1. Introduction

The SIMMILR (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection

) project was started to try and better understand the real advantages and potential disadvantages of the complete robotic surgical systems (CRSS)[

1]. As we continued to do studies, it became clear to us that many liver surgeons are reporting their results as “laparoscopic” when, in fact, they were actually using aspects of robotics[

2]. Because of this observation, we decided to embark on this current study in an effort help surgeons better understand what robotic surgery is according to an engineering perspective.

While all robots are mechatronic systems, not all mechatronic systems are robots. Mechatronics is a broad interdisciplinary field that encompasses electrical, control and mechanical engineering and computer science. Mechatronics deals with the optimization and design of intelligent products and systems. While all robots are examples of mechatronic systems, not all mechatronic systems are robots. This is because robotic systems also include autonomous actions or decision making. Specifically, they must have, at least, one of the following: (1) sensors that can sense their environments, (2) the ability to process data and make decisions based on the information and/or (3) the capability to act independently. This definition comes from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO 8373:2012 Robots and robotic devices-Vocabulary) and defines a robot as an “actuated mechanism programmable in two or more axes with a degree of autonomy, moving within its environment, to perform intended tasks.”

The exponential advancements in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) have forced surgeons to re-evaluate previous definitions of robotic-assisted surgery (RAS)/robotic surgery[

3,

4]. Current CRSSs(e.g. da Vinci, Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California, USA; Mantra, SSInnovations, New Delhi India; Hugo RAS system, Medtroinc, Dublin, Ireland) are just remote-controlled systems where the operating surgeon controls the arms and there is essentially only level one surgical autonomy, e.g. telemanipulation only[

5]. Notably, the more recent da Vinci robots can be attached to an intelligent operating table that autonomously moves the robotic arms during repositioning of the table (TruSystem 7000dV Surgical Table, TRUMPF Medizin Systeme GmbH & Co, Saalfeld, Germany), and can also use a gastro-intestinal stapler that autonomously adjusts compression speed based on sensor readings on tissue thickness (SmartFire technology, Sure Form staplers, Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California, USA)[

6]. Although, these are early and limited examples of robotics, studies comparing open, laparoscopic and RAS approached, often ignore the subtleties of what robotic surgery actually is.

When comparing RAS to laparoscopy, the current understanding of RAS is that although it is technically a form of minimally invasive surgery like laparoscopy, it also has 3-dimensional (3-D) imaging, articulating instruments with 7 degrees of freedom, one robotic arm holding the camera and 3 additional robotic arms. The reality is that we do not know which of these additional features actually provides any benefit. In many ways, we have skipped many steps in the evolution towards robotic surgery. This is perhaps best understood when we look at smaller robots with only 2 robotic arms, but that also have autonomous laparoscope tracking (Maestro Robot, Moon Surgical, Paris, France) and handheld surgical robots[

7,

8]. In essence, it could be argued that initial “robotic “ surgeons essentially brought a “bazooka to a knife fight,” without properly evaluating all aspects of CRSSs.

Because of this, we used liver resection for CRLM, as a model to try and dissect what actual benefits arise from the utilization of current CRSS. The initial SIMMILR (Study: International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection) was for Colorectal Liver Metastases (SIMMILR-CRLM) was a propensity score matched (PSM) study that reported short-term outcomes of patients with CRLM who met the Milan criteria and underwent either open, laparoscopic or robotic liver resection[

1]. SIMMILR-2, reported the long-term outcomes from that initial study (now referred to as SIMMILR-1)[

1,

9]. A subsequent study analyzed data from 3 international centers doing RAS liver resection for CRLM vs. 1 center that did laparoscopic liver resection with a robotically-controlled laparoscope holder (VidendosKopY, Endocontrol, Grenoble, France) and also using a handheld autonomous gastrointestinal (GIA) handheld stapler device (Signia, Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland)[

7,

8]. This study, which should probably be now known as SIMMILR-3 inspired this current study, SIMMILR-4.

RAS is best used to define devices that enable level 1 surgical autonomy (e.g., telemanipulation, local or remote). Telemanipulator surgery is when the operating surgeon operates away from the OR table via a remote-controlled system. Collaborative robotic or cobotic surgery refers to surgical procedures performed through active collaboration between a surgeon and a robotic system that could have partial autonomy, and thus corresponds to levels 2 to 4 on the surgical autonomy scale. In cobotic surgery, decision-making and task execution are shared, with the robot contributing perceptual, cognitive, or motor functions to assist, guide, or perform parts of the procedure, while the surgeon retains supervisory control and clinical judgment. Robots are defined as devices that can replicate or replace human actions. As a result, robotic surgery implies any autonomy from the surgical robot, therefore, surgical autonomy levels 2-5 encompass the concept of robotic surgery.

Currently, we have identified 5 ways of doing liver resection : open (O), laparoscopic (L), laparoscopic with 3-D imaging (3D), laparoscopic with a single robotic arm holding the laparoscope (1RA)and lastly when the CRSS was used (4RA). By comparing the short-term outcomes of these 5 different approaches we hope to better understand the direction that future development in robotic surgery should take. It is theorized that smaller collaborative robotics (cobots), may reduce costs and liberate more research dollars for further advancements in AI and autonomous actions in surgery.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Selection & Indication for Surgery

We collected perioperative data as well as follow-up data of all eligible patients who underwent O, L, 3D, 1RA or 4RA for colorectal metastasis between June 2004 and November 2024. All hepatectomies for colorectal liver metastases were done by surgeons with experience in both open and minimally invasive liver resection at 5 different international centers (2 in France, 1 in Switzerland, 1 in Germany and 1 in Jordan). Minimum case requirements for participating HPB surgeons in this study was the completion of at least, 50 laparoscopic and/or robotic hepatectomies and, at least, 50 hepatectomies for CRLM.

Patients were divided into 5 approaches: open (O), standard laparoscopic (L), laparoscopic with 3-dimensional imaging(3D), laparoscopy with 1 robotic arm assistance (1RA) and laparoscopy with 4 robotic arm assistance (4RA). Patients were taken from 5 centers, 4 in Europe and 1 in the United States. All centers did open and laparoscopic resection, 3 centers did 4RA resections, 1 center did 3D resections and the 1 center that did 1RA also utilized handheld robotic GIA staplers. Because some surgeons using the 4RA system did not have access to the Sure Form staplers (SmartFire technology, Sure Form staplers, Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California, USA) we only emphasized the solitary robotic arm (1RA) for the name of this cohort. A total of 10 head-to-head comparisons were analyzed. (1) O vs. L, (2) O vs. 3D, (3) O vs. 1RA, (4) O vs 4RA, (5) L vs. 3D, (6) L vs 1RA, (7) L vs 4RA (8) 3D vs 1RA, (9) 3D vs 4RA and (10) 1RA vs 4RA. Unlike SIMMILR-1,2 and 3, the low patient numbers of patients undergoing 3D and 1RA, prevented us from limiting resections to patients within the Milan Criteria for SIMMILR-4.

