1. Introduction

This paper begins by addressing a pervasive flaw in the current biological framework: the assumption that DNA is the sole or primary carrier of intergenerational information. In contrast, I propose that a substantial portion of this information is also transmitted through the epigenome. According to this view, the entirety of the chromosomal material inherited from parental individuals—including not only the DNA (the genome) but also its associated molecular components (the epigenome)—carries functional information across generations.

Several of the core ideas developed in this paper have been introduced in my previous work. These include: 1) the proposal that epigenetic information is transmitted independently of genetic information during meiosis; 2) the hypothesis that ageing and age-related diseases arise primarily from the loss of epigenetic information; and 3) the suggestion that many diseases not typically associated with ageing also originate from the loss of epigenetic information during the intergenerational transfer of biological information [1–4].

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI) has become a prominent topic in current research [5–14], yet the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain elusive. It is noteworthy that the concept of TEI has often been approached from a Lamarckian perspective, with many studies intentionally searching for benefits transmitted from parents to offspring [15–24]. In this paper, and previous works of mine, I propose that ageing and the inheritance of epigenetic traits are essentially interconnected, representing two sides of the same coin [1]. In other words, ageing is caused by the inheritance of two distinct codes from progenitors to offspring: the genome and the epigenome. This, and only this, is the fundamental cause of ageing [1,25]

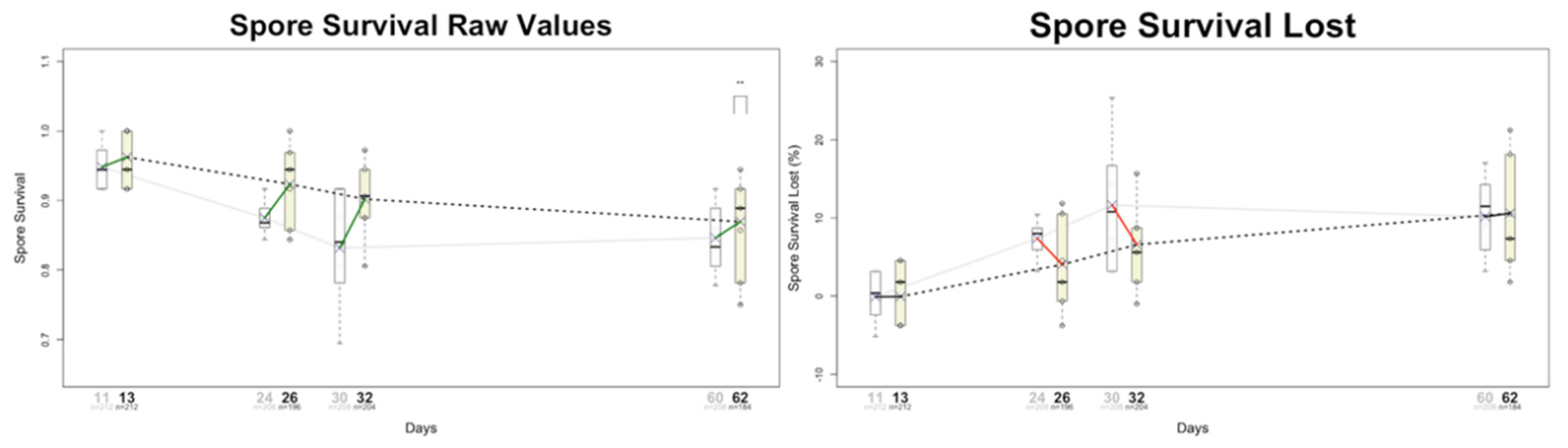

I previously introduced the concept of Epigenetic Degeneration (ED) based on serendipitous observations made while analysing spore viability following self-crosses of wild fission yeast isolates. First, I noted several indirect clues suggesting that the observed variation in spore survival could be attributed to epigenetic defects—implying that the outcomes of such crosses might reveal the presence and dynamics of epigenetically encoded traits. Based on this—and supported by numerous additional observations—I made one bold assumption: that spore survival values from self-crosses could serve as biomarkers of ageing. This alone enabled the description of ageing as a process driven purely by epigenetic factors [4]. Second, beyond the observed decline in spore survival values as the culture aged (

Figure 1), it became apparent that lost viability was not fully recovered in the F1 individuals. This indicates a progressive decline in spore survival across F1 generations, correlating with the increasing age of the parental cells from which they are derived. Notably, F1 individuals—measured ‘at birth’—exhibited spore survival values lower than those observed in the original F0 population. This suggests that F1 individuals may already display characteristics typically associated with older cells, despite their chronological youth.

In human terms, the phenomenon of ED, as described above, predicts that a sustained increase in the prevalence of certain phenotypic traits should be observable if this process is indeed occurring. According to the framework proposed in this paper, this pattern results from an increasing burden of epigenetic defects at the population level, arising from failures in epigenetic intergenerational transmission [4]. At the time of the first observation by this author of this phenomenon in 2014, some examples of sustained increases in prevalence had already been identified (see Marsellach (2017) [4] and Figures 2 and 3). Since then, more examples have been reported in the literature, to the point where denying a global trend has become increasingly difficult if not impossible.

In this paper I aim to compile as much data as possible to illustrate this global trend of increasing prevalence of various diseases or phenotypic conditions in human populations and to present these findings in a clear and systematic manner. Moreover, current public health debates often centre on single conditions. For example, in July 2025, the United States administration pledged to identify the cause of autism spectrum disorder by September of the same year. While such announcements highlight the perceived urgency of disease-specific action, they risk diverting attention from the broader epidemiological reality: many unrelated conditions have shown parallel increases over recent decades. This study examines those trends in a comparative framework.

This paper presents a focused articulation of ideas originally developed within a broader theoretical framework. The complete model—including a detailed formalisation of a newly proposed hypothesis to explain ageing, together with its wider biomedical and societal implications—has been published as a preprint on Zenodo [1]. A standalone paper addressing solely the proposed model of ageing has also been made available [25]. In the present work, I focus specifically on the epidemiological evidence supporting population-wide trends in disease prevalence and their potential connection to epigenetic degeneration. Additional concepts and extensions beyond those discussed in these two papers, as introduced in the original preprint, will be developed and disseminated in future publications by this author.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Global Trend Lines Determination

Academic papers were searched using various platforms, including Google Scholar, ResearchGate, PubMed, general Google searches, and references from papers citing those already collected. These papers were screened for the presence of prevalence trends. Searches included phrases such as “******* prevalence trend” or “******* increased prevalence,” where “*******” represents any of the phenotypic traits analysed. The prevalence trends obtained are listed in Supplementary Table 1, and the corresponding citations are provided in the References for Supplementary Table 1 file.

To summarise the trend lines for a given phenotypic trait, a Mean Annual Variation (MAV) was calculated yearly by pooling all available data for each year covered by the trends found in the literature and averaging it.

For trends spanning multiple years, the contribution for each year (Annual Variation, AV) was calculated using the following formula:

(See Supplemental

Figure 1 for more details.)

Next, for every year covered by the collected trends, an Accumulated Mean Annual Variation (AMAV) was calculated yearly using the formula:

AMAV lines were constructed using all the annual AMAV values. These lines exhibit an increasing trend if there is a sustained rise in the prevalence of a given trait or a decreasing trend if there is an accumulated reduction in prevalence. In Supplemental Figure 2 through 33, the AMAV lines for each phenotypic trait analysed are plotted alongside the trends used to create them.

Given the heterogeneity of the populations and study methodologies, AMAV should be interpreted as an exploratory synthesis designed to highlight broad temporal patterns, rather than as a precise pooled prevalence estimate for any single population.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evidence of Population-Based Epigenetic Degeneration in Human Populations

Two striking epidemiological trends are becoming increasingly evident in human populations. First, there is a broad rise in the prevalence of numerous diseases and phenotypic conditions. Second, conditions once considered characteristic of older age are now appearing with greater frequency in younger individuals. In the following sections, I present a wide range of examples illustrating these patterns. For the purposes of the discussion that follows, I have classified the listed diseases and conditions into two categories. The first group comprises diseases associated with defects, impairments, or dysfunctions affecting the body’s physical systems, organs, or tissues—typically arising from molecular, cellular, or structural abnormalities. I refer to this group as somatic diseases. The second group consists of mental health disorders, defined as conditions resulting from dysfunctions in neural circuits and processes that affect cognition, emotion, perception, and behaviour. These disorders generally arise from disruptions in neuronal signalling, synaptic plasticity, or the regulation of network-level activity within the central nervous system.

