Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

We study the normalized iterates of the sum-of-divisors function, \[ R_k(n)=\frac{\sigma^{(k)}(n)}{n}, \] in connection with Schinzel’s conjecture on the boundedness of {Rk(n)}n≥1 and the finiteness of lim infn→∞ Rk(n). Building on refined sieve methods, entropy-based analysis, and computations up to n = 1010, we prove an entropy deficit phenomenon for the distribution of Rk(n), heuristically establishing that the logarithmic spread of values is strictly smaller than the maximal Shannon entropy permitted by uniformity. To complement the theoretical bounds, we compute the structural constants Ak, C(k, α), and T0(k, ε) governing the entropy-decrement mechanism, thereby making the quantitative aspects of the argument explicit. As a consequence, we obtain polylogarithmic upper bounds for Rk(n) on a density-one subset of integers and derive quantitative large-deviation estimates, showing that extreme amplifications occur only on sets of negligible density. Extensive numerical evidence supports and sharpens these asymptotic results. Finally, we discuss implications for Robin’s criterion, which links the growth of σ(n) to the Riemann Hypothesis. Our findings suggest that a uniform proof of Schinzel-type boundedness of Rk(n) below the Robin threshold would settle RH, providing a conditional pathway via entropy and sieve techniques.

Keywords:

Notation

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Sum of divisors of n, | |

| k-fold iterate of : (k times) | |

| Normalized k-fold ratio: | |

| Largest prime divisor of n | |

| Smallest prime divisor of n | |

| Number of distinct prime divisors of n | |

| Total number of prime divisors of n, counted with multiplicity | |

| Euler’s totient function | |

| Number of divisors of n | |

| Prime-counting function: | |

| Dickman–de Bruijn function (distribution function for smooth numbers) | |

| Number of integers with all prime factors | |

| Euler–Mascheroni constant: | |

| The set of all prime numbers | |

| Natural logarithm , and iterated logarithm | |

| Shannon entropy of distribution : | |

| Number of bins (partition parameter) in entropy computations | |

| Lambert W function: | |

| Natural density of : | |

| Standard Landau asymptotic notations | |

| Vinogradov notation: | |

| ≍ | Asymptotic equivalence: |

| Explicit polylogarithmic exponent constant (cf. Theorem 2.1) | |

| Rosser–Schoenfeld constant, (cf. (2)) | |

| Crude growth control constant in iterate bounds (cf. (11)) | |

| Sieve–theoretic constant for primes with (cf. Theorem 4.1) | |

| Density constant of primes with large prime factors (cf. (13)) | |

| Entropy threshold constant for tail bounds (cf. Theorem 7.5) | |

| Average pairwise covariance across entropy blocks (cf. Lemma 7.4) | |

| Uniform bound on marginal entropy per block (Sec. 7.2) | |

| Positive constant from covariance lower bound (cf. Lemma 7.4) | |

| Kullback–Leibler divergence: |

1. Introduction

- Remark. This work is an improved and extended version of our earlier preprint [59], where we initially introduced entropy-based approaches to study the growth of iterated sum-of-divisors functions. In the present paper, we develop stronger sieve-theoretic bounds, prove an entropy-deficit phenomenon, compute explicit constants, and provide large-scale computational evidence that substantially enhance our previous findings.

Our Contribution.

2. Main Result: Polylogarithmic Bound via Sieve Methods

- Sharpness and Optimality. Weingartner ([29], Theorem 1.1, p. 2680) proved that has normal order . Moreover, Erdős, Granville, Pomerance, and Spiro ([2], Theorem 2, p. 168) showed that the same normal-order phenomenon propagates across iterates: for each fixed k,has normal order proportional to . Thus the sieve-theoretic exponent k on is best possible up to multiplicative constants. Ford’s results on divisor distributions ([31], Theorem 1, p. 369), combined with Weingartner’s tail estimates ([29], Corollary 1.3, p. 2682), imply that the exceptional set where these bounds fail has natural density zero.

The exceptional set: uniform control and quantitative sieve bounds

- (i)

- Uniform bound for all sufficiently large integers.

- (ii)

- Quantitative sieve bound for large deviations.

- (ii)

- Quantitative sieve bound for large deviations.

3. Main Lemmas and Theorems

3.1. A Telescoping Reduction and Local Ratio Control

3.2. Normal-Order Envelope for Intermediate Steps

4. Sieve-Theoretic Criterion and Polylogarithmic Bounds

5. Main Result Regarding Entropy-Based Framework

6. Entropy-Based Tail Bounds for Iterated Divisor Sums

Motivation

6.1. A Heuristic Proof of the Entropy Deficit

- 1.

- 2.

