1. Introduction

Sport programs have long been expected to prevent crime [

9] and juvenile delinquency [

17], by developing protective factors in youth violence, antisocial behaviors, and psychological well-being [

10]. Routine Activity Theory [

5] had highlighted the effects of reliable guardianship on crime prevention, where structured supervision received from sport programs[

16] for young children and adults, or a routine social network maintained through footfall clubs [

7] activities, contributed significantly to the reduction and prevention of youth crimes in urban areas. However, major sporting events, such as football matches in the Premium League, are instead more related to the increase of violent crimes [

2]. The double sided effects of sports on crimes from empirical literature had led to this research impetus on exploring the real-life date in London, hence to better suggest policing strategies and practices based on the generated evidence.

2. Background

On 9 April 2025, the Mayor of London announced that the England-first Violence Reduction Unit, VRU, is investing a further £1 million to provide sports and physical activities to young people at the highest risk of being affected by violence in London[

11]. This initiative, as one of the actions in response to the deterioration of knife crime and violence problems in England over the past decade [

1], especially the over 21% increase in knife or sharp instrument incidents in London between 2022 and 2023 [

14], has been informed of the violence-deterrent effects of regular sports programms in urban context. College of Policing published a review report in 2023 [

6] on the positive influences of sports on crime prevention and reduction of reoffending, which showed improved individual attitudes towards offending and anger control. Community based sport activities such as sport clubs, had been increasingly recognised as crime reduction and prevention tools. Based on the theory of social cohesion, team sports can strengthen social bonds through better self-regulation, therefore reducing potential aggressions [

3], and improving aspirational goals for marginalised young people [

12]. Sport clubs can also provide job skills, scholarships, and legitimate economic alternatives to crime.

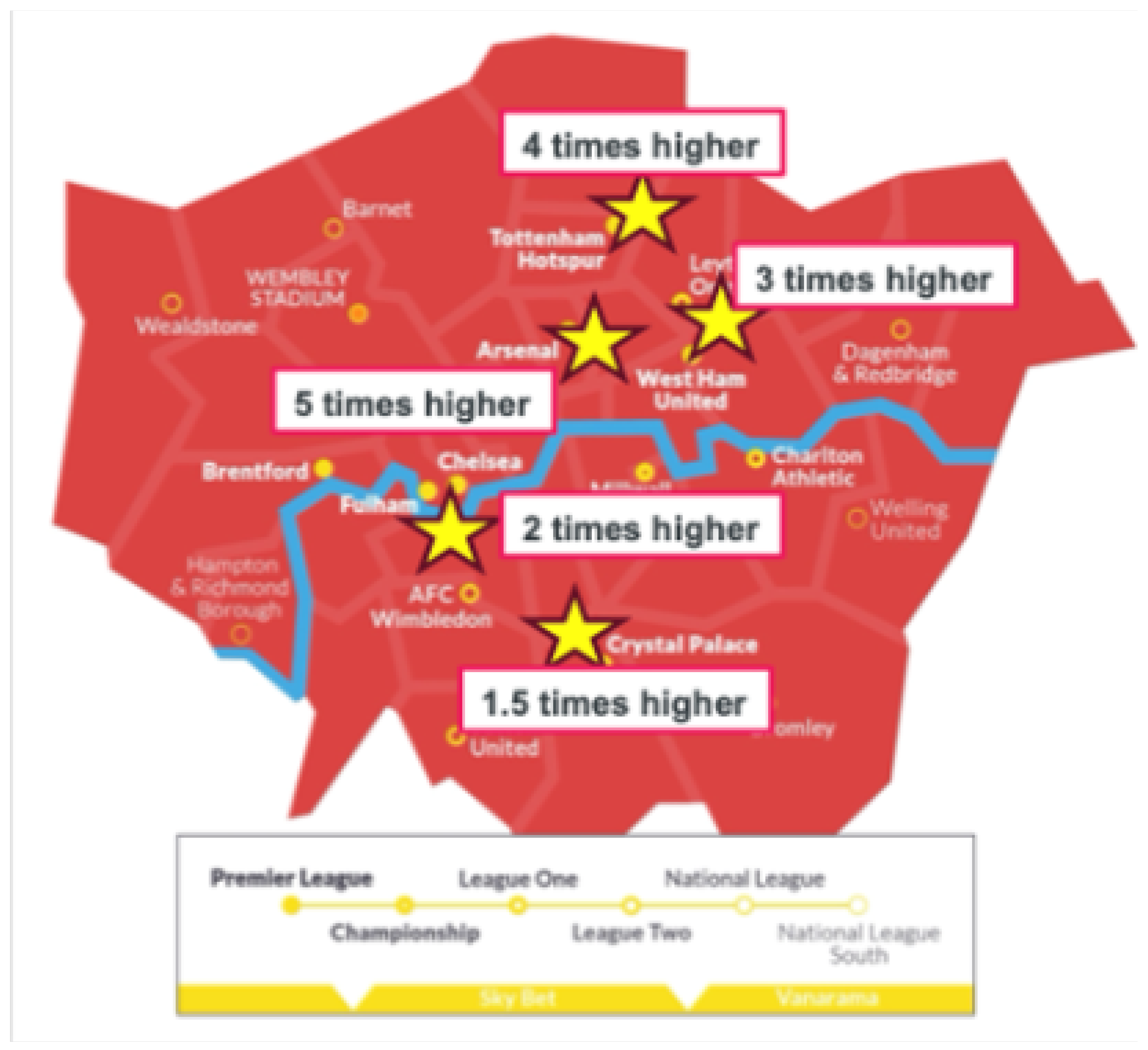

Major sporting events and large public gatherings (

Figure 1) have complex and multifaceted effects on urban crime; especially with the highlight increases in disorderly conduct, theft, and violence [

15]. The debates centred around the potential volatile environment sparked by heated emotions and alcohol, as well as the spikes of domestic violence after unexpected loss results [

4]; as well as the potential crime displacement incurred by major events, either spatially or temporally. For example, the short-term sparks of anti-social behaviors and crimes around football stadiums in England cities [

8]. But the displacement intensity may vary by crime types, for example, the increased property crimes near stadiums hosting matches at 7% per additional 10,000 supporters left under-protected [

13]. Although decades-long discussions on the diverse two-sided effects of sports on violence and crimes had been well testified by criminological and sociological research, there is a lack of systematic validation to map the holistic associations between crime levels, possible reduction effects and sports infrastructures or sports-related events, in presentation of solid data-driven evidence towards the policing practioners.

These lead to the research to explore influences of sports on expressive crimes (e.g. violence) with data-driven evidence. To fulfill the aim, following objectives are expected to be achieved, hence to better prepare the foundation for future real-life applications of predictive policing.

