1. Introduction

Sleep apnea syndrome (SAS) is a prevalent and serious sleep disorder characterized by repeated interruptions of breathing during sleep. These interruptions, or apneas, lead to a decrease in blood oxygen levels and place a considerable strain on the cardiovascular system [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. SAS, through recurrent apneic events, leads to hypoxemia and blood pressure fluctuations. In response to hypoxia, the heart works harder to deliver sufficient oxygen, resulting in elevated blood pressure and increased stress on blood vessels, which subsequently raises the risk of cardiovascular events like stroke and myocardial infarction.

In recent years, SAS has drawn increasing attention from researchers and clinicians due to its association with cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, and notably, stroke. Studies show that the risk of stroke is 2.8 times higher in patients with SAS compared to healthy individuals, and among those with severe SAS, the risk rises to approximately 3.6 times that of healthy individuals [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Moreover, stroke itself can disrupt normal breathing patterns, sometimes resulting in central sleep apnea syndrome. During the recovery period from stroke, neuroplasticity (the brain’s capacity to grow or reorganize neural networks) is essential. And sleep disturbances such as central sleep apnea and insomnia are commonly observed in stroke patients and are concerning for their potential impact on neuroplasticity, potentially affecting recovery outcomes [

14,

15]. This bidirectional relationship; where SAS increases the risk of stroke and stroke can exacerbate sleep-related breathing disorders, underscores the importance of early detection and timely intervention. Recognizing the link between stroke and SAS can motivate individuals who may be at risk to reevaluate their sleep habits as part of a self-care regimen, as good sleep can contribute significantly to overall health and recovery from neurological events [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Consequently, early detection methods that are accessible, accurate, and comfortable for patients are essential for both prevention and management.

One promising biomarker for SAS detection is the cyclic variation of heart rate (CVHR), a distinctive pattern of heart rate fluctuation in response to apneic episodes and subsequent recovery in blood oxygen levels [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Recent advancements in wearable sensor technology have enabled researchers to explore non-invasive, comfortable methods for CVHR monitoring that can enhance patient compliance and facilitate long-term observation in everyday settings. In particular, silicon-based ring sensors offer significant potential for monitoring CVHR, as they are comfortable to wear, unlikely to cause discomfort, and provide a visible record of physiological data, thus minimizing recording errors. Additionally, these sensors are cost-effective, which is advantageous for large-scale screenings and for populations who may otherwise lack access to standard sleep monitoring tools. For dementia patients, such technology can be especially beneficial. Individuals with cognitive impairment may have difficulty expressing discomfort or distress, making it challenging to assess sleep quality through self-report or behavioral cues. Wearable sleep sensors provide an objective means of evaluating sleep patterns, which can inform caregivers and healthcare providers in developing strategies for enhancing sleep and, by extension, overall well-being. Despite the appeal of wearable technology for sleep monitoring, certain challenges remain. The accuracy and reliability of CVHR detection using wearable sensors, especially compared to established methods like Holter ECG, are central to ongoing research. Studies have shown that CVHR values obtained from ring-type sensors may differ from those measured by traditional ECG, necessitating calibration to ensure reliability for clinical and self-monitoring applications. Moreover, understanding the variability of CVHR over time, including intra-weekly fluctuations, could provide further insights into how SAS and related disorders impact cardiovascular and autonomic functions in varying contexts, such as different sleep stages or stress levels [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

In this study, we aim to investigate the feasibility of using a ring-type silicon sensor to detect CVHR during sleep, focusing on both the device’s accuracy relative to Holter ECG and its capability to capture intra-weekly variability. Our study involves seven consecutive nights of monitoring in healthy subjects, measuring heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, and bio-acceleration, to provide a comprehensive picture of physiological status across sleep stages. By evaluating intra-weekly CVHR variability, it has potential offering a practical tool for SAS detection and more personalized, preventative care approaches in naturalistic settings, so our aim to assess the sensor’s sensitivity to subtle changes over time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

