1. Introduction

The battery is one of the core components of a pure electric vehicle. At present, the power batteries of electric vehicles mainly include supercapacitors, nickel-based batteries, lead-acid batteries, lithium-ion batteries, zinc-air batteries, etc. Among them, lithium-ion batteries have become the preferred solution for electric vehicle manufacturers due to their high energy density, light weight, and long service life. However, the performance, lifespan and safety of lithium-ion batteries are very sensitive to temperature. An efficient battery thermal management system should ensure that the battery operates within the optimal working temperature range (15-35 °C) [

1,

2]and make the temperature distribution on the battery surface uniform. If the temperature of lithium-ion batteries exceeds 50°C, the charging efficiency and service life will be greatly reduced [

3]. In the temperature range of 70-100°C, lithium-ion batteries may triggering thermal runaway and other safety accidents [

4].

At present, the most commonly used thermal management methods in lithium-ion batteries include air cooling, liquid cooling, phase change materials (PCMs) and heat pipe cooling technologies [

5]. The air cooling technique pumps ambient air to purge the battery module to accelerate the heat dissipation. It has the characteristics of simple structure, easy implementation and relatively low cost, but the cooling efficiency is low. Akinlabi and Solyali [

6] reviewed the air-cooling battery thermal management systems, and concluded that it is difficult to control the temperature of high-energy-density lithium batteries by air-cooling battery thermal management system (BTMS). The PCMs cooling system is a passive cooling method, and the PCMs used usually has a large latent heat of fusion and an ideal melting point, and can store a large amount of heat generated during the charging and discharging process of the battery. However, the PCMs usually have low thermal conductivity and lead to poor thermal propagation. The PCMs should be modified[

7,

8,

9] or added with other additives [

10,

11], and used in conjunction with other cooling methods [

12,

13,

14]. Similar to the phase change material cooling system, heat pipe cooling usually needs to be used in combination with other cooling methods [

15,

16,

17], and the heat transfer performance of the heat pipe will be reduced when the vehicle is affected by shock and vibration.

The liquid cooling system has gradually become the hotspot of BTMS. According to the contact type between the coolant and the batteries, it is usually divided into indirect liquid cooling (ICLC) and direct liquid cooling (DCLC, also called as immersion cooling) [

18]. Indirect contact liquid cooling usually uses water or a mixture of water and ethylene glycol as the coolant. The coolant flows in channels of pipes, cold plates or water jackets, and removes the heat generated by the battery. Due to the electrical conductivity of the coolant, the indirect cooling system needs to be well sealed to prevent liquid leakage from causing a short circuit. At the same time, the thermal contact resistance between the metal separator and the battery needs to be considered. Although the indirect cooling system has good heat dissipation capacity, the structure of the system is relatively complex, the whole system is very bulky, expensive, and the maintenance cost increases. In the early days of direct contact liquid cooling, deionized water, silicone oil, mineral oil, and refrigerants were commonly used as coolants[

19]. Although liquid has a high thermal conductivity compared with air, which can effectively reduce the maximum temperature of the batteries, the direct contact liquid cooling system still greatly relies on the liquid cooling arrangement to enhance the convective heat transfer coefficient, thereby improving the overall temperature uniformity of the battery pack.

In recent years, the immersion cooling system for power battery thermal management has become a new research hotspot. The battery is immersed in a dielectric coolant. Unlike the indirect liquid cooling system, the immersion cooling system has no contact thermal resistance, smaller volume, higher cooling efficiency, and more uniform temperature distribution. To prevent short circuits and electrochemical corrosion between the battery and the working fluid, the coolant should be selected to have insulation properties, non-toxicity, chemical inertness, high thermal conductivity, and flame-retardant characteristics [

20,

21]. Such fluids typically offer superior thermal performance for BTMS. Nelson and colleagues [

22] developed a battery module comprising 12 serially connected cells, incorporating 1 mm wide flow channels filled with silicone oil between adjacent cells. Their experiments demonstrated that silicone oil, serving as a thermal medium, offers significantly better heat dissipation performance than air cooling. Karimi et al. [

23] carried out a comparative assessment of water, silicone oil, and air as cooling media, showing that liquid-based cooling can effectively keep battery temperatures within an acceptable operational range, although minor internal temperature variations may still occur. Hirano et al. [

