1. Introduction

Continuous monitoring of glucose dynamics is of great clinical and physiological importance, particularly in detecting subtle metabolic changes that may not be captured by routine testing. Interstitial fluid glucose (ISFG) monitoring has emerged as a minimally invasive approach that enables dynamic assessment of glucose fluctuations in real-world and clinical settings. Over the past two decades, numerous studies have explored ISFG monitoring in a wide range of contexts [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Research has extensively examined postprandial glucose responses to dietary intake [

1,

2], as well as applications in patients undergoing dialysis, where glycemic control is often complicated by altered metabolic homeostasis [

3,

4]. In addition, ISFG monitoring has been integrated into broader metabolic and lifestyle research, including exercise physiology, stress-related responses, and circadian rhythm assessments [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Collectively, these findings underscore the versatility of ISFG monitoring as a tool for capturing physiologically relevant glucose fluctuations.

One particularly critical application of ISFG monitoring is the detection and characterization of nocturnal hypoglycemia. Nocturnal hypoglycemia is often asymptomatic and thus difficult to recognize in routine care, yet it is associated with serious acute and long-term consequences, including cardiovascular stress, impaired neurocognitive function, and increased mortality risk. In recent years, this condition has received growing attention in both basic and clinical research. Studies have proposed predictive and detection technologies that leverage continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), machine learning algorithms, and multimodal sensor integration to improve recognition of nocturnal hypoglycemia in real time [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Parallel to these technological advances, clinical investigations have emphasized the impact of nocturnal hypoglycemia on patient management, with specific focus on treatment intensification, individualized insulin titration, and patient education strategies [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Furthermore, therapeutic innovations such as modified insulin formulations, adjunct pharmacotherapies, and tailored behavioral interventions have been explored to reduce the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Beyond applied technologies and clinical interventions, basic research has provided essential insights into the physiological mechanisms underlying nocturnal hypoglycemia. Several studies have highlighted the role of cortisol secretion patterns, which may contribute to early-morning glucose nadirs and altered counterregulatory responses [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Others have focused on the autonomic nervous system, where reduced sympathetic activation during sleep may impair glucose counter regulation and exacerbate the risk of hypoglycemia [

42,

47]. At a broader level, foundational work in pathophysiology and general conceptual frameworks has contextualized nocturnal hypoglycemia within the dynamics of circadian biology, endocrine regulation, and systemic energy balance [

41,

42]. Together, these studies emphasize that nocturnal hypoglycemia is a multifactorial condition, requiring a multimodal and interdisciplinary approach to monitoring, prediction, and intervention.

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain in integrating metabolic monitoring with physiological signals that reflect systemic responses during sleep. Standard ISFG or CGM devices provide valuable metabolic data, but they typically operate in isolation from other physiological parameters, limiting their ability to capture the complex interplay between glucose dynamics and sleep-related changes in autonomic, cardiovascular, and respiratory function. Recent progress in wearable technologies—particularly ring-type and wrist-worn sensors—offers an opportunity to overcome these limitations by enabling the simultaneous, noninvasive recording of heart rate, oxygen saturation, and activity levels. Such multimodal integration may be particularly advantageous for identifying subtle physiological correlates of nocturnal hypoglycemia, such as oxygen desaturation or altered heart rate variability, which can precede or accompany glycemic decline.

The present pilot study was designed to explore the feasibility of combining minimally invasive ISFG monitoring with a ring-type wearable device for simultaneous assessment of glucose and physiological signals during sleep. By applying time-series analyses to data collected from healthy participants, we aimed to identify associations between nocturnal glucose fluctuations and changes in cardiorespiratory parameters. This approach builds on prior research in both glucose monitoring and wearable biosensing, and represents an initial step toward developing low-burden, real-time systems capable of detecting unrecognized nocturnal hypoglycemia. Ultimately, such multimodal monitoring platforms could contribute to remote healthcare solutions and personalized interventions that improve safety and quality of life for individuals at risk of nocturnal metabolic disturbances.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Five healthy volunteers (1 female, mean age 55 ± 10 years) were recruited for this study. None of the participants reported a history of metabolic, cardiovascular, or sleep disorders, and none were taking medications that could affect glucose metabolism or autonomic function. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Engineering, Mie University (Approval number: 132, Approval date: February 19, 2025) and the Ethics Review Committee of Nagoya City University Hospital (Approval number: 60-18-0211, Approval date: March 22, 2019). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Sensors and Data Acquisition

