Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

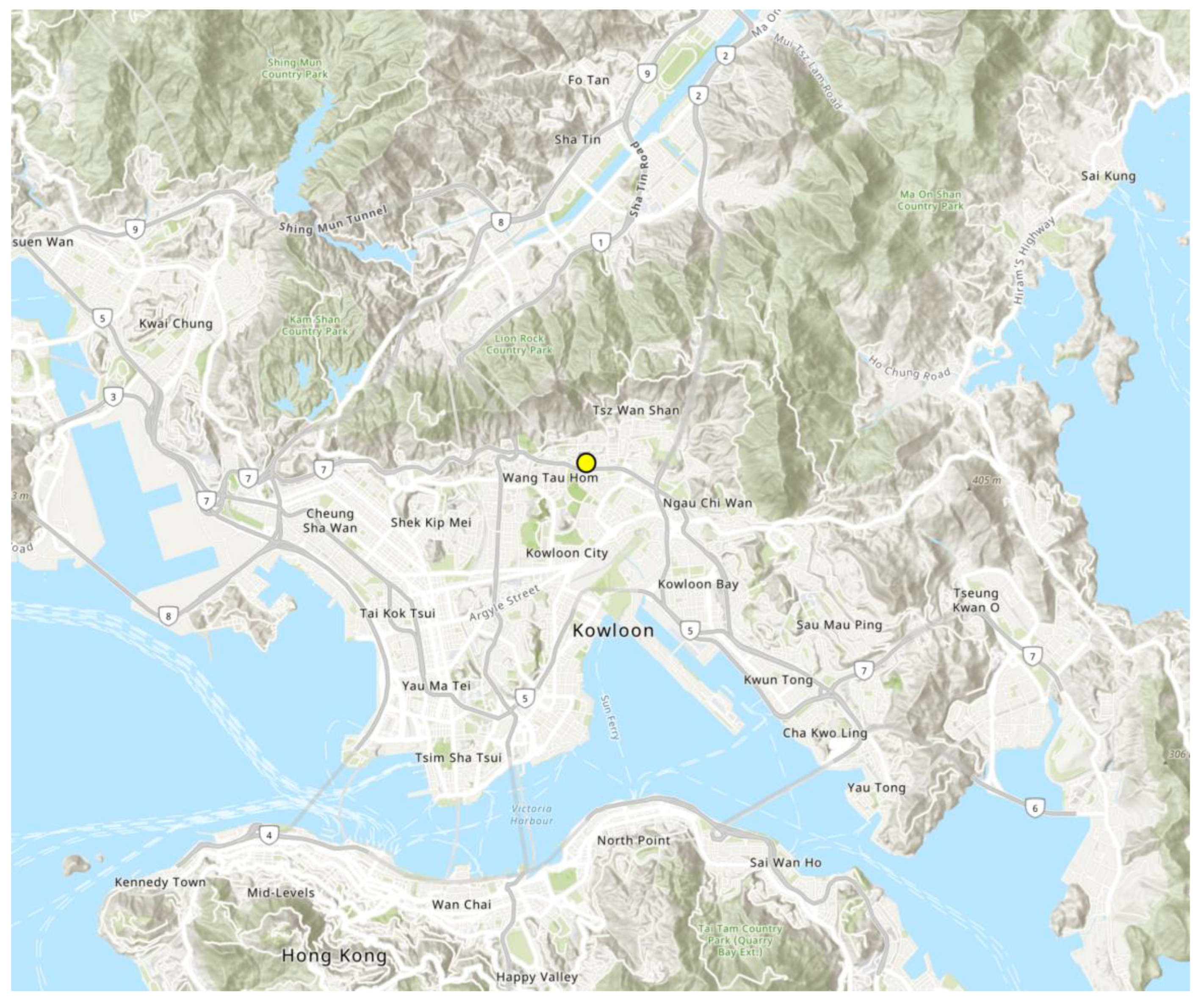

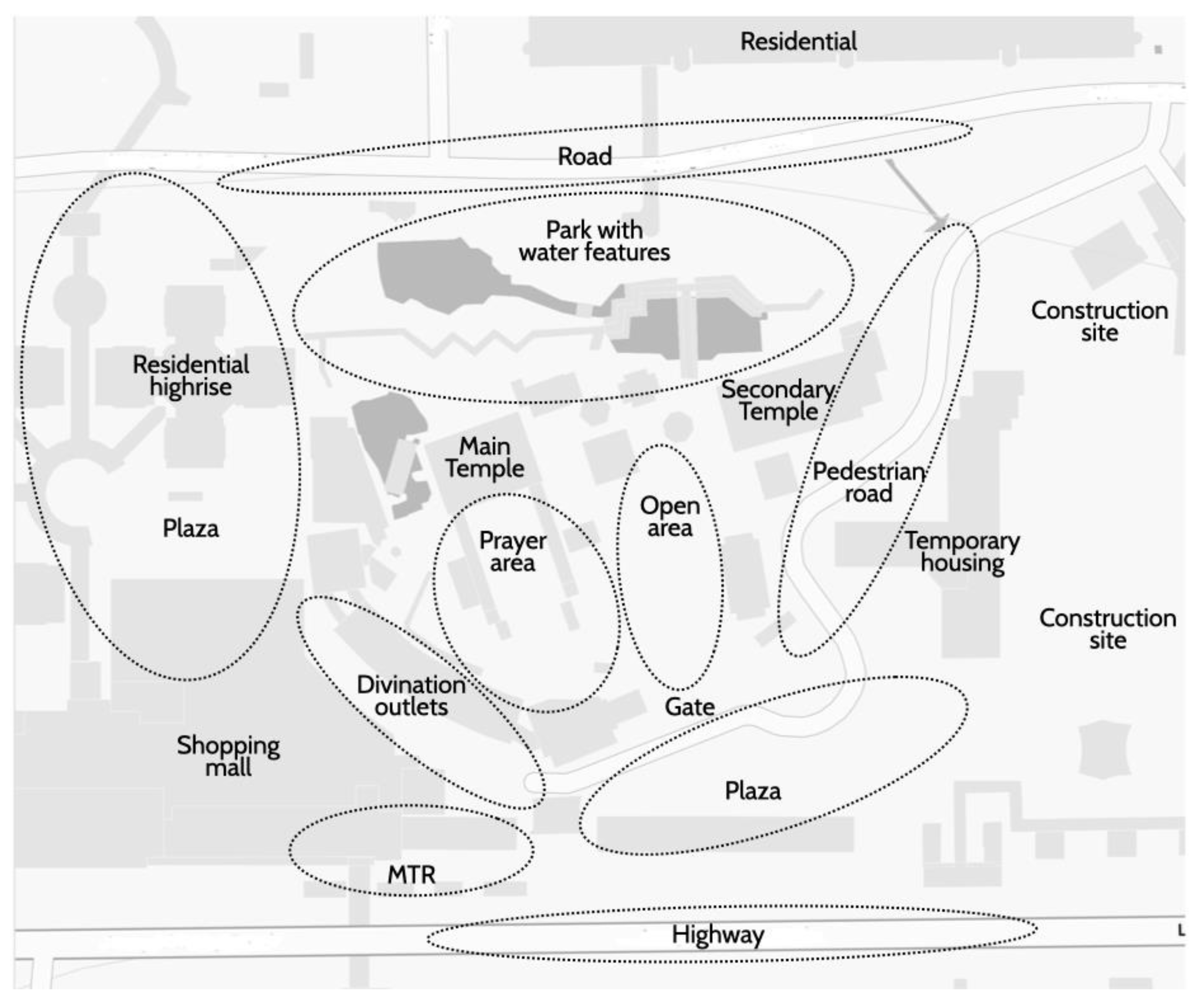

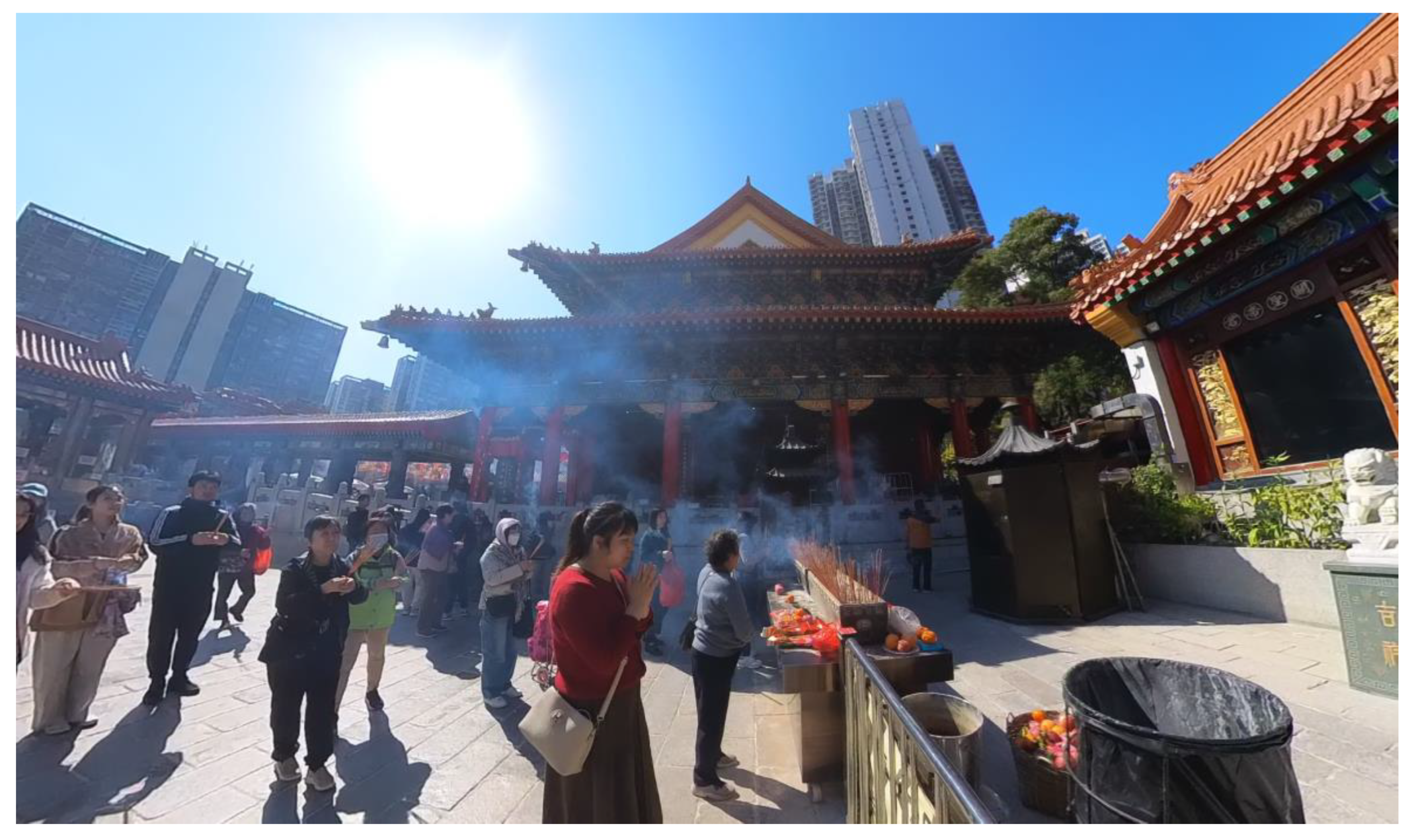

2.1. Site Characteristics

2.2. Data Collection and Methods

2.3. Acoustic Measures

2.4. Soundscape Ratings

