Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Protocol and Registration

Eligibility Criteria

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Study Selection

Data Collection Process and Data Items

Risk of Bias Assessment

Outcome Measures

Geometry of the Network

Summary Measures and Statistical Analysis

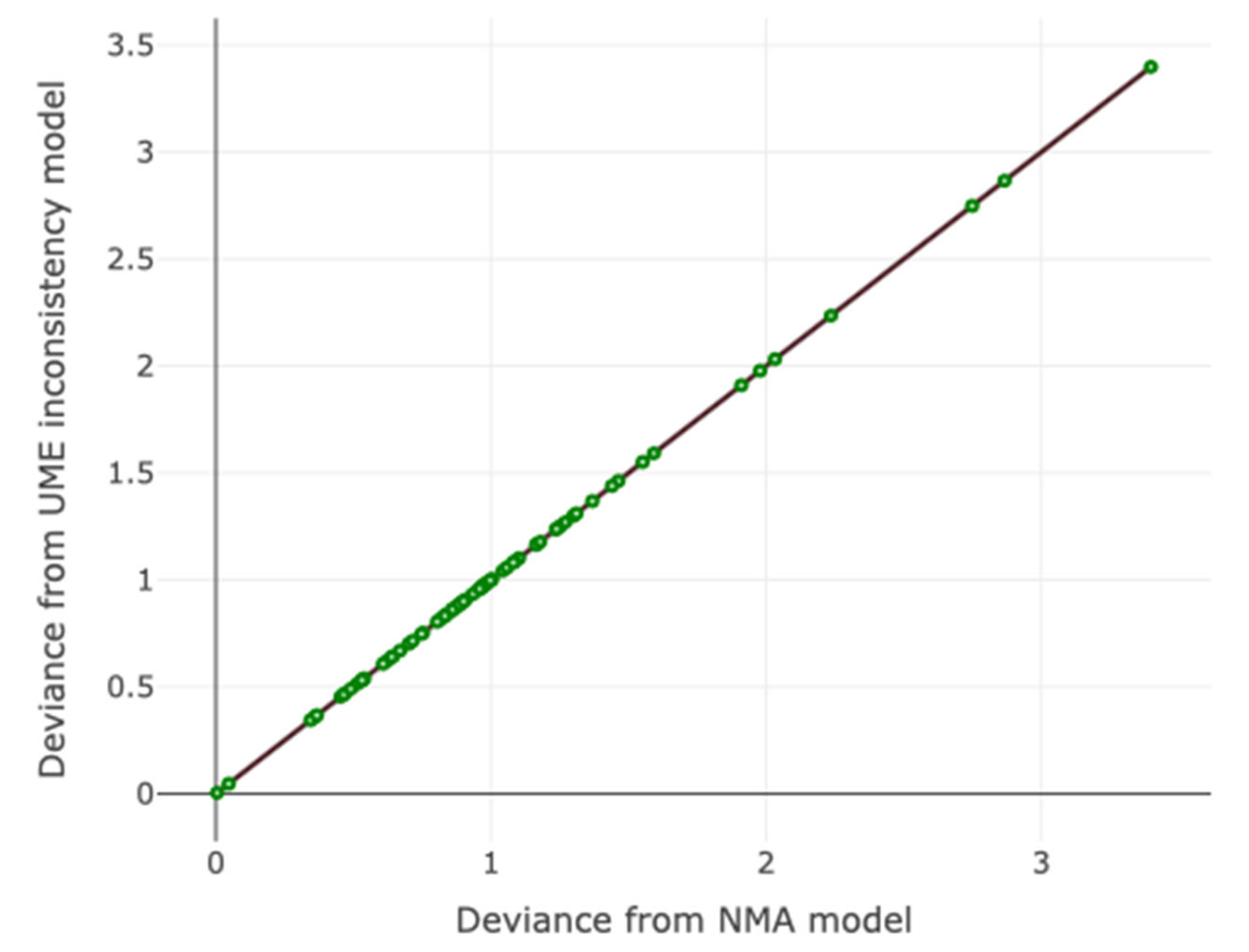

