Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Preparation

2.1.1. Preparation of DAPT-HAAM

2.1.2. Preparation of VEGF-GG-HA

2.1.3. Preparation of VEGF-GG-HA&DAPT-HAAM

2.2. In Vitro Studies

2.2.1. Assessment of Cell Activity by the CCK-8 Assay

2.2.2. Determination of Cytokine Profile by ELISA and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

- IL-10: Forward Primer: TCAAGGCGCATGTGAACTCC (Length: 20, Tm: 62.8°C), Reverse Primer: GATGTCAAACTCACTCATGGCT (Length: 22, Tm: 60.3°C).

- TNF-α: Forward Primer: CCTCTCTCTCTAATCAGCCCTCTG (Length: 22, Tm: 60.8°C), Reverse Primer: GAGGACCTGGGGAGTAGATGAG (Length: 21, Tm: 60.2°C).

2.2.3. Western Blotting Analysis

2.2.4. Immunohistochemical Staining

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

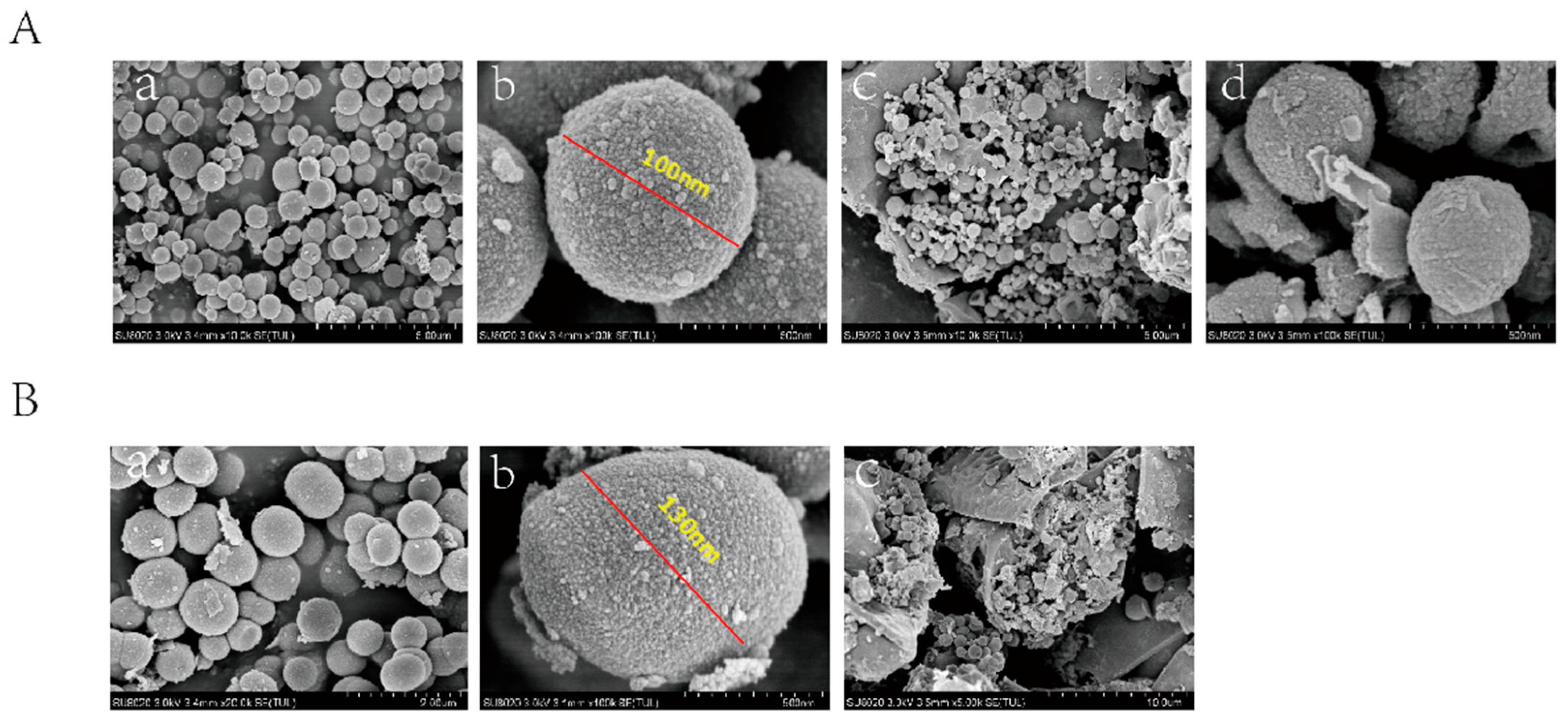

3.1. Characterization of VEGF-GG-HA and DAPT-HAAM

3.2. In Vitro Cell Experiment

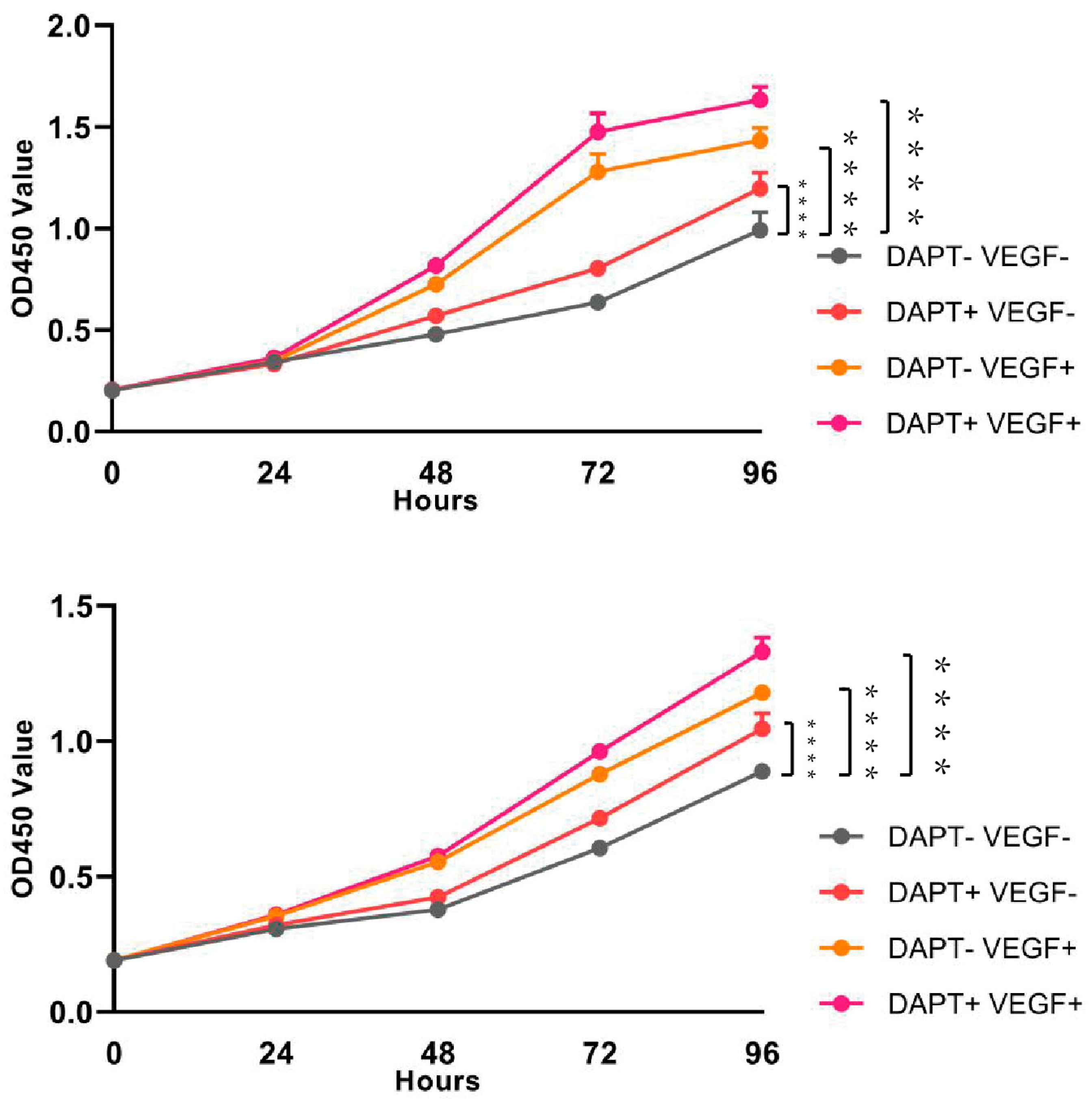

3.2.1. Assessment of Cell Activity by the CCK-8 Assay

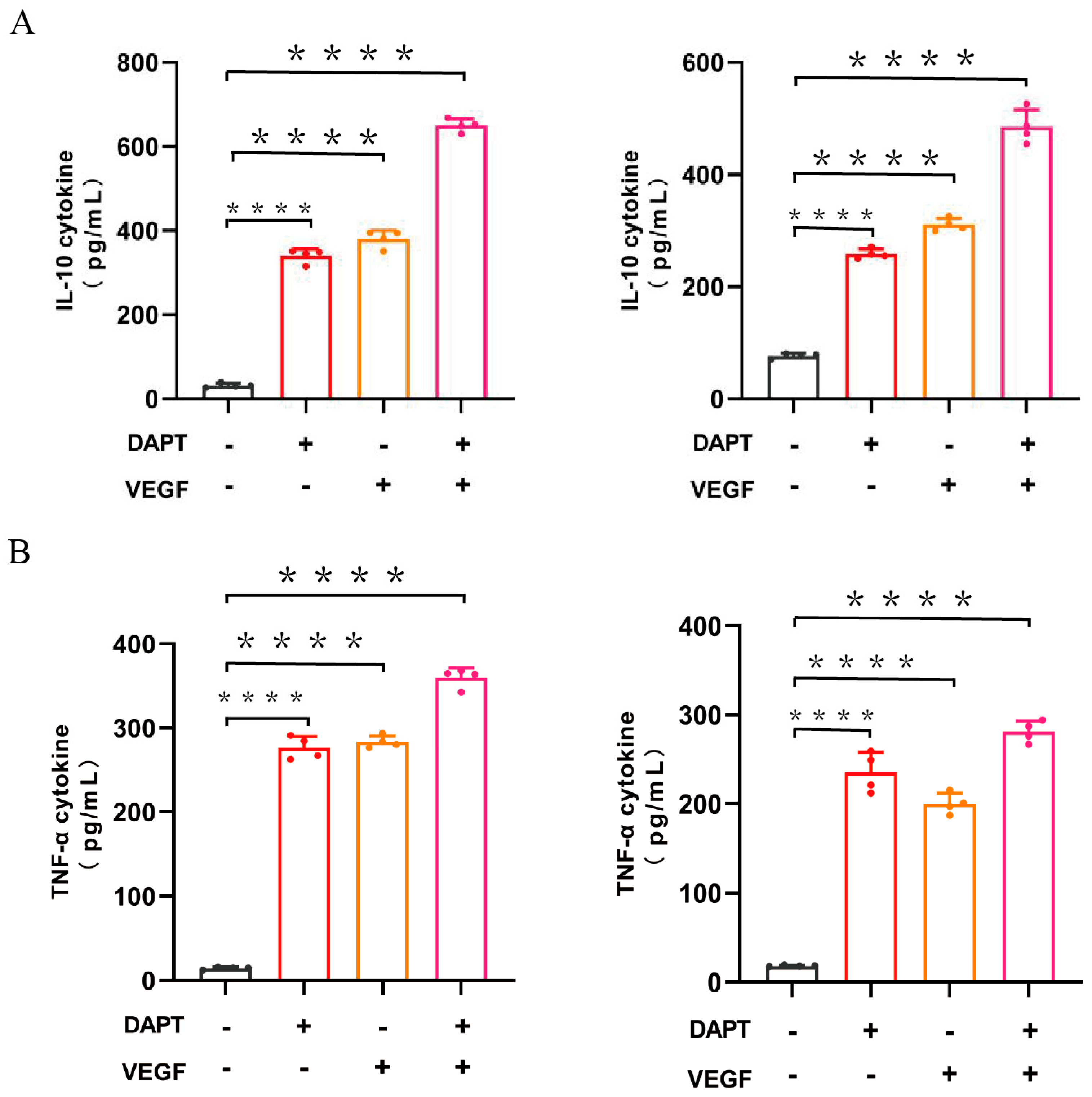

3.2.2. Determination of Cytokine Profile by ELISA

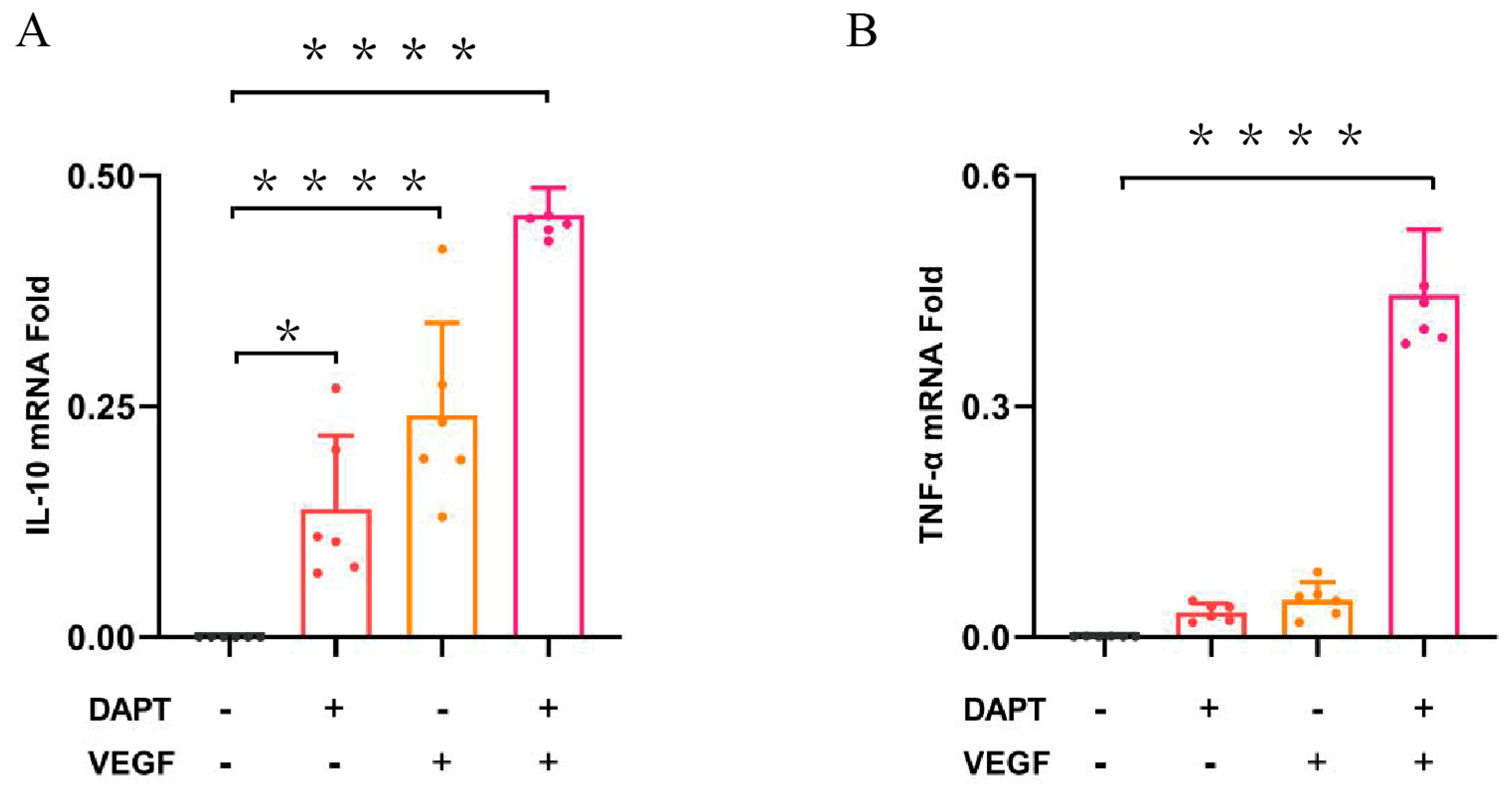

