1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of new energy vehicles (NEVs), there is growing demand for efficient and reliable thermal management systems to ensure optimal vehicle performance and safety. Effective battery temperature control remains a critical challenge in NEV operation. Non-optimal operating temperatures can diminish efficiency and accelerate battery degradation, while excessively high temperatures may induce thermal runaway and other safety hazards [

1,

2].

Phase change materials (PCMs), leveraging their high latent heat, effectively absorb and release heat during phase transitions, making them widely employed in thermal management systems for NEVs [

1]. Huang [

3] and Ashima [

4] demonstrated that passive phase change cooling ensures superior temperature regulation and uniformity in lithium-ion battery modules. Additional passive thermal management approaches utilizing PCM latent heat include immersion cooling [

5,

6], sleeve-type cooling [

7], and encapsulation cooling [

8]. However, despite enhancements in thermal conductivity achievable through the incorporation of high-conductivity materials into composite PCMs, their intrinsic thermal transfer properties remain relatively low. Consequently, upon reaching the latent heat storage capacity, PCMs can impede the battery system’s heat dissipation performance. Studies indicate that a single-PCM thermal reservoir is inadequate for meeting the thermal management requirements of EV power batteries. Integration with auxiliary cooling mechanisms is therefore essential to facilitate the timely dissipation of heat stored within the PCM, thereby enhancing the system’s overall cooling efficiency. Park [

9] developed a numerical model comparing an active thermal management system using two-phase refrigerants with a passive PCM-based system for lithium-ion batteries. Simulation results from combined charge-discharge cycling tests indicated that the active refrigerant cooling system achieved higher cooling efficiency than the passive PCM system. Fu [

10] proposed a novel structural design for a power battery thermal management system. This design integrates PCMs, liquid cooling, and air cooling for heat dissipation under high-temperature conditions, and incorporates electric resistance heating for temperature regulation in low-temperature environments, offering a new strategy for EV battery thermal management. Liu [

11] developed a heat dissipation module based on a composite PCM combined with liquid cooling. By modifying the connection configuration of the liquid cooling system’s hoses, different coupling schemes can be implemented, demonstrating significantly enhanced cooling performance compared to systems relying solely on PCMs for heat dissipation.

Despite the significant advantages of PCMs in thermal management, their application in NEVs faces substantial challenges. A primary limitation is their low thermal conductivity [

12], which restricts the rate of heat absorption and release. Conventional PCM-based thermal management systems often necessitate incorporating thermal conductivity enhancers (such as metallic fins or nanoparticles) or implementing complex structural modifications to augment heat transfer rates. Unfortunately, these enhancements typically increase system weight and complexity, conflicting with the critical requirements for lightweight and compact designs in NEVs [

13]. Consequently, PCM-based thermal management systems have thus far been hindered from achieving widespread adoption.

In contrast, the PCM-EST offers a promising thermal management solution for NEVs. Its advantages encompass flexible design, adaptable layout, and the potential to partially substitute liquid cooling circuits, thereby minimizing weight addition. For instance, Song [

14] utilized PCM-EST to recover fuel cell waste heat for cabin heating, reducing air conditioning energy consumption by 26%. However, maximizing the thermal benefits of PCM within the PCM-EST critically depends on its structural design. Common enhancement strategies involve integrating fins, expanding surface areas, or incorporating porous structures within the storage tube to augment heat exchange between the PCM and the heat transfer fluid (HTF) [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Optimizing fin geometric parameters—such as shape, quantity, and size—significantly improves system heat transfer performance. Specifically, fin number profoundly impacts PCM melting and solidification characteristics due to its direct influence on the heat transfer area

. Al-Abidi et al. [

19] investigated internal and external fins in a triple-tube heat exchanger, revealing that increasing fin number and height markedly accelerated PCM melting. Hosseini et al. [

20] experimentally and numerically validated that optimized fin geometries and arrangements enhance heat transfer rates while maintaining compactness. Yan et al. [

21] demonstrated numerically that Y-shaped fins in a triple-tube latent heat thermal energy storage (LHTES) system expedite PCM heat storage; reducing fin thickness and increasing branch fin angles shortened total charging time. Hong et al. [

22] introduced an innovative T-shaped fin strategy, extending fin length to enhance PCM heat sink thermal management. This approach reduced melting time by 25.5% compared to a finless system, indicating significant efficiency gains. Peng et al. [

23] examined the impact of branched rectangular fin cross-angle and installation height on organic PCM melting, collaboratively optimizing transient conduction and natural convection. Mostafa et al. [

24] proposed a system integrating rectangular and triangular fins, achieving a substantial ~57.56% increase in PCM melting rate. Waqas et al. [

25] highlighted that vein fin structures significantly outperform other designs in PCM melting performance; using 8 vein fins increased the melting rate by 91% within 1000 seconds compared to the finless case.

Furthermore, optimization techniques are crucial for designing PCM-EST systems, balancing thermal performance against structural constraints. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations are widely employed to model complex PCM heat transfer processes, enabling exploration of design parameter impacts [

26]. However, due to the high computational cost of precise simulations, surrogate models (e.g., Kriging model) have gained prominence for approximating PCM system performance, reducing computational effort and enhancing optimization efficiency [

27,

28,

29,

30].Jiang et al. [

28] utilized a Kriging surrogate model combined with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to optimize a composite PCM/expanded graphite system for lithium-ion battery thermal management, significantly improving heat transfer and reducing costs. Bianco et al. [

31] employed genetic algorithms (GA) with MATLAB-COMSOL Multiphysics numerical models, finding that reducing the shell diameter by 12 cm utilized 72% of the PCM potential, with the maximum fully available PCM being 40% of the initial amount.Liu et al. [

32] applied the particle swarm optimization algorithm to optimize a tubular heat exchanger, obtaining the optimal fin cross-angle and branching ratio. This increased PCM heat transfer efficiency by 27.9%, with the optimized design validated for accuracy.

Despite significant advances in PCM-based thermal management systems, current research predominantly concentrates on optimizing isolated design elements—such as fin geometry or material properties—often overlooking the complex interactions between multiple parameters [

33,

34]. Furthermore, most strategies aimed at enhancing heat transfer efficiency achieve these gains at the expense of increased system weight and complexity [

35,

36,

37,

38], conflicting directly with the imperative for lightweight, highly efficient compact designs in new energy vehicles.These limitations prevent fins from realizing their full heat transfer potential, yielding suboptimal efficiency improvements in PCM systems. This approach also contributes to material wastage and unnecessary mass accumulation. Existing studies further lack systematic analysis of optimization outcomes and fail to resolve compatibility issues between fin designs and heat exchanger architectures.To bridge these gaps, this study proposes a Multi-objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) framework for parameter optimization of energy storage tubes. This methodology enables simultaneous achievement of structural lightweighting, system simplification, and compliance with prescribed thermal performance requirements.

This study aims to optimize the design of PCM-ESTs for thermal management systems in NEV batteries, focusing on enhancing heat transfer performance while achieving structural lightweighting. Specifically, we investigate the influence of key geometric parameters—including fin number, fin height ratio, and inner tube diameter and length—on both the weight of the heat storage tube and its comprehensive heat exchange capacity. These parameters affect the heat transfer coefficient by altering the heat exchange area but concurrently increase system mass. Thus, maximizing thermal potential while minimizing weight constitutes a critical design challenge. Through integrated CFD simulations, MOPSO and Kriging surrogate modeling, this work systematically analyzes the impact of geometric parameters on PCM thermal behavior during melting and solidification. The study identifies the optimal PCM-EST configuration that balances heat transfer efficiency with mass reduction. The resulting framework offers a novel approach for PCM-EST design, addressing the dual challenge of improving thermal performance and reducing weight in battery thermal management systems. The optimized design is expected to enhance battery temperature regulation while improving overall energy efficiency and sustainability through reduced energy consumption and material usage. This research provides innovative solutions and actionable insights for advancing thermal management technologies, supporting the broader adoption of new energy vehicles.

2. PCM-EST Structure and Parameter Design

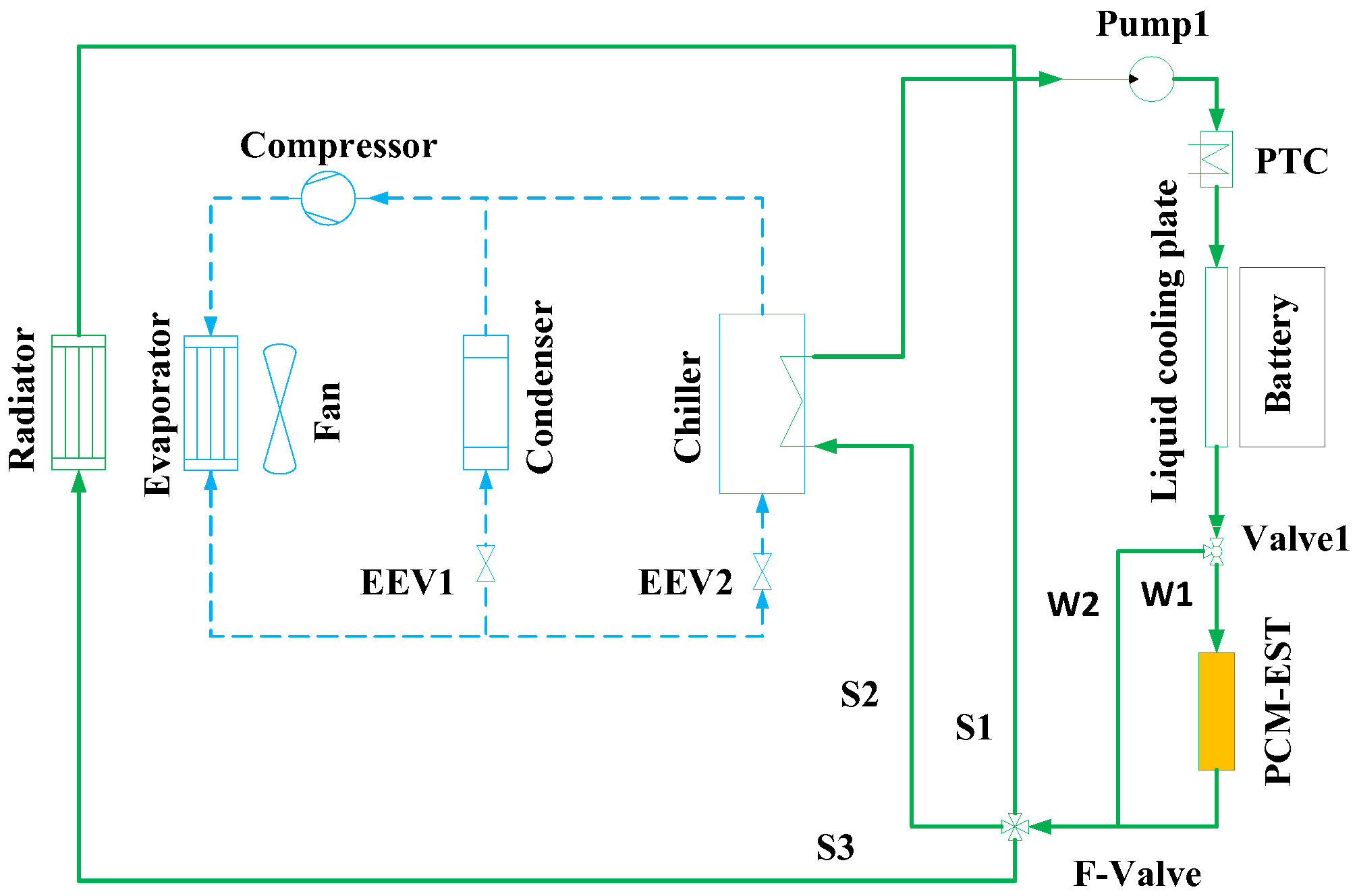

Figure 1 illustrates the configuration of the PCM-EST within the electric vehicle BTMS. The system comprises two interconnected loops: ①Air Conditioning Loop: compressor, evaporator, condenser, expansion valve, and heat exchanger.②Battery Thermal Management Loop: battery liquid cooling plate, water pump, PTC heater, radiator, PCM-EST, three-way valve, and four-way valve.

