1. Introduction

Ticks are widely distributed across the globe, and tick infestations pose a significant threat to livestock due to their capacity to transmit tick-borne pathogens (TBPs) and cause various diseases. Ticks are considered the second most important vectors of human diseases worldwide after mosquitoes, yet they are the primary vectors of pathogenic diseases in both domestic and wild animals [

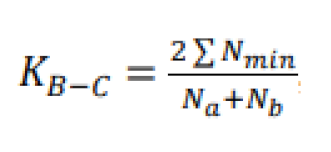

1,

2]. In addition to pathogens, ticks also harbor a diverse array of symbiotic and commensal microorganisms [

3,

4].

Currently, 896 tick species have been recorded worldwide, of which 27 species belong to the genus

Hyalomma [

5,

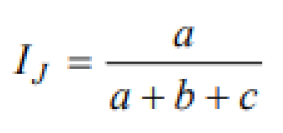

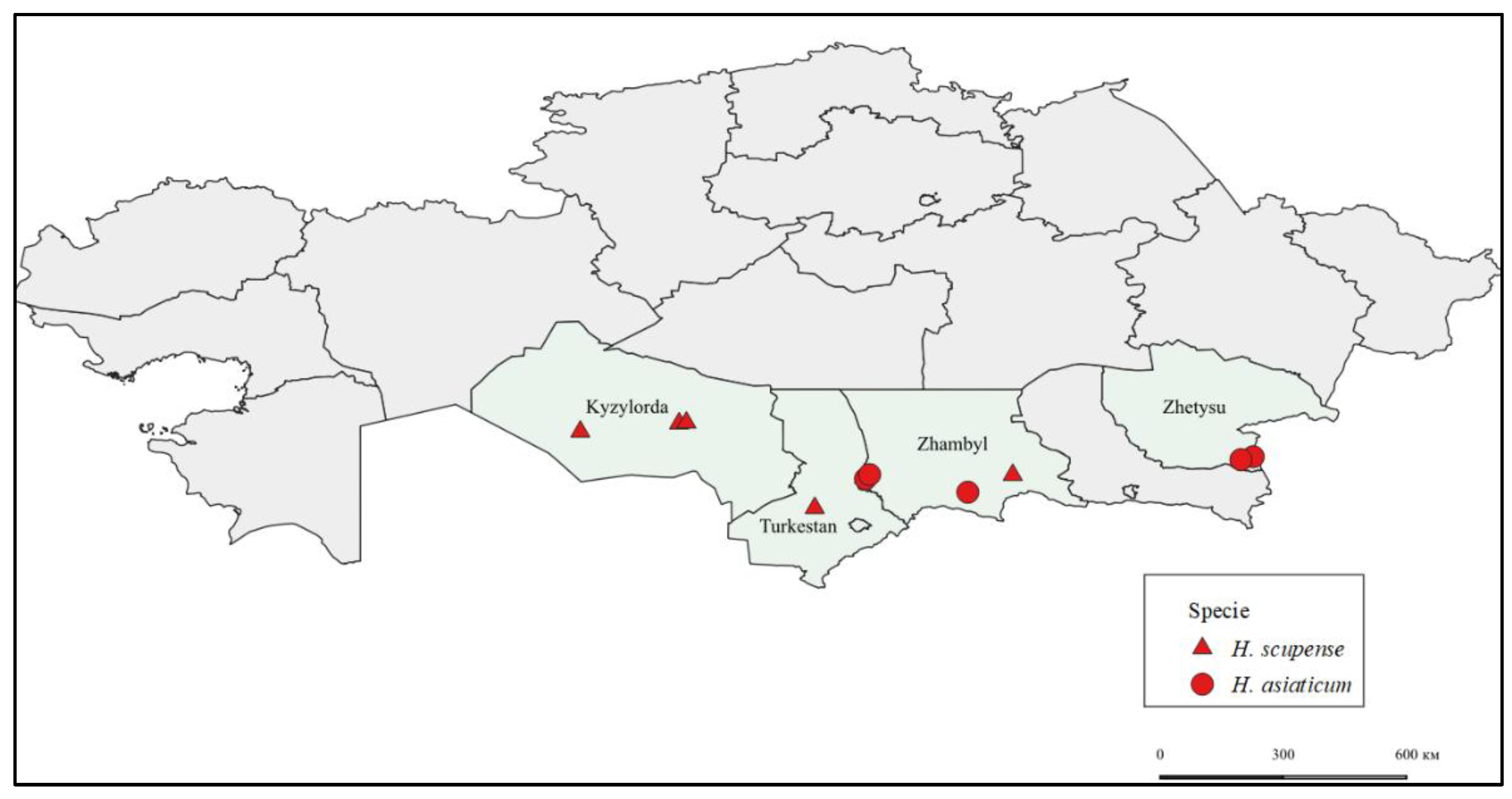

6]. The tick fauna of Kazakhstan comprises over 30 ixodid tick species, including 8 species of the genus

Hyalomma. The natural conditions of Kazakhstan are favorable for the habitation of various tick species, among which

H. scupense and

H. asiaticum are prominent. In the desert landscapes of Kazakhstan,

H. asiaticum predominates, whereas

H. scupense is more common in semi-desert and low-mountain steppe regions. Ticks from the southern region of Kazakhstan are recognized as vectors and reservoirs of multiple pathogens, causing Q fever, tick-borne spotted fevers, arboviruses, and piroplasmoses [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Current data analysis reveals that the metagenomic profile of bacterial communities in H. scupense and H. asiaticum ticks inhabiting the southern and southeastern regions of Kazakhstan remains insufficiently studied.

Furthermore, the potential applications and prospects of metagenomic approaches in the diagnosis and epidemiological surveillance of infectious diseases have not yet been considered. Until recently, most studies focused primarily on the identification of tick-borne pathogens and their epidemiology using traditional methods [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Advancements in metagenomics have fundamentally transformed the ability to characterize the taxonomic composition of microbial ecosystems [

13]. Recent metagenomic projects have revealed that the diversity of life is far greater and more complex than previously imagined through classical methods that rely on visually observable biodiversity [

14,

15,

16,

17].

