1. Introduction

Learning Chinese characters poses significant challenges for beginners, non-native learners, particularly those from alphabetic language backgrounds at the beginning level (Hu, 2010; Wu, 2014; Yang, 2018; Zhang & Li, 2010). Chinese characters use a logographic system where each character conveys meaning through visual elements rather than phonetics (Shen, 2013). Strong visual-spatial skills are vital for learning Chinese characters, as the ability to distinguish subtle visual differences is essential due to the large number of similar-looking radicals and characters in Chinese orthography (e.g., Chen, et al, 1996; McBride-Chang, et al., 2005, etc.). In this study, we aim to explore whether visual factors such as color coding, stroke structure and presentation style can assist non-native learners in acquiring visually similar Chinese characters by means of reducing cognitive load and thus enhancing memory retention.

The orthographic structure of Chinese characters can be analyzed hierarchically to its components: radicals and strokes. Radicals often serve as semantic or phonetic indicators. For example, the semantic radical 氵 (three dots/strokes to indicate water) is found in characters related to water, like 河 (river) and 海 (sea). Likewise, the phonetic radical 青 (pronounced as qing) in 清(qing1), 情(qing2), 请(qing3), etc., produces similar pronunciation. They are essential for organizing and understanding Chinese writing, as they help group characters with similar meanings or pronunciations. Strokes are the basic components of Chinese radicals and characters. A stroke in Chinese writing is created with a single, continuous motion, often involving changes in direction (Anderson et al., 2013). Shu, et al. (2003) analyzed 2,570 characters taught in Chinese elementary schools and identified eight types of strokes that vary in length and spatial orientations. Strokes can take various forms—vertical, horizontal, or diagonal; straight or slightly curved; and some may include a “hook” (Taylor & Taylor, 1995). For instance, the simple character 木 (wood) contains four types of strokes: vertical (一), horizontal (丨), left-slanting (丿), and right-slanting (㇏). Additionally, shorter stroke segments, such as dots, can vary in direction, as seen in the character 兴 (prosperous), as compared to the character 河 (river).

Characters are categorized into two types based on their structures: integral and compound characters. Integral characters contain only one radical, such as the character 人, which includes a single radical that conveys the meaning “person” (Zhang 1992: 31–32). Integral characters can be formed with as simple as one stroke (一) or as complex as multiple strokes (束). One dimension of visual complexity of Chinese characters is the relative positions of different strokes. For example, the same two strokes can create different characters by varying the stroke positions. For instance, both 人 (person) and 入 (enter) are composed of two strokes: 丿 and ㇏, but their differing arrangements result in distinct characters.

Similarly, in compound characters, the position of sub-lexical orthographic units (radicals) can change to form entirely different characters (Zhang 1992: 60–61). For example, 杏 (apricot) and 呆 (dumbness) both include the components 木 (wood) and 口 (mouth) arranged in a top-down pattern. When the positions of these components are reversed, a completely different character is formed. In another example, 晾 (air/sundry) and 景 (scenery) both contain the radical 日 (sun) and京 (capital). However, the structural arrangement differs: 晾 follows a left-right pattern, while 景 adopts a top-down structure.

The phenomenon where Chinese characters share the same strokes but differ in stroke structure is intriguing, especially when considering how L2 beginners of alphabetic language backgrounds learn and identify these visual complexities to map to the meanings eventually. Previous studies on visual complexity typically focus on stroke counts, assuming that more strokes equate to greater visual complexity (e.g., Shu et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2018) when considering L2 learning of Chinese characters. Yet, learning characters not only involves learning the strokes composed of a character, but also identifying characters that look similar but differ in stroke structures. The latter is probably harder to learn, in particular, at the early stage of learning, given the subtlety. To our knowledge, no study has yet explored whether characters of the same stroke counts but presenting different stroke structures pose additional difficulties for Chinese L2 learners. Thus, the aim of the study is to examine how visual similarity (i.e., stroke structure) influences the early stage of L2 Chinese character learning. We focused on integral characters, because as compared to compound characters, they contain fewer strokes and simpler stroke patterns, normally defined as “spatially contiguous patterns of strokes” (Anderson et al., 2013, p. 45).

