Submitted:

27 June 2024

Posted:

28 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

- frontal area [m2] by multiplying vehicle width and height [m] and applying a generic correction factor of 85% (Bowling, 2010) to account for areas not covered by the vehicle;

- average real-world energy consumption [kWh/100 km] and drive range [km] as the arithmetic mean of the minimum and maximum values obtained from EVD (2023);

- average real-world drive range [km] based on the energy consumption data obtained from Spritmonitor (2023), by assuming direct proportionality between certified and real-world energy consumption and the corresponding drive range.

3. Results

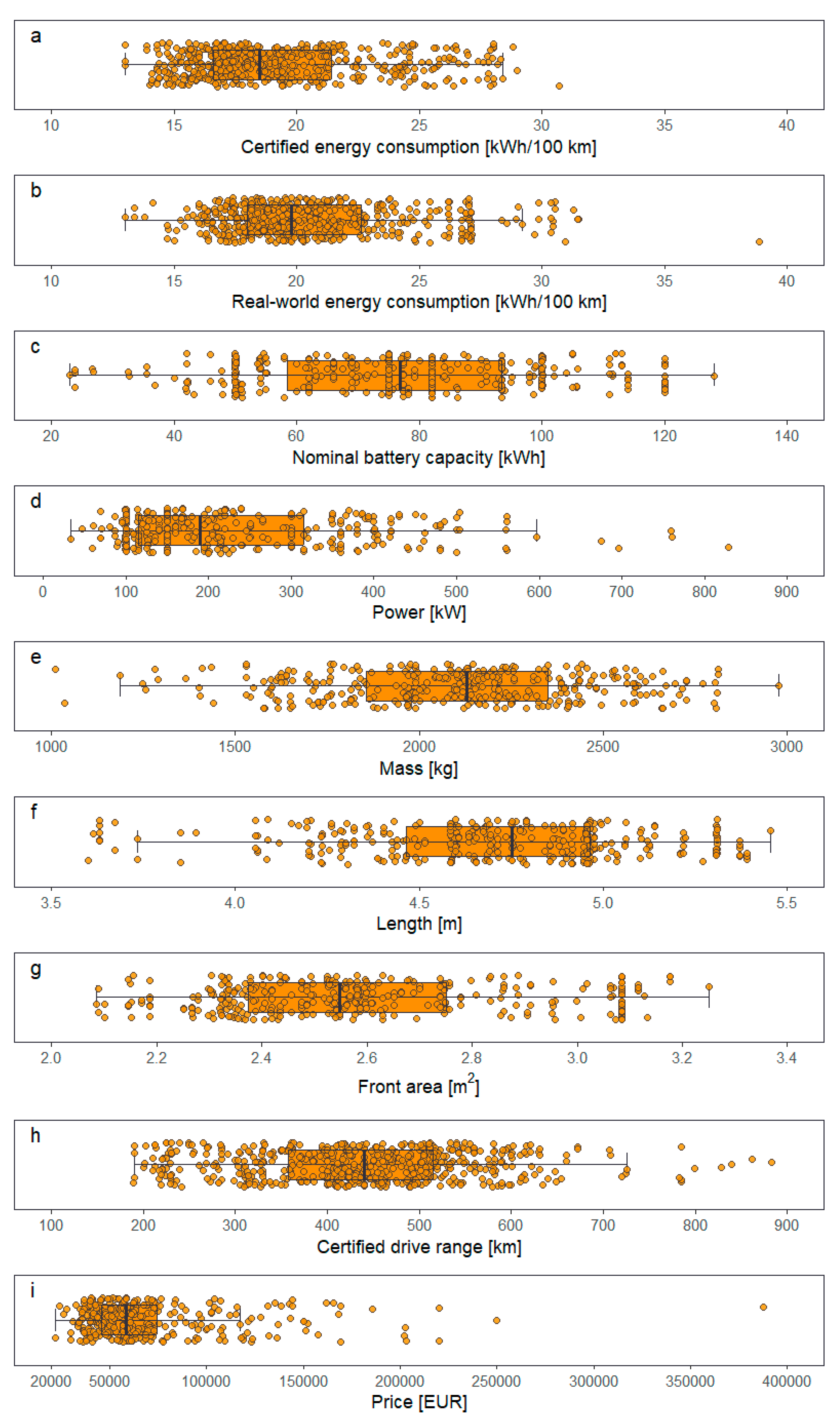

3.1. Overview – Vehicle Attributes

| Parameter [Unit] (Sample size) | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy consumption | |||||

| Certifieda [kWh/100 km] (501) | 19.4 | 3.8 | 18.5 | 13.0 | 30.7 |

| Certified - TEL [kWh/100 km] (312) | 18.5 | 3.4 | 17.6 | 13.0 | 28.3 |

| Certified - TEH [kWh/100 km] (189) | 20.7 | 3.9 | 19.8 | 144.3 | 30.7 |

| Real-worldb [kWh/100 km] (496) | 20.7 | 3.7 | 19.8 | 13.0 | 38.9 |

| Drive range, based on | |||||

| Certified energy consumptiona [km] (501) | 438 | 123 | 440 | 190 | 883 |

| Certified energy consumption - TEL [km] (312) | 449 | 128 | 455 | 190 | 883 |

| Certified energy consumption - TEH [km] (189) | 422 | 113 | 420 | 203 | 828 |

| Real-world energy consumptionb [km] (496) | 383 | 109 | 384 | 147 | 732 |

| Certified drive range per 1000 EUR vehicle price (549) | 7.00 | 2.47 | 7.02 | 1.34 | 17.17 |

| Real-world drive range per 1000 EUR vehicle price (493) | 6.50 | 2.06 | 6.69 | 1.25 | 11.00 |

