1. Introduction

The incidence of weeds in agronomic crops causes significant reductions in the profitability of agricultural production systems [

1]. On the one hand, weeds compete with arable plants for soil nutrients, water, and light [

2,

3,

4,

5]. On the other hand, they can affect harvesting operations, the quality of harvested grain, and serve as a source of insects and diseases harmful to crops [

6]. Understanding these negative aspects is essential because it allows for the development of targeted and efficient weed control strategies, reducing the negative impacts on crop yields and quality. Furthermore, it aids in the optimization of resource use, minimizing the environmental footprint of agricultural practices.

In the last decades, control strategies were mainly based on the use of herbicides, particularly glyphosate [

7,

8,

9]. However, the reduced availability of products to selectively control weeds, the increase in the frequency of individuals resistant and tolerant to the application of certain herbicides, as well as the growing pressure to reduce the use of agrochemicals due to their harmful effects on the environment, make it necessary to optimize the application of control measures within a framework of more rational control strategies [

10]. Despite the progress made in understanding the key processes of weeding - such as dispersal, competition, and establishment of weeds - in recent decades, the persistence of the problem in current agricultural systems highlights our inability to predict and control this phenomenon with sufficient precision [

11]. This is partly due to our lack of knowledge regarding various aspects related to the regulation of weeding processes [

3,

12]. However, the possibility of designing more effective integrated weed management systems depends not only on gathering this knowledge, but also on the ability to predict in time and space, and under different environmental and management practice scenarios, the intensity with which the weeding processes occur [

11,

12]. In this sense, predicting weed emergence is of vital importance, as the seedling stage is the most vulnerable to control practices [

13,

14]. To achieve this, it is necessary to understand different aspects of weed biology underlying the emergence process, such as dormancy and germination, as a preliminary step to develop tools to guide decision-making [

4,

12,

15,

16]. Although there is a wealth of published information related to the study of these biological aspects in many weedy species of agricultural importance, this knowledge is scattered and not enough efforts have been made to integrate this information within a conceptual framework that would allow the development of transfer tools to assist farmers and technicians in decision-making for the management of weeds under both productive and environmental rationales.

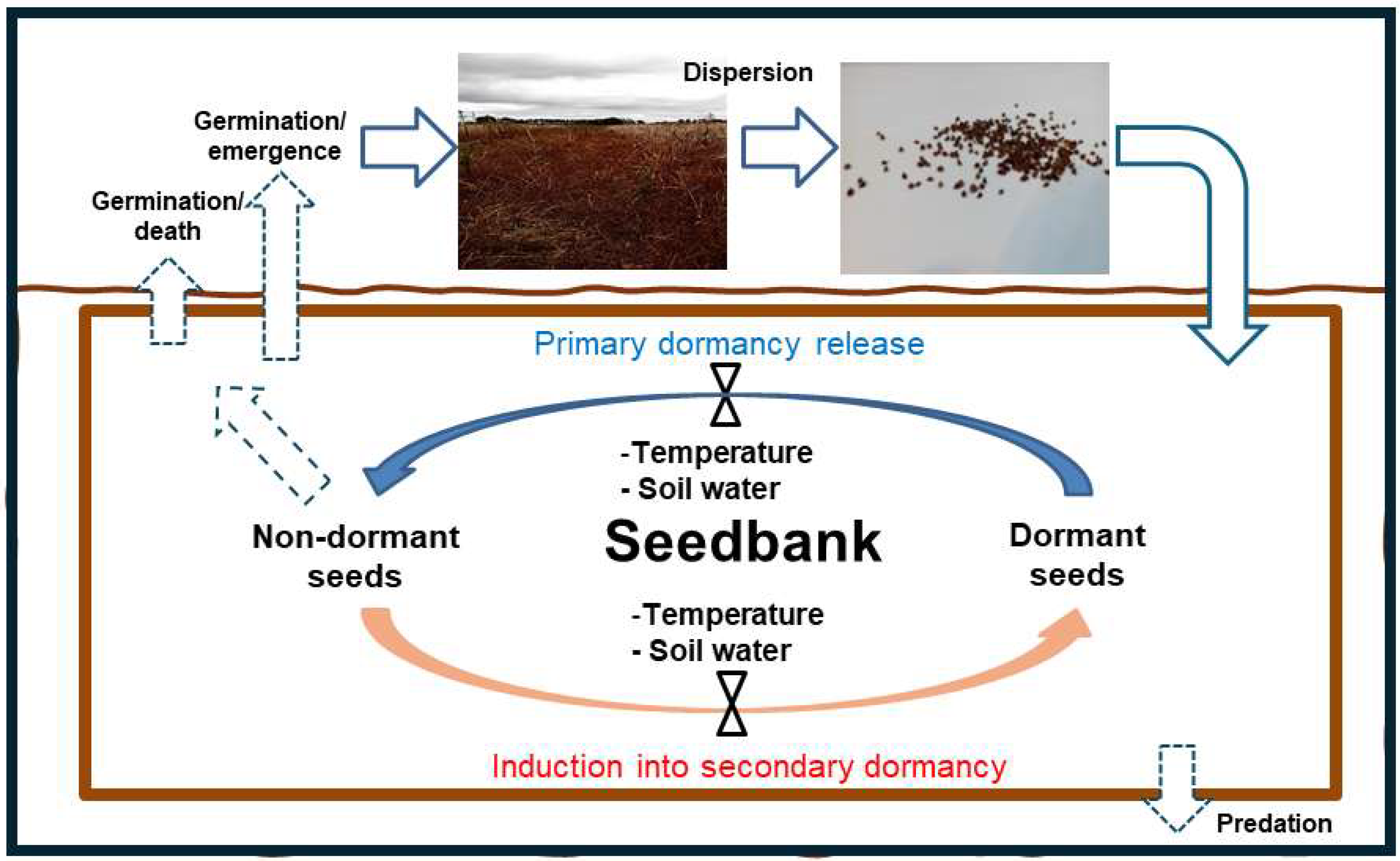

Weed management is a critical aspect of agricultural practices, significantly impacting crop yields and environmental sustainability. However, predicting the timing of weed emergence is challenging due to seed dormancy and the formation of persistent seedbanks. By integrating germination and dormancy models with site-specific weed management, growers can tailor control strategies to local conditions, improving the timing and precision of interventions. This approach enhances the effectiveness of weed control by addressing the unique dynamics of seedbanks in specific fields.

2. Seed Dormancy in Weed Species

Seed dormancy is a critical factor in the persistence of weed seedbanks and the timing of weed emergence [

17]. Dormancy mechanisms allow weed seeds to remain ungerminated in the soil for extended periods, emerging when conditions are favorable [

18]. The regulation of dormancy is influenced by various environmental cues, including temperature, light, alternating temperatures, and seed water content [

19,

20]. Understanding these cues and their interactions is essential for developing models that can predict weed emergence accurately. Seed dormancy is possibly the process that most affects seedbank emergence dynamics in agricultural fields [

4,

12], and it can be caused by one or more blockages which result in the failure to germinate even under adequate moisture, aeration, and temperature conditions [

3,

21,

22,

23,

24].

