1. Introduction

Mastitis is among the most important health concerns of farm animals, causing massive financial damage to the agro-livestock sector of Pakistan [

1]. Besides our local dairy production system, mastitis is also the most expensive and common disease, and the financial damages due to mastitis in dairy cattle are estimated at

$185/cow/annum in the United States of America [

2]. These individual losses aggregate more than 2 billion dollars per annum in the USA. The damages are in the terms of discarded unwholesome milk from the effected quarters and as the result of antibiotic administration, replacing cost of the cow with effected udders, additional labor for mastitis management, antibiotic and miscellaneous treatment expenses, veterinary health care services, and above all, milk losses of the cows harboring sub-clinical mastitis, which leads to two-thirds of damages due to mastitis. On factual grounds, each quarter infected during lactation could decrease the milk production of a cow by around 10 to 12% [

3]. Subjectively, the annual financial damages of 1.1 billion, 2 billion, 371 million, and 35 billion (USD) have been ascertained in India, the USA, the UK, and the rest of the global dairy industry due to mastitis [

4].

Bovine mastitis is a disorder of udder tissues caused by infectious agents that enter the cisternal gaps and teat duct; these infectious agents develop affiliations with the internal tissue linings of the udder for a long period, having negligible effect of routine milk flushing during multiple daily milking of the lactation period. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae have a strong affinity to adhere udder’s internal linings and cisternal gaps, while E. coli has the minimal adhering, swift proliferative properties by generating the least somatic cell count. Bacteria, in the beginning, impact the tissues lining of major milk-collecting tubules and cisternal gaps by causing morbidity in the small patches. Afterward, these infectious agents gain access to the deep small ducts and alveoli of the lower parts of the udder, possibly after proliferation and lactation currents generated by the movement of the cow. The host’s immunological response against invaded bacteria leads to infection, resulting in increased white blood cell count in the milk. Before the onset of infection, udder tissues release macrophages as the main immunological cell that plays a role in the detection of nonspecific infectious invaders. After finding infectious invaders, macrophages release chemical mediators to attract polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocytes (PMN) from the blood vessels towards the site of infection. These PMNs start increasing in numbers, and firstly accumulate around alveolar tissues, to the alveolar, ductal, and cisternal lumina to act, surround, and eradicate the invading infectious agents. Inflammatory response triggered in response to host pathogen interaction is carried out due to the production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukins, and interferons [

3].

Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) is an autologous blood fraction harvested from the blood of the same animal for higher concentrations of platelets, mostly 3 to 4 times of basal platelet count, with the help of centrifugation and filtration. The active component of PRP is thrombocytes, which are membrane-bound cellular fragments along with various growth factors found in alpha and dense particles. The ideology behind the usage of PRP revolves around the local deposition of enriched and activated growth factors to the target anatomical structures [

5]. Various studies have documented that revolved around specific growth factors of PRP, including hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF-basic), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), transforming growth factor (TGF), endothelial growth factor (EGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [

6]. VEGF, PDGF, and FGF-basic are involved in chemotactic and pro-antiproliferative actions [

7]. HGF is involved in the mitosis of endothelial cells [

8]; IGF-1 is a chemical mediator for the growth and healing of musculoskeletal tissues [

9]. EGF could provoke the formation of tubules, endothelial cell production, and migration [

8] (Martínez et al. 2015) while TGF is involved in chemotactic and anti-angioproliferative activities [

7].

Clinical mastitis is responsible for heavy losses to the dairy industry around the globe by decreasing production performance permanently. This disease is being managed with antibiotics that are causing animal and human health hazards with antibiotic residues and antibiotic resistance. Furthermore, these antibiotics cannot encourage regeneration of secretory cells to meet the performance deficit of the udder. This study aims to assess the performance of PRP for the management of bubaline mastitis both in vivo and in vitro.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diagnosis of Mastitis

A thorough diagnosis of mastitis was carried out by performing a clinical examination of the animal (Rectal Temperature, Pulse rate, breathing rate, capillary refill time, ruminal motility rate, and any gross findings on the entire skin), digital manipulation of the udder (Swelling, redness, hotness, pain response and presence of any ulcer or wound on teat and udder) and quantity and quality assessment (presence of chunks, flakes, blood, and discoloration) of milk sample collected from the udder of suspected animal. Additionally, the milk sample was evaluated by the California Mastitis Test as per the description of Sargeant and colleagues [

10]

. Depending upon the data recorded from the aforementioned clinical findings, the animal was declared to be suffering from mastitis.

2.2. Selection of Animals

Thirty buffaloes were enrolled in this study plan after confirmation of clinical mastitis. Previously, these buffaloes were used to sell their milk to the local market. So, their milk yield history was maintained to deal with the financial aspects of milk sales. These buffaloes were divided into three treatment groups, i.e., PRP group (Group 01), PRP and antibiotic group (Group 02), and only antibiotic group (Group 03). For each group, (n=10) animals were assigned to each treatment.

2.3. PRP Preparation

Chang et al. (2018) reviewed different methodologies for the preparation of PRP and summarized the whole procedure into 8 different steps. These steps include: 1) 10 to 50 ml blood collection, 2) initial centrifugation at 100-1000 g for 5-20 minutes at 22-24º C, 3) plasma aspiration with or without buffy coat, 4) final centrifugation for 5-20 minutes at a greater rate than the initial centrifugation, 5) removal of Platelet Poor Plasma i.e., 1/3 part from the top, 6) re-suspension of platelets in the rest of plasma with or without supplementing anticoagulant, 7) activation of PRP and, 8) administration of PRP in the target site (Chang et al. 2018). For the current study, PRP preparation was slightly modified from this procedure. For one mastitis test, a sample of 25.5 ml blood was collected aseptically from the jugular vein of each buffalo in a 50 ml syringe. Afterwards, 22.5 ml blood sample was transferred to 5 plain vacutainers of 5 ml volume in which 0.5ml sodium acid citrate was added as an anticoagulant for PRP preparation while 3 ml blood was transferred to a 3ml EDTA vacutainer for baseline thrombocyte estimation from District Diagnostic Laboratory (DDL), Nankana Sahib, Livestock and Dairy Development Department, Government of Punjab. After transferring the blood sample, the vacutainers were gently shaken to ensure proper mixing of the anticoagulant with the blood sample. The 5 vacutainers containing 5 ml anticoagulated blood in each were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 200 g, separating the blood into three fractions, i.e., blood plasma, leukocyte concentrate, and erythrocyte concentrate in the top, middle, and lower layers, respectively. The blood plasma with leukocyte concentrate was aspirated and re-centrifuged at 300 g for 10 minutes for isolation of Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) from Platelet Poor Plasma (PPP). 1.5 ml PRP was harvested from 22.5 ml of whole blood. The number of platelets in whole blood and PRP was assessed by an automatic blood analyzing machine (MYTHIC-18 VET, Manufactured by ORPHEE S.A., FRANCE). For the first three treatments, an analysis of blood and PRP was performed to standardize the technique, while the rest of the blood samples were harvested on the same technique without any blood and PRP analysis.

2.4. PRP Administration

After preparation, the PRP was collected in a 5 ml Disposable Syringe for infusion. The selected animal was properly restrained with milking hobbles. The affected teat was prepared with thorough cleaning with disinfectants before administration. A human intravenous cannula of 20 G was attached with a PRP syringe inserted in the teat canal and deposited there slowly. Afterward, a gentle massage was performed in an upward direction towards the udder while keeping the teat opening closed with digital pressure.

2.5. In Vitro Efficacy of PRP

Three samples of milk and blood from Group 01 and 3 samples from Group 02 were sent to the District Diagnostic Laboratory for in vitro study of PRP. The efficacy of PRP for this study was evaluated by two methods:

1- A milk sample was spread over the agar plate (Iso sensitest agar) and two fine droplets of PRP were placed on the peripheral margins of the center of agar plate and incubated at 37ºC for 24 hours. Antibacterial activity of PRP was evaluated in terms of Zone of Inhibition (ZI).