Surgery was indicated for resectable liver metastases, either synchronous or metachronous, in colorectal cancer patients. Histological confirmation was obtained before surgery when needed. Otherwise, clear imaging evidence of liver metastasis was sufficient. However, to ensure patient-centered care, treatment options—perioperative, surgical, or alternative—were reviewed by a multidisciplinary tumor board (MDT) beforehand. Absolute contraindications to minimally invasive liver surgery included closed-angle glaucoma and intracranial hypertension. Severe lung disease was considered a relative contraindication.

Comparisons of cohorts were divided into 3 categories, open (O) vs. traditional groups of minimally invasive surgery (L and 4RA), laparoscopy (L) vs. cobotic-assisted approaches (3D and 1RA) and lastly cobotic-assisted approaches vs. robotic-assisted approaches (4RA).

2.2. Study Endpoints

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients who received liver resection for colorectal metastases. Individuals who had prior Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy (ALLPS), ablation therapy, or repeat resections were excluded. Cases initiated with a minimally invasive technique were assessed on an intention-to-treat basis. Study data can be accessed from the corresponding author upon justified request.

Demographics and confounding variables used for the propensity score matching (PSM) included : age, sex, American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) class, BMI (Body Mass Index) calculated as m2/kg, history of previous surgery, neoadjuvant therapy (e.g. chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy and/or mmunotherapy), largest metastasis size in mm, number of metastases, location in deep segments and type of liver resection (Major or Minor). The main outcome measured was short-term mortality (death within 30 or 90 days post-surgery). Secondary measures included operative factors (blood loss, OR duration), hospitalization period, R0 resection status, and major complications. The Dindo-Clavien system classified postoperative issues, with severe cases defined as grade ≥ 3. PSM ensured better technique comparison.

Written informed consent was acquired from all participants, specifying that anonymized data might be used in later research. The STROBE checklist guided manuscript preparation for observational study reporting. Surgical techniques and definition of extent of liver resection have been previously described in SIMMILR 1-3.

2.3. Data Analysis

Statistical evaluation was conducted using Social Science Statistics software (

www.socscistatistics.com, accessed 22 December 2021) and SPSS (v26; IBM, Armonk, NY). Categorical variables (nominal/ordinal) were shown as counts (n) and/or percentages (%). Cohort comparisons used Pearson’s χ² test or Fisher’s exact test (if any cell had <5 observations). Continuous measures were reported as mean±SD.

For continuous comparisons, the Mann-Whitney U-test was applied for datasets with <200 unique values, while Student’s t-test was used for 200-500 distinct values. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 defined statistical significance (no multiplicity correction).

2.4. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

PSM was performed to reduce confounding by indication in this retrospective observational study. PSM is a robust statistical method commonly used in non-randomized settings to emulate some of the balance achieved in randomized controlled trials. In this analysis, the propensity score was estimated using a logistic regression model, where treatment assignment served as the dependent variable and relevant covariates—including demographic, clinical, and procedural characteristics—were included as independent variables. The goal was to derive a summary score reflecting each patient’s probability of receiving the treatment, conditional on the observed covariates.

After estimating the propensity scores, a nearest-neighbor matching algorithm without replacement was employed to form matched pairs. A caliper width of 0.2 times the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score was used to ensure tight matching, thereby limiting residual imbalance. Patients in the treatment cohort were matched to those in the control cohort with similar propensity scores, and unmatched subjects were excluded from the final analysis. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated before and after matching to assess covariate balance; an SMD less than 0.1 was considered indicative of adequate balance.

Matching diagnostics and visualization techniques, including density plots and Love plots, were used to further validate the adequacy of the matching procedure. Post-matching comparisons of outcomes between cohorts were conducted using appropriate statistical tests, accounting for the matched design. All analyses were performed using Python with the pymatch and statsmodels libraries, and the entire procedure adhered to best practices in observational comparative effectiveness research.

This methodological approach was selected to minimize bias from confounding variables and strengthen causal inference regarding the association between the surgical intervention and outcomes. By ensuring that matched cohorts were well balanced across baseline characteristics, the risk of spurious associations due to selection bias was substantially reduced.

3. Results

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 show the demographics, confounding and short-term outcome variables for liver resection for colorectal liver metastases after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection). These tables showed the demographics and confounding variables.

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 showed the short-term outcome variables.

Table 1 and

Table 4 replicate the SIMMILR-1 study comparing Open, standard Laparoscopic and RAS liver resections with the CRSS, all centers in this study used the da Vinci robot (da Vinci, Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

