Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- A universal and systematic methodology for the automatic determination of DH parameters for any serial robot, using only the geometric information of the joint axes in its zero configuration without requiring prior kinematic data.

- 2.

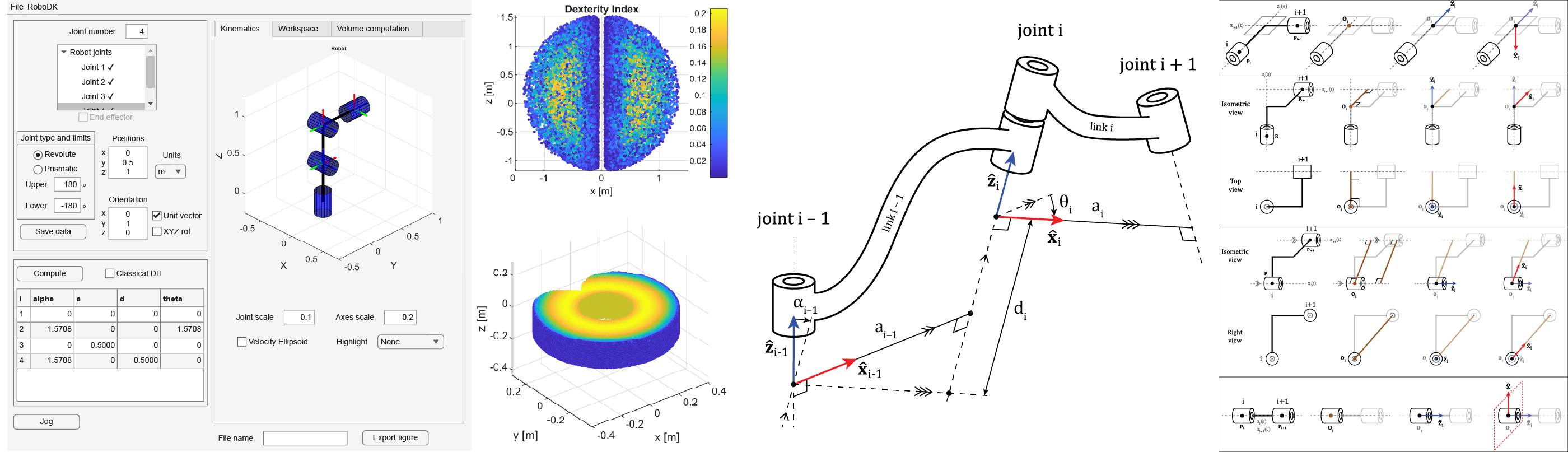

- A novel MATLAB-based kinematics toolbox that implements this methodology, providing user-friendly tools for computing parameters using both classical and modified DH conventions.

- 3.

- Integrated performance analysis features, including the visualization of the robot’s workspace, manipulability, and dexterity, alongside a novel numerical method for accurately computing the total workspace volume.

- 4.

- Seamless integration with RoboDK, enabling the direct import, analysis, and modification of a wide range of industrial and research robot models.

