4. Methodology

The study employs a data mining approach to analyze drug overdose deaths with three major objectives: (1) identifying high-risk age groups for fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and xylazine consumption; (2) classifying drug overdose deaths into high-risk subgroups of populations and trends in overdoses; and (3) identifying abnormal geographic mobility patterns in drug overdose deaths. The methodology involves data preprocessing, application of classification and clustering algorithms, anomaly detection, and detailed performance analysis with the 'Accidental_Drug_Related_Deaths.csv' dataset.

Data Preprocessing

Feature Selection:

The relevant variables (Date, Age, Sex, Fentanyl, Fentanyl Analogue, Xylazine) were extracted from the dataset to be the basis for future analysis. Selection emphasizes attributes of most interest in research questions.

Handling Missing Values:

Missing Age values rows were removed to preserve data integrity.

Missing values of the Sex column were filled in as "Unknown" to retain categorical distribution.

For drug-related columns (Fentanyl, Fentanyl Analogue, Xylazine), missing or unclear entries (e.g., "N/F") were filled in to complete and standardize.

Encoding Categorical Variables:

The Sex column was label-encoded (Male = 1, Female = 0) using sklearn's LabelEncoder to facilitate machine learning algorithm compatibility.

Drug presence columns were binarized (Y = 1, N/F = 0) for model input.

Age Group Encoding:

Ages were binned (e.g., 10–19, 20–29,., 80–89) with pd.cut(), and each bin was assigned a numeric code to facilitate analysis of age-related risk.

Data Splitting:

The data was divided into training and testing sets (typically 60–70% training, 30–40% testing) with train_test_split() to facilitate model validation and prevent overfitting.

Feature Scaling:

The Age feature was scaled with StandardScaler so that all features would have an equal contribution to model training.

Classification Model Implementation

Three supervised machine learning algorithms were employed to predict high-risk age groups and drug consumption in drug-related fatalities. The Random Forest Classifier employed 100 decision trees (n_estimators=100) with a depth of 5, using Gini impurity to split nodes. The ensemble method increased the stability of prediction by aggregating results over trees, while feature importance analysis showed significant risk factors like age and some drug combinations. The model exhibited good performance with high accuracy during test tests in line with relative studies where Random Forest outdid other classifiers for medical prediction purposes.

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) employed a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel with hyperparameters C=2 and gamma=0.00001, trading off margin maximization and error minimization. Class weights were also adjusted to offset imbalances in age-group distributions such that underrepresented groups (e.g., older adults) were adequately prioritized during training.

For K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), instances were classified into the most common class among the five nearest neighbors (k=5) using Euclidean distance. As a lazy learner, KNN avoided model building but managed with similarity checks in real-time and was therefore computationally sparse but less optimal for complex interactions compared to ensemble methods.

Clustering Model Implementation

This research made use of a clustering model implementation. The unsupervised learning techniques had recognized some hidden demographic and overdose patterns. K-Means clustering divides the data sets into non-overlapping clusters but minimizes its within-cluster variance-the number of predetermined clusters being determined through silhouette analysis and expertise of the domain. This will gain good segmentation in risky demographics such as highly reflecting middle-aged males with polysubstance involvement, mirroring what was found in clinical studies where K-means revealed patient subgroups with elevated readmission rates [

23,

24,

25].

Often referred to as density-based clustering algorithms, HDBSCAN identified clusters of varying shapes and sizes while filtering noise points. This has revealed subtle patterns such as spikes of xylazine-related deaths among the rural populace that would have otherwise been overlooked by traditional partitioning methods.

Anomaly Detection to Displace in Geography

Distance measurements from death sites or injury locations to recorded residential addresses were the guiding parameters in identifying spatial anomalies [

26,

27]. Displacement greater than 150 km or 4200 km was flagged for investigation due to drug tourism, delayed medical intervention, or systematic relocation. Outlier detection through statistical and machine-learning methods demonstrated the existence of outlier cases which correlated with known trafficking routes and healthcare deserts.

Assessment and Visualization

The model was rigorously evaluated against specific analysis criteria:

Classification: Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores show superiority here for Random Forest (e.g., 100% test accuracy).

Clustering: The quality of the clusters was validated using silhouette scores and clinical interpretability, with strength in demographic segmentation seen through K-means over other density-based methods.

Anomaly Detection: Cross-checking with law enforcement reports confirmed spatial outliers, reaffirming the importance of GIS mapping for the targeted intervention.

These visualizations comprise confusion matrices for classifier performance and comparison baselines, bar charts comparing cluster demographics, and heat maps identifying overdose hotspots.