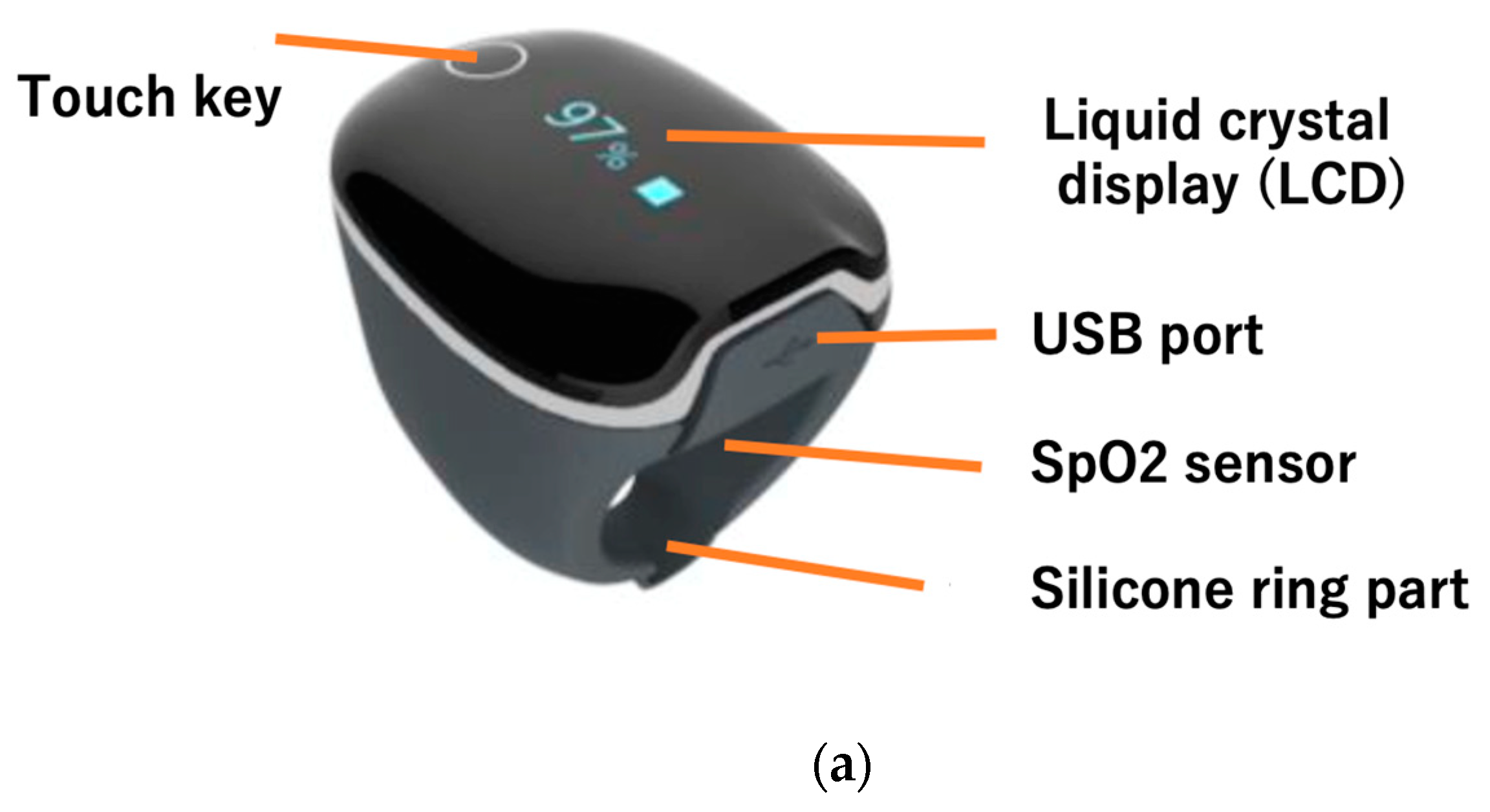

In this study, we used a ring-shaped silicon sensor (Check-me Ring, SAN-EI MEDISYS, Japan) for data measurement. This device is specially designed for comfortable, long-term physiological monitoring during sleep. The sensor is compact and lightweight, and fits snugly on the finger, minimizing discomfort even when worn overnight. This sensor detects heart rate, blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and acceleration.

The sensor is attached, the power automatically turns on and measurement begins a few seconds later. The display alternately shows the measured values of blood oxygen saturation (SpO

2) and heart rate (PR) (

Figure 1). Four sets of measurement data can be stored, with a maximum of 10 hours per set. The data can be exported to smartphone or tablet apps via Bluetooth. The device is typing BF (in medical electrical equipment, a connection part with protection against electric shock that is higher than that of a Type B connection part, and the patient connection part is separated from the other parts of the ME equipment), and uses electromagnetic compatibility. It weighs 15g, has external dimensions of 38 x 30 x 38 mm, and uses a 3.7Vdc (rechargeable lithium polymer) battery. It can be used for 12 to 16 hours under normal conditions. The wireless system uses Bluetooth 4.0 BLE, and the measurement range is SpO2 70-99 and heart rate 30-250 bpm. Measurement accuracy is SpO2 80-99 ±2% (in the 70-79 range, ±3%) and heart rate 30-250 ±2 (bpm).

The sensor conforms to the requirements of EN IEC 60601-1-2 for EMC of medical electrical equipment and medical electrical systems. Electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) refers to both the ability to prevent the emission of noise that could cause unacceptable interference to other electronic devices in the surrounding environment (electromagnetic emissions) and the ability to withstand the electromagnetic environment of the location where the device is used, including noise emitted from other electronic devices in the surrounding environment, and to function normally (electromagnetic immunity). Even if other devices conform to the requirements of the International Special Committee on Radio Interference (CISPR), they may still interfere with the sensor. In such cases, if the input signal falls below the minimum amplitude, there is a risk of incorrect measurement, so each subjects took care to avoid placing any electronic devices other than the smartphone for data transfer during measurement.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Continuous Measurement for One Week

We enrolled 8 healthy subjects (45.7 ± 10.1 years old, 2 females) and monitored heart rate, blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and bio-acceleration during sleep over seven consecutive nights using a ring-type silicon sensor. The sampling frequency was set at 5 Hz, and bio-acceleration data were used to calculate composite acceleration.

