Submitted:

31 August 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. RRBS Identified Altered DNA Methylation in RPE of 1-Month Abca4-/- Mice

2.2. Transcription Factors Associated with Hypermethylated DMC-Promoters in Abca4-/- Mice RPE at 1-Month of Age

2.3. RNA-seq Analysis Identified Transcriptional Changes in RPE from 1-Month-Old Abca4-/- Mice Compared to Age-Matched Wild-Type Controls

2.4. DNA Methylation Enriched Pathways in 3-Month-Old Abca4-/- Mice RPE Cells

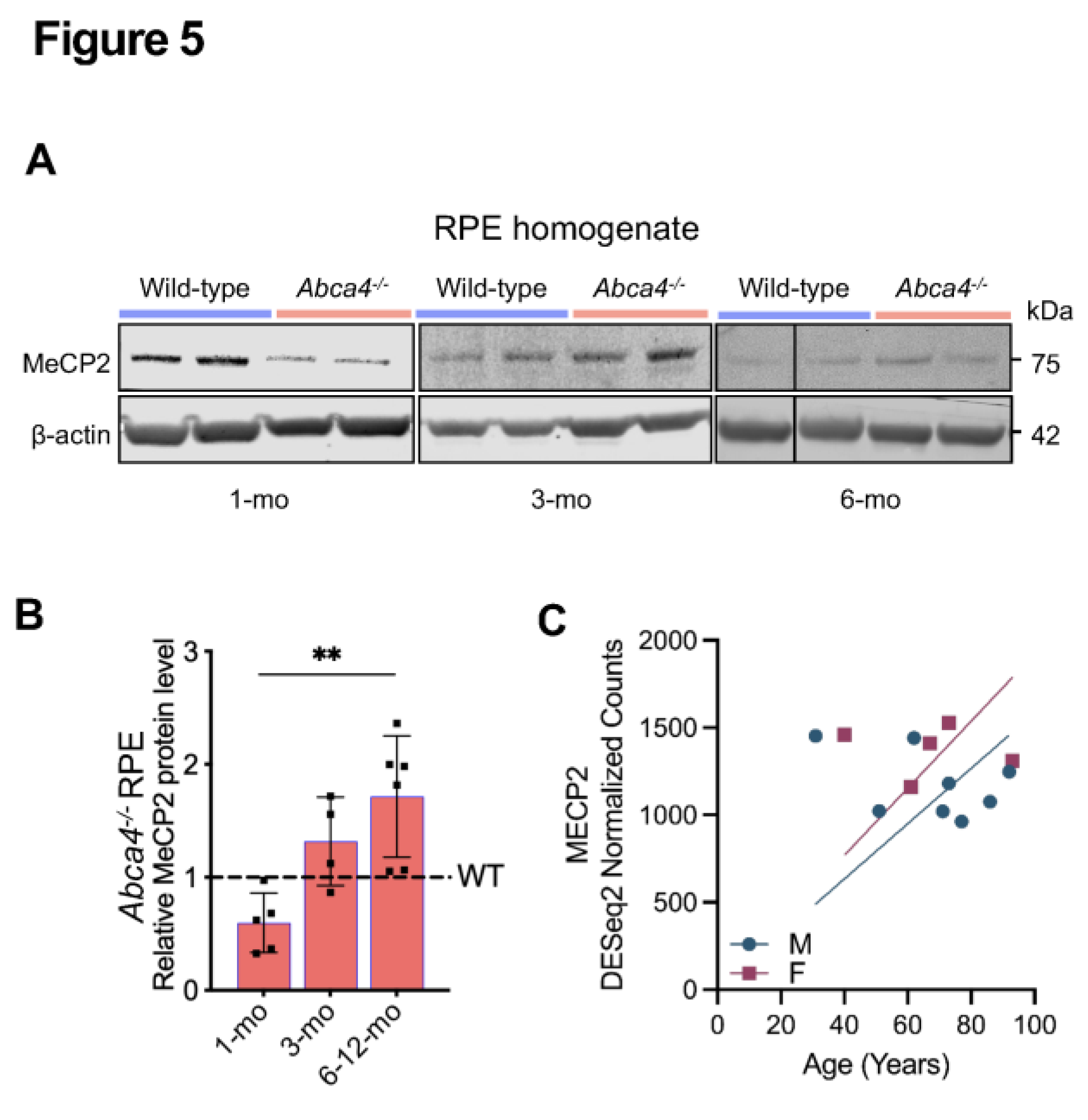

2.5. Age-Dependent Increase of MeCP2 Protein in Abca4-/- Mice RPE and in Human RPE

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Mice

Collection of RPE/Eyecup

DNA Extraction and Quantification

Library Preparation and Reduced Representation Bisulphite Sequencing (RRBS)