2.5. Smellscape Ratings

2.6. Audiovisual Recordings

2.7. Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Missing Data

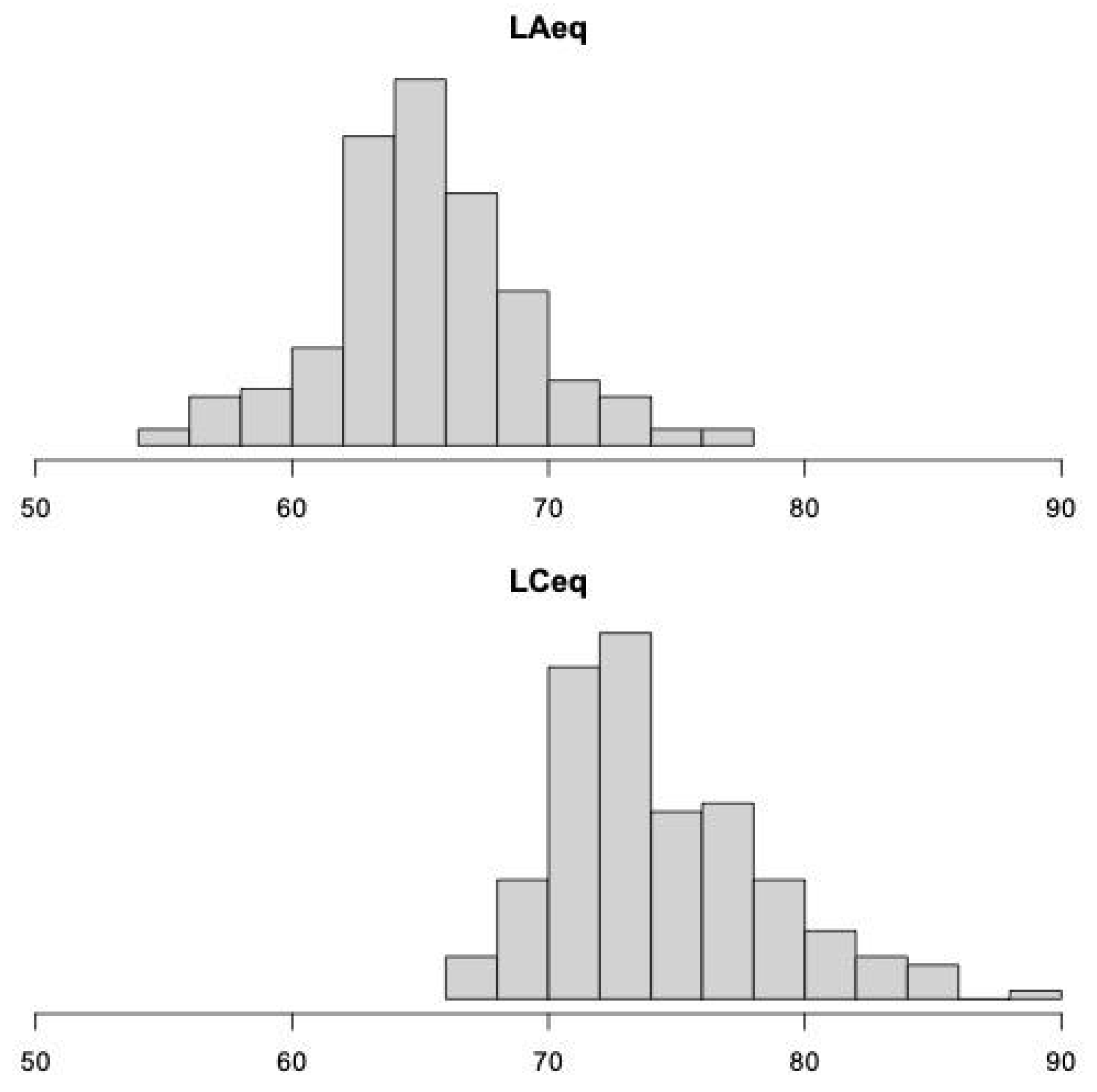

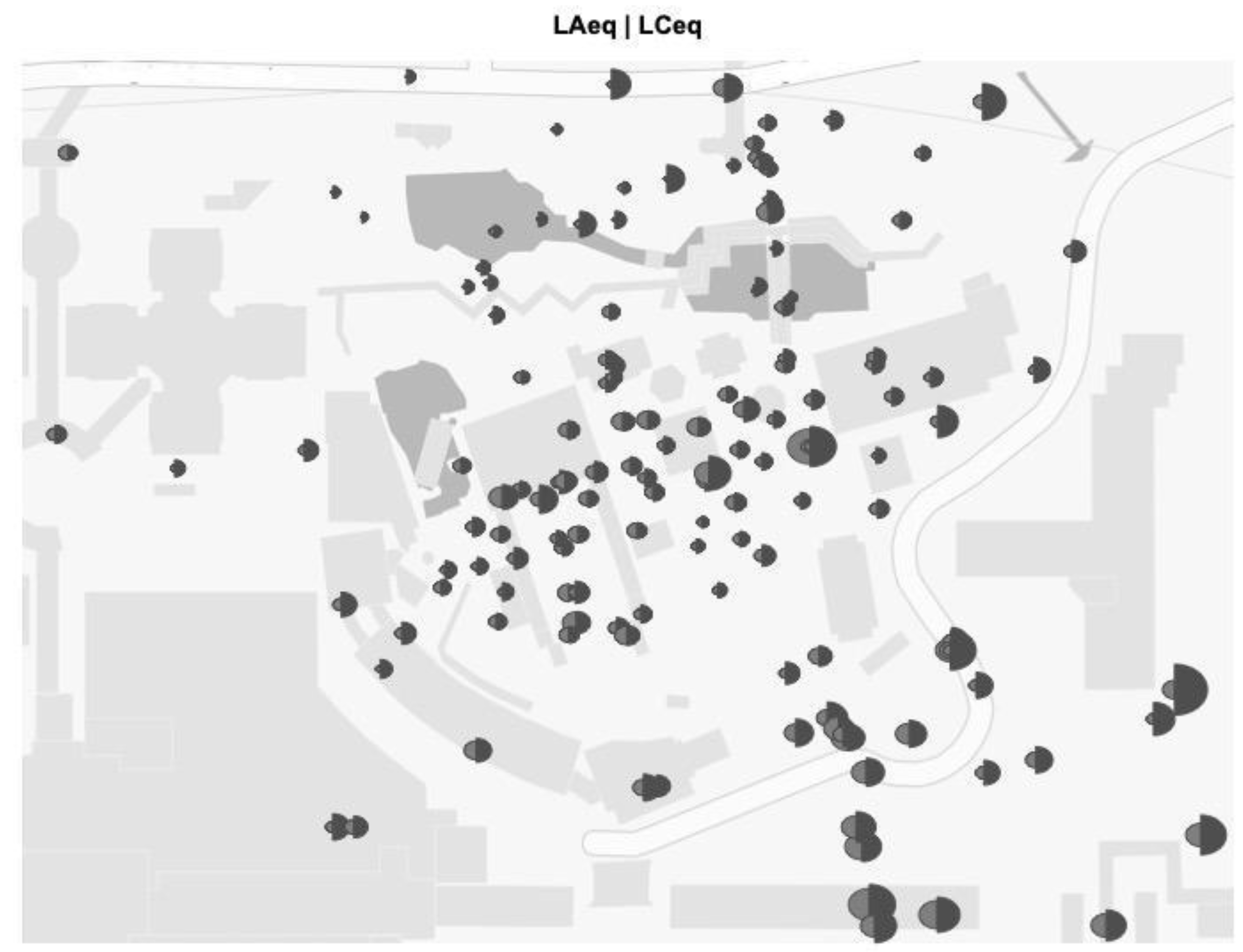

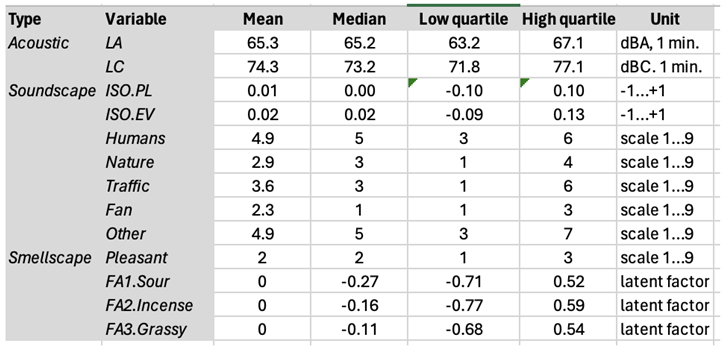

3.2. Acoustic Measurements

3.3. Soundscape Ratings

