2.2.2. Data Collection Techniques

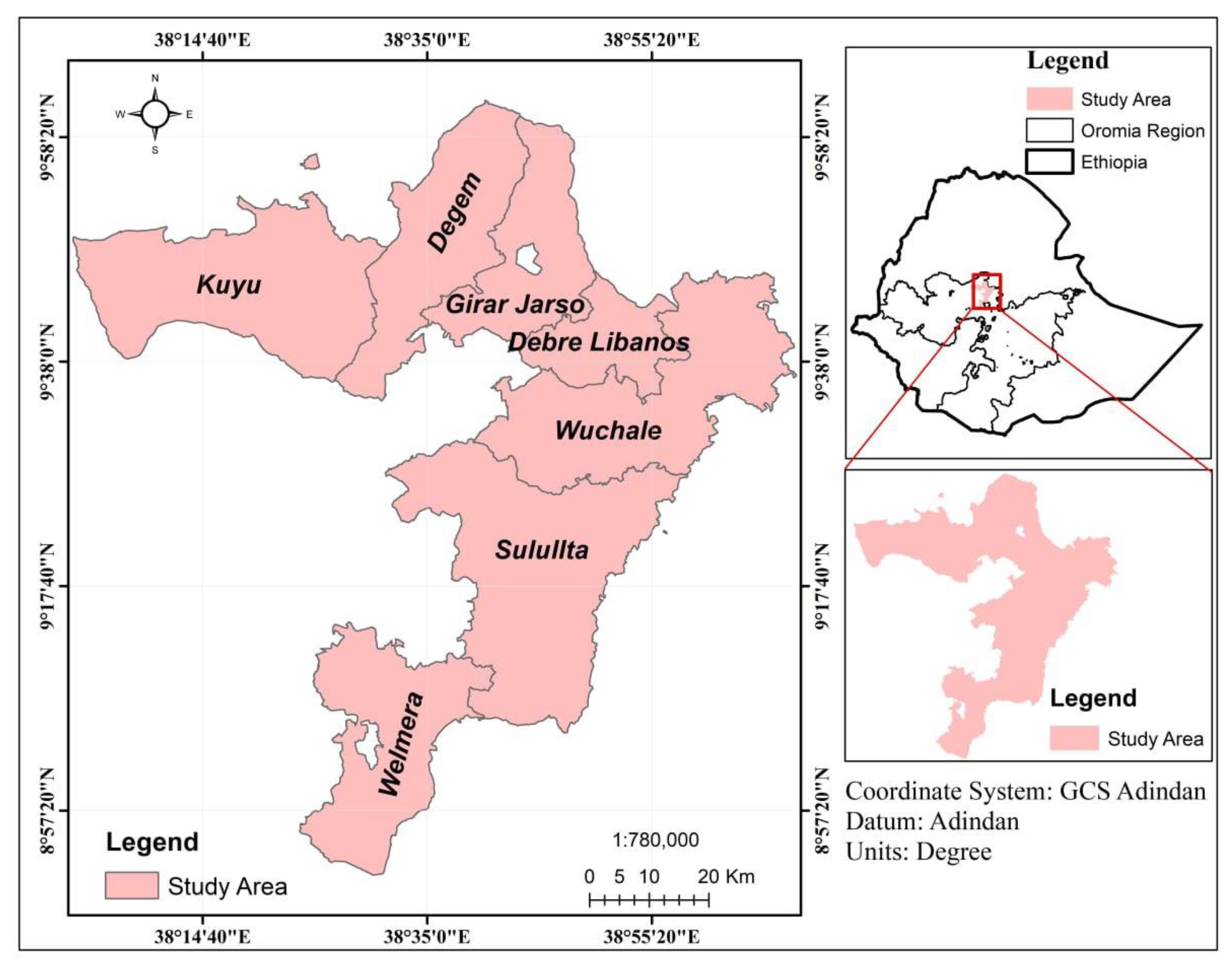

Farm household surveys, animal activity data, laboratory analysis, and secondary sources, used for this study. The data was gathered between February and April 2023 in the four purposively selected districts. We employed a semi-structured questionnaire to gather information from the randomly selected households. Specifically, the questionnaire sought information on livestock holdings, dairy cattle production and reproduction management, feed sources and feeding systems, and MMt and utilization practices. A household survey enumerator expert in livestock production was recruited in each district. Besides, information on agro-ecology, chemical composition of feed, as well as humans and livestock population were obtained from agricultural and rural development offices at the zone and district levels.

