1. Introduction

The conventional corporate approach of prioritizing the maximization of shareholder value is being challenged in the new era. Stakeholder theory, introduced by Freeman (1984), has been gaining attention as a different viewpoint on how organizations should interact with society. According to the stakeholder hypothesis, corporations should generate value for all stakeholders and not just for shareholders. The stakeholder hypothesis has fueled the adoption of the ESG framework as a quantitative expression of corporate social responsibility. ESG metrics provide insights into a company's true purpose, societal impact, and long-term prospects, resembling the role of financial metrics in evaluating shareholder performance (Martin et al., 2020).

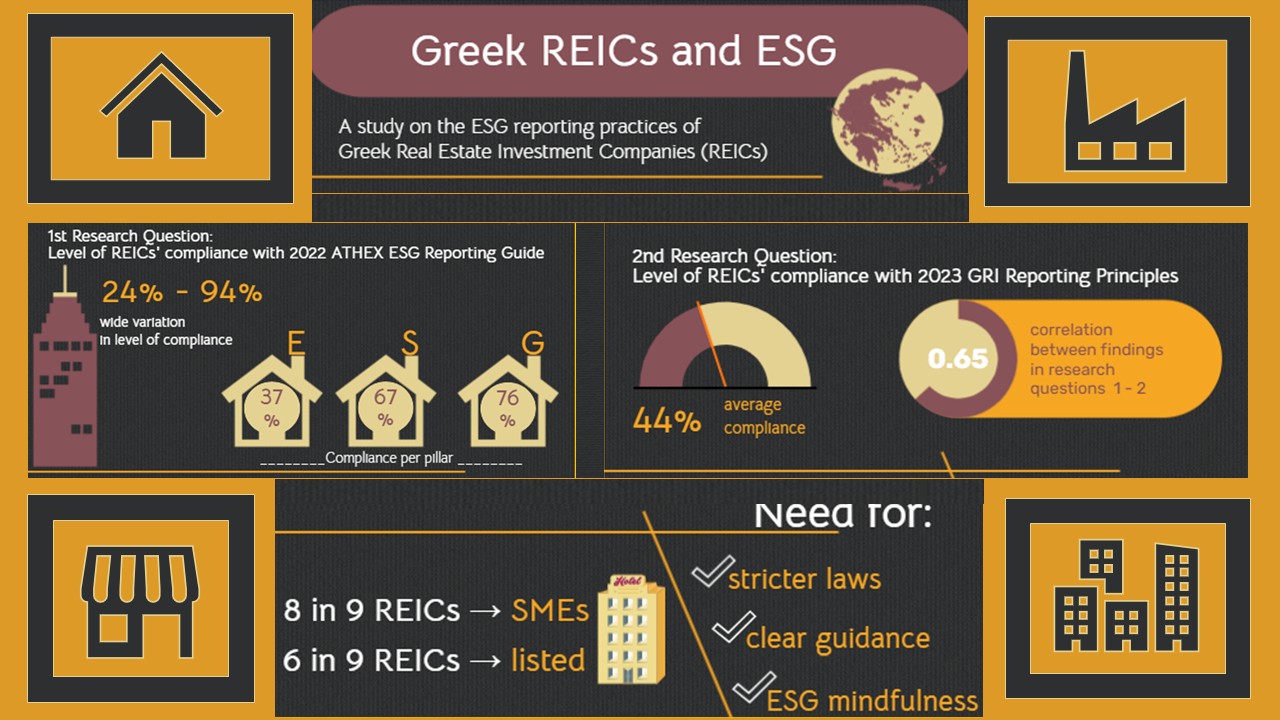

The purpose of our research is to conduct a thorough analysis of the relationship between Greek Real Estate Investment Companies (REICs) and ESG. Our first research question is to investigate the extent to which Greek REICs disclose ESG information. The second research question concerns a qualitative assessment of the findings.

Our motivation stems from the widespread discourse on ESG, particularly environmental awareness, and the frequent introduction of ESG reporting laws in Europe. However, the real question is what happens in practice: have firms truly adopted an ESG-centered mentality? This study aims to uncover the reality, especially considering the significant environmental footprint of the real estate sector. Understanding this gap is crucial for fostering genuine sustainable practices.

The choice to focus on REICs is deliberate due to their unique characteristics. Most REICs qualify as SMEs under EU definitions, exempting them from mandatory ESG reporting. However, Greek REICs must list on the Athens Stock Exchange within two years of establishment, with a possible extension up to 36 months. Once listed, they must meet the minimum mandatory reporting requirements. Thus, it is inevitable that all Greek REICs will eventually comply with European ESG reporting laws for listed companies. This study aims to determine whether being classified as an SME or a listed company significantly impacts the depth of ESG reporting.

To address the first research question, we examine the extent to which each Greek REIC adheres to the core metrics of the 2022 ATHEX ESG Guide. We assign a value of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ depending on their compliance with each metric. For the second research question, which focuses on reporting quality, we use a similar ‘yes’ or ‘no’ approach, this time following the 2023 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Principles.

Our research reveals significant variability in how Greek REICs comply with the 2022 ATHEX ESG Guide, with compliance ranging from 24% to 94%. This variability highlights diverse strategic approaches and shows that neither SME status nor listing status significantly predicts ESG reporting performance. Environmental reporting scores are consistently low, while governance scores are higher due to legal requirements. Social pillar results are mixed, often influenced by legal mandates. Regarding the second research question, we found that most GRI principles are inadequately addressed. REICs tend to highlight their achievements while downplaying challenges. Besides, in most cases ESG data lacks external verification.

Although the REIC sector is relatively small in Greece, our findings have broad implications. They are applicable to most economic fields, given that SMEs constitute the majority of firms nationally, across Europe, and globally. This study underscores the urgent need for action on three fronts. First, implementing more robust legislation to ensure comprehensive ESG reporting, as current lax regulations permit minimal disclosure practices. Second, the quantification of ESG guidelines is essential, as theoretical criteria are too easily manipulated. Lastly, our results challenge the actual level of societal awareness and engagement with ESG issues. In essence, our research reveals a critical gap between ESG theory and practice, calling for a paradigm shift in how firms approach sustainability.

