Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

The Foundational Question: One True Effect?

- In this setting, a fixed-effect model would be appropriate: it assumes there is a single universal true value for g (approximately 9.81 m/s2), and that any variation between experimental estimates arises solely from measurement error (i.e., sampling error). The goal of the meta-analysis would be to obtain the most precise possible estimate of this single underlying constant.

- Now compare this with a clinical example: estimating the average systolic blood pressure (SBP) of adults in different cities. Here, a random-effects model is more appropriate. We do not assume that all cities share the same true SBP. Instead, we assume that each city has its own true mean SBP, and that these values are drawn from a broader distribution shaped by demographic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. The aim of a random-effects meta-analysis, therefore, is not to estimate a single fixed constant, but to estimate the mean of this distribution and quantify how much the true effects vary across settings (the between-study variance, τ2).

Fixed-Effect: Clarity with a Cost

Random-Effects: Embracing Variability

Heterogeneity as the Compass for Model Choice

What Heterogeneity Means

Clinical vs. Statistical Heterogeneity

- Clinical heterogeneity: real-world variability in who was studied, what was done, or where it was done. These differences are not “errors” but reflections of normal clinical diversity (e.g., different patient profiles, dosages, techniques, or healthcare settings).

- Statistical heterogeneity: heterogeneity “put into numbers.” It describes how much the study estimates differ after accounting for sampling error (i.e., the random imprecision that arises simply because each study observes only a finite sample of patients). Indices like Q, I2, and τ2 express this variance quantitatively.

Quantifying and Interpreting Heterogeneity

- Cochran’s Q: a χ2 (chi-squared) test of the null hypothesis that all studies estimate the same true effect [4]. It checks whether observed dispersion exceeds what would be expected by chance. Q has low power with few studies and excessive sensitivity with many; therefore, a non-significant Q should never be interpreted as evidence of homogeneity.

- I2: the percentage of total variation explained by real heterogeneity rather than chance [2,5,6]. Values of 25%, 50%, and 75% are often quoted as low, moderate, and high, but these thresholds are arbitrary and context-dependent. I2 is only an estimate and can be unstable with few studies, and because it depends on study precision, large datasets can yield high I2 even when absolute differences are clinically trivial. For this reason, I2 should be interpreted descriptively and should not dictate model choice.

- τ2 (between-study variance): an absolute measure of how much true effects differ across studies, expressed on the same scale as the effect size [2,7,8]. A τ2 close to zero indicates minimal dispersion of true effects; larger τ2 values indicate meaningful underlying variability. τ2 drives the weights in random-effects models and determines the width of confidence and prediction intervals. However, it quantifies heterogeneity — it does not explain its sources. Explaining heterogeneity requires further investigation (e.g., subgroup analysis or meta-regression).

Choosing an Estimator for τ2

- DerSimonian–Laird (DL): the traditional, non-iterative estimator derived from Cochran’s Q statistic [10]. Although historically common and still the default in older software, numerous simulation studies have shown that DL is often negatively biased, systematically underestimating the true between-study variance τ2, especially when the number of studies is small or when events are rare. This underestimation leads to overly narrow confidence intervals and an inflated Type I error rate.

- Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML): an iterative estimator that is generally more robust. Simulation studies consistently demonstrate that REML yields a less biased estimate of τ2 across a wide range of realistic meta-analytic scenarios compared with DL. For this reason, it is now recommended as the default option in many methodological guidelines, including the Cochrane Handbook.

- Paule–Mandel (PM): another robust iterative estimator that frequently performs similarly to REML. PM is also considered a superior alternative to DL and is likewise endorsed by Cochrane as an appropriate default when heterogeneity is expected.

Calculating Confidence Intervals (“the CI”)

- Wald CI: the traditional, straightforward approach; it often produces intervals that look reassuringly precise but can be too narrow, especially when there are few studies or some heterogeneity [2].

- Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman (HKSJ): a modern method that produces wider and generally more reliable intervals. It is now considered the standard when heterogeneity is present. With very few studies, it can sometimes yield excessively wide (over-conservative) intervals; however, it remains the better option overall, as cautious inference is safer than overconfident conclusions [11,12].

- Modified or truncated HKSJ (mHK): a refinement of the HKSJ method, designed to prevent confidence intervals from becoming excessively wide in rare situations—typically when the number of studies is very small, a common scenario in clinical research, or when the between-study variance is close to zero [13].

Model Choice Should Come First (and I2 Should Not Be Used to Make This Choice)

Putting It Together

So, Which Model Should I Choose?

