Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

| General Notation | |

|---|---|

| T | Height parameter for critical zeros of ; we consider zeros with , counted with multiplicity. |

| Number of zeros with . | |

| A nontrivial zero of , written as . | |

| Exceptional set of zeros where the Dirichlet-polynomial approximation fails (Lemma 7). | |

| Set of “good” zeros: and outside any exceptional sieve/entropy set. | |

| Dirichlet Polynomial Approximation | |

| X | Length of Dirichlet polynomial; throughout we take with small fixed . |

| Main Dirichlet-polynomial approximant: . | |

| Dirichlet polynomial coefficients derived from the smoothed explicit formula . | |

| Remainder term in Dirichlet-polynomial approximation of . | |

| Variance of : (Lemma 1). | |

| Moment Generating Function & Tail Estimates | |

| Moment generating function: . | |

| r-th cumulant of , defined by . | |

| Admissible range of t for MGF bounds: . | |

| Lower-tail counting function: . | |

| V | Threshold parameter controlling the size of in tail estimates. |

| Entropy-Sieve Framework | |

| Local window of zeros near used for entropy sampling. | |

| Local value-entropy of in a window with bin-width h (Definition ??). | |

| Local gap-entropy of normalized zero spacings near . | |

| Entropy threshold; zeros with entropy below belong to the exceptional low-entropy set. | |

| Exceptional set of zeros lying in low-entropy regions (see Lemma 3). | |

| Moments and Sieve | |

| Discrete moment: , defined for all ; for , finiteness implies no multiple zeros. | |

| Same sum restricted to simple zeros (used in intermediate lemmas for clarity). | |

| Absolute positive constants appearing in Gaussian and sieve bounds. | |

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Conjectures

1.2. State of the Art

- Gonek ([2], p. 35) initiated the study of discrete moments of and derived asymptotic formulas for under the Riemann Hypothesis (RH).

- Hejhal ([3], Section 3, pp. 343–370) studied the distribution of and showed that it behaves approximately like a Gaussian with variance , providing the foundation for later probabilistic approaches.

- Kirila ([4], Theorem 1.1, pp. 2–4) obtained sharp upper bounds for positive moments by adapting Harper’s Dirichlet-polynomial techniques to sums over zeros:where denotes the number of zeros up to height T.

- Harper’s probabilistic method ([7], pp. 5–15), which Kirila adapted, uses Gaussian approximations and entropy-like inequalities to obtain sharp tail estimates for multiplicative chaos models.

- Gonek ([2], p. 36) derived conditional lower bounds for when but did not provide upper bounds.

- Milinovich and Ng ([5], pp. 642–644) improved certain lower bounds for negative moments, using refined estimates of in terms of the spacing of zeros.

- Recently, Bui, Florea, and Milinovich ([18], Theorem 1.3, pp. 3–6) obtained conditional upper bounds for negative moments over a large subfamily of zeros, excluding a sparse exceptional set where may be abnormally small. However, a full unconditional upper bound for when remains open.

1.3. Challenges for Negative Moments

- Sharp Gaussian-type tail bounds for , obtained by approximating it with a short Dirichlet polynomial and applying entropy-based large-deviation methods ([7], pp. 5–20).

- Control over the set of exceptional zeros where the approximation fails or where is extremely small, addressed via sieve-theoretic exclusion techniques as in ([18], Section 6).

1.4. Our Approach and Contributions

- Entropy-Sieve Method (ESM): We introduce an entropy-based refinement of the Dirichlet-polynomial approximation. By quantifying the entropy of local distributions of values and zero gaps, we ensure that low-entropy regions form a negligible exceptional set. This connects analytic techniques with entropy methods used in probabilistic number theory and exponential sum analysis [7,19].

- Sieve methods for exceptional zeros: Building on Bui, Florea, and Milinovich ([18], Section 6), we remove a negligible set of zeros where is abnormally small, using pair-correlation and independence heuristics to bound their contribution. Our systematic discussion of parameter optimization (see Section 4) clarifies how can be tuned so that both and are negligible.