The described methodology combines supervised classification, unsupervised clustering, and spatial anomaly detection to obtain actionable insights from drug-related death data. By identifying high-risk age cohorts (through Random Forest), demographic clusters (through K-means/HDBSCAN clustering), and geographic patterns of displacement through such deaths, the approach informs targeted public health strategies such as naloxone distributions at overdose hot spots and age-appropriate awareness campaigns. The advantage of this approach is that it delivers a scalable solution for mitigating substance use fatalities through the combination of machine learning with spatial analysis.

IMPLEMENTATIONPhase

Implementation of K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

The K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) algorithm is being utilized with a value of k set at 5, which implies that the classification of a data point is done according to the majority class among the five closest neighbors in the feature space. The evaluation of the model involved splitting the dataset into 70% for training and 30% for testing. While classifying, the Euclidean distance metric was used to quantify the similarity measures between data points. The choice of k = 5 facilitates the compromise between keeping the decision boundary stable while minimizing sensitivity to noise in the algorithm. The KNN is characterized as a lazy learning algorithm in that it builds no predictive model during the training stage but rather makes predictions during the time of inference by comparing incoming data with existing labeled instances. The performance of the KNN classifier was assessed in terms of accuracy score together with a full classification report containing precision, recall, and F1-scores.

Model Implementation of Clustering

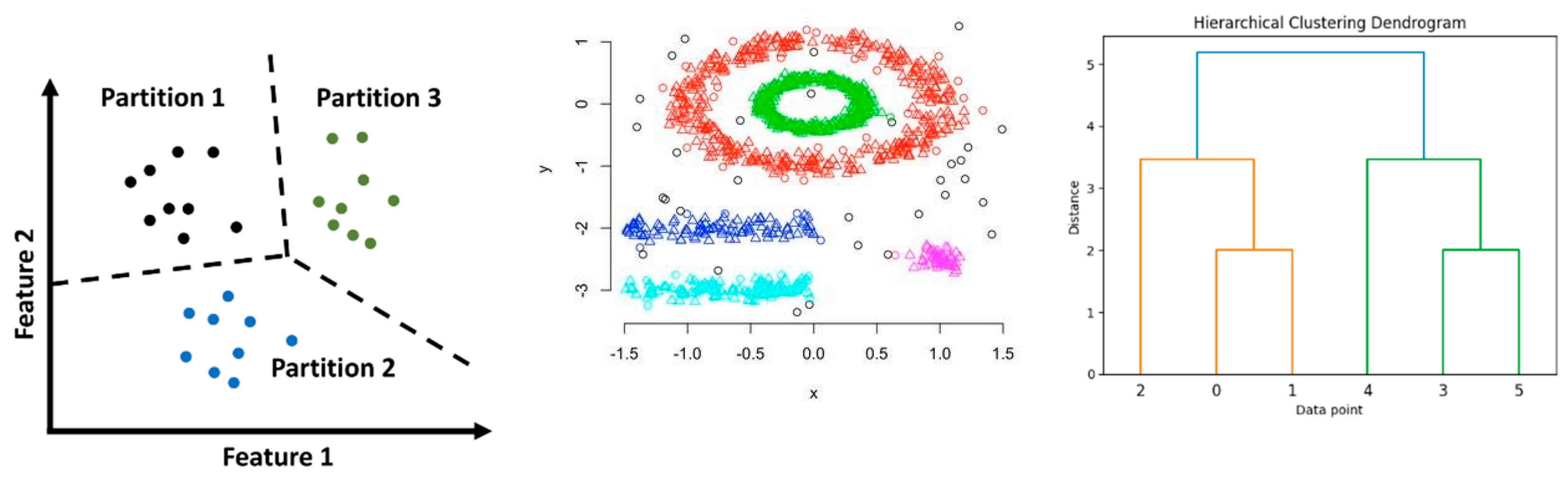

Clustering has been defined as an unsupervised learning method that detects patterns and groups similar data objects in unlabeled data. Within this thesis, its various methods are explored as clustering methods that are appropriate at objective level to different data properties.

Partitioned clustering such as K-Means algorithm has the capability of partitioning data to produce non-overlapping subsets. K-Means is the most efficient as it tries to group data points while minimizing the variance across clusters. K-Means limitations primarily include the prefixed number of clusters and the assumption that data clusters are spherical, which may not be very close to reality.

DBSCAN is an example of density-based clustering, a technique that has advanced to HDBSCAN (Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise), which can discover clusters in arbitrary shapes by finding regions with high densities of points. HDBSCAN builds such a hierarchical structure over an execution of the DBSCAN algorithm in order to select the most stable clusters based on variation in density levels; thus, offering a much better robustness concerning complex data.