Positioned at the battery cooling fluid outlet, the three-way valve divides the flow into two branches (W1 and W2). These branches converge at the four-way valve, which directs the combined flow through three distinct cooling circuits: S1: No cooling;S2: Weak cooling;S3: Strong cooling.All circuits (S1-S3) subsequently reconverge and return to the pump inlet, completing the circulation loop. The PCM-EST unit in this study is installed within branch W1, where it dynamically absorbs or releases heat to regulate battery temperature and reduce overall thermal management system energy consumption.

The operational logic functions as follows: ① Low Battery Temperature:heat stored in the PCM-EST (W1 branch) supplements the PTC heater to warm the battery coolant.Reduces PTC power demand while accelerating battery heating.② High Battery Temperature: when PCM-EST is cool: absorbs battery heat while simultaneously warming the PCM;When PCM-EST is hot: activate radiator (S3 branch) for heat dissipation, or engage chiller (S2 branch) for forced battery cooling.

2.1. PCM-EST Structure

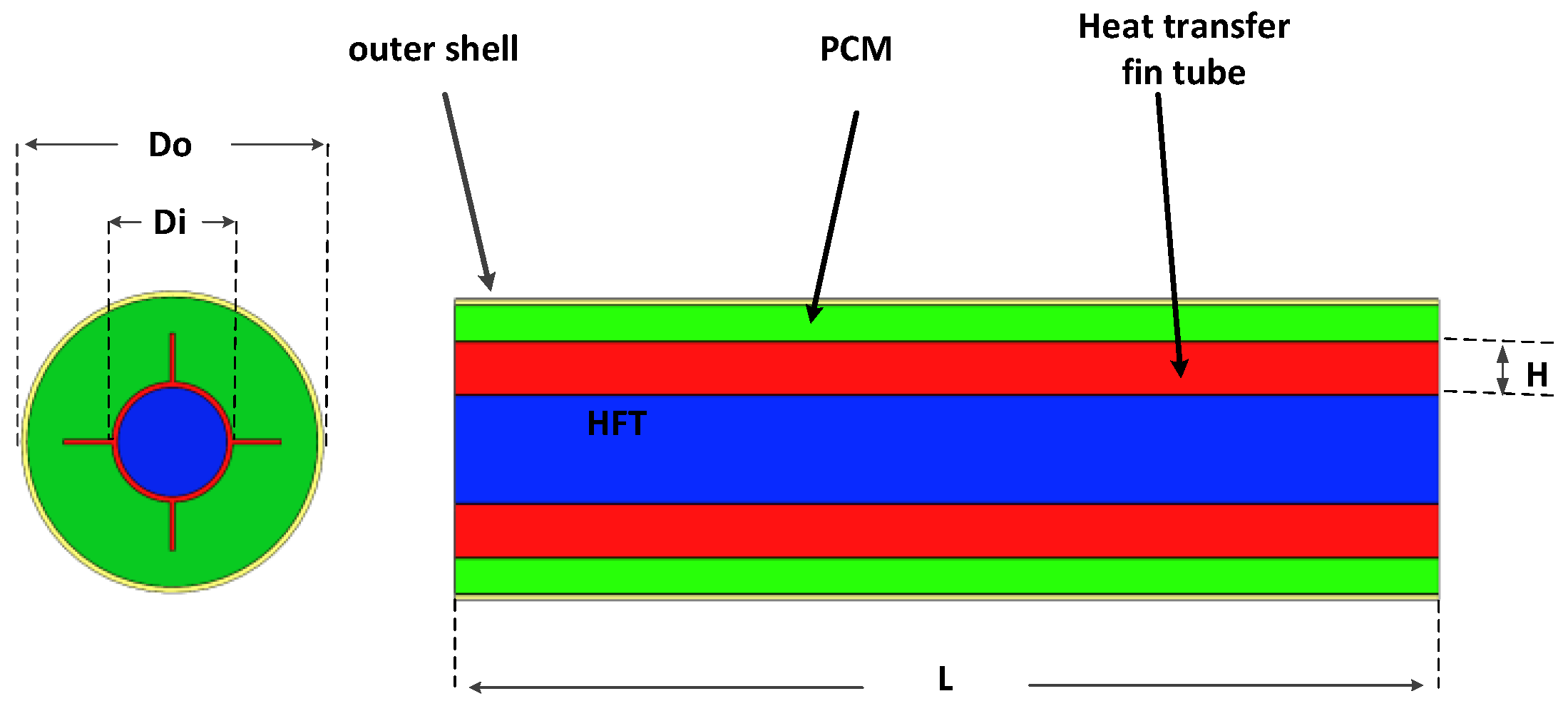

This study employs the PCM-EST to encapsulate the PCM within discrete energy storage units. A key advantage of this approach is that the PCM avoids direct contact with the battery pack. These energy storage units can be integrated with the battery liquid cooling system to provide both cooling and heating functions for the battery pack.The structure of the PCM-EST is illustrated in

Figure 2. Comprising four concentric layers from the exterior inward, the PCM-EST consists of: an outer shell, the PCM, a heat transfer fin tube, and heat transfer fluid (HTF). Fins are uniformly distributed around the heat transfer tube, and an insulation layer encases the exterior of the tube assembly.

2.2. PCM-EST Parameter Design

The amount of PCM in each energy storage tube is constrained by parameters such as its diameter and length. Therefore, an initial estimate of the required PCM mass is necessary. To highlight the thermal energy storage advantage of the PCM, we consider its mass at the point of peak heat absorption during the charging process [

39]. The relationship between PCM mass and volume is given by Equation (1), while Equation (2) expresses the heat absorbed by the PCM as a function of its mass:

——the volume of PCM,m3;

——the weight of PCM,kg;

——the specific heat of PCM,J/(kg∙K);

——the temperature of PCM at the beginning,K;

——the temperature of PCM at the end,K;

——the latent heat of phase change,KJ/kg。

Given the optimal operating temperature range for batteries (20-45 °C), the phase transition temperature of the PCM is selected as approximately 40 °C. The physical properties of the composite PCM utilized in Ma’s study [

40] are presented in

Table 1.

Based on the above formula and Du’s research [

41] on PCM applications in thermal management, the energy required to heat the PCM from 20 °C to complete melting is approximately 4933 kJ. This corresponds to a PCM mass of about 22.5 kg and a volume of approximately 0.0248 m

3. The effect of natural convection on the phase change process is also considered. Key structural parameters include the heat transfer tube diameter (

), insulation layer diameter (

), tube length (

), number of fins (n), and fin height (

). Factors influencing the heat storage and release rate of the tube include the fluid’s inlet temperature, flow rate, and the structure of the PCM-EST. While the fluid inlet temperature and flow rate are external factors controllable by the system, the PCM-EST structure must be designed with appropriate parameters prior to implementation in the thermal management system.

Cao’s study [

42] on double-layer PCM-ESTs analyzed the impact of parameters such as tube length and diameter on the heat exchange performance of a single tube. The research demonstrated that maintaining a constant overall PCM volume distributed across multiple tubes yields an efficient heat exchange energy storage device. Complementing this, Yuwen Z. [

26] investigated the contribution of fin number, thickness, and height to the enhanced heat storage performance of double-layer PCM-ESTs.Building upon this prior work, the present study adopts a similar approach. A commonly used tube diameter was selected. The inner and outer diameters of the double-layer PCM-EST are specified as follows: heat transfer tube diameter = 28×1 mm (outer diameter × wall thickness), insulation layer diameter = 67×1 mm. Based on these dimensions, fins were incorporated to examine the impact of fin number on the energy storage and release efficiency of the double-layer PCM-EST. This analysis led to the determination of the final structure for the single double-layer PCM-EST. The specific parameters used in the simulation are detailed in

Table 2.

2.3. PCM-EST Model

2.3.1. Heat Transfer Model of PCM-EST

The heat exchange calculation between the PCM-EST and the coolant follows a similar principle to that between the battery module and the coolant. During the heat absorption or release process, the thermal power transferred from the PCM-EST to the coolant is calculated using the following formula:

——the coolant mass flow rate, K;

——the specific heat capacity of coolant, J/(kg∙K);

——the inlet temperature, K;

——the export temperature, K;

During the transient heat exchange process between the PCM-EST and the coolant, the convective heat transfer rate within the PCM-EST does not equate to the heat absorbed by the PCM. This is because a portion of the heat is transferred to the heat transfer tube. The heat transferred to the tube is calculated as follows:

kg;

the

:

2.3.2. PCM-EST Heat Storage Model

During the melting or solidification process, PCMs undergo phase transitions, leading to the movement of the phase interface coupled with heat exchange. Furthermore, the nonlinearity of the phase change interface, the complexity of its geometry, and non-standard boundary conditions pose significant challenges to solving the phase change heat transfer problem.

Various numerical methods exist for solving phase change heat transfer problems, broadly categorized into two main types: interface tracking methods and fixed grid methods. Interface tracking methods encompass fixed-step methods, variable spatial step methods, variable time step methods, independent variable transformation methods, body-fitted coordinate methods, and isothermal surface movement methods [

43]. In contrast, fixed grid methods eliminate the need to explicitly track the two-phase interface position. Instead, they solve the liquid and solid regions as a single domain; common approaches include the equivalent specific heat method and the enthalpy method. Given its relative computational efficiency compared to other techniques and its widespread implementation in CFD software, the enthalpy model is employed for the PCM within the PCM-EST studied in this chapter.

The governing equations of the enthalpy model resemble those for single-phase flow, eliminating the need to satisfy explicit conditions at the solid-liquid interface during phase change. The enthalpy formulation inherently accounts for the solution within the mushy zone interface between the two distinct phases. For the PCM inside the tube, the flow during melting is assumed to be laminar, unsteady, and incompressible, with negligible viscous dissipation. The analysis accounts for the PCM’s thermophysical properties, including density, specific heat, thermal conductivity, and viscosity. The continuity, momentum, and energy equations governing the PCM model are given below [

44]:

Using the enthalpy model, the influence of phase transition on heat and mass transfer is solved through liquid phase fraction, and its energy equation is expressed as follows.

