1. Introduction

Bio-architecture has historically drawn inspiration from natural forms and processes through biomimicry. Janine Benyus (1997) defined biomimicry as the “conscious emulation of life’s genius” [

1], emphasising the value of learning from nature to devise design solutions. In recent years, there has been growing recognition that architecture must transcend the visual domain and engage the other senses (sound, touch, smell, and so forth) [

2]. In this context, architects and designers have increasingly turned their attention to the sonic dimension of space — a paradigmatic shift that invites us to ask “how built environments should sound like, not just how they should look” [

2,

3].

Moreover, the past decades have witnessed a rising interest in soundscapes within the fields of design and architecture. The discipline of acoustic ecology, established by R. Murray Schafer in the 1970s, highlighted the dominance of a “culture of the eye” in contemporary society and the consequent erosion of our auditory competence—that is, the ability to consciously listen to the environment [

4]. Schafer advocated for the appreciation of the sonic environment and introduced the concept of the soundscape, framing the acoustic world as an integral part of both the ecosystem and human experience [

4]. Since then, research in sound ecology has demonstrated that sound plays essential roles in the behaviour of organisms and in the functioning of ecosystems [

5]. Many animals rely on acoustic signals for communication, navigation, and reproduction, such that noise pollution can disrupt critical ecological interactions [

6].

In parallel, studies involving human communities have revealed that the quality of the soundscape directly influences psychological well-being. Natural soundscapes, for instance, promote relaxation and restoration, whereas excessive urban noise contributes to stress, irritability, and a range of health issues [

7]. In short, sound and environment are intrinsically connected, and this understanding has gradually begun to inform planning and design practices.

Despite this broader outlook, there remains a gap in both research and practice concerning what might be termed bioacoustic design. Bio-architecture and nature-inspired design movements, such as biomimetics and biophilic design, have traditionally focused on morphological, visual, and material aspects of nature [

2]. Seminal works such as Benyus’s

Biomimicry (1997) and Wilson’s

Biophilia (1984) emphasised learning from natural forms, processes, and patterns in order to apply them to technology and architecture [

8,

9]. Likewise, biophilic projects have often prioritised elements such as natural light, vegetation, water, and organic textures, features that primarily engage sight and touch. Sound, however, continues to occupy a secondary role in these initiatives, while much of contemporary architecture remains designed “for the eyes”, neglecting the non-visual senses, including hearing [

2].

Thus, the potential to integrate nature-inspired acoustic principles, a central aspect of bioacoustic design, remains largely underexplored. This gap is particularly relevant because incorporating the sonic dimension can enrich both the environmental and personal experience of users, while also producing measurable benefits. In other words, there is a valuable opportunity to extend the scope of bio-architecture beyond visual aesthetics and functionality by incorporating nature’s sensory performance, such as sound, as a design element capable of fostering well-being and nurturing a sense of natural connection between users and the built environment.

It is within this context that the present investigation proposes and explores three principles of bioacoustic design in bio-architecture:

The principle of integrating or attracting natural sounds into architecture investigates how built environments might enhance interactions between human and non-human species. The proven health benefits of natural sounds by amplifying positive feelings and reducing negative ones support the notion of sonic biophilia. As discussed by Buxton et al. [

7], when listening to natural elements such as water and birdsong evoke adaptive responses in the human organism, with demonstrably positive effects on well-being and stress reduction.

Kang [

10] argues that sound should be addressed positively in urban design — not merely by controlling noise, but by actively designing high-quality soundscapes. An experimental installation at RMIT

i University (Australia) exemplifies the use of sound as a biophilic catalyst within the urban realm.

The Sonic Gathering Place (

Figure 1) integrates ambisonic

ii recordings of Australian biomes with native plant species arranged around circular seating, creating an immersive experience that does not suppress urban sounds, but rather complements them [

11]. Post-occupancy evaluation revealed measurable benefits: 95% of visitors identified a high restorative potential in the installation, while 65% reported an improvement in mood following the visit, based on comparative self-assessment [

11]. These results highlight the capacity of sound to amplify the positive effects of nature within the built environment.

Such evidence reinforces the potential of sonic biophilia as a design strategy; by incorporating natural soundscapes into buildings and urban spaces, it is possible to bring people closer to nature, support local biodiversity, and promote health and psychophysiological comfort [

7,

11].

The principle of displaced sonic memory, in turn, is grounded in the idea of transporting soundscapes from one place to another through recording technologies, in order to evoke affective memories and cultural connections across distinct environments. The underlying premise is that certain sounds possess strong cultural and emotional ties to specific communities and ecosystems — what Schafer termed

soundmarks, emblematic acoustic signatures of a place, analogous to landmarks in the construction of local identity [

4].