3.1.1. Examples of Epigenetic Degeneration in Human Populations: Somatic Diseases

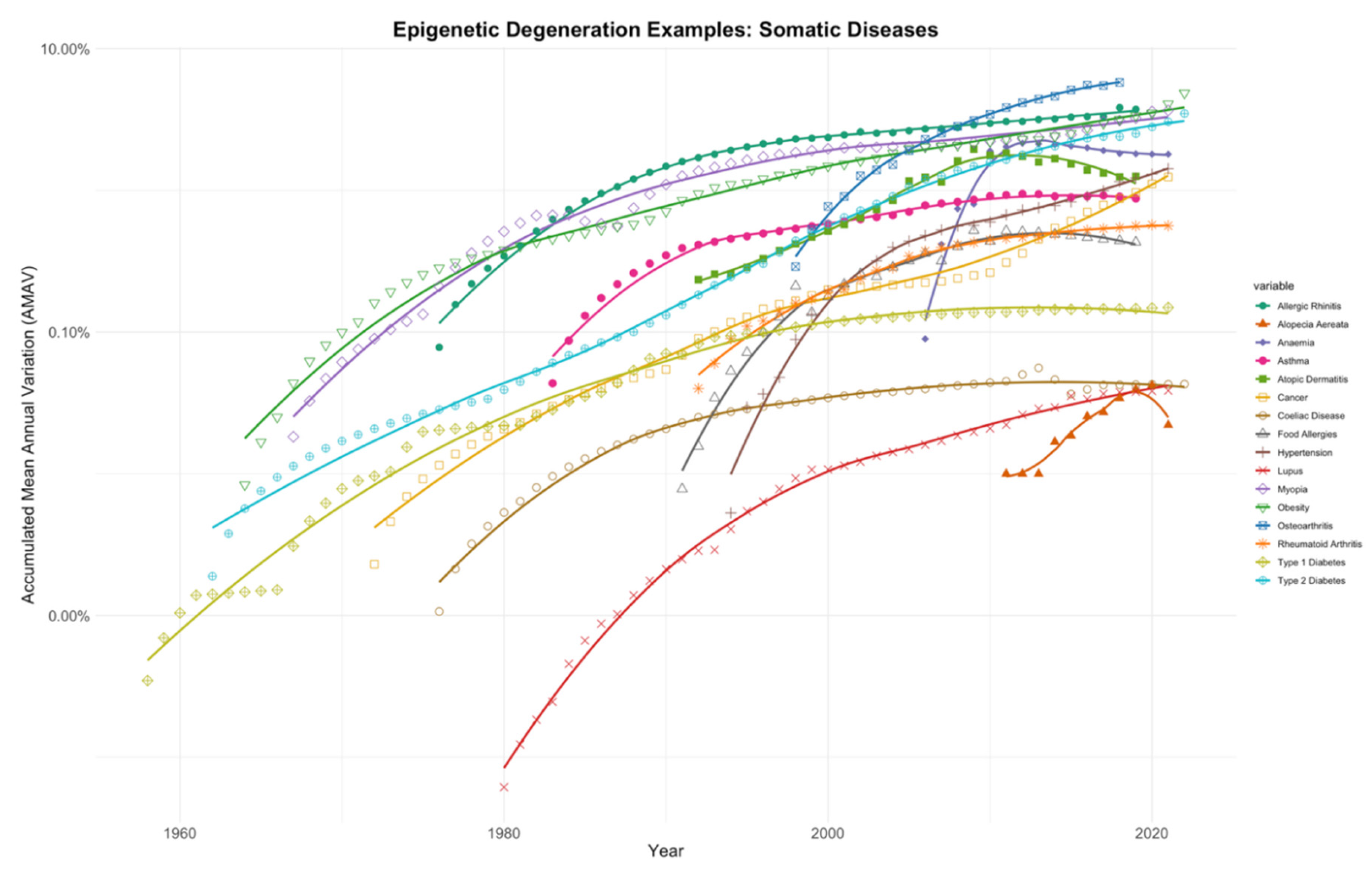

In

Figure 2, sixteen phenotypic conditions classified as diseases, for which an exhaustive search for prevalence trends was conducted in the literature, are plotted. To summarise all the trend lines, an Accumulated Mean Annual Variation (AMAV) line was calculated annually for each condition (see Materials and Methods). The sixteen AMAV lines clearly show a sustained increase in prevalence in recent years.

The list of diseases shown in this section consists of seemingly unrelated conditions. A large group of them, however, are related to immune processes: either autoimmune diseases such as alopecia areata, some types of anaemia, coeliac disease, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and type 1 diabetes; or simply immunological conditions like allergic rhinitis, asthma, atopic dermatitis, and food allergies. The rest appear to have no relation to the immune system: most forms of anaemia, cancers, myopia, obesity, osteoarthritis, and type 2 diabetes.

For all of the diseases included in

Figure 2 there is not only the observation of increased prevalence, but evidence that these diseases are increasingly being diagnosed at younger ages, suggesting a tendency towards early onset [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

This section aims to show that seemingly unrelated diseases and conditions share a common pattern. This is not a new observation, as several studies have identified a global increasing trend in many diseases [

42,

43,

44,

45].

3.1.2. Examples of Epigenetic Degeneration: Mental Health Issues

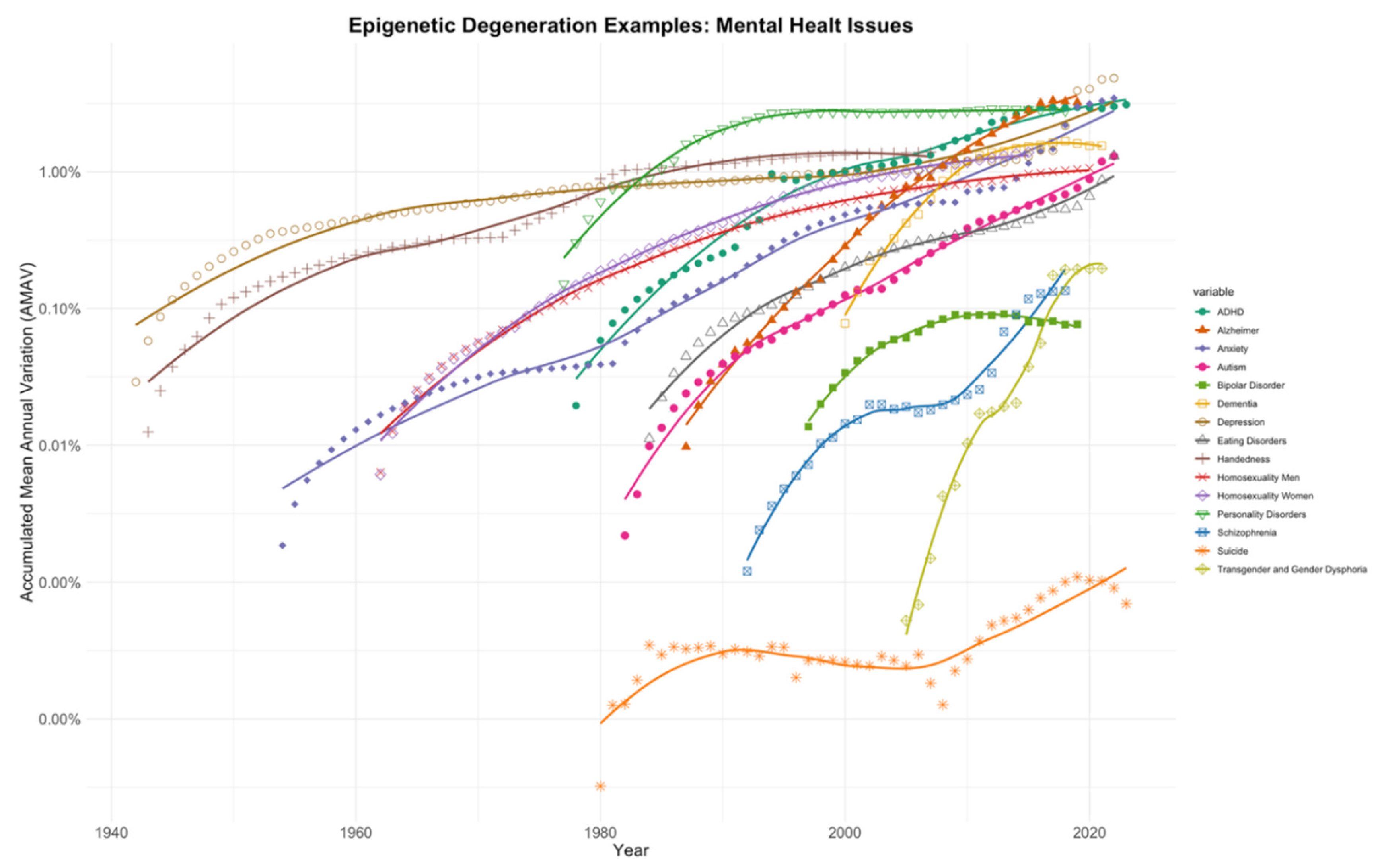

Similar to

Figure 2, in

Figure 3, AMAV lines were calculated from prevalence trends of fifteen diseases or phenotypic conditions affecting human neuronal functions. Once again, all these AMAV lines show a clear and sustained increase in the prevalence of these conditions. Moreover, as in the examples presented in the previous section, many of these conditions are increasingly being diagnosed at younger ages [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56].