In an attempt to formulate a definition, Bewley and Black [

25] define dormancy as an internal characteristic of the seed that prevents germination under environmental conditions that would otherwise have been suitable for germination. On the other hand, Vleeshouwers et al. [

26], stated that dormancy is “a characteristic of the seed, the level of which will define what conditions must be met for the seed to germinate”. Later, Benech-Arnold et al. [

3] proposed a definition of dormancy that reinforces the intrinsic character of the phenomenon, defining it as “an internal seed condition that prevents seed germination under water, thermal and gaseous conditions that would otherwise have been suitable for germination to take place”. All these definitions denote that once the impedances have been removed, germination will occur under a wide range of environmental conditions. Depending on the timing of dormancy, dormancy can be classified into primary and secondary dormancy [

24,

27]. Primary dormancy refers to the dormancy of seeds dispersed from the mother plant, while secondary dormancy results from the reinduction of dormancy in seeds that had been previously released from primary dormancy [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

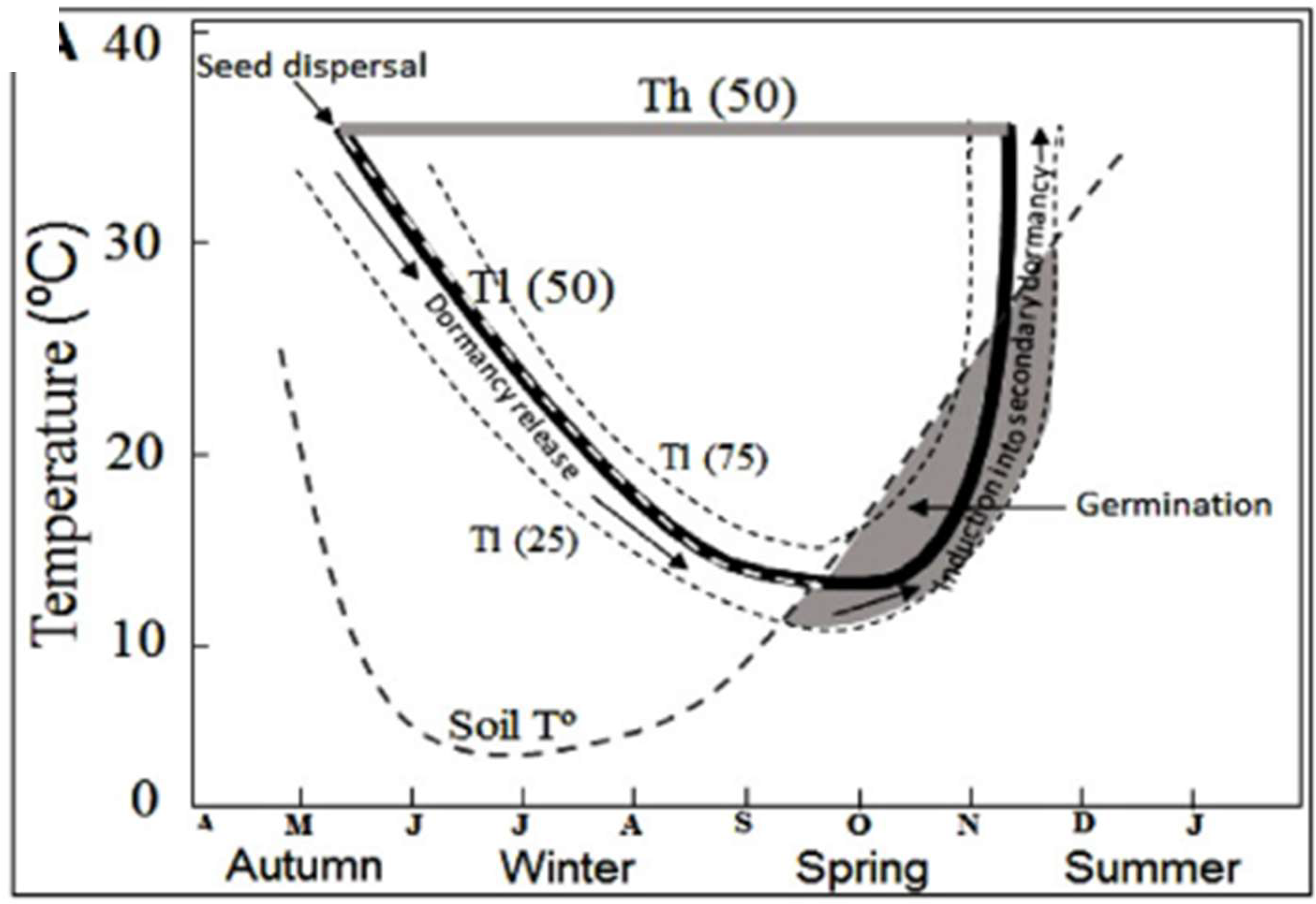

In many cases, release from primary dormancy is followed by subsequent reinductions into secondary dormancy, determining the existence of cyclical patterns in the dormancy level (

Figure 1). Many problematic weeds, particularly those capable of forming persistent seed banks, often exhibit cyclical changes in dormancy [

32]. For example, many spring annuals have a high dormancy level in autumn after dispersal, which decreases during the cold winter months and then increases again in the summer months. In contrast, winter annual species generally show an inverse temporal pattern in their dormancy level changes [

33]. This behavior highlights the adaptive value of dormancy, which plays an important role in the adaptation of plants to their environment, allowing them to identify the season of the year with favorable environmental conditions for plant establishment and constraints for establishment as the presence of a dense canopy or burial at depths from where a seedling cannot emerge [

24,

34].

3. Environmental Factors Regulating Changes in Seed Dormancy

The main environmental factors regulating weed emergence patterns are temperature and water availability [

35,

36]). These factors alter the dormancy level of seed banks determining seasonal patterns of weed emergence in the field [

19]. In winter annual species, high summer temperatures act as dormancy relievers, while low winter temperatures induce induction into secondary dormancy of seeds [

24]. This is the case for

Capsela bursa-pastoris [

37],

Avena fatua [

38],

Lolium rigidum [

39],

Bromus tectorum [

40] and

Lithospermun arvense [

41] and many others. In contrast, in summer annuals, the low temperatures experienced during winter act as dormancy relievers determining a minimum dormancy in early spring, while the high temperatures that prevails in late spring/early summer, produce an increase in the dormancy level determining through entrance into secondary dormancy; this is the case of

Chenopodium album L.,

Sysimbrium officinale L.,

Polygonum persicaria L. [

42],

Polygonum aviculare L. [

14,

43,

44],

Ambrosia artemiisifolia L. [

45],

Echinochloa crus-galli [

46] and many others.

The process by which summer annual species are released from dormancy during winter is known as ‘stratification’ or ‘chilling’, and is equivalent to expose the seeds to low temperatures under humid conditions. In the case of winter annuals, high summer temperatures acting on seeds with a low moisture content, alleviate dormancy; this process is called ‘after-ripening’. The moisture content of the seeds determines whether or not the above-mentioned processes (i.e., stratification or after-ripening) take place, as the moisture content of the seeds acts as a modulator of the effect of temperature on the dormancy level [

20,

47]. For example, Wang et al. [

48] observed that dormancy release at low temperatures in

Vitis vinifera was zero below 20% seed moisture and then increased to a maximum at 40% seed moisture. In turn, Bair et al. [

36] quantified the effect of soil water status on the dormancy release in seeds of

B. tectorum, observing that the inclusion of this factor in the model developed improved the prediction made. More recently, Malavert et al. [

20] quantitatively characterized the interaction between seed water content (SWC) and stratification temperature. The authors observed that in

P. aviculare seeds, the dormancy release rate was zero below 15% SWC and above that value, the release rate increased until it became maximal at 31% SWC. These results made it possible to describe the modulating effect of SWC on changes in dormancy level and to test a model that predicts adequately changes in

P. aviculare dormancy level as a function of the variation in SWC experienced by the seeds in the soil. Beyond this evidence, very few studies have attempted to quantify the effect of soil water content on seed moisture content and how this affects the cyclical changes in the dormancy level of seed populations.

