1. Introduction

The escalating number of drug overdose deaths, especially with involvement of synthetic opioids and polydrug use, has become a significant public health issue in the United States. As the rates of death continue rise with efforts of treatments/interventions and awareness, it becomes imperative to understand the patterns, risk factors, and the geographic distribution of drug overdose fatalities. Data mining can be an effective mechanism to get insights into complex multi-dimensional data sets. This action research adopted a secondary data set called "Accidental_Drug_Related_Deaths.csv" with 11,981 records and 48 features that documented accidental drug-related fatalities regarding demographic, geographic, and substance use. After a comprehensive data preprocessing step (cleaning, transforming, and reducing), the data set was analyzed using various data mining techniques including association rule mining, classification, clustering, and outlier detection so that risk demographic, combinations of drugs used, overdose locations, and cases of anomaly (outliers) could be identified. The data from the action research does not only provide a data use tool for health professions, government officials, and law enforcement, it will gain insight regarding ethical considerations such as data privacy and mitigating bias in public health, and further knowledge on severe overdose cases which require evidence-based steps taken to intervene [

1,

2,

3].

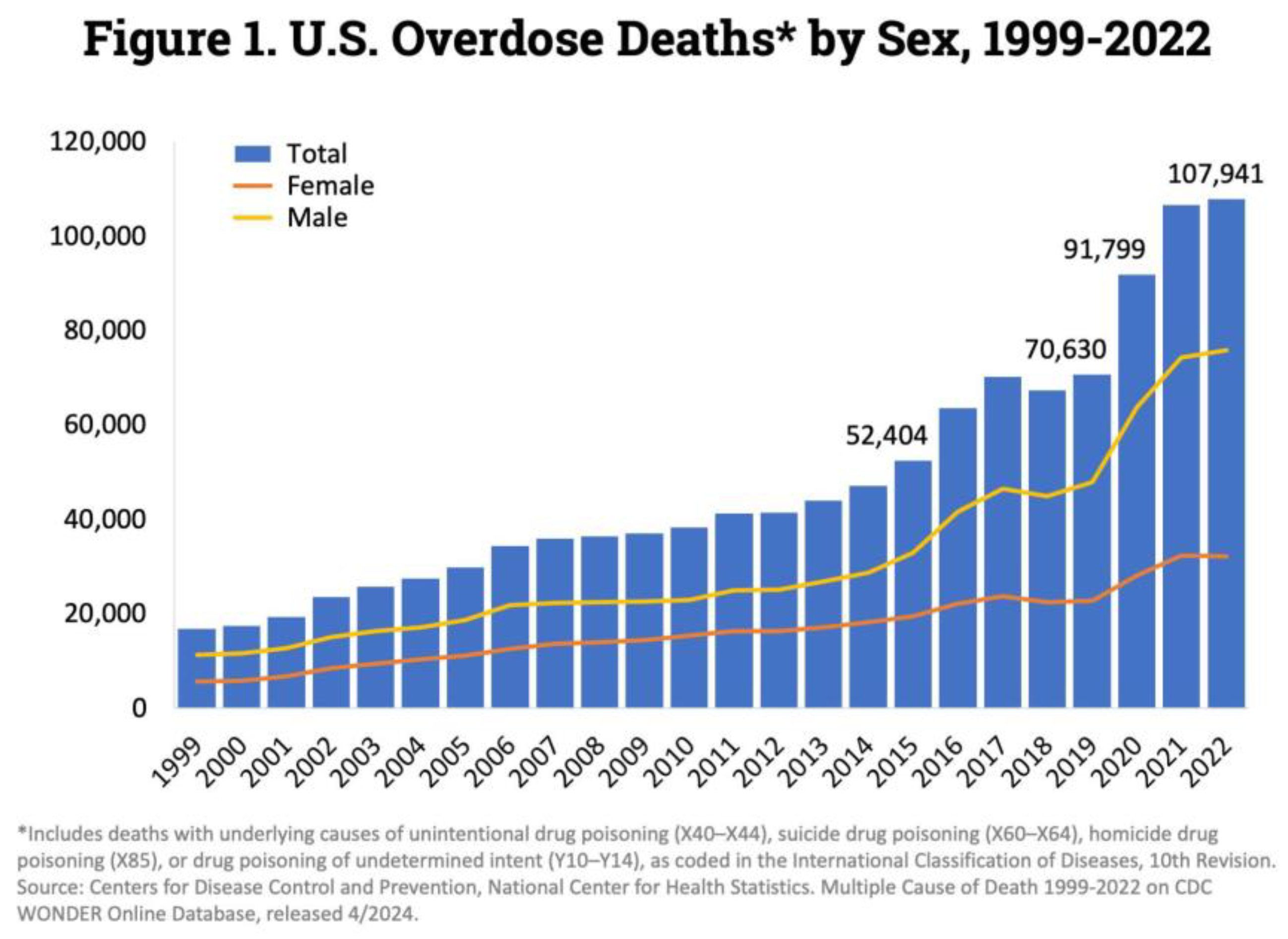

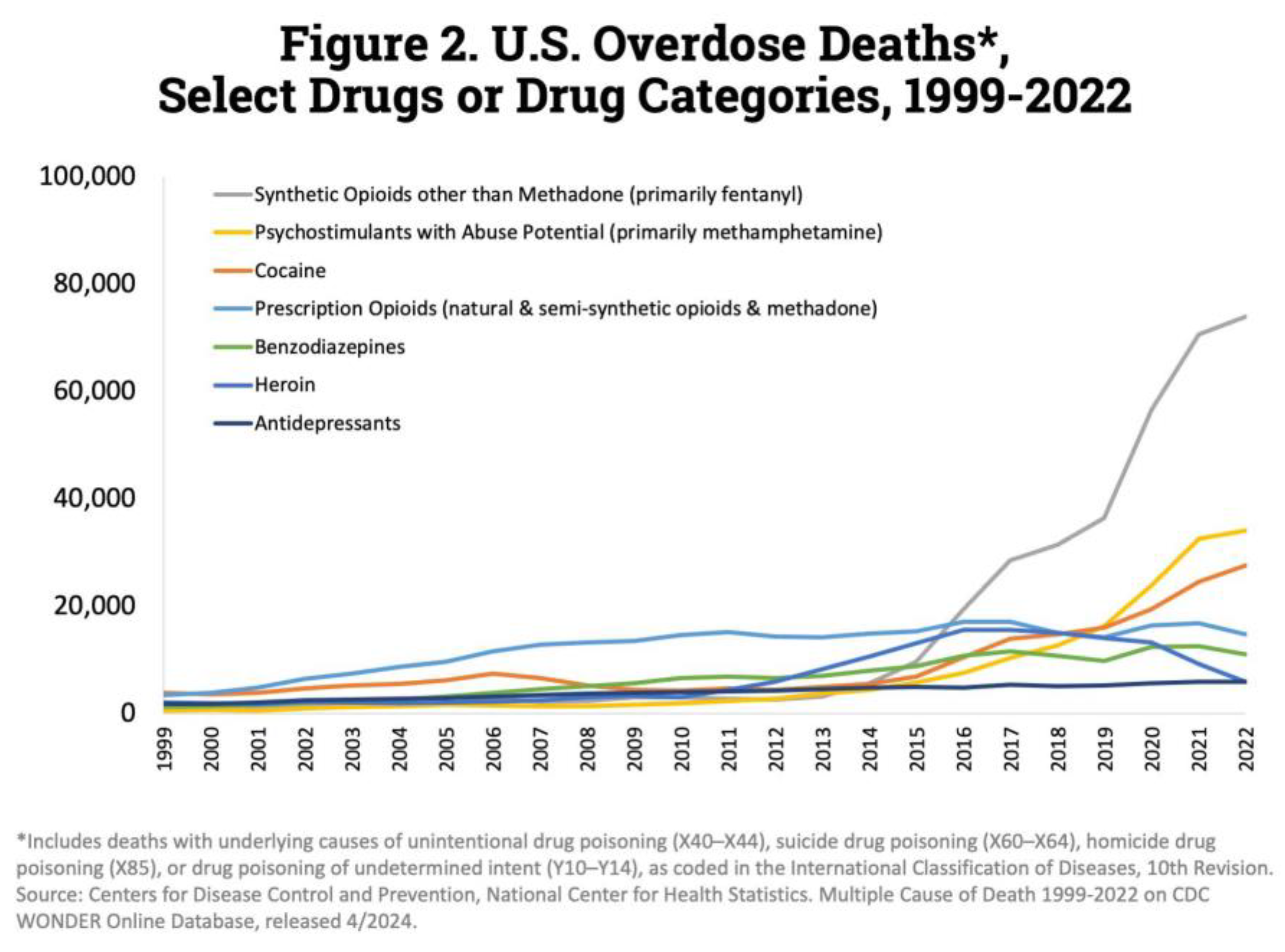

Drug overdose and abuse, especially among opioids and synthetic drugs, have become a substantial public health emergency in the United States. Between 1999 and 2022, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (2024) illustrated that overdose deaths have spiked, with synthetic opioids such as fentanyl being heavily implicated. In order to identify recurring patterns in such data-rich contexts, data mining is becoming more relevant as it enables data scientists and analysts to visualize patterns that would not be identified through traditional, statistical data analysis [

4,

5,

6]

There are many overdose studies that have adopted data mining approaches. For example, [

7], performed association rule mining, identified co-occurrence patterns between two types of drugs (opioids and benzodiazepines), and determined that the presence of benzodiazepines lead to increased fatality rates when using opioids. [

8], conducted clustering analyses to geographically cluster overdose cases; results indicated clusters were located in underserved urban areas. [

9], used classification methods, such as decision trees and logistic regression, to predict opioid drug overdose risk based on demographic and drug use activity information [

7,

8].

Preprocessing is a fundamental part of data mining due to noise, missing values, and varying formats addressed in health-related datasets. This study describes the use of techniques, such as imputation, transformation, and reduction, to prepare for reliable analyses. Ethical considerations have also been discussed in two new publications [

10,

11,

12], relating to the privacy of data, minimizing bias, and ensuring transparency with sensitive personal information and public health issues. The existing literature supports the use of data mining for drug-related overdoses, particularly when used after strict preprocessing measures and ethics evaluations are applied [

13,

14,

15]. This study supports this claim by providing the full end-to-end preprocessing pipeline and analyzing the Accidental_Drug_Related_Deaths.csv dataset using various mining techniques through this set of methods to assist health decision-makers and emergency managers in providing data-informed solutions to public health concerns [

16,

17,

18].