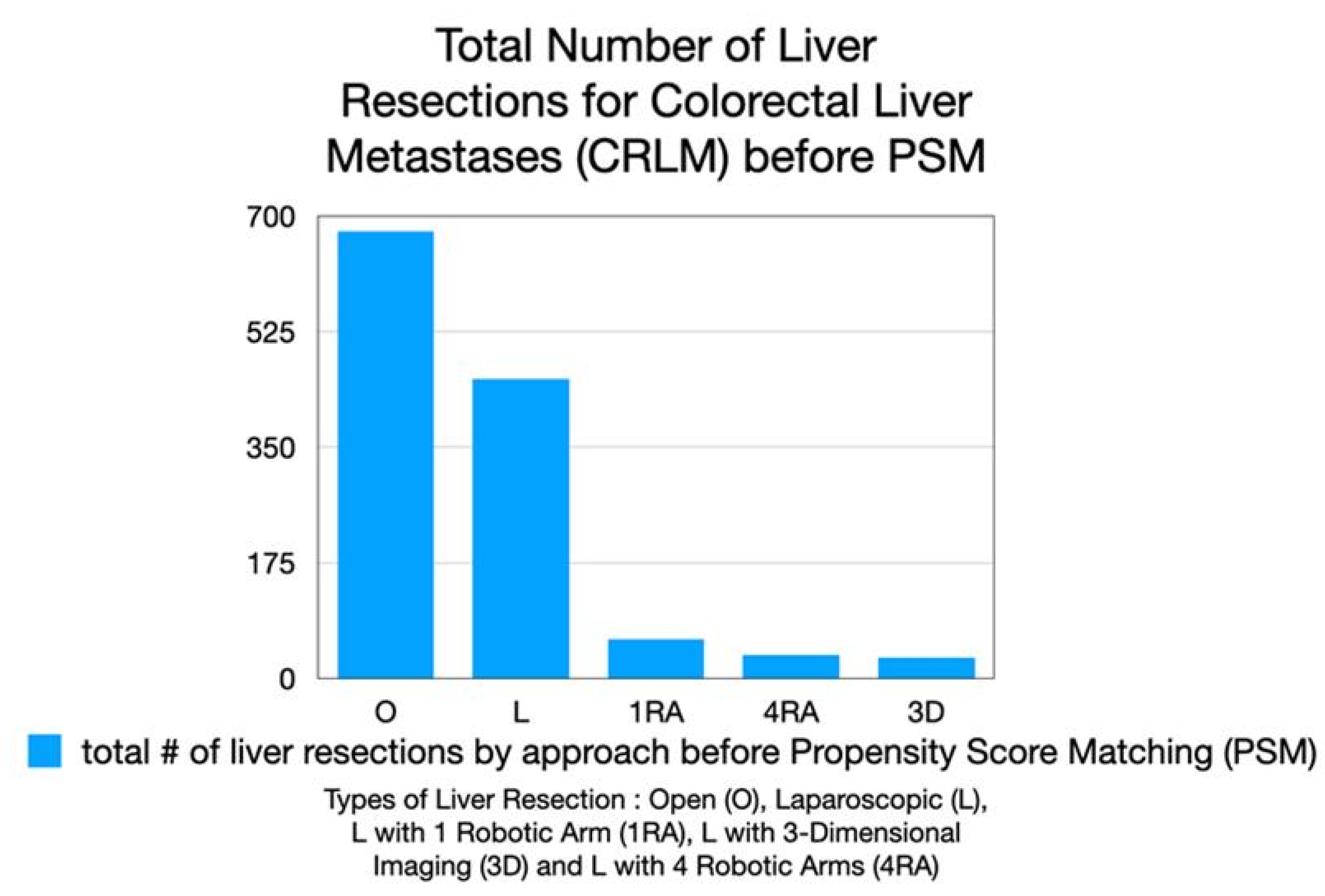

A total of 1,257 patients undergoing liver resection for colorectal liver metastases were identified from the 5 centers : 677 underwent open (O) resection, 453 standard laparoscopic (L) resection, 60 laparoscopic resection with a single robotic arm holding the laparoscope and a handheld robotic GIA stapler device (1 RA), 36 RAS resection with the CRSS (4 RA)and 31 via laparoscopy with 3-D imaging (3D) (

Figure 1).

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 found no statistically significant differences after PSM in the preoperative demographics and confounding variables, however, as seen below, some variables approached statistical significance.

In

Table 1, resected lesions tended to be in the deep segments more often in the Open (O) cohort when compared to the standard Laparoscopy (L) cohort, 71.2% vs. 63.8% (p=0.07), respectively. Additionally, the standard Laparoscopy cohort tended to undergo more major resections, 48% vs 42% (p=0.06), respectively. Open (O) vs. 4 Robotic Arm (4 RA) liver resection, more metastases were removed in the O cohort, 2.1 vs. 1.8 metastases in the 4 RA cohort (p=0.06). When standard Laparoscopic (L) resection was compared to Laparoscopy with 3-D imaging (3D) (

Table 2), the 3D cohort tended to have a higher percentage of patients who had undergone previous abdominal surgery, 95.2% vs. 76.2% (p=0.08), respectively. Lastly, when 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1 RA) liver resection was compared with 4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4 RA) surgery, patients in the 4 RA cohort tended to have higher ASA classification (p=0.06), notably, there were only 9 patients in each of these cohorts (

Table 3).

When the short-term outcome variables were studied, multiple significant and highly significant findings were identified (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). Similar to findings in SIMMILR-1, EBL, LOS, Clavien-Dindo morbidity ≥3, 30 and 90 day mortality and R1 resection rates were all improved in the L cohort when compared to the O cohort (

Table 4). In fact, all findings were highly statistically significant (p<0.001) except for the morbidty rate, which was only statistically significant with a p-value of 0.04. Notably, however, the operative time was lower in the O cohort and this finding was highly statistically significant, 260 vs 246 minutes, respectively. When O was compared to 4 RA liver resection (

Table 4), EBL and LOS were lower in the 4 RA cohort and, these findings were highly statistically significant. Postoperative Clavien-Dindo morbidity ≥ grade 3 rates tended to be lower in the 4 RA cohort, but this did not achieve statistical significance (p=0.07). When standard laparoscopy (L) was compared to 4 Robotic Arm (4 RA) liver resection (

Table 4), the only statistically significant differences were in the longer operative times after RA, 301 vs. 234 minutes (p<0.001), respectively. Interestingly, R0 resections rates were superior after L resections, 88% vs. 64% (p=0.022). Although conversion rates tended to be lower after 4 RA resections, 3% vs. 15% (p=0.09), this only tended to be significant.

Table 5 attempted to show what advantages 1RA and 3D had when compared to standard laparoscopic liver resection and to each other. EBL was significantly lower in the 3D cohort, 219 vs. 424 mL (p=0.02). However, LOS tended to be higher in the 3D cohort when compared to the L cohort, 7 vs 5 days (p=0.09). When a single robotic arm holding the laparoscope and handheld laparoscopic staplers (1 RA) were added to laparoscopy (

Table 5B), LOS and conversion rates tended to be lower in the 1 RA cohort, 4 vs 9 days (p=0.07) and 2 vs 12% (p=0.09), however, these differences were not statistically significant. When laparoscopic resections with 1RA were compared to 3D, OR time was significantly longer in the 1 RA cohort, 357 vs. 212 minutes (p=0.002), but this was tempered by a statistically significant decrease in LOS, 6 vs. 11 days (p=0.008), respectively.

Table 6 attempted to show what advantages cobotic-assisted (1RA and 3D) resections had when compared to 4RA. When 3D was compared with 4 RA liver resections for CRLM and found that OR times could be significantly decreased after 3D when compared to 4 RA, 209 vs. 278 minutes (p=0.01), however, LOS was also significantly longer, 9 vs 5 days (p=0.03), respectively. Notably, no short-term outcome variable showed any difference that was statistically significant when liver resections for CRLM were done via 1 RA or 4 RA.

