1. The Clinical Burden of Fractures, Chronic Wounds, and Dysregulated Healing

The burden of impaired bone and wound healing is a major clinical and socioeconomic challenge, particularly in elderly and multimorbid populations. Fractures and immobility-related pressure ulcers create a massive treatment demand worldwide [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Despite increasing knowledge about the cellular and molecular mechanisms of the underlying healing phases, 2–10% of all fractures result in delayed healing or the formation of non-unions [

5,

6]. Proximal femoral fractures, complicated by chronic ulceration, are common scenarios linking bone healing and soft tissue repair [

7,

8,

9]. Chronic wounds affect up to 2% of the elderly population and are associated with high mortality, loss of independence, and spiraling healthcare costs [

10,

11,

12]. Failed healing results in significant pain and functional impairment of the affected extremity, reducing the quality of life for the affected patient. Furthermore, the lengthy rehabilitation process, as well as the loss of labor and productivity, represent a significant economic burden on our healthcare system [

13,

14]. A detailed understanding of the molecular regulation of wound healing is thus paramount.

At the heart of wound healing lies the extracellular matrix (ECM), a dynamic environment regulating cell migration, angiogenesis, fibroblast activation, and scar formation [

15,

16,

17]. Growth factor–ECM interactions, particularly via transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), determine the balance between regenerative versus fibrotic outcomes [

18,

19,

20,

21]. While collagen, elastin, and fibronectin are heavily studied components of the ECM, more recently extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) has emerged as a pivotal but underappreciated regulator of tissue repair and regeneration.

This review will delineate ECM1’s role in wound healing through modulation of the TGF-β signaling pathway and highlight the connection of immune, fibrotic, and angiogenic control in wound and fracture healing.

2. TGF-β Signaling in Wound and Fracture Healing: Friend and Foe

Wound and fracture healing are coordinated in sequential but overlapping phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation (granulation tissue, angiogenesis, fibroblast activity), and remodeling/maturation [

22,

23,

24]. TGF-β is central in orchestrating this process:

During the

inflammation phase large amounts of active TGF-β are released by coagulating platelets in order to recruit immune cells and modulate macrophages phenotypes [

25,

26]. In the following course of healing TGF-β gets activated from the extracellular reservoir of latent TGF-β either by proteolytic cleavage from latent TGF-β binding protein (LTBP) or by mechanical forces or acidification of pH. In the

proliferation phase TGF-β stimulates fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts [

27], promotes angiogenesis [

28,

29], and regulates ECM deposition [

18]. In the

remodeling phase, balanced TGF-β-activity ensures proper ECM turnover via orchestrating collagen deposition and metalloproteinase activity [

30,

31].

While TGF-β signaling is associated with impaired bone and wound healing [

32,

33,

34,

35] its prolonged or enhanced signaling is associated with fibrotic conditions, keloid, hypertrophic scar formation and chronic wounds [

19,

31,

36]. Thus, regulation of TGF-β is essential to steer repair toward regeneration rather than fibrosis.

3. Extracellular Matrix Protein 1 (ECM1)

3.1. EMC1: a Multifunctional ECM Protein in Skin and Wound Repair

Extracellular matrix protein-1 (ECM1) is a glycoprotein secreted into the ECM, expressed by keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells [

37]. It regulates skin barrier integrity, angiogenesis, keratinocyte differentiation, and matrix organization [

38]. Its clinical relevance is underscored by Lipoid Proteinosis, a genetic disease caused by ECM1 mutations, characterized by scarring and impaired skin integrity [

39].

In wound healing, ECM1 has been shown to (i) Modulate angiogenesis by interacting with VEGF and perivascular ECM components [

17,

40]; (ii) Bind to perlecan and influence basement membrane assembly and keratinocyte migration [

28,

41]; (iii) regulate matrix turnover by inhibiting MMP-9 activity, thereby balancing ECM degradation and deposition [

17,

42].

ECM1 functions as an integral mediator balancing angiogenic activity and fibrotic suppression, both of which are tightly regulated by TGF-β–dependent molecular mechanisms ([

15,

17,

41,

42,

43,

44])

Moreover, ECM1 deficiency correlates with abnormal myofibroblast persistence, excessive collagen I deposition, and impaired re-epithelialization – all classically associated with TGF-β dysregulations [31,45].