7. Recognizing Common Locations for Overdoses

The last goal is to examine where overdose deaths typically occur; it could be at a home, a workplace, a hotel, a park, or a different location. Identifying where overdoses often occur will reveal important behavioral/situational characteristics and typologies associated with substance abuse and inform targeted location-specific prevention efforts. For example, if most overdoses occur in private homes, prevention programming and intervention could be directed toward households. If many overdoses occur in public spaces like hotels and cars, perhaps an increased level of monitoring or providing emergency kits would be appropriate. Recognizing patterns allows us to better understand the context of overdose deaths and in turn can help improve the design of preventive strategies and emergency responses.

7.1. Methodology

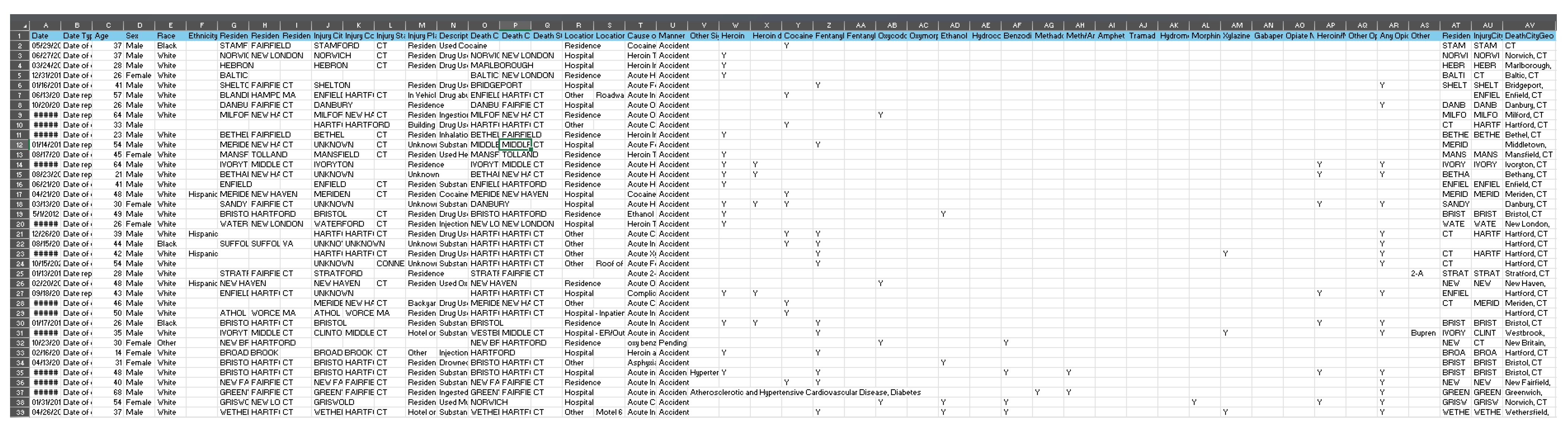

This research uses a holistic data mining approach to analyze the Accidental_Drug_Related_Deaths.csv with 11,981 records and 48 attributes. The approach has four major stages, each intended to achieve particular objectives of the study as follows: data preprocessing; data transformation/reduction; application of various data mining procedures and, visualization and interpretation. Data mining could specifically reveal frequent drug combinations, high risk demographic groups, anomalies in drug overdoses and, geospatial trends associated with overdoses.

7.2. Data Preprocessing

Data preprocessing was a vital step because the dataset included numerous missing, incorrect, inconsistent, and redundant values. The first step when dealing with the data quality issues was to process the missing values either through imputation, if the missingness is determined to be at random, or just removing them altogether and ignoring the rows/columns, based on missing value prevalence and how important the data was. Imputations were done with common approach. Missing values in numerical fields like the Age field were imputed with the mean value of that field. Missing values in categorical fields such as Sex were filled with the mode. The decision was made to remove some columns that had a significant enough amount of missing data, such as Ethnicity and the Heroin death certificate data with check boxes, because this would not affect the quality of the dataset. The categorical variables were standardized to remove data entry or spelling mistakes; as an example, (CT) and (Connecticut) for the state data were standardized to one of these values. The values in each categorical column in this study, including Race, Injury Place, and Description of Injury were categorized and used standardized grouping categories for improved inferential, explanatory or causal modeling objectives as well as interpretability of model outputs. Lastly, when there are missing and even vague data points with geolocation fields, whether by geographic coordinates, the researcher completed them or simply deleted the row if there was no way to correct the spatial determination. Finally, columns that were redundant such as Unnamed: 48, Location if Other, and Cause of Death; these columns clutter the dataset and noise from many missing values, so those values were edited until fully resolved and noted.

7.3. Data Transformation and Encoding

During the transformation stage, categorical variables were transformed into numerical representation to be compatible with machine learning algorithms. Similar variables were merged into one column. For instance Any Opioid and Other Opioid were combined into a new variable called Any Other Opioid when conducting analysis. Geolocation columns were specified in the original data set as ResidenceCityGeo, InjuryCityGeo and DeathCityGeo, either needing to be edited into multiple columns indicating the city, state, latitude and longitude, respectively for a more efficient spatial analysis. There were enhancements made to the data where it was formatted, such as personal checks of data for capitalization; for example, scrubbing variable names so that the origin city state names were consistent. Enhancements were made to textual data and with these last improvements the project dataset was primed for analysis.

7.4. Data Mining Techniques

The study used various data mining approaches to meet the analytical objectives of this study. For example, association rule mining was conducted in the form of two data mining algorithms (Apriori and FP-Growth), with respect to the goal of discovering commonly co-occurring substances in overdose cases. Such algorithms, for example, help uncover important combinations of substances related to overdoses, e.g. heroin and fentanyl usually show up together. Classification methods (decision trees, logistic regression and random forests) - were used to classify people into either high- or low-risk based on age categories, gender and race. Clustering approaches (K-Means, Hierarchical Clustering and DBSCAN) were used to find demographically based groupings and high-risk geospatial clusters. Finally, methods for outlier detection (Isolation Forest, Z-score, DBSCAN and Local Outlier Detection - LOF) were used to look for qualitatively odd occurrences, including young or elderly victims, or deaths that occurred at inadvisable locations.

7.5. Visualization and Interpretation

To assist in the interpretation of the data, many visualizations were prepared following the analysis using Python libraries such as Matplotlib and Seaborn. These included histograms we used to explore the distributions of age, commonly used substances and locations of death, barred charts to gauge the distributions of substance use, heatmaps to illustrate correlations between substances and geographic clusters of overdose deaths, and pie charts for race and ethnicity distributions after pre-processing. The visualizations expanded the clarity of our findings and improved accessibility for both policymakers and public health practitioners.

Figure 12.

rows, the percentage of missing values is negligible. These were imputed with the mean, and then rounded to the closest whole number, as Age is most often reported in whole years. I confirmed the validity of the imputation by checking the historically missing rows.

Figure 12.

rows, the percentage of missing values is negligible. These were imputed with the mean, and then rounded to the closest whole number, as Age is most often reported in whole years. I confirmed the validity of the imputation by checking the historically missing rows.

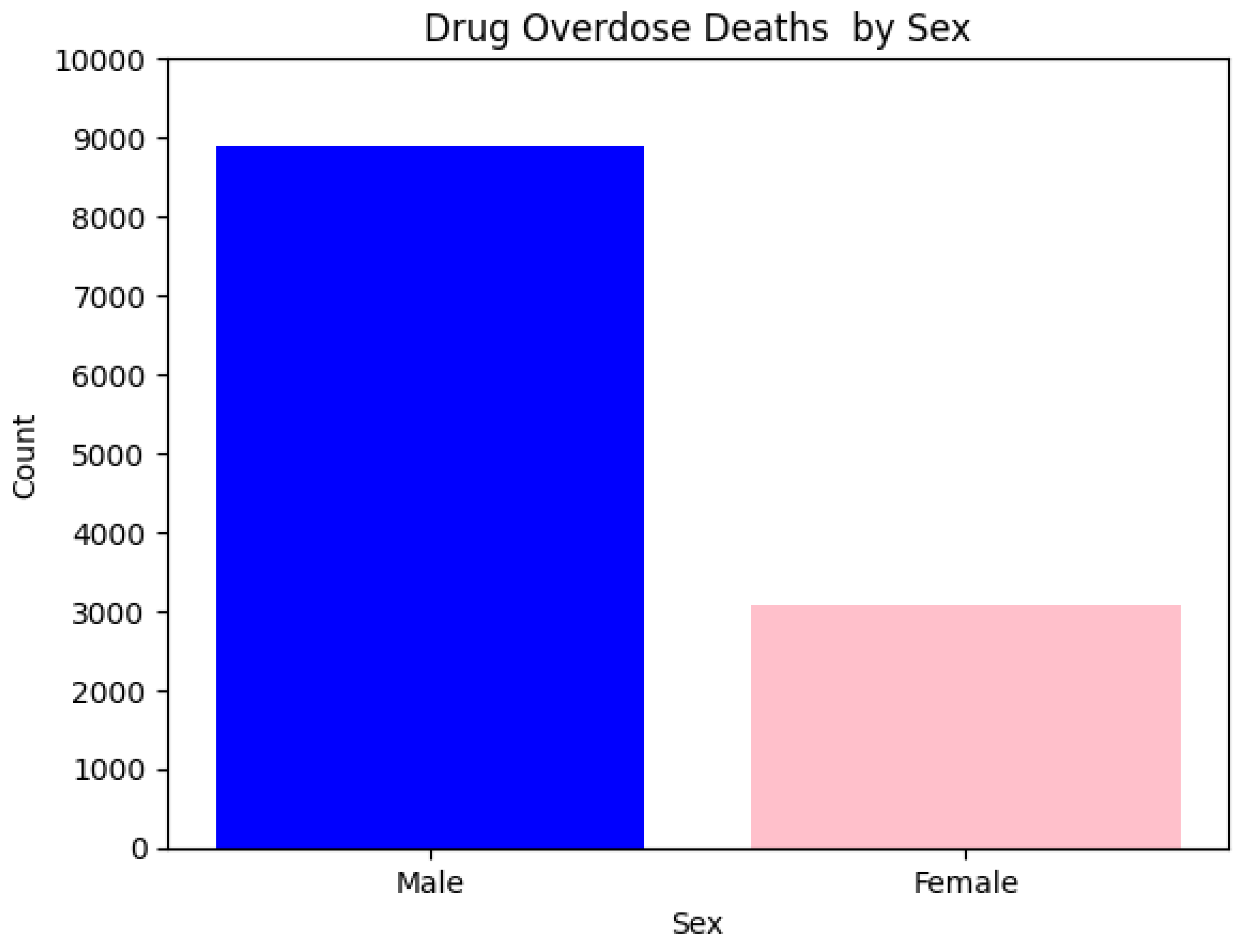

The Sex column had 12 missing or ambiguous values (for example, "X" or "Unknown"). These were imputed also with the mode, which was "Male." Since there were 8887 males and 3082 females in the dataset, the 12 missing values were inconsequential, in terms of distribution.