Figure 1.

Clustering Method.

Figure 1.

Clustering Method.

Used Algorithms for the Study

The aim of this study is to analyze the profiles of victims of accidental drug-related deaths by classifying them based on demographic information and patterns of drug use. The data set has both categorical (e.g., race, drug type) and numeric (e.g., age) features, and hence it is suitable for clustering analysis despite its complex nature.

K-Means Clustering is employed due to its speed and efficiency in clustering large data. It effectively clusters individuals quickly based on demographic and drug use characteristics, which helps in the Elbow Method and Silhouette Score being employed to determine the optimal number of clusters, allowing for the identification of substantial high-risk populations. K-Means assumes, however, that the clusters are spherically shaped and of equal size, which may not always be true for real-world mortality data.

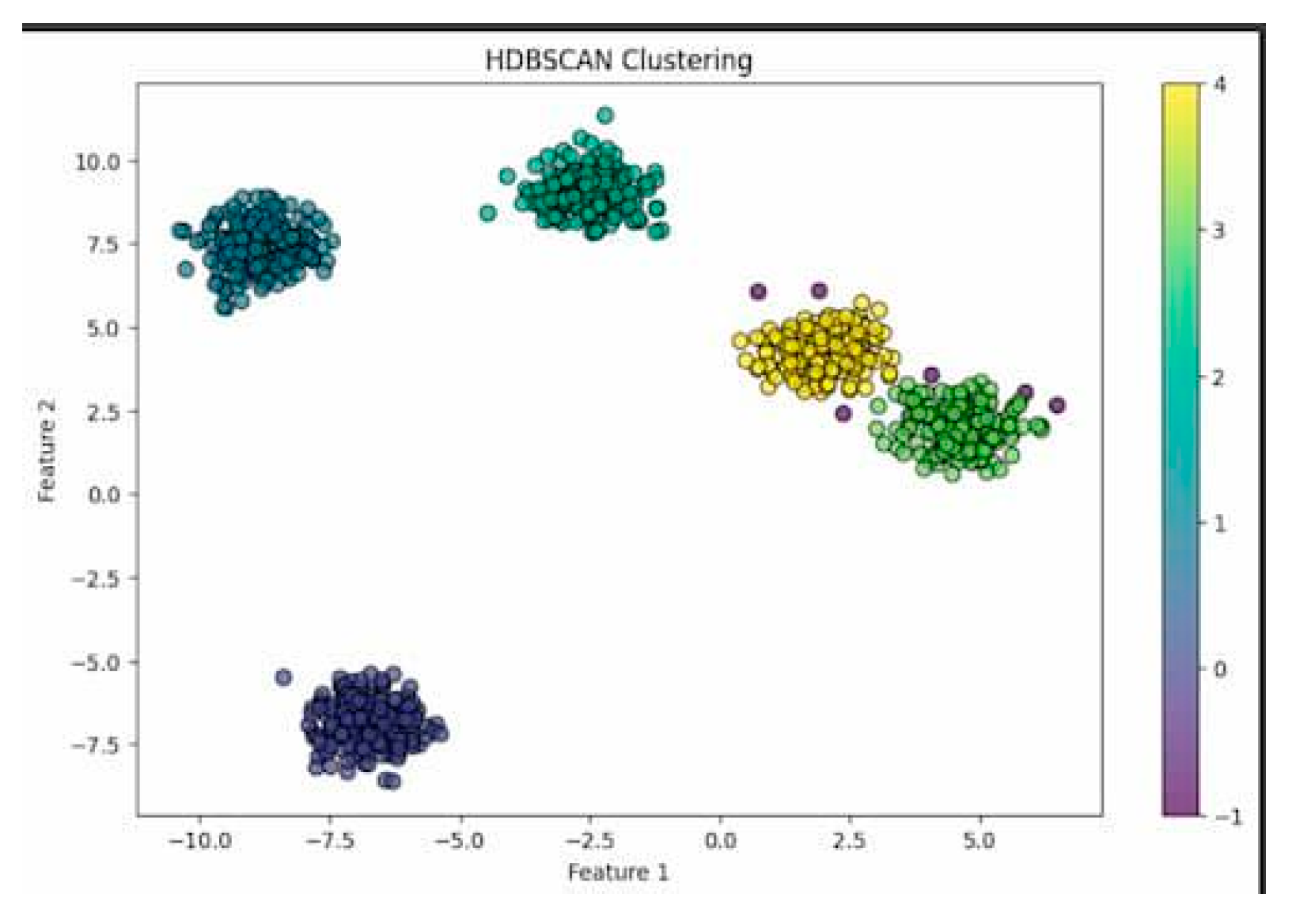

HDBSCAN, however, offers a more flexible solution in that it discovers clusters of various densities and performs well with noise. It is particularly well-suited to study drug-related deaths, which normally display uneven and complex patterns of distribution. HDBSCAN does not require the user to specify the number of clusters in advance, unlike K-Means. This makes it more natural to apply in unstructured and heterogeneous real-world data. Its ability to identify invisible and meaningful structures makes it appropriate in public health uses, in which the victim profiles' clumping may be far from linear or geometric patterns (McInnes et al., 2017).