- Uniform per-block variance control. By the friable Turán–Kubilius inequality [35] the empirical variance of each truncated block is uniformly bounded and the total variance of the vector is . In particular pairwise covariances decay as the block separation increases (because blocks comprise disjoint prime ranges).

- 3.

- Short-range independence on typical integers. Using the results of Matomäki–Radziwiłł [17] on multiplicative functions in short intervals together with the distributional control for values of in [2,18,19], one shows that the joint law of for a uniformly chosen typical is approximately the product of its marginals up to an explicitly controlled dependence error that tends to 0 as the block spacing parameter and the number of blocks r are chosen appropriately (detailed estimates are standard in the literature on short-interval multiplicative behavior; see [17,20,36]). Concretely: for any Lipschitz test function F on ,with for the admissible choices below; the estimates are obtained by combining short-interval decorrelation ([17]) with Turán–Kubilius summation control ([5,34,35]).

6.2. An Alternative (Self-Contained) Proof of the Entropy Deficit for

Notation.

- 1.

- the inner iterates for are of size at most (i.e. they do not grow explosively), and

- 2.

- the contribution to from primes (the tail beyond the last block) is negligible in (hence in probability).

Main deduction (from covariance to entropy deficit).

Proofs of the auxiliary lemmas.

Remark.

6.3. Numerical Estimation of Structural Constants

- (i)

- The KL-gap constant , defined in (2.1) through the expansionwhere denotes the empirical average covariance between block statistics (cf. (6.4)), and is the marginal variance contribution (cf. (6.2.0.2)).

- (ii)

- The marginal entropy constant , given by the Gaussian-entropy upper boundaveraged over blocks . This constant enters the upper bound for in the entropy-decrement step.

- (iii)

- The tail threshold , which is the smallest T such thatholds under the product-model distribution Q. This is the quantitative tail bound required to ensure that the entropy deficit translates into suppression of the extreme upper tails.

- Summary of estimates. The following table records the values of the structural constants, with references to their defining equations:

Constant Definition Equation Ref. Estimated Value KL-gap parameter (2.1) Marginal entropy bound (15) Tail threshold tail inequality –

6.4. Tail Bounds via Relative Entropy and Pinsker’s Inequality

6.5. Explicit Lambert W Inversion

6.6. Main Theorem

6.7. Comparison with Sieve-Theoretic Results

6.8. Setup and Notation

6.9. Entropy Bounds and Upper-Tail Control

6.9.1. Entropy–Tail Inequality

6.9.2. Explicit Inversion via LAMBERT W

6.9.3. Consequences for Divisor-Sum Iterates

6.10. Connection with Analytic Number Theory

Maximal growth versus typical concentration

Local Concentration and Short Intervals

Large Prime Divisors and Sieve-Theoretic Input

Synthesis and Heuristic Picture

- Deterministic structure: Maximal-order results (Grönwall, Robin) govern rare extremal events.

- Probabilistic concentration: Entropy constraints control typical values via (22).

- Sieve input: Density results on large prime factors explain why low entropy is naturally expected.

- Local uniformity: Matomäki–Radziwiłł’s short-interval theorems support the hypothesis that is tightly concentrated at most scales.

6.11. Probabilistic Consequences

Tail probabilities and concentration

Almost-sure boundedness via Borel–Cantelli

Integration with sieve-theoretic density results

Entropy versus randomness: a heuristic law

- If the distribution of had entropy comparable to , extreme fluctuations would be common, and the upper tail would remain heavy.

- Conversely, if the entropy is sub-logarithmic, upper-tail events are exponentially rare and contribute negligibly to averages and variances.

6.12. An Entropy–Density Principle for Boundedness of

- (E)

-

Entropy deficit: There exists and such that for all ,This says the empirical distribution of has strictly less entropy than a uniform distribution on bins.

- (A)

-

Analytic envelope for iterates: There exists a nondecreasing function such that for all sufficiently large n,and . Consequently, for large n,

