1. Introduction

This article presents a framework originally developed by the author in a PhD; it articulates elements of the research relative to atmospheres design. Atmospheres have been described as the fluid, diffused, intangible and impermanent phenomena that determine the character of a space [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In architecture, Pallasmaa [

5] and Zumthor [

2] argue that atmospheres are sensed through a building’s qualities and perceived emotionally. We make sense of the places we inhabit through our senses and in the process, we also perceive their emotional tone, the way their qualities appear to us [

6]. Whilst recognising that atmospheres can be artificially conceived or staged, as art or as commodity, or even skewed to exercise subtle forms of power and behavioural control [

7], this study draws on Beecher [

8] to bring attention to the way they can also be cultivated by nurturing their sensory-emotional dimension in the authentic identities and qualities of spaces. In particular, it foregrounds the simple but powerful notion that public environments cultivating rewarding atmospheric qualities are more conducive to belonging and wellbeing. This is explored here through the specific lens of the personalisation of the visitor experience in the public interior, and drawing inspiration from the writings of Kuksa and Fisher [

9], this experiential context is defined as a visitor-centred approach that caters for a variety of needs and preferences. This research revealed that such an approach enhances visitors’ ability to connect both sensorially and emotionally to their environment. It also uncovered that personally and deeply felt connections developed over time can contribute to emotional attachment to place.

Echoing Böhme’s [

1] phenomenological understanding that atmospheres are perceived as being-in-something, Zumthor [

2] (p. 13) explains that the first thing he experiences when he enters a space is how its atmosphere resonates with his emotional sensibility. It is the way a building moves him that determines his ability to perceive qualities in architecture. This phenomenon however is not restricted to the physical environment. Brand [

10] (p. 145) explains that “the mood of a room” emerges through its design and that “the mood in a room” emanates from the actions of its inhabitants. This understanding foregrounds an atmospheric interrelation between spatio and socio-sensory phenomena. Here, spatio-sensory phenomena originate in the design and subsequent management of the public interior. Socio-sensory phenomena originate in the way visitors enact their experience. Together, these determine the sensory-emotional dimension of atmospheres and by exploring the link between this dimension and connectedness - in the public interior and in the context of the personalisation of experience - this research uncovers principles conducive to a design understanding of the visitor emotional attachment to place. Insights are then brought together into a framework for those interested in enhancing the relationship between people and their environment, to foster a greater sense of sensory-emotional wellbeing in the public realm. This includes architects, designers, academics, students and professionals managing public spaces.

The framework bridges a gap discussed by architects and designers who challenged spatial practices that did not consider sensory and emotional needs [

3,

11,

12,

13,

14]. It contributes a method dedicated to the creation of multisensory environments for people to thrive and supports practices exploring how spaces designed for the sensing body can contribute to wellbeing [

5,

13,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. It offers a way to cultivate atmospheres for positive long-term relations between the sensing body and its environment. Going back to Böhme’s [

1] phenomenological perspective, it promotes sensory-emotional processes that can foster a better quality (or better qualities) of being-in-something, not simply being in a space as an individual but also being with others within it. It contributes to our understanding of how atmospheres design impacts the way people experience and feel about their surroundings.

2. Methodology

The methodology is grounded in a phenomenologically inspired conception of experience. Drawing on Coxon’s [

23] discussion of Husserl’s classification of experience, this study explores deeply and personally felt lived experiences visitors are conscious of and their cumulative effect to identify the phenomena that make “a special impression that gives it lasting importance” [

24] (p.3). Drawing on Frechette et al. [

24] (p. 4, italics in the original text), it is oriented toward understanding and uncovering lived experiences of “one’s

horizon of significance of being-in-the-world” and those of “individuals in constant

being-with-others” because individual experiences of the public interior unfold within collective ones.

It is interpretative rather than descriptive because it seeks to understand what it feels like for visitors to experience the environment of the public interior, how they perceive its atmospheric qualities emotionally. This is not however about visitors feeling, for instance, relaxed and happy, but about finding out whether they experience the atmosphere of the public interior as relaxing and enjoyable, whether they feel welcomed. Hence, this research uncovers emotional responses to embodied perception, direct perception in the present, and resulting mental images because these responses determine the qualities that visitors assign to their experience of the environment. The conscious awareness of these qualities emerges through the emotionality of the sensing body to define the emotional tone of the environment for visitors. Accordingly, this study takes the view that the sensing body and its environment are intimately connected, and an embodied worldview influenced by Merleau-Ponty [

25,

26] places the body as the primary means of perception. Visitors perceive phenomena in the public interior - sounds, smells, colours, textures, movement, and so forth - because they inhabit its spaces and interact with these, their objects and people, through the materiality of their body. Following from this, emotionality is not simply an internal bodily state, it is an essential element of embodied perception and permeates environmental experience [

2,

5,

10,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Mallgrave [

14] highlights that as design elements and organising principles such as colour, texture, scale or rhythm engage the senses, they contribute to our perception of the emotional tone of a space; its atmosphere.

3. Research Plan and Methods

The research plan contributing to the realisation of the framework is structured across two stages: a literature review followed by a case study and interviews. The research also includes design experiments to test the usability, transferability and value of the framework although these fall outside the focus of this paper.

3.1. Definition of an Experiential Context

This investigation begins by engaging with relevant literature [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39] to anchor the investigation of atmospheres in the public interior into a suitable experiential context and define the boundaries of the study. The recognition of a lineage between the personalisation of experience and emotional attachment to place, spanning both private and public interiors, led to the personalisation of the visitor experience becoming the experiential context for this study. Madanipour [

35] (p. 71) explains that the home is a place personalised by its inhabitants to reflect their identity, a place where territories are formed, a place that provides physical and psychological shelter and comfort, a place for self-expression and autonomy. These attributes have also in more recent times become associated with places outside private dwellings, places that may be public [

36]. Indeed, Pimlott [

40] (p.18) depicts the public interior as “a shelter and a home, a place of the city and within the city.” He [

41] (p. 1) foregrounds choice, comfort, convenience, pleasure, recognition and curiosity as essential qualities of public interiors and explains that these may not just fulfil visitors’ needs but also relate to “their views of themselves, their identities or lifestyles”.

Drawing on Kuksa and Fisher [

9], the personalisation of experience is structured across two complementary and interdependent dimensions: ‘personalisation for visitors’, the way a space is designed and managed, and ‘personalisation by visitors’, the way they engage with their environment to enact a diversity of needs and preferred activities. Here, visitors can enact a relative agency and thus personalise their experience. Then, these dimensions are further subdivided into three pairs of principles to facilitate the documentation of specific situations in the fieldwork. These are: looseness and appropriation, enticement and exploration and porosity and privateness. Looseness, enticement and porosity relate to ‘personalisation for’. Appropriation, exploration and privateness relate to ‘personalisation by’. Their precise definition is provided in the presentation of the framework in section 4.

