Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

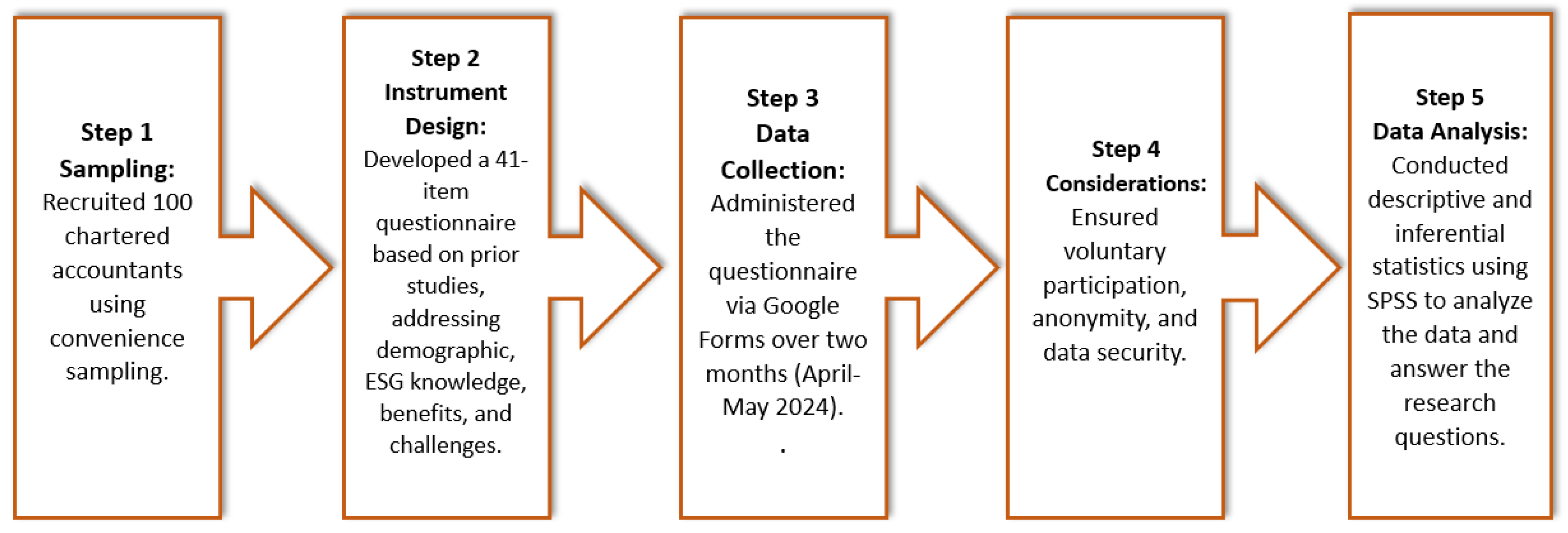

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

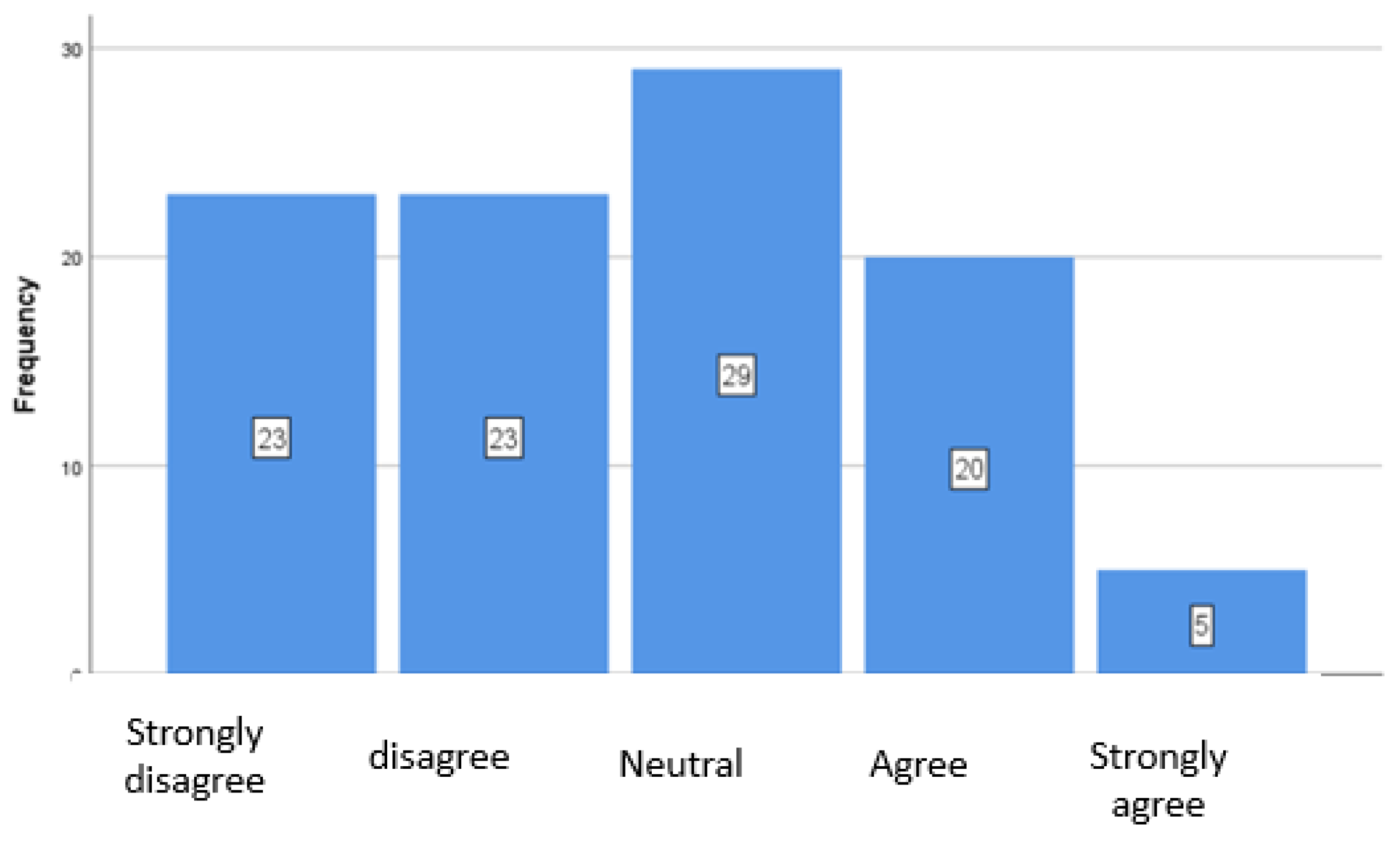

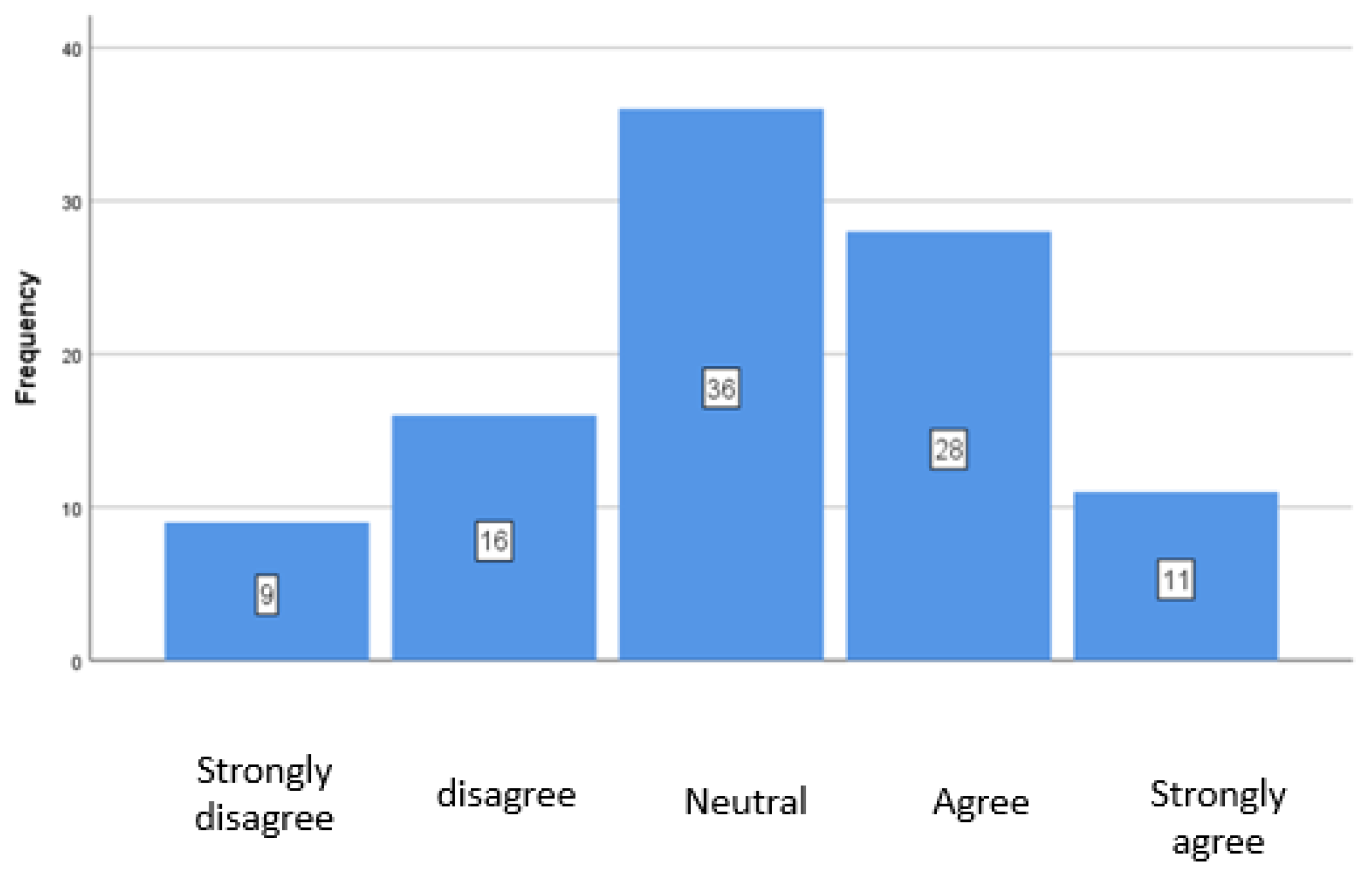

4.1. Implementation of Key ESG Factors

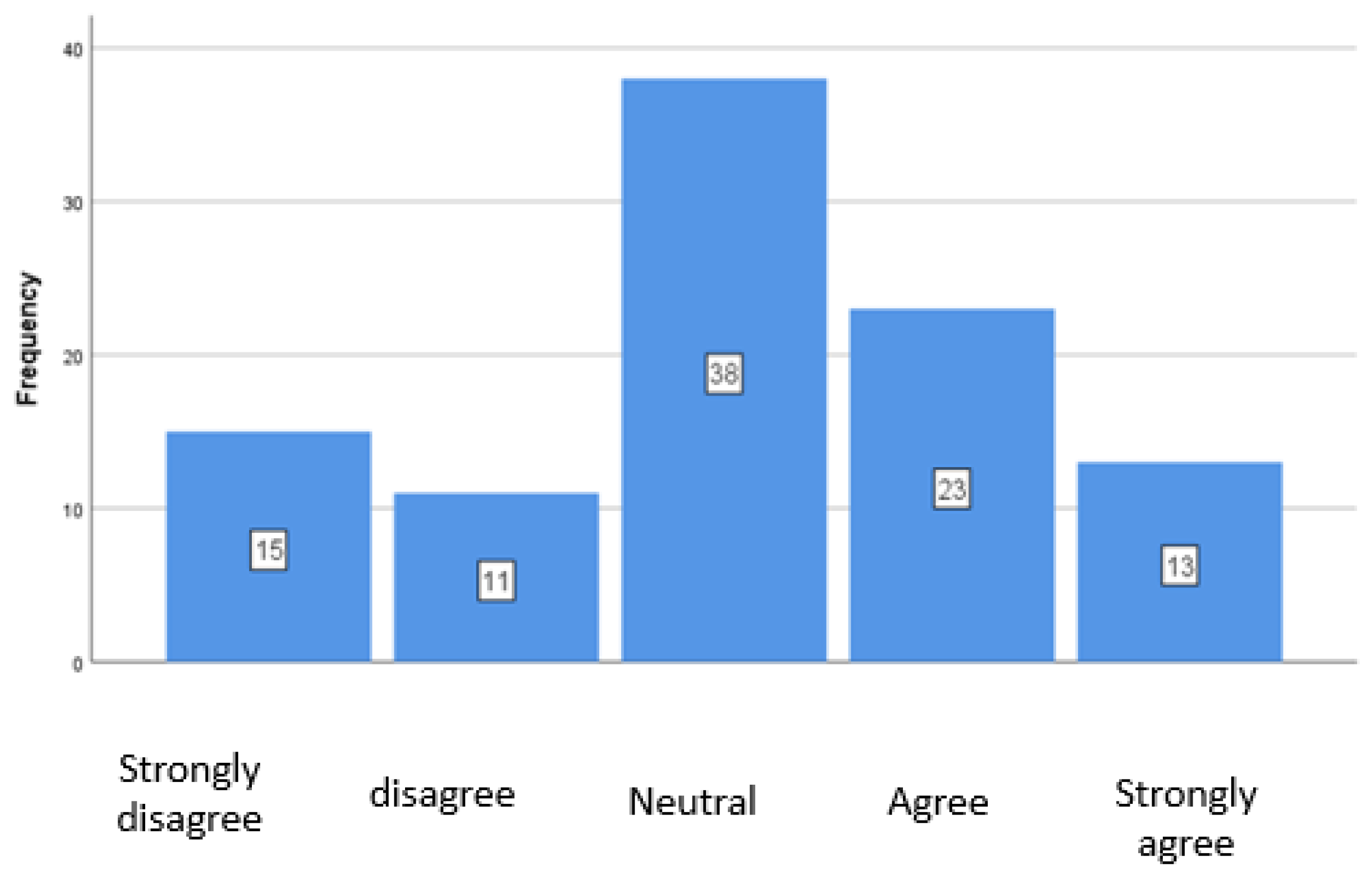

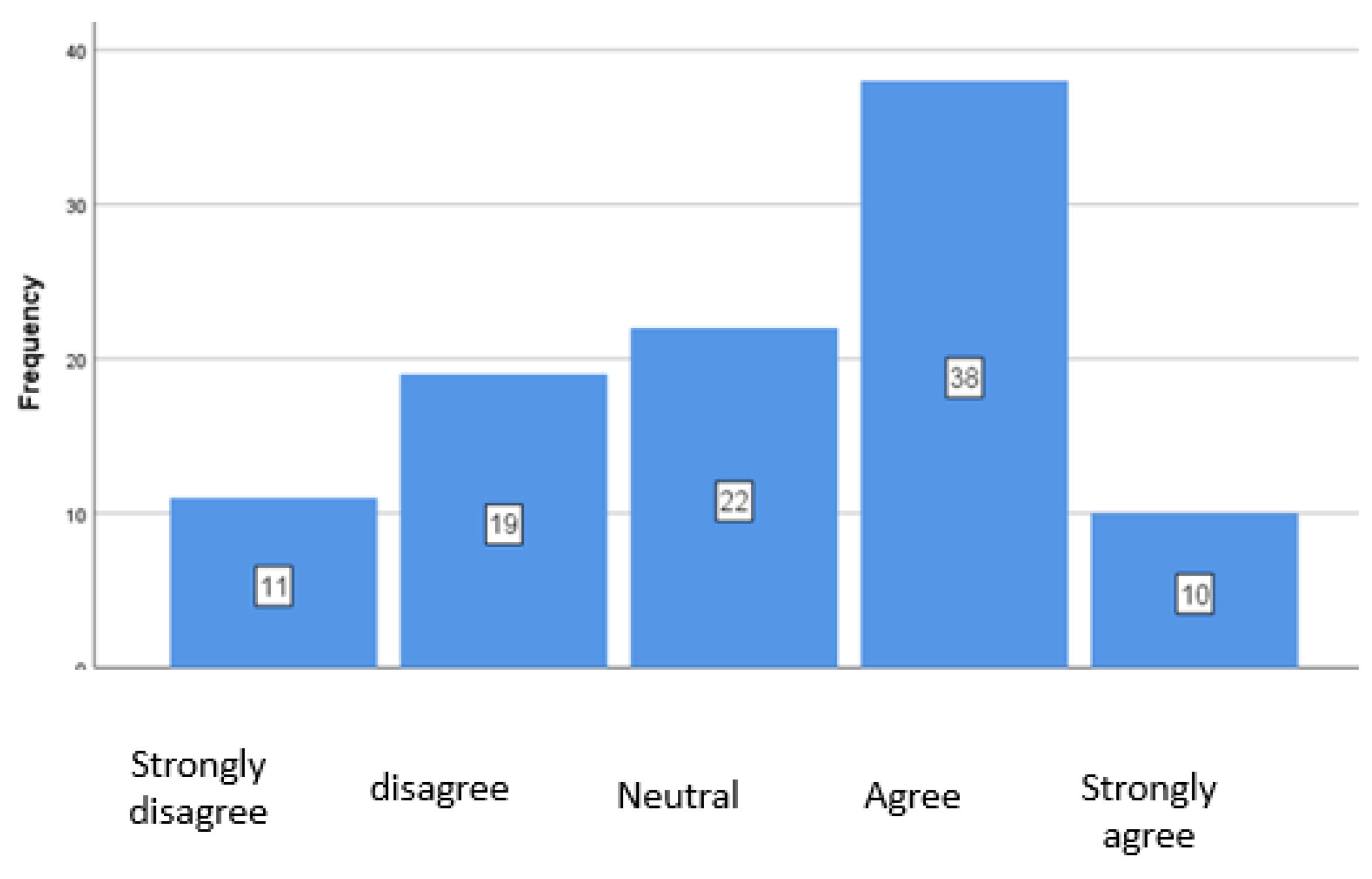

4.2. Influence on ESG Training on Options

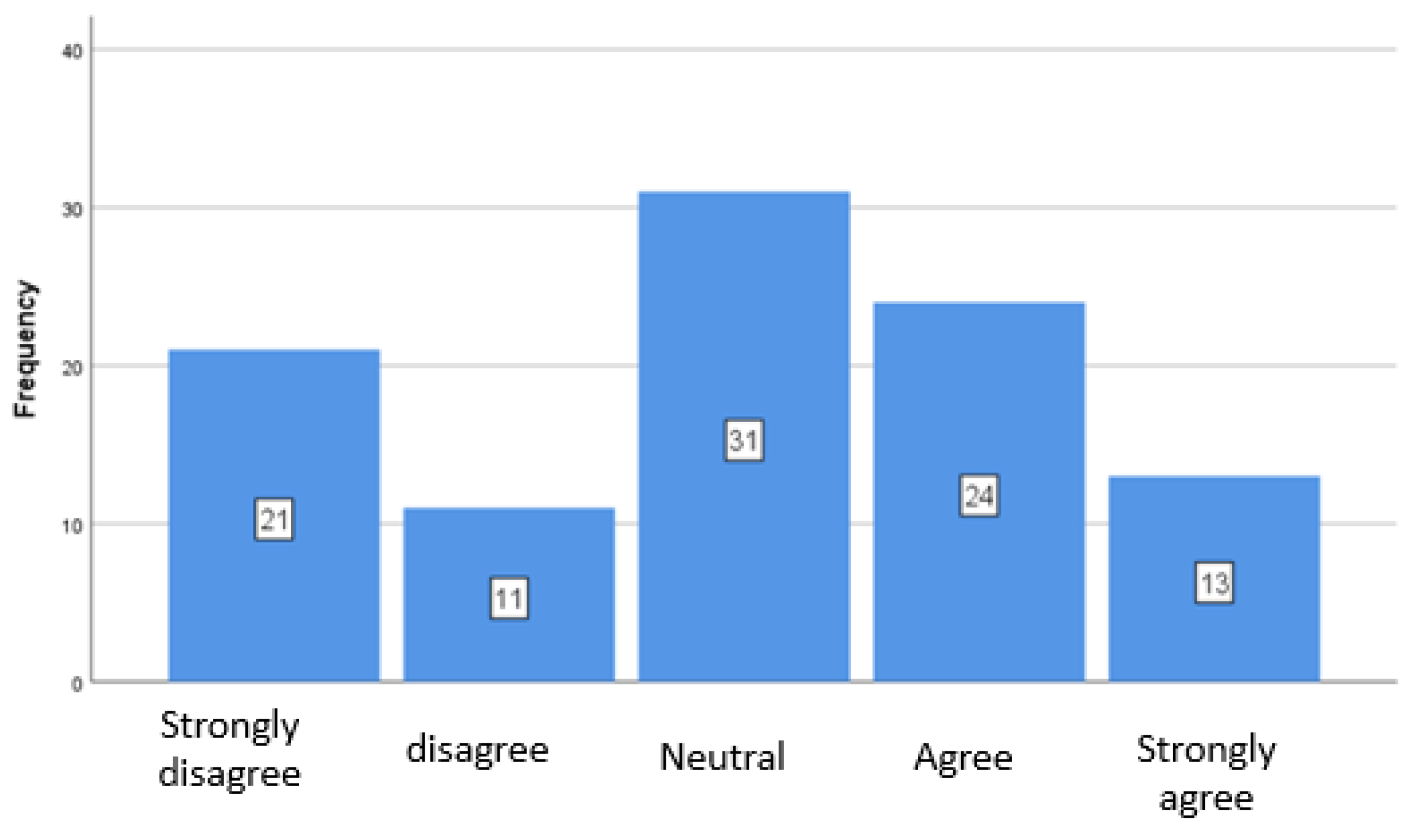

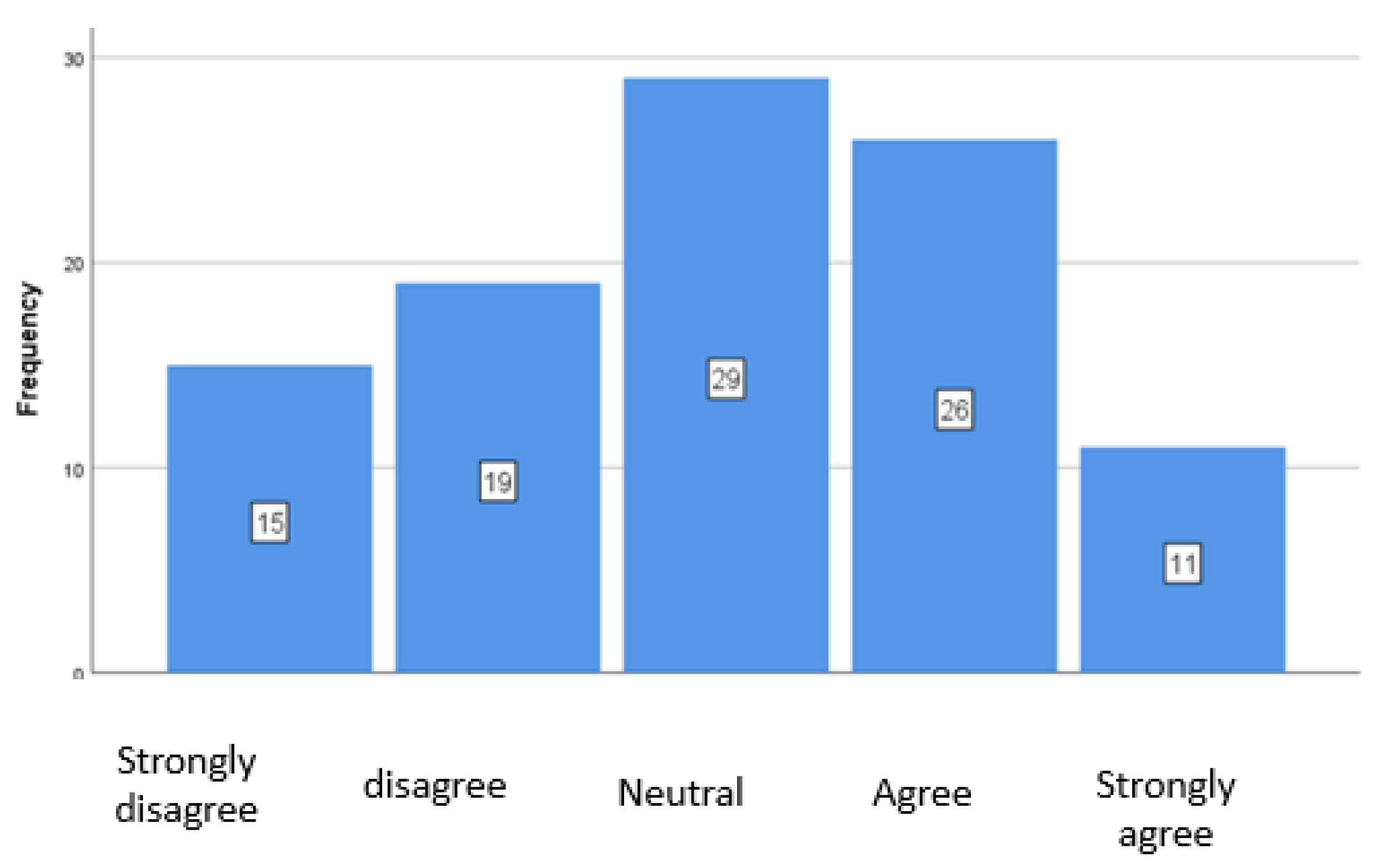

4.3. ESG Criteria in Specific Practices

4.4. Age Based Correlations

4.5. Educational Level – Based Correlations

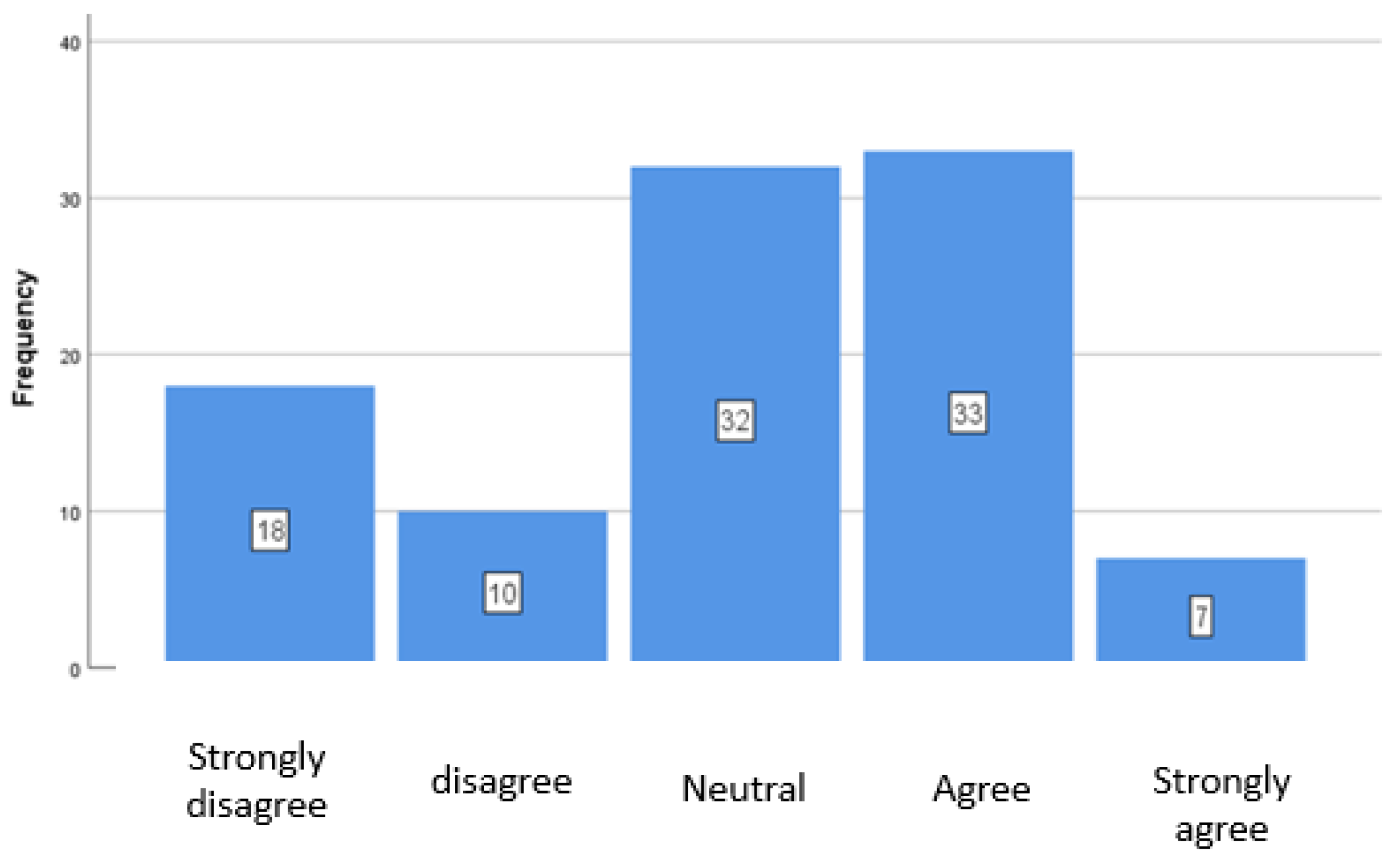

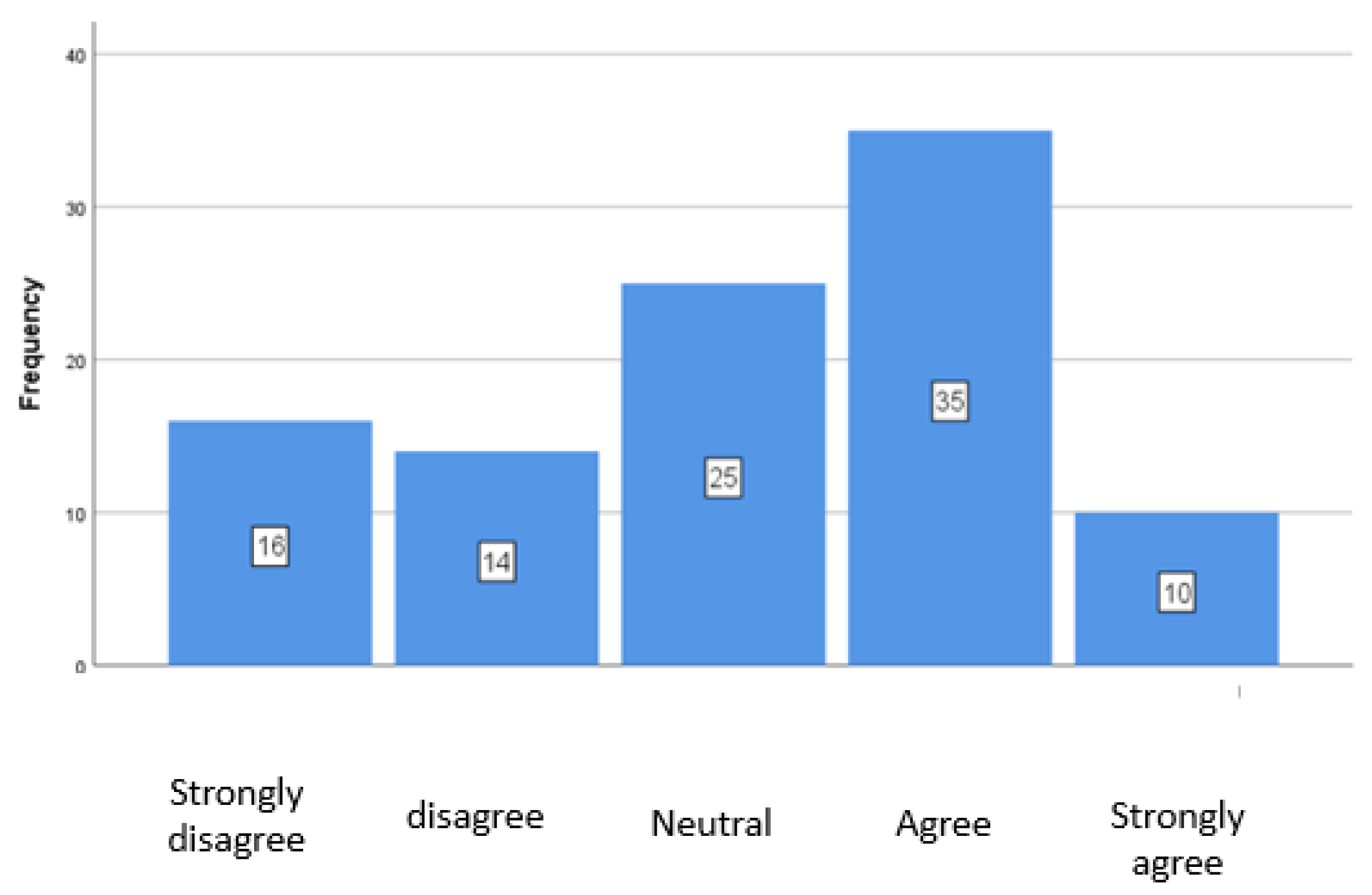

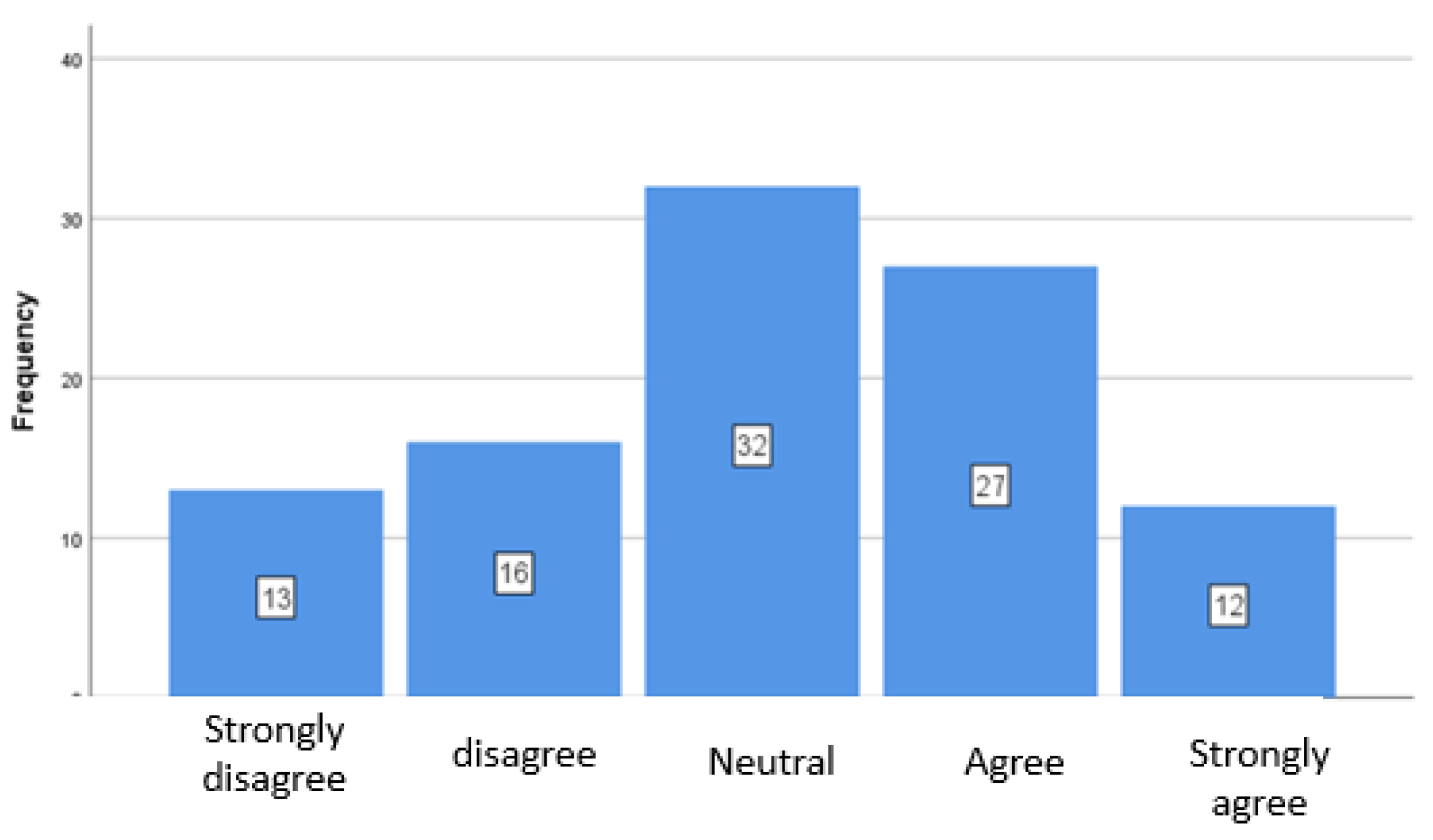

4.6. Training on ESG Assessment

5. Discussion & Conclusions

Author Contributions

Appendix A

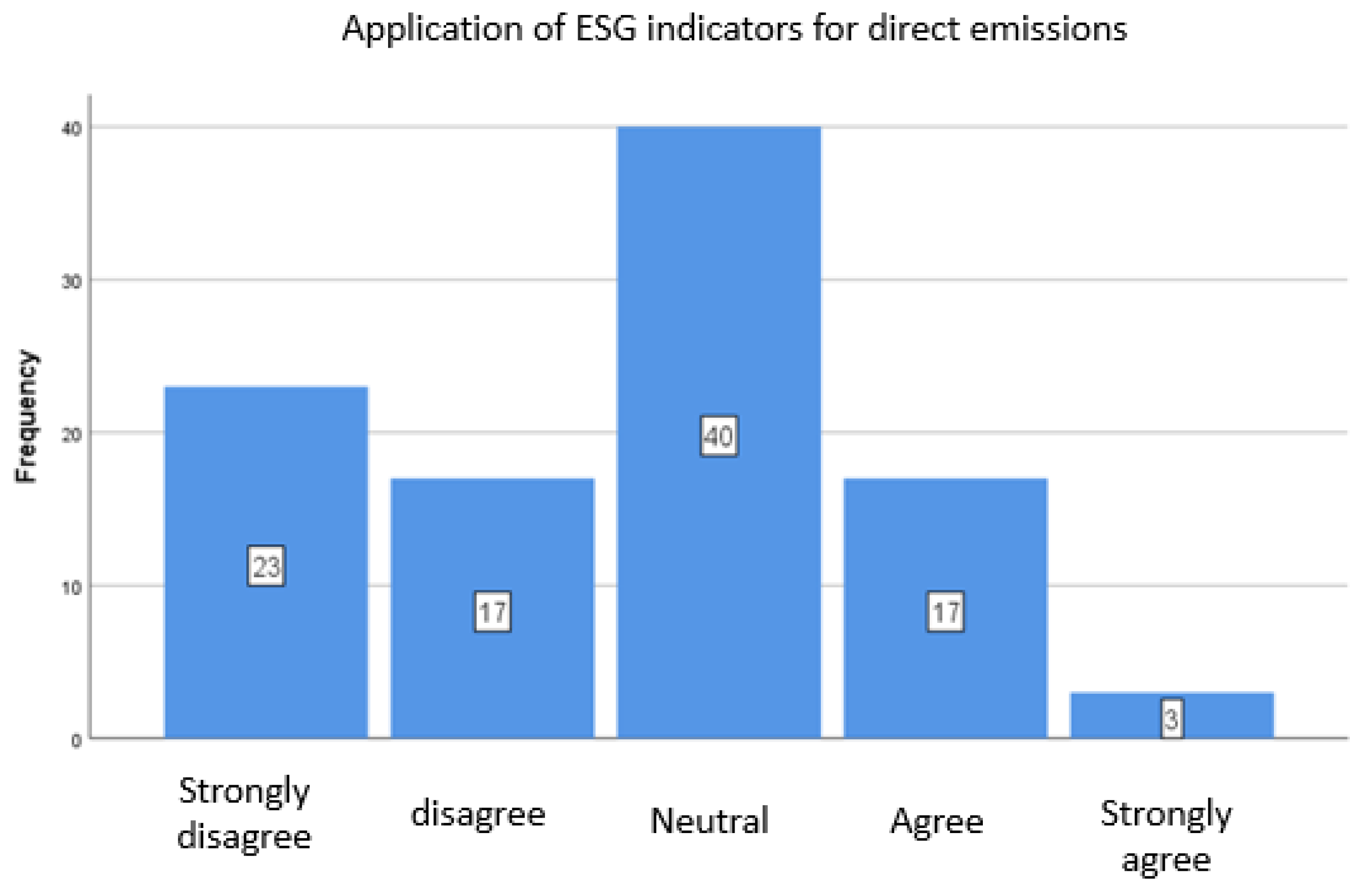

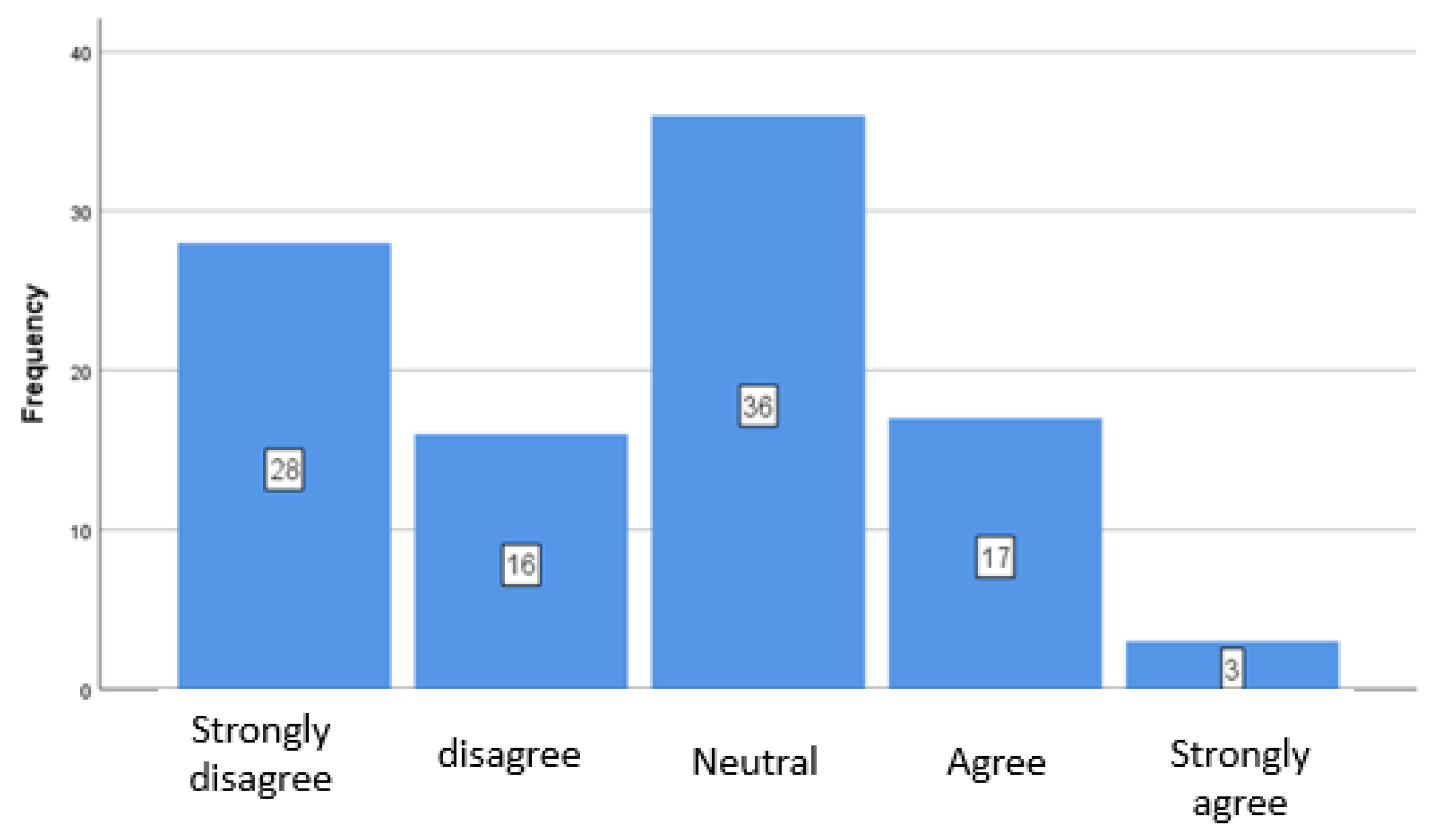

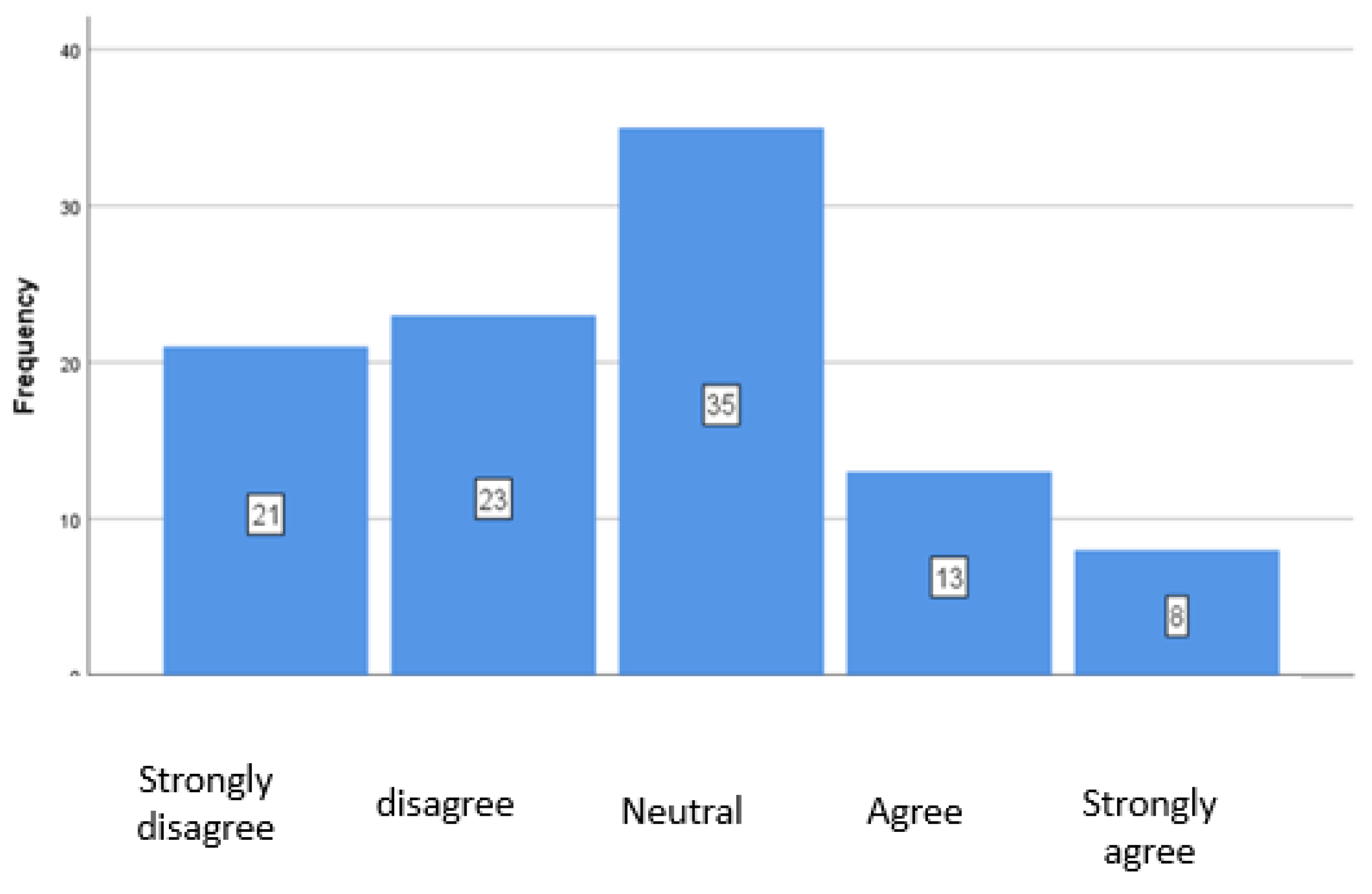

A.1.1. Application of Key ESG Indicators

| M | SD | |

| Application of key ESG indicators_Direct emissions | 2,60 | 1,110 |

| Application of key ESG indicators_Direct emissions | 2,51 | 1,159 |

| Application of ESG_Energy consumption and production key indicators | 2,64 | 1,185 |

| Implementation of ESG_Stakeholder participation key indicators | 2,61 | 1,188 |

| Application of ESG_Women workers key indicators | 3,08 | 1,212 |

| Implementation of ESG_Women employees in managerial positions | 2,97 | 1,314 |

| Implementation of ESG_Personnel mobility key indicators | 3,01 | 1,202 |

| Application of ESG_Employee training key indicators | 3,16 | 1,108 |

| Application of ESG_Human rights policy key indicators | 3,17 | 1,181 |

| Implementation of key ESG indicators_Collective labour agreements | 2,99 | 1,227 |

| Implementation of ESG key indicators_Supplier assessment | 3,09 | 1,240 |

| Implementation of ESG core indicators_Board composition | 3,09 | 1,198 |

| Implementation of ESG key indicators_Sustainable development monitoring | 2,89 | 1,214 |

| Implementation of ESG KPIs_Substantial issues | 2,78 | 1,219 |

| Implementation of ESG core indicators_Sustainability policy | 2,96 | 1,348 |

