Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Manure Production and Management

2.2. Calculation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Manure Management

2.3. Projections of Manure Production and Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050

3. Results

3.1. Manure Production and a Projection Thereof in Agriculture Until 2050 in Latvia

3.2. Amounts of Greenhouse Gases from Manure Management and a Projection Thereof for 2050 for Latvia

4. Discussion

4.1. The Need to Improve the Production, Use, and Management of Manure

4.2. Potential Reduction of GHG Emissions from Manure Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| % | Percentage Rate |

| CH4 | Methane |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CO2 eq. | Carbon dioxide equivalent |

| EF | Emission factors |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gases |

| Gt | Gigatons |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| Kg | Kilogram |

| Kt | Kilotons |

| LASAM | Latvian Agricultural Sector Analysis Model |

| N | Nitrogen |

| N2O | Nitrous oxide |

| NECP | National Energy and Climate Plan (Latvia) |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| NIR | Latvia’s National Inventory Report |

| Nox | Nitrous oxide |

| t | Tone |

| Thou. | Thousand |

References

- Giosanu, D.; Bucura, F.; Constantinescu, M.; Zaharioiu, A.; Vîjan, L. E.; Mățăoanu, G. The Nutrient Potential of Organic Manure and its Risk to the Environment. Current Trends in Natural Sciences 2022. 11(21), 153. [CrossRef]

- agadeesha, G. S.; Prakasha, H. C.; Shivakumara, M. N.; Govinda, K.; Yogananda, S. B. Evaluation of Rock Phosphate Enriched Compost on Soil Nutrient Status after Harvest of Finger Millet-Cowpea Cropping Sequence in High Phosphorus Soils of Cauvery Command Area, Karnataka. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 2021,17. [CrossRef]

- Devianti, D.; Yusmanizar, Y.; Syakur, S.; Munawar, A. A.; Yunus, Y. Organic fertilizer from agricultural waste: determination of phosphorus content using near infrared reflectance. IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 644(1), 12002. [CrossRef]

- Arha, A.; Kaushik, R. A.; Lakhawat, S. S.; Bairwa, H. L.; Verma, A. Effect of Integrated Nutrient Management on Growth, Flowering and Yield of Gaillardia. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2021,10(1), 3461. [CrossRef]

- Ponmozhi, C. N. I.; Kumar, R.; Baba, Y. A.; Rao, G. M. Effect of Integrated Nutrient Management on Growth and Yield of Maize (Zea mays L.). International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2019, 8(11), 2675. [CrossRef]

- Kandil, E.; Abdelsalam, N. R.; Mansour, M. A.; Ali, H. M.; Siddiqui, M. H. Potentials of organic manure and potassium forms on maize (Zea mays L.) growth and production. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Hirich, E.H.; Bouizgarne, B.; Zouahri, A.; Ibn Halima, O.; Azim, K. How Does Compost Amendment Affect Stevia Yield and Soil Fertility? Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 16, 46. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. Application of Nano Organic Materials in Agriculture farming and yield analysis for Groundnut crop with comparison to conventional inorganic farming. IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 785(1), 12008. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Smith, W.; VanderZaag, A. Dairy manure nutrient recovery reduces greenhouse gas emissions and transportation cost in a modeling study. Frontiers in Animal Science 2023, 4. [CrossRef]

- Philippe, F.-X.; Nicks, B. Review on greenhouse gas emissions from pig houses: Production of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide by animals and manure. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 2014, 199, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Pathways towards lower emissions – A global assessment of the greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation options from livestock agrifood systems. 2023, Rome. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4060/cc9029en (accessed on 07 July 2025).

