1. Introduction

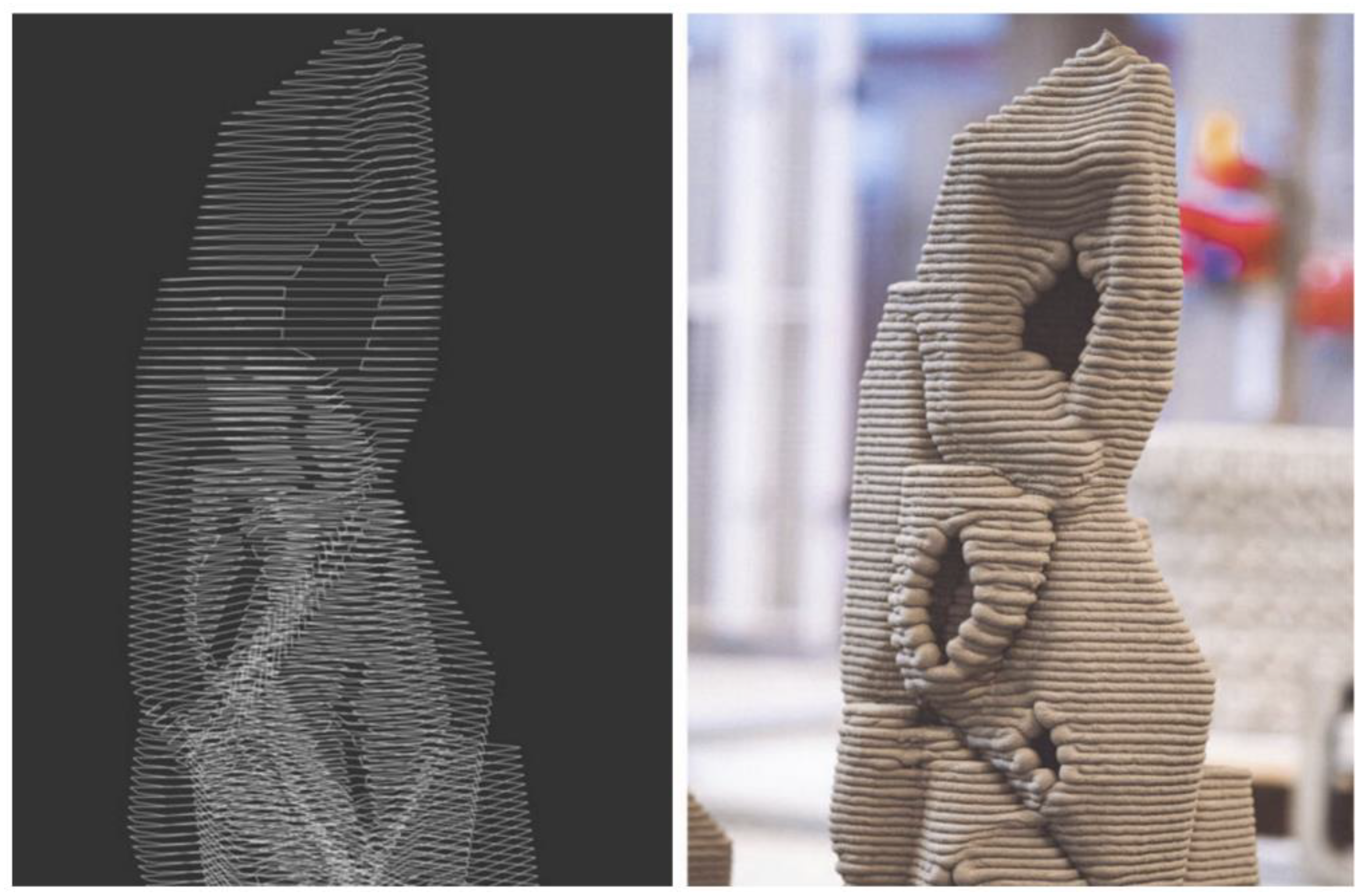

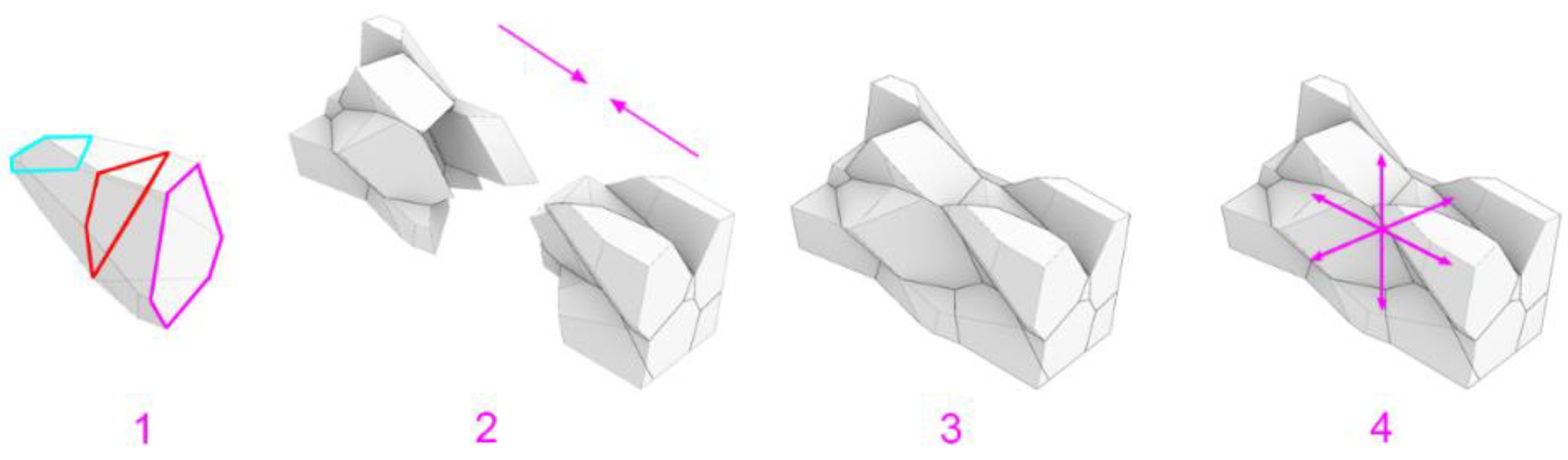

Robotic assembly is in the context of extraterrestrial construction a necessity with autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) showing significant potential for construction tasks (Ardiny et al., 2015). They are designed to operate independently, navigate through complex environments, and execute various construction activities with minimal human intervention. A conceptual construction process for a Martian habitat built by an AMRs is being developed at Technical University (TU) Delft as part of a European Space Agency (ESA) and industry co-funded project, Rhizome (Bier et al., 2021). The primary aim is to address the challenges of autonomous robotic assembly for constructing sustainable habitats on Mars. This paper presents the developed method for the robotic assembly of prefabricated non-uniform 3D-printed components

1 (

Figure 1). The habitat is constructed from regolith-based concrete components to shield astronauts from radiation and provide thermal insulation. The approach relies on the use of AMRs to survey areas and extract regolith, for the production of concrete components using in-situ resource utilization (ISRU).

The developed approach aligns with recent advancements in extraterrestrial construction involving 3D printing with local materials and autonomous robots performing various construction tasks as demonstrated in various projects developed within ESA’s Off-Earth Manufacturing and Construction Campaign (Wilkinson et al., 2017; Cervone et al., 2024). In the presented study, three main challenges are considered: Firstly, the development of the Voronoi-based 3D-printed components: Due to the irregular shape characteristics, it is necessary to have a robust classification system to allocate robot assembly tasks efficiently. Secondly, even though the gravity on Mars is only about 38% of the gravity on Earth

2, the structural stability of the stacked 3D-printed components needs to be ensured at all times. Lastly, the assembly tasks must consider the physical constraints of the mobile robots. The presented research addresses these challenges by utilizing K-means clustering for classification and topological interlocking.

While K-means clustering of components relies on grouping data points into clusters based on similarities (Feist et al., 2022), topological interlocking ensures stability of load-bearing structures based on Voronoi. By arranging structural elements in a way that they interlock with each other, the structure withstands external forces without the need for additional reinforcement. The study introduces clustering and interlocking mechanisms tailored for robotic assembly, aiming at improving construction efficiency and structural integrity of Martian habitats. While the approach is developed for extraterrestrial applications, it can be transferred to a terrestrial context.

