Background

Menopause is a significant life stage for women worldwide although its management is often overlooked in health agendas beyond reproductive age [

1]. By the late 2020s, an estimated 76% of postmenopausal women globally will live in developing regions across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Although menopause can involve severe acute symptoms and pose significant long-term health risks, access to appropriate care remains highly uneven, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where healthcare professionals with specialised expertise in menopause are often lacking, making menopause a pressing global public health issue [

2,

3].

Despite being the most effective intervention for menopause-related conditions, hormone replacement therapy remains underutilized in LMICs due to barriers such as excessive costs and limited access. Exercise has emerged as a promising, cost-effective strategy to reduce the severity of menopausal symptoms and improve quality of life [

1]. Beyond physical benefits, regular exercise can positively impact brain health by modulating mood and neurochemistry. This article critically examines the role of exercise in managing menopausal symptoms for women in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, drawing on evidence from research and reports. It also explores how cultural and religious beliefs influence women’s access to exercise, assesses current policy landscapes and healthcare system gaps, and highlights case examples. Finally, we propose pragmatic, sustainable approaches for integrating exercise into menopause care in culturally appropriate ways, encompassing natural, surgical, and medical menopause from perimenopause to post-menopause.

Asia: Cultural Beliefs, Access to Exercise, and Policy Gaps

In Asia, diverse cultural and religious contexts shape women’s experiences of menopause and their attitudes toward exercise. Many Asian societies traditionally view menopause as a natural life transition rather than a medical condition, which can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, there may be less overt pathologising of menopausal symptoms; on the other, women may feel expected to endure symptoms quietly without seeking help.

Cultural norms and gender roles in parts of Asia have historically deprioritised leisure exercise for midlife women [

6]. For example, confucian-influenced cultures emphasise women’s duties to family and valorise intellectual pursuits over physical activity. In a study of Asian American midlife women reflecting on their heritage, participants felt that “physical activity was perceived to be

not for Asian girls” because traditional values didn’t place importance on women exercising [

7]. Women often put household responsibilities and care of children first, leaving little time for themselves. Additionally, strong notions of modesty and propriety can limit the appropriate activities for women. In South Asian communities, many women are nervous about participating in exercise because certain activities conflict with social expectations of modesty and femininity. High-impact or gym-based exercises, for instance, may be seen as unseemly or too exposing. As a result, Asian women may opt for walking or home-based routines over public sports. One qualitative insight noted that South Asian midlife women would benefit from more culturally tailored support, providing women-only exercise spaces, guidance on suitable exercise forms (e.g. yoga, dance), and community awareness to normalize women’s fitness [

8].

Despite these barriers, traditional Asian practices and perspectives can also facilitate exercise. Yoga, tai chi, qigong, and other mind–body exercises have their origins in Asia and are widely respected [

9]. These gentle forms of activity are often culturally acceptable for older women and have proven benefits for menopause management. For instance, yoga and tai chi classes for middle-aged women have gained popularity in countries like India and China, blending exercise with cultural wellness philosophies. Some Asian cultures frame menopause in a more positive light, such as the Japanese term

konenki which implies a period of renewal and regeneration. In Japan, where diet and lifelong physical activity are emphasised, women historically reported fewer hot flashes and attributed their smoother midlife transition to a healthy lifestyle. Researchers have credited Japanese women’s relative menopause comfort to a combination of diet, regular exercise, universal education, and preventive healthcare traditions. This suggests that integrating exercise into daily life, common in some East Asian contexts, can yield tangible benefits [

4].

Healthcare System Challenges and Policy Gaps in Asia

Across much of Asia, menopause care has not received the policy attention it deserves [

10]. Health systems in low- and middle-income Asian countries traditionally focus on maternal and child health, with limited resources dedicated to older women’s health. As an example, India’s national health programs have long centered on family planning and safe childbirth, resulting in menopausal health being sidelined. There is a pronounced data and research gap on menopausal women in Asia, which hampers evidence-based policy development.