- Moran, D.; Wall, E. Livestock production and greenhouse gas emissions: Defining the problem and specifying solutions. Animal Frontiers 2011, 1(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.; Fao, R.A. P.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling climate change through livestock. 2013. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=XF2016016977 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Kreidenweis, U.; Breier, J.; Herrmann, C.; Libra, J. A.; Prochnow, A. Greenhouse gas emissions from broiler manure treatment options are lowest in well-managed biogas production. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 280, 124969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Cain, M.; Frame, D. J.; Pierrehumbert, R. T. Agriculture’s Contribution to Climate Change and Role in Mitigation Is Distinct From Predominantly Fossil CO2-Emitting Sectors. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M. Analyzing Similarities between the European Union Countries in Terms of the Structure and Volume of Energy Production from Renewable Energy Sources. Energies 2020, 13(4), 913. [CrossRef]

- Krämer, L. Planning for Climate and the Environment: the EU Green Deal. Journal for European Environmental & Planning Law 2020, 17(3), 267. [CrossRef]

- Bellanca, M. What, How and Where: An Assessment of Multi-Level European Climate Mitigation Policies. Research Square 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciot, M. Implementation Perspectives for the European Green Deal in Central and Eastern Europe. Sustainability 2022, 14(7), 3947. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D. V.; Kolinjivadi, V.; Ferrando, T.; Roy, B.; Herrera, H.; Gonçalves, M. V.; Hecken, G. V. The “Greening” of Empire: The European Green Deal as the EU first agenda. Political Geography 2023, 105, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.; Pye, S.; Betts-Davies, S.; Broad, O.; Price, J.; Eyre, N.; Anable, J.; Brand, C.; Bennett, G.; Carr-Whitworth, R.; Garvey, A.; Giesekam, J.; Marsden, G.; Norman, J.; Oreszczyn, T.; Ruyssevelt, P.; Scott, K. Energy demand reduction options for meeting national zero-emission targets in the United Kingdom. Nature Energy 2022, 7(8), 726. [CrossRef]

- Konara, K. M. G. K.; Tokai, A. Evaluating the Energy Metabolic System in Sri Lanka. Journal of Sustainable Development, 2020, 13(4), 235. [CrossRef]

- Kļaviņš, M.; Bruneniece, I.; Bisters, V. Development of national climate and adaptation policy in Latvia. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2009, 1(1), 75. [CrossRef]

- Latvia’s National Energy and Climate Plan 2021-2030. 2024, 135 p. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/3e07cbed-22c0-4b69-a8e5-887e0c6aa09e_en?filename=LV_FINAL%20UPDATED%20NECP%202021-2030%20%28English%29_0.pdf (accessed on 08 July 2025).

- Research “Forecasting agricultural development and developing policy scenarios until 2050” (in Latvian). LBTU, 2024, 166 p. Available online: https://www.lbtu.lv/sites/default/files/files/projects/S486_Irina_Pilvere_24-00-S0INZ03-000006.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Pilvere, I.; Nipers, A.; Krievina, A.; Upite, I.; Kotovs, D. LASAM Model: An Important Tool in the Decision Support System for Policymakers and Farmers. Agriculture 2022, 12, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvia`s National Inventory Report under the UNFCCC “Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Latvia from 1990 to 2022”. Riga, 2024. Available online: https://videscentrs.lvgmc.lv/files/Klimats/SEG_emisiju_un_ETS_monitorings/Zinojums_par_klimatu/SEG_zinojums/2024/ (accessed on 02 July 2025).

- IPCC 2006. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Prepared by the National. Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, Eggleston H.S., Buendia L., Miwa K., Ngara T. and Tanabe K. (eds). Published: IGES, Japan. Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/vol1.html (accessed on 07 July 2025).

