Submitted:

31 August 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Research Conditions

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Research Content

2.3.1. Training Methods Used in the Research

2.3.2. Research Variables

2.3.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Inferential Statistics

- For Ground Contact Time: The t-statistic for the test is t = 2.71, which is greater than the minimum accepted two-tailed critical t-value (1.67), with a very high level of significance (p = 0.01 < 0.05) and a 95% confidence level. We conclude that the mean value for Ground Contact Time in the control group (0.55 sec) is higher than that in the experimental group (0.37 sec). The differences between the individual results and the mean values are statistically significant.

- For Flight Time: The t-statistic for the test is t = 3.69, which is greater than the minimum accepted two-tailed critical t-value (1.67), with a very high level of significance (p = 0.00 < 0.05) and a 95% confidence level. We conclude that the mean value for Flight Time in the control group (0.21 sec) is lower than that in the experimental group (0.29 sec). This difference is statistically significant, further confirming the research hypothesis.

- For the control group, the SD shows more homogeneous results (0.12) compared to the experimental group (0.01), and the CV is very small (0.01) for the experimental group, confirming the high consistency.

3.2. Statistical Association

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CG | Control group |

| EG | Experimental group |

References

- Abbes Z, Chamari K, Mujika I, Tabben M. Neuromuscular fitness and performance in young athletes: A scoping review. Biol Sport. 2021;38(3):391–403. [CrossRef]

- Zemková E, Kováciková Z, Šafárik R. Sport-specific training induced adaptations in postural control and their relationship with athletic performance: A scoping review. Front Physiol. 2022;13:792875. [CrossRef]

- Forte R, De Vito G. Comparison of neuromotor and progressive resistance exercise training to improve mobility and fitness in community-dwelling older women. J Sci Sport Exerc. 2019;1(2):124–31. [CrossRef]

- Pagaduan J, Pojskic H. Physical determinants of reaction time and agility in youth athletes. J Phys Educ Sport. 2020;20(6):3343–9. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Campillo R, Moran J, Chaabene H. Effects of plyometric jump training on physical fitness attributes in youth athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(4):365–79. [CrossRef]

- Sañudo B, de Hoyo M, Carrasco L. The effectiveness of a neuromuscular training program on physical performance in youth athletes: A systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(5):1367–73. [CrossRef]

- Pojskic H, Pagaduan J, Babajic F, Asceric M. Effects of training on reaction time and agility in young male athletes. J Hum Kinet. 2022;82(1):179–88. [CrossRef]

- Reigal RE, Barrero S, Martín I, Morales-Sánchez V, Juárez-Ruiz de Mier R, Hernández-Mendo A. Relationships between reaction time, selective attention, physical activity, and physical fitness in children. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2278. [CrossRef]

- Beck S, Hossner EJ, Zahno D. Mechanisms for handling uncertainty in sensorimotor control in sports: A scoping review. Front Sports Act Living. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Montoro-Bombú R, de la Paz Arencibia L, Buzzichelli C, Miranda-Oliveira P, Fernandes O, Santos A, et al. The validity of the Push Band 2.0 on the Reactive Strength Index assessment in Drop Jump. Sensors (Basel). 2022;22(13):4724. [CrossRef]

- Macedo M, Silva T, de Andrade A. Visual feedback devices increase neuromuscular engagement in youth athleteA pilot study using OptoJump. J Sports Eng Technol. 2022;236(4):317–24. [CrossRef]

- Pereira J, Fernandes RJ, Silva A. Technological tools and motivational feedback in young athletes’ training: A systematic review. Eur J Hum Mov. 2023;50:12–22. [CrossRef]

- Gierczuk D, Cieśliński I, Bujak Z, Sadowski J. Relationship between selected strength and power variables and sports level in Greco-Roman wrestlers aged 14–18 years. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4813. [CrossRef]

- Zugaj N, Karnincic H, Baic M. Differences in motor, functional, and sport-specific skills in gifted wrestlers with different acceleration of biological development. Sport Mont. 2023;21(1):117–21.

- Tashnazarov R, Karimov M, Nasimov M. The role of neuromuscular preparedness in tactical wrestling performance. World J Wrestl Res. 2022;1(1):33–9.

- Akhmetov R, Khusainov R, Nurgaliev A. Neuromuscular coordination and reaction speed in young wrestlers. J Phys Educ Sport. 2021;21(3):1485–91. [CrossRef]

- Petrov M, Dimitrov T. Neuromotor training interventions in youth wrestling: Effects on explosive power. Eur J Wrestl Sci. 2023;5(1):22–31.