2. State-of-the-Art

Recent advancements in robotic construction emphasize the growing role of AI and automation in architecture and building construction. For instance, autonomous robots for constructing off-Earth structures are explored in academia and to some degree in practice (Cervone et al., 2024) using modular i.e., componential prefabrication approaches that allow the assembly of structures using robots (Aslaminezhad et al., 2024). Ikotun et al. (2023) and Koronaki et al. (2023) provide insights into the application of K-means clustering for optimizing modular construction systems, while Estrin et al. (2022) extend the scope of topological interlocking, demonstrating its potential in architecture. These approaches of clustering and topological interlocking are adapted in the presented case study to address challenges of assembling unique prefabricated Voronoi-based components while tracking the progress and allocation of tasks during the process.

2.1. Clustering

Clustering components for the robotic assembly involves a process of grouping related components to streamline the assembly process. Clustering is an Artificial Intelligence (AI) technique for grouping similar data points into distinct clusters based on certain features or characteristics. It is widely used due to its simplicity and efficiency in handling large datasets (İşeri & Dino, 2022). Clustering in architectural construction is based on component type, size, shape, function, and/ or assembly sequence (Han et al., 2021).

The K-means clustering is partitioning a dataset into distinct K clusters whereas K refers to the number of clusters that are created by the clustering algorithm. In K-means clustering, the value of K is predetermined by the user and represents the desired number of clusters into which the dataset should be partitioned. There are several advantages of such classification: (a) it is computationally efficient and easy to implement, making it suitable for large datasets and real-time applications; (b) it is relatively insensitive to irrelevant features; (c) the resulting clusters are easy to interpret (Ikotun et al., 2023). Clustering is a versatile and powerful technique with diverse applications across various domains including building construction: Koronaki et al. (2023) developed a method that utilizes the K-means algorithm to cluster space-frame joints into fabrication batches providing an estimation of construction complexity.