2- A milk sample was mixed with PRP in equal amounts and spread over the agar plate and incubated at 37º°C for 24 hours. The growth pattern was compared with a control microbial culture that was performed with the same milk samples without the addition of PRP. The growth pattern of PRP-treated plates was compared with the control and defined as No Growth, Equal Growth, Less Growth, and Higher Growth.

2.6. Antibiotic Selection

Milk samples of Group 02 and Group 03 were sent to DDL for microbial culture and antibiotic susceptibility test to select a suitable antibiotic for intra-mammary infusion alone and in combination with PRP. The interpretation of the Zone of Inhibition of Antibiotics was expressed as Susceptible (S), Resistant (R), and Intermediate (I) based on the microbial growth pattern on the culture media.

2.7. In Vivo Efficacy of PRP and Antibiotics

After laboratory results, target buffaloes were infused with PRP, PRP and Antibiotics, and Antibiotics alone in the affected quarters of udders of the respective treatment groups through the intra-mammary (IMM) route. Before and after administration, a thorough teat antisepsis was performed with approved detergents and paper towels. The therapy was infused once a day for three consecutive days in all treatment groups.

2.8. Supportive Treatment:

As supportive treatment for all groups, the following treatment was done:

I) Non-steroidal inflammatory (NSAID) drugs i.e., Flunixin meglumine at the dose rate of 2.2 mg per kilogram of body weight through the intravenous route once a day for three days.

II) Application of cold therapy with ice packs for 10 minutes twice a day for 3 days.

III) Complete removal of milk by intramuscular (IM) administration of 10-20 IU of Oxytocin twice a day for 3 days.

2.9. Follow Up the Evaluation of Mastitis and Data Collection

During this study, the complete milk was recovered twice a day with hand milking. A feedback system was developed between the instigator and owners for proper reporting of data daily. The PRP administration and CMT were performed by the investigator or under the supervision of the investigator in the field and in the veterinary facility. CMT was performed on a daily basis during the first seven days and then once on the 15th day.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The data collected during this study will be interpreted statistically using One-way ANOVA by SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 23.0). Correlation and regression analysis were performed using R Studio version 4.0.2. Optimization was performed using response surface methodology via central composite design using Design Expert version 12.

3. Results

In this study, 30 animals were divided into three groups, i.e., Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3, with 10 animals in each group.

3.1. Group 1: Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP)

In this group, 10 buffaloes were treated with PRP intra-mammary. The healing process and infection intensity were checked by CMT. The recovery rate of this group is significantly better than the antibiotic group; however statistically non-significant difference was found between the PRP and PRP + antibiotic groups.

3.2. Group 2: PRP+ Antibiotic:

In this group, 10 buffaloes were treated with PRP + selected antibiotic based on culture sensitivity test results. The infection intensity improved faster than in the other groups. The recovery rate is significantly better than the other two groups.

3.3. Group 3: Antibiotic

In this group, 10 buffaloes were treated with a selected antibiotic through the intramammary route. The recovery rate is statistically nonsignificant than the other two groups.

3.4. Intensity of Infection

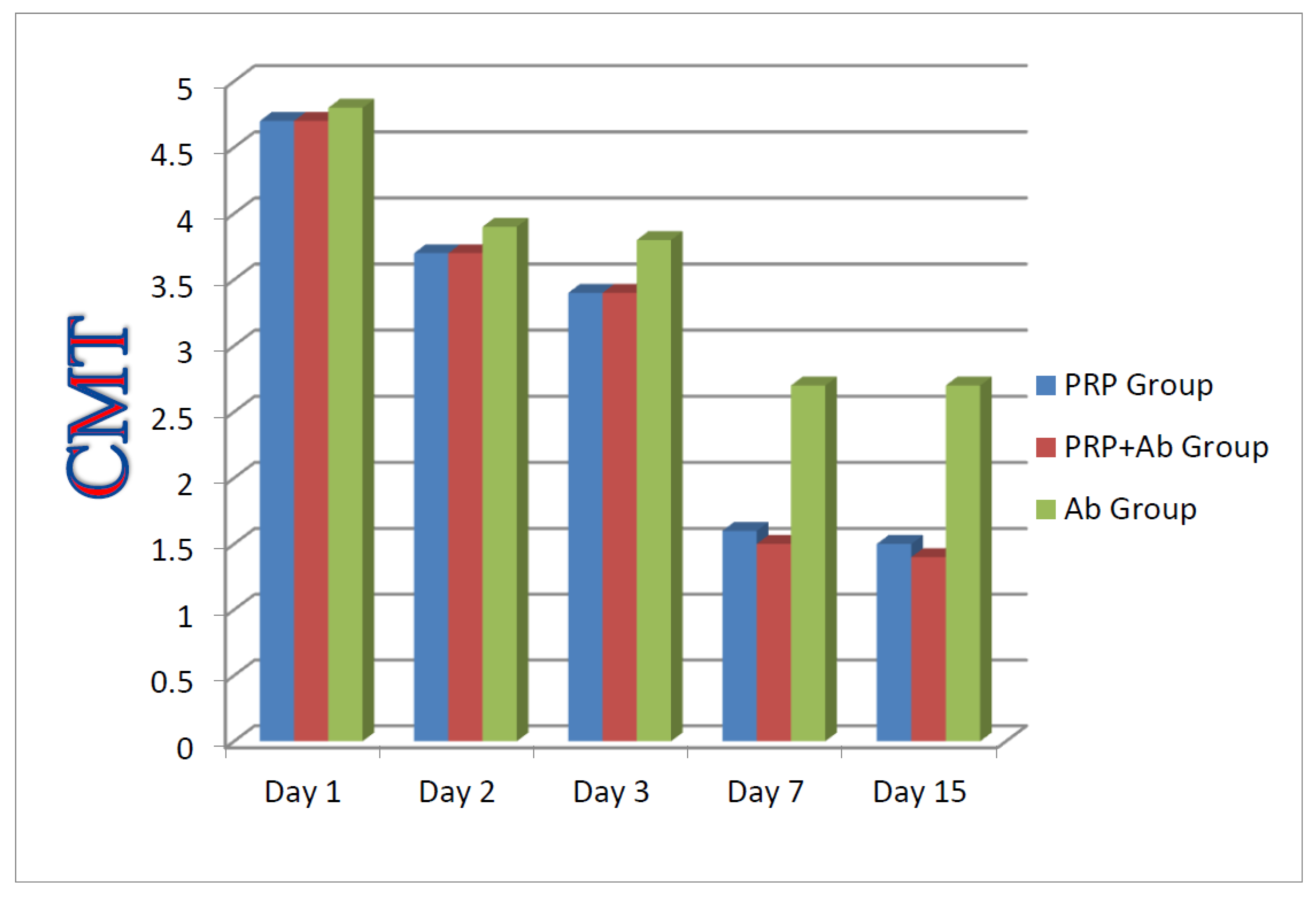

The grading for the intensity of infection of PRP, PRP +Antibiotic, and Antibiotic groups. The grading was done based on CMT, which shows the improvement in intensity of infection.

3.5. Improvement of Milk Production

The improvements of milk production of PRP, PRP +Antibiotic, and Antibiotic groups revealed no significant difference (P>0.05) between the groups in terms of MP% AT day 15.

3.6. In Vitro Efficacy of PRP

To ascertain the in vitro efficacy of PRP according to method number 1 described in the materials and methods section, no significant difference was noticed in terms of zone of inhibition. When the milk samples were mixed with PRP in equal amounts and spread over culture media and incubated at 37ºC for 24 hours, a reduced growth pattern was noticed in comparison with the control group.