| Implementation of ESG core indicators_Business ethics policy | 3,00 | 1,385 |

| Implementation of ESG_Geographical security policy | 3,30 | 1,168 |

A.1.2. Correlations with Age

| Age | Μ | SD | p | ||

| How well do you know the ESG criteria? | Up to 30 years old | 3,27 | 0,467 | 0,156 | |

| 31-40 years old | 2,79 | 0,992 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3 | 0,943 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,62 | 0,921 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 1,254 | |||

| Application of key ESG indicators Direct emissions | Up to 30 years old | 2,91 | 1,044 | 0,081 | |

| 31-40 years old | 2,64 | 1,084 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,79 | 1,228 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,24 | 0,944 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 1,254 | |||

| Application of key ESG Indirect emissions indicators | Up to 30 years old | 2,91 | 1,044 | 0,173 | |

| 31-40 years old | 2,58 | 1,146 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,79 | 1,228 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2 | 1,095 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2 | 0,816 | |||

| Application of ESG Energy consumption and production key indicators | Up to 30 years old | 3,18 | 1,401 | 0,245 | |

| 31-40 years old | 2,61 | 0,998 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,79 | 1,228 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,43 | 1,326 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2 | 0,816 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Stakeholder participation key indicators | Up to 30 years old | 3,09 | 1,136 | 0,26 | |

| 31-40 years old | 2,76 | 1,2 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,61 | 1,066 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,33 | 1,39 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2 | 0,816 | |||

