Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

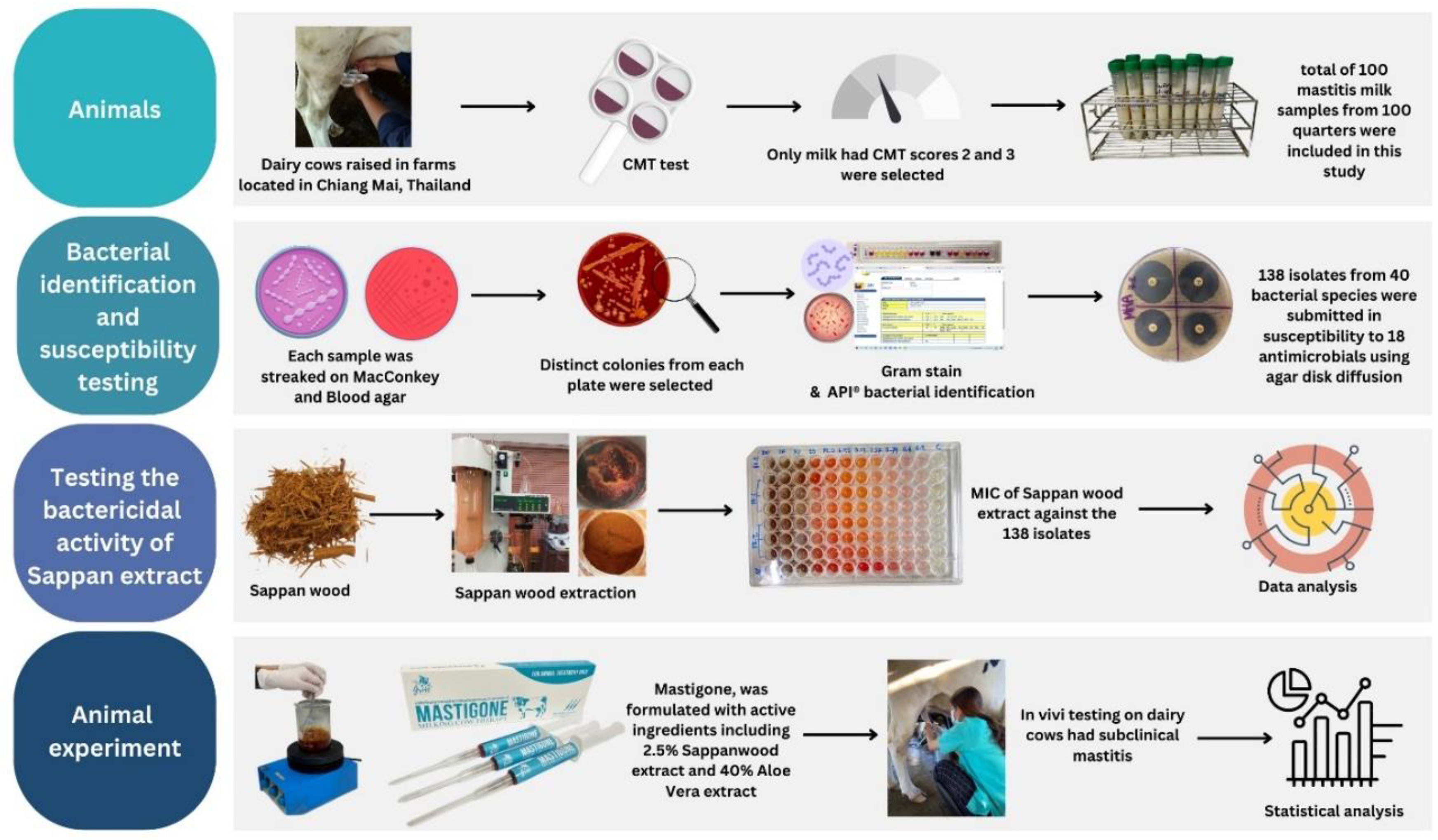

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Microbial Identification and Susceptibility Testing