3.2. The Site-Specific Study

This element triangulates insights from the literature review. It brings together a case study on the personalisation of the visitor experience, an interview with staff, and interviews with a sample of nine visitors. The Royal Festival Hall, a prominent cultural venue and public interior located in London, was selected as the research site following an in-depth comparative study of five public interiors also in London for parity. The case study consists of a non-participant observation and reflexive investigation into the visitor experience and the site documentation took place across multiple visits over a three-year period. Each visit lasted between two to three hours, and these were staggered across different times of day and different days of the week to achieve saturation. A multi-media diary format was employed to facilitate the documentation of multisensory phenomena. The fieldwork includes the mapping, description and visualisation of phenomena and the depiction of corresponding emotional qualities. For this notes, photographs, annotated sketches, films and sound recordings were used. Phenomena and emotional qualities were documented as they presented themselves to gather a rich representation of experience and resulting atmospheres

of and

in the environment. Nonetheless, this study acknowledges that since direct perception is selective [

14,

30,

42,

43], the fieldwork is relative to the perception of the researcher, which further justifies the need for interviews with staff and visitors to triangulate insights from the case study.

The case study fieldwork was first examined off-site using visualisation techniques as a thematic analysis method to facilitate understanding and identify situations. In the first instance, information gathered on site was visualised into annotated photographic compositions and diagrams to organise the fieldwork and iteratively make sense of it. This process is akin to a collage bringing together mental images from different study visits to foreground significant phenomena and situations pertaining to looseness and appropriation, enticement and exploration and porosity and privateness. From this, twenty distinctive types of situations emerged. These were organised into three collections, each aligned with one of the three pairs of principles that define the personalisation of the visitor experience in this study. They serve as the foundation for the final stage of the case study analysis, which is structured using an analytical model developed from the literature review in stage one [

33,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. For example, the principle of porosity is characterised by the use of boundaries, borders and liminal edges. These are discussed by Sennett [

47] in the context of urban environments and adapted to this study. The analytical model delineated below ensures methodological consistency across all twenty situations:

Personalisation by (enactment).

Appropriation: how do visitors identify or exploit possibilities to enact a relative autonomy or self-expression?

Exploration: how do visitors enact modes of approach behaviour characterised by movement towards and body-environment sensory interactions?

Privateness: how do visitors enact positive territoriality from vantage points where they can maintain sensory connections with the macro-scale of the environment?

Emotional sense-making

What does it feel like to experience appropriation, exploration or privateness?

How are these qualities grounding or stimulating?

How are these qualities consequential or communicated?

Sensory rewards

Personalisation for (architecture/design and management practices).

Looseness: how are accessibility (permeability) and freedom of choice designed and managed?

Enticement: how are partly hidden/partly revealed phenomena designed and managed to arouse curiosity? How do forms and materials invite touch?

Porosity: how are boundaries, borders and liminal edges designed and managed to regulate sensory flows?

Barriers

3.4. Staff and Visitor Interviews

The staff and visitor interviews also draw on the situations identified and analysed in the case study to maintain methodological coherence. Accordingly, an elicitation interview method was used by drawing on a selection of images illustrating each of the twenty situations identified in the case study. Hogan, Hinrichs and Hornecker [

53] explain that the elicitation interview is grounded in phenomenology and can help trigger insights into the nature and quality of everyday experiences. They also highlight that the technique works best when exploring a singular lived experience rather than carrying out a general exploration. Here, visual references of the situations identified in the case study represent singular lived experiences. They act as a conduit to elicit mental images in interviewees. A semi-structured interview process also ensures that the discussion remains within the boundaries of the study, whilst facilitating a conversational tone for visitors to share their experience and tell their story. This format provides the flexibility required for the interviewer to adjust the questions and wording to gain detailed insights from each interviewee and respond to unexpected topics [

54,

55]. Visitor interviewees are also provided with a full spectrum of positive and negative emotional keywords to choose from to synthesise their perception of the emotional tone of the public interior of the Royal Festival Hall. Including negative emotional keywords alongside positive ones alleviates potential bias towards positive qualities.

The interviewee selection process draws on theories of purposeful sampling for qualitative insights collection and analysis because this allows for representativeness, for the selection of participants that are the most knowledgeable about the topic being investigated [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Maxwell [

58] (p.97) explains that “[i]n this strategy, particular settings, persons, or activities are selected deliberately to provide information that is particularly relevant to [the research] questions and goals”. The Head of Visitor Experience and Ticketing at the Royal Festival Hall contributes expert knowledge on the management of the visitor experience. It centres on the impact of historical, political, economic and geographical contexts , and on the way looseness, enticement and porosity influence visitors’ ability to enact a variety of needs and preferred activities. Then, the visitor interviews amplify the phenomenological enquiry initiated in the case study by contributing first-person perspectives on what it is like and feels like to enact appropriation, exploration and privateness. These interviews open a window into the way visitors perceive the emotional tone of the public interior and how this impacts their ability to experience emotional attachment to place.

4. The Sensory-Emotional Framework

It is beyond the scope of this paper to showcase the entire framework. Instead, its top-level components are presented here to articulate its structure, discuss key processes and define terminologies. These are presented in the order that it is conceived they would be used although the process may be iterative. It is possible to revisit and reference any of the elements of the framework at any stage of the process. The design of the framework draws on data visualisation methods to bring the complexity of this research into a structured, coherent and usable format. It also aims to be visually appealing to facilitate engagement. Information is layered to manage complexity and emphasise relationships. Elements are organised into categories and colours are used to group them. Bold text on a light-coloured background is repeated across the framework to provide consistency of design and ensure clarity. The framework consists of five sections headed by circular models synthesising information.

Sections one and two interrelate, and sections three to five expand on section two. The models adopt a circular design to reflect the notion that experience is a flow, it is dynamic and fluid, always shifting [

27,

60,

61]. A vertical or horizontal design might suggest constancy and hierarchy, but a circular design evokes fluidity and synergies better suited to the characteristics of atmospheres.