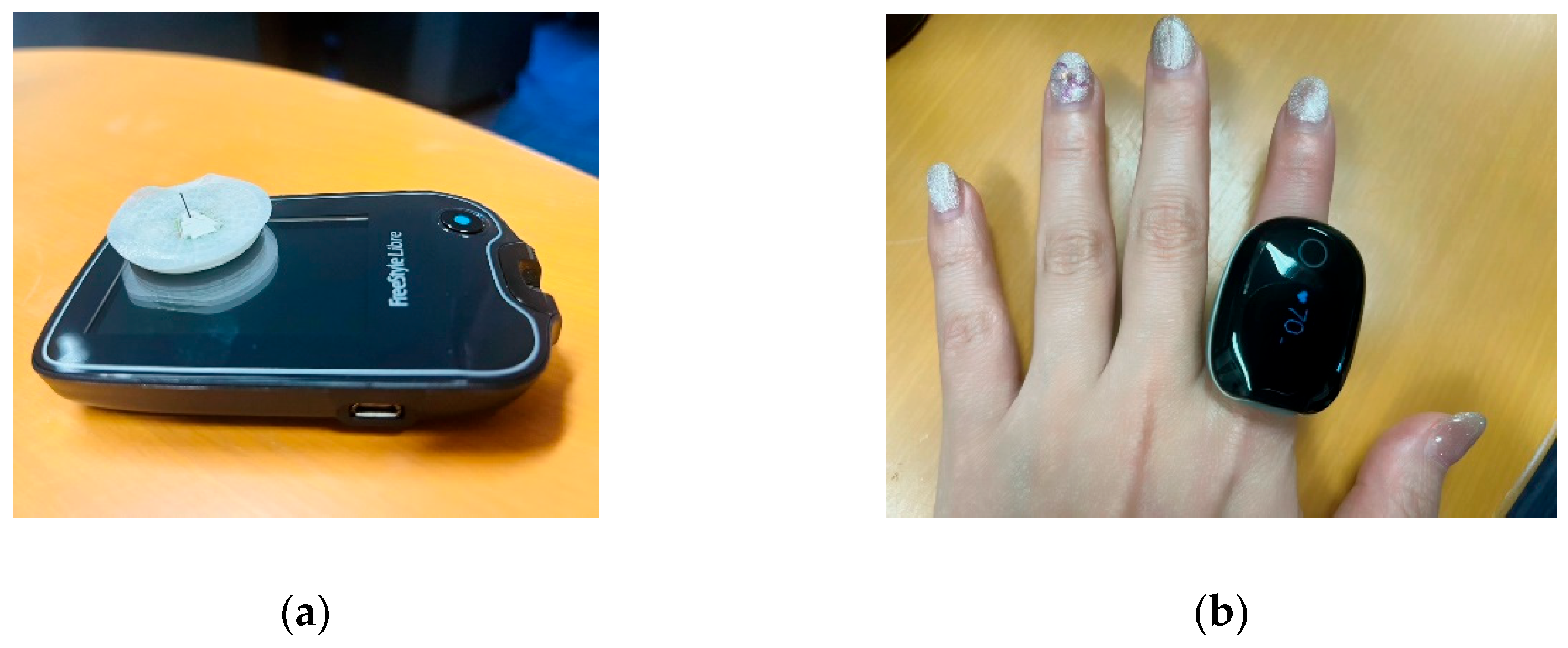

Participants simultaneously wore two types of sensors during the monitoring period; Interstitial Fluid Glucose (ISFG) Monitoring. A minimally invasive ISFG sensor (Libre, Abbott, USA) was placed on the upper arm. The device continuously recorded glucose concentrations at 15-minute intervals over a 14-day period. Physiological Signal Monitoring; a ring-type wearable device (Check-MeRing, Sanei Medisys, Kyoto, Japan; medical device certification number: 304AABZX00029000) was worn on the index finger of the non-dominant hand (Fig.1). The device continuously recorded heart rate (HR), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and actigraphy at a sampling rate of 0.25 Hz. Data were transferred to a smartphone via Bluetooth 4.0 BLE using the Check Me app and exported as CSV files. Measurement ranges were: SpO₂ 70–99%, HR 30–250 bpm. Measurement accuracy was specified as ±2% for SpO₂ between 80–99%, ±3% for SpO₂ between 70–79%, and ±2 bpm or ±2% (whichever was greater) for HR.

Data were collected during participants’ natural sleep periods, with a primary focus on the nighttime interval between 00:00 and 06:00. Participants were instructed to maintain their usual sleep routines and to refrain from alcohol or strenuous exercise on the day of measurement.

Figure 1.

Continuous monitoring of interstitial fluid glucose levels. Figure (a) shows a sensor used to measure glucose levels in interstitial fluid. It comes with an ultra-fine filament (needle) that is inserted into the skin during application. This is not designed to puncture the skin or leave the needle in place; instead, it is inserted into the skin's interstitial spaces to measure glucose concentration in the interstitial fluid. The filament reacts with glucose in the interstitial fluid using an enzyme inside the sensor, and the resulting weak electrical current is measured. The strength of this current is used to calculate blood glucose levels. Since there is no need to prick the fingertip with a needle, this method offers the advantage of reduced pain and discomfort compared to traditional blood glucose meters. Figure (b) shows the measurement using a ring-shaped sensor.

Figure 1.

Continuous monitoring of interstitial fluid glucose levels. Figure (a) shows a sensor used to measure glucose levels in interstitial fluid. It comes with an ultra-fine filament (needle) that is inserted into the skin during application. This is not designed to puncture the skin or leave the needle in place; instead, it is inserted into the skin's interstitial spaces to measure glucose concentration in the interstitial fluid. The filament reacts with glucose in the interstitial fluid using an enzyme inside the sensor, and the resulting weak electrical current is measured. The strength of this current is used to calculate blood glucose levels. Since there is no need to prick the fingertip with a needle, this method offers the advantage of reduced pain and discomfort compared to traditional blood glucose meters. Figure (b) shows the measurement using a ring-shaped sensor.

