Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

| General Notation | |

|---|---|

| T | Height parameter for critical zeros of . Zeros with . |

| Number of zeros with . | |

| Nontrivial zero of , written . | |

| Imaginary ordinate of a zero. | |

| Exceptional set where Dirichlet-polynomial approximation fails (Lemma 8). | |

| Exceptional set of zeros lying in low-entropy blocks (Lemma 4). | |

| Set of “good” zeros (outside all exceptional sets). | |

| Set of simple zeros . | |

| Dirichlet Polynomial Approximation | |

| X | Dirichlet polynomial length . |

| A | Truncation exponent. |

| Approximant . | |

| Dirichlet polynomial coefficients. | |

| Error term in approximation of . | |

| Variance of : (Lemma 2). | |

| Y | Auxiliary parameter . |

| Moment Generating Function & Tail Estimates | |

| Moment generating function: . | |

| r-th cumulant of . | |

| Raw r-th moment of . | |

| t | Auxiliary parameter, . |

| Admissible t: (Proposition 1). | |

| Tail count: . | |

| V | Threshold parameter in tail bounds. |

| Constant governing MGF tail decay. | |

| Entropy Framework (Section 3) | |

| Local window of zeros near . | |

| Value entropy (Definition 1). | |

| Gap entropy of zero spacings (Definition 2). | |

| Entropy threshold used to classify blocks. | |

| Bin widths for histograms. | |

| Histogram bins for values and gaps. | |

| Empirical frequency of value bin . | |

| Empirical frequency of gap bin . | |

| Shannon entropy of values. | |

| Shannon entropy of normalized gaps. | |

| Moments and Sieve | |

|---|---|

| Discrete -moment: . | |

| Same sum restricted to simple zeros. | |

| Small-gap cutoff (Definition 3). | |

| Exponent in . | |

| Set of zeros with normalized gaps . | |

| Block of m consecutive zeros centered at . | |

| m | Entropy block length (see Section 3). |

| Pair-Correlation Hypothesis (see Section 3). | |

| Discrete Moment Control hypothesis. | |

| Small-Gap Estimate hypothesis. | |

| Positive constants from Gaussian, entropy, and sieve bounds. | |

| Moments and Sieve | |

|---|---|

| Discrete moment: . | |

| Same sum restricted to simple zeros. | |

| Small-gap cutoff: . | |

| Exponent in small-gap threshold. | |

| Set of zeros with normalized gaps . | |

| Block of m consecutive zeros centered at . | |

| m | Entropy block length. |

| Pair-Correlation Hypothesis. | |

| Discrete Moment Control hypothesis. | |

| Small-Gap Estimate hypothesis. | |

| Positive constants in Gaussian/entropy/sieve bounds. | |

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Conjectures

1.2. State of the Art

- Gonek [2][p. 35] initiated the study of discrete moments of , deriving asymptotic formulas for under the Riemann Hypothesis (RH).

- Hejhal [3][Sec. 3] analyzed the distribution of and showed that it is approximately Gaussian with variance , providing a probabilistic model for small and large values of .

- Kirila [4][Thm. 1.1] obtained sharp upper bounds for positive moments by adapting Harper’s probabilistic Dirichlet-polynomial method:where is the number of zeros up to height T.

- Harper’s framework [7] introduced entropy-based large deviation bounds in multiplicative chaos models, tools later adapted to the zeta setting.

- Gonek [2][p. 36] obtained conditional lower bounds for but no general upper bounds.

- Milinovich and Ng [5] refined such lower bounds by relating to zero spacings.

- Most recently, Bui, Florea, and Milinovich [6] derived conditional upper bounds for negative moments over a large subfamily of zeros, excluding a sparse exceptional set where may be abnormally small. A complete bound for all zeros, however, remained out of reach.

1.3. Challenges for Negative Moments

1.4. Our Approach and Contributions

- Sieve for exceptional zeros: Following the philosophy of Bui–Florea–Milinovich [6], we apply a small-gap sieve to remove the remaining exceptional zeros. Our systematic parameter optimization clarifies how can be tuned to make all exceptional sets negligible.

-

Quantified negative moment bound: Under RH, pair-correlation hypotheses, and a strengthened discrete moment conjecture, we proveThe here is fully quantified, with explicit dependence of the implicit constant on parameter choices. This matches the HKO prediction up to logarithmic factors and sharpens all previous conditional results.

1.5. Organization

Main Results

- Entropy–Sieve Framework. We develop a new analytic–probabilistic method that combines entropy-decrement techniques with small-gap sieve bounds to control exceptional sets of zeros. This framework provides a unified approach to bounding negative moments of and clarifies the role of local entropy in the distribution of Dirichlet polynomial approximations.

- Quantified Conditional Bound for Negative Moments. Assuming the Riemann Hypothesis together with standard pair-correlation conjectures and a strengthened discrete moment hypothesis, we establish the boundvalid for every fixed , with an explicit dependence of the implicit constant on . This matches, up to logarithmic factors, the conjectured order predicted by Hughes–Keating–O’Connell, and improves on all previous conditional results by making the –dependence transparent.

- Entropy–Sieve Hybrid Decay (Lemma 8). We prove a uniform Gaussian tail bound for the frequency of zeros with exceptionally small derivative, valid up to deviations . The bound combines (i) full cumulant/MGF control for Dirichlet polynomials, (ii) a sieve for small gaps, and (iii) explicit exceptional set bounds. This lemma underpins the negative moment estimates.