- Makutėnienė, D.; Perkumienė, D.; Makutėnas, V. Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index Decomposition Based on Kaya Identity of GHG Emissions from Agricultural Sector in Baltic States. Energies 2022, 15, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Latvia Cabinet Regulation, No. 834 Adopted 23 December 2014 Requirements Regarding the Protection of Water, Soil and Air from Pollution Caused by Agricultural Activity. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/271376-noteikumi-par-udens-un-augsnes-aizsardzibu-no-lauksaimnieciskas-darbibas-izraisita-piesarnojuma-ar-nitratiem (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Research “Development of a methodology for calculating GHG emissions in the agricultural sector and data analysis with a modeling tool, integrating climate change”, sub-project “Studies of manure management systems in Latvia” (in Latvian). 2014, 141 p. Available online: https://ppdb.mk.gov.lv/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/petijums_VARAM_2017_Lauksaimn_SEG_emisij_aprek_metodolog_un_datu_analiz_ar_model_riku_izstrad_integrej_klim_mainas.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Pilvere, I.; Krievina, A.; Upite, I.; Nipers, A. Datasets for Manure Projections in Latvia: Challenges and Potential for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. 2025, Available online: https://dv.dataverse.lv/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.71782/DATA/DWMW7G (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Shepherd, M. Managing manures in organic farming. Proceedings of the British Society of Animal Science 2003, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamouri, E.; Zisis, F.; Mitsiopoulou, C.; Christodoulou, C.; Pappas, A. C.; Simitzis, P.; Kamilaris, C.; Galliou, F.; Manios, T.; Mavrommatis, A.; Tsiplakou, E. Sustainable Strategies for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction in Small Ruminants Farming. Sustainability 2023, 15(5), 4118. [CrossRef]

- Ronga, D.; Mantovi, P.; Pacchioli, M. T.; Pulvirenti, A.; Bigi, F.; Allesina, G.; Pedrazzi, S.; Tava, A.; Prà, A. D. Combined Effects of Dewatering, Composting and Pelleting to Valorize and Delocalize Livestock Manure, Improving Agricultural Sustainability. Agronomy 2020, 10(5), 661. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-R.; Tsai, W. Valorization of Value-Added Resources from the Anaerobic Digestion of Swine-Raising Manure for Circular Economy in Taiwan. Fermentation 2020, 6(3), 81. [CrossRef]

- Meester, S. D.; Demeyer, J.; Velghe, F.; Peene, A.; Langenhove, H. V.; Dewulf, J. The environmental sustainability of anaerobic digestion as a biomass valorization technology. Bioresource Technology 2012, 121, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Awada, T.; Shi, Y.; Jin, V. L.; Kaiser, M. Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions From Agriculture: Pathways to Sustainable Reductions. Global Change Biology 2024, 31(1). [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, Y.; Duan, W.; Qiao, C.; Shen, Q.; Li, R. Microbial community composition turnover and function in the mesophilic phase predetermine chicken manure composting efficiency. Bioresource Technology 2020, 313, 123658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venczel, M. Z.; Powers, S. E. Anaerobic Digestion and Related Best Management Practices: Utilizing Life Cycle Assessment. 2010 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, June 20 - June 23, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Woolery, S.; Osei, E.; Yu, M.; Güney, S.; Lovell, A. C.; Jafri, H. The Carbon Footprint of a 5000-Milking-Head Dairy Operation in Central Texas. Agriculture 2023, 13(11), 2109. [CrossRef]