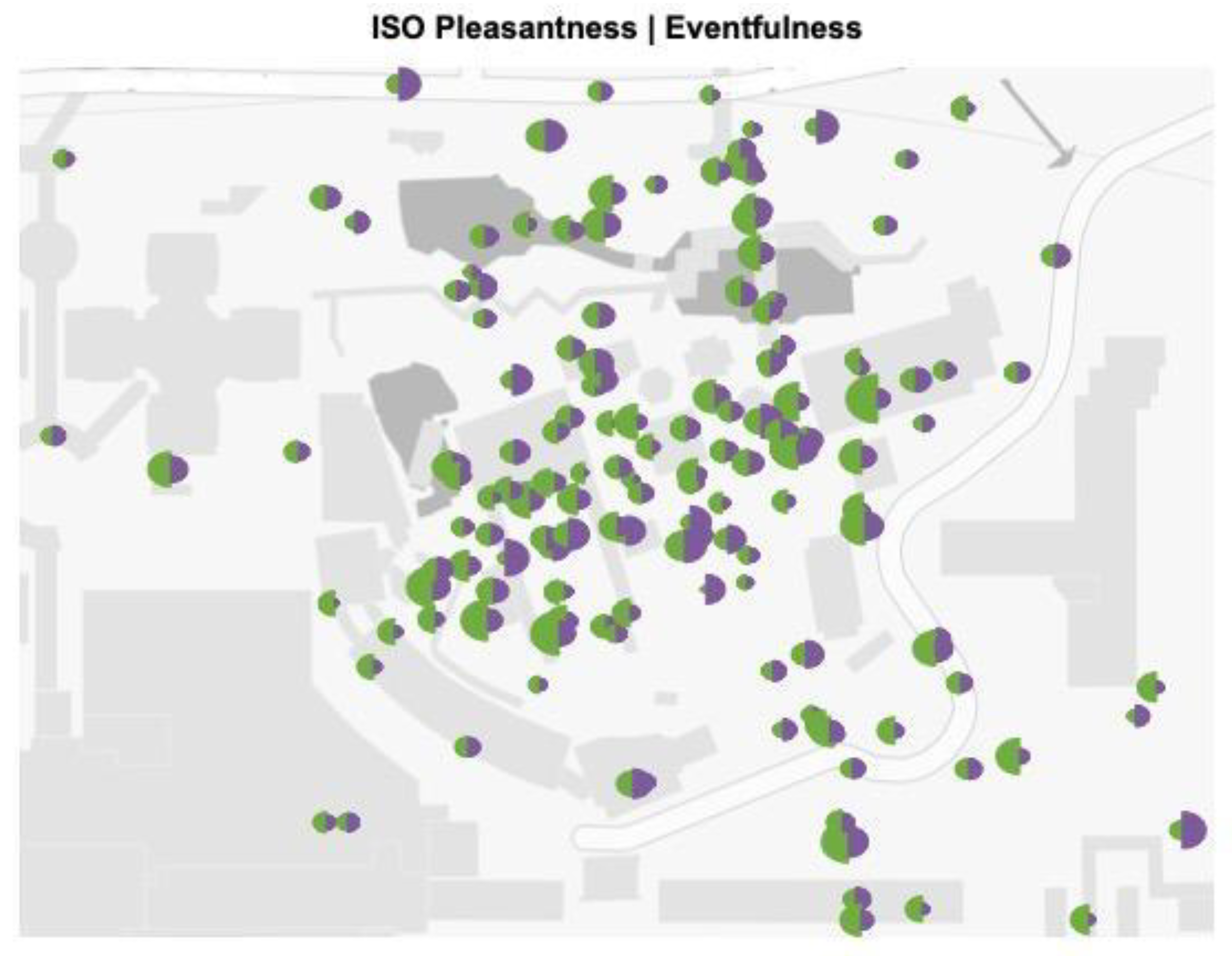

3.3.1. Pleasantness-Eventfulness

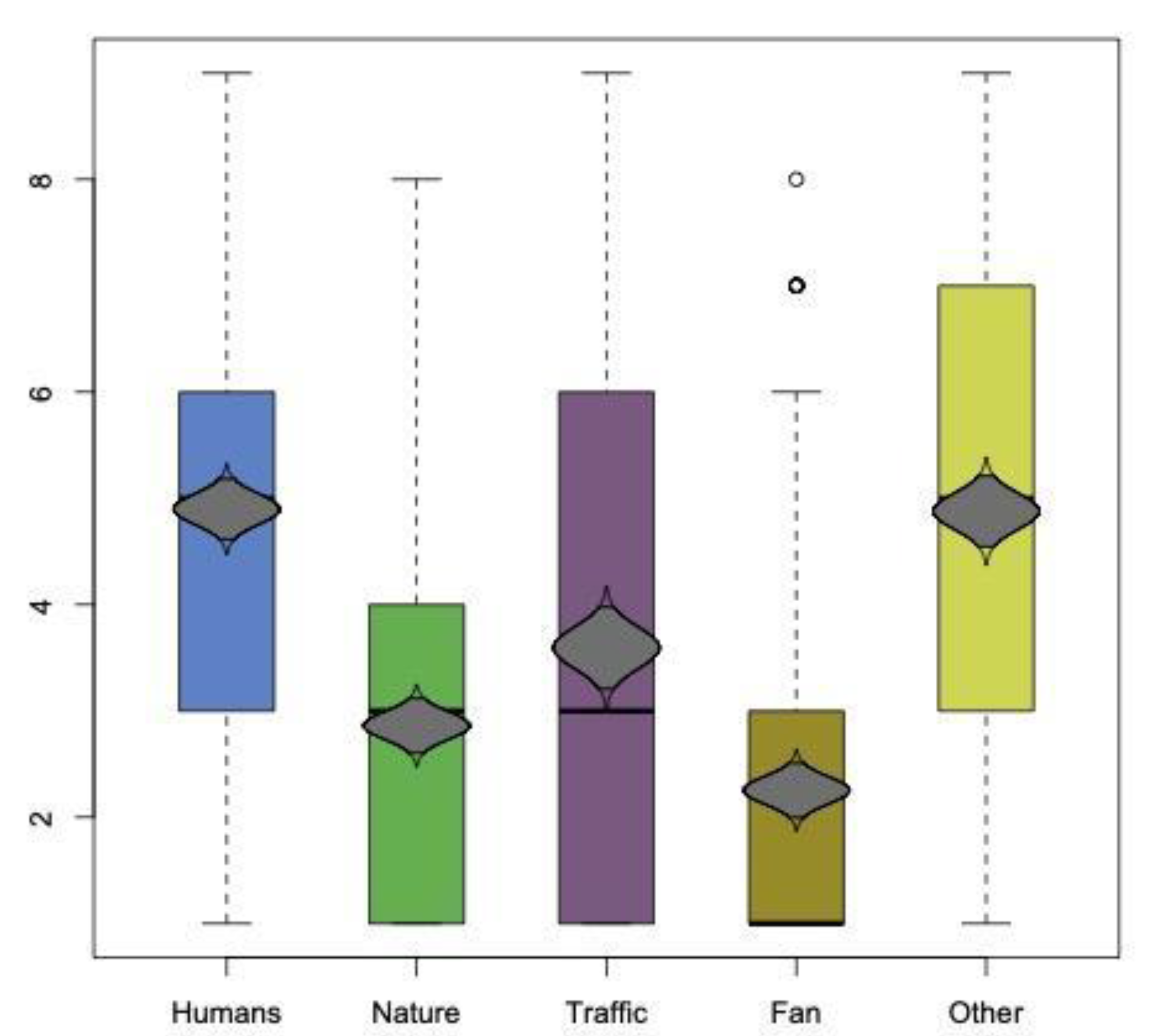

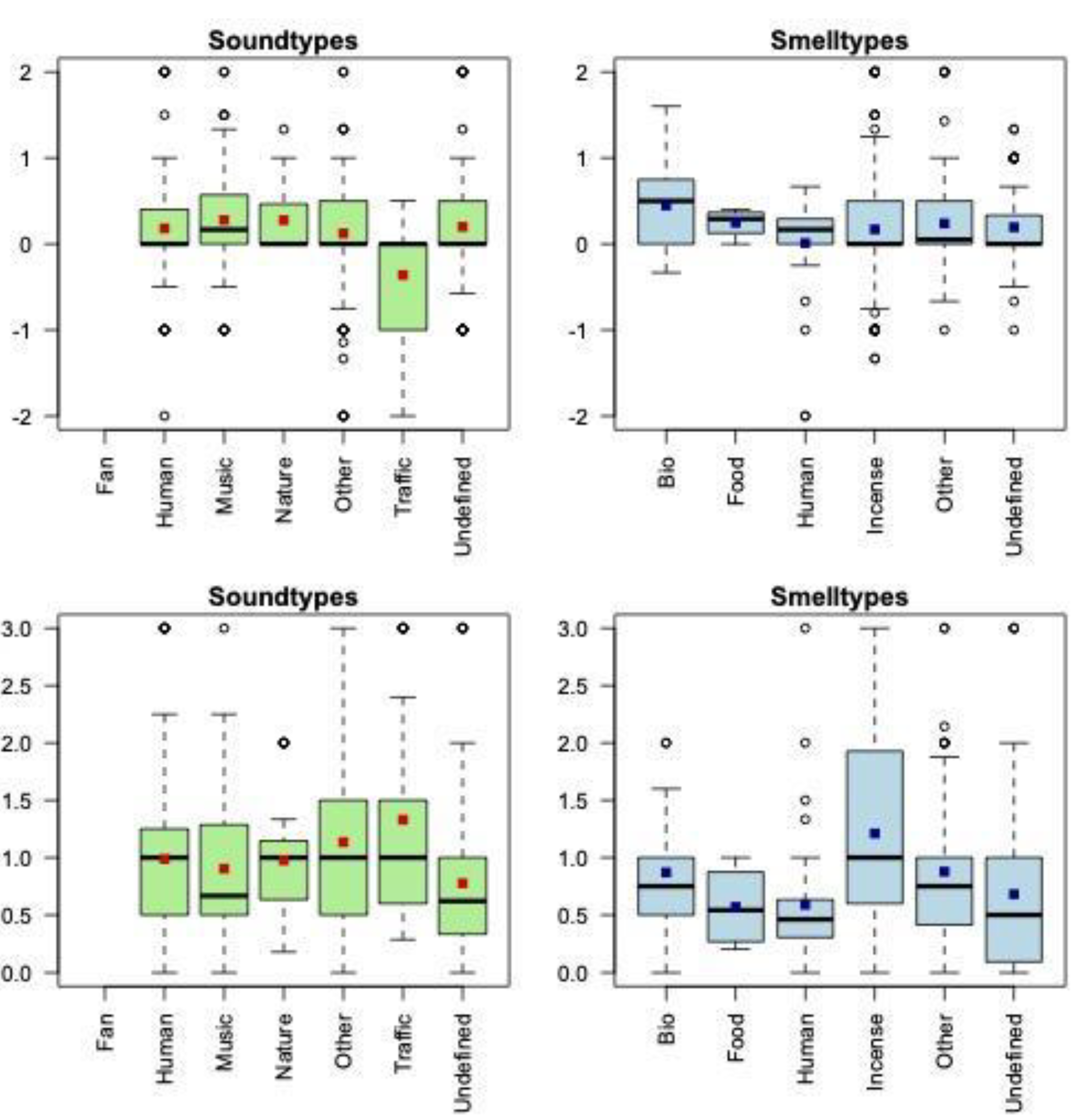

3.3.2. Sound Type

3.4. Smellscape Ratings

3.5. Interviews

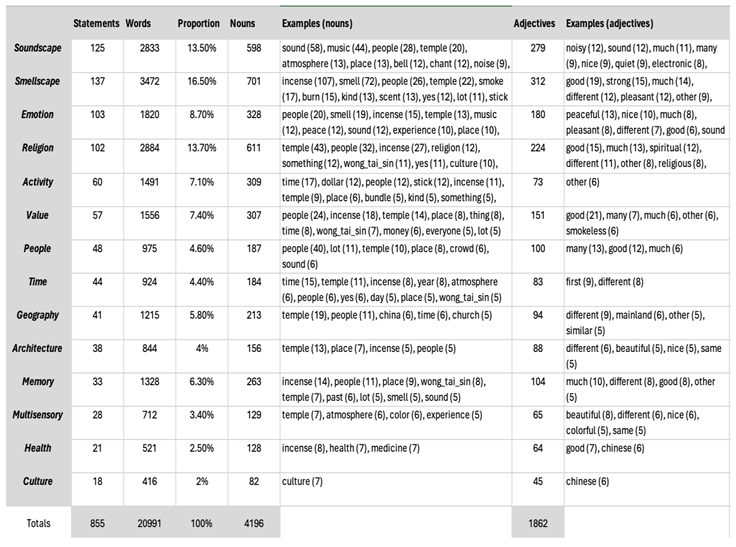

3.6. Thematic Analysis