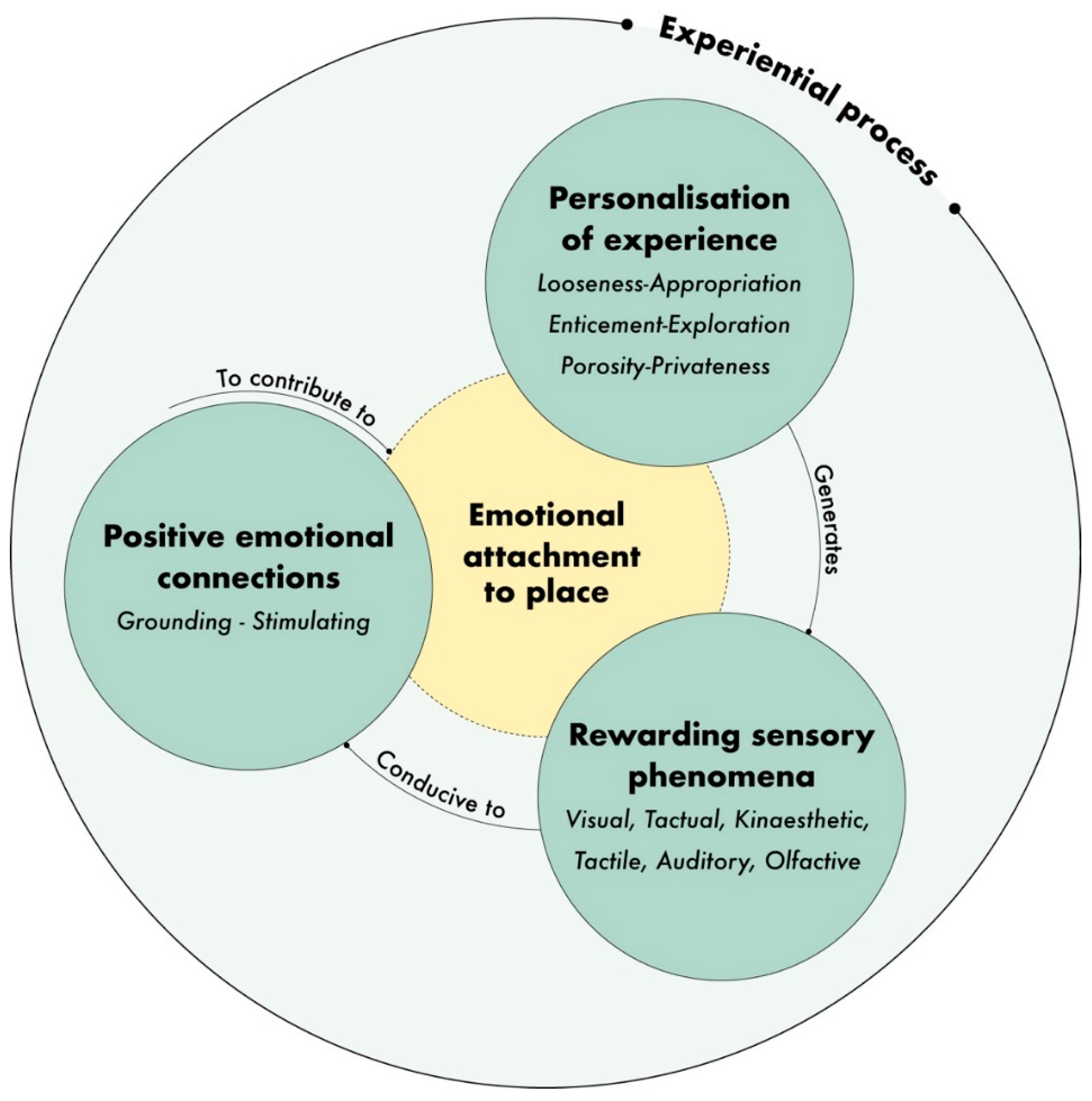

4.1. The Experiential Process

The first section introduces the experiential process developed through this research (

Figure 1). It expresses the sensory-emotional dimension of atmospheres and reads as follows: the personalisation of experience in the public interior can generate rewarding sensory phenomena conducive to visitors’ ability to develop positive emotional connections with their environment. Significant phenomena retained as mental images and re-experienced over time can deepen connections and develop into more intimate forms of emotional attachment to place.

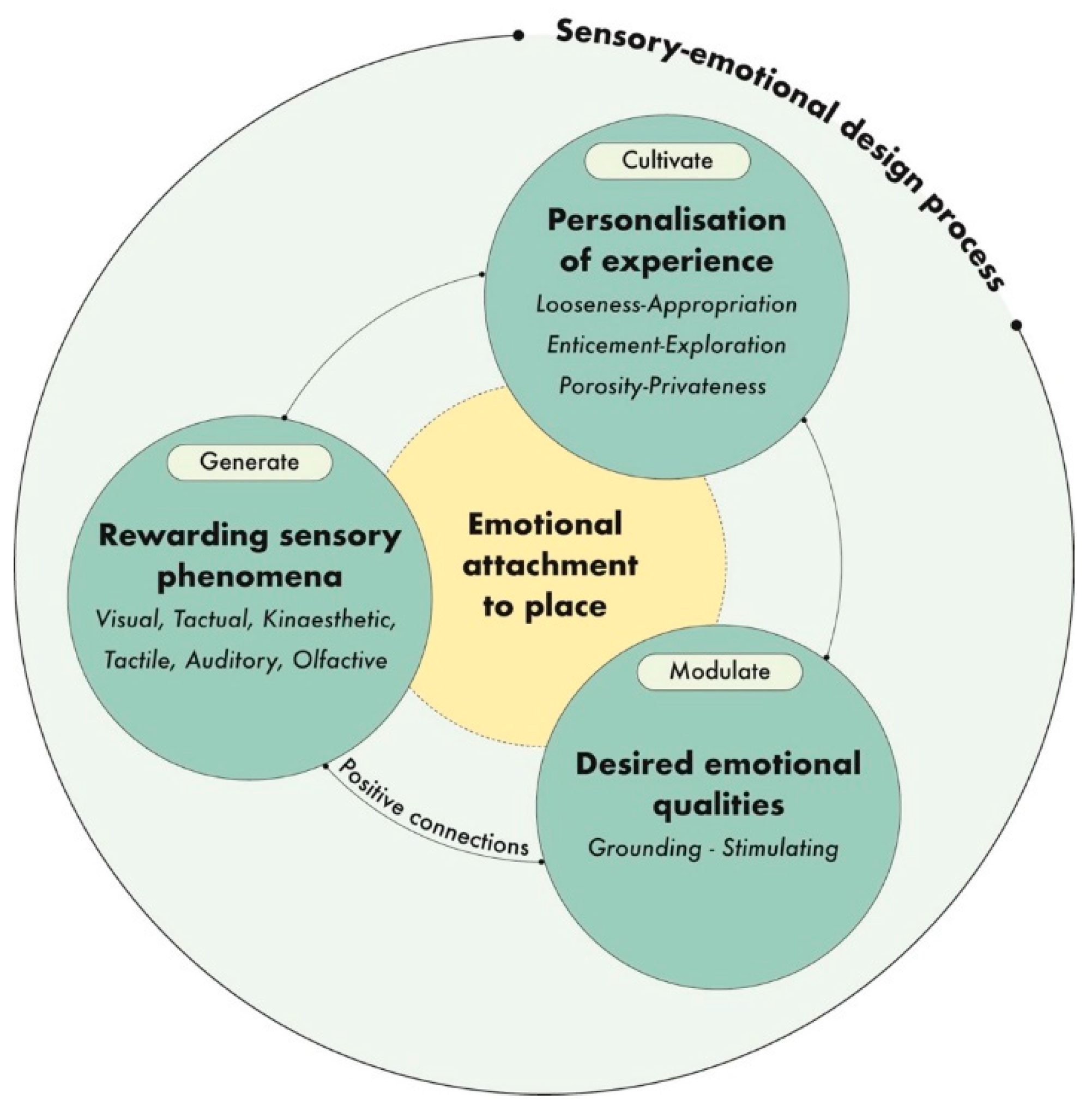

4.2. The Sensory-Emotional Design Process

The framework then reframes this experiential process as a sensory-emotional design process (

Figure 2). It first considers which principles and characteristics pertaining to the personalisation of experience are best suited to the public interior and its occupants, focusing on the ways in which looseness, enticement and porosity could cultivate appropriation, exploration and privateness. Next, the process highlights the need to anticipate desired grounding and stimulating emotional qualities to examine what the visitor experience could be/feel like. From this, it is then possible to explore which sensory phenomena generated through design and management practices, and through visitors’ actions and interactions, may be conducive to the formation of the desired emotional tone. In sum, the sensory-emotional design process is structured by three interrelated components: cultivate (visitor-centred experiences), modulate (desired emotional qualities), generate (rewarding sensory phenomena). This process places emotional qualities before sensory phenomena because we perceive the wholeness of situations qualitatively before we understand their discreet phenomena [

26,

62]. This became explicit in the way visitor interviewees discussed their connection with the public interior of the Royal Festival Hall and in the design experiments developed to test this framework. It is thus proposed to first evaluate the desired emotional tone of an environment and introduce rewarding phenomena accordingly.