To date, there are no available data on the microbiome of the most widespread and significant Hyalomma tick species in Kazakhstan. Therefore, our study aims to describe the microbial diversity and richness of the microbiota associated with H. scupense and H. asiaticum ticks. In this research, 16S rRNA metagenomics was employed to investigate bacterial communities in ticks collected from cattle in the southern and southeastern regions of Kazakhstan. The findings of this work may contribute to disease risk assessment for livestock and human populations in these areas and serve as a foundation for developing targeted control strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Tick Sampling

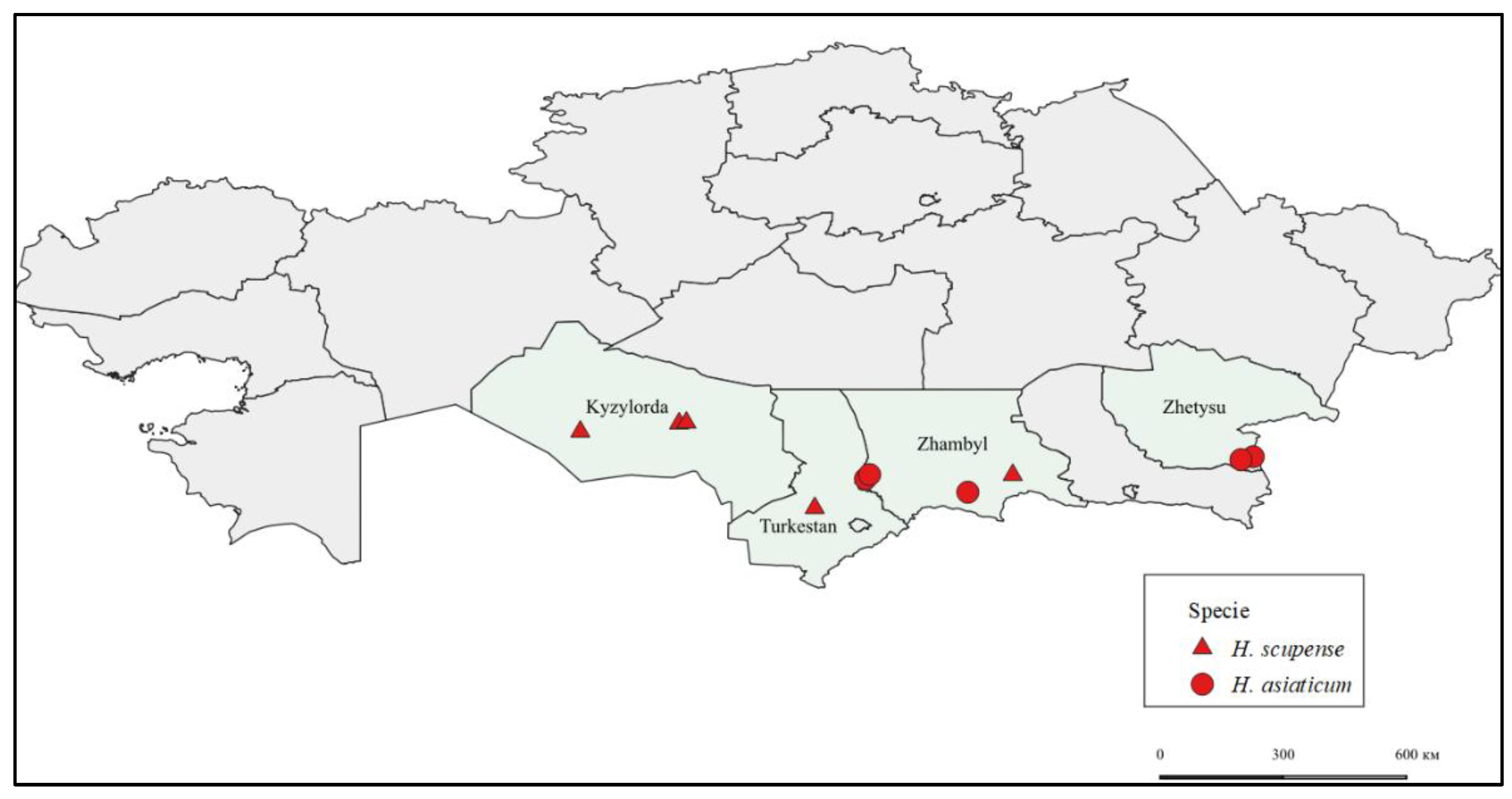

Tick collection was conducted in April - September 2023 in the Kyzylorda, Zhambyl, Turkestan, and Zhetysu regions of Kazakhstan. All ticks were collected from cattle. The collection was performed in accordance with the permit issued by the Committee for Veterinary Control and Supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan and with the consent of the animal owners. During tick collection, personnel adhered to strict safety measures, including wearing protective suits with sealed collars and cuffs, and regularly performing self- and mutual inspections to detect any crawling or attached ticks.

Ticks were removed using blunt forceps from the inner thigh, udder, scrotum, neck, and axillary regions of the animals. Live ticks were placed into plastic tubes with screw caps. To maintain humidity, a leaf of a cereal plant was usually added to each tube. Prior to analysis, ticks were kept alive in a cool place or refrigerated in standard tubes with plant material. Detailed labels were attached to all collected samples. Each arthropod was identified using an Altami PC0745 stereomicroscope (RS0745, Altami, Saint Petersburg, Russia). A total of 1260 ticks were collected. For subsequent microbiome analysis, 94 adult

H. asiaticum and

H. scupense ticks were randomly selected from cattle across various locations in the southern and southeastern regions of Kazakhstan (

Table 1). Female tick samples were pooled in groups of 10 based on location, species, and sex. Two separate pools of male ticks were created, consisting of 6 and 8 individuals respectively. Additional information, including collection sites and tick counts, is provided in

Table 1.

Geographic distribution of

H. scupense and

H. asiaticum ticks visualized using cartographic analysis performed in QGIS software (

Figure 1).

2.2. Molecular-Genetic Identification of Ticks

Tick specimens were initially identified using morphological methods [

18], using an Altami stereomicroscope (RS0745, Altami, Saint Petersburg, Russia). The morphological identifications were subsequently confirmed by molecular genetic analysis targeting the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (COX1) [

19].

A fragment of the COX1 gene (820 bp) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for molecular identification using the following primers: Cox1F: 5’-GGAACAATATATTTAATTTTTGG-3’ and Cox1R: 5’-ATCTATCCCTACTGTAAATATATG-3’. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 minutes; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 54 °C for 45 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 1 minute; with a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 minutes.

PCR products of the COX1 gene were subjected to nucleotide sequencing on an Applied Biosystems 3130 automated DNA sequencer (ABI, 3130, City, State, USA) using the Bigdye Terminator V3.1 loop sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Vilnius, Lithuania) for gene sequencing using an Applied Biosystems 3130 genetic analyzer (HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan).