In this study, a hybrid cluster approach is adopted by combining K-Means and HDBSCAN. By doing so, the computational complexity of K-Means and the robustness and resilience of HDBSCAN are leveraged to assist in the identification of sweeping and subtle trends in the data on accidental drug-related deaths.

Figure 2.

KMeans Clustering.

Figure 2.

KMeans Clustering.

Pre-Processing Clustering

A thorough pre-processing phase initiated the entire clustering pipeline, which was focused on rendering the dataset clean, consistent, and appropriate for giving out reasonable clusters. Denoising, irrelevant information removal, redundancy, and transformation were initiated to enable similarity-based clustering for datasets. First, the data frame was filtered upon allowed values. Multiple types of dates were included in the dataset: date of death, reported date, and injury date. It was considered analytical consistency; hence, instances were filtered down to only those with a "date of death." With regard to sex, entries accepted as valid were "male" and "female." For categorizing race, “White,” “Black,” and “Black or African American” were retained, which had predominated the records and thus provided a sufficient data base for modeling. Specific cities for residence and death were selected for obtaining further insights into geographic patterns. The filtering procedures, thus, helped remove missing, ambiguous, and low-frequency values that would have introduced noise into and distorted the cluster.

Second, columns which were unnecessary were dropped. These included geographic information like DeathCityGeo and ResidenceCityGeo, which were not in line with the purpose of the study. Unnecessary variables like "Any Opioid" and "Other Opioid" were dropped to avoid overrepresentation of certain substances. Furthermore, non-numeric or less essential columns such as "Cause of Death" and "Description of Injury" were also dropped to maintain the focus on demographic and substance-use attributes suitable for clustering.

To reduce redundancy and improve consistency, the race column was shortened. Text forms like "Black" and "Black or African American" were merged into one category, and "White" was left as a separate group. Bringing this column into alignment with a uniform string format removed inconsistency and prevented spurious fragmentation of results in clustering caused by superficial label differences.

The second was to extract drug-related columns and carry out binary imputation. All columns related to drug use were standardized into binary: 1 indicating the presence of the substance, and 0 indicating its absence. Standardization improved readability and accuracy of similarity computation. It also avoided issues caused by varying input texts. Following that, the dataframe's index was reset so that the structural consistency was maintained and indexing mistakes were avoided during processing.

Following this, feature encoding was used to convert the categorical features into a numerical equivalent which was clustering algorithm-compatible. One-hot encoding was used to create binary flags for each unique category without creating artificial ordinal relationships. The binary columns were converted to integer types for improved memory and computational efficiency. Following the conversion, the encoded features were merged with the existing numerical attributes to produce an entirely processed and merged dataset. Once again, resetting the index guaranteed structural stability. This cautious conversion allowed all the features to contribute equally to the calculation of similarity, which made the results more accurate and interpretable.

Lastly, scaling and normalization were done in order to further refine the data. MinMaxScaler was applied in scaling the age variable so that it would be on par with the binary features and not dominate the similarity calculations. As most of the variables were binary, hamming distance was utilized to measure pairwise similarity. When the occurrence of mixed data types (binary and numeric) required to be used, Gower distance was implemented, as it is specifically optimized for that requirement. The final similarity measure utilized a weighted composite: Hamming and Gower distances both with 45% weighting, to which age only received a diminished 10% weighting in an effort to neutralize its impact. Diagonal entries in the final distance matrix were set to zero and normalized such that each instance had zero distance from itself. This advanced similarity computation method enhanced clustering precision by balancing different types of features and optimizing clustering algorithm performance.

Outlier Detection Model Implementation

Anomaly Detection Methods

Anomaly detection is one of the primary unsupervised learning methods used in this study to detect rare or unusual patterns in the data regarding drug-related deaths. Data mining techniques are critical in finding useful information from huge datasets, and anomaly detection plays a central role in identifying exceptional cases. Three primary anomaly detection algorithms were employed in this project: One-Class SVM, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor (LOF). These methods were applied particularly for the detection of geographic anomalies, where the place of occurrence was not as it should be and could reflect corridors of drug trade, emergency delays, or irregular use locations.