To our knowledge, this is the first academic attempt to inspect the ESG reporting status of REITs/REICs from a clearly qualitative standpoint. Especially in the Greek environment, previous research on REICs has focused primarily on their legal or tax status, financial performance, and prospects, while ESG has been largely neglected. Nevertheless, the main contribution of the study lies in the introduction of a straightforward scorecard methodology to measure ESG compliance, as a tool for future academic use or application by practitioners. Our approach is generalizable to any other type of firm.

This work directly responds to the extensive literature review by Johnson and Schaltegger (2016), who discuss the implementation barriers of ESG management tools for SMEs. They conclude that most ESG models have been created for large companies, so their application to SMEs requires fulfilling certain facilitating criteria. These criteria mainly refer to user-friendliness, cost-effectiveness, and adaptability of the model to each firm’s profile. Verboven and Vanherck (2016) make similar suggestions about the ideal characteristics of an ESG model for SMEs.

The structure of the remainder of this chapter is as follows:

Section 2 is an overview of the regulatory requirements for ESG reporting in Greece.

Section 3 includes a literature review.

Section 4 presents the research design of our case study analysis.

Section 5 offers a discussion of the findings, while

Section 6 summarizes the key conclusions, acknowledges the limitations of the study, and proposes directions for future research.

2. Regulatory Requirements for ESG Reporting in Greece

The European Union (EU) is a global leader in the production of ESG-related legislation, especially concerning the environmental pillar. In 2014, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) led the way for the disclosure of ESG information. It applies to listed firms with over 500 employees; thus, it does not include SMEs. The Taxonomy Regulation, which came into effect in July 2020, further strengthened the NFDR reporting requirements by standardizing measurement and classification definitions for environmentally sustainable economic activities. Compliance with the Regulation requires recognition and mitigation of all activities that exacerbate climate change. The regulation applies to financial market participants in the EU, and to companies already subject to the NFRD, so SMEs remain unaffected.

In addition to these regulations, the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), published in December 2019 and enacted in 2021, foresees a series of sustainability-related disclosures for all financial market participants in the EU, albeit without specified quantitative criteria. ‘Financial market participants’ refer to entities that manufacture financial products, such as investment firms, pension funds, asset managers, insurance companies, banks, venture capital funds, credit institutions offering portfolio management, etc. Most of the times, they are large companies.

The latest developments depict the EU’s willingness to take ESG reporting to a higher level: in 2021, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) extended the scope of the pre-existing ESG reporting requirements to a much wider set of companies, including all large ones (with over 500 employees), publicly traded or not, as well as all firms listed on regulated markets regardless of size. The Directive will also require companies to have their sustainability information assured by an external auditor. The CSRD will be rolled out in three phases. Starting from January 1st, 2024, it will apply to large companies that were already subject to mandatory reporting. In 2025, it will be implemented for large companies not presently subject to the non-financial directive. Finally, on 1st January 2026 the Directive’s application will be enacted for listed SMEs, small and non-complex institutions, and captive insurance undertakings. The SMEs included in the CSDR perimeter will be given a transitional period of two years until January 2028 for the application of the Directive. During this period, they must consider how to abide by the new regulatory requirements. Standards for SMEs have not been specified yet, as they will be tailored to their characteristics.

At a national level, in 2019, the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) outlined ambitious targets and supporting measures to transition Greece towards a net-zero emissions trajectory. In May 2022, the National Climate Law (4936/2022) further reinforced this commitment, setting a clear path towards achieving a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030, an 80% reduction by 2040, and ultimately, net-zero emissions by 2050.1 Moreover, regarding governance, the Hellenic Corporate Governance Code (HCGC), created in 2012 and reviewed in 2021, establishes the CG framework for Greek companies with securities listed on a regulated market. It encompasses previous relevant legislation (laws 4706/2020 and 4548/2018), as well as best practices and recommendations for self-regulation with voluntary compliance.

A comprehensive examination of ESG reporting regulations reveals that SMEs, remain largely exempt from compulsory reporting obligations. The recent EU Regulation (CSDR) represents a positive step towards extending ESG reporting requirements, yet non-listed SMEs and micro-enterprises continue to escape the regulatory net. In Greece, 94.6% of businesses are classified as micro-enterprises employing fewer than 10 individuals, and only approximately 0.6% of all listed firms fall under the definition of SMEs. This disparity implies that the majority of SMEs, excluding the few listed ones, are expected to continue evading the ESG reporting burden. However, all firms, including those currently unaffected by the law, are poised to face mounting scrutiny regarding their ESG performance soon. This could arise from various sources, including financial institutions demanding ESG data as a prerequisite for granting new loans, larger businesses within their value chains refusing to engage with them due to their inadequate ESG performance, or the enactment of stricter ESG reporting regulations.

3. Literature Review

It is noteworthy that academic literature directly addressing ESG reporting quality in the real estate field is scarce. We failed to trace a paper oriented exclusively in a deep qualitative assessment of ESG reporting for REITs/REICs. Ionașcu et al. (2020) reveal a significant gap between the expressed interest in sustainability and actual implementation among real estate companies of various types. Many lack the strategy, culture, and tools to translate commitments into action, so they prefer qualitative descriptions to quantitative key performance indicators (KPIs) in sustainability reporting. Newell et al. (2023) also conclude that the real estate sector faces challenges in ESG benchmarking, with a need for more granular data and focus on climate resilience.

The reason why only a few SMEs choose to report their ESG performance on a voluntary basis can be attributed to various reasons. SMEs obviously lack the expertise to handle ESG issues, which often seem complicated (Lawrence et al., 2006; Aykol and Leonidou, 2014). The scarcity of human and financial resources adds to the problem (Barbagila et al., 2020). Meanwhile, an SME probably underestimates the importance of its very own contribution to the ESG field, or views ESG issues as irrelevant to its core business (Yip and Yu, 2023). Besides, SMEs usually do not draw the attention of the media (Alkatheeri et al., 2023), communities and governments (Blundel et al., 2013), and this translates into less pressure to comply. Additionally, there is evidence that smaller companies receive fewer benefits from taking environmental initiatives (Brammer et al., 2012).

As regulatory frameworks evolve globally, the likelihood of REITs including standardized ESG reporting into their annual reporting is on the rise. Until today, the main body of research has sought to establish a connection between the magnitude of ESG disclosure and financial performance, without reaching a clear consensus. While some studies, such as those by Whelan et al. (2020) and Feng and Wu (2021), suggest a positive association between ESG disclosure and REIT value, others support that CSR practices in REITs do not seem to improve returns (e.g. Westermann et al., 2019). To provide a comprehensive overview, we present our insights categorized by the ESG pillars: environmental, social, and governance.