Research into historical soundscapes has shown that non-visual elements such as sound contribute to a place’s sense of authenticity and identity, anchoring people to its past [

13]. For instance, a study

iii conducted in historical districts proposed the inclusion of traditional or local sounds as strategies to reinforce the feeling of “being in place” and to enhance perceived authenticity of the urban experience [

13]. In this sense, architects can take advantage of this by inserting sounds characteristic of certain regions or times within contemporary spaces, thus generating a sensory bridge between different geographical and/or temporal contexts. The

Sonic Gathering Place, previously discussed, also incorporates recordings of four biomes from other regions (South-Eastern Australia), establishing a connection between users of the space and the natural landscapes from which those sounds originate [

11].

The principle of multisensory inclusion emphasises that bioacoustic design can also be inclusive by converting or adapting auditory stimuli into other sensory modalities (tactile and visual) and by creating sound environments tailored to individuals with diverse sensory profiles or neurodivergent conditionsiv.

In such adapted environments, auditory alarms are complemented by strobe lights

v, doorbells activate visual signals rather than sounds, and vibrating floors or furniture enable users to “feel” sound through touch, making the presence of others or the rhythm of music and alerts perceptible via tactile cues [

14]. This approach also aligns with the principles of multisensory design discussed by Ranne [

15], who argues that the simultaneous stimulation of multiple senses, particularly when coherent, significantly enhances the clarity and quality of experience, thus fostering sensory inclusion in the built environment.

In this way, the sonic component of design can be enjoyed or perceived by all users, regardless of auditory limitations, while simultaneously enriching spatial experience across all senses. This multisensory perspective resonates with the growing trend towards designing more synaesthetic and equitable environments, where sound, vision, and touch complement one another to generate intuitive, safe, and engaging spaces [

2].

In this context, the paper proposes a conceptual framework for bioacoustic design in architecture, articulating these three principles discussed through a systematic review of the literature and a series of case studies. The strategies aim to incorporate the soundscape from various contexts, including the natural environment, into the built environment. These principles thus seek to demonstrate how sound, as a natural and experiential component, can be translated into design strategies that foster biodiversity, emotional connection between places, and sensory equity.

2. Methodology

This study followed a three-stage qualitative protocol that couples evidence gathering with design-oriented synthesis.

Stage 1 – Structured literature review. A systematic review was conducted across databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, focusing on topics related to bioacoustics, soundscape ecology, biomimetics, sensory architecture, and neurodiversity. The review included peer-reviewed articles, books, and relevant case documentation published between 2015 and 2025. Key concepts and natural processes involving sound were identified and categorised to inform design strategies.

Stage 2 – Development of design principles. Based on the ecological and sensory findings from the literature review, the second stage consisted of the formulation of three design principles. Each principle was derived from natural sound-related behaviours or mechanisms observed in ecosystems (e.g. acoustic communication, spatial orientation, sound-triggered responses), and reinterpreted in architectural terms. In addition to integrating, representing, and rendering the soundscape perceptible within architectural space, the proposed translations are not based merely in metaphor but in functional equivalence. Acoustic attributes (e.g., rhythm, frequency, amplitude) are treated as data streams that inform and modulate spatial parameters, including geometry, movement or lighting.

The three proposed principles — Sonic Biophilia, Translocated Sound Memory and Multisensory Sonic Inclusion — were conceptually structured by identifying the biological or ecological phenomenon, its perceptual and behavioural implications, architectural correlations; and criteria for design integration and responsiveness.

Stage 3 – Case study validation. Representative case studies were selected to illustrate and validate each principle, based on their alignment with the proposed strategies and availability of documentation. Examples include Sonic Gathering Place (Australia), Rain Vortex (Singapore), Voice Tunnel (United States), Entfernte Züge (Germany), Fragments of Extinction (Italy), Ecoacoustic Theatre (Italy), and Sound Forest (Sweden). These were analysed in terms of acoustic materiality and integration, and multisensory design features.

3. Bio-acoustic Design Principles

3.1. Sonic Biophilia

The first principle emerges from the articulation between the concept of biophilia and the foundations of acoustic ecology. It proposes that the built environment should integrate natural visual and material elements and also actively and responsively incorporate the sounds emanating from those elements. This approach consists of recognising sound as an indicator of ecological vitality, understanding that certain natural environments, such as gardens and water features, produce soundscapes that positively influence users’ emotional, physiological, and cognitive states. In this context, architecture does not merely accommodate nature; it listens to it and amplifies it, providing a feedback loop between natural sounds and human behaviour.

To enable such integration, it is necessary to conduct, during the diagnostic phase of the design process, a detailed analysis of the existing soundscape at the site. This analysis allows for a deeper understanding of the quality and composition of the acoustic environment, distinguishing, for example, the proportion between natural sounds (such as animal vocalisations and running water) and anthropogenic sounds (such as human interactions, traffic, or urban machinery). Such data are important for identifying opportunities to enhance local acoustic biodiversity and for informing more effective design decisions. To this end, the participation of a multidisciplinary team, including architects, biologists, and soundscape specialists, is essential during this stage.

