Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Apparatus

2.3. Preparation of CDs

2.4. Preparation of CDs@SiO2-MIPs

2.5. Fluorescent Sensing of TC

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of CDs

3.2. Characterization of CDs@SiO2-MIPs

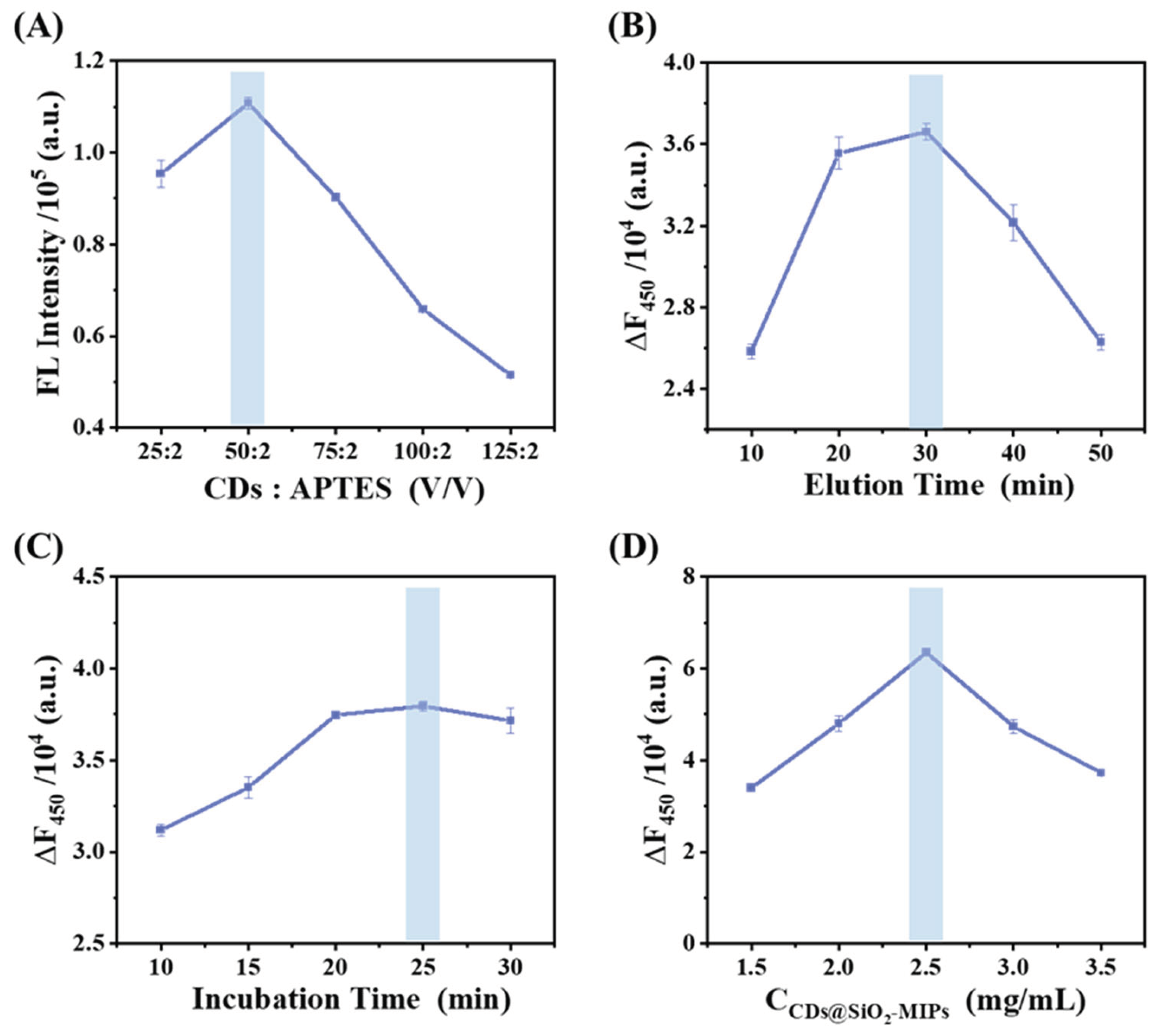

3.3. Optimization of the Sensor

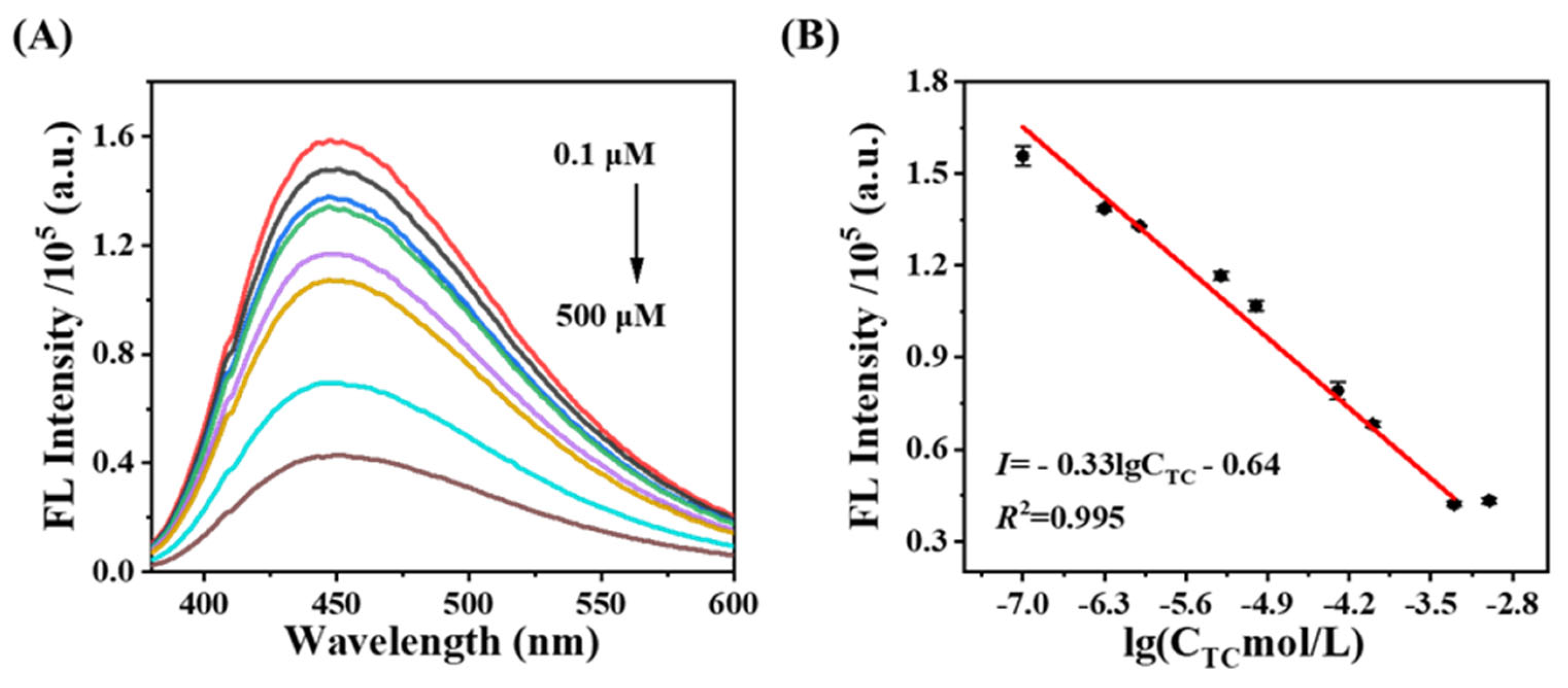

3.4. Fluorescence Detection of CDs@SiO2-MIPs Toward TC

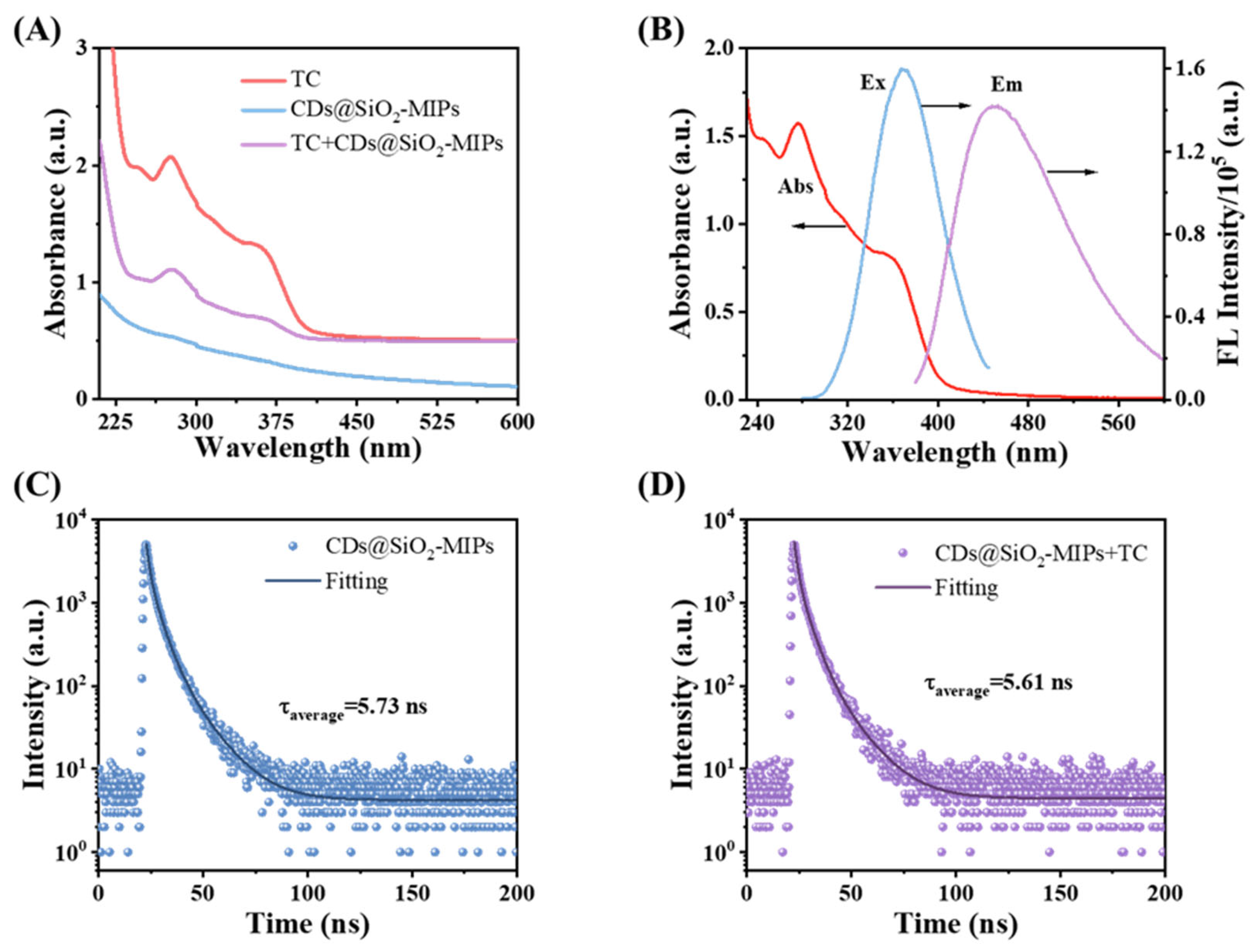

3.5. Mechanism of CDs@SiO2-MIPs for the TC Detection

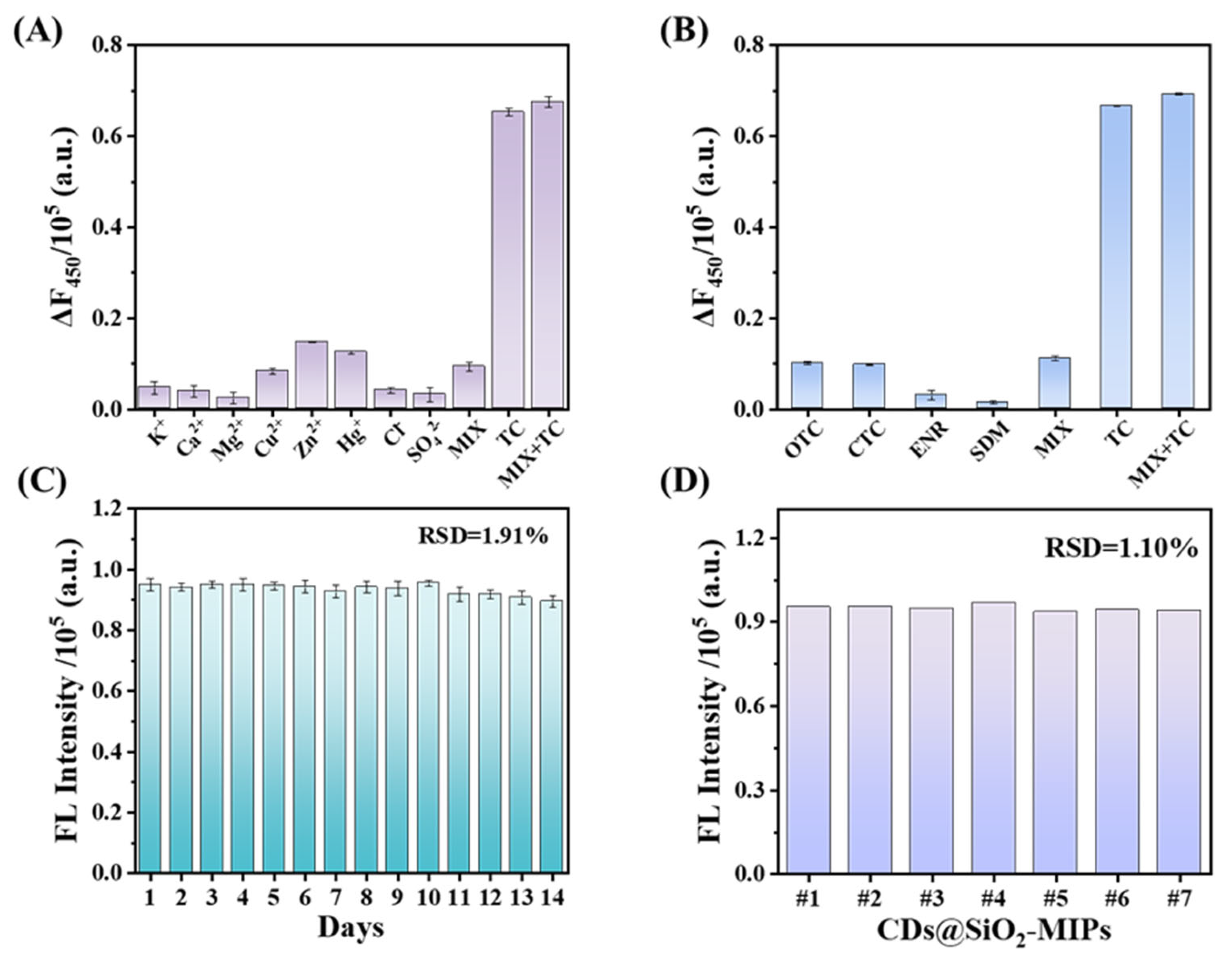