24] explored the use of 3M’s Novec7000 for immersion cooling applications. The results indicated that when the battery undergoes 20C high-rate charge and discharge cycles, submerging it in Novec7000 successfully maintains maximum battery temperature

Tmax at a stable 35°C. Tan et al. [

25] utilized HFE-6120 as the working fluid, and conducted CFD simulations to analyze its key operational parameters in DCLC system. Satyanarayana et al. [

26] compared the immersion cooling effectiveness of mineral oil and terminal oil under varying discharge rates. Their findings revealed that low-viscosity mineral oil is more efficient in managing

Tmax, achieving a reduction of up to 49.16% in

Tmax compared to natural air convection cooling. Patil et al. [

27] investigated the direct cooling performance of Li-ion batteries using dielectric fluid immersion cooling combined with tab cooling. By inserting baffles, the disturbance and residence time of the coolant are increased. The results demonstrated significantly improved thermal management, with up to a 46.8% reduction in maximum tab temperature and better overall pack performance compared to conventional cooling methods. Wu et al. [

28] compared single-phase and two-phase liquid cooling systems for large lithium-ion batteries, showing that the single-phase system with deionized water and copper foam provides superior thermal performance, achieving lower temperatures and better uniformity during high-rate discharge. Choi et al. [

29] proposed a hybrid immersion-cooling structure with one pass partition and graphite fins. The performance of the structure was investigated with variations in key design parameters such as flow direction, battery spacing, pass partitions, and thermal conductive materials. The results show that, compared to conventional structures, this hybrid immersion structure achieves a maximum temperature reduction of 6.7 °C and a temperature difference reduction of 3.0 K under nearly the same weight condition. Zhao et al. [

30] developed a hybrid battery thermal management system combining direct liquid cooling with forced air cooling. A jacket was designed outside the battery, with liquid coolant filled between the battery case and the jacket to achieve direct cooling, while air cooling was applied externally. The effects of gap spacing between the battery and liquid-cooling jacket, number of cooling pipelines, liquid flow rate, and fan position on cooling performance were analyzed through numerical simulation. Febriyanto et al. [