The obtained nucleotide sequences were analyzed using the Sequencher v. 4.5 program (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The nucleotide sequence was aligned using the Mega 7.0 computer program complex. A set of nucleotide sequences from the international GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) was used to construct a phylogenetic tree. Phylogenetic analysis of the sequences was performed using the Mega 11.0 program.

For the analysis, COX1 gene sequences of ticks obtained from GenBank were used (accession numbers: MW498400, JQ737073, OR533789, NC053941, MN907845, MN821375, MN964348, MN907831, OM743222.

2.3. DNA Extraction

Ticks, previously sterilized with 70% ethanol, were homogenized using a mechanical homogenizer in centrifuge tubes containing 500 µL of chilled sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 1X). The homogenized samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. Total DNA was extracted from the supernatant using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The purity of the extracted DNA was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and DNA samples were stored at −80 °C until further use.

2.4. Library Preparation

DNA concentration from the microbial community was measured using the Qubit™ dsDNA HS (High Sensitivity) Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Library preparation was carried out using the Ion 16S™ Metagenomics Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Briefly, 12 µL of DNA was mixed with 15 µL of Environmental Master Mix. Subsequently, 3 µL of each 10× 16S Primer Set was added: one tube with primers targeting regions V2-4-8 (Pool 1) and another with primers targeting V3-6,7-9 (Pool 2). Samples were subjected to PCR under the following thermal cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes; followed by 25 cycles of 95 °C for 30 seconds, 58 °C for 30 seconds, and 72 °C for 30 seconds; with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 minutes. Amplification products were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CА, USA) and eluted in nuclease-free water. The concentrations of PCR products from Pool 1 and Pool 2 were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and subsequently combined.

End repair was performed by adding 20 µL of 5× End Repair Buffer and 1 µL of End Repair Enzyme to each sample, followed by incubation at room temperature for 20 minutes. The pooled amplicons were purified again using AMPure XP beads and eluted in Low TE buffer. Ligation and nick repair were performed using 10× Ligase Buffer, Ion P1 Adaptor, Ion Xpress™ Barcodes, dNTP Mix, DNA Ligase, Nick Repair Polymerase, nuclease-free water, and sample DNA. The thermal protocol included incubation at 25 °C for 15 minutes followed by 72 °C for 5 minutes. Adapter-ligated and nick-repaired DNA was again purified using AMPure XP beads and eluted in Low TE buffer.

Library amplification was performed using the Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, USA) under the following PCR conditions: 95 °C for 5 minutes; followed by 7 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, 58 °C for 15 seconds, and 70 °C for 1 minute; and a final extension at 70 °C for 1 minute. The amplified library was purified using AMPure XP beads and eluted in Low TE buffer. The optimal library concentration for template preparation was quantified by qPCR on a QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the Ion Universal Library Quantitation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Each library was normalized to a concentration of 30 pM, and equal volumes of each library were pooled for downstream processing.

2.5. Sequencing

Libraries were prepared for sequencing using the Ion Chef Instrument and the Ion 510™ & 520™ & Ion 530™ Kit–Chef (hermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Chips were then loaded onto the Ion GeneStudio S5 System (Ion Torrent platform) (Thermo Fisher Scien-tific, Marsiling Industrial Estate, Woodlands, Singapore) along with Ion S5 Sequencing Kit reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and sequenced at the laboratory. Samples in this study were sequenced on Ion 530 chips using 400bp sequencing size.

2.6. Taxonomic Classification

Taxonomic analysis of the bacterial community was performed by high-throughput sequencing of the hypervariable region V2-4-8 and V3-6,7-9 of the 16S rRNA gene on the Ion Torrent platform using next-generation sequencing technology. The obtained data were taxonomically classified on the platform of The Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Research Center (BV-BRC) using the standard Kraken2 database.

Taxonomic analysis of the bacterial community was performed by high-throughput sequencing of the hypervariable V2-4-8 и V3-6,7-9 regions of the 16S rRNA gene using the Ion Torrent next-generation sequencing platform. The obtained sequences were taxonomically classified on the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC) platform using the standard Kraken2 database.

2.7. Statistical Data Analysis

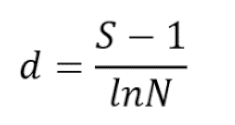

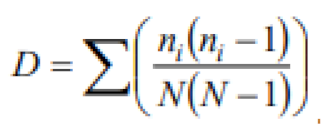

Alpha diversity parameters of microbial communities were assessed by calculating the Shannon-Wiener diversity index [

20], Simpson’s dominance index [

21], and Margalef’s richness index [

22].

Beta diversity analysis to compare the taxonomic composition of the microbiomes of

H. scupense and

H. asiaticum ticks was performed using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index [

23]. To quantify the similarity of bacterial community species composition between

H. scupense and

H. asiaticum, the Jaccard index was applied [

24].

Table 2 presents the formulas used for the quantitative estimation of alpha and beta diversity parameters.