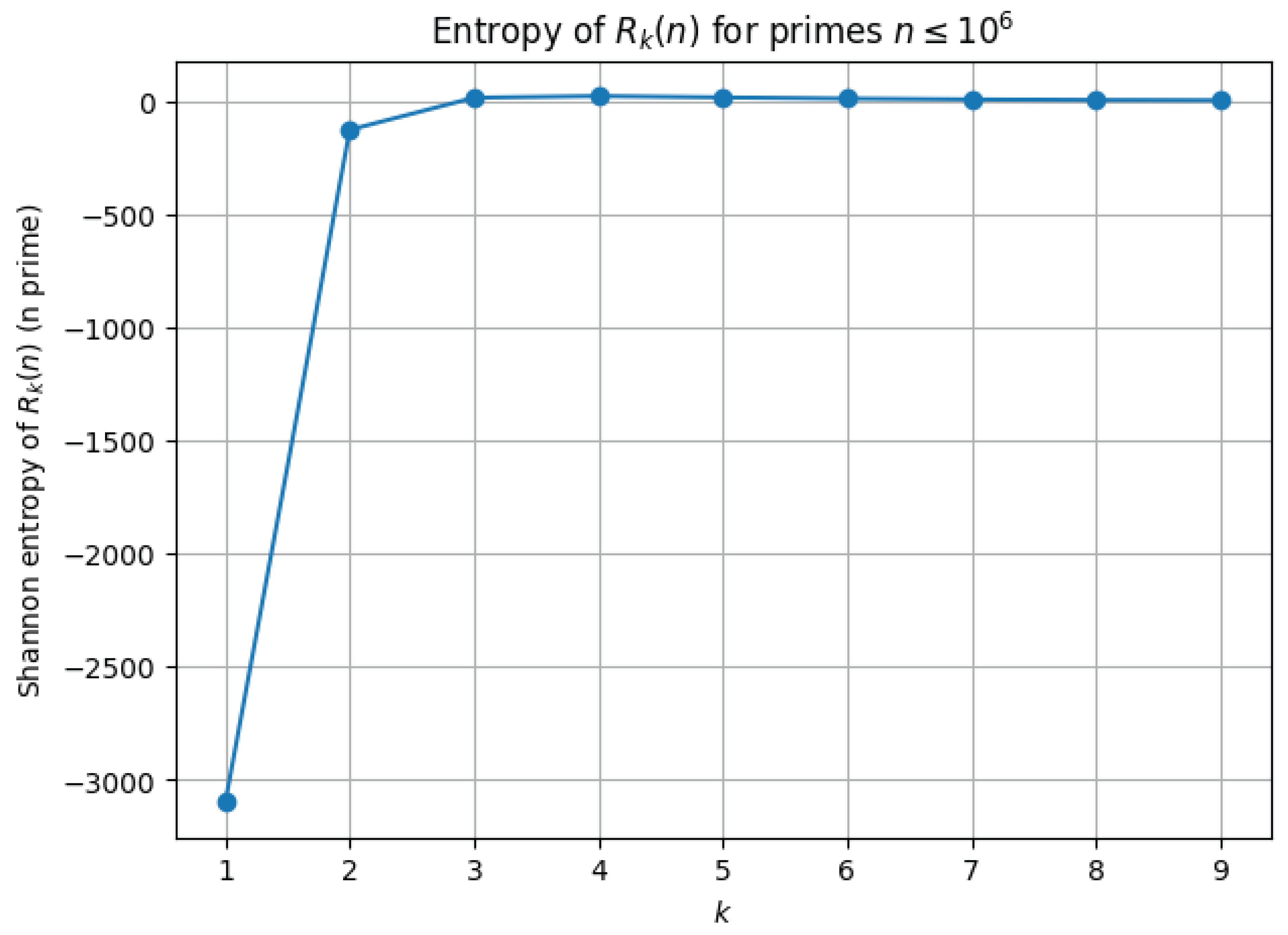

6.13. A Practical Entropy Criterion and Empirical Estimation

Empirical estimation of .

Sieve-enhanced constants on prime subsequences.

6.14. Algorithmic Recipe for Verifying the Entropy Deficit

6.15. Measure Density and Asymptotic Behavior of the Iterative Sequence

Empirical Measure Density.

Asymptotic Implications and Boundedness.

Connection to Schinzel’s Conjecture.