Household survey: The survey was conducted between July 2023 and December 2023. In order to monitor seasonal variations in the management of manure and feed resources, the SHFs were visited twice. A team of enumerators experienced in livestock production administered the questionnaire to randomly selected SHF under the supervision of the first author. The purpose of the questionnaire was to gather data regarding the management of dairy cattle herds, livestock holdings, the reproductive and production capacities of animal, the major feed sources in the area, the feeding system, and the management and utilization of manure. Focus groups with six to eight participants were held with SHFs and village leaders in order to triangulate the data obtained from one-on-one interviews with farmers.

Characteristics and performance data: Manure management and utilization practices, as well as data on animal and feed characterization, are critical factors for predicting CH

4 and N

2O [

9]. This study is part of our previous published work estimating enteric methane emissions [

28]. It includes information on cattle breeds and age groups in three farming systems, including pure Holstein Friesian cattle, East African shorthorn zebu cattle, and hybrid cattle. Rural farming systems keep indigenous cattle, while urban and peri-urban farming systems keep pure Holstein cattle and their crosses (

Table 2).

Live weight and growth rate data: The study used data from the Livestock Development Institute's, national dairy cattle database (for urban and per-urban), and survey (for rural) farm to estimate live weight and growth rate of cattle. Live weight was estimated using a heart girth meter and used the regression equation to estimate LW of the animal [

29]. We used secondary sources to determine the average daily weight (ADG) gain because our computed value was unreliable [

30,

31] (

Table 2).

Milk yield and milk chemical composition: The study collected data on milk yield and reproductive performance from LDI and field surveys. Standard 305-day milk yield was determined using test date records [

32,

33,

34]. Rural farms' data was gathered from cooperative unions, milk collectors, and farmers' recalls. Following Van Marle-Köster et al. [

35] milk samples were examined for chemical composition, published in Feyissa et al. [

28] (Supplementary

Table 1).

Composition of seasonal diets and feed characterization: The study assessed the digestibility of common feeds for different animal categories on a farm using data from household surveys and secondary sources [

36,

37,

38]. For the assessment of CH

4 and N

2O, seasonal weighted DMD values were computed to account for seasonal feed baskets and lower uncertainty [

28]. A weighted estimate of DMD was utilized to calculate CH

4 and N

2O amounts for every category and farming system.

Where, ADF = acid detergent fiber

Activity/Walking data: [

27] for East the African dairy approach and the equation provided by the NRC (2001) were used to determine default values for the coefficient of activity data Ca. Grazing animals are primarily kept in small paddocks (private pasture and roadside) and require very little energy to obtain feed (Feyissa et al., 2023). The average grazing distance was estimated using survey data and secondary data from East Africa was used to triangulate [

40,

41]. The detailed information was published by [

28]. The net energy required for an activity is classified by the NRC into two categories: the energy needed for walking and the energy needed for grazing or eating [

39]. Walking on a flat area equals 0.00045 MJ/kg per km, eating equals 0.0012 MJ/kg body weight, and cows grazing on hillsides equals 0.006 MJ/kg per km [

39]

Where NEm is net energy for maintenance, calculated using IPCC (2006), multiplying by 4.20, Mcal was converted to MJ.

Based on the aforementioned concept Ca was computed for the categories of animals.

The following formula is used to compute Ca if the percentage of feed obtained by grazing each day > 0.

Grazing on hilly terrain increases the energy requirements for maintenance by 0.006 Mcal of NEm/kg body weight, since the energy cost is higher than on comparatively level terrain. ME was converted to NEM with an efficiency of 0.7 [

42].