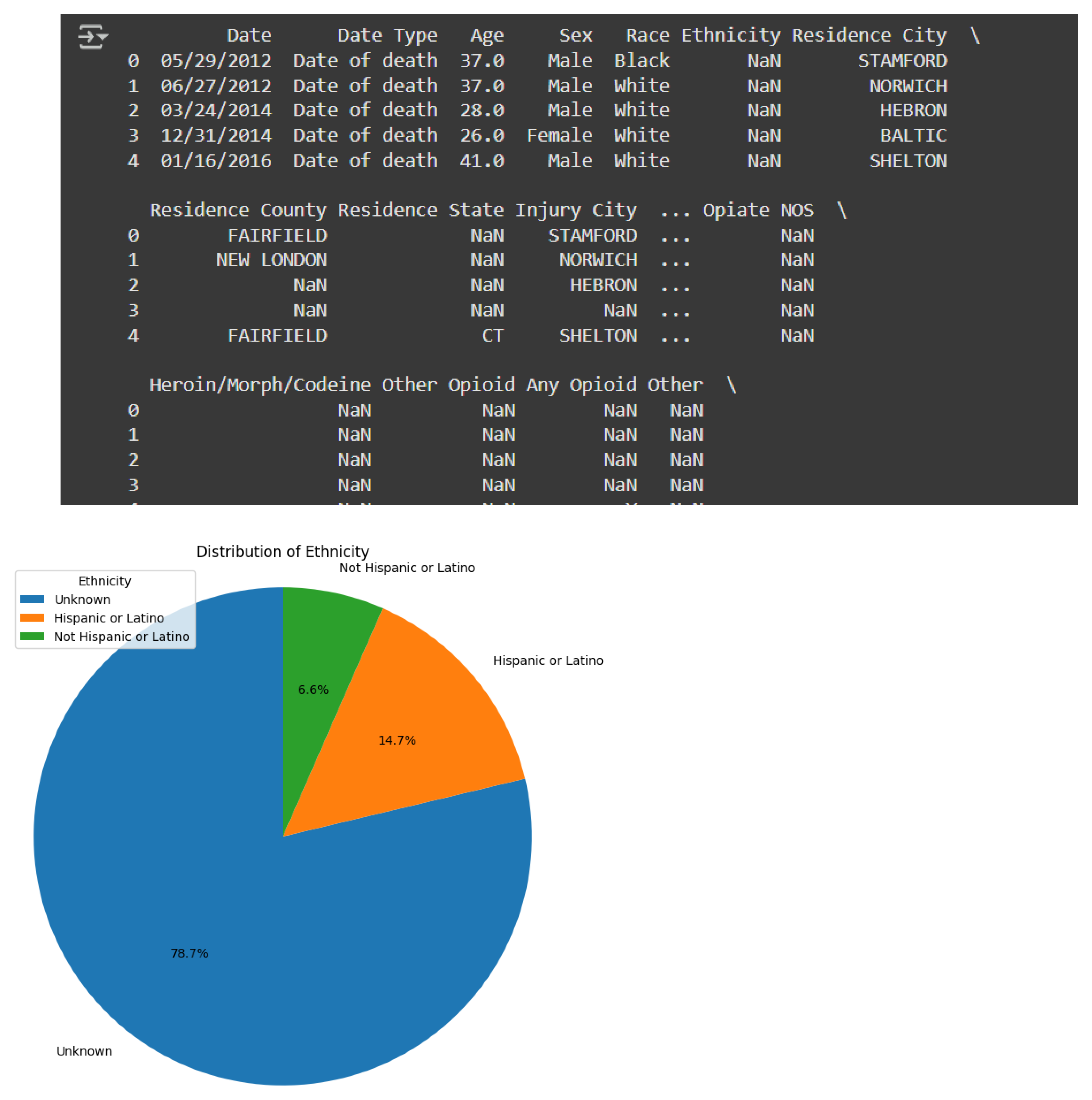

The Race column was subsequently mapped into standardized categories according to U.S. government classifications. The categories were: American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, White, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and Black or African American. “Unknown/Unreported” was used for entries indicating “Other (Specify)” or for missing data. The mapping of Race complied with federally mandated categories and offered an enhanced level of consistency for analysis purposes. Similarly, the Ethnicity variable was reduced to “Hispanic or Latino,” “Not Hispanic or Latino,” and “Unknown,” for the missing values. However, with over 9,000 missing entries in this column, it was clear that this column did not meaningfully contribute to the current study. Therefore, the Ethnicity column was dropped.

Next up was Injury Place. Again, the number of unique and null values were printed for the reader's review. The entries had different descriptions of the place for location. As before, fewer but standardized categories were created. Then in ResidenceCityGeo I found three entries where I only had Connecticut (CT) and coordinates for the Location (town names were missing) without any way to look up what the town name was. I found the missing town names via Google and input them into the dataset. I noticed that City Names were all uppercase in the ResidenceCityGeo and InjuryCityGeo column. To improve readability to the reader and provide a more professional appearance, I capitalized the first letter of each word for those City Names except for the abbreviations for the states (those remained all uppercase).

The manner of death column had values such as "Accident", "Natural", and "Pending". As this dataset is strictly for an accidental drug-related death, the rows for "Natural" and "Pending" manner of death entries were removed. After the data removal, it was clear that all rows listed "Accident" in the Manner of Death column, therefore, it was redundant and dropped from the dataset.

Figure 48.

Unnamed: 49, Any Opioid, Other Opioid, Any Other Opioid.1 (This was the temporary version of the merged column we created while completing the earlier task). These columns were all empty of meaning in one way or another and we replaced them with more concise representations. The list of columns was double checked and I could feel good that all we had intended to do was accomplished.

Figure 48.

Unnamed: 49, Any Opioid, Other Opioid, Any Other Opioid.1 (This was the temporary version of the merged column we created while completing the earlier task). These columns were all empty of meaning in one way or another and we replaced them with more concise representations. The list of columns was double checked and I could feel good that all we had intended to do was accomplished.

The Other Significant Conditions column contained a sizeable amount of varied, non-standardized entries. Any missing values were replaced with 'N/A' in order to retain that column in the dataset while avoiding introducing inconsistency or losing valuable information.

For all drug related column (i.e., Heroin, Cocaine, Fentanyl, Ethanol, etc.), unique entries were standardized to binary values of 'Y' and 'N' indicating whether or not that drug was part of that patient's treatment plan. This was done to maintain a uniformity of reporting that would be compatible with many classification and clustering algorithms. The same transformation was repeated for the more infrequently used drug columns, (i.e., Methadone, Amphet, Tramad, Gabapentin, etc.)

The Other column was examined next, as it also contained an abundance of named substances. Unique values from within that column were grouped into 11 standardized categories using a mapping strategy that was based on the drug type or similarity in chemical structure. The missing values in this column were also replaced with 'N/A' since those rows did not report evidence of any substances beyond the identified labels.

The geographic columns (Residence City Geo, Injury City Geo, and Death City Geo) were separated into three different components - city, state, and geographic coordinates, using a string split given the established structure ('City', 'State', and geo-coordinates). Next, the coordinates were also separated into two separate new columns (LAT for Latitude, LONG for Longitude), making geospatial analysis more intelligible. Once these transformations were finished, the original GEO columns were dropped since we had delineated/restructured their information.

7.6. Data Reduction

In order to reduce the number of columns and eliminate redundancy, the number of columns were dropped for a reasons that can be justified. The Residence City, Residence County, Residence State, Injury City, Injury County, Injury State, Death City, Death County, and Death State columns were removed because they had a lot of missing data. In addition, we had already introduced columns for geolocation earlier and they provided all this information in a way that would be useful. The Cause of Death column was also dropped. The contents of the Cause of Death column overlapped substantially with the individual drug-specific columns, and therefore, would be redundant for our intended analysis. The Heroin death certificate (DC) column was dropped as well because it was incomplete and did not specifically explain substance-related deaths. Therefore, the Heroin DC was also not relevant for any type of data mining purpose as it could not be expressed as an actual drug or condition.

7.7. Encoding

All categorical fields were encoded into numerical types to prepare the data for machine learning purposes. It is necessary to encode categorical data into numerical formats for use with algorithms that need numerical input. The cleaned dataset saved as FINAL.csv After an error during processing was encountered, the Other and Other Significant Conditions were processed and finalized to complete the transformation and preparation of the data. The fully cleaned and encoded version of the dataset was then saved as FinalCleanDataset.csv.

7.8. Data Visualization and Interpretation

This section presents the visualizations developed to interpret the patterns, distributions, and trends found within the dataset.