2.2. Topological Interlocking

Interlocking of components has a long history in architecture. Traditional Inca architecture featured complex and tightly fitted stone masonry (Fletcher, 1999). More recently, Gramazio and Kohler and their team constructed a self-standing wall by stacking interlocking bricks

3, which achieved stability through friction (Bonwetsch et al., 2007). Current bio-inspired research has contributed to new interlocking methods. For instance, Subramanian et al. (2019) developed a geometric weaving method for Delaunay Lofts

4 based on the relationship between Voronoi points and surfaces. Moreover, Teng et al. (2020) studied the Scutoid

5 cells masonry system to fabricate an interlocking model for the construction of shell structures. These approaches enable systematic exploration of topologically interlocking shapes with varying degrees of interlocking.

3. Contribution

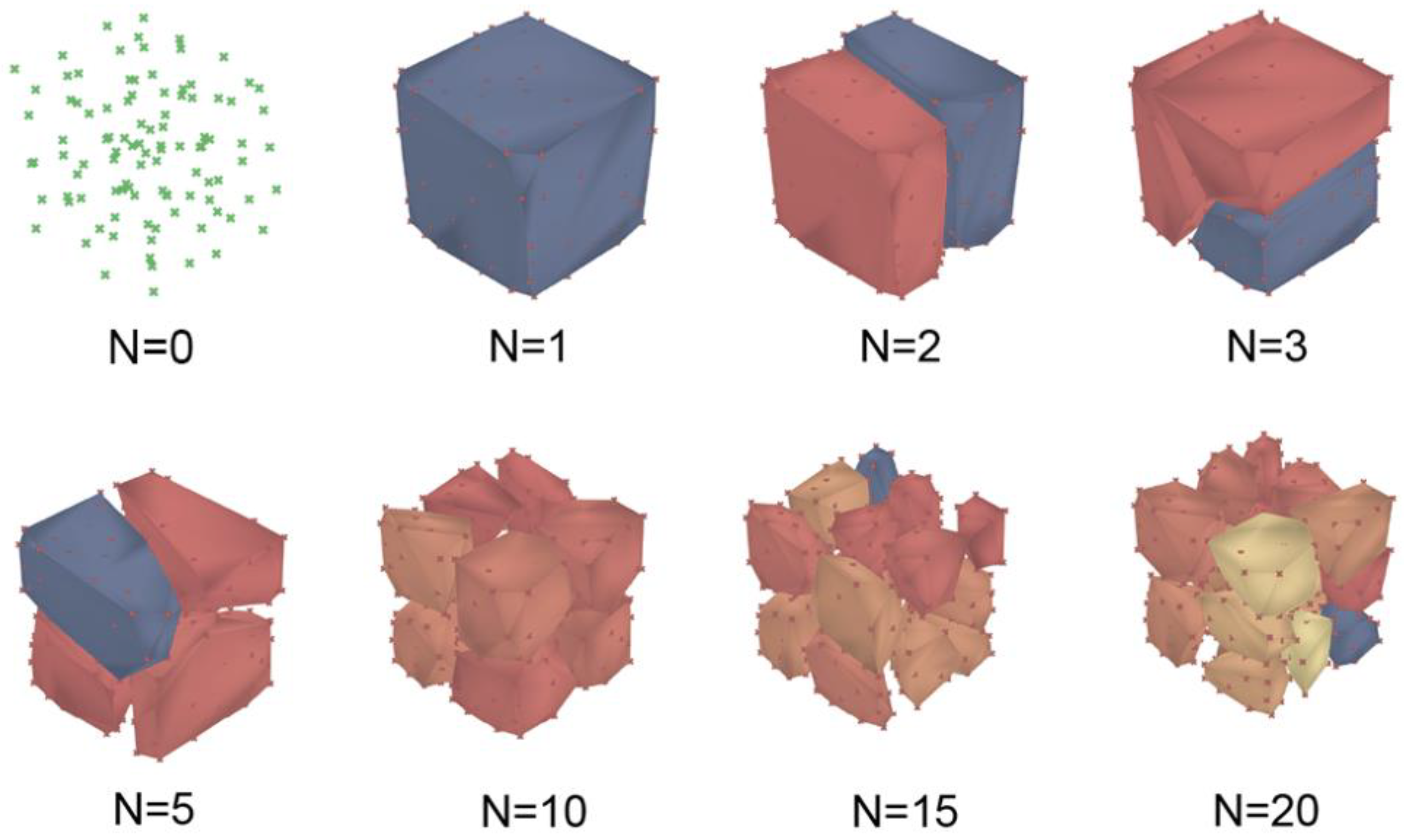

While K-means clustering and topological interlocking are not new their combined use for robotic assembly as presented in this paper contributes to the advancement of AI- and robotics-supported automation of construction processes (

Figure 2).

3.1. Methodology

The presented approach facilitates the development of an underground Martian habitat. It advances research into materially, structurally, and environmentally optimized 3D printed components produced and assembled using Robot-Robot and Human-Robot Interaction (R/HRI) supported Design-to-Robotic-Production and -Assembly (D2RP&A). The habitat is constructed with a swarm of robots (Bier et al., 2022) used to 3D print Voronoi-based building components that are R/ HRI-supported assembled (

Figure 3) while relying on clustering and topological interlocking.