1.1. Visually Similar Words in Chinese Orthography

A basic examination of the Chinese writing system quickly highlights its stronger emphasis on visual-spatial processing compared to alphabetic orthographies that bear certain phonological relationships with words. That is, the alphabet usually indicates how words sound to a large or small extent, depending on the orthographic depth of the writing system. This is usually referred to Grapheme-Phoneme-Correspondence (GPC) rule. Thus, unlike alphabetic systems, which rely on a segmental and “atomistic” structure (Ho & Bryant, 1999), Chinese lacks this rule. In other words, unlike alphabetic languages, Chinese characters bear little relation to the way a character sounds. As a result, learning to read Chinese may be primarily driven by identifying visual/stroke structures, rather than relying heavily on phonological skills as Jin (2006) found that learners demonstrated the best retention of new characters when the character's configuration/radical was highlighted, rather than highlighting the stroke order or pinyin alone. The nonlinear spatial arrangements of strokes within Chinese characters, patterned as square-shaped structures, —and their high spatial frequency (visual characteristics of Chinese characters that involve fine details and rapid changes within a small spatial area. For example, characters with many small strokes or detailed radicals would be considered to have high spatial frequency) may also place greater demands on spatial memory compared to the linear layout of alphabetic scripts (e.g., Wang, Koda & Perfetti, 2003). The development of sensitivity to the internal structure of Chinese characters is a gradual process. Gao and Meng (2000) found that beginning learners were significantly less accurate than advanced learners at distinguishing between visually similar characters (e.g., 会 vs.公, 休vs.体) in a reading context. Beginners often struggle to notice subtle differences between similarly shaped characters and are not yet familiar with perceiving the details of stroke-based writing.

The literature contains various measures of visual complexity for Chinese characters, which aim to accurately reflect their complexity. For example, these measures include stroke frequency (Majaj et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2007) and the “ink” measure (Pelli et al., 2006). Among these, Visual complexity is typically measured by the number of strokes (Liversedge et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2018). However, Chinese characters of the same number of strokes can represent entirely different words, such as 犬 (dog) and 太 (too). Although both characters consist of three strokes, their stroke patterns and spatial arrangements vary significantly. This complexity extends beyond stroke count to include differences in radicals, spatial arrangements, and even subtle variations in individual strokes. In a very similar way, characters like 大 (big) and 犬 (dog), where the latter is formed by adding a single stroke to the former, are normally considered as visually similar characters. These conditions highlight the intricate nature of Chinese orthography and thus raise an intriguing question: when comparing characters like 大 (big) vs. 犬 (dog), and 犬 (dog) vs. 太 (too), where the former pair differs by the addition of a stroke to the first character and the latter pair consists of two characters with the identical number of strokes but different patterns, which pair can be considered more visually complex or more difficult to learn?

Research on Chinese visual word recognition, particularly through the stroke number effect, remains limited. Jiang et al. (2020) conducted a study comparing native Chinese speakers (NS) and Chinese as a second language (CSL) learners using a lexical decision task involving disyllabic compound words (each containing two characters) and an equal number of nonwords. The results revealed that while both groups were influenced by word frequency and familiarity, only the CSL group demonstrated a stroke number effect. In a subsequent study, Jiang and Feng (2021) used single Chinese characters as stimuli and found that CSL learners again exhibited a stroke number effect in a lexical decision task. They argued that adult L2 Chinese learners process Chinese characters analytically, much like beginning readers, focusing on individual strokes or components rather than recognizing the overall character structure (Yeh et al., 2003).

If the number of strokes plays a key role in L2 character learning, we hypothesize that visually similar word pairs with an additional stroke will be more challenging to learn. However, there is currently no clear evidence indicating whether integral characters with the same number of strokes are equally difficult or harder to process compared to those with an additional stroke. Could English beginning readers of Chinese exhibit less-developed visual processing skills, due to lack of exposure, when distinguishing between integral characters with the same number of strokes and those with an additional stroke, such that this stroke number effect would not be as obvious as native readers?

1.2. Color Coding in Word Learning

Color coding has been shown to facilitate word learning by enhancing morphological awareness and supporting the decoding of linguistic structures (e.g., Tortorelli et al., 2021; Songsangkaew et al., 2023.). For example, Tortorelli et al. (2021) reviewed instructional approaches to teaching code-related skills in English reading and highlighted the effectiveness of strategies such as separating words into phonemes, syllables, and morphemes, as well as teaching affixes explicitly. These methods of integrating colors into linguistic structures are instrumental in helping learners navigate the complexities of an alphabetic language. Supporting this, Songsangkaew et al. (2023) demonstrated that color-coding derivational and inflectional morphemes significantly improved morphological awareness, lexical inferencing ability, and reading comprehension among non-English major undergraduates. By visually distinguishing morphemes, color coding may provide learners with a clearer understanding of word structures, aiding the acquisition of both vocabulary and reading skills.