4. Discussion

This multi-centric retrospective study, conducted across 5 international centers, analyzed short-term outcomes of various types of minimally invasive liver resection to determine whether, and in what ways, the use of the CRSS offers advantages during removal of CRLMs. Comparisons of O, L, 1RA and 4RA liver resection essentially confirmed findings from previous studies with a few differences[

1,

8]. In SIMMILR-1 EBL and LOS were lower after L resections compared to O resections, 353mL compared to 636mL and 5 days vs. 9 days, respectively, and both results were highly statistically significant (p<0.0001). While EBL was significantly lower when 4 RA resection was compared to O resection, 224 mL vs. 778 mL and 250 mL vs. 597 mL, p < 0.04 and and, p < 0.008, respectively. In SIMMILR-3 mean OR times were significantly shorter after 1 RA compared to 4 RA resections, 234 min vs. 290 min (p=0.04), however, no PSM was done[

8].

In this study when comparing O to L resection, 257 patients were in each cohort compared to only 142 in SIMMILR-1 and the benefits of MIS become more pronounced with essentially all outcome variables improved after L resections except OR time which is significantly shorter after O resections (

Table 1). These observations have been noted in other studies, however, a large randomized controlled trial noted no differences in operative times[

10,

11]. When O resections are compared to 4 RA resections in this study, patient numbers in each cohorts are still relatively low but increased to 36 from 22.With this increased cohort, LOS was shown to improve after 4 RA resections, in addition, decreased EBL was also seen in SIMMILR-1. Although EBL was improved when L was compared to 4RA resections after SIMMILR-1, this was no longer seen in SIMMILR-4, with only OR time being significantly longer after 4RA resections (with cohorts increased from 21 to 35). Comparisons with SIMMILR-3 are not possible, because although SIMMILR-3 had 49 patients in the 1RA cohort and 28 in the 4RA, a PSM wasn’t done, as mentioned above.

Comparisons of O resections with 3D and 1RA approaches was not done, because the potential advantages of MIS liver resection have already been well described, specifically tendency for decrease EBL, LOS but tempered by increased operative times and costs[

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. We did, however, compare L to these 2 more advanced MIS modalities, 3D and 1RA, to see if we could glean any theories as to why 3-D imaging and/or a steady robotically-controlled laparoscopic image and potentially partially autonomous handheld GIA staplers could have on liver resection for CRLM.

Table 5 compared standard laparoscopy to laparoscopy with 3-D imaging, and laparoscopy with a single robotic arm for scope control. Compared with standard laparoscopy, 3-D imaging showed lower blood loss but slightly longer hospital stay. Adding a single robotic arm tended to reduce hospital stay and conversion rates, though differences were small. When the single robotic arm setup was compared with 3-D imaging, operating time was longer, but hospital stay was shorter.

Table 6 compared liver resections using these enhancements to standard laparoscopy to liver resection using the CRSS with 4 robotic arms. When laparoscopy with the addition of 3-D imaging (3D) was compared to liver resections with four robotic arms (4RA), operating time was shorter with 3D resections, but hospital stay was longer. No meaningful differences in short-term outcomes were found when comparing liver resections with 1 robotic arm holding the camera (1RA) with 4RAs. Although R1 resection rates seemed to be higher in the 4RA cohort when compared to the 1RA cohort, this difference was not statistically significant. Other studies have shown excellent R0 resection rates with the CRSS [

13,

18,

19]. In fact, the University of Magdeburg did a meta-analysis where they found that enhanced R0 rate is an advantage of the robot when compared to standard laparoscopy, nonetheless, enhancements via cobotics may eliminate this perceived advantage[

19].

3-Dimensional Imaging

The first and most pressing issue that should probably have received more attention, was how 3-D laparoscopy improved short and long-term outcomes after liver resection. Granted, this may have been exacerbated by the fact that earlier versions of 3-D laparoscopy weren’t as sophisticated as more modern versions and were, therefore, more difficult to adopt. Nevertheless, two-dimensional (2-D) laparoscopy presents several challenges, including a lack of depth perception, increased difficulty in managing vascular structures, and a longer learning curve for surgeons[

20]. In contrast, 3-D laparoscopy has been developed and utilized to overcome these limitations by improving visual clarity and most importantly spatial orientation during surgery. A review of four studies involving 361 patients (159 in the 3-D cohort and 202 in the 2-D cohort) highlighted potential benefits of 3-D laparoscopy, particularly during liver resections[

21]. Although EBL, reoperation rates, and in-hospital mortality showed no significant differences between the two cohorts, overall morbidity was found to be lower when 3D laparoscopy was implemented. It is important to note that none of the studies provided details on the learning curve, which may have influenced outcomes.

Some clinical trials suggest that 3-D laparoscopy offers shorter operative times, reduced blood loss, and improved precision, especially in complex liver procedures[

22,

23]. Surgeons report enhanced depth perception and potentially faster skill acquisition when using 3-D systems[

24]. These advantages may lead to safer and more efficient operations. However, certain limitations exist, including the higher cost of 3-D equipment, the need for additional training, and occasional reports of visual fatigue. Despite these drawbacks, the adoption of 3-D laparoscopy appears to support enhanced surgical performance when utilized[

25].

The value of 3D imaging is even easier to appreciate when we acknowledge the inroads being made with 3-D printing of liver anatomy and tumors and the now decades long quest for 3-D intra-operative navigation support via augmented reality (AR) [

20,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Notably, ICG imaging seems to be superior to current AR solutions, and researchers have begun to hypothesize that it may be necessary to combine ICG with AR to get accurate and useable intra-operative navigation support during liver resection[

33,

34].

The Rise of Artificial Intelligence in Surgery

The Internationally Validated European Guidelines on Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery (EGUMILS) organized by Professor Abu Hilal were published in the British Journal of Surgery in 2025 and identified a severe discordance among surgeons regarding the definitions of various minimally invasive techniques for liver resection, specifically, what constitutes robotic-assisted liver surgery[

35]. Although surgeons for years have considered the remotely controlled 4 arm CRSS as a surgical robot, earlier versions were just tele-manipulators and, in fact, did not meet the criteria to be considered truly robotic[

15].

With the arrival of the age of Artificial Intelligence Surgery (AIS), and therefore, actual examples of intra-operative autonomous actions, surgeons need a better understanding of robotics and updated definitions. Current RAS is really just a form of laparoscopy, with 3-dimensional visualization and 4 robotic arms : (1) that holds the camera, (2) that enable remotely controlled articulating instruments with 7 degrees of freedom and a final arm that the operating surgeon can also control, albeit the surgeon has to toggle control and cannot control this third arm simultaneously. Notably, there are even problems with the term laparoscopy. Deriving from the Greek, lapara meaning flank or side and skopein meaning to see, it is not used in many parts of europe. In France and Spain, for example, the term coelioscopic is used instead of laparoscopic with koilia coming from the greek word for belly or cavity.