Objective 1: Map out the regional associations between London’s sport clubs and expressive crimes.

Objective 2: Explore crime changes pre- and para- major football events held in selected case study stadiums both spatially and temporally.

Objective 3: Investigate the driving mechanism for such changes with case study.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a multistage analytical framework to explore the relationship between sports-related activities and expressive crime in London, in order to realise research objectives, respectively.

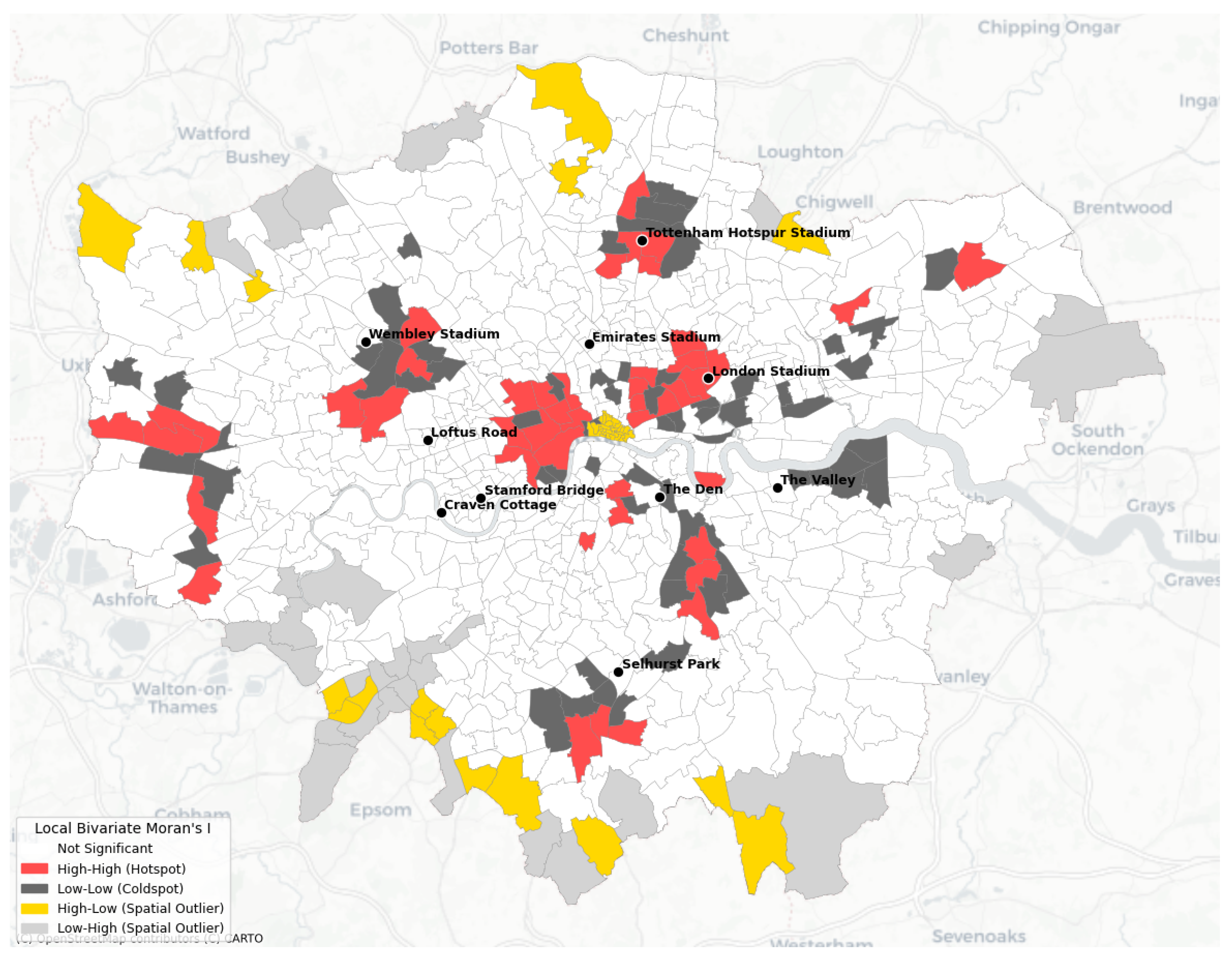

Firstly, local bivariate Moran’s I mapping was adopted to visualise the spatial associations between expressive crime rates and sports clubs among London wards, in receiving spatial hotspots where they co-occur at high intensities.

Secondly, a case study on sport events’ influences of expressive crimes had been conducted around Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, with its nearest rail station Northumberland Park as the observing point. Sankey diagrams and seasonal trend decomposition using Loess (STL) were deployed, to visually compare crime patterns between match days and non-match days, so can validate the temporal association between football events and expressive crime surges. To quantify the causal effect of match days, a Difference-in-Differences (DiD) regression model was applied across wards within the H district, as specified below:

where

denotes the number of expressive crimes in ward

i at time

t,

is a binary indicator for match days,

identifies the Northumberland Park rail station as the treated ward,

are covariates,

and

are ward and time fixed effects, and

is the error term.

Finally, to further investigate the underlying mechanisms driving spatial-temporal variations of expressive crimes, a Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression (GTWR) model was employed, since its taking into account of both spatial and temporal heterogeneity, capturing the dynamic and localised effects of mobility changes around the target venue on expressive crime. The GTWR model can be expressed as:

where

represent the spatial and temporal coordinates of observation

i,

are location- and time-specific coefficients, and

are explanatory variables. Through this integrative approach, the study systematically examined both spatial clustering and the temporal dynamics of expressive and violent crimes, providing a solid basis for understanding the localised impacts of sports clubs and stadium events.

4. Results

4.1. Sport Clubs & Expressive Crimes in London

The bivariate Moran’s

I map was utilized to illustrate spatial relations of expressive crime and sports clubs (

Figure 2), where the red areas were hotspots experiencing high levels of expressive crime and a denser distribution of sport clubs. These hotspots were mainly concentrated in central London and the vicinity of major sports stadiums (

Figure 1).

The hotspot clusters in central London encompassed areas in the south of Westminster and Camden Town, while both districts are major tourist destinations and host to a rich variety of community sports facilities. Apparently, these hotspots were likely to be the result of multiple factors, such as the home of London landmarks and cultural infrastructure, attractions for high tourists mobility, and clusters of social gathering places and restaurants. Other hotspots observed in

Figure 3 mainly surround major sports stadiums, for example, the London Stadium (home ground of West Ham United FC), and Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, which further extended into neighbouring towns such as Bow, Homerton and Bethnal Green. Such a pattern indicates a higher exposure of the denser residential population to the presence of extensive sports facilities, which can pose increased risks of interpersonal frictions or street-level conflicts.