Key Principles for Model Choice

What Cochrane Recommends

Practical Guidance for Clinicians

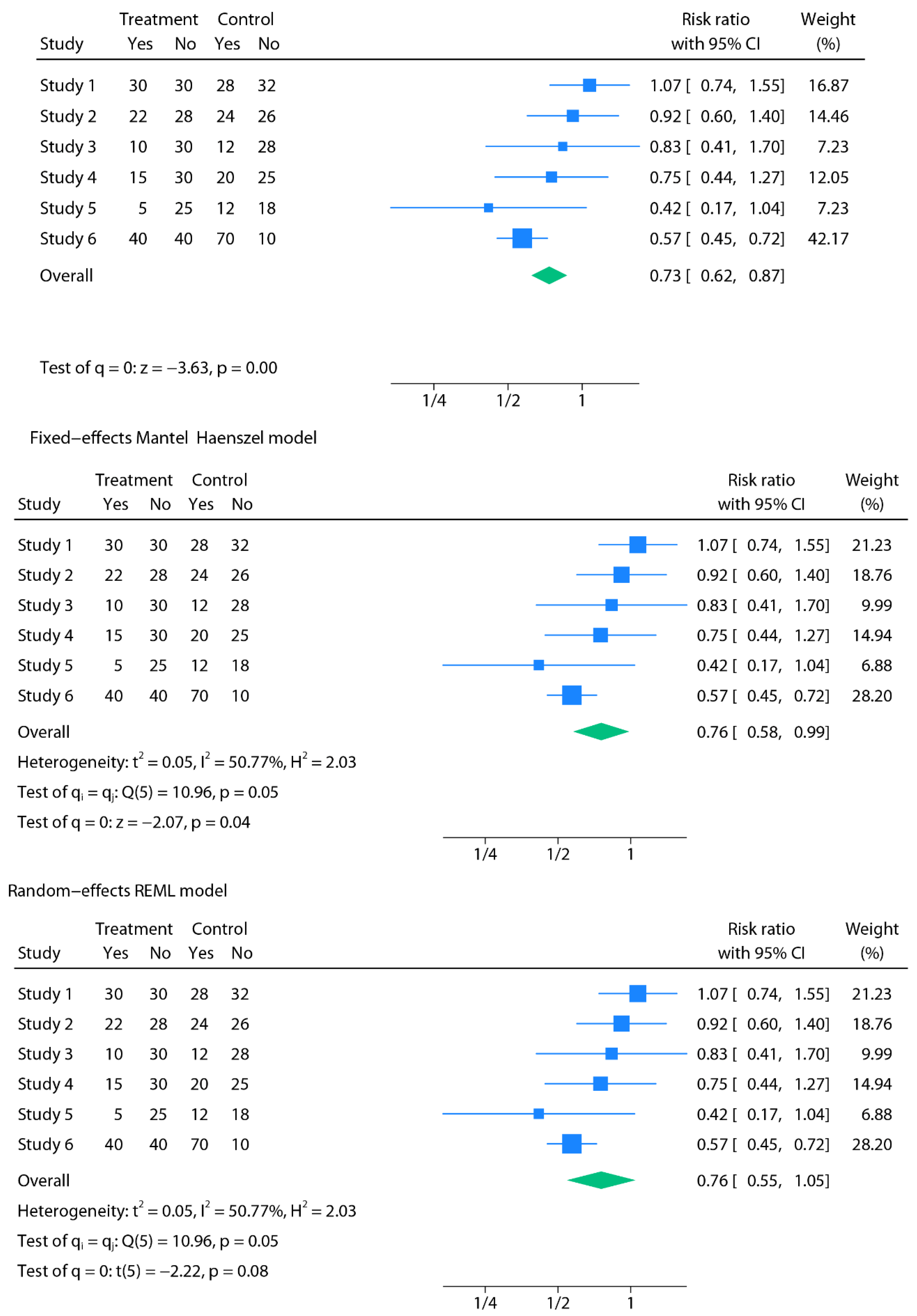

Making It Visual: Fixed vs Random at a Glance

How to Report a Meta-Analysis

Methods

Results

A Practical Workflow for Performing a Meta-Analysis

Step 1 — Define and Extract the Effect Size

Step 2 — Specify the Modelling Framework

Step 3 — Choose How Between-Study Heterogeneity Is Estimated

Step 4 — Choose How Uncertainty Is Quantified

Step 5 — Interpret Heterogeneity

Step 6 — Report Generalizability via Prediction Intervals

Step 7 — Sensitivity and Transparency

- which modelling framework was used (fixed vs random-effects),

- which τ2 estimator was applied (e.g., REML or Paule–Mandel),

- which CI method was used (e.g., Hartung–Knapp),

- and whether continuity corrections or other analytical adjustments were required.