- Nasiru, A.; Ibrahim, M. H.; Ismail, N. Nitrogen losses in ruminant manure management and use of cattle manure vermicast to improve forage quality. International Journal Of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture 2014, 3(2). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, T.; Zheng, C. Effects of biochar carried microbial agent on compost quality, greenhouse gas emission and bacterial community during sheep manure composting. Biochar 2023, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Romera, A. J.; Cichota, R.; Beukes, P. C.; Gregorini, P.; Snow, V.; Vogeler, I. Combining Restricted Grazing and Nitrification Inhibitors to Reduce Nitrogen Leaching on New Zealand Dairy Farms. Journal of Environmental Quality 2016, 46(1), 72. [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Wang, H.; Hu, S.; Jiao, J. Effects of Afforestation Restoration on Soil Potential N2O Emission and Denitrifying Bacteria After Farmland Abandonment in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, A. N.; Oh, J.-A.; Lee, C.; Meinen, R. J.; Montes, F.; Ott, T.; Firkins, J. L.; Rotz, A.; Dell, C. J.; Adesogan, C.; Yang, W.; Tricárico, J. M.; Kebreab, E.; Waghorn, G. C.; Dijkstra, J.; Oosting, S. J.; Mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions in livestock production - A review of technical options for non-CO2 emissions. 2013,177(177). Available online: https://www.uncclearn.org/sites/default/files/inventory/fao180.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Hernandez-Ramirez, G.; Ruser, R.; Kim, D. How does soil compaction alter nitrous oxide fluxes? A meta-analysis. Soil and Tillage Research 2021, 211, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R. T.; Paustian, K. Potential soil carbon sequestration in overgrazed grassland ecosystems. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2002, 16(4), 1143. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.; Infascelli, F. The Path to Sustainable Dairy Industry: Addressing Challenges and Embracing Opportunities. Sustainability 2025, 17(9), 3766. [CrossRef]

- Ivanovich, C.; Sun, T.; Gordon, D. R.; Ocko, I. Future warming from global food consumption. Nature Climate Change 2023, 13(3), 297. [CrossRef]

- Hasukawa, H.; Inoda, Y.; Toritsuka, S.; Sudo, S.; Oura, N.; Sano, T.; Shirato, Y.; Yanai, J. Effect of Paddy-Upland Rotation System on the Net Greenhouse Gas Balance as the Sum of Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions and Soil Carbon Storage: A Case in Western Japan. Agriculture 2021, 11(1), 52. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Cain, M.; Frame, D. J.; Pierrehumbert, R. T. Agriculture’s Contribution to Climate Change and Role in Mitigation Is Distinct From Predominantly Fossil CO2-Emitting Sectors. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalal, H.; Sucu, E.; Cavallini, D.; Giammarco, M.; Akram, M. Z.; Karkar, B.; Gao, M.; Pompei, L.; Eduardo, J.; Prasinou, P.; Fusaro, I. Rumen fermentation profile and methane mitigation potential of mango and avocado byproducts as feed ingredients and supplements. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Scialabba N.E.-H.; Müller-Lindenlauf M. Organic agriculture and climate change. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2010, 25(2),158-169. [CrossRef]

- Yona, L.; Cashore, B.; Jackson, R.B.; Ometto, J.; Bradford, M.A. Refining national greenhouse gas inventories. Ambio 2020, 49, 1581–1586. [CrossRef]

| Category of farm animals | Pasture | Solid manure | Liquid-manure | Manure without litter |

Fresh manure (pasture) | Solid manure | Liquid manure | Manure without litter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy cows* | x | x | x | - | 9.0 | 15.0 | 19.0 | - |

| Dairy cow calves (up to 1 year old) | x | x | - | - | 4.2 | 7.0 | - | - |

| Dairy cow young cattle (1-2 years old) | x | x | - | - | 6.6 | 11.0 | - | - |

| Beef cattle calves (up to 1 year old) | x | x | - | - | 3.6 | 6.0 | - | - |

| Beef young cattle (1-2 years old) | x | x | - | - | 6.0 | 10.0 | - | - |

| Other bovine animals (over 2 years old) | x | x | - | - | 5.4 | 9.0 | - | - |

| Sows and boars | - | x | x | - | - | 1.5 | 2.5 | - |

| Piglets (up to 4 months old) | - | x | x | - | - | 0.4 | 0.65 | - |

| Pigs for fattening (from 4 months old) | - | x | x | - | - | 1.2 | 2.2 | - |

| Sheep | x | x | - | - | 1.5 | 2.4 | - | - |

| Goats | x | x | - | - | 1.5 | 2.4 | - | - |

| Horses | x | x | - | - | 5 | 10.0 | - | - |

| Laying hens | x | x | - | x | 0.04 | 0.05 | - | 0.03 |

| Broilers | - | x | - | - | - | 0.01 | - | - |

| Geese | x | x | - | - | 0.03 | 0.04 | - | - |

| Ducks | x | x | - | - | 0.05 | 0.06 | - | - |

| Turkeys | x | x | - | - | 0.12 | 0.14 | - | - |

| Deer | x | - | - | - | 1.2 | - | - | - |

| Category of farm animals |

CH4 emissions from manure management, kg per year per animal | N excreted, kg per year per animal |