If a 3-D laparoscopic camera is held by a robotically-controlled camera holder, and all stapling is done with autonomous handheld GIA staplers and this has the same results as liver resections done with a vastly more expensive CRSS, perhaps the money saved by not having to buy a CRSS could be used for the creation of AI-powered decision support preoperatively during tumor boards, post-operatively to help enhance the detection of complications and even permit the creation of intra-operative navigation via functional augmented reality (AR) and real-time decision support[

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Nonetheless, the ethics regarding the application of these technologies in surgery and other parts of society still requires much debate and caution as economic and societal implications are still poorly understood[

41,

42].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although propensity score matching (PSM) was used to reduce selection bias, the retrospective design means that unmeasured confounders may still affect the results. The relatively small sample sizes in some cohorts — particularly the 3D, 1RA, and 4RA cohorts — limit the ability to detect meaningful differences. Differences in surgical techniques and robotic platforms across centers may also introduce variability that was not fully controlled. In addition, the analysis focuses on short-term outcomes, leaving long-term oncological results such as disease-free and overall survival unexamined.

Another limitation is the changing definition of robotic surgery, which complicates direct comparisons between minimally invasive approaches. The classification of robotic assistance (for example, 1RA vs. 4RA) may not fully reflect differences in autonomy or the capabilities of newer systems. The lack of standardized protocols for robotic-assisted liver resections across centers could also lead to inconsistencies in technique and postoperative care. Finally, the rapid pace of innovation in surgical robotics means that some findings may become outdated as newer systems with greater autonomy and AI integration are introduced. These factors highlight the need for prospective, randomized trials to better determine the advantages of different robotic approaches in liver surgery.

5. Conclusions

This multi-center study compared five surgical approaches for liver resection in colorectal metastases, demonstrating that minimally invasive techniques—particularly laparoscopy robotic assistance—offer advantages in blood loss and hospital stay over open surgery. However, the benefits of full robotic systems (4RA) over simpler cobotic-assisted methods (1RA or 3D laparoscopy) remain unclear, with longer operative times and no significant improvements in key outcomes. The findings suggest that cost-effective, modular cobotic enhancements (e.g., autonomous camera holders or staplers) may provide comparable benefits to complete robotic platforms, allowing resources to be redirected toward AI-driven surgical innovations. Future studies should focus on prospective, randomized trials with standardized protocols to further evaluate these evolving technologies.

It must be acknowledged that current telemanipulation surgery is the ideal way for industry to one day create truly robotic surgery, level 5, where no human is involved in the procedure. Current “robotic” surgeons could be sowing the seeds of their own destruction. Because of this, surgeons must continue to assess more collaborative forms of robotic surgery, specifically cobotic-assisted surgery. It could be that cobotics is the best way to keep the surgeon in the looIt must be recalled that the first Grandmaster to lose to a chess competition to a computer, Gary Kasparov, noted that when a machine competed against a human in chess that the computer wins, and that when a computer competes against another computer there is no clear winner. However, when a man and computer join forces, they are superior to a computer alone. It is because of this observation and the findings in this study that we call for increased research in collaborative robotics in surgery, and probably beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.G. methodology, A.A.G., R.C. and A.N.M.; software, A.A.G., A.N.M. and S.A. validation, A.A.G., R.C., formal analysis, A.A.G., A.N.M. and S.A. investigation, A.A.G., R.C. and M.A.H. data curation, A.A.G., R.C., D.F., I.D., H.T., Z.H.L., J.D. and M.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.G. writing—review and editing, A.A.G., R.C., D.F., I.D., H.T., Z.H.L., J.D., A.N.M, V.G., S.A., K.R.and M.A.H.; visualization, A.A.G., R.C., D.F., I.D., H.T., Z.H.L., J.D., A.N.M, V.G., S.A., K.R.and M.A.H.; supervision, A.A.G.,R.C. and M.A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The National Committee for Data Protection (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, registration number 1295794) approved the study, which was conducted in accordance with French legislation.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the study provided standard care and the dataset contained no information that could enable patient identification.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gumbs, A.A.; et al. Study: International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection for Colorectal Liver Metastases (SIMMILR-CRLM). Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, A.A.; TJ Tsai, and J.Hoffman. Initial experience with laparoscopic hepatic resection at a comprehensive cancer center. Surg Endosc 2012, 26, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.G.; et al. What is Artificial Intelligence Surgery? Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2021, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.G. and G. Brice, Why Artificial Intelligence Surgery (AIS) is better than current Robotic-Assisted Surgery (RAS). Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2022, 2, 207–212. [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, A.A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Surgery: How Do We Get to Autonomous Actions in Surgery? Sensors (Basel) 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumbs, A.A.; et al. The Advances in Computer Vision That Are Enabling More Autonomous Actions in Surgery: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, A.A.; et al. Modified robotic lightweight endoscope (ViKY) validation in vivo in a porcine model. Surg Innov 2007, 14, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, A.G.; et al. Keeping surgeons in the loop: are handheld robotics the best path towards more autonomous actions? (A comparison of complete vs. handheld robotic hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases). Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2021, 1, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, A.A.; et al. Survival Study: International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection for Colorectal Liver Metastases (SIMMILR-2). Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretland, A.A.; et al. Laparoscopic Versus Open Resection for Colorectal Liver Metastases: The OSLO-COMET Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg 2018, 267, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerli, C.; et al. Is prolonged operative time associated with postoperative complications in liver surgery? An international multicentre cohort study of 5424 patients. Surg Endosc 2024, 38, 7118–7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; et al. Outcomes of robotic liver resections for colorectal liver metastases. A multi-institutional analysis of minimally invasive ultrasound-guided robotic surgery. Surg Oncol 2019, 28, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.; et al. Robotic and laparoscopic liver resection-comparative experiences at a high-volume German academic center. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2021, 406, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrakis, A.; et al. Three-Device (3D) Technique for Liver Parenchyma Dissection in Robotic Liver Surgery. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; et al. International experts consensus guidelines on robotic liver resection in 2023. World J Gastroenterol 2023, 29, 4815–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; et al. Propensity Score-matched Analysis Comparing Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Minor Liver Resections of the Anterolateral Segments: an International Multi-center Study of 10,517 Cases. Ann Surg 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rahimli, M.; et al. Learning curve analysis of 100 consecutive robotic liver resections. Surg Endosc 2025, 39, 2512–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimli, M.; et al. Robotic and laparoscopic liver surgery for colorectal liver metastases: an experience from a German Academic Center. World J Surg Oncol 2020, 18, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimli, M.; et al. Does Robotic Liver Surgery Enhance R0 Results in Liver Malignancies during Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery? Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Current trends in three-dimensional visualization and real-time navigation as well as robot-assisted technologies in hepatobiliary surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021, 13, 904–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S. and V. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2023, 33, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayutham, V.; et al. 3D visualization reduces operating time when compared to high-definition 2D in laparoscopic liver resection: a case-matched study. Surg Endosc 2016, 30, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; et al. Application of three-dimensional visualization technology in early surgical repair of bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BMC Surgery 2024, 24, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, D.; H Zhuang, and F. Han, Effect and influence factor analysis of intrahepatic Glisson's sheath vascular disconnection approach for anatomical hepatectomy by three-dimensional laparoscope. J BUON 2017, 22, 157–161.