Data were recorded on each subject’s smartphone via the app (Check-me Ring Application, SAN-EI MEDISYS, Japan) through a wireless connection and collected in CSV format via cloud transfer. To protect privacy, subjects were identified using sensor serial numbers linked with participant ID numbers.

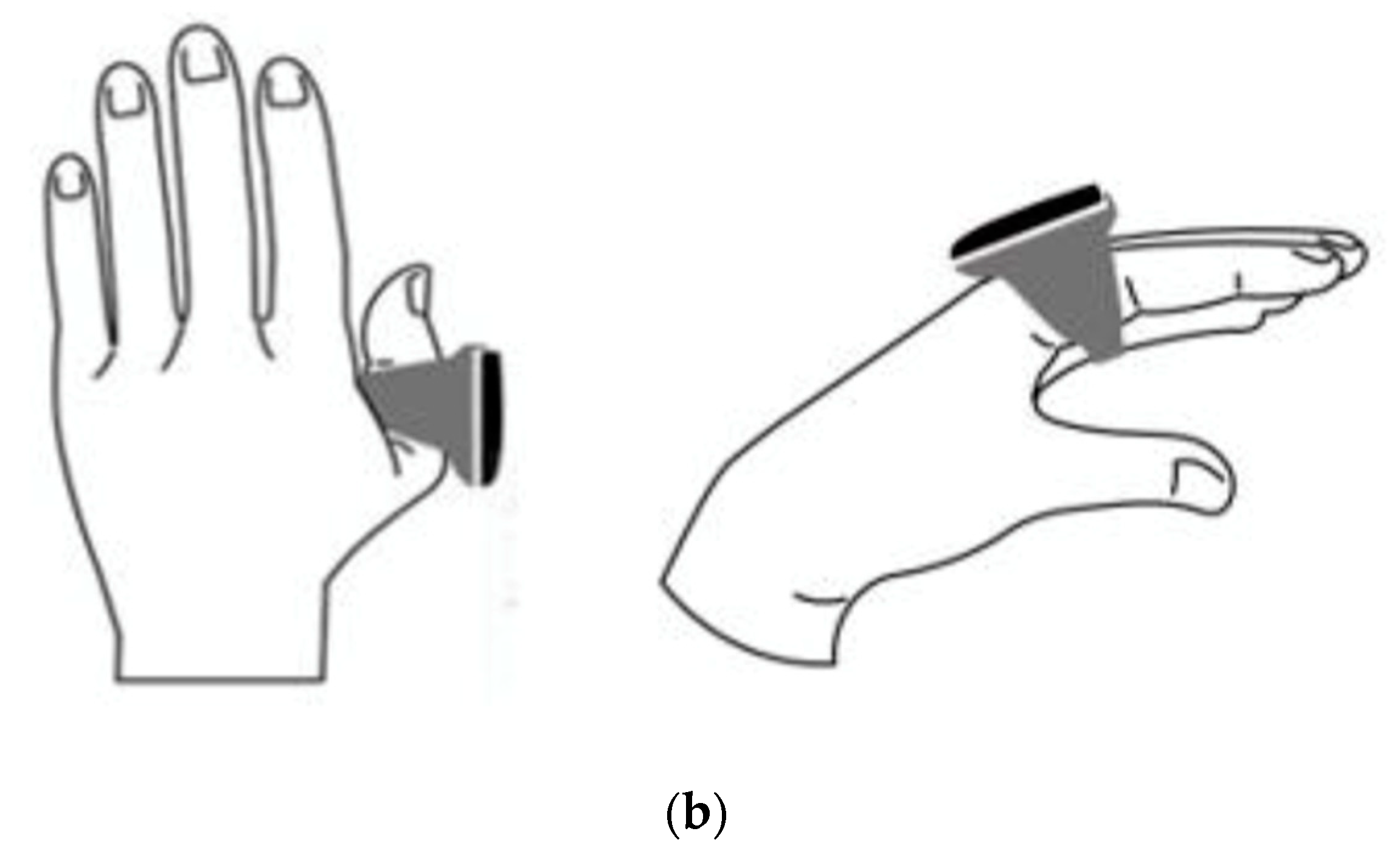

The ring is equipped with a liquid crystal display, which allows you to check human heart rate (a). The sensor embedded in the silicone measures acceleration and heart rate (medical device certification number is 304AABZX00029000, a specified maintenance management medical device). Figure (b) shows the position where the ring is attached. It is attached to the index finger or thumb and used.

2.2.2. Consistency with Holter Electrocardiograph (ECG)

In order to check the consistency of Holter electrocardiogram (ECG) data and ring-type silicon sensors, we compared Holter electrocardiogram (Poco303, Suzuken, Japan) data. The subject was one healthy female (38 years old) who wore both the Holter electrocardiogram and ring sensor to bed while sleeping. The data obtained from the Holter electrocardiograph was converted to CSV format using dedicated software (Cardy Analyzer, Kenz, Japan). The Holter ECG device can record electrocardiogram RR intervals and bio-acceleration. The RR interval sampling frequency was 125 Hz, and bio-acceleration was measured at 31.25 Hz.