Real-World Case Studies: How Fixed vs Random-Effects Alter Conclusions

Applied Case Study 1: Urination Stimulation Techniques in Infants

Applied Case Study 2: Musculoskeletal Outcomes After Esophageal Atresia Repair

Applied Case Study 3: Re-Analysis of Psychological Bulletin Meta-Analyses

Applied Case Study 4: the Rosiglitazone Link with Myocardial Infarction and Cardiac Death

Applied Case Study 5: The Role of Magnesium in Acute Myocardial Infarction

A Final Nuance: Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Riley RD, Gates S, Neilson J, Alfirevic Z. Statistical methods can be improved within Cochrane pregnancy and childbirth reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 Jun;64(6):608-18. Epub 2010 Dec 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds.). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6.5 (updated March 2023). Cochrane, 2023.

- Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549.

- Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101–29.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

- Viechtbauer, W. (2005). Bias and Efficiency of Meta-Analytic Variance Estimators in the Random-Effects Model. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 30(3), 261-293 (Original work published 2005). [CrossRef]

- Veroniki AA, Jackson D, Viechtbauer W, Bender R, Bowden J, Knapp G, Kuss O, Higgins JP, Langan D, Salanti G. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2016 Mar;7(1):55-79. Epub 2015 Sep 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arredondo Montero, J. Understanding Heterogeneity in Meta-Analysis: A Structured Methodological Tutorial. Preprints 2025, 2025081527. [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

- IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:25.

- Hartung J, Knapp G. A refined method for the meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with binary outcome. Stat Med. 2001 Dec 30;20(24):3875-89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röver C, Knapp G, Friede T. Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman approach and its modification for random-effects meta-analysis with few studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015 Nov 14;15:99. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Rovers MM, Goeman JJ. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016 Jul 12;6(7):e010247. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nagashima K, Noma H, Furukawa TA. Prediction intervals for random-effects meta-analysis: A confidence distribution approach. Stat Methods Med Res. 2019 Jun;28(6):1689-1702. Epub 2018 May 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ, Rohe MS, Buroh S, Schwarzer G, Becker G. Reevaluation of statistically significant meta-analyses in advanced cancer patients using the Hartung-Knapp method and prediction intervals-A methodological study. Res Synth Methods. 2022 May;13(3):330-341. Epub 2022 Jan 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372:n71. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- M. Molina-Madueño, S. Rodríguez-Cañamero, and J. M. Carmona-Torres, “Urination Stimulation Techniques for Collecting Clean Urine Samples in Infants Under One Year: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Acta Paediatrica (2025). [CrossRef]

- Arredondo Montero J. Meta-Analytical Choices Matter: How a Significant Result Becomes Non-Significant Under Appropriate Modelling. Acta Paediatr. 2025 Jul 28. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizoglu M, Perez Bertolez S, Kamci TO, Arslan S, Okur MH, Escolino M, Esposito C, Erdem Sit T, Karakas E, Mutanen A, Muensterer O, Lacher M. Musculoskeletal outcomes following thoracoscopic versus conventional open repair of esophageal atresia: A systematic review and meta-analysis from pediatric surgery meta-analysis (PESMA) study group. J Pediatr Surg. 2025 Jun 27;60(9):162431. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arredondo Montero J. Letter to the editor: Rethinking the use of fixed-effect models in pediatric surgery meta-analyses. J Pediatr Surg. 2025 Aug 8:162509. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt FL, Oh IS, Hayes TL. Fixed- versus random-effects models in meta-analysis: model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in results. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2009 Feb;62(Pt 1):97-128. Epub 2007 Nov 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuster JJ, Jones LS, Salmon DA. Fixed vs random effects meta-analysis in rare event studies: the rosiglitazone link with myocardial infarction and cardiac death. Stat Med. 2007 Oct 30;26(24):4375-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods KL, Abrams K. The importance of effect mechanism in the design and interpretation of clinical trials: the role of magnesium in acute myocardial infarction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2002 Jan-Feb;44(4):267-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeks JJ, Bossuyt PM, Gatsonis C (eds.). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Version 2.0. Cochrane, 2023.

- Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Oct;58(10):982-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter CM, Gatsonis CA. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat Med. 2001 Oct 15;20(19):2865-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Scenario | Under a fixed-effect framework | Under a fixed-effect framework |

|---|---|---|

| In non-operative management of uncomplicated appendicitis (antibiotics alone), is the success rate the same across all hospitals? | Assumes a single common success rate across all included hospitals, with observed variation attributed to sampling error. | Assumes that the pooled result represents the average success rate expected across a wider set of comparable hospitals, reflecting true underlying variation (e.g., due to case selection, imaging protocols, or discharge criteria). |

| Do ACE inhibitors lower blood pressure by the same amount in every patient? | Assumes a common true reduction (e.g., ~10 mmHg) for all included trials. Variation between reported effects is handled as sampling error around this shared underlying value. | Assumes the true reduction differs across patient populations and settings (e.g., larger in some groups, smaller in others), and the pooled value is the average across this distribution of true effects. |

| Does screening colonoscopy reduce colorectal cancer mortality equally in all health systems? | Assumes that screening colonoscopy provides the same mortality reduction regardless of context. | Assumes that the pooled estimate represents the average mortality reduction across a broader range of comparable screening programs, with true effects differing between programs (for example, due to differences in resources, coverage, or adenoma detection rates). |

| Does prone positioning reduce mortality in ARDS patients to the same extent across ICUs? | Assumes a uniform mortality reduction across all settings (e.g., 15%). | Treats differences in mortality effect as true variation between ICUs (e.g., protocolisation, staffing differences), with the pooled estimate representing the mean of these effects. |

| Do COVID-19 vaccines protect against infection? | Assumes identical vaccine effectiveness across all groups, regardless of age, comorbidity, or circulating variants. | Assumes true VE varies across populations and circumstances (e.g., age, comorbidities, circulating variants), and the pooled estimate is the average across this distribution. |

| Does a smoking cessation intervention increase quit rates equally across settings? | Assumes that this intervention produces the same improvement in quit rates everywhere, with any observed variation across studies explained only by chance. | Assumes quit rates vary across settings (e.g., greater with intensive behavioural support, lower with minimal support), and the pooled estimate is the mean across these true effects. |

| Criterion | Fixed-effect (common-effect) model | Random-effects model |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying assumption | Assumes a single true effect applies to all included studies; observed differences are attributed to sampling error. | Assumes true effects differ between studies and the pooled estimate is the mean of this distribution. |

|

Scope of inference |

Conditional: inference is restricted to the set of studies actually included in the meta-analysis. | Unconditional: inference targets a broader universe of comparable studies/settings. |

| Handling of study-level confounding | Robust to stable between-study confounding (measured or unmeasured), because all heterogeneity is conditioned out of the pooled estimate. | Vulnerable to study-level confounding, because the pooled effect averages across settings that may differ systematically in factors correlated with the effect. |

| Clinical diversity | Appropriate only when the included studies are functionally interchangeable regarding design, population, and context. | Appropriate when real differences exist across studies (patients, implementation, healthcare systems). |

| Generalizability | Limited to the included studies. | Broader: generalizes to comparable study settings. |

| Precision | Yields narrower intervals because between-study variance is not modelled. | Yields wider intervals because between-study variance is explicitly incorporated. |

| Role in practice | Suitable for sensitivity analyses, replication contexts, or intentionally conditional inference. | Preferred as the default approach in clinical meta-analysis when the goal is generalization. |

| Area | Cochrane guidance | Practical implication |

|---|---|---|

| Random-effects use | Random-effects models are generally preferred in the presence of clinical diversity (which is the usual situation in clinical research). | Use random-effects as the standard approach, since genuine variability between studies should be assumed unless proven otherwise. |

| Fixed-effects use | May be appropriate only when studies are truly comparable in design, population, and context. | Restrict fixed-effects to homogeneous data or sensitivity checks. |

| Role of heterogeneity statistics | Model choice should never be based solely on I² or Q; they are descriptive, not prescriptive. Both I² and Q can be biased, especially when the number of studies is small (which is common in meta-analysis). The most informative metric is τ², as it provides an absolute estimate of between-study variance. | Do not switch models based on I² thresholds. Report τ² as the primary measure of heterogeneity, and interpret I²/Q with caution, particularly in small meta-analyses. |

| Transparency | Authors should justify their model choice and, when appropriate, report both fixed- and random-effects models. | Present random-effects as primary, fixed-effects as sensitivity. |