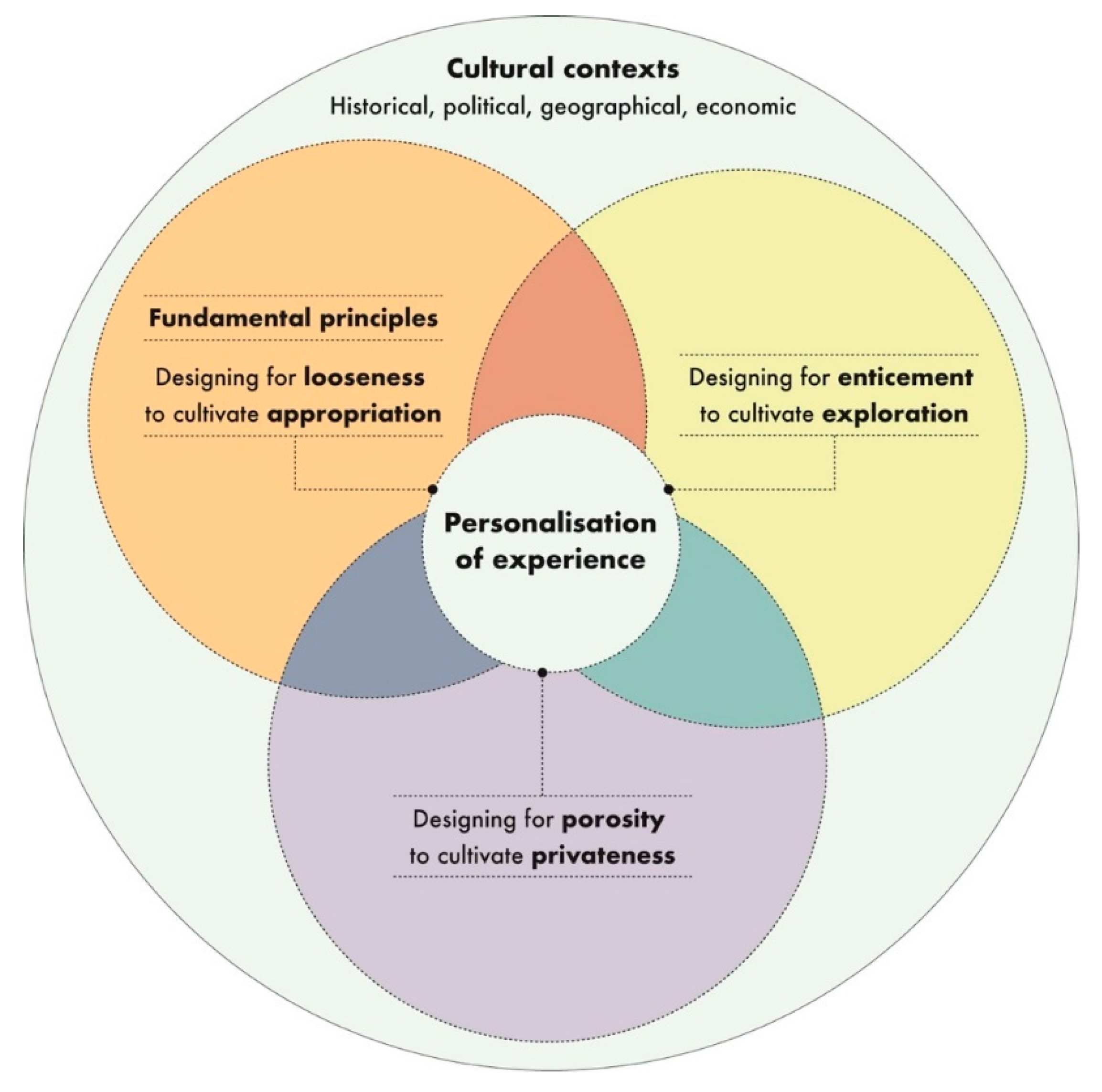

4.3. The Personalisation of Experience

The third section of the framework (

Figure 3) defines the personalisation of experience, its principles and characteristics. A Venn diagram is used to illustrate that these principles are distinctive yet complementary and interdependent. This section also foregrounds the notion that historical, political, geographical and economic contexts impact architecture/design and management practices; they may bring benefits but also create tensions. It includes prompts to guide processes and a starter list of known barriers to minimise. It then concludes with a matrix created to explore the visitors’ profile and their needs with an emphasis on promoting a diversity of people and activities.

The personalisation of experience

A visitor-centred approach to designing public interiors and managing the visitor experience that caters for a diversity of people and activities.

Looseness

Architecture/design and management practices are characterised by openness, generosity and flexibility. Looseness brings life into the environment to contribute to a diversity of people and activities.

Openness: the permeability of the environment. Physical and psychological barriers are minimised without compromising safety.

Generosity: Practices that can support a variety of activities and cultivate mental ownership.

Flexibility: the provision of moveable elements and objects enables visitors to reorganise the space to suit their needs.

Experiential loop: a reciprocity between looseness and appropriation means that appropriation can also influence management practices and cultivate looseness.

Appropriation

Visitors experience a degree of mental ownership and freedom of choice to enact a relative autonomy or self-expression.

Enacting a relative autonomy: visitors identify possibilities in the environment. Their behaviour is within designed and managed expectations and can contribute to the informality of the environment.

Enacting self-expression: visitors exploit possibilities in the environment. Their behaviour is outside designed and managed expectations and can contribute to the idiosyncrasy of the environment.

Social contagion: seeing and hearing others enacting appropriation can cultivate appropriation.

Enticement

Architecture/design and management practices characterised by the composition of partly hidden/revealed sensory phenomena to arouse curiosity and by forms/materials that invite touch.

Partly revealed/hidden phenomena: these are determined by the composition and organisation of three-dimensional elements.

Curiosity (or anticipation): when curiosity is aroused, visitors enact modes of approach behaviour (curiosity may become anticipation when familiarity sets in).

Approach behaviour: visitors actively engage and interact with their surroundings. This can foster intimate connections between body and environment.

Exploration

Visitors enact modes of approach behaviour characterised by movement towards, flânerie and body-environment interactions.

Enacting movement towards: visitors move towards partly hidden/revealed phenomena to satisfy curiosity.

