Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

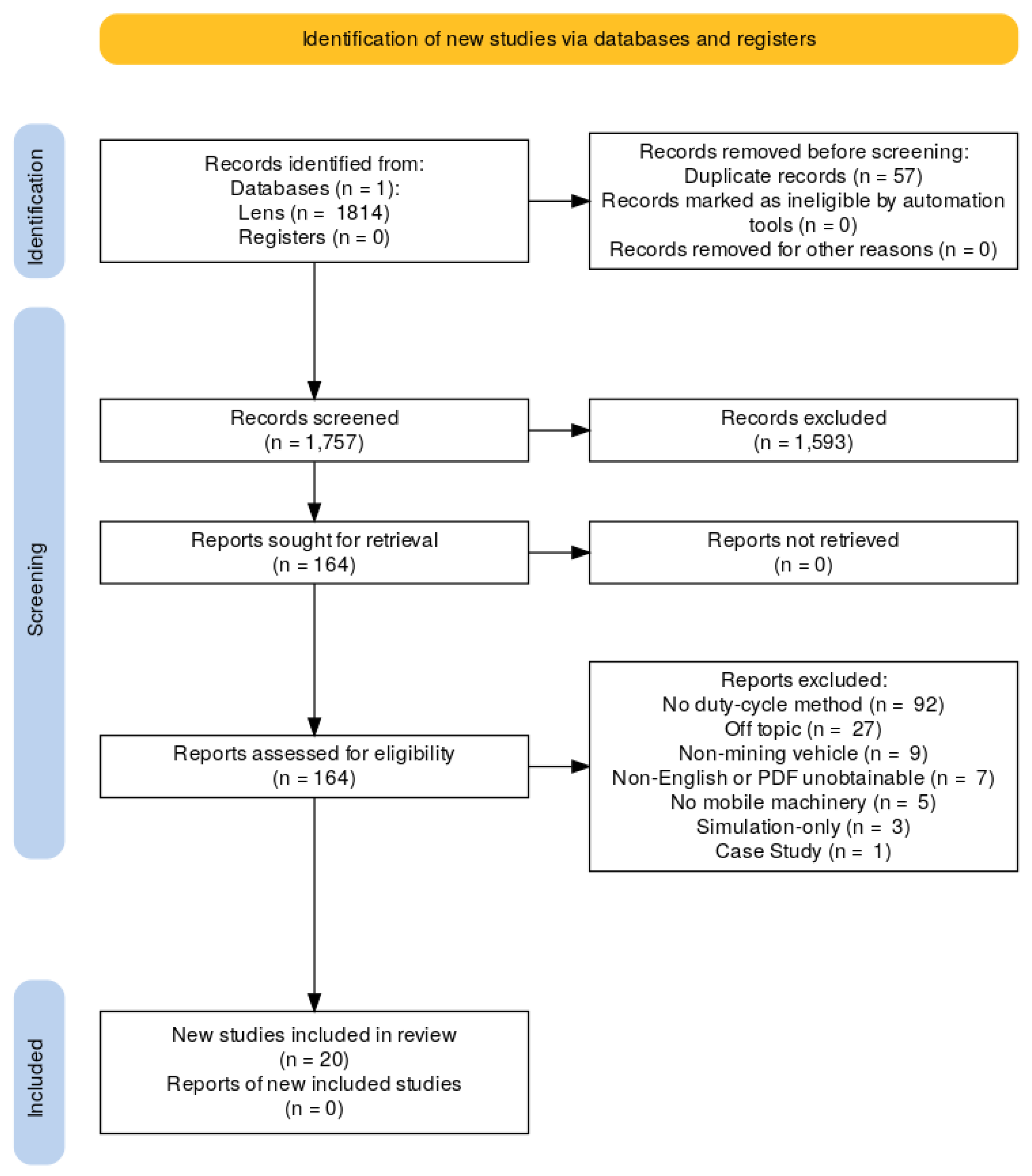

Background: Accurate operational cycle detection underpins maintenance, production analytics and energy management for mobile equipment in mining. Yet no review has investigated the landscape of operational cycle detection literature in mining. Methods: Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses, Scoping Review extension (PRISMA-ScR) framework, we searched the Lens database on June 27, 2025, for records published 2000–2025 that segment mobile mining vehicle telemetry into discrete operating modes. After de-duplication (n = 1,757) and two-stage screening, 20 empirical studies met all criteria (19 diesel, 1 battery-electric). Due to the sparse research involving battery electric vehicles (BEVs) in mining, three articles performing cycle detection on heavy-duty vehicles in a similar operational context to mining are synthesized. A bespoke three-axis Transferability Lens—created to measure cross-domain applicability of modelling approaches—was applied to four expert-selected passenger BEV studies to investigate cross-domain synthesis. Results: Early diesel work used single-sensor thresholds, often achieving >90\% site-specific accuracy, while recent studies increasingly employ types of neural networks using multivariate datasets. While the cycle detection research on mining BEVs, even supplanted with additional heavy-duty BEV studies, is sparse, similar approaches are favoured. The transferability appraisal suggests only moderate sensor-mapping and retraining effort when adapting automotive BEV classifiers to mining vehicle cycle detection. Conclusions: Persisting gaps in the literature include the absence of public mining datasets, inconsistent evaluation metrics, and limited real-time validation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Comprehensive synthesis of operational cycle detection methods for mobile mining equipment.

- Assessment of the applicability of automotive BEV approaches to mining environments.

- Gap analysis identifying unresolved challenges such as the scarcity of public data sets and the lack of real-time deployment.

2. Methods

2.1. Search and Selection Strategy

2.2. Data Extraction and Charting Process

2.3. Synthesis of Results

2.4. Transferability Lens and Rationale for Hand-Picked Exemplars

- Transfer distance: near, moderate, or far, reflecting vehicle class and terrain similarity.

- Dataset-shift type: covariate, prior-probability, concept, or mixed.

- Context alignment: high, medium, or low overlap in operating environment layout, grade profile, and payload regime.

3. Operational Cycle Detection for Diesel Mobile Mining Equipment

3.1. Sensors, Data Processing and Feature Engineering