Based on such data, the architectural intervention may be conceived as a symbiotic mediator, both visually and aurally. Elements such as vegetation attractive to birds, insects, and small mammals — strategically selected to promote vocal diversity and continuous presence — can be incorporated into the design, alongside hydrological structures that produce variable sound profiles (e.g., dripping, continuous flow, turbulence), depending on material, geometry, and seasonal variations in the hydrological cycle.

This approach is exemplified by interventions such as The Sonic Gathering Place, discussed earlier, where the intentional integration of local vegetation and pre-recorded natural sounds produced measurable restorative effects in the urban environment.

Complementarily, the

Rain Vortex (

Figure 2), located in the Jewel Changi Airport in Singapore, stands as the world’s tallest indoor waterfall, reaching 40 metres in height and visually integrating with the central atrium of the building [

16]. Beyond its aesthetic value, the continuous presence of falling water also contributes acoustically to the spatial experience, functioning as an element capable of reshaping the soundscape within an intensely artificial environment [

17]. Studies indicate that high-flow waterfalls are capable of producing substantial low-frequency output — comparable to that of urban traffic noise — and that, when their sound level is close to or slightly above ambient noise, they can help to mask undesirable sounds [

17]. Although sound pressure levels remain high in the presence of water, perception of tranquillity has been shown to increase, not only due to physical masking, but also as a result of the distracting effect of natural sounds characterised by low sharpness and high temporal variability [

17]. The case of the

Rain Vortex demonstrates that sound-generating natural elements can be integrated as functional acoustic devices, enhancing users’ psychophysiological comfort and enriching the auditory experience in highly artificial settings.

In design terms, sonic biophilic integration may also require the use of digital tools that associate dynamic environmental parameters with architectural morphology. In this regard, acoustic sensors connected to machine learning systems capable of interpreting natural sound patterns and converting them into spatial adaptation commands may be employed. For instance, the dominant frequency of the local soundscape may be used to control kinetic devices such as louvres or movable panels, in order to intensify shading, promote cross-ventilation, or regulate the amount of sound entering the built space. This approach establishes a condition of continuous responsiveness between the natural environment and the architecture, whereby the site’s soundscape is harnessed to modulate aspects of environmental comfort and the dynamic behaviour of architectural form.

In the case of a project conceived in symbiosis with the natural environment — moving beyond the mere insertion of plants and water into space — it is important to emphasise that the viability of this strategy depends on specific structural and temporal factors. The implementation of a living sonic ecosystem requires time for birds and other animals to recognise the site as habitat or migratory route. Nonetheless, this limitation can be mitigated through the strategic selection of local species with rapid growth and short seasonal cycles.

3.2. Translocated Sound Memory

The second principle is based on the premise that sound can serve as a mediator of emotional connections between people and places, even when displaced from its original context. Rather than limiting itself to the appreciation of local soundscapes, as in more conventional approaches, this principle proposes a more narrative strategy by integrating sounds from other territories or ecosystems as a means of evoking collective memories, activating symbolic associations, and stimulating synaesthetic experiences.

This involves using architectural space as a medium for reproducing sounds that carry symbolic value — such as the noise of an endangered ecosystem, the ritual song of a community, or the soundscape of a distant territory — and allowing them to be re-experienced in an immersive, sensitive, and critical manner.

This intentional displacement of soundscape can occur through high-fidelity environmental recordings, digitally processed using algorithms that extract temporal and spectral patterns in order to generate visual, tactile, or spatial stimuli aligned with their spectral characteristics. Rather than simply reproducing background sounds, the design functions as a system of translation in which acoustic patterns — such as rhythm, frequency, intensity, or timbre — are analysed and transformed into design parameters such as light modulation, geometric variation, or the programming of kinetic elements that physically respond to fluctuations in the original acoustic signal. This enables sound to be materialised in a non-literal way, becoming a sensitive and interpretative architectural experience in which space becomes a means of expressing sound memory.

An example that illustrates this approach is the installation

Voice Tunnel (

Figure 3), by artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, presented in the Park Avenue Tunnel in New York City during the 2013 Summer Streets event.

The installation transformed a traffic tunnel, ordinarily closed to the public, into an immersive, voice-responsive corridor where recordings of urban speech from various city neighbourhoods were broadcast through a sound system distributed along the space. Simultaneously, visitors were invited to speak into a microphone positioned at the entrance of the tunnel, with their voices captured in real time to modulate the intensity of 300 LED

vi lights spread throughout the corridor [

18,

19]. The lights pulsed in direct response to the participants’ voices, creating a synaesthetic environment [

19,

20]. This spatial reconfiguration created a kind of “interactive sound skin,” whereby the urban acoustic landscape became a means of individual and collective expression, expanding the symbolic density of the site beyond its physical materiality [

20].

