Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Working Principle

2.1. The Basic Concepts and Processes

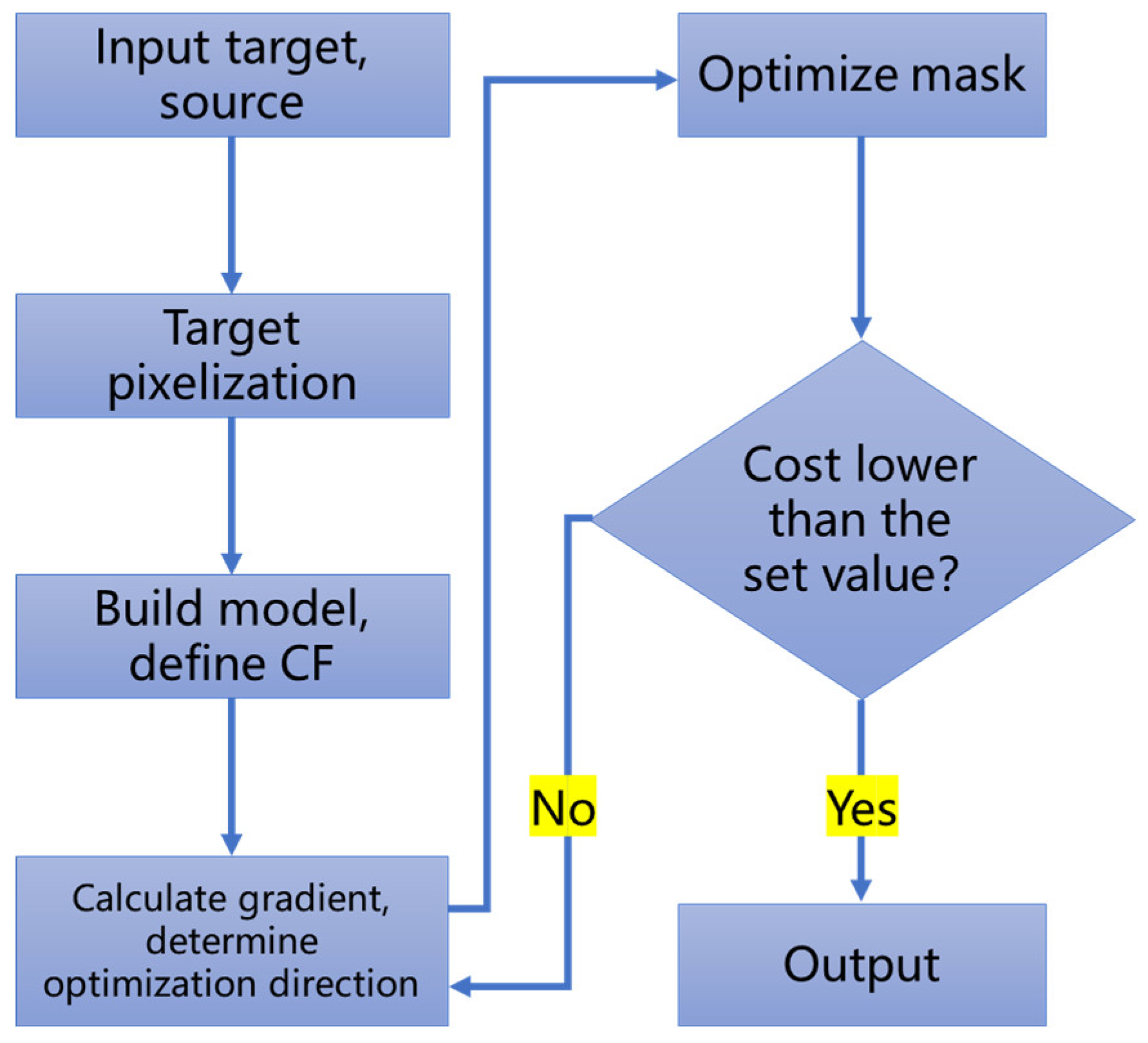

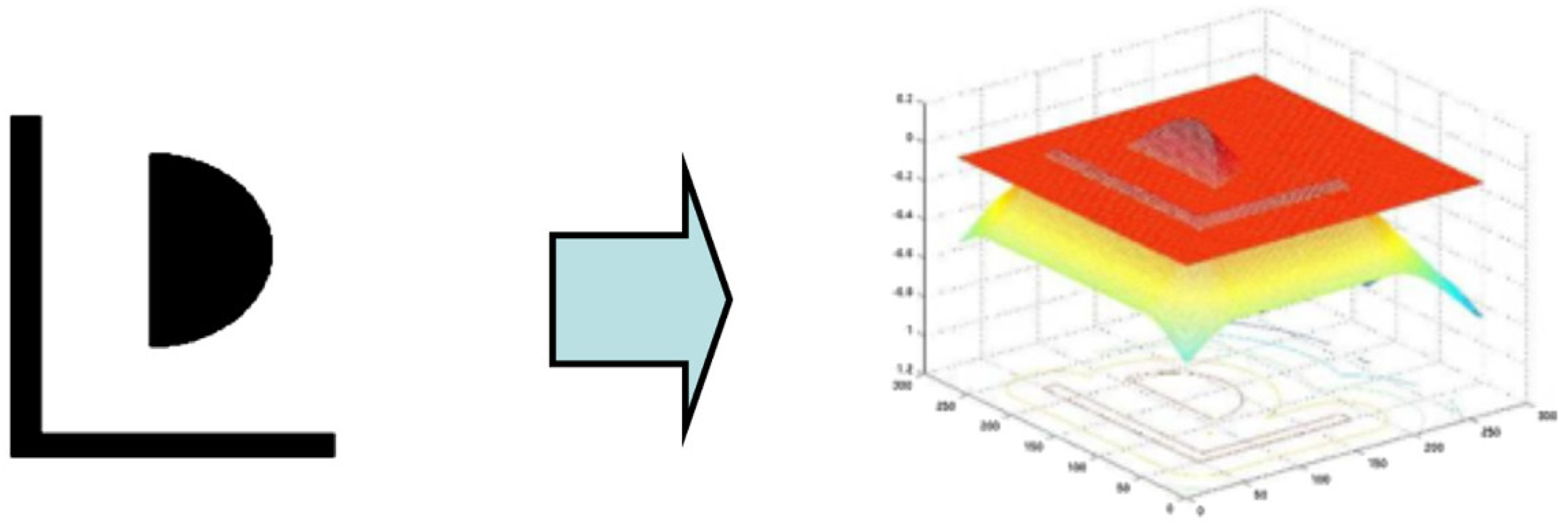

2.2. Mathematical Description and Algorithms

2.3. Four Mainstream Implementation Methods

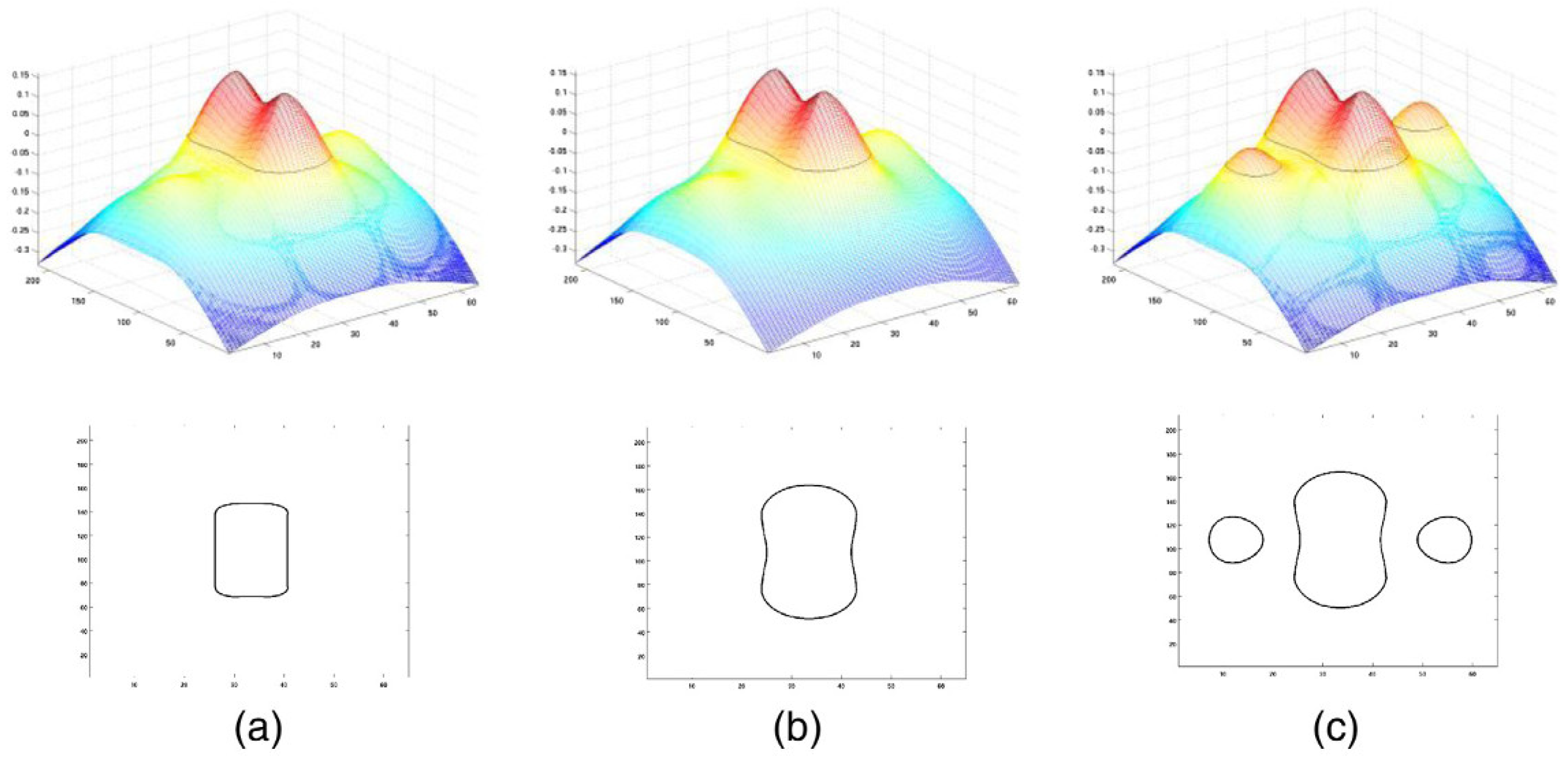

2.3.1. Level-Set Method

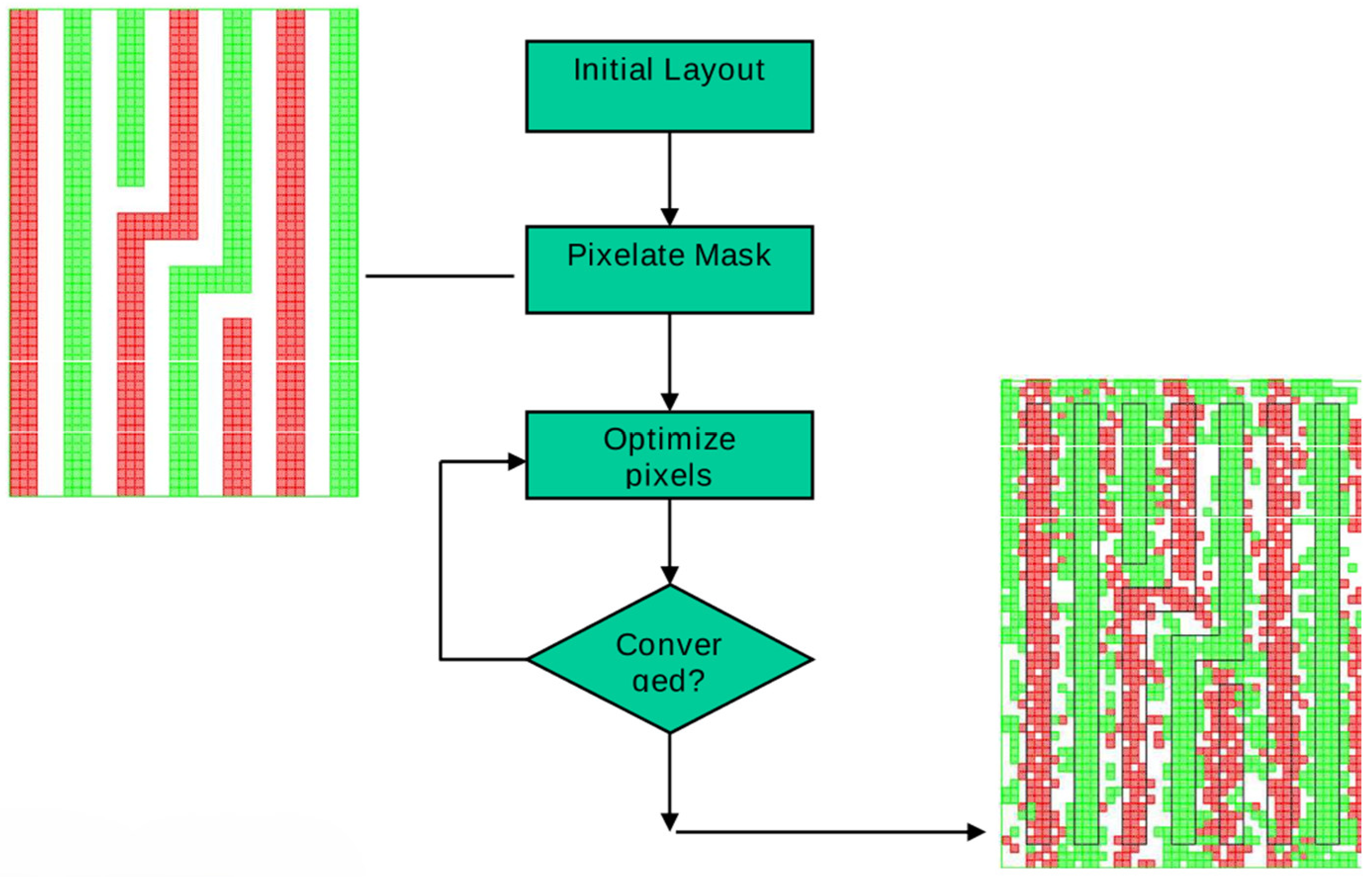

2.3.2. Intel Pixelated ILT

2.3.3. Calculating Curvilinear ILT in Frequency-Domain

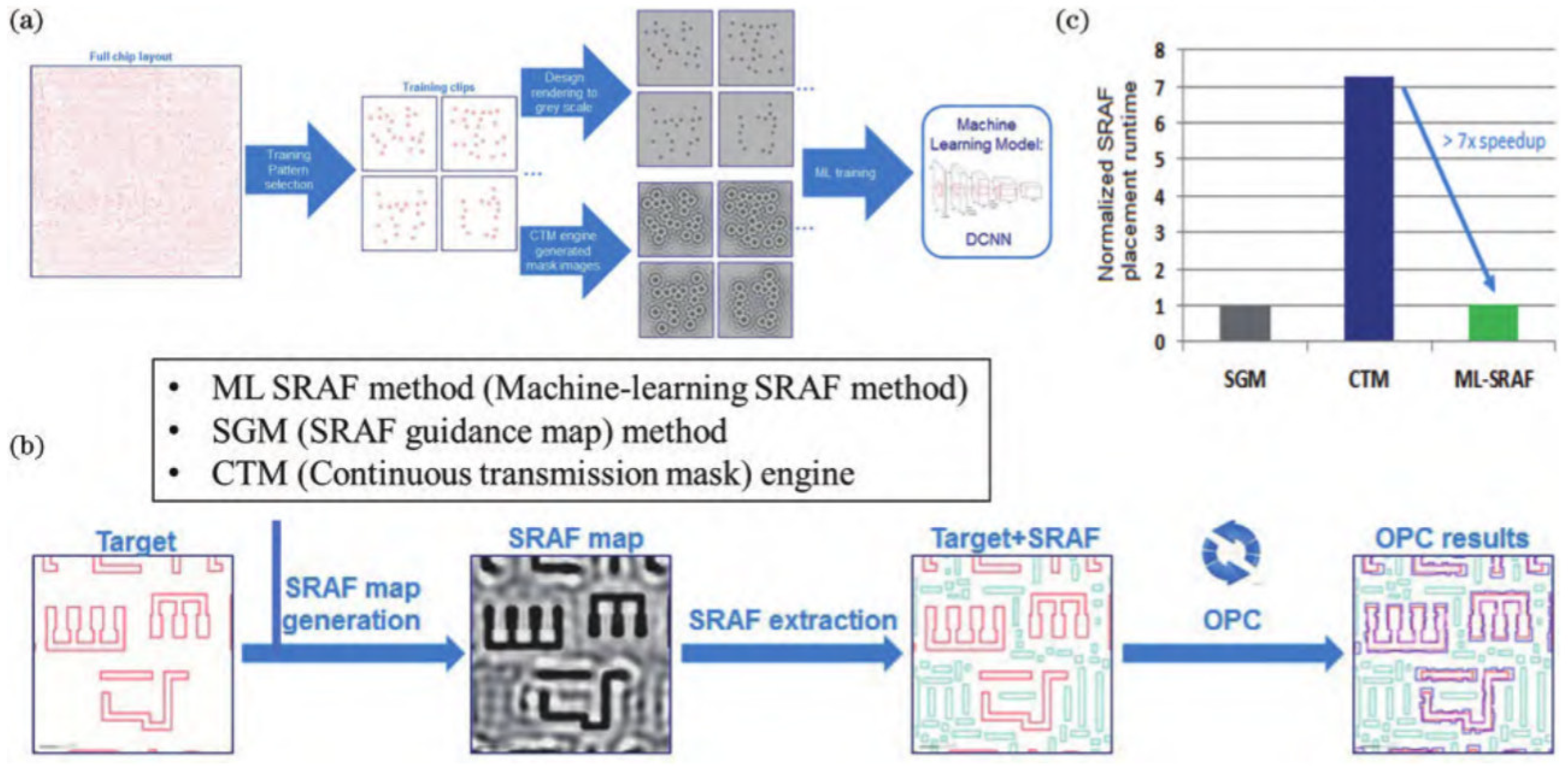

2.3.4. ILT Method Combined with Machine Learning

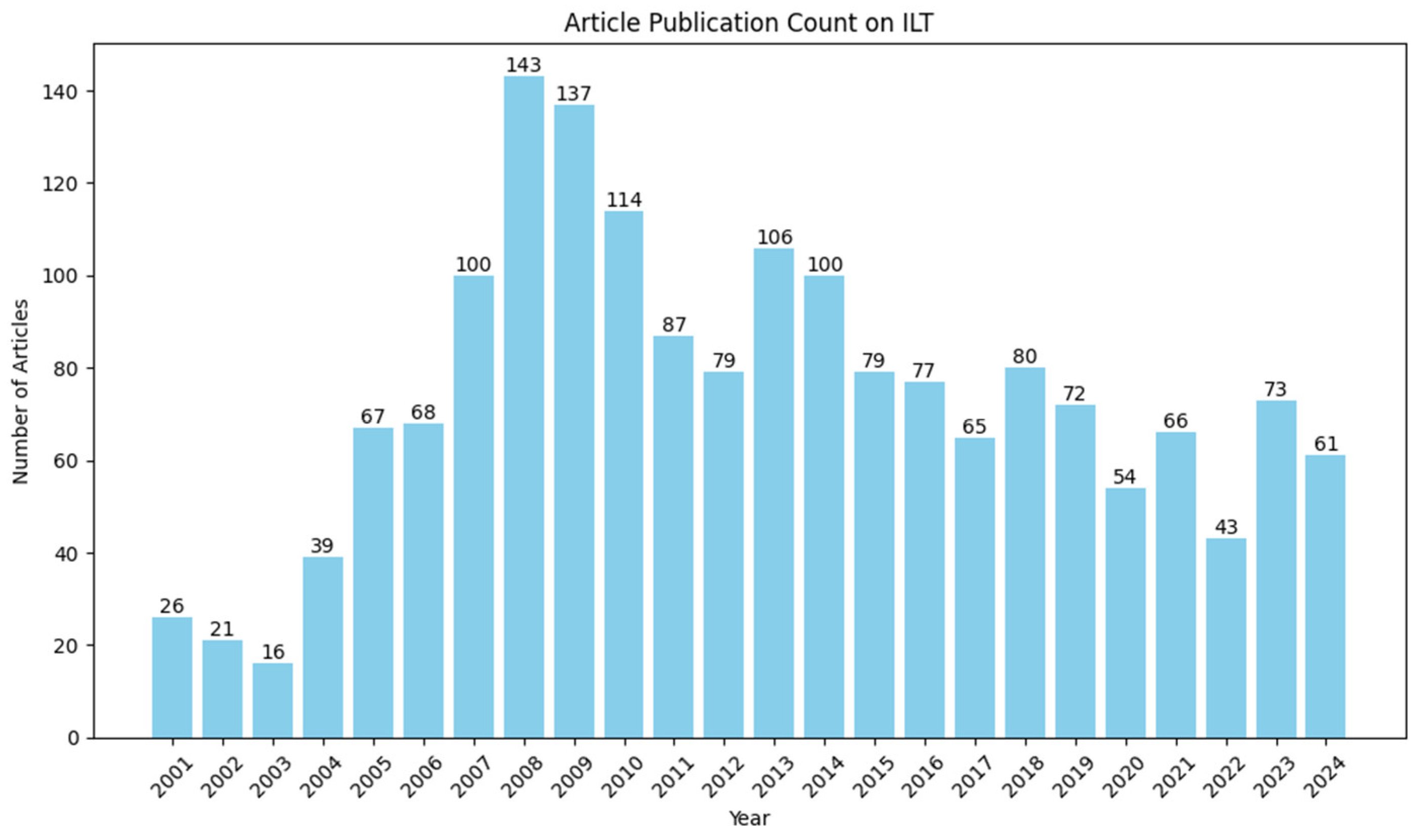

3. Progress in Research on ILT

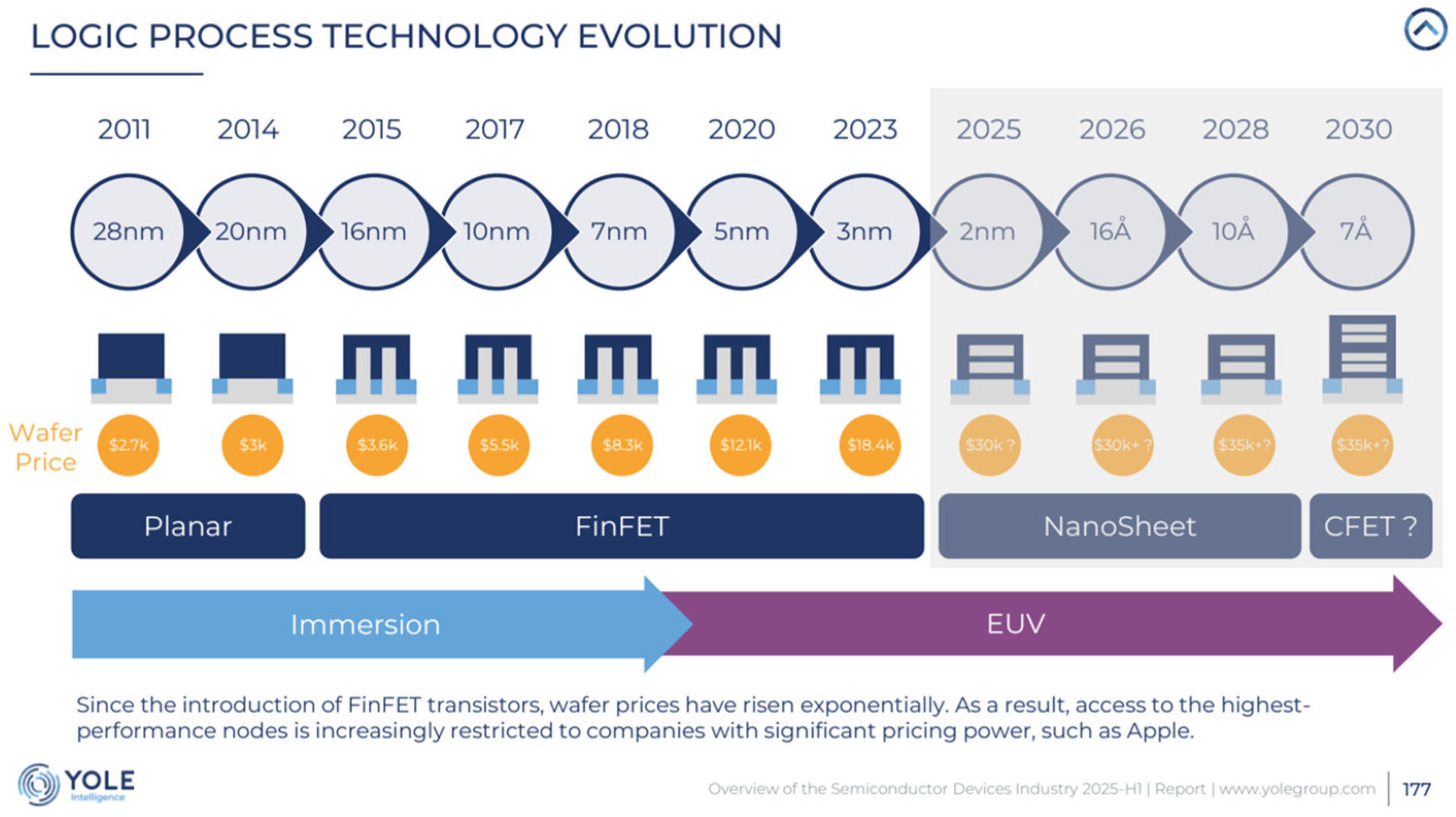

3.1. Evolution of Lithography Techniques

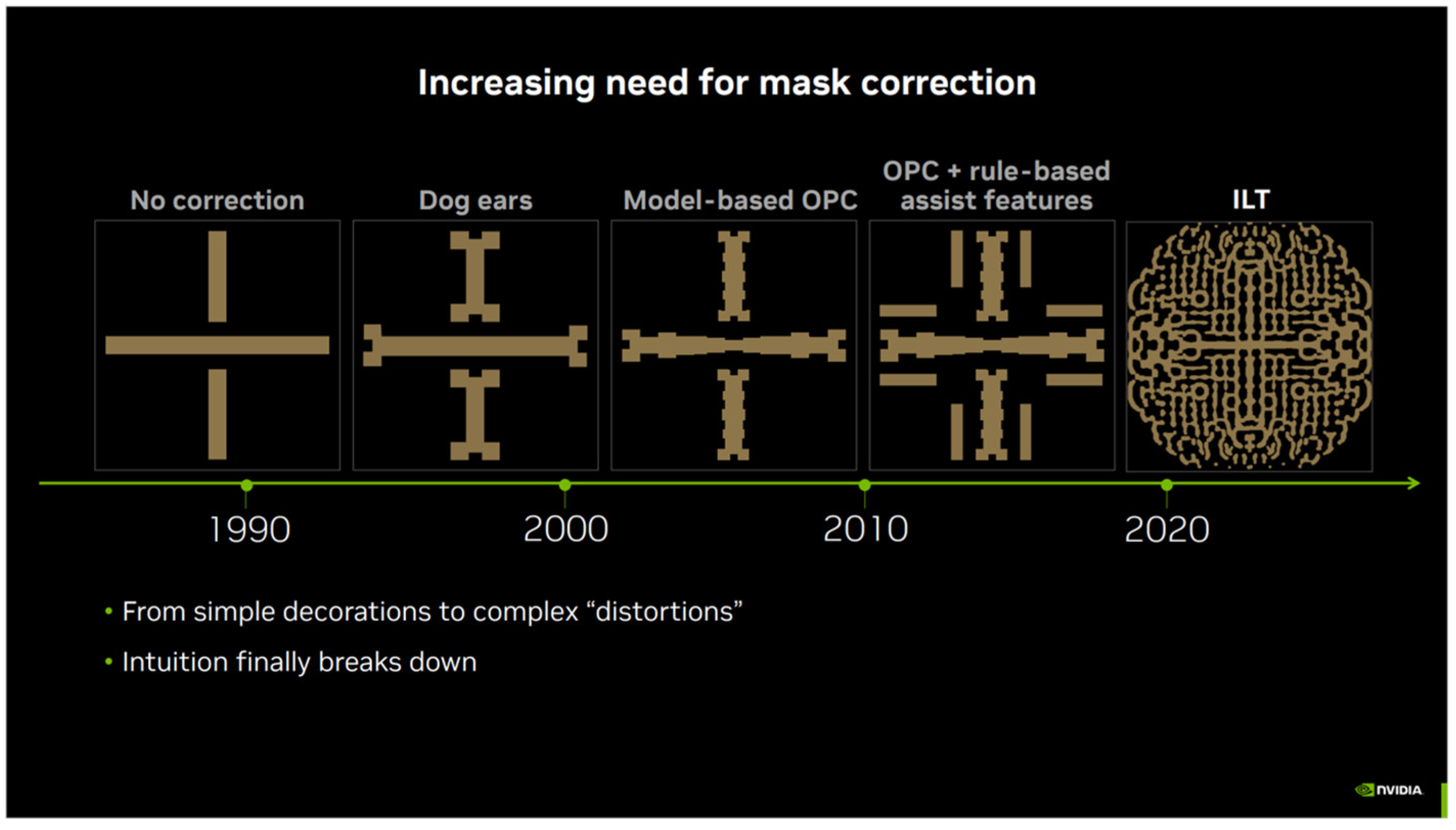

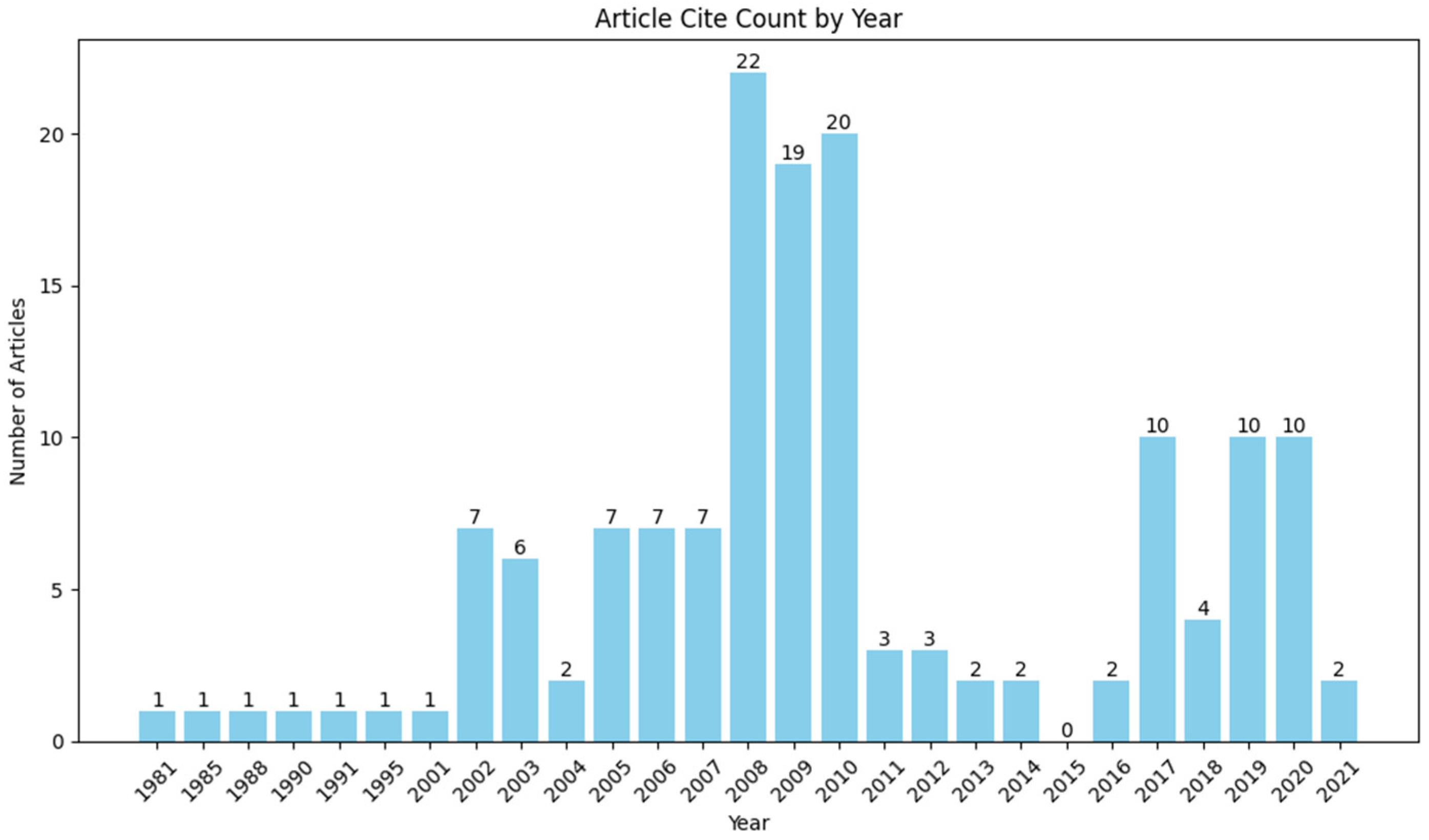

3.2. Research History of ILT

3.3. Important Milestone Events

3.3.1. Concept Proposal

3.3.2. Formal Naming

3.3.3. Level-Set Method

3.3.4. Pixelated Masking Technology

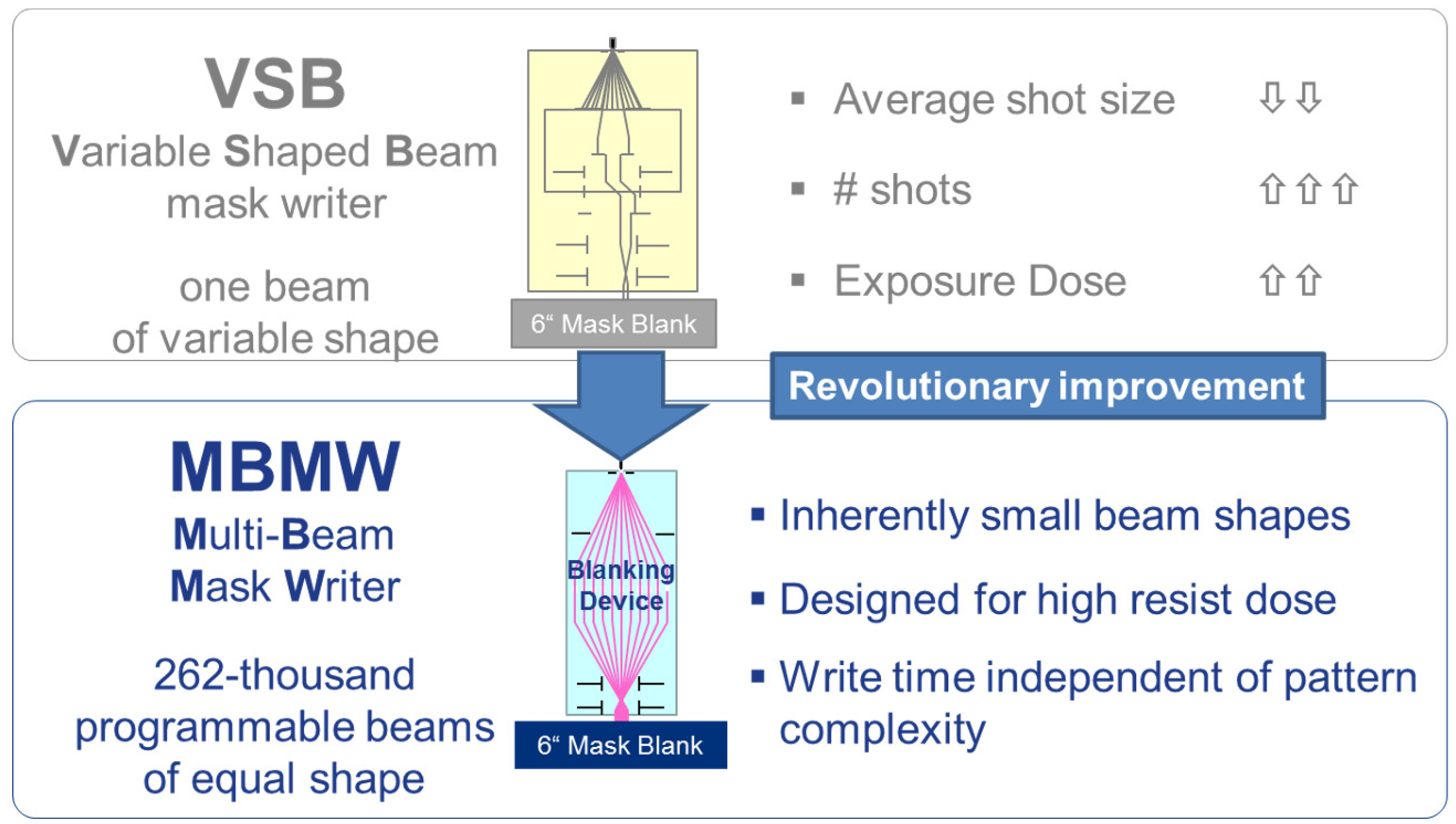

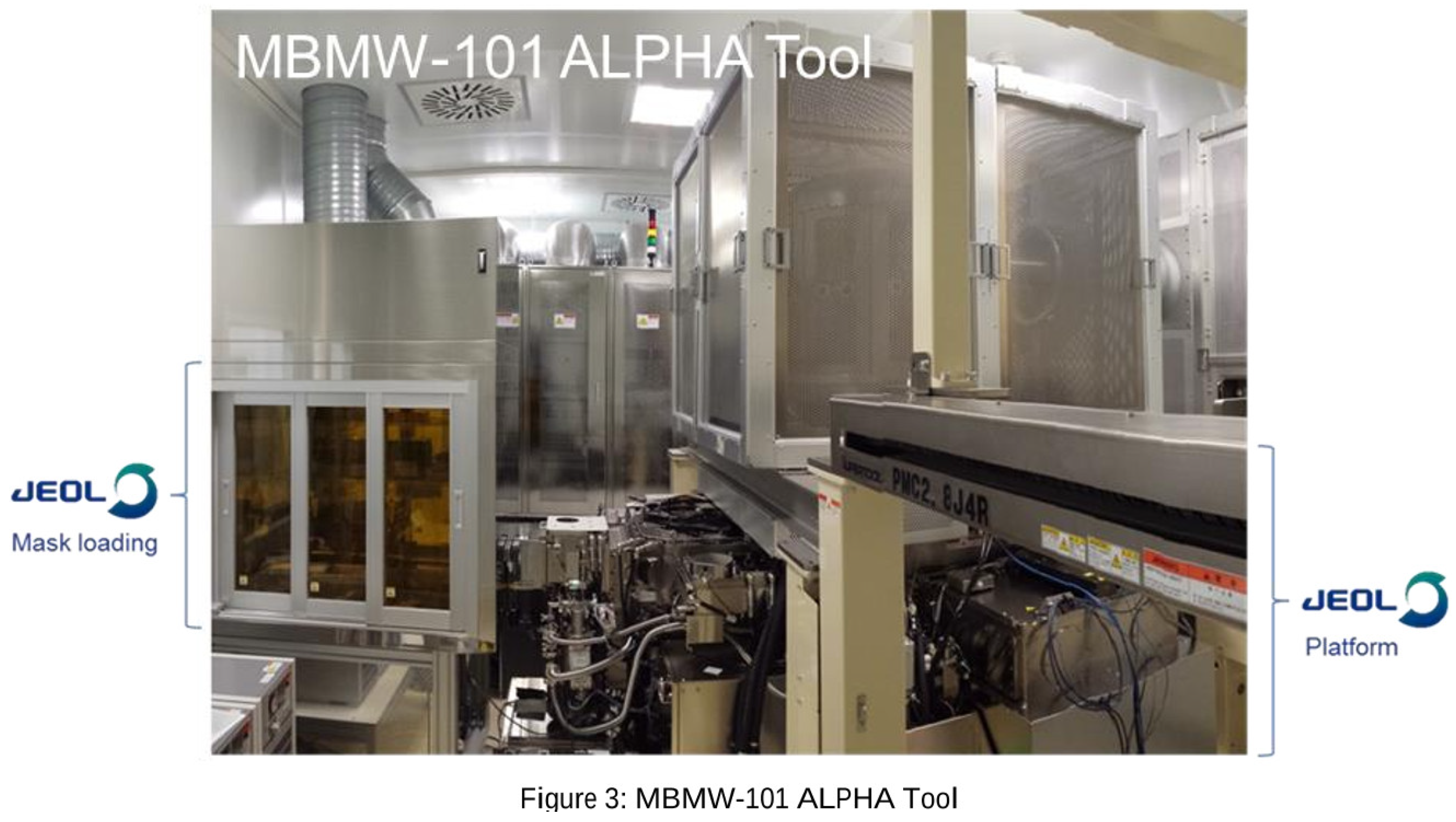

3.3.5. Multi-Beam Mask Writer

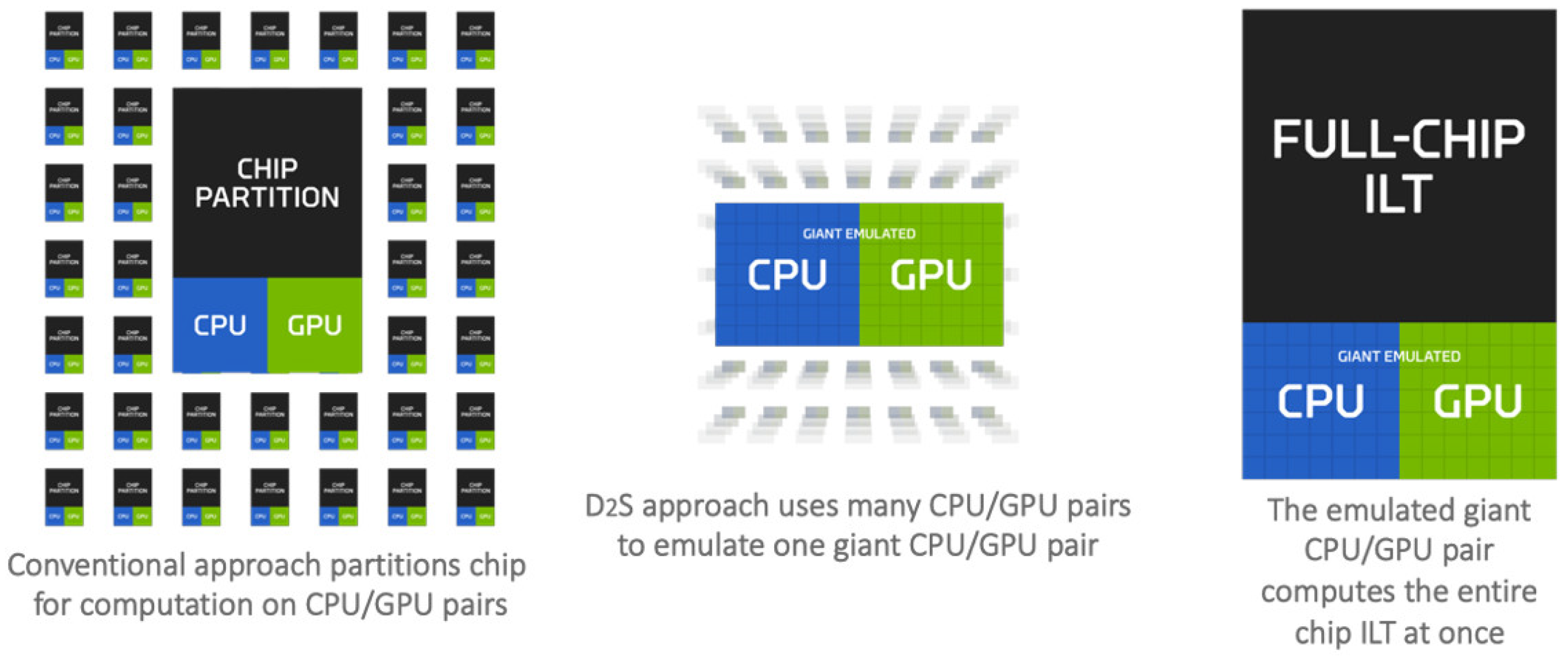

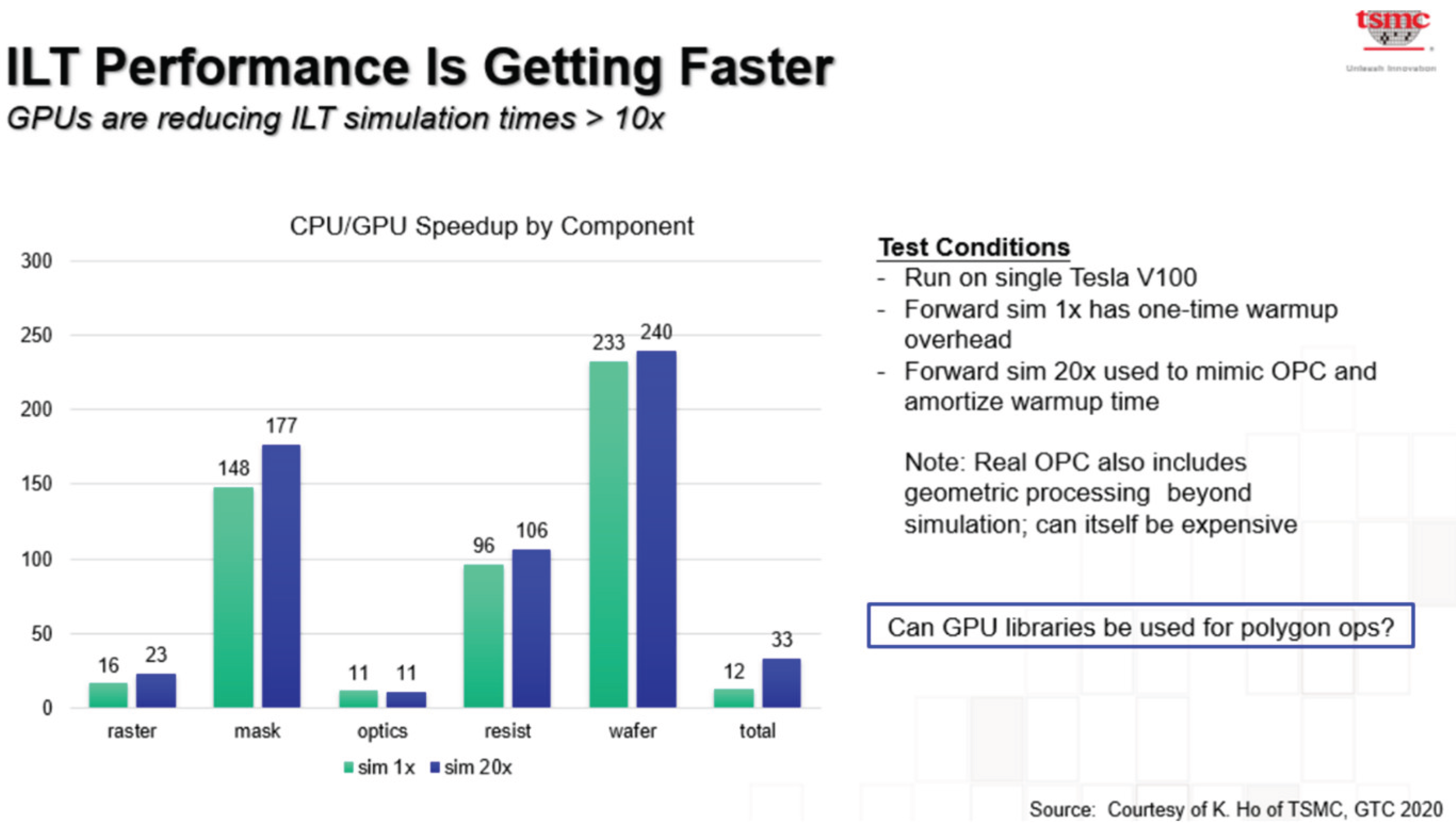

3.3.6. GPU Acceleration