3.2.3. Determination of Cytokine Profile by QPCR

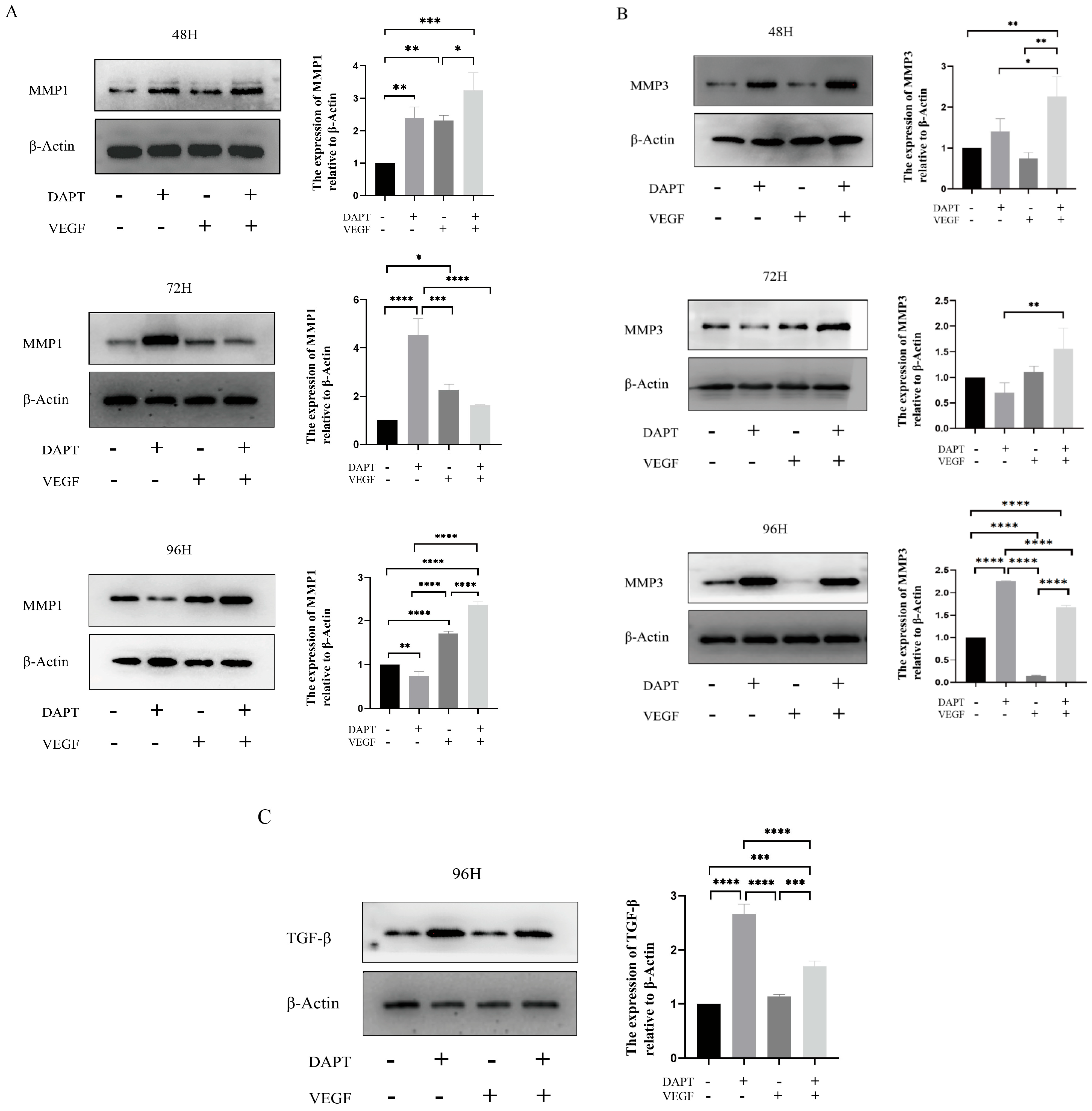

3.2.4. Western Blotting Analysis

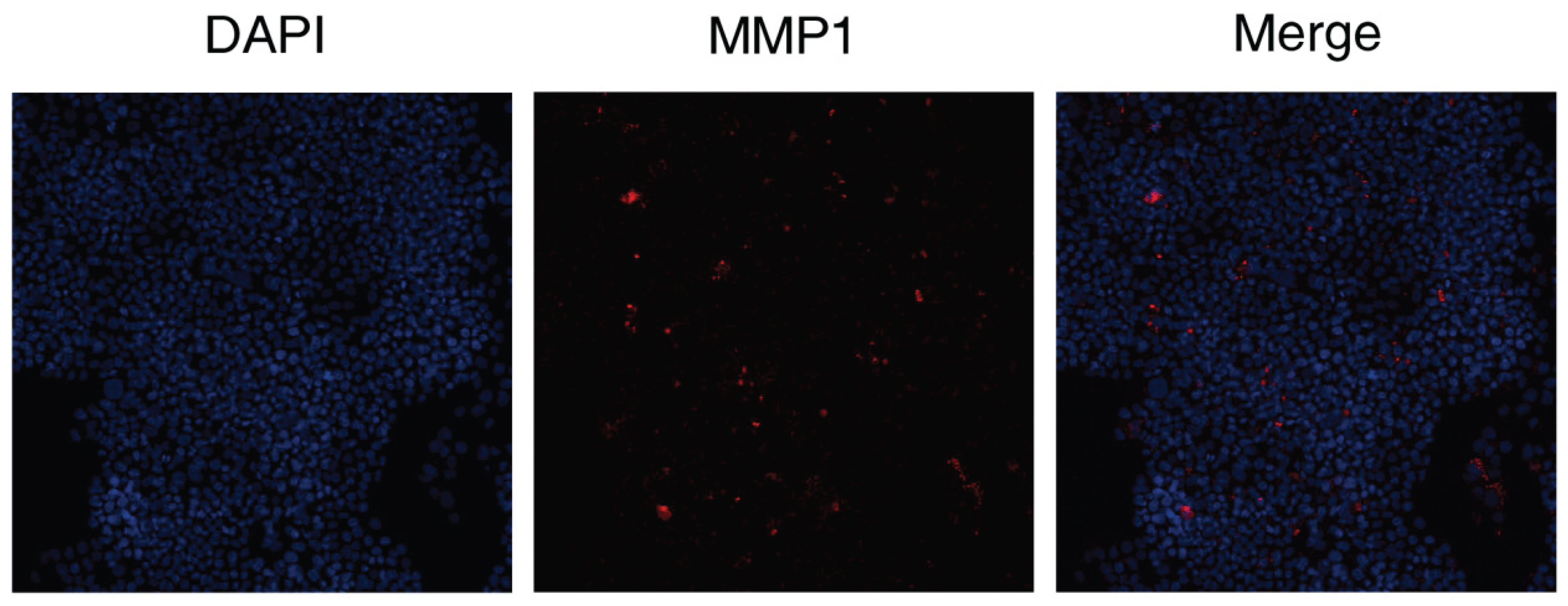

3.2.5. Immunohistochemical Staining

4. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joshi CJ: Hassan A: Carabano M, Galiano RD. Up-to-date role of the dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane (AMNIOFIX) for wound healing. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;20(10):1125-1131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Y, Lyu L, Xue S. Evaluation of human acellular amniotic membrane for promoting anterior auricle reconstruction. Exp Dermatol. 2022;31(5):823-824. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue SL, Liu K, Parolini O, Wang Y, Deng L, Huang YC. Human acellular amniotic membrane implantation for lower third nasal reconstruction: a promising therapy to promote wound healing. Burns Trauma. 2018;6:34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira HR, Marques AP. Vascularization in skin wound healing: where do we stand and where do we go? Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2022;73:253-262. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron JM, Glatz M, Proksch E. Optimal Support of Wound Healing: New Insights. Dermatology. 2020;236(6):593-600. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva LP, Pirraco RP, Santos TC, Novoa-Carballal R, Cerqueira MT, Reis RL, et al. Neovascularization Induced by the Hyaluronic Acid-Based Spongy-Like Hydrogels Degradation Products. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(49):33464-33474. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distler A, Lang V, Del VT, Huang J, Zhang Y, Beyer C, et al. Combined inhibition of morphogen pathways demonstrates additive antifibrotic effects and improved tolerability. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1264-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloc M, Ghobrial RM, Wosik J, Lewicka A, Lewicki S, Kubiak JZ. Macrophage functions in wound healing. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;13(1):99-109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bygd HC, Forsmark KD, Bratlie KM. Altering in vivo macrophage responses with modified polymer properties. Biomaterials. 2015;56:187-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar M, Coburn J, Kaplan DL, Mandal BB. Immuno-Informed 3D Silk Biomaterials for Tailoring Biological Responses. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(43):29310-29322. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar M, Nandi SK, Kaplan DL, Mandal BB. Localized Immunomodulatory Silk Macrocapsules for Islet-like Spheroid Formation and Sustained Insulin Production. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2017;3(10):2443-2456. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifiaghdam M, Shaabani E, Faridi-Majidi R, De Smedt SC, Braeckmans K, Fraire JC. Macrophages as a therapeutic target to promote diabetic wound healing. Mol Ther. 2022;30(9):2891-2908. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas T, Waisman A, Ranjan R, Roes J, Krieg T, Muller W, et al. Differential roles of macrophages in diverse phases of skin repair. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3964-77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitcheson SM, Frentiu FD, Hurn SE, Edwards K, Murray RZ. Skin Wound Healing: Normal Macrophage Function and Macrophage Dysfunction in Diabetic Wounds. Molecules. 