Seed dormancy is a relative rather than an absolute phenomenon. The concept of relative dormancy levels was introduced by Vegis [

49] from observations obtained during the dormancy release process: the range of temperatures permissive for germination widens to a maximum as seeds are released from dormancy. In contrast, as dormancy is induced, the range of temperatures within which germination can proceed narrows until germination is no longer possible at any temperature. On this basis, Karssen [

24] proposed that seasonal patterns of emergence of annual species are the combined result of seasonal cycles in soil temperatures and physiological changes within seeds that alter the permissive temperature range for germination. Therefore, germination in the field is restricted to periods when soil temperature and the temperature range within which germination can proceed overlap (

Figure 2).

Thus, an increase or decrease in the dormancy level could be expressed as a widening or narrowing of the permissive temperature range for germination. These variations in the range of permissive temperatures for germination can be quantified from two threshold limit temperatures: lower limit temperature (T

l) and higher limit temperature (T

h) [

14,

43,

50]. These threshold temperatures (T

l and T

h) vary among seeds within the same population [

14,

43,

50]. For example, T

l(50) and T

h(50) represent the temperatures below and above which dormancy is expressed for 50% of the population. In summer annuals, changes in the dormancy level are due to increases or decreases in T

l, while in winter species are due to fluctuations in T

h. For summer annual species, such as

P. aviculare, germination of a fraction of the seedbank population occurs when the increase in soil temperature (in spring) exceeds the T

l for that fraction [

26,

44,

51]. This proportion of the seedbank able to emerge at a given time can be predicted if the distribution of T

l within the seed population and its associated changes with the level of seed dormancy, are known [

33,

43,

44], see

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of seasonal changes in the permissive germination thermal range and its relationship with soil temperature dynamics for

Polygonum aviculare seeds. Solid black lines indicate the mean lower (T

l(50)) and grey solid line the mean higher (T

h(50)) limits temperatures of the permissive thermal range allowing germination. Dashed black lines indicate T

l for the 25 and 75 seed population percentiles. Dashed gray line indicates the soil temperature (soil Tº). The gray zone represents the moment when germination occurs once the soil temperature enters in the permissive thermal range. Black arrows indicate the lowering and increase in T

l during dormancy release and induction, respectively (originally from Probert [

52], adapted from Malavert et al. [

44].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of seasonal changes in the permissive germination thermal range and its relationship with soil temperature dynamics for

Polygonum aviculare seeds. Solid black lines indicate the mean lower (T

l(50)) and grey solid line the mean higher (T

h(50)) limits temperatures of the permissive thermal range allowing germination. Dashed black lines indicate T

l for the 25 and 75 seed population percentiles. Dashed gray line indicates the soil temperature (soil Tº). The gray zone represents the moment when germination occurs once the soil temperature enters in the permissive thermal range. Black arrows indicate the lowering and increase in T

l during dormancy release and induction, respectively (originally from Probert [

52], adapted from Malavert et al. [

44].

4. Seed Dormancy Terminating Factors

As previously mentioned, the dormancy level is constantly changing in the seedbank. Often, when the dormancy level of a seed population is sufficiently low, certain species require exposure to specific environmental signals that act as dormancy terminators. These signals remove the final barriers and initiate the germination process [

3,

53,

54]. Among the most studied dormancy-terminating factors are light and alternating temperatures, as these typically have the greatest effect under field conditions [

55,

56,

57,

58]. The requirement for light is associated with the possibility of detecting gaps in the canopy or the depth to which the seeds are buried and is also regarded as an adaptation to recurrent tillage operations in agricultural systems [

3,

53]. Conversely, alternating temperatures constitute an important environmental signal for dormancy termination, since below the first millimeters of depth in the soil, the influence of the light environment is null and, therefore, alternating temperatures are the only way of detecting burial depth [

59,

60,

61].

The changes in dormancy level not only comprise changes in the range of temperatures permissive for germination, but also changes in the sensitivity of the seed population to the effects of these dormancy-terminating factors [

3]. For example, in the case of seeds that require light stimulus to terminate dormancy, Batlla and Benech-Arnold [

56] and Malavert et al. [

57] observed that the dynamics of changes in the dormancy level in

P. aviculare seeds during stratification were associated with changes in the light sensitivity of the seed population: sensitivity increased as dormancy decreased and

viceversa. Similarly, for seeds requiring temperature fluctuations to terminate dormancy, Benech-Arnold et al. [

62] showed that the size of the fraction in

Sorghum halepense L. seed population responding to the stimulatory effect of temperature fluctuations increased as a consequence of a burial period under winter temperatures. The authors observed that this increase was also accompanied by changes in the number and amplitude of fluctuating temperature cycles required to complete exit from dormancy.

S. halepense seeds that had spent one winter buried in the soil required exposure to fewer cycles of alternating temperatures to exit from dormancy and acquired the ability to respond to cycles of lower thermal amplitude.

5. Population-Based Threshold Models

The use of predictive models in weed control strategies is becoming increasingly relevant due to current pressures to reduce the excessive use of chemical controls in agricultural production [

46,

63]. These models rely on biological timing, where germination occurs at different rates depending on environmental conditions [

64,

65]). These rates are determined by the progress towards germination as a function of the difference between environmental conditions and a minimum threshold value, below which germination does not occur, or a maximum threshold value, above which there is also no response [1966]. For example, the timing and likelihood of seed germination are determined by the seed’s threshold sensitivity to environmental signals - the greater the signal above the threshold, the faster the response.

Population-based threshold models (PBTMs) describe how individuals within a population respond to environmental factors based on varying thresholds. In these models, each individual has a specific threshold for responding to cues like temperature or moisture, leading to a diversity of responses across the population [

66]. As environmental conditions change, more individuals surpass their thresholds, resulting in cumulative population-level responses, often represented as quantal outcomes (i.e., germinated or not) [

67,

68]. PBTMs are useful for predicting collective behaviors in populations, such as seed germination patterns or emergence timing, by accounting for individual variation within a population. This kind of approach can be a robust tool for predicting how weed populations respond to environmental shifts, making them increasingly relevant in adapting weed control strategies to the impacts of global climate change. Some of the most used PBTMs consider germination in the predictions; however, very few models consider changes in dormancy level in their predictions. The most common germination models are:

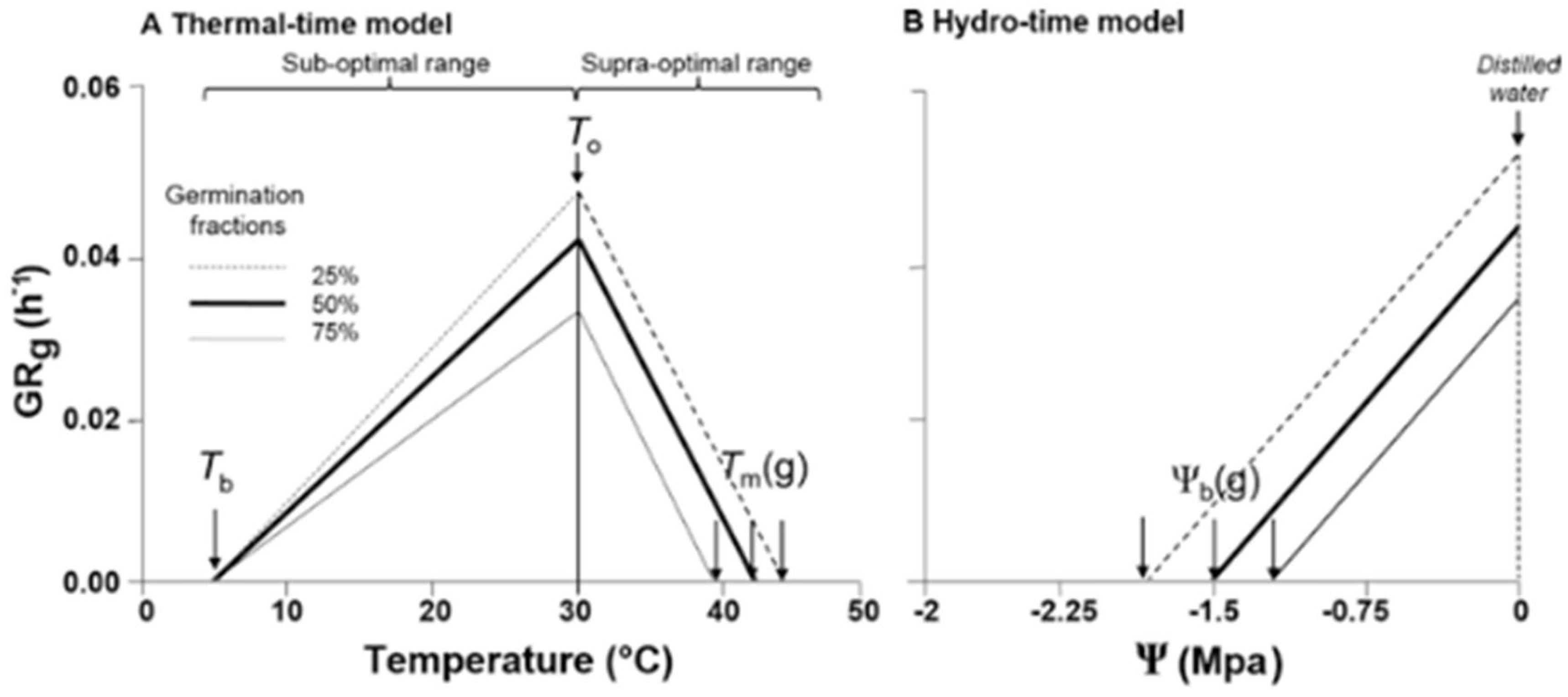

6. Models to Predict Germination:

Thermal time model (TT): This model predicts germination in non-dormant seeds as a function of soil temperature. This type of model consists of certain variables that need to be characterized to estimate the percentage of seed population germination at a given time: base temperature (T

b), optimum temperature (T

o), maximum temperature (T

m), and thermal time (TT) required for a specific fraction of the population to germinate (i.e., 25% (TT

25), 50% (TT

50), and 75% (TT

75) of the population). The model accumulates degree days (ºCd) per day from a T

b in a sub-optimal (i.e., T

b > T

o) and supra-optimal (T

o > T

m) temperature range (

Figure 3a). It is useful for studying germination at different temperatures (a wide range of temperatures). This approach has been applied to species such as

Setaria (i.e.,

S. viridis,

S. verticillata, and

S. glauca; [

69], and the work demonstrates that

S. glauca has lower cardinal temperatures compared to other

Setaria species. Using this model, the germination requirements and time of emergence can be predicted to optimize weed management for these species. In

Amaranthus retroflexus, Chenopodium álbum, Digitaria sanguinalis and

Abutilon theophrasti a similar approach was used to identify the T

b and TT to predict the cumulative emergence in the field [

70]. This type of approach has been widely used to determine T

b and TT of many weeds which is critical for optimizing weed control timing, since knowing when a certain proportion of weed seeds will likely emerge enables precise application of herbicides or cultivation practices.

Hydrotime (HT) model: This model focuses exclusively on the effect of water potential (Ψ) on seed germination. It assumes that each seed within a population has a specific base water potential threshold for germination, which enables the modeling of population-level responses under varying levels of water availability (

Figure 3b; [

71]. The model has been successfully applied to quantify the effects of water potential on germination and to describe the variability in germination timing among individual seeds. For example, Huarte [

72] applied the hydrotime model to several non-cultivated species, estimating key parameters such as the hydrotime constant (θ

H), the median base water potential (Ψ

b(50)), and its standard deviation (σ

Ψb). This approach revealed that individual seeds differ in their base water potential thresholds, resulting in heterogeneous germination patterns across environmental conditions. Similarly, Tao et al. [

73] applied the model to

Astragalus sinicus, a forage legume, and demonstrated that hydrotime parameters not only vary between seed lots but also correlate with seed vigor and seedling emergence performance. In another example, Boddy et al. [

68] used the hydrotime approach with

Echinochloa phyllopogon, showing how environmental data combined with HT modeling can accurately describe temperature and moisture effects on germination and emergence, supporting improved weed control strategies. Collectively, these studies highlight the versatility and predictive value of the hydrotime model for understanding and managing seed germination under water-limited and fluctuating environmental conditions.

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic representation of the relationship between germination rates (GRg= 1/tg) and temperature at the suboptimal and the supra-optimal thermal range for 25, 50 and 75% of a seed population. (B) Relationship between GRg and water potential for 25, 50 and 75% of a seed population. Adapted from Batla et al. [

74].

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic representation of the relationship between germination rates (GRg= 1/tg) and temperature at the suboptimal and the supra-optimal thermal range for 25, 50 and 75% of a seed population. (B) Relationship between GRg and water potential for 25, 50 and 75% of a seed population. Adapted from Batla et al. [

74].

Hydrothermal Time (HTT) model: This model extends the basic thermal time model by including both temperature and water potential [

67]. It calculates the accumulation of hydrothermal time required for germination fraction (i.e., HTT

25, HTT

50, HTT

75) to occur and is widely used to simulate germination under water stress conditions. This approach was used to study the germination and emergence of

Amaranthus retroflexus in response to water and temperature stress [

75]. The hydrothermal time model has been used to assess the combined effects of temperature and water potential on the germination of

A. retroflexus, a problematic weed in agriculture. The authors modeled the hydrothermal time required for germination under various environmental conditions, demonstrating that water stress alters the optimal temperature for germination. The HTT model provided a robust framework for predicting weed emergence in varying field environmental conditions, contributing to improved timing of weed control measures.