3.6. Selectivity, Anti-Interference Ability and Stability of CDs@SiO2-MIPs Sensor

3.7. Comparison with MIP-Based Sensors for TCs Detection

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, I.; Batra, V.; Kumar Reddy Bogireddy, N.; Torres Landa, S. D.; Agarwal, V. , Detection of organic pollutants, food additives and antibiotics using sustainable carbon dots. Food Chemistry 2023, 406, 135029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xin, D.; Zhang, W.; Luo, D.; Tan, G. , Defects and plasma Ag co-modified S-scheme Ag/NVs-CN/Bi2O2-δCO3 heterojunction with multilevel charge transfer channels for boosting full-spectrum-driven degradation of antibiotics. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 970, 172672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cao, L.; Lu, H.; Huang, Y.; Yang, W.; Cai, Y.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Xu, W. , Custom-printed microfluidic chips using simultaneous ratiometric fluorescence with “Green” carbon dots for detection of multiple antibiotic residues in pork and water samples. Journal of Food Science 2024, 89, 5980–5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Wang, W.; Tan, F.; Xia, H.; Wang, X.; Qiao, X.; Wong, P. K. , Facile one-step synthesis of 3D hierarchical flower-like magnesium peroxide for efficient and fast removal of tetracycline from aqueous solution. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 397, 122877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Chen, H.; Yue, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, M.; Tan, H.; Asiri, A. M.; Alamry, K. A.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. , Metal–organic framework enhances aggregation-induced fluorescence of chlortetracycline and the application for detection. Analytical Chemistry. 2002, 74, 1509 - 1518. [CrossRef]