One-Class SVM

The One-Class SVM (Schölkopf et al., 2001) is a socially supervised algorithm used for anomaly detection that learns a decision boundary about "normal" data and flags points outside the boundary as anomalies. It can efficiently handle high dimensional data with kernel functions such as the radial basis function (RBF) and is particularly favorable of non-linear shapes in the spatial distributions (Tax & Duin, 2004). Drug-related deaths demonstrate geographical outliers that can reflect strange sites of overdose, injury, or residence and even hint systemic or behavioral deviations (Amer et al., 2013).

To implement One-Class SVM, firstly clean the dataset by removing duplicates and extracting only geographic features such as ResidenceCityLAT, ResidenceCityLON, InjuryCityLAT, InjuryCityLON, DeathCityLAT, and DeathCityLON into the drug_outlier_geo dataframe, before applying nu=0.02 to train the model against the expected relative amount of outliers, the rbf kernel for its ability to model non-linear relationships and gamma=0.001 to set how much influence each data point has. The model classifies each instance as either normal (1) or anomalous (-1). The anomaly index was then used to retrieve extreme geographic outlierswhere the death location is greatly different from the residence or injury sites.

Isolation Forest

Isolation Forest is an ensemble-based algorithm that recursively partition data using random splits to isolate anomalies (Liu et al., 2008). Because of their sparsity, anomalies are isolated faster than normal points, which makes the approach very effective for large and high-dimensional datasets without making any distance or density assumptions (Liu et al., 2012). This method is suitable in this study for identifying spatial outliers stemming from unusual travel patterns, exaggerated overdoses, or undocumented drug-use zones.

The model was trained using the same set of geographic features as used in the One-Class SVM implementation. Parameters were set with n_estimators=50 for the number of trees and contamination=0.02 for the expected proportion of anomalies. Random_state=42 was used for reproducibility. The model classified the observations as either normal (1) or anomalous (-1), thus aiding in the isolation of outlier patterns from within the spatial configuration of the drug-related death data, similar to the One-Class SVM.

Local Outlier Factor (LOF)

Local Outlier Factor (LOF) is a density-based approach that identifies anomalies by comparing the local density of each data point with that of its neighbors (Breunig et al., 2000). Unlike global anomaly detectors, LOF can identify subtle, context-dependent outliers and is therefore highly suitable to datasets with locally varying densities (Kriegel et al., 2009). This makes it a useful instrument in detecting weak geographic anomalies in drug-related mortality data, such as unexpected clusters in otherwise low-incidence areas. These may represent emerging drug-use hotspots or local trafficking routes (Campos et al., 2015).

These same geographical attributes (drug_outlier_geo) were preprocessed and trained. The LOF model was initialized with n_neighbors=20 to define the size of the neighborhood, contamination=0.03 to define the proportion of anomalies expected, and novelty=False for unsupervised anomaly detection. The model marked outliers as (-1) and inliers as (1), enabling the identification of local geographic outliers that would not be apparent with global models.

All three of these complementary approaches together present a strong paradigm for detecting spatial outliers in drug mortality data. By utilizing One-Class SVM's non-linear boundary detection capability, Isolation Forest's recursive partitioning ability, and LOF's local density variability sensitivity, the research offers complete and correct detection of geographic anomalies and their potential public health and policy relevance.

Evaluation and Validation of Models

The evaluation models—classification, clustering, and anomaly detection—were assessed through quantitative metrics as well as qualitative interpretation for the holistic understanding of their use in the drug-related overdose.

Classification Model Discussion

In the models tested for classification support vector machine (SVM) with an RBF kernel was the best-balanced and most reliable. With a 92.87% overall accuracy, it displayed almost a strong ability to generalize itself without overfitting as seen in Random Forest (98.22%) and KNN (99.97%) models exhibiting overfitting with minority class performance. Its greatest advantage lies in its ability to handle imbalanced datasets and nonlinear relationships during hyperparameter tuning (C and gamma) and class weights adjustment.

Although Random Forest worked perfectly and gave useful feature importance ideas about dominating class predictions, the model had been leaking due to the very high correlation between the input features and target variable (for example, age group encoded). KNN also had quite impressive performance metrics but could not generalize; it worked like memorization and performed poorly on minority classes and high-dimensional datasets. Execution time comparisons also showed that KNN was the fastest, while the computation time of SVM justified enough its reliability in prediction over various class distributions.