Another eye-catching hotspot cluster is around the Tottenham Hotspur FC Stadium in North London. Instead of diffusing into neighbouring towns, this group clearly bordered the areas surrounding Tottenham Central in Haringey borough, hence it is featured as an “event-driven space”. It is assumed that during major sporting events, crowd mobility spikes together with heightened emotional behaviors, which then are thought to trigger the increases of expressive crimes. In addition, such crimes were not limited within the event venues, but spread to surrounding areas. Therefore, the observed cluster in Haringey borough has served as an ideal case study, to examine the impact of match-day activities onto expressive crimes, especially violence.

4.2. Case Study: Stadium Events & Disproportionate Crime Changes

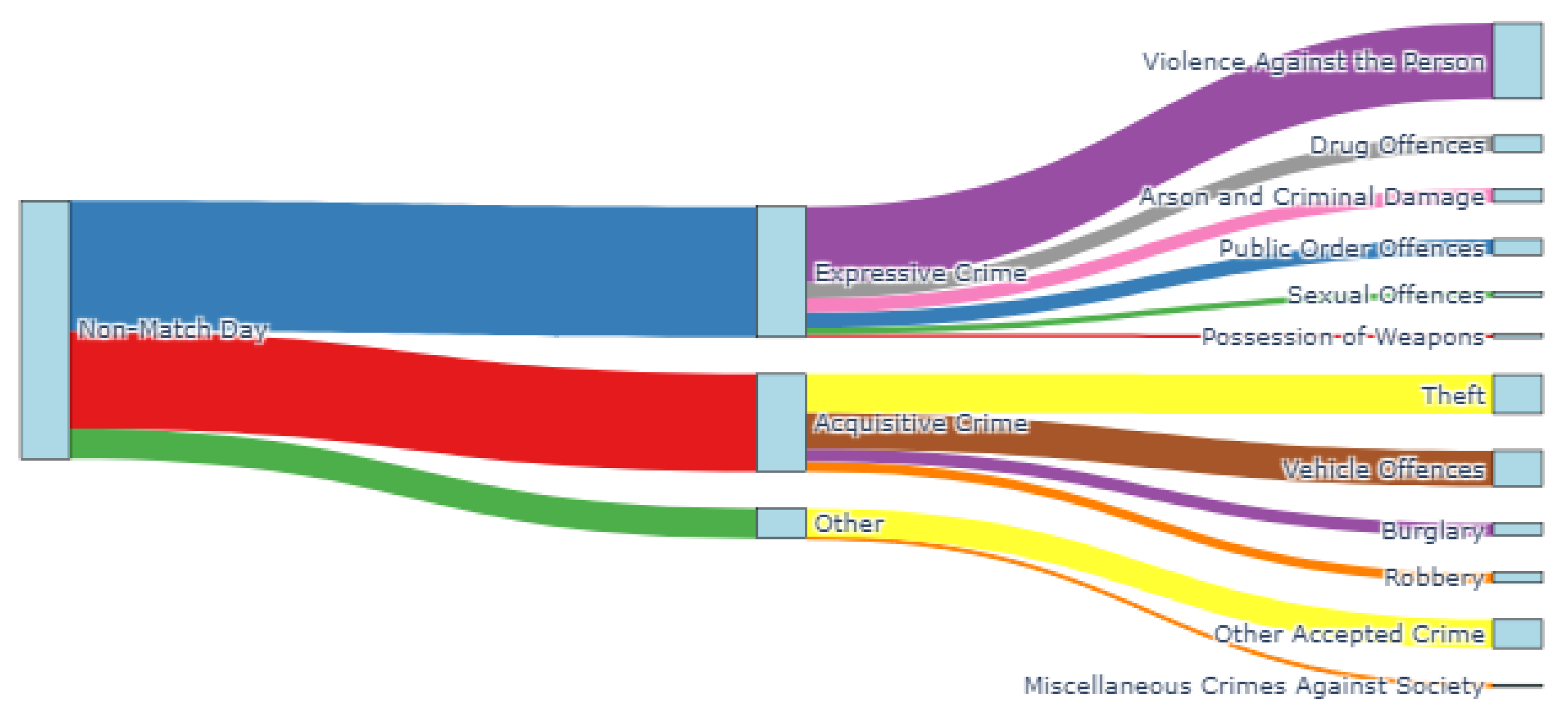

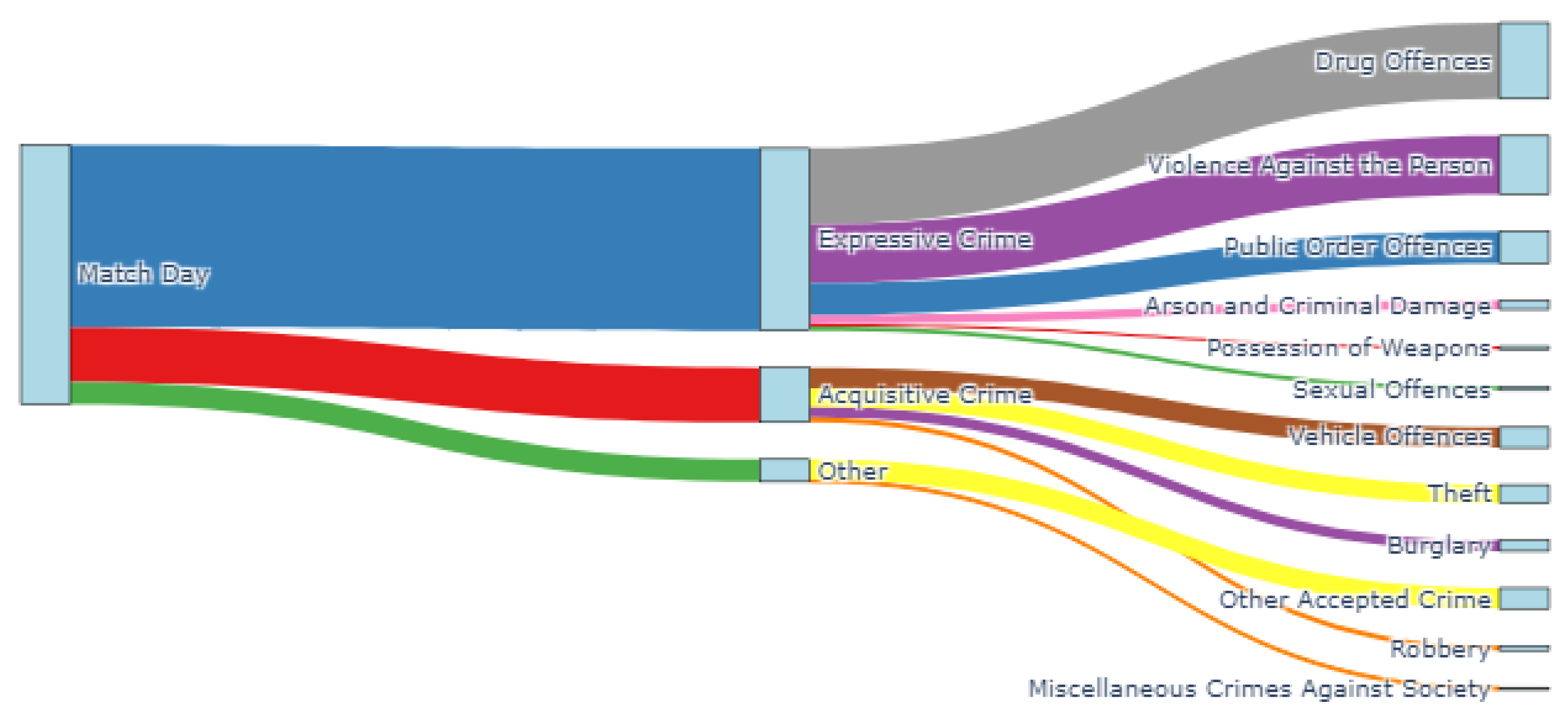

In light of above exploration, Haringey borough had been selected as a case study to investigate the potential impacts of football matches on local crimes. The exploratory analysis that compared types and volumes of recorded crimes between match days and non-match days had been mapped out (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), taking the home town of Tottenham Hotspur FC Stadium, Northumberland Park, as the research target area.

Figure 3.

Crime Type Distribution on Non-Match Days in Northumberland Park.

Figure 3.

Crime Type Distribution on Non-Match Days in Northumberland Park.

Figure 4.

Crime Type Distribution on Match Days in Northumberland Park.

Figure 4.

Crime Type Distribution on Match Days in Northumberland Park.

The Sankey diagrams in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrated crime compositions by type in the town of Northumberland Park, on non-match days and match days, respectively. In non-match days (

Figure 3, acquisitive and expressive crimes took relatively equal proportions, whilst violent crimes accounted for the vast majority of expressive crimes, at 29.3% for all crimes, and other expressive crime types contributed only marginally; it then followed by theft and vehicle crimes from acquisitive crimes, accounting for 15.1% and 13.8% respectively. In match days (

Figure 4), expressive crimes increased to about 70.3% of all crimes, where the top three types are: drug offences increased dramatically to 29.3%, followed by violent crime (22.6%) and public order offences (12.4%). In contrast, the pattern of acquisitive crimes remained comparatively stable regardless of the match days.

