1. Introduction

The rapidly increasing demand for calcium and energy for milk synthesis during early lactation in dairy cows frequently exceeds dietary intake, increasing the risk of hypocalcemia and ketosis [

1]. Clinical hypocalcemia, defined by blood calcium levels < 1.4 mmol/L, affects approximately 5% of cows [

2], whereas subclinical hypocalcemia (1.4 - 2.0 mmol/L) impacts approximately 50% of cows [

3,

4]. Simultaneously, 2% - 15% of dairy cows develop clinical ketosis, and 40% - 60% experience subclinical ketosis [

5], primarily due to inadequate adaptation to the negative energy balance (NEB) during this period [

6]. Hypocalcemia and ketosis in dairy cows can negatively impact their productivity, fertility, and overall health [

7,

8].

Research has shown that dairy cows experiencing fewer health issues during early lactation tend to have higher milk production and more consistent lactation curves [

9]. Thus, mitigating NEB and enhancing calcium availability during early lactation can positively influence milk yield in subsequent periods. The milk composition can provide useful information on the health status of dairy cows during early lactation. Research has demonstrated that the concentrations of certain minerals in milk are influenced not only by dietary element concentrations [

10] but also by the health status of the cows [

11] and the dietary calcium level, which affects the absorption and metabolism of other minerals (particularly P, Mg, Fe, and Zn) [

12,

13]. Moreover, milk fatty acid profiles serve as noninvasive indicators of the energy and metabolic status of early-lactating cows by reflecting the extent of body fat mobilization [

14,

15]. This is because fatty acids derived from adipose tissue differ from those synthesized

de novo from dietary sources [

16].

Calcium propionate is a valuable source of calcium and gluconeogenetic precursors (Goff et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2022b). Previous studies have shown that calcium propionate can increase milk yield, prevent hypocalcemia and alleviate NEB in early-lactating cows [

17,

18]. It may also influence adipose tissue mobilization [

19] and affect milk fatty acid profiles. Dietary supplementation with calcium propionate increases dietary calcium levels and improves the health status of dairy cows, which may consequently influence milk mineral concentrations. However, few studies have examined how dietary calcium propionate supplementation during early lactation affects lactation performance during the peak of lactation, as well as milk mineral composition and fatty acid profiles.

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of calcium propionate supplementation on productive performance during the peak of lactation and on milk mineral composition and fatty acid profiles during early lactation. We hypothesized that increasing the calcium and gluconeogenetic precursor supply through calcium propionate supplementation during early lactation would enhance subsequent lactation performance. Additionally, we hypothesized that calcium propionate supplementation would alter milk mineral composition and fatty acid profiles by influencing mineral absorption and adipose tissue mobilization.

4. Discussion

Most dairy cows reach their peak milk yield between 45 and 100 DIM [

30], after which the milk yield gradually decreases. The higher milk yield in the groups supplemented with calcium propionate than in the CON group suggested that calcium propionate supplementation to dairy cows during early lactation had a positive impact on lactation performance. High lactation persistency, associated with health status in early lactation, is linked to a slow decrease in milk yield after peak production [

31]. The peak lactation performance is significantly influenced by nutrition and management practices during early lactation. Calcium propionate can improve milk yield in dairy cows during early lactation [

17]. Furthermore, milk yield during early lactation is positively correlated with extended lactation performance [

32]. However, high milk production also increases the risk of elevated SCC [

33]. Notably, milk lactose, which serves as the predominant osmoregulatory substance in milk, is negatively associated with SCC in milk [

34]. The milk yield of the calcium propionate groups was greater than that of the other groups. The calcium propionate-supplemented groups presented greater milk yield. Consequently, the increase in both milk SCC and milk yield may contribute to the linear decrease in milk lactose content. Despite this reduction, the average milk lactose yield in the calcium propionate-supplemented groups remained numerically greater than that in the CON group.