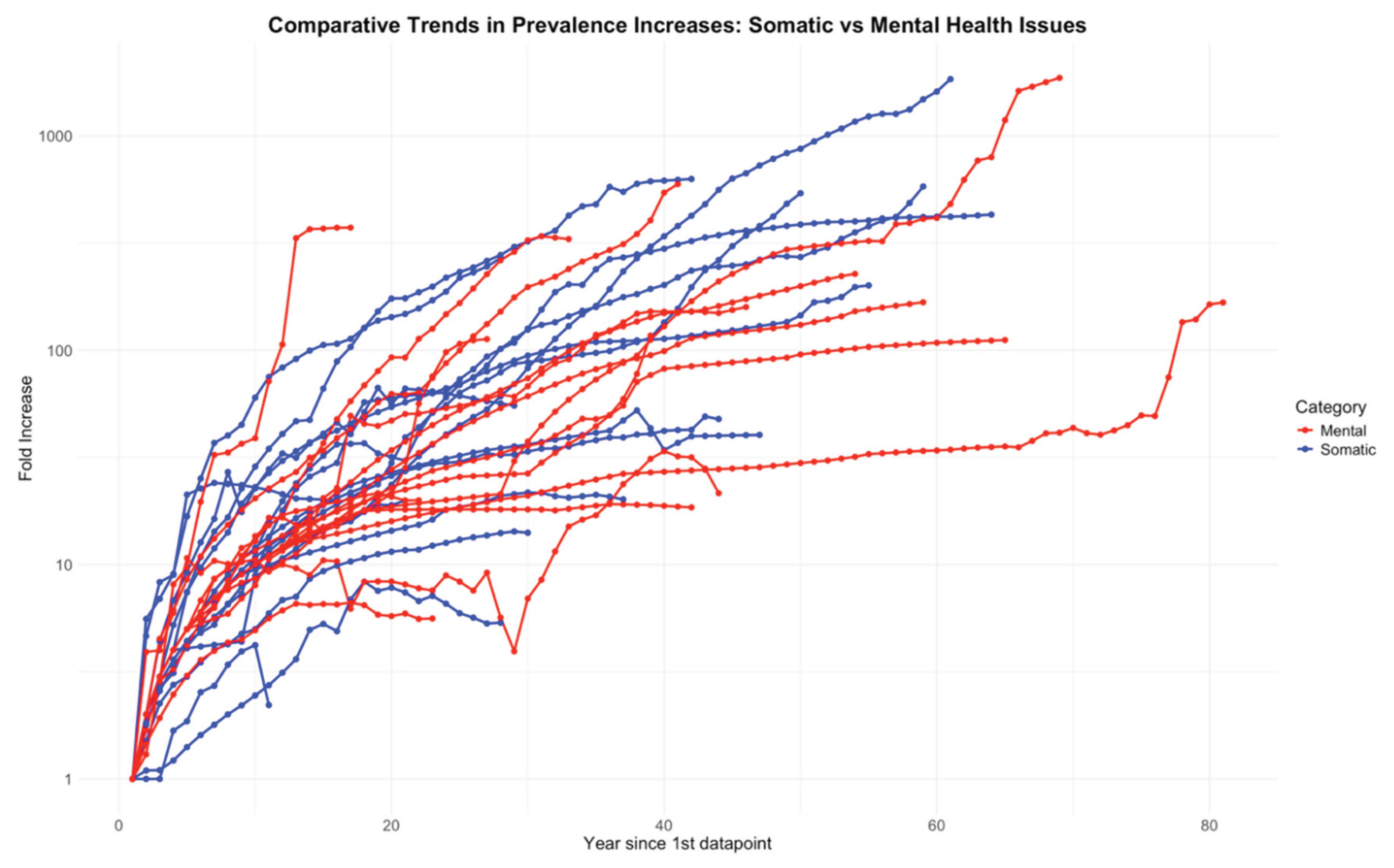

This section presents empirical evidence showing that, counterintuitively, somatic and mental health issues display a high degree of similarity in their epidemiological patterns. To assess whether this is indeed the case,

Figure 4 compares the fold increase in both somatic and mental health conditions, using as a baseline the first year for which data were available. To evaluate whether the trend lines for the two groups differed, an Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was performed. The analysis did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the groups (p = 0.341).

Under conventional biomedical models, somatic and mental health disorders are generally regarded as having distinct causes, mechanisms, and risk factors. Consequently, there is no a priori reason to expect them to exhibit similar epidemiological trends. Yet, as demonstrated in this work, both groups display strikingly parallel patterns—particularly in their rising prevalence and earlier onset—an observation that strongly suggests the need for a unifying explanatory framework.

In summary, this section demonstrates that many mental health disorders follow the same population-wide trends of increasing prevalence and earlier onset previously described for somatic conditions.

3.2. The Comorbidities Snowball and the Ladder Effect

In this section, I introduce two categorical descriptors to capture recurring patterns observed across a wide range of epidemiological studies, as systematically reviewed in this work. These descriptors aim to characterise scenarios in which the phenomena described above become increasingly complex—presumably as the cumulative burden of epigenetic defects grows within the population.

Before presenting the ideas I introduce in this section, I should briefly describe a key impression from my work with yeast self-crosses: meiosis appeared to improve spore survival, but recovery was more limited when the underlying defects were more severe. This pointed to the existence of a saturable epigenetic repair mechanism during meiosis [

4], in which excess defects likely exceed the system’s capacity and are transmitted to subsequent generations. Over time, this would not only increase the prevalence of individual defects but also lead to the accumulation of multiple defects within the same organism. In human populations this phenomenon is called comorbidities or multimorbidities.

3.2.1. The Comorbidities Snowball

The literature provides strong evidence for an increasing prevalence of multimorbidity [

57,

58,

59], affecting somatic conditions, mental health disorders, or a combination of both [

57,

60]. Furthermore, when reviewing studies that report rising prevalence for specific diseases, it is common to encounter references to comorbidities associated with those conditions. These include somatic–somatic comorbidities [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65], mental–mental comorbidities [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78], and somatic–mental comorbidities [

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89]. Taken together, these observations—along with the shared patterns illustrated in

Figure 4—further support the view that somatic and mental health disorders exhibit common trends in fundamental epidemiological data. Based on the assumption that these patterns arise from a unified mechanism—namely, the cumulative increase in the prevalence of multiple diseases driven by the intergenerational accumulation of epigenetic defects—I propose to name this phenomenon the Comorbidities Snowball (CS). This term metaphorically captures the compounding nature of epigenetic defect accumulation—intensifying over time like a snowball rolling downhill.

3.2.2. The Ladder Effect

Another notable pattern that emerges from a systematic review of the literature on disease prevalence is a corresponding progressive increase in disease severity. This trend is consistently observed across both somatic and mental health conditions. Specific examples include hypertension [

34,

90], borderline personality disorder [

91], generalised anxiety disorder [

92], eating disorders [

93,

94], anaemia [

95], diabetes [

96], psychopathy [

97,

98], and obesity [

99], among others. Based on the same assumption outlined above, I propose naming this phenomenon the Ladder Effect (LE), as it metaphorically captures how the accumulation of epigenetic defects may drive a stepwise progression in disease severity over time.

4. Discussion

This paper presents extensive empirical evidence—drawn from publications by other researchers—of at least two overwhelmingly prevalent shared patterns across many otherwise unrelated diseases in modern human populations. While the presence of such similar patterns is not, in itself, sufficient to confirm the existence of a common underlying mechanism, it does justify proposing this possibility as a working hypothesis—one that merits serious consideration and targeted experimental investigation.

Although the rise in prevalence for some diseases—particularly among young people—is now being reported repeatedly in mainstream media across a wide range of conditions, this trend has not yet become a clear focus of sustained scientific research. Reports have covered global diabetes trends [

100], youth prediabetes [

101], childhood obesity [

102], mental health disorders in young people [

103], and overall declines in children’s health [

104], to name just a few. In some cases, the evidence has become so overwhelming that some authorities have reframed specific conditions—such as autism—as national public health priorities, given their strikingly high prevalence [

105]. However, the approaches taken in such cases may be far removed from rigorous scientific frameworks [

106,

107].

Nevertheless, the dominant approach in current research remains focused on condition-specific explanations or, in many cases, on downplaying the phenomenon altogether. Increases in disease prevalence are often attributed to factors such as heightened awareness or improved diagnostic capabilities. In my view, the persistence of this stance—and, in some instances, outright dismissal—is largely due to the absence of a coherent mechanism capable of explaining these patterns within the boundaries of the prevailing scientific framework.

The proposal to consider intergenerational epigenetic information transfer as a central component of biological information transmission allows for a broader conceptualisation—one that links ageing, as a phenomenon rooted in the loss of biological information, with the mechanism proposed in this paper: Epigenetic Degeneration (ED) [

1,

4]. In this framework, ED arises from the progressive, population-wide accumulation of epigenetic defects, acting both as a driver and as a secondary consequence of ageing [

1]. This perspective provides a unifying mechanism capable of accounting for the empirical patterns described throughout this paper.