3.3.7. Machine Learning Assistance

3.3.8. Full-Chip Reality

4. Technical Advantages and Application Status

4.1. Break the Resolution Limit

4.2. High-Precision Pattern Fidelity

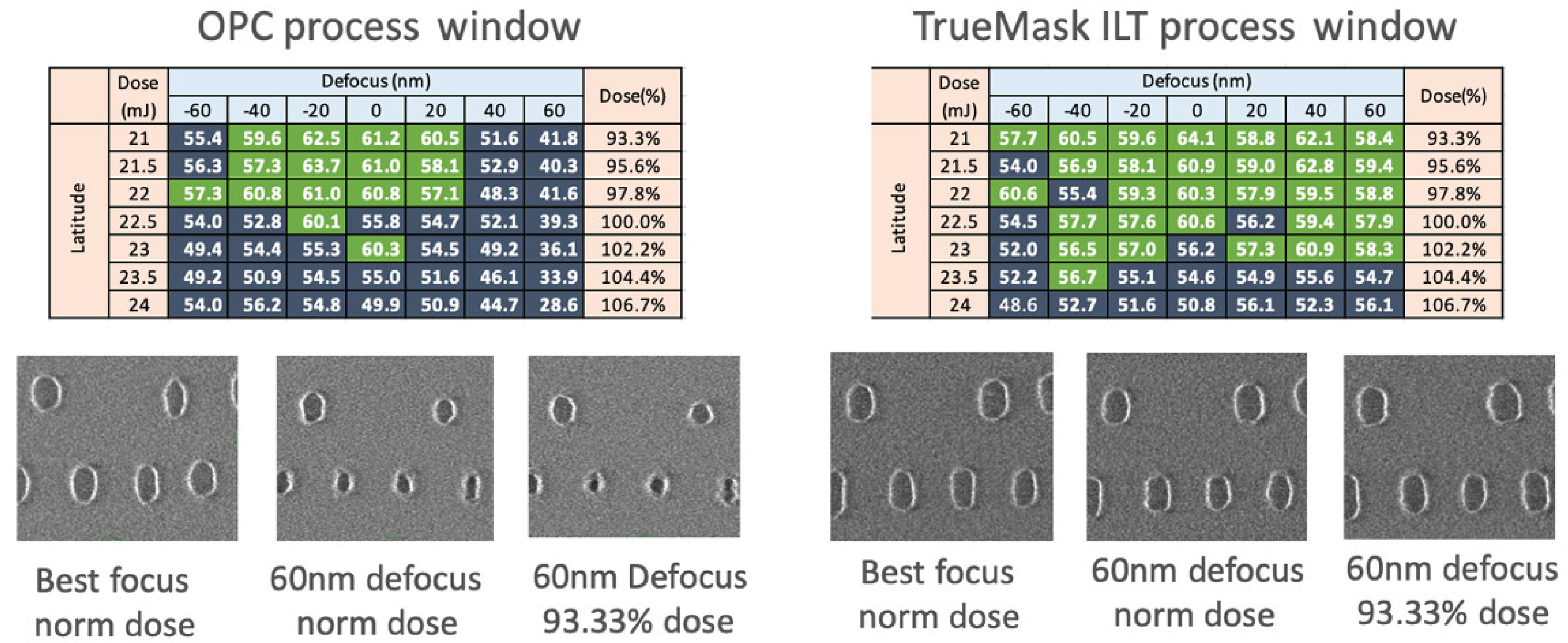

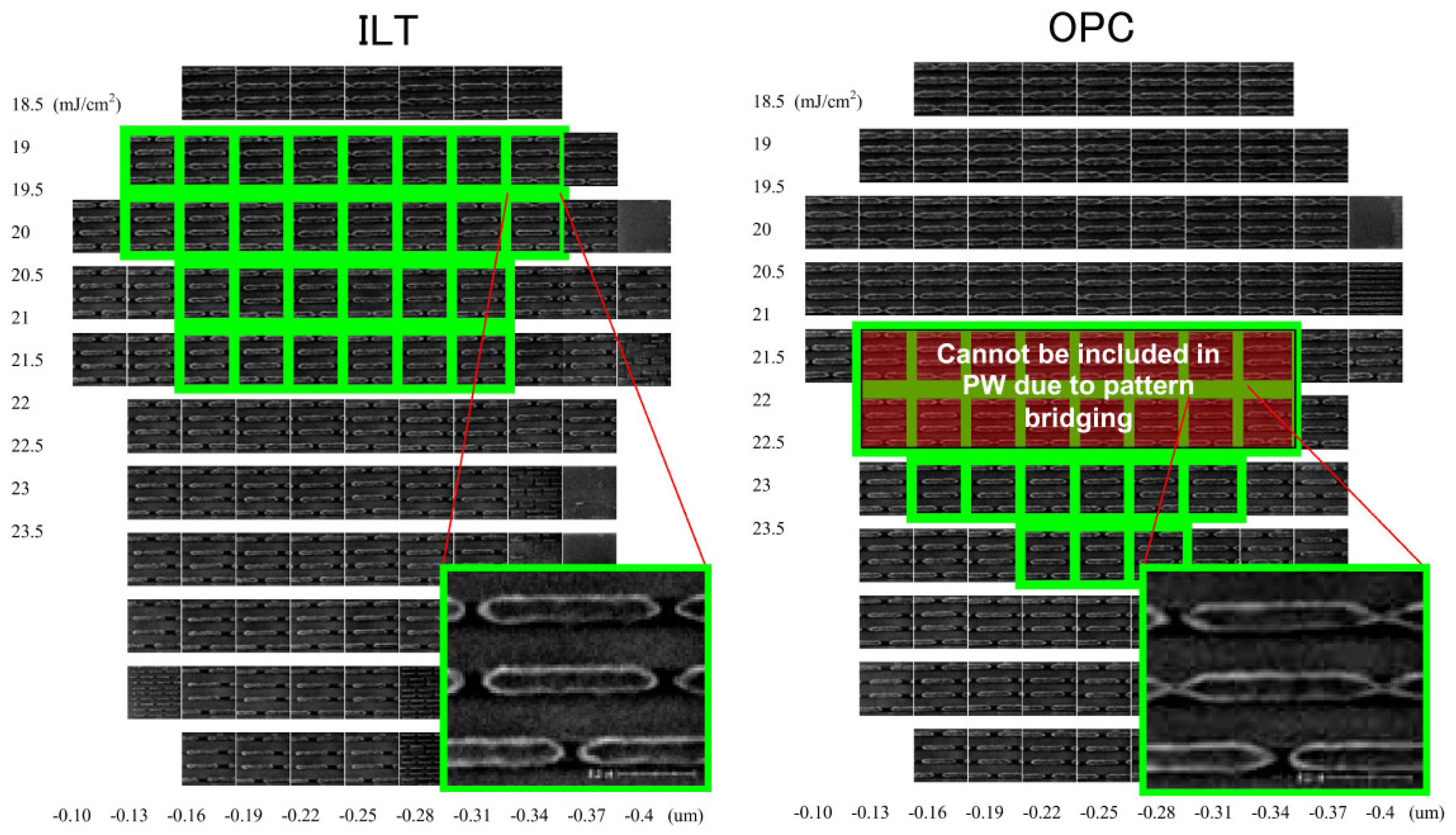

4.3. Enhancements in Process Windows

4.3. Applications Status of ILT

5. Challenges and Limitations

5.1. Low Computational Efficiency

5.2. Mask Manufacturing Difficulty

5.3. Inadequate Accuracy of the Model

5.4. Complex ILT Mask Needs to Meet the Mask Manufacturing Rules

5.5. Integration with Existing Manufacturing Processes

6. Future Development Directions

6.1. Hybrid Optimization Strategy

6.2. AI Driven Optimization

6.3. GPU Acceleration Will Become the Main Beam

6.4. Cross-Scale Collaborative Design

6.5. Multi-Beam Writer Is More Mature

6.6. Digital Twin Accelerating the Advancement of ILT

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ILT | Inverse Lithography Technology |

| IC | integrated circuit |

| OPE | optical proximity effect |

| OPC | optical proximity correction |

| RB-OPC | rule-based OPC |

| MB-OPC | model-based OPC |

| SRAF | sub-resolution assist feature |

| EPE | edge placement error |

| RET | resolution enhancement technique |