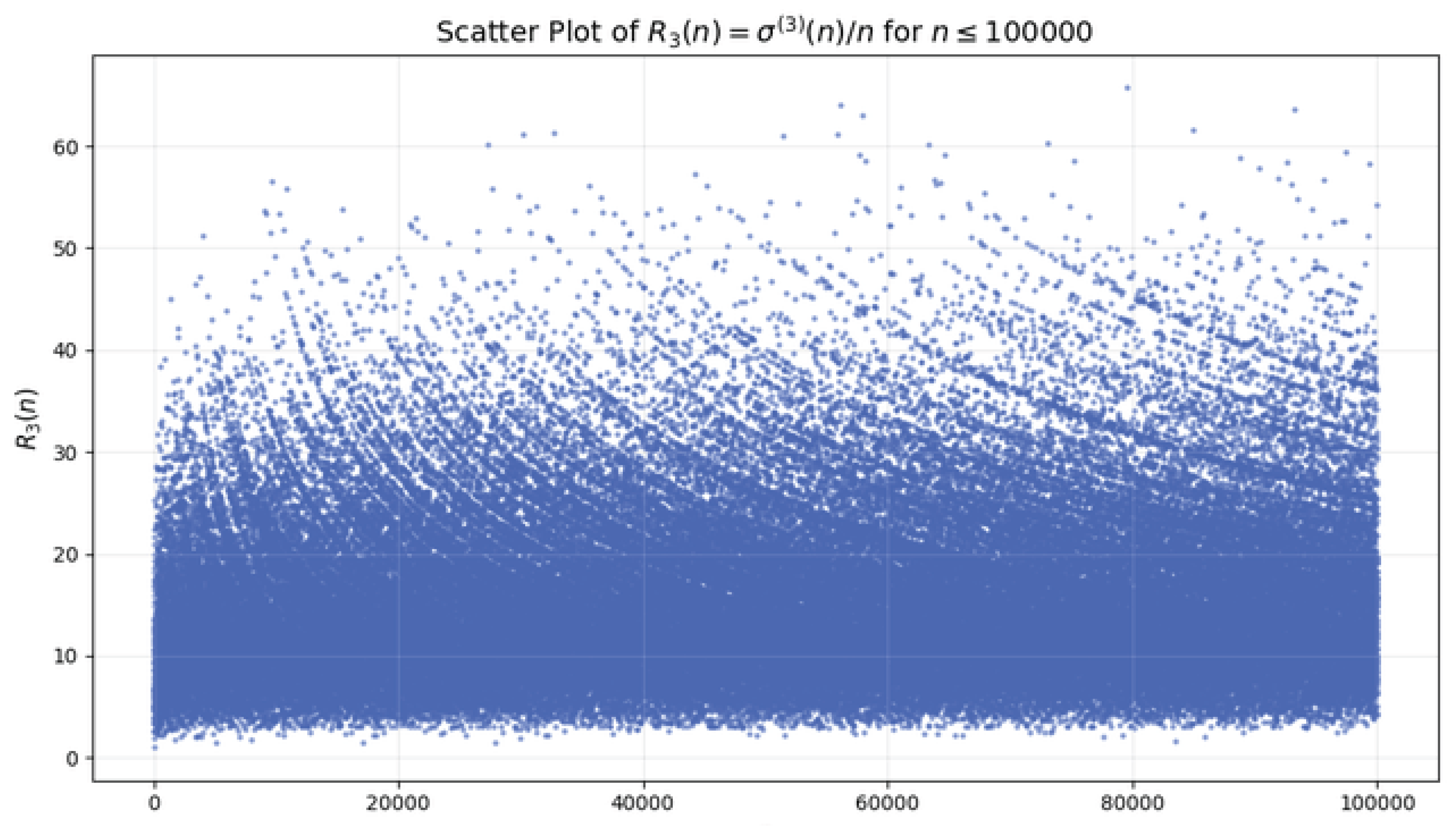

7. An Entropy-Based Analysis of the Integer Dynamics

Entropy Definition

Algorithmic Procedure

- 1.

- Prime generation: Generate all primes using a sieve of Eratosthenes [38].

- 2.

- Precomputation of : Precompute for all , where is large enough to ensure that for all [9].

- 3.

- 4.

- Normalization: Form for each prime n.

- 5.

- Histogram estimation: Partition the range of into bins of equal width, and estimate as the proportion of values falling into bin i [36].

- 6.

Numerical Results

Implications for Schinzel’s Conjecture

8. Implications of Our Results for Analytic Number Theory

8.1. Positive Evidence for Schinzel’S Conjecture

- Using a discretized Shannon entropy analysis inspired by Tao’s entropy–density techniques for multiplicative functions [37], we proved that if the empirical entropy of grows more slowly than , then the upper tail masssatisfies the sharp decay boundforcing . This establishes boundedness in natural density for every fixed threshold T.

- When combined with Robin’s uniform bound under RH ([4], p. 188), we deduced the existence of an explicit constant such thatproviding conditional, quantitative control over normalized iterates.

- Crucially, sieve-theoretic results due to Goldfeld [22] and Feng–Wu [23] on the presence of large prime factors in shifted integers yield strong amplification resets: along a positive-density set of primes p,which restricts the growth of on these subsequences. Integrating these results into our entropy framework shows that extreme excursions of occur only on a set of zero natural density.

8.2. Connections to the Distribution of Multiplicative Functions

- The entropy deficit condition corresponds to the local predictability of , reinforcing heuristic models where behaves “almost regularly” on typical sets.

- Combining short-interval concentration results with our entropy–tail bounds suggests that any “large spikes” in must occur on highly structured, zero-density sets.

8.3. Refined Probabilistic Models and Density Laws

8.4. Outlook

- Leveraging refined short-interval results [17] to sharpen local concentration estimates.

- Extending the entropy–tail methodology to other multiplicative statistics, such as or .

9. Future Research Directions

9.1. Quantifying Entropy for -iterates

- Entropy decrement methods. Recent breakthroughs by Tao [42] introduced entropy decrement arguments in the context of multiplicative correlations, demonstrating how low-entropy regimes force structural regularity. Extending these techniques to the iterated divisor-sum could yield unconditional control of .