| Nominal battery capacity [kWh] (342) | 76 | 22 | 77 | 23 | 128 |

| Usable battery capacity [kWh] (342) | 71 | 21 | 71 | 21 | 123 |

| Mass [kg] (342) | 2,102 | 351 | 2,128 | 1,012 | 2,975 |

| Power [kW] (342) | 230 | 139 | 190 | 33 | 828 |

| Frontal area [m2] (342) | 2.59 | 0.28 | 2.55 | 2.09 | 3.25 |

| Length [m] (342) | 4.71 | 0.39 | 4.75 | 3.60 | 5.45 |

| Width [m] (342) | 1.89 | 0.07 | 1.90 | 1.62 | 2.08 |

| Height [m] (342) | 1.62 | 0.14 | 1.61 | 1.35 | 1.94 |

| Pricec [EUR] (339) | 70,135 | 40,215 | 58,844 | 22,150 | 387,645 |

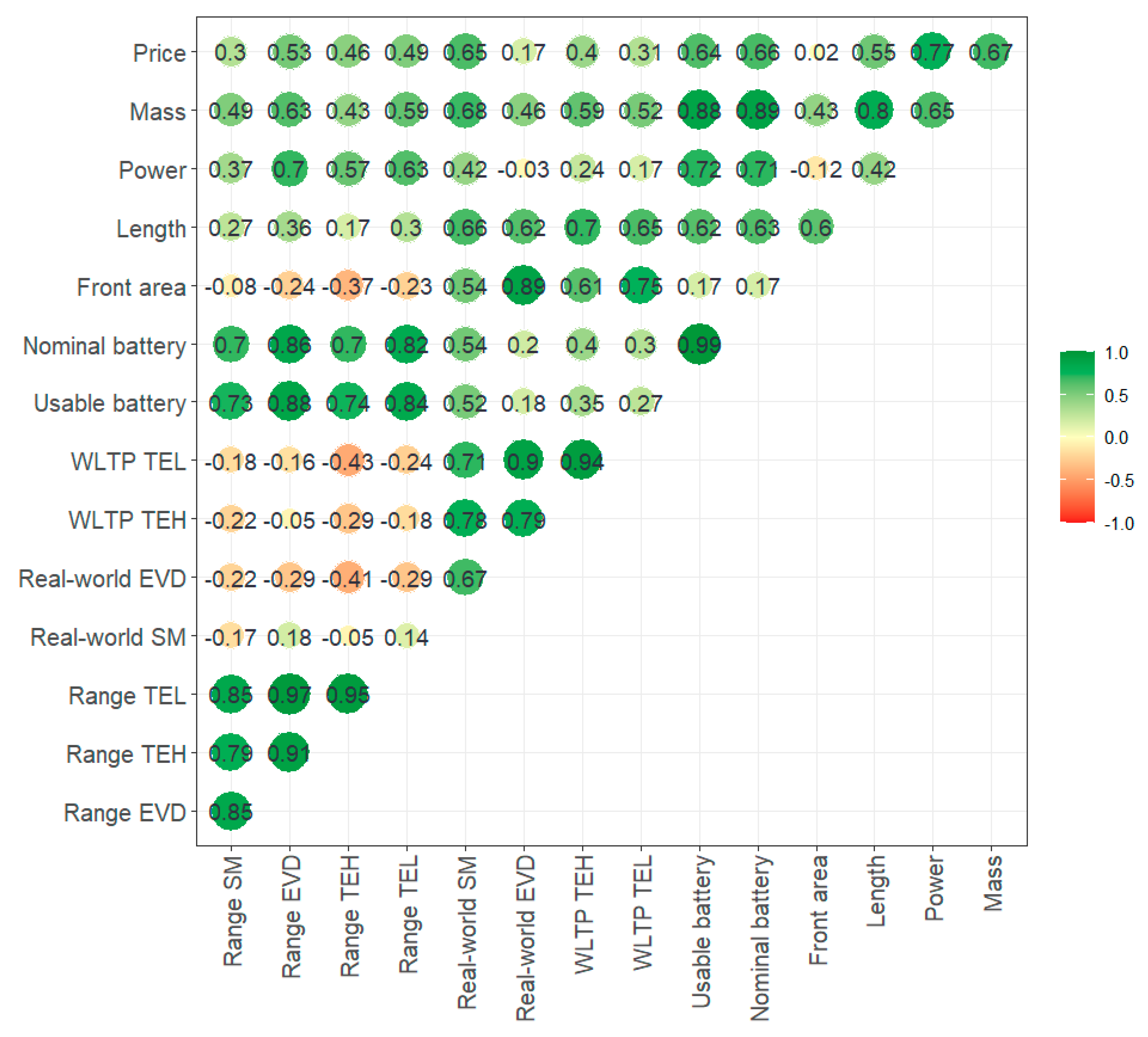

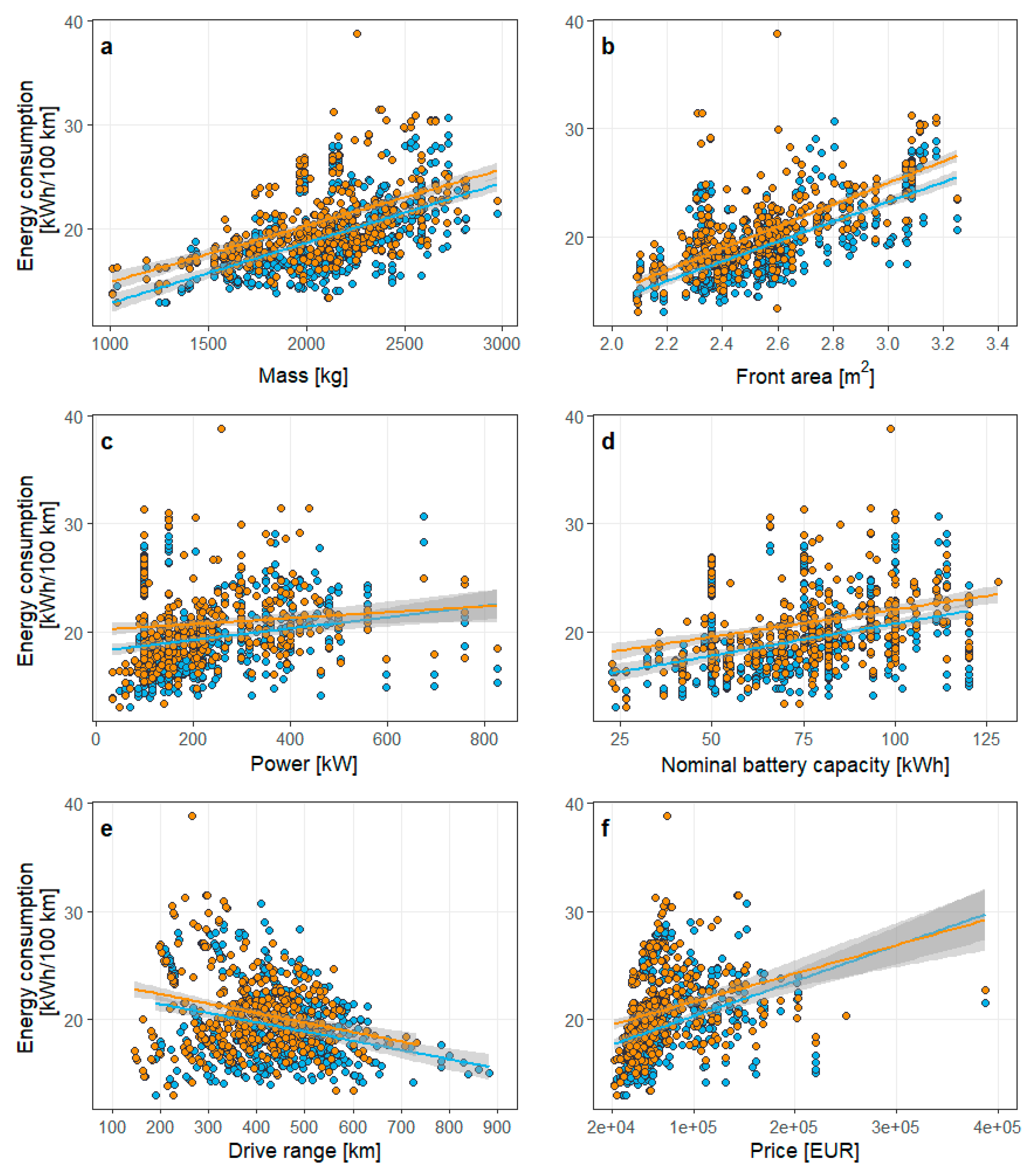

3.2. Regression Analyses – Efficiency Trade-Offs

- Each 100 kg of vehicle mass increases certified and real-world energy consumption by 0.20 ± 0.06 kWh/100 km and 0.17 ± 0.05 kWh/100 km, respectively (Figure 3a; Model 2); each doubling of mass increases certified and real-world energy consumption by around 24 ± 6% (Model 4).

- Each 1 m2 of frontal area increases certified and real-world energy consumption by 8.5 ± 0.6 kWh/100 km and 9.1 ± 0.5 kWh/100, respectively (Figure 3b; Model 2); each doubling in frontal area doubles the certified and real-world energy consumption (Model 4).

- Each 100 kW of rated power increases certified energy consumption by only 0.42 ± 0.18 kWh/100 km, whereas the effect on real-world energy consumption is insignificant (Figure 3c; Model 2); likewise, log-transformation suggests rated power does not affect significantly certified and real-world energy consumption (Model 4).

- Four-wheel drive does not significantly increase certified energy consumption but it tends to increase real-world energy consumption by 1.0 ± 0.3 kWh/100 km compared to two-wheel drivetrains (Model 2).