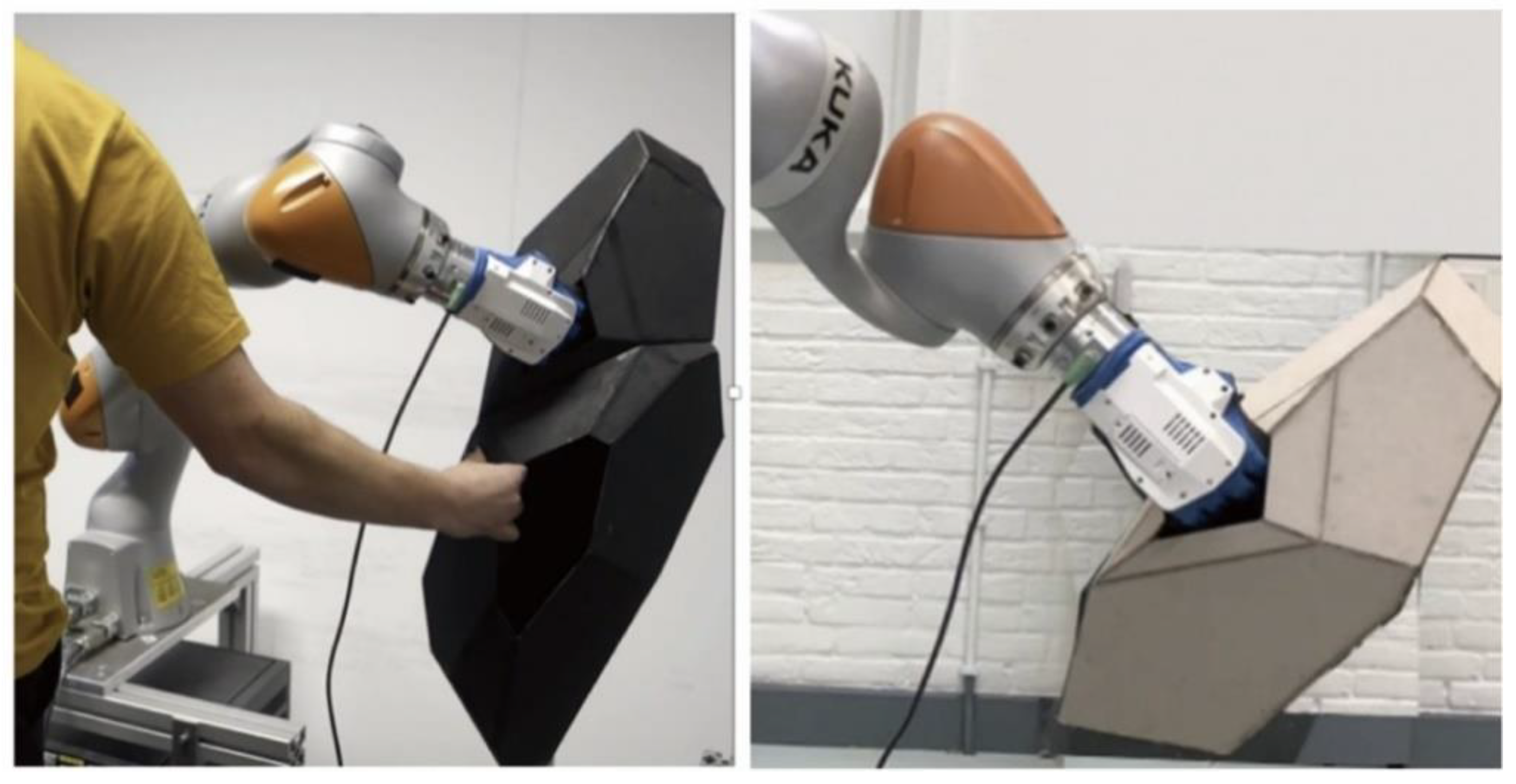

3.1.1. HRI-Supported Assembly

The Voronoi-based building components with similar though unique shapes are robotically picked up from the printing site and placed where the habitat envelope is being constructed. Each component is positioned precisely at its intended location. To accomplish this, the HRI-supported process relying on Computer Vision (CV) ensures the correct recognition and placement of the components, while collaborative robots safely assist humans by managing heavy loads and allowing humans to focus on the cognitively demanding aspects of the task.

3.1.2. K-Means Clustering of Voronoi Cells

K-means clustering of Voronoi cells involves grouping them into clusters based on their spatial characteristics, such as size, shape, and proximity to each other. The purpose of the K-means in this case study is to cluster the individual Voronoi cells and ensure that the clusters meet the requirements for assembly by preventing components from consisting of too few or too many cells.

The Voronoi-based logic is chosen for its advantages concerning functional and structural optimization, design customization, materialization, etc. (Rokicki et al., 2016). The optimized building envelope is subdivided into Voronoi cells. Multiple individual Voronoi cells are then clustered together to form larger components that are 3D-printed. For the assembly process, these vertically printed grouped cells are rotated 90 degrees and assembled horizontally (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The challenge is to cluster the cells into horizontal groups automatically while ensuring suitability for assembly. The developed algorithm dynamically adjusts to the spatial distribution of components and robotic agents, ensuring higher efficiency and accuracy.