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

All physiological data were synchronized by timestamp. ISFG measurements were linearly interpolated to generate a continuous time series at 0.25 Hz, matching the sampling rate of the ring-type device. HR, SpO₂, and actigraphy signals were used as recorded, without filtering or smoothing.

The actigraphy signal was analyzed to confirm sleep onset and identify periods of excessive movement. Datasets with substantial motion artifacts during the target sleep interval were excluded. Resultant acceleration was calculated from the three-axis accelerometer embedded in the ring device, using:

where

ax,

ay, and

az represent accelerations along the three axes (units: g). This measure reflects changes in overall acceleration magnitude. Body position was further inferred from the tilt angle (

θ), calculated as the deviation of the vertical (Z-axis) component from gravity:

θ ≈ 0∘: Standing

θ ≈ 90∘: Supine, prone, or lateral recumbent (lying down)

The horizontal components (ax, ay) were used to distinguish between supine, prone, and lateral postures. In this study, this classification was used primarily to confirm lying-down status during sleep.

For glucose analysis, mean ISFG levels were computed for two consecutive intervals: the first half of sleep (0–3 h) and the second half (3–6 h). Paired t-tests were applied to compare ISFG levels between intervals, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. SpO₂ values were averaged in 1-hour bins, and visual inspection was used to identify common temporal patterns across participants. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

3. Results

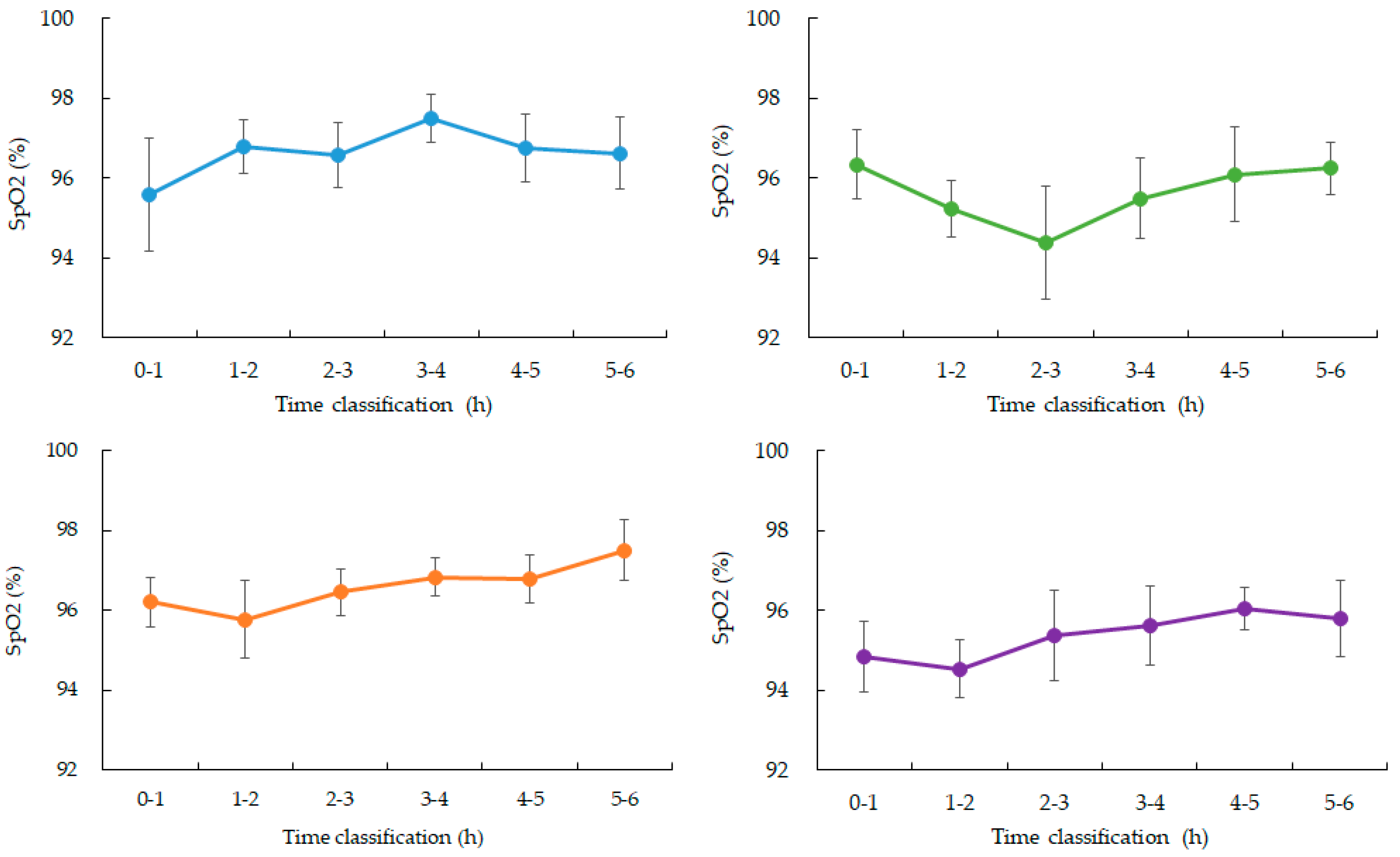

3.1. Interstitial Fluid Glucose (ISFG) Dynamics During Sleep

Between 00:00 and 06:00, four participants (Participants 1, 3, 4, and 5) showed a gradual and continuous decline in ISFG levels. In contrast, Participant 2 maintained relatively stable ISFG values without a clear downward trend (

Figure 2,

Table 1).