7. Models to Predict Seed Dormancy and Germination

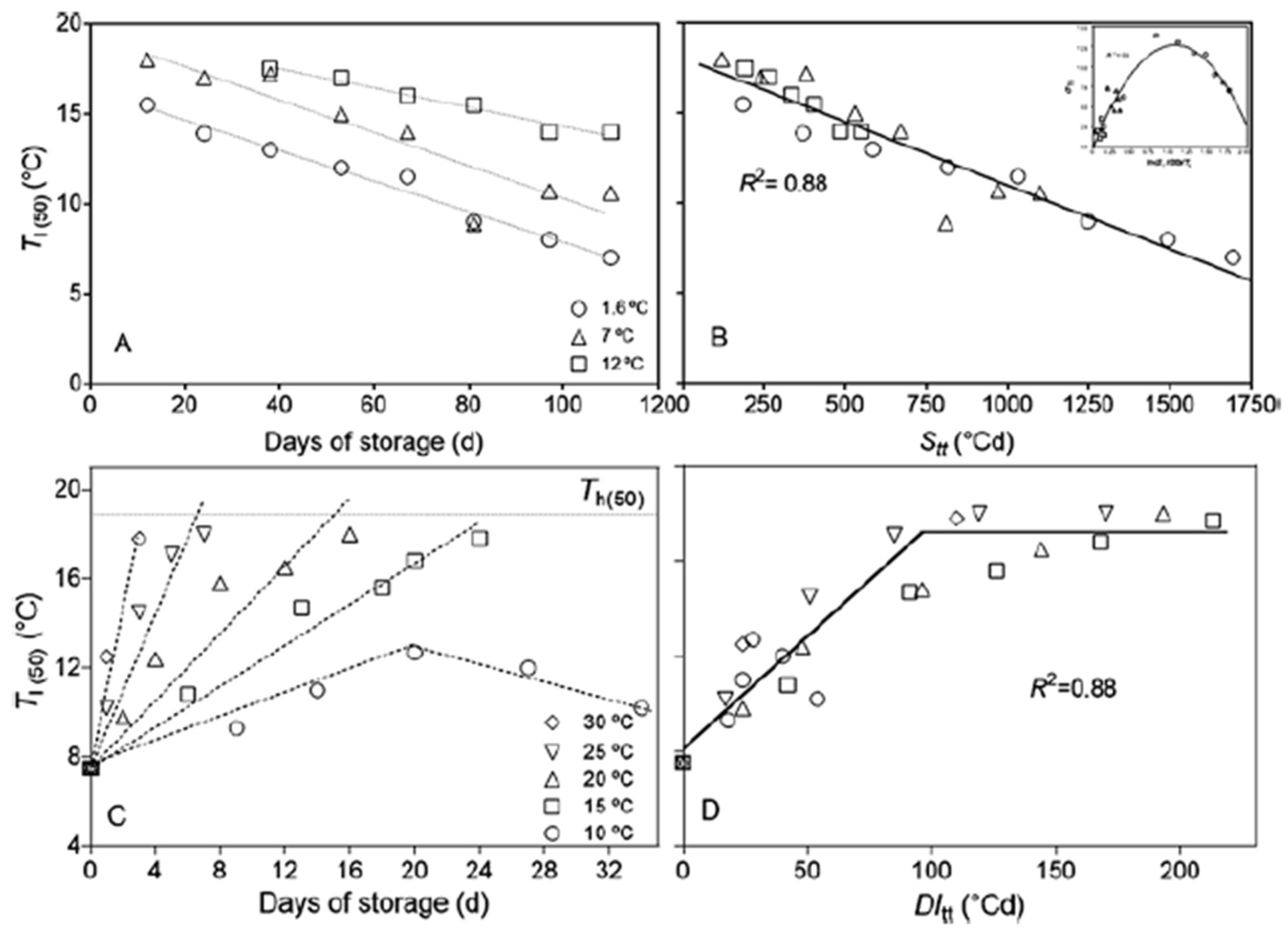

7.1. Stratification Thermal-Time and Dormancy Induction Thermal-Time

The germination models (i.e., TT, HT and HTT) explained above work well for non-dormant seeds. However, when a seedbank contains seeds with dormancy, it is essential to establish functional relationships between the environmental factors that regulate variations in the dormancy level and the rate-change at which seeds decrease or increase dormancy. Since temperature and water availability are the main factors that regulate these cyclical changes in dormancy level, we must define parameters that accurately characterize these changes. As mentioned above, the changes in seed dormancy can be characterized through the range of temperatures within which seeds can germinate. This range can be characterized by changes in the limit temperatures that allow germination: T

l and T

h and their deviations (

Figure 2). To establish functional relationships between time, temperature and dormancy level, Batlla and Benech-Arnold [

43] developed a Stratification thermal-time model (S

tt;

Figure 4a, b) and Malavert et al. [

44], Dormancy induction thermal-time (DI

tt;

Figure 4c, d) for

Polygonum aviculare. These models quantify seed dormancy release and induction for seeds stratified at different temperatures through changes in the range of temperatures permissive for germination as a consequence of changes in the mean lower limit temperature of the range (T

l(50); see

Figure 2). These thermal-time approaches are similar to that usual in other weed species to relate germination or emergence processes as a function of time and temperature. However, in contrast to common thermal-time models in which ºCd are accumulated over a T

b, S

tt and DI

tt accumulate ºCd below or above a ceiling threshold temperature below which dormancy release or above dormancy induction occurs [

74].

These models work simultaneously in the accumulation of ºCd after dispersal (

P. aviculare disperses with a high level of dormancy in early autumn). Due to lower autumn and winter temperatures, the S

tt model accumulates more ºCd units (beginning to operate at soil temperatures below 17ºC), allowing the dormancy release process (

Figure 4b). Then, as temperatures rise in early spring, the DI

tt model begins to accumulate more ºCd than S

tt (operating at soil temperatures above 7.9ºC) (

Figure 4d). Once DI

tt units surpass the accumulation of S

tt units, induction into secondary dormancy predominates [

44]. The accumulated ºCd can be used to predict how the thermal range permissive for seed germination changes (i.e., widen and narrow) as a consequence of variations in T

l during dormancy release and induction, in relation to soil temperature. Quantifying temperature effects through a thermal-time approach enables predictions of the dormancy level in a seed population exposed to the variable soil field thermal environment. These models are particularly functional, as they predict when the ‘emergence window’ will open and close and estimate the proportion of seeds likely to emerge within that window.

Recently, the effect of seed moisture content on the rate of dormancy release and induction in

P. aviculare seeds was incorporated (

Figure 5; [

20]). This approach allowed the identification of two seed water content (SWC) thresholds: a minimum value of SWC required to activate metabolic processes in the seeds (the rate at which the process takes place is minimal) and a value which maximizes the velocity of the processes that leads either to dormancy release or to dormancy induction (i.e., 31%) (

Figure 5b). The inclusion of the effect of SWC on dormancy changes improved the prediction of seedling emergence in relation to predictions made using only temperature as a driver of dormancy changes [

20].