Starting with the environment, the potential for significant improvements in the environmental performance of the global real estate industry has been repeatedly documented (e.g. Bauer et al., 2011; Ng and Cheng, 2016; Goh et al., 2018). Specifically, within the Greek building sector, the prospects for energy savings are highly promising (Karakosta and Papapostolou, 2023). When addressing environmental concerns, the real estate sector confronts various barriers, such as elevated transaction costs and lack of awareness and expertise (Bienert, 2016). Researchers have also focused on the financial downsides of climate change (Chazanas, 2022; Kuwabara and Cochran, 2023), which include even stranding risk (Hirsch et al., 2019).

Maijala (2020) demonstrated that carbon reduction strategies among European REITs exhibit considerable heterogeneity, ranging from a 34% emissions reduction target to a commitment to carbon neutrality by 2030. Additionally, dedicated reporting tools for real estate have emerged, such as the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM), which was developed with the support of EU to provide a robust foundation for assessing stranding risk. Spanner and Wein (2020) commend the CRREM as the first tool to offer location- and building-type-specific solutions. Other authors, including Leskinen et al. (2020), employ the number of green certificates as a proxy for greenness reporting in a property portfolio. Eichholtz et al. (2009) highlight the widespread use of the Green Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark (GRESB2) rating as a popular greenness indicator. Concurrently with these developments, doubts persist regarding the financial benefits of adopting green practices for REITs (Mariani et al., 2018; Coën et al., 2020).

The importance of social responsibility principles for real estate companies has been evidenced by various researchers, such as Roberts et al. (2007) and Chiang et al. (2019). Erol, Unal, and Coskun (2023) suggest that socially conscious REITs (S-investing) may secure a positive premium for their shares and establish a competitive advantage. This contrasts with their findings on environmental investing, where elevated financial expenses might result in declining market returns. Similarly, Fan et al. (2024) demonstrate a positive relationship between social performance of REITs and their future returns, whereas environmental performance is negatively associated with expected returns.

Our research indicates that the role of women in REITs is the most comprehensively researched aspect of the S pillar of ESG. Jolin (2021) uncovers notable risk-reduction benefits associated with eliminating gender bias. Additionally, Noguera (2020) demonstrates a modest positive correlation between Board gender diversity and REIT performance. Schrand et al. (2018) also affirm that female representation in REIT Boards positively influences market performance after surpassing the 30% threshold.

Finally, the relationship between corporate governance and the financial performance of REITs remains a topic of debate among academia. Numerous studies have found a positive and significant correlation between governance and REIT performance (Ramachandran et al., 2018; Chong, Ting, and Cheng, 2017; Feng et al., 2005). Newell and Lee (2012) highlight corporate governance as the most influential ESG factor affecting REIT performance. Anglin et al. (2012) argue that exceeding the already stringent regulatory requirements for REITs can further enhance investor confidence and, consequently, boost REIT valuations. On the contrary, other academics have argued that the mandatory dividend payout requirement for REITs reduces the importance of corporate governance (e.g. La Porta et al., 2000; Bauer et al., 2009). Further research is needed to identify the specific governance factors that most strongly impact REIT performance.

4. Research Design

While the term Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) does not exist in Greek legislation, a Real Estate Investment Company (REIC) could be considered as a similar entity. REICs are regulated by Law 2778/1999 (‘REIC law’), introduced in 1999. The latest amendment was by law 4646/2019. A Greek REIC must conform to all the formalities set out by Greek Corporate Law (4548/2018), as it follows the legal form of a Société Anonyme (SA). Its operations can only include management of a real estate portfolio in Greece or the European Economic Area, certain highly liquid and short-term investments in bonds or marketable securities, and interests in other SAs with similar purpose. The required minimum share capital amounts to EUR 25 million3.

Our methodology is based on the most recent version (2022) of the Athens Stock Exchange ESG Reporting Guide (hereafter referred to as the 'ATHEX Guide'). In 2018, the Athens Stock Exchange became part of the UN Sustainable Stock Exchanges (SSE) initiative, which provides voluntary guidelines for stock exchanges to encourage sustainability and ESG disclosure. The initial ATHEX Guide was issued in 2019 and underwent a review in 2022. Its metrics are categorized into core, advanced, and sector-specific and are either quantitative or qualitative. Core metrics are recommended for all companies, while advanced metrics allow high-performing companies to showcase their efforts and identify areas for future improvement. Sector-specific metrics are tailored to each industry sector represented in the Athens Stock Exchange. For the first research question, our analysis will exclusively focus on the core metrics, assessing the compliance for each REIC. Specifically, we conduct an extensive analysis of all publicly available ESG information and assign the indicator ‘YES’ if the metric is substantially covered and ‘NO’ if the metric is not addressed at all or partially disclosed. We limit our research to core metrics, as adherence to advanced and sector-specific ones demands significantly greater resources in human capital, time, and money. Therefore, their applicability to Greek REITs, most of which are SMEs, is doubted.

We selected the ATHEX Guide for several reasons. Firstly, it is aligned with all the internationally renowned reporting frameworks and the legislation applicable to Greek firms. Secondly, it is up to date, as its latest version was released in 2022. Additionally, thanks to its simple and clear language, the ATHEX Guide can be applied to companies of all sizes and industries, even though it is primarily oriented towards firms listed on the Athens Stock Exchange. The ATHEX Guide states its suitability for companies that are new to non-financial disclosures (which is usually the case with Greek REITs, as shown below) to direct their efforts towards transparency on ESG matters and increase accountability on sustainability issues.

Table 1 below lists all core metrics that we will examine in the following subsections.

The second research question is to examine the quality of ESG reporting. The major challenge was identifying the appropriate ESG reporting principles as a baseline. Several alternatives exist. Some of the most acknowledged ones are IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards

4, the GRI Standards

5, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP)

6, the TCFD

7 and the United Nations Global Compact

8. Fortunately, most frameworks are in a process of consolidation to stop the so-called ‘alphabet soup’ of so many guides with undiscerning differences between them. We chose the GRI because it is the most widely used, and adopts a clear

9, multi-stakeholder approach, fostering a broad consensus among market participants. In the following analysis, we try to check if compliance with the ATHEX Guide core metrics equals compliance with the GRI principles.