The milk Ca concentration in the study was not affected by dietary calcium propionate feeding levels. The blood Ca concentration is strictly regulated by parathyroid hormone, calcitonin, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, which control Ca absorption, excretion, and bone metabolism [

35]. The lowest blood calcium levels occur approximately 12 to 24 hours after calving [

36]. Blood calcium levels are subsequently maintained at a normal level through the mobilization of bone calcium. At the sampling time points (7, 21, and 35 DIM), the stable blood Ca concentration resulted in an unchanged milk Ca concentration. The supplementation of calcium in feed is beneficial for reducing the mobilization of bone calcium. Additionally, the dietary Ca concentration is inversely related to the milk P concentration [

37]. It has been reported that diets with high levels of Ca can adversely affect Mg absorption in ruminants [

38,

39]. Therefore, in this study, the milk Mg and P concentrations during early lactation decreased linearly with increasing levels of calcium propionate.

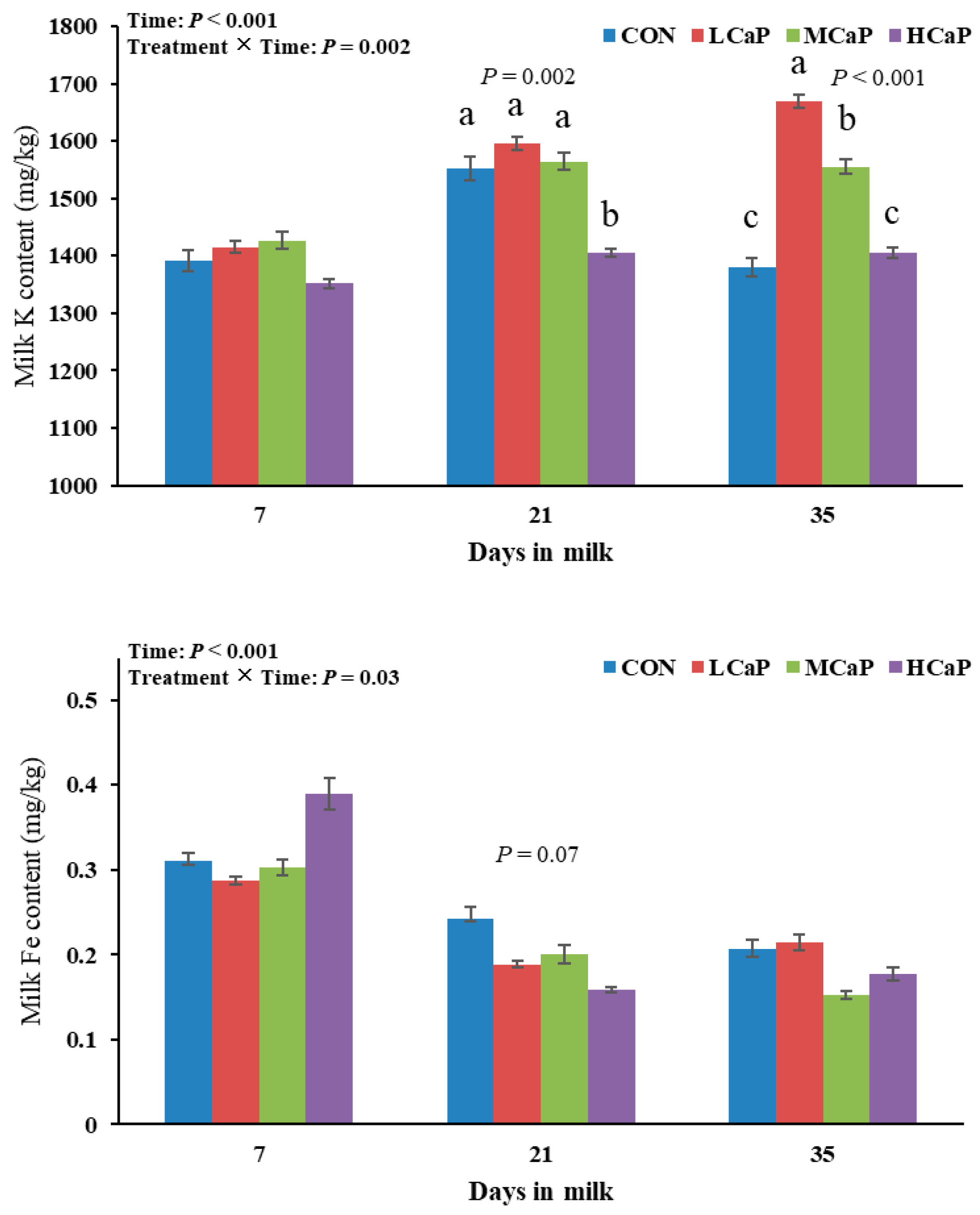

K plays roles in regulating acid‒base balance, maintaining osmotic pressure, transducing signals, transmitting nerve impulses, and contracting muscle [