3.2. Interplay of ECM1 with TGF-β Pathway

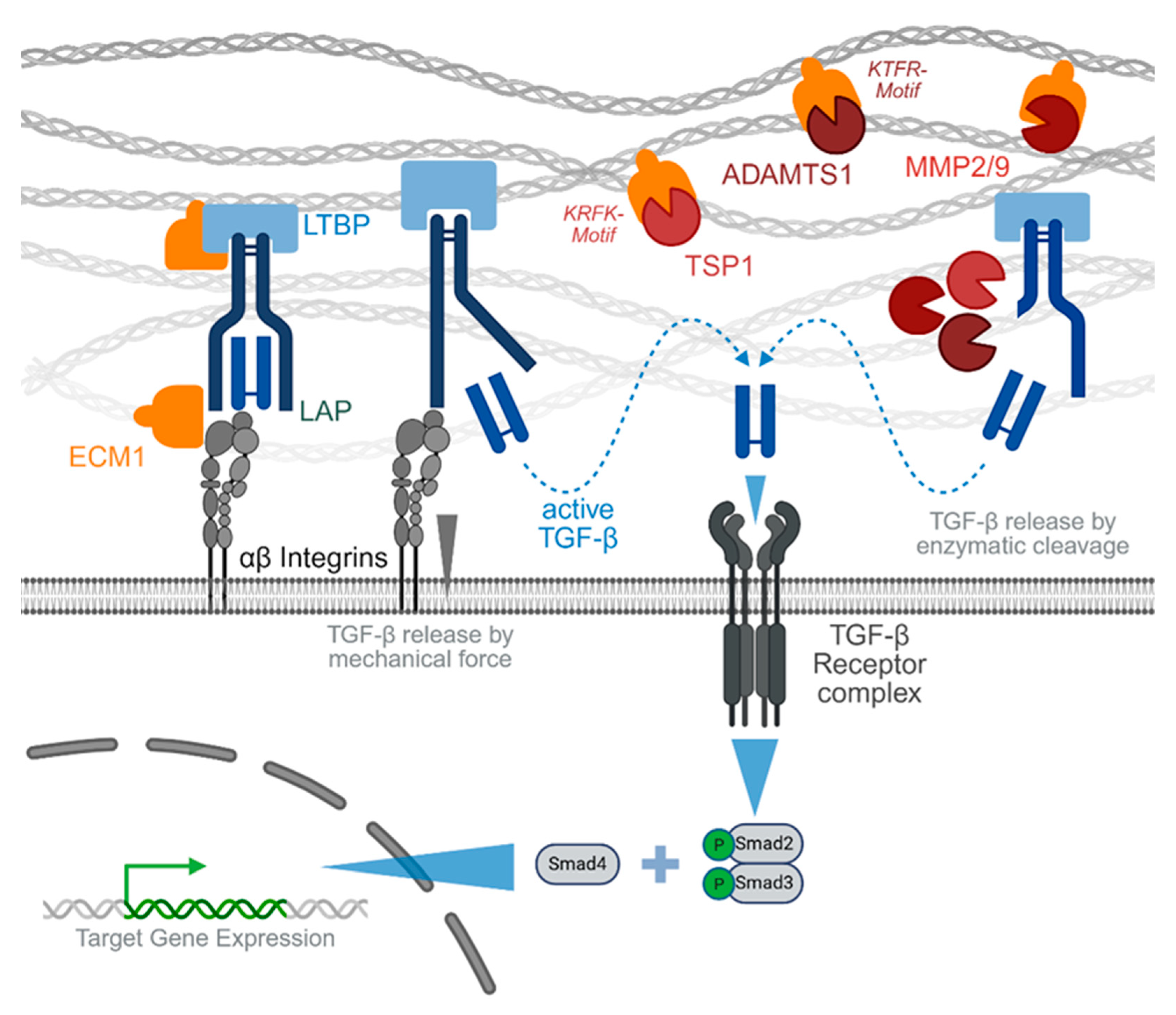

TGF-β, with its three iso-forms (TGF-β1, -β2 and -β3), is by far the most abundant cytokine within the TGF-β superfamily. TGF-β is expressed as a latent protein, the so-called latency-associated peptide (LAP). The LAP is covalently bound to LTBP through disulfide bonds in the endoplasmic reticulum. The resulting large latent complex (LLC) is then incorporated into the extracellular matrix, waiting to be activated either enzymatically by proteolytic cleavage, chemically by a drop in pH, or mechanically by interaction with integrins [

46]. The released active TGF-β dimers transduce their signals through two types of serine/threonine kinase receptors, termed type I and type II [

47]. The type II receptors are constitutively active kinases, which phosphorylate type I receptors upon ligand binding. Seven type I receptors termed activin receptor-like kinase (Alk)-1 through -7 were identified in mammals, of which TGF-β1-3 preferably bind Alk-4 and Alk-5. Upon activation by the type II receptor, Alks activate (phosphorylate) Smad transcription factors in the cytoplasm. TGF-β1-3 activated signaling is mainly mediated via the receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads) -2 and -3, which upon phosphorylation complex with the common-partner Smad (Co-Smad) 4 to enter the nucleus and regulate expression of target genes, including genes participating in feedback mechanisms of the signaling pathway itself [

32,

47] – for overview see

Figure 1.

Mechanistically, ECM-1 modulates TGF-β through regulation of the ECM scaffold and growth factor bioavailability. By binding matrix proteoglycans and interacting with collagen/elastin networks [

41,

42,

43], ECM-1 influences how latent TGF-β binding proteins (LTBPs) store and present TGF-β in tissues [

44]. There are different modes of actions described [

48]. Integrins, such as αvβ3, αvβ5, and αvβ6, can mechanically activate TGF-β by binding connecting the LLC to the contractile cytoskeleton. This requires binding of the Integrins to the RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid) motif in the LAP. It has been reported that ECM1 protects TGF-β from activation by competitively binding to this RGD sequence, thus preventing the interaction of LAP with the integrins [

48]. ECM1 was further reported to interfere with the proteolytic activation of TGF-β by blunting the activity of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMP2 and MMP9), ADAMTS1 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1), and TSP1 (thrombospondin 1) by interacting with their intrinsic KTRF (lysine-tryptophan-arginine-phenylalanine) and KRFK (lysine-phenylalanine-arginine-lysine) motifs, respectively [

40].