2.3. Testing the Bactericidal Activity of Herbal Preparations

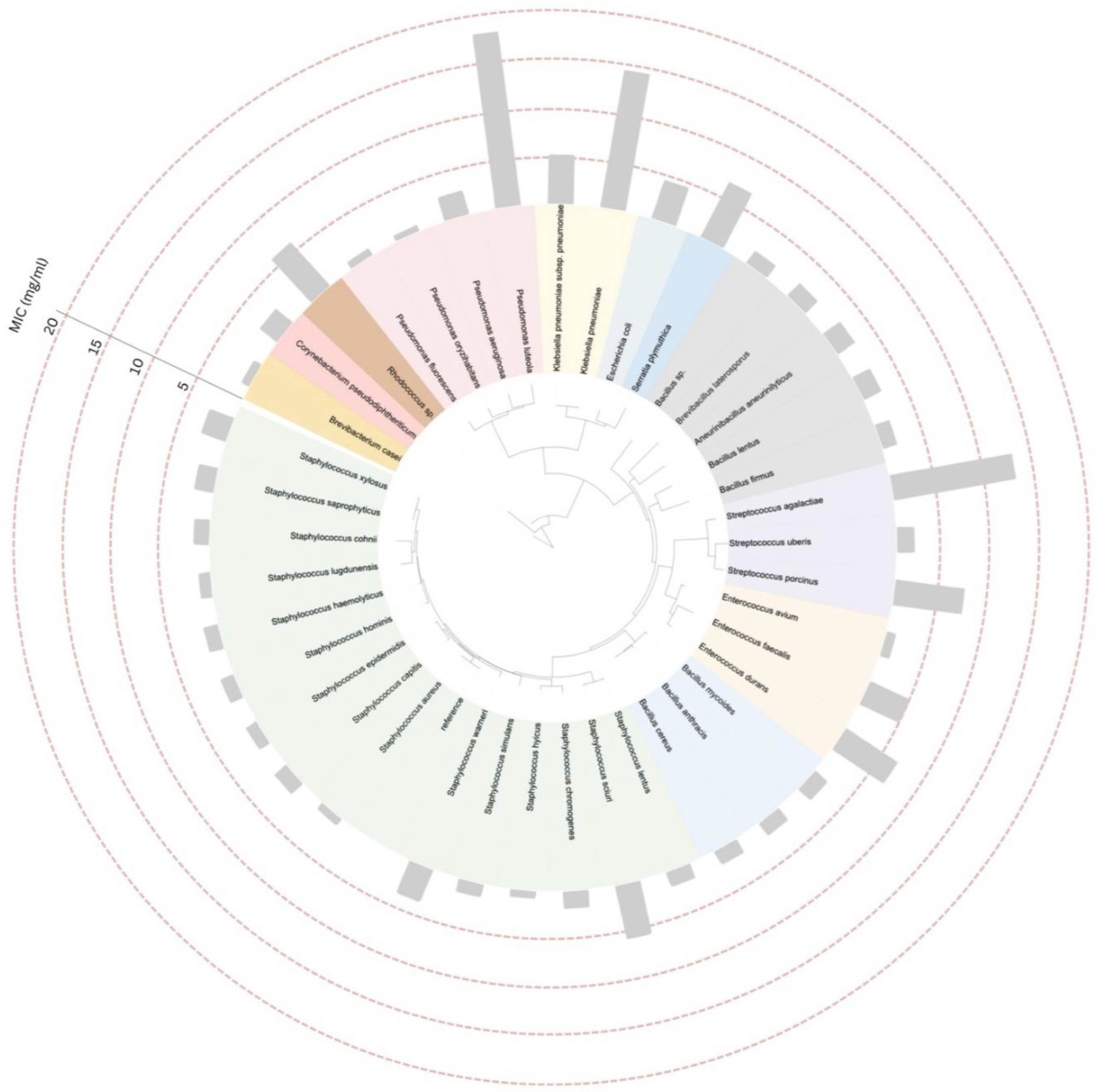

2.4. Construction of the Phylogenetic Tree and Data Annotation

2.5. Animal Experiment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

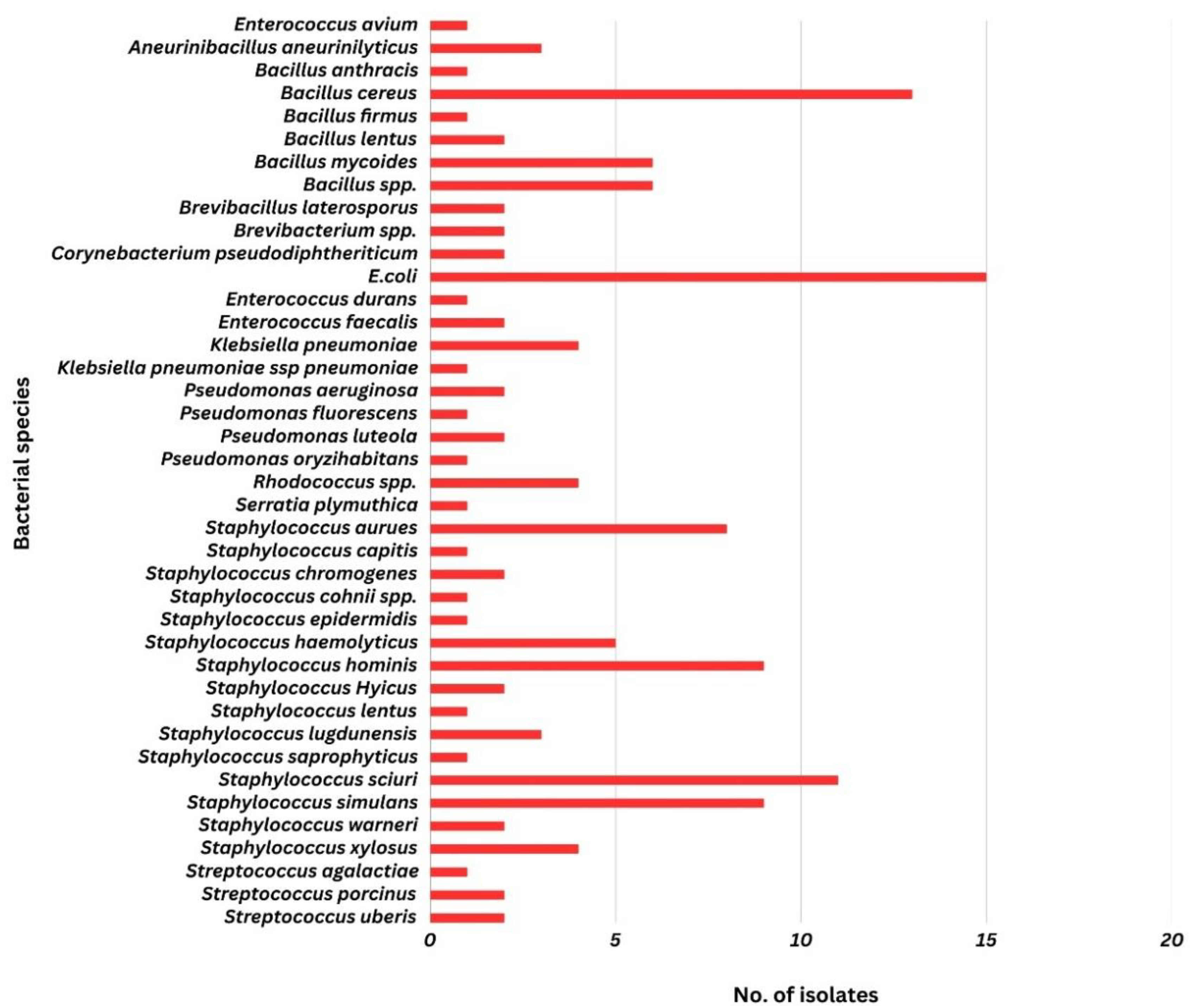

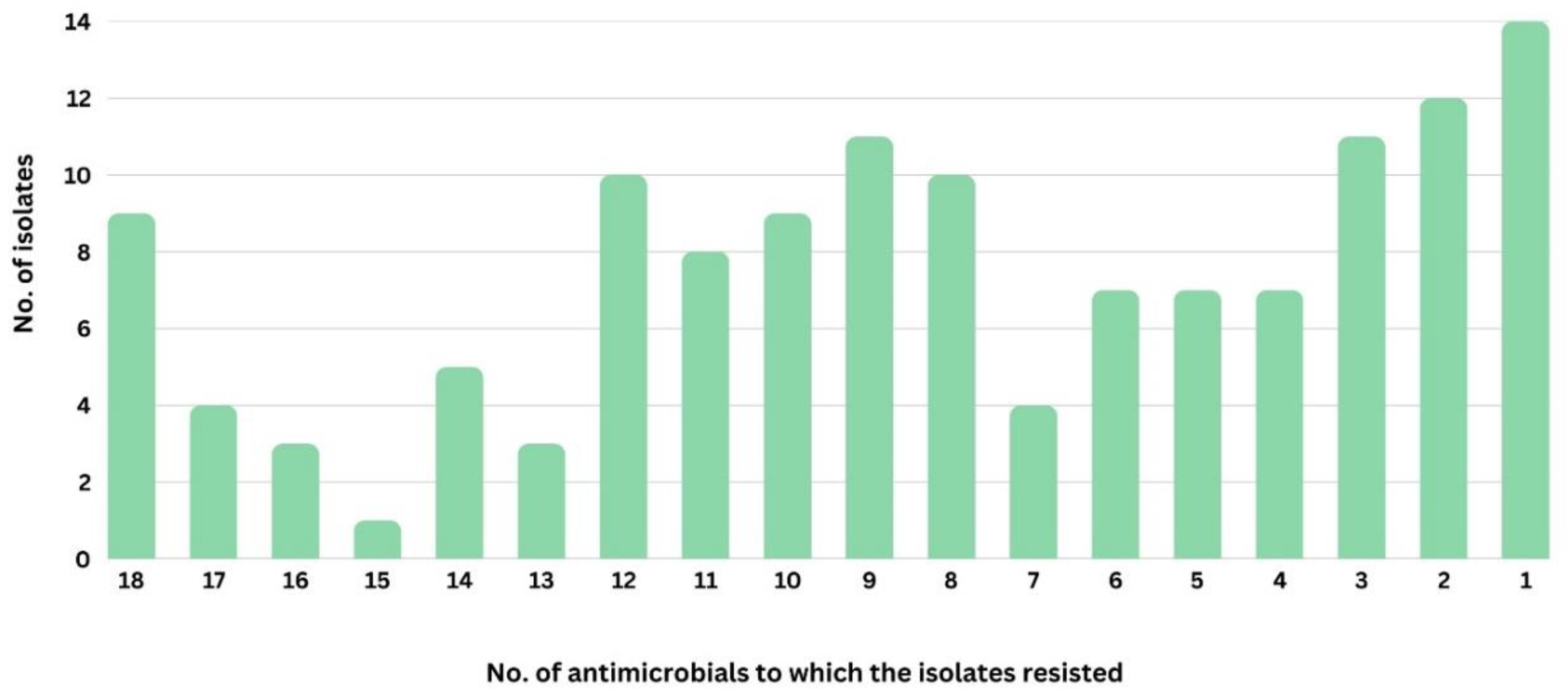

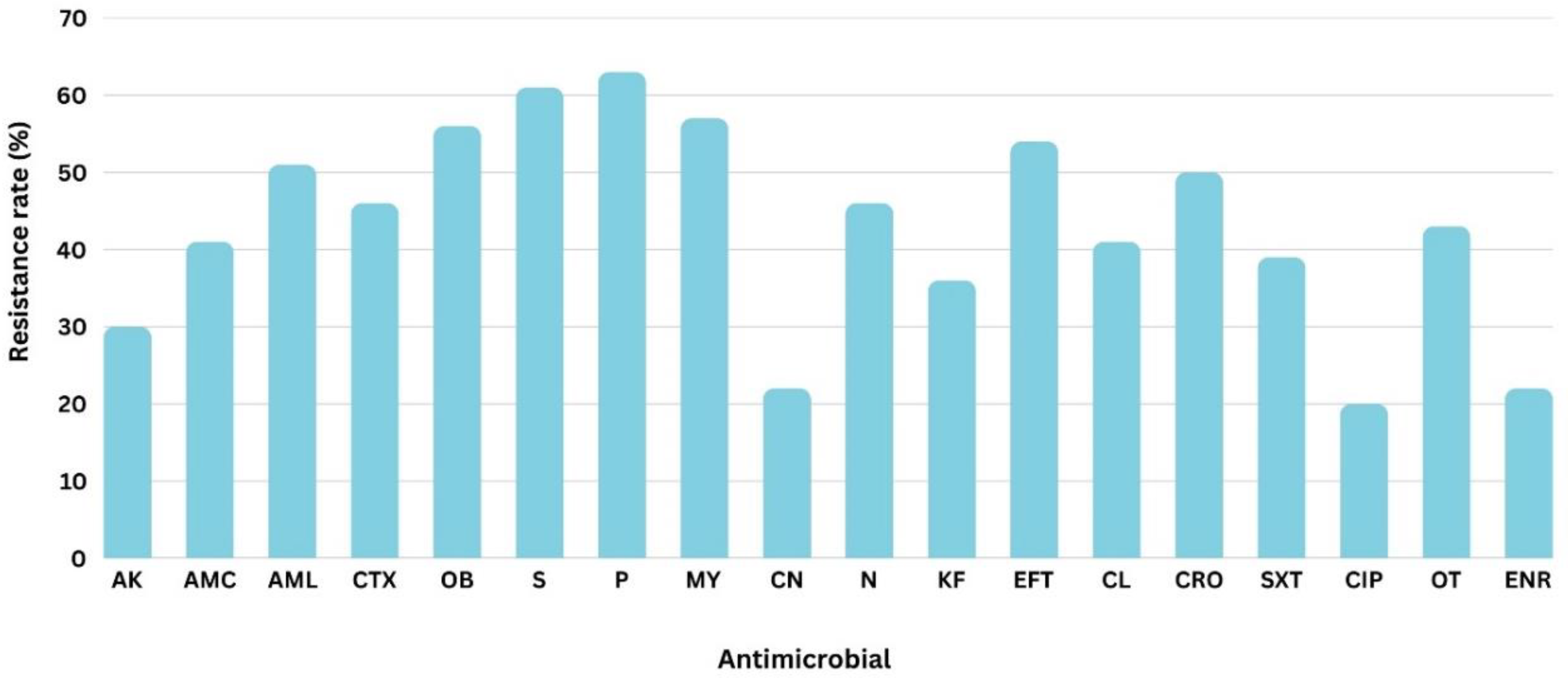

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Materials

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Kossaibati, M.; Esslemont, R. The costs of production diseases in dairy herds in England. The Vet. J. 1997, 154, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, A. J. Bovine mastitis: an evolving disease. Vet. J. 2002, 164, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pașca, C.; Mărghitaș, L. A.; Dezmirean, D. S.; Matei, I. A.; Bonta, V.; Pașca, I.; Chirilă, F.; Cîmpean, A.; Fiț, N. I. Efficacy