——the density of PCM, kg/m3;

——the enthalpy value of PCM, J;

——the thermal conductivity of PCM, W/(m∙K);

——the momentum source term;

——the fluid velocity, m/s;

——the dynamic viscosity, N∙S/m2;

——pressure, Pa;

The enthalpy value of PCM can be expressed as:

——the apparent heating value of PCM, J;

——the phase transition enthalpy occupied by PCM, J;

The sensible heat

of PCM is represented as:

——reference enthalpy, J;

——reference temperature, K;

The phase transition enthalpy

occupied by PCM is expressed as:

——latent heat of phase change, KJ/kg;

——liquid phase ratio, 0<

<1.

The momentum source term

can be expressed as:

In the equation,the coefficient is a constant in the mushy zone, with a value range from 104 to 107,and typical value 105.

During the phase change process, the PCM coexists in solid, liquid, and mushy phases, involving coupled heat transfer mechanisms including conduction, convection, and solid-liquid phase transition. To facilitate computation, the following simplifications are applied to the physical model based on the assumptions below [

45,

46]:

①The PCM is uniformly distributed and isotropic.

②The PCM adheres to the Boussinesq approximation, where density variations are considered only in the buoyancy term of the momentum equation.

③Supercooling and superheating phenomena are neglected during the phase change process.

These assumptions significantly simplify the heat transfer problem within the phase change model. The present study analyzes the phase change heat transfer characteristics in the double-layer PCM-EST and performs numerical simulations of the melting and solidification processes of the PCM within this structure.

2.4. Boundary Conditions and Parameter Settings

①Boundary Conditions for the Heat Storage and Release Process in the PCM-ESTBoundary conditions for both the inner and outer sides of the PCM-EST:

② Initial conditions

(1) The initial temperature of the phase change unit is 25 °C;

(2) The inlet temperature of the hot fluid flowing through the inner tube is in a constant temperature state of 60 °C;

(3) The insulation layer wrapped around the casing wall can be regarded as the insulation boundary, q=0;

(4) The fluid is a coolant (50% ethylene glycol aqueous solution) with a flow rate of 6 L/min (0.102 kg/s), and the parameters are shown in

Table 3.

2.5. CFD Numerical Simulation

To evaluate the influence of different structural parameters on thermal performance, CFD numerical simulations were performed using ANSYS Fluent. The simulations utilized a three-dimensional (3D) transient model incorporating the energy equation, the solidification/melting model, and the laminar flow model to simulate the PCM phase change.

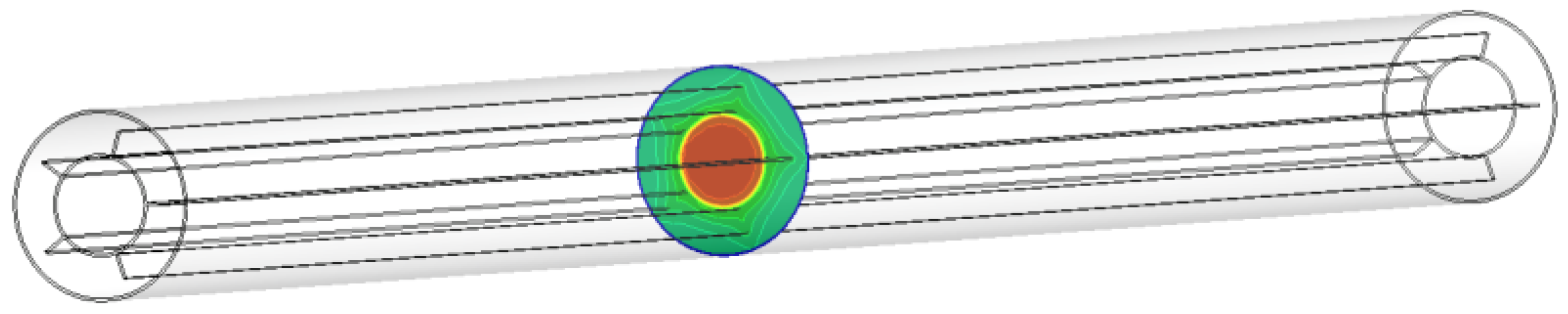

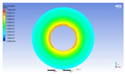

Figure 3 illustrates the melting state of the PCM-EST at a particular cross-section.

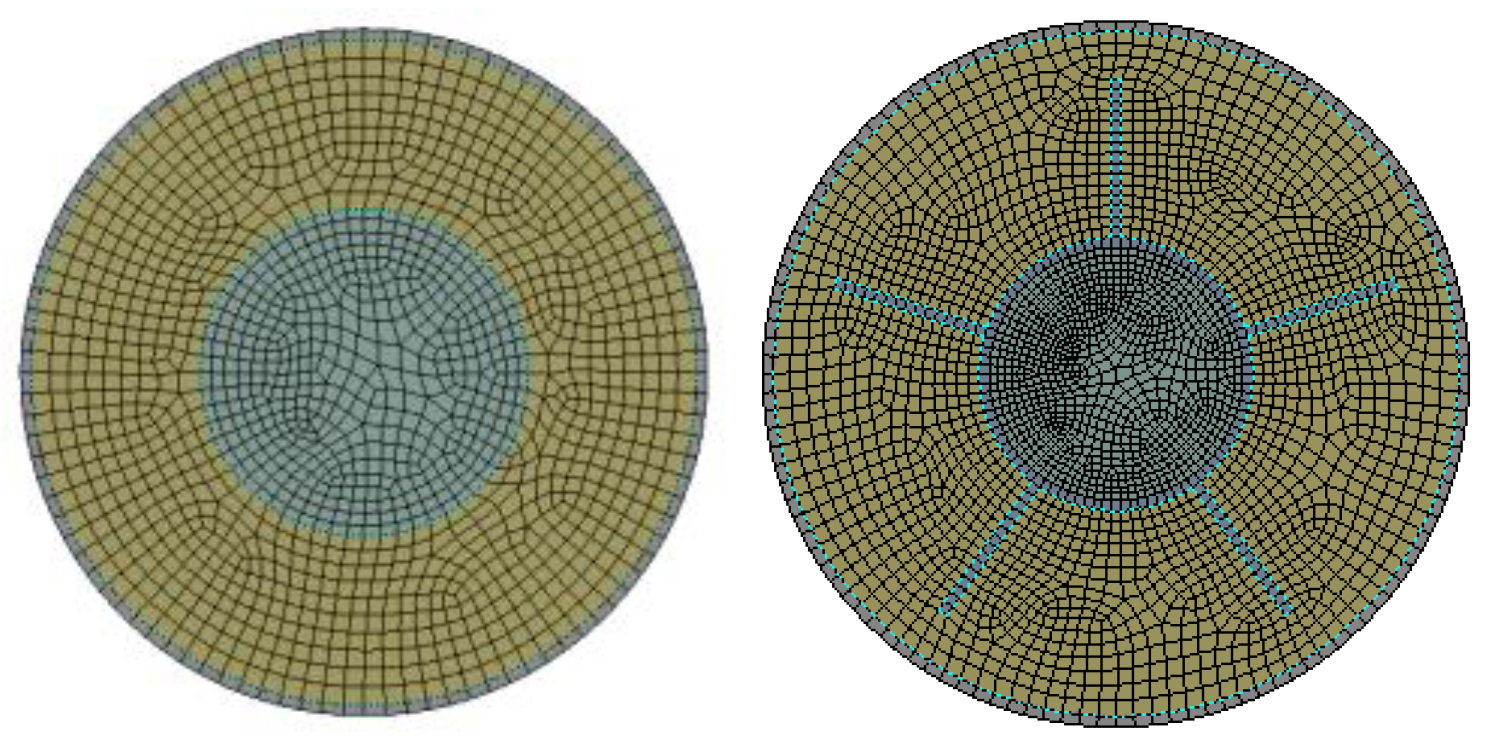

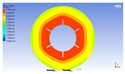

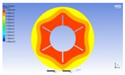

The computational domain was discretized using an appropriate meshing technique, with local mesh refinement implemented near the fin regions.

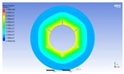

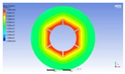

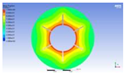

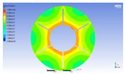

Figure 4 provides a schematic of the mesh topology for the two distinct structures.Mesh independence was verified through a systematic study. Using the baseline energy storage tube configuration (n=0, H=0) as a representative case, the liquid phase fraction results were compared across progressively refined mesh densities. Mesh independence is confirmed when the simulation results stabilize, exhibiting minimal variation with further mesh refinement. Conversely, if the results persistently increase or decrease without convergence, the mesh is deemed insufficiently refined, necessitating additional densification.

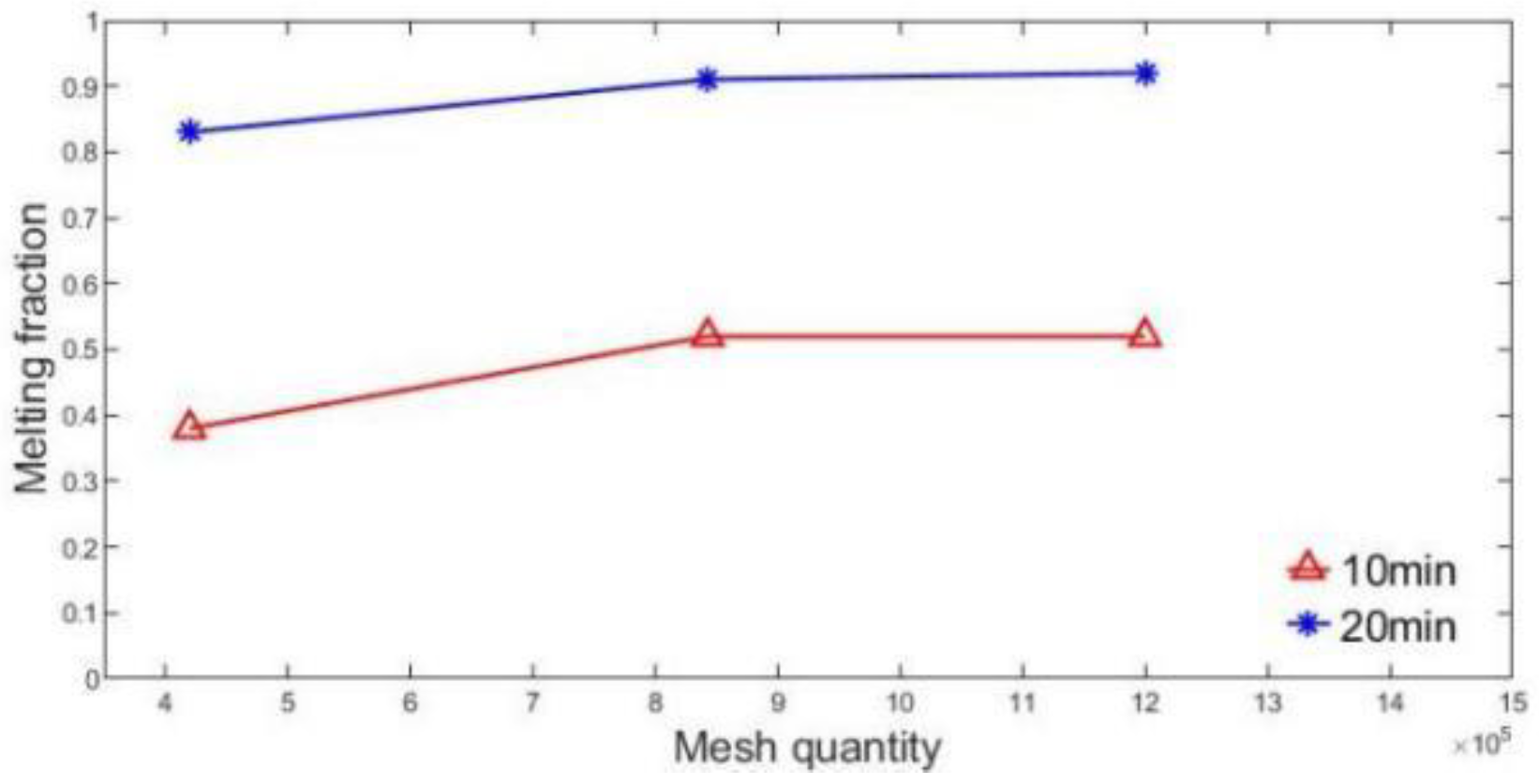

The results are presented in

Figure 5. The x-axis represents the number of mesh elements, and the y-axis represents the liquid mass fraction of the PCM within the energy storage tube. The figure displays the liquid mass fractions at 10 minutes (red) and 20 minutes (blue) for three distinct mesh densities: 4.2×10