- Gerd Hamscher, S. S. , Heinrich Höper and Heinz Nau, Determination of persistent tetracycline residues in soil fertilized with liquid manure by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical chemistry, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhu, L.; Tang, H. , Analysis of tetracyclines in chicken tissues and dung using LC–MS coupled with ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Control 2014, 46, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, X.; Bai, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, S.; Han, D.; Ren, S.; Wang, J.; Han, T.; Gao, Y.; Ning, B.; Gao, Z. , Immunosorbent assay based on upconversion nanoparticles controllable assembly for simultaneous detection of three antibiotics. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 406, 124703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Liu, J.; Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, G. , A ratio fluorescence probe by one-stage process for selectivity detection of tetracycline. Optical Materials 2022, 134, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, M.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhe, T.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L. , Antimonene quantum dots as an emerging fluorescent nanoprobe for the pH-mediated dual-channel detection of tetracyclines. Small 2020, 16, 2003429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Hu, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Zou, X.; Shi, J. , A dual-signal fluorescent sensor based on MoS2 and CdTe quantum dots for tetracycline detection in milk. Food Chemistry 2022, 378, 132076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cai, Z. , Ascorbic acid stabilized copper nanoclusters as fluorescent probes for selective detection of tetracycline. Chemical Physics Letters 2020, 759, 138048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Li, S.; Yao, G.; Qu, R.; Yang, W.; Wang, H.; Tan, W.; Yang, M. , Highly photoluminescent tryptophan-coated copper nanoclusters based turn-off fluorescent probe for determination of tetracyclines. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ji, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xu, X.; Bao, L.; Cui, M.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, Z. , A smart Zn-MOF-based ratiometric fluorescence sensor for accurate distinguish and optosmart sensing of different types of tetracyclines. Applied Surface Science 2023, 640, 158442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, Q.; Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, J.-R. , Stable metal–organic frameworks for fluorescent detection of tetracycline antibiotics. Inorganic Chemistry 2022, 61, 8015–8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Hu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zou, X.; Shi, J.; Zheng, K.; Arslan, M. , A portable test strip based on fluorescent europium-based metal–organic framework for rapid and visual detection of tetracycline in food samples. Food Chemistry 2021, 354, 129501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Liang, N.; Hu, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, D.; Zou, X.; Shi, J. , An intrinsic dual-emitting fluorescence sensing toward tetracycline with self-calibration model based on luminescent lanthanide-functionalized metal-organic frameworks. Food Chemistry 2023, 400, 133995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ge, B.; Zhao, H.; Jin, C.; Yan, H.; Zhao, L. , Designing fluorescent covalent organic frameworks through regulation of link bond for selective detection of Al3+ and Ce3+. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2025, 329, 125620. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jin, Q.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Wang, J. , Ratiometric fluorescent sensor based on europium (III)-functionalized covalent organic framework for selective and sensitive detection of tetracycline. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 465, 142819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yu, W.; Huang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, K. , Lignocellulosic biomass-based carbon dots: synthesis processes, properties, and applications. Small 2023, 19, 2304066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Chen, J.-L.; Su, M.-X.; Yan, F.; Li, B.; Di, B. , Phosphate-containing metabolites switch on phosphorescence of ferric ion engineered carbon dots in aqueous solution. RSC Advances 2014, 4, 22318–22323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, T.; Niu, L.; Liu, S. , Recent advances of biomass-derived carbon dots with room temperature phosphorescence characteristics. Nano Today 2024, 56, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Teng, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Yu, H.; Teng, C.; Huang, Z.; Liu, H.; Shao, Q.; Umar, A.; Ding, T.; Gao, Q.; Guo, Z. , Biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots: highly selective fluorescent probe for detecting Fe3+ ions and tetracyclines. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2019, 539, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, B. K.; John, N.; Korah, B. K.; Thara, C.; Abraham, T.; Mathew, B. , Nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots as a highly selective fluorescent and electrochemical sensor for tetracycline. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 2022, 432, 114060. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liao, S.; Bai, Y.; Wu, S. , Carbon dots derived from green jujube as chemosensor for tetracycline detection. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024, 12, 112595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jiang, M.; Chen, L.; Niu, N. , Construction of ratiometric fluorescence MIPs probe for selective detection of tetracycline based on passion fruit peel carbon dots and europium. Microchimica Acta 2021, 188, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korah, B. K.; Chacko, A. R.; Mathew, S.; John, B. K.; Abraham, T.; Mathew, B. , Biomass-derived carbon dots as a sensitive and selective dual detection platform for fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2022, 414, 4935–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Deng, J.; Xie, B.; Zhou, T. , Highly efficient and sensitive detection of tetracycline in environmental water: Insights into the synergistic mechanism of biomass-derived carbon dots and N-methyl pyrrolidone solvent. Talanta 2024, 278, 126512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hao, R.; Li, F.; Tian, S.; Xin, X.; Li, G.; Li, D. , Emulsifying properties of cellulose nanocrystals with different structures and morphologies from various solanaceous vegetable residues. Food Chemistry 2025, 463, 141241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Ran, Y.; Alengebawy, A.; Yang, G.; Jia, S.; Ai, P. , Agro-environmental sustainability of using digestate fertilizer for solanaceous and leafy vegetables cultivation: Insights on fertilizer efficiency and risk assessment. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 320, 115895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Han, W.; Fei, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Dong, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y. , Development of acid hydrolysis-based UPLC–MS/MS method for determination of alternaria toxins and its application in the occurrence assessment in solanaceous vegetables and their products. 2023, 15, 201. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, S.; Yao, B.; Peng, Y.; Gao, C.; Qin, T.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, C.; Quan, W. , Effects of straw return and straw biochar on soil properties and crop growth: A review. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 986763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Wu, X.; Li, J. , Molecular imprinting: perspectives and applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2016, 45, 2137–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ma, Y.; Fan, C.; Kang, J.; Ma, S. , A highly efficient molecularly imprinted fluorescence sensor for selective and sensitive detection of tetracycline antibiotic residues in pork. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2024, 133, 106367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, T.; Wang, S.; Yan, Y. , Mesoporous silica-based molecularly imprinted fluorescence sensor for the ultrafast and sensitive recognition of oxytetracycline. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 108, 104427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Gao, L.; Wang, J.; Pan, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X. , A precise and efficient detection of Beta-Cyfluthrin via fluorescent molecularly imprinted polymers with ally fluorescein as functional monomer in agricultural products. Food Chemistry 2017, 217, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukunzi, D.; Habimana, J. d. D.; Li, Z.; Zou, X. , Mycotoxins detection: view in the lens of molecularly imprinted polymer and nanoparticles. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 63, 6034–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, M.; Ostovan, A.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Choo, J.; Chen, L. , Molecular imprinting: green perspectives and strategies. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 2100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostovan, A.; Arabi, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. , Greenificated molecularly imprinted materials for advanced applications. Advanced Materials 2022, 34, 2203154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkin, K.; Zheng, Y.; Bei, Y.; Ma, X.; Che, W.; Shang, Q. , Construction of dual-channel ratio sensing platform and molecular logic gate for visual detection of oxytetracycline based on biomass carbon dots prepared from cherry tomatoes stalk. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 464, 142552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Fu, L.; Yin, C.; Wu, M.; Liu, H.; Niu, N.; Chen, L. , Construction of biomass carbon dots@molecularly imprinted polymer fluorescent sensor array for accurate identification of 5-nitroimidazole antibiotics. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2022, 373, 132716. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Liao, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, H. , A smartphone-combined ratiometric fluorescence molecularly imprinted probe based on biomass-derived carbon dots for determination of tyramine in fermented meat products. Food Chemistry 2024, 454, 139759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Arkin, K.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Bei, Y.; Liu, D.; Shang, Q. , Preparation of a composite material based on self-assembly of biomass carbon dots and sodium alginate hydrogel and its green, efficient and visual adsorption performance for Pb2+. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 106921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Fan, Z. , Synthesis of fluorescent probe based on molecularly imprinted polymers on nitrogen-doped carbon dots for determination of tobramycin in milk. Food Chemistry 2023, 416, 135792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Fang, G.; Pan, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. , One-pot synthesis of carbon dots-embedded molecularly imprinted polymer for specific recognition of sterigmatocystin in grains. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2016, 77, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, W.; Ma, J.; Jiang, H. , A carbon dots probe for specific determination of cysteine based on inner filter effect. Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2022, 77, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, S.; Yang, J.; zhang, H.; Yan, J.; Hu, X. , Fluorescent carbon dots for glyphosate determination based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer and logic gate operation. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2017, 242, 545-553. [CrossRef]