2.2.3. Calculation of CVHR Frequency

The frequency of CVHR was calculated by comparing the aFcv values obtained from the silicon ring sensor at 1 Hz and 2 Hz, and the Oxygen Desaturation Index (ODI) was calculated from SpO

2 values, and the two were compared. The ODI is a value that appears in the results of a simple monitoring test for sleep apnea syndrome, and it refers to the index of oxygen desaturation. The ODI is a value obtained by counting the number of times the SpO

2 of arterial blood drops by 3% or more during sleep, while a pulse oximeter is attached to the wrist, and it is considered normal if it is less than 15 times per hour [

31]. Here, we will define sleep apnea as a 3% ODI, in accordance with previous research.

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Between Holter ECG and CVHR Values for Ring-Tyoe Senser

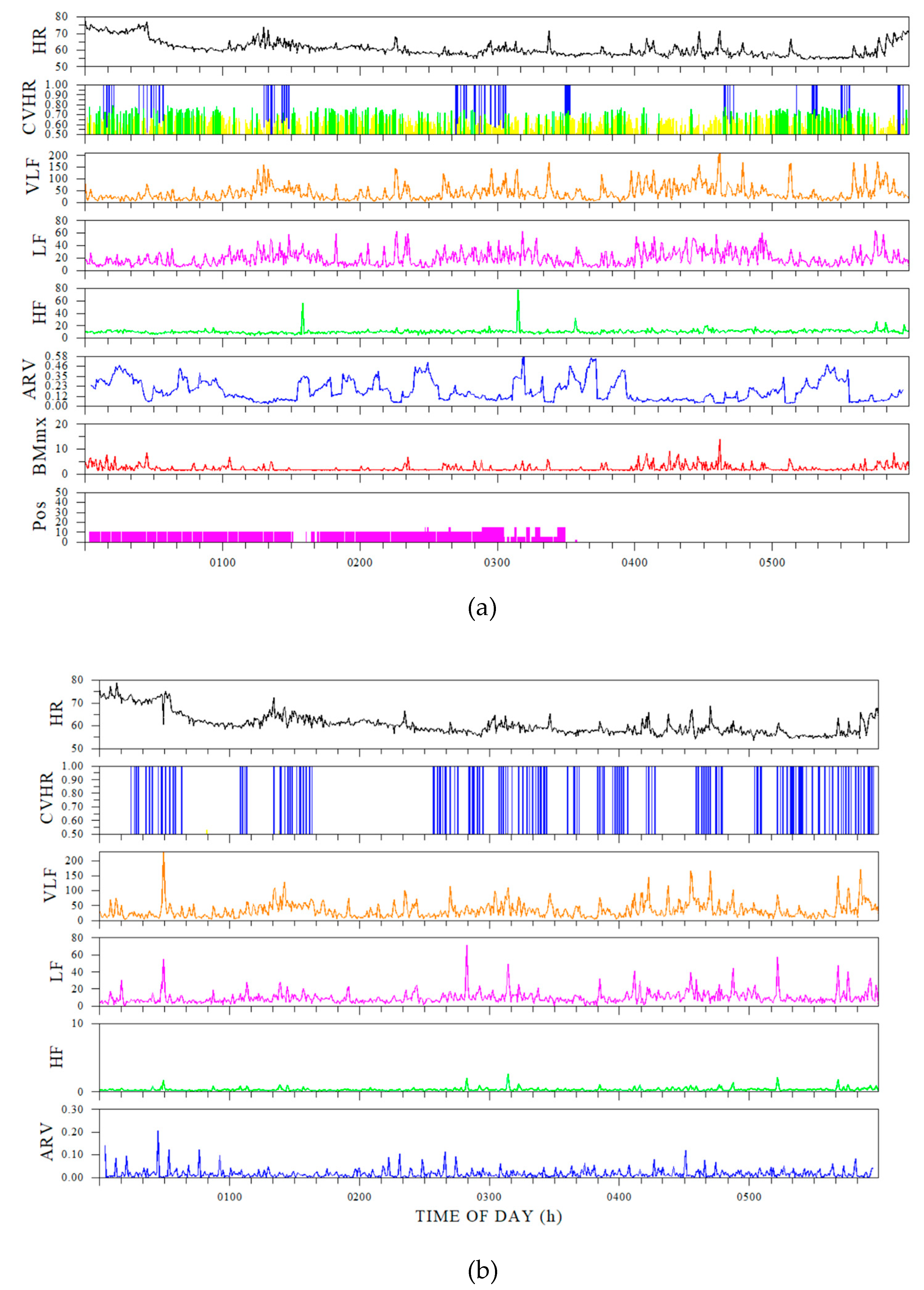

The results of comparing CVHR values between the Holter ECG and the ring-type sensor showed a correlation between the measurements of the two, and a certain degree of consistency with the Holter ECG data was confirmed. However, the ring sensor showed higher CBHR values, and it was found that correction was necessary to improve accuracy (

Table 1,

Figure 2).

Comparison of Holter electrocardiogram and ring sensor. The sampling frequency used to calculate the FCV from the ring sensor was set at 1 Hz. The explanation of each indicator is shown in

Table 2.