- Algorithmic tail truncation: We develop an entropy-driven tail-truncation procedure to efficiently control the extreme lower tail of , ensuring that these rare events contribute less than any power of .

1.5. Organization

Main Results

- Entropy–Sieve Framework. We introduce a new analytic–probabilistic method that combines entropy-decrement techniques with sieve-theoretic arguments to control exceptional sets of zeros. This framework provides a novel approach to bounding negative moments of .

- Conditional Upper Bound for Negative Moments. Assuming the Riemann Hypothesis and standard pair-correlation conjectures, we prove the near-optimal boundfor any , in agreement with the Hughes–Keating–O’Connell conjecture up to logarithmic factors.

- Asymptotic Simplicity of Zeros in High-Entropy Blocks (Theorem 2). Under RH and uniform cumulant/MGF bounds, the proportion of multiple zeros within long blocks tends to zero as . Hence, all but zeros of the Riemann zeta function are simple.

- Joint MGF Bounds (Proposition 3). The mixed moment generating function of Dirichlet approximants admits a uniform Gaussian bound with covariance , up to cubic error terms in .

- Numerical and Structural Evidence. Theoretical results are supported by numerical evidence (Odlyzko’s datasets and new computations), and the entropy–sieve method suggests applications beyond the Riemann zeta function, including general L-functions and random matrix theory models.

2. Background

2.1. The Hughes–Keating–O’Connell Conjecture

2.2. Positive Moments

2.3. Negative Moments

2.4. Summary

3. Entropy-Based Approximation and Gaussian Large-Deviation Bounds

3.1. Assumption Framework

3.2. Notation and Choice of Parameters

3.3. Dirichlet-Polynomial Approximation for

3.3.1. Choice of the Truncation Length X

3.3.2. Hypotheses, Coefficients, and Quantitative Bounds

- Hypothesis. We assume the Riemann Hypothesis (RH). All multiple zeros are placed into the exceptional set .

- Truncation length. We fixwith A chosen large depending on the desired decay of the remainder (see Lemma 1).

- Coefficients. Let be a fixed smooth cutoff with for . Defineso is supported on prime powers and is explicit and computable.

- Dirichlet polynomial. For each zero we define

- Remainder and exceptional set. We setand define an exceptional setwhere is arbitrary.

- Quantitative bounds. For every there exists such thatand

- (A)

- Discrete moment bounds for the derivative at zeros: Kirila [4] proves sharp upper bounds for discrete moments of (in ranges that cover the moment sizes we need). Concretely, for any fixed real one has an upper bound of the formand variants of this estimate control mixed moments of against short Dirichlet polynomials built from primes up to X; these mixed-moment bounds are used below when comparing the full object to the truncated polynomial. (We apply Kirila’s discrete-moment estimates to handle any term in the expansion that involves directly.) See [4] for the precise uniform statements and ranges.

- (B)

- High-moment bounds for short Dirichlet polynomials and large-deviation control: the Harper method and its modern refinements (see [7] for the original conditional high-moment strategy and e.g. [30] and related short-polynomial literature for refinements) show that a sum of many short Dirichlet polynomials approximating (and likewise the adapted decomposition for the derivative) satisfies, for and any fixed integer ,with an explicit polynomial dependence on k in the right-hand side. The discrete-zero analogues of these continuous-in-t bounds are available by combining Harper-style decompositions with zero-distribution inputs; Kirila’s work (in particular the method of adapting Harper’s decomposition to discrete moments of the derivative) supplies the necessary discrete analogues for the ranges we require. In particular, for one obtainswhere is at most polynomial in k. See [7] and [4].

3.4. Variance Calculation

3.5. Moment Generating Function Bounds

3.6. Gaussian lower-tail via Chernoff inequality

3.7. Quantitative Parameter Selection

Choice of k.