- Hydraulic system pressure: These sensors measure pressure fluctuations in the lift, tilt, and pump circuits of the hydraulic system. Their near-rectangular pulses clearly segment the loader cycle into phases such as loading, hauling, dumping, and transiting.

- Driveline kinematics: This family includes gear selection, engine revolutions per minute (RPM), and ground speed sensors. These signals help infer machine intent and movement patterns, such as identifying dumping while stationary through a spike in RPM at zero speed.

- Brake-system hydraulics: These sensors capture pressure changes in the service and retarder brake lines. The spikes in these signals serve as strong indicators of dumping or controlled descents on ramps, which aids in phase detection.

- Auxiliary streams: This group comprises lower-rate signals, such as fuel flow and turbo boost, and higher-rate streams, such as those originating from Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) and the Global Positioning System (GPS). These enrich cycle detection models by providing load, terrain, and location cues; especially useful when primary sensors are unavailable or noisy.

3.2. Supervised Methods

3.2.1. Expert Systems

3.2.2. Machine Learning

3.3. Unsupervised and Semi-Supervised Methods

3.4. Diesel Specific Trends & Key Limitations

4. Battery-Electric Vehicle Operational Cycle Detection: Evidence from Mining and Lessons from the Automotive Sector

4.1. Unique Challenges of BEV Duty Cycles

- Aggressive speed transients: Instantaneous peak torque enables sharper accelerations and decelerations. BEV acceleration phases can be up to 26% longer, and with 18% higher magnitude, than comparable ICE phases—leaving less time for steady cruising and complicating phase detection [29].

- Load asymmetry and State of Charge (SoC) variability: BEVs suffer from power derating under low battery or high temperature, making the same task look different in different contexts (a major challenge for supervised models that assume consistency).

4.2. Electric Haul-Truck Duty-Cycle Classification

4.3. Adjacent heavy-duty BEV studies

4.4. Emerging Trends and Limitations

5. Cross-Domain Transferability

6. Discussion

6.1. Trends in Operational Cycle Detection

- Shift from Thresholds to Learned Representations: Across both diesel and BEV platforms, there is a clear progression from hand-crafted rule sets to learned representations. Diesel studies have moved from single-variable and threshold-based, to supervised deep learning architectures such as CNNs and Bi-LSTMs [3,18]. Similarly, BEV studies employ PCA-based feature compression and clustering pipelines that allow for flexible, data-driven phase discovery without predefined thresholds [30,31].