4.1. Different Explanations, One Common Root

Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the rise of different groups of diseases—including, among others, environmental changes [

108], the hygiene hypothesis [

109,

110], lifestyle and behavioural changes [

111], gut microbiota dysbiosis [

112], epigenetic modifications [

113], and evolutionary mismatch [

114]—yet the prevailing approach remains, at best, to consider and investigate each disease in isolation.

In contrast to this approach, I argue for considering a broader and more fundamental phenomenon as the root cause of the increased prevalence of these diseases: Epigenetic Degeneration (ED), arising from the progressive accumulation of epigenetic defects at the population level.

The proposal that epigenetic defects can be transmitted intergenerationally and serve as the source of many diseases is not new, with previous studies led by Michael Skinner and other independent groups advancing similar ideas. Early work from Skinner’s group showed that brief exposures during fetal gonadal sex determination can reprogramme the germ line; in rats, anti-androgenic or estrogenic disruptors produced reduced spermatogenic capacity and male infertility that persisted via the paternal line to F3–F4, correlating with altered sperm DNA methylation [

115]. Follow-up work reported that most toxicant-induced transgenerational sperm DMRs escape the canonical DNA-methylation ‘erasure’ during early embryogenesis—behaving like imprint-like regions—and that low-CpG-density (‘desert’) sites often gain methylation in morula embryos, suggesting a more dynamic reprogramming landscape than previously thought [

116]. Similarly, despite the widespread belief that most epigenetic marks are erased during gametogenesis and embryogenesis, a recent report by Izpisua-Belmonte and colleagues demonstrated that some marks can persist [

8] even after being subjected to the two well-known waves of epigenetic reprogramming that occur during gametic and embryonic stages [

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123]. Beyond these approaches, the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) literature independently demonstrates that early-life environments shape later disease risk [

124]. Human natural experiments, such as the Dutch Hunger Winter, have linked prenatal famine to persistent IGF2 methylation differences decades later [

125]. Observational studies in humans further suggest intergenerational signals following severe trauma—such as FKBP5 methylation in the offspring of Holocaust survivors [

126]—and in respiratory epidemiology, where grandmaternal smoking and parental prepubertal or adolescent smoking are associated with an increased asthma risk in descendants [

127]. However, these approaches generally offer only case-by-case evidence or do not frame the phenomenon within a broader context, as is done in this manuscript and in other works by this author, which interpret it as a side effect of the ageing process itself [

1,

4].

4.2. The Common Root’s Uncomfortable Implication

If Epigenetic Degeneration is indeed the shared origin of these diverse conditions, then its consequences are unlikely to be confined to somatic health alone, as illustrated by the parallels in

Figure 4 between somatic and mental health conditions. By virtue of its systemic and intergenerational nature, the same process may extend to aspects of human biology that many would prefer to believe are entirely free from such constraints.

The model proposed in this paper suggests that many defects arise from the inaccurate intergenerational transfer of epigenetic information from parents to their descendants. The implication is straightforward: the impaired functioning of affected individuals stems from the absence of essential biological information that should have been inherited as part of the complete set of information transmitted from their parents.

In explaining somatic issues, this model presents no particular difficulty. For example, it can readily account for the increased prevalence of autoimmune diseases—such as type 1 diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis—or other immune-related conditions, such as atopic dermatitis or food allergies, through defects in the mechanism of immune tolerance. Immune tolerance is a critical process in the immune system that prevents the body from attacking its own tissues while enabling coexistence with non-harmful foreign substances. Antigens are randomly generated in immune cells through the process of V(D)J recombination [

128], which is responsible for the vast diversity of antibodies produced. Immune tolerance encompasses several mechanisms that ensure the immune system can distinguish between self and non-self antigens, thereby preventing both autoimmunity and excessive immune responses to harmless foreign substances. This interpretation implies that organisms must possess

a priori information about: 1) their own components that could otherwise trigger an immune response; and 2) non-harmful foreign substances capable of generating an immune response but which, through evolutionary selection, have been labelled as harmless. A concrete example is the widespread ability to consume cow’s milk: most individuals recognise its immunogenic components as non-harmful, whereas those with cow’s milk allergy have lost the

a priori information required to tolerate it. As such, this tolerance must be encoded in our biological information and shaped by evolutionary selection.

Although, in principle, information on multiple biological processes could be transmitted intergenerationally via the epigenome, for some of the diseases examined in this study that are not clearly autoimmune, there have been proposals implicating autoimmunity as part of their aetiology—for example, in obesity [

129], myopia [

130], and osteoarthritis [

131]. While such scenarios merit serious consideration, careful studies are required, as the phenomenon of CS could also contribute to these observations (see below).

The truly uncomfortable implications arise when mental health issues are analysed using the same reasoning. This introduces a challenging assumption for our highly teleologically biased societies: human neuronal functions are, at least in part, pre-written in the biological information we inherit. Given the nature of the diseases or conditions under study, this implies that these functions encompass not only simple tasks but also those we associate with free will—thereby diminishing our perceived degree of autonomy. This is, indeed, uncomfortable.

A particularly clear example of discomfort arises when considering brain functions central to our lifestyles, such as sexual orientation or gender identity. Accepting that these aspects are 1) pre-written, and 2) that some individuals exhibit phenotypic variability which is not only unrelated to free will or part of natural variability, but may also stem from a defective biological process, presents a profound challenge. It is worth remembering that the classification of something as a ‘disease’ is ultimately an arbitrary decision. The term carries significant social and psychological implications, and understandably, no one wishes to be labelled as ill, as this is often perceived negatively. However, preconceived ideas and societal sensitivities must not be allowed to hinder our ability to objectively investigate the physiological mechanisms underlying traits observed in human and animal populations. Biologists are compelled to provide explanations for empirical observations. A major point of contention in research on same-sex sexual behaviour (SSB) is how a trait that appears to reduce reproductive fitness—since individuals engaging exclusively in same-sex relationships would, in theory, pass on fewer genes—has been maintained throughout evolutionary history. Within the current genetic paradigm (purely Darwinian and based on DNA as the sole source of intergenerational information), this presents a paradox. A more detailed discussion of this topic will be provided later in the discussion, after the concept of CS has been examined in more detail and the Principle of Pre-Determined Post-Processing has been introduced (see below).

From another perspective, for mental health conditions unequivocally recognised as diseases—given the genuine suffering they cause—acknowledging that they stem from a ‘faulty biological code’ could help reduce the guilt and stigma often associated with them. This, in turn, could contribute to mitigating one of the greatest challenges currently facing the field of mental health.

4.3. The Comorbidities Snowball Nature of Multimorbidity

The predominant approach to understanding comorbidities or multimorbidities focuses on identifying individual explanations for each condition, rather than seeking a unifying mechanism that could account for them collectively. The underlying assumption is that the presence of one disease increases the likelihood of developing others, either due to the nature of the initial condition or as a consequence of its treatment. As noted earlier, several unifying mechanisms have been proposed to explain the concurrent rise in individual diseases or comorbidities—such as systemic chronic inflammation (‘inflammageing’) [

132,

133,

134], the impact of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and metabolic disruption [

135,

136,

137], loss of early-life microbial exposure (‘hygiene/microbiome hypothesis’) [

138,

139], exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals [

140,

141], or climate change–driven pathogen shifts [

142], among others. However, none of these frameworks incorporate the flaw described in this paper as a central component of their explanation. Observations in fission yeast (e.g.,

Figure 1), coupled with the key impression that recovery during meiosis was more limited when the underlying defects were more severe, led me to propose that these diseases may share a common origin—namely, intergenerational defects in epigenetic information transmission [

4]. This perspective provides a novel framework for explaining multimorbidity.

I propose that the true commonality among these diseases lies in their origin: the inaccurate intergenerational transmission of epigenetic information. This flawed inheritance process progressively increases the burden of epigenetic defects within the population. Over successive generations, this accumulation not only drives the rising prevalence of many individual diseases but also contributes to the simultaneous occurrence of multiple conditions in the same individual.

Current approaches to identifying the molecular causes of comorbidities or multimorbidities are fundamentally limited. They focus exclusively on genome-level defects, overlooking intergenerational epigenetic information transfer. Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and Mendelian Randomisation (MR) [

143] dominate the field, operating under three assumptions: 1) no epigenetic information is inherited from parents; 2) all epigenetic marks are re-established solely from the genome; and 3) genetic markers alone explain causal relationships. This paper challenges these assumptions, proposing instead that: 1) epigenetic information, including defective epialleles, may be inherited; 2) observed associations may arise from a genetic marker’s proximity to an epigenomic marker; and 3) genetic–phenotypic links may thus be confounded.