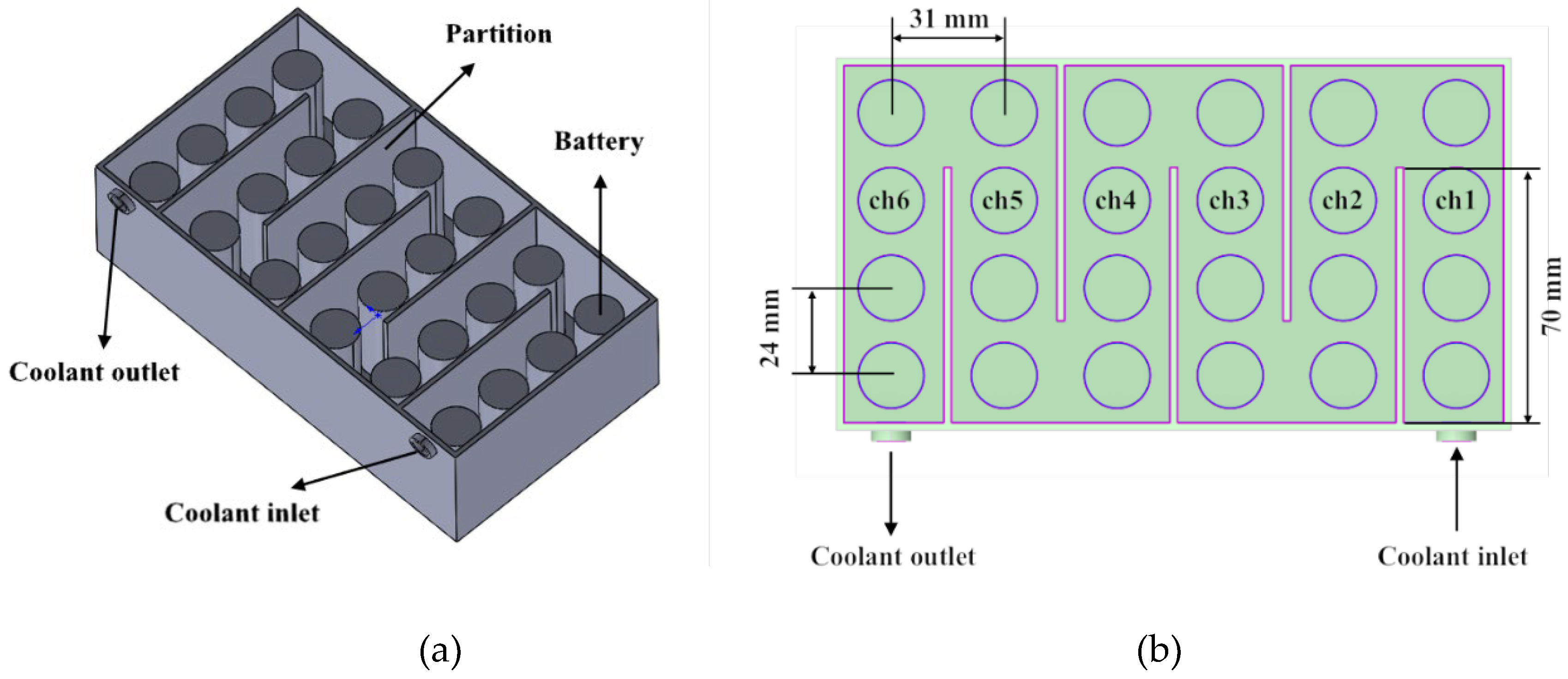

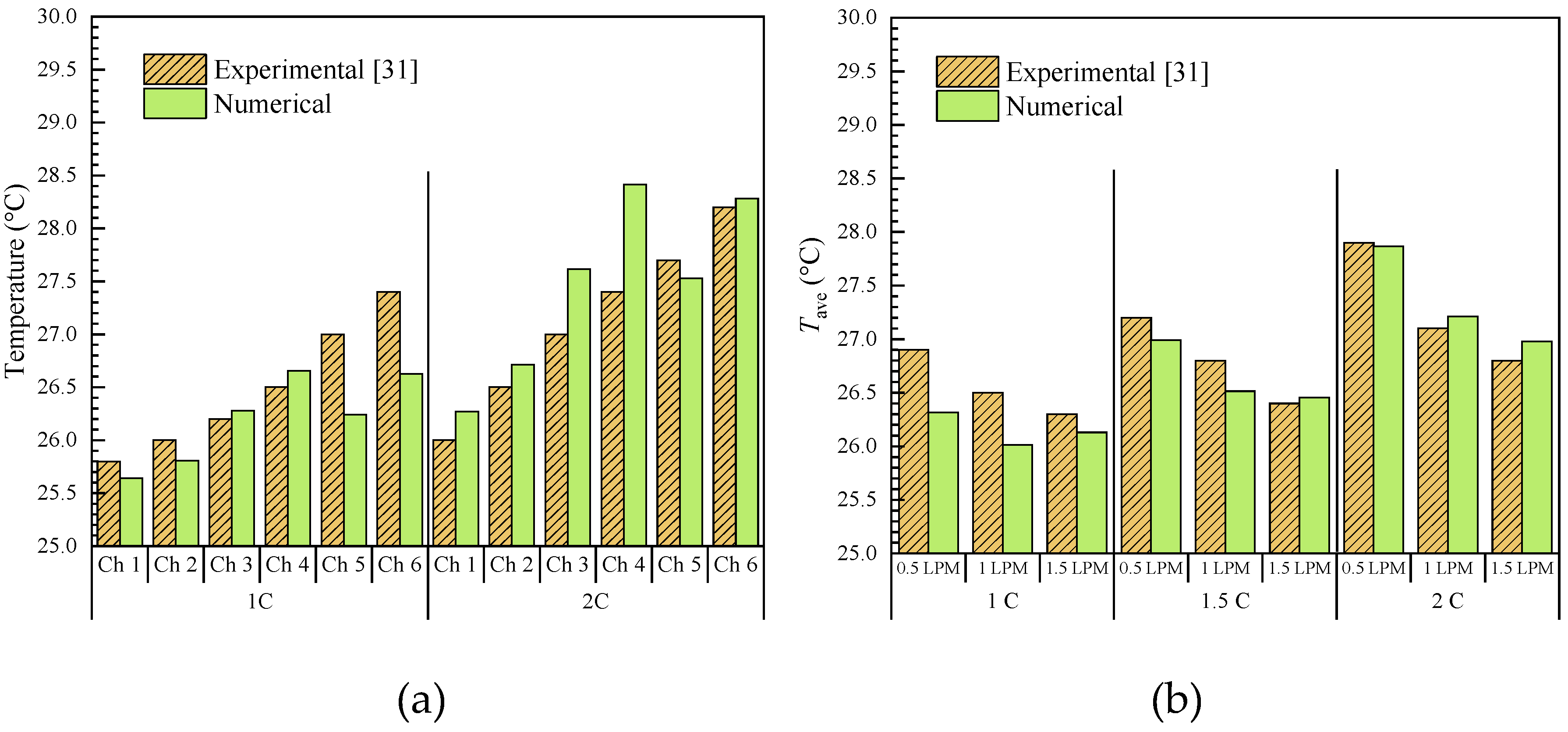

31] investigated the thermal performance of a Serpentine Channel Immersion Cooling (SCIC) system. The results showed that increasing the coolant flow rate enhances the heat transfer coefficient and reduces battery surface temperature, with a notable balance between heat dissipation and pumping power at 1 LPM (liters per minute).