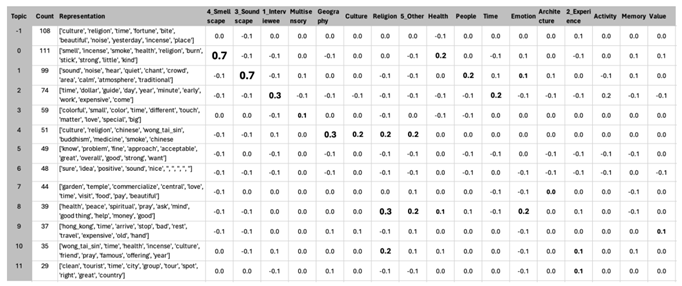

3.7. Topic Modelling

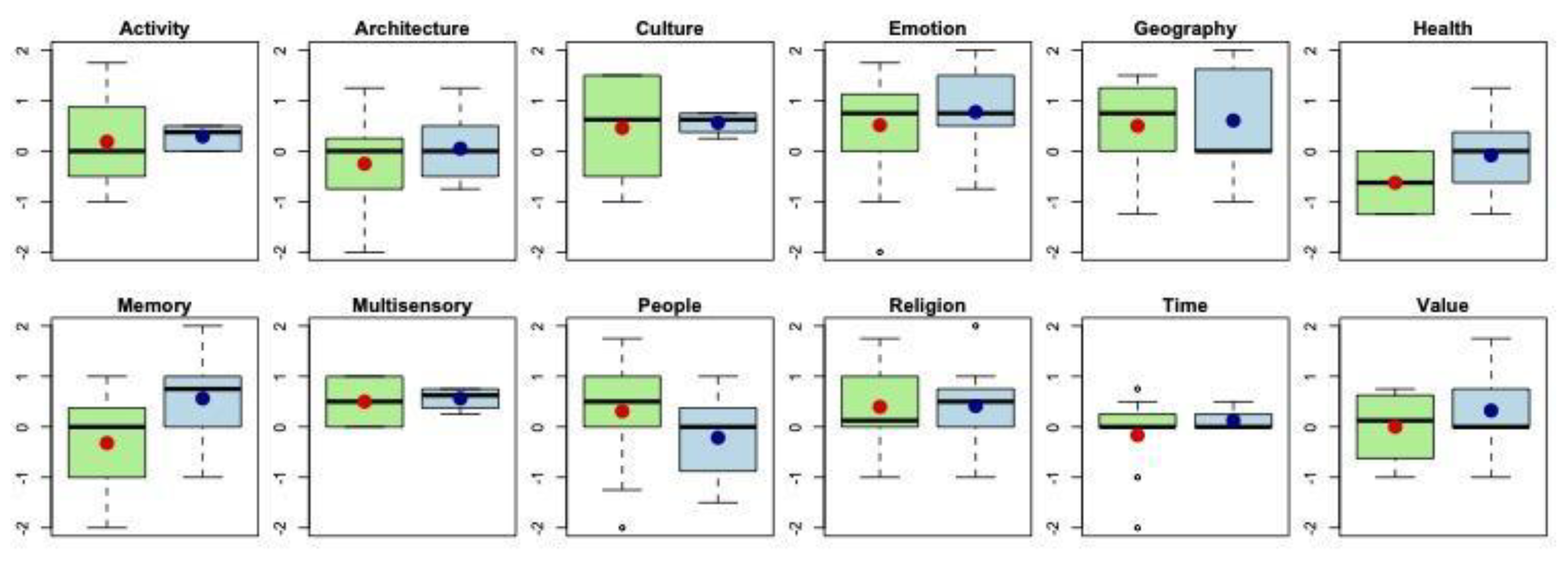

3.8. Content Analysis

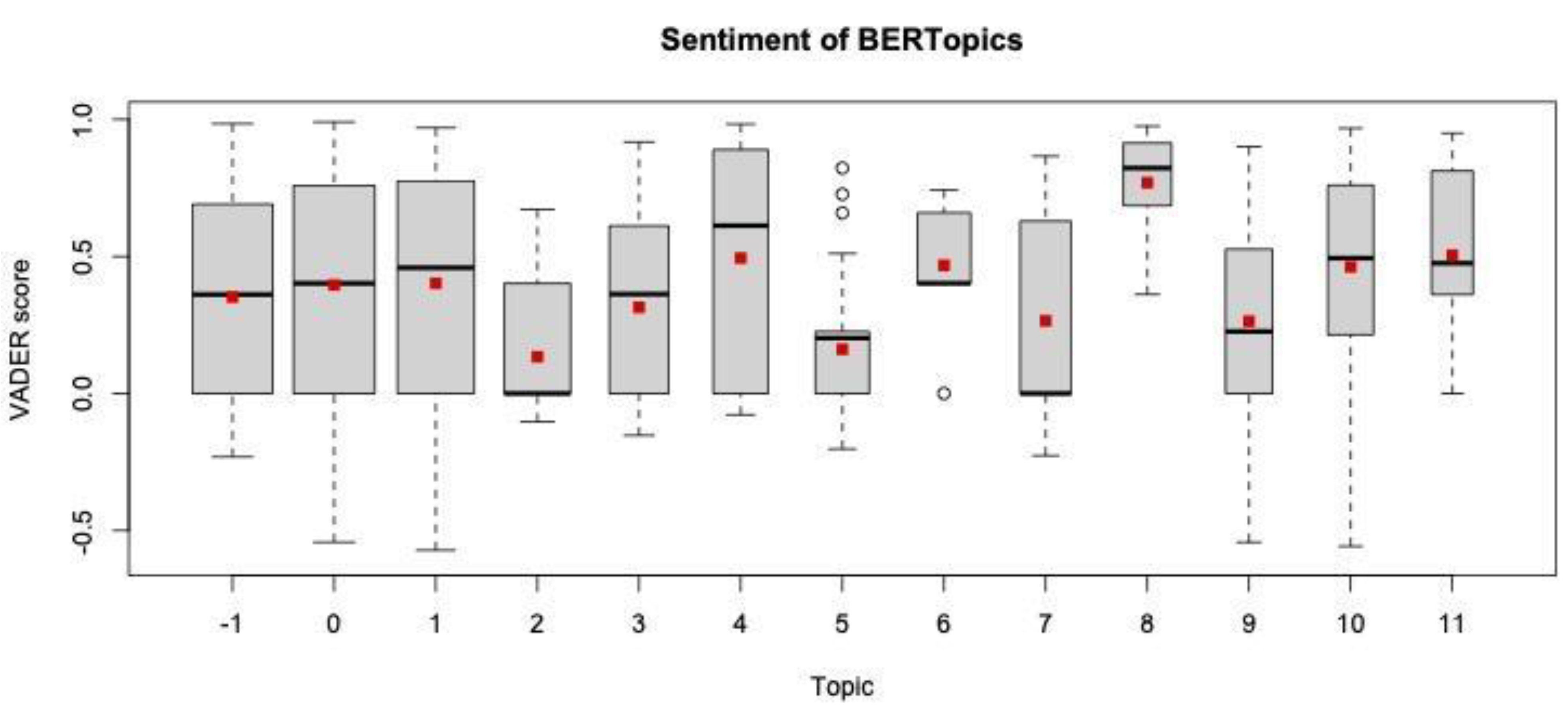

3.8.1. Sentiment Analysis

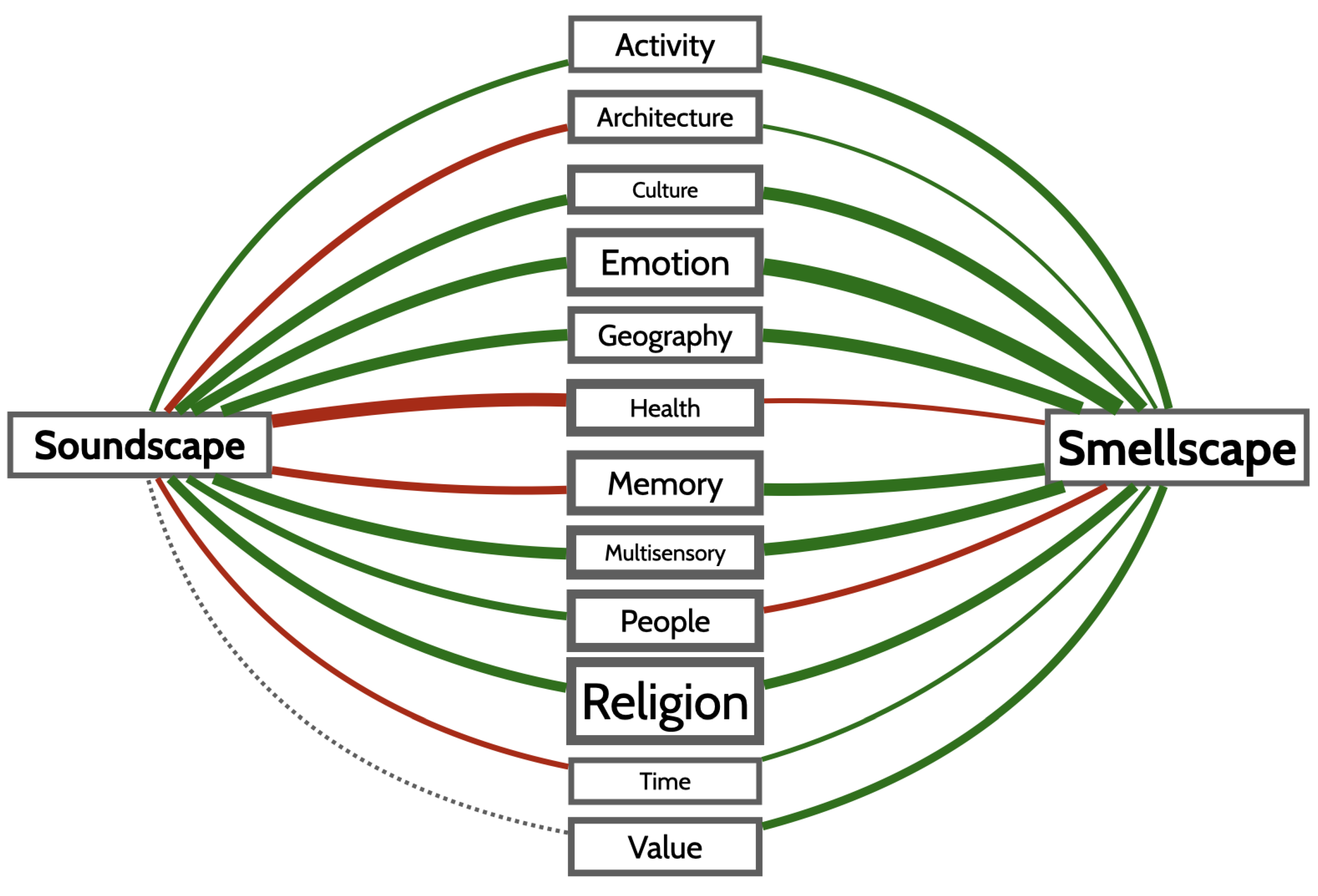

3.8.2. Summarising Conceptual Analysis