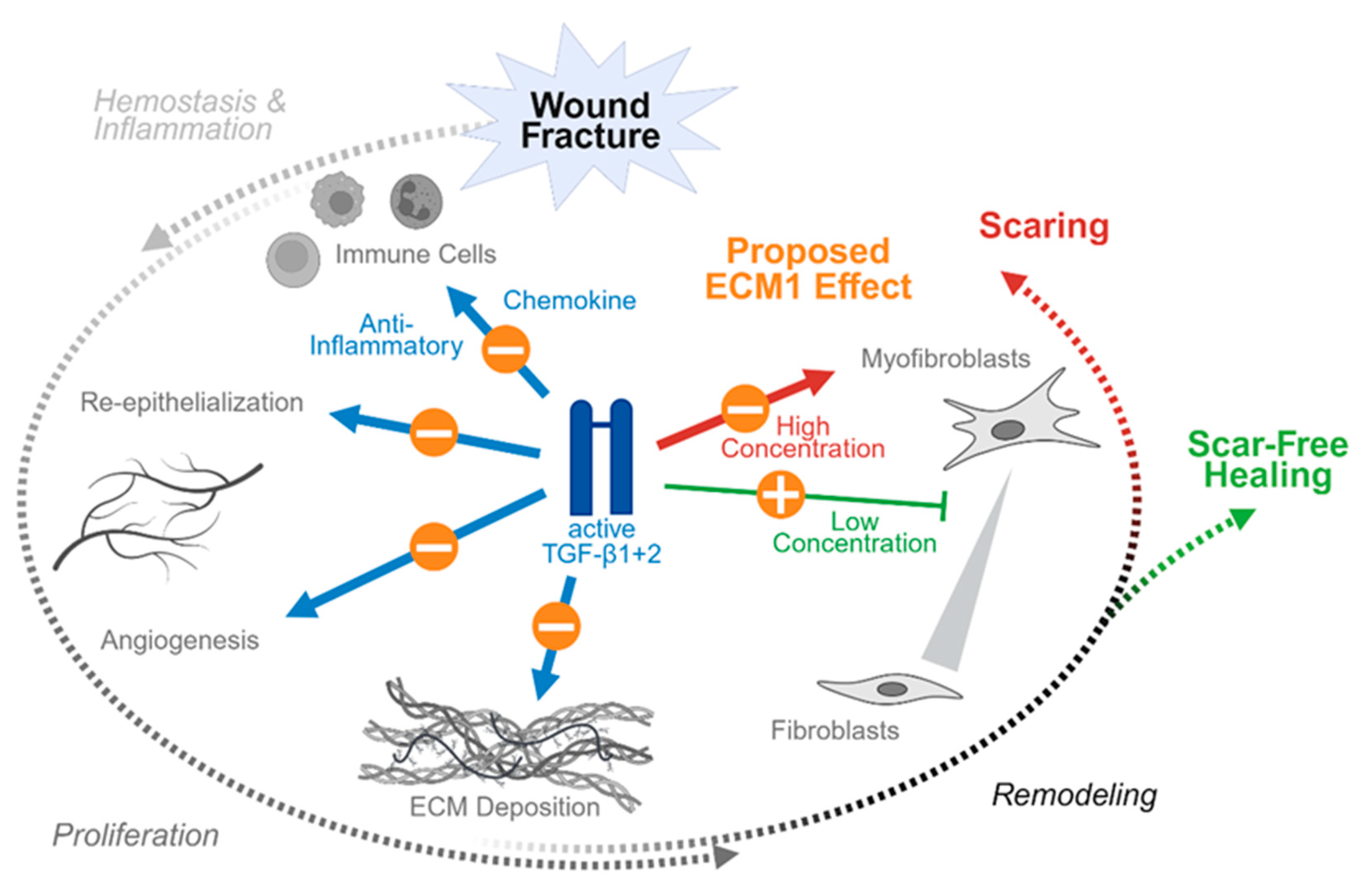

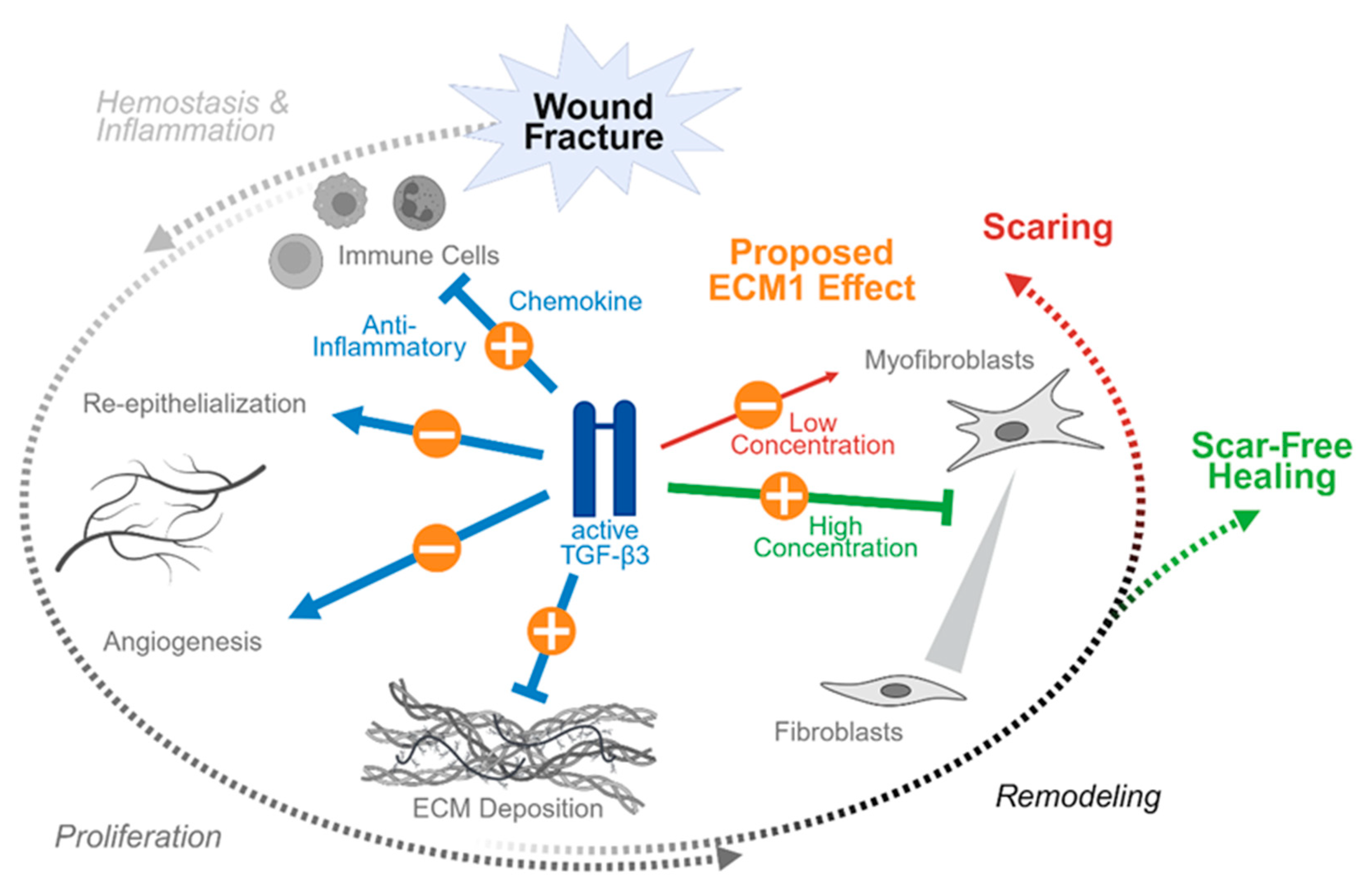

4. Proposed ECM1 Effects During Wound and Fracture Healing

Targeting the ECM1 as extracellular regulator of TGF-β signaling offers potential therapeutic strategies, as ECM1 supplementation via biomaterials or gene therapy could stabilize wound ECM, facilitate controlled angiogenesis, and restore growth factor presentation. However, the proposed effects strongly depend on the healing phase and the predominant TGF-β isoform involved [

49]. While TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 produce similar effects, the effect of TGF-β3 is partly opposite.

Tissue injury typically involves rupture of blood vessels. The resulting exposure of platelets (thrombocytes) to subendothelial collagen leads to platelet aggregation, degranulation and activation of the coagulation cascade. The formed fibrin clot both stops the bleeding and serves as a scaffold for the migration of inflammatory cells into the injured tissue. Upon activation platelets release the content of their granula. Platelet alpha granules are a particularly rich source of active TGF-β isoforms, especially of active TGF-β1, which is up to 100-fold more abundant than in other cell types (TGF-β1 : TGF-β2 : TGF-β3 ratio is 4000 : 1 : 10) [

50]. This results in a rapid and strong local increase in active TGF-β isoforms at the site of tissue damage early during hemostasis. The release TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 act as potent chemoattractants and inflammatory mediators for various types of immune cells, such as neutrophils, mast cells and monocytes (

Figure 2). In the invading neutrophils the ratio of TGFβ isoforms is biased towards TGF-β3 (TGF-β1 : TGF-β2 : TGF-β3 ratio is 12 : 1 : 34) [

51], which is partly antagonizing the effects of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 advancing the healing process towards the proliferation phase (

Figure 3). As during hemostasis and the initial inflammation phase active TGF-β is released by platelets and neutrophils only very mild or even no antagonizing effects of ECM1 are expected. This is in contrast to the following healing phases, which require activation of TGF-β from the ECM.

In the proliferation phase three major events are mediated by TGF-β, namely re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and formation of ECM. All three TGF-β isoforms have been reported to promote re-epithelialization by inducing proliferation and migration of epithelial cells at the wound margins [

51,

52]. However, with one exception for

in vitro experiments, where keratinocyte migration was promoted only by TGF-β1 but not by TGF-β3 [

53]. During the following angiogenesis, the endothelial cells form capillary sprouts that invade the wounded tissue to form a de novo microvascular network. The role for TGF-β as a modulator of angiogenesis is strongly context dependent and includes the recruitment of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-producing hematopoietic effector cells to the site of tissue damage, local induction of VEGF expression [

28,

54] and induction of endothelial to mesenchymal transition [

55]. However, endothelial to mesenchymal transition has also been widely associated with pathological fibrosis of various organs, including the skin [

56]. Finally, all three TGF-β isoforms participate in fibroblast recruitment to the site of injury and their activation to produce the provisional ECM, however, this process is strongly isotype dependent. TGF-β1 is reported to induce collagen production, specifically collagen type I and III. Hence, excessive TGF-β1-mediated signaling has been associated with scaring and the development of keloids [

57]. The less abundant TGF-β2 shows similar effects than TGF-β1, unlike TGF-β3 which appears to be anti-fibrotic [

58].