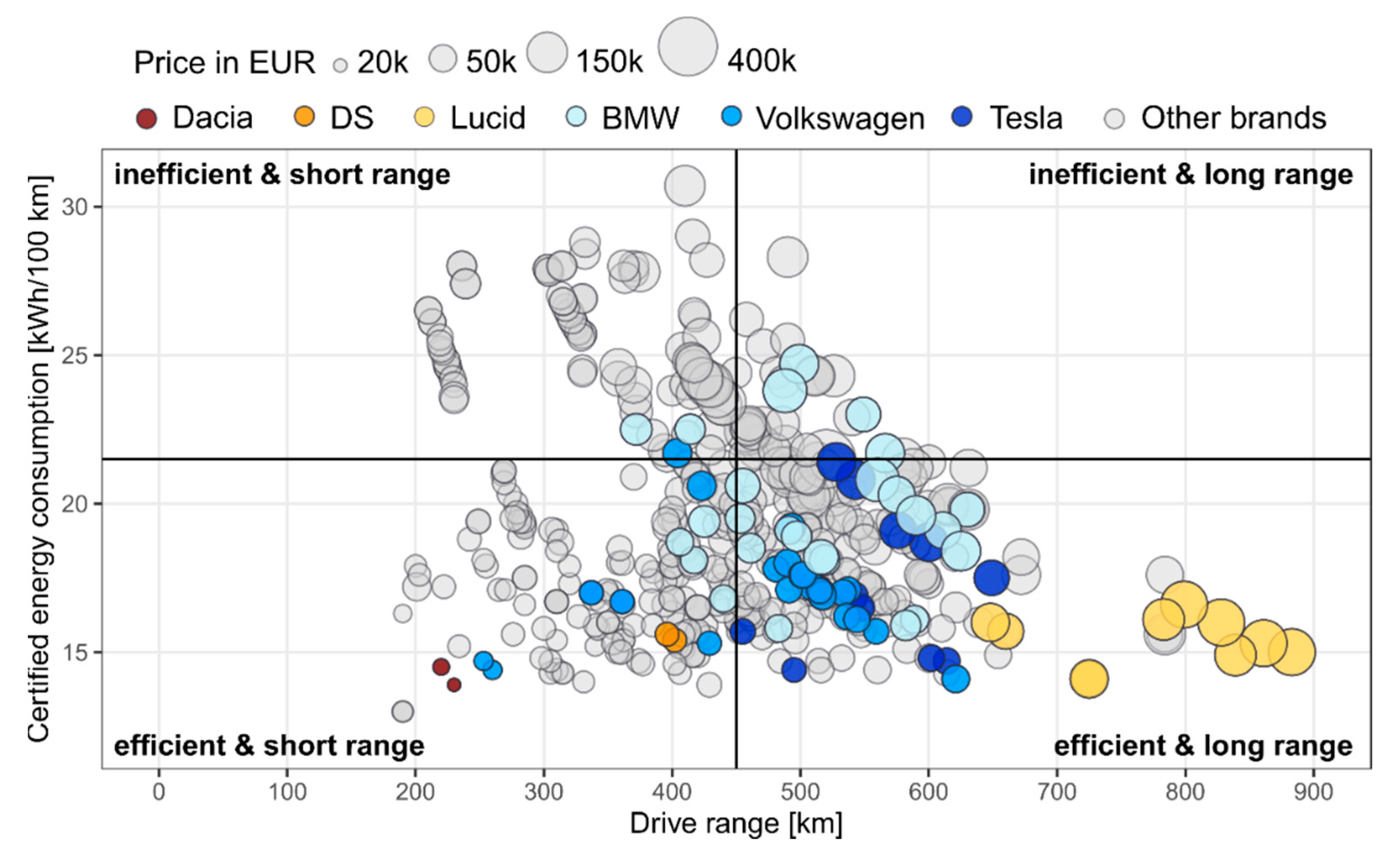

- Cheaper vehicles are more efficient (Figure 3f); vehicle prices cover a wide range and are weakly correlated with energy consumption; each 10,000 EUR in price increases certified and real-world energy consumption by some 0.3 ± 0.1 kWh/100 km (Model 1g); a doubling of vehicle price increases energy consumption by some 0.2 kWh/100 km (Model 3g).

- Each additional 10 kWh of nominal battery capacity increases certified and real-world energy consumption by 0.59 ± 0.07 kWh/100 km and 0.51 ± 0.07 kWh/100 km, respectively (Model 1e); each doubling of battery capacity increases certified and real-world energy consumption by around 20% (Model 3e; Table A2).

- Each additional 100 km drive range tends to decrease certified and real-world energy consumption by 0.85 ± 0.13 kWh/100km and 0.88 ± 0.16 kWh/100 km, respectively (Model 1f); each doubling of drive range decreases certified and real-world energy consumption by roughly 15% (Model 3f; Table A2).

3.3. Complementary Regression Analyses

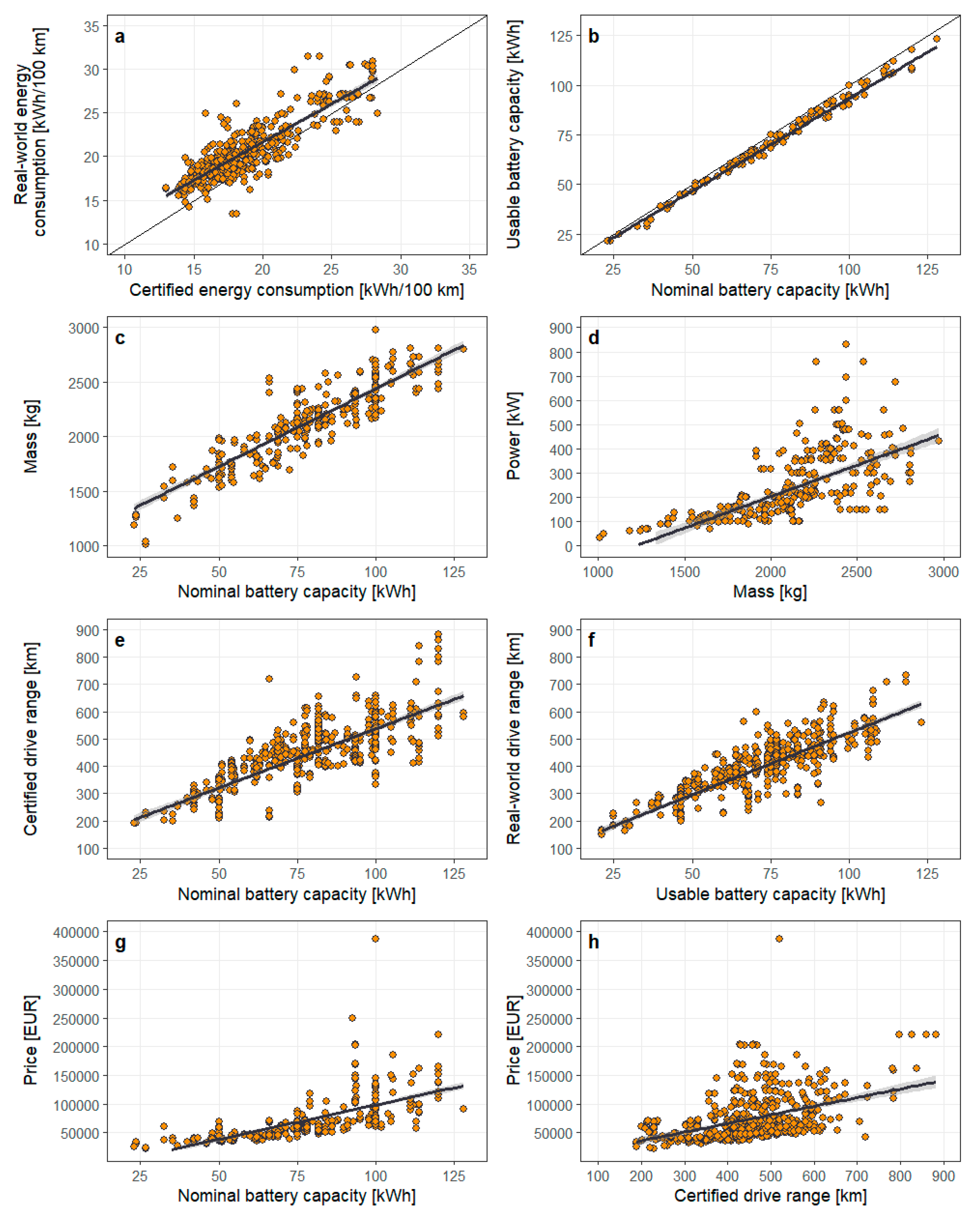

- Real-world energy consumption is significantly higher than certified energy consumption (Figure 4a); the discrepancy appears to decrease with higher consumption levels; each 1 kWh/100 km increase in certified energy consumption raises real-world energy consumption by only 0.88 ± 0.03 kwh/100 km (Model 1g).

- Usable battery capacity is on average 5 kWh below nominal battery capacity (Figure 4b); the discrepancy appears to increase for larger batteries; each 10 kWh increase in nominal battery capacity raises useable battery capacity by 9.3 ± 0.6 kWh (Model 1h).

- Each 10 kWh of nominal battery capacity increases vehicle mass by 143 ± 4 kg (Figure 4c); statistically, vehicles would weigh 1015 ± 34 kg without battery (Model 1i), suggesting that the electric battery accounts for roughly half (i.e., 1100 ± 400 kg) of the average mass of electric vehicles (2102 ± 351 kg; Table 1).