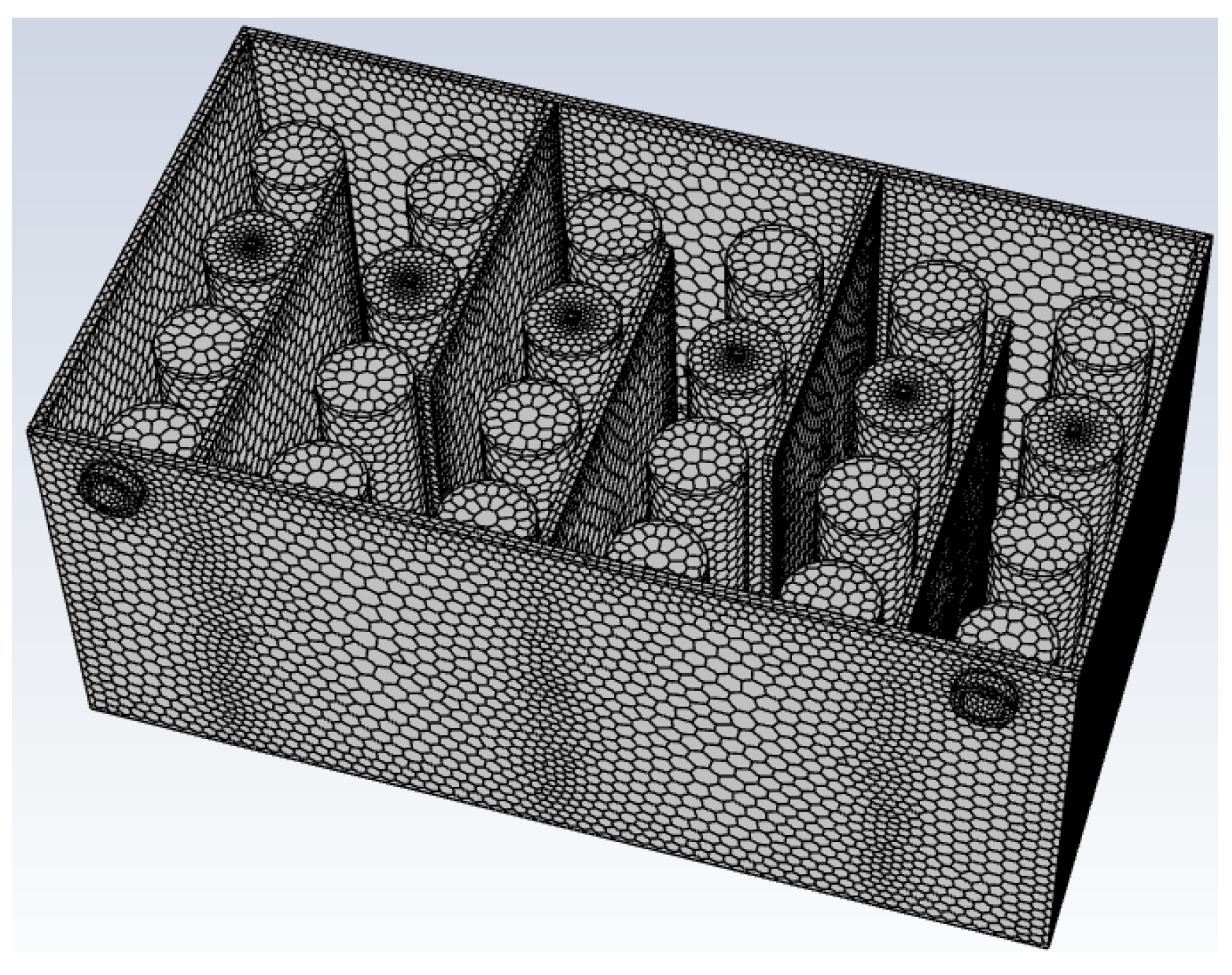

The above-mentioned studies demonstrate that improvements in the single-phase immersion cooling performance of batteries are mainly achieved through the use of higher-performance coolants or the optimization of flow channel structures. While structural optimization of flow channels has proven effective in enhancing heat dissipation, there remains a significant lack of quantitative research on the relationships between channel design parameters, operational parameters, and thermal response indicators—particularly the maximum battery temperature Tmax and pump power consumption Pw. Current research is largely confined to experimental validations or simulation trials based on discrete parameter values, with no universally applicable mathematical correlation model yet established. In this study, 18650-type lithium-ion batteries are selected as the research subject, and HFE-7100 was chosen as the immersion coolant. A battery thermal management model incorporating a serpentine channel configuration was developed using the ANSYS Fluent computational fluid dynamics platform. The focus is on investigating the impact mechanisms of key factors such as partition length, coolant flow velocity, and ambient temperature on thermal performance. To overcome the limitations of traditional single-variable analysis methods, this study employed Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to construct a quadratic polynomial regression model. Experimental conditions were designed using the Box-Behnken Design (BBD) approach, enabling systematic quantification of the contributions of each design variable and their interactions on Tmax and Pw. This mathematical model accurately captures the nonlinear variation patterns of thermal responses under multi-parameter coupling conditions, providing a solid theoretical foundation for the optimized design of immersion cooling systems.