- Emergence of Modular, Pipeline-Oriented Architectures: A common architectural pattern is becoming apparent: segmentation, then dimensionality reduction, then clustering or classification, ending with post-processing or synthesis. This modular structure is evident in both unsupervised and supervised workflows, including [21] for diesel and [26,30] for BEVs. It offers a flexible foundation for adapting classifiers across platforms and signal types.

- Toward Quantitative, Simulation-Based Validation: Earlier work often reported only qualitative agreement or raw cycle counts. Recent studies are trending toward more standardized, simulation-based validation: diesel classifiers are now evaluated using segment-level precision and recall [9,18], while BEV studies benchmark reconstructed cycles using energy-consumption errors < 5% [30,31]. This shift improves comparability and promotes methodological rigour.

- Vehicle and Context Specific Operational Cycle Design: Diesel and BEV cycle detection pipelines are increasingly tailored to the operating conditions and mechanical realities of specific vehicle classes. Diesel studies differentiate loaders from haul trucks in both signal use and model architecture [3,18], while BEV research encodes domain-specific constraints such as gradient bins [32], shovel-resistance [30] or payload mass [31]. This marks a clear departure from generalized or automotive-style operational cycles.

6.2. Cross-domain Lessons

6.3. Research Gaps and Limitations

6.4. Future Research Opportunities

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEV | Battery-Electric Vehicle |

| CAN | Controller Area Network (vehicle data bus) |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DBSCAN | Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise |

| ECU | Electronic Control Unit |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| VBGMM | Variational Bayesian Gaussian Mixture Model |

| HSMM | Hidden Semi-Markov Model |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| KPCA | Kernel Principal Component Analysis |

| LHD | Load–Haul–Dump (vehicle) |

| LOWESS | Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory network |

| Bi-LSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory network |

| OBD | On-Board Diagnostics |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – Scoping Review extension |

| RPM | Revolutions Per Minute |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SoC | State of Charge (battery) |

| TPM | Transition Probability Matrix |

Appendix A. Search Strategy

References

- Fuente, R.d.l.; Radrigan, L.; Morales, A.S. Enhancing Predictive Maintenance in Mining Mobile Machinery through a TinyML-enabled Hierarchical Inference Network, 2024. arXiv:2411.07168 [cs] version: 1. [CrossRef]

- Timusk, M.; Lipsett, M.G.; McBain, J.; Mechefske, C.K. Automated Operating Mode Classification for Online Monitoring Systems. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics 2009, 131, 041003–. Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Skoczylas, A.; Rot, A.; Stefaniak, P.; Śliwiński, P. Haulage Cycles Identification for Wheeled Transport in Underground Mine Using Neural Networks. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 23, 1331–1331, Section: 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, G.; Masih-Tehrani, M.; Pourbafarani, Z. Development of Wheel Loader Duty Cycle Using Hybrid Markov Chain and Genetic Algorithm. SAE International Journal of Commercial Vehicles 2021, 15, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Liu, M.; Chen, X. Research Status and Development Trend of Underground Intelligent Load-Haul-Dump Vehicle—A Comprehensive Review. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Schafrik, S.; Kolapo, P.; Agioutantis, Z.; Sottile, J. Equipment and Operations Automation in Mining: A Review. Machines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epiroc AB. Epiroc wins large order for battery-electric vehicles for Canadian gold and copper mine. Press release, 2025. Ordered BEV versions of Boomer M20 SG, Scooptram ST18 SG, Scooptram ST14 SG and Minetruck MT42 SG for Hudbay Minerals’ Lalor mine; order booked Q1 2025 and valued at MSEK 100.