- With each 100 kg of vehicle mass, the frontal area of vehicles increases by 395 ± 36 cm2 (Model 1i) and power by 26 ± 2 kW (Figure 4d; Model 1k).

- Each 10 kWh in nominal battery capacity adds some 45 ± 2 km drive range during both certification and real-world driving (Figures 4e,f; Models 1k and 1l); each 10 kWh costs 12,000 ± 600 EUR (Figures 4e and 4f; Models 1m and 1n); a doubling in both nominal and usable battery capacity tends to increase certified and real-world drive range by nearly 80% (Models 3l and 3m).

- Vehicles with a larger battery and a longer drive range are more expensive; each 10 kWh nominal battery capacity raise vehicle price by 1,200 ± 60 EUR (Model 1n); each 10 km drive range add 1,500 ± 30 EUR to the vehicle price.

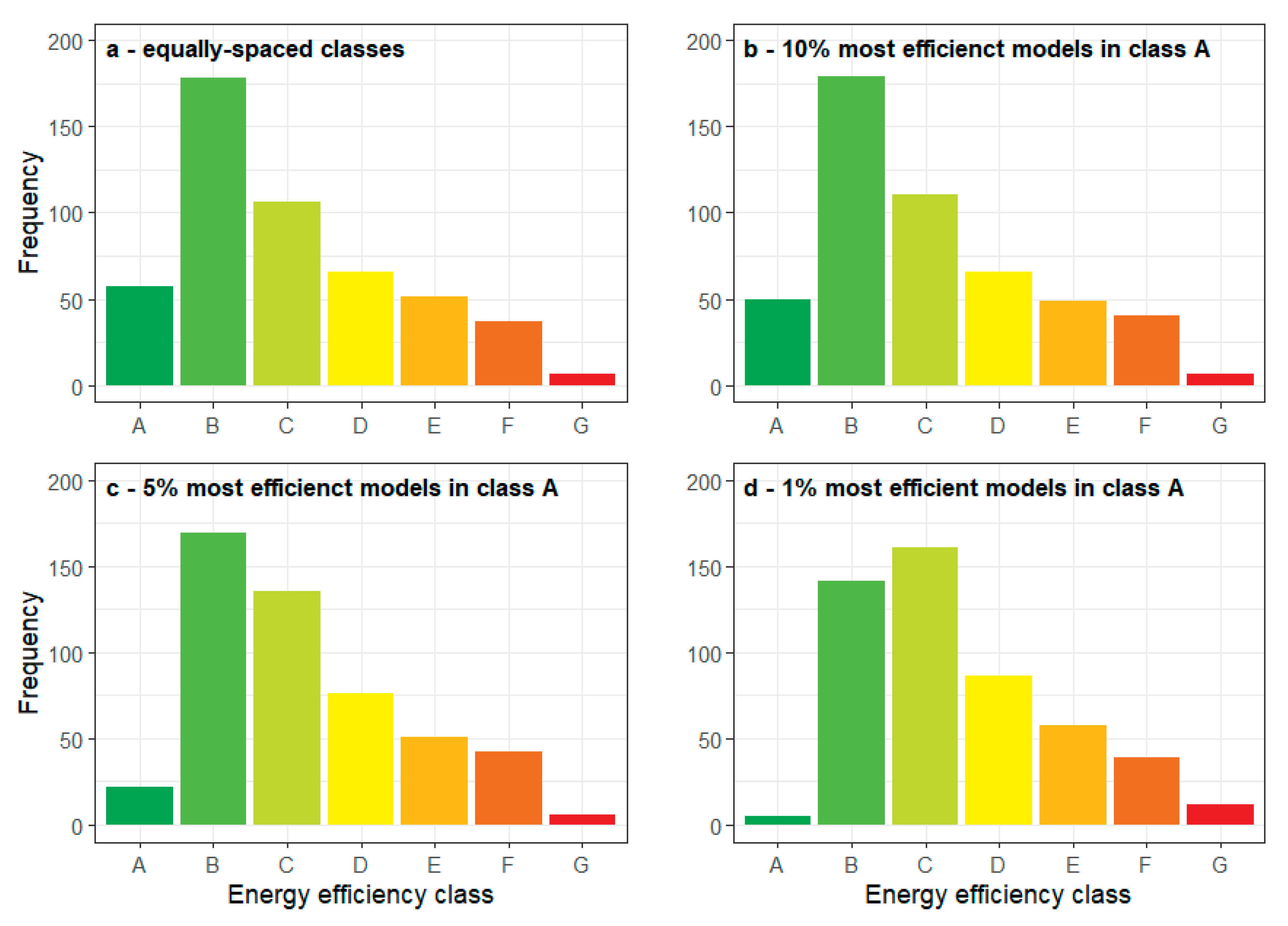

3.3. Energy Labelling of Electric Cars

- Relevant - distinguish energy efficient from less energy efficient vehicles, thereby driving innovation and supporting efficiency improvements.

- Accurate - reflect, as correctly as possible, the energy consumption experienced by consumers on the road during normal operating conditions.

- Accessible - communicate information in a clear, visible, and easily understandable manner.

- Long-lasting - remain relevant in time, by being as technologically neutral and accommodating of innovation as possible.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Research

- Timeliness: The analysis reflects the characteristics of electric cars available in Europe in 2023 and early 2024. While our results may roughly hold for the short-term future and other markets, they will become less accurate over time. Incremental innovation, technological breakthroughs, and pricing policy in a growing market will affect vehicle attributes and their trade-offs.

- Vehicle sales: We capture vehicle models available to consumers but not actual vehicle sales. Therefore, our findings characterize the electric car market but not the fleet of electric cars operated on the road. Caution should be applied when using the energy consumption data for fleet-wide energy and emissions modelling.

- Vehicle models: The boundary of what constitutes a vehicle model rather than a variant of a model is not straightforward. We consider vehicles to be individual models if they differ by name or battery capacity. This way, similar vehicles such as Citroen e-SpaceTrourer, Fiat E-Ulysses, Peugeot e-Traveller, Opel Zafira, and Toyota Proace are included as individual models in our analysis. This approach causes an overrepresentation of vehicles that are technologically identical but sold under several brands. However, we consider it practical and justifiable given the challenges associated with implementing alternative system boundaries.

- Energy consumption: Real-world energy consumption reflects actual operating conditions that drivers experience on the road. However, these conditions can vary greatly depending on, e.g., ambient temperature, driver behavior, or road profile. There can be considerable variability in the real-world energy consumption of electric cars. Furthermore, data samples of real-world consumption values in Spritmonitor (2023) are still small for most models. Overall, we consider the real-world energy consumption values to be indicative of normal operating conditions, although they may not capture any specific conditions such as very low winter temperatures.

- System boundary: We focus here on the energy consumption during the use phase of electric vehicles. Evaluating the overall energetic and environmental impacts of such vehicles requires holistic life cycle assessment and includes vehicle production and end-of-life treatment (Helmers et al., 2020).

- Methods: Regression analysis requires that the data meet certain criteria, such as normality, homogeneity and independence (Zuur et al., 2011). Regression residuals should be uncorrelated with the independent variable. The diagnostic plots in Figures S1-S41 in the Supplementary Material suggest that this requirement many not always be met and that residuals can be heteroscedastic. We address the observed heteroscedasticity, as far as feasible, by estimating heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors for all regression coefficients (Blair, 2018).

4.2. Comparison of Results

4.3. Implications for Policymakers

5. Conclusions

- A large variety of electric cars is available to consumers; models sold in Europe have an average certified and real-world energy consumption of 19 ± 4 kWh/100 km and 21 ± 4 kWh/100 km, respectively.

- There are considerable efficiency trade-offs; energy consumption is positively correlated with frontal area, vehicle mass, and battery capacity, but less so with rated power; energy consumption is negatively correlated with drive range.

- Real-world energy consumption tends to be higher than certified energy consumption; however, our data suggest that the certified energy consumption of the least efficient model variants (TEH – test energy high) may provide a good proxy for real-world energy consumption.

- The electric battery accounts for roughly half (i.e., 1100 ± 400 kg) of the vehicle mass; nominal battery capacity is on average 5 kWh higher than usable battery capacity; each 10 kWh of nominal battery capacity adds some 143 kg to vehicle mass and 45 km drive range.