This isotype-specific effect is enhanced in the following remodeling phase where TGF-β regulates the transition from fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, a population of fibroblasts with contractile phenotype. However, this effect is strongly dose dependent. Myofibroblasts are characterized by the expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA), which is controlled by TGF-β1, both through SMAD-dependent and independent signaling. Thus, suppression of TGF-β1 at this phase of healing supports scar free healing while its induction may favor scar formation by excessive activation of myofibroblast [

27]. Similar to TGFβ1, TGFβ2 promotes the transition of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts both in vitro and in vivo (

Figure 2). The role of TGF-β3, however, is more complex (

Figure 3). It appears to promote myofibroblasts transition in vitro but inhibits the same process in vivo [

58,

59].

Especially in the proliferation and remodeling phase, where TGF-β is activated from the ECM reservoir, a controlled regulation of this process offers multiple options for intervention. ECM1 might establish as an ideal candidate for that, due to its extracellular field of action. Thus it is feasible that timely controlled ECM1 knock-down or neutralization might favor re-vascularization, angiogenesis and ECM deposition, resulting in an accelerated wound closure or fracture healing, as well as a stronger anchoring of implants in the bone. While later in the remodeling phase a controlled ECM1 induction might prevent scar or keloid formation. However, these timely effects require specific biofunctionalization strategies, discussed in the following paragraph.

5. Biofunctionalization Strategies

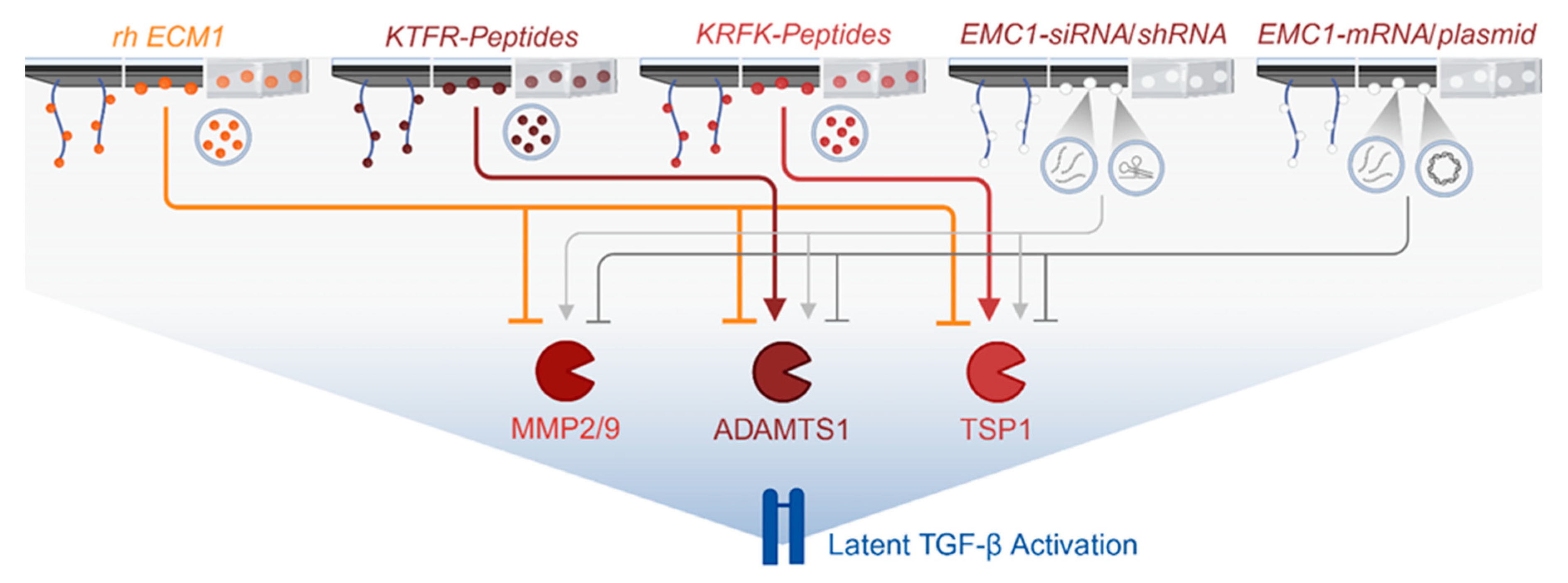

5.1. Protein-, RNA- and DNA-Based Strategies

Biofunctionlalization of implants or hydrogels to induce or neutralize ECM1 effects might be achieved by several strategies, including application of the recombinant human ECM1 protein directly or tetrapeptides, KTRF and KRFK, regulating its interaction with the proteases ADAMTS1 and TSP1 [

40]. Further, Implants might be coated with RNA or DNA products to either induce or suppress ECM1 expression in the surrounding tissues (

Figure 4). While RNA-based methods primarily influence gene expression at the post-transcriptional level [

60], DNA-based strategies typically affect transcription at the genetic or epigenetic level [

61].

Induction of ECM1 expression might be achieved by applying synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) or DNA-based strategies. Based on the fact that the biological stability for DNA is longer than for RNA, the administration of synthetic mRNA is suitable for a short and temporary induction of gene expression [

60]. Importantly, DNA-based gene-delivery may alter the genome itself, depending on the method used – While the use of episomes and plasmids (circular DNA) allows for transient expression of the transferred gene, the use of transposons (“jumping genes”), CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) leads to integration of the gene into the genome, allowing for stable expression of the transferred gene [

61]. When using viral gene delivery, it strongly depends on the viral system used, if the delivered gene integrates (i.a. retroviral or lentiviral based gene-delivery with stable gene expression) or not (i.a. adeno-associated viral gene-delivery with transient gene expression) into the hosts genome [

62].

Suppression or knock-down of ECM1 expression might be achieved by various RNA-based techniques, such as RNA interference (double-stranded RNAs) using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), single-stranded microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), or aptamers (short single-stranded RNA or DNA molecules) [

60], or DNA-based strategies. However, the later usually applied methods such as CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing or CRISPR interference (CRISPRi).