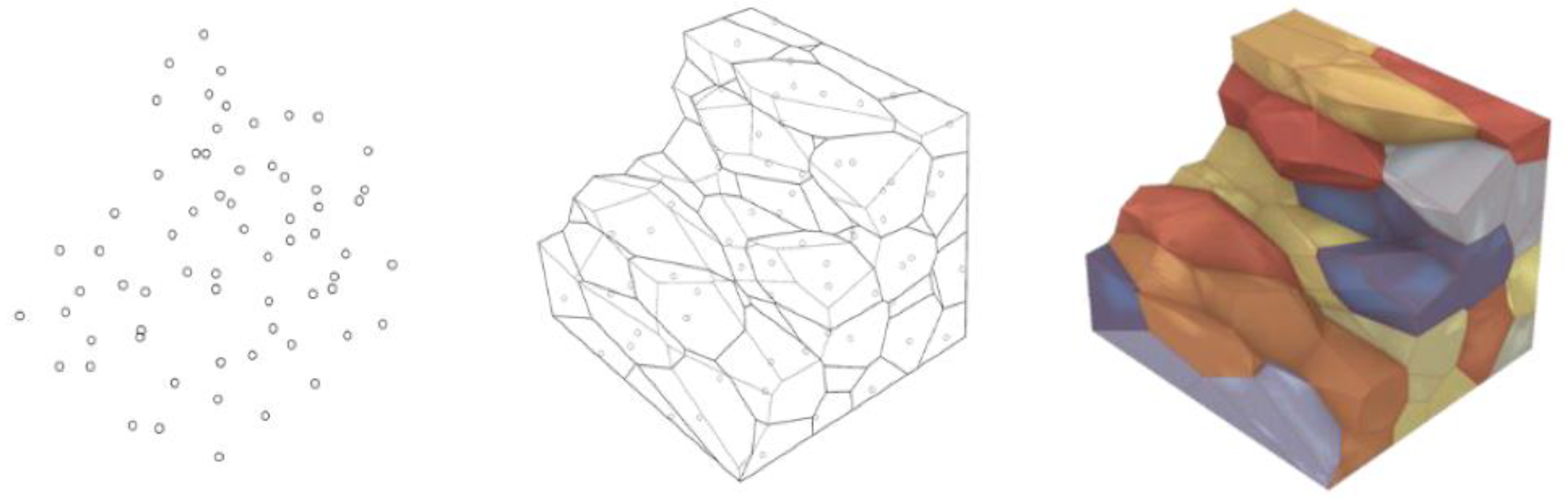

The inputs for the K-means algorithm are the center points of the cells since the Voronoi cells are defined by their center points. The K-means algorithm has settings for indicating the number of clusters and direction of clustering. The number of components is based on the desired 3 points per cluster average, while the direction-based settings for the clustering are derived from the construction requirements (

Figure 2).

The K-means clustering method not only provides better control over the number of clusters but also complements the geometric interlocking. Each boundary representation shell provides a set of numbers, which allows for identifying the sequence logic for the robotic assembly.