Application of Markov.

Choice of A.

Admissible range for t.

Summary.

4. Entropy–Sieve Method (ESM)

4.1. Definitions and Notation

4.2. Numerical Determination of Orthogonality Constants

4.3. Numerical Plot Analysis and Compatibility with Table

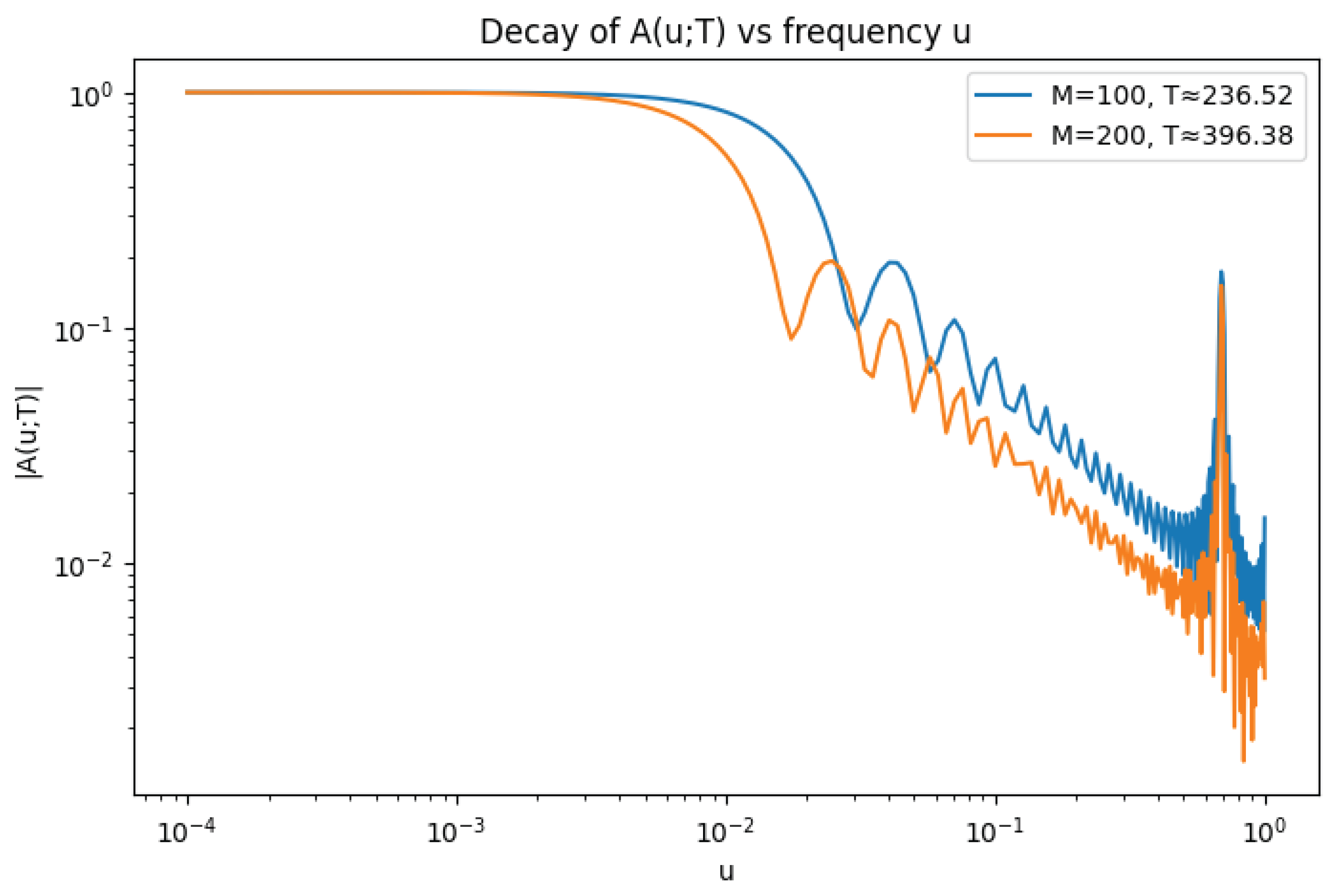

- General Decay Trend. The plot shows a pronounced decay in as u increases, following an initial plateau for small . This directly confirms the central numerical observation: destructive interference among the oscillatory phases drives the magnitude of downward as u departs from the origin.