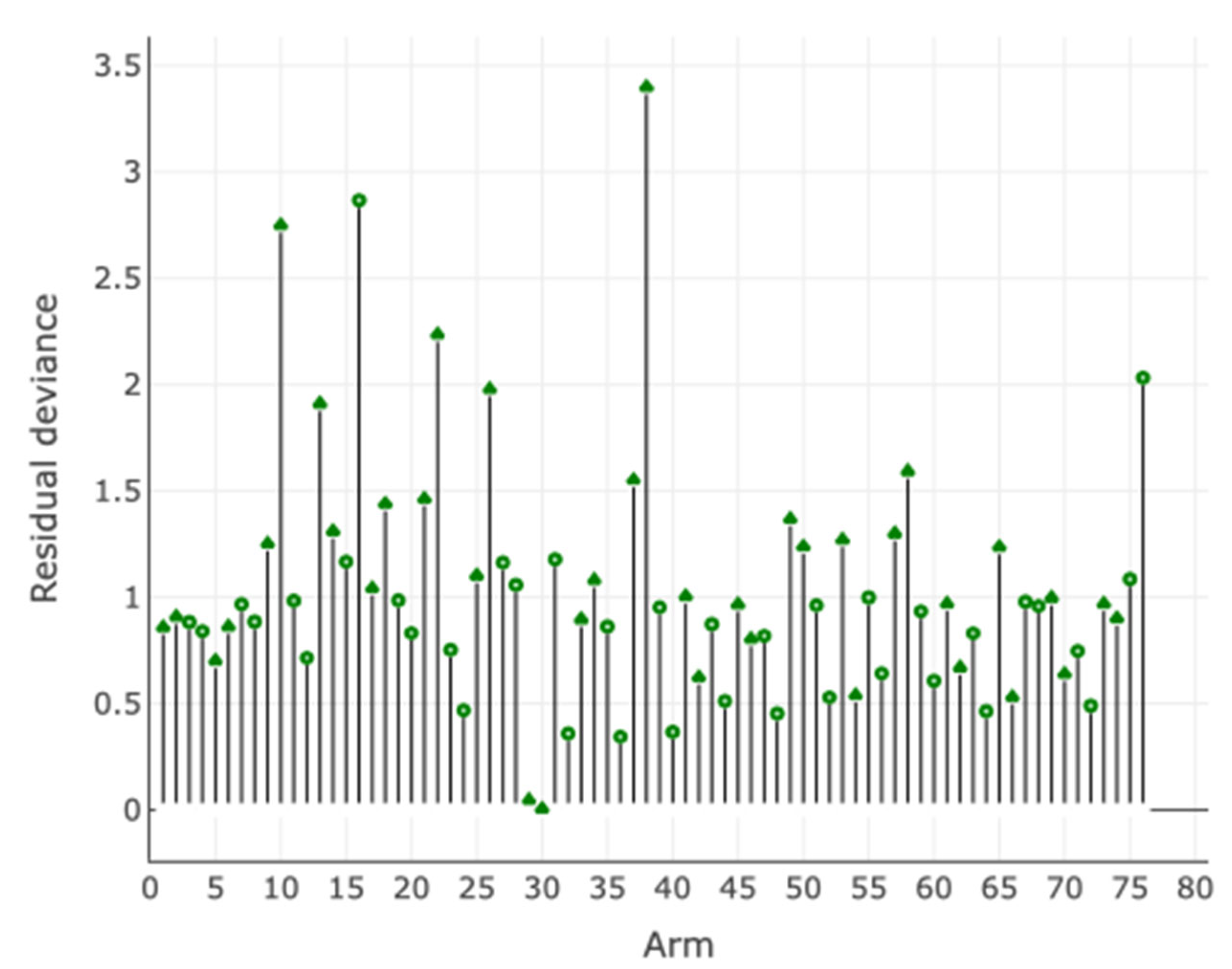

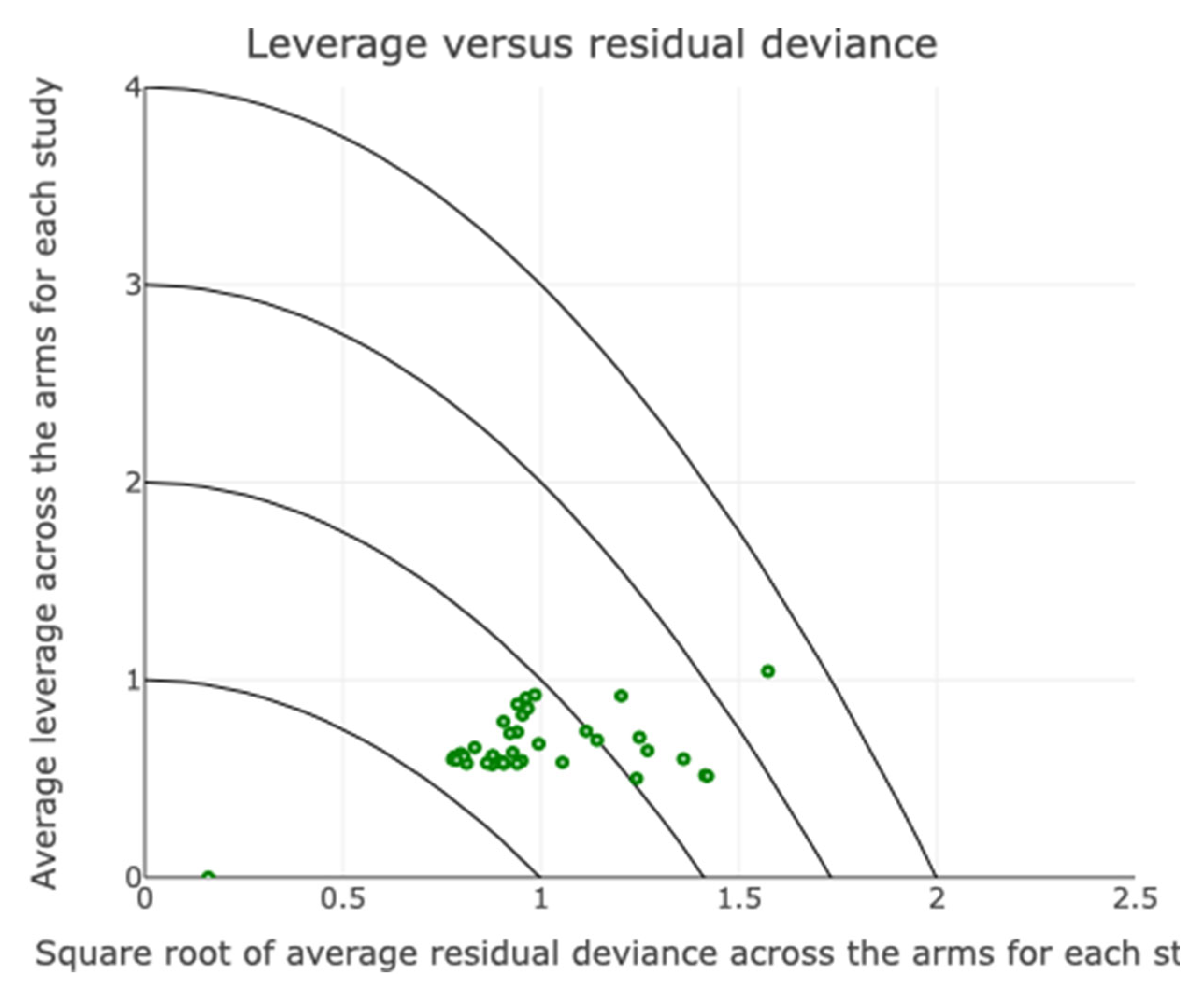

Assessment of Inconsistency and Small-Study Effects

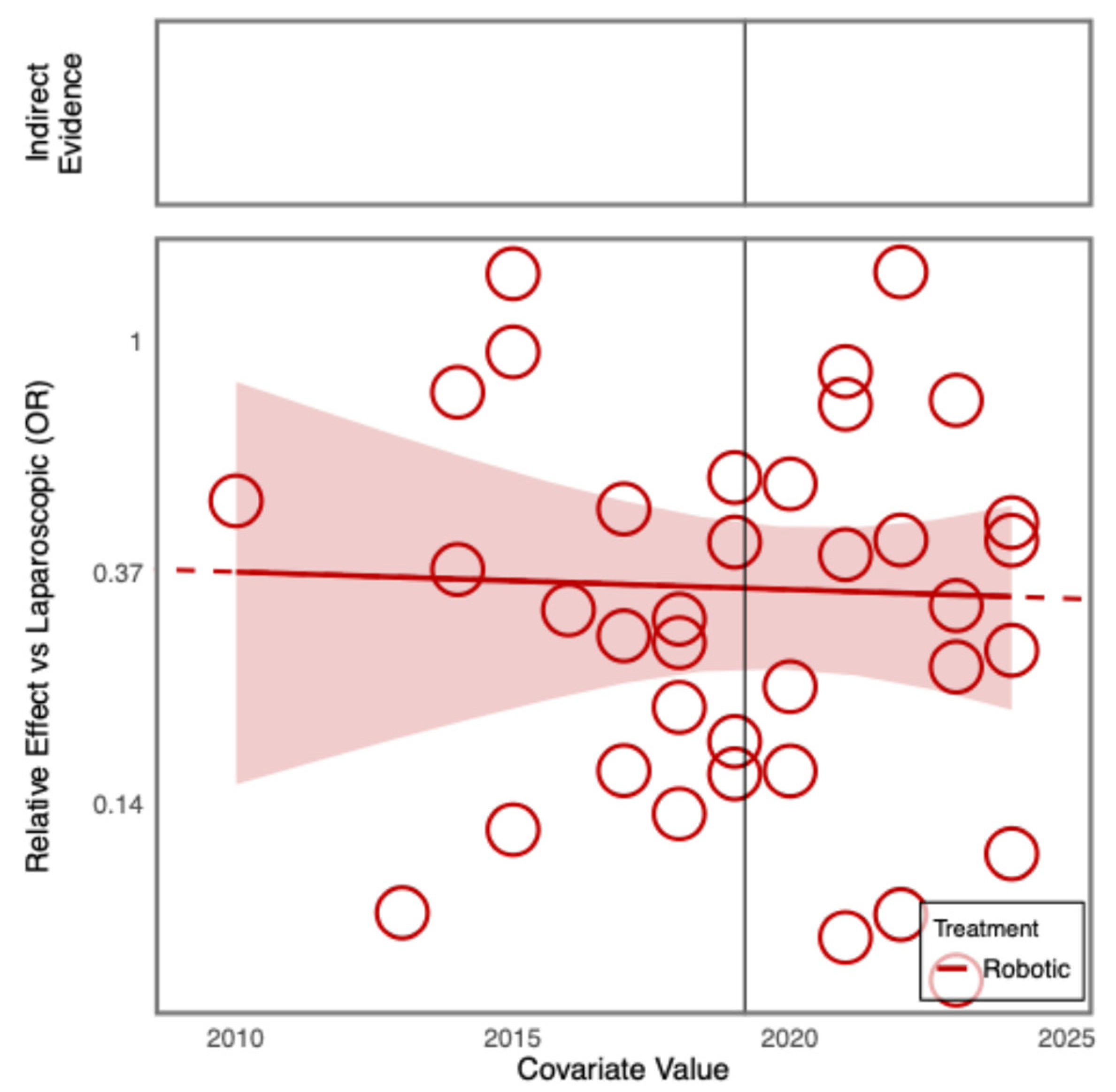

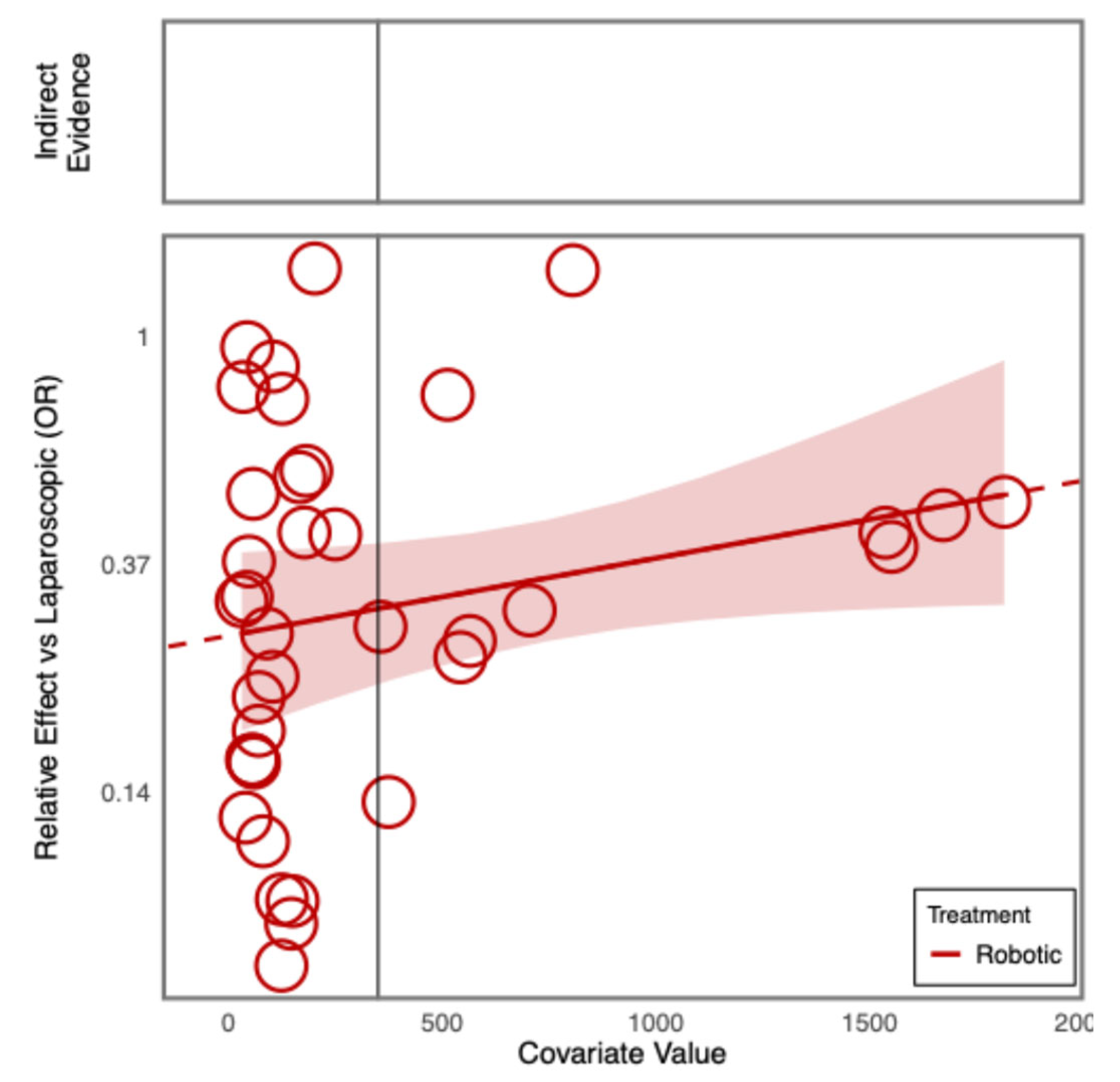

Additional Analyses

Software

Results

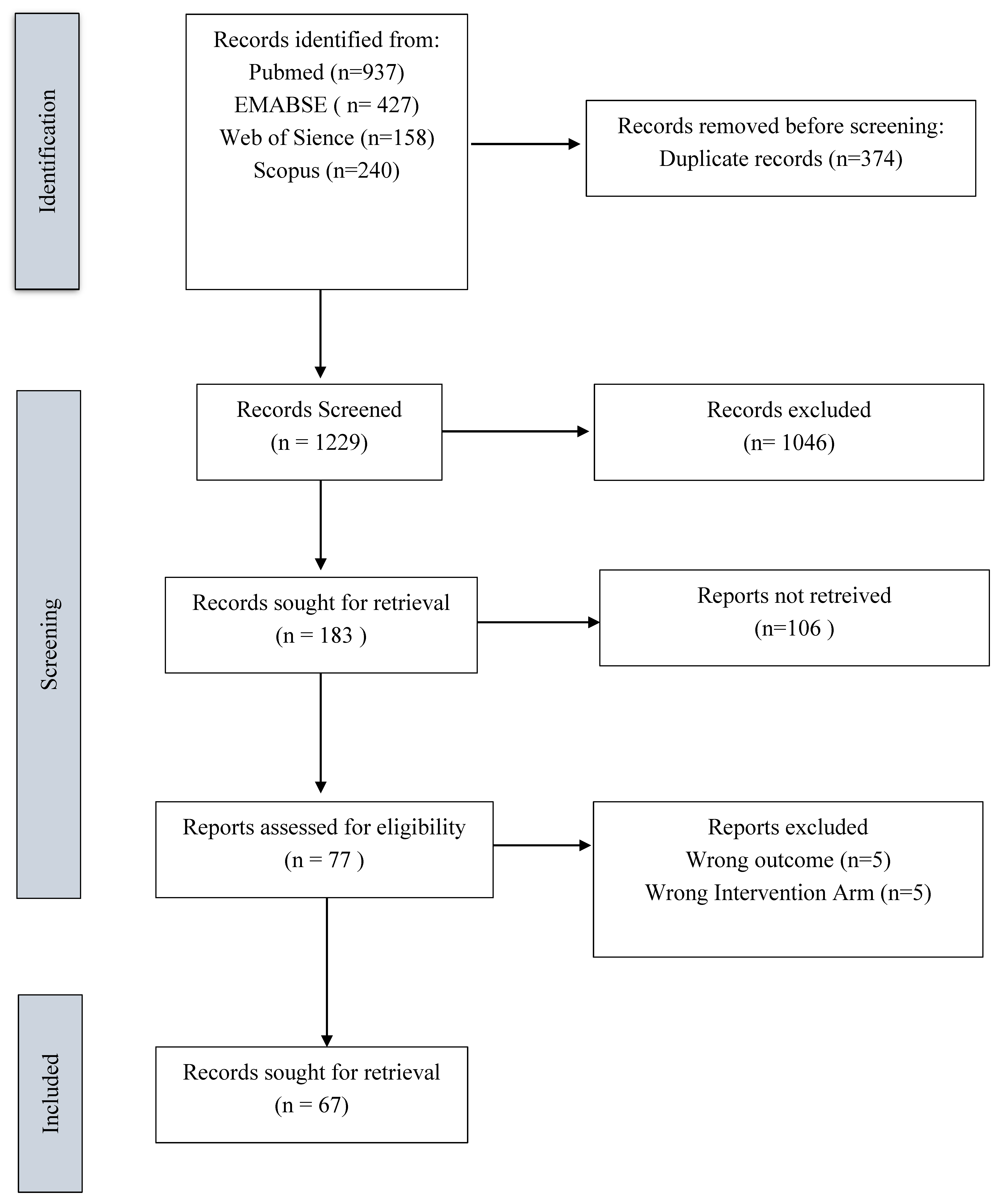

Search Results

Characteristics of the Included Studies

Outcomes NMA:

Age of Patients

Sex of Patients

ASA Status

Previous Cardiovascular Diseases

Operative Time

Conversion to Open

Intraoperative Blood Loss

Intraoperative Bleeding More than 500 ml

Number of Patients Receiving Transfusions

The Quantity of Blood Transfusion

Intensive Care Unit Length of Stay

Reintervention Rate

Hospital Length of Stay

Readmission Rate

In-Hospital Mortality

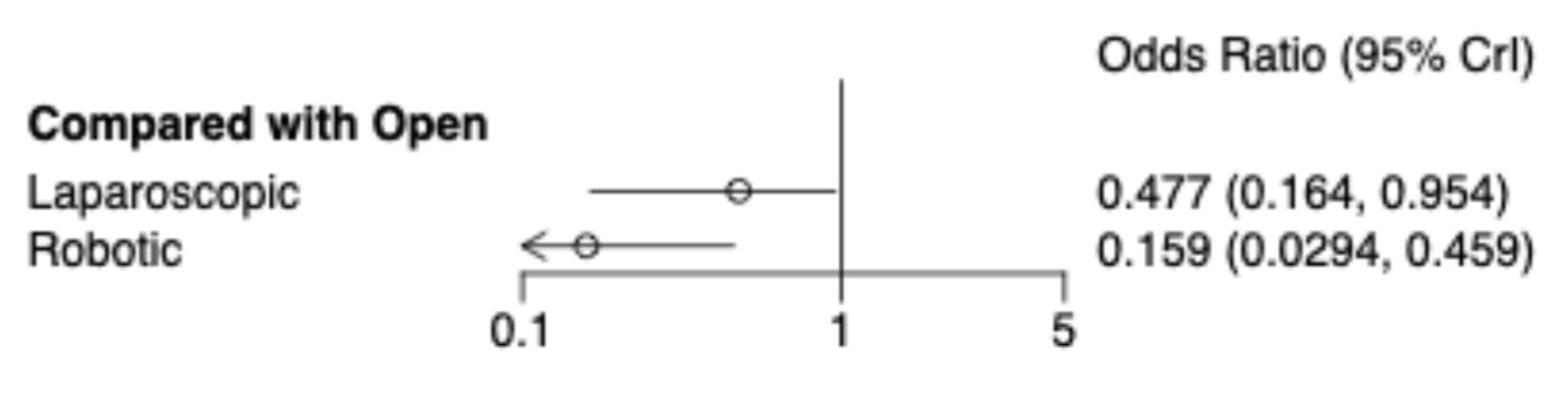

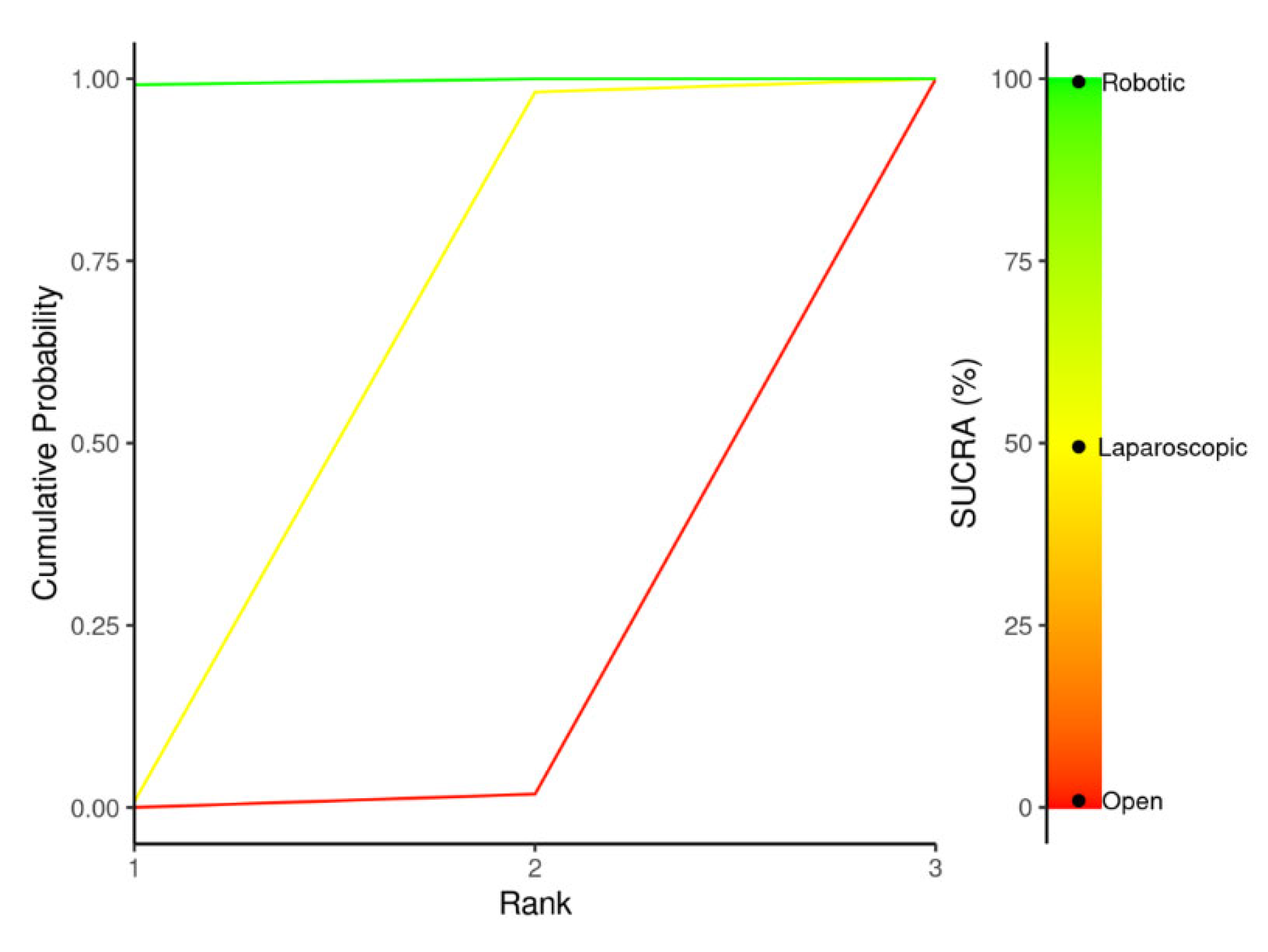

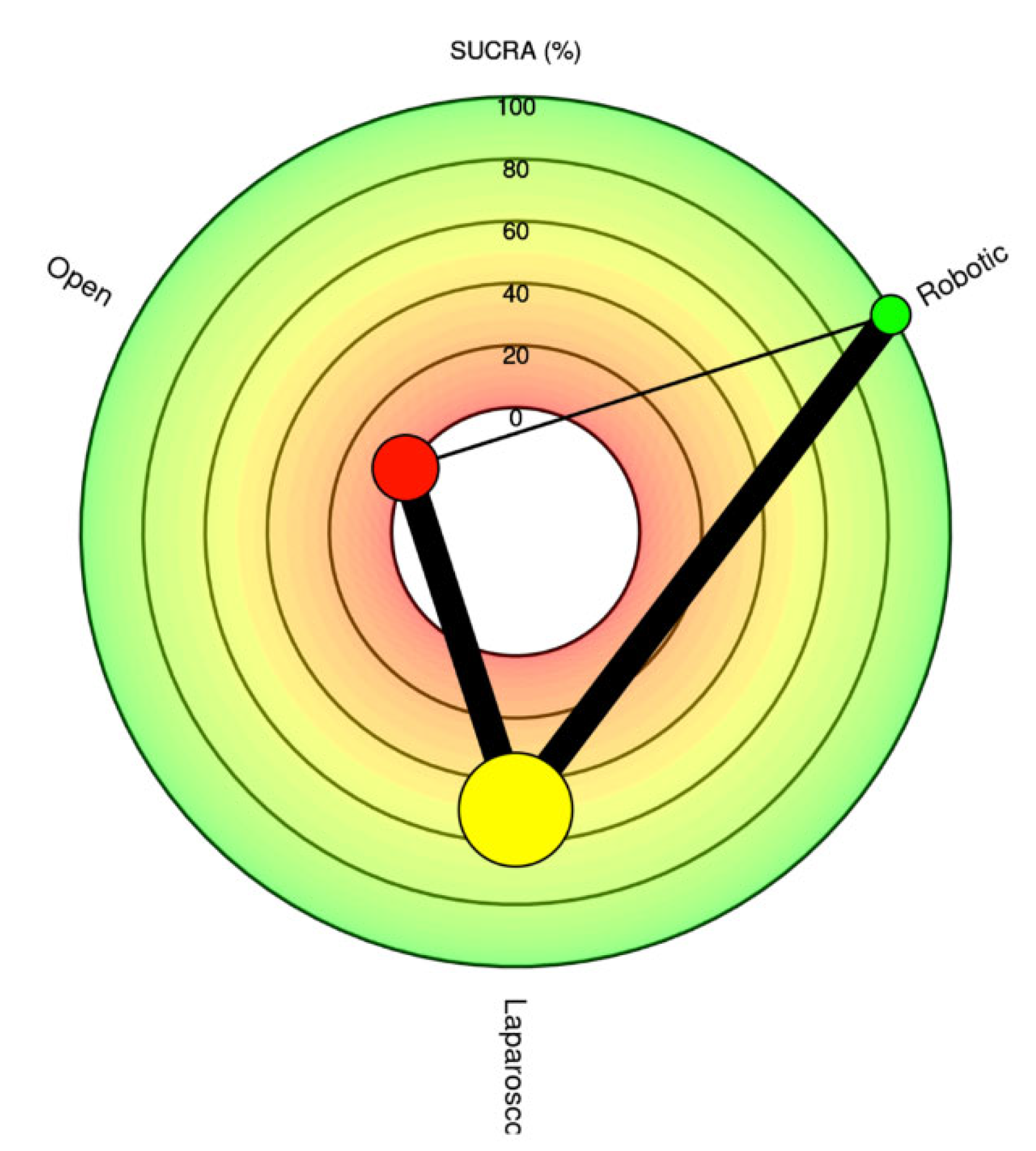

30. -Day Mortality

| Laparoscopic | Open | Robotic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic | Laparoscopic | 2.1 (1.05, 6.1) | 0.34 (0.1, 0.83) |

| Open | 0.48 (0.16, 0.95) | Open | 0.16 (0.03, 0.46) |

| Robotic | 2.97 (1.2, 9.78) | 6.29 (2.18, 34.05) | Robotic |

90. -Day Major Complications

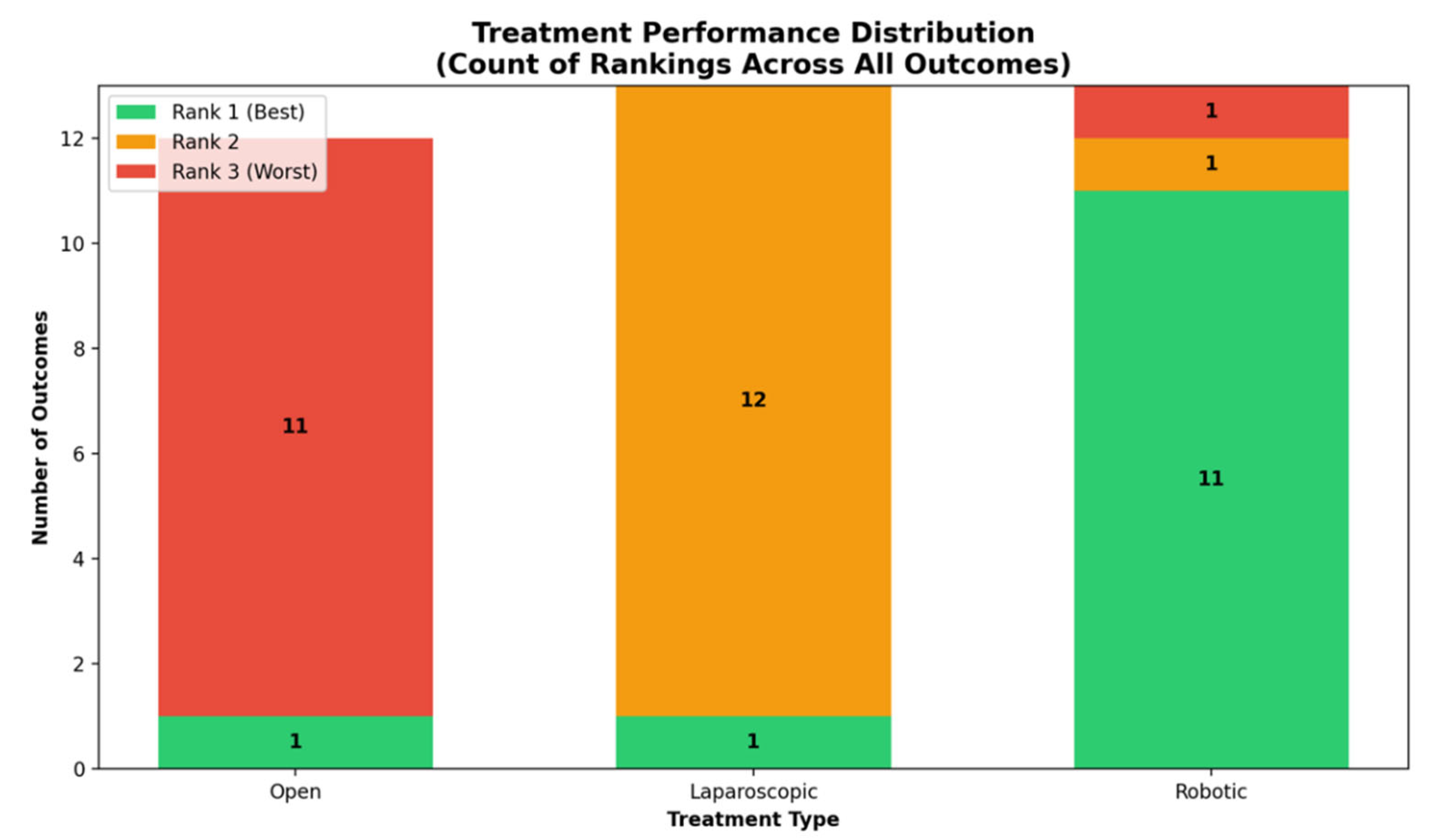

Summary

Discussions

Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest statements

Author Contributions (CRediT)