Enacting flânerie: visitors meander slowly through the environment. They may sometimes pause for a short while.

Enacting body-environment interactions: visitors look, listen, sit, lean, touch, grab, hold, inhale, etc.

Social contagion: seeing others enacting exploration can cultivate exploration.

Appropriation: is a precursor to exploration because exploration requires openness (permeability).

Porosity

The composition of boundaries, borders and liminal edges to regulate sensory flows.

Boundaries: three-dimensional elements and surfaces with little or no porosity.

Borders: three-dimensional elements and surfaces that are partially or entirely porous.

Liminal edges: sensory thresholds, perceived transitions from one sensory condition to another.

Sensory flows: the phenomena perceived through sight, hearing, smell and passive touch that flow through a space.

Intimacy gradients: the organisation across space of variations in nested comfort in the micro-scale of the body.

Privateness

Visitors enact positive territoriality. They define personal or group territories in the micro-scale of the body from vantage points.

Vantage point: a territory from which visitors can maintain sensory connections with the macro-scale of the physical environment and its social life. Visitors are still part of the life of the environment even though they may not actively participate in it. This can help them feel comfortable, safe and sustained.

Social contagion: seeing and hearing others enacting privateness can cultivate privateness.

Appropriation: is a precursor to privateness because privateness requires openness, generosity and flexibility.

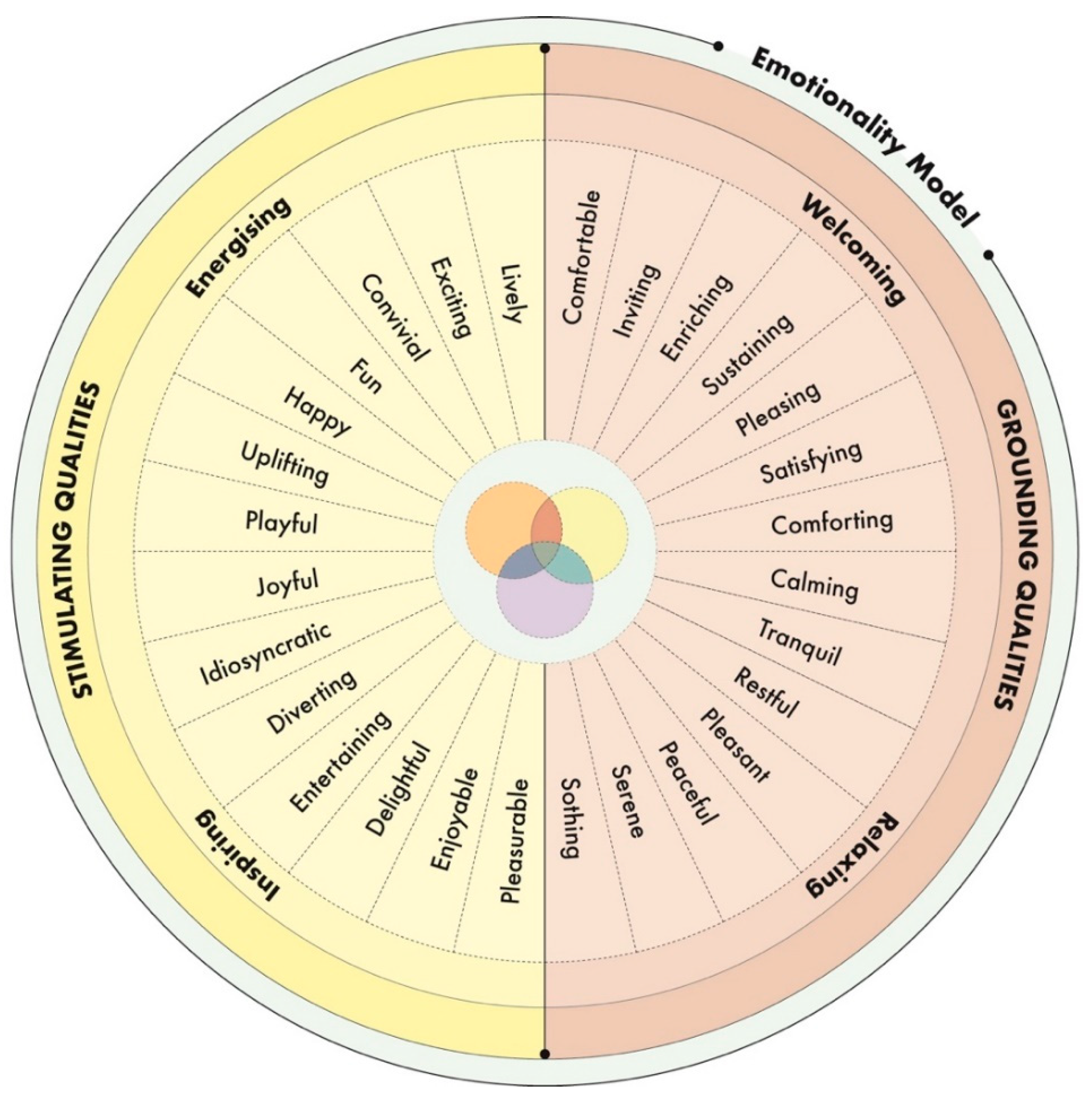

4.4. The Emotionality Model

The fourth section, an emotionality model (

Figure 4), points to grounding and stimulating emotional qualities deemed pertinent to positive individual and collective experiences. It also includes matrices to modulate these qualities. This is an invitation to reflect on the emotional tone of the public environment across space and across time. For example, qualities in natural light can alter the way a space is perceived, and these qualities can vary greatly depending on the time of year or even across a single day. The level of activity in a space - sounds, movements - can also impact the way it is experienced qualitatively.

The reflective process is underpinned by a broad question: what would it be/feel like for visitors to experience looseness-appropriation, enticement-exploration, porosity-privateness? It centres on the notion that emotionality permeates environmental experience as architectural/design elements and human activities engage the senses and define atmospheres whose qualities are perceived emotionally as either grounding or stimulating [

63,

64]. Grounding qualities are linked to familiarity and stability whilst stimulating qualities are dynamic and perhaps more idiosyncratic in nature.