4.4. The Principle of Pre-Determined Post-Processing

This manuscript proposes that certain human neuronal traits are pre-written, as suggested by observable patterns at population level. In neuroscience, the term ‘innate circuits’ refers to neural pathways that are largely pre-wired by genetic programs and do not require extensive learning or experience to develop their fundamental structure or function. Therefore, the idea of pre-written information is not entirely foreign to modern neuroscience, which acknowledges that certain aspects of the nervous system are inherently innate or genetically programmed. The prevailing scientific consensus is that while many neuronal connections are initially wired by genetic instructions, the brain remains highly plastic, allowing it to be shaped by environmental influences, learning, and lived experiences. Modern neuroscience recognises a balance between genetically guided development and experience-dependent modifications, refuting extreme models that view humans as either complete blank slates (tabula rasa) or as entirely pre-determined by genetics. Distinguishing between strictly innate versus learned neuronal patterns remains an open question, but we do have some clues derived from twin studies, developmental neuroscience, and molecular genetics. However, these approaches have yet to establish a clear and concise pattern for complex human neuronal abilities. So far, we have identified innate components in basic neural processes, such as reflexes and certain aspects of language acquisition, but the extent to which more complex cognitive and behavioural traits are pre-written remains largely unexplored.

For well-recognised diseases such as Alzheimer’s, autism, depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia, the ideas proposed in this manuscript may not face significant opposition. However, when applied to more debated traits, such as Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), eating disorders, handedness, homosexuality, personality disorders, or transgenderism, discussions are likely to be more contested. Many experts argue that the observed increases in, for example, homosexuality (for both men and women) or in non-right-handedness (left-handedness or ambidexterity) are primarily due to changes in social acceptance, recognition, and self-reporting, rather than reflecting a sudden biological shift. I argue that this explanation is based on a flawed assumption, namely, the idea that DNA alone is responsible for the transmission of biological traits. Traits solely determined by DNA struggle to explain the rapid increases observed in these characteristics. However, when intergenerational epigenetic inheritance is considered, such increases become biologically plausible. Epigenetic changes occur at much higher frequency than genetic mutations and can contribute to rapid phenotypic variation and adaptation [

4,

5].

The ED phenomenon described in detail in this manuscript offers a new tool to distinguish between innate and learned processes, although the nature of the patterns observed is controversial and may provoke further debate. The directionality inherent in ED provides an evolutionary perspective for identifying traits that are biologically selected against. By proposing that ED results from the faulty inheritance of epigenetically transmitted parental information, it follows that traits whose prevalence increases under biological or cultural conditions favouring ED are, by definition, traits that were selected against in contexts where ED was not favoured [

1]. The full framework outlined in this paper allows for an unbiased distinction between two scenarios: an increase in ‘cultural-like’ behaviours driven by social learning and greater acceptance, and an increase driven purely by biological factors. The key lies in multimorbidity.

The biological and cultural conditions that favour ED are beyond the scope of this paper and have been addressed by this author in the previously mentioned preprint posted on Zenodo, which presents the full model [

1], including a new way to understand what ageing is at is fundamental level [

25].

4.4.1. Multimorbidity: The Signature of Inheritance

A common argument for a ‘social acceptance hypothesis’ is that as societal pressures lessen, more people openly express their sexual orientation or refrain from switching from left to right-handedness, leading to increased prevalence. While this reasoning may seem valid, it overlooks two key caveats drawn from the observations presented in this paper: 1) why do other clearly recognised diseases, such as cancer, coeliac disease, or lupus, exhibit strikingly similar patterns of increasing prevalence? If social acceptance alone were responsible for the rise in certain traits, we would not expect to see comparable trends in biological diseases that carry no cultural stigma. The fact that these conditions—which have no connection to self-reporting or societal pressure—demonstrate the same type of increasing prevalence suggests a common underlying biological mechanism. This aligns with the framework proposed in this manuscript, in which ED serves as the primary driver of rising disease prevalence across multiple, seemingly unrelated conditions; and 2) why are these debated traits increasingly being observed as comorbid or multimorbid with other diseases or conditions? If social acceptance alone accounted for the rise in traits such as homosexuality or left-handedness, we would not expect them to show increased multimorbidity with conditions like autism, ADHD, anxiety, or immune disorders. Yet, empirical evidence suggests that such comorbidities do exist [

144,

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153,

154,

155,

156,

157,

158,

159]. Again, ED and its consequences—The CS—provide a clear biological explanation for these observations. Thus, rather than attributing these trends solely to cultural and societal shifts, this manuscript presents a unifying biological framework that accounts for both the rising prevalence and comorbid or multimorbid patterns observed across multiple conditions, suggesting that epigenetic inheritance plays a key role in shaping these traits.

4.4.2. Beyond the Principle of Labelled Lines

The ED phenomenon offers an evolutionary lens through which rising trends in both diseases and behavioural traits can be reinterpreted, providing a biological foundation for characteristics that have traditionally been attributed solely to social and environmental influences. The reasoning developed in this manuscript ultimately suggests that, in addition to the well-established ‘principle of labelled lines’—which posits that sensory inputs are transmitted along specific neural pathways—other human neuronal abilities, including certain complex cognitive functions, may also be governed by ‘pre-written’ circuits. These circuits predispose individuals to specific response tendencies when exposed to particular stimuli. This concept could be described as a ‘principle of pre-determined post-processing’. When this principle extends to processes that we typically perceive as freely chosen—such as sexual orientation—it is understandable that we are reluctant to accept the possibility that these traits and behaviours might be biologically pre-determined rather than resulting from conscious choice or purely environmental influences.

4.5. Evolutionary Consideration

The flaw described in this paper assigns excessive importance to DNA in the manifestation of traits. By treating DNA as the sole bearer of intergenerational biological information, current biological frameworks are compelled to seek genetic explanations for all phenotypic observations—including those that contradict a strictly Darwinian interpretation. This includes the persistence of traits that exist at generally low frequencies within populations and, according to Darwinian logic, should be selected against. To account for this paradox, indirect mechanisms are often proposed to explain how such traits are maintained despite negative selection pressure. In contrast, the framework presented in this manuscript—through the introduction of the ED phenomenon—allows these observations to be explained without resorting to such indirect reasoning. ED functions as a continuous generator of phenotypes that are difficult to reconcile with traditional models, allowing them to persist at low frequencies in wild populations, or at levels that do not compromise the intergenerational transmission of biological information.

A clear example of this is SSB as previously mentioned. Under the current genetic paradigm, this presents a paradox. However, the framework proposed in this manuscript provides a novel solution: 1) the trait is not encoded in the genome but rather in the epigenome, meaning it does not face direct negative selection at the genetic level; 2) the saturable epigenetic repair mechanisms proposed to occur during meiosis [

4] may introduce a steady influx of

de novo epimutations, allowing the trait to persist without needing to be genetically inherited. Moreover, an old and well-documented phenomenon in SSB research, the Fraternal Birth Order (FBO) effect, is more easily explained under the proposed framework than by the current consensus. The FBO effect refers to the consistent finding that a man’s probability of identifying as gay increases with the number of older biological brothers he has [

160,

161]. While current hypotheses suggest that this effect is caused by maternal immune responses, the epigenetic framework offers an alternative explanation: a higher burden of epigenetic defects in parental gonads leads to a greater likelihood that offspring will inherit these defects, even if the parents themselves do not display the trait. Parents with high burden of a SSB causing defect in its gonads will: 1) produce with more ease offsprings showing SSB, and 2) accumulate further epigenetic defects making even more feasible to have older SSB offsprings. In the last term this is due to the saturability of the repair capacity of the meiotic epigenetic correction mechanisms proposed [

4]. This mechanism could explain why later-born sons show a higher probability of SSB—a pattern fully compatible with the ED model proposed in this manuscript.

4.6. Epidemiological Considerations

This study is based on increases in the prevalence observed in many distinct human diseases or conditions. Most of the data collected from the literature corresponds to age-standardised data points. However, in cases where non-standardised data was available, this was used instead. Nonetheless, most of the data points used were age standardised. The reasoning behind age-standardisation is to correct for changes that are not due to a ‘genuine’ shift in disease frequency, but rather due to a change in the age structure of the population under scrutiny during the two time points. This is a perfectly valid reasoning if one assumes that ageing is due to ‘wear and tear’ scenarios—where simply more ‘wear and tear’ could explain the observed differences (if any). However, if you are using these data points to investigate the causes of ageing, why some individuals develop a given disease while others do not, or why certain people experience these conditions at an earlier chronological age while others encounter them later, age standardisation may remove information you would prefer to retain. This study is closely associated with a new proposal concerning the nature of ageing [

25] and its implications for other processes not ostensibly related to ageing [

1]. Consequently, age standardisation is not considered a strict requirement for the data used herein.