Table 2 presents the main definition of the GRI principles and our classification approach. Like in research question I, we assign a value of ‘YES’ or ‘NO’ per principle for each REIC. Our findings are summarized in the following Section.

5. Results - Discussion

5.1. General Remarks

The main issue arising from our study is that most Greek REICs tend to avoid rigorous reporting practices. This is primarily due to the laxity of existing legal frameworks. These frameworks allow companies to adopt minimal approaches to ESG disclosures at their discretion. As a result, overall transparency and accountability are undermined. This finding underscores the need for more robust legislation to ensure comprehensive and consistent ESG reporting among Greek REICs. Our findings are particularly concerning given that the EU has been introducing ESG-related legislation for almost two decades, yet progress appears alarmingly slow. Similar issues are likely to be present in the ESG reporting status of other sectors currently unaffected by law.

In addition to the loose regulations, we found that the ambiguous definitions of certain ESG metrics (research question 1) and principles (research question 2) can enable firms to ostensibly demonstrate compliance. Even when reporting is well-intentioned, the vagueness of the guidance can lead firms to report unreliable data. The anticipated worldwide standardization of reporting standards aims to provide investors with consistent, comparable, and decision-useful information. Newell et al. (2023) highlight that, especially regarding ESG benchmarking in real estate, granularity is needed around climate resilience and climate risk performance, outcomes, and impacts.

In hindsight, perhaps the most disappointing realization is that despite the theoretical rise in societal education levels and easier access to information, ESG awareness remains low. We would expect corporate leaders to act as advocates of sustainable transformation rather than hiding behind opaque guidelines. Climate change is irreversible unless we proactively control it. Especially actors in the real estate market encounter high expectations for transparency and reporting on ESG matters.

Regarding the first question, the findings of our research are presented in

Table 3. They reveal a significant variability in the coverage percentages of the ATHEX Guide’s core metrics across all sampled REICs. Compliance ranges from 24% to 94% with an average of 64.50%. This wide range underscores the diverse strategic approaches adopted by different firms and highlights that SME status does not necessarily indicate a certain level of ESG reporting performance. The distinction between listed and non-listed REICs is not a significant predictor of ESG reporting coverage either: the average coverage percentage for listed REICs (61.67%) is only marginally higher than that of non-listed REICs (56%). This suggests that the legal and market pressures for REICs to upgrade their ESG reporting standards are not particularly strong, even for those listed on the stock exchange. Instead, each REIC appears to formulate its own approach in determining the extent to which it leverages the flexibility provided by the loose legal framework. The remarkable performance of the non-listed SME E corroborates the ATHEX Guide's assertion that its applicability extends beyond publicly traded companies, serving as a valuable resource for businesses of all sizes.

A noteworthy observation is the consistently low scores assigned to the environmental pillar. The results are potentially attributable to the technical complexities involved in accurately quantifying greenhouse gas emissions. In contrast, REICs exhibit high performance in governance reporting, which may be attributed to the legal requirement10 for société anonyme companies to disclose information regarding the size and composition of their Boards of Directors. In the social pillar, we encounter mixed results. However, they are inflated upwards by metric C-S3 (Female employees in management positions), where disclosure is mandated by law11, and C-S7 (Collective bargaining agreements), which are absent by default due to REICs' small staff size. The remarkably low percentage for metric C-S5 (employee training), where reporting is easy and straightforward, signals the widespread reluctance among companies to engage in ESG reporting. Regarding other low-scoring metrics, we believe that REICs might avoid reporting because they encounter difficulties in dealing with entirely qualitative measurement guidelines (e.g. C-S1 Stakeholder engagement) or lack the resources to comply with the requirement (e.g. C-S8 Supplier assessment, as SMEs are typically price takers without bargaining power).

We move on with the second research question: is the sampled ESG reporting in agreement with the GRI reporting principles?

Table 4 presents our results.

Accuracy and

verifiability are jointly examined, with a value of ‘Yes’ if the released information has been externally verified. Except for REIC C, all REICs' ESG data remains externally unverified, raising concerns about the validity of the statements. Results are also disappointing regarding

balance. REICs primarily focus on highlighting their ESG-related achievements, such as awards and building certifications. At the same time, they conceal mistakes, omissions or delayed response to ESG challenges, by using generic phrases such as ‘

the opportunities, risks and uncertainties in the business environment are challenges that organizations must face during their daily operation’. The limited awareness of their crucial role in environmental protection is reflected in one REIC’s statement that its environmental footprint is not particularly high, as it does not create significant waste. It should be mentioned that the real estate sector is responsible for consuming over 40% of global energy annually, while buildings contribute to 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions and use around 40% of raw materials. The responsibility of the REIT industry is magnified by the fact that the world is currently off track to meet the so-called ‘Paris goal’ to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

In contrast to the observed shortcomings in accuracy/verifiability and balance, all REICs demonstrate a loose adherence to clarity by providing ESG information in a readily accessible online format and using language that is comprehensible to even non-experts. Still, a more stringent evaluation would reveal room for improvement. Some REICs present most ESG data only in Greek, excluding all foreign-speakers. Additionally, the use of diverse reporting channels, such as separate Sustainability Reports and piecemeal ESG-related information scattered across financial statements and corporate websites, could obscure the overall ESG message and hinder stakeholders' ability to fully comprehend the firm's ESG commitment. Accessibility to information is also questioned when it comes to policies, since some of them are only mentioned, without access to the content, while others are available online.

Codifying compliance with the principle of comparability proved challenging. For REICs that do not publish a separate Sustainability Report, the available ESG data in the financial statements are normally few, and year-to-year comparisons are cumbersome. Conversely, REICs with Sustainability Reports facilitate comparisons, as all data are presented compared to the previous year. Still, up to now they have published only one or two Sustainability Reports, and this time frame cannot facilitate meaningful comparisons: firms may have exhibited abnormal ESG performance during the COVID-19 pandemic which should not be attributed to a designated strategy (e.g. low emissions resulting from mandatory lockdowns). Besides, comparisons among REICs’ emissions are also impeded by the varying degree of control that each REIC has over its tenants.

To assess compliance with the principle of

completeness, we established a threshold of at least 60% of all core metrics being covered (indicated as 'Yes' in

Table 3). Only 56% of the REICs met this criterion, highlighting the need for further progress in integrating ESG considerations into their strategic planning and daily operations. This relatively low score serves as justification for our decision to refrain from evaluating advanced or sector-specific metrics during the design process.