5, 8.5×10

5, and 12.5×10

5 elements. Comparing the simulation results across the three mesh densities reveals that the coarsest mesh (4.2×10

5 elements) yields less accurate results. In contrast, the results obtained with the finest mesh (12.5×10

5 elements) are nearly identical to those using the medium mesh (8.5×10

5 elements). However, the element count of the finest mesh is approximately 1.5 times higher than that of the medium mesh, significantly increasing computational cost. Given that excessively high mesh counts impair computational efficiency without substantially improving accuracy beyond the medium mesh, the medium mesh density (8.5×10

5 elements) was selected. This choice ensures a balance between simulation accuracy and computational efficiency. Therefore, the optimal mesh size for the phase change unit in this study is approximately between 8.5×10

5 and 9.5×10

5 elements.

The simulations employed a 3D segregated-transient solver, incorporating the energy equation, the solidification/melting model, and the laminar flow model. Pressure-velocity coupling was handled using the SIMPLEC algorithm. Discretization of the momentum and energy equations utilized a second-order upwind scheme [

46].The residual convergence criteria for all equations retained their default solver settings. Under-relaxation factors were set as follows: pressure (0.3), density (1), momentum (0.7), liquid fraction (0.9), and energy (1). The time step was fixed at 0.02 s, with a maximum iteration limit of 20 per time step. Convergence was achieved when the scaled residuals reached 10

−6 for energy and 10

−3 for velocity.

6. Conclusion

This study optimizes PCM-ESTs for NEV BTMS, targeting enhanced heat transfer efficiency and lightweight design. Through three-dimensional CFD simulations, we systematically analyzed how fin count, fin height ratio, and tube length influence composite PCM behavior during phase transitions. Results demonstrate that fin parameters significantly govern PCM-EST thermal performance and structural mass, confirming geometric optimization as an effective approach for improving system-level performance.

To balance thermal efficiency and mass reduction, we implemented a hybrid MOPSO-Kriging optimization framework. Parameter sampling, numerical modeling, and surrogate-based optimization yielded an optimal design showing 8.7% improvement in performance evaluation criterion (PEC) with 0.732 kg mass reduction. This validates the method’s dual-capability for thermal enhancement and lightweight achievement. Compared to single-variable approaches, multivariate cooperative optimization simultaneously increases heat transfer efficiency while mitigating parasitic mass penalties.

Our methodology provides an innovative solution for next-generation EV thermal management systems. By synergistically optimizing thermal performance and compactness, we enable reduced energy consumption and extended battery cycle life – enhancing vehicle sustainability. Future work should validate designs experimentally and explore advanced optimization strategies (e.g., topology optimization, AI-driven design) to further advance PCM-EST performance for continuously evolving EV thermal management requirements.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of battery thermal management system using PCM-EST.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of battery thermal management system using PCM-EST.

Figure 2.

Structure diagram of PCM-EST.

Figure 2.

Structure diagram of PCM-EST.

Figure 3.

PCM melting state.

Figure 3.

PCM melting state.

Figure 4.

Grid division diagram.

Figure 4.

Grid division diagram.

Figure 5.

Grid verification.

Figure 5.

Grid verification.

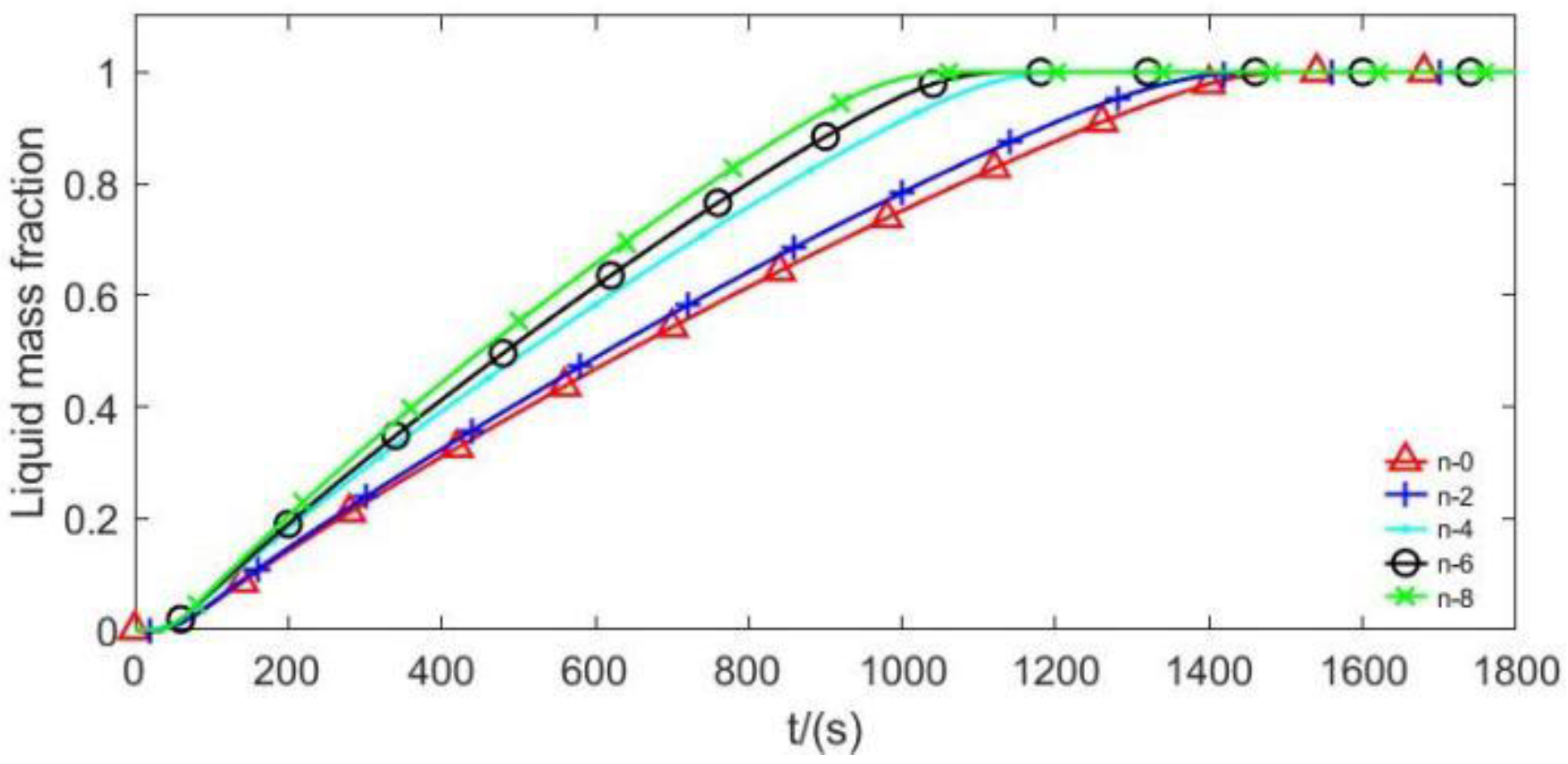

Figure 6.

Variation of melting fraction with time for different number of fins.

Figure 6.

Variation of melting fraction with time for different number of fins.

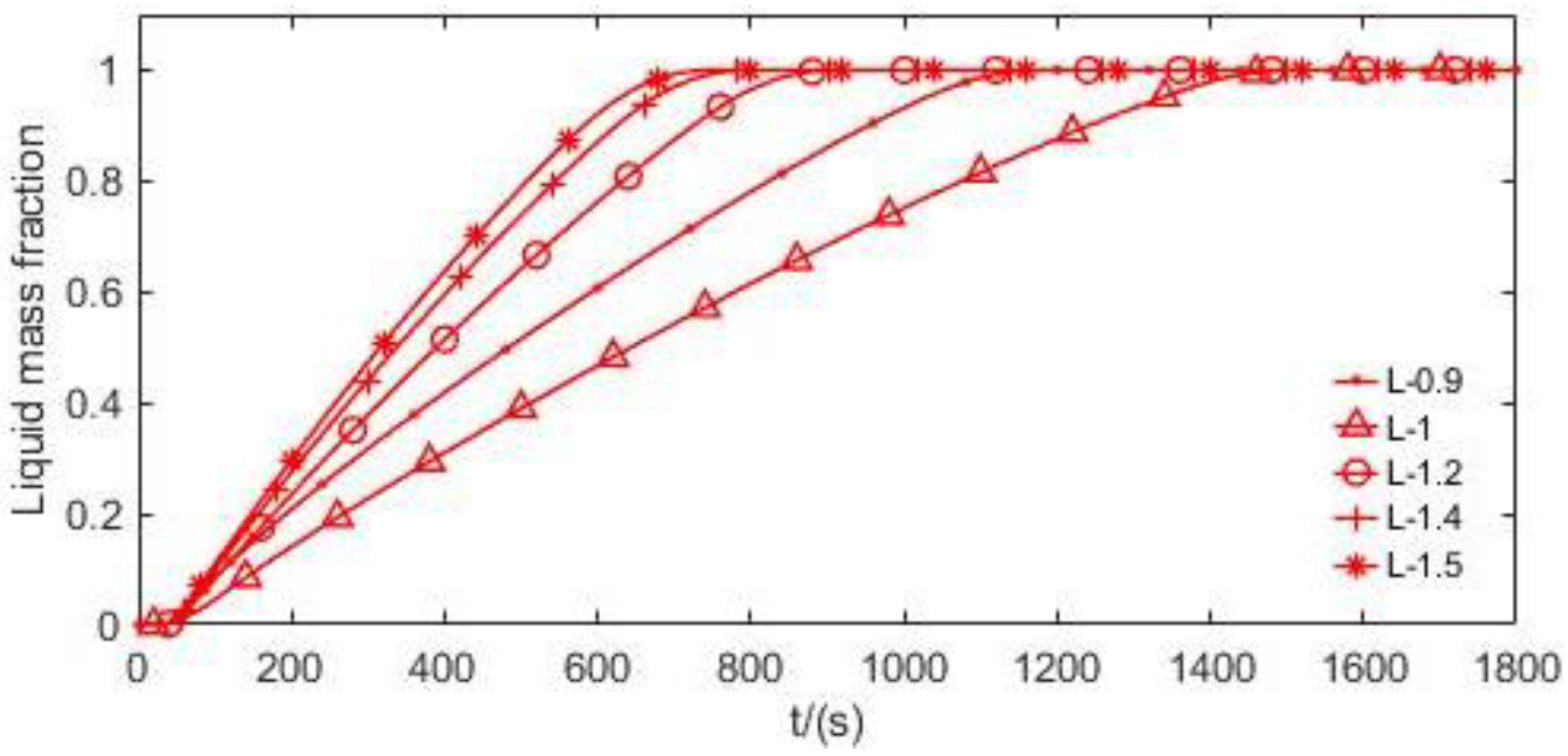

Figure 7.