If visual support, like color coding, can benefit learning alphabetical languages as evidenced in various studies, this strategy might be also helpful in learning Chinese characters which rely more on visual processing given their complex stroke structures. Though relevant research is limited and far from being conclusive. To start, some researchers consider lower-level structures of characters as a unit to learn, i.e., radicals, which facilitate L2 character learning by providing integrated structural features, unlike the complexity and variability of individual strokes (e.g., Huang & Chen, 1988). Radicals help to organize stroke-level information (Taft & Chung, 1999) and draw learners’ attention to the internal structure of characters to some extent (Cao et al., 2013a). For example, Taft and Chung (1999) conducted a study in which participants learned 24 Chinese characters composed of two radicals paired with meaning (e.g., 咀-CHEW) under four different radical presentation conditions to see whether understanding the internal structure of Chinese characters aids novice learners in memorization. Participants were exposed to the character-meaning pairs three times and then presented with each character alone to recall its associated meaning. In a between-subject design, four groups received different types of radical instructions: Radicals Before (radicals pre-learned before exposure), Radicals Early (radicals informed during the initial exposure), Radicals Late (radicals identified during the third exposure), and No Radical (no instruction on radicals). The Radicals Early group performed best, suggesting that introducing radicals at the first exposure enhances learning.

If radical learning serves as the foundation of character learning as indicated by previous studies (Taft & Chung, 1999), strategies like color-coding to mark the boundaries of radicals within a character might be facilitatory in L2 character learning as well. However, existing empirical evidence does not seem to support this rationale. Among the limited studies investigating whether marking radicals with different colors—a common teaching technique—supports L2 orthographic and semantic learning, Hou and Jiang (2022) explored its impact on Chinese L2 learners of alphabetic language backgrounds. In a Latin square design, participants were required to learn characters presented across four distinct conditions: (a) radical markings with stroke animations, (b) no radical markings with stroke animations, (c) radical markings without stroke animations, and (d) neither radical markings nor stroke animations. They were shown 40 high-frequency fillers and 120 low-frequency target words, with each character displayed for 1,000 milliseconds. In the study, compound characters were divided into two radicals, either left and right or top and bottom, with the radicals marked in red and blue, respectively. For instance, in the character “苛,” the radical “艹” on top was marked in red, while the radical “可” on the bottom was marked in blue. After learning, participants completed character recognition and meaning-matching tests. The results showed that marking radicals increased participants’ reaction times and reduced their accuracy in character recognition tests. Similarly, stroke-order animations also negatively affected recognition accuracy. These findings suggest that providing radical and stroke information may interfere, rather than facilitate character learning, as excessive visual information can increase cognitive load for L2 learners. Although strokes and radicals are key sub-character units in native Chinese speakers' character processing (e.g., Peng &Wang, 1997; Li et al., 2005), their utility for L2 learners in developing Chinese orthographic representations and orthography-semantics connections remains controversial. It is empirical to test whether color-coding a single critical stroke in a character would change the learning outcome.

In the present study, instead of applying color to the entire character (radical), we focused on highlighting one or two specific strokes that distinguish paired words from one another. Su and Samuels (2010) suggest that “beginning Chinese readers process characters in an analytic way”. To emphasize the critical differences between paired words, we applied color coding to the distinguishing strokes. For example, in word pairs with the same number of strokes, such as 犬 and 太, the differentiating dot was highlighted in color to provide critical input. Similarly, for words with a different number of strokes, such as 日 and 旦, the distinguishing stroke 一 was color-coded.

1.3. Presentation Style of characters

Given the pivotal role of generalization in cognition, there has been substantial research exploring the factors that facilitate it. Among them, the timing of instance presentation is particularly important. Research findings reveal a paradox: both simultaneous presentation (presenting instances at the same time), which allows for direct comparison (e.g., Gentner, Loewenstein, Thompson, & Forbus, 2009; Oakes & Ribar, 2005)., and spaced presentation (presenting instances apart in time), which separates instances over time (e.g., Cepeda, Pashler, Vul, Wixted, & Rohrer, 2006), have been shown to enhance generalization.

According to structure mapping theory (Gentner, 1983; Namy & Gentner, 2002; Thompson & Opfer, 2010), presenting exemplars at the same time draws attention to shared features, encouraging mental comparison, and the identification of commonalities within a category. Researchers suggest that simultaneous presentations help learners focus on the similarities between exemplars while reducing the short-term memory load required to compare them. As all exemplars are visible during this process, learners do not need to rely on memory to recall previously seen examples, which reduces cognitive demands. In addition, identifying these shared features helps learners generalize to new exemplars within the category. In short, simultaneous presentations support generalization by directing visual attention to key similarities and easing memory requirements.