|---|---|---|

| Dairy cows | 20.81 | 120.4 |

| Cattle under 2 years old | 1.13 | 19.9 |

| Cattle over 2 years old | 2.02 | 63.3 |

| Pigs | 2.15 | 10.3 |

| Sheep | 0.19 | 15.30 |

| Goats | 0.13 | 15.80 |

| Horses | 1.56 | 44.00 |

| Laying hens | 0.03 | 0.55 |

| Broilers and others | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| Turkeys | 0.09 | 1.64 |

| Ducks | 0.02 | 0.58 |

| Geese | 0.02 | 1.12 |

| Deer | 0.22 | 12.00 |

| Category of farm animals | Pasture | Solid manure | Liquid manure | Anaerobic digester |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy cows | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.18 |

| Dairy cow calves up to 1 year old | 0.06 | 0.80 | - | 0.14 |

| Dairy cow, young cattle 1-2 years old | 0.06 | 0.80 | - | 0.14 |

| Beef cattle calves up to 1 year old | 0.79 | 0.21 | - | - |

| Beef young cattle 1-2 years old | 0.79 | 0.21 | - | - |

| Other cattle | 0.79 | 0.21 | - | - |

| Sows and boars | - | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Piglets up to 4 months old | - | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Fattening and young breeding pigs over 4 months old | - | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Sheep | 0.38 | 0.62 | - | - |

| Goats | 0.10 | 0.90 | - | - |

| Horses | 0.35 | 0.65 | - | - |

| Laying hens | 0.04 | 0.45 | - | 0.51 |

| Broilers | - | 1 | - | - |

| Geese | 0.29 | 0.71 | - | - |

| Ducks | 0.32 | 0.69 | - | - |

| Turkeys | 0.30 | 0.70 | - | - |

| Deer | 1 | - | - | - |

| Indicators | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | 2050/2023, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy cows | 2260.3 | 2239.1 | 2141.8 | 2145.8 | 2333.8 | 2433.7 | 2453.8 | 2438.4 | 2426.5 | 113 |

| Solid manure | 863.1 | 814.6 | 735.7 | 684.8 | 621.7 | 543 | 459.9 | 384.8 | 323.1 | 44 |

| Liquid manure | 1277.3 | 1311.3 | 1303.9 | 1365.9 | 1625.7 | 1815.3 | 1930 | 2000.1 | 2058.5 | 158 |

| Fresh manure (pasture) | 119.9 | 113.2 | 102.2 | 95.1 | 86.4 | 75.4 | 63.9 | 53.5 | 44.9 | 44 |

| Other cattle | 1869.2 | 1881.1 | 1753.3 | 1697.6 | 1718.3 | 1704 | 1671.2 | 1642 | 1631.9 | 93 |

| Solid manure | 1285.1 | 1300.6 | 1179.3 | 1148.8 | 1175.7 | 1169.9 | 1146.4 | 1125.3 | 1120.8 | 95 |

| Fresh manure (pasture) | 584.1 | 580.5 | 574.0 | 548.8 | 542.6 | 534.1 | 524.8 | 516.7 | 511.1 | 89 |

| Pigs | 471.6 | 442.2 | 415.7 | 433.4 | 431.5 | 431 | 428.8 | 426.7 | 424.6 | 102 |

| Solid manure | 13.9 | 10.7 | 9.4 | 8.4 | 5.7 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 13 |