Variation of melt fraction with time at different fin heights.

Figure 7.

Variation of melt fraction with time at different fin heights.

Figure 8.

PCM melting fraction versus time for different lengths.

Figure 8.

PCM melting fraction versus time for different lengths.

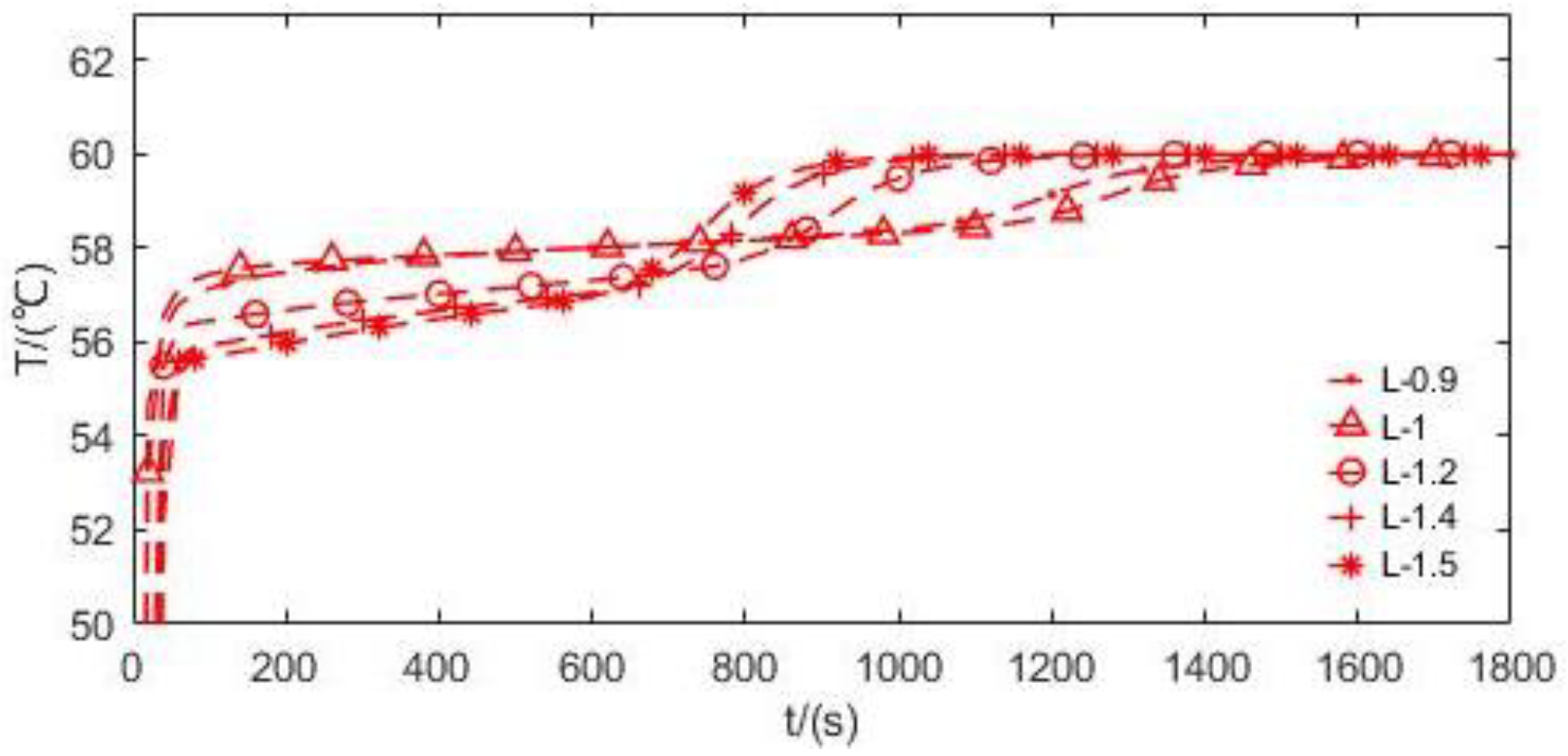

Figure 9.

Fluid outlet temperature-time at different lengths.

Figure 9.

Fluid outlet temperature-time at different lengths.

Figure 10.

Optimization process.

Figure 10.

Optimization process.

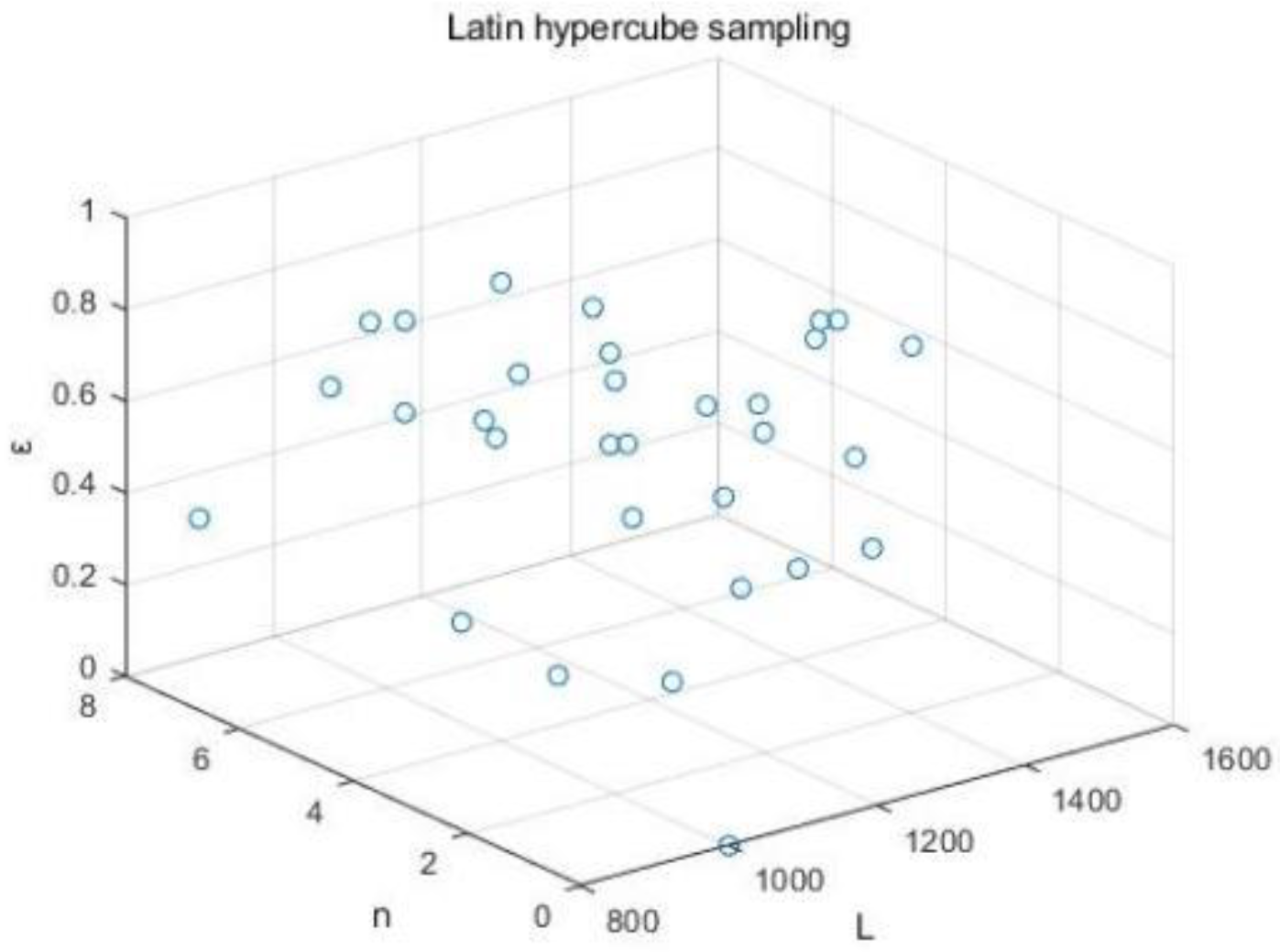

Figure 11.

Latin hypercube sampling.

Figure 11.

Latin hypercube sampling.