Clustering Model Discussion

For unsupervised learning, HDBSCAN and KMeans were employed to determine behavioral and demographic patterns in drug mortality. While KMeans was satisfactory with a Silhouette Score of 0.3276 and Calinski-Harabasz Index of 1913.19, it was constrained by being able to accommodate only spherical clusters and requiring predefinition of the number of clusters. HDBSCAN, on the other hand, yielded more meaningful clustering results with a better Silhouette Score of 0.5802 and greater intra-cluster similarity and inter-cluster separation. Its noise robustness and ability to handle non-convex cluster shapes made it particularly well-suited to real data with complex spatial and demographic arrangements.

Visualizations using UMAP and cluster-specific heatmaps also established that HDBSCAN identified more significant clusters, particularly in data with irregular patterns of drug use. Although KMeans had more distinct separations in PCA-reduced space, it could not deal with noise, which is inherent in overdose data. The strength of HDBSCAN was its capacity to filter out noise points and concentrate on cohesive, high-density patterns.

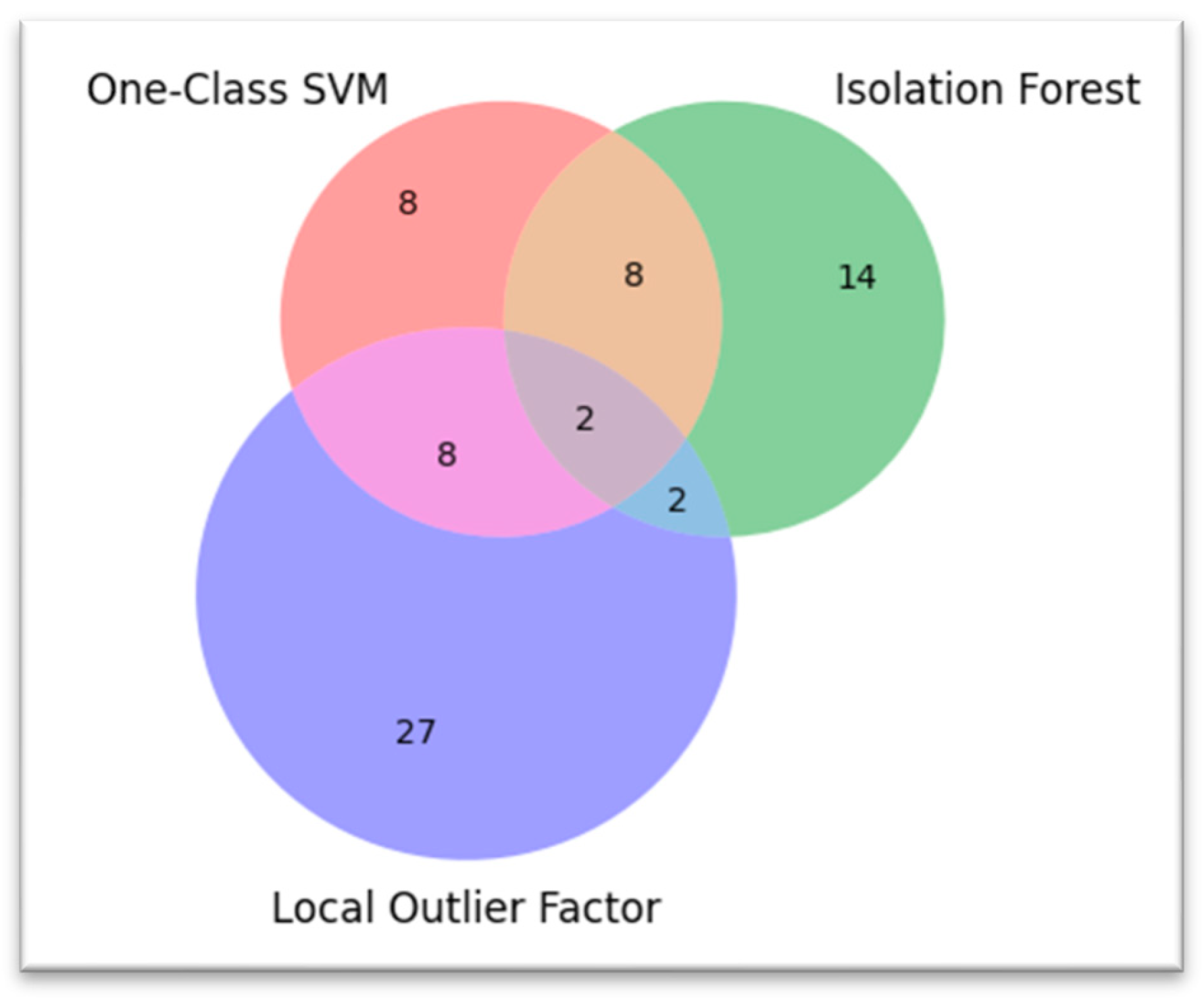

Anomaly Detection Model Discussion

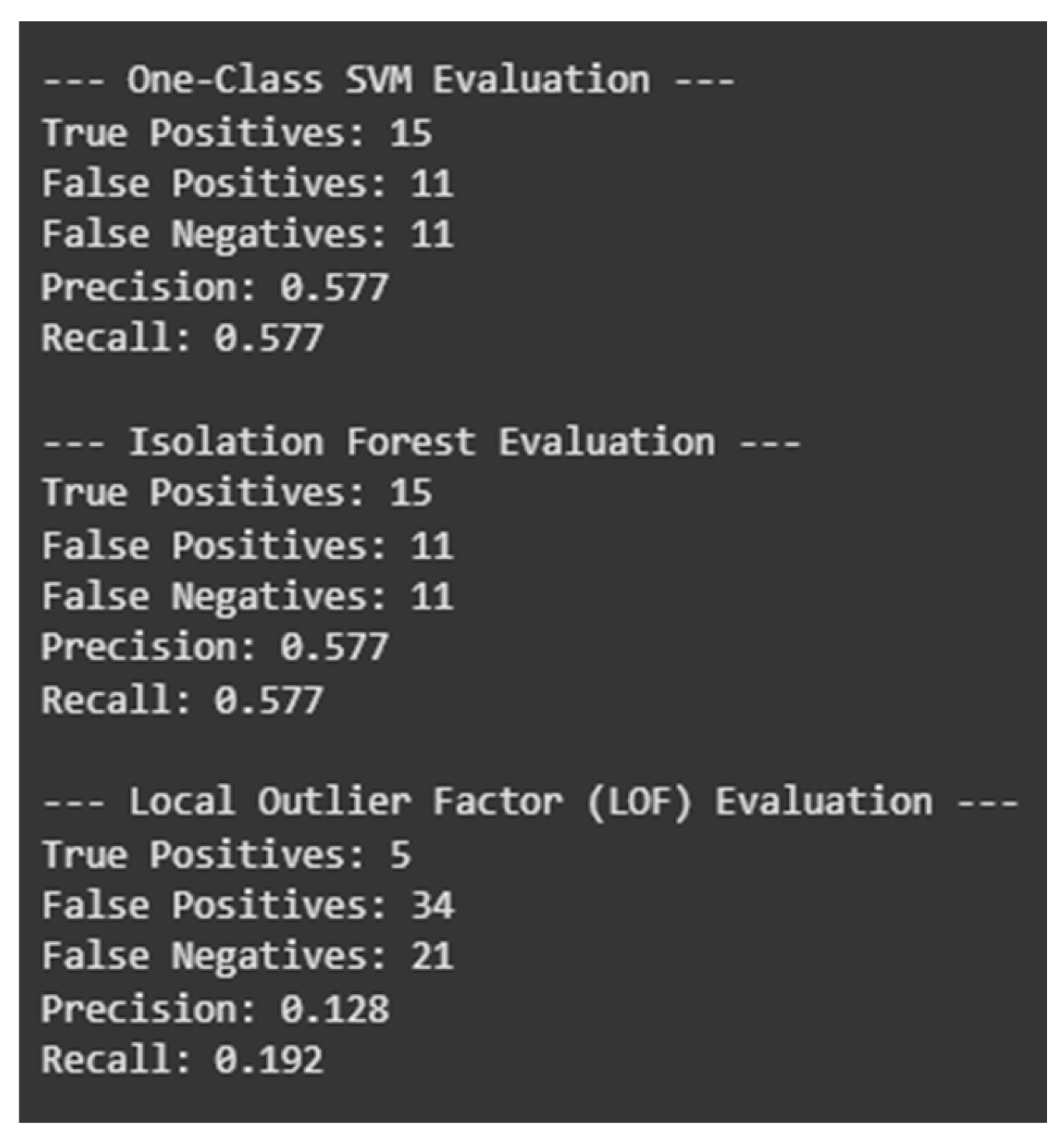

Anomaly detection models were tested on their ability to identify outliers in geographic distance—i.e., the distance between home and location of death. Three methods were compared: One-Class SVM, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor (LOF). They were compared against a statistical baseline using IQR and 3-Sigma methods.

One-Class SVM and Isolation Forest performed similarly, each identifying 26 geographic anomalies and achieving a balance between true positives and false positives (15 TP, 11 FP). LOF was most sensitive, as it detected the most anomalies (39), but this sensitivity was at the expense of more false positives (34 FP, 5 TP only), reducing its precision. Although LOF's sensitivity is useful for exploratory analysis, the lack of precision makes it less effective for real-time anomaly detection where false alarms are costly.