- Efficient vehicles are available at any price but drive range has a cost; models with low energy consumption are available across the entire price range; however, models with a long drive range tend to be more expensive than those with a shorter drive range; this points to an important range-price trade off consumers have to make when purchasing electric vehicles.

- Increasing model variability suggests that consumers need to be informed adequately about energy consumption, energy-related costs, and trade-offs they face when purchasing an electric car. We provide empirical examples of how to categorize the energy efficiency of electric cars on a labelling scale from A to G, with and without additional utility parameters such as battery capacity or drive range.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of abbreviations and units

Appendix A

| Energy consumption | Coefficient | Value | Standard error | t value | Pr (>abs t) | p value | Adjusted R2 |

| Model 1a: energy consumption = α + β*mass | |||||||

| Certified | (Intercept)*** | 7.11 | 0.65 | 10.98 | 2.97 × 10-25 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.30 |

| Mass*** | 5.80 × 10-3 | 3.21 × 10-4 | 18.07 | 1.56 × 10-56 | |||

| Real-world | (Intercept)*** | 9.47 | 0.61 | 15.42 | 4.40 × 10-44 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.26 |

| Mass*** | 5.44 × 10-3 | 3.19 × 10-4 | 17.03 | 1.63 × 10-51 | |||

| Model 1b: energy consumption = α + β*power | |||||||

| Certified | (Intercept)*** | 18.11 | 0.37 | 48.73 | 7.69 × 10-192 | 6.41 × 10-5 | 0.04 |

| Power*** | 5.33 × 10-3 | 1.32 × 10-4 | 4.03 | 6.41 × 10-5 | |||

| Real-world | (Intercept)*** | 20.13 | 0.34 | 59.24 | 1.35 × 10-226 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| Power** | 2.70 × 10-3 | 1.19 × 10-3 | 2.27 | 2.36 × 10-2 | |||

| Model 1c: energy consumption = α + β*frontal area | |||||||

| Certified | (Intercept)*** | -4.24 | 1.23 | -3.46 | 5.87 × 10-4 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.45 |

| Frontal area*** | 9.15 | 0.47 | 19.36 | 1.05 × 10-62 | |||

| Real-world | (Intercept)*** | -5.30 | 0.99 | -5.35 | 1.38 × 10-7 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.56 |

| Frontal area*** | 10.08 | 0.38 | 26.62 | 1.65 × 10-97 | |||

| Model 1d: energy consumption = α + β*driven axles | |||||||

| Certified | (Intercept)*** | 18.75 | 2.38 × 10-1 | 78.77 | 1.20 × 10-283 | 5.90 × 10-6 | 0.04 |

| Driven axles*** | 1.45 | 3.17 × 10-1 | 4.58 | 5.90 × 10-6 | |||

| Real-world | (Intercept)*** | 20.25 | 2.28 × 10-1 | 88.68 | 1.43 × 10-305 | 1.11 × 10-4 | 0.02 |

| Driven axles*** | 1.23 | 3.15 × 10-1 | 3.90 | 1.11 × 10-4 | |||

| Model 1e: energy consumption = α + β*nominal battery capacity | |||||||

| Certified | (Intercept)*** | 14.78 | 0.57 | 25.84 | 4.65 × 10-94 | 1.50 × 10-15 | 0.12 |

| Nominal battery capacity*** | 5.94 × 10-2 | 7.21 × 10-3 | 8.243 | 1.50 × 10-15 | |||

| Real-world | (Intercept)*** | 16.94 | 0.55 | 31.04 | 3.72 × 10-118 | 2.07 × 10-12 | 0.09 |

| Nominal battery capacity*** | 5.08 × 10-2 | 7.04 × 10-3 | 7.21 | 2.07 × 10-12 | |||

| Model 1f: energy consumption = α + β*drive range | |||||||

| Certified | (Intercept)*** | 23.13 | 0.68 | 34.01 | 4.93 × 10-132 | 2.37 × 10-10 | 0.08 |

| Certified drive range*** | -8.54 × 10-3 | 1.32 × 10-3 | -6.47 | 2.37 × 10-10 | |||

| Real-world | (Intercept)*** | 24.07 | 0.72 | 33.26 | 3.72 × 10-128 | 9.48 × 10-8 | 0.06 |

| Real-world drive range*** | -8.77 × 10-3 | 1.62 × 10-3 | -5.42 | 9.49 × 10-8 | |||

| Model 1g: energy consumption = α + β*price | |||||||

| Certified | (Intercept)*** | 16.99 | 0.39 | 43.42 | 6.50 × 10-171 | 1.41 × 10-9 | 0.13 |

| Price*** | 3.29 × 10-5 | 5.33 × 10-6 | 6.17 | 1.41 × 10-9 | |||

| Real-world | (Intercept)*** | 18.98 | 0.38 | 49.71 | 9.38 × 10-194 | 4.02 × 10-6 | 0.06 |

| Price*** | 2.63 × 10-5 | 5.65 × 10-6 | 4.66 | 4.02 × 10-6 | |||

| Model 2: energy consumption = α + β*mass + β*power + β*frontal area + β*driven axles | |||||||

| Certified | (Intercept)*** | -7.96 | 1.21 | -6.59 | 1.10 × 10-10 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.55 |

| Mass*** | 2.03 × 10-3 | 5.76 × 10-4 | 3.53 | 4.60 × 10-4 | |||

| Power*** | 4.16 × 10-3 | 1.83 × 10-3 | 2.27 | 2.35 × 10-2 | |||

| Frontal area*** | 8.52 | 0.59 | 14.35 | 2.63 × 10-39 | |||

| Driven axles | 1.57 × 10-1 | 3.59 × 10-1 | 4.37 × 10-1 | 6.63 × 10-1 | |||

| Real-world | (Intercept)*** | -6.43 | 9.48 × 10-1 | -6.78 | 3.37 × 10-11 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.60 |

| Mass*** | 1.65 × 10-3 | 5.17 × 10-4 | 3.19 | 1.49 × 10-3 | |||

| Power | -1.34 × 10-3 | 1.47 × 10-3 | -9.10 × 10-1 | 3.64 × 10-1 | |||

| Frontal area*** | 9.16 | 0.50 | 18.48 | 2.74 × 10-58 | |||

| Driven axles*** | 1.02 | 3.40 × 10-1 | 3.01 | 2.74 × 10-3 | |||

| Model 3a: log(energy consumption) = α + β*log(mass) | |||||||

| log(Certified) | (Intercept)*** | -1.61 | 0.23 | -6.893 | 1.66 × 10-11 | <2.2e × 10-16 | 0.32 |

| log(Mass)*** | 5.96 × 10-1 | 3.07 × 10-2 | 19.41 | 5.80 × 10-63 | |||

| log(Real-world) | (Intercept)*** | -9.63 × 10-1 | 1.99 × 10-1 | -4.83 | 1.86e × 10-6 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.30 |

| log(Mass)*** | 5.22e × 10-1 | 2.64 × 10-2 | 19.75 | 2.12 × 10-64 | |||

| Model 3b: log(energy consumption) = α + β*log(power) | |||||||

| log(Certified) | (Intercept)*** | 2.57 | 8.47 × 10-2 | 30.35 | 2.19 × 10-115 | 5.76 × 10-6 | 0.05 |

| log(Power)*** | 7.11 × 10-2 | 1.55 × 10-2 | 4.58 | 5.76 × 10-6 | |||

| log(Real-world) | (Intercept)*** | 2.78 | 7.69 × 10-2 | 36.17 | 5.84 × 10-141 | 1.73 × 10-3 | 0.02 |

| log(Power)*** | 4.47 × 10-2 | 1.42 × 10-2 | 3.15 | 1.73 × 10-3 | |||

| Model 3c: log(energy consumption) = α + β*log(frontal area) | |||||||

| log(Certified) | (Intercept)*** | 1.83 | 5.72 × 10-2 | 32.01 | 4.60 × 10-123 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.43 |

| log(Frontal area)*** | 1.18 | 5.93 × 10-2 | 19.93 | 1.84 × 10-65 | |||

| log(Real-world) | (Intercept)*** | 1.85 | 4.19 × 10-2 | 44.21 | 8.20 × 10-174 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.57 |