| Liquid manure | 457.7 | 431.5 | 406.3 | 425 | 425.8 | 427.1 | 426.2 | 424.9 | 423.4 | 104 |

| Laying hens | 107.6 | 105.9 | 107.3 | 107.4 | 107.2 | 107 | 106.6 | 106.2 | 106 | 99 |

| Solid manure | 11.4 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 51 |

| Manure without litter | 91.7 | 90.3 | 91.4 | 92.1 | 93.3 | 94.5 | 95.6 | 96.7 | 97.9 | 107 |

| Fresh manure (pasture) | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 51 |

| Broilers | 23.9 | 23.5 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 100 |

| Solid manure | 23.9 | 23.5 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 100 |

| Other poultry* | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 138 |

| Solid manure | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 133 |

| Fresh manure (pasture) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 100 |

| Sheep | 176.2 | 170.4 | 152.7 | 144.6 | 130.3 | 120.3 | 112.7 | 106.6 | 101.4 | 66 |

| Solid manure | 108.6 | 105 | 94.1 | 89.1 | 80.3 | 74.1 | 69.5 | 65.7 | 62.5 | 66 |

| Fresh manure (pasture) | 67.6 | 65.4 | 58.6 | 55.5 | 50 | 46.2 | 43.2 | 40.9 | 38.9 | 66 |

| Goats | 25.9 | 26.5 | 23.5 | 23.2 | 22.7 | 22.1 | 21.8 | 21.5 | 21.1 | 90 |

| Solid manure | 23.4 | 23.9 | 21.2 | 21 | 20.5 | 20 | 19.7 | 19.4 | 19.1 | 90 |

| Fresh manure (pasture) | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 87 |

| Horses | 62.1 | 64.4 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 100 |

| Solid manure | 40.2 | 41.7 | 43.1 | 43.1 | 43.1 | 43.1 | 43.1 | 43.1 | 43.1 | 100 |

| Fresh manure (pasture) | 21.9 | 22.7 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 100 |

| Deer | 20.4 | 19.4 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 100 |

| Fresh manure (pasture) | 20.4 | 19.4 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 100 |

| Total | 5018.3 | 4973.5 | 4700.7 | 4658.4 | 4850.4 | 4924.7 | 4901.5 | 4848.1 | 4818.2 | 102 |