References

- Leiphrakpam, P.D.; Chowdhury, S.; Zhang, M.; Bajaj, V.; Dhir, M.; Are, C. Trends in the Global Incidence of Pancreatic Cancer and a Brief Review of Its Histologic and Molecular Subtypes. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2025, 56, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.P.; Hong, T.S.; Bardeesy, N. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, W.-T.; Shang, X.-S.; Ni, T.; Wu, W.-C.; Lou, W.-H.; Zeng, M.-S.; Rao, S.-X. Difference Analysis in Prevalence of Incidental Pancreatic Cystic Lesions between Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. BMC Med. Imaging 2019, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, E.; Bar-Yishay, I. Pancreatic Solid Incidentalomas. Endosc. Ultrasound 2017, 6, S99–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, A. Laparoscopic Surgery of the Pancreas. J. R. Coll. Surg. Edinb. 1994, 39, 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Giulianotti, P.C.; Coratti, A.; Angelini, M.; Sbrana, F.; Cecconi, S.; Balestracci, T.; Caravaglios, G. Robotics in General Surgery, Personal Experience in a Large Community Hospital. Arch. Surg. 2003, 138, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rooij, T.; van Hilst, J.; van Santvoort, H.; Boerma, D.; van den Boezem, P.; Daams, F.; van Dam, R.; Dejong, C.; van Duyn, E.; Dijkgraaf, M.; et al. Minimally Invasive versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy (LEOPARD): A Multicenter Patient-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial: A Multicenter Patient-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsson, B.; Larsson, A.L.; Hjalmarsson, C.; Gasslander, T.; Sandström, P. Comparison of the Duration of Hospital Stay after Laparoscopic or Open Distal Pancreatectomy: Randomized Controlled Trial: Duration of Hospital Stay after Distal Pancreatectomy. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.B.; Kim, S.C.; Park, J.B.; Kim, Y.H.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, M.-H.; Lee, S.-K.; Seo, D.-W.; Lee, S.S.; Park, D.H.; et al. Single-Center Experience of Laparoscopic Left Pancreatic Resection in 359 Consecutive Patients: Changing the Surgical Paradigm of Left Pancreatic Resection. Surg. Endosc. 2011, 25, 3364–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cabús, S.; Adam, J.-P.; Pittau, G.; Gelli, M.; Cunha, A.S. Laparoscopic Left Pancreatectomy: Early Results after 115 Consecutive Patients. Surg. Endosc. 2016, 30, 4480–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hilst, J.; de Rooij, T.; Klompmaker, S.; Rawashdeh, M.; Aleotti, F.; Al-Sarireh, B.; Alseidi, A.; Ateeb, Z.; Balzano, G.; Berrevoet, F.; et al. Minimally Invasive versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy for Ductal Adenocarcinoma (DIPLOMA): A Pan-European Propensity Score Matched Study. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korrel, M.; Jones, L.R.; van Hilst, J.; Balzano, G.; Björnsson, B.; Boggi, U.; Bratlie, S.O.; Busch, O.R.; Butturini, G.; Capretti, G.; et al. Minimally Invasive versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy for Resectable Pancreatic Cancer (DIPLOMA): An International Randomised Non-Inferiority Trial. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe 2023, 31, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbun, H.J.; Moekotte, A.L.; Vissers, F.L.; Kunzler, F.; Cipriani, F.; Alseidi, A.; D’Angelica, M.I.; Balduzzi, A.; Bassi, C.; Björnsson, B.; et al. The Miami International Evidence-Based Guidelines on Minimally Invasive Pancreas Resection. Ann. Surg. 2020, 271, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hilal, M.; van Ramshorst, T.M.E.; Boggi, U.; Dokmak, S.; Edwin, B.; Keck, T.; Khatkov, I.; Ahmad, J.; Al Saati, H.; Alseidi, A.; et al. The Brescia Internationally Validated European Guidelines on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery (EGUMIPS). Ann. Surg. 2023, 279, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijde, N.; Vissers, F.L.; Manzoni, A.; Zimmitti, G.; Balsells, J.; Berrevoet, F.; Bjornsson, B.; van den Boezem, P.; Boggi, U.; Bratlie, S.O.; et al. Use and Outcome of Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery in the European E-MIPS Registry. International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association 2023, 25, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevill, C.R.; Cooper, N.J.; Sutton, A.J. A Multifaceted Graphical Display, Including Treatment Ranking, Was Developed to Aid Interpretation of Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 157, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkenhoef, G.; Dias, S.; Ades, A.E.; Welton, N.J. Automated Generation of Node-Splitting Models for Assessment of Inconsistency in Network Meta-Analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2016, 7, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, S.; Ades, A.E.; Welton, N.J.; Jansen, J.P.; Sutton, A.J. Network Meta-Analysis for Decision-Making; John Wiley & Sons, 2018; ISBN 9781118647509.

- Donegan, S.; Dias, S.; Tudur-Smith, C.; Marinho, V.; Welton, N.J. Graphs of Study Contributions and Covariate Distributions for Network Meta-Regression. Res. Synth. Methods 2018, 9, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Papakonstantinou, T.; Salanti, G.; Efthimiou, O.; Schwarzer, G. Netmeta: An R Package for Network Meta-Analysis Using Frequentist Methods. J. Stat. Softw. 2023, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warn, D.E.; Thompson, S.G.; Spiegelhalter, D.J. Bayesian Random Effects Meta-Analysis of Trials with Binary Outcomes: Methods for the Absolute Risk Difference and Relative Risk Scales. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1601–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M.; Schmid, C. Bnma: Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis Using “JAGS.” CRAN: Contributed Packages 2019.

- Owen, R.K.; Bradbury, N.; Xin, Y.; Cooper, N.; Sutton, A. MetaInsight: An Interactive Web-Based Tool for Analyzing, Interrogating, and Visualizing Network Meta-Analyses Using R-Shiny and Netmeta. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolakopoulou, A.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Papakonstantinou, T.; Chaimani, A.; Del Giovane, C.; Egger, M.; Salanti, G. CINeMA: An Approach for Assessing Confidence in the Results of a Network Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Session Details Available online:. Available online: https://events.cochrane.org/colloquium-2023/session/1473545/nmastudio-a-fully-interactive-web-application-for-producing-and-visualizing-network-meta-analyses (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Rodriguez, M.; Memeo, R.; Leon, P.; Panaro, F.; Tzedakis, S.; Perotto, O.; Varatharajah, S.; de’Angelis, N.; Riva, P.; Mutter, D.; et al. Which Method of Distal Pancreatectomy Is Cost-Effective among Open, Laparoscopic, or Robotic Surgery? Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2018, 7, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Hilal, M.; Hamdan, M.; Di Fabio, F.; Pearce, N.W.; Johnson, C.D. Laparoscopic versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy: A Clinical and Cost-Effectiveness Study. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, S.; Butturini, G.; Boggi, U.; Pietrabissa, A.; Morelli, L.; Vistoli, F.; Damoli, I.; Peri, A.; Fiorillo, C.; Pugliese, L.; et al. Short-Term and Long-Term Outcomes after Robot-Assisted versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PNETs): A Multicenter Comparative Study. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2019, 404, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, M.Y.F.; Tsutsumi, K.; Nakamura, M.; Sato, N.; Takahata, S.; Ueda, J.; Shimizu, S.; Redwan, A.A.; Tanaka, M. Comparative Study of Laparoscopic and Open Distal Pancreatectomy. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2010, 20, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.S.; MBA; Bentrem, D. J.; Ujiki, M.B.; Ba, S.S.; LPN; Talamonti, M.S. A Prospective Single Institution Comparison of Peri-Operative Outcomes for Laparoscopic and Open Distal Pancreatectomy. Surgery 2009, 146, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benizri, E.I.; Germain, A.; Ayav, A.; Bernard, J.-L.; Zarnegar, R.; Benchimol, D.; Bresler, L.; Brunaud, L. Short-Term Perioperative Outcomes after Robot-Assisted and Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy. J. Robot. Surg. 2014, 8, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bodegraven, E.A.; van Ramshorst, T.M.E.; Bratlie, S.O.; Kokkola, A.; Sparrelid, E.; Björnsson, B.; Kleive, D.; Burgdorf, S.K.; Dokmak, S.; Koerkamp, B.G.; et al. Minimally Invasive Robot-Assisted and Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy in a Pan-European Registry a Retrospective Cohort Study. [CrossRef]