On the other hand, other researchers suggest that both simultaneous and spaced learning facilitate generalization. For example, Vlach et al. (2012) investigated the effects of simultaneous, massed, and spaced presentations on 2-year-old children’s performance in a novel noun generalization task. In this task, four new objects were introduced and labeled (e.g., “fep”) using simultaneous, massed, or spaced presentation methods in the learning phase. In the simultaneous condition, all exemplars were presented at once, allowing children to visually compare them. In the massed condition, exemplars were presented one at a time in immediate succession, with less than 1 s between presentations. In a spaced condition, 30 s elapsed between each presentation. The massed and spaced presentation belonged to sequential presentation. In the test phase, four objects were shown, and children were asked to identify the target object (e.g., “Can you hand me the fep?”). For children in the immediate testing condition, the test was conducted right after the learning phase. For those in the delayed testing condition, the test took place 15 minutes later. Results showed that children in the simultaneous condition outperformed those in the other two conditions on immediate tests, while children in the spaced condition performed best after a delay (15 minutes). Overall, research suggests that visually comparing multiple exemplars presented simultaneously promotes better skills of abstraction, retention, and generalization compared to sequential (massed) presentations.

In their ongoing research program, Vlach et al. (2022) investigated how preschool-aged children learn science category exemplars under three schedules: simultaneous, massed, and spaced presentations. While no differences were observed between conditions during the immediate test, their first experiment showed that children in the spaced condition demonstrated the strongest generalization performance at a delayed post-test. However, further experiments revealed that spaced learning led to reduced visual attention and increased forgetting during the learning process.

Previous studies have investigated the effects of simultaneous, massed, and spaced learning on students’ performance in science education. The presentation style of literacy development has not been extensively studied. While spaced presentation has been found to reduce visual attention and increase forgetting (Vlach et al., 2022), in the present study, we aim to adopt simultaneous and massed presentation methods to explore their impact on word learning. This study aims to address this gap by investigating how visual stimuli, specifically presenting characters in sequence or in pairs, impact learners' ability to acquire and retain Chinese characters.

In summary, this study aims to address the following questions:

Do L2 beginning Chinese learners learn visually similar characters of identical number of strokes more effectively than those of different stroke numbers (word pairs differ by one stroke), or vice versa?

Does the use of color coding to highlight the critical strokes that differentiate visually similar characters facilitate L2 character learning?

Does simultaneous presentation (2 characters presented together) enhance L2 character learning more effectively than massed presentation (1 character presented individually)?