- Kawai, T.; et al. 3D vision and maintenance of stable pneumoperitoneum: a new step in the development of laparoscopic right hepatectomy. Surg Endosc 2018, 32, 3706–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witowski, J.S.; et al. 3D Printing in Liver Surgery: A Systematic Review. Telemed J E Health 2017, 23, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giehl-Brown, E.; et al. 3D liver model-based surgical education improves preoperative decision-making and patient satisfaction-a randomized pilot trial. Surg Endosc 2023, 37, 4545–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.; et al. Computer-assisted intraoperative 3D-navigation for liver surgery: a prospective randomized-controlled pilot study. Ann Transl Med 2023, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzenente, A.; et al. Hyper accuracy three-dimensional (HA3D) technology for planning complex liver resections: a preliminary single center experience. Updates Surg 2023, 75, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchini, F.; et al. 3-D reconstruction in liver surgery: a systematic review. HPB (Oxford) 2024, 26, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mike, S.; et al. Contribution of 3D virtual modeling in locating hepatic metastases, particularly "vanishing tumors": a pilot study. Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2024, 4, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; et al. Impact of three-dimensional reconstruction visualization technology on short-term and long-term outcomes after hepatectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity-score-matched and inverse probability of treatment-weighted multicenter study. Int J Surg 2024, 110, 1663–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeaki, I. , "Bon mariage" of artificial intelligence and intraoperative fluorescence imaging for safer surgery. Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2023, 3, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg, F.B.; et al. ICG-Fluorescence Imaging for Margin Assessment During Minimally Invasive Colorectal Liver Metastasis Resection. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e246548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hilal, M.; et al. The Brescia internationally validated European guidelines on minimally invasive liver surgery. Br J Surg 2025, 112, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, D.A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: Promises and Perils. Ann Surg 2018, 268, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christina, B.; et al. Artificial intelligence in hepatopancreaticobiliary surgery - promises and perils. Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2022, 2, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.M.; et al. Artificial intelligence prediction of cholecystectomy operative course from automated identification of gallbladder inflammation. Surg Endosc 2022, 36, 6832–6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, A.G.; et al. Surgomics and the Artificial intelligence, Radiomics, Genomics, Oncopathomics and Surgomics (AiRGOS) Project. Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2023, 3, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, T.J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-enabled Decision Support in Surgery: State-of-the-art and Future Directions. Ann Surg 2023, 278, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulia, C.; et al. White paper: ethics and trustworthiness of artificial intelligence in clinical surgery. Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2023, 3, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidian, N.; et al. Ethics and trustworthiness of artificial intelligence in Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary surgery: a snapshot of insights from the European-African Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association (E-AHPBA) survey. HPB (Oxford) 2025, 27, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Total number of liver resections for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) performed before propensity score matching (PSM). The distribution of surgical approaches is shown: open resection (O), laparoscopic resection (L), laparoscopic with one robotic arm assistance (1RA), laparoscopic with four robotic arms (4RA), and laparoscopic with three-dimensional imaging (3D). Open and laparoscopic resections represented the majority of procedures, with fewer cases performed using cobotic and robotic approaches.

Figure 1.

Total number of liver resections for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) performed before propensity score matching (PSM). The distribution of surgical approaches is shown: open resection (O), laparoscopic resection (L), laparoscopic with one robotic arm assistance (1RA), laparoscopic with four robotic arms (4RA), and laparoscopic with three-dimensional imaging (3D). Open and laparoscopic resections represented the majority of procedures, with fewer cases performed using cobotic and robotic approaches.

Table 1.

Demographics and Confounding Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Open vs. Traditional con-cepts of Minimally Invasive Surgery [Laparoscopy (L) and 4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4RA)]. M=male; F=Female; ASA=American Society of Anesthesia; BMI=Body Mass Index.

Table 1.

Demographics and Confounding Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Open vs. Traditional con-cepts of Minimally Invasive Surgery [Laparoscopy (L) and 4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4RA)]. M=male; F=Female; ASA=American Society of Anesthesia; BMI=Body Mass Index.

| Demographics, Confounding Variables |

Open (O)(n=257) |

Laparoscopy (L) (n=257) |

p-value |

Open (O) (n=36) |

4 Arm Robotic (4RA) (n=36) |

p-value |

Laparoscopy (L) (n=35) |

4 Arm Robotic (4RA)(n=35) |

p-value |

| Age, mean (range) |

62 (19-86) |

63.5 (23-90) |

0.2 |

58.7 (25-81) |

60.5 (35-83) |

0.6 |

60.8 (34-79) |

61 (34-81) |

0.9 |

| M : F |

159M : 98F |

154M : 103F |

0.2 |

24 M : 12 F |

22 M 14 F |

0.6 |

18:16 |

20:14 |

0.6 |

| ASA |

|

|

0.8 |

|

|

0.9 |

|

|

0.7 |

| 1 |

30 |

28 |

|

2 |

1 |

|

3 |

2 |

|

| 2 |

164 |

158 |

|

21 |

19 |

|

19 |

17 |

|

| 3 |

61 |

70 |

|

12 |

15 |

|

12 |

15 |

|

| 4 |

2 |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| BMI kg/m2 (range) |

26.6 |

26 |

|

25.6 (19.1-40.5) |

25.9 (16.2-37.2) |

0.6 |

24.3 (17.0-34.4) |

25.8 (16.2-30.8) |

0.6 |

| Previous Surgery (%) |

213 (83.0) |

206 (80.0) |

0.4 |

30 (83.3) |

24 (63.9) |

0.6 |

21 (78.8) |

16(52.9) |

0.2 |

| Neoadjuvant Therapy, n (%) |

185 (72.0) |

180 (70.0) |

0.6 |

16 (44.4) |

16 (44.4) |

0.9 |

26 (76.5) |

23(67.6) |

0.8 |

| Chemotherapy |

157 |

153 |

0.4 |

13 |

12 |

|

23 |

20 |

|

| Chemoradiotherapy |

14 |

16 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

2 |

2 |

|

| Immunotherapy |

14 |

8 |

|

2 |

3 |

|

1 |

3 |

|

| Metastasis Size mm (range) |

34.7 (2.5-170) |

34 (6-170) |

0.1 |

39.3 (18-57) |

38.6 (11-85) |

0.3 |

40.5 (7-170) |

38.8 (11-60) |

0.3 |

| Number of Resected Tumors (range) |

1.87 (1-8) |

1.85 (1-6) |

0.5 |

2.1 (1-3) |

1.8 (1-3) |

0.06 |

1.6 (1-3) |

1.7 (1-3) |

0.2 |

| Location in Deep Segments (%) |

183 (71.2) |

164 (63.8) |

0.07 |

23 (63.9) |

18 (55.6) |

0.2 |

16(47.1) |

19 (55.9) |

0.5 |

| Major Resection % |

42 |

48 |

0.06 |

11 (30.1) |

12 (33.3) |

0.5 |

10 (29.4) |

11 (32.4) |

0.8 |

Table 2.