- Butturini, G.; Partelli, S.; Crippa, S.; Malleo, G.; Rossini, R.; Casetti, L.; Melotti, G.L.; Piccoli, M.; Pederzoli, P.; Bassi, C. Perioperative and Long-Term Results after Left Pancreatectomy: A Single-Institution, Non-Randomized, Comparative Study between Open and Laparoscopic Approach. Surg. Endosc. 2011, 25, 2871–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butturini, G.; Damoli, I.; Crepaz, L.; Malleo, G.; Marchegiani, G.; Daskalaki, D.; Esposito, A.; Cingarlini, S.; Salvia, R.; Bassi, C. A Prospective Non-Randomised Single-Center Study Comparing Laparoscopic and Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2015, 29, 3163–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadei, R.; Ricci, C.; D’Ambra, M.; Marrano, N.; Alagna, V.; Rega, D.; Monari, F.; Minni, F. Laparoscopic versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy in Pancreatic Tumours: A Case-Control Study. Updates Surg. 2010, 62, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.H.; Wehrle, C.; Woo, K.; Naples, R.; Stackhouse, K.A.; Dahdaleh, F.; Joyce, D.; Simon, R.; Augustin, T.; Walsh, R.M.; et al. Comparing Oncologic and Surgical Outcomes of Robotic and Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Propensity-Matched Analysis. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 5678–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhou, B.; Wang, T.; Hu, X.; Ye, Y.; Guo, W. Comparative Efficacy of Robot-Assisted and Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Single-Center Comparative Study. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7302222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.W.; van Ramshorst, T.M.E.; Lof, S.; Al-Sarireh, B.; Bjornsson, B.; Boggi, U.; Burdio, F.; Butturini, G.; Casadei, R.; Coratti, A.; et al. Robot-Assisted versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy in Patients with Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: An International, Retrospective, Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3023–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daouadi, M.; Zureikat, A.H.; Zenati, M.S.; Choudry, H.; Tsung, A.; Bartlett, D.L.; Hughes, S.J.; Lee, K.K.; Moser, A.J.; Zeh, H.J. Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Distal Pancreatectomy Is Superior to the Laparoscopic Technique. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pastena, M.; Esposito, A.; Paiella, S.; Surci, N.; Montagnini, G.; Marchegiani, G.; Malleo, G.; Secchettin, E.; Casetti, L.; Ricci, C.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness and Quality of Life Analysis of Laparoscopic and Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Propensity Score-Matched Study. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pastena, M.; Esposito, A.; Paiella, S.; Montagnini, G.; Zingaretti, C.C.; Ramera, M.; Azzolina, D.; Gregori, D.; Kauffmann, E.F.; Giardino, A.; et al. Nationwide Cost-Effectiveness and Quality of Life Analysis of Minimally Invasive Distal Pancreatectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 5881–5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Kawka, M.; Gall, T.M.H.; Wadsworth, C.; Habib, N.; Nicol, D.; Cunningham, D.; Jiao, L.R. Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy Yields Superior Outcomes Compared to Laparoscopic Technique: A Single Surgeon Experience of 123 Consecutive Cases. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNorcia, J.; Schrope, B.A.; Lee, M.K.; Reavey, P.L.; Rosen, S.J.; Lee, J.A.; Chabot, J.A.; Allendorf, J.D. Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy Offers Shorter Hospital Stays with Fewer Complications. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010, 14, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, H.; Ielpo, B.; Caruso, R.; Ferri, V.; Quijano, Y.; Diaz, E.; Fabra, I.; Oliva, C.; Olivares, S.; Vicente, E. Does Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy Surgery Offer Similar Results as Laparoscopic and Open Approach? A Comparative Study from a Single Medical Center: Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2014, 10, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, B.W.; Jang, J.-Y.; Lee, S.E.; Han, H.-S.; Yoon, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-W. Clinical Outcomes Compared between Laparoscopic and Open Distal Pancreatectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2008, 22, 1334–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finan, K.R.; Cannon, E.E.; Kim, E.J.; Wesley, M.M.; Arnoletti, P.J.; Heslin, M.J.; Christein, J.D. Laparoscopic and Open Distal Pancreatectomy: A Comparison of Outcomes. Am. Surg. 2009, 75, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.M.; Pitzul, K.; Bhojani, F.; Kaplan, M.; Moulton, C.-A.; Wei, A.C.; McGilvray, I.; Cleary, S.; Okrainec, A. Comparison of Outcomes and Costs between Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy and Open Resection at a Single Center. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, B.K.P.; Chan, C.Y.; Soh, H.-L.; Lee, S.Y.; Cheow, P.-C.; Chow, P.K.H.; Ooi, L.L.P.J.; Chung, A.Y.F. A Comparison between Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: Robotic vs Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2017, 13, e1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Ortiz, M.A.; Sánchez-Velazquez, P.; Burdío, F.; Gimeno, M.; Podda, M.; Pellino, G.; Toledano, M.; Nuñez, J.; Bellido, J.; Acosta-Mérida, M.A.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Robotic vs Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy. Results from the National Prospective Trial ROBOCOSTES. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 6270–6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Song, K.B.; Madkhali, A.A.; Hwang, K.; Yoo, D.; Lee, J.W.; Youn, W.Y.; Alshammary, S.; Park, Y.; Lee, W.; et al. Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy for Left-Sided Pancreatic Tumors: A Single Surgeon’s Experience of 228 Consecutive Cases. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 2465–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarufe, N.; Soto, P.; Ahumada, V.; Pacheco, S.; Salinas, J.; Galindo, J.; Bächler, J.-P.; Achurra, P.; Rebolledo, R.; Guerra, J.F.; et al. Laparoscopic versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy: Comparative Analysis of Clinical Outcomes at a Single Institution. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2018, 28, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, S.; Shao, Z.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, G.; He, T. Robot-Assisted Distal Pancreatectomy Improves Spleen Preservation Rate versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy for Benign and Low-Grade Malignant Lesions of the Pancreas. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 5166–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarajah, S.K.; Sutandi, N.; Sen, G.; Hammond, J.; Manas, D.M.; French, J.J.; White, S.A. Comparative Analysis of Open, Laparoscopic and Robotic Distal Pancreatic Resection: The United Kingdom’s First Single-Centre Experience. J. Minim. Access Surg. 2022, 18, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.M.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, W.J. Ten Years of Experience with Resection of Left-Sided Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Evolution and Initial Experience to a Laparoscopic Approach. Surg. Endosc. 2010, 24, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaled, Y.S.; Malde, D.J.; Packer, J.; De Liguori Carino, N.; Deshpande, R.; O’Reilly, D.A.; Sherlock, D.J.; Ammori, B.J. A Case-Matched Comparative Study of Laparoscopic versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2015, 25, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Park, K.T.; Hwang, J.W.; Shin, H.C.; Lee, S.S.; Seo, D.W.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, M.H.; Han, D.J. Comparative Analysis of Clinical Outcomes for Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatic Resection and Open Distal Pancreatic Resection at a Single Institution. Surg. Endosc. 2008, 22, 2261–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooby, D.A.; Gillespie, T.; Bentrem, D.; Nakeeb, A.; Schmidt, M.C.; Merchant, N.B.; Parikh, A.A.; Martin, R.C.G., 2nd; Scoggins, C.R.; Ahmad, S.; et al. Left-Sided Pancreatectomy: A Multicenter Comparison of Laparoscopic and Open Approaches. Ann. Surg. 2008, 248, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.C.H.; Tang, C.N. Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy versus Conventional Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Comparative Study for Short-Term Outcomes. Front. Med. 2015, 9, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.-F.; Shyr, Y.-M.; Shyr, B.-S.; Chen, S.-C.; Wang, S.-E.; Shyr, B.-U. Minimally Invasive Distal Pancreatectomy: Laparoscopic versus Robotic Approach-A Cohort Study. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ser Yee Lee MBBS MSc MMed FRCS(Ed); Allen MD FACS, P. ; Sadot, E.; D’Angelica MD FACS, M.; DeMatteo MD FACS, R.; Facs, Y.F.M.D.; Jarnagin MD FACS, W.; Facs, T.P.K. Distal Pancreatectomy: A Single Institution’s Experience in Open, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Approaches. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2015, 220, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Q.; Kabir, T.; Koh, Y.-X.; Teo, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kam, J.-H.; Cheow, P.-C.; Jeyaraj, P.R.; Chow, P.K.H.; Ooi, L.L.; et al. A Single Institution Experience with Robotic and Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomies. Ann. Hepatobiliary. Pancreat. Surg. 2020, 24, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ielpo, B.; Duran, H.; Diaz, E.; Fabra, I.; Caruso, R.; Malavé, L.; Ferri, V.; Nuñez, J.; Ruiz-Ocaña, A.; Jorge, E.; et al. Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Comparative Study of Clinical Outcomes and Costs Analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 48, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongelli, P.; Belli, A.; Russo, G.; Cioffi, L.; D’Agostino, A.; Fantini, C.; Belli, G. Laparoscopic and Open Surgical Treatment of Left-Sided Pancreatic Lesions: Clinical Outcomes and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 1830–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.-M.; Tan, X.-L.; Gao, Y.-X.; Zhao, G.-D. Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Propensity Score-Matched Study. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 116, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lof, S.; van der Heijde, N.; Abuawwad, M.; Al-Sarireh, B.; Boggi, U.; Butturini, G.; Capretti, G.; Coratti, A.; Casadei, R.; D’Hondt, M.; et al. Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: Multicentre Analysis. [CrossRef]

- Lyman, W.B.; Passeri, M.; Sastry, A.; Cochran, A.; Iannitti, D.A.; Vrochides, D.; Baker, E.H.; Martinie, J.B. Robotic-Assisted versus Laparoscopic Left Pancreatectomy at a High-Volume, Minimally Invasive Center. Surg. Endosc. 2019, 33, 2991–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magge, D.R.; Zenati, M.S.; Hamad, A.; Rieser, C.; Zureikat, A.H.; Zeh, H.J.; Hogg, M.E. Comprehensive Comparative Analysis of Cost-Effectiveness and Perioperative Outcomes between Open, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2018, 20, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.V.; Mirabella, A.; Gomez Ruiz, M.; Komorowski, A.L. Robotic-Assisted versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: The Results of a Case-Matched Analysis from a Tertiary Care Center. Dig. Surg. 2020, 37, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.S.; Doumane, G.; Mura, T.; Nocca, D.; Fabre, J.-M. Laparoscopic versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy: A Single-Institution Case-Control Study. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, L.; Guadagni, S.; Palmeri, M.; Franco, G.; Caprili, G.; D’isidoro, C.; Bastiani, L.; Candio, G.; Pietrabissa, A.; Mosca, F. A Case-Control Comparison of Surgical and Functional Outcomes of Robotic-Assisted Spleen-Preserving Left Side Pancreatectomy versus Pure Laparoscopy. Journal of the Pancreas 2016, 17, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, N.; Mintziras, I.; Wiese, D.; Albers, M.B.; Maurer, E.; Bartsch, D.K. A Retrospective Comparison of Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Resection and Enucleation for Potentially Benign Pancreatic Neoplasms. Surg. Today 2020, 50, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Uchida, E.; Aimoto, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Yoshida, H.; Tajiri, T. Clinical Outcome of Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy. J. Hepatobiliary. Pancreat. Surg. 2009, 16, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, F.; Distler, M.; Limen, E.F.; Wise, P.A.; Kowalewski, K.-F.; Tritarelli, P.M.; Perez, D.; Izbicki, J.R.; Kersebaum, J.-N.; Egberts, J.-H.; et al. Initial Learning Curves of Laparoscopic and Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy Compared with Open Distal Pancreatectomy: Multicentre Analysis. Br. J. Surg. 2023, 110, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Zhiming, Z.; Xianglong, T.; Yuanxing, G.; Yong, X.; Rong, L.; Yee, L.W. Short- and Mid-Term Outcomes of Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatosplenectomy for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Retrospective Propensity Score-Matched Study. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 55, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, M.; Nota, C.L.M.A.; Melstrom, L.G.; Warner, S.G.; Woo, Y.; Singh, G.; Fong, Y. Oncologic Outcomes after Robot-Assisted versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: Analysis of the National Cancer Database: RAOOFet Al. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 118, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.; Kwon, J.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S.Y.; Park, Y.; Lee, W.; Song, K.B.; Hwang, D.W.; Kim, S.C. Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int 2023, 22, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souche, R.; Herrero, A.; Bourel, G.; Chauvat, J.; Pirlet, I.; Guillon, F.; Nocca, D.; Borie, F.; Mercier, G.; Fabre, J.-M. Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A French Prospective Single-Center Experience and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 3562–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauffer, J.A.; Rosales-Velderrain, A.; Goldberg, R.F.; Bowers, S.P.; Asbun, H.J. Comparison of Open with Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Single Institution’s Transition over a 7-Year Period. HPB (Oxford) 2013, 15, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velanovich, V. Case-Control Comparison of Laparoscopic versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2006, 10, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, E.; Núñez-Alfonsel, J.; Ielpo, B.; Ferri, V.; Caruso, R.; Duran, H.; Diaz, E.; Malave, L.; Fabra, I.; Pinna, E.; et al. A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2020, 16, e2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijan, S.S.; Ahmed, K.A.; Harmsen, W.S.; Que, F.G.; Reid-Lombardo, K.M.; Nagorney, D.M.; Donohue, J.H.; Farnell, M.B.; Kendrick, M.L. Laparoscopic vs Open Distal Pancreatectomy: A Single-Institution Comparative Study. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.A.; Canal, D.F.; Wiebke, E.A.; Dumas, R.P.; Beane, J.D.; Aguilar-Saavedra, J.R.; Ball, C.G.; House, M.G.; Zyromski, N.J.; Nakeeb, A.; et al. Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy: Cost Effective? Surgery 2010, 148, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellner, U.F.; Lapshyn, H.; Bartsch, D.K.; Mintziras, I.; Hopt, U.T.; Wittel, U.; Krämling, H.-J.; Preissinger-Heinzel, H.; Anthuber, M.; Geissler, B.; et al. Laparoscopic versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy-a Propensity Score-Matched Analysis from the German StuDoQ|Pancreas Registry. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2017, 32, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Jin, J.; Huo, Z.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, X.; Peng, C.; Shen, B. Robotic-Assisted versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy for Benign and Low-Grade Malignant Pancreatic Tumors: A Propensity Score-Matched Study. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xourafas, D.; Ashley, S.W.; Clancy, T.E. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes between Open, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy: An Analysis of 1815 Patients from the ACS-NSQIP Procedure-Targeted Pancreatectomy Database. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017, 21, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.-F.; Kuang, T.-T.; Ji, D.-Y.; Xu, X.-W.; Wang, D.-S.; Zhang, R.-C.; Jin, W.-W.; Mou, Y.-P.; Lou, W.-H. Laparoscopic versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy for Benign or Premalignant Pancreatic Neoplasms: A Two-Center Comparative Study. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2015, 16, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jin, J.; Chen, S.; Gu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, K.; Zhan, Q.; Cheng, D.; Chen, H.; Deng, X.; et al. Minimally Invasive Distal Pancreatectomy for PNETs: Laparoscopic or Robotic Approach? Oncotarget 2017, 8, 33872–33883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Jiang, J.; Ye, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhai, Z.; Bai, X.; Liang, T. A Comparison of Robotic versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Single Surgeon’s Robotic Experience in a High-Volume Center. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 9186–9193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.S.; Kooby, D.A.; Schmidt, C.M.; Nakeeb, A.; Bentrem, D.J.; Merchant, N.B.; Parikh, A.A.; Martin, R.C.G., 2nd; Scoggins, C.R.; Ahmad, S.A.; et al. Laparoscopic versus Open Left Pancreatectomy: Can Preoperative Factors Indicate the Safer Technique? Ann. Surg. 2011, 253, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, A.; Nassour, I.; Zureikat, A.; Paniccia, A. Perioperative and Oncologic Outcomes of Open, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Updates Surg. 2021, 73, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ramshorst, T.M.E.; van Bodegraven, E.A.; Zampedri, P.; Kasai, M.; Besselink, M.G.; Abu Hilal, M. Robot-Assisted versus Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Including Patient Subgroups. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 4131–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boggi, U.; Donisi, G.; Napoli, N.; Partelli, S.; Esposito, A.; Ferrari, G.; Butturini, G.; Morelli, L.; Abu Hilal, M.; Viola, M.; et al. Prospective Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Resections from the IGOMIPS Registry: A Snapshot of Daily Practice in Italy on 1191 between 2019 and 2022. Updates Surg. 2023, 75, 1439–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.; Lewis, A.; Thornblade, L.W.; Maker, A.V.; Fong, Y.; Melstrom, L.G. Robotic Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Evolving Trends in Patient Selection and Practice Patterns across a Decade. HPB (Oxford) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidis, P.; Roberts, K.J.; Sutcliffe, R.P. Comparison of Robotic vs Laparoscopic vs Open Distal Pancreatectomy. A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2019, 21, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zureikat, A.H.; Moser, A.J.; Boone, B.A.; Bartlett, D.L.; Zenati, M.; Zeh, H.J. 250 Robotic Pancreatic Resections. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakir, M.; Boone, B.A.; Polanco, P.M.; Zenati, M.S.; Hogg, M.E.; Tsung, A.; Choudry, H.A.; Moser, A.J.; Bartlett, D.L.; Zeh, H.J.; et al. The Learning Curve for Robotic Distal Pancreatectomy: An Analysis of Outcomes of the First 100 Consecutive Cases at a High-Volume Pancreatic Centre. HPB (Oxford) 2015, 17, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (year) | Total NOS (0-9) |