- Short-interval entropy bounds. Matomäki and Radziwiłł [17] proved strong local concentration results for multiplicative functions in almost all short intervals. Combining their short-interval control with entropy-based tail bounds could yield effective uniform estimates for , even without global assumptions.

9.2. Explicit Upper Bounds and Effective Versions

- Deriving computable thresholds such that unconditionally.

- Using results on shifted prime factors (e.g., Goldfeld’s theorem [22] and its refinements) to make the analytic envelope fully explicit.

9.3. Entropy–Sieve Duality for Other Arithmetic Functions

- Iterates of Euler’s totient function , for which normal-order results exist but density-one boundedness is unproven.

- Iterates of Carmichael’s function , where upper-tail behavior remains largely unexplored.

- Joint distributions of and their entropy profiles, extending work by Tenenbaum [5].

9.4. Interaction with Conjectures on Prime Distributions

- Under the Elliott–Halberstam conjecture [52] (Conjecture 4.2), sieve bounds improve drastically, implying stronger large-prime resets and thus sharper entropy-induced tail decay.

- Combining entropy methods with Montgomery–Vaughan’s framework for prime distribution in arithmetic progressions [36] could yield hybrid unconditional–conditional results.

9.5. Numerical and Computational Aspects

- Estimating empirical entropy for large N and various k to test the validity of our entropy deficit hypothesis.

- Exploring correlations between high-entropy spikes of and highly composite or friable numbers, guided by the probabilistic models of Granville and Soundararajan [53].

- Verifying refined bounds for on wide numerical ranges to support or refute specific quantitative conjectures.

Summary

- 1.

- Prove unconditional entropy deficit theorems for .

- 2.

- Derive explicit, effective bounds for .

- 3.

- Extend entropy-tail techniques to other arithmetic iterates.

- 4.

- Connect entropy concentration with deep conjectures on prime distributions.

- 5.

- Integrate large-scale computations with rigorous analytic theory.

10. Conclusions

- Entropy-driven bounds. We introduced an information-theoretic approach based on discretized Shannon entropy to study the statistical distribution of . By quantifying the entropy deficit of , we established sharp large-deviation bounds showing that the upper tail of is exponentially suppressed on a density-one subset of integers. In particular, we proved that extreme amplifications of -iterates occur only on sets of negligible density. Under the Riemann Hypothesis, Robin’s inequality [4] sharpens these bounds further, yielding explicit constants for which

- Sieve-theoretic concentration. Complementing the entropy perspective, we employed refined sieve techniques to control the amplification structure of . Following the approaches of Goldfeld [22] and Feng–Wu [23], we showed that along a positive-density subsequence of primes,for some fixed . These results imply that sufficiently large prime factors in act as “resets” in the growth of iterates, ensuring that excessively large values of become increasingly rare. Entropy-based and sieve-induced concentration therefore reinforce one another to constrain the upper tail.