Data Analysis

RNA Sequencing Data Set Enrichment Analysis

Immunoblotting

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STGD1 | Recessive Stargardt disease |

| AMD | Age-related macular degeneration |

| RRBS | Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing |

| DMC | Differentially methylated CpGs |

References

- Strauss, R.W.; et al. The natural history of the progression of atrophy secondary to Stargardt disease (ProgStar) studies: design and baseline characteristics: ProgStar Report No. 1. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; et al. Differential disease progression in atrophic age-related macular degeneration and late-onset Stargardt disease. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2017, 58, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan, A.V.; et al. Mutations in ABCA4 result in accumulation of lipofuscin before slowing of the retinoid cycle: a reappraisal of the human disease sequence. Human molecular genetics 2004, 13, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabduljalil, T.; et al. Correlation of outer retinal degeneration and choriocapillaris loss in Stargardt disease using en face optical coherence tomography and optical coherence tomography angiography. American journal of ophthalmology 2019, 202, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allikmets, R.; et al. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Starqardt macular dystrophy. Nature genetics 1997, 15, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCBI, ClinVar search results for ABCA4 gene in Stargardt disease. National Center for Biotechnology Information, n.d.

- Sun, H. and J. Nathans, Stargardt's ABCR is localized to the disc membrane of retinal rod outer segments. Nature genetics 1997, 17, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illing, M.; L. L. Molday, and R.S. Molday, The 220-kDa rim protein of retinal rod outer segments is a member of the ABC transporter superfamily. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 10303–10310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenis, T.L.; et al. Expression of ABCA4 in the retinal pigment epithelium and its implications for Stargardt macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, E11120–E11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matynia, A.; et al. Assessing Variant Causality and Severity Using Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Derived from Stargardt Disease Patients. Translational vision science & technology 2022, 11, 33–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, E.S.Y.; et al. Membrane Attack Complex Mediates Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cell Death in Stargardt Macular Degeneration. Cells 2022, 11, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnoodian, M.; et al. Cell-autonomous lipid-handling defects in Stargardt iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelium cells. Stem Cell Reports 2022, 17, 2438–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molday, L.L.; A. R. Rabin, and R.S. Molday, ABCR expression in foveal cone photoreceptors and its role in Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nature genetics 2000, 25, 257–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, N.L.; J. Weng, and G.H. Travis, Biosynthesis of a major lipofuscin fluorophore in mice and humans with ABCR-mediated retinal and macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, 7154–7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; et al. Insights into the function of Rim protein in photoreceptors and etiology of Stargardt's disease from the phenotype in abcr knockout mice. Cell 1999, 98, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; et al. A vicious cycle of bisretinoid formation and oxidation relevant to recessive Stargardt disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2021, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.S.Y.; et al. Impaired cathepsin D in retinal pigment epithelium cells mediates Stargardt disease pathogenesis. The FASEB Journal 2024, 38, e23720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, R.A.; et al. Complement system dysregulation and inflammation in the retinal pigment epithelium of a mouse model for Stargardt macular degeneration. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 18593–18601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A.M. and A. Bird, CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes & development 2011, 25, 1010–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, A. Functions for DNA methylation in vertebrates. in Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 1993. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Dhar, G.A.; et al. DNA methylation and regulation of gene expression: Guardian of our health. The Nucleus 2021, 64, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.D.; T. Le, and G. Fan, DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso-Díaz, X.; et al. Epigenetic control of gene regulation during development and disease: A view from the retina. Progress in retinal and eye research 2018, 65, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, A.; et al. DNA recognition by the methyl-CpG binding domain of MeCP2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 3353–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, R.E.; et al. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nature genetics 1999, 23, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, R.; J. D. Lewis, and A.P. Bird, Characterization of MeCP2, a vertebrate DNA binding protein with affinity for methylated DNA. Nucleic acids research 1992, 20, 5085–5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahrour, M.; et al. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science 2008, 320, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shachar, S.; et al. Mouse models of MeCP2 disorders share gene expression changes in the cerebellum and hypothalamus. Human molecular genetics 2009, 18, 2431–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; et al. Involvement of MeCP2 in regulation of myelin-related gene expression in cultured rat oligodendrocytes. Journal of molecular neuroscience 2015, 57, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-L.; et al. Regulation of mRNA splicing by MeCP2 via epigenetic modifications in the brain. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 42790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks, F.; et al. The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 links DNA methylation to histone methylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 4035–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.L.; et al. Mild overexpression of MeCP2 causes a progressive neurological disorder in mice. Human molecular genetics 2004, 13, 2679–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, I. ; The development of the human eye. 1928: The University Press.