- Balsalobre-Fernández C, Romero-Franco N, Jiménez-Reyes P. Performance assessment and monitoring using new technologies: A theoretical framework. Sports. 2021;9(5):66. [CrossRef]

- Longakit J, Aque FJ, Toring-Aque L, Lobo J, Ayubi N, Mamon R, Coming L, Padilla DK, Mondido CA, Sinag JM, Geanta VA, Sanjaykumar S. The effect of a 4-week plyometric training exercise on specific physical fitness components in U21 novice volleyball players. Pedagogy of Physical Culture and Sports. 2025;29(2):86-95. [CrossRef]

- Mocanu GD, Murariu G, Potop V. Differences in explosive strength values for students of the faculty of physical education and sports (male) according to body mass index levels. Pedagogy of Physical Culture and Sports. 2023;27(1):71-83. [CrossRef]

- Bujalance-Moreno P, Fortes V, Gallardo L. Effects of combined plyometric and specific wrestling training on performance in youth Greco-Roman wrestlers. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2020;15(5–6):686–94. [CrossRef]

- Nagovitsyn RS, Koryagina IA, Kharisova GR. Adaptive models of training in combat sports for junior athletes. J Phys Educ Sport. 2019;19(5):1534–40. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Arrones L, Sáez de Villarreal E, Requena B. Integrative strength and tactical training in combat sports: A pathway to improve transferability. Strength Cond J. 2022;44(5):44–51. [CrossRef]

- Chaabene H, Negra Y, Capranica L, Bouguezzi R, Hachana Y, Granacher U. Specific physical training in young combat athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2020;11:1099. [CrossRef]

- Slimani M, Miarka B, Briki W, Chamari K. Comparison of mental toughness and power output between male and female combat sport athletes. Physiol Behav. 2021;237:113367. [CrossRef]

- Beato M, Drust B. The importance of high-intensity training and neuromuscular specificity in youth combat athletes: A practical framework. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021;6(2):36. [CrossRef]

- Hammami M, Zois J, Slimani M, Bouhlel E, Granacher U. The effects of neuromuscular and decision-making training on physical and technical performance in young athletes: A randomized controlled trial. Biol Sport. 2022;39(4):835–44. [CrossRef]

- Brito J, Figueiredo P, Fernandes L, Seabra A, Rebelo A. Monitoring training load, well-being, and variation in physical performance in young athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020;15(8):1098–105. [CrossRef]

- Jlid MC, Paillard T, Zouhal H. Validity and reliability of the OptoJump system for assessing reactive strength and vertical jump performance in youth athletes. Biol Sport. 2022;39(3):685–92. [CrossRef]

- Latyshev M, Sergeev N, Kudinov A. Individualization of physical training in youth wrestling based on motor characteristics. Teor Prakt Fiz Kult. 2020;12:23–5.

- Ramos-Campo DJ, Ávila-Gandía V, Martínez-Rodríguez A. Specific physical conditioning in combat sports: A practical update for trainers. Strength Cond J. 2022;44(2):52–60. [CrossRef]

- Aquino R, Carling C, Palucci Vieira LH, Gonçalves LGC, Puggina EF. Tactical behavior and its relationship with physical and technical performance in youth combat sports. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2023;23(2):215–27. [CrossRef]

- Aquino R, Sampaio-Jorge F, Freitas TT, Miranda R, Loturco I. Performance predictors in youth wrestlers: Strength and neuromuscular factors. J Hum Kinet. 2023;87:97–108. [CrossRef]

- Aquino R, Vieira LHP, Cruz GCF, Carling C, Kellis E. Neuromuscular and mechanical performance parameters in combat sports: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2023;53(1):85–100. [CrossRef]

- Hurramovich U, Zikrillayevich M. Physical training technology in Greco-Roman wrestling. Asian J Multidimens Res. 2020;9(6):45–52. [CrossRef]

- Petrov A, Zimkin D. Standardization of physical performance in junior combat athletes: Methodological considerations. Phys Educ Theory Pract. 2020;26(1):87–91.