| Application of ESG_Women workers key indicators | Up to 30 years old | 3,55 | 1,44 | 0,039 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,39 | 1,059 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,07 | 1,086 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,62 | 1,284 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 1,254 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Women employees in managerial positions | Up to 30 years old | 3,27 | 1,191 | 0,139 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,24 | 1,119 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,07 | 1,359 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,48 | 1,504 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 1,254 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Personnel mobility key indicators | Up to 30 years old | 3,45 | 0,522 | 0,011 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,33 | 1,137 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,86 | 1,177 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,9 | 1,446 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 1,71 | 0,488 | |||

| Application of ESG Employee training key indicators | Up to 30 years old | 3,73 | 1,104 | 0,043 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,33 | 1,051 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,18 | 1,02 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,86 | 1,276 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| Application of ESG Human rights policy key indicators | Up to 30 years old | 3,45 | 0,82 | 0,08 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,12 | 1,111 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,57 | 1,168 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,76 | 1,375 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,57 | 0,976 | |||

| Implementation of key ESG indicators Collective labour agreements | Up to 30 years old | 3,09 | 0,701 | 0,854 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,12 | 1,364 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,96 | 1,232 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,9 | 1,338 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,57 | 0,976 | |||

| Implementation of ESG key indicators Supplier assessment | Up to 30 years old | 3,27 | 0,467 | 0,177 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,21 | 1,364 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,36 | 1,162 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,67 | 1,461 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,43 | 0,535 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Board composition | Up to 30 years old | 3,64 | 0,505 | 0,48 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,18 | 1,31 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,93 | 1,12 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,9 | 1,446 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 3 | 0,816 | |||

| Implementation of ESG key indicators Sustainable development monitoring | Up to 30 years old | 3,27 | 0,467 | 0,069 | |

| 31-40 years old | 2,94 | 1,368 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,21 | 1,101 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,38 | 1,359 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| Implementation of ESG KPIs_Substantial issues | Up to 30 years old | 3,55 | 0,934 | 0,208 | |

| 31-40 years old | 2,82 | 1,236 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,68 | 1,124 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,48 | 1,504 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,71 | 0,488 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Sustainability policy | Up to 30 years old | 3,73 | 0,905 | 0,162 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,06 | 1,391 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 2,89 | 1,343 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,48 | 1,504 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 3 | 0,816 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Business ethics policy | Up to 30 years old | 3,91 | 0,831 | 0,017 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,18 | 1,402 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3 | 1,388 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,24 | 1,446 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 3 | 0,816 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Geographical security policy | Up to 30 years old | 3,91 | 0,831 | 0,003 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,36 | 1,27 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,61 | 0,685 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,48 | 1,289 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 3,29 | 1,254 | |||

