Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

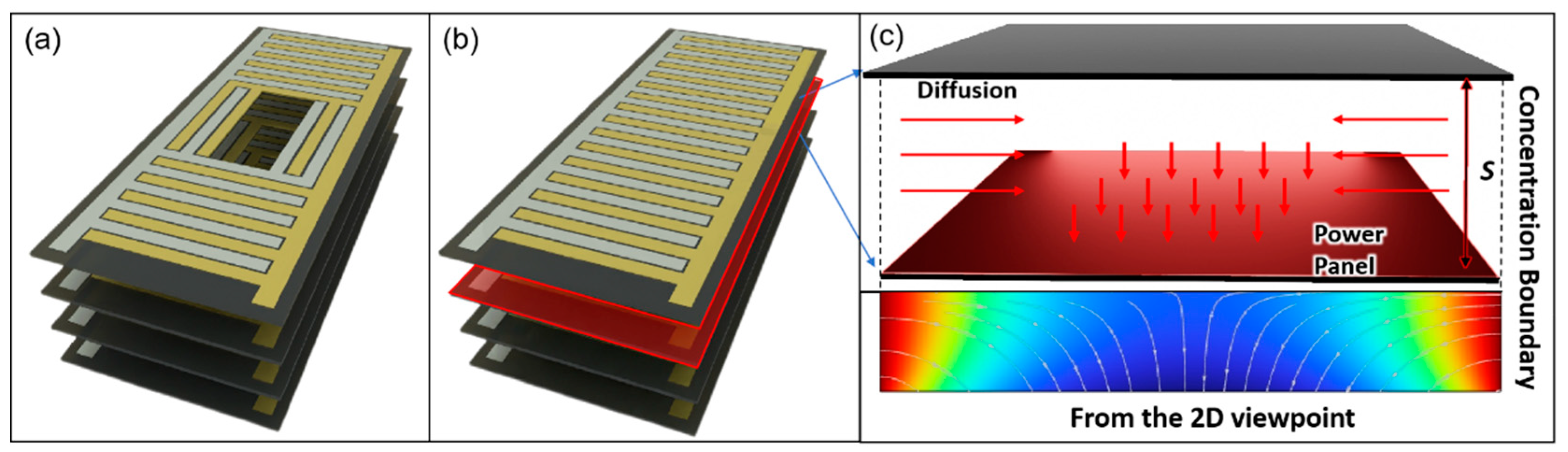

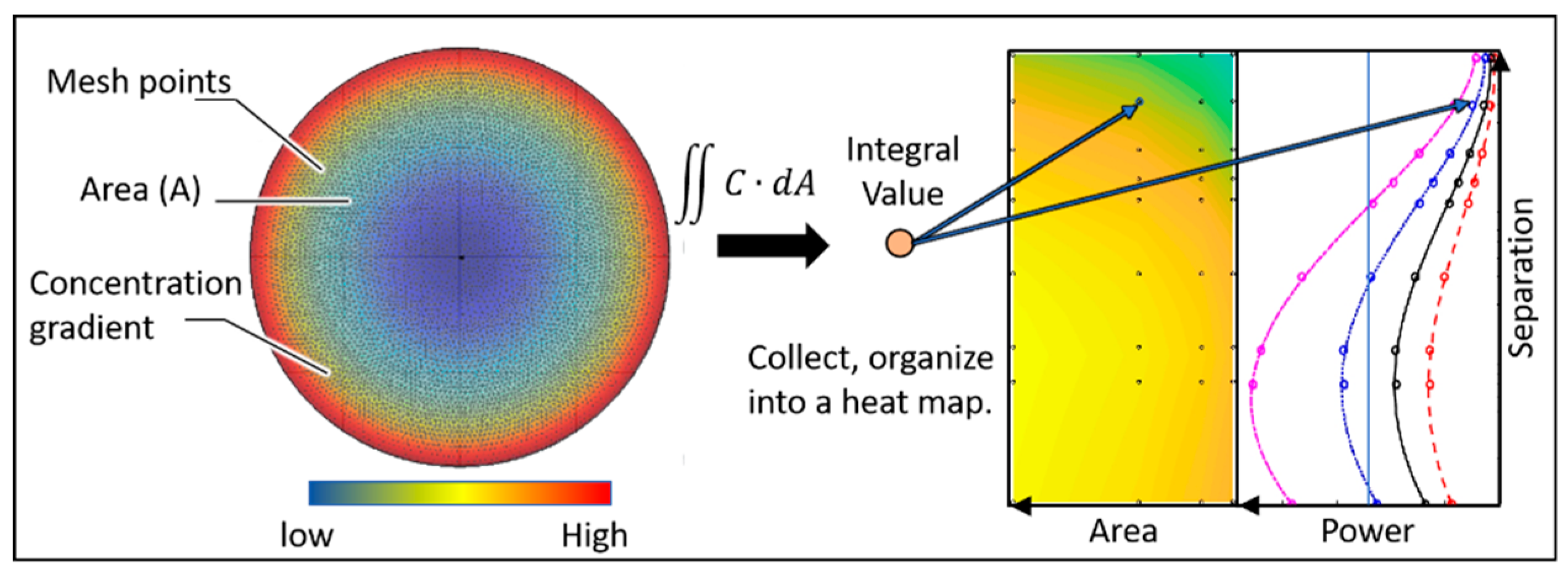

Simulation Set Up

- The simulation surface boundaries were defined with fixed concentrations of glucose (fuel) and oxygen (oxidant), following typical interstitial fluid values: glucose 5 mMol L⁻¹ and oxygen 4.5 mMol L⁻¹

- Since fuel cells operate in vascularized interstitial spaces, a 25–30% loss of glucose and oxygen is assumed. [75-77]).

- the fuel cells are operated at body temperature, 310.15k.

- The mesh grid was set to extremely fine.

- The central holes do not act as sources of glucose or oxygen but serve solely as diffusion pathways.

- Surface reaction rate (RR)

- 7.

- Diffusion

- 8.