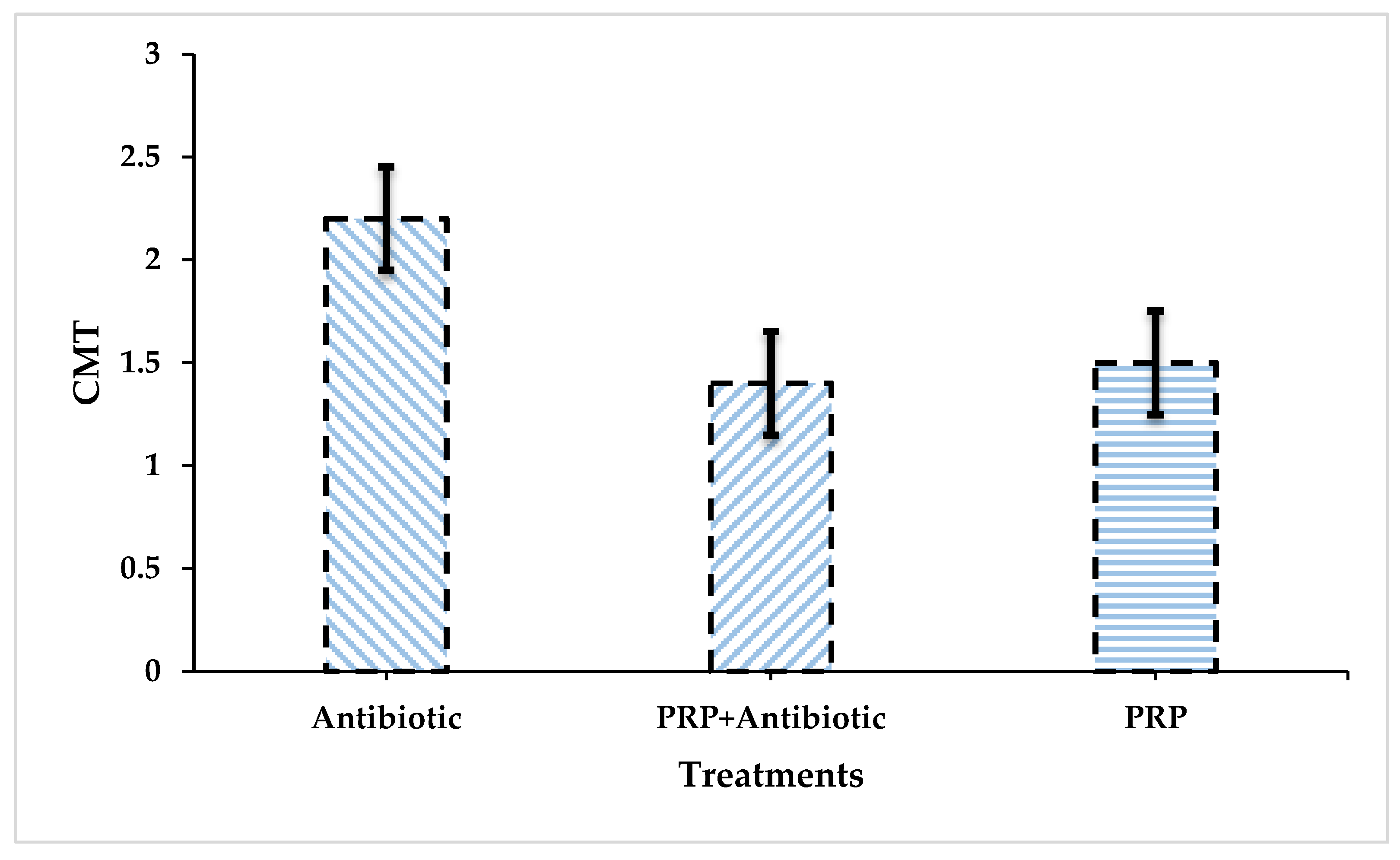

The comparison of the Antibiotic group with the PRP + Antibiotic group revealed that the significance value is 0.02, which is the most significant figure among all groups. Similarly, the comparison between the Antibiotic and PRP groups yielded a less significant value, i.e., 0.047. Contrary to this, the comparison between PRP and PRP+ Antibiotic Group is insignificant (P = 0.932).

As per statistical analysis, the treatment plan with PRP + Antibiotic had significantly superior performance (P<0.05) compared with the Antibiotic Group. No significant difference was yielded by the statistical analysis when a comparison was executed between the PRP and PRP + Antibiotic Group.

Figure 1.

Comparison between all groups regarding the average values of CMT findings at 1,2,3,7, and 15 days post-treatment.

Figure 1.

Comparison between all groups regarding the average values of CMT findings at 1,2,3,7, and 15 days post-treatment.

Figure 2.

Comparison between all groups regarding the mean values of CMT findings at 15 days post-treatment.

Figure 2.

Comparison between all groups regarding the mean values of CMT findings at 15 days post-treatment.

Table 1.

Percentage of milk yield improvement of PRP, Antibiotic + PRP, and Antibiotic groups at 15 days post-treatment.

Table 1.

Percentage of milk yield improvement of PRP, Antibiotic + PRP, and Antibiotic groups at 15 days post-treatment.

| PRP Group |

*Improvement in milk yield |

Antibiotic + PRP Group |

Improvement in milk yield |

Antibiotic Group |

Improvement in milk yield |

| G 1/1 |

75% |

G 2/1 |

100% |

G 3/ 1 |

75 % |

| G 1/2 |

50% |

G 2/2 |

100% |

G 3/ 2 |

100% |

| G 1/3 |

100% |

G 2/3 |

75% |

G 3/3 |

50% |

| G 1/4 |

25% |

G 2/4 |

100% |

G 3/ 4 |

100% |

| G 1/5 |

75% |

G 2/5 |

100% |

G 3/ 5 |

100% |

| G 1/6 |

50% |

G 2/6 |

75% |

G 3/6 |

75% |

| G 1/7 |

75% |

G 2/7 |

75% |

G 3/ 7 |

50% |

| G 1/8 |

100% |

G 2/8 |

100% |

G 3/ 8 |

75% |

| G 1/9 |

75% |

G 2/9 |

75% |

G 3/ 9 |

75% |

| G 1/10 |

75% |

G 2/10 |

100% |

G 3/ 10 |

50% |

3.7. Milk Production (MP% %)

At day 15, MP% values of groups Antibiotic, Antibiotic + PRP, and PRP were 75.00±20.41, 90.00±12.90, and 70.00±22.97, respectively. No significant difference (P>0.05) was observed between the groups in terms of MP% at Day 15

Table 2.

Comparison of MP% values between groups at day 15.

Table 2.

Comparison of MP% values between groups at day 15.