Draft/ploughing data: During the survey, data on the working hours of an ox was collected during survey. The oxen were used to plough for 3.5 months, 7.5 hours each day, then thresh for a month. The work efficiency of Lawrence and Stibbards [

43] is used to compute the energy consumed for traction or ploughing, plus additional energy consumed from traction efforts. Consequently, the energy cost of ploughing was determined to be:

MERP (MJ) = Work hours (h/d) * Dayswork * MLW (kg) * 0.002 (MJ)

Amount of energy expended by an animal: Metabolizable requirements (MER) for growth (MER

G), lactation (MER

L) for lactation animals, maintenance (MER

M), and working (MER

W) or ploughing/traction, if applicable, for each animal (category) were added to get the total energy require for each animal. Equations obtained from CSIRO [

42] were used to compute energy expenditure, as follows:

Maintenance energy requirements (MERM)

Where: K = 1.3 (the intermediate value for Bos Taurus/Bos indicus); S = 1 for females; M = 1; Mean living weight (MLW) varies by season, but dry season lost weight recovers in wet season, and adult animals do not experience weight gain or loss [

44]; A= age in years; M/D = Metabolizable energy content (ME MJ/DM KG) where;

Growth energy requirements (MERG)

Where: EC (MJ/kg) = energy content of the tissue (18MJ/kg) [

42]

Lactation energy requirements (MERL)

ECM (MJ/kg) = energy content of milk MJ/kg

Pre-ruminant calves' (DCMC

L) milk consumption was calculated in accordance with Radostits and Bell (1970). Using the growth rates of 0.362 and 0.340 kg/d for the multipurpose breed and high-grade breed, respectively, the DCM was computed as follows:

Ene

rgy requirements for walking/grazing (MERW)

Where: DIST= average distance covered; LW = live weight; 0.0026 = the energy expended (MJ/LW kg).

Energy requirements for ploughing (MERP)

The daily total energy expenditure (MER Total) for each animal category was computed for each season and farming system:

Where: GE = the gross energy of the diet is assumed to be 18.1MJ/kg DM; 0.81 = Metabolizable energy to digestible energy conversion factor; DMD = Seasonal Weighted Dry Matter Digestibility

Emission factor and daily methane production

Following [

17] and Leitner et al. [

18] methane production (CH

4 manure) was estimated as a function of manure CH

4 emissions factors.

Where: = Total CH4 emissions from MMt in the target area

[Gg CH4 yr-1]; EFT = emission factor for different animal categories

[kg CH4 head-1 yr-1]; NT = number of head of animal category T; T = Animal category

The EF for different animal categories and MMS were estimated as follows:

Where: EFT = Annual CH4 emission factor for animal category T [kg CH4 animal-1 yr-1]; VST = Daily volatile solid excreted from animal category T [kg dry matter animal-1 day-1]; 365 = Annual VS production conversion factor; Bo = Maximum CH4 production capacity for manure produced by animal category T [m3 CH4 kg-1 VS]; 0.67 = Density of CH4 gas to convert from m3 to kg (kg m-3); MCFS,k = Methane conversion factor for MMt system S by farming systems k [%]; MST,S,k = Fraction of the manure from animal category T that is handled using MMt systems S

Daily VS excretion was estimated as a function of DMI in KG [

17,

18].

Where: VS = Volatile solid excreted per animal per day based on dry matter intake and feed digestibility [kg dry matter day

-1]; DMI = Daily dry matter intake [kg animal

-1 day

-1]; DE% = Seasonal digestibility of the feed [%]; ASH = Ash content of manure, default value 0.08 for cattle [

17]; B

o = Production capacity of CH

4 from manure by livestock category

T [m

3 CH

4 kg

-1 VS], IPCC [

17] default values 0.24 for dairy cows and 0.13 for all other dairy and other cattle were used.

2.2.3. Estimation of N2O Emissions from Manure

The direct and indirect N

2O emissions from manure, which occur after excretion, during storage, and during treatment before it is applied to land or used for fuel or construction, were calculated as follows [

17,

18]). Furthermore, there are N

2O emissions from manure after application to soils, but these are not covered in the present study.

Direct N2O emissions: Emission factors for direct N

2O emissions were calculated following [

17] and [

18].