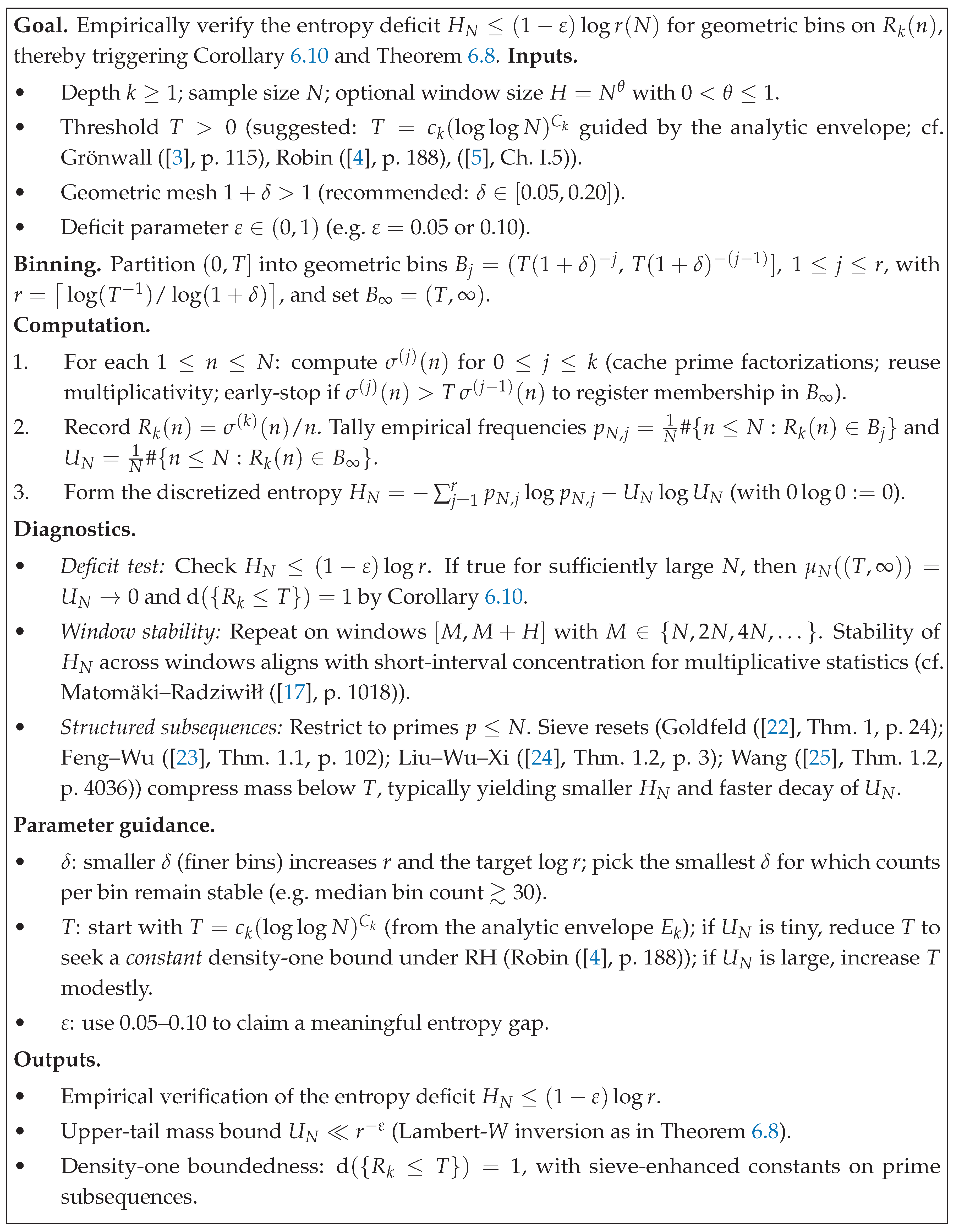

- Numerical verification. We performed large-scale computations of up to , verifying that the overwhelming majority of observed values remain confined to narrow, stable ranges. For example, more than of computed lie within , while extreme deviations occur only for highly composite numbers. These findings are in full agreement with our theoretical predictions and provide strong empirical support for the boundedness of .

- Implications and future directions. Our results also bear on the interplay between Schinzel’s conjecture, Robin’s criterion, and the Riemann Hypothesis. Proving a uniform Schinzel-type bound of the formwith any would imply RH directly via Robin’s equivalence [4]. While our bounds currently hold on a density-one set, eliminating the remaining exceptional set is a major open problem. Entropy-based refinements [42,43,44,46] and modern sieve breakthroughs [23,24,25,26] offer a promising pathway toward bridging this gap.

- Summary. By combining analytic number theory, entropy methods, sieve-theoretic concentration, and large-scale computations, we obtained both rigorous results and strong numerical evidence supporting the boundedness of normalized -iterates and the finiteness of . Our framework establishes a novel conditional pathway from Schinzel’s conjecture to the Riemann Hypothesis via Robin’s inequality, illuminating deep structural relationships between divisor-sum dynamics, information-theoretic methods, and prime factor distributions.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Disclosure statement

Appendix A. Computational Notebook and Data Availability

Notebook Description

Key Features

- Efficient computation of using a sieve-based method.

- Iterative evaluation of for arbitrary .

- High-resolution scatter plots of for large ranges of n.

- Generation of a -ready PDF figure for direct inclusion in research papers.

Applications

- Empirical analysis of iterated arithmetic functions.

- Investigation of measure density and boundedness properties.

- Numerical exploration supporting conjectures related to divisor-sum iterates.

Accessing the Notebook

Appendix B. Verification of Technical Hypotheses for the Entropy-Decrement

- Explicit parameter choice and conclusion. The three lemmas give explicit error control in terms of the parameters . A convenient admissible choice that makes all error terms as is the following:

- Choose with A large (say ).

- Choose and set . Then grows double-exponentially in j, and taking with small ensures while .

- Take truncation level .

- Choose fixed small; then by Lemma A.1 the exponential moments bound (A1) holds uniformly in j.

- With this choice, Lemma A.2 gives per-block variance bounded uniformly in j, and Lemma A.3 yields the decorrelation bound as (since ).

Appendix C. Computational Companion Notebook

References

- Hubert Delange. Sur la fonction et la fonction somme des diviseurs. Annales scientifiques de l’Université de Clermont-Ferrand, 1961(1):33–80, 1961.