A second important consideration is that prevalence provides only a ‘snapshot’ at a given moment and does not capture events occurring in the intervening period. Prevalence can change for various reasons, including recovery (where an individual no longer has the disease), migration, or death—whether from the disease in question or another cause. In this respect, lifetime prevalence is a more comprehensive measure than point prevalence, as it records whether an individual has ever had the disease at any point in their life. However, the literature is dominated by studies reporting point prevalence, with far fewer providing lifetime prevalence data. Even so, I contend that lifetime prevalence is not the ideal measure for studies of this kind. This is because it fails to account for individuals who are no longer counted simply because they have died—regardless of whether death was due to the disease under study or to another cause. I therefore propose that the most informative and accurate approach would be to track a birth cohort, recording how many individuals born in a given year develop the disease at any point in their lives, without excluding those who have died, irrespective of the cause of death. Such a method would yield a more precise and holistic estimate of the proportion of a birth cohort that ultimately develops the disease, offering a clearer picture of its true long-term burden. A clear and illustrative example of this issue can be found in

Figure 1A of the study by Ganna et al. (2019) [

162]. This case is instructive in part because it focuses on homosexuality, a condition that does not inherently involve mortality among those expressing the phenotype. However, it is less helpful in that whether homosexuality is a biologically determined trait remains a contentious question—an issue already discussed earlier in this paper. In summary, because the present study relies on point prevalence data—which provides only a momentary snapshot and does not account for individuals who developed the disease but later died or were otherwise removed from the dataset—the true extent of the increase in prevalence may be substantially underestimated in the data presented here. Nevertheless, the results still show prevalence increasing at rates that are, at best, linear and, at worst, exponential (see Supplementary Figures 2–33).

Another key epidemiological point to consider is that the data used in this study combine data points from different populations, each of which may exhibit distinct local behaviours. This is not the ideal approach, but rather a necessity given the scarcity of prevalence trend data available in the literature. Nevertheless, even with imperfect data, a consistent global pattern emerges. While the integration of trends from heterogeneous populations does not meet the strict criteria for pooled epidemiological estimation, it is employed here as an exploratory synthesis to reveal patterns that are otherwise obscured by the scarcity of complete time-series data in the literature. The AMAV curves should therefore be interpreted as heuristic constructs — designed to visualise and compare broad temporal patterns — rather than as precise prevalence estimates for any specific population.

It is well recognised that societies adopting a more westernised lifestyle tend to exhibit higher prevalence rates than those that do not [

163]. A detailed analysis of why a westernised lifestyle is associated with greater disease prevalence lies beyond the scope of this paper, but is addressed in a preprint deposited in Zenodo by this author [

1]. Discussing this in depth would require consideration of cultural factors, which would unnecessarily expand the present work. The aspects explored in the Zenodo preprint will be developed further as a standalone paper by this author.

Building on the reasoning outlined in the preceding paragraphs, it is reasonable to assume that the actual increase in prevalence—if calculated using the birth cohort tracking methodology proposed above—could be even greater than the trends reported in this paper, particularly within certain populations. Moreover, systematic comparisons between populations would likely reveal clear differences. Such findings would provide a compelling example of an

Epigenetic Founder Effect, which should be observable if the flaw proposed in this paper is validated—analogous to the well-established

Genetic Founder Effect [

164,

165].

Finally, another significant challenge is that some of the conditions potentially influenced by the phenomenon discussed in this paper—that is, possible consequences of the ED phenomenon—are highly controversial, such as paedophilia and psychopathy. These conditions may be associated with criminal behaviour and are therefore often deliberately concealed, leading to an underestimation of their true prevalence. Because many individuals affected by these conditions do not disclose them, either due to legal repercussions or social stigma, their actual frequency may be considerably higher than reported. Moreover, these conditions are strongly linked to human cognition, which makes them particularly contentious but also of great interest for advancing our understanding of brain function and behaviour. Given their deeply uncomfortable societal implications, identifying effective strategies to prevent their occurrence should be considered a priority [

1].

4.7. Social Considerations

Recent political initiatives, such as the 2025 U.S. pledge to find the cause of autism within months, exemplify a narrow focus on single conditions. Our analysis shows that such patterns rarely occur in isolation: autism is part of a much wider and sustained rise across conditions spanning multiple physiological systems. This suggests that prevention and resource allocation strategies should be informed by cross-condition evidence, rather than by disease-specific silos, to address shared drivers more effectively. In concrete, the President of the United States has appointed Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (RFK) as Secretary of Health and Human Services, despite his well-known and controversial views on vaccines and autism. RFK has made bold claims, including that by September 2025 the department would know the cause of the ‘autism epidemic’ and be able to eliminate those exposures. Such statements are not only an affront to the many researchers conducting genuine scientific work, or indeed to anyone with even minimal critical thinking skills, but also represent a grave irresponsibility towards families affected by the severe manifestations of autism. Furthermore, they risk delaying progress in finding solutions to many other diseases by diverting resources away from genuinely promising initiatives [

166].

Ironically, however, Donald J. Trump (DJT) unintentionally touched on a point consistent with my hypothesis when he remarked, quite literally, ‘Maybe it’s a spray that we spray…’. And yes—this aligns closely with my central idea regarding the main factor driving up disease prevalence: males do, in fact, spray ‘something’. While this lies again outside the scope of the present paper, those who are impatient may refer directly to

Section 4.4.1 of the Zenodo preprint repeatedly cited herein [

1]. Regrettably for me, it appears I may have been scooped by DJT.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: XM. Writing—original draft, review, and editing: XM, with the assistance of Large Language Models (LLMs) developed by OpenAI, used solely for grammar correction, language refinement, and style improvement. All scientific content, analysis, and conclusions are the author’s own.

References

- Marsellach, X. Ageing is not just ageing. Zenodo. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Marsellach, X. The Principle of Continuous Biological Information Flow as the Fundamental Foundation for the Biological Sciences. Implications for Ageing Research. Preprints. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marsellach, X. A non-Lamarckian model for the inheritance of the epigenetically-coded phenotypic characteristics: a new paradigm for Genetics, Genomics and, above all, Ageing studies. bioRxiv. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marsellach, X. A non-genetic meiotic repair program inferred from spore survival values in fission yeast wild isolates: a clue for an epigenetic ratchet-like model of ageing. bioRxiv. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Korolenko, A.; Skinner, M.K. Generational stability of epigenetic transgenerational inheritance facilitates adaptation and evolution. Epigenetics 2024, 19, 2380929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzany G, editor. Epigenetics in Biological Communication. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024:0.

- Karin, O.; Miska, E.A.; Simons, B.D. Epigenetic inheritance of gene silencing is maintained by a self-tuning mechanism based on resource competition. Cell Systems 2023, 14, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Morales Valencia, M.; Yu, Y.; et al. Transgenerational inheritance of acquired epigenetic signatures at CpG islands in mice. Cell 2023, 186, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, E.; Lamb, M.J. Inheritance Systems and the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka, E.; Lamb, M.J. Evolution in four dimensions, revised edition: Genetic, epigenetic, behavioral, and symbolic variation in the history of life. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gissis, S.; Gissis, S.B.; Jablonka, E.; Zeligowski, A. Transformations of Lamarckism: from subtle fluids to molecular biology. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka, E.; Lamb, M.J. Epigenetic inheritance and evolution: the Lamarckian dimension. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Spadafora, C. Transgenerational epigenetic reprogramming of early embryos: a mechanistic model. Environ Epigenet 2020, 6, dvaa009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, M.K. Environmental Epigenetics and a Unified Theory of the Molecular Aspects of Evolution: A Neo-Lamarckian Concept that Facilitates Neo-Darwinian Evolution. Genome Biol Evol 2015, 7, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surachman, A.; Hamlat, E.; Zannas, A.S.; Horvath, S.; Laraia, B.; Epel, E. Grandparents’ educational attainment is associated with grandchildren’s epigenetic-based age acceleration in the National Growth and Health Study. Soc Sci Med 2024, 355, 117142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.D. Epigenetics of transgenerational inheritance of disease. Epigenetics in Human Disease. Elsevier; 2024. p. 989-1030.

- Švorcová, J. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Traumatic Experience in Mammals. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshe, N.; Eliezer, Y.; Hoch, L.; et al. Inheritance of associative memories and acquired cellular changes in C. elegans. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabarís, G.; Fitz-James, M.H.; Cavalli, G. Epigenetic inheritance in adaptive evolution. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2023, 1524, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Rothi, M.H.; Gerashchenko, MV.; et al. 18S rRNA methyltransferases DIMT1 and BUD23 drive intergenerational hormesis. Mol Cell 2023, 83, 3268–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, L.L.; Duque, V. In utero exposure to the Great Depression is reflected in late-life epigenetic aging signatures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2208530119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempradl, A. Germ cell-mediated mechanisms of epigenetic inheritance. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2020, 97, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzitallab, P.; Baruah, K.; Vanrompay, D.; Bossier, P. Can epigenetics translate environmental cues into phenotypes. Sci Total Environ 2019, 647, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, Z. Lamarck rises from his grave: parental environment-induced epigenetic inheritance in model organisms and humans. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2017, 92, 2084–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsellach, X. The Double Code Hypothesis of Ageing. Preprints. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ledford, H. Why are so many young people getting cancer? What the data say. Nature 2024, 627, 258–260. [Google Scholar]

- Licari, A.; Magri, P.; De Silvestri, A.; et al. Epidemiology of Allergic Rhinitis in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023, 11, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Straalen, J.W.; de Roock, S.; Giancane, G.e.t. al. Prevalence of familial autoimmune diseases in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the international Pharmachild registry. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2022, 20, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscheo, C.; Licciardello, M.; Samperi, P.; La Spina, M.; Di Cataldo, A.; Russo, G. New Insights into Iron Deficiency Anemia in Children: A Practical Review. Metabolites 2022, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.S. Lupus in children. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Elsevier; 2021. p. 527-533.