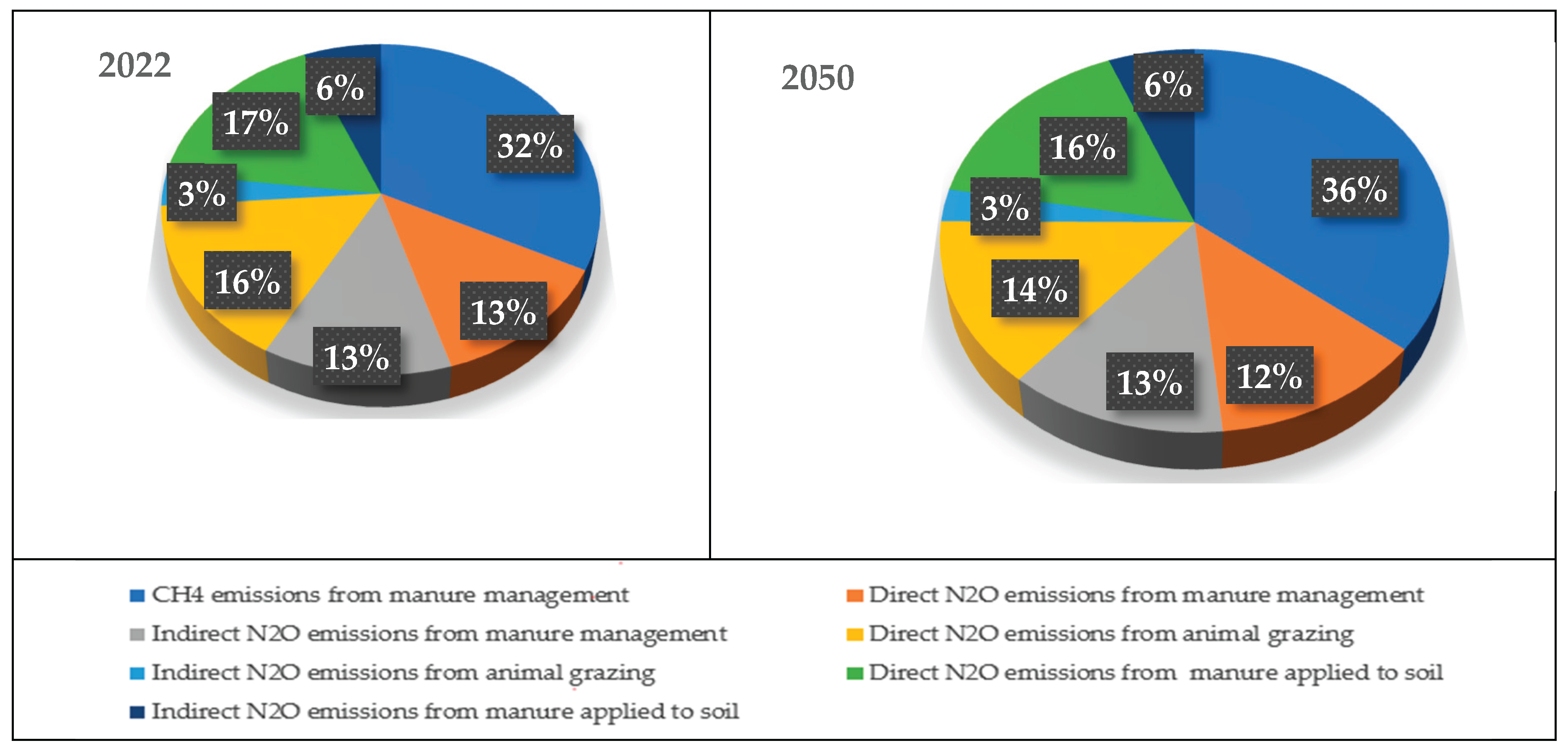

| Kinds of emissions | 2021 | 2022 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | 2050/2022, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 emissions from manure management | 105.2 | 108.6 | 105.6 | 112.0 | 115.7 | 116.1 | 114.9 | 113.6 | 105 |

| Direct N2O emissions from manure management | 42.7 | 43.1 | 39.6 | 40.6 | 41.1 | 40.8 | 40.2 | 39.9 | 92 |

| Indirect N2O emissions from manure management | 43.8 | 42.8 | 38.8 | 40.4 | 41.1 | 41.0 | 40.6 | 40.3 | 94 |

| Direct N2O emissions from animal grazing | 52.4 | 52.9 | 49.2 | 48.4 | 47.3 | 46.1 | 45.1 | 44.3 | 84 |

| Indirect N2O emissions from animal grazing | 10.4 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 83 |

| Direct N2O emissions from manure applied to soil | 56.8 | 56.2 | 51.4 | 52.4 | 52.9 | 52.5 | 51.7 | 51.2 | 91 |

| Indirect N2O emissions from manure applied to soil | 21.2 | 20.9 | 19.1 | 19.5 | 19.7 | 19.6 | 19.3 | 19.1 | 91 |

| Total GHG emissions related to animal manure management | 332.6 | 335.1 | 313.5 | 322.9 | 327.2 | 325.1 | 320.6 | 317.1 | 95 |

| Total GHG emissions from agriculture | 2245.3 | 2242.5 | 2160.0 | 2234.0 | 2269.3 | 2277.9 | 2277.2 | 2281.0 | 102 |

| Total GHG emissions related to animal manure management, % of the total | 14.8 | 14.9 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.4 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 13.9 |

-1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).