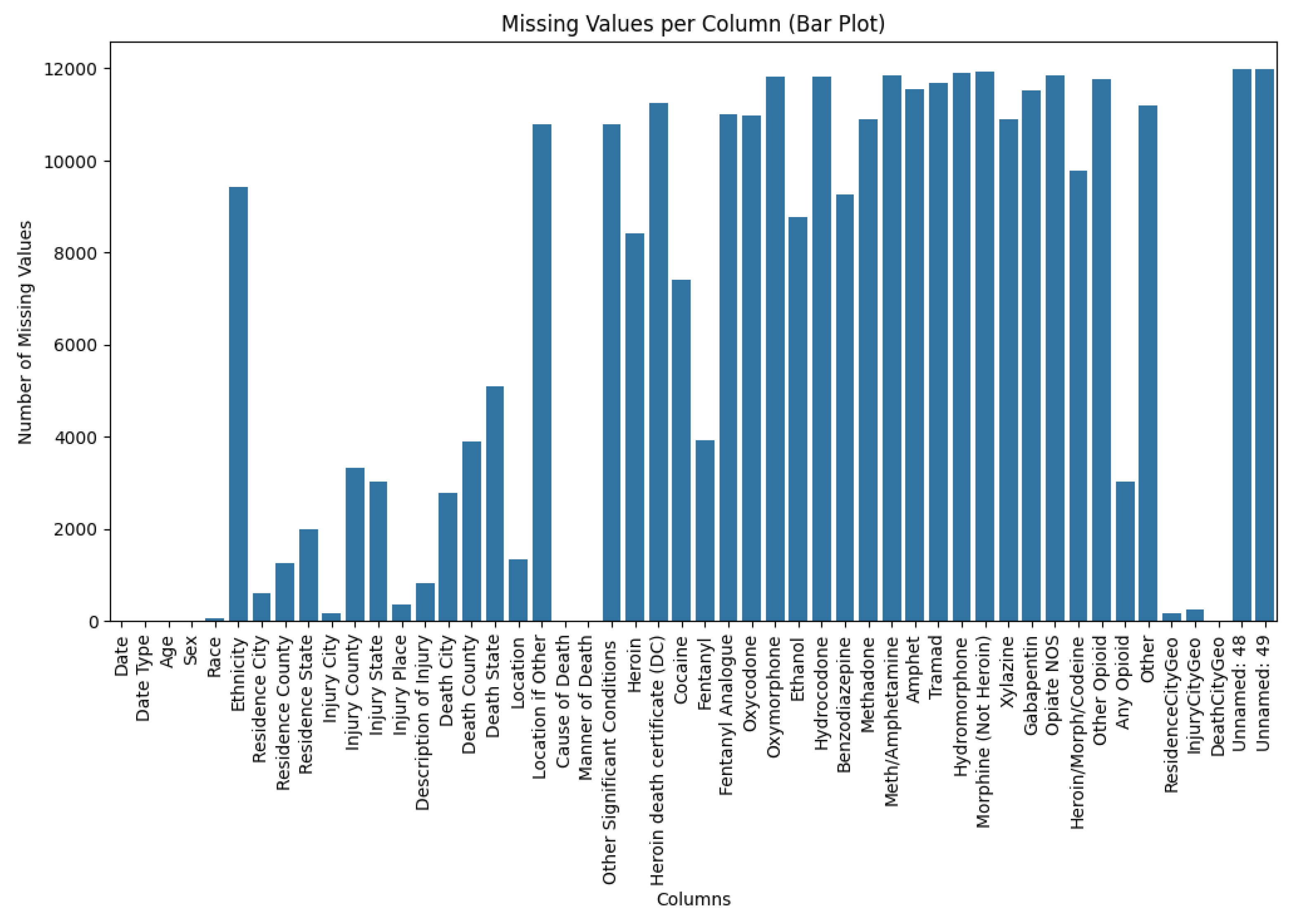

Figure 1.

Missing Values per Column (Bar Plot).

Figure 1.

Missing Values per Column (Bar Plot).

The bar chart demonstrates the number of missing values for each column. For example, Date, Date Type, Age, Sex, and Cause of Death have no missing values or only very few, while Unnamed: 48 and Unnamed: 49 have the highest missing values and unused information.

Figure 2.

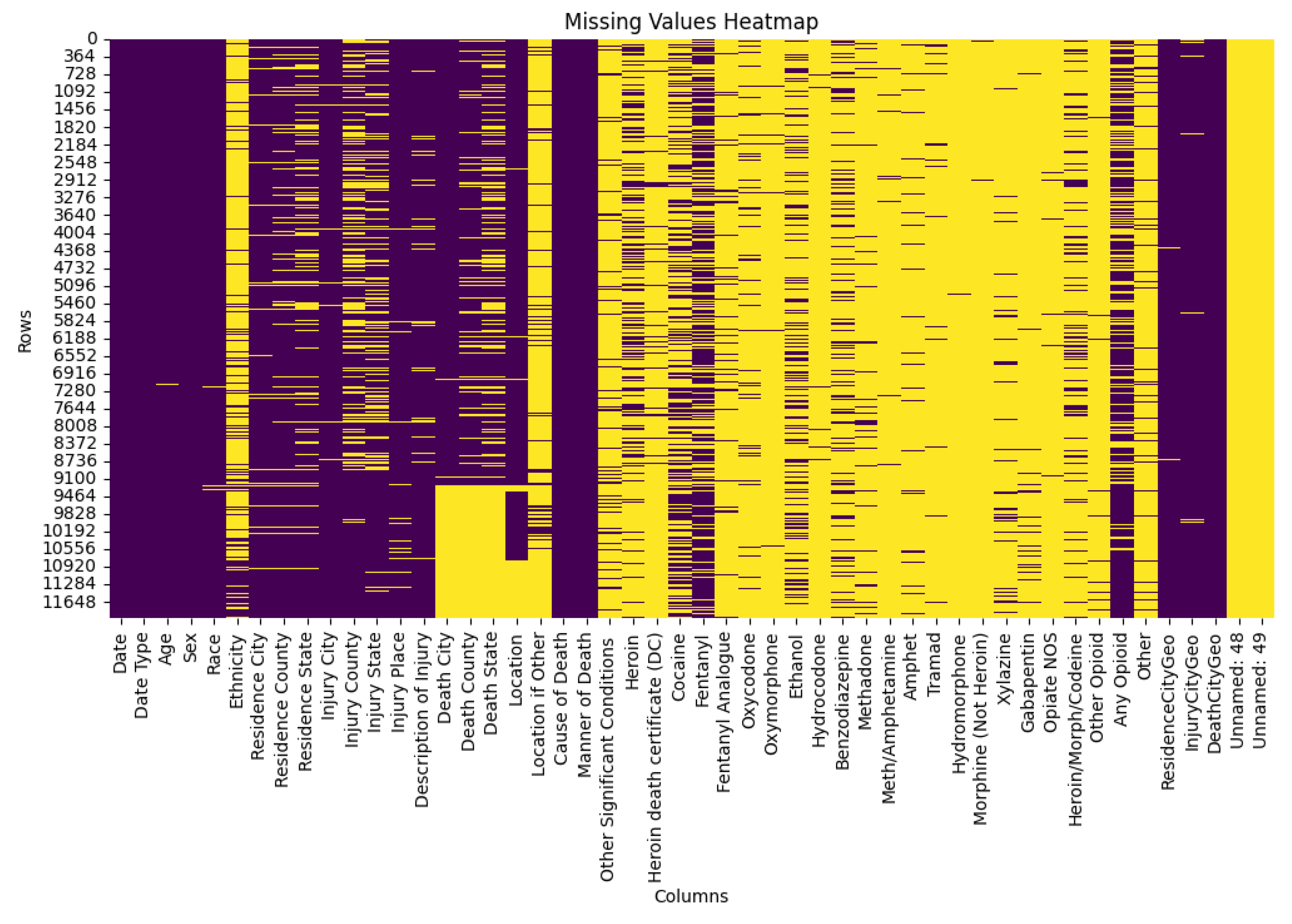

Heatmap of Missing Values Before Preprocessing.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of Missing Values Before Preprocessing.

The heatmap uses purple to indicate present values and yellow to denote missing ones. These visual highlights the extent and distribution of missing data across all columns before cleaning.

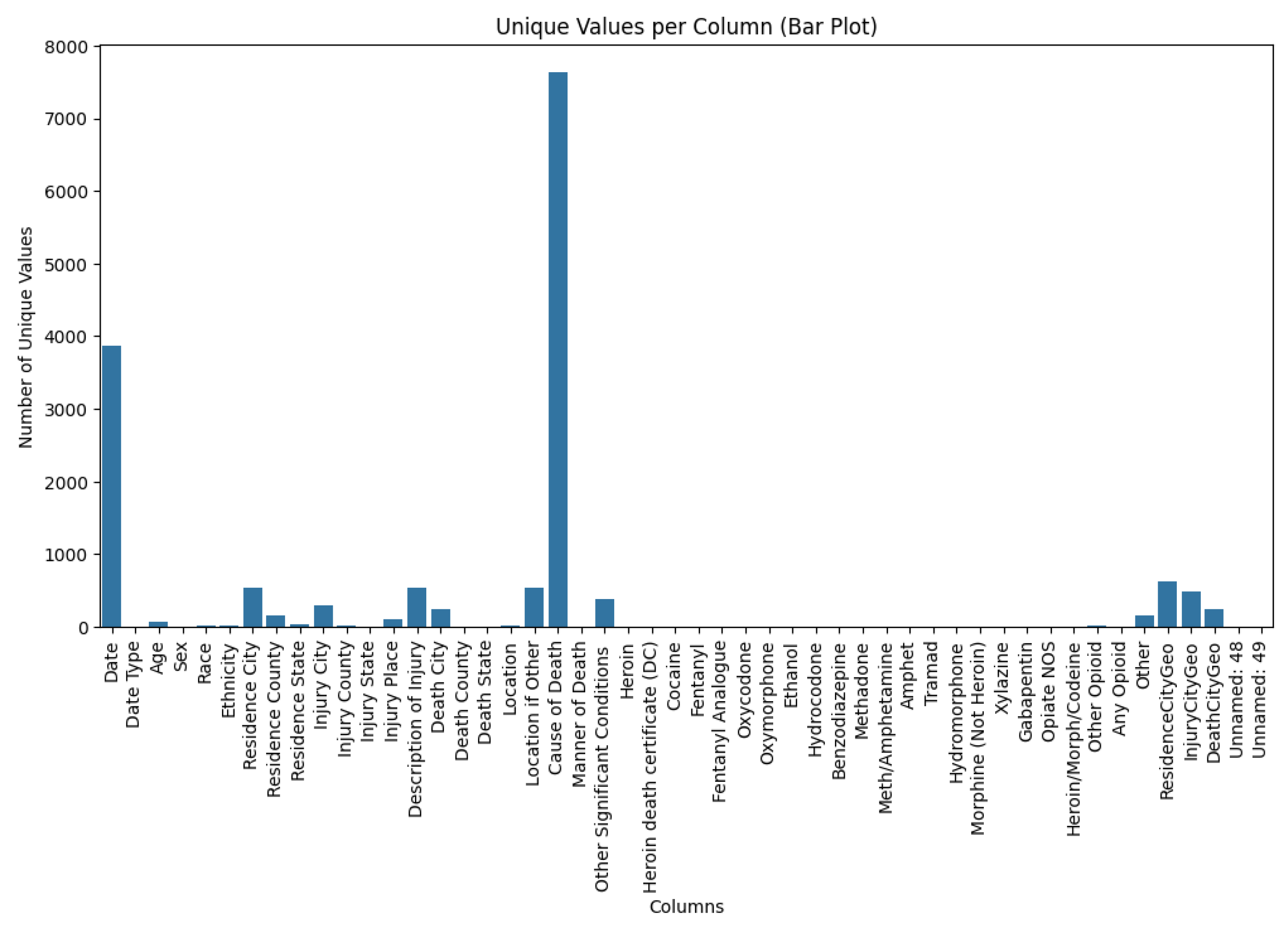

Figure 3.