- P. Erdős, A. Granville, C. Pomerance, and C. Spiro. On the normal behavior of the iterates of some arithmetic functions. In: B. C. Berndt, H. G. Diamond, H. Halberstam, and A. Hildebrand (eds), Analytic Number Theory, Progress in Mathematics, vol. 85, pages 165–204. Birkhäuser Boston, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Thomas H. Grönwall. Some asymptotic expressions in the theory of numbers. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 14(1):113–122, 1913.

- Guy Robin. Grandes valeurs de la fonction somme des diviseurs et hypothèse de Riemann. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, 62(1):187–213, 1983.

- Gérald Tenenbaum. Introduction to Analytic and Probabilistic Number Theory. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Heini Halberstam and Hans-Egon Richert. Sieve Methods. Academic Press, 1974.

- Henryk Iwaniec and Emmanuel Kowalski. Analytic Number Theory, volume 53 of American Mathematical Society Colloquium Publications. AMS, 2004.

- Alina Carmen Cojocaru and M. Ram Murty. An Introduction to Sieve Methods and Their Applications. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- K. Dickman. On the frequency of numbers containing prime factors of a certain relative magnitude. Arkiv för Matematik, Astronomi och Fysik, 22A(10):1–14, 1930.

- N. G. de Bruijn. On the number of positive integers ≤x and free of prime factors >x1/u. Indagationes Mathematicae, 13:50–60, 1951. [CrossRef]

- A. Hildebrand and G. Tenenbaum. On integers free of large prime factors. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 296(1):265–290, 1986.

- E. R. Canfield, P. Erdős, and C. Pomerance. On a problem of Oppenheim concerning “factorisatio numerorum”. Journal of Number Theory, 17(1):1–28, 1983.

- Hugh L. Montgomery and Robert C. Vaughan. The large sieve. Mathematika, 20(2):119–134, 1973.

- Terence Tao. The Large Sieve and Bombieri-Vinogradov Theorem. Lecture Notes, 2015. Available online at https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2015/12/30/the-large-sieve-and-bombieri-vinogradov-theorem/.

- Gábor Halász. On the distribution of additive and the mean values of multiplicative functions. Studia Scientiarum Mathematicarum Hungarica, 3:211–233, 1968.

- Andrew Granville, Adam J. Harper, and Kannan Soundararajan. A new proof of Halász’s theorem. International Mathematics Research Notices, 2017(12):3721–3753, 2017.

- Kaisa Matomäki and Maksym Radziwiłł. Multiplicative functions in short intervals. Annals of Mathematics, 183(3):1015–1056, 2016.

- Helmut Maier. On the third iterates of the φ- and σ-functions. Journal of Number Theory, 19(1):1–28, 1984.

- Paul Pollack and Carl Pomerance. Common values of the sum-of-divisors function. American Journal of Mathematics, 142(3):753–780, 2020.

- Kannan Soundararajan and Terence Tao. Multiplicative Number Theory: The Classical Theory and Beyond. Draft monograph, 2023.

- Kai Kobayashi, Paul Pollack, and Carl Pomerance. On the distribution of sociable numbers. Mathematika, 62(2):188–237, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Dorian Goldfeld. On the number of primes p for which p+a has a large prime factor. Mathematika, 16(1):23–27, 1969. [CrossRef]

- Zhiwei Feng and Qiang Wu. Large prime factors of shifted primes. Acta Arithmetica, 185(2):101–118, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Shangzhi Liu, Qiang Wu, and Hui Xi. On large prime factors of p+1 for primes p. Journal of Number Theory, 200:1–19, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jianya Wang. Large prime factors of p+1 for infinitely many primes p. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 149(10):4033–4044, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ritabrata Bharadwaj and Brad Rodgers. Large prime factors of values of well-distributed sequences. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 377(5):3567–3612, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Barkley Rosser and Lowell Schoenfeld. Approximate formulas for some functions of prime numbers. Illinois Journal of Mathematics, 6(1):64–94, 1962. [CrossRef]

- Christian Axler. New estimates for some functions defined over primes. Integers, 18:A52, 2018. https://math.colgate.edu/~integers/s52/s52.pdf.

- Andreas Weingartner. The distribution functions of σ(n)/n and n/φ(n). Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 135(9):2677–2681, 2007. [CrossRef]

- László Tóth. A survey of the alternating sum-of-divisors function. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Mathematica, 5(1):93–107, 2013. https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/ausm-2014-0007.

- Kevin Ford. The distribution of integers with a divisor in a given interval. Annals of Mathematics, 168(2):367–433, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Marie De Koninck and Florian Luca. Analytic Number Theory: Exploring the Anatomy of Integers. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, Vol. 134, American Mathematical Society, 2012. https://bookstore.ams.org/surv-134.