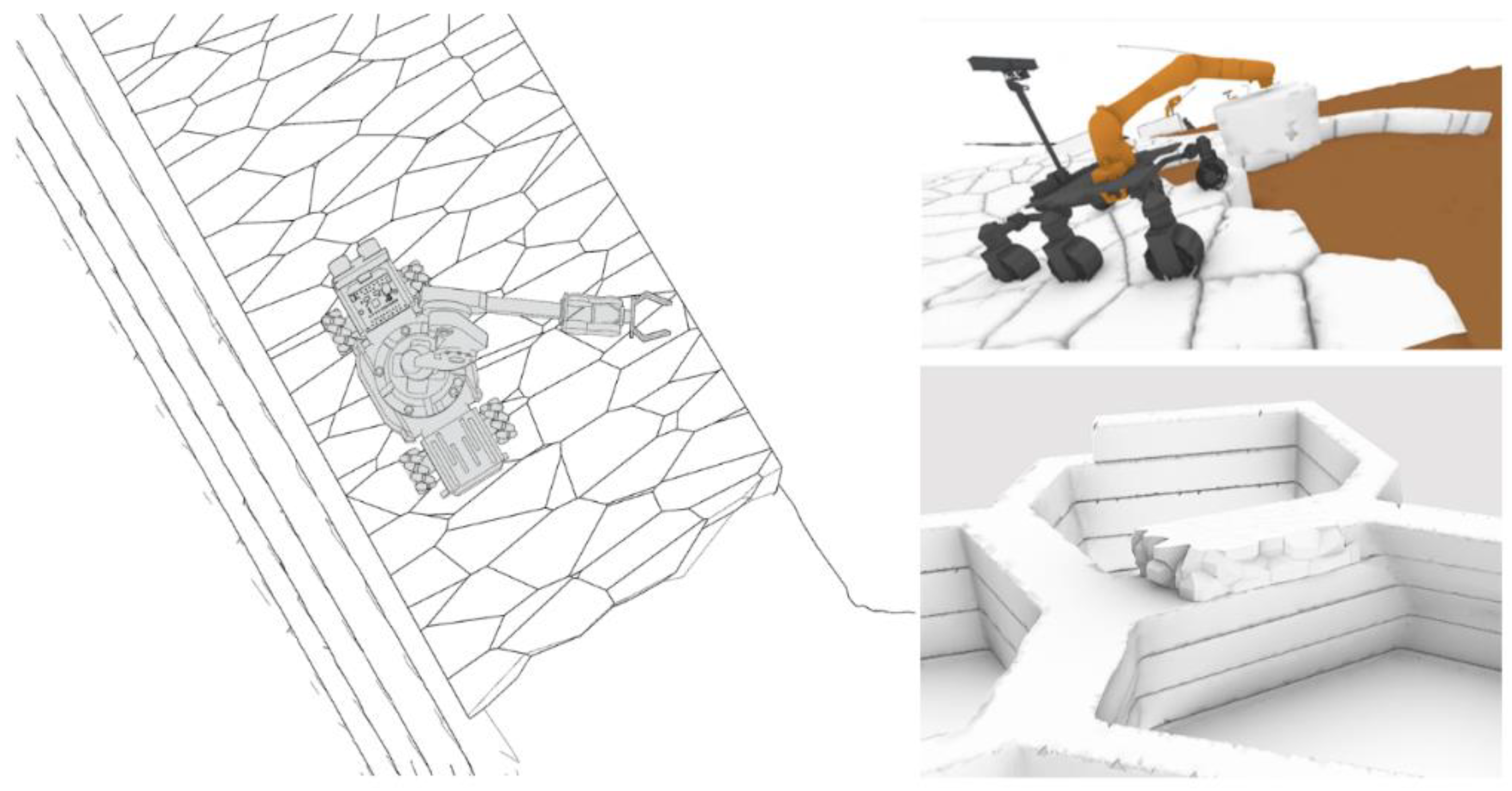

3.1.3. Topological Interlocking of Voronoi-Based Components

The topological interlocking of Voronoi-based components takes into account the robotic gripping area and the depth of the robot arm, allowing the gripper to pick and place the component. It relies on object recognition to detect grabbing vectors based on the geometry. The mock-up component prototype (

Figure 4) is milled from Expanded Polystyrene (EPS).