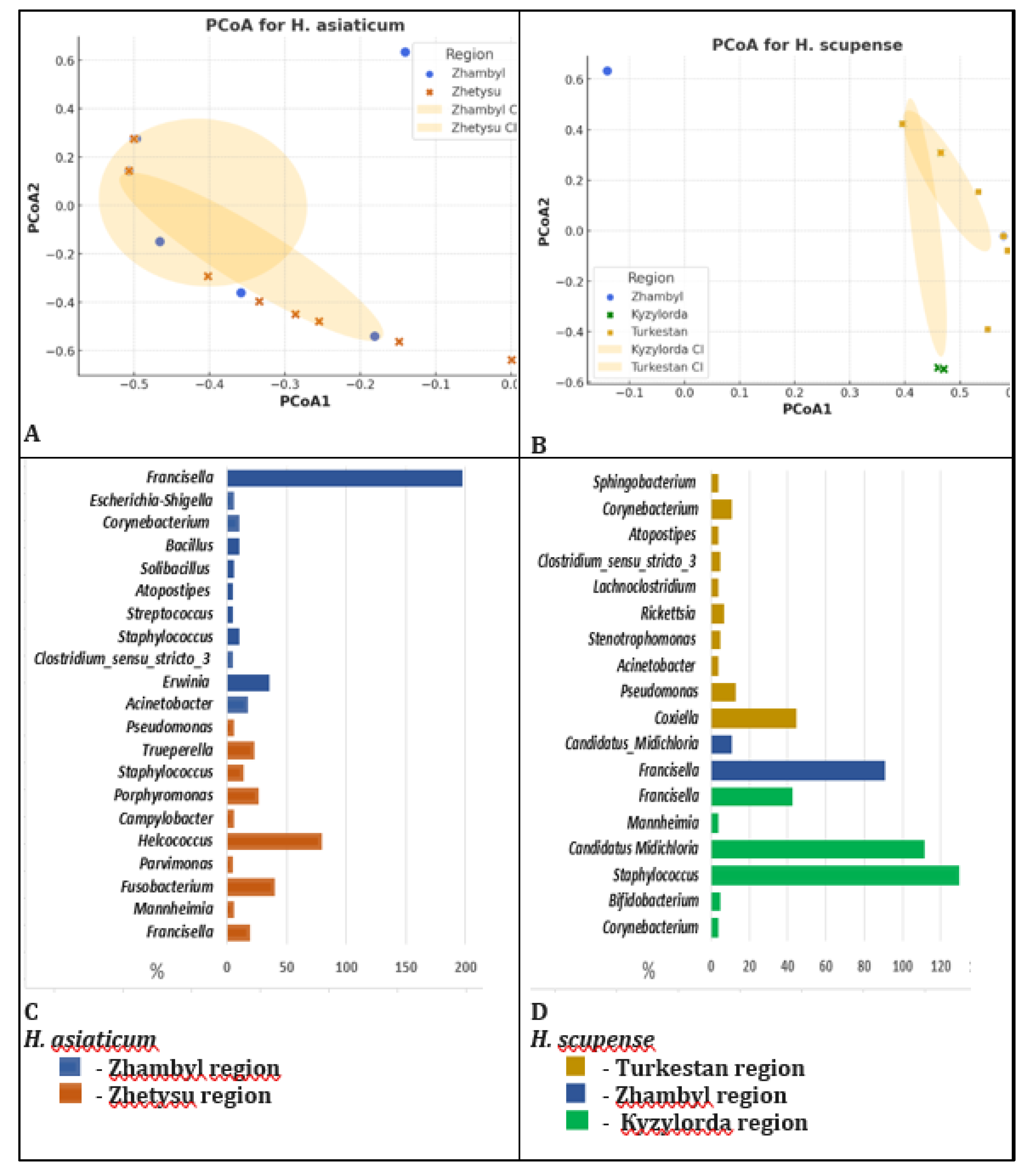

PCoA Diagram Construction. To analyze the geographical distribution of bacteria associated with H. scupense and H. asiaticum, Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was employed. Data visualization was carried out using the Python programming language.

Analysis of Bacterial Composition and Similarity. To assess the similarity of bacterial communities in ticks, the Jaccard similarity index was used. This index reflects the proportion of shared bacterial taxa between sample pairs.

Data visualization was also conducted in Python. Hierarchical clustering analysis was applied to identify natural groupings of bacteria and tick samples based on their microbiome profiles. The clustering method used was agglomerative hierarchical clustering with the nearest neighbor (single linkage) algorithm.

3. Results

3.1. Tick Collection and Identification

Tick samples randomly selected for microbiome analysis were identified to the species level using a combination of morphological and molecular data.

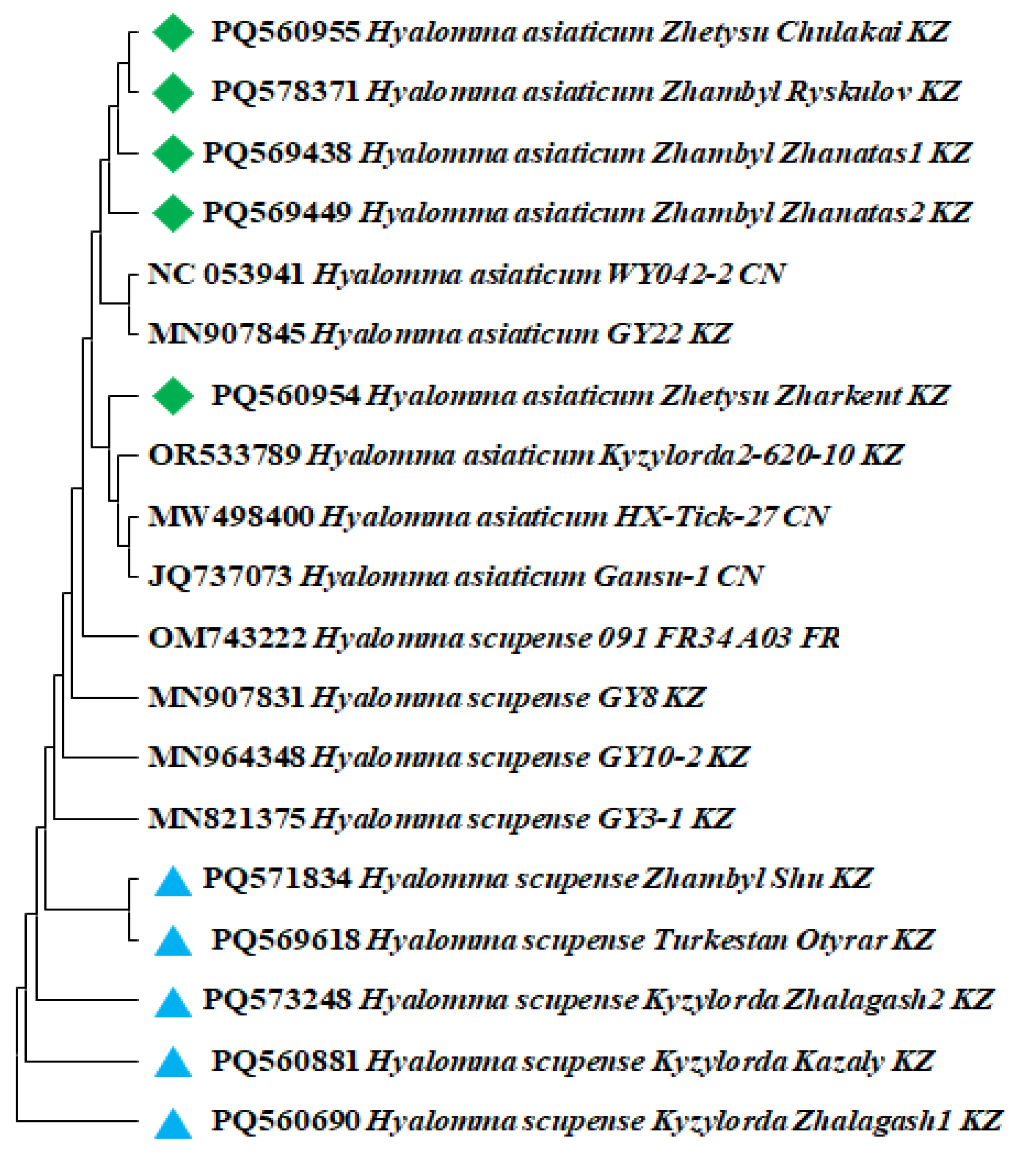

A total of 94 adult ticks, initially morphologically identified and grouped into 10 pools, were subjected to PCR amplification targeting a fragment of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COX1) gene, followed by sequencing of PCR products from positive samples. Phylogenetic analysis of the COX1 gene sequences confirmed the identification of the ticks as H. scupense and H. asiaticum, fully confirming the results of the morphological examination.