Where: N2OD(MM) = Direct N2O emissions from MMt systems [kg N2O yr-1]; NT = Number of head of animal category T in the region; = Annual N excretion rate per head of animal category T [kg N animal-1 yr-1]; MS T,s = Fraction of Nex for cattle category T in MMt system S; EF3, S = Emission factor for direct N2O emissions from MMt systems S [kg N2O-N kg-1 N]; S = Manure management system; T = Animal category; 44/28 = Conversion of N2O-N to N2O emissions (two N atoms per N2O molecule)

Annual N excretion rates (Nex):

Where:

= Annual N excretion for animal category

T [kg N animal

-1 yr

-1];

= Annual N intake per head of animal of category

T [kg N kg animal

-1 yr

-1];

= Fraction of annual N intake retained by animal of category

T; Total N intake (N

intake) is estimated based on dry matter intake (DMI) and nitrogen content (%N) of the feed

Where: DMI = dry matter intake of the animal [kg animal-1 day-1]; N% = Feed basket N content in percent.

Total nitrogen retention (N

retention) for growth and milk production can be estimated:

Where: N

retention(T) = Daily N retained per animal of category

T [kg N animal

-1 yr

-1]; Milk = milk production [kg animal

-1 day

-1] (applicable to lactating cows only); Milk CP% = Percent of crude protein in milk (applicable to lactating cows only); 6.38 = conversion from milk protein to milk N [kg protein kg

-1 N]; LWG = Live weight gain per animal and season for each livestock category

T [kg day

-1]; 268 and 7.03 = constants from Equation in [

46]; NE

g = Net energy for growth [MJ day

-1]; 6.25 = Conversion from kg dietary protein to kg dietary N [kg protein (kg N)

-1]

Net energy for growth for cattle (NE

g) can be estimated as follows

Where: NE

g = net energy needed for growth [MJ day

-1]; LW mean = mean live weight of the animals in the population for each season [kg], derived from seasonal animal LW measurements “Protocol for cattle enteric methane emissions”; C = coefficient with a value of 0.8 for females, 1.0 for castrates, and 1.2 for bulls [

47]; MW = mature live body weight of an adult female in moderate condition (BCS = 3) [kg]; WG = average daily weight gain of the animals in the population for each season [kg day

-1]

Indirect N2O emissions due to N volatilization from MMS: First, calculate the amount of N that is lost via volatilization of NH

3 and NO

x

Where: NVolatilization–MMS = amount of manure N lost due to volatilization of NH3 and NOx [kg N yr-1]; NT = The number of animals in each category T; = N excretion rate per head of animal category T [kg N animal-1 yr-1]; MST,S= Fraction of annual N excretion for animal category T managed in MMt system S; Frac GasMS = Percentage of manure N from livestock category T that volatilizes as NH3 and NOx from MMt systems S [%]; S = Manure management system; T = Animal category

Then indirect N

2O emissions from N volatilization were calculated as follows:

Where: N

2O

G(MM) = indirect N

2O emissions from N volatilization in MMt [kg N

2O yr

-1]; EF

4 = emission factor for N

2O emitted from atmospheric deposition of N onto soils and water surfaces [kg N

2O-N (kg NH

3-N +NO

x-N)

-1]. The default EF

4 is 0.01 (

Table 8).

Indirect N2O emissions due to N leaching from MMt

The amount of N that is lost via leaching from manure was calculated only for the rainy season.

Where: Leaching–MMS = Amount of manure-N that is lost due to leaching from manure [kg N yr-1]; NT = Number of head of animal category T in the region; = N excretion rate per head of animal category T [kg N animal-1 yr-1];

MS

T,S = Fraction of N

ex for animal category

T in MMt system

S; Fra

Leach MS = % managed manure N losses for animal category

T due to run-off and leaching during storage from MMt systems

S [%, the typical range is 1-20 %], default value (Supplementary

Table 2); S = Manure management system; T = Animal category

Then indirect N

2O emissions from N lost via leaching was calculated as follows:

Where: N

2O

L(MM) = Indirect N

2O emissions due to leaching and run-off of N from MMt in the region [kg N

2O yr

-1]; EF

5 = N

2O emissions factor from leaching and run-off of N [kg N

2O-N (kg N leached)

-1] (

Supplementary Table S1).