REICs that publish Sustainability Reports received a positive assessment with respect to the principle of sustainability context; we noticed that the impacts of a firm's activities within the broader framework of sustainable development can be effectively analyzed only in dedicated Sustainability Reports, given the limited space typically allocated for ESG topics within financial reports. Finally, about timeliness, all REICs received a ‘Yes’ value because their ESG-related information was released within the timeframe of 12 months of the reporting period, which is a generally accepted standard for financial reporting, too.

By combining the right columns in

Table 3 and

Table 4, we find that the correlation coefficient between compliance with the ATHEX Guide and the GRI principles is 0.65. In other words, REICs that follow the ATHEX Guide also tend to apply the GRI reporting principles. Nevertheless, this positive relationship could be stronger: in some cases, the information is typically reported but fails the quality control tests of our research. This suggests that while adherence to the ATHEX Guide is a step in the right direction, it does not guarantee high-quality ESG reporting. The variability in compliance with the ATHEX Guide's core metrics highlights the need for more stringent and clear guidelines to ensure that ESG reporting is not only comprehensive but also reliable and meaningful. This connection underscores the importance of addressing both the breadth and depth of ESG reporting standards to achieve true transparency and accountability.

Incomplete ESG disclosure poses unique risks for REITs due to their significant environmental impact and reliance on investor trust. Poor ESG reporting can lead to higher costs of capital and insurance, and reduced access to financing. Incomplete disclosures can attract regulatory scrutiny and potential penalties. Besides, poor ESG disclosure can damage a REIT's reputation, making it less attractive to socially conscious investors and tenants. These factors underscore the critical importance of comprehensive ESG disclosures for REITs to maintain financial stability and investor confidence.

From our research, it is revealed that Greek REICs are prone to greenhushing, the practice of deliberatively under-communicating about their environmental progress (Ginder et al., 2021). We also find strong evidence of greenwishing, i.e. making false or exaggerated environmental claims that do not align with a company's actions (Austin, 2019). As stated in the literature review, ESG disclosure and REIT value are proven to be positively associated. Thus, another serious consequence for REITs that fail to fully and properly disclose their ESG practices could be a fall in value. Also, REITs face the significant risk of their real estate assets becoming stranded assets as a consequence of subpar ESG performance. Moreover, empirical evidence indicates that properties with superior energy efficiency exhibit elevated occupancy rates and extended lease terms, both of which are critical determinants of stable income streams. Besides, sustainable buildings are associated with healthier indoor environments, a factor increasingly valued by contemporary tenants. From an investor's perspective, the potential for both robust financial returns and positive social impact presents a compelling investment proposition.

5.2. A Roadmap for Progress

In this subsection, we endeavor to provide a concise framework to guide Greek REITs in enhancing their ESG compliance, both quantitatively and qualitatively. To stay aligned with the first research question, we are based again on the ATHEX Guide. To ensure applicability, we focus on the steps/metrics which are the easiest to follow.

To measure absolute reductions in Scope 1 and 2 emissions, the total amount of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) can be calculated. To measure intensity reduction, these emissions can be normalized by dividing them by a relevant financial indicator. For REITs, a suitable normalization factor is the total covered area of all buildings. This approach allows for comparisons across different-sized portfolios and assesses energy efficiency improvements. Greenhouse emissions are probably one of the easiest ESG goals to monitor and document. Energy is usually bought (e.g. natural gas or electricity), so total consumption can be tracked directly from the bill sent by the utility company. Most probably it will be counted in kilowatts and not megawatts. The conversion to CO2 can be based on acknowledged conversion tools, such as the GHG Emissions Calculator offered by the UN, if the same conversion factor is used overtime, to ensure comparability. Similar conversion protocols can be used if a firm burns oil.

There can be mobile sources of emissions, too, such as vehicles owned by the firm (Scope 1). Fuel usage can be measured from gas station receipts, and mileage can be determined from vehicle records. One challenge here is that the firm owner often uses its car for both personal transitions and business. In this case, the solution might be to estimate the average distance covered for business reasons and then calculate total consumption based on the official technical specifications provided by the vehicle manufacturer.

There is also much room for optimizing energy efficiency in Greek REICs. Shifting from petroleum to natural gas or electricity is recommended, with a strategic move towards renewable energy being the best option. Government subsidies can support REICs in installing photovoltaic parks and purchasing electric vehicles. Other initiatives include simple energy-saving measures like using LED bulbs and adjusting air-conditioning/heating settings.

Following our roadmap, we now turn our attention to the social dimension of ESG. Stakeholder engagement is fundamental, with a focus on employees and clients. Effective engagement involves regular communication, feedback mechanisms, and addressing concerns. Initially, qualitative measures suffice, but quantitative metrics should be integrated over time to assess impact.

Gender diversity is crucial for social responsibility. Despite progress in female employment rates in Greece, addressing the motherhood pay gap and promoting women in leadership positions remain vital. Policies such as flexible work arrangements, parental leave, and mentorship programs can significantly enhance gender equality.

Employee turnover, a key indicator of organizational health, is influenced by factors like compensation, work-life balance, and career development opportunities. Effective human resource management practices, including performance management, training and development programs, and recognition systems, can reduce turnover rates and increase employee satisfaction.

Employee training is essential for maintaining a skilled workforce. REICs can leverage public training programs and online courses as cost-effective strategies. Prioritizing training initiatives that address skill gaps and future industry trends can enhance competitiveness.

Human rights considerations are integral to responsible business practices. Developing and implementing a human rights policy aligned with international standards is essential. Regular monitoring and evaluation, coupled with mechanisms for addressing human rights concerns, ensure compliance and mitigate risks.

Finally, regarding governance, REICs can gain fresh perspectives and improve their decision-making processes, even if they have formal BoDs, by establishing an advisory board. This advisory board can provide expert advice on various aspects of the business, including legal, financial, and marketing matters. As for sustainability REICs can implement simple approaches, such as regular team meetings to discuss sustainability issues, thanks to their relatively small size Engaging with stakeholders can also help identify material sustainability issues and develop appropriate strategies to address them.

While materiality assessment can be challenging for REICs, following industry-specific guidelines, and engaging with stakeholders can help streamline the process. Developing a sustainability policy is also a key step in formalizing the REIC’s commitment to ESG. This policy should outline the company's ESG goals, strategies, and performance targets. As they probably lack specialized human resources in the field due to their size, Greek REICs can seek external support from consultants or industry associations to develop a comprehensive sustainability policy.