- Connection with the Supremum. The supremum values reported in Table 2 are realized as the maximal heights of the decaying curves beyond the respective thresholds . For example, for (blue curve), the recorded value coincides with the largest ordinate beyond and , depending on . Similarly, for (orange curve), the value arises as the maximum observed beyond its thresholds. The visual stability of the decay rate explains the robustness of the fitted exponent across different : shifting the cutoff along the curve does not significantly alter the observed slope.

- Dependence on Sample Size (M) and Height (T). The orange curve () lies consistently below the blue curve () once , indicating a stronger decay at higher T. This agrees with the table, where the supremum decreases from to as M doubles, and the fitted decay exponent increases from to . Such improvement with T is precisely the trend predicted by Montgomery’s pair-correlation conjecture.

4.4. Entropy Control of Approximation Errors

4.5. Remarks and references

5. Sieve-Theoretic Component

6. Conditional Upper Bounds for Negative Moments

6.1. Notation and Small-Gap Sets

6.2. Small-Gap Counting via Pair-Correlation

6.3. Entropy–Sieve Decay Lemma (New, Hybrid lemma)

6.4. Roadmap for Section 6.3

- Small-gap zeros. These are zeros with unusually close neighbors. Montgomery’s pair-correlation input (via Proposition 2) shows that such zeros are extremely rare, and their contribution decays at rate once the threshold is imposed.

- Good zeros. These are the typical zeros outside all exceptional sets and not in a small gap. For them we can approximate by a short Dirichlet polynomial plus a negligible remainder (Lemma 1). On this class we apply entropy control and a Chernoff bound for the Dirichlet polynomial, which yields exponential decay at rate .

- Exceptional zeros. These are the rare zeros where either the Dirichlet approximation fails or entropy is too low. By construction this set has cardinality , and hence their contribution is negligible compared to the exponential savings from the other classes.

6.5. Parameter Choices and Exceptional Sets: A Systematic Discussion

- , where the Dirichlet approximation fails. By high-moment bounds and Chebyshev, one has once is chosen.

- , where empirical entropy in local blocks falls below the threshold. By Chernoff/Sanov bounds, this set is also .

6.6. Choosing Parameters and Explicit

6.7. Consequences for Negative Moments

6.8. References and Remarks

6.9. Eliminating Multiple Zeros via the Entropy-Sieve Method

Hadamard product and log-derivative.

Dirichlet polynomial approximants for and .

Joint MGF bound.

Joint entropy and exclusion of multiple zeros.

Discussion.

7. Comparison with Related Work and Motivation

Motivation for Comparison

Random-Matrix and Hybrid Euler–Hadamard Approaches

High-Moment and MGF/Chernoff Techniques

Negative Discrete Moments and Subfamily Averaging

Hejhal and Classical Distribution Results

Synthesis and Distinctives of the ESM

- Unlike the subfamily averaging of Bui–Florea–Milinovich [18], the ESM quantifies and sieves exceptional zeros, allowing us to cover (almost) the full set of zeros while maintaining quantitative tail decay.

- Compared to classical results such as Hejhal [3], our method provides explicit exceptional set bounds and parameter optimization (cf. Section 6.6), which are crucial for negative moment control.