- Sahin, Y. Celiac disease in children: A review of the literature. World J Clin Pediatr 2021, 10, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Dahlmann-Noor, A. Myopia and its progression in children in London, UK: a retrospective evaluation. J Optom 2020, 13, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, S.M.; Irvine, A.D.; Weidinger, S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2020, 396, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; et al. Global Prevalence of Hypertension in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2019, 173, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascar, N.; Brown, J.; Pattison, H.; Barnett, A.H.; Bailey, C.J.; Bellary, S. Type 2 diabetes in adolescents and young adults. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology 2018, 6, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, C.C.; Saikaly, S.K.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Solomon, J.A. Prevalence of pediatric alopecia areata among 572,617 dermatology patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2017, 77, 980–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Kemp, J.L.; Crossley, K.M.; Culvenor, A.G.; Hinman, R.S. Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis Affects Younger People, Too. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017, 47, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, K.; Sahoo, B.; Choudhury, A.K.; Sofi, N.Y.; Kumar, R.; Bhadoria, A.S. Childhood obesity: causes and consequences. J Family Med Prim Care 2015, 4, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, I.; Pearce, N. Global burden of asthma among children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014, 18, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyürüs E, Green A, Soltész G, EURODIAB Study Group. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989-2003 and predicted new cases 2005-20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet 2009, 373, 2027–2033. [CrossRef]

- Branum, A.M.; Lukacs, S.L. Food allergy among children in the United States. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161.

- Hambleton, I.R.; Caixeta, R.; Jeyaseelan, S.M.; Luciani, S.; Hennis, A.J.M. The rising burden of non-communicable diseases in the Americas and the impact of population aging: a secondary analysis of available data. Lancet Reg Health Am 2023, 21, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, P.; Gorasso, V.; Plass, D.; et al. Burden of non-communicable disease studies in Europe: a systematic review of data sources and methodological choices. Eur J Public Health 2022, 32, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noncommunicable Diseases: A Globalization of Disparity? [editorial]. PLoS Med 2015, 12, e1001859.

- Michalek, I.M.; Koczkodaj, P.; Michalek, M.; Caetano Dos Santos, F.L. Unveiling the silent crisis: global burden of suicide-related deaths among children aged 10-14 years. World J Pediatr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Gehlawat, P. Assessment and Management of Emerging Personality Disorders in Adolescents. 2023. p. 255-267.

- Sun, C.F.; Xie, H.; Metsutnan, V.; et al. The mean age of gender dysphoria diagnosis is decreasing. Gen Psychiatr 2023, 36, e100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.A.; McArthur, D.; Hughes, MM.; et al. Progress and disparities in early identification of autism spectrum disorder: autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 2002-2016. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2022, 61, 905–914. [Google Scholar]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Ranum, B.; Wichstrøm, L. Prevalence and course of anxiety disorders and symptoms from preschool to adolescence: a 6-wave community study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2022, 63, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, S.; Peetoom, K.; Bakker, C.; et al. Global incidence of young-onset dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacz, J.; Brady, B.L. Increasing rate of diagnosed childhood mental illness in the United States: Incidence, prevalence and costs. Public Health Pract (Oxf) 2021, 2, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Post, R.M.; Miklowitz, DJ.; et al. A commentary on youth onset bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2021, 23, 834–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Cooper, A.B.; Joiner, T.E.; Duffy, M.E.; Binau, S.G. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol 2019, 128, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, C. Schizophrenia in children and adolescents. BJPsych Advances 2015, 21, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, D.E.; Lynn, R.; Viner, R.M. Childhood eating disorders: British national surveillance study. Br J Psychiatry 2011, 198, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multimorbidity: Addressing the next global pandemic [editorial]. PLoS Med 2023, 20, e1004229.

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Chandra Das, D.; Sunna, T.C.; Beyene, J.; Hossain, A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 57, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rising to the challenge of multimorbidity [editorial]. BMJ 2020;368:l6964.

- Carlson, D.M.; Yarns, B.C. Managing medical and psychiatric multimorbidity in older patients. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2023, 13, 20451253231195274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wędrychowicz, A.; Minasyan, M.; Pietraszek, A.; et al. Increased prevalence of celiac disease and its clinical picture among patients with diabetes mellitus type 1—observations from a single pediatric center in Central Europe. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2021, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulet, L.P. Obesity and atopy. Clin Exp Allergy 2015, 45, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofori, F.; Fontana, C.; Magistà, A.; et al. Increased prevalence of celiac disease among pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a 6-year prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr 2014, 168, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.R.; Kim, B.K.; Yoon, N.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Ahn, S.Y.; Lee, W.S. Differences in Comorbidity Profiles between Early-Onset and Late-Onset Alopecia Areata Patients: A Retrospective Study of 871 Korean Patients. Ann Dermatol 2014, 26, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, J.L.; Sheehan, W.J.; Baxi, S.N.; et al. Food Allergy and Increased Asthma Morbidity in a School-Based Inner-City Asthma Study. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2013, 1, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.; Aarnio-Peterson, C.M.; Conard, L.A.; Lenz, K.R.; Matthews, A. Eating disorder symptoms among transgender and gender diverse youth. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2024, 29, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, S.; Theni, M.C.; Kaliappan, K.; et al. The Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Path of Science 2023, 9, 4001–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnejat, A.M.; Babaie, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; et al. The prevalence of cluster B personality disorder in young male homosexuals. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hisle-Gorman, E.; Landis, C.A.; Susi, A.; et al. Gender Dysphoria in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. LGBT Health 2019, 6, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.; Stokes, M.A. Sexual Orientation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Research 2018, 11, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, J.; Kamio, Y.; Takahashi, H.; et al. Autistic-like traits in adult patients with mood disorders and schizophrenia. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0122711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.F.; Doerfler, L.A. ADHD with comorbid oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder: discrete or nondistinct disruptive behavior disorders. J Atten Disord 2008, 12, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Soczynska, J.K.; Bottas, A.; Bordbar, K.; Konarski, J.Z.; Kennedy, S.H. Anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder: a review. Bipolar Disorders 2006, 8, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.R.; Kosson, D.S. Handedness and Psychopathy. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, T.D.; Bulik, C.M.; Neale, M.; Kendler, K.S. Anorexia nervosa and major depression: shared genetic and environmental risk factors. Am J Psychiatry 2000, 157, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.M. Homosexuality and mental illness. Archives of general psychiatry 1999, 56, 883–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satz, P.; Green, M.F. Atypical handedness in schizophrenia: some methodological and theoretical issues. Schizophr Bull 1999, 25, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langs, G.; Quehenberger, F.; Fabisch, K.; Klug, G.; Fabisch, H.; Zapotoczky, H.G. Prevalence, patterns and role of personality disorders in panic disorder patients with and without comorbid (lifetime) major depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1998, 98, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesuyan, M.; Jani, Y.H.; Alsugeir, D.; et al. Trends in the incidence of dementia in people with hypertension in the UK 2000 to 2021. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2023, 15, e12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciciulla, D.; Soriano, V.X.; McWilliam, V.; Koplin, J.J.; Peters, R.L. Systematic Review of the Incidence and/or Prevalence of Eating Disorders in Individuals With Food Allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023, 11, 2196–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Launders, N.; Kirsh, L.; Osborn, D.P.J.; Hayes, J.F. The temporal relationship between severe mental illness diagnosis and chronic physical comorbidity: a UK primary care cohort study of disease burden over 10 years. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, A.; Kosir, U.; Tek, C. Prevalence of obesity and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia. World J Diabetes 2017, 8, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-de-Andrés, A.; Jiménez-Trujillo, M.I.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; et al. Trends in the prevalence of depression in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes in Spain: analysis of hospital discharge data from 2001 to 2011. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0117346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raevuori, A.; Haukka, J.; Vaarala, O.; et al. The increased risk for autoimmune diseases in patients with eating disorders. PLoS One 2014, 9, e104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceretta, L.B.; Réus, G.Z.; Abelaira, HM.; et al. Increased prevalence of mood disorders and suicidal ideation in type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Diabetol. 2012, 49 Suppl 1, S227–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, A.; Hay, P.; Mond, J.; Quirk, F.; Buttner, P.; Kennedy, L. The rising prevalence of comorbid obesity and eating disorder behaviors from 1995 to 2005. Int J Eat Disord 2009, 42, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, J.; Laedtke, T.; Parisi, J.E.; O’Brien, P.; Petersen, R.C.; Butler, P.C. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 2004, 53, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.J.; Freedland, K.E.; Clouse, R.E.; Lustman, P.J. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.L.; Montgomery, S.M.; Galloway, M.L.; Pounder, R.E.; Wakefield, A.J. Inflammatory bowel disease and laterality: is left handedness a risk. Gut 2001, 49, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; He, Y.; Jiang, B.; et al. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension during 2001-2010 in an urban elderly population of China. PloS one 2015, 10, e0132814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Have, M.; Verheul, R.; Kaasenbrood, A.; et al. Prevalence rates of borderline personality disorder symptoms: a study based on the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, H.; Cramer, H.; Lauche, R.; Gass, F.; Dobos, G.J. The prevalence and burden of subthreshold generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isomaa, R.; Isomaa, A.L.; Marttunen, M.; Kaltiala-Heino, R.; Björkqvist, K. The prevalence, incidence and development of eating disorders in Finnish adolescents: a two-step 3-year follow-up study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2009, 17, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, S.A.; Crow, S.J.; Le Grange, D.; Swendsen, J.; Merikangas, K.R. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011, 68, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, S14–S31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S. Prediction of a rise in antisocial personality disorder through cross-generational analysis. Prediction of an Increase in Personality Disorder. 2019.