- Mihaiu, C., Stefanica, V., Joksimović, M., Ceylan, H. İ., & Pirvu, D. (2024). Impact of Specific Plyometric Training on Physiological and Performance Outcomes in U16 Performance Athletes Soccer Players. Revista Romaneasca pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 16(3), 206-223. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/16.3/891. [CrossRef]

| No | Control Group | Age | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | BMI (kg/m²) |

Experimental Group |

Age | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | BMI (kg/m²) |

| 1 | M.N. | 12 | 57 | 167 | 0.34 | T.V. | 12 | 38 | 146 | 0.26 |

| 2 | C.D. | 11 | 50 | 160 | 0.31 | R.L. | 11 | 28 | 135 | 0.21 |

| 3 | G.S. | 12 | 60 | 169 | 0.36 | E.F. | 12 | 43 | 161 | 0.27 |

| 4 | L.I. | 11 | 58 | 157 | 0.37 | P.C. | 10 | 53 | 164 | 0.32 |

| 5 | A.T. | 12 | 48 | 157 | 0.31 | N.D. | 12 | 50 | 152 | 0.33 |

| 6 | D.C. | 9 | 40 | 136 | 0.29 | I.M. | 11 | 70 | 172 | 0.41 |

| 7 | V.B. | 10 | 34 | 135 | 0.25 | K.S. | 12 | 69 | 160 | 0.44 |

| 8 | H.P. | 11 | 47 | 153 | 0.31 | M.E. | 10 | 104 | 180 | 0.61 |

| 9 | R.A. | 11 | 61 | 148 | 0.41 | Z.M. | 12 | 61 | 172 | 0.35 |

| 10 | E.T. | 12 | 67 | 173 | 0.39 | B.C. | 11 | 67 | 138 | 0.49 |

| 11 | S.O. | 9 | 40 | 133 | 0.3 | C.I. | 10 | 42 | 162 | 0.26 |

| 12 | T.R. | 12 | 75 | 161 | 0.47 | A.G. | 11 | 49 | 160 | 0.31 |

| 13 | I.F. | 12 | 38 | 147 | 0.26 | O.N. | 10 | 41 | 136 | 0.3 |

| 14 | P.M. | 12 | 78 | 168 | 0.46 | U.S. | 11 | 50 | 158 | 0.32 |

| Period | Activity |

| March 2023 | Initial Testing |

| April 2023 – August 2024 | Implementation of the Intervention Program |

| September 2024 | Final Testing |

| OptoJump Variables | Height | Power | Pace | RSI | T Cont. | T Flight |

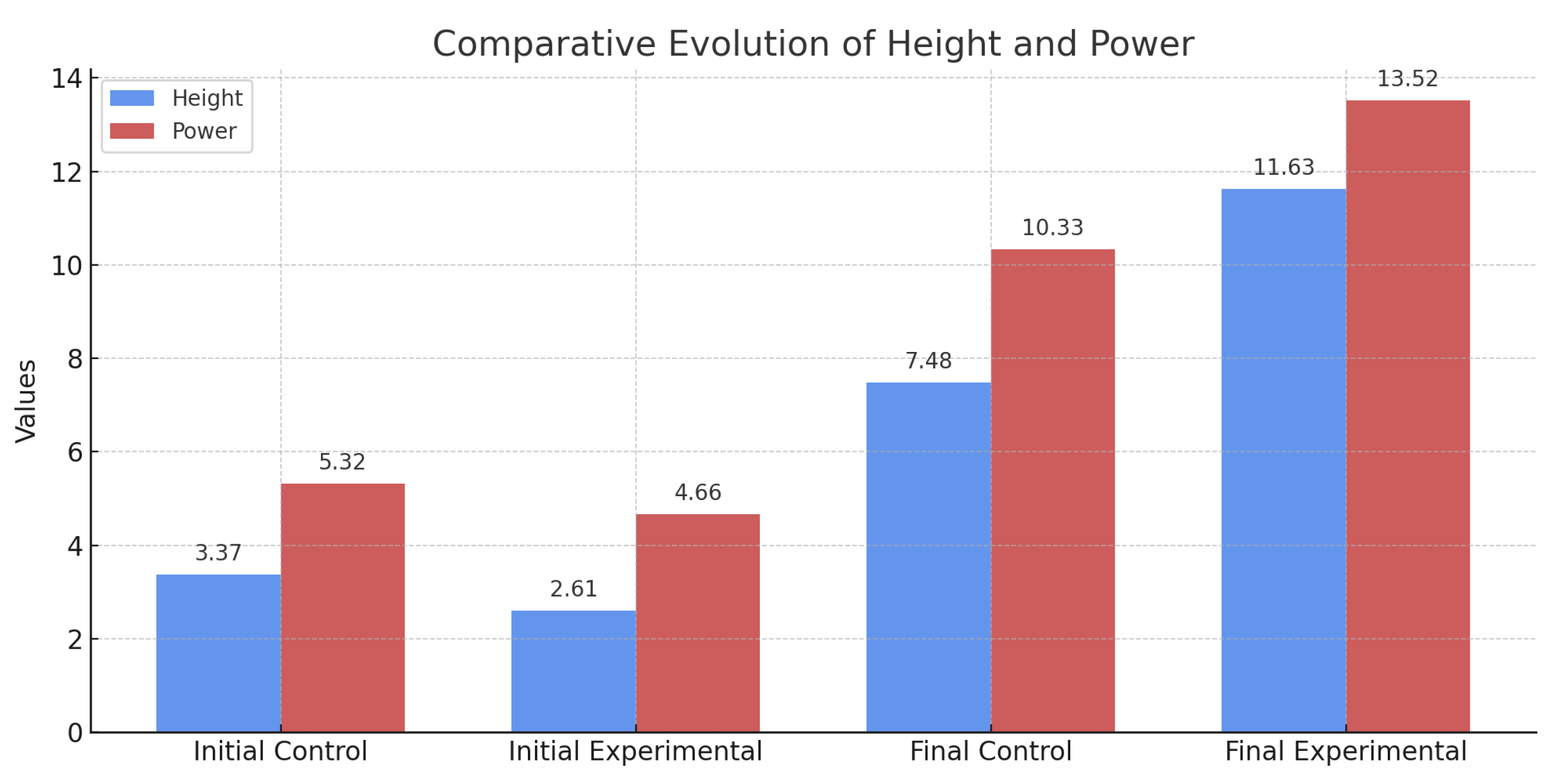

| Initial Testing Control Group | 3.37 | 5.32 | 1.62 | 0.07 | 0.54 | 0.16 |

| Initial Testing Experimental Group | 2.61 | 4.66 | 1.76 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 0.14 |

| Final Testig Control Group | 7.48 | 10.33 | 1.57 | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.21 |

| Final Testig Experimental Group | 11.63 | 13.52 | 1.57 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.3 |