The COX1 gene sequences of H. scupense obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: PQ560690 (H. scupense Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_KZ), PQ560881 (H. scupense Kyzylorda_Kazaly_KZ), PQ573248 (H. scupense Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_KZ), PQ569618 (H. scupense Turkestan_Otyrar_KZ), and PQ870262 (H. scupense Zhambyl_Shu_KZ).

The COX1 gene sequences of

H. asiaticum have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers: PQ569438 (

H. asiaticum Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_KZ), PQ569449 (

H. asiaticum Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_KZ), PQ560954 (H

. asiaticum Zhetysu_Zharkent_KZ), PQ560955 (

H. asiaticum Zhetysu_Chulakai_KZ), and PQ578371 (

H. asiaticum Zhambyl_Ryskulov_KZ) (

Figure 2).

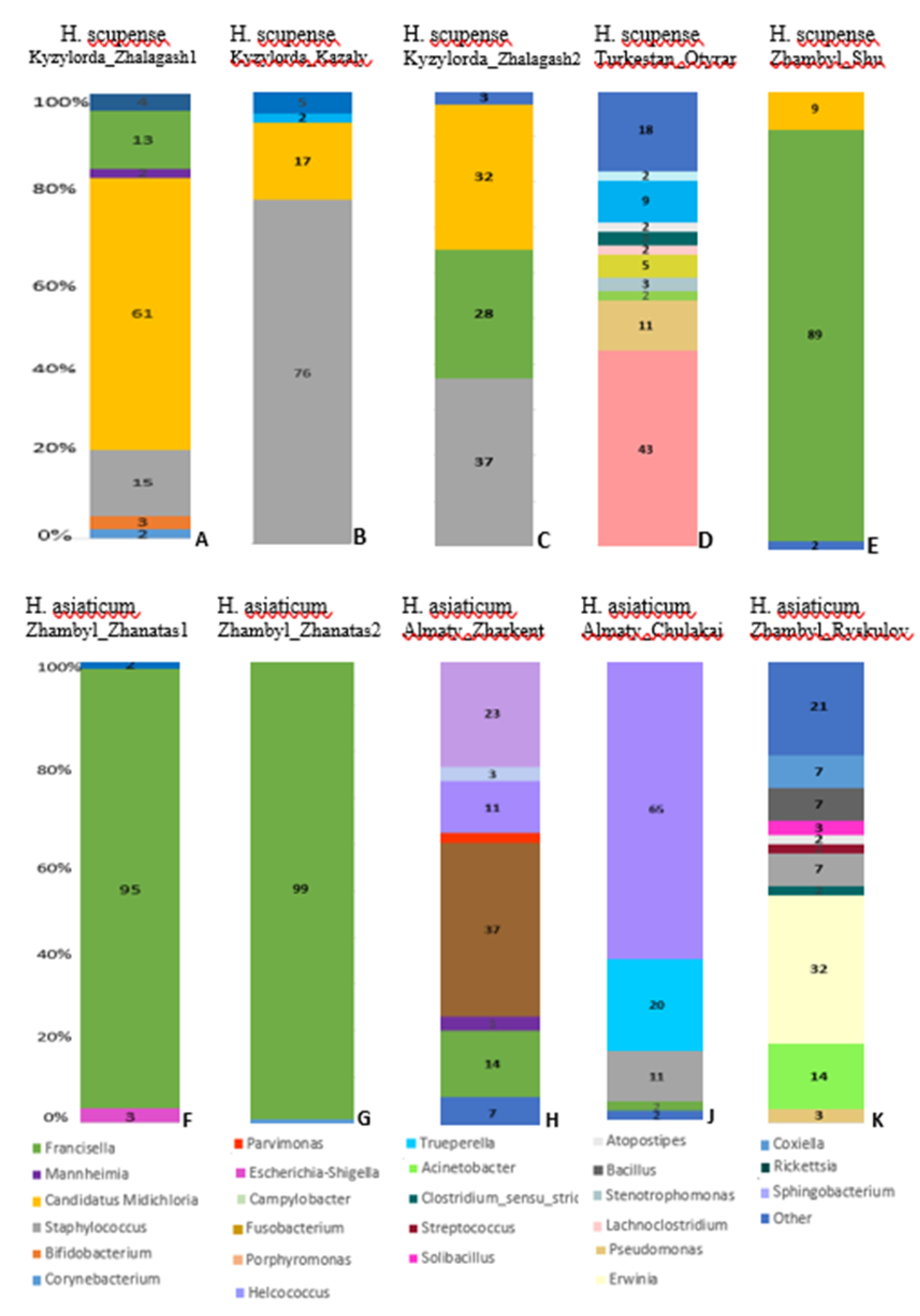

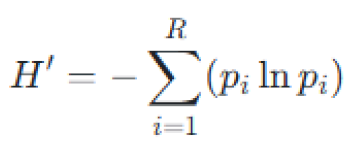

3.2. Assessment of the Bacterial Diversity Profile Based on 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

All 10 tick pools were analyzed for the presence of tick-borne bacterial agents using 16S rRNA gene sequencing data processed on the Ion Torrent next-generation sequencing platform. Metagenomic analysis of

H. scupense ticks revealed the presence of bacterial genera including

Corynebacterium, Bifidobacterium, Staphylococcus, Candidatus Midichloria, Mannheimia, Francisella, Coxiella, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Stenotrophomonas, Rickettsia, Lachnoclostridium, Clostridium sensu stricto 3, Atopostipes, and

Sphingobacterium. In

H. asiaticum ticks, bacterial genera identified included

Escherichia-Shigella, Francisella, Candidatus Midichloria, Mannheimia, Fusobacterium, Parvimonas, Helcococcus, Campylobacter, Porphyromonas, Staphylococcus, Trueperella, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Erwinia, Clostridium sensu stricto 3, Streptococcus, Atopostipes, Solibacillus, Bacillus, and

Corynebacterium (

Figure 3).