4. Discussion

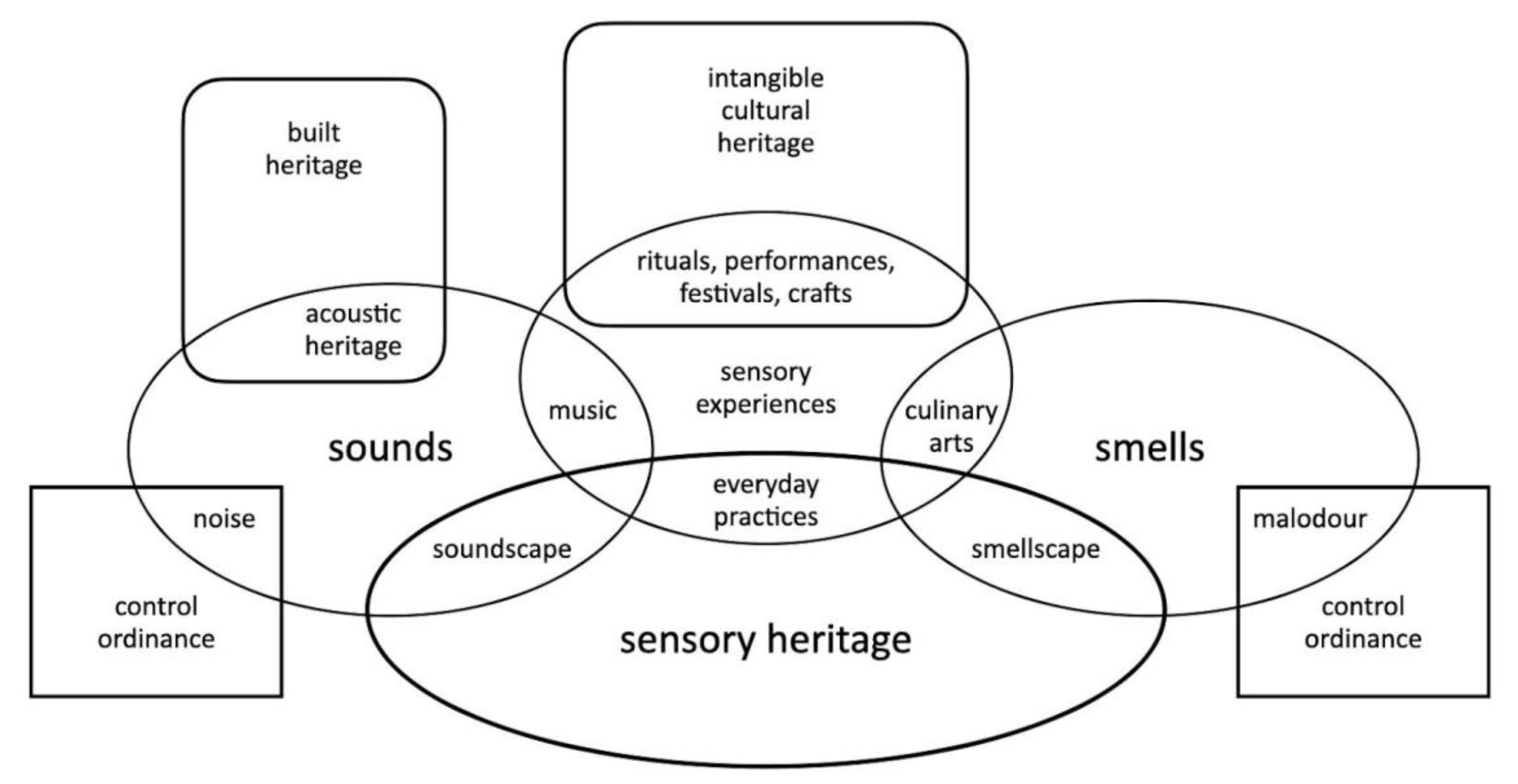

4.1. Sensory Heritage

4.1.1. Sounds of Nature and Music

4.1.2. People

4.1.3. The Smell of Religion

4.1.4. Identity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Aletta, F.; Mitchell, A.; Oberman, T.; Kang, J.; Khelil, S.; Bouzir, T.A.K.; Berkouk, D.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; et al. Soundscape Descriptors in Eighteen Languages: Translation and Validation through Listening Experiments. Applied Acoustics 2024, 224, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, Ö.; Nilsson, M.E.; Berglund, B. A Principal Components Model of Soundscape Perception. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2010, 128, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgiorno, V.; Naddeo, V.; Zarra, T. Odour Impact Assessment Handbook; Wiley Online Library, 2013; ISBN 1-119-96928-X.