- Matlab

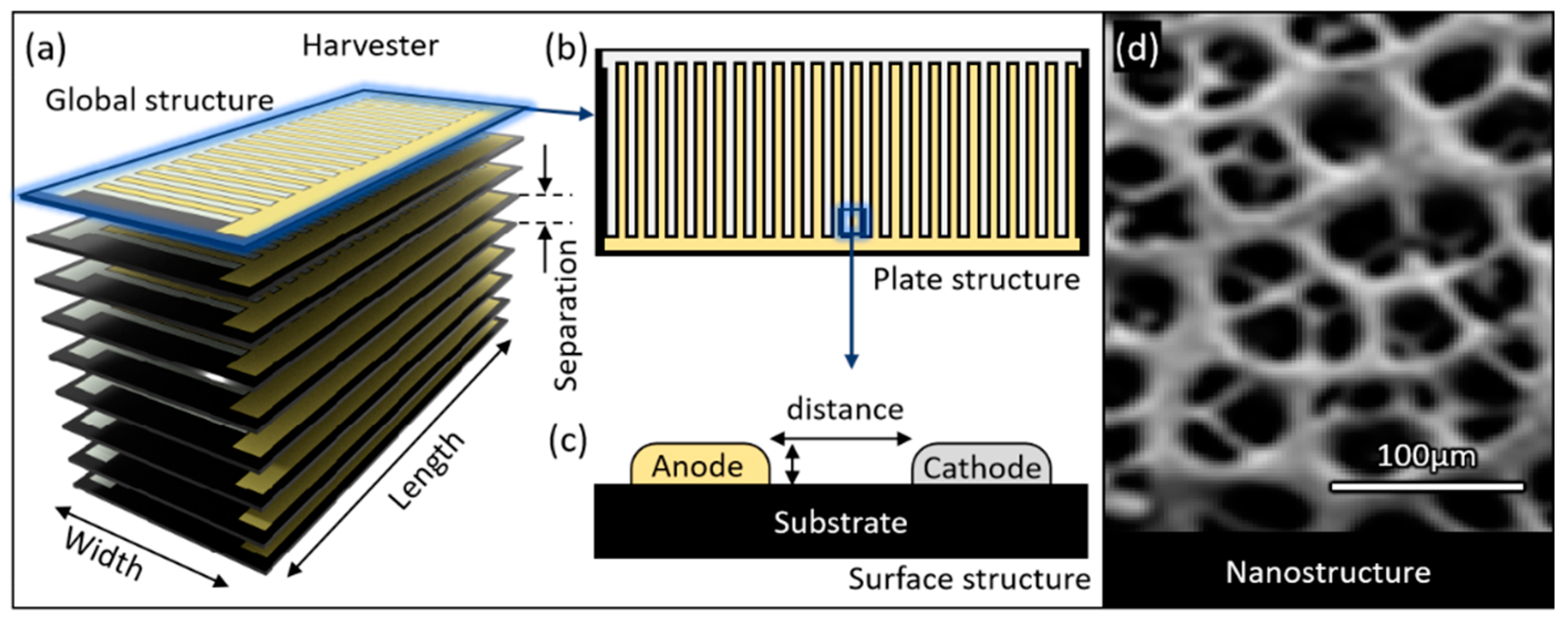

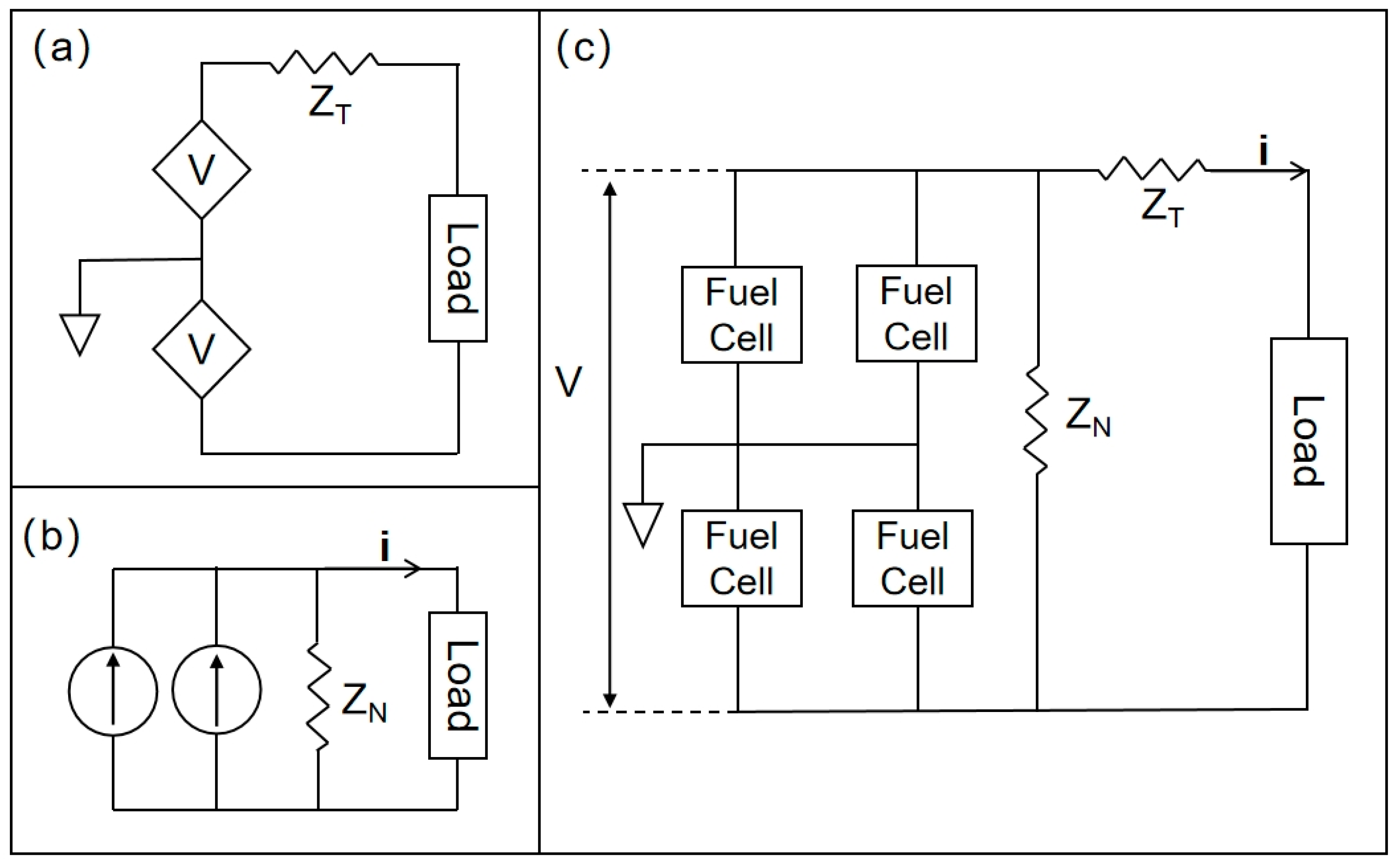

Structural Model

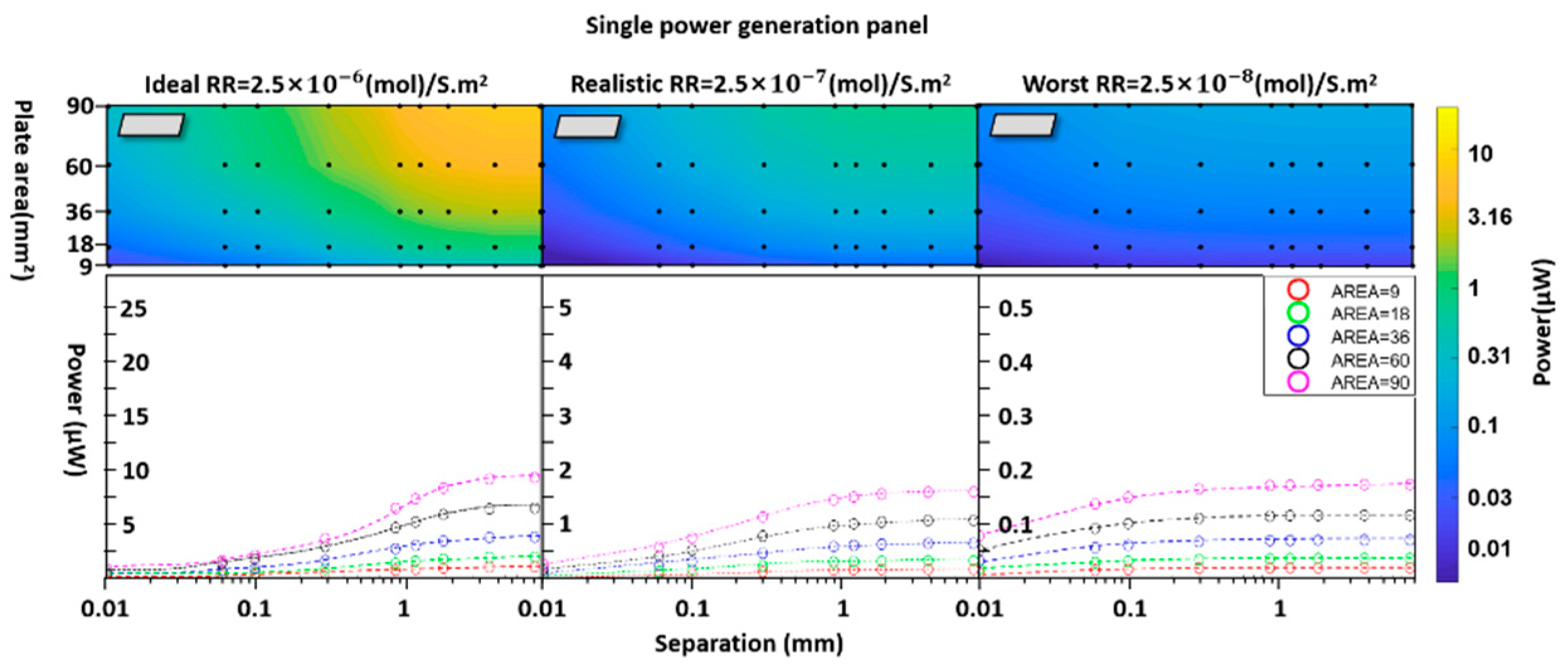

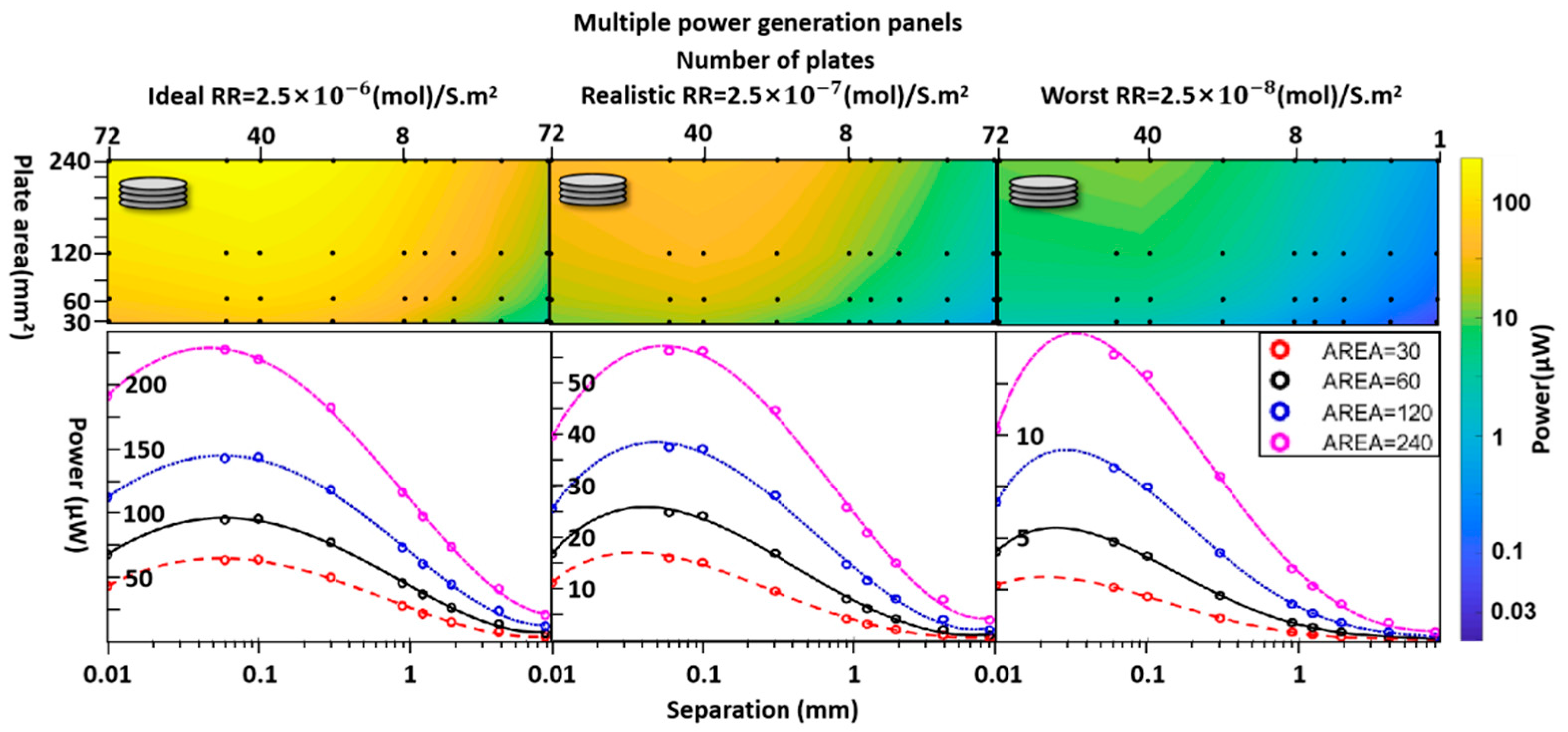

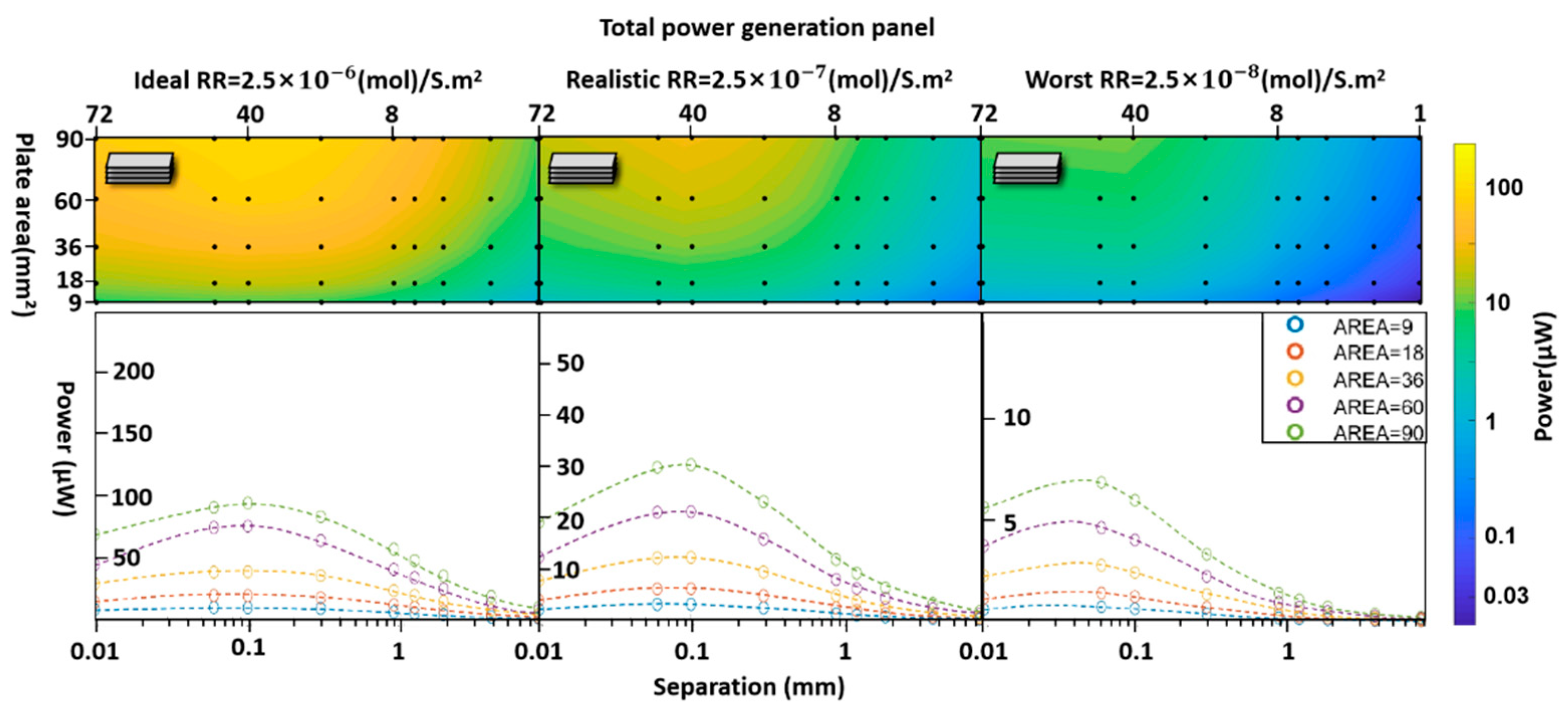

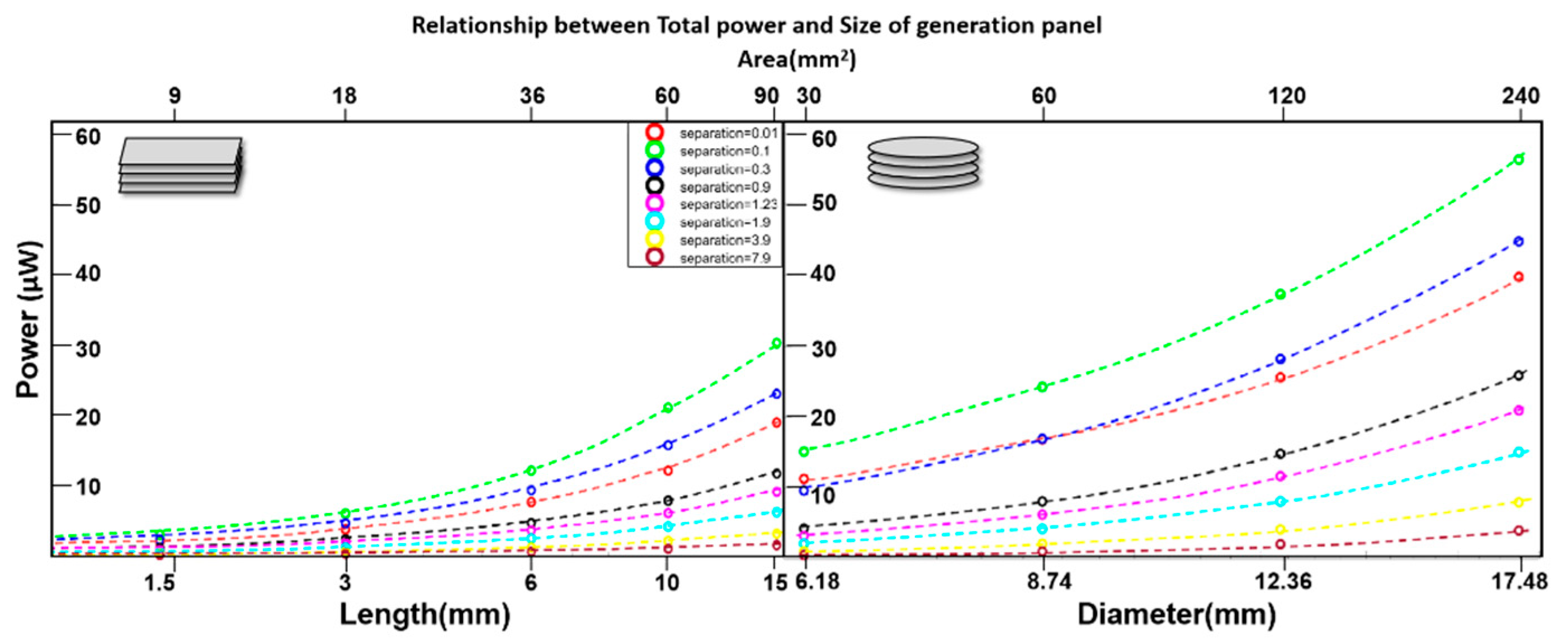

3.Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Goggins, E.; Mitani, S.; Tanaka, S. Clinical perspectives on vagus nerve stimulation: present and future. Clin. Sci. 2022, 136, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, D.J.; Gupta, I.; Matteucci, P.B.; Ouchouche, S.; de Jonge, W.J.; Coatney, R.W.; Salam, T.; Chew, D.J.; Irwin, E.; Yazicioglu, R.F.; et al. Splenic arterial neurovascular bundle stimulation in esophagectomy: A feasibility and safety prospective cohort study. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1088628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sato, M.; Ikeda, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Fujita, H.; Nagamori, E.; Kawabe, Y.; Kamihira, M. Induction of functional tissue-engineered skeletal muscle constructs by defined electrical stimulation. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicha, I.; Priefer, R.; Severino, P.; Souto, E.B.; Jain, S. Biosensor-Integrated Drug Delivery Systems as New Materials for Biomedical Applications. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadka, B.; Lee, B.; Kim, K.-T. Drug Delivery Systems for Personal Healthcare by Smart Wearable Patch System. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, Y.-H. Development of Implantable Medical Devices: From an Engineering Perspective. Int. Neurourol. J. 2013, 17, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.S.; Dorman, M.F. Cochlear implants: A remarkable past and a brilliant future. Hear. Res. 2008, 242, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaka, K.; Jacob, M.V. Implantable Devices: Issues and Challenges. Electronics 2012, 2, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblett, K.L.; Cadish, L.A. Sacral nerve stimulation for the treatment of refractory voiding and bowel dysfunction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. Bioelectronic medicine: Preclinical insights and clinical advances. Neuron 2022, 110, 3627–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, J.R.; Huston, J.M. Advances in Bioelectronic Medicine: Noninvasive Electrical, Ultrasound and Magnetic Nerve Stimulation. Bioelectron. Med. 2019, 2, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalili, J. The birth of the electric machines: a commentary on Faraday (1832) ‘Experimental researches in electricity’. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2015, 373, 20140208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquilina, O. A brief history of cardiac pacing. Images in paediatric cardiology 2006, 8, 17–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- LR House “Cochlear implant: the beginning.” Laryngoscope. 1987 Aug;97(8 Pt 1):996-7. [PubMed]

- Shealy, C.N.; Mortimer, J.T.; Reswick, J.B. Electrical inhibition of pain by stimulation of the dorsal columns: preliminary clinical report. . 1967, 46, 489–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, J.; Cagle, J.; Johnson, K.A.; Wong, J.K.; Hilliard, J.D.; Butson, C.R.; Okun, M.S.; de Hemptinne, C. Past, Present, and Future of Deep Brain Stimulation: Hardware, Software, Imaging, Physiology and Novel Approaches. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 825178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, F.A.; Chavan, S.S.; Miljko, S.; Grazio, S.; Sokolovic, S.; Schuurman, P.R.; Mehta, A.D.; Levine, Y.A.; Faltys, M.; Zitnik, R.; et al. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8284–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B.; Sinniger, V.; Pellissier, S. Therapeutic Potential of Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.; Lee, S.; Molnar, A.C.; Cash, S. Injectable wireless microdevices: challenges and opportunities. Bioelectron. Med. 2021, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ling, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Hartel, M.C.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Zhang, S.; Khademhosseini, A. A Sub-1-V, Microwatt Power-Consumption Iontronic Pressure Sensor Based on Organic Electrochemical Transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2020, 42, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerke, C.; Wolff, A.; Ince, H.; Ortak, J.; Öner, A. New strategies for energy supply of cardiac implantable devices. Herzschrittmachertherapie + Elektrophysiologie 2022, 33, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, E.; Valle, G. Neuromorphic hardware for somatosensory neuroprostheses. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Hannan, M.; Mutashar, S.; A Samad, S.; Hussain, A. Energy harvesting for the implantable biomedical devices: issues and challenges. Biomed. Eng. Online 2014, 13, 79–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, D.C.; Marschilok, A.C.; Takeuchi, K.J.; Takeuchi, E.S. Batteries used to power implantable biomedical devices. Electrochimica Acta 2012, 84, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallela, V.S.; Ilankumaran, V.; Rao, N. Trends in Cardiac Pacemaker Batteries. Indian pacing and electrophysiology journal 2004, 4, 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kerzenmacher, S.; Ducrée, J.; Zengerle, R.; von Stetten, F. Energy harvesting by implantable abiotically catalyzed glucose fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2008, 182, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Liu, J. Power sources and electrical recharging strategies for implantable medical devices. Front. Energy Power Eng. China 2008, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available from: The Complete Guide to Medical Device Batteries (ufinebattery.com).

- Ben Amar, A.; Kouki, A.B.; Cao, H. Power Approaches for Implantable Medical Devices. Sensors 2015, 15, 28889–28914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurs, A.; Karalis, A.; Moffatt, R.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Fisher, P.; Soljačić, M. Wireless Power Transfer via Strongly Coupled Magnetic Resonances. Science 2007, 317, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antfolk, C.; Kopta, V.; Farserotu, J.; Decotignie, J.-D.; Enz, C. The WiseSkin artificial skin for tactile prosthetics: A power budget investigation. in IEEE Conferences, 2014, pp. 1–4.

- Bock, D.C.; Marschilok, A.C.; Takeuchi, K.J.; Takeuchi, E.S. Batteries used to power implantable biomedical devices. Electrochimica Acta 2012, 84, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Akiyama, T. Pacemaker Longevity: The World's Longest-Lasting VVI Pacemaker. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2007, 12, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfenniger, A.; Jonsson, M.; Zurbuchen, A.; Koch, V.M.; Vogel, R. Energy Harvesting from the Cardiovascular System, or How to Get a Little Help from Yourself. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 41, 2248–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, D.C.; Marschilok, A.C.; Takeuchi, K.J.; Takeuchi, E.S. Batteries used to power implantable biomedical devices. Electrochimica Acta 2012, 84, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, G.; Yang, R.; Wang, A.C.; Wang, Z.L. Muscle-Driven In Vivo Nanogenerator. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2534–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayazian, S.; Hassibi, A. Delivering optical power to subcutaneous implanted devices. in 2011 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, IEEE, 2011, pp. 2874–2877.