4. Conclusions

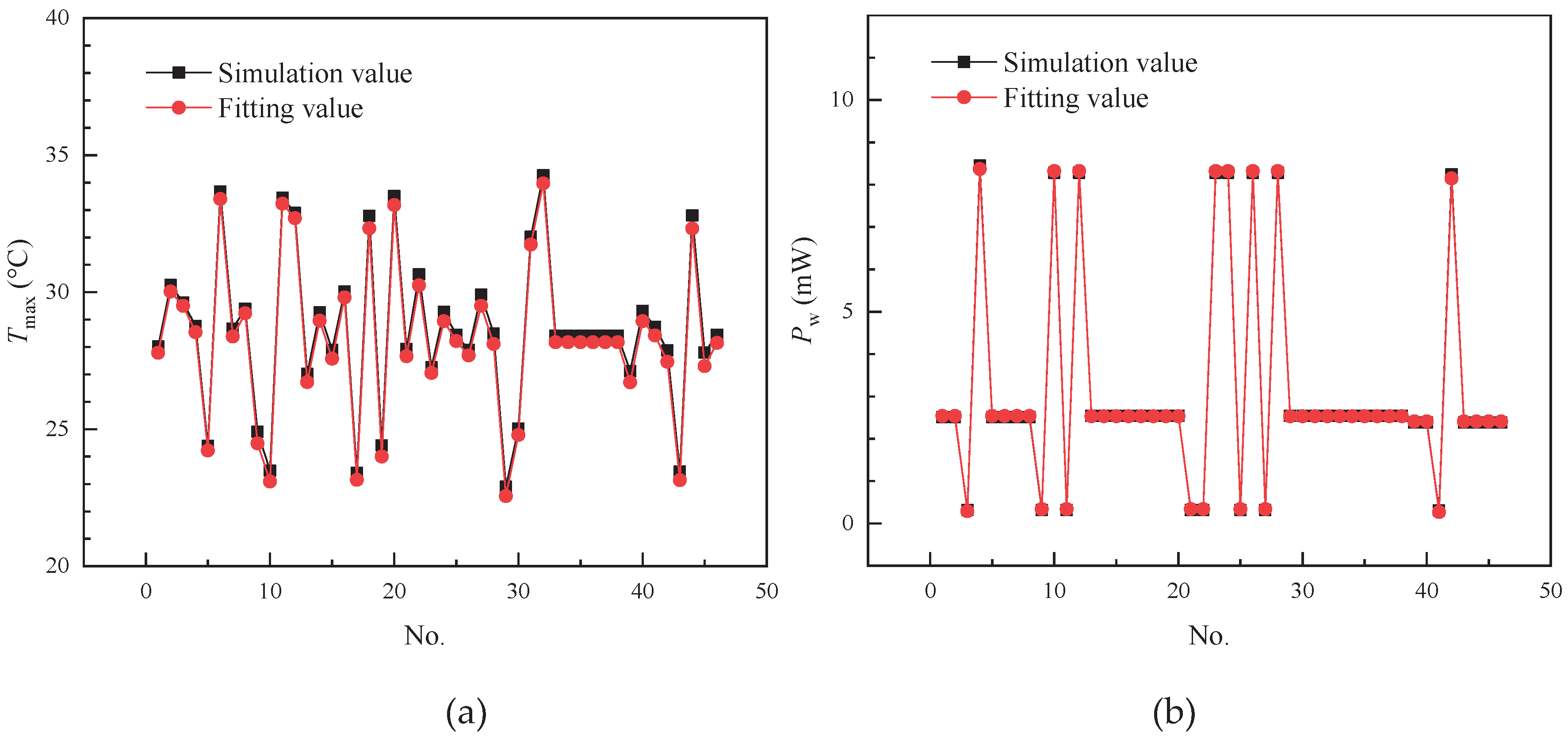

This paper investigates the immersion cooling performance of 18650 lithium-ion power batteries in a serpentine channel. Using a Box-Behnken Design, several key design factors were selected, including coolant flow rate, coolant inlet temperature, battery discharge rate, partition length, and ambient temperature. The maximum battery temperature and pump power consumption were chosen as the response variables. Computational Fluid Dynamics methods were employed to simulate and calculate these responses. The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) method was applied to systematically evaluate the statistical significance and relative importance of each design variable on the two response variables. Key conclusions are summarized as follows:

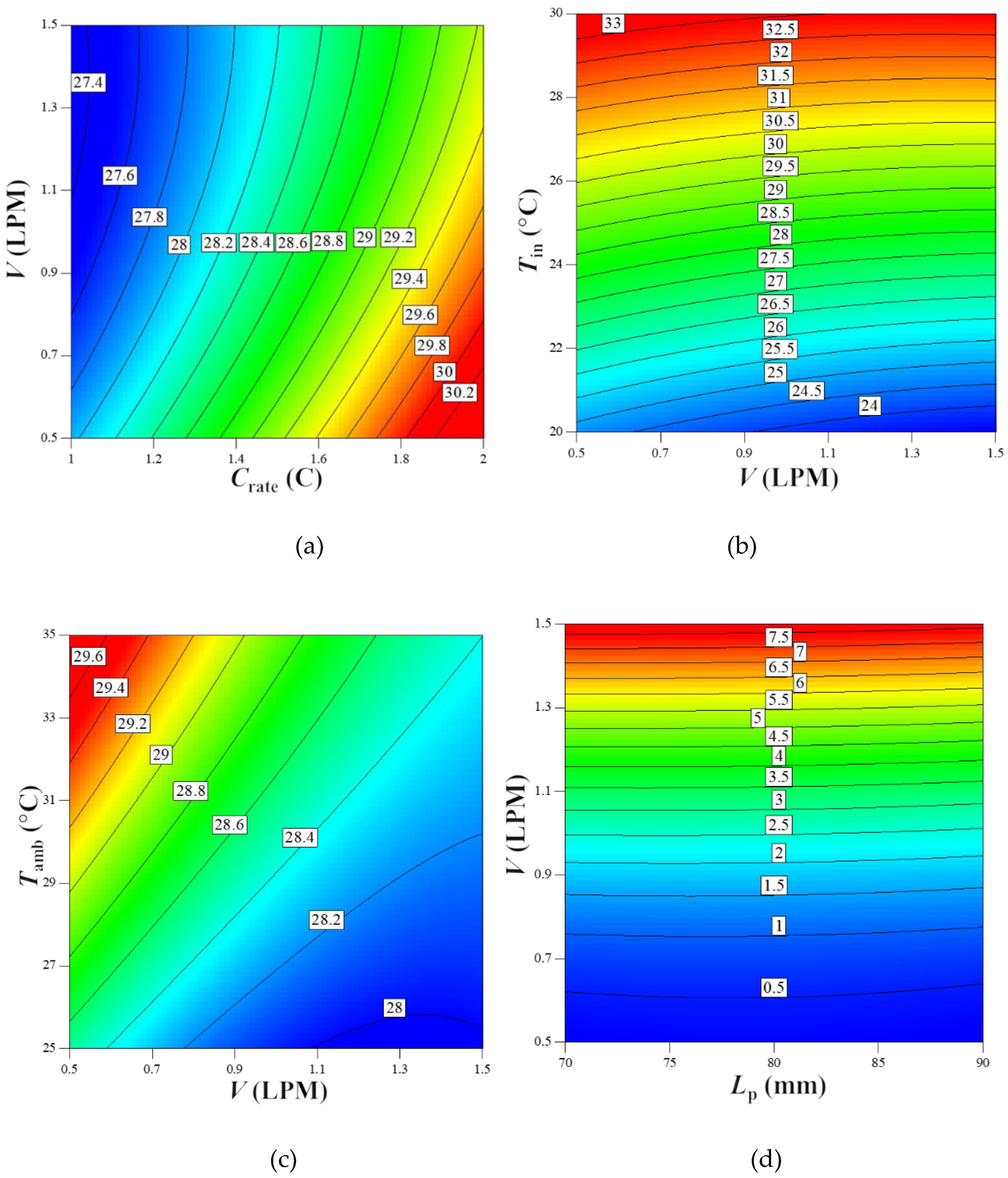

(1) For the Tmax response, the ANOVA revealed a clear hierarchy of factor influence: the main effects were ranked as Tin > Crate > V > Lp > Tamb. Among these, the Tin factor demonstrated overwhelming dominance, with its exceptionally high F-value reaching 48033.91 and a sum of squares of 336.81. These values significantly exceeded those of other variables, indicating that Tin is the most critical factor governing Tmax. Additionally, two interaction effects, V·Tin and V·Tamb, also showed significant effects (F=26.37), suggesting their synergistic influences cannot be ignored.

(2) For the Pw response, the ANOVA results provided equally important insights: both the main effect of V and its squared term (V2) exhibited extreme significance (F-values of 275000 and 35538.51, respectively). This indicates that the effect of V on Pw is not only highly significant but also exhibits a strong non-linear relationship. In contrast, the main effect of Lp and its squared term (Lp2) had relatively minor effects (F-values of 67.45 and 37.33, respectively). Although the Lp·V interaction effect was statistically significant (F=10.79), its magnitude was far lower than the main effects and squared terms. This finding provides crucial guidance for modeling the Pw response: priority should be given to the main effect and non-linear effect of V, while interaction effects can be considered secondary adjustment factors.

(3) After optimization targeting minimization of Tmax, Tave and Pw, the optimal design values for Lp, Crate, V, Tin, and Tamb were determined to be 89.5 mm, 1.08 C, 0.51 LPM, 20 °C, and 25.62°C respectively. The corresponding optimized values are: Tmax = 22.87°C, Tave = 21.67°C, and Pw = 0.279 mW.

This study clarifies the significant effects and hierarchical structure of various factors on Tmax and Pw, thereby providing a theoretical foundation and practical guidance for parameter optimization in complex systems.