Consequently, few countries have comprehensive guidelines or public initiatives addressing menopause or promoting exercise for midlife women. Where clinical guidelines exist (e.g. the Indian Menopause Society’s recommendation), implementation remains limited [

11]. Social stigma also plays a role: many Asian women hesitate to discuss menopause openly, so they may not seek out exercise programs even if available [

12]. The lack of targeted interventions means women often rely on self-care. Notably, Asian women aware of exercise benefits do treat it as self-care; a study in Saudi Arabia (West Asia) found that participants viewed exercise as a

“valuable self-care practice” during menopause and sought out home exercise videos for guidance. This points to an unmet need for supportive infrastructure. Overall, the Asian context calls for greater policy recognition of menopause as a health priority and culturally sensitive programs that encourage exercise among midlife women.

Africa: Sociocultural Beliefs, Stigma, and Systemic Challenges

African women experience menopause against a backdrop of varied cultural beliefs – ranging from reverence for older women’s wisdom to stigma and misconceptions. In many parts of Africa, menopause has traditionally been a private matter, not openly discussed, which affects how women cope and whether they engage in health-seeking behaviours like exercise [

13]. As activist Sue Mbaya noted,

“negative cultural beliefs about menopause” in some African communities fuel stigma, with menopausal women unfairly deemed “unattractive” or “incapable”. This stigma can isolate women and discourage them from participating in public activities, including exercise groups. Indeed, qualitative studies in countries like Zimbabwe and South Africa revealed many women had received little information about menopause and felt they simply had to “endure” the physical and psychological symptoms in silence [

14]. Such attitudes reflect a gap in education and support. However, Africa is culturally diverse, and positive perspectives upon which to build. In numerous African societies, postmenopausal women attain

greater social freedom and authority, no longer bound by certain reproductive-related restrictions. For example, a woman beyond childbearing age may enjoy more respect in some Islamic African communities and parts of sub-Saharan Africa. She can take on leadership roles within the family or community [

15].

Anthropological accounts from West Africa describe “menopausal matriarchs” who become key decision-makers and custodians of knowledge in their communities. This elevated status could be leveraged to engage older women in community wellness initiatives, as they may influence and mentor younger women. Physical activity patterns in Africa are also shaped by lifestyle and beauty ideals. In rural areas, women’s daily lives often involve substantial physical labour (farming, fetching water, etc.), which can maintain fitness but is not usually framed as exercise. In urban settings, more sedentary lifestyles prevail, yet formal exercise is not widespread, especially among older women. Social determinants play a role: one study noted that in Ghana, cultural perceptions of body image influence postmenopausal women’s activity levels. If a fuller figure is associated with status or health, women might be less motivated to exercise for weight control, highlighting the need to tailor messages about fitness in culturally relevant terms. Moreover, common barriers such as time constraints and lack of facilities are pronounced for African women. Women often prioritize family needs and may have limited leisure time or safe spaces to exercise [

16].

Healthcare and Policy Context in Africa

Menopause has only recently started to gain visibility on the policy radar in Africa. Most African health systems face competing urgent issues (infectious diseases, maternal mortality, etc.), and menopause care has been largely neglected. As a result, there is minimal government programming for menopause; few clinics specialise in midlife women’s health, and healthcare providers may receive little training on managing menopause beyond offering hormone therapy if available. This lack of structured support means that interventions like exercise are not systematically promoted. The situation is beginning to change: grassroots movements and NGOs are spearheading a “menopause revolution” in parts of Africa. They emphasise awareness, destigmatisation, and lifestyle management. In countries such as South Africa and Uganda, new menopause societies and support networks are forming. However, large gaps remain – especially in rural areas where information is scarce and in health policies that rarely mention menopause. The need for context-specific research is acute; as Mbaya observes, sub-Saharan Africa suffers from

“low levels of development, competing needs and lower investment in research” on menopause [

17].

