Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: Beyond the Continuum/Quantum Dichotomy

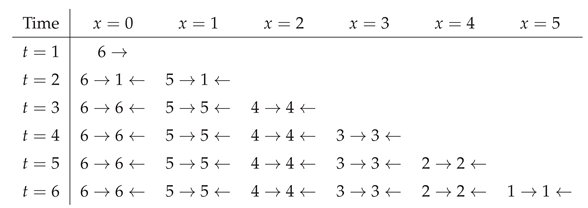

2. Architecture of the Fundamental Substrate

2.1. The Network of Coupled Oscillators

2.2. Vibrational Origin of the Network

- A node of the network corresponds to a point where the amplitude of the fundamental standing wave is minimal (a vibration node).

- A link between nodes corresponds to the region between two nodes, where the amplitude vibrates to its maximum (an antinode).

2.3. Emergence of the Quantum of Action and the Planck Scale

3. The Emergence of Matter: Non-Linearity and Self-Trapping

3.1. The Problem of Linear Dispersion

3.2. Self-Trapping and Particle Formation

- The wave’s energy density causes a local deformation of the network, increasing its energy density further in that region.

- This deformation alters the local wave speed, creating a gradient that curves the paths of the wave components back inward.

- A stable, dynamic equilibrium is reached: the wave creates the deformation that traps itself. This self-trapped, circulating wave packet is what we identify as a massive particle.

3.3. The IN/OUT Wave Mechanism: Stability and Non-Locality

- The central vibrating structure (the particle’s core) continuously emits outgoing spherical waves (OUT waves).

- These OUT waves propagate through the network. They are not lost; instead, they are continuously and partially reflected by the inhomogeneities and implicit boundaries created by other particles, distant matter, and the overall curvature of the network itself.

- The sum of all these reflections generates incoming spherical waves (IN waves) that converge back towards the source.

- At dynamic equilibrium, the IN and OUT waves interfere constructively to perpetually reconstruct and reinforce the stable standing wave pattern that is the particle. The particle’s energy is maintained through this continuous feedback loop.

- The remarkable stability of this structure arises because the partial reflection mechanism, though its efficiency (and thus the wave amplitude) may vary along the path, ensures that the IN and OUT waves share the same frequency and maintain equal amplitude at every point in space where the standing wave is established. This precise balance is what defines and maintains the stationary state of the particle across its entire non-local structure.

- The energy radiated outward equals the energy reflected back inward

- The constructive interference at the core perpetually reconstructs the particle

- The system reaches a dynamic equilibrium where no net energy is lost

4. The Particle in Motion: Internal Geometry and Dynamic Inertia

4.1. The Internal State of a Particle: More Than a Point

4.2. Velocity as a Deformation of the Internal Configuration

4.3. Inertia as the Energetic Cost of Reconfiguration

- To accelerate a particle (to change ) is to force it to change its internal deformation state.

- Transitioning from one internal configuration (corresponding to ) to another (corresponding to ) requires modifying the amplitudes and phases of oscillations along the three spatial axes. This reconfiguration work must occur in parallel with the internal circulations that define the particle.

- This reconfiguration requires work against the elastic restoring forces of the network that "lock" the particle into its current vibrational state. The network’s "springs" resist this dynamic deformation.

5. Synthesis: Emergence of the Dual Concept of Mass

5.1. The Fundamental Reality: Deformation and Its Dynamics

5.2. The Dual Emergence of "Mass"

- Inertial Mass (): This is the measure of the resistance to internal reconfiguration. It emerges directly from the rigidity k of the network. Its origin is dynamic and local (related to the internal structure of the particle).

- Gravitational Mass (): This is the measure of the intensity of the static environmental deformation that the particle imprints on the network via its extended IN/OUT wave field. Its origin is static and non-local.

5.3. The Proportionality Between Gravitational and Inertial Mass and the Role of G

6. The Emergence of General Relativity

6.1. Gravity as a Refractive Effect

6.2. From Refraction to Curvature

6.3. Metric from Network Configuration

- The spatial components relate to the actual physical deformation of the network links from their equilibrium positions.

- The temporal component relates to the local effective wave speed v, and thus to the energy density deformation.

- The off-diagonal components could emerge from shearing deformations or persistent flow patterns in the network.

7. Implications and Reinterpretations of Quantum Phenomena

7.1. Violation of Bell’s Inequalities and Entanglement

7.2. Holographic Principle

- The information about the internal state of a volume V is carried by the vibrations of its nodes and the waves passing through it.

- The OUT waves leaving volume V through its surface carry with them the complete information about the interior they traversed.

- The IN waves entering volume V are, by definition, the OUT waves from other regions that have been reflected or modified. They "bring" information from the outside.

8. Conclusion and Perspectives

- Mass as elastic deformation energy.

- Spacetime curvature and General Relativity as emergent properties of the network’s dynamics and variable effective refractive index.

- Non-locality and entanglement as consequences of the extended IN/OUT wave mechanism.

- The Holographic Principle as a dynamic property of vibrational information propagation.

- The distinction and proportionality between inertial and gravitational mass.

- The formal emergence of the Planck scale and the quantum of action ℏ from the elastic properties of the spacetime network.

8.1. The Research Program

- Reinterpretation of foundational experiments: Detailed analysis showing that the Michelson-Morley experiment does not preclude a physical propagation medium, and that Special Relativity is an essential observational theory for relative velocity calculations.

- Quantum foundations: Complete derivation of quantum mechanics from the substrate dynamics, including wavefunction collapse and quantum superposition.

- Particle modeling: Conceptualization and detailed description of electrons, protons, and neutrons as specific stable configurations of IN/OUT waves within the spatial network. This framework provides mechanical explanations for their stability, mass ratios, and quantum properties.

- Astrophysical and cosmological implications: Explanations for dark matter, dark energy, the Big Bang, and quark confinement as emergent phenomena.

- Standard model emergence: Derivation of the complete particle spectrum and gauge interactions from vibrational modes of the network.

8.2. Computational Approach and Future Directions

- Observing the spontaneous emergence of physical laws from network dynamics

- Identifying the specific conditions for particle creation at various energy scales

- Verifying the derivation of General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics as limiting cases

- Exploring novel phenomena at the intersection of quantum and gravitational regimes

Appendix A. Energy Confinement Mechanism

References

- A. D. Sakharov. Vacuum quantum fluctuations in curved space and the theory of gravitation. Sov. Phys. Dokl., 12:1040–1041, 1968.

- J. D. Bekenstein. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D, 7:2333–2346, 1973.

- G. ’t Hooft. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. In A. Ali, J. Ellis, and S. Randjbar-Daemi, editors, Salamfestschrift, volume 4, pages 284–296. World Scientific, 1993. arXiv:gr-qc/9310026.

- T. Padmanabhan. Thermodynamical aspects of gravity: new insights. Rep. Prog. Phys., 73(4):046901, 2010. arXiv:0911.5004 [gr-qc].

- G. E. Volovik. The Universe in a Helium Droplet. International Series of Monographs on Physics. Oxford University Press, 2003. 2003.

- B.-L. Hu. Can spacetime be a condensate? Int. J. Theor. Phys., 44:1785–1806, 2005. arXiv:gr-qc/0503067.

- T. Jacobson. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett., 75:1260–1263, 1995. arXiv:gr-qc/9504004.

- S. Lloyd. Ultimate physical limits to computation. Nature, 406:1047–1054, 2000. arXiv:quant-ph/9908043.

- G. Furne Gouveia. The IN/OUT Wave Mechanism: A Non-Local Foundation for Quantum Behavior and the Double-Slit Experiment. Preprints 2025, 2025090184. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).