40]. Toscano et al. [

41] reported a negative correlation between the milk K concentration and the serum β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) concentration. Dietary calcium propionate supplementation can decrease the blood BHB concentration [

18], which may increase the milk K concentration. Increasing the dietary calcium concentration can increase K absorption [

42] and the serum K concentration [

43] in dairy cows. However, the milk K concentration decreased when calcium propionate was supplemented at 500 g/d. This increase was accompanied by a decrease in DMI in the HCaP group (21.20 kg/d) compared with the MCaP group (22.87 kg/d) in early lactation, as previously reported [

17]. Zinc is important for immune function, cell division, and protein synthesis [

44]. The improved metabolic status resulting from dietary supplementation with calcium propionate [

19] might enhance Zn absorption in the intestines of dairy cows. However, diets high in Ca can reduce Zn absorption and balance [

45]. Consequently, the milk Zn concentration tended to change quadratically with increasing calcium propionate feeding levels during early lactation, peaking in the LCaP group.

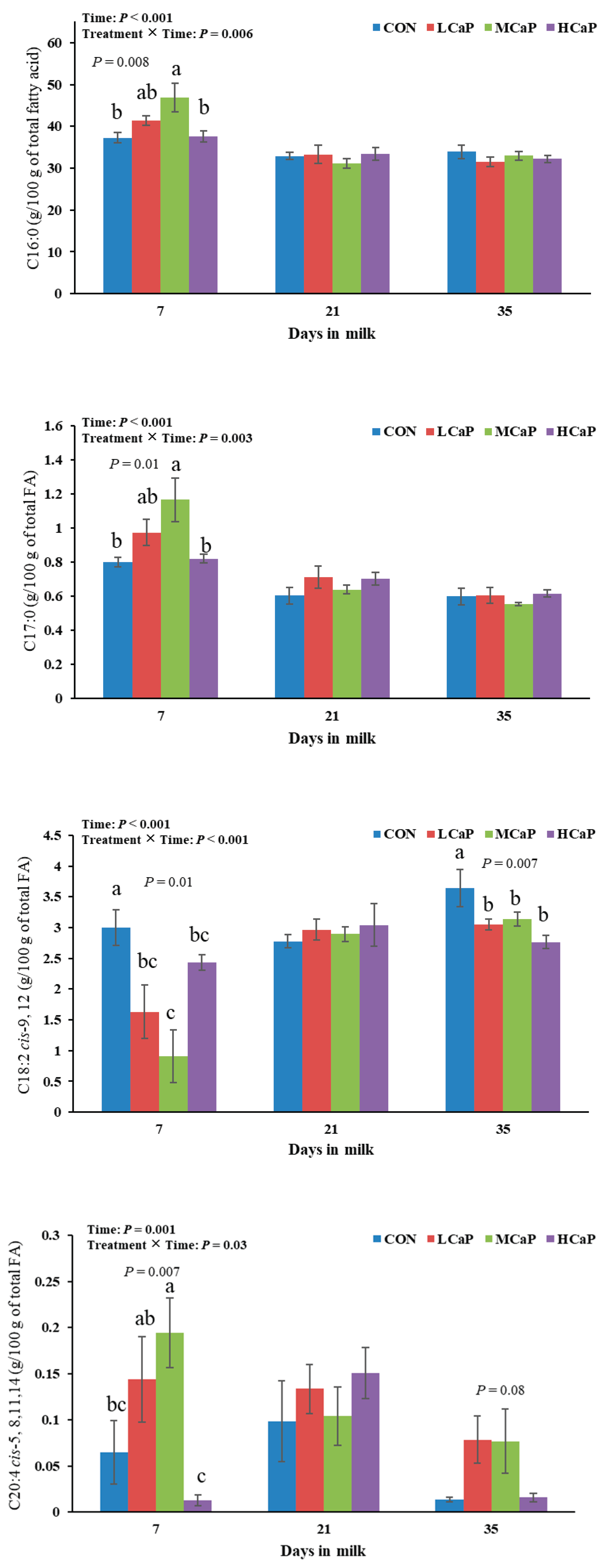

Because of the high energy requirement of milk production, dairy cows experience NEB during early lactation. The milk fatty acid profiles of dairy cows in early lactating cows are useful indicators for identifying NEB status [

46]. When a cow is in NEB status, a greater percentage of preformed fatty acids from body fat reserves and a lower percentage of

de novo fatty acids from the diet are used to produce milk fat. Propionate plays a crucial role in alleviating NEB in early-lactating dairy cows by promoting glucose synthesis. The levels of short- and medium-chain fatty acids, which are synthesized primarily

de novo in the mammary glands of dairy cows, decrease during NEB in early lactation [

46]. Although the sum of the SFAs did not differ among the four groups in this study, the proportions of C6:0, C8:0, and C12:0 linearly decreased with increasing levels of calcium propionate. Many studies have demonstrated that dietary supplementation with monensin, an ionophore antibiotic, can alter rumen bacterial population fermentation toward increasing the propionate proportion and decreasing the acetate:propionate ratio, consequently reducing the proportions of short-chain fatty acids in the milk of dairy cows [

47,

48]. Therefore, in this study, the reduced proportions of these fatty acids may be partly attributed to the increased propionate intake associated with increased levels of calcium propionate. Notably, C17:0 is synthesized