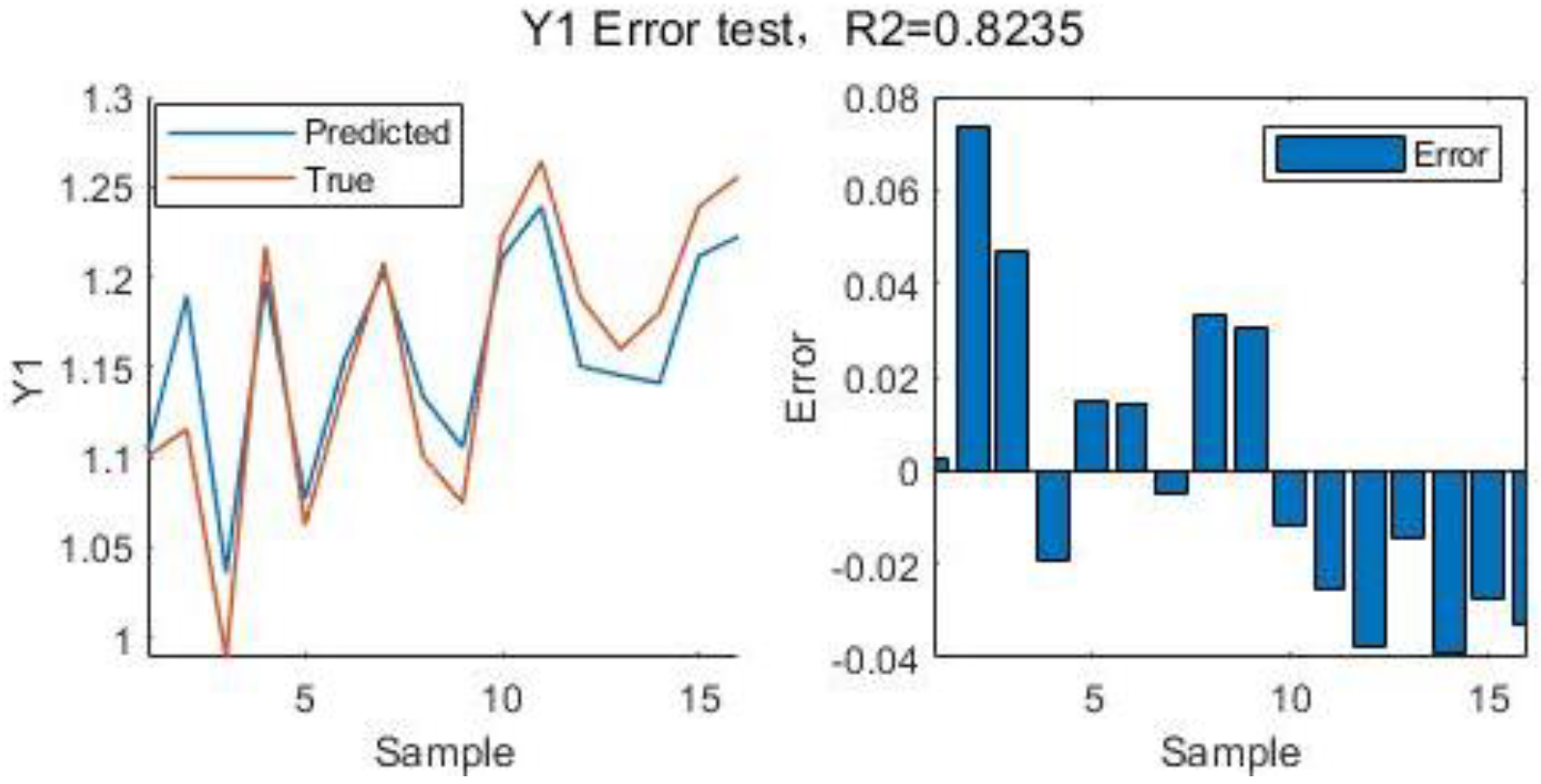

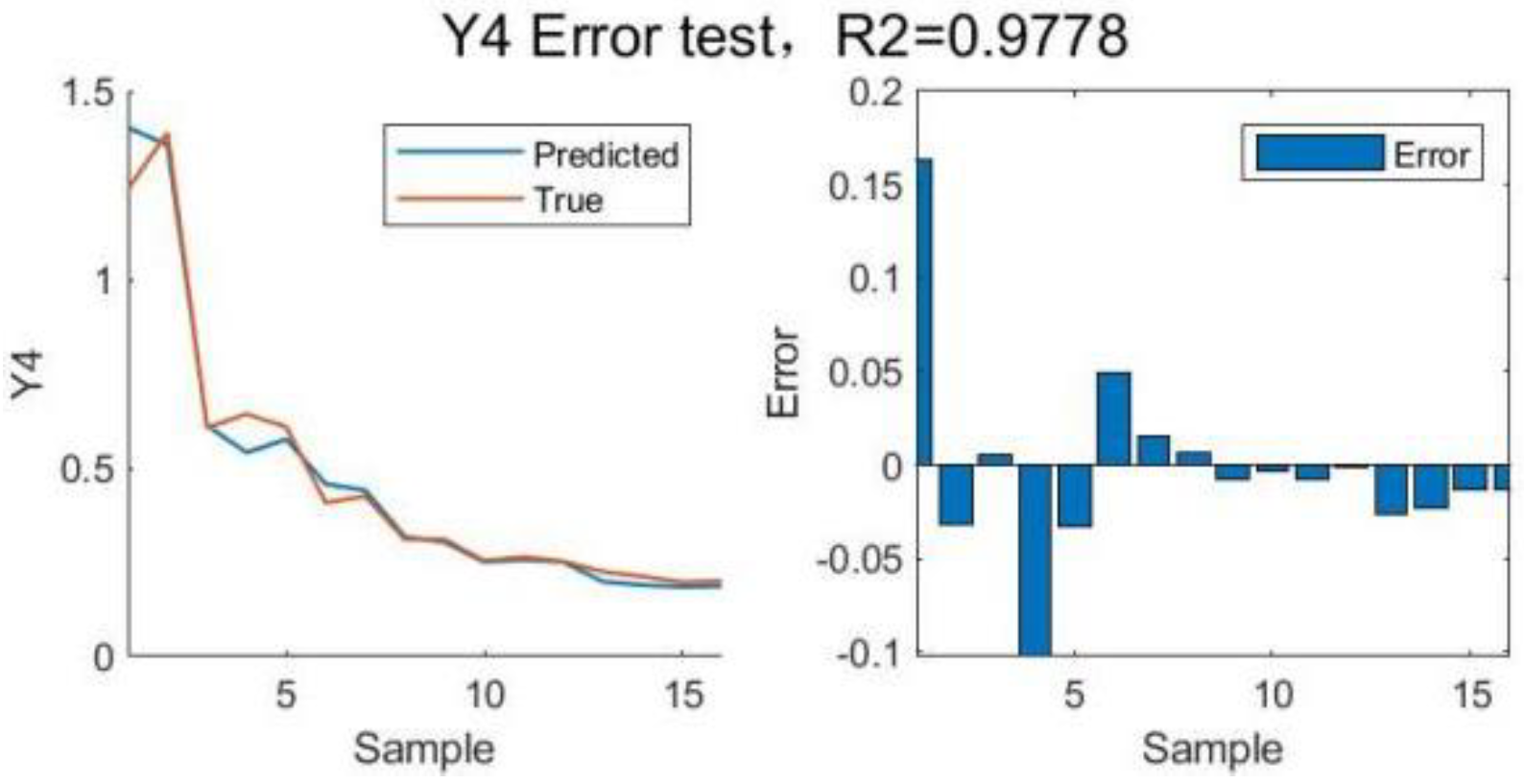

Figure 12.

Error test for

Figure 12.

Error test for

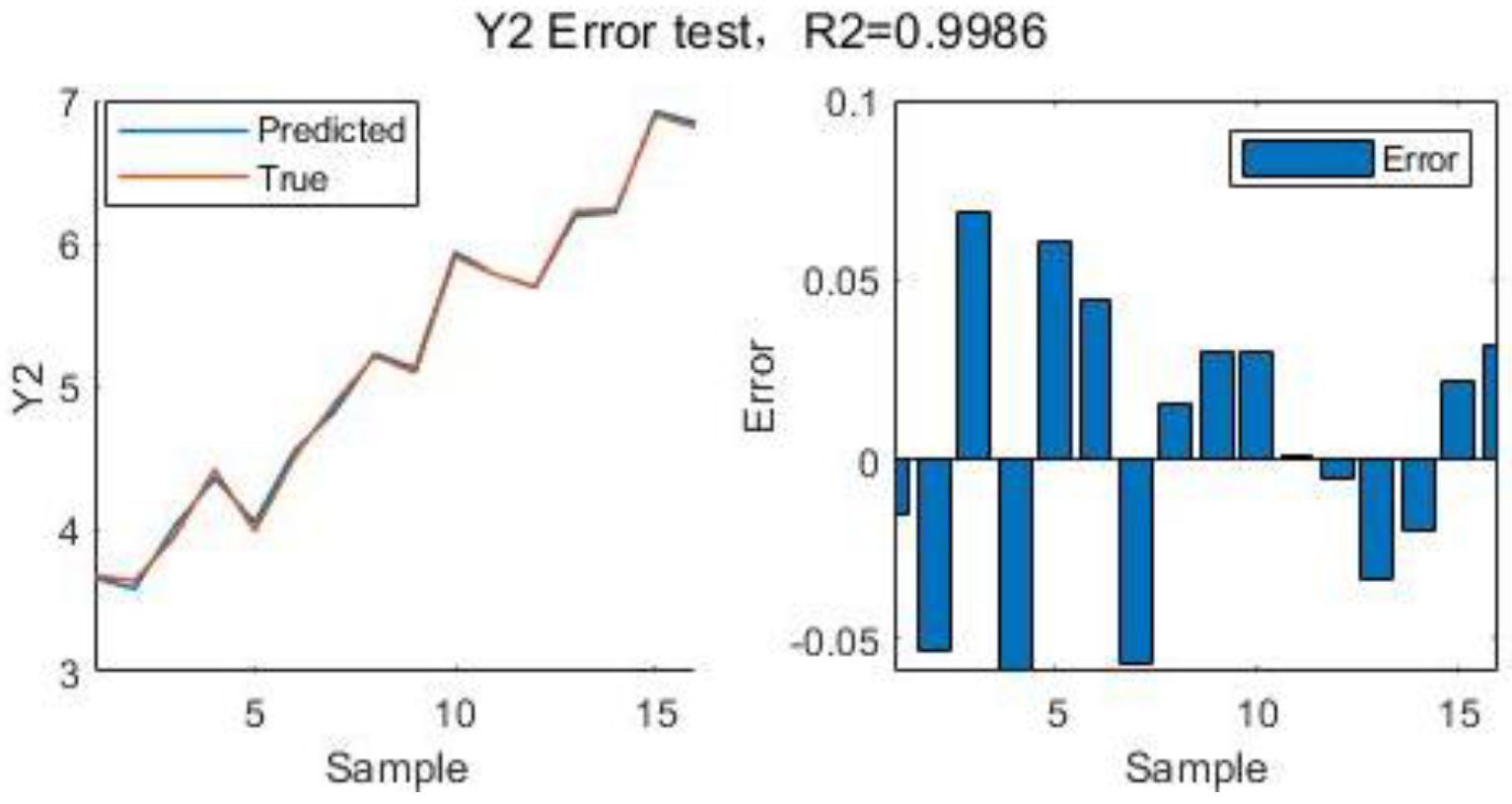

Figure 13.

Error test for

Figure 13.