Addressing these gaps will require including menopause in national health strategies and recognizing that simple lifestyle interventions like exercise can have outsized benefits for this population of women who are living longer than ever before.

Middle East: Traditions, Taboos, and Opportunities for Exercise

In the Middle East (including North Africa and West Asia), women’s access to exercise during menopause is influenced by conservative social norms and religious practices. Many countries in this region have strong traditions around gender roles and modesty, which can create specific challenges for women’s physical activity. For example, gender segregation and dress codes in conservative societies mean women often need women-only spaces or appropriate attire to exercise comfortably. A systematic overview of 17 Middle East and North Africa [

18] countries identified

gender and cultural norms as among the most commonly reported barriers to physical activity for women [

19]. Simply put, being female and of advanced age in these societies is associated with less exercise, in part because older women are expected to remain home or are not encouraged to engage in sport. Practical hurdles such as lack of female gyms, limited time due to family duties, and even harsh climate (extreme heat) further compound the issue. Cultural and religious beliefs can both hinder and help menopausal women seeking exercise. On one side, menopause remains a sensitive or even taboo topic in parts of the Middle East. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, many women silently endure menopausal changes due to cultural taboos and fear of stigma. This silence can prevent them from seeking group support or asking doctors about non-pharmacological strategies like exercise. Interviews with Saudi women revealed concerns about being seen as “old” or less attractive, leading them to keep symptoms private.

On the other side, Islamic teachings provide an opportunity: after menopause, women are relieved from certain religious restrictions (such as fasting during menstruation or observing strict purdah in some interpretations), potentially giving them more freedom to engage in activities outside the home. Many Middle Eastern women view menopause positively as it grants a “relief from menstruation and a newfound freedom to engage in religious activities at any time” [

20]. This positive outlook can be harnessed to encourage postmenopausal women to invest in their health. Indeed, some women in the region are proactively adopting exercise as self-care. The Saudi qualitative study noted that participants embraced holistic health practices – maintaining a balanced diet, regular exercise, meditation, and good sleep – to cope with menopause, often preferring these to medical treatments.

Policy and Health System Gaps in the Middle East

Much like Asia and Africa, the Middle East has only nascent recognition of menopause in health policy. Few Middle Eastern countries have national guidelines or public education campaigns on menopause [

21]. Women in conservative Arab states may have limited access to specialized care; for example, discussion of hormone therapy or menopause management might be minimal during routine clinic visits.

Healthcare providers may not be fully trained to address menopause beyond treating it as a natural stage. In the Saudi study, women reported that doctors seldom brought up menopause management proactively – one noted that her gynaecologist “did not discuss anything about hot flashes or hormonal treatments,” focusing only on issues like screening and pelvic floor exercises [

22]. This indicates a gap in provider engagement and patient counselling. On a policy level, some countries are beginning to include women’s health across the life course in their strategic plans, but implementation is slow. The lack of public conversation is a key issue; normalizing menopause in the Middle East will require breaking the taboo so that women feel comfortable joining exercise classes or advocacy groups. Encouragingly, there are early signs of change – for instance, menopause was brought to the floor of Ghana’s parliament by a politician and is being included in feminist agendas in Africa, and similar advocacy could spread to Middle Eastern contexts through women’s health NGOs or influential figures.

Case Studies: Community Initiatives and Emerging Programs

Despite challenges, innovative programs in all three regions demonstrate how exercise can be woven into menopause support with culturally sensitive approaches (Table 2—Supplementary File) using examples offering learning points. They show that culturally aligned approaches, whether leveraging community solidarity in Africa, workplace infrastructure in Asia, or digital connectivity in the Middle East can successfully integrate exercise into menopause care.

Table 3, indicates gaps where not all women are reached (rural women, those outside formal employment, etc.), and program sustainability can be an issue if reliant on volunteerism or short-term funding. Nonetheless, these cases demonstrate that the barriers to menopausal women exercising can be overcome with creativity and culturally conscious planning.