of natural formulations in bovine mastitis pathology: alternative solution to antibiotic treatment. J. Vet. Res. 2020, 64, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufour, S.; Labrie, J.; Jacques, M. The mastitis pathogens culture collection. Microbiol. Res. Announc. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S. P.; Murinda, S. E. Antimicrobial resistance of mastitis pathogens. Vet. Clin. Food. Anim. Pract. 2012, 28, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, B.; Miko, A.; Pries, K.; Hildebrandt, G.; Kleer, J.; Schroeter, A.; Helmuth, R. Class 1 integrons and resistance gene cassettes among multidrug resistant Salmonella serovars isolated from slaughter animals and foods of animal origin in Ethiopia. Acta. tropica. 2007, 103, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W. N.; Han, S. G. Bovine mastitis: Risk factors, therapeutic strategies, and alternative treatments—A review. Asian-Australas J. Anim.Sci. 2020, 33, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimestri, A. Microbiological and physicochemical quality of pasteurized milk supplemented with sappan wood extract (Caesalpinia sappan L.). Int Food Res J. 2018, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Teplicki, E.; Ma, Q.; Castillo, D. E.; Zarei, M.; Hustad, A. P.; Chen, J.; Li, J. The Effects of Aloe vera on Wound Healing in Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Viability. Wound 2018, 30, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Philpot, W. N.; Nickerson, S. C. Mastitis: counter attack. Babson Bros. Co., 1992. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Calibration of zone diameter breakpoints against MIC 2021. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/ast_of_bacteria/calibration_and_validation/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Golus, J.; Sawicki, R.; Widelski, J.; Ginalska, G. The agar microdilution method–a new method for antimicrobial susceptibility testing for essential oils and plant extracts. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical & Laboratiry Standards Institute: CLSI Guidelines. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; Wayne, 2015.

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiumlamai, S. Dairy management, health and production in Thailand. Int. Dairy. Top. 2009, 8, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, J.; Kamphuis, C.; Martins, C.; Barreiro, J.; Tomazi, T.; Gameiro, A. H.; Hogeveen, H.; Dos Santos, M. Bovine subclinical mastitis reduces milk yield and economic return. Livest Sci. 2018, 210, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasomsri, P. Effect of lameness on daily milk yield in dairy cow. Thai J. Vet. Med. 2022, 52, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingwell, R. T.; Leslie, K. E.; Schukken, Y. H.; Sargeant, J. M.; Timms, L. L. Evaluation of the California mastitis test to detect an intramammary infection with a major pathogen in early lactation dairy cows. Can Vet J. 2003, 44, 413. [Google Scholar]

- Kala, S. R.; Rani, N. L.; Rao, V. V.; Subramanyam, K. V. Comparison of different diagnostic tests for the detection of subclinical mastitis in buffaloes. Buffalo. Bull. 2021, 40, 653–659. [Google Scholar]