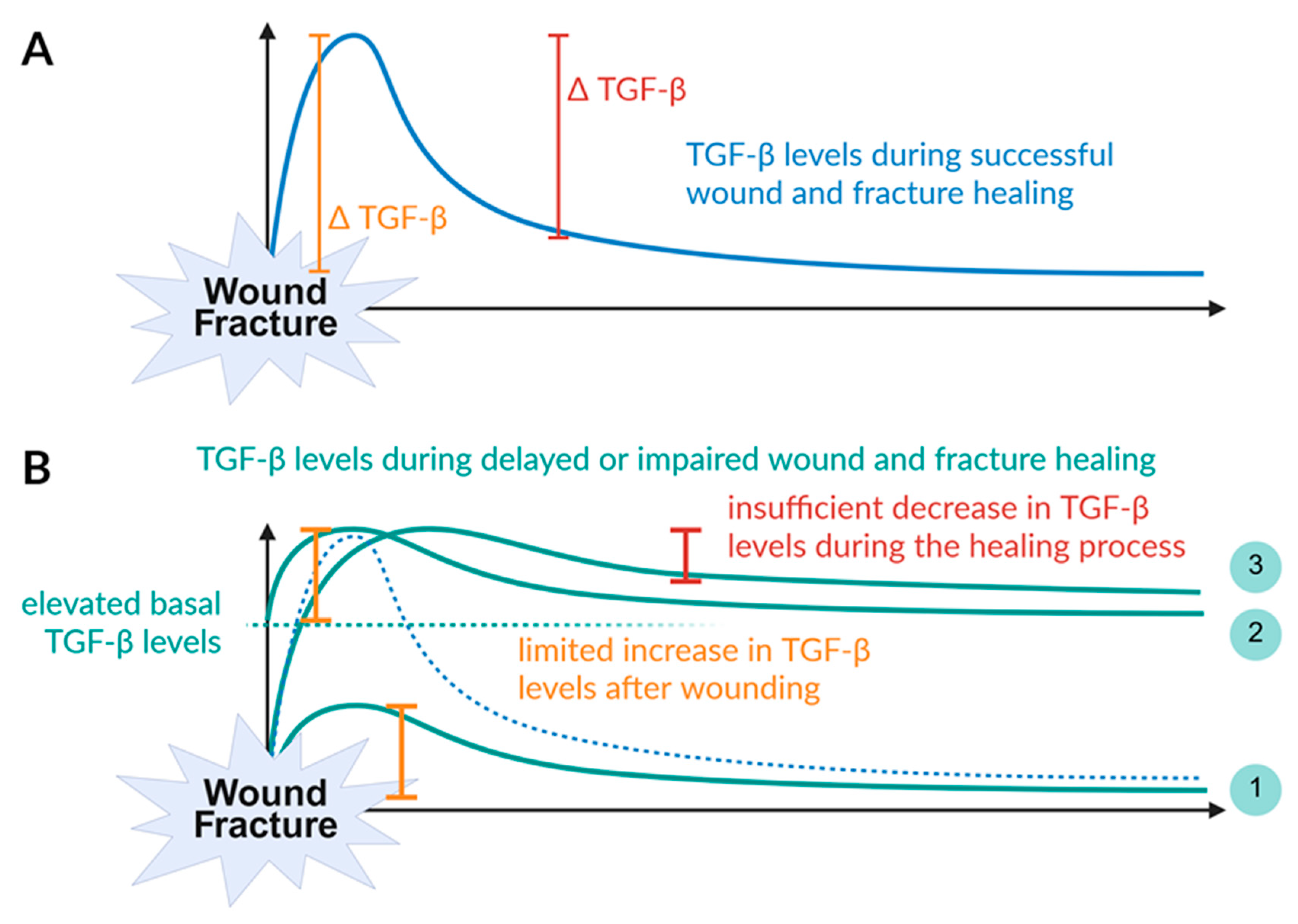

5.2. Alterations in TGF-β Levels Control Phyiological Wound and Fracture Healing ao

As described before physiological wound and fracture healing requires a burst release of active TGF-β from platelets leading to a steep increase in active TGF-β levels at the site of tissue damage during the initial hemostasis [

50]. During the inflammatory phase infiltrating neutrophils then provide more active TGF-β, but with altered isotype composition, inducing negative feedback mechanisms which result in a continuous decline of active TGF-β levels down to basal levels [

51] (

Figure 5A).

When the initial burst increase in active TGF-β levels at the site of tissue damage is disrupted, the subsequent healing cascade may not be adequately initiated, leading to delayed or impaired wound and fracture healing [

63]. This might have different reasons, such as smoking or chronic inflammation. Interesting, although smokers were reported to have increased number of platelets as compared to non-smokers and nicotine possesses the ability to active platelets [

64], smoking has been associated with a suppressed increase in active TGF-β after trauma (

Figure 5B1) [

64]. The situation is different in patients with chronic inflammation, where high levels of active TGF-β are continuously secreted by immune cells. This is mainly observed in obese patients, patients with diabetes mellitus [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71], or patients with fibrotic diseases of the liver, kidney, heart of other tissues [

72,

73,

74]. The resulting elevated basal active TGF-β levels limit the local increase at the site of tissue damage (

Figure 5B2).

Likewise, when the resolution of inflammation fails, the resulting prolonged activation of TGF-β may lead to increased scar or keloid formation [

19], or suppress bone formation by impairing mechanotransduction in osteogenic cells (

Figure 5B3) [

75].

5.2.1. Proposed Use of Recombinant Human ECM1

Recombinant human ECM1 at the implant surface should prevent excessive TGF-β activation. The early hemostasis and inflammatory phase might not be affected by such a coating, as there active TGF-β is released from platelets and immune cells, such as neutrophils. However, during the proliferation phase a lack of TGF-β activation might hinder re-epithelialization, angiogenesis and formation of the provisional ECM, as observed when all three TGF-beta isoforms are neutralized with neutralizing antibodies [

76].

Biomaterial scaffolds mimicking ECM or incorporating ECM fragments has been proposed to enhance wound repair outcomes [

77,

78]. Therefore, an indirect implant coating by peptide bonds or mineral coating that allow timely release of the ECM1 [

79,

80], would be preferable to direct coating techniques, such as spray- or dip-coating. In contrast in the late remodeling phase application of ECM1 might be beneficial to prevent scar or keloid formation in respective risk patients. There the recombinant human ECM1 might be delivered later in the healing phase incorporated in hydrogel wound patches or as peptide-based nanoparticles [

81,

82,

83]. However, in both cases presentation of ECM1 within the extracellular space needs to be provided to ensure its biological function.

5.2.1. Proposed Use of Tetrapeptide Sequences Targeting the Interaction of ECM1 with Proteases

The knowledge of specific motifs either in the ECM1 protein or the interacting proteases offers great perspectives for the modulation of the ECM1 effects. Much of this knowledge is obtained from murine studies on the effect of TGF-β signaling in liver fibrosis. On the one hand, hepatocyte specific knockout of ECM1 caused latent TGF-β1 activation and spontaneously induced liver fibrosis with rapid mortality [

40,

84]. On the other hand, overexpression of ECM1 was able to attenuate liver cirrhosis in mouse models [

85,

86]. In patients with chronic liver disease (CLD), ECM1 expression is inversely associated with the levels of TSP1, ADAMTS1, MMP-2, MMP-9, and LTGF-β1 activation [

40,

87].

Investigating the underlying effects, ECM1 was shown to suppress the activity of the proteases TSP1, ADAMTS1, MMP-2, and MMP-9, all involved in latent TGF-β1 activation. Immunoprecipitation experiments proved that ECM1 is binding directly to these enzymes. In case of TSP1 and ADAMTS1, specific tetrapeptide sequences were identified that control this interaction – the KRFK and KTRF motifs [

40]. Both motifs are proposed to induce a conformational change in the LTGF-β1 molecule, resulting in the release of the active TGF-β1 ligand without the need for additional proteolysis. In line with this, application of KRFK tetrapeptides, which is characteristic for the interaction with TSP1, induced activation of latent TGF-β. This effect was partly attenuated by overexpression of ECM1 [

40]. In contrast, application of KTRF tetrapeptides suppressed activation of latent TGF-β, even in ECM1 knock-out mice [

40].