At the genus level, the bacterial community composition in H. scupense was dominated by Francisella (89.0%), Staphylococcus (76.0%), and Candidatus Midichloria (61.0%), whereas in H. asiaticum, a higher relative abundance of Francisella (99.0% and 95.0%) and Helcococcus (65.0%) was observed.

The results indicate that the microbiome of Kazakhstani ticks varies in composition and microbial diversity depending on the geographic region.

From a geographic perspective, H. scupense and H. asiaticum ticks collected from the Zhambyl region exhibited significantly higher prevalence of Francisella (99% in Zhambyl_Zhanatas2, 95% in Zhambyl_Zhanatas1, and 89% in Zhambyl_Shu) compared to other locations.

H. scupense ticks from southern regions of Kazakhstan (Turkestan, Zhambyl, and Kyzylorda regions) showed a higher relative abundance of Candidatus Midichloria (61% in Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1), whereas this microorganism was not detected in H. asiaticum or H. scupense from the Zhetysu region.

H. scupense from the Turkestan region exhibited elevated relative abundances of several bacterial genera, including

Coxiella (43.0%),

Pseudomonas (11.0%),

Acinetobacter (2.0%),

Stenotrophomonas (3.0%),

Rickettsia (5.0%),

Lachnoclostridium (2.0%),

Clostridium sensu stricto 3 (3.0%),

Atopostipes (2.0%),

Corynebacterium (9.0%), and

Sphingobacterium (2.0%) (

Figure 3D).

H. asiaticum from the Zhambyl region harbored more abundant bacterial genera such as

Pseudomonas (3.0%),

Acinetobacter (14.0%),

Erwinia (32.0%),

Clostridium sensu stricto 3 (2.0%),

Staphylococcus (7.0%),

Streptococcus (2.0%),

Atopostipes (2.0%),

Solibacillus (3.0%),

Bacillus (7.0%), and

Corynebacterium (7.0%) (

Figure 3K).

The endosymbiont

Francisella constituted a significantly dominant proportion of the microbiome in male

H. scupense ticks (89.0%,

Figure 3E) compared to females (13.0%,

Figure 3A; 28%,

Figure 3C; and 2%,

Figure 3D).

Similarly,

Helcococcus comprised a significantly dominant percentage of the microbiome in male

H. asiaticum ticks (65.0%,

Figure 3J) compared to females (11.0%,

Figure 3H).

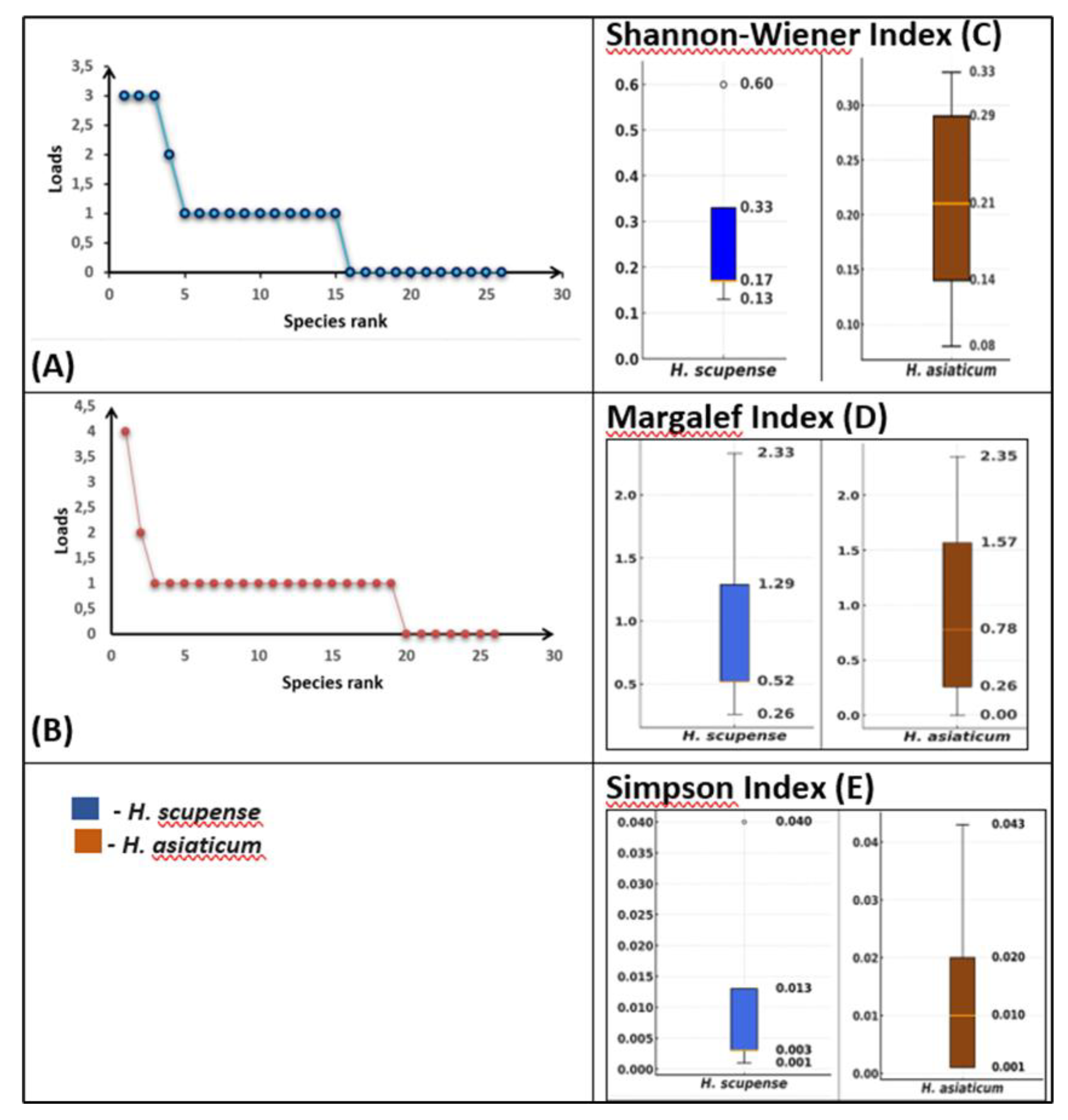

3.3. Bacterial Microbiome Diversity in H. scupense and H. asiaticum

Alpha diversity of bacterial communities associated with

H. scupense and

H. asiaticum ticks is determined by the Shannon-Wiener, Margalef, and Simpson indices (

Figure 4).