- Song, C.; et al. DNA methylation reader MECP2: cell type-and differentiation stage-specific protein distribution. Epigenetics & chromatin 2014, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; et al. MeCP2-421-mediated RPE epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its relevance to the pathogenesis of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2020, 24, 9420–9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Critical role of apoptosis in MeCP2-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition of ARPE-19 cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2024, 239, e31429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; et al. MeCP2-Induced Alternations of Transcript Levels and m6A Methylation in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cells. ACS omega 2023, 8, 47964–47973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; et al. A role for βA3/A1-crystallin in type 2 EMT of RPE cells occurring in dry age-related macular degeneration. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2018, 59, AMD104–AMD113. [Google Scholar]

- Frasca, A.; et al. MECP2 mutations affect ciliogenesis: a novel perspective for Rett syndrome and related disorders. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2020, 12, e10270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; J. Zhou, and X. Meng, Primary cilia in retinal pigment epithelium development and diseases. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2021, 25, 9084–9088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, P.C.; et al. Fundus autofluorescence in the Abca4−/− mouse model of Stargardt disease—correlation with accumulation of A2E, retinal function, and histology. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2013, 54, 5602–5612. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, R.A.; et al. Accelerated accumulation of lipofuscin pigments in the RPE of a mouse model for ABCA4-mediated retinal dystrophies following Vitamin A supplementation. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2008, 49, 3821–3829. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Siyu Liu, Laurie K. Svoboda, Christine A. Rygiel, Kari Neier, Tamara R. Jones, Justin A. Colacino, Dana C. Dolinoy, and Maureen A. Sartor., Tissue-and sex-specific DNA methylation changes in mice perinatally exposed to lead (Pb). Frontiers in genetics 2020, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H. and X. Sun, Contribution of interleukin-17A to retinal degenerative diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 847937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesseur, I. and T. Wyss-Coray, A role for TGF-β signaling in neurodegeneration: evidence from genetically engineered models. Current Alzheimer Research 2006, 3, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marambaud, P.; U. Dreses-Werringloer, and V. Vingtdeux, Calcium signaling in neurodegeneration. Molecular neurodegeneration 2009, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Vargas, J.A.; et al. Neurodegeneration and convergent factors contributing to the deterioration of the cytoskeleton in Alzheimer's disease, cerebral ischemia and multiple sclerosis. Biomedical Reports 2022, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionaki, E.; C. Ploumi, and N. Tavernarakis, One-carbon metabolism: pulling the strings behind aging and neurodegeneration. Cells 2022, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Espinal, M.; et al. Blocking IL-6 signaling prevents astrocyte-induced neurodegeneration in an iPSC-based model of Parkinson’s disease. JCI insight 2024, 9, e163359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, A.B.; et al. ChEA3: transcription factor enrichment analysis by orthogonal omics integration. Nucleic acids research, 2019. 47(W1): p. W212-W224.