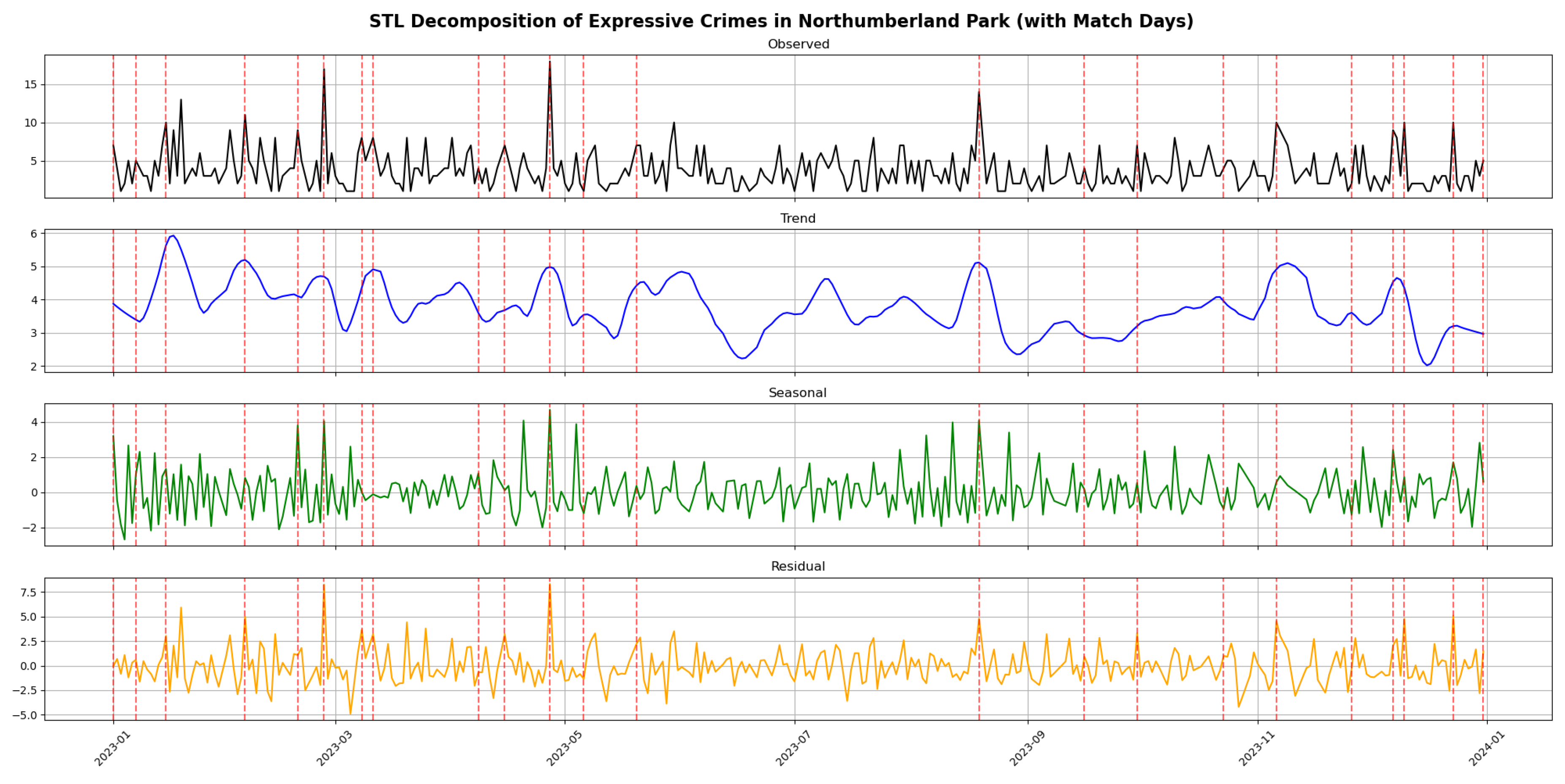

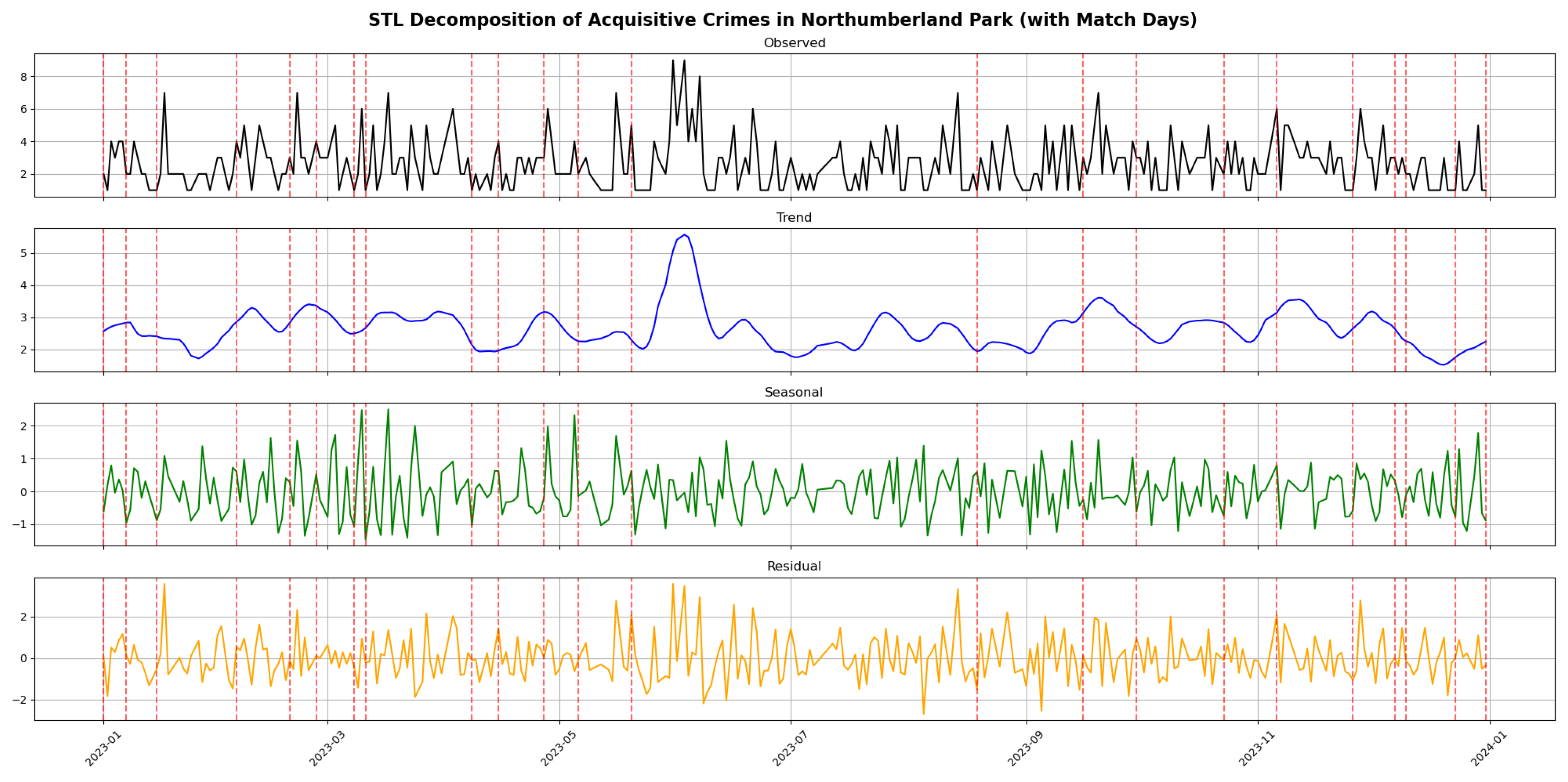

The temporal patterns for the impacts of match days had been validated through STL decomposition, with red dashed lines indicating match days (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7). The trend for expressive crimes in Northumberland Park (

Figure 5) obviously presented positive outliers on match days, that is, there was a strong association between match days and the surges of expressive crimes around the stadium. For example, on 26 February (home match day for Tottenham Hotspur vs Arsenal) and 27 April (home match day for Tottenham Hotspur vs Manchester United), when the historical rivalry teams are having matches. In contrast, acquisitive crimes (

Figure 6) did not exhibit abnormal changes on the days of matches, further confirming the pattern observed in

Figure 6 that the days of matches did not significantly affect acquisitive crimes.