| Groups |

Mean ± SD |

P-value (P<0.05) |

| Antibiotic |

75.00 ± 20.41 |

0.071 |

| PRP + Antibiotic |

90.00 ± 12.90 |

| PRP |

70.00 ± 22.97 |

3.8. Relationship of PRP with Antibiotics Against Bubaline Mastitis

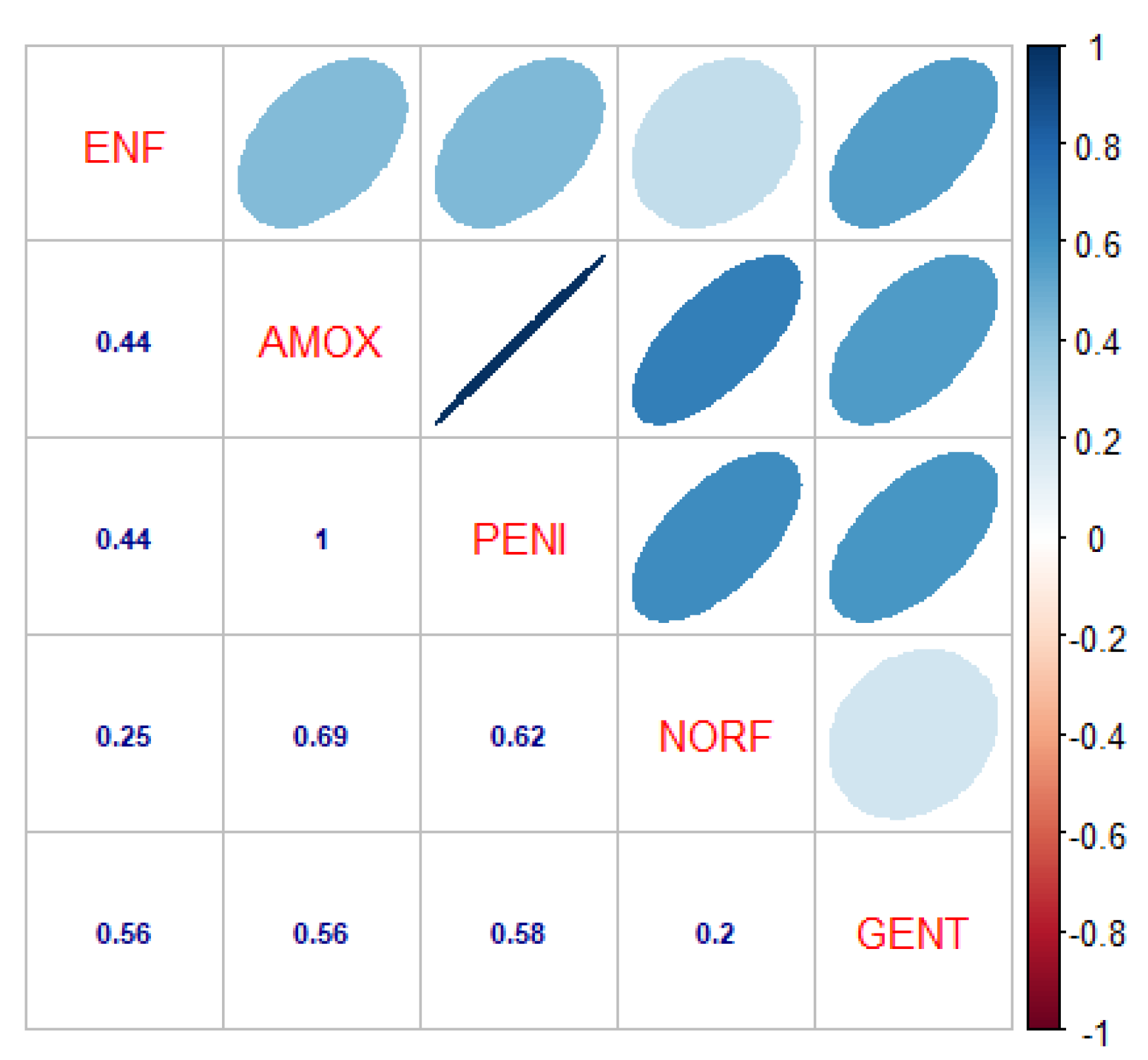

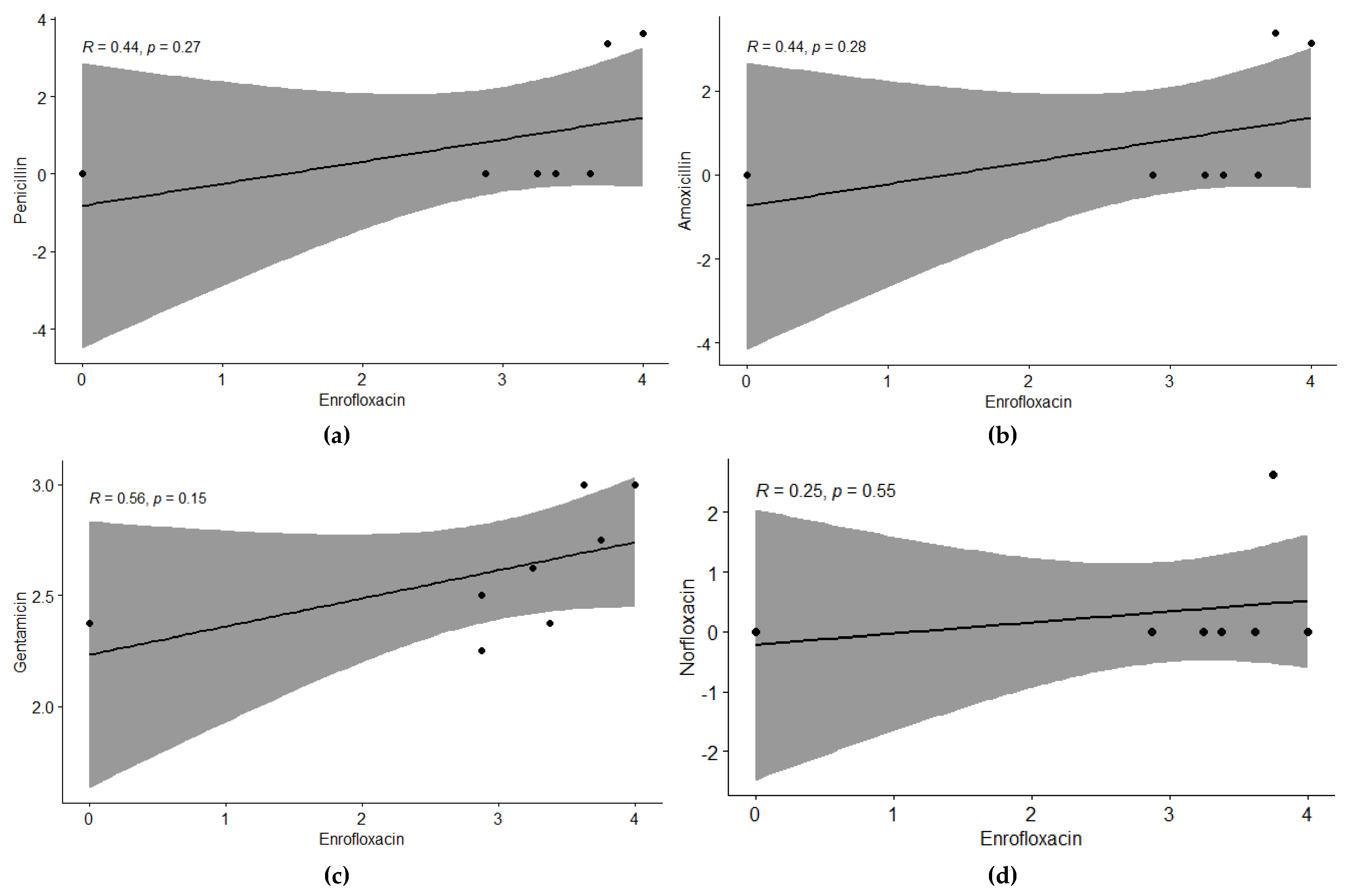

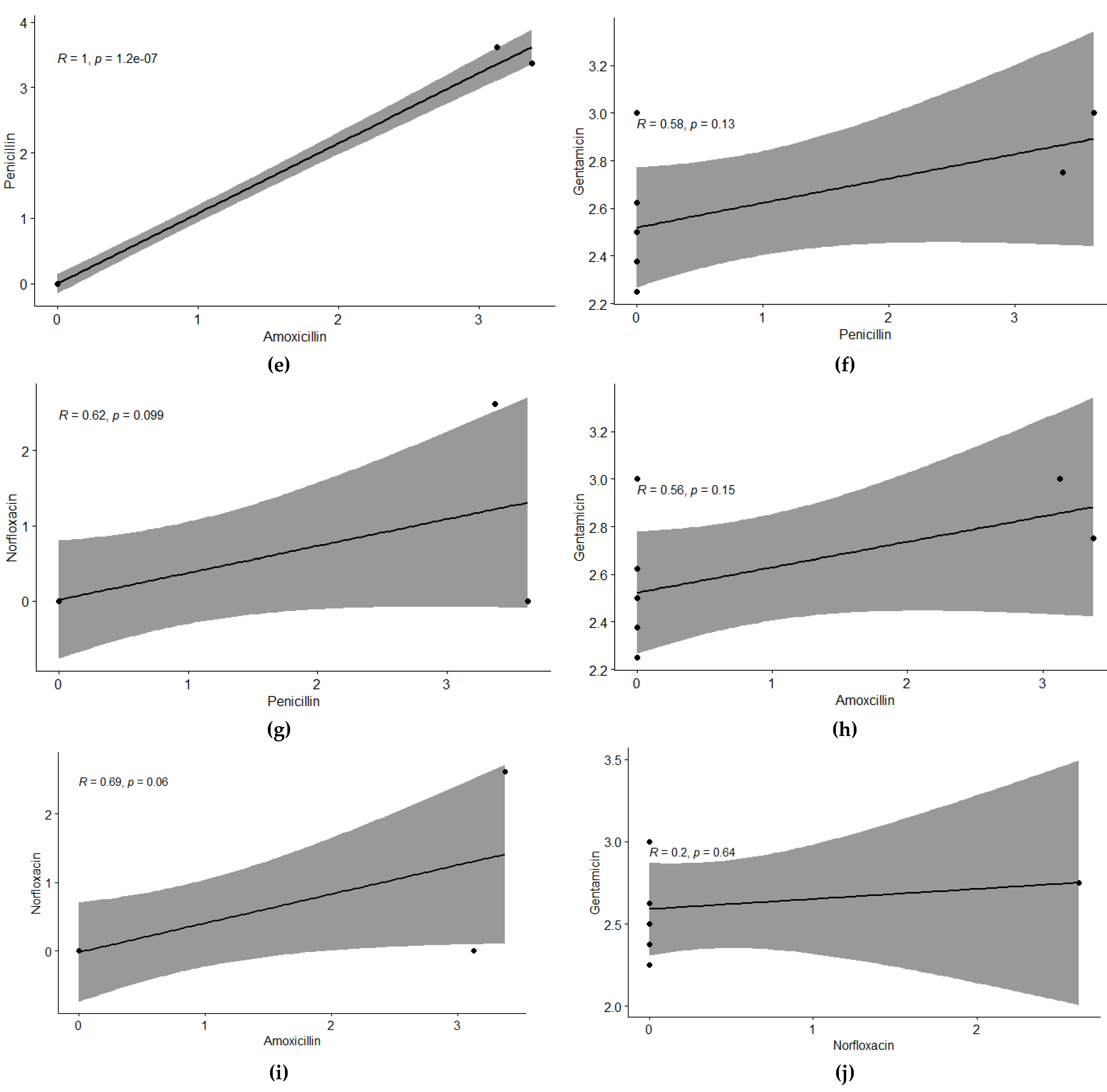

For studying the relationship of tested antibiotics against bubaline mastitis, a significant and positive correlation was observed at 5% level of significance. Enrofloxacin showed positive correlation with all other antibiotics, with correlation values of r: 0.44 with Amoxicillin and Penicillin, r: 0.25 with Norfloxacin, and r: 0.56 with Gentamycin. Amoxicillin showed positive and significant correlation with Penicillin r: 1.00, r: 0.69 with Norfloxacin, and r: 0.56 with Gentamycin. Penicillin showed positive correlation with Norfloxacin and Gentamycin, with correlation values of 0.62 and 0.59, respectively. Gentamycin showed a positive correlation with Norfloxacin with r: 0.2. This trend has also been depicted with regression analysis, showing a similar trend at 5% level of significance.

Figure 3.

Correlation of antibiotics tested against Bubaline Mastitis. The digits in blue depict, and the ellipses illustrate the r - r-value (correlation value) of the tested antibiotics. ENF: Enrofloxacin, AMOX: Amoxicillin, PENI: Penicillin, NORF: Norfloxacin, and GENT: Gentamicin. The blue ellipses show a positive correlation among the antibiotics as per the scale mentioned on the right side of the matrix.