Demographics and Confounding Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Standard laparoscopy (L) vs. Cobotic surgery [3-D Laparoscopy (3D) and 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA)]. M=male; F=Female; ASA=American Society of Anesthesia; BMI=Body Mass Index.

Table 2.

Demographics and Confounding Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Standard laparoscopy (L) vs. Cobotic surgery [3-D Laparoscopy (3D) and 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA)]. M=male; F=Female; ASA=American Society of Anesthesia; BMI=Body Mass Index.

| Demographics, Confounding Variables |

Laparoscopy (L) (n=21) |

3-D Laparoscopy (3D) n=21) |

p-value |

Laparoscopy (L) (n=41) |

1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA) (n=41) |

p-value |

3-D Laparoscopy (3D) (n=11) |

1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA) (n=11) |

p-value |

| Age, mean (range) |

70.6 (44-86) |

69.2 (50-83) |

0.4 |

55.0 (23-70) |

58.3 (30-87) |

0.3 |

64.5 (50-71) |

66.5 (38-84) |

0.4 |

| M : F |

10 M : 11 F |

10 M : 11 F |

1 |

22 M : 19 F |

23 M 18 F |

0.8 |

6 M : 5 F |

5 M : 6 F |

0.7 |

| ASA |

|

|

1 |

|

|

0.7 |

|

|

0.6 |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

2 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| 2 |

14 |

14 |

|

24 |

20 |

|

9 |

8 |

|

| 3 |

6 |

6 |

|

26 |

19 |

|

2 |

3 |

|

| 4 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| BMI kg/m2 (range) |

27.1

(24.7-34.4) |

26.1 (19.3-39.2) |

0.3 |

30.4 (25-37) |

30.6 (27-40) |

0.6 |

30.3 (22-39) |

29.8 (23-39) |

0.9 |

| Previous Surgery (%) |

16 (76.2) |

20 (95.2) |

0.08 |

27 (65.8) |

28 (68.3) |

0.8 |

8 (72.7) |

11 (100) |

0.2 |

| Neoadjuvant Therapy |

17 (81.0) |

13 (61.9) |

0.2 |

31 (75.6) |

32 (78.0) |

1 |

8 (72.7) |

9 (81.8) |

1 |

| Chemotherapy |

17 |

13 |

|

29 |

30 |

|

8 |

9 |

|

| Chemoradiotherapy |

0 |

0 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| Immunotherapy |

0 |

0 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| Metastasis Size mm (range) |

30.4 (5-50) |

31.5 (8-100) |

0.6 |

26.6 (5-85) |

31.5 (10-115) |

0.5 |

36.4 (8-100) |

37.6 (10-115) |

0.8 |

| Number of Tumors (range) |

1.34 (1-3) |

1.67 (1.2) |

0.08 |

1.7 (1-5) |

1.5 (1-8) |

0.2 |

1.8 (1-2)) |

1.4 (1-3) |

0.07 |

| Location in Deep Segments (%) |

11 (52.4) |

14 (66.7) |

0.3 |

26 (63.4) |

27 (65.8) |

0.8 |

7 (63.6) |

8 (81.8) |

0.6 |

| Major Resection % |

4(19.0) |

6(28.6) |

0.5 |

20 (48.8) |

21 (51.2) |

0.8 |

4 (36.4) |

2 (18.2) |

0.3 |

Table 3.

Demographics and Confounding Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Cobotic surgery [3-D Lap-aroscopy (3D) and 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA)] vs. Robotic surgery [4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4RA)]. M=male; F=Female; ASA=American Society of Anesthesia; BMI=Body Mass Index.

Table 3.

Demographics and Confounding Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Cobotic surgery [3-D Lap-aroscopy (3D) and 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA)] vs. Robotic surgery [4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4RA)]. M=male; F=Female; ASA=American Society of Anesthesia; BMI=Body Mass Index.

| Demographics, Confounding Variables |

3D (n=13) |

4 RA (n=13) |

p-value |

1 RA (n=9) |

4 RA (n=9) |

p-value |

| Age, mean (range) |

68.8 (50-78) |

66.2 (34-83) |

1 |

60.2 (32-75) |

60.1 (34-83) |

0.9 |

| M : F |

7 M : 6 F |

10 M : 3 F |

0.2 |

3 M : 6 F |

5 M : 4 F |

0.3 |

| ASA |

|

|

0.8 |

|

|

0.06 |

| 1 |

0 |

1 |

|

0 |

1 |

|

| 2 |

7 |

6 |

|

7 |

2 |

|

| 3 |

6 |

6 |

|

2 |

6 |

|

| 4 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| BMI kg/m2 (range) |

26.6 (16.2-39.2) |

21.6 (16.2-37.2) |

0.7 |

31.9 (30.6-40) |

31.1 (26.9-37.2) |

0.7 |

| Previous Surgery (%) |

12 (92.3) |

10 (77.0) |

0.3 |

6 (66.7) |

6 (66.7) |

1 |

| Neoadjuvant Therapy, n (%) |

8 (61.5) |

5 (38.5) |

0.2 |

4 (44.4) |

3 (33.3) |

0.6 |

| Chemotherapy |

8 |

5 |

|

4 |

3 |

|

| Chemoradiotherapy |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| Immunotherapy |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| Metastasis Size mm (range) |

38.2 (11-100) |

34.7 (11-45) |

0.7 |

45.0 (20-115) |

30.8 (11-39) |

0.67 |

| Number of Tumors (range) |

2 (1-3) |

11.8 (1-3) |

0.2 |

1.2 (1-3) |

1.8 (1-2) |

0.09 |

| Location in Deep Segments (%) |

9 (69.2) |

7 (53.8) |

0.4 |

6 (66.7) |

5 (55.6) |

0.6 |

| Major Resection % |

3 (23.1) |

2 (15.4) |

0.6 |

3 (33.3) |

2 (22.2) |

0.6 |

Table 4.