| PB-OPC | pixel based OPC |

| CF | cost function |

| DMDL | dual-channel model-driven deep learning |

| HDP | hybrid dynamic priority |

| SMO | Source mask optimization |

| S-Litho | Sentaurus Lithography |

| POCS | projection onto convex sets |

| SGD | stochastic gradient descent |

| Alt-PSMs | alternating phase-shift masks |

| MRC | mask-rule checking |

| MCNN | Model-driven Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DL | deep learning |

| CNN | convolutional neural networks |

| VAE | variational autoencoder |

| GAN | generative adversarial network |

| EUVL | Extreme ultraviolet lithography |

| EBL | Electron beam lithography |

| NIL | Nanoimprint lithography |

| J-FIL | Jet and Flash Imprint Lithography |

| DUV | deep ultraviolet |

| VSB | variable shaped beam |

| SMO | source-mask optimization |

| MBMW | multi-beam mask writers |

| DCCS | dense concentric circle sampling |

| MWCO | Mask-Wafer Co-Optimization |

| CDP | computational design platform |

| RL | reinforcement learning |

| DPT | Double Patterning Technology |

| DoF | depth of focus |

| CD | critical dimension |

| EL | exposure latitude |

| GPGPU | general-purpose graphics-processing unit |

| EUV | extreme ultraviolet |

| HSMO | hybrid source mask optimization |

| CBCT | cone-beam computed tomography |

| DT | Digital twins |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

| DPK | deep learning kit |

References

- Sreenivasan, S.V. Nanoimprint Lithography Steppers for Volume Fabrication of Leading-Edge Semiconductor Integrated Circuits. Microsyst Nanoeng 2017, 3, 17075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek K Singh Accelerating Computational Lithography: Enabling Our Electronic Future; 2023.

- E: K Singh Accelerating Computational Lithography, 2023.

- Wang, F.; Wei, J.; Wang, C.; Jiang, M.; Mu, Y.; Yu, C.; Liu, R.; Li, F.; Fan, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Progress in Inverse Lithography Technology. Laser & Optoelectronics Progress 2024, 61, 2100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Yuan, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.C.; Li, A.; Qiao, L.; Yang, H. Effective Multi-Objective Inverse Lithography Technology at Full-Field and Full-Chip Levels with a Hybrid Dynamic Priority Algorithm. Opt Express 2023, 31, 19215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuoxian Chen Research on Inverse Lithography Technology Based On Generative Adversarial Network, Zhejiang University: Hang Zhou, 2024.