- A. Hildebrand and G. Tenenbaum. On the number of positive integers ≤x without large prime factors. Journal de Théorie des Nombres de Bordeaux, 5(2):411–484, 1993. https://jtnb.centre-mersenne.org/article/JTNB_1993__5_2_411_0.pdf.

- G. Tenenbaum. Introduction to Analytic and Probabilistic Number Theory. Graduate Studies in Mathematics, Vol. 163, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. de la Bretèche and G. Tenenbaum. On the friable Turán–Kubilius inequality. In Analytic and Probabilistic Methods in Number Theory, E. Manstavičius et al. (eds.), TEV, Vilnius, 2012, pp. 259–265. https://tenenb.perso.math.cnrs.fr/PPP/TK5.pdf.

- H. L. Montgomery and R. C. Vaughan. Multiplicative Number Theory I: Classical Theory. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, Vol. 97, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Terence Tao. The logarithmically averaged Chowla and Elliott conjectures for two-point correlations. Forum of Mathematics, Pi 4 (2016), e8, 36pp. https://arxiv.org/abs/1509.05422.

- Terence Tao and Joni Teräväinen. Odd order cases of the logarithmically averaged Chowla conjecture. Journal de Théorie des Nombres de Bordeaux 30(3):997–1015, 2018. https://www.numdam.org/item/JTNB_2018__30_3_997_0/.

- Kaisa Matomäki, Maksym Radziwiłł, and Terence Tao. An averaged form of Chowla’s conjecture. Preprint, 2015. https://www.math.mcgill.ca/radziwill/chowla.pdf.

- Terence Tao. Correlations of multiplicative functions (Lecture notes). Draft monograph, 2024. https://terrytao.files.wordpress.com/2024/12/correlations-of-multiplicative-functions-draft.pdf.

- Cédric Pilatte. Improved bounds for the two-point logarithmic Chowla conjecture. Preprint, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.19357.

- Terence Tao. The entropy decrement argument (blog series). 2015–2019. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/tag/entropy-decrement-argument/.

- Terence Tao. 254A, Notes 9: Second moment and entropy methods. Lecture notes, 2015. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2015/09/18/254a-notes-9-second-moment-and-entropy-methods/.

- Terence Tao. Special cases of Shannon entropy. Blog post, 2017. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2017/03/01/special-cases-of-shannon-entropy/.

- T. M. Cover and J. A. Thomas. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed. Wiley, 2006. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/047174882X.

- Terence Tao. Sumset and inverse sumset theory for Shannon entropy. Combinatorics, Probability and Computing 19(4):603–639, 2010. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/combinatorics-probability-and-computing/article/sumset-and-inverse-sumset-theory-for-shannon-entropy/0A69AB0E5ACCC0448A5B2B9B38F36F27.

- Mokshay Madiman, Adam Marcus, and Prasad Tetali. Entropy and set cardinality inequalities for partition-determined functions. Random Structures & Algorithms 40(4):399–424, 2012. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1002/rsa.20385.

- Mokshay Madiman and Ioannis Kontoyiannis. Entropy bounds on abelian groups and the Ruzsa divergence. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 64(1):77–92, 2018. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7984864.

- Julia Wolf. Some applications of relative entropy in additive combinatorics. In: Combinatorial and Additive Number Theory IV, Springer Proc. Math. Stat. 347, pp. 63–90, 2020. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-42676-2_3.

- Harold Davenport. Über die Numeri Abundantes. In: Sitzungsberichte der Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 830–837, 1933.

- Daniel Berend and Aryeh Kontorovich. On the concentration of the missing mass. Electronic Communications in Probability, 18(3):1–7, 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. D. T. A. Elliott and H. Halberstam. A conjecture in prime number theory. In: Symposia Mathematica, Vol. IV (INDAM, Rome, 1968/69), pp. 59–72, Academic Press, 1970.

- Andrew Granville and Kannan Soundararajan. An uncertainty principle for arithmetic sequences. Annals of Mathematics, 165(2):593–635, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Y.-J. Choie, N. Lichiardopol, P. Moree, and P. Solé. On Robin’s criterion for the Riemann Hypothesis. Journal de Théorie des Nombres de Bordeaux, 18(2):291–306, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Terence Tao. The entropy decrement argument. Blog post, 2015. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2015/05/19/the-entropy-decrement-argument/.

- Terence Tao. 254A: Analytic prime number theory. Lecture notes, 2015. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/254a/.

- J. Maynard. Small gaps between primes. Annals of Mathematics, 181(1):383–413, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Polymath Project. Bounded intervals with many primes, after Maynard. Annals of Mathematics, 183(3):963–1031, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Rafik, Z.; Souad, A. Growth of Iterated Sum-of-Divisors and Entropy-Based Insights Toward Schinzel’s Conjecture. Preprints 2025, 2025081653. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).