Another application lies in interventions focused on historical and environmental memory. The installation

Entfernte Züge [

22] consists of the transposition of soundscapes from the

Köln Hauptbahnhof railway station to the ruins of the

Anhalter Bahnhof in Berlin, Germany, (

Figure 4), which, according to the artist, seemed to be “haunted” by the absent sounds of trains and crowds. The work reconfigures the site as a space of sound evocation, where the memory of movement and urban life is recovered not visually, but through listening.

Similarly, the projects

Fragments of Extinction and the

Ecoacoustic Theatre [

23] demonstrate how endangered soundscapes, such as those of disappearing tropical forests, can be translated into immersive installations that preserve and amplify the listening experience of remote ecosystems. Architecture, in this context, becomes a space for empathic and pedagogical activation [

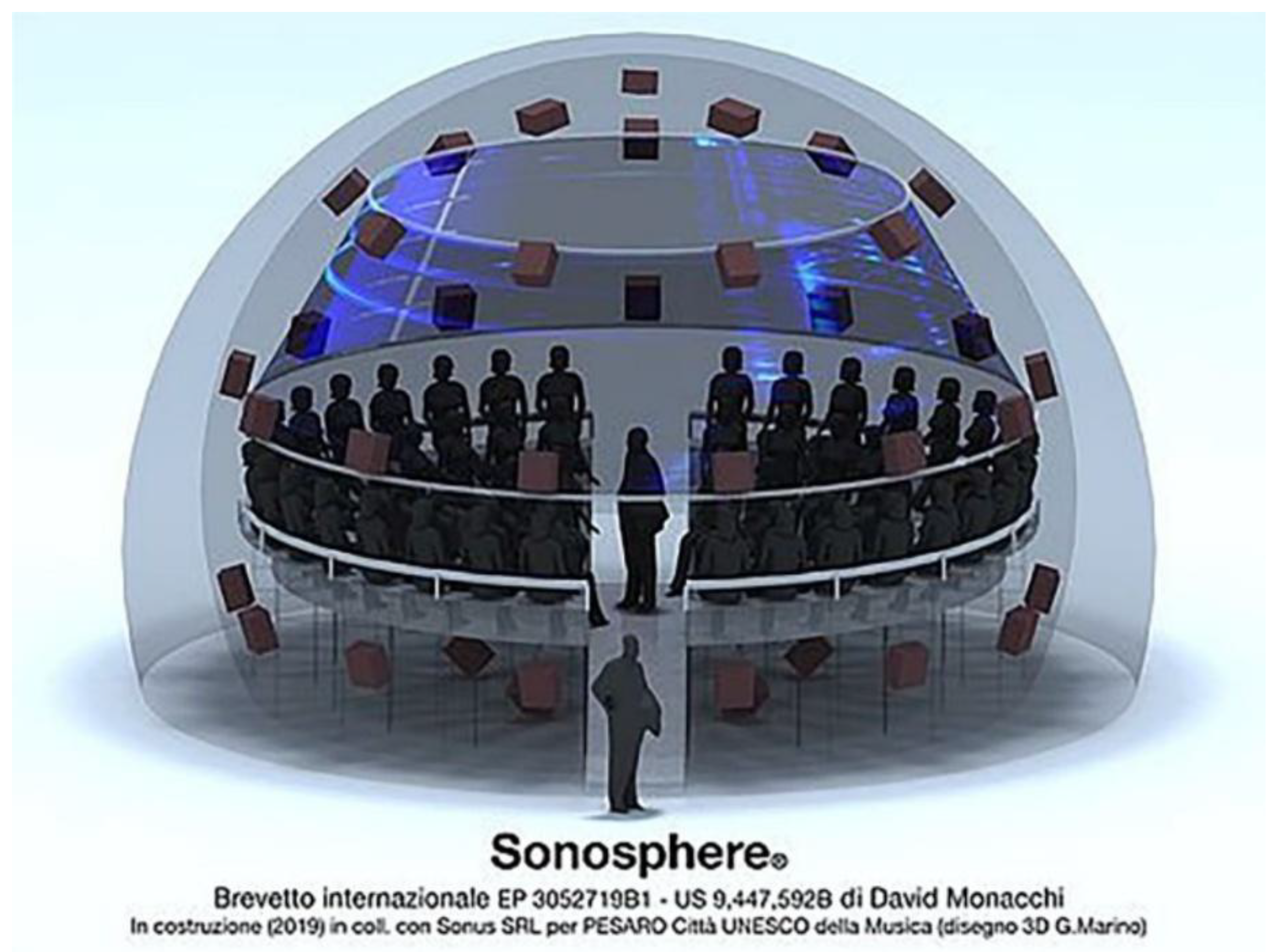

25]. In a comparable way, the Italian installation

Sonosphere, conceived as a fully immersive eco-acoustic theatre, offers a similar sensory experience by spatially projecting high-fidelity recordings of natural habitats. The hemispherical structure, equipped with 45 loudspeakers distributed around the audience and beneath the floor, enables the accurate reproduction of 360° soundscapes (

Figure 5) [

26].