7.2. After-Ripening Thermal-Time Models

After-ripening (AR) thermal-time models are crucial for understanding the temperature-driven dynamics of seed dormancy release under dry conditions. As explained above, this mechanism is common in winter annuals. More recently, Batlla et al. [

76] developed a model for

Arabidopsis thaliana that associates temperature with dormancy cycling, predicting how seasonal soil temperature fluctuations influence after-ripening and enable germination under favorable conditions. Similarly, Christensen et al. [

40] modeled

Bromus tectorum by simulating dormancy loss during AR process through variations in the base water potential (ψ

b(50)). In the case of

Lithospermum arvense, Chantre et al. [

41] developed an AR thermal-time model that parameterizes germination taking into account primary dormancy release. Their findings revealed that the rate of dormancy release increases with temperature, making the model a valuable tool for predicting weed emergence. This research demonstrated the potential of AR thermal-time models to support weed management strategies by optimizing predictions of dormancy loss and germination timing based on environmental conditions in autumn-winter species.

The PBTMs offer a promising approach to predicting weed emergence by incorporating the dynamics of seed dormancy and environmental cues. These models use the functional relationships between environmental factors and weed emergence patterns to forecast the timing and extent of seedling emergence. By integrating site-specific environmental data, such as soil temperature and moisture levels, these models can provide precise predictions tailored to specific agricultural landscapes.

8. Application of PBTMs in Site-Specific Weed Management

The PBTMs could be applied in site-specific weed control to predict weed emergence in fields with landscape heterogeneity. This variability most likely leads to weed patches that justify site-specific weed control as a more efficient methodology both from an economic and environmental standpoint. Indeed, factors such as soil temperature and soil water content, previously pointed out as modulators of seed dormancy and germination, can be expected to vary with the position in topography, thus determining variations in weed emergence intensity and temporality. These models could be useful for forecasting the timing and proportion of weeds likely to germinate/emerge differentially based on the part of the topography where they are located, provided we are able to trace the dynamics of soil water content and soil temperature in the various topographic positions. These models consider the changes in seed dormancy as a function of soil temperature and soil water content to accurately forecast the time window for seedling emergence and to provide a notion of the size of the emergence that is taking place within that window. The application of PBTMs in developing georeferenced weed emergence maps enhances precision agriculture by optimizing herbicide use, targeting high-risk areas, and minimizing application in low-risk zones.

For a case study, we selected a location in the agricultural region of Buenos Aires province, in General La Madrid, in the southern part of the province (Lat -37.48; Long -61.41). For the simulation (see Simulation model approach section in Data supplementary; Table S1), we considered two years with contrasting rainfall patterns (i.e., cold-wet (2017; using daily soil temperature and soil moisture data from the NASA POWER database) and a dry winter (2023), in which water restriction values were hypothetical, designed to represent realistic but conservative conditions for stratification. We assume that P. aviculare seeds are homogeneously distributed in the field. Based on this assumption, the model was run from May 1st, when seed dispersion had ended (i.e., around March-April).

To explore how topographic variation influences

P. aviculare emergence size, simulations were performed across a range of elevation levels (320, 315, 302, 290, 279, and 260 m), using stratification and dormancy induction thermal-time models (S

tt and DI

tt) and incorporating soil water content (SWC) dynamics. A 20% emergence threshold was used to define the decision point for chemical control, as it represents a balance between effective weed suppression (translated into the economic benefit of yield increase) and the cost of herbicide plus application. This threshold aligns with the concept of economic thresholds in weed science, which define the weed density or emergence level at which the cost of control equals the potential crop yield loss prevented [

77,

78,

79]. In the absence of

P. aviculare specific thresholds, this 20% level is supported by empirical studies showing that action thresholds between 15–25% weed emergence or coverage can optimize yield and input efficiency in cereal systems [

80,

81]. Two contrasting scenarios were simulated: 1) one assuming unrestricted water availability, and 2) another assuming limited soil moisture (see Table S2 and Table S3, Data Supplementary). In the first scenario, the model predicts emergence above the 20% threshold (

Figure 6) across all topographic positions from June 17th onwards (Figure S1; Data supplementary).

For the second scenario in the same location, a water restriction during stratification (i.e., cold-dry winter year, 2023) was simulated (see Table S2, Supplementary Data). Under this scenario, SWC was assumed to fluctuate between <15 and 22% throughout the stratification period. These values fall within the range previously identified as the threshold below which dormancy release is either absent or occurs at a minimal rate in

P. aviculare seeds [

20]. This water limitation affected only dormancy dynamics, not germination directly, since the model assumes that germination occurs only after dormancy is lifted and favorable temperature and moisture conditions are met with. In this scenario, the simulation results showed that: i) under cold-dry winter conditions, the model predicts a delay in the onset of emergence, shifting the window to late July (28/07) and early August (08/08) in the lower topographic positions (279 m and 260 m), as opposed to earlier emergence observed in the cold-wet (2017) simulation (i.e., emergence start at 15/06 for 279 and 260 m). Despite this delay, emergence still exceeded the 20% threshold in these lower areas (

Figure 7, red pixels). ii) The model predicts that the maximum emergence proportion reaches 24% at 279 m and 42% at 260 m, respectively (Figure S2; Supplementary Data). iii) The emergence window closes approximately 22 days later (August 22nd) and is narrower than in the previous simulation, which extended from June 15th to September 26th, 2017 (103 days in total). This simulation indicates that although at low topographic positions emergence exceeds the 20% indicated as a threshold, under low soil water content, the emergence window becomes more limited in duration, and the overall proportion of seeds able to germinate is reduced as compared with a cold-wet year. In contrast, at higher topographic positions (i.e., 290 to 320 m), the emergence remained below the 20% threshold, precluding chemical control.

This spatial heterogeneity in emergence allows for site-specific herbicide applications, as spraying can be restricted to zones that exceed the control threshold: only the lower topographic positions (260–279 m) would require herbicide treatment in dry years, while higher areas would be spared, potentially reducing herbicide use by up to 60–70%, depending on field topography. This model demonstrates that, even when thermal stratification requirements are met with, if water content is limiting for dormancy release, P. aviculare emergence above the 20% threshold would be confined to low topographic positions, where water accumulates and allows dormancy release through Stt accumulation. Although the model focused on soil moisture as the main driver of stratification process, topographic variation could also influence soil temperature and, consequently, emergence patterns. This spatial variation supports the use of georeferenced weed emergence maps and variable-rate sprayers to selectively target areas with higher emergence, reducing chemical use in low-risk zones. Such strategies improve weed control efficiency, reduce costs, and minimize environmental impact.

In addition to site-specific herbicide applications, weed control in P. aviculare can be further optimized through adjustments site-specific in wheat density and sowing date. In wet winters with high predicted weed emergence, increasing wheat sowing density can enhance crop competition, reducing light availability and space for weeds.

9. Conclusions

The problem of troublesome weeds in agricultural fields has increased in recent years [

82]. In this regard, the use of Population-Based Threshold Models (PBTMs) in site-specific weed management could represent a significant advancement in agricultural practices, offering a valuable approach for controlling weed emergence with precision and minimum economic and environmental cost [

66,

83,

84,

85]. By integrating dynamic, multidimensional field information, such as soil temperature, soil water content, and topographic variations, and incorporating seedbank dormancy dynamics into these models, PBTMs provide accurate predictions of weed “emergence windows” and proportions [

33]. This approach could reduce the risks associated with traditional weed management practices by shifting toward more economically and environmentally sustainable solutions [

86], enabling optimized herbicide applications, minimizing input costs, and reducing environmental impact.