- Ma, X.; Arce, G.R. Computational Lithography; Wiley, 2010; ISBN 9780470596975.

- Kim, H.-B.; Ahn, C.-N.; Ji-Suk, H.; Yune, H.-S.; Koo, Y.-M.; Baik, K.-H. Optical Proximity Correction Using Diffused Aerial Image Model. Technical report of IEICE. ICD,Technical report of IEICE. ICD 1999.

- Schellenberg, F.M.; Toublan, O.; Capodieci, L.; Socha, B. Adoption of OPC and the Impact on Design and Layout. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th conference on Design automation - DAC ’01; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2001; pp. 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, L. (Leo) Inverse Lithography Technology: 30 Years from Concept to Practical, Full-Chip Reality. Journal of Micro/Nanopatterning, Materials, and Metrology 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Dong, L. Mask Optimization Approaches in Optical Lithography Based on a Vector Imaging Model. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 2012, 29, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, A.I.; Xiaojing, S.U.; Yayi, W.E.I. Research Progress of Inverse Lithography Technology. Journal of Electronics & Information Technology. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wong, N.; Lam, E.Y. Level-Set-Based Inverse Lithography for Photomask Synthesis. Opt Express 2009, 17, 23690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domnenko, V.; Kuechler, B.; Hoppe, W.; Braam, K.; Cai, H.; Xiao, G.; Selinidis, K.; Poonawala, A. Rigorous ILT Optimization for Advanced Patterning and Design-Process Co-Optimization. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XXXI; Kye, J., Owa, S., Eds.; SPIE, March 20 2018; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Osher, S.; Sethian, J.A. Fronts Propagating with Curvature-Dependent Speed: Algorithms Based on Hamilton-Jacobi Formulations. J Comput Phys 1988, 79, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.S.; Pang, L. Fast Inverse Lithography Technology. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical Microlithography XIX; Flagello, D.G., Ed.; March 10 2006; p. 61541J. [Google Scholar]

- Cecil, T.; Ashton, C.; Irby, D.; Luan, L.; Son, D.H.; Xiao, G.; Zhou, X.; Kim, D.; Gleason, B.; Lee, H.J.; et al. Enhancing Fullchip ILT Mask Synthesis Capability for IC Manufacturability.; 2011; p. 79731C. 17 March 2011.