This design principle can be particularly effective in contexts of memory preservation, endangered cultures, or identity reconstruction, in which the original sounds of a community may be kept alive within public or interior spaces, such as exhibitions. By making audible — or visible and tactile — what would otherwise be absent or forgotten, the project promotes a kind of expanded listening, in which memory is not merely presented as acoustic information, but as an environmental experience.

3.3. Multisensory Sonic Inclusion

The third principle expands upon the biophilic approach by recognising that listening to the environment is a kind of sensory connection with the natural world, but that this experience must remain accessible even to those who do not perceive sound in a conventional manner. This involves extending the concept of sonic biophilia beyond hearing, treating sound as a multisensory stimulus capable of being perceived through other senses, thus making the built environment more inclusive and responsive to the sensory diversity of its occupants. In this context, the sounds of nature are understood as a means of belonging and emotional regulation that should be democratised through design.

Spaces designed from this perspective consider, for example, deaf or hard-of-hearing users, as well as neurodivergent individuals with sensory hypersensitivities (as often found in the autistic spectrum), and indeed any user who interacts with space through different modes of attention and reception.

The fundamental strategy consists in converting or transducing

vii sound waves into alternative modes of sensory stimulation, a principle observable in nature, where various organisms convert pressure variations into mechanical signals (e.g., fish detect vibrations in water through their lateral line

viii, and spiders perceive subtle disturbances on their webs [

27,

28]). Technologically, this translation can be achieved through materials and systems that physically respond to the properties of sound, such as its frequency or intensity, and transform this information into vibratory or visual patterns. Advances in smart materials have enabled, for instance, the use of piezoelectric polymer membranes

ix or piezoelectric ceramics

x that selectively vibrate in response to specific acoustic spectra. When applied to architectural surfaces (e.g., floors, walls, or furniture), such vibrations become tactile and perceptible to the touch, allowing sound to be physically felt by those who cannot hear it.

In parallel, the visualisation of sound can be achieved through responsive lighting systems, in which spectral variations are translated into changes in colour, light intensity, or movement sequences. By combining both strategies (vibration and light) it becomes possible to synchronise stimuli of different natures, creating synaesthetic experiences. Ensuring coherence between the modes of stimulation is essential to maintain perceptual clarity and avoid sensory overload, particularly for individuals with specific hypersensitivities.

This principle is exemplified by the installation

Sound Forest, located at the Swedish Museum of Performing Arts (

Scenkonstmuseet) in Stockholm (

Figure 6). The project presents a multisensory immersive environment composed of interactive vertical strings that emit both sound and light, combined with circular platforms mounted on a raised floor. Each platform is equipped with tactile transducers

xi that allow visitors to feel the music through vibrations transmitted to their feet. The platforms respond to physical interactions with the strings by triggering multisensory feedback such as airborne sound, light, and haptic

xii response are synchronised. The installation explores music as a bodily experience, promoting the perception of vibration through various parts of the body and enabling audiences with different sensory profiles to access the sound composition through alternative means [

29].

When applied to everyday architectural settings, this approach calls for a revision of traditional criteria related to environmental comfort and wayfinding. For instance, audible alarms may be complemented by pulsing visual stimuli or localised vibrations; doorbells may trigger light-based rather than acoustic signals; and interactive floors and surfaces may convey rhythmic or spatial information through tactile means. Sound thus ceases to be an isolated datum and instead becomes part of an expanded sensory communication network.

When this principle is applied to bio-architecture, it acknowledges that the sounds of nature are not merely to be contemplated but to be felt through multisensory engagement. This implies a change in the way of designing, as it is not a matter of isolating noise or controlling sound as a pollutant, but of cultivating it as a stimulus that can be interpreted by different sensory channels.

Although each principle has been presented individually based on conceptual frameworks and practical examples, the methodological logic guiding their formulation may be synthesised comparatively.

Table 1 below organises the ecological mechanisms, perceptual effects, architectural correspondences, and operational criteria associated with each principle.

4. Discussion

This research proposes a repositioning of sound as a central element in the bioinspired and biophilic design process, overcoming traditional approaches that treat it only as environmental noise or a secondary variable to be mitigated. Through the development of the principles of Sonic Biophilia, Translocated Sound Memory, and Multisensory Sonic Inclusion, the aim was to demonstrate how soundscapes can operate as design matter — ecological, cultural, and perceptual — expanding the scope of architectural biomimicry from the morpho-functional domain to the sensory and ecological, and redefining biophilia beyond the mere incorporation of plants and water to include the sound dimension.