Unique Values per Column (Bar Plot)

Figure 3.

Unique Values per Column (Bar Plot)

This bar plot reveals the number of unique values in each column. The Date and Cause of Death columns contain the highest number of unique entries, while most other columns show relatively limited variability.

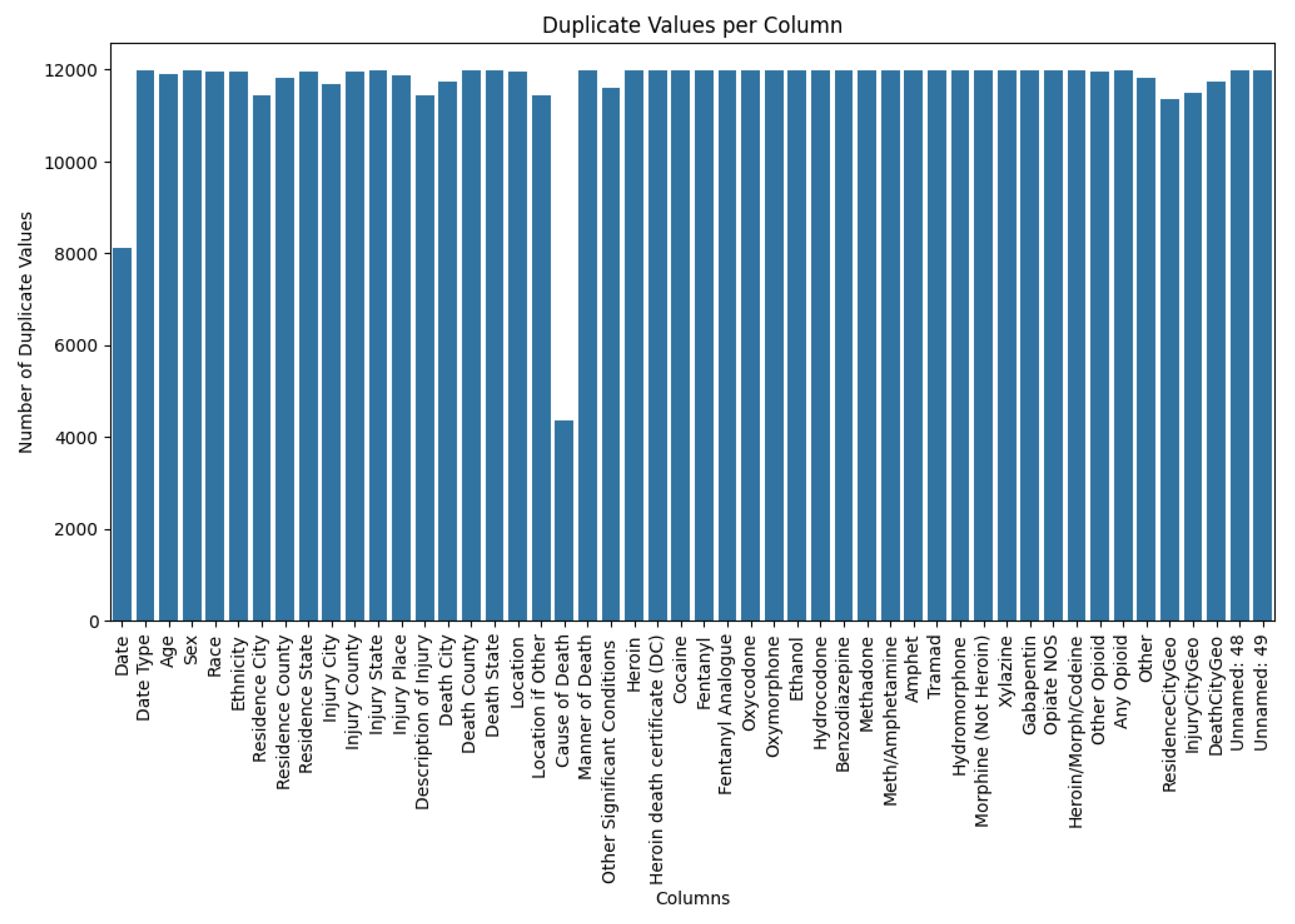

Figure 4.

Duplicates per Column (Bar Plot).

Figure 4.

Duplicates per Column (Bar Plot).

This plot demonstrates that many columns—such as Sex, Date, State, City, and Substances Used—have a high number of repeated values. This repetition is expected, as these categories often overlap across different cases.

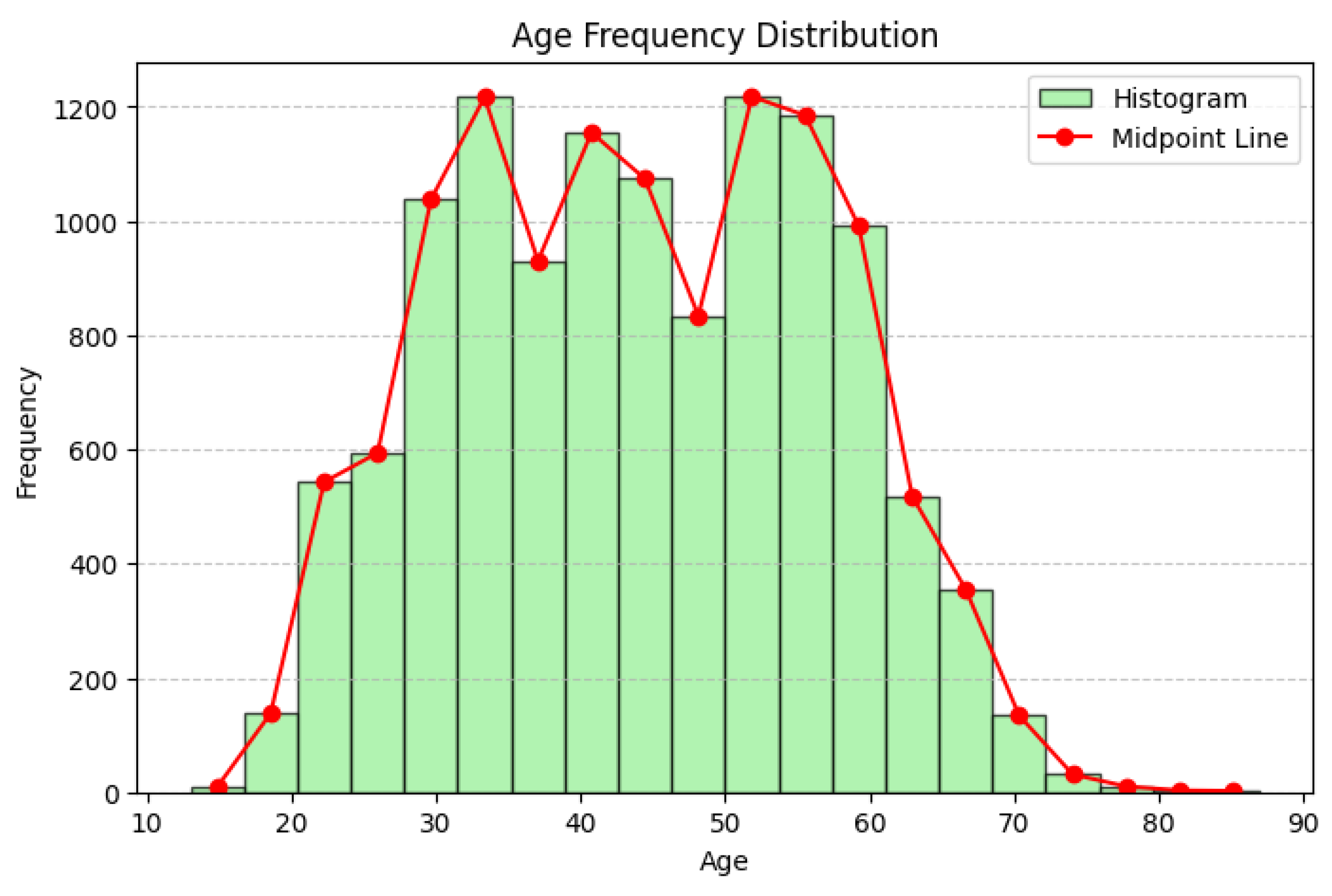

Figure 5.

Age Distribution Before Preprocessing (Histogram).

Figure 5.

Age Distribution Before Preprocessing (Histogram).

This histogram shows the raw age distribution of the victims. The data displays a wide age range but lacks consistency due to uncleaned data.

Figure 6.

Overdose Deaths by Sex Before Preprocessing (Bar Chart).

Figure 6.

Overdose Deaths by Sex Before Preprocessing (Bar Chart).

The chart reveals that males represent the majority of overdose deaths. This trend remains consistent even after the preprocessing phase.