Short term Outcome Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - In-ternational Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Open (O) vs. Traditional concepts of Minimally Invasive Surgery [Laparoscopy (L) and 4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4RA)]. EBL = Estimated Blood Loss, OR = Operating Room, LOS= Length of Stay.

Table 4.

Short term Outcome Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - In-ternational Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Open (O) vs. Traditional concepts of Minimally Invasive Surgery [Laparoscopy (L) and 4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4RA)]. EBL = Estimated Blood Loss, OR = Operating Room, LOS= Length of Stay.

| Outcome Variables |

Open (O) (n=257) |

Laparoscopy (L) (n=257) |

p-value |

Open (O) (n=36) |

4 Arm Robotic (4RA) (n=36) |

p-value |

Laparoscopy (L) (n=35) |

4 Arm Robotic (4RA) (n=35) |

p-value |

| EBL, mL (range) |

695 (50-3500) |

553 (0-2500) |

<0.0001 |

541.6 (300-600) |

382.2 (100-900) |

0.0006 |

504.5 (40-2500) |

375.0 (50-900) |

0.3 |

| OR Time, min (range) |

245.7 (90-900) |

259.9 (60-540) |

<0.0001 |

280.1 (81-290) |

305.4 (107-522) |

0.342 |

233.7(60-489) |

300.5 (107-537) |

<0.001 |

| LOS, days (range) |

13.6 (2-108) |

8.3 (1-168) |

<0.0001 |

23.6 (4-108) |

7.8 (1-39) |

< 0.00001 |

6.2 (1-57) |

6.8(1-39) |

0.3 |

| Conversion Rate, n (%) |

NA |

21 (8.4) |

NA |

NA |

0 |

NA |

5 (14.7) |

1 (2.9) |

0.09 |

| Postoperative Clavien-Dindo morbidity ≥ grade 3, n (%) |

34 (26.3) |

20 (16.5) |

0.04 |

7 (19.4) |

2 (17.1) |

0.07 |

2(5.9) |

2(5.9) |

1 |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) |

23(10.5) |

2 (0.8) |

0.00002 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) |

24(17.7) |

2 (1.0) |

<0.00001 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| R1 resection, n (%) |

24 (25.1) |

23 (9.7) |

0.0001 |

8 (22.2) |

10 (33.3) |

0.586 |

4 (11.8) |

12 (36.4) |

0.022 |

Table 5.

Short term Outcome Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Standard laparoscopy (L) vs. Cobotic surgery [3-D Laparoscopy (3D) and 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA)]. EBL = Estimated Blood Loss, OR = Operating Room, LOS= Length of Stay.

Table 5.

Short term Outcome Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - International Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Standard laparoscopy (L) vs. Cobotic surgery [3-D Laparoscopy (3D) and 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA)]. EBL = Estimated Blood Loss, OR = Operating Room, LOS= Length of Stay.

| Outcome Variables |

Laparoscopy (L) (n=21) |

3-D Laproscopy (3D) (n=21) |

p-value |

Laparoscopy (L) (n=41) |

1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA) (n=41) |

p-value |

3-D Laproscopy (3D) (n=11) |

1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA) (n=11) |

p-value |

| EBL, mL (range) |

424.4 (0-1500) |

218.8 (0-1800) |

0.02 |

434.5 (0-2300) |

414.4 (0-3000) |

0.1 |

636.4 (0-3000) |

300 (0-1800) |

1 |

| OR Time, min (range) |

198.3 (50-370) |

206.2 (87-290) |

0.7 |

235.2 (80-540) |

234.7 (36-620) |

0.7 |

211.8 (87-290) |

356.6 (187-620) |

0.002 |

| LOS, days (range) |

5.1 (1-10) |

6.55 (1-11) |

0.09 |

9 (1-168) |

4 (1-13) |

0.07 |

10.8 (5-24) |

5.7 (1-13) |

0.008 |

| Conversion Rate, n (%) |

3 (14.3) |

2 (9.5) |

0.6 |

5 (12.2) |

1 (2.4) |

0.09 |

1 (9.1) |

1 (9.1) |

1 |

| Postoperative Clavien-Dindo morbidity ≥ grade 3, n (%) |

2 (9.5) |

6 (28.6) |

0.1 |

2 (4.9) |

2 (4.9) |

1 |

3 (27.3) |

1 (9.1) |

0.3 |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) |

0 (0) |

3 (23.8) |

0.2 |

0 |

1 (2.4) |

1 |

2 (18.2) |

0 (0) |

0.5 |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) |

0 (0) |

3 (23.8) |

0.2 |

0 |

1 (2.4) |

1 |

2 (18.2) |

0 (0) |

0.5 |

| R1 resection, n (%) |

2 (10) |

0 (0) |

0.5 |

3 (7.3) |

2 (4.9) |

0.6 |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 |

Table 6.

Short term Outcome Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - Inter-national Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Cobotic surgery [3-D Laparoscopy (3D) and 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA)] vs. Robotic surgery [4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4RA)]. EBL = Es-timated Blood Loss, OR = Operating Room, LOS= Length of Stay.

Table 6.

Short term Outcome Variables after propensity score matching, SIMMILR-4 (Study - Inter-national Multicentric Minimally Invasive Liver Resection): Cobotic surgery [3-D Laparoscopy (3D) and 1 Arm Robotic-Assisted (1RA)] vs. Robotic surgery [4 Arm Robotic-Assisted (4RA)]. EBL = Es-timated Blood Loss, OR = Operating Room, LOS= Length of Stay.

| Outcome Variables |

3D (n=13) |

4 RA (n=13) |

p-value |

1 RA (n=9) |

4 RA (n=9) |

p-value |

| EBL, mL (range) |

325 (0-1800) |

283.7 (50-800) |

0.5 |

371.1 (0-1200) |

211.1 (50-900) |

1 |

| OR Time, min (range) |

209 (98-279) |

277.8 (107-314) |

0.01 |

217.9 (60-480) |

235.7 (107-290) |

0.3 |

| LOS, days (range) |

9.4 (5-24) |

5.4 (1-11) |

0.03 |

3.9 (1-8) |

4.2 (1-8) |

0.8 |

| Conversion Rate, n (%) |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Postoperative Clavien-Dindo morbidity≥ grade 3,

n (%)

|

0 |

1 (7.7) |

1 |

0 |

1 (11.1) |

1 |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) |

2 (23.1) |

0 |

0.5 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) |

2 (23.1) |

0 |

0.5 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| R1 resection, n (%) |

0 |

3 (23.1) |

0.2 |

0 |

2 (22.2) |

0.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).