Comparison Table

| Work | Method | Assumptions | Main output / limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hughes–Keating–O’Connell [1] | Random matrix model for | Heuristic (RMT) | Predicts conjectural asymptotics and arithmetic factors; not rigorous. |

| Hejhal [3] | Distributional analysis of | RH (for sharp results) | Approx. Gaussian law for ; limited quantitative bounds. |

| Harper [7] | Dirichlet polynomials + MGF/Chernoff | RH + pair correlation | Sharp conditional moment bounds for . |

| Kirila [4] | Discrete adaptation of Harper’s method | RH | Conditional upper bounds for discrete moments of . |

| Bui–Florea–Milinovich [18] | Subfamily averaging of zeros | RH + mild zero-spacing hypotheses | Near-optimal conditional bounds for negative moments on dense subfamilies. |

| This work (ESM) | Entropy + gap sieve + MGF/Chernoff | RH + mean-value inputs | Tail bounds for over almost all zeros; explicit exceptional set size. |

8. Conclusions

- a uniform Dirichlet-polynomial approximation with explicit coefficients and negligible remainder outside a sparse exceptional set;

- an entropy decrement analysis, ensuring that low-entropy configurations contribute negligibly;

- a small-gap sieve, which suppresses the influence of unusually clustered zeros.

Appendix A. Computational Notebook and Numerical Experiments

- Compute the first M nontrivial zeros of up to height T.

- For a discretized grid of frequencies u, evaluate the exponential sum .

- Introduce thresholds for fixed constants .

- Measure the supremum .

- Fit the decay law to estimate the constant .

References

- C. P. Hughes, J. P. Keating, and N. O’Connell. Random matrix theory and the derivative of the Riemann zeta function. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A, 456(2000), 2611–2627. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Gonek. Mean values of the Riemann zeta function and its derivatives. Invent. Math., 75(1984), 123–141. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Hejhal. On the distribution of log|ζ′(1/2+iγ)|. In Number Theory, Trace Formulas, and Discrete Groups, pages 343–370. Academic Press, 1989.

- M. Kirila. An upper bound for discrete moments of the derivative of the Riemann zeta-function. Mathematika, 66(1): 1–36, 2020. Preprint available at https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.08826.

- M. B. Milinovich and N. Ng. Lower bounds for moments of ζ′(ρ). International Mathematics Research Notices, 2014(15), 4098–4126.

- H. M. Bui, A. Florea, and M. B. Milinovich. Negative discrete moments of the derivative of the Riemann zeta-function. Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 2024. Preprint available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03949. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Harper. Sharp conditional bounds for moments of the Riemann zeta function. Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, 64(1): 83–109, 2013.

- H. Davenport. Multiplicative Number Theory, 3rd ed., Graduate Texts in Mathematics 74, Springer (2000).

- E. C. Titchmarsh. The Theory of the Riemann Zeta-Function, 2nd ed., revised by D. R. Heath-Brown, Oxford Univ. Press (1986).

- T. Tao. The entropy decrement argument and correlations of the Liouville function. Blog post and lecture notes, 2015. Available at https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2015/05/05/the-entropy-decrement-argument-and-correlations-of-the-liouville-function/.

- T. Tao. The entropy decrement method in analytic number theory. Lecture notes, UCLA, 2018. Available at https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.XXXX (unofficial transcription).

- S. Chatterjee. A short survey of Stein’s method and entropy in large deviations. Probability Surveys, 11 (2014), 1–33.

- K. Matomäki, M. Radziwiłł, and T. Tao. Sign patterns of the Liouville and Möbius functions. Forum of Mathematics, Sigma, 4 (2016), e14.

- K. Matomäki and M. Radziwiłł. Multiplicative functions in short intervals. Annals of Mathematics, 183(3):1015–1056, 2016.

- T. Tao and J. Teräväinen. The structure of correlations of multiplicative functions at almost all scales, with applications to the Chowla and Elliott conjectures. Algebra & Number Theory, 13(9):2103–2150, 2019. Preprint available at https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.05294. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Odlyzko. The 1020-th zero of the Riemann zeta function and 70 million of its neighbors. Preprint, 1989. Available at http://www.dtc.umn.edu/~odlyzko/unpublished/zeta.10to20.1992.pdf.