Error test for

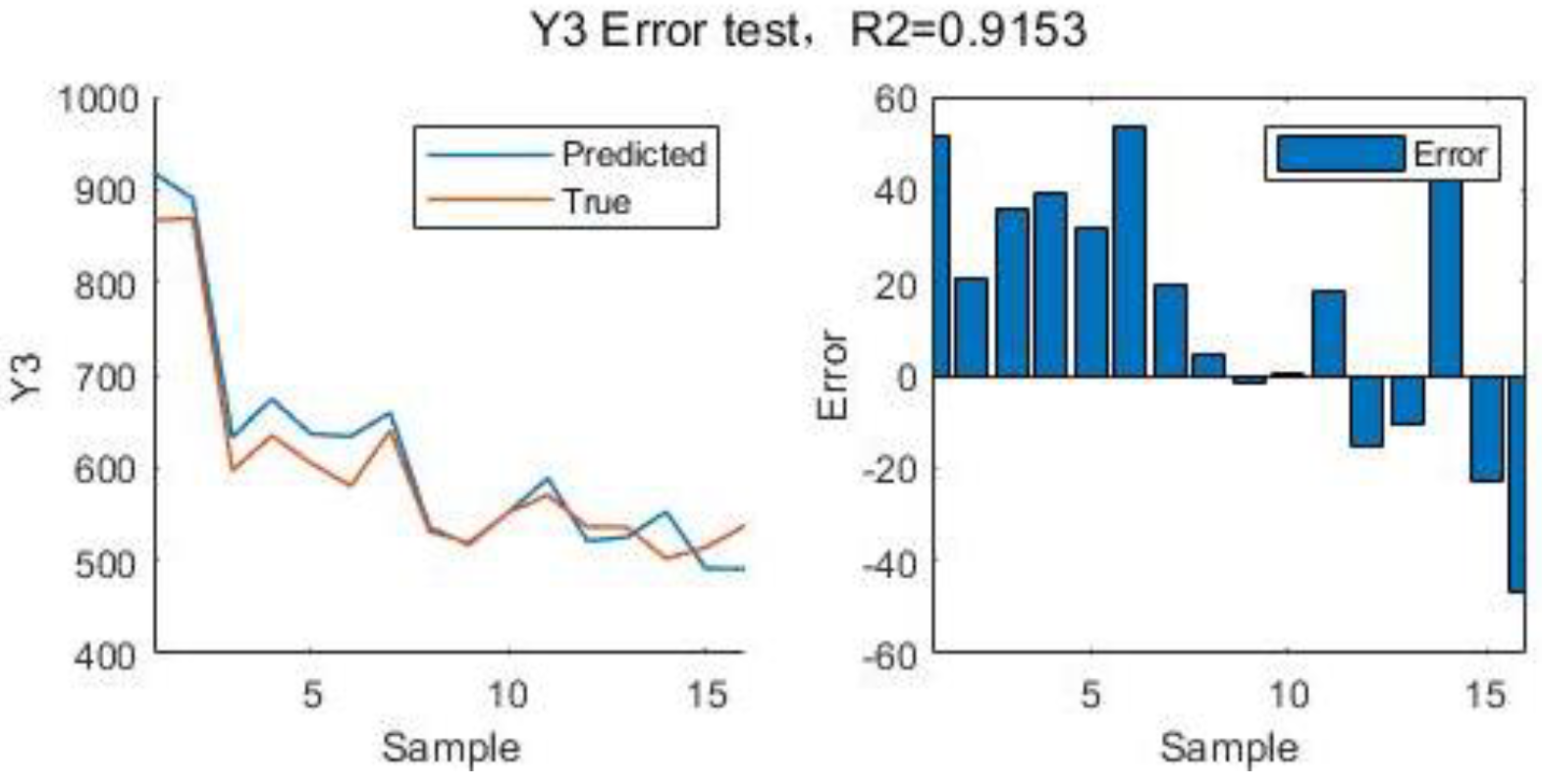

Figure 14.

Error test for

Figure 14.

Error test for

Figure 15.

Error test for

Figure 15.

Error test for

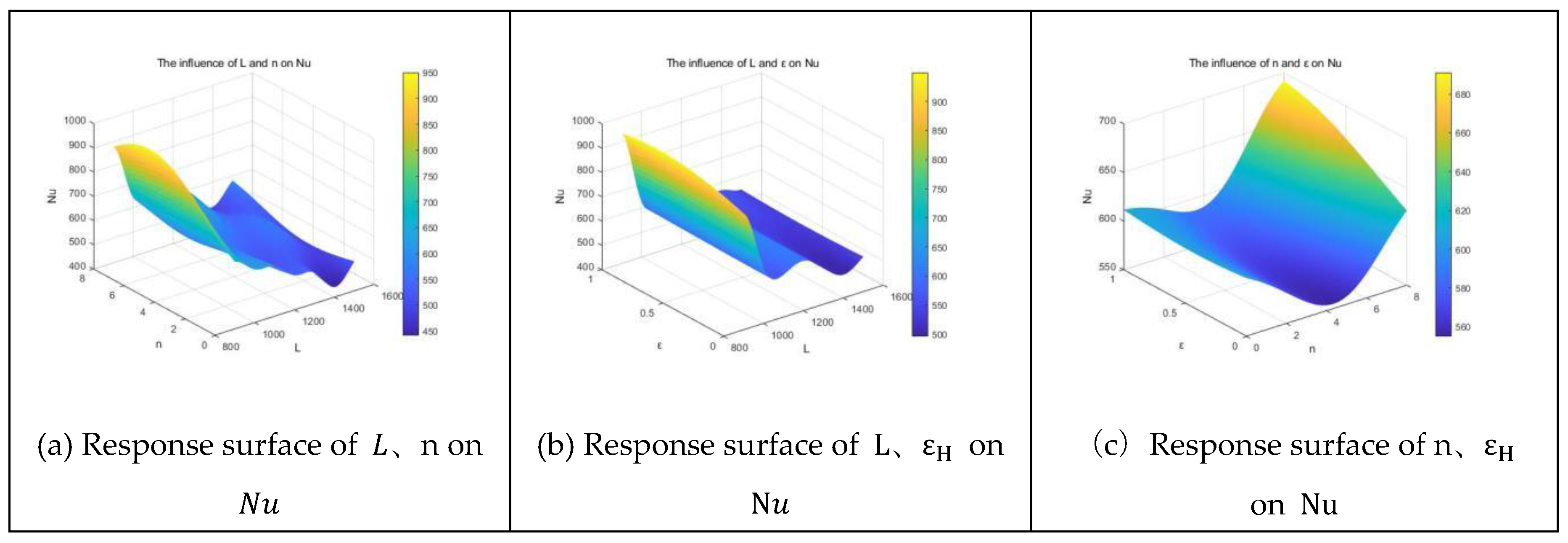

Figure 16.

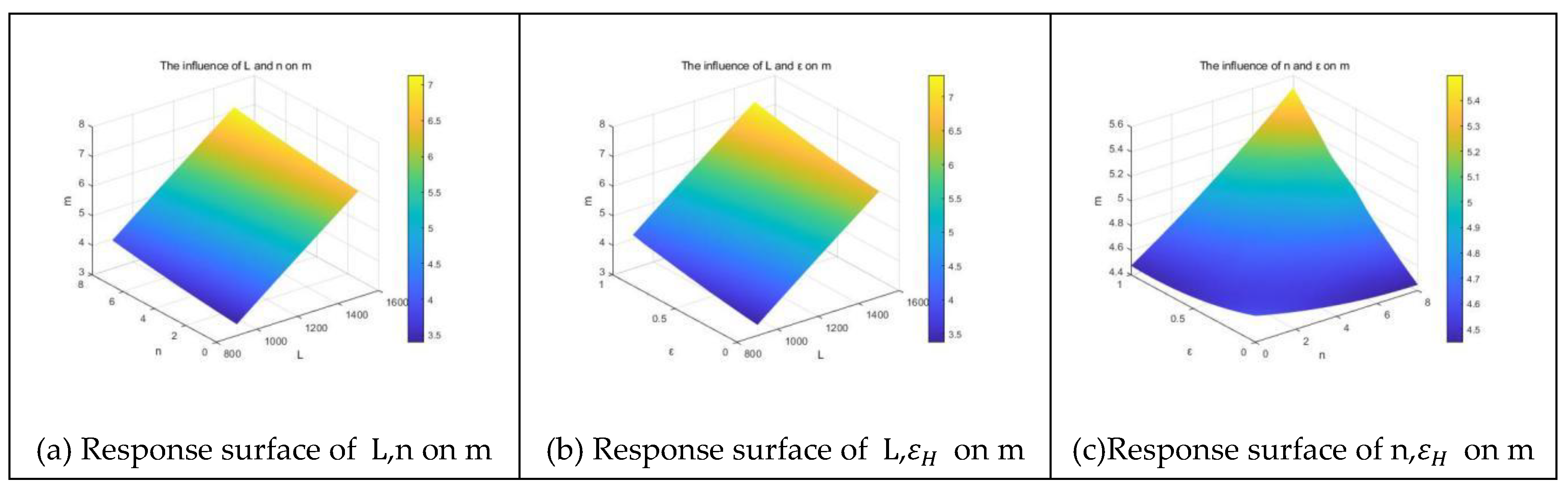

Response surface analysis of the three design variables on

Figure 16.

Response surface analysis of the three design variables on

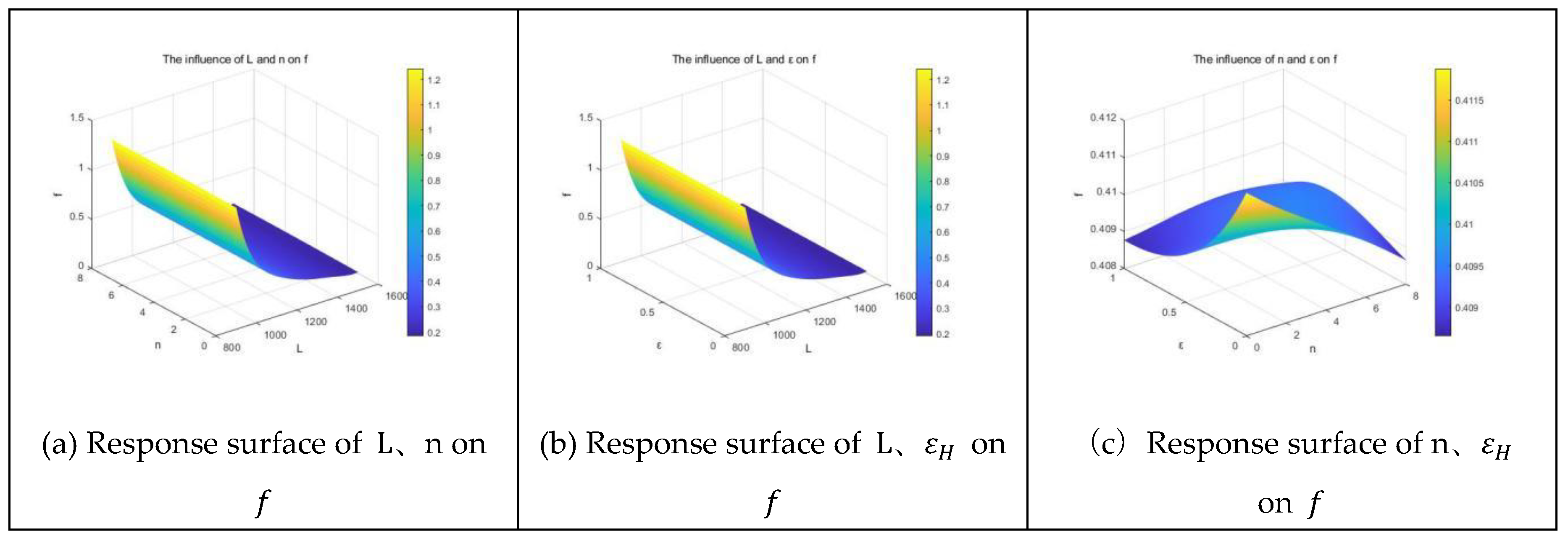

Figure 17.

Response surface analysis of the three design variables on

Figure 17.