| ESG effectiveness in attracting new customers | Up to 30 years old | 4,27 | 0,786 | 0,001 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,12 | 0,927 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,14 | 0,97 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,62 | 1,284 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,57 | 0,976 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for competitive advantage | Up to 30 years old | 4,27 | 0,467 | 0,002 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,45 | 1,201 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,46 | 0,922 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,86 | 1,108 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,57 | 0,976 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for revenue growth | Up to 30 years old | 4,09 | 0,701 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,21 | 0,96 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,25 | 0,585 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,76 | 1,044 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for increasing business credibility | Up to 30 years old | 4,45 | 0,522 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,82 | 0,392 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,75 | 0,799 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,14 | 1,558 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to reduce risk | Up to 30 years old | 3,73 | 0,905 | 0,019 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,36 | 0,699 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,25 | 0,752 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,95 | 1,499 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for attracting new investors | Up to 30 years old | 4,27 | 0,467 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,85 | 0,712 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,96 | 0,693 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,05 | 1,284 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,57 | 0,976 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to increase productivity | Up to 30 years old | 4,09 | 0,701 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,36 | 0,895 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,25 | 0,752 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 2,86 | 1,108 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to increase opportunities for growth | Up to 30 years old | 4,27 | 0,786 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,82 | 0,882 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,36 | 1,129 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,1 | 1,338 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to improve adaptability to technological, customer and regulatory changes | Up to 30 years old | 4,45 | 0,522 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 4,12 | 0,485 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,75 | 0,799 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,05 | 1,284 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Climate change | Up to 30 years old | 4,64 | 0,505 | 0,002 | |

| 31-40 years old | 4,27 | 0,977 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,89 | 0,737 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,57 | 1,207 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 3,29 | 0,488 | |||

| ESG Human Resources Management implementation challenges | Up to 30 years old | 4,45 | 0,522 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,82 | 0,882 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,71 | 0,659 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,43 | 1,165 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 1,86 | 0,9 | |||

| ESG Corruption and bribery implementation challenges | Up to 30 years old | 4,09 | 0,701 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 3,52 | 1,253 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,21 | 0,917 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,57 | 1,287 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,57 | 0,535 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of common guidelines for ESG assessment | Up to 30 years old | 4,45 | 0,522 | 0,047 | |