Future research should focus on integrating PBTMs with technological advances in agriculture. Precision farming tools, like autonomous machines (self-driving tractors and sprayers), can follow herbicide application maps from PBTMs to target high weed-pressure areas, reducing unnecessary herbicide use. Drones can provide real-time aerial imagery to monitor weeds and assess herbicide effectiveness. Sensors in agricultural machinery can gather data on soil moisture, temperature, and weed emergence, enhancing PBTMs accuracy and enabling precise herbicide application adjustments. Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) can analyze large datasets, improving weed emergence predictions and refining herbicide use. Additionally, Decision Support Systems (DSS) could provide guidance on herbicide applications, incorporating PBTMs outputs and real-time data on weed density, crop health, and weather. Integrating PBTMs with farm management software would allow farmers to manage pest and weed control in one platform (i.e., cellular applications apps), simplifying decision-making and improving overall farm efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CM, DB and RBA; writing - original draft preparation, CM, DB, RBA. Formal analysis, CM, DB and RBA. Review and editing, CM, DB and RBA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data that supports this study is available in the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica PICT-2021-00563.

Interest conflict

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Labrada, R.; Parker, C. El control de malezas en el contexto del manejo integrado de plagas. Estudio FAO: Produccion y Proteccion Vegetal (FAO) 1996, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Karssen, C.M. Patterns of change in dormancy during burial of seeds in soil. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 1980, 29, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benech-Arnold, R.L.; Sánchez, R.A.; Forcella, F.; Kruk, B.C.; Ghersa, C.M. Environmental control of dormancy in weed seed banks in soil. Field Crops Res. 2000, 67, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcella, F.; Benech-Arnold, R.L.; Sánchez, R.A.; Ghersa, C.M. Modeling seedling emergence. Field Crops Res. 2000, 67, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, K.D.; Fischer, A.J.; Foin, T.C.; Hill, J.E. Crop traits related to weed suppression in water-seeded rice (Oryza sativa L.). Weed Sci. 2003, 51, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, R.F.; Kogan, M. Ecology of interactions between weeds and arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2005, 50, 479–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinelli, G.; Vicari, A.; Marotti, I.; Catizone, P. Biological activity of flavonoids from Scrophularia canina L. (Scrophulariaceae). Weed Res. 1996, 36, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, J.C.; Guglielmini, A.C.; Satorre, E.H. Ryegrass interference and herbicide efficacy in wheat under different nitrogen levels. Weed Sci. 2005, 53, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scursoni, J.A.; Papa, J.C.; Tuesday, J.D.; Satorre, E.H. Glyphosate efficacy in relation to weed stage and application timing. Weed Technol. 2007, 21, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmini, A.C.; Verdelli, D.; Satorre, E.H. Modeling dynamics of glyphosate-resistant soybean emergence. Agric. Téc. 2003, 63, 347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. Predicting changes in dormancy level in natural seed soil banks. Plant Mol Biol. 2010, 73, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, A.C. Predicting weed emergence: a review of approaches and future challenges. Weed Res. 2003, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, M. Dormancy and germination of Rumex seeds. New Phytol. 1978, 80, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, B.C.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. Benech-Arnold. Functional and quantitative analysis of seed thermal responses in prostrate knotweed (Polygonum aviculare) and common purslane (Portulaca oleracea). Weed Sci. 1998, 46, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, T.W. The physiology of seed hydration and dehydration, and the relation between water stress and the control of germination: a review. Plant Cell Environ. 1978, 1, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, P.C. Weed biology: importance to weed management. Weed Sci. 1997, 45, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucera, B.; Cohn, M.A.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Plant hormone interactions during seed dormancy release and germination. Seed Sci. Res. 2005, 15, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Footitt, S.; Huang, Z.; Clay, H.A.; Mead, A.; Finch-Savage, W.E. Temperature, light and nitrate sensing coordinate Arabidopsis seed dormancy cycling and germination. Plant J. 2011, 74, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavert, C.; Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. The role of seed water content for the perception of temperature signals that drive dormancy changes in Polygonum aviculare buried seeds. Funct. Plant Biol. 2020, 48, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amen, R.D. A model of seed dormancy. Bot. Rev. 1968, 34, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egley, G.H. Stimulation of weed seed germination in soil. Rev. Weed Sci. 1986, 2, 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, A. Seed dormancy. Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities, 2013; 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karssen, C.M. Seasonal patterns of dormancy in weed seeds. In The Physiology and Biochemistry of Dormancy and Germination of Seeds; Khan, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, J.D.; Black, M. Seeds—Physiology of Development and Germination, 2nd ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Vleeshouwers, L.M.; Bouwmeester, H.J; Karssen, C.M. Redefining seed dormancy: an attempt to integrate physiology and ecology. J. Ecol. 1995, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilhorst, H.W.M. A critical update on seed dormancy. I. Primary dormancy. Seed Sci. Res. 1995, 5, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilhorst, H.W.M. The regulation of secondary dormancy. The membrane hypothesis revisite. Seed Sci. Res. 1998, 8, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.E. Exploiting weed seed dormancy and germination requirements through agronomic practices. Weed Sci. 1995, 43, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S. Role of weed emergence time for the relative seed production in maize. Ital. J. Agron. 2007, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brändel, M.; Jensen, K. Effect of temperature on dormancy and germination of Eupatorium cannabinum L. achenes. Seed Sci. Res. 2005, 15, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Germination ecophysiology of herbaceous plant species in a temperate region. Am. J. Bot. 1988, 75, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. A framework for the interpretation of temperature effects on dormancy and germination in seed populations showing dormancy. Seed Sci. Res. 2015, 1–12, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soppe, W.J; Bentsink, L. Dormancy in plants. In Encyclopedia of life science; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, J.D. Seed germination and dormancy. Plant Cell. 1997, 9, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, N.B.; Susan, E.M.; Phil, S.A. A hydrothermal after-ripening time model for seed dormancy loss in Bromus tectorum L. Seed Sci. Res. 2006, 16, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. Germination responses of buried seeds of Capsella bursa-pastoris exposed to seasonal temperature changes. Weed Res. 1989, 29, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C; Baskin, J.M. Seeds—ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination; Academic Press: San Diego, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, K.J.; Bignell, G.P.; Ellery, A.J. Field assessment of thermal after- ripening time for dormancy release prediction in Lolium rigidum seeds. Weed Res. 2003, 43, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.; Meyer, S.; Allen, P.S. A hydrothermal time model of seed after-ripening in Bromus tectorum L. Seed Sci. Res. 1996, 6, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantre, G.R.; Sabbatini, M.R.; Orioli, G.A. An after-ripening thermal-time model for Lithospermum arvense seeds based on changes in population hydrotime parameters. Weed Res. 2010, 50, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, H.J. The effect of environmental conditions on the seasonal dormancy pa tern and germination of weed seeds. PhD thesis, Agricultural University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1990; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. A quantitative analysis of dormancy loss dynamics in Polygonum aviculare L. seeds: development of a thermal time model based on changes in seed population thermal parameters. Seed Sci. Res. 2003, 13, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavert, C.; Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. Temperature- dependent regulation of induction into secondary dormancy of Polygonum aviculare L. seeds: a quantitative analysis. Ecol. Model. 2017, 352, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. Ecophysiology of secondary dormancy in seeds of Ambrosia Artemisiifolia. Ecol. 1980, 61, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavert, C.; Batlla, D. Thermal regulation of dormancy in Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) P. Beauv. seeds: Development of a model to predict the temporal ‘window’ of emergence in the field. Weed Res. 2024, 64, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. The role of fluctuations in soil water content on the regulation of dormancy changes in buried seeds of Polygonum aviculare L. Seed Sci. Res. 2006, 16, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Q.; Song, S.Q.; Li, S.H.; Gan, Y.Y.; Wu, J.H.; Cheng, H.Y. Quantitative description of the effect of stratification on dormancy release of grape seeds in response to various temperatures and water contents. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 3397–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegis, A. Dormancy in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1964, 15, 185–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washitani, I. A convenient screening test system and a model for thermal germination responses of wild plant seeds: behaviour of model and real seeds in the system. Plant, Cell Environ. 1987, 10, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vleeshouwers, L.M.; Bouwmeester, H.J. A simulation model for seasonal changes in dormancy and germination of weed seeds. Seed Sci. Res. 2001, 11, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probert, R.J. The role of temperature in germination ecophysiology. In The ecology of regeneration in plant communities; Fenner, M., Ed.; C.A.B. International: Wallingford, 1992; pp. 285–325. [Google Scholar]