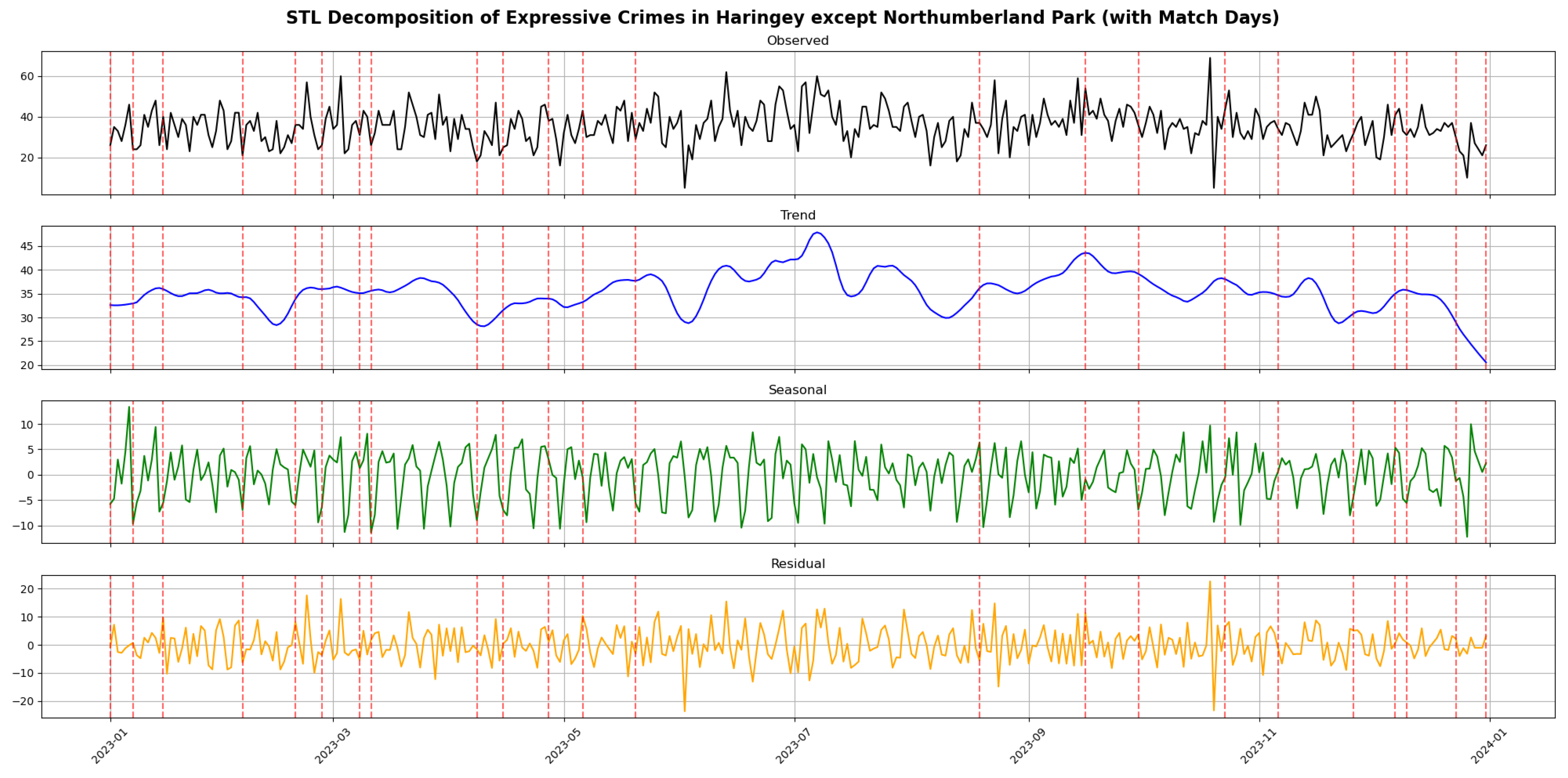

To better understand the changes of crime in the whole Haringey borough, similar STL composition had been conducted for other towns in the borough excluding our target town Northumberland Park. It highlighted (

Figure 7) rare significant association between expressive crimes and match days for other "far-away" towns, instead it kept apparent seasonal trends as non-match days, with the indication that the influence of football matches on expressive crimes did not spill over into neighbouring areas beyond Northumberland Park.

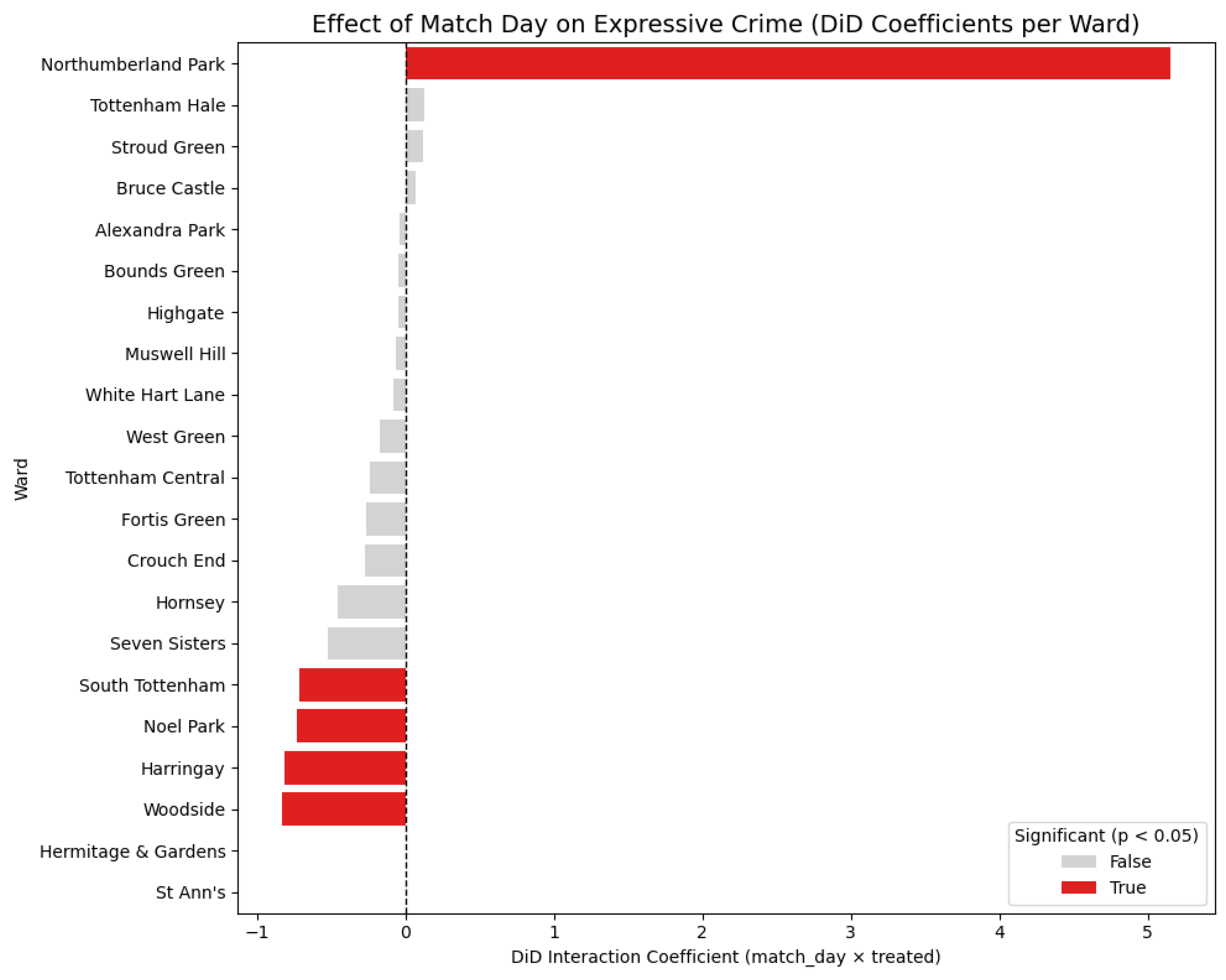

To highlight the aforementioned time series observations,a difference-in-differences (DiD) regression analysis was applied to compare such associations among towns in Haringey borough, with the results presented in

Figure 8. In the bar chart, each bar represents an interaction coefficient between a specific town and the observational match days. Notably, the coefficient for Northumberland Park was positive and substantially higher than other areas, hence it is proved to solidate the argument that match days were driving expressive crimes high dramatically in the vicinity of study area. There were also several towns far from the target area, Northumberland Park, such as South Tottenham and Harringay, that exhibited significantly negative interaction coefficients. This indicated potential crime displacement effects, or alternatively reflected the deterrent impacts of increased police presence around the stadium on match days with further influences on other areas’ crime reductions.

4.3. Driving Mechanism

To better address the research objective of investing the driving mechanism of such association between match days and expressive crime changes, Geographically Temporal Weighted Regression (GTWR) model was utilisied and received a high value of 0.83.