| Confidence Intervals | Wald-type confidence intervals are often too narrow and overconfident, particularly when there are few studies. Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman (HKSJ) intervals are recommended, as they provide a more reliable reflection of uncertainty. | Always state which CI method was used in Methods. Prefer HKSJ over Wald, especially with few studies or moderate heterogeneity. |

| Prediction Intervals | Random-effects analyses should include prediction intervals to reflect the expected range of effects in new studies or settings. | Alongside confidence intervals, report prediction intervals to give clinicians a sense of how treatment effects might vary in practice. |

| Estimators of heterogeneity | The traditional DerSimonian–Laird estimator is outdated and can underestimate heterogeneity. More robust methods such as Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) or Paule–Mandel are recommended. | Use REML by default for τ² estimation, especially when the number of studies is small or heterogeneity is moderate to high. |

| Section | What should be reported | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Methods | - Pre-registration of the analysis protocol (e.g., in a registry like PROSPERO) - Software and commands used - Rationale for model choice (conceptual justification for using fixed vs random) - Model used (fixed vs random; explicitly report the τ² estimator employed, e.g., REML, Paule–Mandel, or DL) - CI method: explicitly state the procedure used (e.g., Wald, HKSJ, or truncated HKSJ) - Heterogeneity metrics: report Q, I², and τ² together with the τ² estimator used - Strategy to explore heterogeneity (subgroup, sensitivity, meta-regression) - Continuity corrections applied (e.g., 0.5 all-cells correction; treatment-arm continuity correction) - Software limitations (e.g., RevMan 5.4, CMA) |

Transparency; reproducibility; avoids selective reporting. |

| Results | - Forest plots that are legible and annotated - Study-level data (e.g., events per group over total) and pooled effects - Heterogeneity metrics: Q, I², τ² - CI 95% (with method specified, e.g., HKSJ) - PI 95% (when random-effects is used) |

Ensures clarity; communicates both precision (CI) and expected variability across contexts (PI); readers understand robustness of findings. |

| Case study | Clinical question | Original model & result | Re-analysed model & result | Key lesson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Urination stimulation in infants | Non-invasive stimulation to collect urine samples | FE Mantel–Haenszel: OR 3.88 (95% CI 2.28–6.60), p<0.01; I²=72% → strongly positive | RE REML: OR 3.44 (1.20–9.88), p=0.02; HKSJ: OR 3.44 (0.34–34.91), p=0.15 → wide, inconclusive | With k=3, τ² is highly unstable. FE treats heterogeneity as sampling error, whereas RE propagates between-study uncertainty, and HKSJ further widens the interval to reflect small-sample uncertainty. |

| 2. Esophageal atresia repair | Musculoskeletal sequelae after thoracoscopic vs open repair | FE Mantel–Haenszel: RR 0.35 (0.14–0.84), p=0.02 → significant reduction | RE REML: RR 0.35 (0.09–1.36), p=0.13; HKSJ: RR 0.35 (0.05–2.36), p=0.18 → loss of significance | When few retrospective studies are pooled, variance estimation dominates inference. A fixed-effect estimate is conditional on included studies, whereas random-effects shifts the target to a distribution of effects, widening uncertainty. |

| 3. Psychological Bulletin re-analysis | 68 psychology meta-analyses re-examined | FE gave narrow, often “significant” CIs; apparent robustness | RE widened CIs, significance often disappeared; FE defensible in ~3% only | Large-scale re-analysis shows that conditional inference under FE is often narrower than the more generalisable unconditional inference under RE. |

| 4. Rosiglitazone & CV risk | Myocardial infarction & cardiac death with rosiglitazone | FE: MI RR 1.43 (1.03–1.98), p=0.03 (↑ risk); cardiac death RR 1.64 (0.98–2.74), p=0.06 (NS) | RE (rare-event): MI RR 1.51 (0.91–2.48), p=0.11 (NS); cardiac death RR 2.37 (1.38–4.07), p=0.0017 (↑ risk) | When event rates are low, and heterogeneity interacts with effect direction, FE weights are dominated by large studies; RE reweights toward distributional heterogeneity, altering inference. |

| 5. Magnesium in acute MI | IV Mg²⁺ for AMI | FE: OR 1.02 (0.96–1.08) → null; extreme heterogeneity (p<0.0001) | RE: OR 0.61 (0.43–0.87), p=0.006 → protective | Heterogeneity here reflects an effect modifier (timing). FE assumes a single underlying effect; RE incorporates clinical variability, allowing the pooled estimate to align with mechanistic context. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).