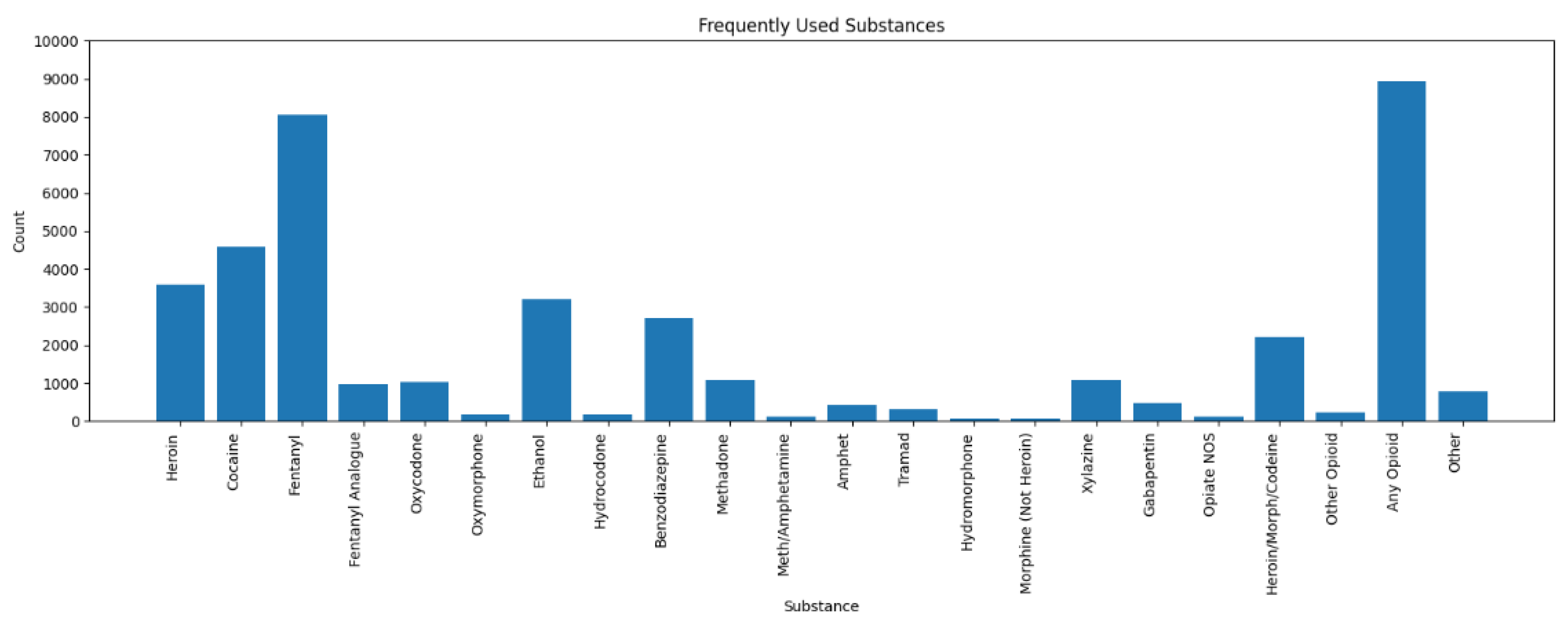

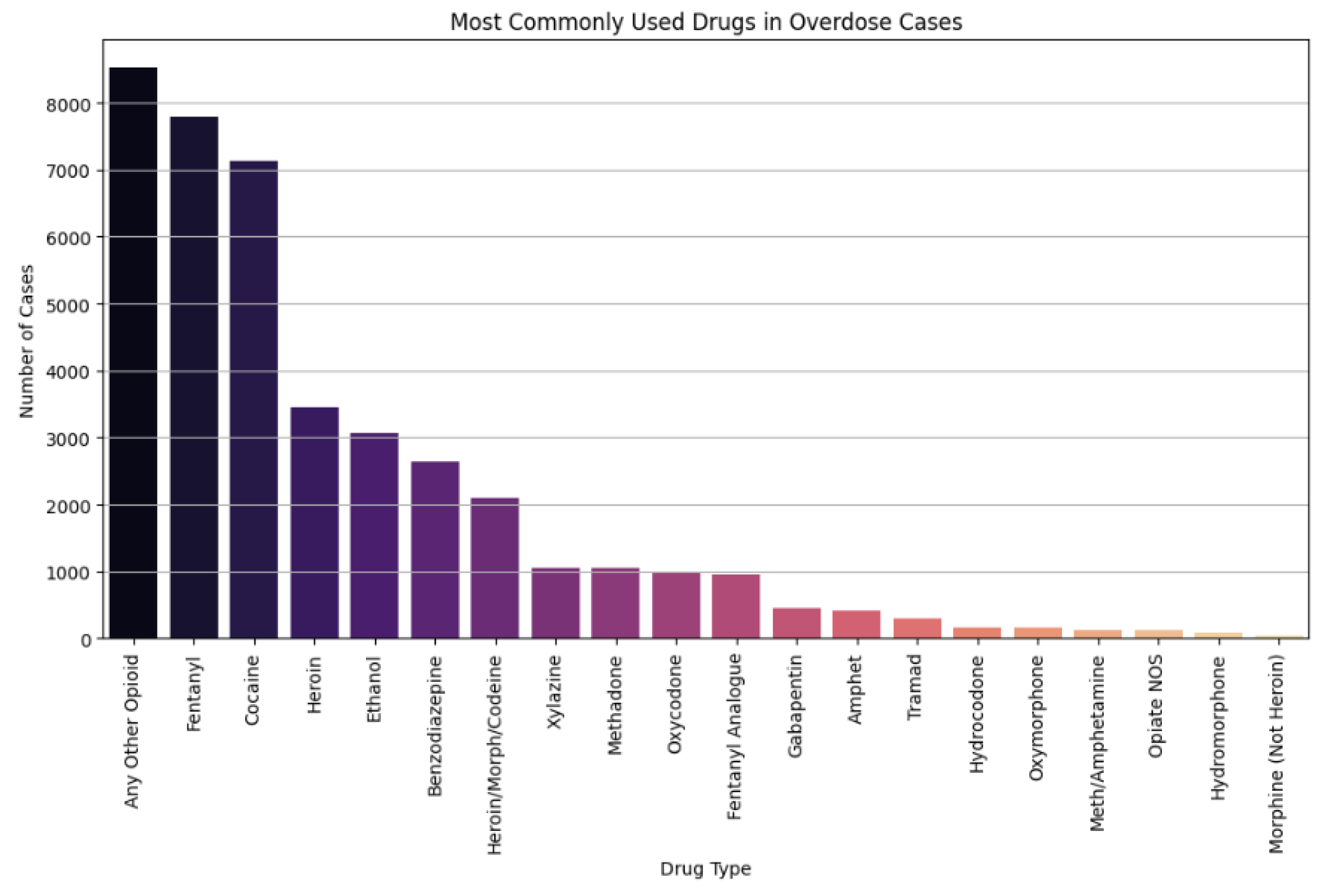

Figure 7.

Most Frequently Used Substances in Overdose Cases (Bar Chart).

Figure 7.

Most Frequently Used Substances in Overdose Cases (Bar Chart).

This graphical display shows that Fentanyl and Any Opioid predominated in the number of overdose cases, followed by Cocaine and Heroin. A few substances were also detected but rather infrequently. The Heroin Death Certificate column was omitted from the analysis, as it does not identify anything that could be considered a substance.

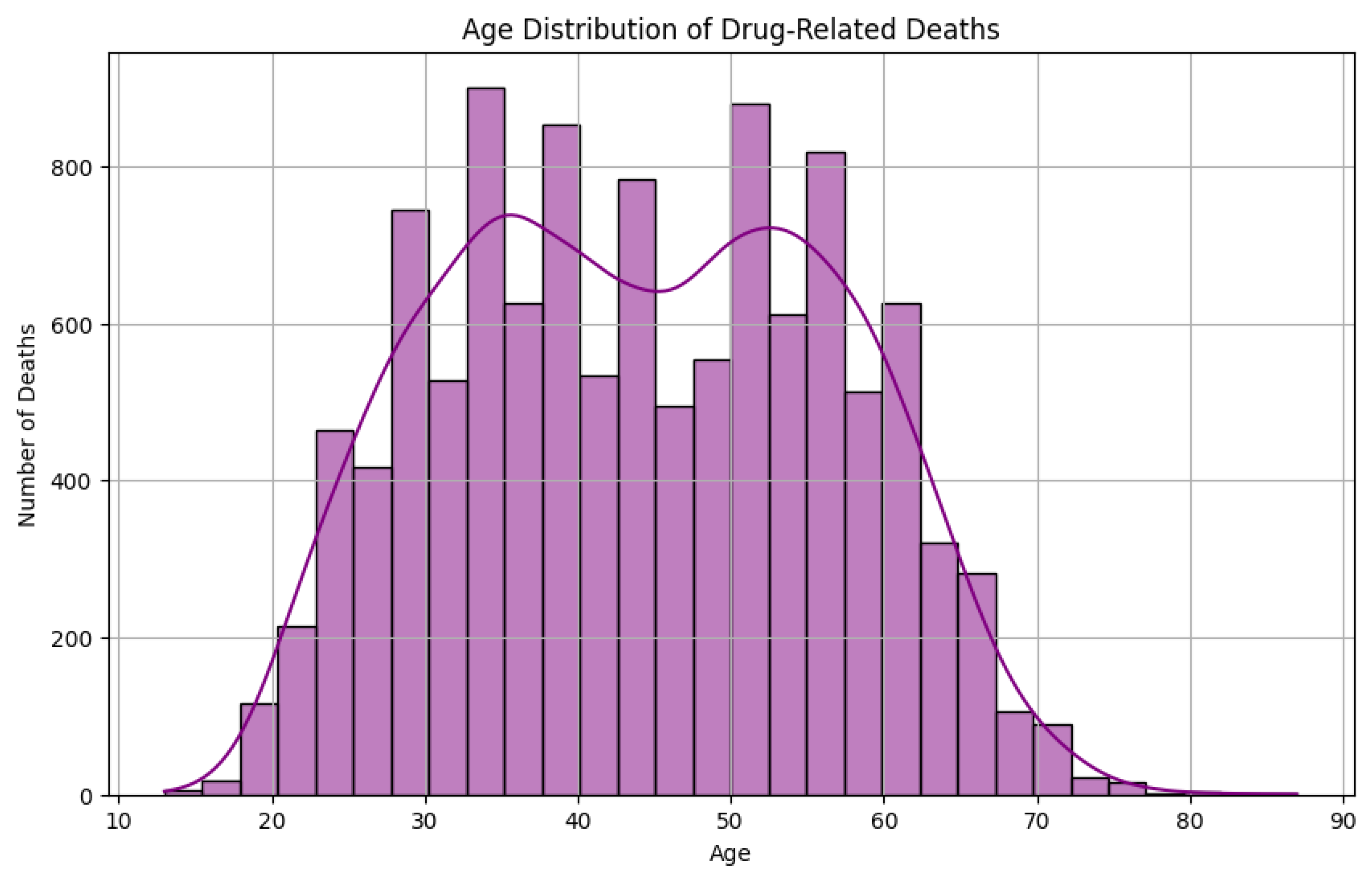

Figure 8.

Age Distribution After Preprocessing (Histogram).

Figure 8.

Age Distribution After Preprocessing (Histogram).

After cleaning, the age distribution shows a strong accumulation of overdose cases among the 20-50 year age range. The younger and older age distributions are smaller, which indicates that the middle-aged group is the most affected population.