- Jalili, R.; Khataee, A.; Rashidi, M.-R.; Razmjou, A. , Detection of penicillin G residues in milk based on dual-emission carbon dots and molecularly imprinted polymers. Food Chemistry 2020, 314, 126172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Du, Q. , Metal-organic framework modified molecularly imprinted polymers-based sensor for fluorescent sensing of tetracycline in milk. Journal of Molecular Structure 2024, 1303, 137598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Song, Z.; Pan, J.; Yan, Y.; Cao, Z.; Wei, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, J.; Dai, J.; Meng, M.; Yu, P. , A simple and sensitive surface molecularly imprinted polymers based fluorescence sensor for detection of λ-Cyhalothrin. Talanta 2014, 125, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Quan, X.; Chen, S. , Electrochemical determination of tetracycline using molecularly imprinted polymer modified carbon nanotube-gold nanoparticles electrode. Electroanalysis 2011, 23, 1863–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, T.; Chou, R.; Liu, A.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Hu, K.; Zou, L. , Construction of a molecularly imprinted sensor modified with tea branch biochar and its rapid detection of norfloxacin residues in animal-derived foods. Foods, 2023, 12, 544. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Liu, G.; Wang, G.; Liu, M.; Pan, L.; He, J.; Li, K. , Surface-molecularly imprinted ratiometric fluorescence sensor for fast, sensitive and selective determination of rhodamine 6G. Dyes and Pigments 2023, 219, 111602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Hao, T.; Xu, Y.; Lu, K.; Li, H.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Z. , Facile polymerizable surfactant inspired synthesis of fluorescent molecularly imprinted composite sensor via aqueous CdTe quantum dots for highly selective detection of λ-cyhalothrin. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2016, 224, 315-324. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).