- Beltrami, D.; Iora, P.; Tribioli, L.; Uberti, S. Electrification of Compact Off-Highway Vehicles—Overview of the Current State of the Art and Trends. Energies 2021, 14, 5565. Number: 17 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Machine Learning Approach to Underground Load Haul Dump Cycle Segmentation. Final Report 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawelski, D.; Jachnik, B.; Stefaniak, P.; Skoczylas, A. ICCCI (CCIS Volume) - Haul Truck Cycle Identification Using Support Vector Machine and DBSCAN Models 2020. pp. 338–350. Place: Germany Publisher: Springer International Publishing Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, E.; Frisk, E.; Krysander, M.; Pettersson, R. Automated Usage Characterization of Mining Vehicles For Life Time Prediction. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 11950–11955, Section: 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koperska, W.; Skoczylas, A.; Stefaniak, P. ICCCI (CCIS Volume) - A Simple Method of the Haulage Cycles Detection for LHD Machine. 2020. pp. 326–337. Place: Germany Publisher: Springer International Publishing Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, T.; Michalak, A.; Zimroz, R.; Sliwinski, P.; Kaniewski, T. An Algorithm for Determining Unloading Cycles in Dump Truck. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 362, 012111–. Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Krot, P.; Sliwinski, P.; Zimroz, R.; Gomolla, N. The identification of operational cycles in the monitoring systems of underground vehicles. Measurement 2020, 151, 107111–. Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Markham, G.; Seiler, K.M.; Balamurali, M.; Hill, A.J. Load-Haul Cycle Segmentation with Hidden Semi-Markov Models - 2022 IEEE 18th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE). 2022 IEEE 18th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE) 2022, pp. 447–454. Publisher: IEEE Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Polak, M. IDENTIFICATION OF LOADING PROCESS BASED ON HYDRAULIC PRESSURE SIGNAL - SGEM International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference EXPO Proceedings. SGEM International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference EXPO Proceedings 2016. Publisher: Stef92 Technology Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Gu, Q.; Meng, Y.; Bai, G.; Ding, D. The load-haul-dump operation cycle recognition based on multi-sensor feature selection and bidirectional long short-term memory network. Measurement and Control 2023, 56, 1523–1533, Section: 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, J.; Odelius, J. Detecting operation regimes using unsupervised clustering with infected group labelling to improve machine diagnostics and prognostics. Operations Research Perspectives 2018, 5, 232–244, Section: 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczylas, A.; Stefaniak, P.; Anufriiev, S.; Koperska, W. Deep Learning for Ore Haulage Monitoring: Vibrational Analysis Using a VGG16 Network. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 33138–33147, Section: 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śliwiński, P.; Andrzejewski, M.; Kaniewski, T.; Hebda-Sobkowicz, J.; Zimroz, R. Mining Goes Digital - Selection of variables acquired by the on-board monitoring system to determine operational cycles for haul truck vehicle 2019. pp. 525–533. Publisher: CRC Press Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, P.; Zimroz, R.; Obuchowski, J.; Sliwinski, P.; Andrzejewski, M. An Effectiveness Indicator for a Mining Loader Based on the Pressure Signal Measured at a Bucket’s Hydraulic Cylinder. Procedia Earth and Planetary Science 2015, 15, 797–805, Section: 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodecki, J.; Michalak, A.; Stefaniak, P. Review of smoothing methods for enhancement of noisy data from heavy-duty LHD mining machines. E3S Web of Conferences 2018, 29, 00011–. Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Wodecki, J.; Góralczyk, M.; Krot, P.; Ziętek, B.; Szrek, J.; Worsa-Kozak, M.; Zimroz, R.; Śliwiński, P.; Czajkowski, A. Process Monitoring in Heavy Duty Drilling Rigs—Data Acquisition System and Cycle Identification Algorithms. Energies 2020, 13, 6748–. Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Wyłomańska, A.; Zimroz, R. Signal segmentation for operational regimes detection of heavy duty mining mobile machines – a statistical approach 2014. Section: 0.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W. Research of Driving Cycle Construction for Electric Drive Mining Truck Based on Travelling Analysis Method 2018. pp. 117–126. Place: Germany Publisher: Springer Singapore Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Stachowiak, M.; Koperska, W.; Jachnik, B.; Stefaniak, P. TRACKING OPERATION REGIMES OF THE LHD MACHINES BASED ON HYDRAULIC SIGNAL SIGNAL SMOOTHING ISSUES - SGEM International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference EXPO Proceedings. SGEM International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference EXPO Proceedings 2020, 20, 383–394. Publisher: STEF92 Technology Section: 0. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition, 2015, [arXiv:cs.CV/1409.1556].