- Magotra, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Kang, T.W.; Inamdar, A.I.; Aqueel, A.T.; Im, H.; Ghodake, G.; Shinde, S.; Waghmode, D.P.; Jeon, H.C. Compost Soil Microbial Fuel Cell to Generate Power using Urea as Fuel. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.M.; Reyes, C.; Lopez, G.P. Common Causes of Glucose Oxidase Instability in In Vivo Biosensing: A Brief Review. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Solino, C.; Bernalte, E.; Metcalfe, B.; Moschou, D.; Di Lorenzo, M. Power generation and autonomous glucose detection with an integrated array of abiotic fuel cells on a printed circuit board. J. Power Sources 2020, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, T.; Haneda, K.; Nagai, N.; Yatagawa, Y.; Onami, H.; Yoshino, S.; Abe, T.; Nishizawa, M. Enzymatic biofuel cells designed for direct power generation from biofluids in living organisms. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 5008–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, R.F.; Kusserow, B.K.; Messinger, S.; Matsuda, S. A tissue implantable fuel cell power supply. . 1970, 16, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, T.; Hu, Y.; Stoller, M.; Feldman, M.; Ruoff, R.S.; Ferrari, M.; Zhang, X. Mesoporous silica as a membrane for ultra-thin implantable direct glucose fuel cells. Lab a Chip 2011, 11, 2460–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiani, M.; Barzi, S.; Ahmadi, A.; Vizza, F.; Gharibi, H.; Azhari, A. Ex vivo energy harvesting by a by-pass depletion designed abiotic glucose fuel cell operated with real human blood serum. J. Power Sources 2022, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.; Ritzmann, R.E.; Lee, I.; Pollack, A.J.; Scherson, D. An Implantable Biofuel Cell for a Live Insect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczupak, A.; Halámek, J.; Halámková, L.; Bocharova, V.; Alfonta, L.; Katz, E. Living battery – biofuel cells operating in vivo in clams. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8891–8895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacVittie, K.; Halámek, J.; Halámková, L.; Southcott, M.; Jemison, W.D.; Lobel, R.; Katz, E. From “cyborg” lobsters to a pacemaker powered by implantable biofuel cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 6, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebda, A.; Cosnier, S.; Alcaraz, J.-P.; Holzinger, M.; Le Goff, A.; Gondran, C.; Boucher, F.; Giroud, F.; Gorgy, K.; Lamraoui, H.; et al. Single Glucose Biofuel Cells Implanted in Rats Power Electronic Devices. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, G.; Yang, R.; Wang, A.C.; Wang, Z.L. Muscle-Driven In Vivo Nanogenerator. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2534–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayazian, S.; Hassibi, A. Delivering optical power to subcutaneous implanted devices. in 2011 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, IEEE, 2011, pp. 2874–2877.

- Magotra, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Kang, T.W.; Inamdar, A.I.; Aqueel, A.T.; Im, H.; Ghodake, G.; Shinde, S.; Waghmode, D.P.; Jeon, H.C. Compost Soil Microbial Fuel Cell to Generate Power using Urea as Fuel. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Reyes, C.; Lopez, G.P. Common Causes of Glucose Oxidase Instability in In Vivo Biosensing: A Brief Review. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetten, F.; Kerzenmacher, S.; Lorenz, A.; Chokkalingam, V.; Miyakawa, N.; Zengerle, R.; Ducree, J. A One-Compartment, Direct Glucose Fuel Cell for Powering Long-Term Medical Implants. 19th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems. 2006, vol. 2006, pp. 934–937. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, T.; Haneda, K.; Nagai, N.; Yatagawa, Y.; Onami, H.; Yoshino, S.; Abe, T.; Nishizawa, M. Enzymatic biofuel cells designed for direct power generation from biofluids in living organisms. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 5008–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, R.F.; Kusserow, B.K.; Messinger, S.; Matsuda, S. A tissue implantable fuel cell power supply. ASAIO Journal 1970, 16, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, T.; Hu, Y.; Stoller, M.; Feldman, M.; Ruoff, R.S.; Ferrari, M.; Zhang, X. Mesoporous silica as a membrane for ultra-thin implantable direct glucose fuel cells. Lab a Chip 2011, 11, 2460–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhiani, M.; Barzi, S.; Gholamian, M.; Ahmadi, A. Synthesis and evaluation of Pt/rGO as the anode electrode in abiotic glucose fuel cell: Near to the human body physiological condition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 13496–13507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torigoe, K.; Takahashi, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Iwabata, K.; Ichihashi, T.; Sakaguchi, K.; Sugawara, F.; Abe, M. High-Power Abiotic Direct Glucose Fuel Cell Using a Gold–Platinum Bimetallic Anode Catalyst. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 18323–18333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holade, Y.; Tingry, S.; Servat, K.; Napporn, T.W.; Cornu, D.; Kokoh, K.B. Nanostructured Inorganic Materials at Work in Electrochemical Sensing and Biofuel Cells. Catalysts 2017, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloke, A.; Köhler, C.; Zengerle, R.; Kerzenmacher, S. Porous Platinum Electrodes Fabricated by Cyclic Electrodeposition of PtCu Alloy: Application to Implantable Glucose Fuel Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 19689–19698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, L.; Hong, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Que, Q.; Ji, J. Three-dimensional Porous Palladium Foam-like Nanostructures as Electrocatalysts for Glucose Biofuel Cells. Energy Technol. 2016, 4, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, M.; Deng, W.; Tan, Y.; Ma, M.; Su, X.; Xie, Q.; Yao, S. Facile fabrication of network film electrodes with ultrathin Au nanowires for nonenzymatic glucose sensing and glucose/O2 fuel cell. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 52, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.M.; Ackland, H.M.; Lowery, A.J.; Rosenfeld, J.V. Restoration of vision in blind individuals using bionic devices: A review with a focus on cortical visual prostheses. Brain Res. 2015, 1595, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WeidlichE, RichterG, vonSturmF. Animal experimental with biogalvanic and biofuel lcells[J].Biomaterials, MedicalDevices,andArtificialOrgans,1979,4:3-4.

- X. Wei, Y. X. Wei, Y. Min. et al. “Oxygen Solubility, Diffusion Coefficient, and Solution Viscosity” Rotating Electrode Methods and Oxygen Reduction Electrocatalysts,2014.

- Bashkatov, A.N.; Genina, E.A.; Sinichkin, Y.P.; Kochubey, V.I.; Lakodina, N.A.; Tuchin, V.V. Glucose and Mannitol Diffusion in Human Dura Mater. Biophys. J. 2003, 85, 3310–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallela, V.S.; Ilankumaran, V.; Rao, N. Trends in Cardiac Pacemaker Batteries. 2004, 4, 201–212.

- Katz, D.; Akiyama, T. Pacemaker Longevity: The World's Longest-Lasting VVI Pacemaker. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2007, 12, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutbee, A.T.; Bahabry, R.R.; Alamoudi, K.O.; Ghoneim, M.T.; Cordero, M.D.; Almuslem, A.S.; Gumus, A.; Diallo, E.M.; Nassar, J.M.; Hussain, A.M.; et al. Flexible and biocompatible high-performance solid-state micro-battery for implantable orthodontic system. npj Flex. Electron. 2017, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.L.Benabid, et al. “Combined (Thalamotomy and Stimulation) Stereotactic Surgery of the VIM Thalamic Nucleus for Bilateral Parkinson Disease”. 1159. [CrossRef]

- Available from: https://resonetics.com/sensor-technology-medical-power/medical-batteries/.

- Adeva-Andany, M.M.; González-Lucán, M.; Donapetry-García, C.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; Ameneiros-Rodríguez, E. Glycogen metabolism in humans. BBA Clin. 2016, 5, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosnier, S.; Le Goff, A.; Holzinger, M. Towards glucose biofuel cells implanted in human body for powering artificial organs: Review. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 38, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Tannia, D.C.; Kwon, Y. Glucose biofuel cells using bi-enzyme catalysts including glucose oxidase, horseradish peroxidase and terephthalaldehyde crosslinker. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003482.htm.

- Collins, J.-A.; Rudenski, A.; Gibson, J.; Howard, L.; O’dRiscoll, R. Relating oxygen partial pressure, saturation and content: the haemoglobin–oxygen dissociation curve. Breathe 2015, 11, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available from: https://www.cosinuss.com/en/measured-data/vital-signs/oxygen-saturation/.

- Available from: https://www.ciamedical.com/insights/iv-catheter-sizes/.

- Limperg, T.B.; Novoa, V.Y.; Curlin, H.L.; Veersema, S. Laparoscopic Trocars: Marketed Versus True Dimensions–A Descriptive Study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2024, 31, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available from: https://www.dipolerfid.com/product/rfid-tags-for-animal-identification.

- Beurskens, N.E.; Tjong, F.V.; E Knops, R. End-of-life Management of Leadless Cardiac Pacemaker Therapy. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. Rev. 2017, 6, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available from: https://newatlas.com/computers/mibmi-text-accuracy/.