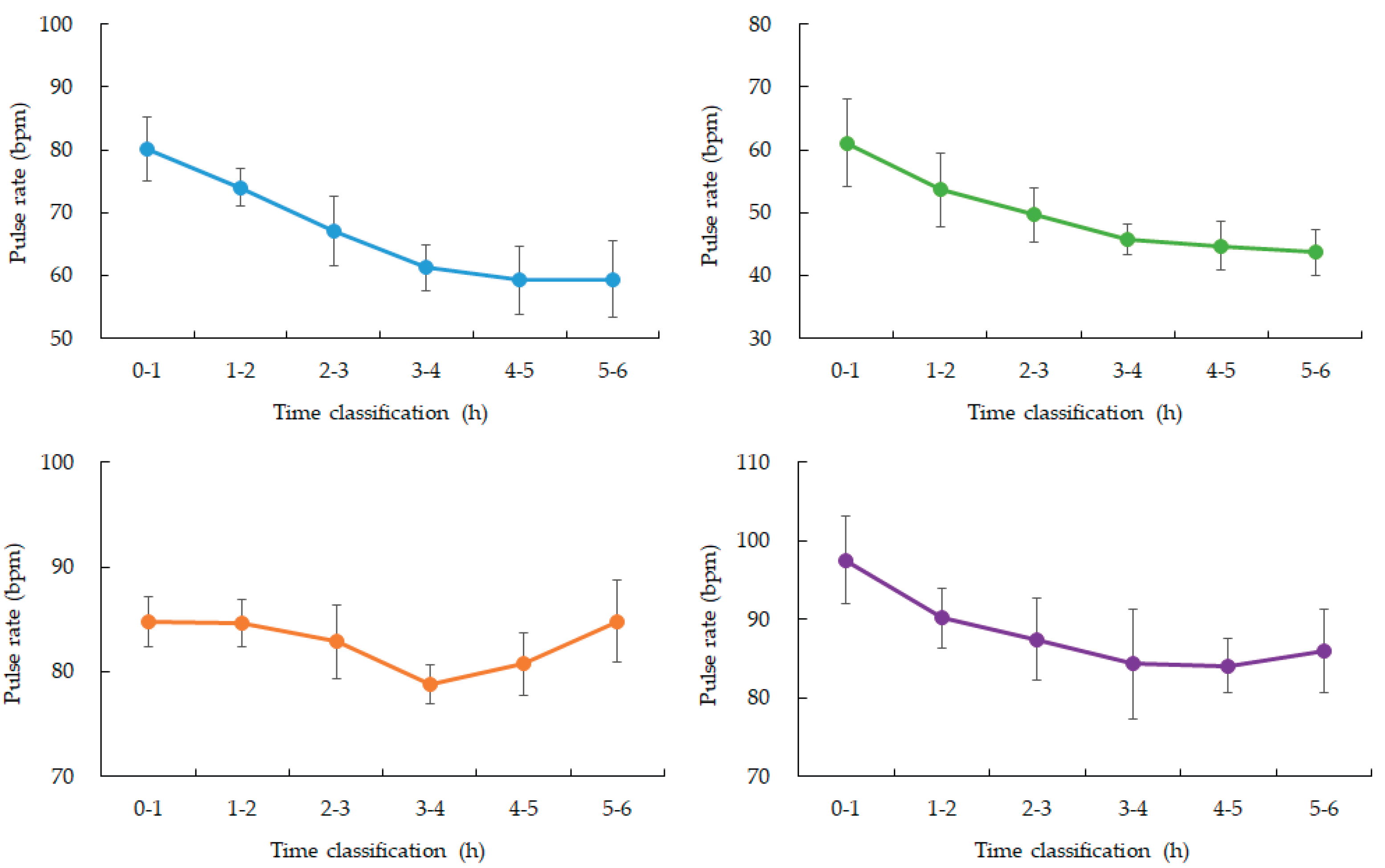

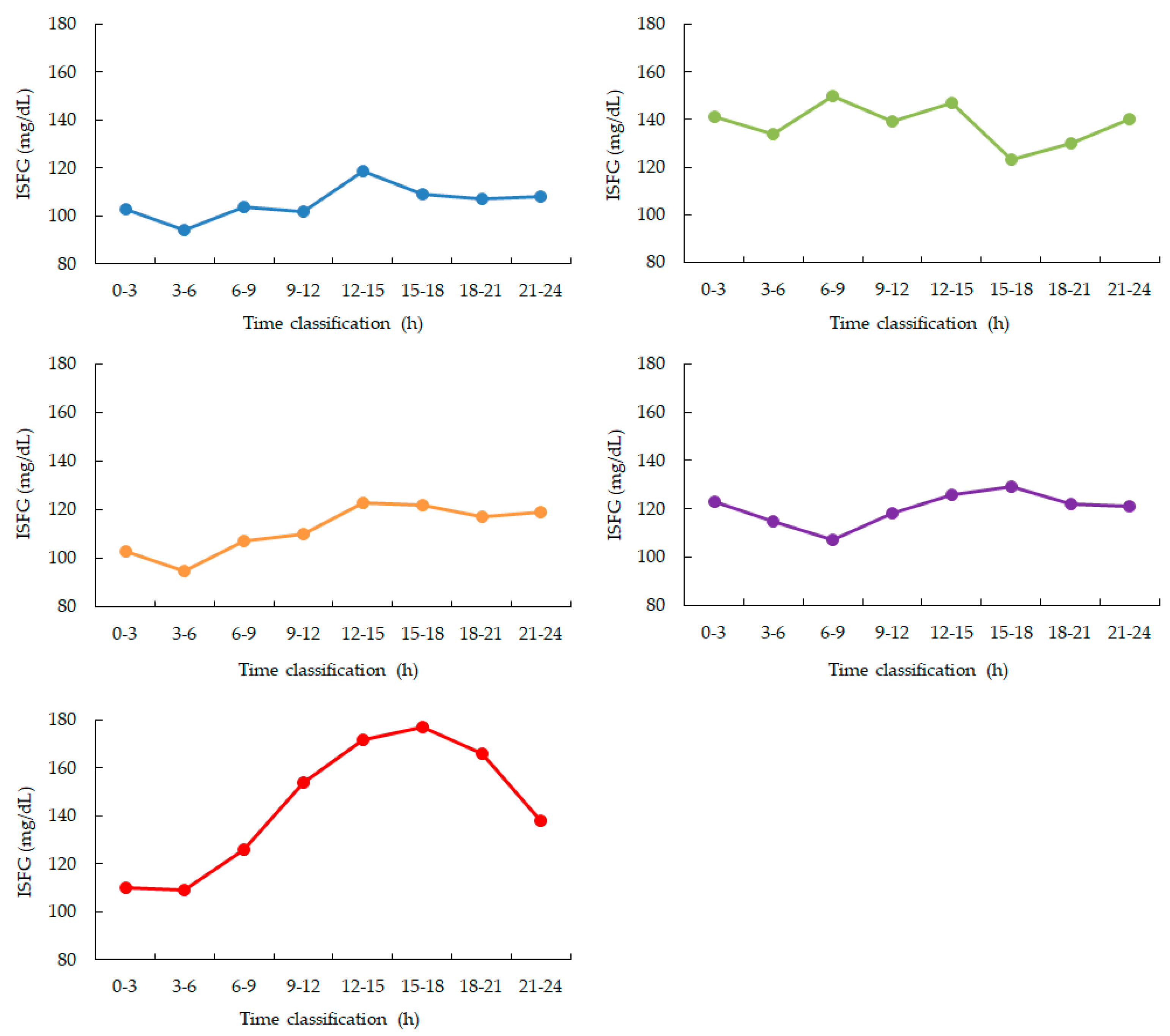

3.2. Peripheral Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂), Heart Rate, and Motion

SpO₂ values were stable during the early sleep phases but showed a mild decline between 03:00 and 04:00 in four participants, with mean values decreasing by approximately 1–2% compared to earlier periods. Data from one participant were excluded due to device malfunction (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Heart rate showed the expected nocturnal slowing in all participants, with no arrhythmic events or abrupt fluctuations. Occasional minor HR increases coincided with motion artifacts, though large body movements were uncommon during the main sleep intervals (

Table 2).

3.3. Quantitative Analysis

Comparison of ISFG levels between the 0–3 h and 3–6 h intervals revealed a significant reduction in the latter. A paired t-test confirmed that this decrease was statistically significant (p = 0.01).

Blue: participant 1, Green: participant 2, Orange: participant 3, Purple: participant 4, Red: participant 5. ISFG is measured as a 3-hour average. During nighttime sleep, ISFG decreased in 4 out of 5 participants from 0:00 to 6:00. After that, ISFG increased in 4 participants (participants 1, 3, 4, and 5) from 12:00 to 15:00 and then gradually decreased throughout the night.

Figure 3.

Changes in average SpO2 over time during nighttime sleep.

Figure 3.

Changes in average SpO2 over time during nighttime sleep.

Blue: participant 1, Green: participant 2, Orange: participant 3, Purple: participant 4. Hourly averages and standard deviations from 0 to 6:00 am. Participants 1, 3, and 4 showed a gradual increase from 3 to 4:00 am. after falling asleep. Participant 2, who had the highest ISFG among participants, showed a rapid decrease from 2 to 3:00 am. after falling asleep, and then recovered. (Data for participant 5 is missing)

Figure 4.

Changes in average SpO2 over time during nighttime sleep.

Figure 4.

Changes in average SpO2 over time during nighttime sleep.

Blue: participant 1, Green: participant 2, Orange: participant 3, Purple: participant 4. Hourly averages and standard deviations from 0:00 to 6:00. All four participants experienced a gradual decrease from 3:00 to 4:00 after going to bed.

Due to missing data, we were unable to obtain biosignal data during sleep from participant 5.