- Ye, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J. Driving cycle electrification and comparison. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2023, 123, 103900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Xu, M.; Lin, T.; Chen, Q.; Cai, S.; Guo, T. Working cycle condition construction for electric wheel loader based on principal component analysis and cluster analysis. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 2024, 238, 2905–2919, Section: 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Guan, S. Developing high-precision battery electric forklift driving cycle with variable cargo weight. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2024, 136, 104443–104443, Section: 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.Y.; Ng, K.W. Developing electric bus driving cycles with significant road gradient changes: A case study in Hong Kong. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 98, 104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzi, L.; Delogu, M.; Pierini, M. Development of driving cycles for electric vehicles in the context of the city of Florence. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2016, 47, 299–322. Publisher: Elsevier BV. [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Wang, G. Development Method for the Driving Cycle of Electric Vehicles. Energies 2022, 15, 8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, T.; Esbel, O.; Mühlhäuser, M.; Guinea, A.S. Unsupervised Driving Event Discovery Based on Vehicle CAN-data. 2022, pp. 4169–4174. arXiv:2301.04988 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, X. Development of a Typical Urban Driving Cycle for Battery Electric Vehicles Based on Kernel Principal Component Analysis and Random Forest. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 15053–15065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallac, D.; Bhooshan, S.; Chen, M.; Abida, K.; Sosic, R.; Leskovec, J. Drive2Vec: Multiscale State-Space Embedding of Vehicular Sensor Data, 2018, [arXiv:cs.LG/1806.04795].

- Walkowicz, K.; Kelly, K.; Duran, A. Fleet DNA; National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2014.

- Lustbader, J.; Kotz, A. Medium- and Heavy-Duty Truck Duty Cycles, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions, 2017, [arXiv:cs.AI/1705.07874].

- Saxena, A.; Goebel, K. Turbofan Engine Degradation Simulation Data Set. NASA Prognostics Data Repository, NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA, 2008. Accessed: 2025-08-05.

- Takenaka, K.; Bando, T.; Nagasaka, S.; Taniguchi, T.; Hitomi, K. Contextual scene segmentation of driving behavior based on double articulation analyzer. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 2012; pp. 4847–4852. [CrossRef]

- Radac, M.B.; Chirla, D.P. Near real-time online reinforcement learning with synchronous or asynchronous updates. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 17158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Author–Year) | Population / Platform | Method & Signals | Data & Validation | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gawelski et al., 2020 [11] | Haul trucks (diesel) | SVM + DBSCAN on 1 Hz CAN (SPEED, ENGRPM, SELGEAR, BRAKEP, FUELS); 5 s MA; HYDOILP used only for training prep. | ∼10 shifts; compared to HYDOILP-based algorithm and manual counts. | Agreement with HYDOILP/operator logs; event-detection reliability ∼90%. |

| Jakobsson et al., 2020 [12] | Mine truck (earthmoving) | CNN (vs SVM/RF/KNN/MLP) on 3-axis accelerometer (50 Hz); fixed 2 s windows; auto labels from metadata (payload, speed). | Weeks of data; train 3,016/class; oversampled 204,527/class; 80/20 split; Butterworth post-filter. | Balanced test: accuracy >96%; per-mode TPR: Idle 0.93, Hauling 0.97, Empty 0.95, Loading 0.95, Unloading 0.94. |

| Karimi et al., 2021 [4] | Wheel loader (Komatsu WA470) | Hybrid Markov chain + GA; K-means; smartphone GPS. | ∼80,000 points; consistency; ADVISOR simulation vs EPA/EU cycles. | Constructed cycles consistent; evaluation via fuel/emissions (no classifier accuracy). |

| Koperska et al., 2020 [13] | LHD (wheel loader) | Convolution of smoothed HYDOILP (1 Hz from 100 Hz) with inverted step; LOWESS + variants. | 5 working days; >300 cycles; confusion matrix. | Overall acc. 96%; “driving full” sens./prec. ∼98.7%/97.5%; loading sens. 67.6%, prec. 99.5%. |