The knowledge of this opposite effect of these two tetrapeptides offers great perspectives for the biofunctionalization of implants. Especially, as due to their very small size, the tetrapeptides can be applied to the implants in larger amounts than the recombinant human ECM1 by using the same application methods described before. As the KTRF tetrapeptide simulates the ECM1 effect, its application might be beneficial later in the healing cascade when a resolution of the inflammation is required to prevent excessive scar formation. The KRFK tetrapeptides, that were shown to antagonize the ECM1 effects, might exert beneficial effects early in the proliferation phase, such as improves re-epithelialization, angiogenesis and ECM production.

5.2.1. Proposed Use of RNA and DNA-based Methods to Regulate ECM1 Expression

Using RNA or DNA-based methods might have the advantage that the target gene needs to be expressed and secreted by the local cells, which causes a natural delay in the proposed effects. This is of advantage when ECM1 shall be overexpressed, as this is supposed to interfere with the early phases of wound healing. Given this required delay of the proposed effect, this argues for DNA-based rather than RNA-based overexpression of ECM1 – preferably delivered as episomes or plasmids that allow transient expression of the transferred gene without integration into the genome.

In contrast, suppression of ECM1 might be beneficial in the early proliferation phase of the healing cascade, where active TGF-β supports re-epithelialization, angiogenesis and ECM production. There a timelier effect is required, which argues for a RNA-based rather than DNA-based knock-down of ECM1. However, similar to the DNA-based methods, the delivery technique mas have a significant effect on the speed and duration of the response. Usually, lnRNAs and aptamers provide the most rapid response with the shortest duration of the effect, lasting between hours and days. This is due to their short half-life, which for lnRNAs is defined mainly by their primary and secondary structure, but also by their interaction with other proteins within the cellular context [

88]. The half-life of aptamers, in contrast, is defined by renal clearance and nuclease degradation. However, their half-life and therapeutic effect can be extended through modifications such as PEGylation, which increases their size and resistance to nucleases [

89]. An intermediate effect duration (~5 days) is expected from miRNAs, which have an average half-life of about 5 days. Their stability is enhanced when forming a complex with the argonaute proteins as part of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [

90]. Synthetic miRNAs follow the same degradation kinetics as siRNAs, thus the expected effect duration is also comparable (5 to 7 days). A more persistent effect is obtained by shRNAs that are often expressed from a plasmid or viral vector by the host cells. Ths might be even permanent, when the delivery method includes integration into the hosts’ genome [

91], however, this is unfavorable for therapeutic use.

6. Conclusion

Wound healing depends on tightly regulated TGF-β pathway activity, orchestrated by ECM components, proteases, and receptor modulators. ECM1 emerges as a critical stabilizer of this system, ensuring balanced growth factor availability and matrix organization. As a protein predominantly localized within the ECM, ECM1 is a highly promising candidate for the biofunctionalization of implants due to its principal actions within the extracellular space. In light of its proposed mechanisms, several approaches for biofunctionalization are feasible: Direct strategies include the application of rh-ECM1 or the tetrapeptides KTFR and KFRK. Indirect strategies may utilize RNA- or DNA-based techniques—such as siRNAs, shRNAs, aptamers, messenger RNA, or plasmids—to achieve knockdown or overexpression of ECM1. These molecules can be delivered to implants either alone, with the aid of polymers or vesicles, or incorporated into hydrogels.

Depending on the selected strategy, the delivered protein/peptide, RNA, or DNA may either activate or inhibit the proteases ADAMTS1, MMP2, and MMP9, as well as TSP1, which are involved in the proteolytic release of active TGF-β from its latent complex. Ultimately, leveraging the modulatory capacity of ECM1 in wound and fracture healing—via its regulation of TGF-β signaling—holds significant promise for addressing the substantial clinical challenges posed by non-unions, impaired wound healing, and chronic wounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R.B. and S.E.; literature research and validation, N.R.B. and S.E.; resources, A.K.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R.B.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, S.E.; supervision, A.K.N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable – review article.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable – review article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable – review article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADAMTS1 |

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1 |

| Alk |

activin receptor-like kinase |

| CLD |

chronic liver disease |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| ECM |

extracellular matrix |

| BAMBI |

BMP and Activin Membrane-Bound Inhibitor |

| ECM1 |

Extracellular matrix protein-1 |

| HTRA1 |

high temperature requirement factor A1 |

| KRFK |

lysine-phenylalanine-arginine-lysine |

| KTRF |

lysine-tryptophan-arginine-phenylalanine |

| LAP |

latency-associated peptide |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| LLC |

large latent complex |

| LTBP |

latent TGF-β binding protein |

| LTGF-β1 |

latent TGF-β1 |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MMP |

matrix metalloproteinases |

| RGD |

arginine-glycine-aspartic acid |

| shRNAs |

small hairpin RNAs |

| siRNAs |

small interfering RNAs |

| Smad |

small mothers against decapentaplegic |

| TGF-β |

transforming growth factor-beta |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| TSP1 |

thrombospondin 1 |

| VEGF |

vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- C. M. Court-Brown and B. Caesar, “Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review,” Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- E. W. Unger et al., “Development of a dynamic fall risk profile in elderly nursing home residents: A free field gait analysis based study,” Arch Gerontol Geriatr, vol. 93, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- O. Ström et al., “Osteoporosis: Burden, health care provision and opportunities in the EU,” Arch Osteoporos, vol. 6, no. 1–2, pp. 59–155, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Wu et al., “Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,” Lancet Healthy Longev, vol. 2, no. 9, pp. e580–e592, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Einhorn and L. C. Gerstenfeld, “Fracture healing: Mechanisms and interventions,” Jan. 01, 2015, Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Mills, S. A. Aitken, and A. H. R. W. Simpson, “The risk of non-union per fracture: current myths and revised figures from a population of over 4 million adults,” Acta Orthop, vol. 88, no. 4, pp. 434–439, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Braun et al., “Increased therapy demand and impending loss of previous residence status after proximal femur fractures can be determined by continuous gait analysis – A clinical feasibility study,” Injury, vol. 50, no. 7, pp. 1329–1332, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Baumgarten et al., “Pressure ulcers in elderly patients with hip fracture across the continuum of care: Clinical investigations,” J Am Geriatr Soc, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 863–870, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Haleem, G. Heinert, and M. J. Parker, “Pressure sores and hip fractures,” Injury, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 219–223, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. Martinengo et al., “Prevalence of chronic wounds in the general population: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies,” Jan. 01, 2019, Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- B. Chan, S. Cadarette, W. Wodchis, J. Wong, N. Mittmann, and M. Krahn, “Cost-of-illness studies in chronic ulcers: a systematic review,” J Wound Care, vol. 26, no. sup4, pp. S4–S14, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Sen, “Human Wound and Its Burden: Updated 2020 Compendium of Estimates,” May 01, 2021, Mary Ann Liebert Inc. [CrossRef]