| 31-40 years old | 4,03 | 0,883 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,43 | 1,034 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,52 | 1,289 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,57 | 0,535 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of a supervisory authority for ESG evaluations | Up to 30 years old | 4,27 | 0,467 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 4,09 | 0,98 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,71 | 0,937 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,67 | 1,278 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of transparency of ESG assessments | Up to 30 years old | 4,27 | 0,467 | 0,001 | |

| 31-40 years old | 4 | 1,031 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,71 | 0,81 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,71 | 1,309 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Difficulty in complying with regulations | Up to 30 years old | 4,27 | 0,467 | 0 | |

| 31-40 years old | 4,06 | 0,788 | |||

| 41-50 years old | 3,93 | 0,858 | |||

| 51-60 years old | 3,67 | 1,278 | |||

| Over 60 years old | 2,29 | 0,488 |

A.1.3. Correlations with Educational Level

| Educational level | Μ | SD | p | ||

| How well do you know the ESG criteria? | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,3 | 0,65 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 2,9 | 0,9 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Application of key ESG indicators Direct emissions | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,4 | 0,68 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 2,6 | 1,11 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Application of key ESG Indirect emissions indicators | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,2 | 1,08 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 2,5 | 1,09 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Application of ESG Energy consumption and production key indicators | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,4 | 1,07 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 2,6 | 1,14 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Stakeholder participation key indicators | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,6 | 1,26 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 2,5 | 1,1 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Application of ESG Women workers key indicators | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,6 | 1,01 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,1 | 1,21 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG Women employees in managerial positions | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,5 | 1,17 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3 | 1,29 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Personnel mobility key indicators | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,7 | 1,1 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3 | 1,18 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Application of ESG Employee training key indicators | Graduate of higher education institution | 3 | 1,03 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,1 | 1,09 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Application of ESG Human rights policy key indicators | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,7 | 1,06 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,2 | 1,16 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of key ESG indicators Collective labour agreements | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,6 | 0,69 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3 | 1,27 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG key indicators Supplier assessment | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,6 | 1,17 | 0,02 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,1 | 1,21 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Board composition | Graduate of higher education institution | 3 | 0,88 | 0,02 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3 | 1,23 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG key indicators Sustainable development monitoring | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,7 | 1,16 | 0,05 | |

| Master's degree holder | 2,9 | 1,18 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG KPIs_Substantial issues | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,7 | 1,05 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 2,7 | 1,21 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Sustainability policy | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,7 | 1,05 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 2,9 | 1,38 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Business ethics policy | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,8 | 1,3 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3 | 1,38 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Geographical security policy | Graduate of higher education institution | 3 | 1,11 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,3 | 1,15 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 5 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness in attracting new customers | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,6 | 1,26 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,2 | 1,04 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for competitive advantage | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,7 | 0,87 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,5 | 1,13 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for revenue growth | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,6 | 0,9 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,3 | 0,9 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for increasing business credibility | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,9 | 1,29 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,8 | 0,88 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to reduce risk | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,6 | 1,07 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,3 | 0,92 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for attracting new investors | Graduate of higher education institution | 3 | 1,03 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,8 | 0,9 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to increase productivity | Graduate of higher education institution | 2,8 | 0,96 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,3 | 0,96 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to increase opportunities for growth | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,1 | 1,18 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,6 | 1,12 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to improve adaptability to technological, customer and regulatory changes | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,1 | 1,18 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,9 | 0,9 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Climate change | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,7 | 0,67 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 4,1 | 1,04 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG Human Resources Management implementation challenges | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,2 | 1,17 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,7 | 0,97 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG Corruption and bribery implementation challenges | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,1 | 0,81 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,5 | 1,19 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of common guidelines for ESG assessment | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,5 | 0,91 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,7 | 1,12 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of a supervisory authority for ESG evaluations | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,3 | 0,75 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,9 | 1,12 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of transparency of ESG assessments | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,3 | 0,75 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,9 | 1,11 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Difficulty in complying with regulations | Graduate of higher education institution | 3,4 | 0,77 | 0 | |

| Master's degree holder | 3,9 | 1,04 | |||

| Doctorate holder | 4 | 0 |

A.1.4. Links to Training on ESG Criteria

| Have you received training on the proper assessment of ESG indicators? | Μ | SD | p | ||

| How well do you know the ESG criteria? | Yes | 3,61 | 0,838 | 0 | |

| No | 2,39 | 0,704 | |||

| Application of key ESG indicators Direct emissions | Yes | 3,58 | 0,732 | 0 | |

| No | 2,05 | 0,881 | |||

| Application of key ESG Indirect emissions indicators | Yes | 3,47 | 0,941 | 0 | |

| No | 1,97 | 0,89 | |||

| Application of ESG Energy consumption and production key indicators | Yes | 3,61 | 0,964 | 0 | |

| No | 2,09 | 0,921 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Stakeholder participation key indicators | Yes | 3,44 | 0,877 | 0 | |

| No | 2,14 | 1,082 | |||

| Application of ESG Women workers key indicators | Yes | 3,89 | 0,919 | 0 | |

| No | 2,63 | 1,12 | |||

| Implementation of ESG Women employees in managerial positions | Yes | 3,83 | 0,845 | 0 | |

| No | 2,48 | 1,285 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Personnel mobility key indicators | Yes | 3,64 | 0,867 | 0 | |

| No | 2,66 | 1,224 | |||

| Application of ESG Employee training key indicators | Yes | 3,92 | 0,906 | 0 | |

| No | 2,73 | 0,98 | |||

| Application of ESG Human rights policy key indicators | Yes | 3,94 | 0,893 | 0 | |

| No | 2,73 | 1,102 | |||

| Implementation of key ESG indicators Collective labour agreements | Yes | 3,61 | 1,103 | 0 | |

| No | 2,64 | 1,16 | |||

| Implementation of ESG key indicators Supplier assessment | Yes | 3,69 | 0,98 | 0 | |

| No | 2,75 | 1,247 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Board composition | Yes | 3,75 | 0,841 | 0 | |

| No | 2,72 | 1,215 | |||

| Implementation of ESG key indicators Sustainable development monitoring | Yes | 3,94 | 0,893 | 0 | |

| No | 2,3 | 0,937 | |||

| Implementation of ESG KPIs_Substantial issues | Yes | 3,67 | 0,986 | 0 | |

| No | 2,28 | 1,046 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Sustainability policy | Yes | 3,97 | 1,028 | 0 | |

| No | 2,39 | 1,163 | |||

| Implementation of ESG core indicators Business ethics policy | Yes | 4 | 1,069 | 0 | |

| No | 2,44 | 1,22 | |||

| Implementation of ESG_Geographical security policy | Yes | 3,97 | 1,108 | 0 | |

| No | 2,92 | 1,028 | |||

| ESG effectiveness in attracting new customers | Yes | 3,81 | 0,668 | 0 | |

| No | 2,72 | 1,105 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for competitive advantage | Yes | 4,03 | 0,845 | 0 | |

| No | 2,98 | 1,061 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for revenue growth | Yes | 3,61 | 0,728 | 0 | |

| No | 2,91 | 0,938 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for increasing business credibility | Yes | 4,08 | 0,732 | 0 | |

| No | 3,36 | 1,06 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to reduce risk | Yes | 3,75 | 0,806 | 0 | |

| No | 2,91 | 0,955 | |||

| ESG effectiveness for attracting new investors | Yes | 4,11 | 0,747 | 0 | |

| No | 3,42 | 1,005 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to increase productivity | Yes | 3,61 | 0,871 | 0 | |

| No | 2,98 | 0,951 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to increase opportunities for growth | Yes | 4,11 | 0,887 | 0 | |

| No | 3,13 | 1,106 | |||

| ESG effectiveness to improve adaptability to technological, customer and regulatory changes | Yes | 4,11 | 0,82 | 0 | |

| No | 3,47 | 1,007 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Climate change | Yes | 4,14 | 0,351 | 0 | |

| No | 3,91 | 1,178 | |||

| ESG Human Resources Management implementation challenges | Yes | 4,17 | 0,775 | 0 | |

| No | 3,34 | 1,027 | |||

| ESG Corruption and bribery implementation challenges | Yes | 4,08 | 0,906 | 0 | |

| No | 3,08 | 1,074 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of common guidelines for ESG assessment | Yes | 4,14 | 0,639 | 0 | |

| No | 3,45 | 1,181 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of a supervisory authority for ESG evaluations | Yes | 4,06 | 0,791 | 0 | |

| No | 3,64 | 1,173 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Lack of transparency of ESG assessments | Yes | 4,14 | 0,762 | 0 | |

| No | 3,56 | 1,139 | |||

| ESG implementation challenges Difficulty in complying with regulations | Yes | 4,17 | 0,697 | 0 | |

| No | 3,66 | 1,087 |

References

- Passas, I. “The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0,” Encyclopedia 2024, Vol. 4, Pages 1711-1720, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 1711–1720, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Ragazou, I. Passas, A. Garefalakis, and C. Zopounidis, “ESG in Construction Risk Management: A Strategic Roadmap for Controlling Risks and Maximizing Profits,” in https://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/978-1-6684-7786-1.ch003, IGI Global, 1AD, pp. 58–81. [CrossRef]

- Passas, I. “Accounting for integrity: ESG and financial disclosures: the challenge of internal fraud in management decision-making,” Hellenic Mediterranean University, Heraklon, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Hervieux, M. McKee, and C. Driscoll, “Room for improvement: Using GRI principles to explore potential for advancing PRME SIP reporting,” The International Journal of Management Education, vol. 15, no. 2, Part B, pp. 219–237, 2017. [CrossRef]

- GRI, “CONSOLIDATED SET OF GRI SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING STANDARDS 2020 2 Consolidated Set of GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards 2020,” 2020.