Response surface analysis of the three design variables on

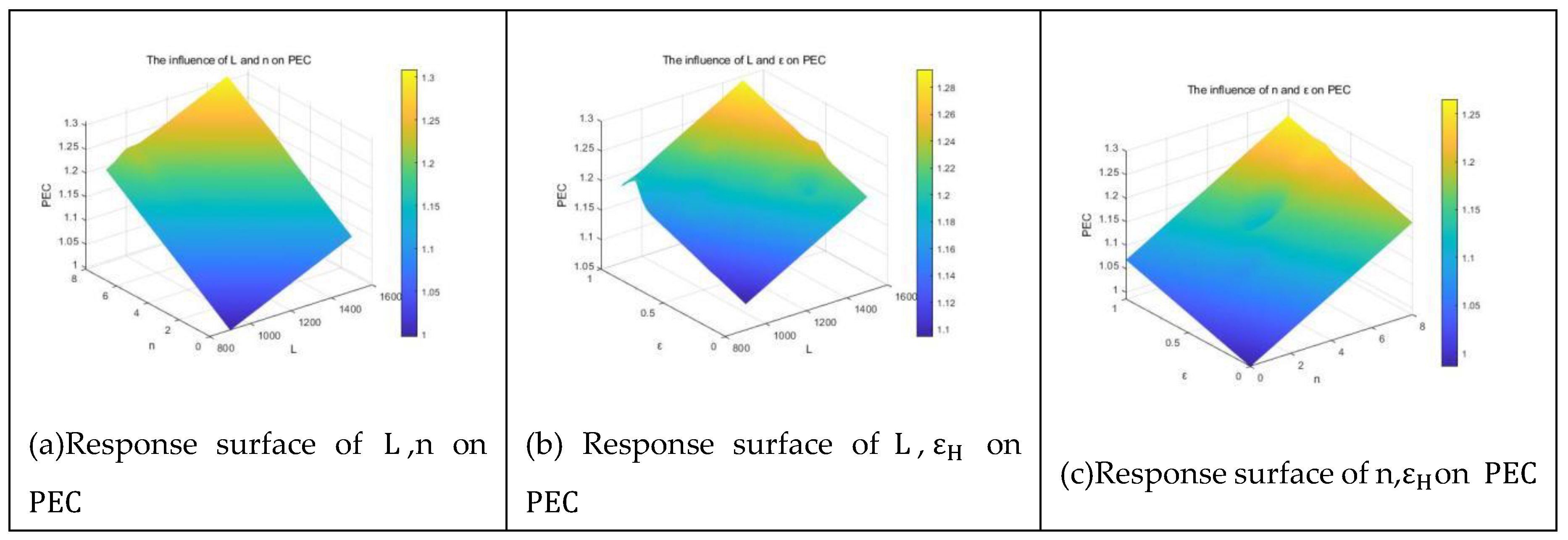

Figure 18.

Response surface analysis of the three design variables on

Figure 18.

Response surface analysis of the three design variables on

Figure 19.

Response surface analysis of the three design variables on m.

Figure 19.

Response surface analysis of the three design variables on m.

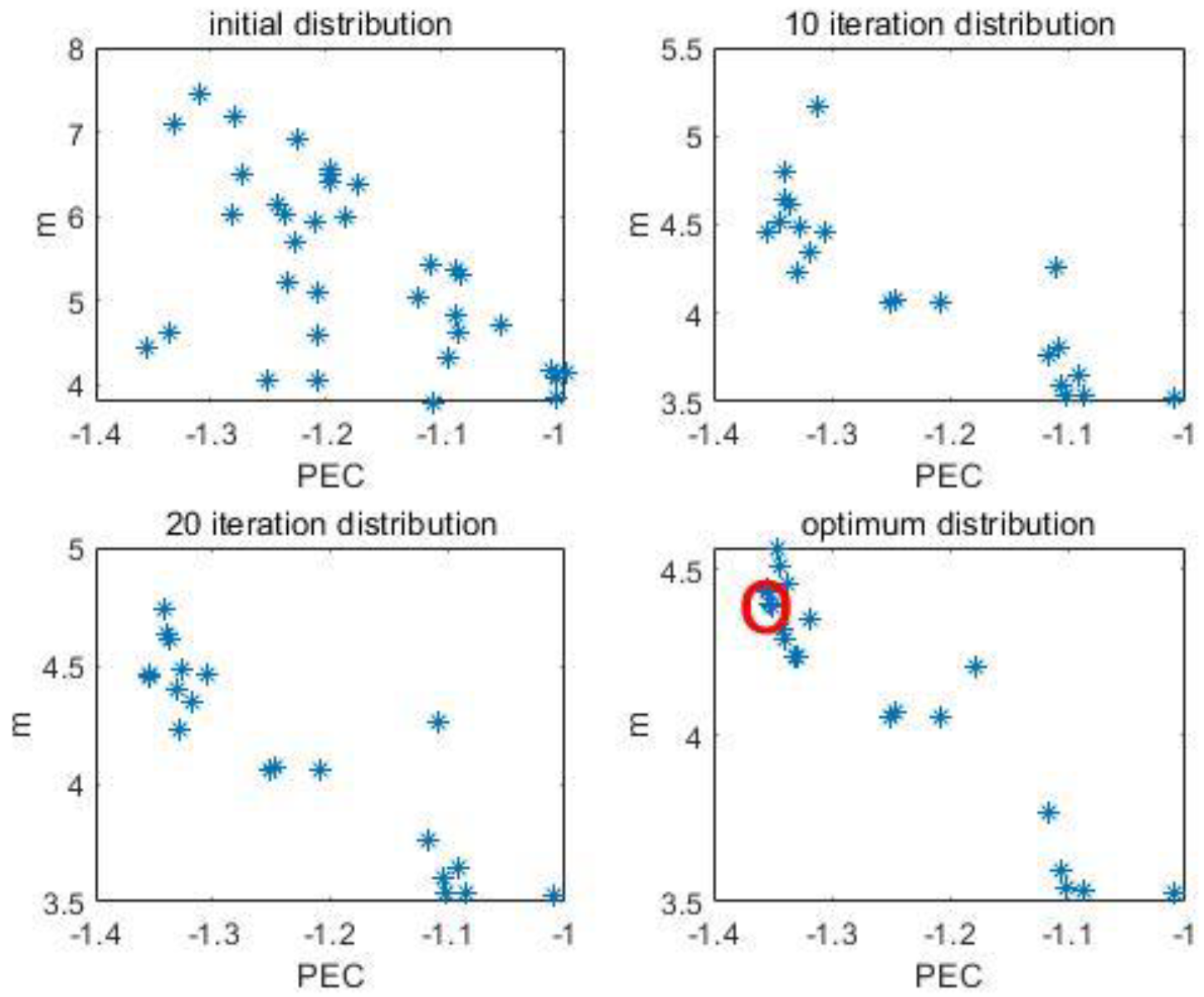

Figure 20.

Particle swarm iterative solution process.

Figure 20.

Particle swarm iterative solution process.

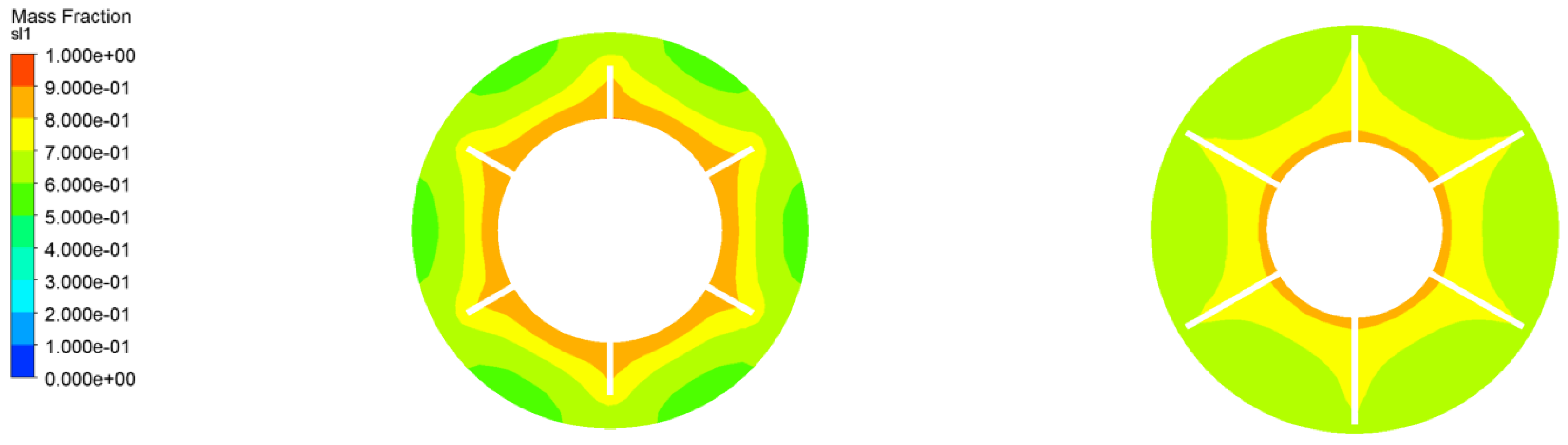

Figure 21.

PCM melting mass fraction at PC-EST exit at 600s time.

Figure 21.

PCM melting mass fraction at PC-EST exit at 600s time.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of composite phase change materials.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of composite phase change materials.

| Composition |

Phase transition temperature(°C) |

Latent heat(KJ/kg) |

Thermal conductivity(W∙m-1∙K-1) |

Specific heat capacity

(KJ∙kg-1∙K-1) |

Density(kg∙m-3) |

| Expanded graphite/paraffin wax |

38.6-45.9 |

164 |

10.5 |

2.15 |

910 |

Table 2.

Geometric parameters of double-layer phase change energy storage tube.

Table 2.

Geometric parameters of double-layer phase change energy storage tube.

| Geometric parameters |

Symbol |

Numerical value |

| Heat transfer tube |

|

67 mm |

| Insulation layer diameter |

|

28 mm |

| Tube length |

|

1000 mm |

| Number of fins |

n |

0 mm |

| PCM volume |

Vpcm1 |

2.5 L |

Table 3.

Coolant parameter.

Table 3.

Coolant parameter.

Density

[kg/m3] |

Freezing point

[°C] |

Boiling point

[°C] |

Kinematic viscosity

[mm2/s] |

Dynamic viscosity

[N·s/m2] |

Specific heat capacity

[J/kg·K] |

Thermal conductivity

[W/m·K] |

| 1073.35 |

-37.9 |

107.8 |

3.67 |

0.00394 |

3281 |

0.38 |

Table 4.

Variation of the melting interface with time for different number of fins.

Table 5.

Variation of the melting interface with time for different fin heights.

Table 6.

Structure parameters corresponding to different pipe lengths.

Table 6.

Structure parameters corresponding to different pipe lengths.

| Parameter |

Structure parameters |

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

|

(mm) |

67 |

67 |

67 |

67 |

67 |

|

(mm) |

18 |

28 |

34 |

39 |

41 |

|

(mm) |

900 |

1000 |

1200 |

1400 |

1500 |

| n(mm) |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

(mm) |

16 |

12 |

8 |

6 |

5 |

Table 7.

Structural parameter range.

Table 7.

Structural parameter range.

| Design variables |

Lower limit value |

Upper limit value |

| Length () |

900 |

1500 |

| Number of fins(n) |

0 |

8 |

| Proportion of fin height() |

0 |

1 |

Table 8.

Goodness of fit under different order regression models.

Table 8.

Goodness of fit under different order regression models.

| Goodness of fit R2

|

regpoly0 |

regpoly1 |

regpoly2 |

| R2() |

0.0072 |

0.8235 |

0 |

| R2() |

0.9912 |

0.9800 |

0.9986 |

| R2() |

0.9153 |

0.6472 |

0 |

| R2) |

0.9778 |

0.9189 |

0.1494 |

Table 9.

Comparison of optimization results of double-layer phase change energy storage tube.

Table 9.

Comparison of optimization results of double-layer phase change energy storage tube.

| Parameters |

|

|

|

m |

| Particle Swarm Results |

956.5919 |

0.8684 |

1.3546 |

4.3882 |

| CFD results |

932.60439 |

0.941006 |

1.3345 |

4.416 |

| Initial design parameters |

714.38 |

0.49 |

1.2702 |

5.148 |