Data security is a growing concern for businesses of all sizes, including Greek REICs. As a relatively new industry, REICs are heavily reliant on digital systems, making them particularly vulnerable to cyber threats. Implementing robust security measures, such as strong passwords, regular software updates, and employee training, is crucial to protecting sensitive information.

6. Conclusions

In this article, we conduct an in-depth case study analysis of the ESG reporting practices of all Greek REICs (Real Estate Investment Companies). Our investigation focuses on two key aspects: the level of compliance with the 2022 Athens Stock Exchange ESG Reporting Guide and the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) reporting principles. With respect to the first question, the average REIC adheres to approximately 65% of all core ESG metrics. However, compliance rates vary considerably across the three ESG pillars: environment (37%), society (67%), and governance (76%). Environmental disclosures prove to be the most challenging ones to track, particularly given the REICs' limited or no control over their tenants' environmental practices. In contrast, the high compliance rate for governance metrics can be attributed to the existence of relevant legislation.

As for the second research question, our case study uncovered a series of reporting discrepancies from the GRI principles. Specifically, concerning accuracy, verifiability, and balance, the sampled firms demonstrate an unwillingness to enhance reporting quality. Completeness is also relatively low, and could be easily improved through easily trackable disclosures such as the number of training hours. A deeper examination of the collected data leaves us with an impression of greenwashing: REICs tend to overstate their future initiatives without typically making concrete and time-bound commitments. The publication of a distinct Sustainability Report is generally associated with higher levels of performance in both research questions.

The findings from our research on Greek REITs can be extrapolated to other European countries with a similarly limited number of active REITs, such as Hungary (2), Ireland (1), Germany (6), the Netherlands (4), and Portugal (2). Given that all EU countries adhere to the same regulatory framework, it is pertinent to investigate whether these nations exhibit higher compliance levels compared to Greece. This comparative analysis could provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of the EU's regulatory environment across different member states.

Despite our meticulous efforts, the study presents several limitations that warrant acknowledgment. The most prominent one is the limited sample size, despite encompassing the entire population of REICs operating in Greece. A case study on a broader range of companies would yield more robust insights into their ESG-related attitudes. Another limitation lies in the difficulty of assigning a categorical value of 'Yes' or 'No' in certain instances, particularly for specific qualitative metrics outlined in the ATHEX Guide. We suggest that the ATHEX Guide should establish more precise measurement criteria for metrics presented in an overly theoretical manner. The quantification of all metrics could even enable the assessment of compliance based on a scoring system, providing more refined results. Furthermore, the absence of external verification in almost all REICs partially affects the creditworthiness of our findings.

Our study paves the way for several avenues for future research. For instance, a subsequent study could delve into advanced or even sector-specific ATHEX Guide’s metrics for those REICs already demonstrating high levels of reporting performance in core metrics. Another research idea would be an extensive robustness check of our findings in the second research question, by altering the threshold of 60% to assess compliance with the principle of completeness. Future researchers could also explore innovative approaches to assist REICs with ESG reporting through the utilization of artificial intelligence. Finally, conducting similar research on other types of Greek companies would be intriguing to determine whether REICs follow a general trend or exhibit idiosyncratic characteristics.

References

- Alkatheeri, H.B., Markopoulos, E., and Hamdan Al-qayed, H. (2023). An organizational and operational capability and maturity assessment for SMEs in emerging markets towards the ESG criteria adaptation. Human Interaction and Emerging Technologies (IHIET 2023): Artificial Intelligence and Future Applications.

- Anglin, P.; Edelstein, R.; Gao, Y.; Tsang, D. What is the Relationship Between REIT Governance and Earnings Management?. J. Real Estate Finance Econ. 2012, 47, 538–563. [CrossRef]

- Austin, Duncan (2019). Greenwish: the wishful thinking undermining the ambition of sustainable business. Real-world economics review, 90(9), pp. 47-64.

- Aykol, B.; Leonidou, L.C. Researching the Green Practices of Smaller Service Firms: A Theoretical, Methodological, and Empirical Assessment. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2014, 53, 1264–1288. [CrossRef]

- Barbagila, M. [et al.] (2020). Supporting SMEs in sustainable strategy development post-Covid-19: Challenges and policy agenda for the G20. G20 Insights.

- Bauer, R.; Eichholtz, P.; Kok, N. Corporate Governance and Performance: The REIT Effect. Real Estate Econ. 2010, 38, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R., Eichholtz, P., Kok, N. and Quigley, J.M., 2011. How Green is Your Property Portfolio? The Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark. Rotman International Journal of Pension Management, 4(1), pp.34–43.

- Bienert, S., 2016. Climate Change Implications for Real Estate Portfolio Allocation: Industry Perspectives, Urban Land Institute.

- Blundel, R.; Monaghan, A.; Thomas, C. SMEs and environmental responsibility: a policy perspective. Bus. Ethic- A Eur. Rev. 2013, 22, 246–262. [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Hoejmose, S.; Marchant, K. Environmental Management in SMEs in the UK: Practices, Pressures and Perceived Benefits. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 423–434. [CrossRef]

- Chazanas, A., 2022. The Impacts Of Climate Change On The Real Estate Market, Forbes.

- Chiang, K.C.H.; Wachtel, G.J.; Zhou, X. Corporate Social Responsibility and Growth Opportunity: The Case of Real Estate Investment Trusts. J. Bus. Ethic- 2017, 155, 463–478. [CrossRef]

- Chong, W.L.; Ting, K.H.; Cheng, F.F. Impacts of corporate governance on Asian REITs performance. Pac. Rim Prop. Res. J. 2016, 23, 75–99. [CrossRef]

- Coën, A., Lecomte, T., and Abdelmoula, M., 2020. The financial performance of green REITs revisited. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 24(1), pp. 1-18.

- Bauer, R.; Eichholtz, P.; Kok, N. Corporate Governance and Performance: The REIT Effect. Real Estate Econ. 2010, 38, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Erol, I.; Unal, U.; Coskun, Y. ESG investing and the financial performance: a panel data analysis of developed REIT markets. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 85154–85169. [CrossRef]

- European Public Real Estate Association (EPRA), 2023. Global REIT Survey for 2023.