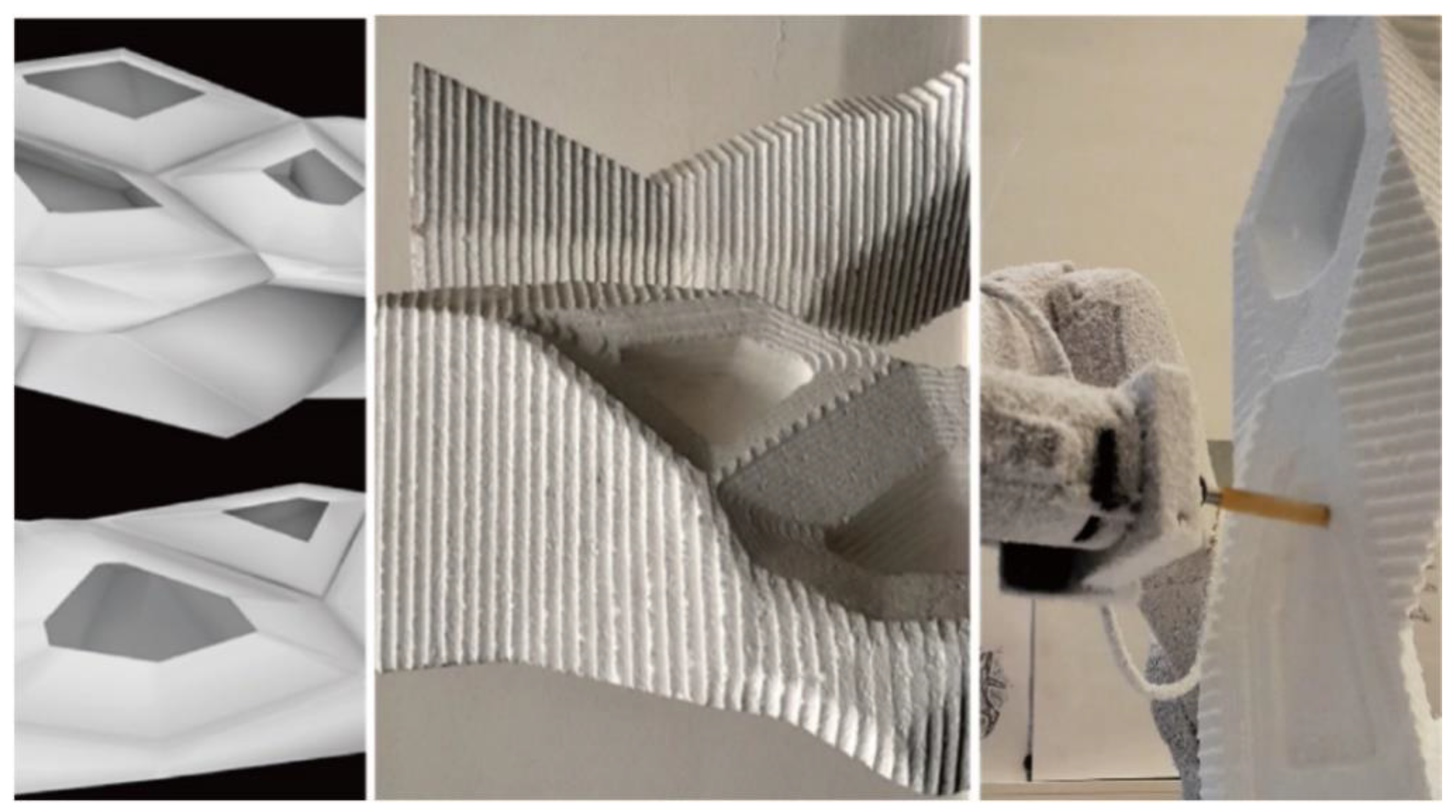

The Voronoi components are layered horizontally during construction. In horizontal loading scenarios, the load weight of the stacking of the components is lower than in vertical loading (Jannasch, 2016). Furthermore, the interlocking design takes the features of the Scutoid into account (

Figure 5) implying that either two vertices on the basal or apical surfaces merge into the center vertex on the intermediate layer (Subramanian et al., 2019). The topological interlocking presented in this study outperforms conventional fastening techniques by eliminating the need for additional connectors. This geometric configuration allows components to be packed tightly, thus forming the required inner interlocking. The density of points relative to the spatial extent of the domain has an impact on the interlocking. Topological interlocking with lower densities produces larger and sparser cells with deeper interlocking regions. The interfacing zone between two elements constrains movement in one direction. The irregular arrangement of cells distributes loads more evenly, reducing stress concentrations and improving resilience against external forces (

Figure 5).

4. Result

The presented generation of Voronoi-based components from a point cloud and the clustering configuration demonstrates the feasibility of this approach for creating structurally stable, interlocking elements for constructing larger structures. The scattered point cloud that represents the spatial distribution of centroids (

Figure 6 left) is transformed into Voronoi cells using computational algorithms ensuring that each cell adheres to geometric and structural requirements. The clustering process further groups these cells into stackable units, enabling efficient production planning and robotic assembly (

Figure 6 middle and right).

The horizontally stacked and interlocked components (

Figure 6 right) highlight the potential of this methodology to create modular, scalable, and structurally robust building blocks, essential for constructing larger structures. These results validate the applicability of Voronoi-based interlocking for space-constrained, resource-limited, and high-stress construction scenarios.

The clustering algorithm optimizes component organization, while interlocking ensures stability, addressing key challenges in extraterrestrial environments such as reduced gravity and resource availability. The methodology also demonstrates adaptability to dynamic construction requirements, paving the way for scalable applications relevant to both extraterrestrial and terrestrial environments.

5. Discussion

The integration of K-means clustering and topological interlocking provides a framework for robotic assembly. Compared to traditional methods, such as adhesive-based assembly or mechanical fasteners, the proposed approach offers superior load distribution, reduced material requirements, and enhanced structural resilience. The methodology also demonstrates adaptability to dynamic construction requirements, paving the way for scalable applications.

Compared to traditional methods, such as adhesive-based assembly or mechanical fasteners, the proposed approach offers superior load distribution, reduced material requirements, and enhanced structural resilience. The clustering method outperforms static grouping techniques by dynamically adapting to spatial distributions, improving efficiency and precision in robotic operations.

While promising, this approach faces several challenges. For the on-site robotic assembly, physical constraints have to be considered (inter al. Cheng, 2021; Bier et al., 2024). Firstly, the maximum reachability of robots affects the maximum size of the components as well as influences the stacking sequence while avoiding collisions with objects, humans, or robot joints. Secondly, the weight of the components needs to be considered. Calculating effective and maximum effective payload will prevent the rover from overturning. Finally, the building is divided into horizontal layers with the mobile robots stacking one layer at a time. The bottom and top of each layer create flat surfaces on which the rover drives (

Figure 7).

6. Conclusions

The presented approach integrates clustering and interlocking into the robotic assembly approach of the Voronoi-based envelope developed for a Martian habitat. The clustering algorithm takes as input Voronoi centroid points to combine Voronoi cells into clusters. These clusters contain the interlocking geometry that is ensures the structural stability of the envelope. This study demonstrates that clustering algorithms, combined with interlocking mechanisms, address critical challenges related to robotic assembly, such as component stacking while ensuring structural stability at all times. The findings highlight the practical feasibility of this method for extra-/ terrestrial applications, paving the way for the autonomous construction of habitats.

The current method focuses predominantly on the envelope of the habitat, with limited consideration of internal structures such as ramps, stairs, and ceilings. Furthermore, the physical strength and scalability of the topological interlocked components require further investigation, in relationship to building size, accessibility/ mobility of robots, etc.

Future research will address these limitations by exploring the strength and durability of topological interlocking components at larger scales and extending the approach to include walls and ceilings. Additionally, work will focus on refining the process to encompass the entire prefabrication-to-assembly pipeline, incorporating advanced robotic algorithms that account for physical constraints such as payload limits and reachability. Furthermore, knowing that regolith-based concrete is prone to cracking further research into the maintenance of the structure is required. By addressing these challenges, the proposed method has the potential to revolutionize autonomous construction in extra-/ terrestrial environments.