The bacterial abundance distribution curves for

H. scupense (

Figure 4A) and

H. asiaticum (

Figure 4B) show that a small number of bacterial genera (top ranks) carry the greatest abundance, while the majority of taxa occur at lower abundance levels. The broken shape of the curve suggests the presence of dominant bacteria with a gradual decline in abundance among other taxa. Notably,

H. asiaticum demonstrates a more pronounced dominance of a single bacterial genus, whereas

H. scupense exhibits a more even distribution among several top-ranked genera.

Shannon-Wiener index (

Figure 4 C): the median for

H. scupense was 0.17 (interquartile ranges (IQR) 0.17 - 0.33), for

H. asiaticum - 0.21 (IQR 0.14 - 0.29), which reflects the high uniformity of communities in

H. asiaticum.

Margalef index (

Figure 4 D): for

H. scupense the median is 0.52 (IQR 0.52 - 1.29),

for H. asiaticum the median is - 0.78 (IQR 0.26 - 1.57), which indicates species richness in

H. asiaticum.

Simpson index (

Figure 4 E): median values were 0.003 (IQR 0.003 - 0.013) for

H. scupense and 0.010 (IQR 0.001 - 0.020) for

H. asiaticum, confirming the high diversity in

H. asiaticum.

3.4. Microbial Variations Depending on Geographic Origin

We constructed distribution diagrams and cladograms of microbial communities, demonstrating differences in the bacterial composition of H. scupense and H. asiaticum ticks according to their geographic origin. To assess differences in bacterial communities between regions, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed. Coordinates were calculated based on the Bray-Curtis distance matrix.

The microbiome of H. asiaticum showed no significant differences between regions (p-value = 0.299, p > 0.05, ANOVA test), suggesting a similar bacterial composition across different locations. This indicates that H. asiaticum harbors a relatively stable microbiota independent of geographic location.

For H. scupense, differences between regions were statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.023 (p < 0.05) according to the ANOVA test. The microbiome of H. scupense significantly varies among regions, which is supported by the visual analysis of the PCoA plot.

A statistically significant difference in bacterial composition was observed between the Kyzylorda and Zhetysu regions for

H. scupense (p = 0.016). This may indicate that environmental or host-related factors differ between these regions. For example, the climate in the Kyzylorda region is more arid and located further south, whereas the Zhetysu region is more humid and situated to the east, potentially leading to distinct microbial community structures (

Figure 5).

3.5. Beta diversity of the Bacterial Community in the Microbiome of H. scupense and H. asiaticum Ticks

The Jaccard index was used to assess the similarity in bacterial community composition between H. scupense and H. asiaticum, reflecting the proportion of shared bacterial taxa between sample pairs.

Hierarchical clustering analysis was applied to identify natural groups of bacteria within the tick microbiomes (

Figure 6).

Light yellow shades correspond to low similarity (Jaccard index ≤ 0.50), while dark green shades indicate high similarity (Jaccard index > 0.50). The heatmap was generated using the Python environnt. The clustering method applied was agglomerative nearest neighbor clustering.

The constructed heatmap with hierarchical clustering revealed patterns in the distribution of bacterial composition among ticks. Statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.001, t-test) indicate that bacterial communities of different tick species form distinguishable clusters.

Some bacterial genera, such as Mannheimia, Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Clostridium sensu stricto 3, and Atopostipes, are present in both samples with equal proportions (0.5), indicating partial overlap in bacterial composition. The genera Corynebacterium (0.75 and 0.25) and Francisella (0.43 and 0.57) occur in both samples but at different frequencies. The similarity level of bacterial communities between H. scupense and H. asiaticum ticks based on the Jaccard index is only 30.8%, with only 8 shared bacterial genera identified.

Certain bacteria, including Coxiella, Candidatus Midichloria, Stenotrophomonas, Rickettsia, Lachnoclostridium, Sphingobacterium, and Bifidobacterium, are found exclusively in H. scupense, indicating a species-specific bacterial composition. Conversely, genera such as Fusobacterium, Escherichia-Shigella, Parvimonas, Helcococcus, Campylobacter, Porphyromonas, Trueperella, Erwinia, Streptococcus, Solibacillus, and Bacillus are unique to H. asiaticum, reflecting bacterial diversity specific to this tick species.

Thus, the analysis demonstrates that the bacterial communities of the two tick species comprise both shared and unique taxa, suggesting differences in their ecology or potential interactions with pathogens.

4. Discussion

Tick-borne pathogens remain poorly understood, despite their important medical and veterinary significance. In many countries, including Kazakhstan and neighboring regions of Central Asia, data on the composition and distribution of microorganisms associated with ticks of the genus Hyalomma are extremely limited. This creates significant gaps in understanding the epidemiological role of the most common tick species of the genus Hyalomma. The lack of systematic studies prevents the identification of the spectrum of pathogens circulating in natural foci and does not allow a full assessment of their potential impact on human and animal health.

According to the scientific literature, a number of studies of microbial populations in ticks of the genera

Ixodes, Rhipicephalus, Haemaphysalis, Dermacentor and

Amblyomma have been conducted to date. [

25,

26,

27].

In Kazakhstan, there is very little data on the composition of microbial communities in the most common species - H. scupense and H. asiaticum. Studying their microbiota and symbionts is important for understanding the bacterial communities of ticks. Such research can help to elucidate their ability to transmit pathogens to vertebrate hosts.

Next generation sequencing of the V2-4-8 and V3-6,7-9 variable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was performed using H. scupense and H. asiaticum samples using the Ion Torrent platform.

We found that the most dominant group in H. scupense were Francisella (89.0%), Staphylococcus (76.0%) and Candidatus Midichloria (61.0%). And in H. аsiaticum, the most dominant bacteria were Francisella (99.0% and 95.0%), Helcococcus (65.0%).

In the bacterial microbiota of Kazakhstan ticks

H. scupense and

H. asiaticum, the symbiotic/pathogenic bacterium

Francisella predominates in the microbiome. According to literature data,

Francisella predominates in the microbiome of

H. excavatum and

H. marginatum [

28].