|---|---|

| Rodriguez (2018) | 9 |

| Abu Hilal (2012) | 9 |

| Alfieri (2019) | 9 |

| Aly (2010) | 7 |

| Beker (2009) | 9 |

| Benizri (2014) | 8 |

| van Bodegraven (2024) | 9 |

| Butturini (2011) | 8 |

| Butturini (2015) | 8 |

| Casadei (2010) | 9 |

| Chang (2024) | 9 |

| Chen (2022) | 9 |

| Chen (2023) | 9 |

| Daouadi (2013) | 8 |

| De Pastena (2021) | 8 |

| De Pastena (2024) | 9 |

| Ding (2023) | 7 |

| DiNorcia (2010) | 6 |

| Duran (2014) | 7 |

| Eom (2008) | 7 |

| Finan (2009) | 7 |

| Fox (2012) | 8 |

| Goh (2016) | 7 |

| Guerrero-Ortiz (2024) | 7 |

| Hong (2020) | 8 |

| Jarufe (2018) | 9 |

| Jiang (2020) | 9 |

| Kamarajah (2022) | 8 |

| Kang (2010) | 8 |

| Khaled (2015) | 9 |

| Kim(2008) | 6 |

| Kooby (2008) | 8 |

| Lai (2015) | 9 |

| Lai (2022) | 8 |

| Lee (2015) | 9 |

| Lee (2020) | 7 |

| Lelpo (2017) | 7 |

| Limongelli (2012) | 8 |

| Liu (2017) | 9 |

| Lof (2021) | 9 |

| Lyman (2019) | 9 |

| Magge (2018) | 9 |

| Marino (2019) | 9 |

| Mehta (2012) | 8 |

| Morelli (2016) | 9 |

| Najafi (2020) | 9 |

| Nakamura (2009) | 7 |

| Nakamura (2015) | 9 |

| Nickel (2023) | 9 |

| Qu (2018) | 9 |

| Raoof (2018) | 9 |

| Shin (2023) | 9 |

| Souche (2018) | 7 |

| Stauffer (2013) | 9 |

| Velanovich (2006) | 8 |

| Vicente (2019) | 7 |

| Vijan (2010) | 9 |

| Waters (2010) | 7 |

| Wellner (2017) | 9 |

| Weng (2021) | 9 |

| Xourafas (2017) | 9 |

| Yan (2015) | 7 |

| Zhang (2017) | 7 |

| Zhang (2022) | 9 |

| Cho (2011) | 9 |

| Chopra (2021) | 9 |

| Study (year) | Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool |

| Björnsson (2020) | 4/5 |

| Study | Country | Study period | Study type (RCT/ Retrospective/ Retrospective + prospectively held data base/ Prospective observational/ Prospective observational cu propensity match) | No. Included patients | Comparaison (RDP VS LDP VS ODP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodriguez_2018[27] | France | 2012-2015 | Retrospective with prospectively maintained database | 89 | RDP VS LDP VS ODP |

| Abu Hilal_2012[28] | UK | 2005-2011 | Retrospective from a prospectively held database | 51 | LDP vs ODP |

| Alfieri_2019[29] | Italy | 2008-2016 | Retrospective | 181 | LDP vs RDP |

| Aly_2010[30] | Japan | 1998-2009 | Retrospective | 75 | LDP vs ODP |

| Beker_2009[31] | USA | 2003-2008 | Prospective Non-randomized | 112 | LDP vs ODP |

| Benizri_2014[32] | France | 2004-2011 | Retrospective with prospectively maintained database | 34 | LDP vs RDP |

| Björnsson_2020[32] | Sweden | 2015-2019 | RCT | 58 | LDP vs ODP |

| van Bodegraven_2024[33] | Pan-European | 2019-2021 | Retrospective with prospectively maintained database | 1672 | RDP vs LDP |

| Butturini_2011[34] | Italy | 1999-2006 | Retrospective non-randomized study | 116 | LDP vs ODP |

| Butturini_2015[35] | Italy | 2011-2014 | Prospective Non-randomized | 43 | LDP vs RDP |

| Casadei_2010[36] | Italy | 2000-2010 | Retrospective case-control study | 44 | LDP vs ODP |

| Chang_2024[37] | USA | 2010-2020 | Retrospective propensity score matching | 1537 | LDP vs RDP |

| Chen_2022[38] | China | 2013-2019 | Retrospective case study | 149 | LDP vs RDP |

| Chen_2023[39] | Internation | 2010-2019 | Retrospective | 542 | LDP vs RDP |

| Daouadi_2013[40] | USA | 2004-2011 | Retrospective | 124 | LDP vs RDP |

| De Pastena_2021[41] | Italy | 2011-2017 | Retrospective propensity score matching | 103 | LDP vs RDP |

| De Pastena_2024[42] | Italy | 2010-2020 | Retrospective | 564 | LDP vs RDP |

| Ding_2023[43] | UK | 2008-2023 | Retrospective with prospectively maintained database | 123 | LDP vs RDP |

| DiNorcia_2010[44] | USA | 1991-2009 | Retrospective with prospectively maintained database | 387 | LDP vs ODP |

| Duran_2014[45] | Spain | 2008-2013 | Retrospective | 47 | LDP vs ODP vs RDP |

| Eom_2008[46] | Korea | 1995-2006 | Retrospective case-control study | 93 | LDP vs ODP |

| Finan_2009[47] | USA | 2002-2007 | Retrospective | 148 | LDP vs ODP |

| Fox_2012[48] | Canada | 2004-2010 | Retrospective | 118 | LDP vs ODP |

| Goh_2016[49] | Singapore | 2006-2015 | Retrospective with prospectively maintained database | 39 | LDP vs RDP |

| Guerrero-Ortiz_2024[50] | Spain | 2022 | Prospective , multicentral national observational study | 80 | LDP vs RDP |

| Hong_2020[51] | South Korea | 2015-2017 | Retrospective | 228 | LDP vs RDP |

| Jarufe_2018[52] | Chile | 2001-2015 | Retrospective | 93 | LDP vs ODP |

| Jiang_2020[53] | China | 2011-2018 | Retrospective | 166 | LDP vs RDP |

| Kamarajah_2022[54] | UK | 2007-2018 | Retrospective | 125 | LDP vs RDP vs ODP |

| Kang_2010[55] | Korea | 1999-2008 | Retrospective | 32 | LDP vs ODP |

| Khaled_2015[56] | UK | 2002-2011 | Retrospective case matched | 44 | LDP vs ODP |

| Kim_2008[57] | South Korea | - | Retrospective | 128 | LDP vs ODP |

| Kooby_2008[58] | USA | 2002-2006 | Retrospective multicentral cohort from a prospectively held database | 667 | LDP vs ODP |

| Lai_2015[59] | China | 1999-2015 | Retrospective from a prospectively held database | 35 | LDP vs RDP |

| Lai_2022[60] | Taiwan | 2011-2020 | Retrospective using a prospectively maintained database | 177 | LDP vs RDP |

| Lee_2015[61] | USA | 200-2013 | Retrospective | 805 | LDP vs RDP vs ODP |

| Lee_2020[62] | Singapore | 2006-2019 | Retrospective from a prospectively held database | 102 | LDP vs RDP |

| Lelpo_2017[63] | Spain | 2011-2017 | Retrospective | 54 | LDP vs RDP |

| Limongelli_2012[64] | Italy | 2000-2010 | Retrospective from a prospectively held database | 45 | LDP vs ODP |

| Liu_2017[65] | China | 2011-2015 | Retrospective propensity score matched study | 355 | LDP vs RDP |

| Lof_2021[66] | Europe | 2011-2019 | Retrospective, Propensity scire matching | 1551 | LDP vs RDP |

| Lyman_2019[67] | USA | 2008-2017 | Retrospective from a prospectively held database | 249 | LDP vs RDP |

| Magge_2018[68] | USA | 2010-2016 | Retrospective from a prospectively held database | 374 | LDP vs ODP vs RDP |

| Marino_2019[69] | Italy | 2014-2017 | Retrospective case matched | 70 | LDP vs RDP |

| Mehta_2012[70] | France | 1998-2009 | Retrospective case-control study | 60 | LDP vs ODP |

| Morelli_2016[71] | Italy | 2010-2014 | Retrospective case matched | 30 | LDP vs RDP |

| Najafi_2020[72] | Germany | 2008-2018 | Retrospective | 56 | LDP vs RDP |

| Nakamura_2009[73] | Japan | 2000-2007 | Retrospective | 36 | LDP vs ODP |

| Nakamura_2015[73] | Japan | 2006-2013 | Retrospective Propensity score matching | 2010 | LDP vs ODP |

| Nickel_2023[74] | Germany | 2007-2020 | Retrospective case matched | 512 | LDP vs RDP vs ODP |

| Qu_2018[75] | China | 2011-2015 | Retrospective propensity score matching | 70 | LDP vs RDP |

| Raoof_2018[76] | USA | 2010-2013 | Retrospective | 704 | LDP vs RDP |

| Shin_2023[77] | Korea | 2015-2020 | Retrospective propensity score matched study | 42 | LDP vs RDP |

| Souche_2018[78] | France | 2011-2016 | Prospective Non-randomized | 38 | LDP vs RDP |

| Stauffer_2013[79] | USA | 2005-2011 | Retrospective | 172 | LDP vs ODP |

| Velanovich_2006[80] | USA | 1996-2005 | Retrospective case matched | 30 | LDP vs ODP |

| Vicente_2019[81] | Spain | 2014-2018 | Prospective Non-randomized | 59 | LDP vs RDP |

| Vijan_2010[82] | USA | 2004-2009 | Retrospective case matched | 200 | LDP vs ODP |

| Waters_2010[83] | USA | 2008-2009 | Retrospective from a prospectively held database | 57 | LDP vs ODP vs RDP |

| Wellner_2017[84] | Germany | 2013-2016 | Retrospective propensity score matched study | 198 | LDP vs ODP |

| Weng_2021[85] | China | 2012-2019 | Retrospective case-control study | 679 | RDP vs ODP |

| Xourafas_2017[86] | USA | 2014 | Retrospective | 1815 | RDP VS LDP VS ODP |

| Yan_2015[87] | China | 2010-2012 | Retrospective | 91 | LDP vs ODP |

| Zhang_2017[88] | China | 2010-2017 | Retrospective | 74 | LDP vs RDP |

| Zhang_2022[89] | China | 2020-2021 | Retrospective | 201 | LDP vs RDP |

| Cho_2011[90] | USA | 1999-2008 | Retrospective using a prospectively maintained database | 693 | LDP vs ODP |

| Chopra_2021[91] | USA | 2008-2019 | Retrospective with prospectively maintained database | 146 | LDP vs ODP vs RDP |