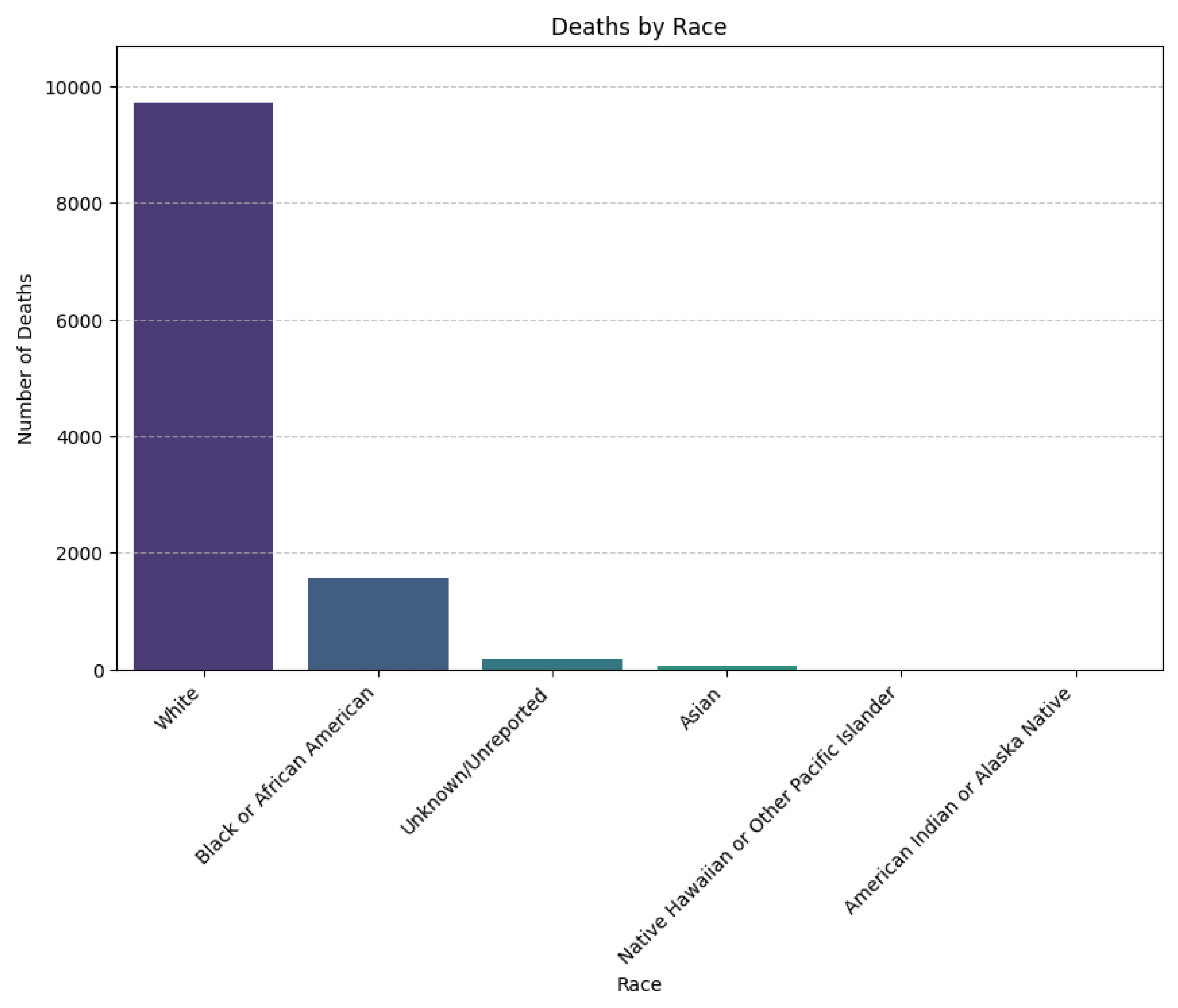

Figure 9.

Deaths by Race (Bar Chart).

Figure 9.

Deaths by Race (Bar Chart).

This chart, generated after preprocessing, shows that White individuals make up the largest proportion of overdose deaths, followed by Black or African Americans, then Unknown, and other racial groups such as Asians.

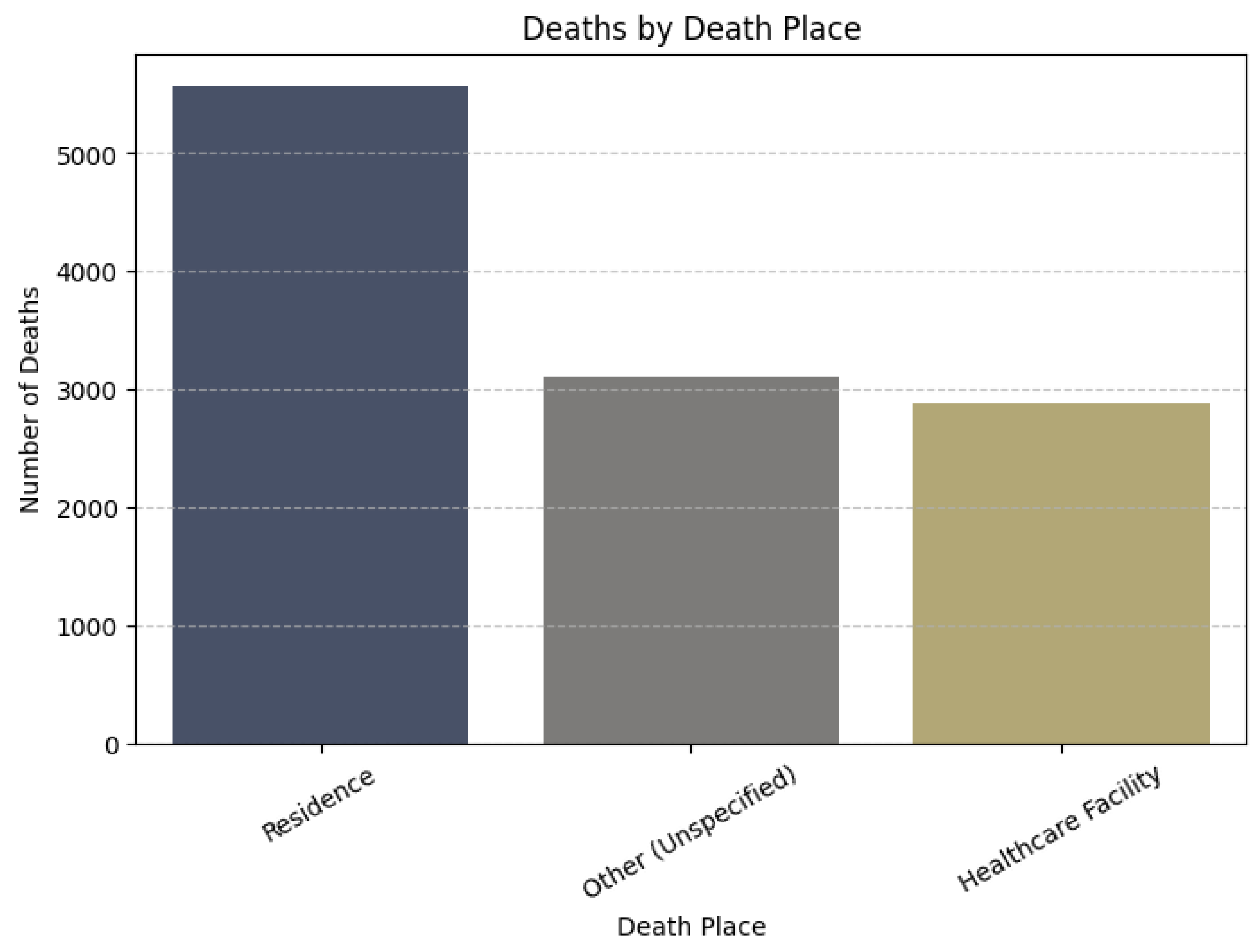

Figure 10.

Deaths by Location (Bar Chart).

Figure 10.

Deaths by Location (Bar Chart).

The majority of overdose deaths occurred in private residences. This is followed by unspecified or miscellaneous locations, highlighting the need for targeted interventions in home settings.

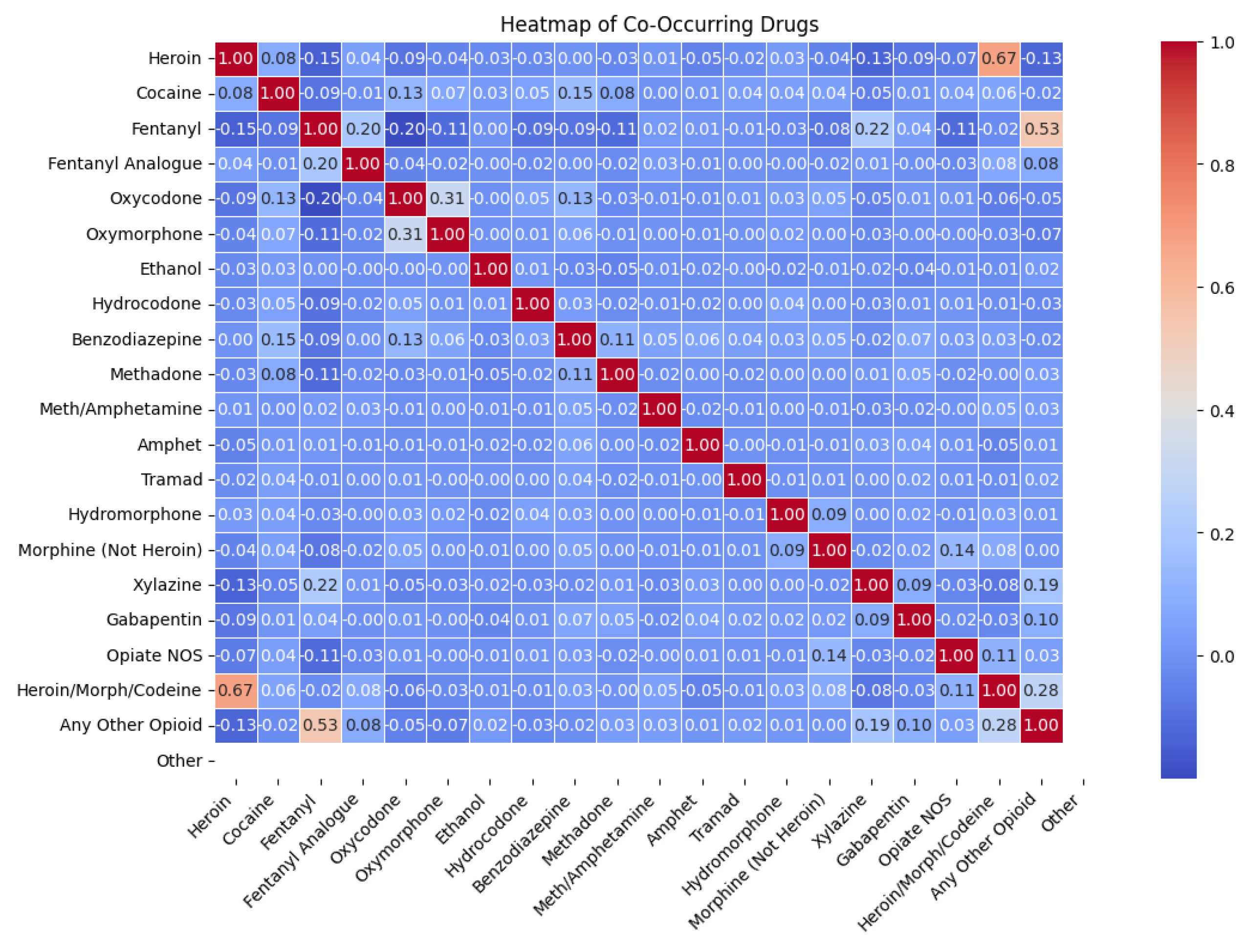

Figure 11.