Figure 3.

Correlation of antibiotics tested against Bubaline Mastitis. The digits in blue depict, and the ellipses illustrate the r - r-value (correlation value) of the tested antibiotics. ENF: Enrofloxacin, AMOX: Amoxicillin, PENI: Penicillin, NORF: Norfloxacin, and GENT: Gentamicin. The blue ellipses show a positive correlation among the antibiotics as per the scale mentioned on the right side of the matrix.

Figure 4.

Relationship among individual antibiotics tested against Bubaline Mastitis using regression analysis. The regression line shows the extent of correlation among the antibiotics. Regression analysis between (a) Enrofloxacin & Penicillin, (b) Enrofloxacin & Amoxicillin, (c) Enrofloxacin & Gentamicin, (d) Enrofloxacin & Norfloxacin, (e) Penicillin & Amoxicillin (f) Penicillin & Gentamicin, (g) Penicillin & Norfloxacin, (h) Amoxicillin & Gentamicin, (i) Amoxicillin & Norfloxacin and (j) Gentamicin & Norfloxacin.

Figure 4.

Relationship among individual antibiotics tested against Bubaline Mastitis using regression analysis. The regression line shows the extent of correlation among the antibiotics. Regression analysis between (a) Enrofloxacin & Penicillin, (b) Enrofloxacin & Amoxicillin, (c) Enrofloxacin & Gentamicin, (d) Enrofloxacin & Norfloxacin, (e) Penicillin & Amoxicillin (f) Penicillin & Gentamicin, (g) Penicillin & Norfloxacin, (h) Amoxicillin & Gentamicin, (i) Amoxicillin & Norfloxacin and (j) Gentamicin & Norfloxacin.