With regard to Sonic Biophilia, the research highlights the value of natural soundscapes as indicators of environmental quality and psychophysiological well-being. Ecological studies underscore the essential role of audible sound stimuli in maintaining habitat quality and interspecies interaction.

Sonic Biophilia, however, builds upon this understanding by treating natural sounds not as mere decorative background elements, but as indicators of ecological vitality, whose presence can actively reduce stress, restore attention, and enhance comfort. These effects are exemplified in the cases of The Sonic Gathering Place and Rain Vortex, where, respectively, the attraction of wildlife and the presence of the waterfall heighten the perception of tranquillity and facilitate the masking of persistent and intense noise.

Furthermore, sonic biophilic integration should not be mistaken for decorative landscaping or artificial sound ambience. Rather, it entails establishing an active and responsive relationship between nature and architecture, grounded both in the ecology of place and in the auditory experience of the user. By recognising sound as a legitimate component of the biophilic repertoire, this principle expands the boundaries of bio-architecture by proposing that spaces should not only look like nature but also sound like it and adapt to it, thus deepening the direct connection with natural elements and enhancing sensory engagement.

However, this responsive approach, in which the environment listens and reacts to the acoustic context in real time, requires the integration of sensing, processing, and actuation systems

xiv. Thus, tools such as high-precision sensors, machine learning algorithms, and artificial intelligence may be employed to adjust spatial conditions according to captured and processed sound data. This sound reciprocity echoes Benyus’s [

8] notion of the “conscious emulation of nature’s genius”, while also opening new pathways for ecological interactivity in architectural design.

The second principle, Translocated Sound Memory, is anchored in research on sonic heritage and acoustic ecology, recognising that certain sounds carry strong emotional, historical, and cultural significance. Literature on soundmarks emphasises their role as cultural markers as meaningful as visual landmarks. Building upon this understanding, the principle proposes the use of architecture as a support for immersive acoustic experiences that recreate or relocate soundscapes from distant geographic contexts.

Cases such as Voice Tunnel demonstrate the potential of public spaces to incorporate recorded soundtracks that function as living sensory archives. Similarly, works like Entfernte Züge and the Ecoacoustic Theatre exemplify the transposition of historical soundscapes and endangered ecosystems, respectively, into built contexts, where they operate as devices for environmental education and empathic activation.

In sum, this principle proposes that the transposition of soundscapes may serve as a design strategy capable of carrying meaning, fostering emotional bonds, restoring collective identities, and reconstituting the acoustic memory of territories undergoing transformation.

However, implementing this principle requires not only the careful curation of the soundscapes to be recreated, but also the integration of immersive and responsive technologies that enable their incorporation into the built environment. This entails the use of tools such as ambisonic recordings (which capture sound in 360°) to register the acoustic atmosphere of a given soundscape with spatial precision. When reproduced through multichannel systems strategically distributed throughout the architectural space, these recordings create a sense of immersion. Acoustic spatialisation algorithms control the direction, distance, and movement of sound sources, synchronising them with visual and/or tactile stimuli when desired.

The third principle, Multisensory Sonic Inclusion, stems from a critique of the dominance of sight as the predominant sense in architectural practice. It advocates for the translation of sound into visual and tactile stimuli, thereby broadening access to the soundscape for individuals with diverse sensory profiles. This proposal is not restricted to accessibility for deaf or hard-of-hearing individuals; it equally addresses the need of neurodivergent users, the elderly, and anyone who wish to engage with space through synaesthetic perception.

Projects such as Sound Forest illustrate current technological possibilities for creating surfaces that respond to sound data through light patterns or localised vibrations. This complex translation of sonic stimuli into vibration, even when produced by high-resolution transducers, tends to convey only general aspects of sound, such as rhythmic pulses or intensity, without capturing subtle nuances such as birdsong. Similarly, the conversion of sound into light often results in simplified abstractions, incapable of reproducing the full perceptual richness of sound. Nonetheless, such representations, even when not faithful in detail, can still provoke meaningful sensations.

Nevertheless, implementation requires technical care; vibration thresholds must be calibrated to convey nuances without causing discomfort for hypersensitive individuals, and light patterns must be synchronised with sufficient precision to represent rhythms or intensities in an intelligible manner. Moreover, genuine inclusion demands iterative testing and co-design with target user groups to ensure that sensory translations are both functional and meaningful.

For this multisensory approach to be truly responsive and aligned with the sensory diversity of users, it is essential to integrate a coordinated set of acoustic sensors, programmable controllers, and sensory actuators. The system begins with the capture and processing of sound to extract acoustic properties such as frequency, intensity, and rhythm. These data are processed in real time by microcontrollersxv (e.g., Arduino boards), which interpret the sound patterns and convert them into commands that activate lights, vibrations, or changes in physical elements of the space, such as the opening of movable panels or the movement of architectural components. For instance, vibratory floors equipped with piezoelectric transducers may pulse in synchrony with incoming sound frequencies.