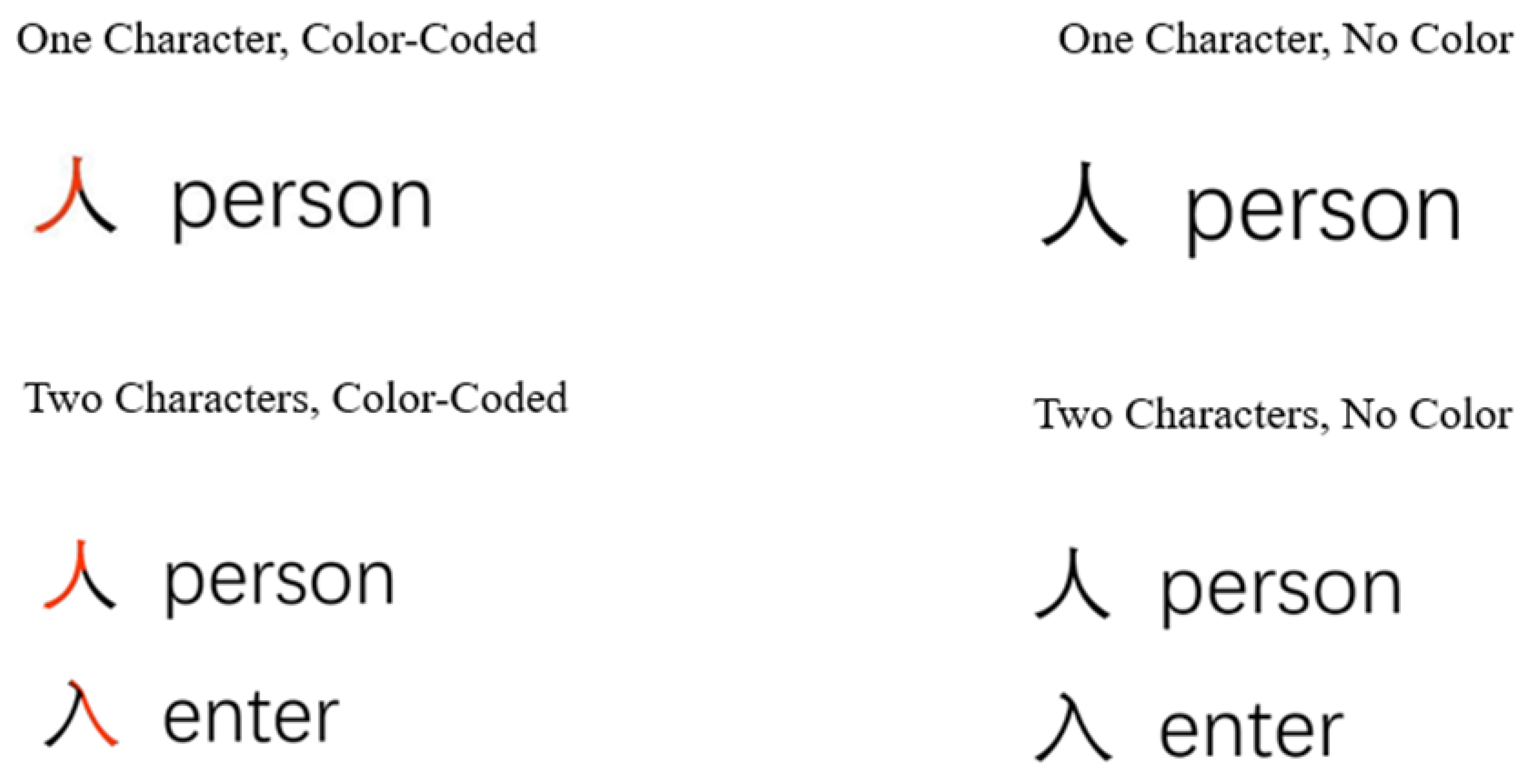

To address the above questions, we designed a study of four different experimental conditions, namely, “One Character, Color-Coded”, “One Character, No Color”, “Two Characters, Color-Coded”, “Two Characters, No Color”, such that we can test how L2 learners learn Chinese characters in different contexts. L2 learners were expected to learn both the stroke structures and the meanings of characters. To investigate this, we employed a 2 x 2 x 2 experimental design of three dependent variables: (1) Critical strokes cued with vs. without color, (2) Presentation with 1 vs. 2 characters, and (3) Characters with identical vs. different stroke numbers. Color-coding and Presentation Style were between-subjects factors, while Stroke Number was a within-subjects factor, as all learners were exposed to characters with both the same and different stroke numbers. Participants received the training first, followed by an immediate test to see how well they could recognize the meaning of the words. The next day, a delayed test was conducted to measure how well they retain the memory of the words.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study recruited 202 undergraduate students aged from 19 to 24 (Mean =21.47, SD =1.39) at XXX University. 19 participants, who reported having some or extensive knowledge of Chinese characters, were excluded from the final analysis that included a total of 183 participants. They were native speakers of English, with no prior knowledge or minimal prior exposure to Chinese. They were randomly and equally assigned to one of the four experimental conditions.

2.2. Materials

The stimuli consisted of 48 Chinese characters selected for their visual simplicity and structural variability. These characters were grouped into 24 pairs: 12 pairs of identical strokes but different stroke structures (e.g., 人 and 入) and 12 pairs only differing by one stroke (e.g., 日 and 旦). Specifically, in the identical-stroke condition, characters like 人 and 入 share identical strokes but differ in their orientations, forming distinct characters. In the different -stroke condition, characters like 日 and 旦 differ by one single stroke. Each pair was presented alongside an English translation to facilitate learning and recognition. The average stroke number for the identical-stroke condition was 3.5 (SD = 0.9) while for the different-stroke condition, the average stroke number was 3.92 (SD = 0.79) and 4.92(SD = 0.79) respectively. There was no significant difference in stroke number between these two conditions (t =0.001, p =.999).

To measure visual complexity of Chinese characters, we compared the four metrics Wang et al. (2014) proposed, namely stroke count, ink density, stroke frequency, and perimetric complexity, among which, the perimetric complexity was the one that could best be applied to both alphabets and Chinese characters. This metric was defined as the perimeter square of a symbol, divided by the ‘ink’ area (Pelli, Burns, Farell, & Moore-Page, 2006). The width and height of the characters were the same and they were treated as an image with fixed size. Each character was stored as a binary image, with the strokes in black background in white. The ink density is defined by the ratio of the number of black and the total number of pixels in a character image. An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare perimetric complexity between the identical-stroke and different-stroke conditions. There was no significant difference (t(46)=0.39, p = 0.969) between the identical-stroke condition (M = 0.51, SD =0.16, n = 24) and the different-stroke condition (M =0.59, SD = 0.11, n = 24).

2.3. Design and Procedure

At the initial stage of learning Chinese characters, a common approach is to introduce new characters alongside their pinyin (a pronunciation cue) and English equivalent. Research by Lee and Kalyuga (2011a) found that presenting pinyin with new words improved word retention for learners who had achieved automatic pinyin reading but provided little benefit for those who had not yet mastered the pinyin system. Additionally, the widely used horizontal layout for presenting pinyin can impose a high cognitive load and hinder character learning, particularly for beginners (Lee & Kalyuga, 2011b). To avoid potential confounding factors, the present study excluded pinyin and phonological information during the training phase.