- Bembibre, C. Olfactory Heritage: Opportunities for Policymaking. Presented at the Sensory Dimensions in Heritage and Beyond: Exploring Soundscapes and Smellscapes, 2024.

- Cai, W.H.; Wong, P.P.Y. Associations between Incense-Burning Temples and Respiratory Mortality in Hong Kong. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dravnieks, A.; Masurat, T.; Lamm, R.A. Hedonics of Odors and Odor Descriptors. Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association 1984, 34, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 Relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise - Declaration by the Commission in the Conciliation Committee on the Directive Relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise; 2002; Vol. 189;

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural Topic Modeling with a Class-Based TF-IDF Procedure 2022.

- Guo, T. “Gods Feast on Holy Smoke, Not Tear Gas!” Religious Diffusion, Infrapolitics, and Identity Formation in Hong Kong. The Journal of Asian Studies 2024, 83, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, V. Urban Smellscapes: Understanding and Designing City Smell Environments; Routledge, 2013; ISBN 1-135-10096-9.

- Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance - Home Available online:. Available online: https://www.epd.gov.hk/eia/en/index.html (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Hong Kong Government Cap. Available online: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap400?xpid=ID_1438403155721_001 (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Hong Kong Government Chinese Temples Ordinance; 1997.

- Hong Kong Observatory Hong Kong Observatory Open Data. Available online: https://www.hko.gov.hk/en/abouthko/opendata_intro.htm (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. Vader: A Parsimonious Rule-Based Model for Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Text. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media; 2014; Vol. 8, pp. 216–225.

- ISO 12913-1: 2014 Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework 2014.

- ISO 12913-2: 2018 Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 2: Data Collection and Reporting Requirements 2018.

- ISO 12913-3: 2019 Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 3: Data Analysis 2019.

- Lam, L.H.; Lindborg, P.; Aletta, F.; Wong, P.P.Y.; Yue, R. Multimodal Hong Kong: A Review of Policies Regarding Soundscape and Smellscape of Chinese Temples.; 2024.

- Lam, L.H.; Yue, R.; Kam, Y.; Lindborg, P. Perceptions of Chinese Temples through Soundscape and Smellscape: A Case Study at Wong Tai Sin. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Forum Acousticum - Euronoise; Spain, June 2025.

- Lenzi, S.; Sádaba, J.; Lindborg, P. Soundscape in Times of Change: Case Study of a City Neighbourhood During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Frontiers in psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindborg, P.; Aletta, F.; Xiao, J.; Liew, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Yue, R.; Jiang, Q.; Lam, L.H.; Wei, L. Multimodal Hong Kong: Documenting Soundscape and Smellscape at Places of Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 53rd International Congress & Exposition on Noise Control Engineering (INTER-NOISE 2024): from Jules Verne’s world to multi-disciplinary approaches for Acoustics & Noise Control Engineering; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lindborg, P.; Friberg, A. Personality Traits Bias the Perceived Quality of Sonic Environments. Applied Sciences 2016, 6, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindborg, P.; Liew, K. Real and Imagined Smellscapes. Frontiers in psychology 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T. A Nameless but Active Religion: An Anthropologist’s View of Local Religion in Hong Kong and Macau. The China Quarterly 2003, 174, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malzer, C.; Baum, M. A Hybrid Approach to Hierarchical Density-Based Cluster Selection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE international conference on multisensor fusion and integration for intelligent systems (MFI); IEEE; 2020; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- McGinley, C.M.; McGinley, M.A. Odor Testing Biosolids for Decision Making. Proceedings of the Water Environment Federation 2002, 2002, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction 2020.

- Meik Michalke; Earl Brown; Alberto Mirisola; Alexandre Brulet; Laura Hauser koRpus v0.13-8 (Package for R) 2021.

- Mitchell, A.; Oberman, T.; Aletta, F.; Erfanian, M.; Kachlicka, M.; Lionello, M.; Kang, J. The Soundscape Indices (SSID) Protocol: A Method for Urban Soundscape Surveys—Questionnaires with Acoustical and Contextual Information. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R.; Bond, J. Sensory Perception in Cultural Studies—a Review of Sensorial and Multisensorial Heritage. The Senses and Society 2023, 19, 231–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, H.M.; Nusselder, R.J. Quiet Areas, Soundscaping and Urban Sound Planning. European Network of the Heads of Environment Protection Agencies (EPA Network). Interest Group on Noise Abatement (https://environnement. public. lu/content/dam/environnement/documents/bruit/quiet-areas-soundscaping-urban-sound-planning. pdf 2021.

- Porteous, J.D. Smellscape. Progress in Physical Geography 1985, 9, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ppali, S.; Pasia, M.; Wolf, S.; Han, J.; Muntean, R.; Yoo, M.; Rodil, K.; Berger, A.; Papallas, A.; Ciolfi, L.; et al. Sensing Heritage: Exploring Creative Approaches for Capturing, Experiencing and Safeguarding the Sensorial Aspects of Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2024 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, July 1, 2024; pp. 445–448. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Version 4.4.0 2025.

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings Using Siamese BERT-Networks 2019.

- Roehrick, K. Vader: Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner (VADER). R Package Version 0.2. 1 2020.

- Sik Sik Yuen Intangible Cultural Heritage Affairs of WTS Beliefs and Customs. Available online: https://www2.siksikyuen.org.hk/en/cultural-affairs/intangible-cultural-heritage-affairs-of-wong-tai-sin-beliefs-and-customs (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- To, W.M.; Mak, C.M.; Chung, W.L. Are the Noise Levels Acceptable in a Built Environment like Hong Kong? Noise Health 2015, 17, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective. In Philosophy in Geography; Theory and Decision Library; SpringerLink, 1977; Vol. 20, pp. 387–427.

- Wang, B.; Lee, S.C.; Ho, K.F.; Kang, Y.M. Characteristics of Emissions of Air Pollutants from Burning of Incense in Temples, Hong Kong. Science of the total environment 2007, 377, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J. Smell, Smellscape, and Place-Making: A Review of Approaches to Study Smellscape. In Handbook of research on perception-driven approaches to urban assessment and design; IGI Global, 2018; pp. 240–258.

- Xu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Smith, B. China’s Emerging Legislative and Policy Framework for Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage. International Journal of Cultural Policy 2022, 28, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, R.; Lindborg, P.; Lam, L.H.; Lin, A.; Kam, Y. Perceptions of Chinese Temples through Soundscape and Smellscape: A Case Study at Wong Tai Sin. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Forum Acousticum - Euronoise; Spain, June 2025.

- Zarzo, M. Multivariate Analysis and Classification of 146 Odor Character Descriptors. Chemosensory Perception 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).