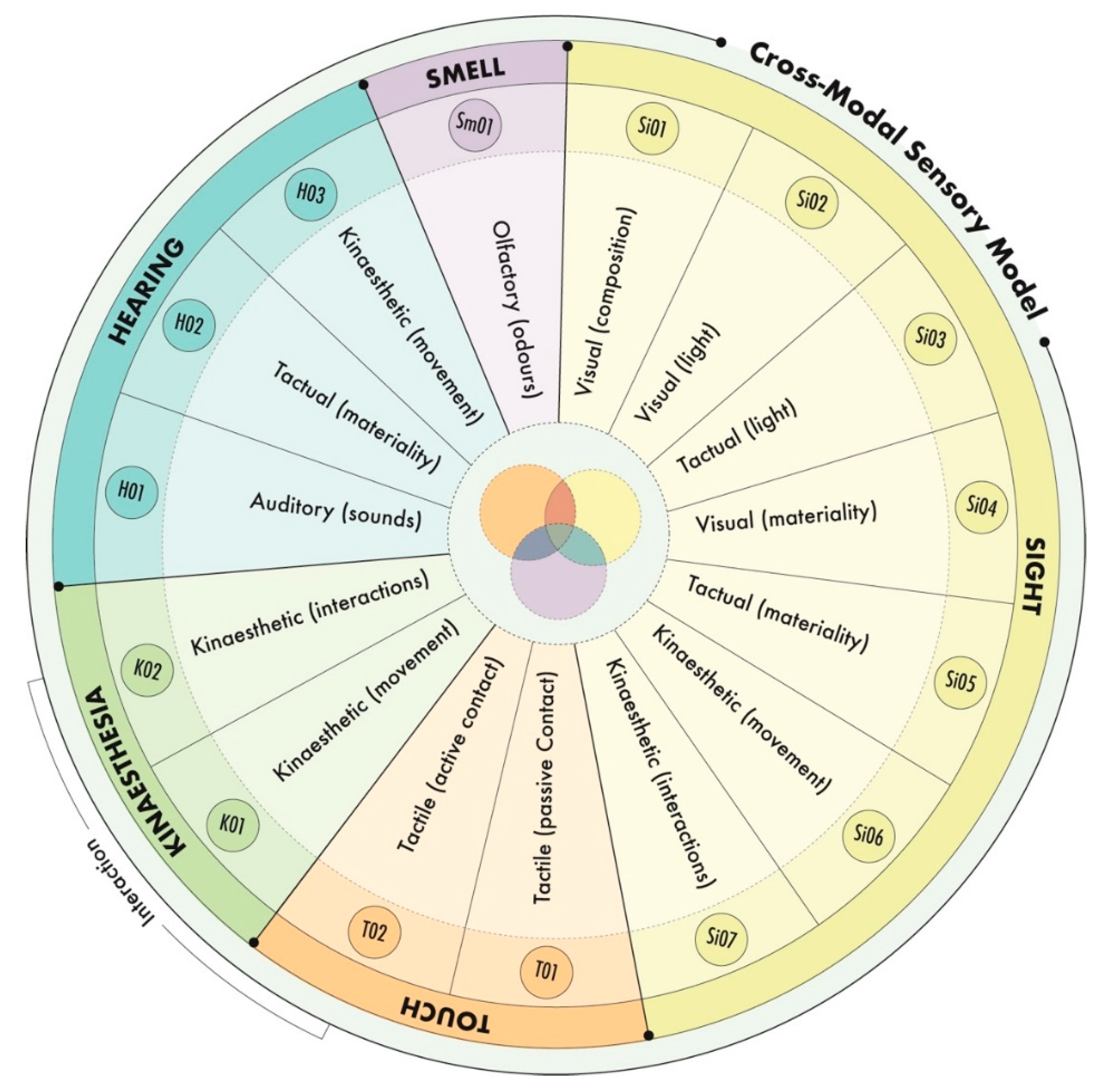

4.5. The Sensory Model

The final section (

Figure 5) articulates a sensory model. It is the most significant element of the framework for the cultivation of atmospheres and this calls for a detailed discussion of its features.

This sensory model is distinctive because it articulates the cross-modality of the senses, the way sensory phenomena associated with a modality can be perceived through another. Phenomena associated with touch can be perceived visually, a process referred to by Le Breton [

65] (p. 34) as the “haptic way of seeing”. Expanding on this notion, this model highlights that it is also possible to perceive kinaesthetic phenomena through sight when observing the movement, postures and gestures of others. For example, seeing people slowly meandering through a space or leaning back on a sofa can contribute to the perception of relaxation and comfort in the observer. Then, through social contagion, it can even induce the observer to perform similar actions. Furthermore, phenomena associated with touch and kinaesthesia can be perceived through hearing. For example, the sound of someone walking will be perceived differently kinaesthetically to the sound of someone running. It is also possible to perceive the weight of a door from the sound it makes as it closes. Hence, this model integrates cross-modal dimensions in sight and hearing because it is not just what we see or what we hear, it is also about how we perceive tactual sensations and how we sense movement through our eyes or ears. The term ‘tactual’ is used in the cross-modal context of sight and hearing to denote that the body is not actively touching or being touched. The term ‘tactile’ is used for the modality touch because a direct sensation occurs through skin and body contact. The model also opens a window into the way touch and muscle sensation interrelate and the intermodal perception between exteroceptive tactile sensations and interoceptive muscle sensations is highlighted.

In addition, this model expands significantly on existing sensory models by including an extensive library of phenomena and their corresponding characteristics. The list is not exhaustive, but it is as comprehensive as it was possible to achieve through this research. It provides a detailed reference to explore the correspondence between spatio and socio-sensory phenomena and desired grounding to stimulating qualities in the physical and social environments. Each section of the sensory wheel (

Figure 4) is labelled with a symbol. The S in Si01, Si02, Si03, through to Si07 stands for sight, the T in T01 and T02 stands for touch, the K in K01 and K02 stands for kinaesthesia, and so forth. These codes provide an easy way to connect the wheel with corresponding libraries of phenomena and their attributes. Examples of libraries relating to sight and hearing are included in

Appendix A.

These libraries do not simply list phenomena, they include definitions and value scales. For example, a focal point is defined as a dominant feature in a space and elements of its design may have a value scale. The intensity of its colour for instance has a value scale between brightness and dullness. In another example, the localisation of a smell is defined by its origin and distance from the body. This information does not represent a value scale, but it can nonetheless prompt consideration of the distance between the source of a smell and the position of visitors, thereby helping to assess its qualitative impact on the visitor experience. Other phenomena do not call for definitions because they are best understood using a value scale. For example, weight is expressed as the degree of lightness to heaviness, temperature as the degree of warmth to coolness. Whilst useful, value scales are not typically included in sensory models but may be emphasised in the literature such as when Rasmussen [

66] (p. 24) discusses impressions of hardness and softness, and heaviness and lightness in the surface character of materials. They also feature in Malnar and Vodvarka’s [

11] (pp. 247-248) ‘Sensory Slider’, a schematic devised to document sensory information in buildings. Introducing value scales into this sensory model provides a foundation for qualitative experiential practices.

As with other models, the separation of modalities into categories is necessary but artificial, only serving the purpose of organising information. Sight dominates this model, occupying almost half of the wheel. This is consistent with the understanding that vision is our most dominant sense. Research in neuroscience for instance shows that half of the sensory information reaching the brain is visual [

67] and in this study, cross-modality is indeed most prominent in sight. Smell was placed at the top of the model to help alleviate this ascendancy and the wheel design aims to minimise issues of hierarchy to convey the notion that the senses work in unison. For example, we may look at a carpeted floor and, at the same time, feel its softness underfoot as we walk across it. Here, the collaboration between sight, kinaesthesia and touch contribute to the perception of the carpeted floor. Thus, the organisation of the five modalities included in this model does not imply a hierarchy or sequence but simply that the senses interrelate, and that experience is always multisensory.