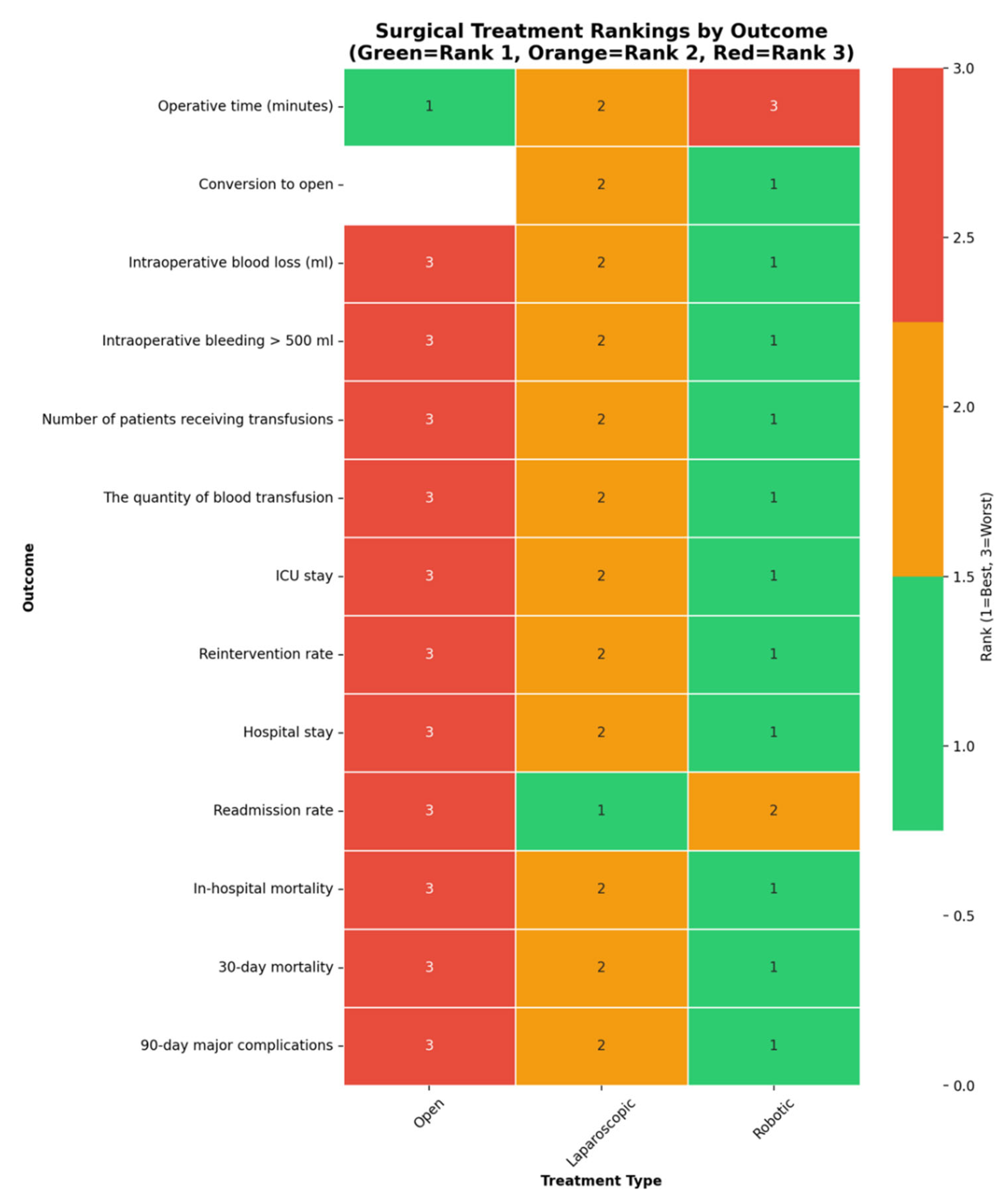

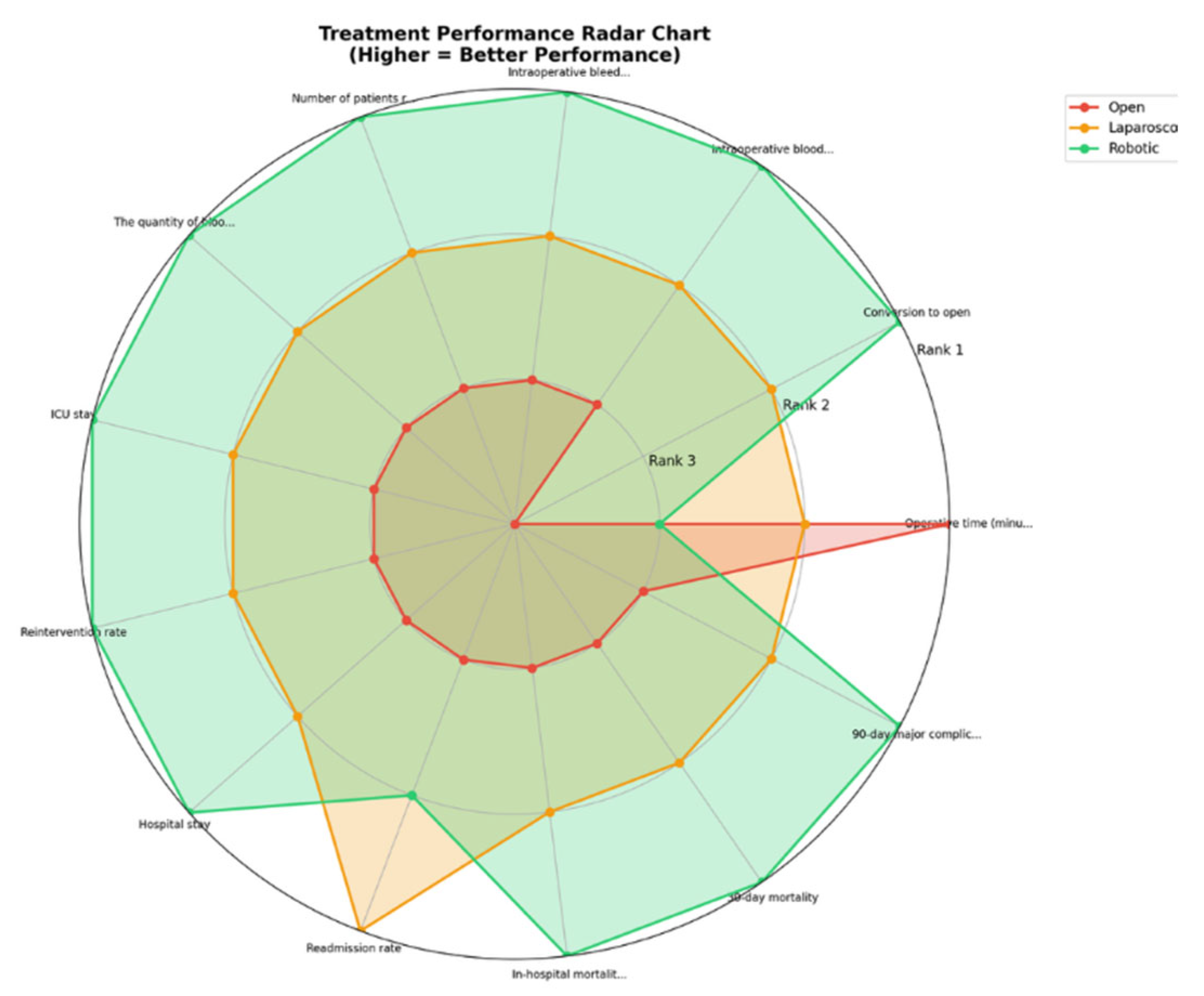

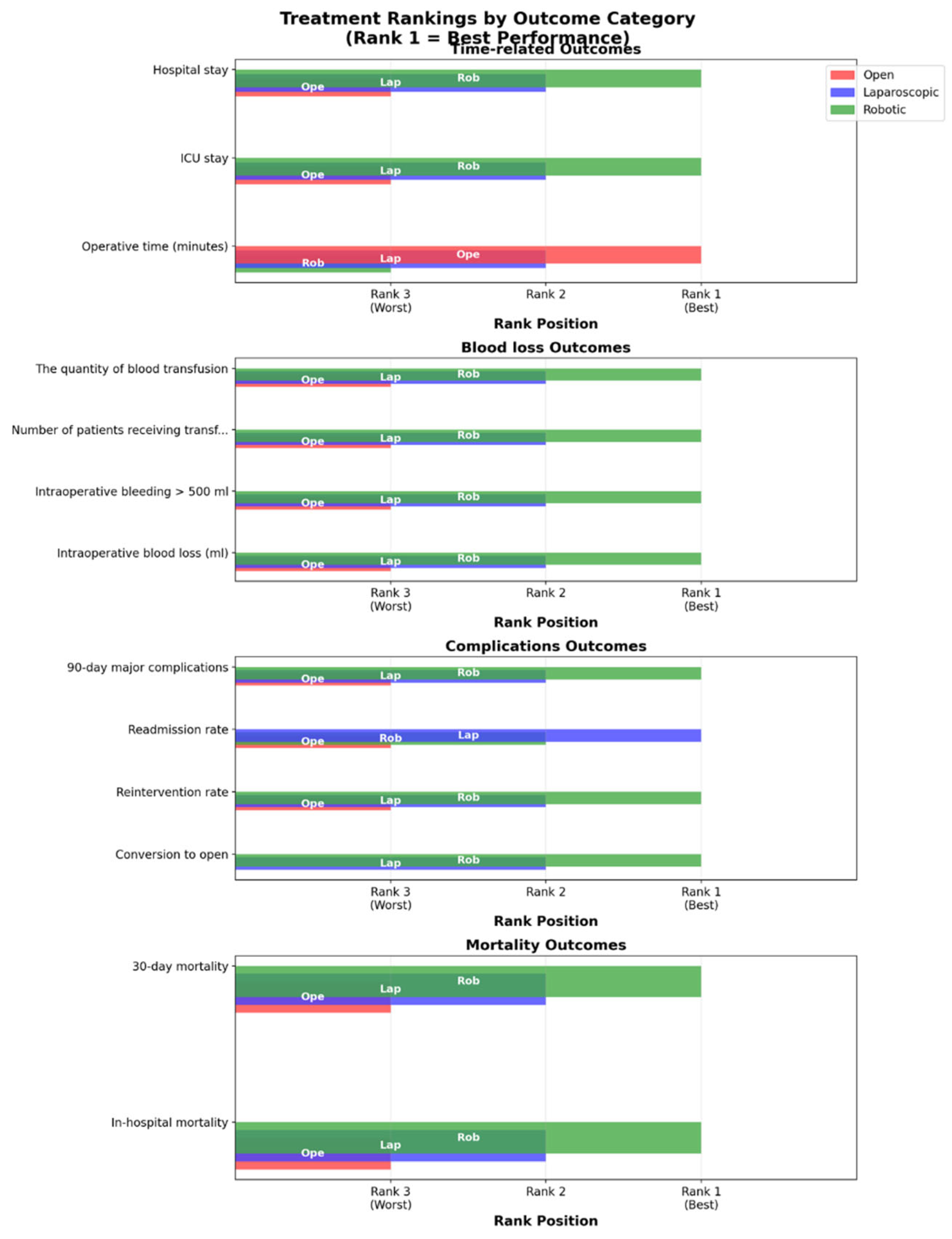

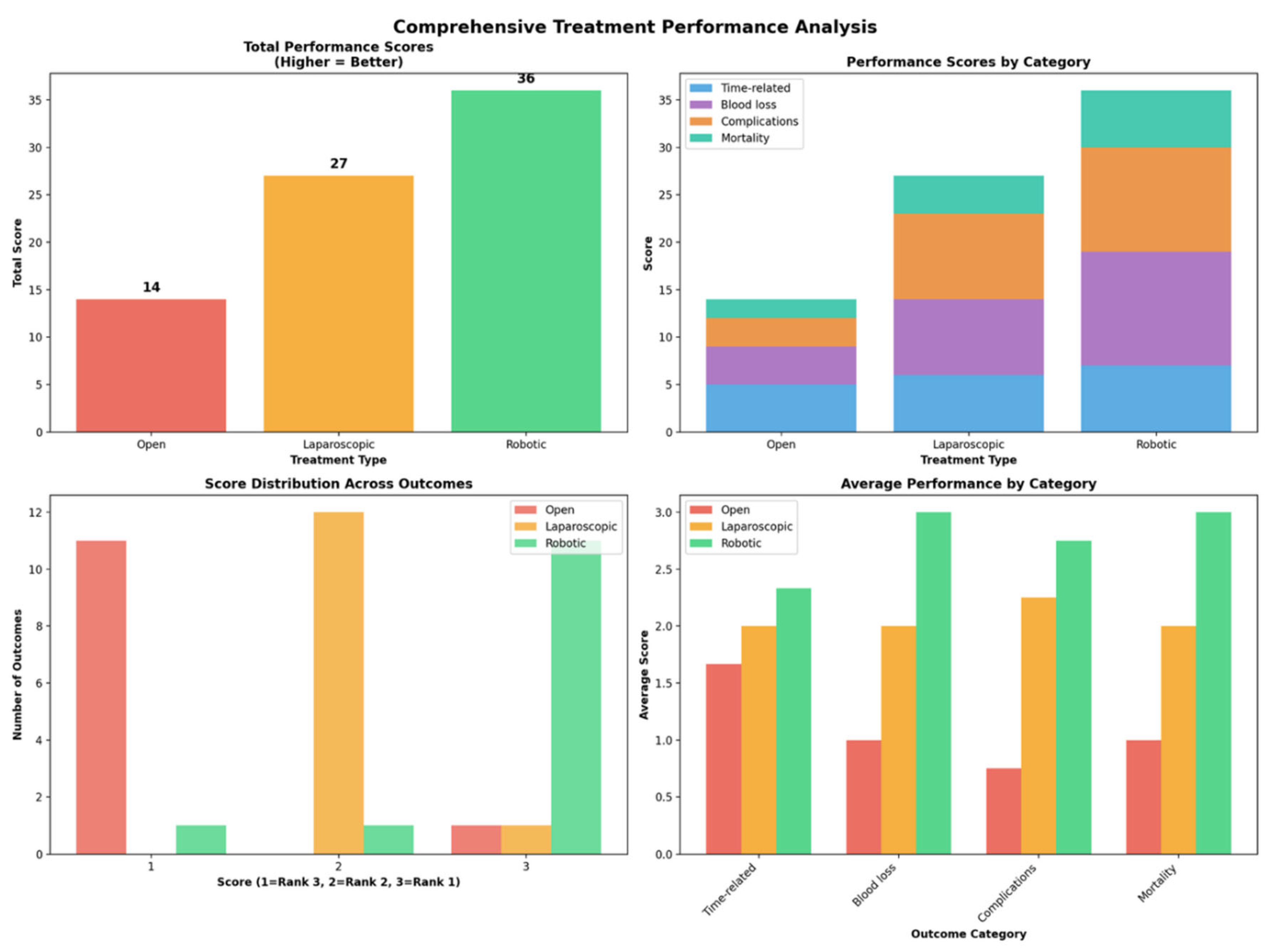

| Outcome | Number of studies | Number of patients | Robotic versus Open | Laparoscopic versus Open | Robotic versus laparoscopic | Ranks based on SUCRA values: I, II, III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequentist NMA | Bayesian NMA | Frequentist NMA | Bayesian NMA | Frequentist NMA | Bayesian NMA | |||||

| Population characteristics |

Age of patients (years) (Frequentist - MD, 95%CI; Bayesian - MD, 95% CrI) |

59 | 17,542 |

-1.65 [-3.00; -0.30] |

-1.67 (-3.11, -0.27) |

-0.72 [-1.86; 0.41] |

-0.74 (-1.95, 0.43) |

-0.93 [-1.93; 0.07] | -0.93 (-1.97, 0.11) |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

Sex of patients ( male) (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

63 |

18,030 | 0.73 [0.64; 0.82] | - | 0.76 [0.69; 0.84] | - | 0.95 [0.87; 1.05] | - |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

|

ASA status (grade I-II) (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

40 | 10,318 | - | 1.24 (0.87, 1.8) | - | 1.29 (0.94, 1.78) | - | 0.96 (0.74, 1.27) | Laparoscopic Robotic Open |

|

|

Previous cardiovascular diseases (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

12 | 3,307 | 0.99 [0.62; 1.61] | 0.84 (0.41, 1.45) | 0.94 [0.69; 1.29] | 0.94 (0.62, 1.37) | 1.19 [0.72; 1.96] | 0.9 (0.46, 1.49) | Laparoscopic Robotic Open |

|

| Intra-operative characteristics |

Operative time (minutes) (Frequentist - MD, 95%CI; Bayesian - MD, 95% CrI) |

61 | 16,230 | 25.93 [7.68; 44.18] | 27.17 (4.27, 50.33) | 7.63 [-7.59; 22.85] | 7.84 (-11.24, 26.94) | 18.30 [5.12; 31.49;] | 19.32 (2.74, 36.27) |

Open Laparoscopic Robotic |

|

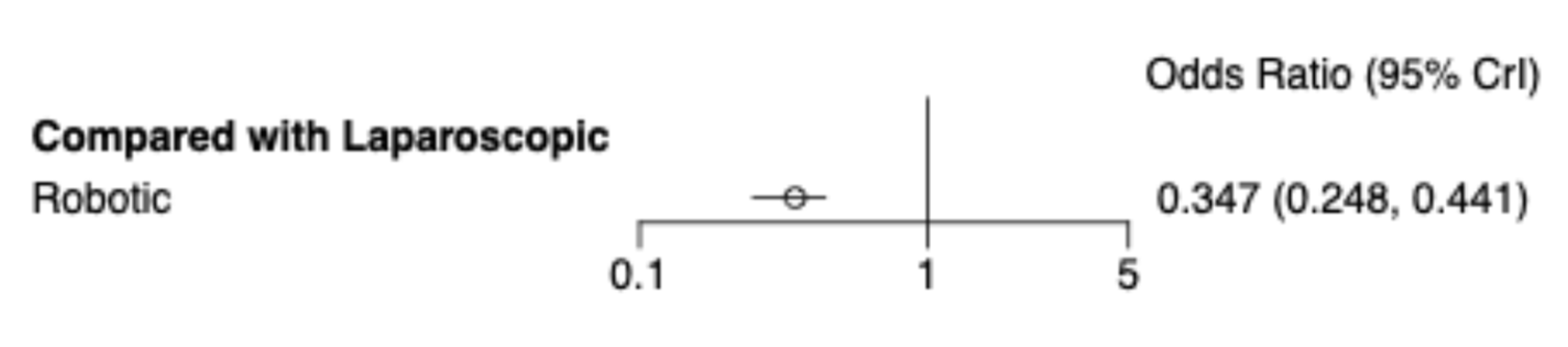

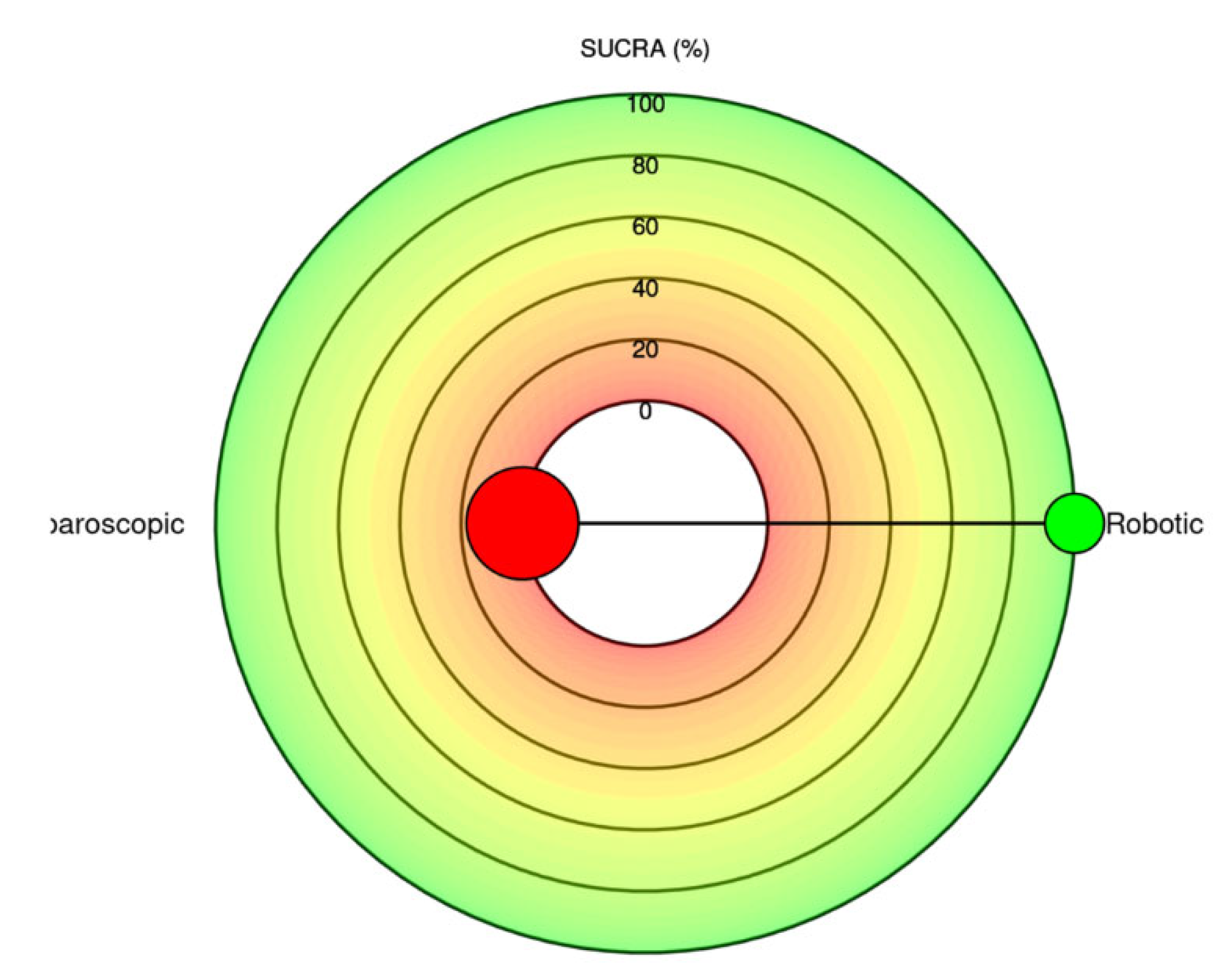

Conversion to open (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

38 | 10,586 | - | - | - | - | 0.41 [0.34; 0.49] | 0.30 [0.22; 0.40] |

Robotic Laparoscopic |

|

|

Intraoperative blood loss (ml) (Frequentist - MD, 95%CI; Bayesian - MD, 95% CrI) |

51 | 12,257 | -279.45 [-318.28; -240.61] | -303.98 (-382.8, -229.26) | -248.99 [-283.41; -214.57] | -272.89 (-340.15, -209.01) | -30.45 [ -54.66; -6.25] | -31.17 (-81.92, 19.44) |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

|

Intraoperative bleeding > 500 ml (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