- G. Victoria, B. Petrisor, B. Drew, and D. Dick, “Bone stimulation for fracture healing: What′s all the fuss?,” in Indian Journal of Orthopaedics, Apr. 2009, pp. 117–120. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Hak et al., “Delayed union and nonunions: Epidemiology, clinical issues, and financial aspects,” Injury, vol. 45, no. SUPPL. 2, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Midwood, L. V. Williams, and J. E. Schwarzbauer, “Tissue repair and the dynamics of the extracellular matrix,” 2004, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- R. O. Hynes, “The extracellular matrix: Not just pretty fibrils,” Nov. 27, 2009. [CrossRef]

- F. X. Maquart and J. C. Monboisse, “Extracellular matrix and wound healing,” Pathologie Biologie, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 91–95, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A.B. Roberts, B. K. McCune, and M. B. Sporn, “TGF-β: Regulation of extracellular matrix,” in Kidney International, 1992, pp. 557–559. [CrossRef]

- S. Liarte, Á. Bernabé-García, and F. J. Nicolás, “Role of TGF-β in Skin Chronic Wounds: A Keratinocyte Perspective,” Jan. 28, 2020, NLM (Medline). [CrossRef]

- M. Pakyari, A. Farrokhi, M. K. Maharlooei, and A. Ghahary, “Critical Role of Transforming Growth Factor Beta in Different Phases of Wound Healing,” Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle), vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 215–224, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. W. D. Gilbert, M. K. Vickaryous, and A. M. Viloria-Petit, “Signalling by transforming growth factor beta isoforms in wound healing and tissue regeneration,” Jun. 01, 2016, MDPI Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Diegelmann and M. C. Evans, “WOUND HEALING: AN OVERVIEW OF ACUTE, FIBROTIC AND DELAYED HEALING,” 2004.

- S. Guo and L. A. DiPietro, “Critical review in oral biology & medicine: Factors affecting wound healing,” J Dent Res, vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 219–229, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- T. Velnar, T. Bailey, and V. Smrkolj, “The Wound Healing Process: an Overview of the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms,” 2009.

- S. M. Wahl et al., “Transforming growth factor type 13 induces monocyte chemotaxis and growth factor production,” 1987. [Online]. Available: https://www.pnas.org.

- S. Ellis, E. J. Lin, and D. Tartar, “Immunology of Wound Healing,” Dec. 01, 2018, Current Medicine Group LLC 1. [CrossRef]

- B. Hinz, “Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair,” 2007, Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- S. Fang, N. Pentinmikko, M. Ilmonen, and P. Salven, “Dual action of TGF-β induces vascular growth in vivo through recruitment of angiogenic VEGF-producing hematopoietic effector cells,” Angiogenesis, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 511–519, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Tonnesen, 2 Xiaodong Feng, and R. A. F. Clark, “Angiogenesis in Wound Healing,” 2000.

- C. J. Morrison, G. S. Butler, D. Rodríguez, and C. M. Overall, “Matrix metalloproteinase proteomics: substrates, targets, and therapy,” Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhang et al., “Current potential therapeutic strategies targeting the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway to attenuate keloid and hypertrophic scar formation,” Sep. 01, 2020, Elsevier Masson s.r.l. [CrossRef]

- S. Ehnert et al., “Transforming growth factor β1inhibits bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-2 and BMP-7 signaling via upregulation of Ski-related novel protein N (SnoN): Possible mechanism for the failure of BMP therapy?,” BMC Med, vol. 10, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guang CHEN and A. Ming MENG, “Negative regulation of TGF-β signaling in development,” 2004. [Online]. Available: http://www.cell-research.com.

- D. Onichtchouk et al., “Silencing of TGF-β signalling by the pseudoreceptor BAMBI,” Nature, vol. 401, no. 6752, pp. 480–485, Sep. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fan et al., “BAMBI elimination enhances alternative TGF-b signaling and glomerular dysfunction in diabetic mice,” Diabetes, vol. 64, no. 6, pp. 2220–2233, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Lichtman, M. Otero-Vinas, and V. Falanga, “Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) isoforms in wound healing and fibrosis,” Mar. 01, 2016, Blackwell Publishing Inc. [CrossRef]

- S. Sercu et al., “Interaction of extracellular matrix protein 1 with extracellular matrix components: ECM1 is a basement membrane protein of the skin,” Journal of Investigative Dermatology, vol. 128, no. 6, pp. 1397–1408, 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Sercu et al., “ECM1 interacts with fibulin-3 and the beta 3 chain of laminin 332 through its serum albumin subdomain-like 2 domain,” Matrix Biology, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 160–169, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y. L. Liu, Z. Y. O. Zhang, and X. M. Chen, “A Sporadic Family of Lipoid Proteinosis with Novel ECM1 Gene Mutations,” Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol, vol. 17, pp. 885–889, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Link et al., “ECM1 Attenuates Hepatic Fibrosis by Interfering with Mediators of Latent TGF-β1 Activation,” Dec. 12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Tracy, R. A. Minasian, and E. J. Caterson, “Extracellular Matrix and Dermal Fibroblast Function in the Healing Wound,” Mar. 01, 2016, Mary Ann Liebert Inc. [CrossRef]

- P. Rousselle, M. Montmasson, and C. Garnier, “Extracellular matrix contribution to skin wound re-epithelialization,” Jan. 01, 2019, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- C. Frantz, K. M. Stewart, and V. M. Weaver, “The extracellular matrix at a glance,” Dec. 15, 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. Beaufort et al., “Cerebral small vessel disease-related protease HtrA1 processes latent TGF-β binding protein 1 and facilitates TGF-β signaling,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 111, no. 46, pp. 16496–16501, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Secker, A. J. Shortt, E. Sampson, Q. P. Schwarz, G. S. Schultz, and J. T. Daniels, “TGFβ stimulated re-epithelialisation is regulated by CTGF and Ras/MEK/ERK signalling,” Exp Cell Res, vol. 314, no. 1, pp. 131–142, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Bonewald and S. L. Dallas, “Role of active and latent transforming growth factor β in bone formation,” J Cell Biochem, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 350–357, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shi and J. Massagué, “Review Mechanisms of TGF-Signaling from Cell Membrane to the Nucleus have been observed in both TGF-family receptors and the Smad proteins. The TGF-type II receptor is inacti-vated by mutation in most human gastrointestinal can,” 2003.

- M. Shi et al., “Latent TGF-β structure and activation,” Nature, vol. 474, no. 7351, pp. 343–351, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. W. D. Gilbert, M. K. Vickaryous, and A. M. Viloria-Petit, “Signalling by transforming growth factor beta isoforms in wound healing and tissue regeneration,” Jun. 01, 2016, MDPI Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- A. Meyer et al., “Platelet TGF-β1 contributions to plasma TGF-β1, cardiac fibrosis, and systolic dysfunction in a mouse model of pressure overload,” Blood, vol. 119, no. 4, pp. 1064–1074, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Grainger, D. E. Mosedale, and J. C. Metcalfe, “TGF-b in blood: a complex problem.” [Online]. Available: www.elsevier.com/locate/cytogfr.