Recent studies confirm the widespread distribution of

Francisella in other representatives of the genus

Hyalomma. Francisella-like endosymbionts are transmitted vertically [

29] and constitute the main components of the

Hyalomma microbiome worldwide [

17]. Thus, they have been identified in

H. anatolicum in Pakistan

, H. lusitanicum in Spain,

H. aegyptium in Turkey,

H. dromedarii in the Middle East, and also in

H. asiaticum in China. [

30,

31,

32,

33].

These results demonstrate that the

Francisella symbiont/pathogen plays a key role in shaping the microbial communities of

Hyalomma ticks and likely has a significant impact on its vector competence. Bacterial endosymbionts may influence tick physiology and reproductive capacity, as well as the ability of ticks to transmit transmitted pathogens, and finally may interact with tick hosts, which may have veterinary and zoonotic implications, in particular for

Francisella and

Rickettsia bacteria [

34].

Staphylococcus and

Helcococcus were the most common pathogens in

H. scupense and

H. asiaticum, respectively, indicating the possible presence of these microorganisms in animal populations parasitized by these tick species.

Identification of

Helcococcus spp. is challenging due to the slow growth of these organisms [

35]. In our study,

Helcococcus was identified using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Members of the genus

Helcococcus are known to cause mastitis and urocystitis in animals [

36]. Different species of

Staphylococci vary in their virulence, which determines different levels of health threat.

Staphylococcus probably enters the tick's body from the environment and persists throughout its life cycle [

37].

Their exact role is still unknown, but pathogenic species such as

Staphylococcus lentus and

Staphylococcus saprophyticus, which were previously found in

Hyalomma ticks [ 38], may be the reason why staphylococci are frequently detected in these ticks. In our study, Staphylococcus accounted for 7.0% of the microbiota in

H. asiaticum and 76% in

H. scupense, confirming the prevalence of this genus of bacteria in these tick species.

Candidatus Midichloria mitochondrii is a widespread endosymbiont of ticks [

39]. This bacterium plays a critical role in the growth and development of the host, providing it with additional sources of ATP and B vitamins, which contributes to an increase in the adaptive capabilities and general biology of ticks [

40]. Previously,

Candidatus Midichloria mitochondrii was detected in

H. anatolicum in Xinjiang, China [

41]. In our study, this endosymbiont was detected only in

H. scupense.

Blood feeding is known to have a strong impact on tick microbial diversity, composition, and species richness [

42]. Ticks acquire more microorganisms, including pathogens, from hosts during blood feeding. More diverse and larger numbers of vertebrate hosts result in a more diverse microbiota [

43].

Comparative analysis of the microbial communities associated with H. scupense and H. asiaticum revealed significant differences in their bacterial composition. A total of 15 bacterial genera were identified in H. scupense, while 19 genera were identified in H. asiaticum. Eight genera of Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, Mannheimia, Francisella, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Clostridium sensu stricto 3, and Atopostipes (30.8%) were common to both species, forming a conserved component of the microbiota. At the same time, 69.2% of the bacterial composition is accounted for by species-specific taxa: 7 unique genera in H. scupense (26.9% of the total), including Bifidobacterium, Candidatus Midichloria, Coxiella, Stenotrophomonas, Rickettsia, Lachnoclostridium, and Sphingobacterium and 11 unique genera in H. asiaticum (42.3%), including Escherichia-Shigella, Fusobacterium, Parvimonas, Helcococcus, Campylobacter, Porphyromonas, Trueperella, Erwinia, Streptococcus, Solibacillus, and Bacillus.

Despite the presence of a common bacterial base, a significant proportion of the bacterial composition differs between

H. scupense and

H. asiaticum. The data obtained highlight both the species-specificity of microbial associations and the potential influence of environmental [

44,

45], geographic [

46] and other factors on the formation of microbial communities in ticks.

Our study revealed a difference in the microbiota composition between the sexes of H. scupense and H. asiaticum ticks. In male H. scupense, a higher prevalence of the endosymbiont Francisella was found, which constituted the dominant part of the microbiome - 89% in samples from Zhambyl_Shu. At the same time, in females, the proportion of Francisella was significantly lower: 13% - Kyzylorda_Zhalagash 1, 28% Kyzylorda_Zhalagash 2 and only 2% - Turkestan_Otyrar. This difference may indicate sexual characteristics in the formation of microbial communities and the role of endosymbionts in H. scupense, which requires further study.

H. asiaticum exhibits significant sex differences in the microbiota composition. In males from the Zhetysu_Chulakai region, the proportion of

Helcococcus was 65%, while in females from Zhetysu_Zharkent it was only 11%. This indicates a potential sex specificity in the formation of the bacterial community. According to the literature

, Helcococcus was not so widely detected in

H. truncatum collected from cattle; it was present with a relative frequency of about 4.7% [

47].

Males and females may have different contacts with the host, habitat, and food, which may determine differences in the microbiota, including the predominance of Helcococcus in males.

Our results expand our understanding of the biodiversity and microbiota ecology of Hyalomma in Central Asia and highlight the need for further research to understand the contribution of endosymbionts and pathogens to the vector competence of these ticks. These results are particularly important for Central Asian countries, where Hyalomma ticks are widespread and play an important role in the transmission of zoonotic infections. The lack of data on the microbiota of local tick populations hinders understanding of epidemiological risks in the region. Our results fill this gap and provide a basis for the development of preventive and diagnostic strategies aimed at reducing the threat to human and animal health in Kazakhstan and neighboring Central Asian countries.

- Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Kazaly_H. scupense, Zhambyl_Shu_H. scupense, Turkestan_Otyrar_H. scupense.

- Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Kazaly_H. scupense, Zhambyl_Shu_H. scupense, Turkestan_Otyrar_H. scupense.  - Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Ryskulov_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Zharkent_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Chulakai_H. asiaticum

- Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Ryskulov_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Zharkent_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Chulakai_H. asiaticum

- Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Kazaly_H. scupense, Zhambyl_Shu_H. scupense, Turkestan_Otyrar_H. scupense.

- Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Kazaly_H. scupense, Zhambyl_Shu_H. scupense, Turkestan_Otyrar_H. scupense.  - Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Ryskulov_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Zharkent_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Chulakai_H. asiaticum

- Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Ryskulov_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Zharkent_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Chulakai_H. asiaticum

- Hyalomma scupense identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

- Hyalomma scupense identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.  - Hyalomma asiaticum identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

- Hyalomma asiaticum identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

- Hyalomma scupense identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

- Hyalomma scupense identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.  - Hyalomma asiaticum identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

- Hyalomma asiaticum identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.