5. Discussion

This framework articulates a qualitative process where architectural, design and management practices interrelate with visitors’ actions and interactions. It seeks to generate rewarding sensory phenomena conducive to visitors’ ability to develop positive emotional connections with their environment. It foregrounds the convergence of the physical and social environments in the cultivation of atmospheres. The way the physical environment is designed and managed generate spatio-sensory phenomena. The way visitors engage and interact with the physical environment and with each other generates socio-sensory phenomena. Grounding and stimulating visual, tactual, tactile, kinaesthetic, auditory and olfactive phenomena contribute to the emotional tone of the public interior – to welcoming, relaxing, inspiring and energising atmospheres. First-person perspectives also showed that rewarding phenomena can motivate visitors to come back, and that the cumulative effect of positive emotional connections can strengthen the bond between body and environment. Over time, this can contribute to visitors experiencing deeply and personally felt emotional attachment to place.

The framework presents a new experiential process structured across four interrelated concepts: experience, reward, connection, attachment. Its distinctive sensory-emotional design method is defined by three mutually related components: cultivate, modulate, generate. It includes a matrix to explore variations contingent on the historical, political, geographical, and economic contexts that define the cultural environment of the public interior. It also acknowledges that visitors’ personal characteristics such as prior experiences and life events can colour their experience. Personal characteristics point to factors impacting the visitor experience that may lie outside the direct control of architects, designers or managers and the framework includes another matrix to help foster a diversity of people and activities. Then, the emotionality model supports the modulation of primary grounding and stimulating qualities that constitute the desired emotional tone of an environment. Next, the sensory model, designed to support the introduction of rewarding spatio and socio sensory phenomena, integrates three important features of sensory perception. Firstly, perception is always multisensory, and a circular design draws attention to the collaboration of the senses. Secondly, perception is intermodal. The model highlights how the senses can interact by focusing on the specific context of touch and muscle sensation. Thirdly, perception is cross-modal. This is expressed by placing a decisive emphasis on the way phenomena associated with one sensory modality can be perceived through another. Furthermore, the model introduces qualitative value scales (such as the degree of roughness or smoothness of a surface) to support the evaluation of the rewarding potential of sensory phenomena.

Together, these elements articulate an explicit path for architects, designers and managers to follow, to imagine or re-imagine everyday experiences by amplifying the role of personalisation, sensing and emotionality in the creation of welcoming and sustaining public interiors. It contributes an approach to designing that cultivates sensory-emotional connectedness and it is envisaged that this contribution could extend beyond the context of the public interior into the public realm more broadly. It is an open framework, which supports its long-term viability. The elements of the framework can be interpreted and re-interpreted to adjust to variable conditions; new dimensions, characteristics or phenomena may also be added in future. It is foundational, which means that it is not prescriptive, it does not intend to supersede other frameworks and established practices. It is also important to note that this framework does not claim to enable architects, designers or managers to determine how visitors would feel, nor does it assert that visitors will systematically experience emotional attachment to place. Its strength lies in its ability to enrich opportunities for the creation of environments where the sensory-emotional dimension of atmospheres can contribute to visitors’ ability to thrive individually and collectively. It provides a vision and direction to foster more intimate relations between visitors and their environment to contribute to their sense of belonging and wellbeing.

6. Conclusions

This framework is an original contribution, and its content was successfully tested through design experiments. It was created to bridge a gap in and contribute to existing sensory-emotional practices discussed in the architecture and design literature [

3,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Brand [

10] (p. 21) also argues that a dependence of architecture on the production and reproduction of images prioritises style over embodied experiences. This perspective substantiates the need for a sensory-emotional framework promoting body-experience-centred design, to foreground the value of what Mallgrave [

14] (p. 92) calls the “nonquantifiable elements of a design that endow the human habitat with life, vitality, decorum, and pleasing atmospheric qualities”.

Looking ahead, the framework could also be used by researchers exploring the sensory-emotional dimension of atmospheres in existing environments, communities and cultures, expanding its outreach beyond the original boundaries of this study. For instance, a research-oriented version of this framework could contribute to an ethnographic-style methodology. As an open framework, it also presents a starting point for adjustments to be made to remove barriers and support the sensory-emotional inclusion of diverse populations, including neurodivergent individuals and those with physical impairments. In the current framework, sight dominates the sensory model but additional research with specific groups could generate alternative models. This is an open invitation to others interested in cultivating or exploring atmospheres as a sensory-emotional dimension of experience.

Examples of libraries of phenomena created for the sensory model. The categories Si04 and Si05 are shown here for the modality sight, and the categories H01, H02 and H03 reference the modality hearing. The complete library is organised across fifteen categories.

Sensory phenomena perceived through sight (Si04 and Si05: Materiality).

Si04 - Visual qualities generated by materials and surfaces.

Colour: its identity (red, blue, yellow, etc).

Intensity: the degree of brightness to dullness.

Value: the degree of lightness to darkness.

Opaqueness: the degree of opacity to transparency.

Pattern: the ratio of surface simplicity to complexity.

Rhythm and repetition: regular or irregular variations in patterns.

Scale: the size of the patterns.

Si05 - Tactual qualities generated by materials and surfaces.

Qualities associated with touch, but the body is not actually touching or being touched.

Texture: the degree of roughness to smoothness.

Contour identity: the degree of sharpness to smoothness.

Firmness: the degree of hardness to softness.

Weight: the degree of heaviness to lightness.

Solidity: the degree of density to diffusion.

Temperature: the degree of warmth to coolness.

Moisture: the degree of wetness to dryness.

Sensory phenomena perceived through hearing (H01, H02 and H03: sounds, materiality and movement)

H01 – Auditory qualities generated by the sound of space, objects and people.

Intensity: the degree of loudness to quietness.

Pitch: the degree of sharpness to softness

Localisation: the origin and distance from the body.

Duration: ambient or episodic.

Identity: the signature sound that characterises a location.

H02 – Tactual qualities generated by elements and objects.

Qualities associated with touch but the body is not actually touching or being touched.

Weight: the degree of heaviness to lightness.

Materiality: the degree of hardness to softness.

Fluidity: the degree of liquefaction.

H03 – Kinaesthetic qualities generated by the movement of people and objects.

References

- Böhme G. Atmosphere as the Subject Matter of Architecture. In: Ursprung P, editor. Natural History. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture, Lars Müller Publishers; 2005. p. 398-406.

- Zumthor P. Atmospheres. Basel: Bïrkhauser; 2006.

- Pallasmaa J. The Eyes of the Skin. Architecture and the Senses. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

- Griffero T. Atmospheres: Aesthetics of Emotional Space. Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing; 2010.

- Pallasmaa J. Space, Place and Atmosphere. Emotion and Peripheral Perception in Architectural experience. Lebenswelt Aesthetics and Philosophy of Experience. 2015(4):230-45.

- Mallgrave HF. Architecture and Embodiment. The implications of the new sciences and humanities for design. London and New York: Routledge; 2013.

- Borch C. The Politics of Atmospheres: Architecture, Power, and the Senses. In: Borch C, editor. Architectural Atmospheres On the Experience and Politics of Architecture. Basel: Bïrkhauser; 2014.

- Beecher MA. Regionalism and the Room of John Yeon’s Watzek House. Interior Atmospheres Architectural Design. 2008:54-.