- Zou, Y.; Deng, Y.; Kye, J.; Capodieci, L.; Tabery, C.; Dam, T.; Aadamov, A.; Baik, K.-H.; Pang, L.; Gleason, B. Evaluation of Lithographic Benefits of Using ILT Techniques for 22nm-Node. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical Microlithography XXIII; Dusa, M. V., Conley, W., Eds.; March 11 2010; p. 76400. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Zheng, X.; Arce, G.R. Fast Inverse Lithography Based on Dual-Channel Model-Driven Deep Learning. Opt Express 2020, 28, 20404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scranton, G.; Bhargava, S.; Ganapati, V.; Yablonovitch, E. Single Spherical Mirror Optic for Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography Enabled by Inverse Lithography Technology. Opt Express 2014, 22, 25027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, B.E.; Sayegh, S.I. Reduction Of Errors Of Microphotographic Reproductions By Optimal Corrections Of Original Masks. Optical Engineering 1981, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashold, K.M.; Saleh, B.E.A. Image Construction through Diffraction-Limited High-Contrast Imaging Systems: An Iterative Approach. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 1985, 2, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, Y.C.; Kailath, T. Phase-Shifting Masks for Microlithography: Automated Design and Mask Requirements. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 1994, 11, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, S.; Saleh, B.; De Leone, R. Binary Image Synthesis Using Mixed Linear Integer Programming. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 1995, 4, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-C.; Lim, S. Resolution Enhancement through Optical Proximity Correction and Stepper Parameter Optimization for 0.12-Μm Mask Pattern. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical Microlithography XII; Van den Hove, L., Ed.; July 26 1999; p. 607. [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann, A.; Fuehner, T.; Schnattinger, T.; Tollkuehn, B. Toward Automatic Mask and Source Optimization for Optical Lithography. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical Microlithography XVII; Smith, B.W., Ed.; May 28 2004; p. 646. [Google Scholar]

- Granik, Y. Solving Inverse Problems of Optical Microlithography. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XVIII; SPIE, May 12 2005; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Poonawala, A.; Milanfar, P. Mask Design for Optical Microlithography—An Inverse Imaging Problem. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2007, 16, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhong, W.; Hu, S.; Gao, J.-R.; Kuang, J.; Miao, J.; Yu, B. A Unified Framework for Simultaneous Layout Decomposition and Mask Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2020, 39, 5069–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Liu, Y.; Hawkinson, C. The Application of a New Stochastic Search Algorithm “Adam” in Inverse Lithography Technology (ILT) in Critical Recording Head Fabrication Process. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XXXIV; Owa, S., Phillips, M.C., Eds.; SPIE, February 22 2021; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, L.; Shamma, N.; Rissman, P.; Abrams, D. Laser and E-Beam Mask-to-Silicon with Inverse Lithography Technology (ILT). In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,25th Annual BACUS Symposium on Photomask Technology; Weed, J.T., Martin, P.M., Eds.; October 21 2005; p. 599221. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Leitermann, W.; Lin, B.; Shieh, M.F.; Sun, J.; Lin, O.; Lin, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Real-World Impact of Inverse Lithography Technology.; Weed, J.T., Martin, P.M., Eds.; 2005; p. 59921Z. 21 October.

- Martin, P.M.; Progler, C.J.; Xiao, G.; Gray, R.; Pang, L.; Liu, Y. Manufacturability Study of Masks Created by Inverse Lithography Technology (ILT). In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,25th Annual BACUS Symposium on Photomask Technology; Weed, J.T., Martin, P.M., Eds.; October 21 2005; p. 599235. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, C.-Y.; Zhang, B.; Guo, E.; Pang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Dai, G. Pushing the Lithography Limit: Applying Inverse Lithography Technology (ILT) at the 65nm Generation. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical Microlithography XIX; Flagello, D.G., Ed.; March 10 2006; p. 61541M. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, L.; Liu, Y.; Abrams, D. Inverse Lithography Technology (ILT): What Is the Impact to the Photomask Industry? In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Photomask and Next-Generation Lithography Mask Technology XIII; Hoga, M., Ed.; May 4 2006; p. 62830X. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Hu, B.; Toh, K.; Bollepalli, S.; Wagner, S.; Borodovsky, Y. Making a Trillion Pixels Dance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of SPIE,Proceedings of SPIE; March 14 2008; p. 69240S.

- Torunoglu, I.; Karakas, A.; Elsen, E.; Andrus, C.; Bremen, B.; Dimitrov, B.; Ungar, J. A GPU-Based Full-Chip Inverse Lithography Solution for Random Patterns.; Rieger, M.L., Thiele, J., Eds.; 2010; p. 764115. 11 March.

- Pang, L.; Russell, E. V.; Baggenstoss, B.; Lee, M.; Digaum, J.; Yang, M.-C.; Ungar, P.J.; Bouaricha, A.; Wang, K.; Su, B.; et al. Study of Mask and Wafer Co-Design That Utilizes a New Extreme SIMD Approach to Computing in Memory Manufacturing: Full-Chip Curvilinear ILT in a Day. In Proceedings of the Photomask Technology 2019; Rankin, J.H., Preil, M.E., Eds.; SPIE, October 3 2019; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, R. Optical Proximity Correction Using a Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network. Journal of Optics 2013, 15, 075708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Shi, Z.; Yan, X.; Geng, Z. SVM Based Layout Retargeting for Fast and Regularized Inverse Lithography. Journal of Zhejiang University SCIENCE C 2014, 15, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Srivatsa, S.; Mantripragada, P.; Upreti, S.; Shravya, K. V. Hybrid OPC Technique for Fast and Accurate Lithography Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2017 30th International Conference on VLSI Design and 2017 16th International Conference on Embedded Systems (VLSID); IEEE, January 2017; pp. 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Arce, G.R. Model-Driven Convolution Neural Network for Inverse Lithography. Opt Express 2018, 26, 32565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Young, E.F.Y. A Fast Machine Learning-Based Mask Printability Predictor for OPC Acceleration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference; ACM: New York, NY, USA, January 21, 2019; pp. 412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Su, J.; Zhang, Q.; Fong, W.; Sun, D.; Baron, S.; Zhang, C.; Lin, C.; Chen, B.-D.; Howell, R.; et al. Machine Learning Assisted SRAF Placement for Full Chip. In Proceedings of the Photomask Technology; Gallagher, E.E., Buck, P.D., Eds.; SPIE, October 16 2017; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Li, M.; Yuan, W.; Yao, L.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, Y.; Kang, X.; Li, A. Optimal Feature Vector Design for Computational Lithography. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XXXII; Kye, J., Owa, S., Eds.; SPIE, March 20 2019; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, W.; Alawieh, M.B.; Lin, Y.; Pan, D.Z. LithoGAN: End-to-End Lithography Modeling with Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th Annual Design Automation Conference 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, June 2, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Rosenbluth, A.E.; Pusuluri, R.M.; Viswanathan, R.; Srinivasan, B.; Mohapatra, N.R. Multiple Stages of Regression to Improve Accuracy in Calibrated Lithography Process Models. Journal of Micro/Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS 2018, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Hu, S.; Ma, Y.; Yang, H.; Ma, X.; Yu, B. Deep Learning-Driven Simultaneous Layout Decomposition and Mask Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC); July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, W. Deep Learning–Based Inverse Method for Layout Design. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2019, 60, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, S.; Pan, J. Fast Mask Optimization Based on Self-Calibrated Convolutions. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Optics and Image Processing (ICOIP 2023); Li, B., Ren, C., Eds.; SPIE, August 1 2023; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Li, S.; Ma, Y.; Yu, B.; Young, E.F.Y. GAN-OPC: Mask Optimization with Lithography-Guided Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 55th Annual Design Automation Conference; ACM: New York, NY, USA, June 24, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Chen, W.; Sun, Q.; Ma, Y.; Yang, H.; Yu, B. DAMO: Deep Agile Mask Optimization for Full-Chip Scale. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2022, 41, 3118–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Rathi, R.; Misharwal, J.; Sinhmar, B.; Kumari, S.; Dalal, J.; Kumar, A. Evolution in Lithography Techniques: Microlithography to Nanolithography. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Verma, J.; Abhinav, V.; Ratnesh, R.K.; Singla, Y.K.; Kumar, V. Advancements in Lithography Techniques and Emerging Molecular Strategies for Nanostructure Fabrication. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zakhor, A. Optimal Binary Image Design for Optical Lithography. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings; Pol, V., Ed.; June 1 1990; Vol. 1264; p. 401. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zakhor, A. Binary and Phase-Shifting Image Design for Optical Lithography. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical/Laser Microlithography IV; Pol, V., Ed.; July 1 1991; pp. 382–399. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbluth, A.E.; Bukofsky, S.J.; Hibbs, M.S.; Lai, K.; Molless, A.F.; Singh, R.N.; Wong, A.K.K. Optimum Mask and Source Patterns to Print a given Shape. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings; Progler, C.J., Ed.; September 14 2001; Vol. 4346; p. 486. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.-H.; Zinn, S.Y.; Ki, W.-T.; Choi, J.-H.; Jeon, C.-U.; Choi, S.-W.; Yoon, H.-S.; Sohn, J.-M.; Oh, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-C.; et al. Manufacturability Evaluation of Model-Based OPC Masks.; Grenon, B.J., Kimmel, K.R., Eds.; 2002; p. 520. 24 December.

- Fuhner, T.; Erdmann, A. Improved Mask and Source Representations for Automatic Optimization of Lithographic Process Conditions Using a Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XVIII; SPIE, May 12 2005; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Granik, Y. Fast Pixel-Based Mask Optimization for Inverse Lithography. Journal of Micro/Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS 2006, 5, 043002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granik, Y. On the Uniqueness of Optical Images and Solutions of Inverse Lithographical Problems. Journal of Micro/Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS 2009, 8, 031405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonawala, A.; Milanfar, P. OPC and PSM Design Using Inverse Lithography: A Nonlinear Optimization Approach. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical Microlithography XIX; Flagello, D.G., Ed.; March 10 2006; p. 61543H. [Google Scholar]

- Poonawala, A.; Borodovsky, Y.; Milanfar, P. ILT for Double Exposure Lithography with Conventional and Novel Materials. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of SPIE,Proceedings of SPIE. Flagello, D.G., Ed.; March 16 2007; p. 65202Q.

- Milanfar, P. Double-Exposure Mask Synthesis Using Inverse Lithography. Journal of Micro/Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS 2007, 6, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Arce, G.R. Generalized Inverse Lithography Methods for Phase-Shifting Mask Design. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical Microlithography XX; Flagello, D.G., Ed.; March 16 2007; p. 65200U. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Arce, G.R. Binary Mask Optimization for Inverse Lithography with Partially Coherent Illumination.; Chen, A.C., Lin, B., Yen, A., Eds.; 2008; p. 71401A. 20 November.

- Ma, X.; Arce, G.R. PSM Design for Inverse Lithography with Partially Coherent Illumination. Opt Express 2008, 16, 20126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodovsky, Y.; Cheng, W.-H.; Schenker, R.; Singh, V. Pixelated Phase Mask as Novel Lithography RET. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings; March 14 2008; Vol. 6924; p. 69240E. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.-H.; Farnsworth, J.; Kwok, W.; Jamieson, A.; Wilcox, N.; Vernon, M.; Yung, K.; Liu, Y.-P.; Kim, J.; Frendberg, E.; et al. Fabrication of Defect-Free Full-Field Pixelated Phase Mask.; 2008; p. 69241G. 14 March.