- Feng, Z.; Ghosh, C.; Sirmans, C.F. How Important is the Board of Directors to REIT Performance?. J. Real Estate Portf. Manag. 2005, 11, 281–293. [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.Y.; Shen, J.; Hui, E.C.; Cheng, L.T. ESG components and equity returns: Evidence from real estate investment trusts. Int. Rev. Financial Anal. 2024, 96. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wu, Z. ESG Disclosure, REIT Debt Financing and Firm Value. J. Real Estate Finance Econ. 2021, 67, 388–422. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E., 1984. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1(1).

- Ginder, W.; Kwon, W.-S.; Byun, S.-E. Effects of Internal–External Congruence-Based CSR Positioning: An Attribution Theory Approach. J. Bus. Ethic- 2019, 169, 355–369. [CrossRef]

- Goh, C. L., Ong, B. S., and Kwek, S. T., 2018. Building a sustainable future: The potential of green real estate to transform cities and society. Journal of Property Investment and Finance, 36(4), pp. 321-339.

- Hirsch, J.; Spanner, M.; Bienert, S. The Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor—Developing a Framework for Science-based Decarbonizing and Reducing Stranding Risks within the Commercial Real Estate Sector. J. Sustain. Real Estate 2019, 11, 174–190. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency, n.d. Greece 2023: Energy Policy Review – Event.

- Ionașcu, E.; Mironiuc, M.; Anghel, I.; Huian, M.C. The Involvement of Real Estate Companies in Sustainable Development—An Analysis from the SDGs Reporting Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 798. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Two Decades of Sustainability Management Tools for SMEs: How Far Have We Come? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 481–505. [CrossRef]

- Jolin, J., 2021. Female directors and corporate risk taking: A global analysis. Journal of Corporate Finance, 62, pp. 1-14.

- Karakosta, C.; Papapostolou, A. Energy efficiency trends in the Greek building sector: a participatory approach. Euro-Mediterranean J. Environ. Integr. 2023, 8, 3–13. [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-De-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Agency Problems and Dividend Policies around the World. J. Finance 2000, 55, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S. R. E., Collins, E., Pavlovich, K., and Arunachalam, M. (2006). Sustainability practices in SMEs: The case of New Zealand. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(4), 242-257.

- Leskinen, N.; Vimpari, J.; Junnila, S. A Review of the Impact of Green Building Certification on the Cash Flows and Values of Commercial Properties. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2729. [CrossRef]

- Maijala, N. (2020). Carbon strategies among European real estate investment trusts. https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/47154.

- Mariani, M.; Amoruso, P.; Caragnano, A.; Zito, M. Green Real Estate: Does It Create Value? Financial and Sustainability Analysis on European Green REITs. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 13, 80. [CrossRef]

- Martin, B., Brindisi, C. and Kay, I., 2020. The Stakeholder Model and ESG. The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance.

- Kuwabara, T. and Cochran, L. 2023. MIT Center for Real Estate advances climate and sustainable real estate research agenda Projects, publications, and academia - industry networks produce pathways for the real estate industry to address the climate crisis.

- Newell, A., and Lee, D., 2012. The influence of corporate social responsibility factors and financial factors on REIT performance in Australia. Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(3), pp. 483-501.

- Newell, G.; Nanda, A.; Moss, A. Improving the benchmarking of ESG in real estate investment. J. Prop. Invest. Finance 2023, 41, 380–405. [CrossRef]

- Ng, N., and Cheng, H., 2016. The role of green buildings in sustainable real estate portfolio management. Journal of Property Investment and Finance, 34(2), pp. 156-175.

- Noguera, J. A., 2020. Women directors’ effect on firm value and performance: The case of REITs. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 52(4), pp. 443-462.

- Ramachandran, J., Chen, K.K., Subramanian, R., Yeoh, K.K., and Khong, K.W., 2018. Corporate governance and performance of REITs: A combined study of Singapore and Malaysia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 33 (6/7), pp. 586-612.

- Roberts, C.; Rapson, D.; Shiers, D. Social responsibility: key terms and their uses in property investment. J. Prop. Invest. Finance 2007, 25, 388–400. [CrossRef]

- Schrand, L.; Ascherl, C.; Schaefers, W. Gender diversity and financial performance: evidence from US REITs. J. Prop. Res. 2018, 35, 296–320. [CrossRef]

- Spanner, M.M.; Wein, J. Carbon risk real estate monitor: making decarbonisation in the real estate sector measurable. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2020, 13, 277–299. [CrossRef]

- Verboven, H.; Vanherck, L. Sustainability management of SMEs and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Nexus Forum 2016, 24, 165–178. [CrossRef]

- Westermann, J., Niblock, A., and Kortt, M., 2019. Does it pay to be responsible? Evidence on corporate social responsibility and the investment performance of Australian REITs. Journal of Property Investment and Finance, 37(6), pp. 491-508.

- Whelan, T., Atz, U., Bruno, C., and Sundaram, S., 2020. ESG and financial performance: Uncovering the relationship by aggregating evidence from 1,000 plus studies. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 33(4), pp. 82-97.

- Yip, A.W.H.; Yu, W.Y.P. The Quality of Environmental KPI Disclosure in ESG Reporting for SMEs in Hong Kong. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3634. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

2022 ATHEX ESG Guide's core metrics.

Table 1.

2022 ATHEX ESG Guide's core metrics.

| ESG Classification |

ID |

Metric title |

| Environmental |

C-E1 |

Scope 1 emissions |

| |

C-E2 |

Scope 2 emissions |

| |

C-E3 |

Energy consumption and production |

| Social |

C-S1 |

Stakeholder engagement |

| |

C-S2 |

Female employees |

| |

C-S3 |

Female employees in management positions |

| |

C-S4 |

Employee turnover |

| |

C-S5 |

Employee training |

| |

C-S6 |

Human right policy |

| |

C-S7 |

Collective bargaining agreements |

| |

C-S8 |

Supplier assessment |

| Governance |

C-G1 |

Board composition |

| |

C-G2 |

Sustainability oversight |

| |

C-G3 |

Materiality |

| |

C-G4 |

Sustainability policy |

| |

C-G5 |

Business ethics policy |

| |

C-G6 |

Data security policy |

Table 2.

Research design regarding compliance with GRI Principles.

Table 2.