Co-occurrence Heatmap of Substances.

Figure 11.

Co-occurrence Heatmap of Substances.

This heatmap shows the relationships between substances used in overdose deaths. A value of 1 indicates a perfect positive correlation (exactly the same substance) and a value of 0 indicates that there is no correlation. This visualization helps illustrate the often noted co-occurrence of multiple substances in fatal overdoses.

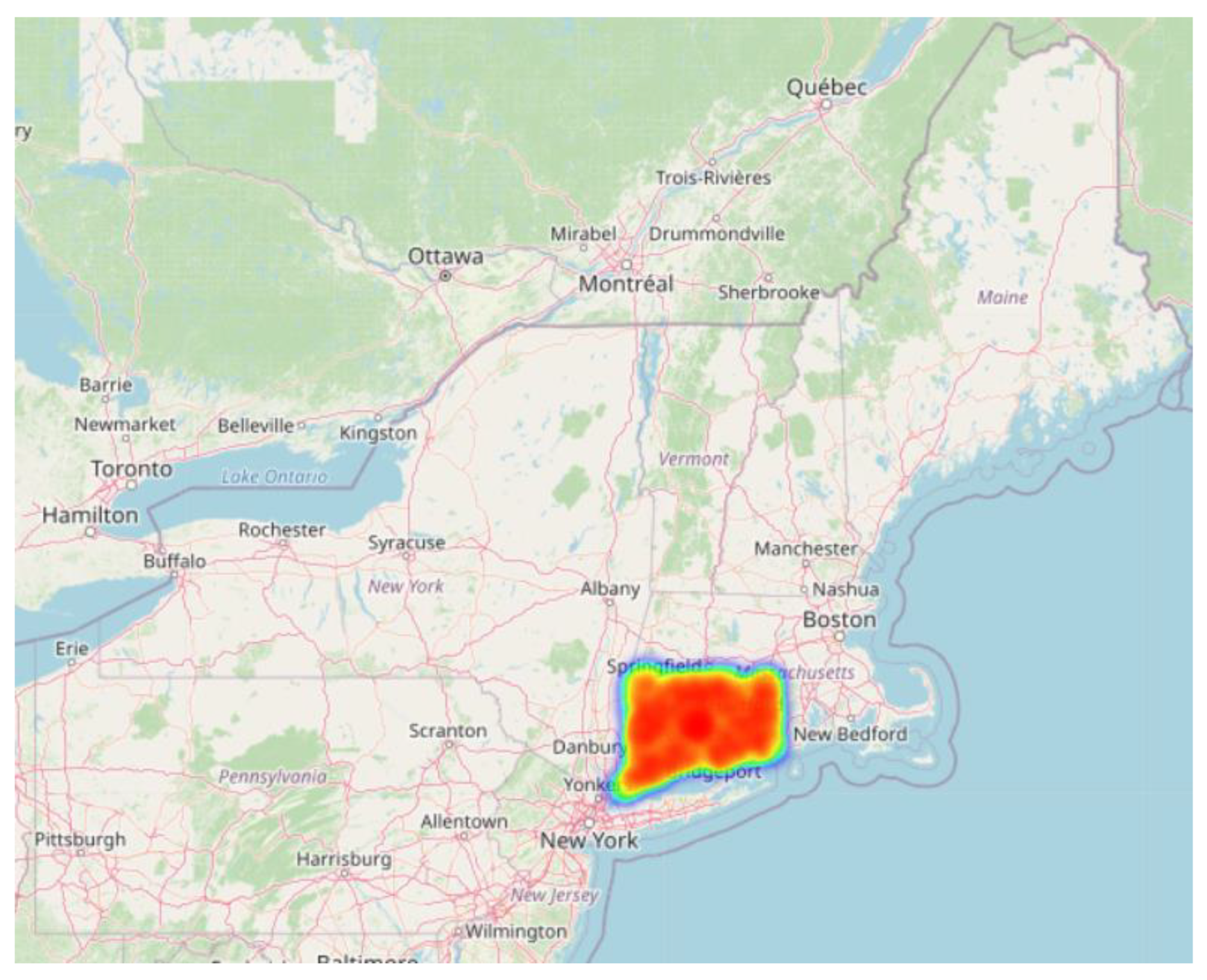

Figure 12.

Geospatial Heatmap of Overdose Clusters (Zoomed View).

Figure 12.

Geospatial Heatmap of Overdose Clusters (Zoomed View).

This map highlights the concentration of overdose deaths, with a clear hotspot in the eastern United States—specifically in the state of Connecticut.

Figure 13.

Top 20 Cities with Highest Overdose Deaths (Bar Chart).

Figure 13.

Top 20 Cities with Highest Overdose Deaths (Bar Chart).

Middletown had the highest number of overdose deaths, followed by Hartford and New Haven. Derby had the fewest fatal overdose cases among the top 20 cities.

7.9. Ethics of Data Mining

Ethical integrity is highly important in the field of data mining. The data in this study were public health data, which could include personal information, making ethical integrity particularly important. Our study abided by a number of key ethical considerations as to how we handle and analyze data.

7.10. Data Protection and Privacy

All personally identifiable information must be anonymized to ensure privacy. As part of preprocessing, any identifiers that could be used to identify individuals were removed or masked.

7.11. Prevention, Breach Protection and Controlled Access

Data protection and security are a major priority. Sensitive data including public datasets should proactively protect DOS. Sensitive data should also have restricted access and held only by authorized personnel. Sensitive data should be stored securely and if possible in encrypted formats to reduce the risk of unauthorized access, data breaches or any possible compromised data.

7.12. Bias and Accuracy Concerns

It is essential to ensure that the dataset is representative and free from biases. Care was taken to handle missing and inconsistent data appropriately and to avoid introducing skewed results. Machine learning models can unintentionally amplify biases, so transparency in model assumptions and decision-making processes is necessary.

7.13. Transparency Around Data Use

When individuals give data, they deserve to know how that data will be used, who will use it, and what rights they have over the data. Transparent data usage minimizes ethical risks and builds trust in data practices.

7.14. Data Misuse and Abuse

Data should only be used for the purpose it was collected for. Any other use—surveillance, manipulation or potential reputational harm—is unethical.

7.15. Data Ownership

Data ownership needs clear boundaries. When individuals give data they should retain certain controls unless they have voluntarily waived that control through informed consent. Vague or misleading data ownership agreements lead to misuse and exploitation. Lastly, it is critical that the ethical implications of data mining cannot be overlooked. Respecting privacy, accuracy, and responsible usage of data lead to public trust where social good is achieved.

8. Discussion

This research utilized several data mining techniques to examine accidental drug-related deaths in the United States, with goals directed at identifying high-risk demographic groups, substance combinations, and geospatial patterns. The findings from the analysis yield actionable information that could be helpful to improving public health policies and emergency-response structures.

Association rule mining uncovered notable co-occurrence patterns amongst substances, where substance combinations such as fentanyl and heroin, were prevalent within fatal overdose cases. These co-occurrence patterns are consistent with previous literature, confirming the dangerous merging of opioids. The value of being able to identify these types of patterns benefits emergency healthcare responders in predicting possible substance combinations when responding and/or developing treatment approaches.

Classification techniques using decision trees and logistic regression effectively identified high risk demographic groups. Middle-aged men, specifically white and African Americans, were disproportionately impacted by overdose fatalities. This finding is consistent with National Institute on Drug Abuse reported figures and supports the rationale for public health forward-facing advocacy for certain demographic groups.

Clustering methods i.e. K-means, hierarchical clustering, also aided the identification of high-risk areas and the clustering of people in demographic groups. A notable number of deaths occurred in the state of Connecticut, specifically in cities within Connecticut, for example, Middletown, Hartford, and New Haven. The clustering in these areas may signal a greater socio-economic issue, access to substances, or healthcare disparities and can be helpful to regional needs assessments and planning of resources and interventions.

Outlier detection was also performed to find unusual cases, particularly with respect to age. Unusual ages (very high, very low) in overdose data suggest that there may be reporting errors, as well as emerging at-risk groups we have not previously considered. These outliers matter because they may indicate changing drug use or data integrity problems. The report defines a formalized process for data preprocessing from handling missing values, standardizing categorical data and transforming geolocation as well as the substance fields. This degree of cleaning improved the quality of the analysis and the ease of producing different visualizations. Particularly the way ethnicity and race were handled was respectful and consistent with federal standards and protocols. The appropriate handling of these data is important for making valid and ethical demographic comparisons.

Heatmaps, bar plots, and pie charts gave excellent insights into how overdose cases were distributed by factors such as substance, location, race, and age. Such visual tools are able to make clusters and trends more accessible, supporting the interpretation of mining results. As in the preceding cases noted in the ethical consideration, it's a worldwide call for data privacy, responsible usage, and bias mitigation context. Such debate over transparency, ownership of data, and hence misuse has become very fitting in today's data-political milieu. This dataset is being used directly or indirectly with many studies, including [

21,

22,

23,

24], for different aspects and findings.