- Tsutsui, H.; et al. The DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of MAZ, a myc-associated zinc finger protein, are regulated by casein kinase II. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 1999, 262, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, C.J. and P.J. Farnham, Context-dependent transcriptional regulation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 29583–29586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, J.; et al. The CCAAT/enhancer (C/EBP) family of basic-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors is a multifaceted highly-regulated system for gene regulation. Cytokine 2011, 54, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; K. Zhao, and M.F. Mehler, Profiling RE1/REST-mediated histone modifications in the human genome. Genome biology 2009, 10, R9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; et al. CTCF functions as an insulator for somatic genes and a chromatin remodeler for pluripotency genes during reprogramming. Cell Reports 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, N.; et al. Stroke causes DNA methylation at Ncx1 heart promoter in the brain via DNMT1/MeCP2/REST epigenetic complex. Journal of the American Heart Association 2024, 13, e030460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballas, N. and G. Mandel, The many faces of REST oversee epigenetic programming of neuronal genes. Current opinion in neurobiology 2005, 15, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Barrios, A.; et al. Dysregulated lipid metabolism in a retinal pigment epithelial cell model and serum of patients with age-related macular degeneration. BMC biology 2025, 23, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, E.A. and V.A. Wallace, Cell fate determination in the vertebrate retina. Trends in neurosciences 2012, 35, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; S. He, and M. Zhao, An Updated Review of the Epigenetic Mechanism Underlying the Pathogenesis of Age-related Macular Degeneration. Aging and disease 2020, 11, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.A.; et al. Anti-VEGF Drugs Influence Epigenetic Regulation and AMD-Specific Molecular Markers in ARPE-19 Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemenetzi, M. and A. Lotery, The role of epigenetics in age-related macular degeneration. Eye 2014, 28, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.I. and J. Bayry, A role for IL-17 in age-related macular degeneration. Nature Reviews Immunology 2013, 13, 701–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; et al. Hypomethylation of the IL17RC promoter associates with age-related macular degeneration. Cell reports 2012, 2, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, A.; et al. DNA methylation is associated with altered gene expression in AMD. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2012, 53, 2089–2105. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, L.F.; et al. Whole-genome methylation profiling of the retinal pigment epithelium of individuals with age-related macular degeneration reveals differential methylation of the SKI, GTF2H4, and TNXB genes. Clinical epigenetics 2019, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso-Díaz, X.; et al. Genome-wide profiling identifies DNA methylation signatures of aging in rod photoreceptors associated with alterations in energy metabolism. Cell reports 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Integrated analysis of DNA methylation and RNA transcriptome during in vitro differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into retinal pigment epithelial cells. PLoS One 2014, 9, e91416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvoriantchikova, G.; R. J. Seemungal, and D. Ivanov, The epigenetic basis for the impaired ability of adult murine retinal pigment epithelium cells to regenerate retinal tissue. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z. and Y. Liu, DNA methylation in human diseases. Genes & diseases 2018, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Suuronen, T.; et al. Epigenetic regulation of clusterin/apolipoprotein J expression in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2007, 357, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco, L.D.; et al. A systems biology approach uncovers novel disease mechanisms in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Genomics 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbel Issa, P.; et al. Rescue of the Stargardt phenotype in Abca4 knockout mice through inhibition of vitamin A dimerization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 8415–8420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, P.L.; et al. Monoallelic ABCA4 mutations appear insufficient to cause retinopathy: a quantitative autofluorescence study. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2015, 56, 8179–8186. [Google Scholar]

- Gemenetzi, M. and A. Lotery, Epigenetics in age-related macular degeneration: new discoveries and future perspectives. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2020, 77, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.; and S., A. Freeman Phagocytosis by the Retinal Pigment Epithelium: Recognition, Resolution, Recycling. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 604205–604205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seven new loci associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nature genetics 2013, 45, 433–439. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; et al. Evidence of complement dysregulation in outer retina of Stargardt disease donor eyes. Redox biology 2020, 37, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballas, N.; et al. REST and its corepressors mediate plasticity of neuronal gene chromatin throughout neurogenesis. Cell 2005, 121, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.M.; et al. NRSF–mediated repression of neuronal genes in developing brain persists in the absence of NRSF-Sin3 interaction. bioRxiv, 2018: p. 245993.

- Perera, A.; et al. TET3 is recruited by REST for context-specific hydroxymethylation and induction of gene expression. Cell reports 2015, 11, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. REST, regulated by RA through miR-29a and the proteasome pathway, plays a crucial role in RPC proliferation and differentiation. Cell Death & Disease 2018, 9, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera A, E.D. ; Wagner M, Laube SK, Künzel AF, Koch S, Steinbacher J, Schulze E, Splith V, Mittermeier N, Müller M, TET3 is recruited by REST for context-specific hydroxymethylation and induction of gene expression. Cell reports 2015, 11, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, R.A.; et al. Light exposure stimulates formation of A2E oxiranes in a mouse model of Stargardt's macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 5928–5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, C.; et al. BiSulfite Bolt: A bisulfite sequencing analysis platform. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; et al. RnBeads 2.0: comprehensive analysis of DNA methylation data. Genome biology 2019, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic acids research 2015, 43, e47–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcante, R.G. and M.A. Sartor, Annotatr: genomic regions in context. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2381–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Exploring epigenomic datasets by ChIPseeker. Current protocols 2022, 2, e585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; et al. Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nature protocols 2024, 19, 3292–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nature communications 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; et al. Protein misfolding and the pathogenesis of ABCA4-associated retinal degenerations. Human molecular genetics 2015, 24, 3220–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).