2. Methodology

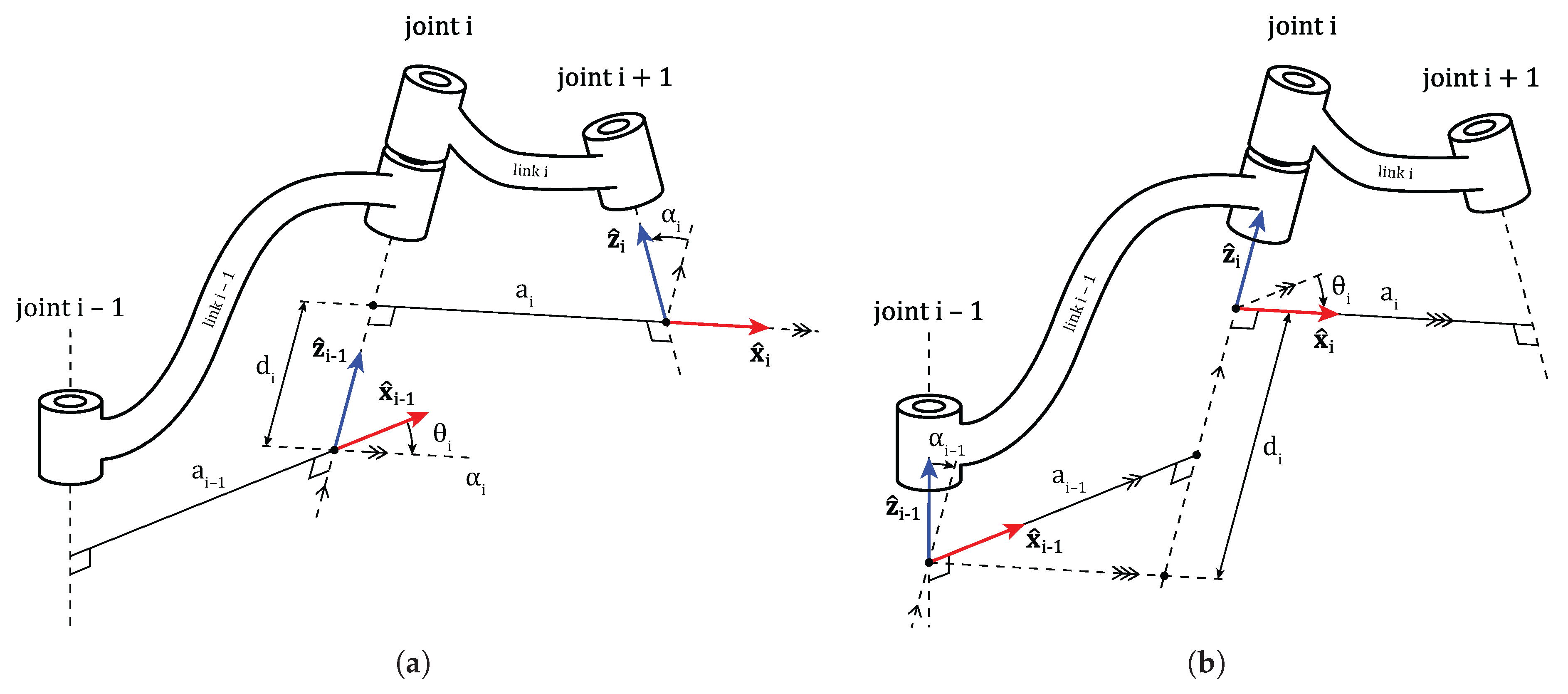

2.1. The Denavit-Hartenberg Conventions

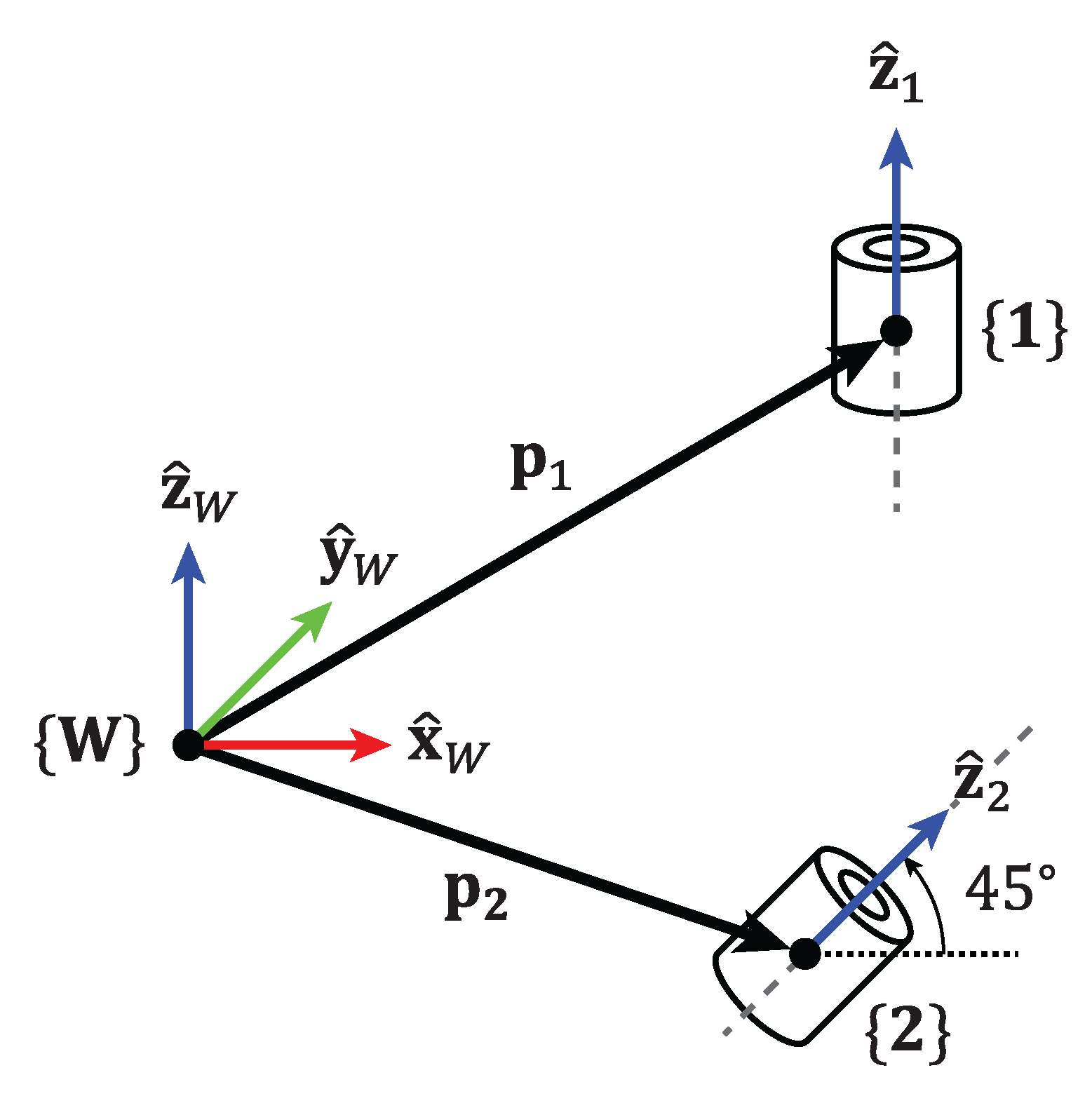

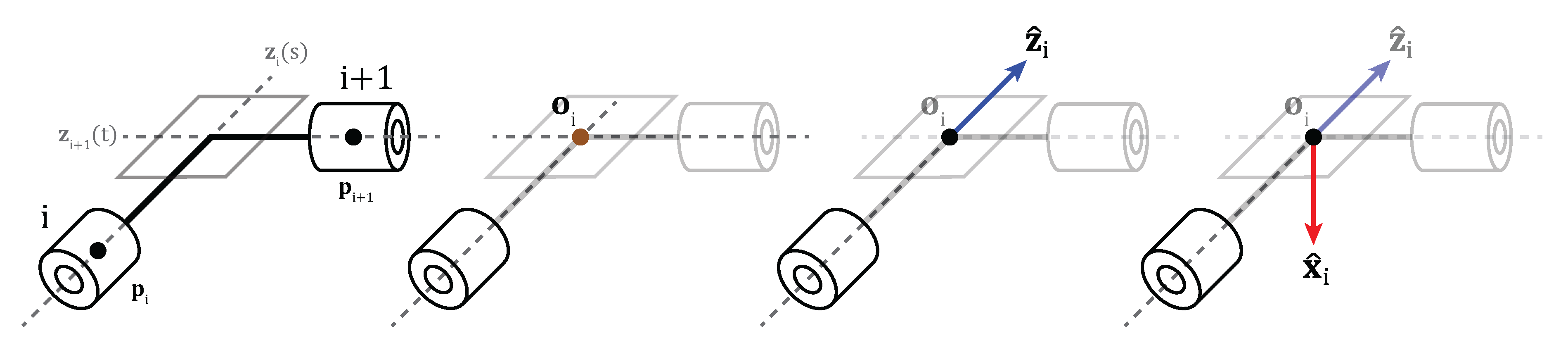

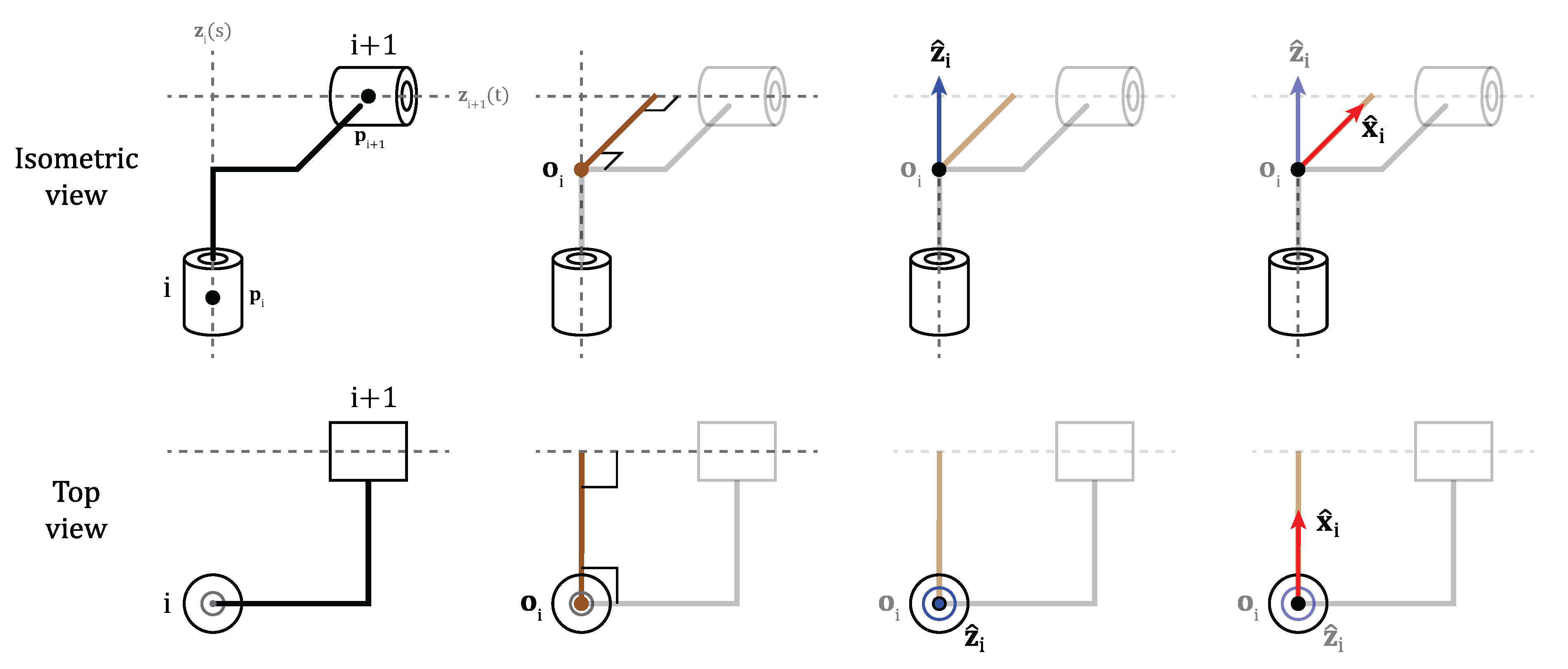

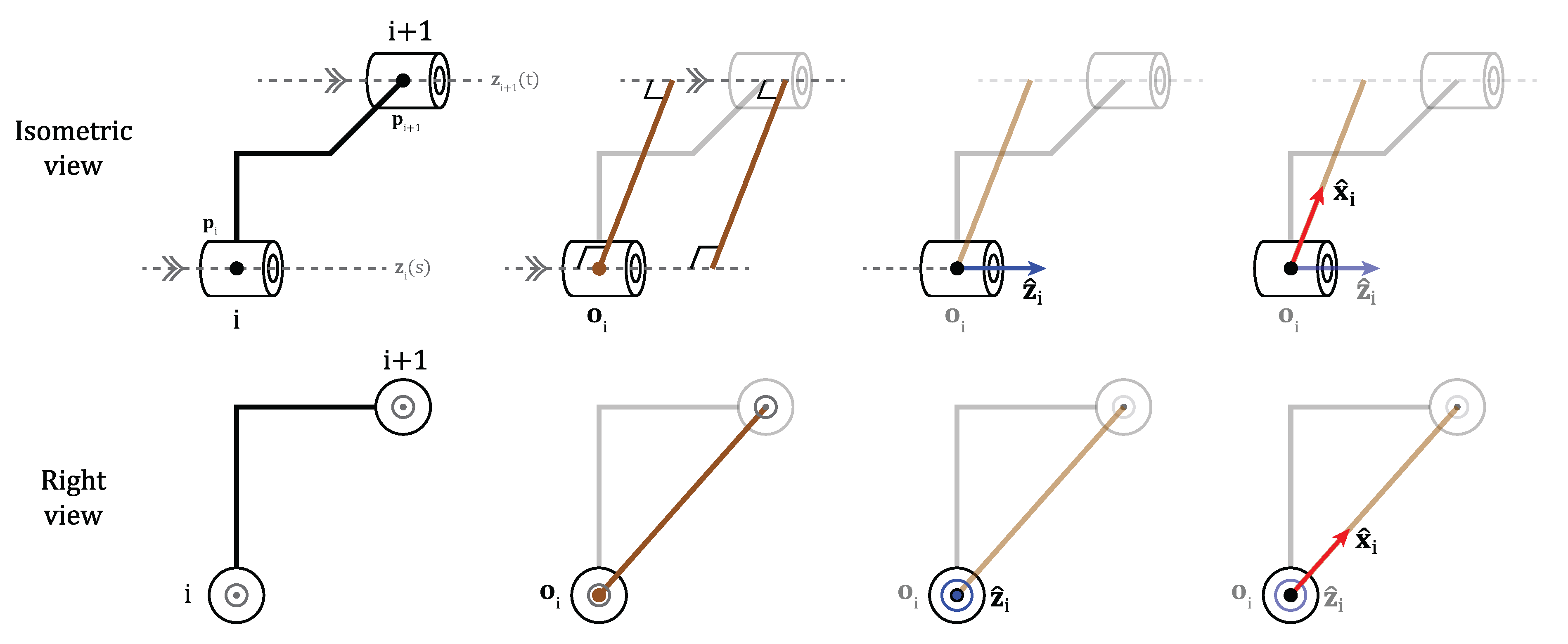

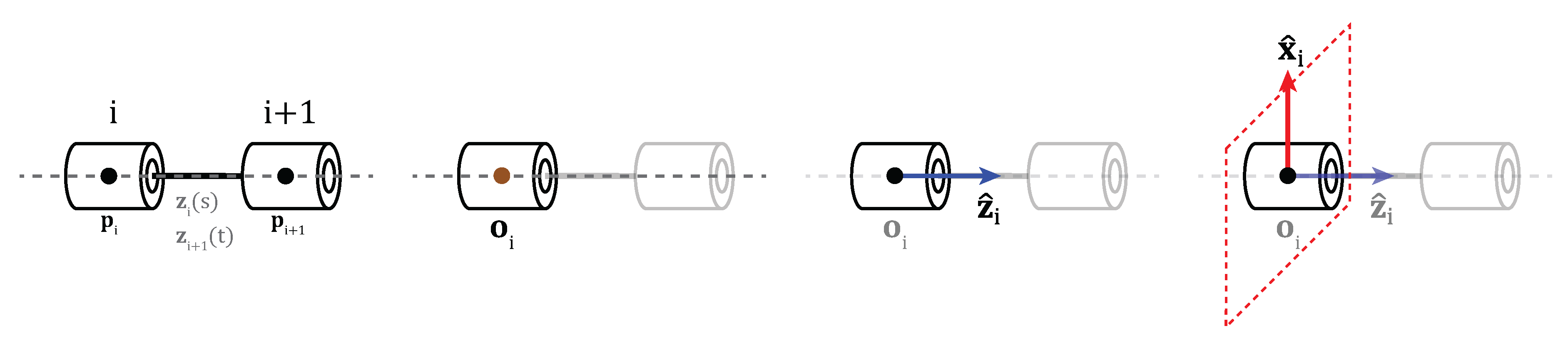

2.2. Universal Frame Assignment Methodology

-

Condition C1 (Axis Alignment):This condition holds when the joint axes are parallel or collinear.