2021;26(16). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin GR, Hwang SB, Park HJ, Lee BH, Boisvert WA. Microinjury-Induced Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Surge Stimulates Hair Regeneration in Mice. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2023;36(1):27-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naserian S, Abdelgawad ME, Afshar BM, Ha G, Arouche N, Cohen JL, et al. The TNF/TNFR2 signaling pathway is a key regulatory factor in endothelial progenitor cell immunosuppressive effect. Cell Commun Signal. 2020;18(1):94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong MM, Chen Y, Margariti A, Winkler B, Campagnolo P, Potter C, et al. Macrophages control vascular stem/progenitor cell plasticity through tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(3):635-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang Y, Li S. Detection of characteristic sub pathway network for angiogenesis based on the comprehensive pathway network. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams F, Moravvej H, Hosseinzadeh S, Mostafavi E, Bayat H, Kazemi B, et al. Overexpression of VEGF in dermal fibroblast cells accelerates the angiogenesis and wound healing function: in vitro and in vivo studies. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):18529. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza LV, De Meneck F, Oliveira V, Higa EM, Akamine EH, Franco M. Detrimental Impact of Low Birth Weight on Circulating Number and Functional Capacity of Endothelial Progenitor Cells in Healthy Children: Role of Angiogenic Factors. J Pediatr. 2019;206:72-77.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, CD. Anatomy of a discovery: m1 and m2 macrophages. Front Immunol. 2015;6:212. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani A, Biswas SK, Galdiero MR, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J Pathol. 2013;229(2):176-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehnert S, Rinderknecht H, Liu C, Voss M, Konrad FM, Eisler W, et al. Increased Levels of BAMBI Inhibit Canonical TGF-beta Signaling in Chronic Wound Tissues. Cells. 2023;12(16). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Canada C, Bernabe-Garcia A, Liarte S, Rodriguez-Valiente M, Nicolas FJ. Chronic Wound Healing by Amniotic Membrane: TGF-beta and EGF Signaling Modulation in Re-epithelialization. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:689328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penn JW, Grobbelaar AO, Rolfe KJ. The role of the TGF-beta family in wound healing, burns and scarring: a review. Int J Burns Trauma. 2012;2(1):18-28. [PubMed]

- Huth S, Huth L, Marquardt Y, Cheremkhina M, Heise R, Baron JM. MMP-3 plays a major role in calcium pantothenate-promoted wound healing after fractional ablative laser treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;37(2):887-894. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnaswamy VR, Mintz D, Sagi I. Matrix metalloproteinases: The sculptors of chronic cutaneous wounds. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017;1864(11 Pt B):2220-2227. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu X, Bellayr I, Pan H, Choi Y, Li Y. Regeneration of soft tissues is promoted by MMP1 treatment after digit amputation in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).