5. Conclusions

This paper outlines some strategies for integrating sound into architecture from a bioinspired perspective, focusing on the articulation between soundscapes, human well-being, ecology, and sensory accessibility. Through the development of the principles of Sonic Biophilia, Translocated Sound Memory, and Multisensory Sonic Inclusion, the study establishes a theoretical framework for rethinking the role of sound as active design matter and for guiding integrative design practices.

It is important, however, to recognise certain limitations. The validation of these principles was based on case studies and literature review, without practical architectural experimentation or sensory analysis of real biophilic spaces. The absence of empirical measurements such as acoustic comfort assessments or perceptual impact evaluations involving users with diverse sensory profiles limits the direct verification of the proposed strategies.

Even so, these principles constitute an analytical framework from which new practical trials can generate testable design guidelines. In this regard, pilot studies and post-occupancy evaluations are useful for verifying, refining, and quantifying the impact of each principle within built environments.

This investigation repositions the soundscape as a biophilic resource in which architecture should embrace the sound of place, intervening to correct or enhance it only when it proves to be harmful to the environment and users. The articulation between biophilia and soundscape emerges as a strategy for promoting comfort, reducing stress, and positively impacting both physical and mental health.

In parallel, the recovery of historical and ecological soundmarks emerges as a pedagogical tool and a means of fostering environmental awareness. Whether through permanent interventions or temporary installations, the reintroduction of identity-bearing sounds strengthens cultural ties and stimulates ecological consciousness.

In addressing sensory diversity, it is essential that individuals with auditory hypersensitivity, hearing loss, or neurodivergent profiles have access to solutions that allow them to experience the soundscape in ways that align with their needs, whether through vibrations and/or synchronised visual feedback.

6. Notes

i RMIT: Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology

ii Ambisonics is a spatial audio technique that enables the capture and reproduction of sound with the aim of recreating a three-dimensional auditory perception. It employs spherical harmonic functions to simulate, immersively and dynamically, how the human ears interpret direction, distance, and spatial context [

11,

12].

iii The study by Hu

et al. [

13] identified culturally significant sounds such as conversations in regional dialects, street vendors’ calls, scenes from the daily life of local communities, folk activities, and traditional performances. These sounds were analysed across five historic districts in China: Dashilan (Beijing), Bund (Shanghai), Laodaowai (Harbin), Jianghan Road (Wuhan), and Shamian (Guangzhou).

iv Neurodivergent individuals exhibit neurological variations that diverge from the neurotypical norm (e.g., Autism, Dyslexia, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or Tourette’s syndrome). These variations are part of the natural diversity of the human brain and influence the ways in which people perceive, process, and interact with their environment.

v Strobe lights are light sources that flash at regular intervals, creating rapid intermittent visual effects. They are commonly used in artistic environments to produce visual stimuli.

vi LED (Light Emitting Diode) is a semiconductor device that converts electrical energy into light.

vii Transduction is the process by which one form of energy (e.g., sound, light, or motion) is converted into another; for instance, vibrations transformed into electrical signals or tactile stimuli.

viii Lateral line is part of the sensory system present in fish and aquatic amphibians like tadpoles [

27].

ix Piezoelectric polymer membranes are thin, flexible films made from polymeric materials (e.g., polyamides and polyesters), used in sensors, microphones, or loudspeakers due to their ability to vibrate or respond to stimuli [

30].

x Piezoelectric ceramics (e.g., Lead Zirconate Titanate) are ceramic materials that generate an electrical charge when subjected to mechanical pressure, and vice versa [

30].

xi Tactile transducers are devices that convert electrical signals into physical vibrations perceptible through the skin, enabling sound to be experienced as tactile stimuli —for example, through the sensation of rhythm, intensity, or musical pulse (e.g., virtual reality gloves and vibratory floors).

xii Haptic perception refers to the ability to recognise objects and textures through both active (movement) and passive (pressure) touch, allowing one to perceive the environment through touch, pressure, texture, and vibration.

xiii Multichannel systems consist of arrays of loudspeakers distributed throughout a space to enable the spatialized reproduction of sound. They provide immersive experience by directing different audio channels to specific positions, thereby simulating the origin and movement of sounds within the environment.

xiv Actuator devices are mechanisms capable of converting one type of energy into mechanical motion.