(a) shows sleep indices calculated from the Holter electrocardiograph, and (b) shows ring sensor indices. (a) shows, from the top down, HR (heart rate), CVHR, VLF (very low frequency component), LF (low frequency component), HF (high frequency component), ARV (heart rate variability using an autoregressive model), body movement, and posture. (b) shows HR, CVHR, VLF, LF, HF, and ARV.

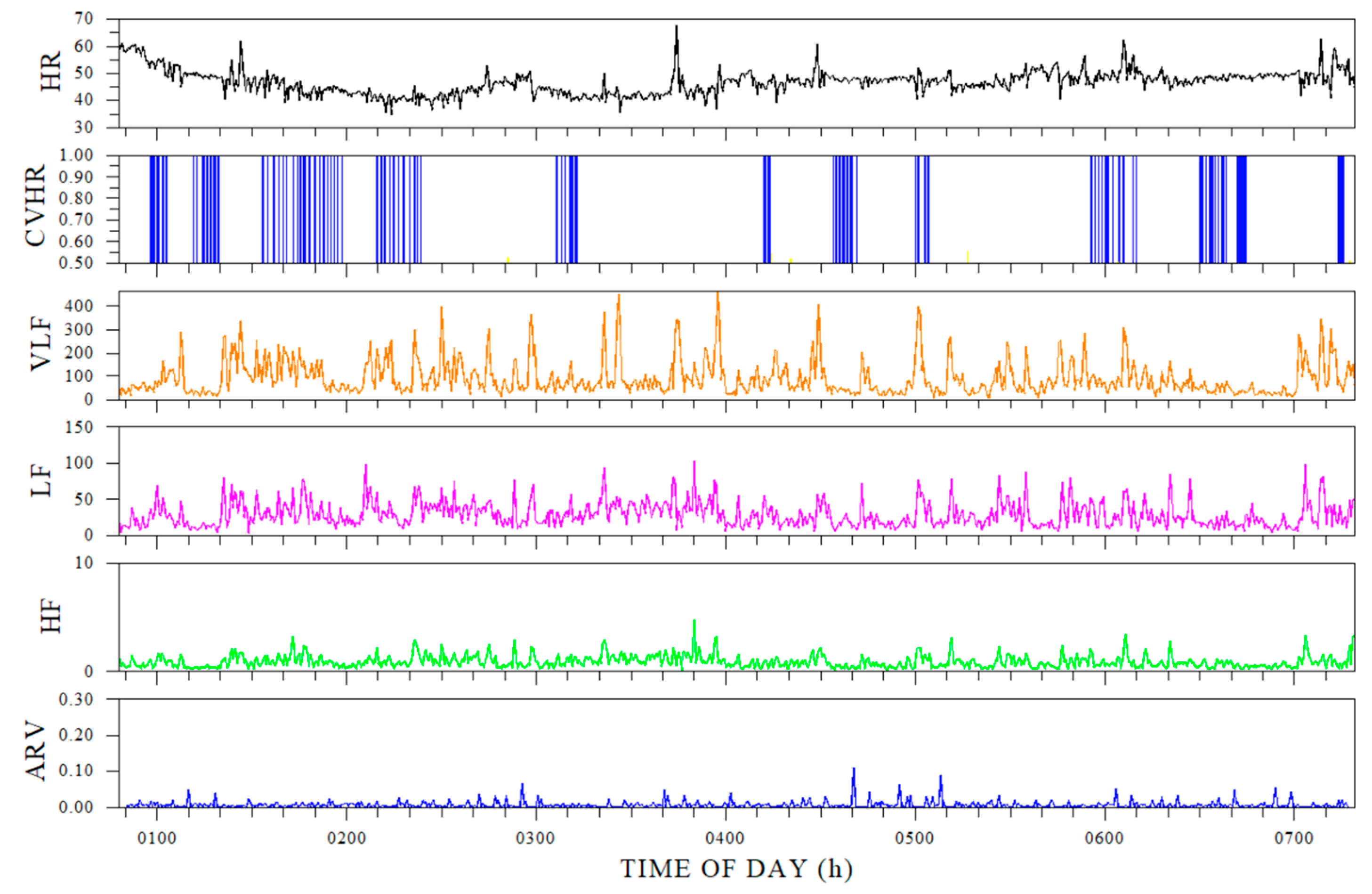

3.2. Detecting CVHR Using Ring-Type Sensor

The ring-type sensor was suitable for capturing the pattern of CVHR during sleep, but as with the results in 3.1, the overall CVHR was high (

Figure 3).

CVHR values extracted from the ring sensor tended to be calculated as high for all subjects. The average number of times per hour (CVHRI) is used as an evaluation index for CVHR. If the CVHRI is 15 or more, moderate or severe sleep apnea is suspected, and if the CVHRI exceeds 30, a sleep test is recommended [

21].

The abbreviations for the indicators are the same as in

Table 2. (There is no value for saACV.)