| Kozlowski et al., 2019 [14] | Dump truck | Thresholds on ENGRPM+BRAKEP; HYDOILP for verification. | 3 test sets (10/40/47 events). | Unloading feasible without HYDOILP; reliability ∼90% (limited metrics). |

| Krot et al., 2020 [15] | Underground haul trucks | Rule-based “virtual sensor” using BRAKEP, SELGEAR, SPEED, ENGRPM (1 Hz); HYDOILP ref. 15 Hz for tuning. | 3 sets; 97 unloading events; cross-set robustness. | Detection ∼90%; false positives ∼5%; suitable for online/post. |

| Markham et al., 2022 [16] | Haul truck (open-pit) | HSMM (unsupervised) on GPS position/velocity (5 s); Viterbi/EM; FMS for validation. | 25 trucks ∼24 h; manual subset of 24 cycles; precision/recall. | Load P/R 95.1/98.8%; Dump 87.1/91.1%; Cycle 86.7/90.8%. |

| Polak et al., 2016 [17] | Loader | Kalman smoothing + statistical break detection on bucket-cylinder pressure (1 Hz). | 2 days; 172,800 samples; 207 cycles; manual regime marks. | Accuracy: Unloading 74.4%, Driving full 75.9%, Driving empty 80.2%. |

| Qi et al., 2023 [18] | LHD (Sandvik LH514) | RF feature selection + Bi-LSTM; baselines VBGM/SVM/RF/LSTM on multi-sensor (20 params @ 5 s; 5 real-time). | Operational LHD data; weighted/per-mode F1. | Weighted F1 = 91.75%; per-mode F1: Load 0.95, Haul 0.95, Dump 0.83, Transit 0.87. |

| Saari & Odelius, 2018 [19] | Underground LHD (LH621) | Unsupervised VBGM on vibration (12.8 kHz) + Cardan speed (5 s). | 3 full days; cluster–label “infection” with small manual set; convergence across days. | Reasonable separation of regimes; loading prominent; limited quantitative metrics. |

| Skoczylas et al., 2023 [3] | Haul trucks; loaders | Deep/conv nets on SPEED, SELGEAR, FUELUS, ENGRPM (100 Hz → 1 Hz); trucks partly thresholded. | Initial 17,341 h (trucks) / 16,812 h (loaders); downsampled to 2-min/30-s; modified 10×10 CV. | Trucks mean acc. 93% (unloading 96%, loading 90%); loaders mean acc. 58% (one loader ∼90%). |

| Skoczylas et al., 2025 [20] | Haul trucks | VGG16 on IMU (3 accel + 3 gyro, ∼360 Hz); axis autoencoders; rule-based post-process. | 1,473 cycles; 2,462 h; 20 trucks; vs human detection; data-quality tiers. | With unloading: acc. 82.1%, R 85.8%, P 95.0%; extended (no unload): acc. 87.7%, R 95.7%, P 91.4%. |

| Śliwiński et al., 2019 [21] | Haul truck | ACF-based cyclicity + rule-based cleaning on 1 Hz multivariate CAN; HYDOILP reference. | Examples over 1 shift and 3 days; visual match. | Suggests SPEED + GEAR plus one of {BRAKE, TRNBPS, FUEL, TPS, INTAKEP} suffice; no numeric accuracy. |

| Stefaniak et al., 2015 [22] | Mining loader | Kalman smoothing + thresholding on bucket-cylinder pressure. | NR; expert validation. | Identifies “full bucket ride” and “empty backward after unloading”; no numeric metrics. |

| Timusk et al., 2009 [2] | Electromech. excavator (P&H TS4100); haul truck drives | Supervised LS/C4.5/NN/RBF/SVM with PCA/ICA/EFS on speed-segment and vibration features. | 45 h; ∼300 × 1-min records; ∼160 labeled speed profiles; 80% hold-back. | Best kNN+EFS error 6%; empty swing as low as 3%; vibration features improved accuracy. |

| Wodecki et al., 2018 [23] | LHD (wheel loader) | Compare MA/EMA/LR/RLR/QR/RQR smoothing on HYDOILP for threshold segmentation. | 280 min with 20 known cycles; % cycles detected. | Recovery vs known 20: MA 105%, EMA 115%, LR 145%, RLR 100%, QR 170%, RQR 100%. |