- He, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, N.; Mu, L.; Pan, J.; Lan, X.; Li, H.; Deng, F. Anti-Biofouling Polymers with Special Surface Wettability for Biomedical Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 807357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Yun, J.-H.; Bin Park, Y.; Hyeon, J.S.; Jang, Y.; Choi, Y.-B.; Kim, H.-H.; Kang, T.M.; Ovalle, R.; Baughman, R.H.; et al. Two-Ply Carbon Nanotube Fiber-Typed Enzymatic Biofuel Cell Implanted in Mice. IEEE Trans. NanoBioscience 2020, 19, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmaële, D.; La Malfa, F.; Rizzi, F.; Qualtieri, A.; Di Lorenzo, M.; De Vittorio, M. A novel flexible conductive sponge-like electrode capable of generating electrical energy from the direct oxidation of aqueous glucose. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2019, 1407, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyazi, A.; Metcalfe, B.; Leese, H.S.; Di Lorenzo, M. One-step polyaniline-platinum nanoparticles grafting on porous gold anode electrodes for high-performance glucose fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2025, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogev, D.; Goldberg, T.; Arami, A.; Tejman-Yarden, S.; Winkler, T.E.; Maoz, B.M. Current state of the art and future directions for implantable sensors in medical technology: Clinical needs and engineering challenges. APL Bioeng. 2023, 7, 031506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Sencadas, V.; You, S.S.; Jia, N.Z.; Srinivasan, S.S.; Huang, H.; Ahmed, A.E.; Liang, J.Y.; Traverso, G. Powering Implantable and Ingestible Electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

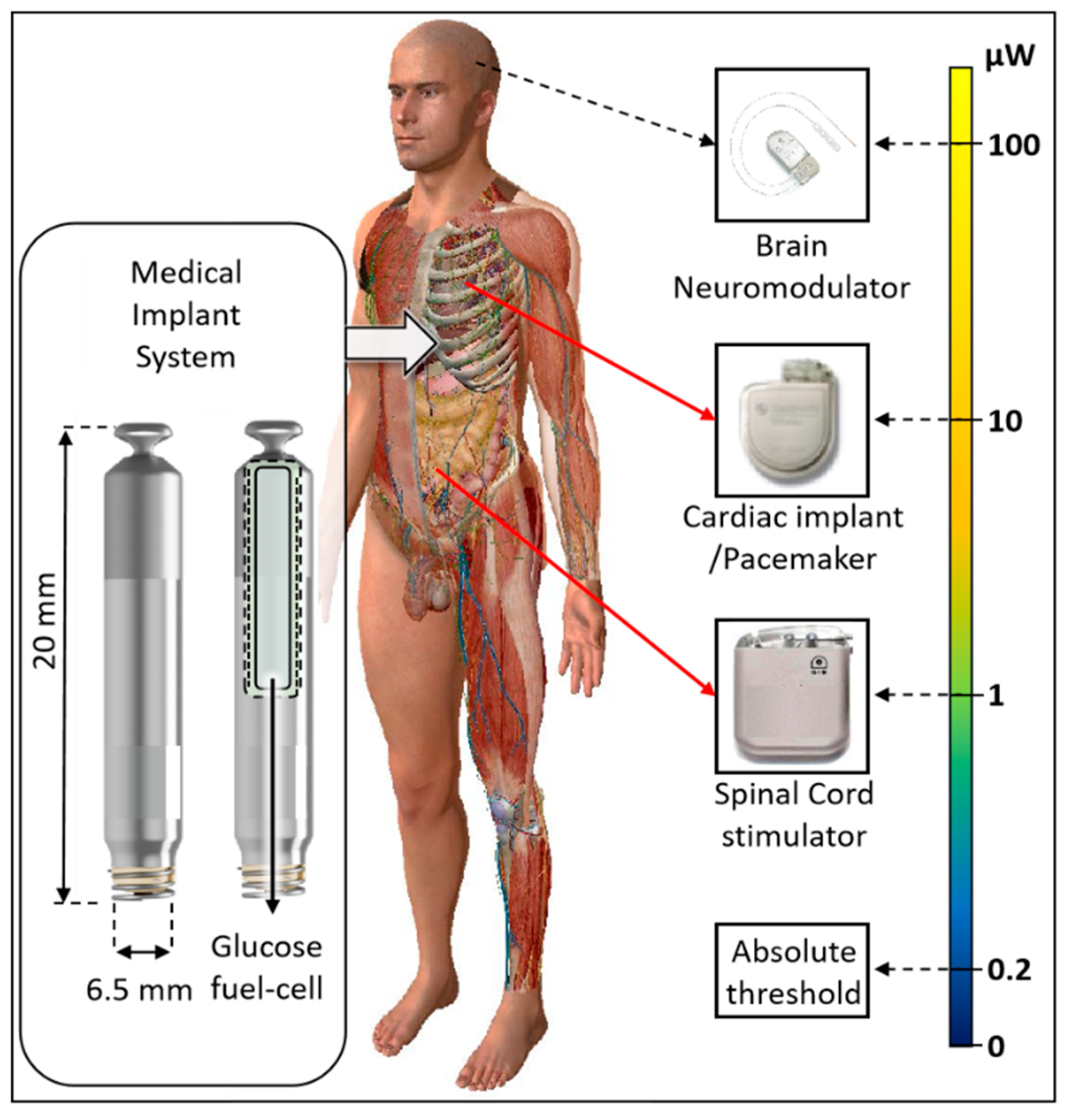

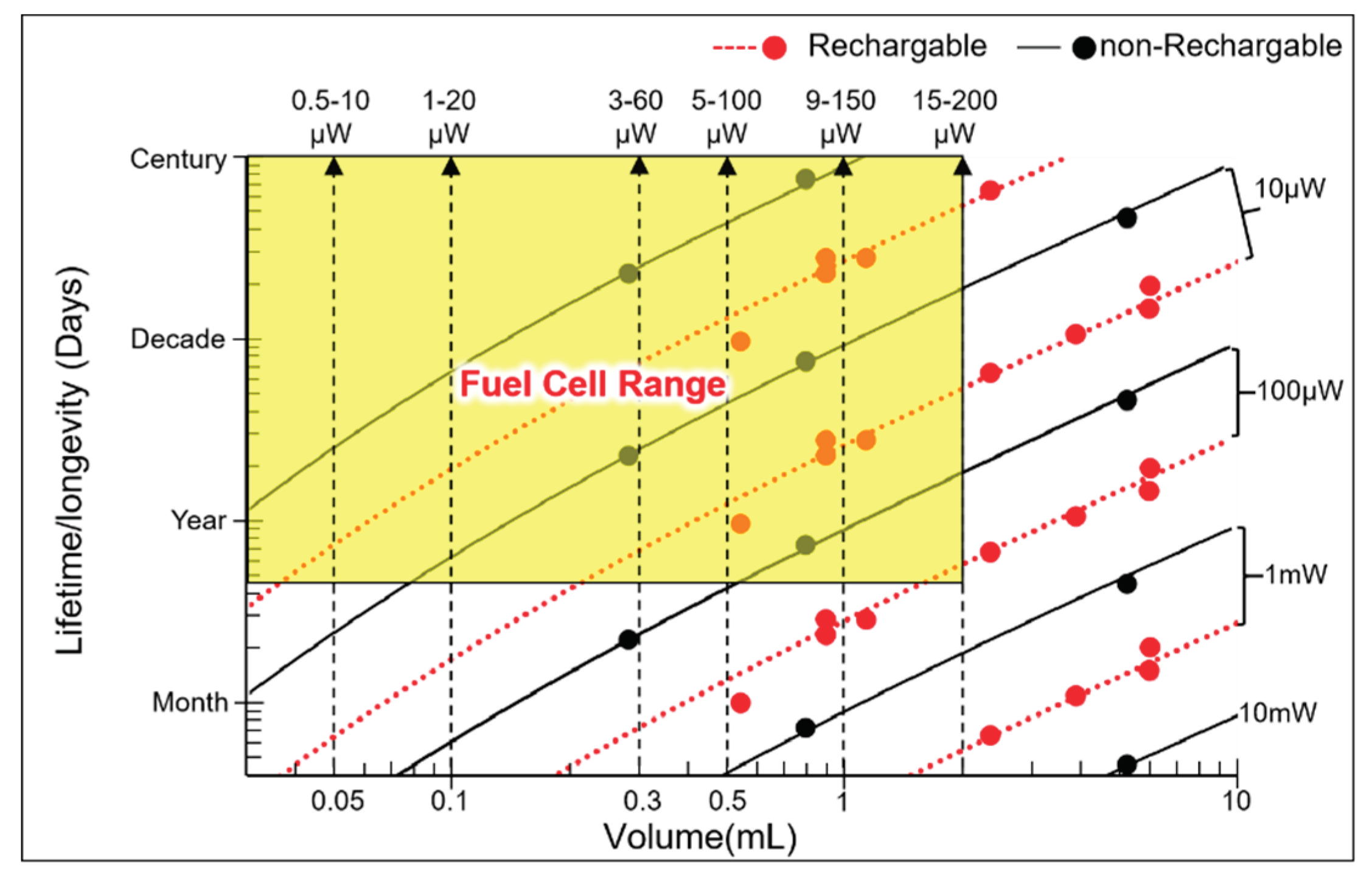

| Implant | Power range | Lifetime when powered by a 10 mL battery | Lifetime when powered by a 1 mL battery | Lifetime when powered by a 50 µL battery | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioelectronic medicine | <10 μW |