- Coid, J.; Ullrich, S. Antisocial personality disorder is on a continuum with psychopathy. Compr Psychiatry 2010, 51, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twells, L.K.; Janssen, I.; Kuk, J.L. Epidemiology of Adult Obesity. Edmonton, Canada: Obesity Canada; 2020.

- Devlin, H. More than 800 million people around the world have diabetes, study finds. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stobbe, M. CDC finds nearly 1 in 3 US youth have prediabetes, but experts question scant data. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, S. Half a billion young people will be obese or overweight by 2030, report finds. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, S. One in four young people in England have mental health condition, NHS survey finds. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Stobbe, M. American kids have become increasingly unhealthy over nearly two decades, new study finds. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons-Duffin, S. Autism rates keep rising. What RFK Jr. and the CDC plan to do next. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J. Trump administration cut autism-related research by 26% so far in 2025. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial, B. What’s going on at HHS? RFK Jr.’s staffing choices raise alarm. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rocque, R.J.; Beaudoin, C.; Ndjaboue, R.; et al. Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, D.P. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ 1989, 299, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, J.-F. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 2002, 347, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, P.; Galante, J.; Pickering, J.; et al. Healthy lifestyles reduce the incidence of chronic diseases and dementia: evidence from the Caerphilly cohort study. PLoS One 2013, 8, e81877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Triggers, Consequences, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Options [editorial]. Microorganisms 2022;10(3):578.

- Portela, A.; Esteller, M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, P.E.; Bourrat, P. Integrating evolutionary, developmental and physiological mismatch. Evol Med Public Health 2023, 11, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anway, M.D.; Cupp, A.S.; Uzumcu, M.; Skinner, M.K. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science 2005, 308, 1466–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Maamar, M.; Wang, Y.; Nilsson, E.E.; Beck, D.; Yan, W.; Skinner, M.K. Transgenerational sperm DMRs escape DNA methylation erasure during embryonic development and epigenetic inheritance. Environ Epigenet 2023, 9, dvad003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.W.S.; Leitch, H.G.; Requena, CE.; et al. Epigenetic reprogramming enables the transition from primordial germ cell to gonocyte. Nature 2018, 555, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, J.A.; Surani, M.A. DNA methylation dynamics during the mammalian life cycle. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2013, 368, 20110328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, M.; Oakey, R.J. Resetting for the next generation. Mol Cell 2012, 48, 819–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Sakurai, T.; Imai, M.; et al. Contribution of intragenic DNA methylation in mouse gametic DNA methylomes to establish oocyte-specific heritable marks. PLoS Genet 2012, 8, e1002440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Z.D.; Chan, M.M.; Mikkelsen, TS.; et al. A unique regulatory phase of DNA methylation in the early mammalian embryo. Nature 2012, 484, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirasawa, R.; Chiba, H.; Kaneda, M.; et al. Maternal and zygotic Dnmt1 are necessary and sufficient for the maintenance of DNA methylation imprints during preimplantation development. Genes Dev 2008, 22, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E. Chromatin modification and epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet 2002, 3, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A. Living with the past: evolution, development, and patterns of disease. Science 2004, 305, 1733–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijmans, B.T.; Tobi, E.W.; Stein, AD.; et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 17046–17049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Daskalakis, N.P.; Lehrner, A.; et al. Influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in Holocaust survivor offspring. American Journal of Psychiatry 2014, 171, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accordini, S.; Calciano, L.; Johannessen, A.; et al. A three-generation study on the association of tobacco smoking with asthma. Int J Epidemiol 2018, 47, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonegawa, S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature 1983, 302, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarese, G. The link between obesity and autoimmunity. Science 2023, 379, 1298–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-J.; Wei, C.-C. Chang C-Y.; et al. Role of Chronic Inflammation in Myopia Progression: Clinical Evidence and Experimental Validation. EBioMedicine 2016, 10, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, D.; Sellam, J.; Berenbaum, F.; Guicheux, J.; Boutet, M.-A. The role of the immune system in osteoarthritis: mechanisms, challenges and future directions. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2025, 21, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Du, Z.; Lu, B. Chronic low-grade inflammation associated with higher risk and earlier onset of cardiometabolic multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults: a population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 22635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioakeim-Skoufa, I.; González-Rubio, F.; Aza-Pascual-Salcedo, M.; et al. Multimorbidity patterns and trajectories in young and middle-aged adults: a large-scale population-based cohort study. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1349723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordova, R.; Viallon, V.; Fontvieille, E.; et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases:multinational cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health—Europe. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Caviness, C.K.; Moyer, J.; Weaver, A.; Devlin, R.; Diaz-Sanchez, D. Associations between PFAS occurrence and multimorbidity as observed in an electronic health record cohort. Environ Epidemiol 2022, 6, e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, K.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Rossato, SL.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and cardiovascular disease: analysis of three large US prospective cohorts and a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Lancet Reg Health Am 2024, 37, 100859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, M.A.; Setoguchi, S.; Gerhard, T.; et al. Early childhood antibiotics and chronic pediatric conditions: a retrospective cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskinson, C.; Petersen, C.; Turvey, S.E. How the early life microbiome shapes immune programming in childhood asthma and allergies. Mucosal Immunol 2025, 18, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Colucci, M.; et al. The mixed effect of Endocrine-Disrupting chemicals on biological age Acceleration: Unveiling the mechanism and potential intervention target. Environ Int 2024, 184, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonides, C.; Aromataris, E.; Mulders, Y.; et al. An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses Evaluating Associations between Human Health and Exposure to Major Classes of Plastic-Associated Chemicals. Ann Glob Health 2024, 90, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnadi, N.E.; Carter, D.A. Climate change and the emergence of fungal pathogens. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1009503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Valle, J.; Valencia, A. Molecular bases of comorbidities: present and future perspectives. Trends Genet 2023, 39, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Diaz, S.A.; Priego-Parra, B.A.; Ordaz-Alvarez, HR.; et al. Unequal Burdens: Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Sexual and Gender Minority Communities vs Cisgender Heterosexual Individuals. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, T.; Collins, S.; St Louis, J. The prevalence of hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome at a gender-affirming primary care clinic. SAGE Open Med 2025, 13, 20503121251315021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, E.; Kneale, D.; Patalay, P. Sexuality and respiratory outcomes in the UK: disparities, development and mediators in multiple longitudinal studies. Public Health 2025, 247, 105886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deraz, O.; Caceres, B.; Streed, CG.; et al. Sexual Minority Status Disparities in Life’s Essential 8 and Life’s Simple 7 Cardiovascular Health Scores: A French Nationwide Population-Based Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2023, 12, e028429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegener, D.; McFaline-Figueroa, J.; Goldstein, R. Migraine Prevalence in Gender Identity Minorities (P14-12. 004). Neurology 2023, 100, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.B.; Norland, K.; Blackburn, M.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Harris, R.A. Evidence of increased cardiovascular disease risk in left-handed individuals. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1326686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallitsounaki, A.; Williams, D.M. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Gender Dysphoria/Incongruence. A systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 2023, 53, 3103–3117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goetz, T.G.; Adams, N. The transgender and gender diverse and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder nexus: A systematic review. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 20221-18.

- Sherman, J.; Dyar, C.; McDaniel, J.; et al. Sexual minorities are at elevated risk of cardiovascular disease from a younger age than heterosexuals. J Behav Med 2022, 45, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]