| Wodecki et al., 2020 [24] | Drill rigs (FaceMaster 1.7) | Thresholding; KDE-based thresholds; Hilbert demodulation (current); instantaneous frequency (acoustic). | 28 holes; compare vs on-board system. | All 28 holes recovered; regime statistics align across sources. |

| Wyłomańska & Zimroz, 2014 [25] | Heavy-duty mobile machines (loaders) | Second-moment R & C statistics on ENG_RPM; trapping-event detection. | Simulations + several hours of real ENG_RPM; visual/simulation validation. | R detects traps >3 samples; C >2; trapping events 17–28% of signal. |

| Zhang et al., 2019 [26] | Electric-drive mining truck (220 t) | PCA + density-peak clustering on speed/power/torque/grade; 10 s “short-stroke” windows. | 146 kinematic sequences; representative cycle vs field data. | Three categories (loaded/high power; idle/no power; braked/high speed); representative mirrors field. |

| Stachowiak et al., 2020 [27] | LHD (wheel loader; hydraulic) | HYDOILP 1 Hz; ten smoothing methods (MA, WMA, EMA, DEMA, HMA, ALMA, LR, QR, LOWESS, Kalman); cycle detection via convolution with inverted step (rule thresholds). | 3 h total across two samples: 1 h with 11 actual cycles; 2 h with 15 actual cycles; MA window 70 samples; validation by difference from actual counts and duration statistics. | LOWESS best: correct count for both samples with minimal shift. Sample 1 (11): most methods 0 diff; HMA ; LR ; Kalman . Sample 2 (15): LOWESS 0; MA ; EMA ; DEMA ; WMA ; HMA ; ALMA ; LR 0; QR ; Kalman . Kalman delayed; DEMA/HMA produced spurious short cycles. |

| Strategy | Key Study & Method | Label Economy | Headline Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fully generative discovery | Markham et al. (2022) [16]: Hidden Semi-Markov Model on symbolised five-second GPS fixes; physics rules only prune impossible transitions. | 0 manual labels | Retrieved 99% loading, 91% dumping modes; uncovered 24 cycles missing from the fleet log. |

| Event-anchored seeding | Gawelski et al. (2020) [11]: SVM learns the unloading pattern; DBSCAN clusters unload flags to bracket cycles. | Labels for one sub-event | Full duty-cycle trace generated without hydraulic or brake-pressure channels. |

| Cluster-first infection | Saari & Odelius (2018) [19]: VBGMM finds ten vibration-speed clusters; expert tags “infect” clusters with regime labels. | Minutes of tags | Identified idling at 100% accuracy; clean partitions for loading, hauling, transit. |

| Article | Vehicle Studied | Reason for Inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Ren et al. 2024 [30] | 5 t electric wheel loader | Loader-centric segmentation that embeds variable-mass and shovel-resistance peaks; demonstrates a CAN-bus → PCA + K-means pipeline with energy-error fidelity. |

| Tong & Guan 2024 [31] | Counter-balanced battery-electric forklifts | Double-layer Markov model captures dynamic payload profiles; large-scale (194 M points) micro-trip synthesis keeps 13 performance metrics within . |

| Tong & Ng 2023 [32] | Battery-electric buses on steep Hong Kong routes | Gradient-aware micro-trip assembly reproduces speed–acceleration statistics on slopes—an analogue for deep-ramp haulage. |

| Paper | Transfer Distance | Covariate Shift | Context Alignment | Sensor Mapping | Retraining | Feature Eng. | Final Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berzi et al., 2016 [33] | Moderate | Location-bound (city vs. mine) | Medium | Medium | Low | Low | Promising—extra work needed |

| Jing et al., 2022 [34] | Moderate | Region-specific vehicle & traffic | Medium | Low | Low | Low | Promising—needs further development |

| Kreutz et al., 2022 [35] | Moderate | Power-train signal variance | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low | Promising—strong on annotation reduction |

| Wang et al., 2021 [36] | Moderate | Localized driver & traffic patterns | Medium | Low | Low | Low | Promising—warrants mine-site validation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).