3 | 1,427 | 0.11 [0.01; 1.07] | - | 0.32 [0.23; 0.46] | - | 0.33 [0.03; 3.24] | - | Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

|

Number of patients receiving transfusions (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

30 | 9,248 | 0.25 [0.19; 0.34] | - | 0.30 [0.24; 0.37] | - | 0.85 [0.66; 1.10] | - |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

|

The quantity of blood transfusion (Frequentist - MD, 95%CI; Bayesian - MD, 95% CrI) |

4 | 363 | 1.98 [-3.42; -0.54] | - | -1.86 [-3.12; -0.59] | - | -0.12 [-1.14; 0.89] | - |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

| Postoperative characteristics |

ICU stay (Frequentist - MD, 95%CI; Bayesian - MD, 95% CrI) |

9 | 1,272 | -4.01 [-5.97; -2.05] | - | -2.27 [-3.71; -0.83] | - | -1.74 [-3.52; 0.04] | - |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

Reintervention rate (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

37 | 11,568 | - | 0.45 (0.23, 0.84) | - | 0.56 (0.32, 0.96) | - | 0.81 (0.47, 1.3) |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

|

Hospital stay (Frequentist - MD, 95%CI; Bayesian - MD, 95% CrI) |

63 | 18,113 | -7.63 [-8.65; -6.61] | -8.77 (-13.34, -4.22) | -6.47 [-7.33; -5.60] | -6.93 (-10.67, -3.23) | -1.16 [-1.88; -0.44] | -1.83 (-5.17, 1.55) |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

| Morbidity and Mortality |

Readmission rate (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

31 | 12,330 | 0.93 [0.67; 1.30] | 0.80 [0.59; 1.09] | 0.86 [0.71; 1.05] | Laparoscopic Robotic Open |

|||

|

In-hospital mortality (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

9 | 1,009 | - | 1.14e-07(5.812-24, 1.36e+06) | 0.76 [0.21; 2.72] | 0.42 [0.04; 2.57] | - | - | Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

|

30-day mortality (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

31 | 12,127 |

0.37 [0.16; 0.84] |

- | 0.68 [0.40; 1.17] | - | 0.54 [0.27; 1.07] | - |

Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

|

90-day major complications (Frequentist - OR, 95%CI; Bayesian - OR, 95% CrI) |

3 | 1,427 | 0.86 [0.44; 1.68] | 0.87 (0.36, 2.42) | 0.88 [0.51; 1.52] | 0.9 (0.45, 2.3) | 0.98 [0.56; 1.71] | 0.97 (0.42, 1.99) | Robotic Laparoscopic Open |

|

| 95%CI – 95% Confidence Interval; 95%CrI – 95% Credible Interval; MD – mean difference; NMA – network meta-analysis; OR – odds ratio; SUCRA - Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking curve | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).