| log(Frontal area)*** | 1.23 | 4.31 × 10-2 | 28.62 | 6.06 × 10-107 | |||

| Model 3d: log(energy consumption) = α + β*driven axles | |||||||

| log(Certified) | (Intercept) | 2.91 | 1.17 × 10-2 | 248.07 | 0.00 | 9.35 × 10-8 | 0.05 |

| Driven axles*** | 8.44 × 10-2 | 1.56 × 10-2 | 5.42 | 9.35 × 10-8 | |||

| log(Real-world) | (Intercept) | 2.99 | 1.06 × 10-2 | 281.06 | 0.00 | 1.90 × 10-6 | 0.04 |

| Driven axles*** | 6.83 × 10-2 | 1.42 × 10-2 | 4.82 | 1.90 × 10-6 | |||

| Model 3e: log(energy consumption) = α + β*log(nominal battery capacity) | |||||||

| log(Certified) | (Intercept)*** | 1.98 | 1.00 × 10-1 | 19.77 | 1.18 × 10-64 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.14 |

| log(Nominal battery capacity)*** | 2.24 × 10-1 | 2.33 × 10-2 | 9.63 | 3.04 × 10-20 | |||

| log(Real-world) | (Intercept)*** | 2.23 | 8.61 × 10-2 | 25.94 | 3.12 × 10-94 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.12 |

| log(Nominal battery capacity)*** | 1.84 × 10-1 | 2.01 × 10-2 | 9.17 | 1.23 × 10-18 | |||

| Model 3f: log(energy consumption) = α + β*log(drive range) | |||||||

| log(Certified) | (Intercept)*** | 3.85 | 0.20 | 19.66 | 3.86 × 10-64 | 3.34 × 10-6 | 0.05 |

| log(Certified drive range)*** | -1.50 × 10-1 | 3.18 × 10-2 | -4.70 | 3.34 × 10-6 | |||

| log(Real-world) | (Intercept)*** | 3.70 | 0.18 | 20.27 | 6.07 × 10-67 | 1.50 × 10-4 | 0.04 |

| log(Real-world drive range)*** | -1.16 × 10-1 | 3.02 × 10-2 | -3.83 | 1.46 × 10-4 | |||

| Model 3g: log(energy consumption) = α + β*log(price) | |||||||

| log(Certified) | (Intercept)*** | 7.93 × 10-1 | 1.85 × 10-1 | 4.29 | 2.18 × 10-5 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.23 |

| log(Price)*** | 1.94 × 10-1 | 1.68 × 10-2 | 11.55 | 1.69 × 10-27 | |||

| log(Real-world) | (Intercept)*** | 1.22 | 1.94 × 10-1 | 6.28 | 7.35 × 10-10 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.16 |

| log(Price)*** | 1.63 × 10-1 | 1.78 × 10-2 | 9.18 | 1.21 × 10-18 | |||

| Model 4: log(energy consumption) = α + β*log(mass) + β*log(power) + β*log(frontal area) + β*driven axles | |||||||

| log(Certified) | (Intercept) | -1.38 × 10-1 | 3.70 × 10-1 | -3.74 × 10-1 | 7.09 × 10-1 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.54 |

| log(Mass)*** | 2.43 × 10-1 | 6.51 × 10-2 | 3.73 | 2.10 × 10-4 | |||

| log(Power) | 1.29 × 10-2 | 2.37 × 10-2 | 5.45 × 10-1 | 5.86 × 10-1 | |||

| log(Frontal area)*** | 1.03 | 7.71 × 10-2 | 13.41 | 3.28 × 10-35 | |||

| Driven axles** | 3.99 × 10-2 | 1.90 × 10-2 | 2.10 | 3.59 × 10-2 | |||

| log(Real-world) | (Intercept) | 2.87 × 10-1 | 3.26 × 10-1 | 8.82 × 10-1 | 3.79 × 10-1 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.63 |

| log(Mass)*** | 2.44 × 10-1 | 6.04 × 10-2 | 4.04 | × 10-5 | |||

| log(Power)* | -5.49 × 10-2 | 1.96 × 10-2 | -2.80 | 5.38 × 10-3 | |||

| log(Frontal area)*** | 1.02 | 6.93 × 10-2 | 14.75 | 5.21 × 10-41 | |||

| Driven axles*** | 7.19 × 10-2 | 1.48 × 10-2 | 4.86 | 1.59 × 10-6 | |||

| Coefficient | Value | Standard error | t value | Pr (>abs t) | p value | Adjusted R2 | ||

| Real-world vs. Certified energy consumption | Model 1g: real-world energy consumption = α + β*certified energy consumption | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 4.11 | 4.77 × 10-1 | 8.63 | 1.44 × 10-16 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.75 | ||

| Certified energy consumption*** | 8.77 × 10-1 | 2.65 × 10-2 | 33.14 | 8.93 × 10-118 | ||||

| Usable vs. Nominal battery capacity | Model 1h: usable battery capacity = α + β*nominal battery capacity | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 6.41 × 10-2 | 4.12 × 10-1 | 1.55 × 10-1 | 8.77 × 10-1 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.99 | ||

| Nominal battery capacity*** | 9.32 × 10-1 | 6.18 × 10-3 | 150.85 | 1.56 × 10-313 | ||||

| Mass vs. Nominal battery capacity | Model 1i: mass = α + β*nominal battery capacity | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 1015 | 34 | 30 | 6.28 × 10-97 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.79 | ||

| Nominal battery capacity*** | 14.25 | 4.14 × 10-1 | 34 | 8.42 × 10-113 | ||||

| Mass vs. Frontal area | Model 1j: mass = α + β*frontal area | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 697 | 184 | 3.80 | 1.79 × 10-4 | 1.44 × 10-13 | 0.18 | ||

| Frontal area*** | 460 | 60 | 7.71 | 1.44 × 10-13 | ||||

| Power vs. Mass | Model 1k: power = α + β*mass | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | -315 | 29 | -11.05 | 1.90 × 10-1 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.43 | ||

| Mass*** | 2.59 × 10-1 | 1.52 × 10-2 | 17.10 | 9.77 × 10-48 | ||||

| Certified drive range vs. Nominal battery capacity | Model 1l: certified drive range = α + β*nominal battery capacity | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 104 | 12 | 8.90 | 8.03 × 10-18 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.59 | ||

| Nominal battery capacity*** | 4.33 | 1.61 × 10-1 | 26.91 | 1.73 × 10-102 | ||||

| Real-world drive range vs. Usable battery capacity | Model 1m: real-world drive range = α + β*usable battery capacity | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 68 | 8 | 8.37 | 6.10 × 10-16 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.71 | ||

| Usable battery capacity*** | 4.56 | 1.23 × 10-1 | 36.99 | 1.82 × 10-144 | ||||

| Price vs. nominal battery capacity | Model 1n: price = α + β*nominal battery capacity | |||||||

| (Intercept) | -21,119 | 3,981 | -5.74 | 1.45 × 10-8 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.43 | ||

| Nominal battery capacity | 1196 | 59 | 20.23 | 1.57 × 10-71 | ||||

| Price vs. Certified drive range | Model 1o: price = α + β*certified drive range | |||||||

| (Intercept) | 6,059 | 4,951 | 1.22 | 2.22 × 10-1 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.22 | ||

| Certified drive range*** | 150 | 13 | 12.02 | 1.06 × 10-29 | ||||

| log(Real-world energy consumption) vs. log(Certified energy consumption) | Model 3g: log(real-world energy consumption) = α + β*log(certified energy consumption) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 6.96 × 10-1 | 6.22 × 10-2 | 11.20 | 1.41 × 10-25 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.73 | ||

| log(Certified energy consumption)*** | 7.94 × 10-1 | 2.14 × 10-2 | 37.03 | 1.47 × 10-132 | ||||

| log(Usable battery capacity) vs. log(Nominal battery capacity) | Model 3h: log(usable battery capacity) = α + β*log(nominal battery capacity) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | -1.16 × 10-1 | 2.54 × 10-2 | -4.55 | 7.65 × 10-6 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.99 | ||

| log(Nominal battery capacity)*** | 1.01 | 5.91 × 10-3 | 170.98 | 0.00 | ||||

| log(Mass) vs. log(Nominal battery capacity) | Model 3i:log(mass) = α + β*log(nominal battery capacity) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 5.51 | 6.95 × 10-2 | 79.36 | 1.82 × 10-221 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.80 | ||