-

Condition C2 (Coplanarity):This condition holds true if the joint axes lie in the same plane.

-

Condition C3 (Axis Coincidence):This condition holds if the origin of joint lies along the axis of joint i.

2.3. Algorithm for Automatic DH Parameter Determination

| Algorithm 1 Axis Relation Classification |

|

| Algorithm 2 Find MDH-Related Frames from Axis Relations |

|

| Algorithm 3 Compute MDH Table from Frame Triplets |

|

2.4. Workspace Analysis and Volume Computation

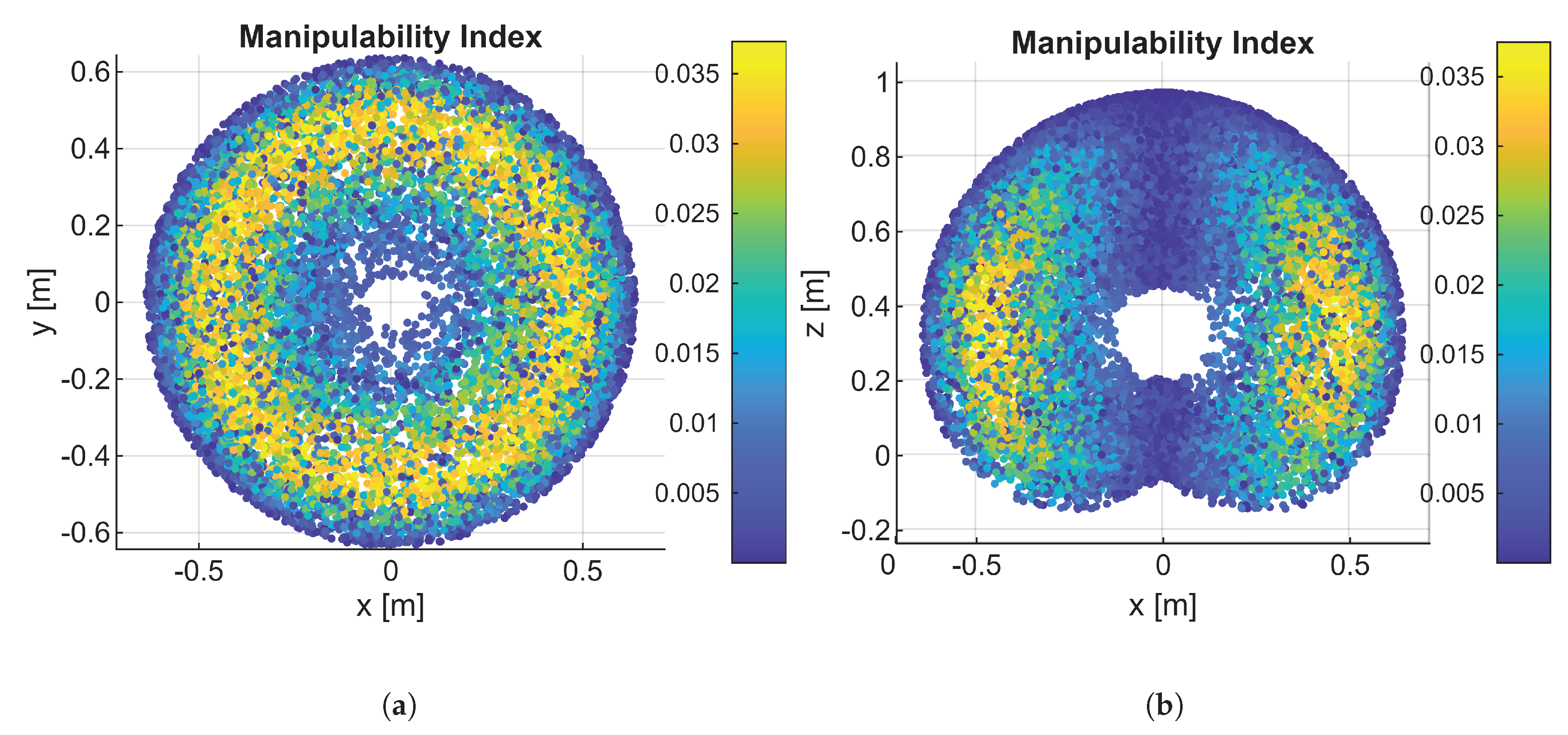

-

The manipulability index (), based on Yoshikawa’s work, quantifies the robot’s ability to move its end-effector in any direction. It is calculated as the square root of the determinant of .A higher value indicates greater ease of motion, whereas a value of zero corresponds to a singularity.