Integrating Exercise into Menopause Care: Strategies and Recommendations

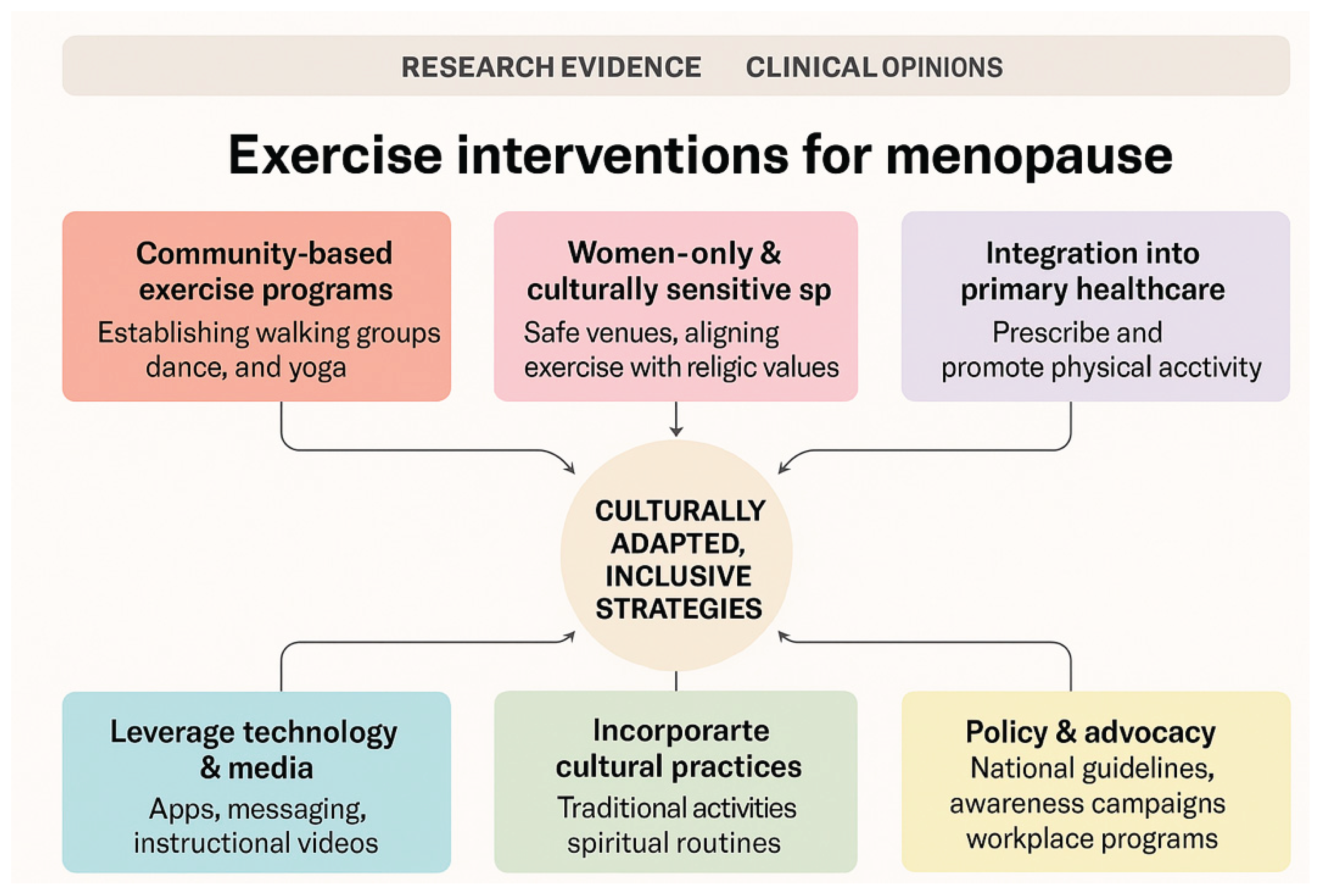

To improve menopause management for women in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, it is crucial to adopt pragmatic, cost-effective, and sustainable approaches that embed exercise into care in culturally appropriate ways. Below are key strategies, informed by the evidence and contexts discussed:

Exercise interventions for menopausal women should be community-based, culturally sensitive, and inclusive of all menopause types, including surgical and medically induced cases. Safe, women-only spaces and culturally adapted activities such as African dance, yoga, or courtyard walking can increase participation, especially in conservative settings. Integration into primary healthcare allows clinicians to prescribe and promote physical activity, supported by toolkits and culturally relevant resources. Technology and media, from SMS reminders to online video content, expand reach and sustain engagement, particularly for women in remote or resource-limited areas. Policy and advocacy efforts must formalise exercise promotion in national health strategies, ensuring structural support, workplace accommodations, and recognition of menopause as a public health and human rights priority.

Figure 1.

indicates a visual of the framework MARIE exercise framework that is proposed to be used to develop interventions for people experiencing perimenopausal, menopausal and post-menopausal.

Figure 1.

indicates a visual of the framework MARIE exercise framework that is proposed to be used to develop interventions for people experiencing perimenopausal, menopausal and post-menopausal.

Conclusions

Exercise is a powerful implement in the menopausal toolkit – improving physical symptoms, bolstering brain health, and empowering women to take charge of their wellbeing. For women in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, maximising this tool requires understanding and respecting cultural contexts. The evidence base shows that regular physical activity can alleviate depression, anxiety, insomnia, fatigue and protect long-term cognitive health. The sociological lens reminds us that a one-size approach will not fit all; programs must negotiate gender norms, modesty, and differing attitudes toward menopause. Current efforts may offer blueprints for progress although more culturally sensitive research on building effective exercise programs are needed, which can aid to fill policy voids and healthcare gaps. By implementing community-grounded and culturally sensitive strategies, stakeholders, healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers, can help women in these regions navigate menopause with greater ease and dignity. Integrating exercise into menopause care is not just about mitigating symptoms; it is about affirming women’s agency and quality of life in the post-reproductive years. In every village, city, and society, a woman’s midlife can be made healthier and happier by the simple act of moving her body and it is time for our health systems to move with women.

Author Contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and conceptualised this paper as part of the MARIE project. GD wrote the first draft and furthered by all other authors. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

NIHR Research Capability Fund.

Consent to Participate

No participants were involved within this paper.

Consent for Publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

Availability of Data and Material

The data shared within this manuscript is publicly available.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

MARIE collaboration. Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Kathleen Riach, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dassanayake, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Jeevan Dhanarisi, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Andy Fairclough, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Clementine Kanazayire, Jean Damascene Hanyurwimfura, Nwankwo Helen Chinwe, Stella Matutina Isingizwe, Jean Marie Vianney Kabutare, Dorcas Uwimpuhwe, Melanie Maombi, Ange Kantarama, Uchechukwu Kevin Nwanna, Benedict Erhite Amalimeh, Theodomir Sebazungu, Elius Tuyisenge, Yvonne Delphine Nsaba Uwera, Emmanuel Habimana, Nasiru Sani and Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Ramiya Palanisamy, Victoria Corkhill, Kingshuk Majumder, Bernard Mbwele, Om Kurmi, Irfan Muhammad, Rabia Kareem, Lamiya Al-Kharusi, Nihal Al-Riyami, Rukshini Puvanendran, Farah Safdar, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Manisha Mathur, Raksha Aiyappan.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

References

- Xu H, Liu J, Li P, Liang Y. Effects of mind-body exercise on perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause 2024, 31, 457–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington RB, Harvey N, Larkins S, Redman-MacLaren M. Family planning in Pacific island countries and territories (PICTs): a scoping review. PloS one 2021, 16, e0255080. [Google Scholar]