- T. A. Mustoe, G. F. Pierce, A. Thomason, P. Gramates, M. B. Sporn, and T. F. Deuel, “Accelerated Healing of Incisional Wounds in Rats Induced by Transforming Growth Factor-β,” Science (1979), vol. 237, no. 4820, pp. 1333–1336, Sep. 1987. [CrossRef]

- M. Le et al., “Transforming Growth Factor Beta 3 Is Required for Excisional Wound Repair In Vivo,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 10, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Mercado-Pimentel and R. B. Runyan, “Multiple transforming growth factor-β isoforms and receptors function during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart,” in Cells Tissues Organs, Jun. 2007, pp. 146–156. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Welch-Reardon et al., “Angiogenic sprouting is regulated by endothelial cell expression of Slug,” J Cell Sci, vol. 127, no. 9, pp. 2017–2028, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Piera-Velazquez, F. A. Mendoza, and S. A. Jimenez, “Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EndoMT) in the pathogenesis of human fibrotic diseases,” Apr. 11, 2016, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Chin et al., “Differential Expression of Transforming Growth Factor-β Receptors I and II and Activation of Smad 3 in Keloid Fibroblasts,” Plast Reconstr Surg, vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 423–429, Aug. 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. Shah, D. M. Foreman, and M. W. J. Ferguson, “Neutralisation of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 or exogenous addition of TGF-β3 to cutaneous rat wounds reduces scarring,” J Cell Sci, vol. 108, no. 3, pp. 985–1002, Mar. 1995. [CrossRef]

- G. Serini and G. Gabbiani, “Modulation of α-smooth muscle actin expression in fibroblasts by transforming growth factor-β isoforms: An in vivo and in vitro study,” Wound Repair and Regeneration, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 278–287, 1996. [CrossRef]

- O. Khorkova, J. Stahl, A. Joji, C. H. Volmar, and C. Wahlestedt, “Amplifying gene expression with RNA-targeted therapeutics,” Jul. 01, 2023, Nature Research. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Tsai et al., “Current strategies employed in the manipulation of gene expression for clinical purposes,” Dec. 01, 2022, BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- S. Mali, “Delivery systems for gene therapy,” Indian J Hum Genet, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 3, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Zimmermann et al., “TGF-β1 as a marker of delayed fracture healing,” Bone, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 779–785, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Pujani, V. Chauhan, K. Singh, S. Rastogi, C. Agarwal, and K. Gera, “The effect and correlation of smoking with platelet indices, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio,” Hematol Transfus Cell Ther, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 424–429, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Kanzler et al., “Prediction of progressive liver fibrosis in hepatitis C infection by serum and tissue levels of transforming growth factor-β,” J Viral Hepat, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 430–437, 2001. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Gressner, “Roles of TGF-beta in hepatic fibrosis,” Frontiers in Bioscience, vol. 7, no. 4, p. A812, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Y. C. Qiao et al., “Changes of Regulatory T Cells and of Proinflammatory and Immunosuppressive Cytokines in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” 2016, Hindawi Limited. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Chen et al., “Specific targeting of TGF-β family ligands demonstrates distinct roles in the regulation of muscle mass in health and disease,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 114, no. 26, pp. E5266–E5275, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. B. Shi et al., “Transforming growth factor beta1 from endometriomas promotes fibrosis in surrounding ovarian tissues via Smad2/3 signaling†,” Biol Reprod, vol. 97, no. 6, pp. 873–882, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Ehnert et al., “Factors circulating in the blood of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients affect osteoblast maturation - Description of a novel in vitro model,” Exp Cell Res, vol. 332, no. 2, pp. 247–258, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Freude et al., “Hyperinsulinemia reduces osteoblast activity in vitro via upregulation of TGF-β,” J Mol Med, vol. 90, no. 11, pp. 1257–1266, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. H. Epstein, W. A. Border, and N. A. Noble, “Transforming Growth Factor β in Tissue Fibrosis,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 331, no. 19, pp. 1286–1292, Nov. 1994. [CrossRef]

- A. V. Fedulov et al., “Serum TGF-Beta 1 and TNF-Alpha Levels and Cardiac Fibrosis in Experimental Chronic Renal Failure,” Immunol Invest, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 143–152, Jan. 2005. [CrossRef]

- A. Leask, “TGFβ, cardiac fibroblasts, and the fibrotic response,” May 01, 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Ehnert et al., “TGF-β1 impairs mechanosensation of human osteoblasts via HDAC6-mediated shortening and distortion of primary cilia,” J Mol Med, vol. 95, no. 6, pp. 653–663, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Lu et al., “The Temporal Effects of Anti-TGF-β1, 2, and 3 Monoclonal Antibody on Wound Healing and Hypertrophic Scar Formation,” J Am Coll Surg, vol. 201, no. 3, pp. 391–397, Sep. 2005. [CrossRef]

- E. Traversa et al., “Tuning hierarchical architecture of 3D polymeric scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering,” in Journal of Experimental Nanoscience, Jun. 2008, pp. 97–110. [CrossRef]

- C. Chocarro-Wrona, E. López-Ruiz, M. Perán, P. Gálvez-Martín, and J. A. Marchal, “Therapeutic strategies for skin regeneration based on biomedical substitutes,” Mar. 01, 2019, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Lee, D. Suarez-Gonzalez, and W. L. Murphy, “Mineral coatings for temporally controlled delivery of multiple proteins,” Advanced Materials, vol. 23, no. 37, pp. 4279–4284, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Talebian et al., “Biopolymeric Coatings for Local Release of Therapeutics from Biomedical Implants,” Apr. 26, 2023, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- S. Saeed et al., “Flexible Topical Hydrogel Patch Loaded with Antimicrobial Drug for Accelerated Wound Healing,” Gels, vol. 9, no. 7, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Thongpon, M. Tang, and Z. Cong, “Peptide-Based Nanoparticle for Tumor Therapy,” Jun. 01, 2025, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- J. H. Yen, C. C. Chang, T. Y. Wu, C. H. Yang, H. J. Hsu, and J. W. Liou, “Therapeutic peptides and their delivery using lipid-based nanoparticles,” Jul. 01, 2025, Wolters Kluwer Medknow Publications. [CrossRef]

- W. Fan et al., “ECM1 Prevents Activation of Transforming Growth Factor β, Hepatic Stellate Cells, and Fibrogenesis in Mice,” Gastroenterology, vol. 157, no. 5, pp. 1352-1367.e13, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang et al., “ECM1 protects against liver steatosis through PCBP1-mediated iron homeostasis,” Hepatology, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu et al., “ECM1 modified HF-MSCs targeting HSC attenuate liver cirrhosis by inhibiting the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway,” Cell Death Discov, vol. 8, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Cichon and D. C. Radisky, “Extracellular matrix as a contextual determinant of transforming growth factor-b signaling in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and in cancer http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.4161/19336918.2014.972788,” Nov. 01, 2014, Landes Bioscience. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Yoon, J. Kim, and M. Gorospe, “Long noncoding RNA turnover,” Oct. 15, 2015, Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Kovacevic, J. C. Gilbert, and B. Jilma, “Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of aptamers,” Sep. 01, 2018, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- G. Hutvagner and M. J. Simard, “Argonaute proteins: Key players in RNA silencing,” Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Subramanya, S. S. Kim, N. Manjunath, and P. Shankar, “RNA interference-based therapeutics for human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1 treatment: Synthetic siRNA or vector-based shRNA?,” Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).