4. Discussion

This pilot study investigated nocturnal interstitial fluid glucose (ISFG) dynamics in healthy individuals using a multimodal monitoring system that combined minimally invasive glucose sensing with a ring-type wearable device capable of recording heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and motion. Our findings highlight characteristic overnight patterns of glucose fluctuation and provide preliminary evidence for their physiological correlates, supporting the feasibility of continuous, multimodal monitoring in non-clinical environments.

A consistent reduction in ISFG was observed in four out of five participants, with significantly lower values in the latter half of the sleep period (03:00–06:00) compared to the earlier half (00:00–03:00). This finding suggests sustained cerebral glucose utilization during sleep, even in the absence of food intake, and is consistent with prior reports emphasizing the brain’s high energy demand, particularly during non-REM sleep phases. The statistical significance of this decline (p = 0.01) further reinforces the reliability of the observed trend, despite the small cohort size.

Interestingly, a mild decline in SpO₂, temporally clustered around 03:00–04:00, was observed in most participants. Although these changes were within normal physiological ranges and did not suggest pathological hypoxemia, their timing in relation to the lowest ISFG levels may indicate subtle autonomic or sleep-stage transitions influencing both ventilatory regulation and glucose metabolism. This interplay raises the possibility that coordinated fluctuations in oxygenation and glucose levels represent early physiological signatures of metabolic stress, even in healthy populations.

Actigraphy confirmed that participants exhibited minimal motion throughout the monitored interval, supporting the interpretation that observed changes were attributable to sleep physiology rather than behavioral factors. HR followed the expected nocturnal decline consistent with parasympathetic predominance, further validating the physiological relevance of the glucose and oxygenation changes. Together, these findings underscore the value of synchronized multimodal monitoring for capturing subtle but meaningful shifts in systemic physiology during sleep.

Beyond the nocturnal period, we also noted a reproducible post-sleep rebound in ISFG between 12:00 and 15:00 in most participants. This may reflect circadian and behavioral influences such as dietary intake, activity levels, or hormonal rhythms, including cortisol peaks. Such findings highlight the importance of assessing both nocturnal and diurnal glucose dynamics in order to understand the broader context of metabolic regulation.

These results have potential implications for telemedicine and preventive healthcare. The integration of glucose, HR, SpO₂, and motion data offers a richer perspective than single-modality monitoring, particularly when paired with advanced analytical techniques such as anomaly detection or machine learning. This multimodal approach could enable the early detection of asymptomatic nocturnal hypoglycemia, thereby improving risk assessment and facilitating timely intervention in at-risk populations.