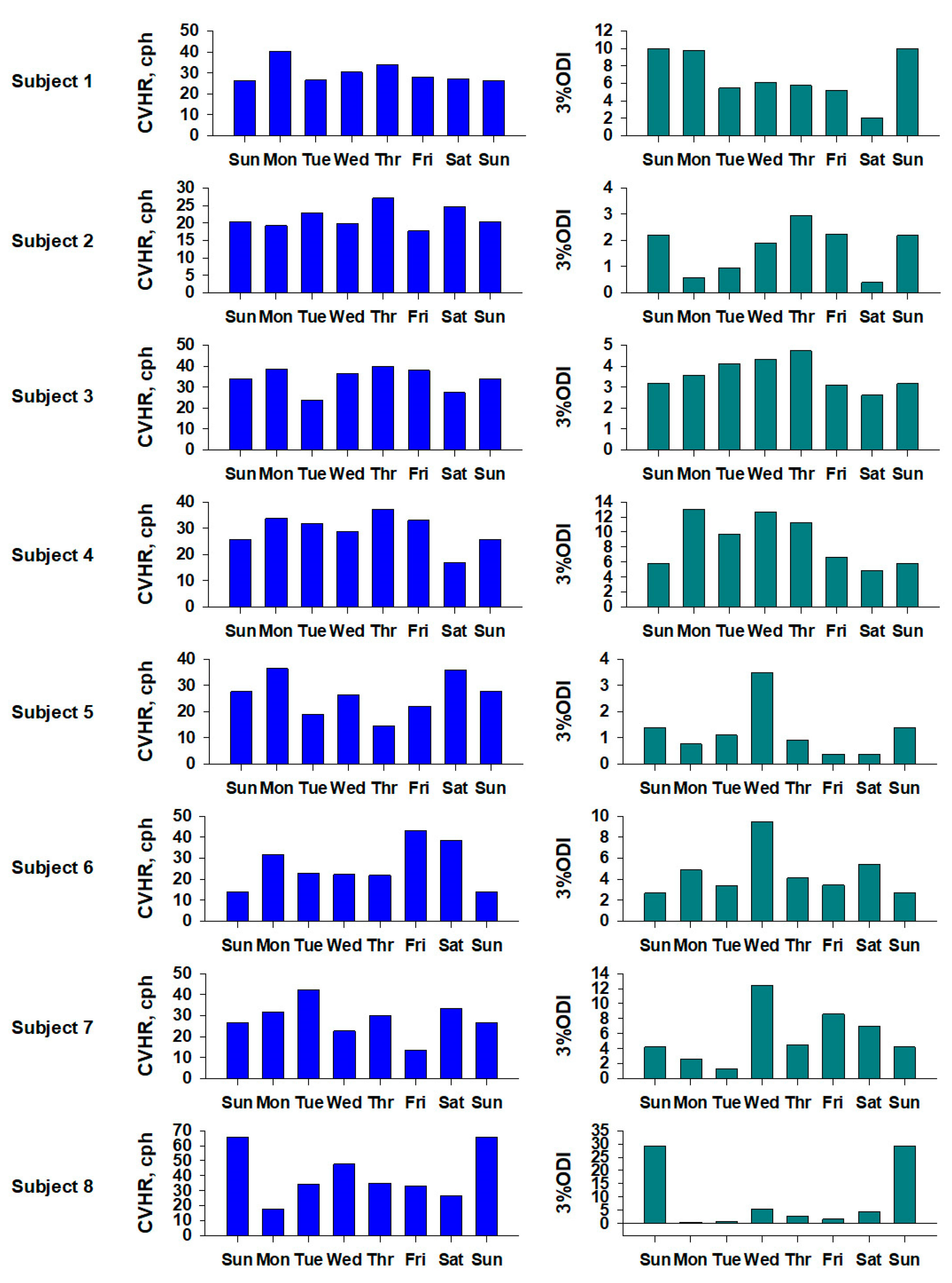

3.3. Intra-Weekly Rhythm of Measured Signals

Analysis of the measured data over the course of a week showed that the CVHR values of the subjects showed a certain degree of intra-weekly fluctuation, and in particular, patterns related to the rhythm of sleep were suggested. This indicates that CVHR monitoring using a ring-type sensor can also be applied to the evaluation of intra-weekly physiological fluctuations.

The graph shows the CVHR values (left, blue) and 3% ODI values (right, green) for the eight subjects. The horizontal axis shows the day of the week, and to make it easier to see the fluctuations by day of the week, the same data is plotted twice for the first and last Sundays.

The CVHR values tended to be higher at the weekend for subjects 5 and 8, and higher during the week for subject 6. The 3% ODI values tended to be higher at the weekend for subjects 1, 2 and 8, and higher during the week for subjects 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. As shown in

Figure 4, although there were individual differences, it was confirmed that there was a circadian rhythm within the week.