| log(Nominal battery capacity)*** | 4.96 × 10-1 | 1.58 × 10-2 | 31.41 | 1.54 × 10-102 | ||||

| log(Mass) vs. log(Frontal area) | Model 3j:log(mass) = α + β*log(frontal area) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 6.76 | 1.12 × 10-1 | 60.32 | 1.14 × 10-183 | 2.17 × 10-16 | 0.21 | ||

| log(Frontal area)*** | 7.90 × 10-1 | 9.89 × 10-2 | 7.99 | 2.17 × 10-14 | ||||

| log(Power) vs. log(Mass) | Model 3k: log(power) = α + β*log(mass) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | -13.1 | 6.89 × 10-1 | -18.97 | 3.011 × 10-55 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.54 | ||

| log(Power)*** | 2.40 | 9.13 × 10-2 | 26.29 | 6.36 × 10-84 | ||||

| log(Certified drive range) vs. log(Nominal battery capacity) | Model 3l: log(certified drive range) = α + β*log(nominal battery capacity) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 2.76 | 9.92 × 10-2 | 27.81 | 5.07 × 10-107 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.62 | ||

| log(Nominal battery capacity)*** | 7.63 × 10-1 | 2.29 × 10-2 | 33.34 | 3.09 × 10-134 | ||||

| log(Real-world drive range) vs. log(Usable battery capacity) | Model 3m: log(real-world drive range) = α + β*log(usable battery capacity) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 2.57 | 8.30 × 10-2 | 30.94 | 1.13 × 10-117 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.73 | ||

| log(Usable battery capacity)*** | 7.97 × 10-1 | 1.96 × 10-2 | 40.66 | 9.56 × 10-160 | ||||

| log(Price) vs. log(Nominal battery capacity) | Model 3n: log(price) = α + β*log(nominal battery capacity) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 6.51 | 1.68 × 10-1 | 38.80 | 4.10 × 10-174 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.59 | ||

| log(Nominal battery capacity)*** | 1.06 | 3.97 × 10-2 | 26.66 | 1.52 × 10-107 | ||||

| log(Price) vs. log(Certified drive range) | Model 3o: log(price) = α + β*log(certified drive range) | |||||||

| (Intercept)*** | 6.57 | 3.14 × 10-1 | 20.94 | 5.77 × 10-72 | <2.2 × 10-16 | 0.25 | ||

| log(Certified drive range)*** | 7.45 × 10-1 | 5.24 × 10-1 | 14.23 | 2.59 × 10-39 | ||||

| Efficiency class | |||||||||

| Criterion | Classification | Class size | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Certified energy consumption [kWh/100 km] | Equal class size over the entire data range | 2.53 | <15.5 | 15.5-18.0 | 18.1-20.6 | 20.7-23.1 | 23.2-25.6 | 25.7-28.2 | >28.2 |

| 10% vehicles in A, B-G equal class size | 2.55 | <15.4 | 15.4-18.0 | 18.1-20.5 | 20.6-23.1 | 23.2-25.6 | 25.7-28.2 | >28.2 | |

| 5% in A, B-G equal class size | 2.67 | <14.7 | 14.7-17.4 | 17.5-20.0 | 20.1-22.7 | 22.8-25.4 | 25.5-28.1 | >28.0 | |

| 1% in A, B-G equal class size | 2.78 | <14.0 | 14.0-16.8 | 16.9-19.6 | 19.7-22.3 | 22.4-25.1 | 25.2-27.9 | >27.9 | |

| Certified energy consumption per unit nominal battery capacity [10-4 km-1] | Equal class size over the entire data range | 8.34 | <20.8 | 20.8-29.1 | 29.2-37.5 | 37.6-45.8 | 45.9-54.2 | 54.3-62.5 | >62.5 |

| 10% vehicles in A, B-G equally spaced | 8.67 | <18.8 | 18.8-27.5 | 27.6-36.1 | 36.2-44.8 | 44.9-53.5 | 53.6-62.2 | >62.2 | |

| 5% in A, B-G equally spaced | 8.95 | <17.2 | 17.2-26.2 | 26.2-35.1 | 35.2-44.1 | 44.2-53.0 | 53.1-62.0 | >62.0 | |

| 1% in A, B-G equally spaced | 9.59 | <13.3 | 13.3-22.9 | 23.0-32.5 | 32.6-42.1 | 42.2-51.7 | 51.8-61.3 | >61.3 | |

| Certified energy consumption per 100 km drive range [kWh/104 km2] | Equal class size over the entire data range | 1.56 | <3.26 | 3.27-4.82 | 4.83-6.38 | 6.39-7.94 | 7.95-9.50 | 9.51-11.06 | >11.06 |

| 10% vehicles in A, B-G equally spaced | 1.61 | <2.96 | 2.97-4.57 | 4.58-6.18 | 6.19-7.79 | 7.80-9.40 | 9.41-11.01 | >11.01 | |

| 5% in A, B-G equally spaced | 1.67 | <2.62 | 2.63-4.29 | 4.30-5.96 | 5.97-7.63 | 7.64-9.29 | 9.30-10.97 | >10.97 | |

| 1% in A, B-G equally spaced | 1.78 | <1.94 | 1.94-3.72 | 3.73-5.50 | 5.51-7.28 | 7.29-9.06 | 9.07-10.84 | >10.84 | |

References

- ACEA (2024): Vehicles on European roads. ACEA - European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association. Source: https://www.acea.auto/files/ACEA-Report-Vehicles-on-European-roads-.pdf. Accessed: 27 April 2024.

- Anastasiadis, A.G., Kondylis, G.P, Polyzakisc, A., Vokas, G. (2019): Effects of increased electric vehicles into a distribution network. Energy Procedia 157: 586–593. [CrossRef]

- BEV (2023): BEV-Database. Eberhard Droege Consulting. Source: https://bev-database.de. Accessed: 5 August 2023.

- Blair, G., Cooper, J., Coppock, A., Humphreys, M., Sonnet, L., Fultz, N. (2018): Package ‘estimatr’. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Source: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/estimatr/estimatr.pdf. Accessed: 23 April 2018.

- Bowling, B. (2010): Air drag coefficients and frontal area calculation. Source: http://www.bgsoflex.com/airdragchart.html. Accessed: 30 May 2024.

- EC (1999): Directive 1999/94/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 1999 relating to the availability of consumer information on fuel economy and CO2 emissions in respect of the marketing of new passenger cars. EU – European Commission. Official Journal L012, p.16.

- EC (2007a): Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2007 on type approval of motor vehicles with respect to emissions from light passenger cars and commercial vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6). EC – European Commission. Official Journal of the European Union L171, p.1-16. Consolidated version under: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02007R0715-20200901A. Accessed: 8 January 2024.

- EC (2007b): Directive 2007/46/EC establishing a framework for the approval of motor vehicles and their trailers, and of systems, components and separate technical units intended for such vehicles. EC – European Commission. Official Journal of the European Union. L263, p. 1-160.

- EC (2017): Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1151 supplementing Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council on type-approval of motor vehicles with respect to emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6) and on access to vehicle repair and maintenance information, amending Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 and Commission Regulation (EU) No 1230/2012 and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008. EC - European Commission. Official Journal of the European Union L175, pp. 1-839.

- EC (2019): Regulation (EU) 2019/631 of 17 April 2019 stetting CO2 emission performance standards for new passenger cars and for new light commercial vehicles, and repealing Regulations (EC) No 443/2009 and (EU) No 510/2011. EC – European Commission. Official Journal of the European Union L 111, p. 13.

- EC (2020): Sustainable and smart mobility strategy – Putting European transport on track for the future. Document SWD(2020) 331 final. EC – European Commission. Source: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:5e601657-3b06-11eb-b27b-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF. Accessed: 28 April 2024.

- EC (2022): Ecodesign and energy labelling working plan 2022-2024. EC – European Commission. Official Journal of the European Union C 182, p. 1-12.

- EC (2023a): Regulation (EU) 2023/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 April 2023 amending Regulation (EU) 2019/631 as regards strengthening the CO2 emission performance standards for new passenger cars and new light commercial vehicles in line with the Union’s increased climate ambition. EC – European Commission. Official Journal of the European Union L 110, p. 5-20.

- EC (2023b): Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on energy efficiency and amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (recast). EC – European Commission. Official Journal of the European Union L 231, p. 1–111. Source: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2023_ 231_R_0001&qid=1695186598766. Accessed: 24 April 2024.