- Ramuada, M.; Tyasi, T. L.; Gumede, L.; Chitura, T. A practical guide to diagnosing bovine mastitis: a review. Front. Anim. Sci. 2024, 5, 1504873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifatbegović, M.; Nicholas, R. A.; Mutevelić, T.; Hadžiomerović, M.; Maksimović, Z. Pathogens Associated with Bovine Mastitis: The Experience of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Vet Sci. 2024, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, R.; Hatiya, H.; Abera, M.; Megersa, B.; Asmare, K. Bovine mastitis: prevalence, risk factors and isolation of Staphylococcus aureus in dairy herds at Hawassa milk shed, South Ethiopia. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayarao, B. M.; Wolfgang, D. R. Bulk-tank milk analysis: A useful tool for improving milk quality and herd udder health. Vet. Clin. Food. Anim. Pract. 2003, 19, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigo, F.; Vasil', M.; Ondrašovičová, S.; Výrostková, J.; Bujok, J.; Pecka-Kielb, E. Maintaining optimal mammary gland health and prevention of mastitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 607311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saed, H. A. E.-M. R.; Ibrahim, H. M. M. Antimicrobial profile of multidrug-resistant Streptococcus spp. isolated from dairy cows with clinical mastitis. J. Adv. Ve.t Anim. Res. 2020, 7, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaas, I.; Zadoks, R. An update on environmental mastitis: Challenging perceptions. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, F. J.; Collignon, P.; Powers, J. H.; Chiller, T. M.; Aidara-Kane, A.; Aarestrup, F. M. World Health Organization ranking of antimicrobials according to their importance in human medicine: a critical step for developing risk management strategies for the use of antimicrobials in food production animals. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V.; de Jong, A.; Moyaert, H.; Simjee, S.; El Garch, F.; Morrissey, I.; Marion, H.; Vallé, M. Antimicrobial susceptibility monitoring of mastitis pathogens isolated from acute cases of clinical mastitis in dairy cows across Europe: VetPath results. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2015, 46, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timonen, A.; Sammul, M.; Taponen, S.; Kaart, T.; Mõtus, K.; Kalmus, P. Antimicrobial selection for the treatment of clinical mastitis and the efficacy of penicillin treatment protocols in large Estonian dairy herds. Antibiotics 2021, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Qu, W.; Barkema, H. W.; Nobrega, D. B.; Gao, J.; Liu, G.; De Buck, J.; Kastelic, J. P.; Sun, H.; Han, B. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of 5 common bovine mastitis pathogens in large Chinese dairy herds. J. dairy. sci. 2019, 102, 2416–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarestrup, F. M. The livestock reservoir for antimicrobial resistance: a personal view on changing patterns of risks, effects of interventions and the way forward. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argudín, M. A.; Deplano, A.; Meghraoui, A.; Dodémont, M.; Heinrichs, A.; Denis, O.; Nonhoff, C.; Roisin, S. Bacteria from animals as a pool of antimicrobial resistance genes. Antibiotics 2017, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Karthik, S.; Mathivanan, K.; Baskaran, R.; Karthikeyan, M.; Gopi, M.; Govindasamy, C. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Caesalpinia sappan L. Asian. Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S136–S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmal, N. P.; Panichayupakaranant, P. Antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory activities of standardized brazilin-rich Caesalpinia sappan extract. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 1339–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattananandecha, T.; Apichai, S.; Julsrigival, J.; Ogata, F.; Kawasaki, N.; Saenjum, C. Antibacterial activity against foodborne pathogens and inhibitory effect on anti-inflammatory mediators’ production of Brazilin-enriched extract from Caesalpinia sappan Linn. Plants 2022, 11, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.; Baquero, F. Mutation frequencies and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2000, 44, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normark, B. H.; Normark, S. Evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance. J. Intern. Med. 2002, 252, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Dutta, A.; Das, M.; Sarkar, K.; Mandal, C.; Chatterjee, M. Effect of Aloe vera on nitric oxide production by macrophages during inflammation. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005, 37, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

| Milk Quality | Reaction | Characteristics of Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Normal, Very Good | 0 | Homogeneous mixture, moves quickly, pale purple color |

| Normal, Good | T | Mixture becomes mucous like, forms a thread and then disappears, moves quickly, pale purple color |

| Normal, Fair | 1 | Mixture is viscous and mucous like, remains slightly, moves slower, and the purple color intensifies |

| Subclinical mastitis | 2 | Mixture is viscous and mucous like, remains significant, moves very slowly, and the purple color intensifies, visually appears normal |

| Clinical mastitis | 3 | Mixture is thick and mucous-like, easily observable |

| Parameters | Before | After | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total bacterial count (log10CFU/ml) | 6.875±1.722 | 2.704±2.91 | <0.01 |

| CMT score | 3±0 | 1±0 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).