Compared with prior ISFG literature centered on meals [

1,

2], dialysis [

3,

4], device performance [

5,

6,

7,

8], or peri-operative contexts [

9], and distinct from prediction-algorithm or therapy-oriented advances [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], our study integrates minimally invasive glucose sensing with wearable cardio-respiratory and activity monitoring during sleep in healthy individuals. This multimodal, real-world, nocturnal focus fills a methodological gap by capturing coordinated metabolic and physiological fluctuations that are directly actionable for telemedicine workflows and that can feed contemporary predictive models and clinical decision pathways [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. The small sample size (n = 5) limits generalizability, and the absence of simultaneous polysomnography (PSG) prevents precise mapping of physiological fluctuations to sleep stages. Future studies incorporating PSG and larger, more diverse populations—including individuals with prediabetes, diabetes, or sleep disorders—are essential to validate and extend these findings. Moreover, longitudinal monitoring across multiple nights would capture intra-individual variability and strengthen the robustness of derived biomarkers.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the feasibility and potential of multimodal, minimally invasive monitoring to characterize nocturnal glucose and physiological dynamics in real-world settings. By bridging wearable technology, data science, and clinical medicine, such approaches hold promise for advancing proactive healthcare, enabling real-time detection of metabolic risk, and ultimately improving patient outcomes through personalized, continuous monitoring.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that interstitial fluid glucose (ISFG) levels typically decline during sleep in healthy individuals, with a statistically significant reduction observed between early and late sleep phases. Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) remained largely stable but showed a subtle decline in the mid-sleep period, while heart rate followed expected nocturnal slowing patterns without major disturbances. These findings highlight the feasibility of continuous, non-invasive monitoring using integrated wearable sensors to capture nocturnal metabolic and physiological dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Y. and H.E.; methodology, E.Y.; software, Y.Y.; validation, Y.Y., H.E. and J.H.; formal analysis, E.Y.; investigation, E.Y.; resources, H.E.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Y.; writing—review and editing, E.Y.; visualization, J.H.; supervision, E.Y.; project administration, E.Y.; funding acquisition, E.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Engineering, Mie University (Approval number: 132, Approval date: February 19, 2025) and the Ethics Review Committee of Nagoya City University Hospital (Approval number: 60-18-0211, Approval date: March 22, 2019). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Takahashi, R.; Yoshida, T.; Toku, H.; Otsuki, N.; Hosaka, T. Impact of Meal Timing on Postprandial Interstitial Fluid Glucose Levels in Young Japanese Females. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 2020, 66, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlup, R.; Jelenová, D.; Kudlová, P.; Chlupová, K.; Bartek, J.; Zapletalová, J.; Langová, K.; Chlupová, L. Continuous glucose monitoring -- a novel approach to the determination of the glycaemic index of foods (DEGIF 1) -- determination of the glycaemic index of foods by means of the CGMS. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2006, 114, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, T.; Takahashi, H.; Yasuda, K. Comparison of Interstitial Fluid Glucose Levels Obtained by Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Flash Glucose Monitoring in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Undergoing Hemodialysis. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornet, S.; Moranne, O.; Jouret, F.; Parotte, M.C.; Georges, B.; Godon, E.; Cavalier, E.; Radermecker, R.P.; Delanaye, P. Performance of an interstitial glucose monitoring device in patients with type 1 diabetes during haemodialysis. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellinger, E.; Brandt, T.; Creutzburg, J.; Rommerskirchen, T.; Schmidt, A. Analytical Performance of the FreeStyle Libre 2 Glucose Sensor in Healthy Male Adults. Sensors 2024, 24, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekido, K.; Sekido, T.; Kaneko, A.; Hosokawa, M.; Sato, A.; Sato, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Komatsu, M. Careful readings for a flash glucose monitoring system in nondiabetic Japanese subjects: individual differences and discrepancy in glucose concentrarion after glucose loading [Rapid Communication]. Endocr. J. 2017, 64, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagła, M.; Szymońska, I.; Starzec, K.; Kwinta, P. Preterm Glycosuria - New Data from a Continuous Glucose Monitoring System. Neonatology 2018, 114, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afeef, S.; Tolfrey, K.; Zakrzewski-Fruer, J.K.; Barrett, L.A. Performance of the FreeStyle Libre Flash Glucose Monitoring System during an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test and Exercise in Healthy Adolescents. Sensors 2023, 23, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusunoki, E.; Hidenori, K.; Kusano, M.; Teranishi, R.; Shibuya, H.; Okada, T. Continuous Interstitial Subcutaneous Fluid Glucose (ISFG) Measurement during Pre- and Intraoperative Periods for Highly Invasive Surgery. Masui 2016, 65, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kulzer, B.; Freckmann, G.; Ziegler, R.; Schnell, O.; Glatzer, T.; Heinemann, L. Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in the Era of Continuous Glucose Monitoring. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2024, 18, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; King, F.; Kohn, M.A.; Spanakis, E.K.; Breton, M.; Klonoff, D.C. A Review of Predictive Low Glucose Suspend and Its Effectiveness in Preventing Nocturnal Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2019, 21, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, L.; Kefayati, S.; Idé, T.; Pavuluri, V.; Jackson, G.; Latts, L.; Zhong, Y.; Agrawal, P.; Chang, Y.C. Predicting Nocturnal Hypoglycemia from Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data with Extended Prediction Horizon. AMIA Annu. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2019, 874–882. [Google Scholar]