4. Discussion

The heart rate variability values obtained using a ring-type sensor were always higher than those obtained using a Holter electrocardiogram. This difference is probably due to the differences in the measurement principles and data processing algorithms of the two devices. The ring-type sensor, which relies on photoplethysmography (PPG) to detect heart rate, is susceptible to motion artifacts and fluctuations in peripheral blood flow. These factors can amplify even the slightest fluctuations, resulting in a higher CVHR value. On the other hand, Holter monitors measure the electrical signals from the heart, so the detection of R-R intervals is more accurate and stable (differences in the measurement principles of the devices). Also, if the algorithm of the ring sensor does not sufficiently smooth the data, instantaneous fluctuations will be reflected in the CVHR value as they are, resulting in a higher value (differences in data smoothing and filtering). Furthermore, there are also significant differences depending on the measurement location. As the ring sensor measures at the fingertip, it is affected by peripheral blood vessels. This effect can make the heart rate fluctuation appear larger than it actually is. On the other hand, the Holter monitor directly detects signals close to the heart, so it is not affected by peripheral factors. In this study, we compared the two under the same conditions. One possible solution is to use the Holter monitor as the gold standard and apply corrections to the ring sensor data.

The findings of this study suggest that CVHR values extracted from ring-type sensors, particularly when combined with the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) derived from SpO₂, can approximate ECG-based measurements such as those from Holter electrocardiography. Recent advances in wearable devices with high-resolution PPG sensors and improved artifact correction algorithms have shown potential for enhancing measurement accuracy. In this study, we demonstrated that even a compact, ring-shaped sensor can detect CVHR fluctuations and monitor weekly trends, although calibration remains necessary. The ability to capture weekly fluctuations is a unique contribution, shedding light on the dynamic nature of CVHR over time, a topic not well explored in prior research. However, several challenges and areas for improvement remain. First, robust calibration methods must be developed to align CVHR values from ring-type sensors with Holter ECG measurements, enhancing their clinical applicability for SAS diagnosis. Second, validation in larger and more diverse populations is needed, as this study focused on a small sample of healthy subjects. Future research should include cohorts with varying SAS severity to assess generalizability. Finally, improvements in artifact reduction and signal processing for PPG-based devices are essential to ensure accurate CVHR detection, particularly in the presence of body motion. These advancements will also support reliable long-term time-series monitoring, further increasing the utility of wearable sensors in clinical and home settings.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of using a ring-type silicone sensor to detect cyclic variation of heart rate (CVHR) during sleep and evaluate intra-weekly variability. The findings indicate that while CVHR values obtained with the ring-type sensor were higher than those measured with a Holter ECG, the device successfully detected trends and fluctuations over a week. These results suggest that ring-type sensors, with proper calibration, could serve as practical and non-invasive tools for monitoring CVHR and potentially aiding in the diagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome (SAS).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Y. and J.H.; methodology, E.Y.; software, J.H.; validation, E.Y., J.H. and H.E.; formal analysis, E.Y.; investigation, E.Y.; resources, J.H. and K.H.; data curation, E.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.H.; visualization, E.Y.; supervision, E.Y.; project administration, E.Y.; funding acquisition, E.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are publicly not available, however, it can be distributed by email to those who request it. For additional information, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all participants who contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Javaheri, S.; Barbe, F.; Campos-Rodriguez, F.; Dempsey, J.A.; Khayat, R.; Javaheri, S.; Malhotra, A.; Martinez-Garcia, M.A.; Mehra, R.; Pack, A.I.; Polotsky, V.Y.; Redline, S.; Somers, V.K. Sleep Apnea: Types, Mechanisms, and Clinical Cardiovascular Consequences. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 841–858. [CrossRef]

- Peker, Y.; Akdeniz, B.; Altay, S.; Balcan, B.; Başaran, Ö.; Baysal, E.; Çelik, A.; Dursunoğlu, D.; Dursunoğlu, N.; Fırat, S.; Gündüz Gürkan, C.; Öztürk, Ö.; Taşbakan, M.S.; Aytekin, V. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: Where Do We Stand? Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2023, 27, 375–389. [CrossRef]

- Floras, J.S. Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: An Enigmatic Risk Factor. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 1741–1764. [CrossRef]

- Seravalle, G.; Grassi, G. Sleep Apnea and Hypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2022, 29, 23–31. [CrossRef]

- Ludka, O. Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease. Cas Lek Cesk 2019, 158, 178–184.

- Drager, L.F.; McEvoy, R.D.; Barbe, F.; Lorenzi-Filho, G.; Redline, S.; INCOSACT Initiative (International Collaboration of Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Trialists). Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: Lessons From Recent Trials and Need for Team Science. Circulation 2017, 136, 1840–1850. [CrossRef]

- Klar Yaggi, H.; Concato, J.; Kernan, W.N.; Lichtman, J.H.; Brass, L.M.; Mohsenin, V. Obstructive Sleep Apnea as a Risk Factor for Stroke and Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2034–2041. [CrossRef]

- Valham, F.; Mooe, T.; Rabben, T.; Stenlund, H.; Wiklund, U.; Franklin, K.A. Increased Risk of Stroke in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease and Sleep Apnea: A 10-Year Follow-Up. Circulation 2008, 118, 955–960. [CrossRef]

- Baillieul, S.; Dekkers, M.; Brill, A.K.; Schmidt, M.H.; Detante, O.; Pépin, J.L.; Tamisier, R.; Bassetti, C.L.A. Sleep Apnoea and Ischaemic Stroke: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 78–88. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, R.F.; Lutsey, P.L.; Benveniste, H.; Brown, D.L.; Full, K.M.; Lee, J.M.; Osorio, R.S.; Pase, M.P.; Redeker, N.S.; Redline, S.; Spira, A.P.; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Hypertension. Impact of Sleep Disorders and Disturbed Sleep on Brain Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Stroke 2024, 55, e61–e76. [CrossRef]