- EC (2024): Transition pathway for a green, digital, and resilient EU mobility industrial ecosystem. News article, 29 January 2024. EC – European Commission, Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Source: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/news/transition-pathway-green-digital-and-resilient-eu-mobility-industrial-ecosystem-2024-01-29_en. Accessed: 27 April 2024.

- E-CUBE (2020): 2030 peak power demand in North-West Europe. Report (Final version) – September 2020. E-CUBE Strategy Consultants and the Institute of Energy Economics at the University of Cologne gGmbH (EWI). Source: https://www.ewi.uni-koeln.de/cms/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/E-CUBE-EWI-2030-Peak-Power-Demand-in-North-West-Europe-vf3.pdf. Accessed: 28 April 2024.

- EEA (2016): Electric vehicles in Europe. Report No 20/2016. EEA - European Environmental Agency No 20/2016. [CrossRef]

- EEA (2023): New registrations of electric vehicles in Europe. EEA – European Environmental Agency. Source: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/%20new-registrations-of-electric-vehicle. Accessed: 1 February 2024.

- EVD (2023): Electric vehicle database. EV Database (9-Five-9 Ventures BV). Source: https://ev-database.org. Accessed: 5 August 2023.

- Hucho, W.-H., Sovran, G. (1993): Aerodynamics of road vehicles. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 25, pp. 485-537.

- Galvin, R. (2022): Are electric vehicles getting too big and heavy? Modelling future vehicle journeying demand on a decarbonized US electricity grid. Energy Policy 161, 112746.

- Garcia, B.B., Ferraz, B., Vidor, F.F., Gazzana, D.S., Ferraz, R.G. (2024): Chapter eleven - Power loss analysis in distribution systems considering the massive penetration of electric vehicles. Editor(s): Gali, V., Canha, L.N., Resener, M., Ferraz, B., M., Varaprasad, V.G.: Advanced Technologies in Electric Vehicles, Academic Press, 2024, Pages 279-297, ISBN 9780443189999. [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D., Lyons, M. (2022): Critical materials for the energy transition: Rare earth elements. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. Technical paper 2/2022. Source: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Irena/Files/Technical-papers/IRENA_Rare_Earth_Elements_2022.pdf?rev=6b1d592393f245f193b08eeed6512abc. Accessed: 14 June 2024.

- Haq, G., Weiss, M. (2016): CO2 labelling of passenger cars in Europe: Status, challenges, and future prospects. Energy Policy 95, pp. 324-335.

- Helmers, E., Marx, P. (2012): Electric cars: Technical characteristics and environmental impacts. Environmental Sciences Europe 24:14. [CrossRef]

- Helmers, E., Dietz, J., Weiss, M. (2020): Sensitivity analysis in the life-cycle assessment of.

- electric, vs. combustion engine cars under approximate real-world conditions. Sustainability 12, 1241. [CrossRef]

- IEA (2024): Global EV Outlook 2023: Executive summary. IEA – International Energy Agency. Source: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/executive-summary. Accessed: 27 April 2024.

- IEA (2023): Executive summary. Global EV outlook 2023. IEA – International Energy Agency. Source: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/executive-summary. Accessed: 21 March 2024.

- ICCT (2022): European vehicle market statistics – Pocketbook 2022/23. ICCT – International Council on Clean Transportation. Source: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ICCT-European-Vehicle-Market-Statistics-Pocketbook_2022_23.pdf. Accessed: 27 September 2023.

- ICCT (2023): Electric vehicles market monitor for light-duty vehicles: China, Europe, United States, and India, 2022. Source: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Major-Mkts_briefing_FINAL.pdf. Accessed: 27 September 2023.

- Knittel, C. (2011): Automobiles on steroids. Product attribute trade-offs and technological progress in the automobile sector. American Economic Review 101, pp. 3368-3399.

- Lauvergne, R., Perez, Y., Françon, M., Tejeda La Cruz, A. (2022): Integration of electric vehicles into transmission grids: A case study on generation adequacy in Europe in 2040. Applied Energy 326: 120030. doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120030.

- Madziel, M., Campisi, T. (2023): Energy consumption of electric vehicles: Analysis of selected parameters based on created database. Energies 16(3).

- Mittal, G., Garg, A., Pareek, K. (2023): A review of the technologies, challenges and policies implications of electric vehicles and their future development in India. Energy Storage e562, pp. 1-32.

- Pamidimukkala, A., Kermanshachi, S., Rosenberger, J.M., Hladik, G. (2024): Barriers and motivators to the adoption of electric vehicles: A global review. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 3(2), 100153.

- Prognos (2021): Entwicklung des Bruttostromverbrauches bis 2030. Prognos AG Berlin. Source: https://www.prognos.com/de/projekt/entwicklung-des-bruttostromverbrauches-bis-2030. Accessed: 28 April 2024.

- R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Source: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed: 25 September 2022.

- Redelbach, M., Klötzke, M., Friedrich, H.E. (2012): Impact of lightweight design on energy consumption and cost effectiveness of alternative powertrain concepts. European Electric Vehicle Congress. 19-22 November 2012. Brussels, Belgium.

- She, Z.-Y., Sun, Q., Ma, J.-J., Xie, B.C. (2017): What are the barriers to widespread adoption of battery electric vehicles? A survey of public perception in Tianjin, China. Transport Policy 56, pp. 29-40.

- Spritmonitor (2023): Spritmonitor.de – Verbrauchswerte real erfahren. Fisch und Fischl GmbH, Thyrnau, Germany. Source: https://www.spritmonitor.de/. Accessed: 31 August 2023.

- Spritmonitor (2024): Spritmonitor.de. Sparsame Elektrofahrzeuge - E-Autos mit wenig Stromverbrauch. Fisch und Fischl GmbH, Thyrnau, Germany. Source: https://www.spritmonitor.de/de/sparsame_elektrofahrzeuge.html. Accessed: 18 April 2024.

- STHDA (2018): Linear regression assumption and diagnostics in R: Essentials. STHDA – Statistical Tools for High-throughput Data Analysis. Source: http://www.sthda.com/english/articles/39-regression-model-diagnostics/161-linear-regression-assumptions-and-diagnostics-in-r-essentials/. Accessed : 1 February 2024.

- Tietge, U., Mock, P., Franco, V., Zacharof, N. (2017): From laboratory to road: Modeling the divergence between official and real-world fuel consumption and CO2 emission values in the German passenger car market for the years 2001-2014. Energy Policy 103, pp. 212-222.

- UNECE (2021): Addendum 153 – UN Regulation No. 154. Source: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/R154e.pdf. Accessed: 5 June 2024.

- Weiss, M., Zerfass, A., Helmers, E. (2019). Fully electric and plug-in hybrid cars - An analysis of learning rates, user costs, and costs for mitigating CO2 and air pollutant emissions. Journal of Cleaner Production 212: 1478-1489. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M., Cloos, K.C., Helmers, E. (2020a): Energy efficiency trade-offs in small to large electric vehicles. Environmental Sciences Europe 32.

- Weiss, M. Irrgang, L., Kiefer, A.T., Josefine R. Roth J.R., Helmers, E. (2020b): Mass- and power-related efficiency trade-offs and CO2 emissions of compact passenger cars. Journal of Cleaner Production 243: 118326. [CrossRef]

- Wiki (2024): European Union energy label. Wikipedia. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Union_energy_label. Accessed: 17 April 2024.

- Xu, J., Cai, X, Cai, S, Shao, X, Hu, C, Lu, S, Ding, S. (2023): High-energy lithium-ion batteries: Recent progress and a promising future in applications. Energy Environ. Mater. 6: 12450. [CrossRef]

- Yadlapalli, R.T., Kotapati, A., Kandipati, R., Koritala, C.S. (2022): A review of energy efficient technologies for electric vehicle applications. Journal of Energy Storage 50, 104212.

- Zhao, C., Gong, G., Yu, C., Liu, Y., Zhong, S., Song, Y., Deng, C., Zhou, A., Ye, H. (2019): Research on key factors for range and energy consumption of electric vehicles. SAE Technical Paper 2019-01-0723. [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.F., Ieno, E.N., Walker, N.J., Saveliev, A.A., Smith, G.M. (2009): Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Springer Science + Business Media. New York, USA.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).