- Kronborg, T.; Hangaard, S.; Hejlesen, O.; Vestergaard, P.; Jensen, M.H. Bedtime Prediction of Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in Insulin-Treated Type 2 Diabetes Patients. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2024, 18, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Lopez, C.; Dodier, R.; Tyler, N.S.; Wilson, L.M.; El Youssef, J.; Castle, J.R.; Jacobs, P.G. Predicting and Preventing Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in Type 1 Diabetes Using Big Data Analytics and Decision Theoretic Analysis. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2020, 22, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.Q.; Chai, R.; Nguyen, T.V.; Jones, T.W.; Nguyen, H.T. Electroencephalogram Spectral Moments for the Detection of Nocturnal Hypoglycemia. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.Q.; Chai, R.; Nguyen, T.V.; Jones, T.W.; Nguyen, H.T. Nocturnal Hypoglycemia Detection using EEG Spectral Moments under Natural Occurrence Conditions. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2019, 7177–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.H.; Dethlefsen, C.; Vestergaard, P.; Hejlesen, O. Prediction of Nocturnal Hypoglycemia From Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data in People With Type 1 Diabetes: A Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, C.Q.; Chai, R.; Nguyen, T.V.; Jones, T.W.; Nguyen, H.T. Nocturnal Hypoglycemia Detection using Optimal Bayesian Algorithm in an EEG Spectral Moments Based System. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2019, 5439–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afentakis, I.; Unsworth, R.; Herrero, P.; Oliver, N.; Reddy, M.; Georgiou, P. Development and Validation of Binary Classifiers to Predict Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in Adults With Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2025, 19, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Z. Data-based modeling for hypoglycemia prediction: Importance, trends, and implications for clinical practice. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1044059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertachi, A.; Viñals, C.; Biagi, L.; Contreras, I.; Vehí, J.; Conget, I.; Giménez, M. Prediction of Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes under Multiple Daily Injections Using Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Physical Activity Monitor. Sensors 2020, 20, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boureau, A.S.; Guyomarch, B.; Gourdy, P.; Allix, I.; Annweiler, C.; Cervantes, N.; Chapelet, G.; Delabrière, I.; Guyonnet, S.; Litke, R.; Paccalin, M.; Penfornis, A.; Saulnier, P.J.; Wargny, M.; Hadjadj, S.; de Decker, L.; Cariou, B. Nocturnal hypoglycemia is underdiagnosed in older people with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: The HYPOAGE observational study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 2107–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Abdelhamid, Y.; Bernjak, A.; Phillips, L.K.; Summers, M.J.; Weinel, L.M.; Lange, K.; Chow, E.; Kar, P.; Horowitz, M.; Heller, S.; Deane, A.M. Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in Patients With Diabetes Discharged From ICUs: A Prospective Two-Center Cohort Study. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, S.V.; Blose, J.S. The Impact of Nocturnal Hypoglycemia on Clinical and Cost-Related Issues in Patients With Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiroty, K.; Al Sabahi, A. Severe Recurrent Nocturnal Hypoglycemia During Chemotherapy With 6-mercaptopurine in 2 Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 45, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, N.; Luo, Y.W.; Xu, J.D.; Zhang, Y. Abnormal nocturnal behavior due to hypoglycemia: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e14405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, K.; Suzuki, S.; Koga, S.; Kuwabara, K. A comprehensive risk assessment for nocturnal hypoglycemia in geriatric patients with type 2 diabetes: A single-center case-control study. J. Diabetes Complications 2022, 36, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urakami, T. Severe Hypoglycemia: Is It Still a Threat for Children and Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes? Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamborlane, W.V. Triple jeopardy: nocturnal hypoglycemia after exercise in the young with diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 815–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.M.; Calhoun, P.M.; Maahs, D.M.; Chase, H.P.; Messer, L.; Buckingham, B.A.; Aye, T.; Clinton, P.K.; Hramiak, I.; Kollman, C.; Beck, R.W.; In Home Closed Loop Study Group. Factors associated with nocturnal hypoglycemia in at-risk adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2015, 17, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormazábal-Aguayo, I.; Huerta-Uribe, N.; Muñoz-Pardeza, J.; Ezzatvar, Y.; Izquierdo, M.; García-Hermoso, A. Association of Physical Activity Patterns With Nocturnal Hypoglycemia Events in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggers, J.R.; King, K.M.; Watson, S.E.; Wintergerst, K.A. Predicting Nocturnal Hypoglycemia with Measures of Physical Activity Intensity in Adolescent Athletes with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2019, 21, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunton, S.A. Nocturnal hypoglycemia: answering the challenge with long-acting insulin analogs. MedGenMed 2007, 9, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K.V.; Frier, B.M. Nocturnal hypoglycemia: clinical manifestations and therapeutic strategies toward prevention. Endocr. Pract. 2003, 9, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baretić, M.; Kraljević, I.; Renar, I.P. NOCTURNAL HYPOGLYCEMIA--THE MAIN INDICATION FOR INSULIN PUMP THERAPY IN ADULTHOOD. Acta Clin. Croat. 2016, 55, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brøsen, J.M.B.; Agesen, R.M.; Alibegovic, A.C.; Ullits Andersen, H.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Gustenhoff, P.; Krarup Hansen, T.; Hedetoft, C.G.R.; Jensen, T.J.; Stolberg, C.R.; Bogh Juhl, C.; Lerche, S.S.; Nørgaard, K.; Parving, H.H.; Tarnow, L.; Thorsteinsson, B.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, U. Continuous Glucose Monitoring-Recorded Hypoglycemia with Insulin Degludec or Insulin Glargine U100 in People with Type 1 Diabetes Prone to Nocturnal Severe Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2022, 24, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.J.; Forse, R.A. Nutritional management of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Educ. 1999, 25, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P. Insulin pump therapy with automated insulin suspension: toward freedom from nocturnal hypoglycemia. JAMA 2013, 310, 1235–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Lopez, C.; Roquemen-Echeverri, V.; Tyler, N.S.; Patton, S.R.; Clements, M.A.; Martin, C.K.; Riddell, M.C.; Gal, R.L.; Gillingham, M.; Wilson, L.M.; Castle, J.R.; Jacobs, P.G. Combining uncertainty-aware predictive modeling and a bedtime Smart Snack intervention to prevent nocturnal hypoglycemia in people with type 1 diabetes on multiple daily injections. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2023, 31, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; GhavamiNejad, A.; Liu, J.F.; Li, J.; Mirzaie, S.; Giacca, A.; Wu, X.Y. "Smart" Composite Microneedle Patch Stabilizes Glucagon and Prevents Nocturnal Hypoglycemia: Experimental Studies and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 20576–20590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, H.P. Nocturnal hypoglycemia--an unrelenting problem. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 2038–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Schneider, D. Hypoglycemia. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, S17–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siamashvili, M.; Davis, H.A.; Davis, S.N. Nocturnal hypoglycemia in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: an update on prevalence, prevention, pathophysiology and patient awareness. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 16, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, S.; Auderset, A.; Burckhardt, M.A.; Szinnai, G.; Hess, M.; Zumsteg, U.; Denhaerynck, K.; Donner, B. Autonomic cardiac regulation during spontaneous nocturnal hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2021, 22, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Abu Irsheed, G.M.; Martyn-Nemeth, P.; Reutrakul, S. Type 1 Diabetes, Sleep, and Hypoglycemia. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2021, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryer, P.E.; Binder, C.; Bolli, G.B.; Cherrington, A.D.; Gale, E.A.; Gerich, J.E.; Sherwin, R.S. Hypoglycemia in IDDM. Diabetes 1989, 38, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.S.; Scandrett, M.S. Nocturnal cortisol release during hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care 1981, 4, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).