This study employed a 2x2x2 design with two between-subject variables: presentation style (massive presentation vs simultaneous presentation, i.e., one character vs. two characters) and color coding (with vs. without color cues). Stroke number (identical-stroke vs. different-stroke) was treated as a within-subject variable. Thus, in total, there were 4 training conditions.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four training conditions presented in

Figure 1:

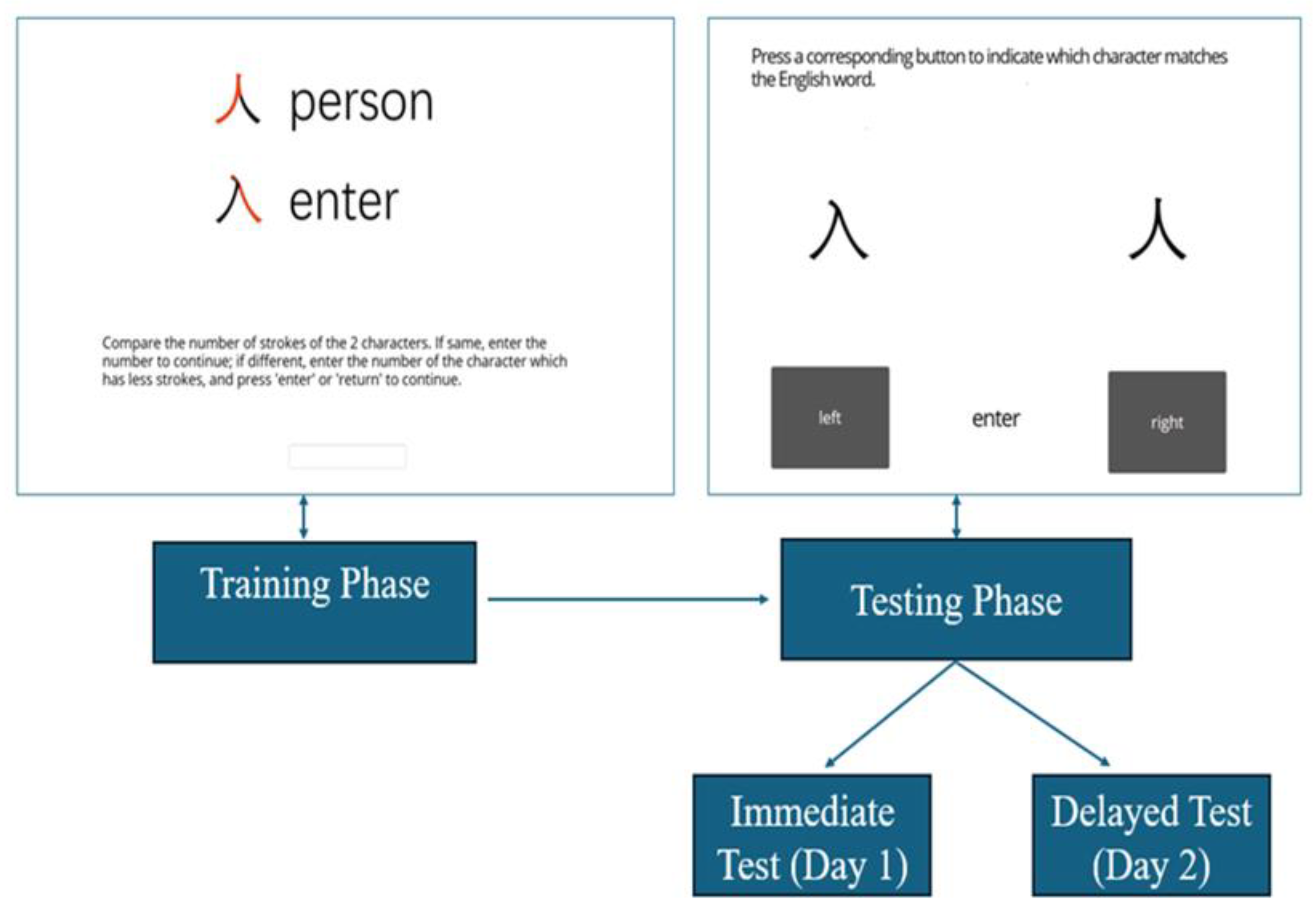

This study was conducted online using the Gorilla Experiment Builder (

www.gorilla.sc; Anwyl-Irvine et al., 2021). First, a questionnaire was designed to gather participants’ Chinese learning background. The experiment comprised of two phases: a training phase and a testing phase. During the training phase, participants were exposed to Chinese characters based on their assigned conditions. They were instructed to observe each character, count the number of strokes, and enter the stroke number before advancing to the next trial. No feedback was given during this phase. Each character was displayed for a fixed duration, and participants pressed a button to proceed to the next trial.