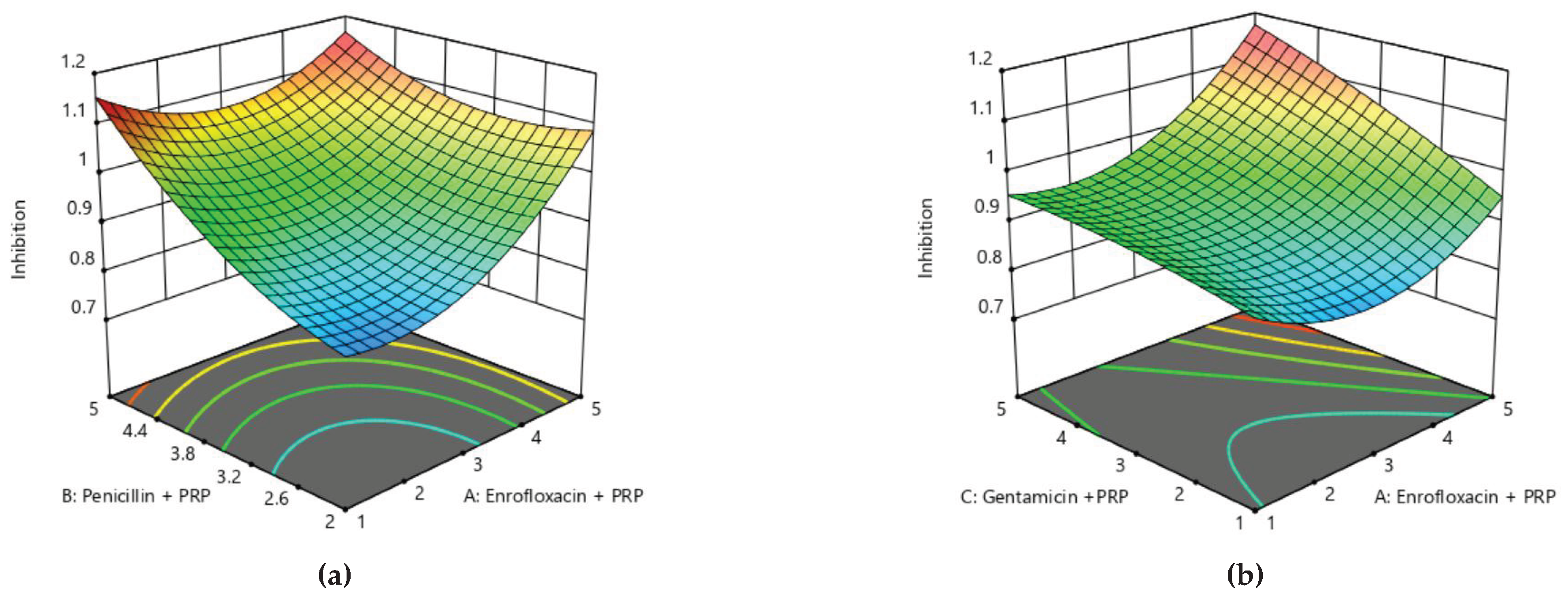

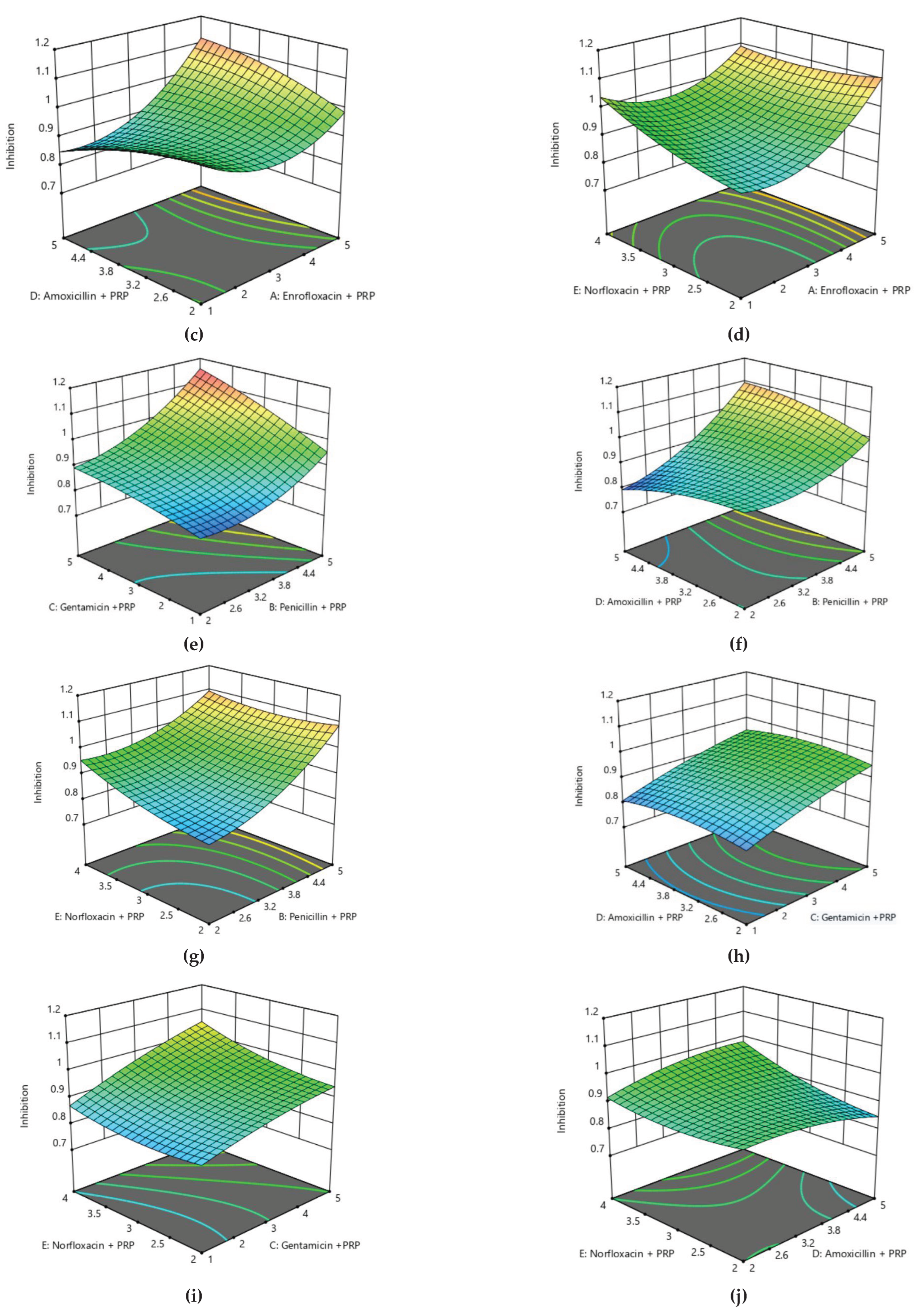

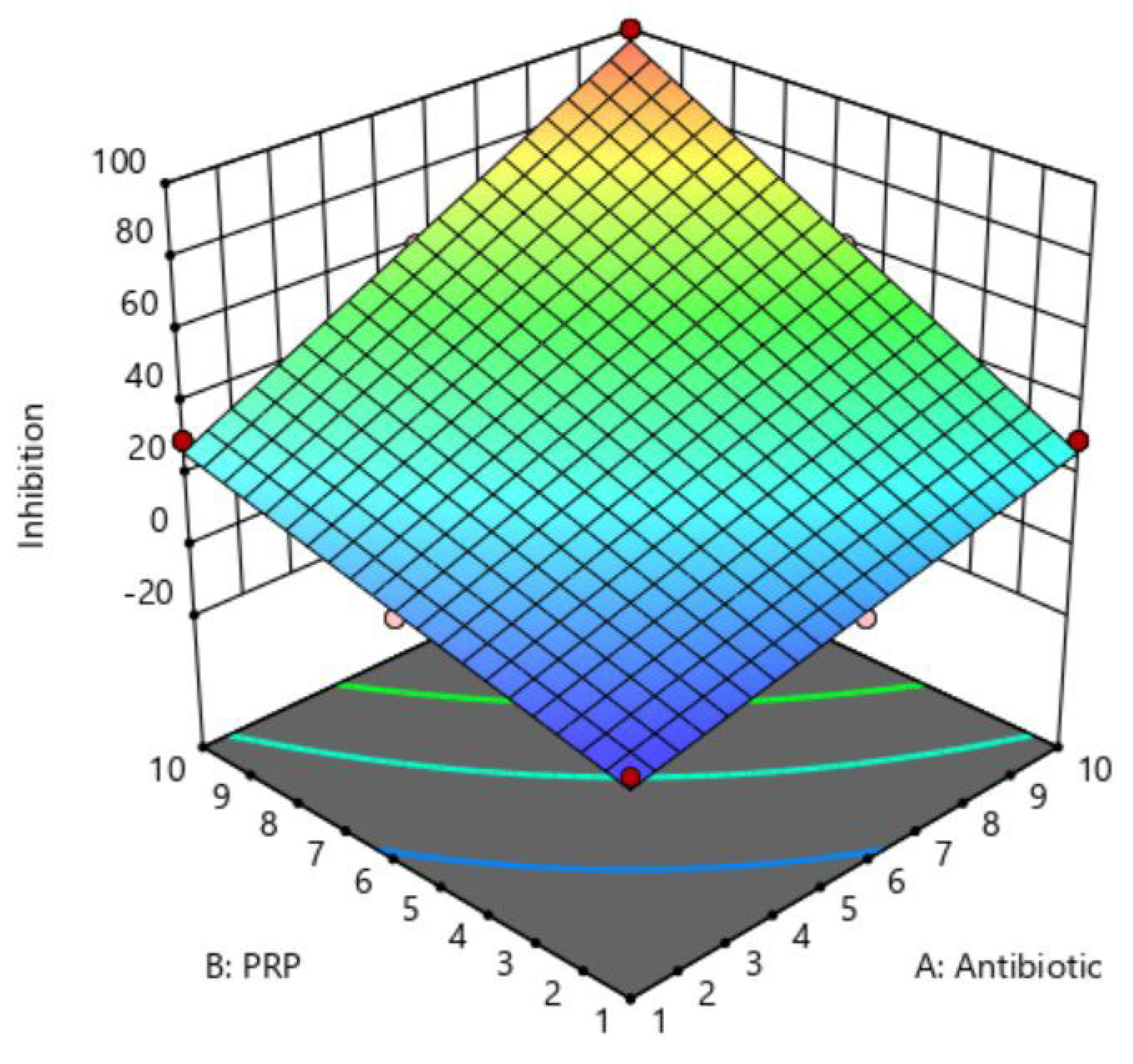

3.9. Optimization of Antibiotics and PRP Treatment Against Bubaline Mastitis via Response Surface Methodology Using Central Composite Design

For all the treatments tested were assessed based on response surface methodology via Central-Composite design. The following equation model was fitted to the data.

where “

Y” was mastitis incidence, “

β0” was the intercept constant, “

βi”, “

βii”, and “

βij” were the regression coefficients. “

Fi”, “

Fj” were coded values of treatments, while “ε” is the error term.