>118 years | >11 years | >7 months | [19,20] |

| Pacemaker | ~10-100 μW | ~11-118years | ~1-11 years | ~21days- 7months |

[21] |

| Neurostimulator | ~100-400 μW |

~3-11 years | ~108 days -1 year | ~5-21days | [22] |

| Sensory prosthetics | >10 mW | Wireless power | Wireless power | Wireless power | [31] |

| Module parameters | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion coefficient | Glucose:0.9 x 10-9 Oxygen: 3 x 10-9 |

m² s-1 |

| Boundary glucose concentration | 5 | mMol L-1 |

| Boundary oxygen concentration | 4.5 | mMol L-1 |

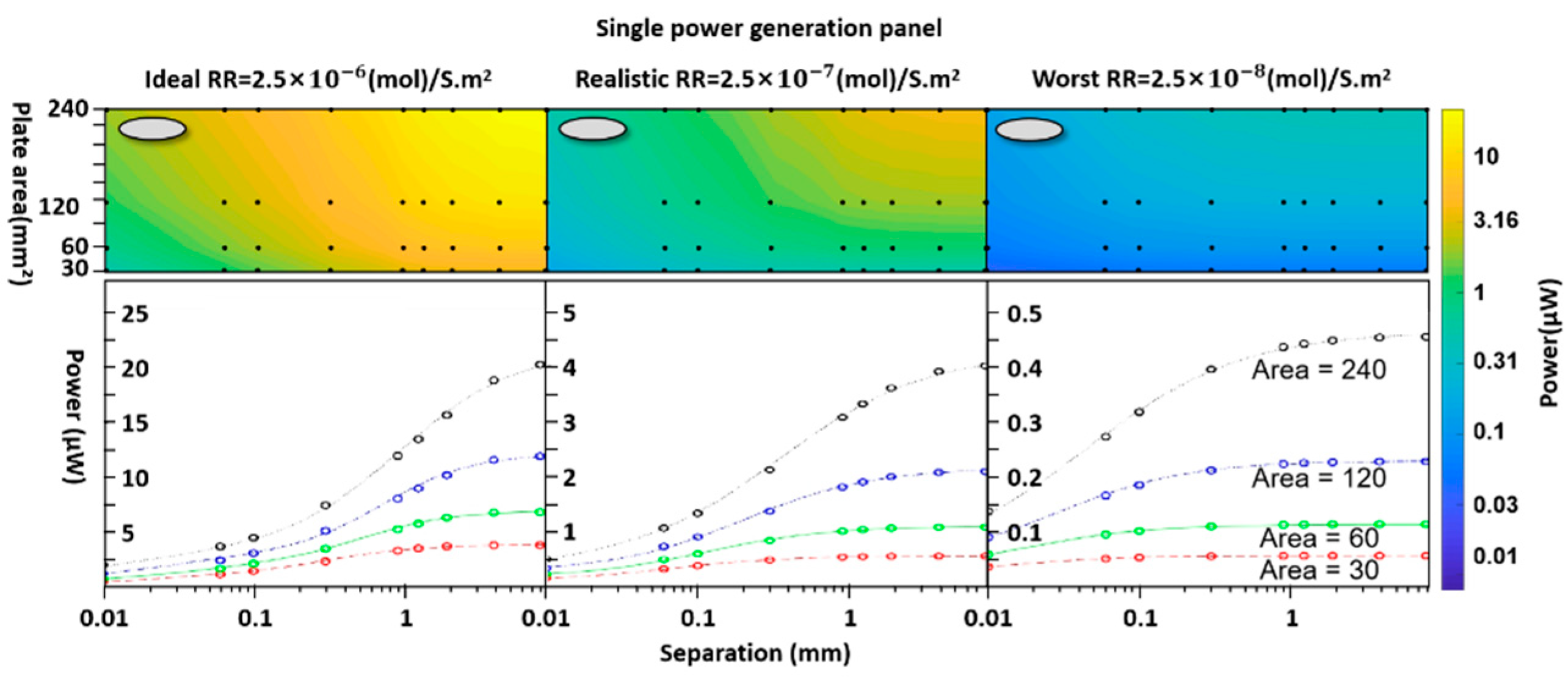

| Basic surface reaction rate | 2.5 x 10-6 2.5 x 10-7 2.5 x 10-8 ; |

(mol) s-1m-2 |

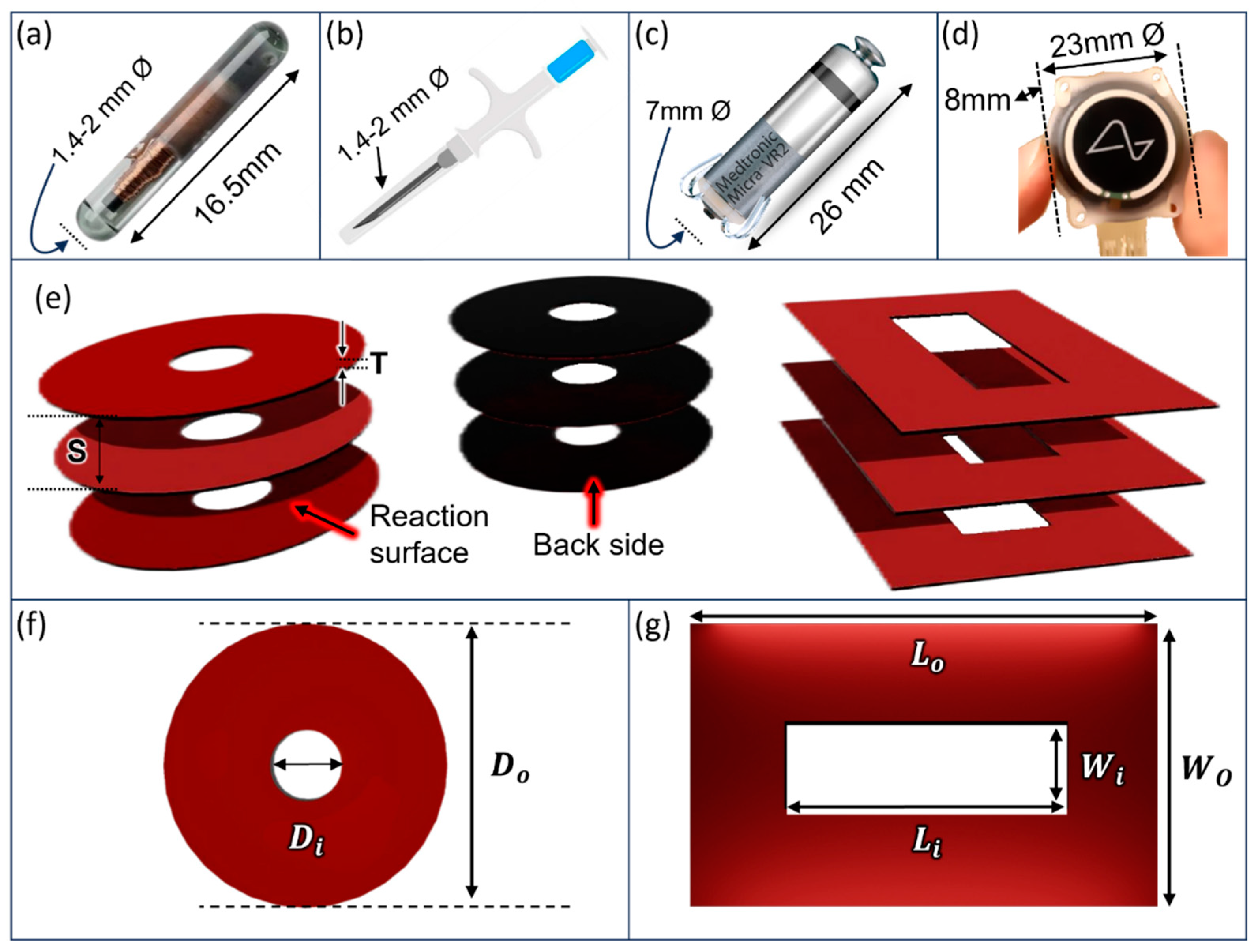

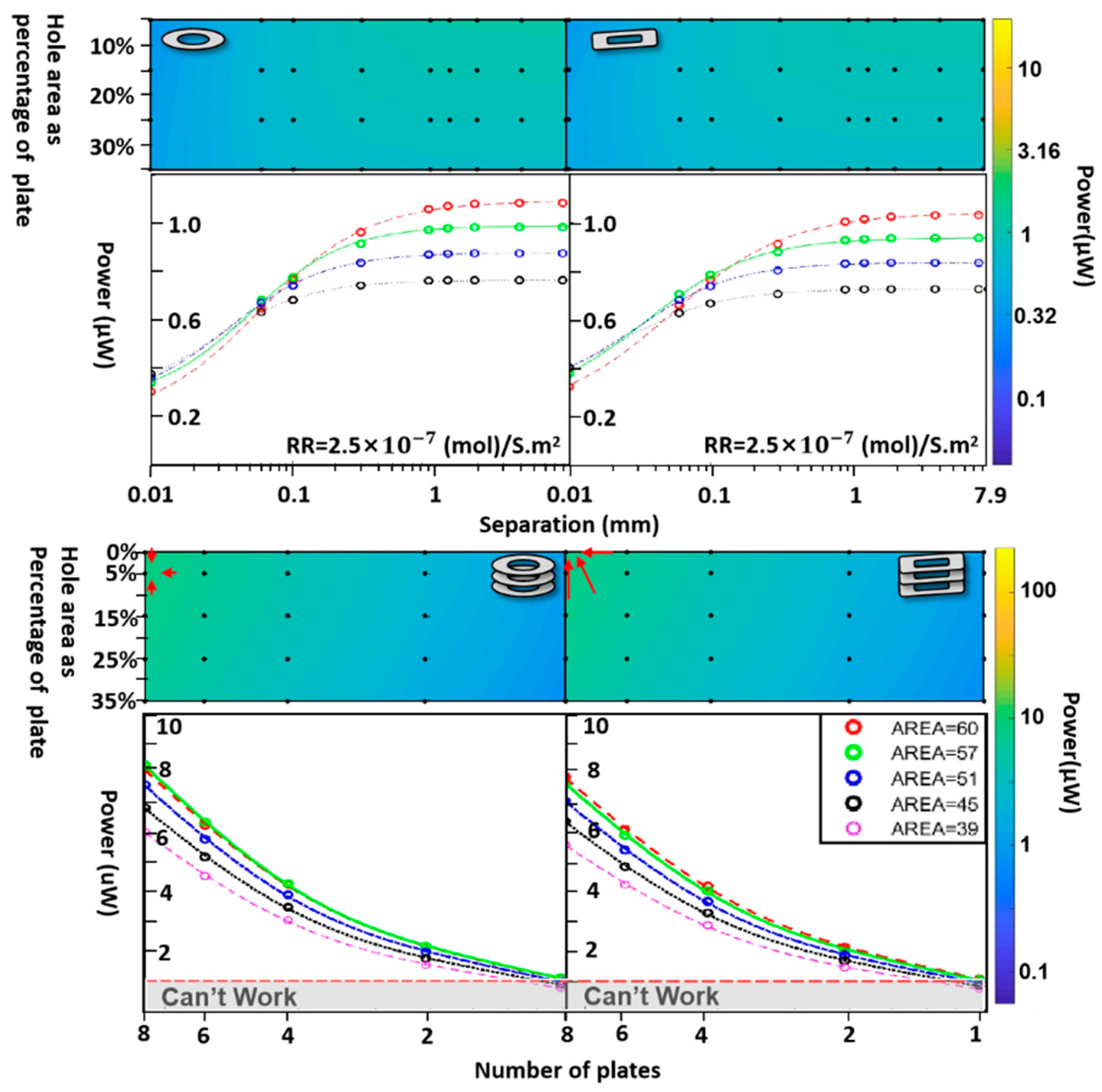

| Parameter | Values | Unit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness | T | 0.1 | mm | |

| Separation | S | 0.01,0.06,0.1 ,0.3, 0.9,1.23,1.9,3.9,7.9 | mm | |

| Cylinder | ||||

| Outer diameter | 6.18, 8.74,12.36,17.48 | mm | ||

| Area | A | 30, 60,120,240 | mm² | |