The testing phase involved two recognition tests: an immediate test on Day 1 and a delayed test 24 hours later Day 2. Both tests used a two-alternative forced-choice task, where participants were shown an English translation and asked to identify the corresponding Chinese character from two options. Each test included 48 trials including all the new characters learned during the training phase. The study followed a between-subjects design, ensuring that each participant experienced only one training condition.

Figure 2 illustrates the training phase of the “Two Characters, Color-Coded” condition, while the testing phase was the same for all conditions.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015) within the R statistical software environment, maintained by the R Core Team (2020). In these analyses, accuracy and reaction times (RT) for each trial were treated as dependent variables. A linear mixed-effects model was applied, with stroke number, color cue, and presentation type as fixed-effect predictors. The coding for these predictors was as follows: different- stroke (0.5) vs. identical-stroke (-0.5), presence of a color cue (C) (0.5) vs. absence of a color cue (NC) (-0.5), and massed presentation (one character) (0.5) vs. simultaneous presentation (two characters) (-0.5). The random effect structure included varying intercepts and slopes for both participants and items, with no initial correlation assumed between these intercepts and slopes. In the event of convergence issues, the models were adjusted by removing random terms sequentially, starting with the term having the smallest value (Barr et al, 2013).

Before conducting the analysis, we used a density plot to visualize response times (RTs) and identify potential outliers. RTs below 300 ms or above 1,0000 ms were considered outliers and were excluded from the dataset. Based on the results of Box-Cox tests (Box & Cox, 1964), a logarithmic transformation was applied to the RTs, and the transformed values were used as the dependent variable. The initial model was fitted to the complete dataset, and subsequently, following the residual trimming method proposed by Baayen et al. (2008) and Baayen & Milin (2010), data points with residuals exceeding 2.5 standard deviations were removed. The final results are based on the refined model. For response accuracy, generalized linear mixed-effects models were used, with accuracy coded as 1 (correct) or 0 (error) as the dependent variable. These models were structured similarly to those used in the RT analysis. (Do we need to specify the data availability statement here?)

4. Discussion

This study aims to determine whether visual complexity of characters with identical stroke number or different stroke number poses the same level of challenge to L2 Chinese learners and understand an optimal way to present input (i.e., Chinese characters) by empirically testing two strategies: color coding and presentation style. Specifically, we aim to understand whether and how these strategies can be applied to visually similar Chinese characters during the early stage of character learning. We employed an online training and testing approach to examine how L2 Chinese beginning learners retain visually similar words under different training conditions: with or without color coding and presented either simultaneously or in a massed format. The current study also compared the retention of visually similar word pairs of identical strokes to those of different strokes. Results from both Immediate tests and Delayed tests revealed a consistent pattern: word pairs of different strokes were better retained than word pairs of identical strokes, as evidenced by both accuracy and RT analyses. The presentation style showed no main effect either in Immediate tests or Delayed tests analysis. However, in the accuracy analysis, the interaction effects showed that words with word pairs of a different-stroke number were recognized more accurately than identical-stroke words in the massed presentation condition, but not in the simultaneous condition, which suggested that simultaneous presentation enhanced the learning of identical-stroke words more than different-stroke words and leveled the difference between identical-stroke characters and different-stroke characters. This is because simultaneous presentation encourages learners to compare the stroke structures of identical-stroke words, which is consistent with the structure mapping theory (Gentner, 1983; Namy & Gentner, 2002; Thompson & Opfer, 2010). Color coding showed no main effects in accuracy analysis in either immediate tests or delayed tests. However, the RT analysis showed that the use of color cues slowed down word recognition in both immediate tests and delayed tests.

To address the first research question, we examined which type of visually similar word pairs—identical-stroke or different-stroke—is easier to learn. By logic, the addition of a stroke increases the overall stroke count, which, according to the conventional measure of visual complexity, should make these words more difficult to learn and retain. However, the results contradicted this expectation, revealing that words with identical stroke numbers were harder to remember. Shen (2013) suggests that beginning L2 learners often struggle to recognize the internal structures of characters and require sufficient time and practice to segment compound characters into their constituent parts effectively. The current study further explores how well beginners can identify the stroke counts and internal structures of characters, through exposure and practice such that they could visualize and familiarize themselves with basic character components. As Reder et al. (2016) have noted, novice learners can accurately decode characters with minimal training, especially in controlled laboratory settings. This ability may enhance their capacity to differentiate characters with different stroke counts, as these characters share most of their stroke structure except for one stroke. In contrast, for words with identical strokes, the stroke structures are different even though they share the same number of strokes. Our results indicated that word pairs with identical strokes, but different stroke orientations were harder to learn than those with additional-stroke differences. This difficulty might stem from the more subtle differences in identical-stroke words, which require higher visual processing skills. As Wang, Koda, and Perfetti (2003) have highlighted, the complex, square-shaped structure and high spatial frequency of Chinese characters place significant demands on spatial memory. This may impose an additional processing burden when learning and retaining identical-stroke words compared to different-stroke words. McBride-Chang et al (2005) found a positive correlation between visual-spatial abilities and the acquisition of Chinese characters. Thus, visual working memory is crucial for learning Chinese characters, as it allows for the temporary storage of approximately three to four visual objects (e.g., Luck, 2008; Luck & Vogel, 2013). This implies that the average capacity for remembering items or features is quite limited. In our study, the characters selected averaged 3-4 strokes, which falls within the capacity of visual working memory. According to Zimmer & Fisher (2020), even native Chinese speakers rely on visual working memory rather than semantic information when memorizing trained characters and pseudo-characters whose one radical were altered from real characters. Zimmer and Fisher (2020) found in Experiment 4 that highly conceptually similar distractors did not increase memory errors, while visually similar distractors weakened memory performance. It can be inferred that beginners would primarily use visual-spatial memory to memorize Chinese characters. The current study is the first to show that characters of the same number of strokes, but different spatial orientations are more challenging to learn compared to visually similar characters of different stroke numbers.