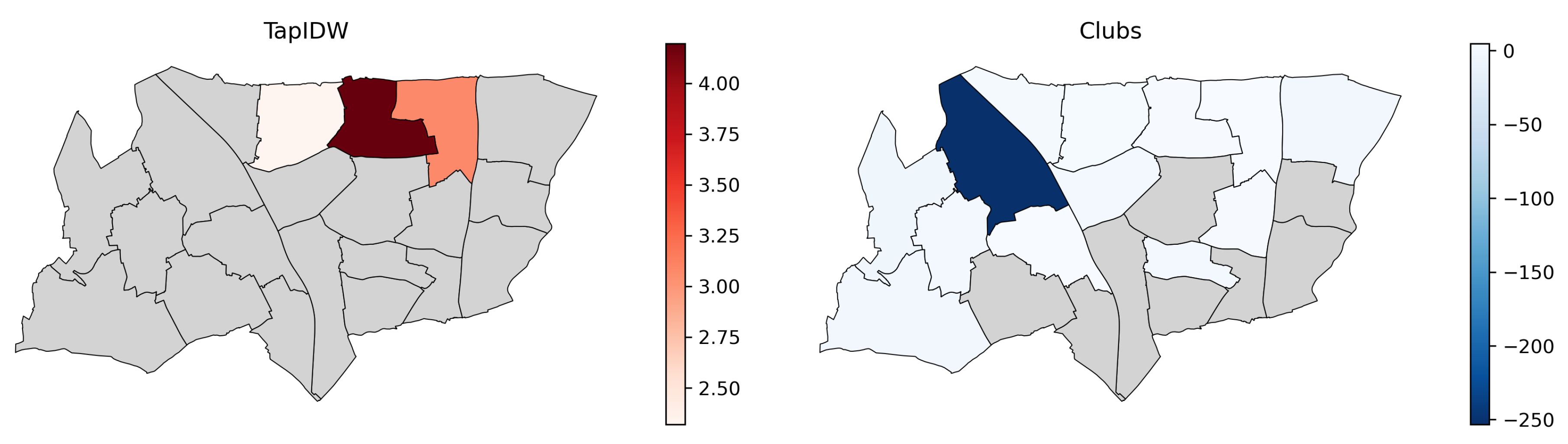

Figure 9 maps the spatial pattern of the average coefficients, calculated by the GTWR model, for the intensity of mobility in the underground tube station (tap-in activity, TapIDW) and sports clubs (Clubs) against expressive crimes among towns.

The left of

Figure 9 captured the relation between tube passengers’ mobility and expressive crimes, in return with the three towns in the North, Woodside, White Hart Lane, and Bruce Castle, carried greater influences from mobility increases to the elevated risks of expressive crimes. For example, the coefficients were highest in Bruce Castle and White Hart Lane areas, which are either close to Tottenham Hotspur Stadium or close to the nearest underground stations to the stadium. This finding proved the hypothesis that, areas surrounding this stadium were highly sensitive to variations in mobility, so that crowd surges during match events were one of the key drivers of local expressive crime spikes. The right figure managed to map the relations between local sports clubs and expressive crimes throughout the observation period. It demonstrated a deterrent effect on expressive crimes among most towns in Haringey borough, particularly those in the southwest, such as Alexandra Park.

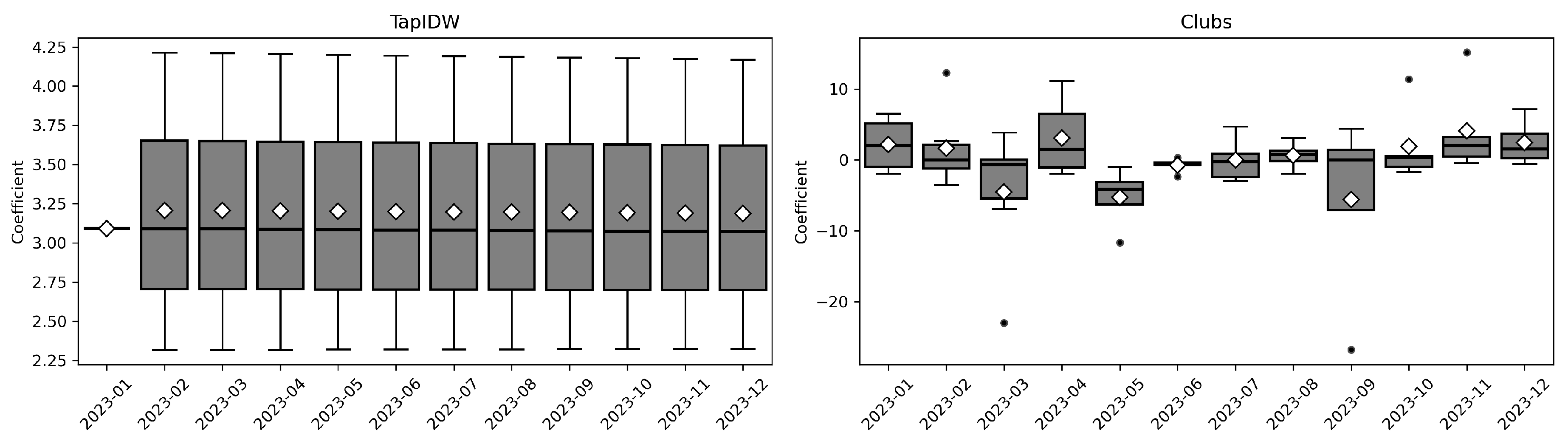

Figure 10 utilised boxplots to compare the temporal dynamics of the GTWR coefficients for both variables. It could be spotted that the impact of underground passengers’ mobility activity kept relatively constant impacts on expressive crimes over time (left), whilst sports clubs’ influences varied by season. The density of sports clubs among Haringey borough’s towns slightly drove expressive crimes higher in the winter months (November to February), which was assumed owing to the reduction of fewer outdoor sport activities since the cold weather and Christmas holidays.

In Spring (March–May), the influences shifted significantly over time. For example, the crime deterrent or prevention effects (negative value) were significant in March, thanks to the increases of organised physical sports activities which were thought to be capable of mitigating conflicts. Longer school holidays in April have been associated with a resurgence of positive association (right of

Figure 10), when a rise in mass gatherings may increase the likelihood of expressive violence incidents. The associated data returned to negative in May, suggesting that back-to-regular sports club activities can effectively contribute to the reduction of expressive crimes.

During summer (June–August), sports clubs generally exerted a suppressive effect on expressive crimes, even during school holidays, through the increased participation of organised outdoor sports activities, to optimise the unstructured time that might otherwise lead to criminal behaviours. In fall (September–October), when school term begins, the negative influence of sports clubs became more pronounced, especially in September exhibiting the strongest suppressive effect. This aligns with empirical studies on the positive impacts of sports activities on crime prevention through the resumption of formal education and structural social participation.