Research design regarding compliance with GRI Principles.

| GRI principles * |

Definition of principle * |

Criteria for indication 'Yes' in the sampled reports |

| i. Accuracy |

The organization shall report information that is correct and sufficiently detailed to allow an assessment of the organization’s impacts. |

‘Yes’ if the released information has been externally verified (combined examination with Verifiability) |

| ii. Balance |

The organization shall report information in an unbiased way and provide a fair representation of the organization’s negative and positive impacts. |

‘Yes’ if the company explicitly states its problem areas concerning ESG |

| iii. Clarity |

The organization shall present information in a way that is accessible and understandable. |

‘Yes’ if the information is available online and expressed without excessive terminology |

| iv. Comparability |

The organization shall select, compile, and report information consistently to enable an analysis of changes in the organization’s impacts over time and an analysis of these impacts relative to those of other organizations. |

‘Yes’ if the firm has been releasing a Sustainability Report at least since 2020 with reference to 2019 ** |

| v. Completeness |

The organization shall provide sufficient information to enable an assessment of the organization’s impacts during the reporting period. |

‘Yes’ if at least 60% of core metrics are sufficiently reported (i.e. indication 'YES' in Section 5 Table 3) |

| vi. Sustainability context |

The organization shall report information about its impacts in the wider context of sustainable development. |

‘Yes’ if the firm has released a distinct Sustainability Report and not pieces of ESG information scattered inside the financial statements |

| vii. Timeliness |

The organization shall report information on a regular schedule and make it available in time for information users to make decisions. |

‘Yes’ if the time lag between the end of the reporting period and the release of ESG information is less than 12 months |

| viii. Verifiability |

The organization shall gather, record, compile, and analyze information in such a way that the information can be examined to establish its quality. |

‘Yes’ if the released ESG information has been externally verified (combined examination with Accuracy) |

Table 3.

2022 ESG ATHEX Guide's core metrics disclosure per REIC.

Table 3.

2022 ESG ATHEX Guide's core metrics disclosure per REIC.

| REIC |

SME |

Listed |

Environment ** |

Society |

Governance |

% ‘Y’ |

| C-E1 |

C-E2 |

C-E3 |

C-S1 |

C-S2 |

C-S3 |

C-S4 |

C-S5 |

C-S6 |

C-S7 |

C-S8 |

C-G1 |

C-G2 |

C-G3 |

C-G4 |

C-G5 |

C-G6 |

| A |

Yes |

Yes |

N |

N |

N |

Ν |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

53 |

| B |

Yes |

Yes |

N |

N |

N |

Ν |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

24 |

| C |

Yes |

Yes |

Ν |

Ν |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

88 |

| D |

Yes |

Yes |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

94 |

| E |

Yes |

No |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

Ν |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

N |

Υ |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

82 |

| F |

Yes |

No *

|

Ν |

Ν |

Ν |

Ν |

Ν |

Υ |

N |

N |

Υ |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

35 |

| G |

Yes |

Yes |

Ν |

Ν |

Ν |

Ν |

Ν |

Υ |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Υ |

Υ |

Υ |

41 |

| H |

Yes |

No *

|

Ν |

Ν |

Ν |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

76 |

| I |

No |

Yes |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

88 |

| % ‘Y’ |

|

|

33 |

33 |

44 |

44 |

67 |

100 |

56 |

44 |

78 |

100 |

44 |

100 |

67 |

56 |

89 |

89 |

55 |

65 |

% per pillar

E-S-G

|

|

|

37 |

67 |

76 |

|

Y: Sufficient disclosure (‘Yes’)

N: Partial or no disclosure (‘No’) |

|

Table 4.

Compliance with the GRI reporting principles.

Table 4.

Compliance with the GRI reporting principles.

| REIC |

Accuracy - Verifiability |

Balance |

Clarity |

Comparability |

Completeness |

Sustainability context |

Timeliness |

% Y |

| A |

N |

N |

Υ |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

29 |

| B |

N |

N |

Υ |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

29 |

| C |

Υ |

N |

Υ |

N |

Y |

Υ |

Y |

71 |

| D |

N |

N |

Υ |

N |

Y |

Υ |

Y |

57 |

| E |

Ν |

N |

Υ |

N |

Y |

Υ |

Y |

57 |

| F |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

29 |

| G |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

29 |

| H |

N * |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

43 |

| I |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

Υ |

Y |

57 |

| % Y |

11 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

56 |

44 |

100 |

44 |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

GRESB is an independent organization that provides validated ESG performance data and peer benchmarks for investors and managers. The overall score stems from numerous ESG data points, including performance indicators such as GHG emissions, waste and energy and water consumption. |

| 3 |

For further information, please see the Global REIT Survey for 2023, issued by the European Public Real Estate Association (EPRA). |

| 4 |

The IFRS Foundation has established a set of disclosure standards as a response to the challenges of voluntary sustainability-related standards and requirements that can add cost, complexity, and risk to both companies and investors. In its effort to promote global homogeneity in reporting, the IFRS Foundation has absorbed other entities which promoted their own ESG standards (e.g. SASB standards and the CDSB Framework). |

| 5 |

The GRI is an independent, international organization that helps businesses and organizations to practice sustainability reporting. The GRI Standards offer a structured reporting system that is transparent to stakeholders and other interested parties. The GRI and the IFRS Foundation have signed a Memorandum of Understanding, to ensure complementary and interoperable standards. |

| 6 |

CDP defines itself as ‘a not-for-profit charity that runs the global disclosure system for investors, companies, cities, states and regions to manage their environmental impacts’. Entities respond to a series of questionnaires and then get letter-grade scores in each area. CDP is to integrate its company questionnaires with IFRS standards from 2024., |

| 7 |

The goal of the global organization TCFD is to create a set of suggested climate-related disclosures that businesses and financial institutions can use to communicate their financial risks associated to climate change to shareholders, investors, and the general public. Although the TCFD remains an autonomous entity, it has collaborated with the IFRS so that companies that apply the IFRS Standards be following the TCFD recommendations. |

| 8 |

As the "world's largest corporate sustainability initiative," the UN Global Compact focuses on coordinating business operations and plans with a set of ten principles about human rights, labor standards, the environment, and anti-corruption measures. Each year, participating businesses submit report outlining their compliance with the principles. the Global Compact’s reporting framework is designed to complement existing reporting initiatives, including those based on the IFRS. |

| 9 |

For example, the CDP is vague about the frameworks used, while TCFD guidelines hinder comparability over different organizations and industries. |

| 10 |

Laws 4548/2018 and 4706/2020, incorporated in the Hellenic Corporate Governance Code. |

| 11 |

Article 45 of Law 4548/2018. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).