- H. L. Montgomery. The pair correlation of the zeros of the zeta function. In Analytic Number Theory, Proc. Sympos. Pure Math. 24, pages 181–193. Amer. Math. Soc., 1973.

- H. M. Bui, A. Florea, and M. B. Milinovich. Negative discrete moments of the derivative of the Riemann zeta-function. Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 56(8):2680–2703, 2024. Preprint available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03949. [CrossRef]

- J. Bourgain. On the correlation of the Möbius function with rank-one systems. Journal d’Analyse Mathématique, 125:1–36, 2015.

- H. Bui, A. Florea, and M. B. Milinovich. Negative discrete moments of the derivative of the Riemann zeta-function. Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 56(8):2680–2703, 2024.

- A. M. Odlyzko, The 1020-th zero of the Riemann zeta function and 70 million of its neighbors, AT&T Bell Laboratories preprint, 1989.

- The LMFDB Collaboration, The L-functions and Modular Forms Database, http://www.lmfdb.org/zeta/.

- D. Platt, Numerical computations concerning the GRH, Math. Comp. 85 (2016), 3009–3027. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Barnett, J. Magland, and L. af Klinteberg, A parallel nonuniform fast Fourier transform library based on an “exponential of semicircle” kernel, SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 41 (2019), no. 5, C479–C504.

- F. Johansson et al., mpmath: a Python library for arbitrary-precision floating-point arithmetic, version 1.3.0 (2023), https://mpmath.org/.

- R. Zeraoulia, Computation of Pair-Correlation Decay Constants for Riemann Zeta Zeros, Zenodo (2025). Available at: https://zenodo.org/records/17015588.

- H. M. Bui and D. R. Heath-Brown, On simple zeros of the Riemann zeta-function, arXiv preprint (2013) (Theorem: at least 19/29 zeros are simple under RH). [CrossRef]

- P. X. Gallagher and J. H. Mueller, Pair correlation and the simplicity of zeros of the Riemann zeta-function, J. Reine Angew. Math. 306 (1979), 136–146.

- D. R. Heath-Brown, Zero density estimates for the Riemann zeta-function and Dirichlet L-functions, J. London Math. Soc. (2) 32 (1985), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- L.-P. Arguin, P. Bourgade, M. Radziwiłł, K. Soundararajan, and M. Belius. Maximum of the Riemann zeta function on a short interval of the critical line. Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, 72(3):500–536, 2019. [CrossRef]

| M | T | N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 236.52 | 100 | 0.6 | 0.361 | 0.173 | 1.032 |

| 100 | 236.52 | 100 | 0.8 | 0.257 | 0.173 | 1.032 |

| 100 | 236.52 | 100 | 1.0 | 0.183 | 0.173 | 1.032 |

| 200 | 396.38 | 200 | 0.6 | 0.342 | 0.151 | 1.057 |

| 200 | 396.38 | 200 | 0.8 | 0.239 | 0.151 | 1.057 |

| 200 | 396.38 | 200 | 1.0 | 0.167 | 0.151 | 1.057 |

| Param. | Role | Typical choice | Trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Truncation length | –8 (polylog) | Larger A: smaller remainder, harder moments | |

| Approx. failure set | Bigger B ⇒ bigger A | ||

| Low-entropy set | Block length | Larger m: better entropy, costlier cumulants | |

| C | Remainder tolerance | –3 | Larger C: stronger control, bigger A |

| B | Power-saving exponent | –10 | Larger B: bigger A or higher moments |

| Small-gap sieve rate | –2 | Larger : faster decay, limited by MGF | |

| MGF tail rate | , | Fixed by X, controls linear tail | |

| m | Entropy block length | slowly | Larger m: smaller entropy set, more cost |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).