- B. Adiloglu and B. Vuran, “Identification of key performance indicators of auditor’s reports: Evidence from Borsa Istanbul (BIST),” Journal of Economics, Finance and Accounting, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 256–261, 2017, [Online]. Available: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/370239.

- Sundgren, “Auditor choices and reporting practices: evidence from Finnish small firms,” The European Accounting Review, 7:3, 441-65., 1998.

- W. Steve. Albrecht, K. R. Howe, and M. B. Romney, “Deterring fraud : the internal auditor’s perspective,” p. 169, 1984.

- G. Serafeim and Y. Kontopoulos, “ESG Reporting Guide 2022,” 2022.

- M. D. Kimbrough, X. Wang, S. Wei, and J. Zhang, “Does Voluntary ESG Reporting Resolve Disagreement among ESG Rating Agencies?,” European Accounting Review, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Darnall, H. Ji, K. Iwata, and T. H. Arimura, “Do ESG reporting guidelines and verifications enhance firms’ information disclosure?,” Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 1214–1230, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Jackson, G. Michelson, and R. Munir, “Developing accountants for the future: new technology, skills, and the role of stakeholders,” Accounting Education, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 150–177, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Dathe, R. Dathe, I. Dathe, and M. Helmold, “Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Ethical Management,” Management for Professionals, vol. Part F361, pp. 107–115, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Dathe, R. Dathe, I. Dathe, and M. Helmold, “Corporate social responsibility (CSR), sustainability and environmental social governance (ESG) : approaches to ethical management”.

- T. Dathe, R. Dathe, I. Dathe, and M. Helmold, “Corporate social responsibility (CSR), sustainability and environmental social governance (ESG) : approaches to ethical management”.

- F. Bhuiyan, K. Baird, and R. Munir, “The association between organisational culture, CSR practices and organisational performance in an emerging economy,” Meditari Accountancy Research, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 977–1011, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Buhr, “The Professional Accountancy Bodies and the Provision of Education and Training in Relation to Environmental Issues,” The International Journal of Accounting, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 367–369, 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. Jeffrey, S. Rosenberg, and B. McCabe, “Corporate social responsibility behaviors and corporate reputation,” Social Responsibility Journal, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 395–408, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Grover, A. K. Kar, and P. V. Ilavarasan, “Impact of corporate social responsibility on reputation—Insights from tweets on sustainable development goals by CEOs,” Int J Inf Manage, vol. 48, pp. 39–52, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Walsh, V. W. Mitchell, P. R. Jackson, and S. E. Beatty, “Examining the antecedents and consequences of corporate reputation: A customer perspective,” British Journal of Management, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 187–203, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Klitou, Privacy-Invading Technologies and Privacy by Design, vol. 25. in Information Technology and Law Series, vol. 25. The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Zopounidis, A. Garefalakis, C. Lemonakis, and I. Passas, “Environmental, social and corporate governance framework for corporate disclosure: a multicriteria dimension analysis approach,” Management Decision, vol. 58, no. 11, pp. 2473–2496, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Ragazou, I. Passas, A. Garefalakis, and · Constantin Zopounidis, “Business intelligence model empowering SMEs to make better decisions and enhance their competitive advantage,” Discover Analytics 2022 1:1, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Barrymore and R. C. Sampson, “ESG Performance and Labor Productivity: Exploring whether and when ESG affects firm performance,” 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.morningstar.com/articles/959379/10-sustainable-investing-stories-of-2019.

- E. Escrig-Olmedo, M. ángeles Fernández-Izquierdo, I. Ferrero-Ferrero, J. M. Rivera-Lirio, and M. J. Muñoz-Torres, “Rating the raters: Evaluating how ESG rating agencies integrate sustainability principles,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 3, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Ragazou, C. Lemonakis, I. Passas, C. Zopounidis, and A. Garefalakis, “ESG-driven ecopreneur selection in European financial institutions: entropy and TOPSIS analysis,” Management Decision, vol. 63, no. 4, pp. 1316–1345, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Ping, M. Yue, Z. Qi, and S. Hao, “ESG-Driven Corporate Value Creation under the Paradigm of Ecological Civilization: Evidence from the Shareholder, Industrial Chain and Consumer Channels,” Soc Sci China, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 129–157, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Ragazou, S. Nikolaos, A. Garefalakis, and C. Papademetriou, “Improving the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurs by Integrating Environmental, Social, and Governance Principles Into the Management of Human Resources,” in ESG and Total Quality Management in Human Resources, 2024, ch. 12, pp. 243–260. [CrossRef]

- L. H. Pedersen, S. Fitzgibbons, and L. Pomorski, “Responsible investing: The ESG-efficient frontier,” J financ econ, vol. 142, no. 2, pp. 572–597, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bofinger, K. J. Heyden, and B. Rock, “Corporate social responsibility and market efficiency: Evidence from ESG and misvaluation measures,” J Bank Financ, vol. 134, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Passas, K. Ragazou, E. Zafeiriou, A. Garefalakis, and C. Zopounidis, “ESG Controversies: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis for the Sociopolitical Determinants in EU Firms,” Sustainability 2022, Vol. 14, Page 12879, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 12879, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Ahmad, M. Yaqub, and S. H. Lee, “Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: a scientometric review of global trends,” Feb. 01, 2024, Springer Science and Business Media B.V. [CrossRef]

- E. van Duuren, A. Plantinga, and B. Scholtens, “ESG Integration and the Investment Management Process: Fundamental Investing Reinvented,” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 138, no. 3, pp. 525–533, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. B. Barbier, “The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development,” Environ Conserv, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 101–110, 1987. [CrossRef]

- K. Ragazou, I. Passas, A. Garefalakis, and C. Zopounidis, “ESG in Construction Risk Management,” in IGI Global, 2023, ch. 3, pp. 58–81. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Li, K. Wang, T. Sueyoshi, and D. D. Wang, “Esg: Research progress and future prospects,” Nov. 01, 2021, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- N. Lior, M. Radovanović, and S. Filipović, “Comparing sustainable development measurement based on different priorities: sustainable development goals, economics, and human well-being—Southeast Europe case,” Sustain Sci, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 973–1000, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Tavares, G. Azevedo, R. P. Marques, and M. A. Bastos, “Challenges of education in the accounting profession in the Era 5.0: A systematic review,” 2023, Cogent OA. [CrossRef]

- Petropoulou, E. Angelaki, I. Rompogiannakis, I. Passas, A. Garefalakis, and G. Thanasas, “Digital Transformation in SMEs: Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Era: A Comparative Bibliometric Analysis,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 23, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. B. Barbier, “The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development,” Environ Conserv, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 101–110, 1987. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Chopra et al., “Navigating the Challenges of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Reporting: The Path to Broader Sustainable Development,” Jan. 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- T. Nakajima et al., “ESG Investment in the Global Economy.” [Online]. Available: http://www.springer.com/series/15423.

- Armstrong, “Ethics and esg,” Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 6–17, 2020. [CrossRef]

- de Souza Barbosa, M. C. B. C. da Silva, L. B. da Silva, S. N. Morioka, and V. F. de Souza, “Integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria: their impacts on corporate sustainability performance,” Dec. 01, 2023, Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- M. Jain, G. D. Sharma, and M. Srivastava, “Can sustainable investment yield better financial returns: A comparative study of ESG indices and MSCI indices,” Mar. 01, 2019, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- E. Chatzopoulou, “449U Analysis of Esg Criteria and Sectoral Study of Sustainable Development in Greece (The Mast Project) Analysis of Esg Criteria and Sectoral Study of Sustainable Development in Greece (The Mast Project),” 449U London Journal of Research in Management & Business, vol. 24, 2024.

- Δ. Εργασία, “Σχολή Κοινωνικών Επιστημών Μεταπτυχιακό Πρόγραμμα Σπουδών στην Τραπεζική.”.

- W. Henisz, T. Koller, and R. Nuttall, “Five ways that ESG creates value Getting your environmental, social, and governance (ESG) proposition right links to higher value creation. Here’s why,” 2019.

- J. Öhman, “Exploring Managerial Attitudes to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG): A case study.”.

- M. Fiandini, A. B. D. Nandiyanto, D. F. Al Husaeni, D. N. Al Husaeni, and M. Mushiban, “How to Calculate Statistics for Significant Difference Test Using SPSS: Understanding Students Comprehension on the Concept of Steam Engines as Power Plant,” Indonesian Journal of Science and Technology, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 45–108, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Y. Soumena, “The Effect Of Entrepreneurship Competence And Islamic Business Ethics On The Performance Of Micro And Small Enterprises (SMEs) Makassar,” Jurnal Ilmiah Ekonomi Islam, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 156, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Eti, “The Effects of Perceptions of Economic Sustainability and Barriers on Organic Farming Implementation,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 17, no. 2, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Le and X. Zhang, “How Green Entrepreneurial Orientation Influences Corporate Performance: The Missing Link of Green Knowledge Sharing,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 24, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Haque and M. M. Rahman, “Sustainability Reporting: Empirical Evidence from Listed Firms of Fuel and Power Sector of Bangladesh,” Dhaka University Journal of Business Studies, pp. 175–212, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Dumay, J. Guthrie, and F. Farneti, “GRI sustainability reporting guidelines for public and third sector organizations: A critical review,” Public Management Review, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 531–548, 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Eccles, I. Ioannou, and G. Serafeim, “The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance.”.

- A. Adams and C. Larrinaga-González, “Engaging with organisations in pursuit of improved sustainability accounting and performance,” Jun. 12, 2007. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).