- Delanerolle G, Phiri P, Elneil S, Talaulikar V, Eleje GU, Kareem R, et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health 2025, 13, e196–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-González C, Cueto-Ureña C, Cantón-Habas V, Ramírez-Expósito MJ, Martínez-Martos JM. Healthy aging in menopause: prevention of cognitive decline, depression and dementia through physical exercise. Physiologia 2024, 4, 115–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han B, Duan Y, Zhang P, Zeng L, Pi P, Chen J, et al. Effects of exercise on depression and anxiety in postmenopausal women: a pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC public health 2024, 24, 1816. [Google Scholar]

- Zou P, Luo Y, Wyslobicky M, Shaikh H, Alam A, Wang W, et al. Menopausal experiences of South Asian immigrant women: a scoping review. Menopause 2022, 29, 360–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im EO, Ko Y, Hwang H, Chee W, Stuifbergen A, Lee H, et al. Asian American midlife women’s attitudes toward physical activity. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 2012, 41, 650–8. [Google Scholar]

- Darko, N. South Asian and BME migrant women’s experiences of culturally tailored, women-only physical activity programme for improving participation, social isolation and wellbeing. Engaging Black and Minority Ethnic Groups in Health Research: Policy Press; 2021. p. 93-106.

- Shorey S, Ang L, Lau Y. Efficacy of mind–body therapies and exercise-based interventions on menopausal-related outcomes among Asian perimenopause women: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and synthesis without a meta-analysis. Journal of advanced nursing 2020, 76, 1098–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey S, Ng ED. The experiences and needs of Asian women experiencing menopausal symptoms: a meta-synthesis. Menopause 2019, 26, 557–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeta M, Digumarti L, Agarwal N, Vaze N, Shah R, Malik S. Clinical practice guidelines on menopause:* An executive summary and recommendations: Indian Menopause Society 2019–2020. Journal of Mid-life Health 2020, 11, 55–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Q, Gu J, Huang J, Zhao P, Luo C. “ They see me as mentally ill”: the stigmatization experiences of Chinese menopausal women in the family. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Matina SS, Mendenhall E, Cohen E. Women’ s experiences of menopause: A qualitative study among women in Soweto, South Africa. Global Public Health 2024, 19, 2326013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew S, Khutsoane K, Buwu N, Gregson CL, Micklesfield LK, Ferrand RA, et al. Improving experiences of the menopause for women in Zimbabwe and South Africa: co-producing an information resource. Social Sciences 2022, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidou S, Verpoorten M. Only women can whisper to gods: Voodoo, menopause and women’s autonomy. World Development 2019, 119, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah Bonsu I, Myezwa H, Brandt C, Ajidahun AT, Moses MO, Asamoah B. An exploratory study on excess weight gain: experiences of postmenopausal women in Ghana. Plos one 2023, 18, e0278935. [Google Scholar]

- Kyomuhendo, C. Managing Menopause in the Workplace: Strategies for Professional Success and Support in Ugandan Higher Institutions of Learning. Available at SSRN 4979872. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Casas, X. How the’Green Wave’Movement Did the Unthinkable in Latin America. International New York Times.

- Chaabane S, Chaabna K, Doraiswamy S, Mamtani R, Cheema S. Barriers and facilitators associated with physical activity in the Middle East and North Africa region: a systematic overview. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa M, Zaman KT, Ahmad T, Batool A, Ghazali M, Ahmed N, editors. Religion and women’s intimate health: towards an inclusive approach to healthcare. Proceedings of the, 2021.

- Shahzad D, Thakur AA, Kidwai S, Shaikh HO, AlSuwaidi AO, AlOtaibi AF, et al. Women’s knowledge and awareness on menopause symptoms and its treatment options remains inadequate: a report from the United Arab Emirates. Menopause 2021, 28, 918–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qutob RA, Alaryni A, Alsolamy EN, Al Harbi K, Alammari Y, Alanazi A, et al. Attitude, practices, and barriers to menopausal hormone therapy among physicians in Saudi Arabia. Cureus.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).