Table 3.

The design approach for determining the optimization of antibiotics & PRP against Bubaline mastitis in Central–Composite Design (CCD).

Table 3.

The design approach for determining the optimization of antibiotics & PRP against Bubaline mastitis in Central–Composite Design (CCD).

| Factors |

Coded Symbols |

Levels |

| –1 |

+1 |

| Antibiotics |

A |

1 |

10 |

| PRP |

B |

1 |

10 |

By applying ANOVA (

Table 4) for the model, it was found to be significant (P

<0.05). It indicated that this model was adequate and reproducible. The effectiveness of antibiotics and PRP predicted by the regression equation was close to the observed ones (R

2 = 0.99). Based on the ANOVA, two independent variables, viz. antibiotics and PRP, had a significant effect on mastitis reduction. In

Figure 5, the zones of optimization are shown in the surface plot to illustrate the effects of independent variables (factors), i.e., antibiotics and PRP, on the dependent variable (response), i.e., inhibition of mastitis. The interactive effect of these treatments was also found to be significant at P<0.05. Runs 3 and 9 of

Table 4 display the maximum reduction of mastitis, while other runs illustrate low reduction, respectively (

Table 5).

3.10. Optimization of Antibiotic Treatment Against Bubaline Mastitis via Response Surface Methodology Using Box Behnken Design

For all the antibiotics which came under investigation along with PRP were assessed based on response surface methodology via Box-Behnken design. The following quadratic response surface model was fitted to the data.

where “

Y” was mastitis incidence, “

β0” was the intercept constant, “

βi”, “

βii”, and “

βij” were the regression coefficients. “

Fi”, “

Fj” were coded values of antibiotics, while “ε” is the error term.

Table 6.

The design approach for determining the optimization of treatments in Box Behnken Design.

Table 6.

The design approach for determining the optimization of treatments in Box Behnken Design.

| Factors |

Coded Symbols |

Levels |

| –1 |

+1 |

| Enrofloxacin + PRP |

A |

1 |

5 |

| Penicillin + PRP |

B |

2 |

5 |

| Gentamicin +PRP |

C |

1 |

5 |

| Amoxicillin + PRP |

D |

2 |

5 |

| Norfloxacin + PRP |

E |

2 |

4 |

For the optimization of antibiotics, analysis of variance was performed via a quadratic model, and mastitis incidence was checked. The following regression equation was obtained.

Inhibition = 0.915 + 0.068 A + 0.101 B + 0.0704 C ‒ 0.00074 D + 0.0342 E ‒ 0.0619 AB + 0.0412 AC + 0.066 AD ‒ 0.0412 AE + 0.031 BC + 0.05 BD ‒ 0.031 BE + 0.00 CD + 0.021 CE + 0.033 DE + 0.091 A² + 0.051 B² ‒ 0.012 C² ‒ 0.023 D² + 0.029 E²

According to this regression equation, Enrofloxacin, Penicillin, Gentamicin, and Norfloxacin showed positive responses, while Amoxicillin showed a slightly negative response. The interaction between all antibiotics was found to be positive except the interaction between Enrofloxacin and Penicillin, Enrofloxacin and Norfloxacin, and Penicillin and Norfloxacin. The squares of all antibiotics showed a negative impact except Enrofloxacin and Penicillin, where both showed a positive impact.

Table 7.

Analysis of Variance of Antibiotics treatment against Bubaline mastitis using Response Surface Methodology under Box Behnken Design.

Table 7.

Analysis of Variance of Antibiotics treatment against Bubaline mastitis using Response Surface Methodology under Box Behnken Design.

| Source |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F-value |

p-value |

| Model |

0.3977 |

20 |

0.0199 |

37.69 |

< 0.0001 |

| A-Enrofloxacin + PRP |

0.0089 |

1 |

0.0089 |

16.89 |

0.0005 |

| B-Penicillin + PRP |

0.0567 |

1 |

0.0567 |

107.48 |

< 0.0001 |

| C-Gentamicin +PRP |

0.0275 |

1 |

0.0275 |

52.08 |

< 0.0001 |

| D-Amoxicillin + PRP |

5.580×107

|

1 |

5.580×107

|

0.0011 |

0.0441 |

| E-Norfloxacin + PRP |

0.0089 |

1 |

0.0089 |

16.89 |

0.0005 |

| AB |

0.0086 |

1 |

0.0086 |

16.34 |

0.0006 |

| AC |

0.0038 |

1 |

0.0038 |

7.26 |

0.0139 |

| AD |

0.0044 |

1 |

0.0044 |

8.42 |

0.0088 |

| AE |

0.0086 |

1 |

0.0086 |

16.34 |

0.0006 |

| BC |

0.0038 |

1 |

0.0038 |

7.26 |

0.0139 |

| BD |

0.0044 |

1 |

0.0044 |

8.42 |

0.0088 |

| BE |

0.0086 |

1 |

0.0086 |

16.34 |

0.0006 |

| CD |

0.0000 |

1 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

1.0000 |

| CE |

0.0038 |

1 |

0.0038 |

7.26 |

0.0139 |

| DE |

0.0044 |

1 |

0.0044 |

8.42 |

0.0088 |

| A² |

0.0082 |

1 |

0.0082 |

15.56 |

0.0008 |

| B² |

0.0082 |

1 |

0.0082 |

15.56 |

0.0008 |

| C² |

0.0005 |

1 |

0.0005 |

0.9612 |

0.0386 |

| D² |

0.0003 |

1 |

0.0003 |

0.6368 |

0.0342 |

| E² |

0.0082 |

1 |

0.0082 |

15.56 |

0.0008 |

| Residual |

0.0106 |

20 |

0.0005 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

0.0100 |

15 |

0.0006 |

1.33 |

0.712 |

| Error |

0.0006 |

5 |

0.0004 |

|

|

| Total |

0.4083 |

40 |

|

|

|

According to analysis of variance (

Table 5), the model fitted was found to be significant as the P-value was less than 0.05. All the antibiotics were found to be significant (P<0.05). The interaction of all the antibiotics was also found to be significant, except Amoxicillin and Gentamicin. This reveals that antibiotics treated with PRP have appropriate reactivity against mastitis.

Based on the analysis of variance applied to this model, it became obvious that this model has shown a significant response at 5% level of significance, while this model is also very suitable and reproducible due to having very little lack of fit (P>0.05). Thus, the optimum parameters have also been defined as shown in

Table 5 and Figure 10. The contour and surface plots developed based upon this analysis also depict that antibiotic treatment with PRP can extensively reduce the risk of mastitis in bovines.

According to the values mentioned in

Table 6, it has been concluded that in run 1, 3, 8, 11, 13, 14, 20, 25, 30, 32, 38 and 40 showed maximum inhibition of mastitis.

Table 8.

Observed and Predicted values for Antibiotics treatment against Bubaline mastitis using Response Surface Methodology under Box Behnken Design.

Table 8.