Second, presentation style showed no main effects. However, the interaction effect indicated that simultaneous presentation facilitated learning identical stroke characters more than the different stroke characters. That the highest accuracy rate was observed in the massed presentation of characters with different strokes, whereas the lowest accuracy rate was in the simultaneous presentation with identical strokes. To elaborate, when characters were presented one by one, learning different-stroke pairs resulted in higher accuracy compared to identical-stroke pairs. Conversely, in the simultaneous presentation condition, no significant difference was found between identical-stroke and different-stroke pairs. This suggests that the simultaneous presentation format helped reduce the difficulty associated with learning characters of identical strokes and thus reduced the difference between identical-stroke characters and different-stroke characters. As previously noted, simultaneous presentation allows learners to directly compare the stroke patterns of two characters, enhancing learning efficiency. In contrast, massed presentation may increase cognitive load by requiring learners to process two elements presented in random order and integrate them later, which can strain working memory (Chandler & Sweller, 1992, 1996; Kalyuga et al., 1999, 2000). Shen (2005, p. 56) identified learners’ common strategies such as “paying attention to graphic structures” and “visualizing the graphic structure of the character”. This study provides strong evidence that simultaneous presentation significantly improves beginning learners’ ability to learn the identical-stroke words via comparing the graphic structures. Next, in the massed presentation condition, the RT analysis revealed that colored characters led to slower responses compared to the no-color condition. In contrast, during simultaneous presentation, there were no significant differences in RT between the colored and no-color conditions, irrespective of whether the tests were immediate or delayed. The analysis also suggested that while color exerted a slight influence on response times, simultaneous presentation seemed to mitigate the effects of color on response times. Additionally, the results of our study were consistent with a large number of studies that have shown that viewing multiple instances simultaneously enhances generalization (e.g., Gentner, et al., 2009; Oakes & Ribar, 2005; Vlach et al., 2012). For example, Vlach et al. (2012) found that 2-year-old children who were exposed to stimuli simultaneously outperformed their peers who were in spaced or massed conditions on a novel noun generalization task when tested immediately afterward. The researchers suggested that the simultaneous presentation condition likely reduced forgetting and memory load, allowing learners to engage more readily in comparative mental processes during learning. Since all instances were visible throughout the learning phase, children in the simultaneous condition didn’t need to mentally retrieve previous instances they had observed. In summary, simultaneous presentation might help beginners retain the memory of visually similar characters, but it is inconclusive to draw this conclusion because the main effect was not significant.

Finally, we applied a color cue to highlight the stroke distinguishing the paired-characters and found that the color cue increased recognition reaction times in both the immediate tests and delayed tests. The design of the color cues aimed to guide learners’ visual focus towards the differential stroke structure within characters. Nonetheless, the use of color might inadvertently introduce a negative effect by acting as an additional distraction. The intricate visual information could potentially compel participants to engage in an extra process of matching radicals with colors, resulting in a divided attention effect. As a result, this could adversely affect learners' character acquisition process. These findings align with Hou and Jiang (2022), who reported that radical marking using color or animation increased RT and reduced recognition accuracy in character recognition tasks. They suggested that providing radical and stroke information might interfere, rather than facilitate character learning. Our study supports this view, indicating that excessive visual information introduced during the learning process may increase cognitive load for L2 learners, thereby reducing learning effectiveness (Baddeley, 1992). When learners process multiple elements of information simultaneously, they must divide their attention across all elements. This simultaneous presentation of information can result in the split attention effect (Chandler & Sweller, 1991, 1992; Owens & Sweller, 2008), further straining working memory capacity. Thus, the color cue did not facilitate learning characters in our study, which may have important pedagogical implications for L2 instruction.