Geographic outlier plots indicated how these anomalies relate to potential drug trafficking pathways or medical response deserts. Flags on long-distance overdose fatalities—often from out-of-state—indicated systemic issues such as drug tourism or structural barriers to timely medical care. SVM and Isolation Forest yielded more precise, stable anomaly flags and are therefore preferable in contexts where accuracy is paramount.

VISUALIZATION FOR COMPARISON OF ANOMALIES BY EACH MODEL:

When comparing the performance of anomaly detection, the results demonstrate that One Class SVM and Isolation Forest achieve a reasonable balance between detection power (false negative rate) and precision (false alarm rate) with 15 true positives (TP) and 11 false positives (FP) for this dataset. However, the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) has a very high sensitivity and a tendency to significantly over-detect anomalies, along with a very low precision (5 TP and a respectable 34 FP). These results demonstrate the advantages of One-Class SVM and Isolation Forest in terms of accuracy and balance of reliability. They also demonstrate that, despite the fact that LOF detection covers a more general spectrum with less precision, the bridge constructed in each feature space connects these combinations [

28,

29].

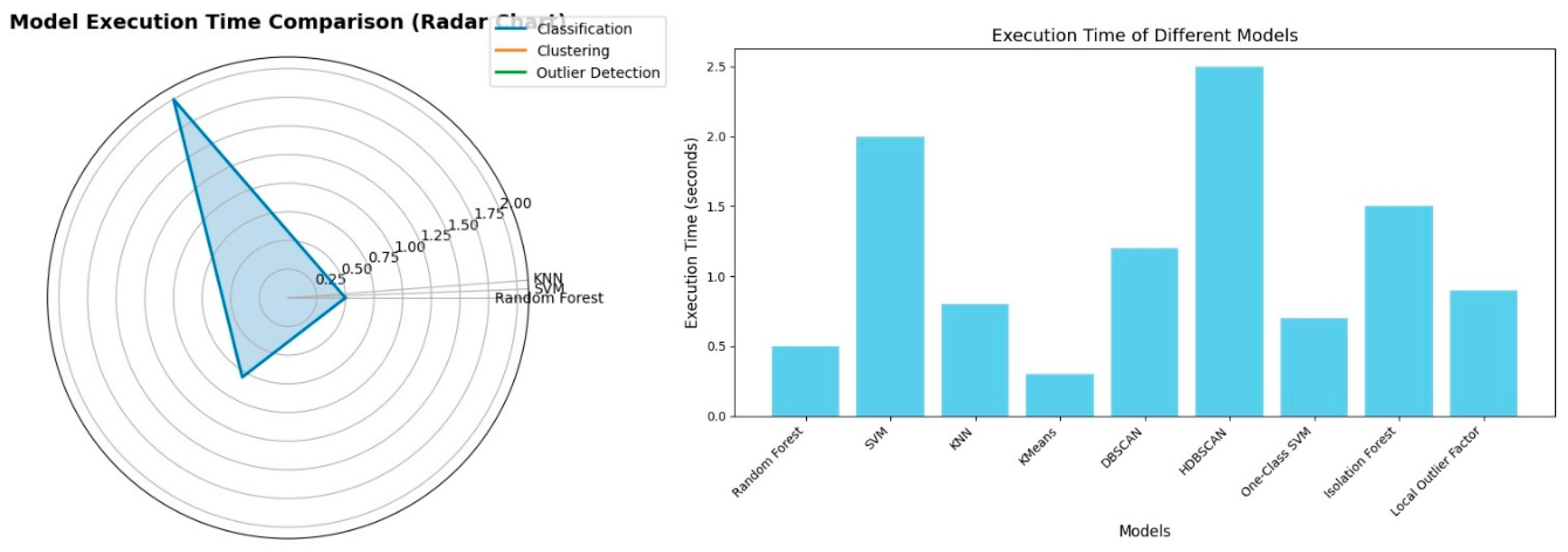

EXECUTION TIME COMPARISON

These two charts demonstrate the comparison of the execution times of different data mining algorithms. The radar chart shows the representation of the three classification algorithms-KNN, SVM, Random Forest.

Figure 4.

Execution Time Comparison.

Figure 4.

Execution Time Comparison.

The bar chart illustrates a straightforward comparison of the execution times of all the algorithms. We can directly interpret from the chart:

This direct comparison helps in determining the computational costs of all these algorithms, being crucial parameter for efficient modelling.