| Block without hole | ||||

| Width | W | 6 | mm | |

| Length | L | 1.5,3,6,10,15 | mm | |

| Area | A | 9,18,36,60,90 | mm2 | |

| Cylinder with hole | ||||

| Outer diameter | 8.74 | mm | ||

| Inner diameter (hole) | 1.994, 3.384, 4.37, 5.17 | mm | ||

| Area | A | 57, 51,45, 39, | mm² | |

| Blockwith hole | ||||

| Outer length | 10 | mm | ||

| Inner length (hole) | 3,6,7.5,7 | mm | ||

| Outer width | 6 | mm | ||

| Inner width (hole) | 1,1.5,2,3 | mm | ||

| Area | A | 57, 51,45, 39 | mm² | |

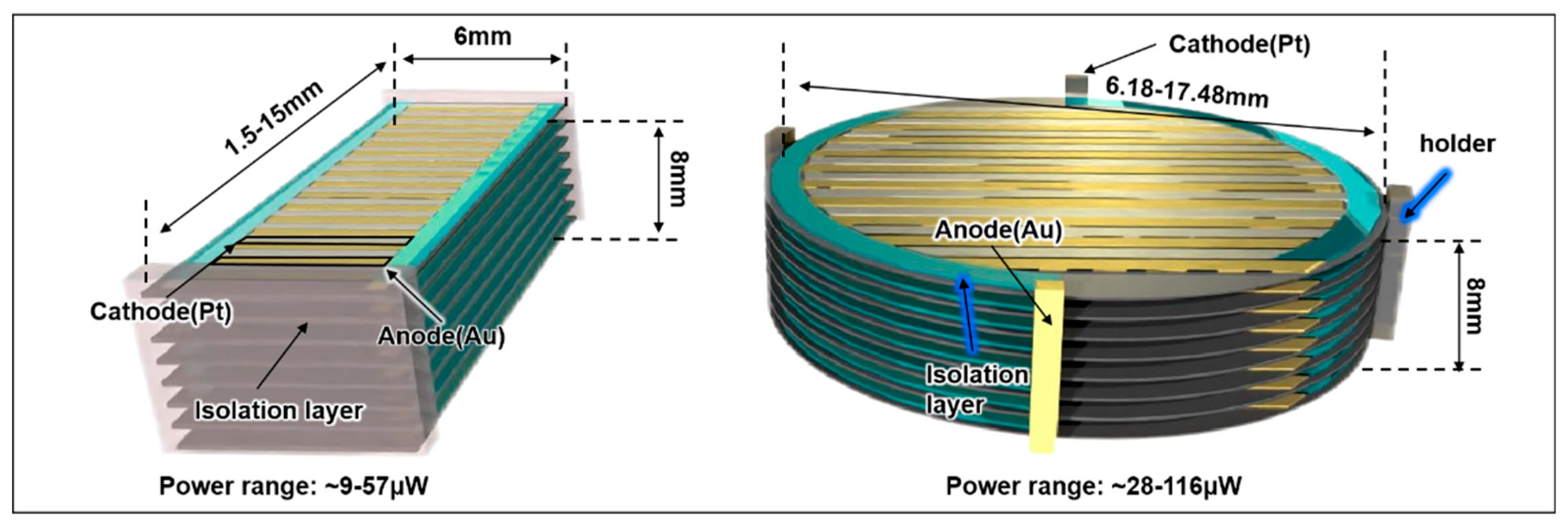

| Module parameters | Value | Unit |

| Separation | 0.9 | mm |

| Thickness of generator unit | 0.1 | mm |

| Number of generation units | 8 | |

| Basic surface reaction rate | 2.5 | (mol) s-1m-2 |

| Pill shaped device | ||

| Length | 1.5-15 | mm |

| Width | 6 | mm |

| Area | 9-90 | mm² |

| Total Power (range) | ~9-57 | μW |

| Disc shaped device | ||

| Diameter | 6.18-17.48 | mm |

| Area | 30-240 | mm2 |

| Total Power range | ~28-116 | μW |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).