markers. Anim Genet. 2004 35(1):14-7. [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Yang, J.; Li., J.; Xiong, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Deng, Y. Genetic Polymorphism and Relationship Analyses of Standard Poodle and Bichon Frise Groups Based on 19 Short Tandem Repeat Loci. Journal of Forensic Science and Medicine 2023. 9(4): 331-339. [CrossRef]

- Arata, S.; Asahi, A.; Takeuchi, Y.; Mori, Y. Microsatellite loci analysis for individual identification in Shiba Inu. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2016, 78, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampolinia, R.; Cecchi, F.; Paci, G.; Policardo, C.; Spaterna A. Investigation on the egnetic variability of the American Pit Bull Terrier dogs belonging to an Italian breeder using microsatellite markers and genealogical data. Cytology and Genetics 2013, 47(4): 217–221. Allerton Press, Inc.

- Wade, C. M.; Nuttall, R.; Liu, S. Comprehensive analysis of geographic and breed-purpose influence on genetic diversity and inherited disease risk in the Doberman dog breed. Canine Medicine and Genetics 2023, 10:7.

- Leroy, G.; Verrier, E.; Meriaux, J.C. and Rognon, X. Genetic diversity of dog breeds: between-breed diversity, breed assignation and conservation approaches. Animal Genetics, 2009, 40: 333-343. [CrossRef]

- Schelling, C.; Gaillard, C. & Dolf G. Genetic variability of seven dog breeds based on microsatellite markers. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics 2005, 122, 71–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).