-

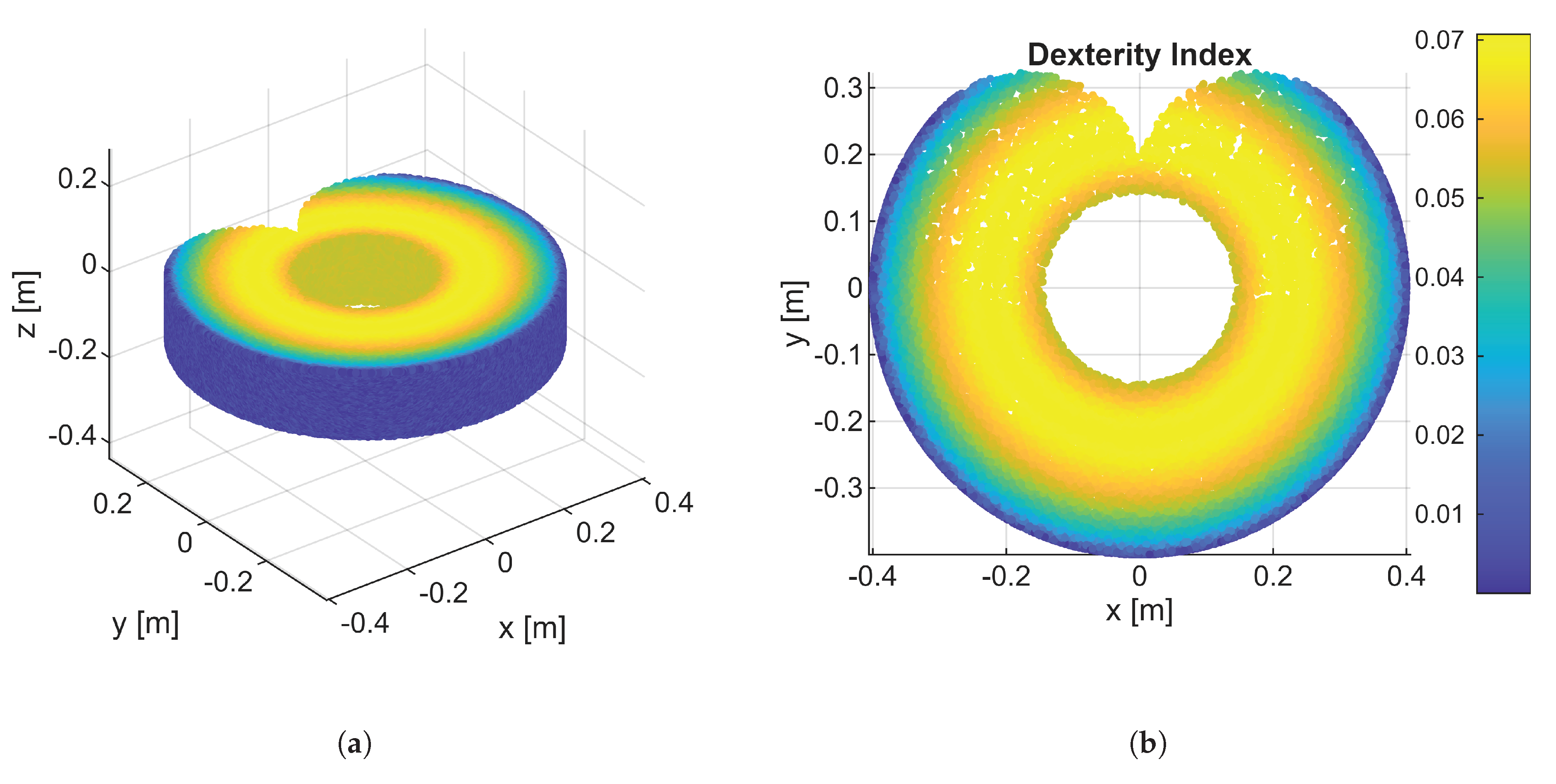

The dexterity index, which measures the isotropy of the manipulator’s motion, is calculated as the ratio of the minimum singular value () to the maximum singular value () of the Jacobian matrix. This is equivalent to the inverse of the Jacobian condition number.A value close to 1 indicates that the end effector can move with equal ease in all directions, whereas a value close to 0 suggests that the robot is near a singularity.

- 1.

- Slicing: The 3D workspace point cloud is partitioned into a series of thin, parallel slices of a uniform thickness, , along the z-axis.

- 2.

- 2D Projection and Boundary Finding: For each slice, the points contained within it are projected onto the x-y plane. An alpha shape is then generated from the 2D point set. The alpha shape algorithm creates a tight, potentially non-convex boundary that accurately envelops the points, effectively capturing the shape of a specific cross-section, including any internal holes. The alphaRadius is a critical parameter that controls the tightness of the boundary.

- 3.

- Area and Volume Summation: The area () of the alpha shape for each slice i is calculated. The volume of the slice () is then approximated as . The total workspace volume is estimated by summing the volumes of all slices as follows:

| Algorithm 4 ForwardKinematics (Modified DH, cumulative) |

|

| Algorithm 5 Jacobian computation |

|

| Algorithm 6 Workspace Sampling with MDH Kinematics |

|

| Algorithm 7 Workspace Volume Computation |

|

2.5. Linking the toolbox with RoboDK

3. Results

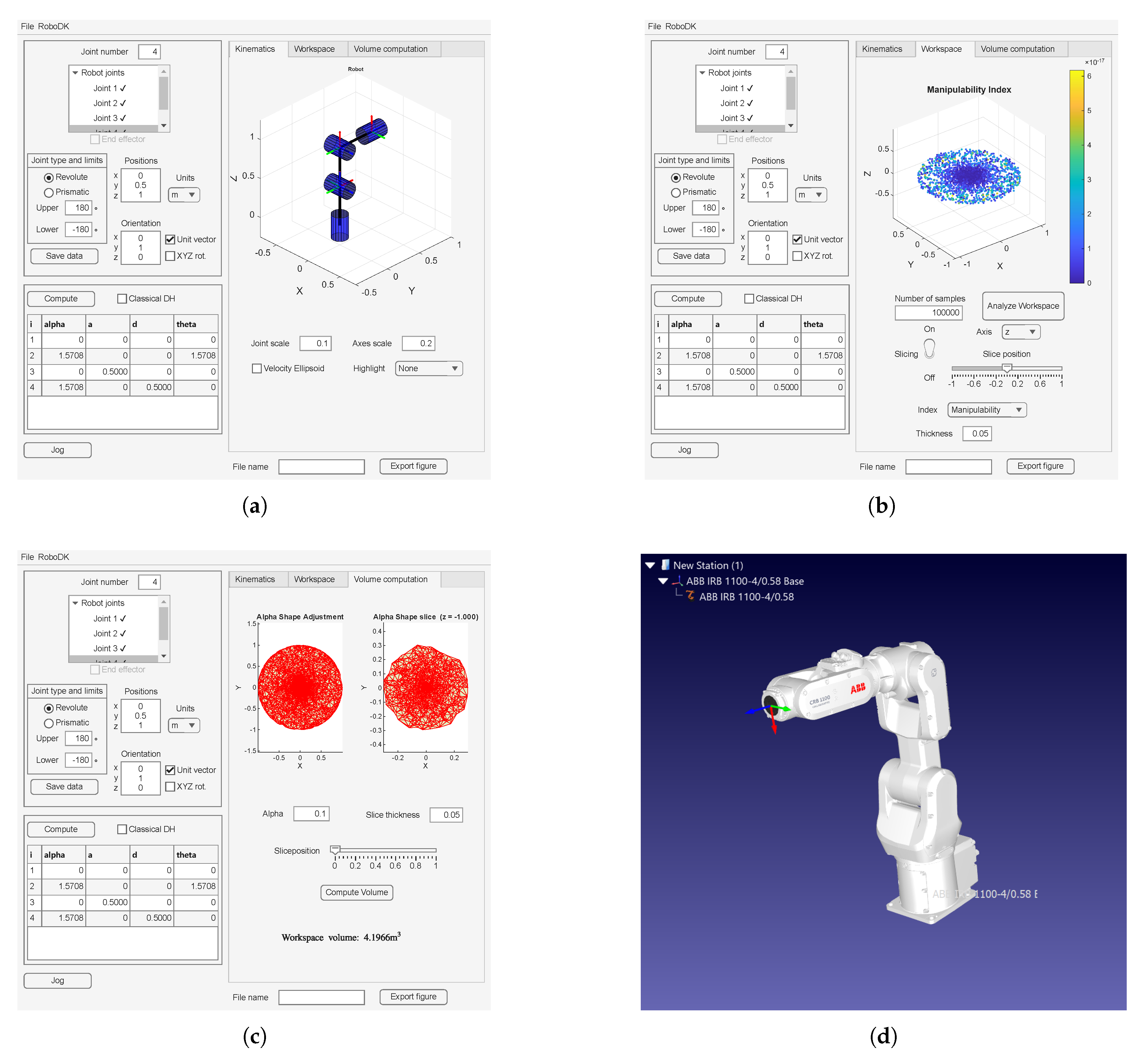

3.1. Overview of the Kinematics Toolbox

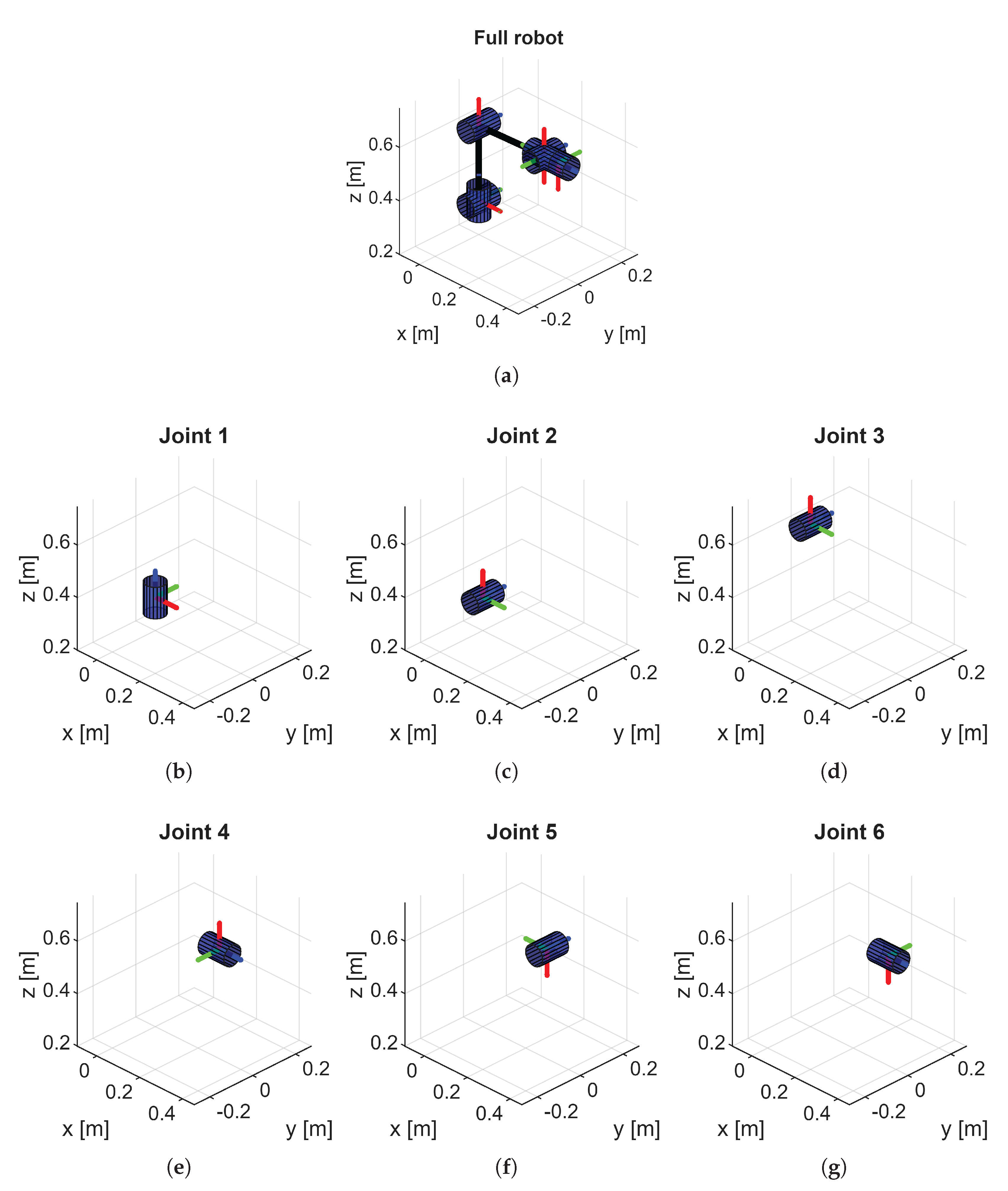

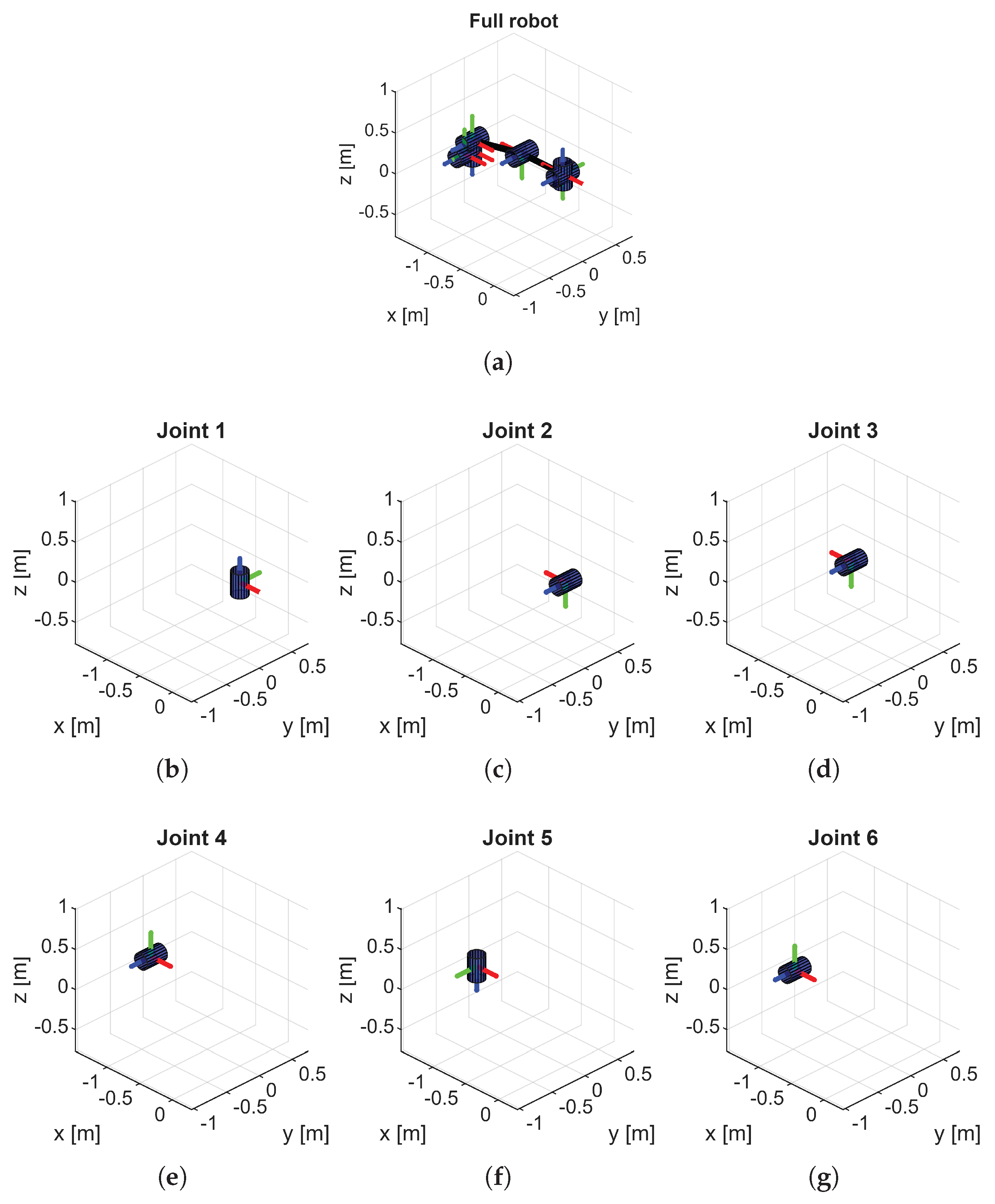

3.2. Frame Placement and DH Parameters

3.3. Workspace Analysis

3.4. Volume Computation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A Proof of Theorem 1

References

- Denavit, J.; Hartenberg, R.S. A Kinematic Notation for Lower-Pair Mechanisms Based on Matrices. Journal of Applied Mechanics 1955, 22, 215–221. [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.P. Robot manipulators: mathematics, programming, and control, 9. printing ed.; The MIT Press series in artificial intelligence, MIT Pr: Cambridge, Mass., 1992.

- Spong, M.W.; Vidyasagar, M. Robot dynamics and control; John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- Siciliano, B., Ed. Robotics: modelling, planning and control; Advanced textbooks in control and signal processing, Springer: London, 2009.

- Craig, J.J. Introduction to robotics: mechanics and control, fourth edition ed.; Pearson: NY NY, 2018.

- Corke, P.I. Robotics, vision and control: fundamental algorithms in MATLAB, 2nd revised, extended and updated ed ed.; Number 118 in Springer tracts in advanced robotics, Springer: Cham, 2017.

- Siciliano, B. Springer Handbook of Robotics, 2nd ed ed.; Springer Handbooks Ser, Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, 2016.