| Indicators | Mean | SD | CV | t Stat | P(T<=t) one-tail | t Critical one-tail | P(T<=t) two-tail | t Critical two-tail | |

| Ground Contact Time | CG* EG** |

0.55 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 2.71 | 0.00 | 1.67 | 0.01 | 2.01 |

| 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Flight Time | CG EG |

0.21 | 0.09 | 0.01 | -3.69 | 0.00 | 1.67 | 0.00 | 2.01 |

| 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Indicators | Mean | SD | CV | t Stat | P(T<=t) one-tail | t Critical one-tail | P(T<=t) two-tail | t Critical two-tail | |

| Height | CG EG |

7.61 | 8.30 | 68.95 | -2.10 | 0.02 | 1.67 | 0.04 | 2.01 |

| 11.60 | 1.50 | 2.24 | |||||||

| Power | CG EG |

10.52 | 11.56 | 133.70 | -1.21 | 0.11 | 1.67 | 0.23 | 2.01 |

| 13.50 | 1.76 | 3.09 | |||||||

| Indicators | Mean | SD | CV | t Stat | P(T<=t) one-tail | t Critical one-tail | P(T<=t) two-tail | t Critical two-tail | |

| Cadence | CG EG |

1.56 | 0.37 | 0.14 | -0.10 | 0.46 | 1.67 | 0.92 | 2.01 |

| 1.57 | 0.18 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Reactive Strength Index (RSI) | CG EG |

0.27 | 0.50 | 0.24 | -0.56 | 0.29 | 1.68 | 0.58 | 2.01 |

| 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Control | Test | T Cont. | T Flight | Height | Power | Pace | RSI |

| Test | 1.00 | ||||||

| T Cont. | 0.04 | 1.00 | |||||

| T Flight | 0.37 | -0.03 | 1.00 | ||||

| Height | 0.33 | -0.08 | 0.90 | 1.00 | |||

| Power | 0.29 | -0.16 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 1.00 | ||

| Pace | -0.08 | -0.67 | -0.42 | -0.31 | -0.20 | 1.00 | |

| RSI | 0.26 | -0.19 | 0.72 | 0.88 | 0.99 | -0.13 | 1.00 |

| Experiment | Test | T Cont. | T Flight | Height | Power | Pace | RSI |

| Test | 1.00 | ||||||

| T Cont. | -0.37 | 1.00 | |||||

| T Flight | 0.81 | -0.32 | 1.00 | ||||

| Height | 0.78 | -0.30 | 0.98 | 1.00 | |||

| Power | 0.78 | -0.37 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1.00 | ||

| Pace | -0.35 | -0.37 | -0.63 | -0.58 | -0.57 | 1.00 | |

| RSI | 0.76 | -0.40 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.99 | -0.50 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).