The presented approach promotes scaffold-free construction. It minimizes the use of temporary structures during building processes and relies on advanced technologies and design techniques to ensure structural integrity during assembly. It leverages technologies such as robotics, AI, and advanced manufacturing to streamline and optimize building processes, reducing the need for manual labor while increasing efficiency, precision, and sustainability. It exploits synergy effects by transferring advanced technologies from terrestrial to extraterrestrial applications and vice versa.

Funding

This paper has profited from the contribution of MSc and PhD students involved in the presented project co-funded by ESA, Vertico, NSTC, and various industry partners.

References

- Ardiny, H., Witwicki, S., & Mondada, F. (2015). Construction automation mobile robots: A review. 2015 3rd RSI International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICROM), Tehran, Iran (pp. 418-424). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7367821.

- Aslaminezhad, A., Hidding, A., Bier, H., & Calabrese, G. (2024). In-Situ vs. Prefab 3D Printing Considerations for CO2-free Pop-up Architecture. SPOOL, 11(1), 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Bier, H. , Cervone, A., & Makaya, A. (2021). Advancements in designing, producing, and operating Off-Earth infrastructure. DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals). [CrossRef]

- Bier, H., Vermeer, E., Hidding, A., & Jani, K. (2021). Design-to-Robotic-Production of underground habitats on Mars. DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals). [CrossRef]

- Cervone (https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/adaptive-on-and-off-earth-environments/26964428).

- Cheng, F., Yen, C., & Jeng, T. (2021b). Object recognition and user interface design for vision-based autonomous robotic grasping point determination. Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia. [CrossRef]

- Estrin, Y., Dyskin, A., & Pasternak, E. (2011). Topological interlocking as a material design concept. Materials Science & Engineering. C, Biomimetic Materials, Sensors and Systems, 31(6), 1189–1194. [CrossRef]

- Estrin, Y., Krishnamurthy, V. R., & Akleman, E. (2022). Design of architectured materials based on topological and geometrical interlocking. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 15, 1165–1178. [CrossRef]

- Feist, S., Sanhudo, L., Esteves, V., Pires, M., & Costa, A. A. (2022). Semi-Supervised clustering for architectural modularisation. Buildings, 12(3), 303. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A. P. (1999). Technologies of the Incas and their Origins. Transactions - Newcomen Society for the Study of the History of Engineering and Technology/Transactions of the Newcomen Society, 71(1), 31–48. [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, T., & Mendis, P. (2022). Prefabricated Building Systems—Design and Construction. Encyclopedia, 2(1), 70–95. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z., Tian, C., Zhou, Z., & Yuan, Q. (2021). Discovery of key function module in complex mechanical 3D CAD assembly model for design reuse. Assembly Automation, 42(1), 54–66. [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A. M., Ezugwu, A. E., Abualigah, L., Abuhaija, B., & Heming, J. (2023). K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Information Sciences, 622, 178–210. [CrossRef]

- İşeri, O. K. , & Dino, İ. G. (2022). Building archetype characterization using K-Means clustering in urban building energy models. In Communications in computer and information science (pp. 222–236). [CrossRef]

- Jannasch, E. (2016). Fit forms and free forms of the Masonry Dome. Nexus Network Journal/Nexus Network Journal, 19(3), 599–617. [CrossRef]

- Koronaki, A., Shepherd, P., & Evernden, M. (2023). Fabrication-Aware joint clustering in freeform Space-Frames. Buildings, 13(4), 962. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., Park, J., Pulshashi, I. R., & Bae, H. (2013). Clustering and operation analysis for assembly blocks using process mining in shipbuilding industry. In Lecture notes in business information processing (pp. 67–80). [CrossRef]

- Ossama, O., Mokhtar, H. M., & Sharkawi, M. E. E. (2012). Dynamic k-means: a clustering technique for moving object trajectories. International Journal of Intelligent Information and Database Systems, 6(4), 307. [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, W., & Gawell, E. (2016). Voronoi diagrams – rod structure research models in architectural and structural optimization. Mazowsze, Studia Regionalne, 2016(19), 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S. G., Eng, M., Krishnamurthy, V. R., & Akleman, E. (2019). Delaunay Lofts: A biologically inspired approach for modeling space filling modular structures. Computers & Graphics, 82, 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Teng, T., Jia, M., & Sabin, J. E. (2020). Scutoid Brick - The Designing of Epithelial cell inspired-brick in Masonry shell System. eCAADe Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Tessmann, O. (2012). Topological interlocking assemblies. eCAADe Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S., Musil, J., Dierckx, J., Gallou, I., & De Kestelier, X. (2016). Autonomous additive construction on Mars. Earth and Space 2016. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Link to Rhizome: http://cs.roboticbuilding.eu/index.php/Rhizome2. |

| 2 |

Link to Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gravity_of_Mars. |

| 3 |

Link to Explicit Bricks: https://gramaziokohler.arch.ethz.ch/web/e/lehre/185.html. |

| 4 |

Link to Delaunay Lofts: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0097849319300822. |

| 5 |

Link to Scutoid cell: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-05376-1. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).