Observed and Predicted values for Antibiotics treatment against Bubaline mastitis using Response Surface Methodology under Box Behnken Design.

| Runs |

Enrofloxacin + PRP (A) |

Penicillin + PRP (B) |

Gentamicin + PRP (C) |

Amoxicillin + PRP (D) |

Norfloxacin + PRP (E) |

Inhibition |

| Observed Value |

Predicted Value |

| 1 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

1.10 |

1.09 |

| 2 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

5.00 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

| 3 |

5.00 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

1.10 |

1.09 |

| 4 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

| 5 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

1.00 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

0.89 |

0.86 |

| 6 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.97 |

0.99 |

| 7 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

0.97 |

0.99 |

| 8 |

5.00 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

1.10 |

1.09 |

| 9 |

3.50 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

0.90 |

0.89 |

| 10 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

4.00 |

2.00 |

0.91 |

0.93 |

| 11 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

5.00 |

1.10 |

1.09 |

| 12 |

3.50 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| 13 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

1.11 |

1.04 |

| 14 |

2.00 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

1.10 |

1.09 |

| 15 |

3.50 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

0.91 |

0.93 |

| 16 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

0.97 |

0.97 |

| 17 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

1.00 |

0.98 |

| 18 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| 19 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

0.91 |

0.93 |

| 20 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

1.14 |

1.16 |

| 21 |

3.50 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

5.00 |

1.10 |

1.09 |

| 22 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

0.87 |

0.87 |

| 23 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| 24 |

5.00 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

0.97 |

0.97 |

| 25 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

5.00 |

1.11 |

1.11 |

| 26 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

1.09 |

1.10 |

| 27 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

1.00 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

0.77 |

0.80 |

| 28 |

3.50 |

2.00 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.87 |

0.87 |

| 29 |

3.50 |

2.00 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.97 |

0.99 |

| 30 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

1.11 |

1.11 |

| 31 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.94 |

0.94 |

| 32 |

5.00 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

1.14 |

1.16 |

| 33 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

4.00 |

5.00 |

1.09 |

1.10 |

| 34 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

0.90 |

0.89 |

| 35 |

5.00 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

4.00 |

3.50 |

1.09 |

1.10 |

| 36 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.87 |

0.87 |

| 37 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

5.00 |

0.97 |

0.97 |

| 38 |

5.00 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

5.00 |

1.11 |

1.11 |

| 39 |

5.00 |

3.50 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

| 40 |

3.50 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

3.00 |

5.00 |

1.14 |

1.16 |

| 41 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.90 |

0.89 |

Figure 6.

Surface plot for Antibiotics treatment against Bubaline mastitis using Response Surface Methodology under Box Behnken Design.

Figure 6.

Surface plot for Antibiotics treatment against Bubaline mastitis using Response Surface Methodology under Box Behnken Design.

4. Discussion

Bubaline mastitis is among the key challenges to the global and local dairy industry. In our study area, most of the buffalo farming was framed into backyard farming that lacked the basic husbandry practices such as hygienic conditions, preventive health measures, and proper nutrition. The buffalo population was more vulnerable to different health disorders. Mastitis, being an infectious disease, is mainly managed with antibiotics that cause different serious animal and human health hazards, such as antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic residues in milk and meat. In this study, the impact of antibiotics alone on mastitis after 15 days was not significant. In contrast to antibiotics, PRP and PRP plus Antibiotics were equally significant in terms of improvement of grades of CMT. No significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of MP% AT day 15.

There are several reasons why PRP can replace antibiotics for the treatment of bubaline mastitis. Antibiotics are limited to antibacterial features without having any regenerative impact on the parenchyma cells of mammary glands, while PRP has been proven its regenerative effects on various organs of humans and animals in various studies [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. On qualitative grounds of this study, there was a remarkable reduction in CMT findings in comparison with the antibiotic group. PRP could be used in order to address burning health issues such as milk antibiotic residues and antimicrobial resistance. PRP preparation for this study is a very inexpensive and has been practically demonstrated to prepare and use in a poor resourced field setting for the management of bubaline mastitis.

The exact explanation regarding the antibacterial role of PRP has not been completely exposed and documented, but the current knowledge base elucidates that platelets may impact the host antimicrobial mechanism in several ways: they discharge oxygen metabolic biochemicals such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, and hydroxyl free radicals [

16,

17]; they have the ability to attach, aggregate, and internalize microbes, which potentiate the rate of clearance of microbes from the blood of the host, and they release a set of powerful protein molecules [

18,

19,

20].

Along with the antibacterial activity of PRP, the underplaying principle, that advocates the use of PRP for regeneration, demonstrates the biological role of various growth factors stored and released by platelets such as PDGF, TGF-β, EGF, VEGF, IGF-1, FGF, HGF and other supplementary biological agents that augment the healing process of soft tissue and orthopedic inflammation [

21,

22,

23]. For further understanding TGF TGF-alpha augments the proliferation of mammary epithelial tissues and morphogenesis of the udder tissues [

24,

25].

The application of PRP in veterinary medicine is an emerging therapy that still needs to be explored further. Previously, it has been employed primarily on equine tendinopathies, porcine intestinal wound healing and canine dermatological pathologies [

26,

27,

28]. It is getting more popular as more clinical aspects are being exposed over time. In bovines, the clinical impact of PRP has been documented in the management of endometritis [

29]. So, there is a huge potential in PRP that could further explore its potential uses as an antibacterial and regenerative agent. Most of the studies of PRP have been documented in the same patient, while little data is available on heterologous PRP [

30,

31,

32]. Heterologous PRP could play a critical role in veterinary medicine, which could be further processed in terms of a delayed mode of action to make it usable even late after harvesting.

In a similar study in 2014, Lange-Consiglio and team reported significant results of PRP in cattle mastitis. They reported the important role of PRP in combating the inflammation process, hindering the process of soft tissue damage, and reducing the repetition of mastitis. Several studies have documented the in vitro antibacterial activity of PRP. Burnouf et al. (2013) [

33] elucidated a significant role of PRP against

E. coli,

P. aeruginosa,

K. pneumoniae, and

S. aureus. Anitua et al. (2012) reported significant antibacterial activity of PRP against different strains of

Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis, except methicillin-sensitive S. epidermidis [

34]. But a year later, Drago and coworkers stated that PRP was very effective against

Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus agalactiae,

Candida albicans, and

Streptococcus oralis, while it could not exhibit any activity against

Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains [

18]. In the current study, we could not observe a well-defined antibacterial activity against the culture of milk samples. Though there was a gross difference in the culture treated with placebo and PRP. There was comparatively reduced microbial growth observed in PRP PRP-treated culture.

Ullah et al. (2023) [

35] described that there are certain probiotic bacteria when administered combined with PRP, are found to be more prolific against mastitis, causing a significant reduction in somatic cell count and retards the growth of mastitis-causing bacteria.

Bao et al. (2023) [

36] demonstrated that Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) is one of the major causes for the development of mastitis and reduction in milk production. This disorder can be effectively managed with the application of hexadecanamide, which disrupts the

S. aureus-induced activation of the NF-κB pathway, ultimately leading to attenuation of mastitis in bovines.

Wang et al. (2023) [

37] confirmed that extracellular vesicles can effectively reduce mastitis and have essential functions, as a total of 1253 exosome proteins were isolated from further quantified milk samples. Differently enriched proteins were found to be more active against clinical mastitis as they activate the defense response to Gram-positive bacteria by producing the granulocyte system, innate immune response, neutrophil degranulation, and antimicrobial peptides.

Kumar et al. (2024) [

38] found 76 protease enzymes from the urine of cows infected with bovine mastitis, and proteases were responsible for the inhibition of potential microbes, i.e.,

S. aureus,

E. coli, and

S. agalactiae due to the production of potential antimicrobial peptides.

This study was a random study that was performed in a field setting with minimal clinical and diagnostic resources. Among the other objectives of this study, it was also a major goal to implement the idea of PRP in poor-resourced settings. In this study, the effect of PRP against any pathogenic isolation from a mastitis milk sample was not evaluated. The study was conducted in a small number of animals in each group. This study could be continued for the exploration of further parameters of mastitis under the treatment of PRP in bubaline mastitis, but limited resources could not allow the team to proceed with it further.