5. Discussion

The spatial hotspots of expressive crimes and sports clubs in London were featured by multiple profiles, such as the home of London landmarks and cultural infrastructure, attractions for high tourists mobility, and clusters of social gathering places and restaurants, for example, major sports stadiums and parks. This pattern indicates a higher exposure of the denser population to the presence of extensive sports facilities, which can pose increased risks of interpersonal friction or street-level conflicts. In particular, “event-driven space”, such as the region surrounding Tottenham Central in Haringey borough, is assumed to experience spikes in crowd mobility during major sporting events, together with increased emotional behaviors that are thought to trigger the increases of expressive crimes. The temporal analysis through STL decompostion further validated the assumption of match-days influences on expressive crimes around major stadiums, for example the areas around Totthenhamd Hotspur stadium in Haringey borough, which could be clearly visualised by DID regression analysis.

On the other hand, sports clubs had been proved to exert crime deterrent effects in Haringey borough during school terms including half-term holidays, by applying GTWR model, through increases of organised physical activities; but the resurgence of expressive crimes during long school holidays, such as summer holiday and Christmas holiday, suggesting the positive effects of sports clubs on crime reduction and prevention, through structural social participation alongside with the regular school education.

6. Conclusions

This study conducted a preliminary examination of the spatial and temporal patterns of expressive crimes in association with sports clubs and stadium venues in London, with a particular focus on the case study stadium in Haringey borough. The results revealed that hotspots of higher expressive crimes and denser sports clubs were predominantly located in central London and around major stadiums, shaped not only by the availability of sports facilities but also by high population mobility driven by multi-functioning landuses.

The case study of Northumberland Park town further highlighted the disproportionate rise in expressive crimes -particularly violent crime - on football match days, with evidence from both time series decomposition and difference-in-differences analysis, indicating a strong localised impact around Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. The GTWR model provided information on the underlying dynamic mechanisms driving expressive crime patterns. Mobility changes measured by underground tap-in activity demonstrated consistent crime-driving influences over time, whereas the availability of sports clubs exhibited a seasonal dynamic, from limited driving effects during winter holidays to strong crime deterrent effects during late spring and fall. Although preliminary results from such predictive modeling efforts were proved to be effective, given the current complexity of the relationships between urban crimes and multiple explanatory variables, advances of machine learning and deep learning models offered a promising approach to capturing crimes’ underlying nonlinear and unstructured patterns. Future research will aim to develop more precise crime forecasting models combined with explainable AI techniques, to capture complicated nonlinear interactions between urban crimes and environmental explanatory factors, but most importantly to enhance the interpretability of advanced model outputs, and hence to better inform evidence-based crime prevention policing strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Li, Y., Broca, S. and Patel, Z.; methodology, Wang, R. and Li, Y; software, Wang, R.; validation, Wang, R., Li, Y., Patel, Z. and Sahota, I.; formal analysis, Wang, R. and Li, Y.; investigation, Wang, R., Li, Y. and Broca,S.; resources, Li, Y. and Broca, S.; data curation, Patel, Z. and Sahota, I.; writing—original draft preparation, Li, Y. and Wang, R.; writing—review and editing, Li, Y. and Broca, S. ; visualization, Wang, R. and Li, Y. ; supervision, Li, Y.; project administration, Li, Y.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon requests.

Acknowledgments

The study acknowledge support of data from Haringey City Council and London Sport.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STL |

Seasonal Trend decomposition using Losse |

| GTWR |

Geographically Temporal Weighted Regression |

| DID |

Difference-in-difference |

References

- Allen, G., Wong, H. 2025. Knife crime statistics: England and Wales. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04304/SN04304.pdf.(accessed on 28 April, 2025).

- Andres, L., Fabel, M. and Rainer, H. How much violence does football hooliganism cause? Journal of Public Economics, 2023, 225: 104970. [CrossRef]

- Bruner, M. W., McLaren, C. D., Sutcliffe, J. T., Gardner, L. A., Lubans, D. R., Smith, J. J., and Vella, S. A. The effect of sport-based interventions on positive youth development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2021, 16 (1): 368–395. [CrossRef]

- Card, D. and Dahl, G.B. Family Violence and Football: The Effect of Unexpected Emotional Cues on Violent Behavior*, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2011, 126(1): 103–143. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.E. and Felson, M. Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. American Sociological Review, 1979, 44: 588-608. [CrossRef]

- College of Policing. 2023. Sports programmes designed to prevent crime and reduce reoffending. https://www.college.police.uk/research/crime-reduction-toolkit/sports-programmes-designed-prevent-crime-and-reduce-reoffending. (accessed on 18 April, 2025).

- Reinhard Haudenhuyse, John Hayton, Dan Parnell, Kirsten Verkooijen and Pascal Delheye. Boundary Spanning in Sport for Development: Opening Transdisciplinary and Intersectoral Perspectives.Social Inclusion, 2020, 8(3): 123-128. [CrossRef]

- Kurland J, Tilley N, and Johnson S. Football pollution: an investigation of spatial and temporal patterns of crime in and around stadia in England. Security Journal, 2017, 31 (10): 665–684.

- Jugl, I., Bender, D. and Lösel, F. Do Sports Programs Prevent Crime and Reduce Reoffending? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Effectiveness of Sports Programs. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 2023, 39: 333–384. [CrossRef]

- Lösel F, Farrington DP. Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. Am J Prev Med, 2012, 43(2): 8-23. [CrossRef]

- Mayor of London. 2025. Mayor announces new £1m sports investment featuring holiday activities for young people at greatest risk of violence. https://www.london.gov.uk/mayor-announces-new-ps1m-sports-investment-featuring-holiday-activities-young-people-greatest-risk. (accessed on 18 April, 2025).

- Morgan, H., Parker, A., and Marturano, N., T. Evoking hope in marginalised youth populations through non-formal education: critical pedagogy in sports-based interventions. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 2021, 42: 307–32. [CrossRef]

- Olivier Marie. Police and thieves in the stadium: measuring the (multiple) effects of football matches on crime. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society), 2016, 179 (1): 273-292.

- Office for National Statistics. 2025. Crime in England and Wales: year ending June 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingjune2023. (accessed on April 28, 2025).

- Rees, D. I. and Schnepel, K. T. 2009. College Football Games and Crime. Journal of Sports Economics, 10(1), 68-87. [CrossRef]

- Shields, D. L., Funk, C. D., and Bredemeier, B. L. Relationships among moral and contesting variables and prosocial and antisocial behavior in sport. Journal of Moral Education, 2018, 47(1): 17-33. [CrossRef]

- Spruit A, van der Put C, van Vugt E, Stams GJ. Predictors of intervention success in a sports based program for adolescents at risk of juvenile Delinquency. International Journal of Offender Therapy Comparative Criminology, 2018, 62(6): 1535–1555. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).