xv Microcontrollers are programmable integrated circuits capable of reading sensor inputs and controlling physical actuators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L.; methodology, E.L.; validation, E.L.; formal analysis, E.L.; investigation, E.L.; data curation, E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.; writing—review and editing, E.L.; supervision, L.M. and A.A.; funding acquisition, E.L. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financed by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the Strategic Project with the reference: UID/04008: Centro de Investigação em Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank FCT, the Foundation for Science and Technology under the PhD scholarship, reference

https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.02623.BD; and CIAUD, the Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, University of Lisbon.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zejnilović, E.; & Husukić, E. Biomimicry in architecture. International journal of engineering research and development 2015, 11, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C. Senses of place: architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cognitive research: principles and implications 2020, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aletta, F.; Astolfi, A. Soundscapes of buildings and built environments. Building Acoustics 2018, 25, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrightson, K. An introduction to acoustic ecology. Soundscape: The journal of acoustic ecology 2000, 1, 10–13, http://www.econtact.ca/5_3/wrightson_acousticecology.html. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, A., Mullet, T. C., Bazarbayeva, T. A., Tazhibayeva, T., Bulatova, D., & Li, P. Perspectives on the ecological role of geophysical sounds. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 9, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Pijanowski, B. C., Farina, A., Gage, S. H., Dumyahn, S. L., & Krause, B. L. What is soundscape ecology? An introduction and overview of an emerging new science. Landscape ecology 2011, 26, 1213–1232. [CrossRef]

- Buxton, R. T., Pearson, A. L., Allou, C., Fristrup, K., & Wittemyer, G. A synthesis of health benefits of natural sounds and their distribution in national parks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 2011; 308p. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E. O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: USA, 1984; 176p. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. Soundscape in city and built environment: current developments and design potentials. City and Built Environment 2023, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, J., Brown, A. L., & Anderson, C. Sonic Gathering Place: implementation of a biophilic soundscape design and its evaluation. Landscape Research 2025, 50, 110–128. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Duraiswami, R. Spheroidal ambisonics: Spatial audio in spheroidal bases. JASA Express Letters 2021, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y., Meng, Q., Li, M., & Yang, D. Enhancing authenticity in historic districts via soundscape design. Heritage Science 2024, 12, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Bauman, H. Gallaudet University. Gallaudet University DeafSpace Design Guidelines: Volume I (Working Draft). Personal communication, 2010.

- Ranne, J. Designing for Multi-sensory Experiences in the Built Environment. Master’s Thesis, Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Espoo, Finland, 2019. Aalto Repository. Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/items/39156ae2-b07b-4d87-92e1-41276a34d58d (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Tahmasebinia, F.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Ho, J.; Shen, W.; Ma, H.; Sepasgozar, S.M.E.; Marroquin, F.A. Advanced Structural Analysis of Innovative Steel–Glass Structures with Respect to the Architectural Design. Buildings 2021, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbrun, L.; Ali, T. T. 'Acoustical and perceptual assessment of water sounds and their use over road traffic noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2013, 133, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, L. Urban Interactive Installation Art as Pseudo-Environment Based on the Frame of the Shannon–Weaver Model. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Rauterberg, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12794, pp. 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dante. Voice Tunnel: Large-scale interactive art installation. n.d. Available online: https://www.getdante.com/resources/catalog/voice-tunnel-large-scale-interactive-art-installation/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Benivolski, X. Review of Building a Voice: Sound, Surface, Skin. 2025. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/notes/668450/review-of-building-a-voice-sound-surface-skin/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Tasnaphun, T. Voice Tunnel 02. 2013. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/40968098@N07/9442425304/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Fontana, B. The relocation of ambient sound: Urban sound sculpture. Leonardo 1987, 20, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monacchi, D.; Krause, B. Ecoacoustics and its expression through the voice of the arts: An essay. In Ecoacoustics: The Ecological Role of Sounds; Farina, A., Gage, S. H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2017; pp. 297-312. [CrossRef]

- Bundesarchiv. Berlin, Anhalter Bahnhof (frontal view). ca.1950. Available online: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_B_145_Bild-F003102-0010,_Berlin,_Anhalter_Bahnhof.jpg (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Bundesarchiv. Berlin, Anhalter Bahnhof (side view with ruins). ca.1950. Available online: https://pt.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_B_145_Bild-F003102-0006,_Berlin,_Anhalter_Bahnhof.jpg (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Pietroni, E. (2021). Mapping the Soundscape in Communicative Forms for Cultural Heritage: Between Realism and Symbolism. Heritage, 4(4), 4495-4523. [CrossRef]

- Bleckmann, H.; Zelick, R. Lateral line system of fish. Integrative zoology 2009, 4, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortimer, B. A spider’s vibration landscape: adaptations to promote vibrational information transfer in orb webs. Integrative and Comparative Biology 2019, 59, 1636–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frid, E.; Lindetorp, H. Haptic music: exploring whole-body vibrations and tactile sound for a multisensory music installation. In Proceedings of the Sound and Music Computing Conference, Turin, Italy, June 24th-26th 2020. https://hal.science/hal-04331822v1.

- Smith, M.; Kar-Narayan, S. Piezoelectric polymers: theory, challenges and opportunities. International Materials Reviews 2022, 67, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).