de novo from ruminal propionate [

49]. In a study by Zhang et al. [

17], dairy cows supplemented with calcium propionate at 500 g/d presented decreased DMI. Consequently, increased supplementation with calcium propionate resulted in a quadratic response to the milk C17:0 proportion during early lactation in the current study. The results of Churakov et al. [

46] showed that the C18:0 and C18:1

cis-9 concentrations in milk were the best variables for detecting the severity of NEB in cows. Pacheco-Pappenheim et al. [

50] also reported that dairy cows with NEB status mobilized more C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1

cis-9 from body fat reserves, leading to increased proportions of these fatty acids in milk fat. The previous results of Zhang et al. [

19] showed that increasing calcium propionate feeding levels quadratically changed milk yield, with the greatest value observed in the MCaP group. However, calcium propionate supplementation did not significantly alter the proportions of these fatty acids in milk in the present study, suggesting that the extra energy requirement for increased milk yield was derived from feed nutrition (22.87 kg/d in the MCaP group vs 21.71 kg/d in the CON group in early lactation) [

17] rather than body fat reserves. Wang et al. [

51] reported that inulin could reduce the proportion of C18:2

cis-9,12 (linoleic acid) in milk and increase the propionate concentration in the rumen. The decrease in C18:2

cis-9, 12 may be related to the increased supplementation of propionate, which improved the biohydrogenation of fatty acids by rumen microorganisms and quadratically changed the toxic effects of PUFAs, as suggested by Lock et al. [

52]. Further research should investigate how calcium propionate affects the biohydrogenation of fatty acids in early-lactating dairy cows.

The energy status of dairy cows in early lactation affects the origin of fatty acids for the synthesis of milk fat in the mammary gland [

50]. It has been reported that body fat mobilization due to NEB increases the proportion of LCFAs (i.e., C > 16) in milk [

16]. However, in this study, calcium propionate did not affect the proportion of LCFAs. It was hypothesized that the increased energy requirement for increased milk yield in the LCaP and MCaP groups [

19] was met through dietary intake; therefore, fat mobilization was not affected. PUFAs, which are exclusively obtained from dietary sources [

53], were lower in the groups supplemented with calcium propionate than in the CON group. This may be associated with the increased milk production in these groups supplemented with calcium propionate [

19].