- Schenker, R.; Bollepalli, S.; Hu, B.; Toh, K.; Singh, V.; Yung, K.; Cheng, W.; Borodovsky, Y. Integration of Pixelated Phase Masks for Full-Chip Random Logic Layers. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings, Optical Microlithography XXI; March 14 2008; p. 69240. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Yu, P.; Pan, D.Z. Enhanced DCT2-Based Inverse Mask Synthesis with Initial SRAF Insertion. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Photomask Technology 2008; Kawahira, H., Zurbrick, L.S., Eds.; October 24 2008; p. 712241. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.-C.; Yu, P.; Chao, H.-Y. Model-Based Sub-Resolution Assist Features Using an Inverse Lithography Method. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Lithography Asia 2008; Chen, A.C., Lin, B., Yen, A., Eds.; November 20 2008; p. 714014. [Google Scholar]

- Jinyu Zhang; Wei Xiong; Yan Wang; Zhiping Yu; Min-Chun Tsai A Highly Efficient Optimization Algorithm for Pixel Manipulation in Inverse Lithography Technique. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design; IEEE, 08; pp. 480–487. 20 November.

- Zhang, J.; Deng, Y.; Xiong, W.; Peng, Y.; Yu, Z. GPU-Accelerated Inverse Lithography Technique. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings; Hosono, K., Ed.; April 24 2009; p. 73790Z. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Shen, S.; Xie, C. Hot-Spots Aware Inverse Lithography Technology. ECS Trans 2009, 18, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiwei, Y.; Zheng, S.; Shanhu, S. Seamless-Merging-Oriented Parallel Inverse Lithography Technology. Journal of Semiconductors 2009, 30, 106002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torunoglu, I.; Karakas, A.; Elsen, E.; Andrus, C.; Bremen, B.; Thoutireddy, P. OPC on a Single Desktop: A GPU-Based OPC and Verification Tool for Fabs and Designers. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Design for Manufacturability through Design-Process Integration IV; Rieger, M.L., Thiele, J., Eds.; March 11 2010; p. 764114. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, E. Regularization in Inverse Lithography: Enhancing Manufacturability and Robustness to Process Variations. ECS Trans 2010, 27, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Lam, E.Y. Machine Learning for Inverse Lithography: Using Stochastic Gradient Descent for Robust Photomask Synthesis. Journal of Optics 2010, 12, 045601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Peng, D.; Hu, P.; Chen, D.; Cecil, T.; He, L.; Xiao, G.; Tolani, V.; Dam, T.; Baik, K.-H.; et al. Optimization from Design Rules, Source and Mask, to Full Chip with a Single Computational Lithography Framework: Level-Set-Methods-Based Inverse Lithography Technology (ILT).; Dusa, M. V., Conley, W., Eds.; 2010; p. 76400O. 11 March.

- Sim, W.; Jung, S.; Lee, H.-J.; Suh, S.; Ser, J.-H.; Choi, S.-W.; Kang, C.-J.; Cecil, T.; Ashton, C.; Irby, D.; et al. Hotspot Fixing Using ILT.; 2011; p. 79731L. 17 March.

- Tritchkov, A.; Kobelkov, S.; Rodin, S.; Sakajiri, K.; Egorov, E.; Woo, S.-S. Use of ILT-Based Mask Optimization for Local Printability Enhancement. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Photomask and Next-Generation Lithography Mask Technology XXI; Kato, K., Ed.; July 28 2014; p. 92560X. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Z.; Shi, Z.; Yan, X.-L.; Luo, K.-S.; Pan, W.-W. Fast Level-Set-Based Inverse Lithography Algorithm for Process Robustness Improvement and Its Application. J Comput Sci Technol 2015, 30, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Platzgummer, E. MBMW-101: World’s 1st High-Throughput Multi-Beam Mask Writer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of SPIE,Proceedings of SPIE; Kasprowicz, B.S., Buck, P.D., Eds.; October 25 2016; p. 998505.

- Selinidis, K.; Hoppe, W.; Schmoeller, T.; Dam, T.; Hooker, K.; Xiao, G. Resist 3D Aware Mask Solution with ILT for Hotspot Repair. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Optical Microlithography XXX; Erdmann, A., Kye, J., Eds.; March 24 2017; p. 101470Q. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, L.; Ungar, J.; Bouaricha, A.; Sha, L.; Pomerantsev, M.; Niewczas, M.; Wang, K.; Su, B.; Pearman, R.; Fujimura, A. TrueMask® ILT MWCO: Full-Chip Curvilinear ILT in a Day and Full Mask Multi-Beam and VSB Writing in 12 Hrs for 193i. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XXXIII; Owa, S., Phillips, M.C., Eds.; SPIE, March 31 2020; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Baron, S.; Kachwala, N.; Kallingal, C.; Su, J.; Zhang, Q.; Shu, V.; Gao, J.-W.; Ser, J.-H.; Li, Z.; et al. Efficient Full-Chip SRAF Placement Using Machine Learning for Best Accuracy and Improved Consistency. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XXXI; Kye, J., Owa, S., Eds.; SPIE, March 20 2018; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, L. (Leo); Russell, E. V.; Baggenstoss, B.; Lu, Y.; Lee, M.; Digaum, J.P.; Yang, M.-C.; Pearman, R.; Ungar, P.J.; Sha, L.; et al. Enabling Faster VSB Writing of 193i Curvilinear ILT Masks That Improve Wafer Process Windows for Advanced Memory Applications. In Proceedings of the Photomask Technology 2020; Renwick, S.P., Preil, M.E., Eds.; SPIE, October 7 2020; p. 36.

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, H.; Jin, C.; Zhou, J.; Liu, J. Frequency-Decoupled Dual-Stage Inverse Lithography Optimization via Hierarchical Sampling and Morphological Enhancement. Micromachines (Basel) 2025, 16, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Gong, J.; Jin, C.; Zhou, J.; Liu, J. A Hierarchical Inverse Lithography Method Considering the Optimization and Manufacturability Limit by Gradient Descent. Micromachines (Basel) 2025, 16, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Inoue, H.; Yamashita, H.; Morita, H.; Hirose, S.; Ogasawara, M.; Yamada, H.; Hattori, K. Multi-Beam Mask Writer MBM-1000 and Its Application Field. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings,Photomask Japan 2016: XXIII Symposium on Photomask and Next-Generation Lithography Mask Technology; Yoshioka, N., Ed.; May 10 2016; p. 998405. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Lan, A.; Yang, R.; Chen, V.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Yang, A.; Liu, S.; Shi, X.; et al. Full-Chip Application of Machine Learning SRAFs on DRAM Case Using Auto Pattern Selection. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XXXII; Kye, J., Owa, S., Eds.; SPIE, October 10 2019; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, J.; Hwang, J.; Choi, J.; Oh, S.; Park, C.; Yang, H.; Dam, T.; Do, M.; Lee, D.C.; Xiao, G.; et al. Cost Effective Solution Using Inverse Lithography OPC for DRAM Random Contact Layer.; Capodieci, L., Cain, J.P., Eds.; 2017; p. 1014809. 4 April.

- Ma, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, S.; Arce, G.R.; Zhao, S. Nonlinear Compressive Inverse Lithography Aided by Low-Rank Regularization. Opt Express 2019, 27, 29992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.-Y.; Zhang, B.; Guo, E.; Pang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Dai, G. Pushing the Lithography Limit: Applying Inverse Lithography Technology (ILT) at the 65nm Generation.; Flagello, D.G., Ed.; 2006; p. 61541M. 10 March.

- Chen, J.-T.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Zhu, J.-X.; Duan, X.-M. Digital Inverse Patterning Solutions for Fabrication of High-Fidelity Microstructures in Spatial Light Modulator (SLM)-Based Projection Lithography. Opt Express 2024, 32, 6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Dai, G.; Cecil, T.; Dam, T.; Cui, Y.; Hu, P.; Chen, D.; Baik, K.-H.; Peng, D. Validation of Inverse Lithography Technology (ILT) and Its Adaptive SRAF at Advanced Technology Nodes. In Proceedings of the SPIE Proceedings, Optical Microlithography XXI; March 14 2008; p. 69240T. [Google Scholar]

- Ciou, W.; Hu, T.; Tsai, Y.-Y.; Hsuan, T.; Yang, E.; Yang, T.H.; Chen, K.C. SRAF Placement with Generative Adversarial Network. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XXXIV; Owa, S., Phillips, M.C., Eds.; SPIE, February 22 2021; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Celepcikay, F.T.; Liao, C.-C.; Huang, T.-Y.; Chen, S.-P.; Lin, C.N.; Zhu, A.; Lin, H.Y. Synthesizing ILT MB-SRAF Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the DTCO and Computational Patterning III; Lafferty, N. V., Grunes, H., Eds.; SPIE, April 10 2024; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Hou, J.; Zeggaoui, N.; Sun, Y.; Lei, J. A Study of ILT-Based Curvilinear SRAF with a Constant Width. In Proceedings of the Photomask Technology 2022; Kasprowicz, B.S., Liang, T., Eds.; SPIE, December 1 2022; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Liu, T.; Zhao, D.; Yin, Y.; Qin, G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, D. Monolithic Integration of Waveguide Amplifiers and Passive Polymer Photonic Devices Using Photolithography. Opt Express 2024, 32, 38285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danping Peng; Shang-Jung Wu; Jue-Chin Yu; Chia-Hua Chang; Kenneth Ho Curvilinear Mask: Bridging ILT to HVM. DTCO and Computational Patterning II 2023.

- Ma, X.; Han, C.; Li, Y.; Wu, B.; Song, Z.; Dong, L.; Arce, G.R. Hybrid Source Mask Optimization for Robust Immersion Lithography. Appl Opt 2013, 52, 4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yu, G.; Xiang, X.; Wang, X. GPU Accelerated Voxel-Driven Forward Projection for Iterative Reconstruction of Cone-Beam CT. Biomed Eng Online 2017, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yao, J.; Chen, J.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Q.; Huang, C.; Sun, M.; Guo, Y. A Cross-Scale Electrothermal Co-Simulation Approach for Power MOSFETs at Device–Package–Heatsink–Board Levels. Micromachines (Basel) 2024, 15, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Pillai, S.; Nguyen, T.; Meyer, M.; Baranwal, A.; Yu, H.; Niewczas, M.; Pearman, R.; Shendre, A.; Fujimura, A. Making Digital Twins Using the Deep Learning Kit (DLK). In Proceedings of the Photomask Technology 2019; Rankin, J.H., Preil, M.E., Eds.; SPIE, October 21 2019; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, L.; Niewczas, M.; Meyer, M.; Pearman, R.; Shendre, A.; Fujimura, A. How GPU-Accelerated Simulation Enables Applied Deep Learning for Masks and Wafers. In Proceedings of the Photomask Japan 2019: XXVI Symposium on Photomask and Next-Generation Lithography Mask Technology; Ando, A., Ed.; SPIE, June 27 2019; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).