- Kuksa I, Fisher T, editors. Design for personalisation. New York: Routledge; 2017.

- Brand AR. Touching Architecture. Affective Atmospheres and Embodied Encounters. London and New York: Routledge; 2023.

- Malnar JM, Vodvarka F. Sensory design. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press; 2004.

- Caan S. Rethinking Design and Interiors – Human Beings and the Built Environment. London: Laurence King; 2011.

- Bica A. Bringing Back Emotion and Intimacy in Architecture Canada2016 [Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNqL3iA5xKE.

- Mallgrave HF. From Object to Experience. The New Culture of Architectural Design. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts; 2018.

- Maslow AH, Mintz NL. Effects of Esthetic Surroundings: 1. Initial Short-Term Effects of Three Esthetic Conditions upon Perceiving “Energy” and “Well-Being” in Faces. In: Gutman R, editor. People and Buildings. New York: Basic Books; 1972. p. 212-9.

- Alexander C. The Timeless Way of Building. New York: Oxford University Press; 1979.

- Hiss T. The Experience of Place. A new way of looking and dealing with our radically changing cites and countryside. New York: Vintage Book; 1990.

- Stenberg EM. Healing Spaces. The Science of Place and wellbeing. Cambridge, Massasuchetts: Harvard University Press; 2009.

- Bermudez J. Empirical aesthetics: the body and emotion in extraordinary architectural experiences. ARCC Spring Research Conference; 2011; Lawrence Technological University, Southfield, MI2011. p. 369-80.

- Robinson S. Boundaries of Skin: John Dewey, Didier Anzieu and Architectural Possibility. In: Tidwell P, editor. Architecture and Empathy. Espoo, Finland: Tapio Wirkkala-Rut Bryk Foundation; 2015.

- Pink S. Design Anthropology for Wellbeing Design for Wellbeing2017 [Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gM8q3l6nPCk.

- Clements-Croome D, Mace V, Dmour Y, Dwivedi A, editors. Special issue: Multisensory Research and Design for Health and Wellbeing in Architectural Environments2021.

- Coxon I. Fundamental Aspects of Human Experience: A Phenomeno(logical) Explanation. In: Benz P, editor. Experience Design Concepts and Case Studies. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic; 2015.

- Frechette J, Bitzas V, Aubry M, Kilpatrick K, Lavoie-Tremblay M. Capturing Lived Experience: Methodological Considerations for Interpretive Phenomenological Inquiry. Sage. 2020;19:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty M. The World of Perception. London and New York: Routledge; 2004.

- Merleau-Ponty M. Phenomenology of Perception. London & New York: Routledge; 2012.

- Dewey J. Art as Experience. In: Boydston JA, editor. The Later Works 1925-1953 Vol 10. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press; 1987.

- Gendlin ET. The primacy of the body, not the primacy of perception: How the body knows the situation and philosophy. Man and World. 1992;25(3-4):341-53.

- Damasio A. The feeling of what happens. Body, emotion and the making of consciousness. London: Vintage; 2000.

- Johnson M. The Meaning of the Body. Aesthetics of Human Understanding. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press; 2007.

- Colombetti G. The Feeling Body. Affective Science Meets the Enactive Mind. Cambridge, Massachussetts; London, England: The MIT Press.; 2014.

- Mallgrave HF. Architecture and Empathy. Espoo, Finland: Tapio Wikkala-Rut Bryk Foundation; 2015.

- Bachelard G. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press; 1958.

- Tuan Y-F. Space and Place. The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press; 1977.

- Madanipour A. Public and Private Spaces of the City. London and New York: Routledge; 2003.

- Blunt A, Dowling R. Home. Abingdon: Routledge; 2006.

- Omar EO, Endut E, Saruwono M. Personalisation of the Home. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012;49:328-40. [CrossRef]

- Bernheimer L. The shaping of us : how everyday spaces structure our lives, behaviour, and well-being. London: Robinson, an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group; 2017.

- Barnes A. Creative Representations of Place. London and New York: Routledge; 2019.

- Pimlott M. Interiority and the Conditions of Interior. Interiority. 2018;1(1):5-20.

- Pimlott M. The Public Interior: TUDelft; 2020 [Available from: https://www.tudelft.nl/bk/over-faculteit/afdelingen/architecture/organisatie-1/secties-en-groepen-nieuw/situated-architecture/interiors-buildings-cities/research-publications/the-public-interior.

- Goldstein BE. Sensation and Perception. International edition. Eight edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2010.

- Cope W. Perceptual Images and Mental Images: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 2019 [Available from: https://www.coursera.org/lecture/multimodal-literacies/11-3-perceptual-images-and-mental-images-H08eo.

- Franck KA, Stevens Q. Tying Down Loose Space. e-book ed. London and New York: Taylor & Francis e-library; 2006. 1-29 p.

- Hildebrand G. Origins of Architectural Pleasure. Bekerley, Los Angeles, london: University of California Press; 1999.

- Kaplan S. Aesthetics, Affect, and Cognition. Environment and Behaviour. 1987;19(1):3-32.

- Sennett R. Building and Dwelling. Ethics for the City. London: Penguin; 2019.

- Whyte WH. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces; 1980.

- Mehrabian A. Public Spaces and Private Spaces. The Psychology of Work, Play, and Living Environments. New York: Basic Books Inc.; 1976.

- Tester K. The Flâneur. London: Routledge; 1994.

- Alexander C, Ishikawa S, Silverstein M. A Pattern Language. Towns. Buildings. Constructions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1977.

- Covatta A. Density and Intimacy in Public Space. A case study of Jimbocho, Tokyo's book town. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health. 2017;3(5).

- Hogan T, Uta Hinrichs, Hornecker E. The Elicitation Interview Technique: Capturing People’s Experiences of Data Representations. IEEE Transactions on Visualisation and Computer Graphics. 2016;22(12). [CrossRef]

- Thomas G. How to do your research project. A guide for students in education and applied social sciences. London: SAGE Publications; 2013.

- Robson C, McCartan K. Real World Research. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley and Sons; 2016.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. ; 2002.

- Creswell JW, Plano-Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed method research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011.

- Maxwell JA. Qualitative Research Design. An Interactive Approach. London: Sage Publications; 2013.

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533-44. [CrossRef]

- Ingold T. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London & New York: Routledge; 2011.

- Escobar A. Designs for the Pluriverse. Radical Independence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham and London: Duke University Press; 2018.

- Alexander C. The Phenomenon of Life: The Nature of Order, Book 1. Bekerley, CA: The Centre for Environmental Structure; 2004.

- Rice C. The Emergence of the Interior. Architecture, Modernity, Domesticity. London and New York: Routledge; 2007.

- Russell JA. A Circumplex Model of Affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39(6):1161-78.

- Le Breton D. Sensing the World. An Anthropology of the Senses. London, Oxford, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury; 2017.

- Rasmussen SE. Experiencing Architecture. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1959. [CrossRef]

- Sussman A, Hollander JB. Cognitive architecture : designing for how we respond to the built environment. London: Taylor Francis Group; 2015.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).