- A Chennakesava Reddy. DIFFERENCE BETWEEN DENAVIT - HARTENBERG (D-H) CLASSICAL AND MODIFIED CONVENTIONS FOR FORWARD KINEMATICS OF ROBOTS WITH CASE STUDY. International Conference on Advanced Materials and manufacturing 2014. Publisher: Unpublished, . [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, H.; Xu, M.; Tang, Y.; Yao, J.; Yan, X.; Li, M. Research on the Relationship between Classic Denavit-Hartenberg and Modified Denavit-Hartenberg. In Proceedings of the 2014 Seventh International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design, Hangzhou, China, December 2014; pp. 26–29. [CrossRef]

- Corke, P. A Simple and Systematic Approach to Assigning Denavit–Hartenberg Parameters. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2007, 23, 590–594. [CrossRef]

- Faria, C.; Vilaca, J.L.; Monteiro, S.; Erlhagen, W.; Bicho, E. Automatic Denavit-Hartenberg Parameter Identification for Serial Manipulators. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019 - 45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, October 2019; pp. 610–617. [CrossRef]

- Sung, M.; Choi, Y. Algorithmic Modified Denavit–Hartenberg Modeling for Robotic Manipulators Using Line Geometry. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 4999. [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, F.; Borst, C.; Hirzinger, G. Capturing robot workspace structure: representing robot capabilities. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, October 2007; pp. 3229–3236. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lu, K.; Li, X.; Zang, Y. Accurate Numerical Methods for Computing 2D and 3D Robot Workspace. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2011, 8, 76. [CrossRef]

- Hayati, S. Robot arm geometric link parameter estimation. In Proceedings of the The 22nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. IEEE, 1983, pp. 1477–1483. [CrossRef]

- Abderrahim, M.; Whittaker, A. Kinematic model identification of industrial manipulators. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2000, 16, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Chittawadigi, R.G. Geometric Model Identification of a serial Robot. In Proceedings of the IFToMM International Symposium on Robotics and Mechatronics. Research Publishing Services, 2013, pp. 730–738. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.A.; Chittawadigi, R.G.; Udai, A.D.; Saha, S.K. Identification of Denavit-Hartenberg Parameters of an Industrial Robot. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Conference on Advances In Robotics, Pune India, July 2013; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Klimchik, A.; Caro, S.; Furet, B.; Pashkevich, A. Geometric calibration of industrial robots using enhanced partial pose measurements and design of experiments. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2015, 35, 151–168. [CrossRef]

- Messay, T.; Ordóñez, R.; Marcil, E. Computationally efficient and robust kinematic calibration methodologies and their application to industrial robots. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2016, 37, 33–48. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.A.; Boby, R.A.; Saha, S.K. A geometric approach for kinematic identification of an industrial robot using a monocular camera. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2019, 57, 329–346. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Song, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, Q. A novel method to identify DH parameters of the rigid serial-link robot based on a geometry model. Industrial Robot: the international journal of robotics research and application 2021, 48, 157–167. [CrossRef]

- Icli, C.; Stepanenko, O.; Bonev, I. New Method and Portable Measurement Device for the Calibration of Industrial Robots. Sensors 2020, 20, 5919. [CrossRef]

- Boby, R.A.; Klimchik, A. Combination of geometric and parametric approaches for kinematic identification of an industrial robot. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2021, 71, 102142. [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, W.; Ke, Y. A two-step method for kinematic parameters calibration based on complete pose measurement—Verification on a heavy-duty robot. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2023, 83, 102550. [CrossRef]

- Žlajpah, L.; Petrič, T. Kinematic calibration for collaborative robots on a mobile platform using motion capture system. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2023, 79, 102446. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Gao, G.; Na, J.; Zhang, F. A parameter separation-based method for kinematic identification of industrial robots without prior kinematic information. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2025, 96, 103037. [CrossRef]

- Karhan, H. AutoMDH GitHub, 2025. 2025-09-01, https://github.com/haydarkarhan/ automdh/tree/mdpi-submission.

- UR. UR10e Kinematic Parameters, 2025. 2025-09-01, https://www.universal-robots.com/ articles/ur/application-installation/dh-parameters-for-calculations-of-kinematics-and-dynamics/.

| Geometric Relationship | C1 | C2 | C3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intersecting | False | True | – |

| Skew | False | False | – |

| Parallel | True | – | False |

| Collinear | True | – | True |

| Modified (RoboDK) | Modified (Toolbox) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint | [°] | [m] | [m] | [°] | [°] | [m] | [m] | [°] |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.3270 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3270 | 0 |

| 2 | -90 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -90 | -90 | 0 | 0 | -90 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.2800 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0 | 0.2800 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | -90 | 0.0100 | 0.3000 | 0 | -90 | 0.0100 | 0.3000 | 0 |

| 5 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 180 |

| 6 | -90 | 0.0000 | 0.0640 | 180 | 90 | 0 | 0.0640 | 0 |

| Classical (Manufacturer) | Classical (Toolbox) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint | [°] | [m] | [m] | [°] | [°] | [m] | [m] | [°] |

| 1 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.1807 | 0 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.1807 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | -0.6127 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0 | 0.6126 | 0.0000 | 180 |

| 3 | 0 | -0.5716 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0 | 0.5713 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| 4 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.1742 | 0 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.1742 | -180 |

| 5 | -90 | 0.0000 | 0.1199 | 0 | -90 | 0.0000 | 0.1198 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.1166 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.1166 | 0 |

| Modified (RoboDK) | Modified (Toolbox) | |||||||

| Joint | [°] | [m] | [m] | [°] | [°] | [m] | [m] | [°] |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.1807 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.1807 | 0 |

| 2 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 180 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 180 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.6126 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0 | 0.6126 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0.5713 | 0.1742 | 0 | 0 | 0.5713 | 0.1742 | -180 |

| 5 | -90 | 0.0000 | 0.1198 | 0 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.1198 | 0 |

| 6 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.1166 | 180 | -90 | 0.0000 | 0.1166 | 0 |

| Slot Robot | Sphere Robot | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint | [°] | [m] | [m] | [°] | [°] | [m] | [m] | [°] |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0 |

| 2 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 90 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 90 |

| 3 | 0 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0 | 2.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| Robot Type | # Samples |

Slice Thickness [m] |

(Alpha-shape) |

Comp. Volume [m3] |

Real Volume [m3] |

Error [ % ] |

| Slot robot | 1,000k | 0.025 | ∞ | 41.1327 | 39.6795 | 3.5331 |

| Sphere robot | 1,000k | 0.020 | 0.35 | 108.3069 | 108.9085 | 0.5524 |

| Epson T3-401s | 500k | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.058545 | 0.059873 | 2.2180 |

| ABB IRB 1400 | 1,000k | 0.0075 | 0.065 | 1.0186 | — | — |

| UR10e | 1,000k | 0.05 | 0.05 | 10.1194 | — | — |

| KUKA iiwa 7 | 5,000k | 0.01 | 0.1 | 3.0892 | — | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).