- Khot, S.P.; Morgenstern, L.B. Sleep and Stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 1612–1617. [CrossRef]

- Culebras, A. Central Sleep Apnea May Be Central to Acute Stroke. Sleep Med. 2021, 77, 302–303. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, C.L. Sleep and Stroke. Semin. Neurol. 2005, 25, 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Abad, V.C.; Guilleminault, C. Pharmacological Treatment of Sleep Disorders and Its Relationship With Neuroplasticity. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 25, 503–53. [CrossRef]

- Lanza, G.; DelRosso, L.M.; Ferri, R. Sleep and Homeostatic Control of Plasticity. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2022, 184, 53–72. [CrossRef]

- Berryhill, S.; Morton, C.J.; Dean, A.; Berryhill, A.; Provencio-Dean, N.; Patel, S.I.; Estep, L.; Combs, D.; Mashaqi, S.; Gerald, L.B.; Krishnan, J.A.; Parthasarathy, S. Effect of Wearables on Sleep in Healthy Individuals: A Randomized Crossover Trial and Validation Study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 775–783. [CrossRef]

- Huysmans, D.; Borzée, P.; Buyse, B.; Testelmans, D.; Van Huffel, S.; Varon, C. Sleep Diagnostics for Home Monitoring of Sleep Apnea Patients. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 685766. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.B.; Uribe, L.F.S.; Cepeda, F.X.; Alquati, V.F.S.; Guimarães, J.P.S.; Silva, Y.G.A.; Santos, O.L.D.; Oliveira, A.A.; Aguiar, G.H.M.; Andersen, M.L.; Tufik, S.; Lee, W.; Li, L.T.; Penatti, O.A. Sleep Staging Algorithm Based on Smartwatch Sensors for Healthy and Sleep Apnea Populations. Sleep Med. 2024, 119, 535–548. [CrossRef]

- Hsiou, D.A.; Gao, C.; Matlock, R.C.; Scullin, M.K. Validation of a Nonwearable Device in Healthy Adults With Normal and Short Sleep Durations. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 751–757. [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Watanabe, E.; Saito, Y.; Sasaki, F.; Kawai, K.; Kodama, I.; Sakakibara, H. Diagnosis of Sleep Apnea by the Analysis of Heart Rate Variation: A Mini Review. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2011, 2011, 7731–7734. [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Watanabe, E.; Saito, Y.; Sasaki, F.; Fujimoto, K.; Nomiyama, T.; Kawai, K.; Kodama, I.; Sakakibara, H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea by cyclic variation of heart rate. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2011, 4, 64–72. [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Ueda, N.; Kisohara, M.; Yuda, E.; Watanabe, E.; Carney, R.M.; Blumenthal, J.A. Risk stratification after acute myocardial infarction by amplitude-frequency mapping of cyclic variation of heart rate. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2021, 26, e12825. [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Yasuma, F.; Watanabe, E.; Carney, R.M.; Stein, P.K.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Arsenos, P.; Gatzoulis, K.A.; Takahashi, H.; Ishii, H.; Kiyono, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Yuda, E.; Kodama, I. Blunted cyclic variation of heart rate predicts mortality risk in post-myocardial infarction, end-stage renal disease, and chronic heart failure patients. Europace 2017, 19, 1392–1400. [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Yamamoto, H.; Nonaka, I.; Komazawa, M.; Itao, K.; Ueda, N.; Tanaka, H.; Yuda, E. Quantitative detection of sleep apnea with wearable watch device. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0237279. [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Yuda, E. Night-to-night variability of sleep apnea detected by cyclic variation of heart rate during long-term continuous ECG monitoring. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022, 27, e12901. [CrossRef]

- Tobaldini, E.; Nobili, L.; Strada, S.; Casali, K.R.; Braghiroli, A.; Montano, N. Heart rate variability in normal and pathological sleep. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 294. [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, C.; Bochaton, T.; Pépin, J.L.; Belaidi, E. Obstructive sleep apnoea and cardiovascular consequences: Pathophysiological mechanisms. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 113, 350–358. [CrossRef]

- De Nys, L.; Anderson, K.; Ofosu, E.F.; Ryde, G.C.; Connelly, J.; Whittaker, A.C. The effects of physical activity on cortisol and sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 143, 105843. [CrossRef]

- Tobaldini, E.; Costantino, G.; Solbiati, M.; Cogliati, C.; Kara, T.; Nobili, L.; Montano, N. Sleep, sleep deprivation, autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular diseases. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 321–329. [CrossRef]

- Koskenvuo, M. Cardiovascular stress and sleep. Ann. Clin. Res. 1987, 19, 110–113.

- Williams, A.J.; Yu, G.; Santiago, S.; Stein, M. Screening for Sleep Apnea Using Pulse Oximetry and a Clinical Score. Chest 1991, 100(3), 631–635. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).