- Scopel, A.L.; Ballaré, C.L.; Sánchez, R.A. Induction of extreme light sensitivity in buried weed seeds and its role in the perception of soil cultivation. Plant Cell Environ. 1991, 14, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghersa, C.M.; Benech-Arnold, R.L.; Martinez-Ghersa, M.A. The role of fluctuating temperatures in germination and establishment of Sorghum halepense. Regulation of germination at increasing depths. Funct. Ecol. 1992, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlla, D.; Verges, V.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. A quantitative analysis of seed responses to cycle- doses of fluctuating temperatures in relation to dormancy level. Development of a thermal-time model for Polygonum aviculare L. seeds. Seed Sci. Res. 2003, 13, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. Seed dormancy loss assessed by changes in Polygonum aviculare L. population hydrotime parameters. Development of a predictive model. Seed Sci. Res. 2004, 14, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavert, C.; Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. Light sensitivity changes during dormancy induction in Polygonum aviculare L. seeds: development of a predictive model of annual changes in seed-bank light sensitivity in relation to soil temperature. Weed Res. 2021, 61, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavert, C.; Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. Modelling changing sensitivity to alternating temperatures during induction of secondary dormancy in buried Polygonum aviculare L. seeds to aid in managing seedbank behaviour. Weed Res. 2022, 62, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, D.; Smith, H. Penetration of light into soil and its role in the control of seed germination. Plant Cell Environ. 1985, 8, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, T.L. Seed responses to light. In Seeds: the ecology of regeneration in plant communities; Fenner, M., Ed.; CAB Publishing: Wallingford, 2000; pp. 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, M.; Morris, C. The penetration of light through soil. Plant Cell Environ. 1987, 10, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benech-Arnold, R.L.; Ghersa, C.M.; Sanchez, R.A.; Insausti, P. Temperature effects on dormancy release and germination rate in Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers. seeds: a quantitative analysis. Weed Res. 1990, 30, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, A.C.; Mead, A. Modelling weed emergence as a function of meteorological records. Weed Sci. 2000, 48, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, K.J. Population-based models describing seed dormancy behavior: implications for modeling and understanding germination behavior in seed populations. Seed Sci. Res. 1996, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.E. The use of population-based threshold models to describe and predict the effects of seedbed environment on germination and seedling emergence of crops. In Handbook of seed physiology: applications to agriculture; Benech-Arnold, R.L., Sánchez, R.A., Eds.; Haworth Press: New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, K.J.; Bello, P. Seed germination modeling: progress and prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 854492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, K.J. Applications of hydrothermal time to quantifying and modeling seed germination and dormancy. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, L.G.; Bradford, K.J.; Fischer, A.J. Population-based threshold models describing the effects of temperature and water potential on weed seed germination. Weed Sci. 2012, 60, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaee, M.; Darbandi, E.I.; Aval, M.B.; Chauhan, B.S. Germination response of three Setaria species (S. viridis, S. verticillata, and S. glauca) to water potential and temperature using non-linear regression and hydrothermal time models. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2020, 42, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masin, R.; Loddo, D.; Benvenuti, S.; Zuin, M.C.; Macchia, M.; Zanin, G. Temperature and water potential as parameters for modeling weed emergence in central-northern Italy. Weed Sci. 2010, 58, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, K.J. The hydrotime concept in seed germination and dormancy. In Basic and Applied Aspects of Seed Biology: Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Seeds, Reading, 1995; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Huarte, R. Hydrotime analysis of the effect of fluctuating temperatures on seed germination in several non-cultivated species. Seed Sci. Tech. 2006, 34, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Chen, D.; Bai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Chen, X.; Sun, X.; Niu, T.; Nie, Y.; Zhong, S. Hydrotime Model Parameters Estimate Seed Vigor and Predict Seedling Emergence Performance of Astragalus sinicus under Various Environmental Conditions. Plants 2023, 12, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batlla, D.; Malavert, C.; Farnocchia, R.B.F.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. Modelling weed seedbank dormancy and germination. In Decision Support Systems for Weed Management; Chantre, G.-R., González-Andújar, J.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesgaran, M.B.; Onofri, A.; Mashhadi, H.R.; Cousens, R.D. Water availability shifts the optimal temperatures for seed germination: a modelling approach. Ecol Model. 2017, 351, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlla, D.; Malavert, C.; Farnocchia, R.B.F.; Footitt, S.; Benech-Arnold, R.L.; Finch-Savage, W.E. A quantitative analysis of temperature-dependent seasonal dormancy cycling in buried Arabidopsis thaliana seeds can predict seedling emergence in a global warming scenario. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2454–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coble, H.D.; Mortensen, D.A. The threshold concept and its application to weed science. Weed Tech. 1992, 6, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousens, R. Theory and reality of weed control thresholds. Plant Prot. Q. 1987, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Swanton, C.J.; Nkoa, R.; Blackshaw, R.E. Experimental methods for crop–weed competition studies. Weed Sci. 2015, 63, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, R.; Christensen, S. Real-time weed detection, decision making and patch spraying in maize, sugarbeet, winter wheat and winter barley. Weed Res. 2003, 43, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J.; Nørremark, M.; Bibby, B.M. Assessment of leaf cover and crop soil cover in weed harrowing research using digital images. Weed Res. 2007, 47, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratti, I.; Sabeti, P.; Chaghamirzaee, G.; Heidari, H. Weed problems, challenges, and opportunities in Iran. Crop Prot. 2020, 134, 104371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriade, C.A. A bioeconomic analysis of site-specific management and delayed planting strategies for weed control; University of Minnesota, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- López-Granados, F. Weed detection for site-specific weed management: mapping and real-time approaches. Weed Res. 2011, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, R.; Vangeyte, J.; Christensen, S.; Søgaard, H.T. Future visioning of precision weed management. Weed Res. 2022, 62, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.A.; Cardina, J.; Mortensen, D.A. Site-specific weed management: Current and future directions. In The State of Site-Specific Management for Agriculture; Pierce, F.J., Sadler, E.J., Eds.; ASA-CSSA-SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1997; pp. 131–147. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).