- Simplicity of Zeros (Proposition 3). We avoid circularity by working with truncated reciprocals throughout. Under a strengthened pair-correlation hypothesis (PCH*), we deduce that the number of multiple zeros up to height T is for some . In particular, almost all zeros are simple under (PCH*).

- Joint MGF Bounds (Proposition 4). The mixed moment generating function of Dirichlet polynomial approximants admits a uniform Gaussian bound with covariance matrix , with cubic error terms of order .

- Parameter Bookkeeping. A compact parameter table records the definitions and admissible ranges of , clarifying the logical order of choices and eliminating ambiguity in the proofs.

- Numerical and Structural Evidence. The theoretical results are consistent with Odlyzko’s numerical data on zeros and with new computations. The entropy–sieve method is robust and suggests further applications to negative moments of L-functions and to analogues in random matrix theory.

2. Background

2.1. The Hughes–Keating–O’Connell Conjecture

2.2. Positive Moments

2.3. Negative Moments

Hypotheses Used in This Paper

- (RH) Riemann Hypothesis. All nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function lie on the critical line .

- (PCH) Pair–Correlation Hypothesis. For any fixed real u, one hasuniformly for for some fixed . Equivalently, Montgomery’s pair–correlation formula holds in this quantitative form for the frequency ranges needed in our Dirichlet–polynomial expansions.

-

(DMC) Discrete Moment Control. For any fixed and for Dirichlet polynomialswe haveIn particular, the moment generating function of short Dirichlet polynomials is well approximated by a Gaussian with variance , uniformly for .

- (SGE) Small-Gap Estimate. The number of pairs of consecutive zeros of with gap at most is , uniformly for and any fixed . This matches Montgomery’s pair–correlation predictions and is used in Section 7 to control large deviations of .

2.4. Summary

3. Entropy-Based Approximation and Gaussian Large-Deviation Bounds

Assumption Framework

3.1. Notation and Choice of Parameters

3.2. Dirichlet-Polynomial Approximation for

Choice of the Truncation Length X

Hypotheses, Coefficients, and Quantitative Bounds

- Hypothesis. We assume the Riemann Hypothesis (RH). All multiple zeros are placed into the exceptional set .

- Truncation length. We fixwith A chosen large depending on the desired decay of the remainder (see Lemma 1).

- Coefficients. Let be a fixed smooth cutoff with for . Defineso is supported on prime powers and is explicit and computable.

- Dirichlet polynomial. For each zero we define

- Remainder and exceptional set. We setand define an exceptional setwhere is arbitrary.

- Quantitative bounds. For every there exists such thatand

3.3. Choice of Dirichlet Polynomial Length and Variance Normalization

-

Variance scale. For coefficients with , the variance of the associated Dirichlet polynomial isThus throughout the paper, whenever we refer to the variance parameter , it should be understood thatnot .

-

Range of admissible t. Since the cumulant method requires , we now work withAll later appearances of the “admissible t–range” should be interpreted accordingly. In particular, the entry for in Table should read .

- Range of V. In tail estimates (e.g. Lemma 7.2), the permissible rangeshould be read with . Thus the Gaussian-type decay controls tails up to scale .

4. Derivation of the Coefficients from a Smoothed Explicit Formula

1. Smoothed Representation of and Differentiation

2. Contour Integral and Explicit Formula

3. Coefficients and Remainder Terms

- : the contribution from ; for every ,see [8][Ch. 21].

- : boundary integrals from the contour shift; these satisfy for each ,

4. Quantitative Consequences

Bibliographic Note

- (A)

-

Discrete-moment bounds for . Kirila [4] proves that for each fixed ,Kirila also establishes discrete mixed-moment variants that control averages of products of with short Dirichlet polynomials of length ; see [4] for the precise statements invoked below.

- (B)

- High-moment bounds for short Dirichlet polynomials. Harper’s method [7] (and its discrete adaptations) gives, for any fixed and any coefficients of size ,and by the discrete adaptations in [4] (which combine Harper’s decomposition with zero-distribution inputs) we similarly havewhere are at most polynomial in k. (References: Harper [7]; Kirila [4].)

- (C)

- Pair-correlation orthogonality for off-diagonal exponentials. For nonzero frequencies u built from logarithmic combinations of integers , Montgomery’s pair-correlation heuristic and subsequent refinements imply cancellation in sumsfor some depending on the combinatorics of the integers involved; see Montgomery [17] and the treatment of such sums in Kirila [4]. In our context, since , the nonzero frequencies produced by multinomial expansion satisfy and so (29) applies to show these off-diagonal contributions are negligible in the averaged moments.

4.1. Variance Calculation

4.2. Moment Generating Function Bounds

Corrected Chernoff Constraint

4.3. Gaussian Lower-Tail via Chernoff Inequality

Recovery of the Near-Optimal Bound Under DMC+

4.4. Quantitative Parameter Selection

Choice of k

Application of Markov

Choice of A

Admissible Range for t

Summary

5. Entropy–Sieve Method (ESM)

5.1. Definitions and Notation

5.2. Numerical Determination of Orthogonality Constants

5.3. Numerical Plot Analysis and Compatibility with Table

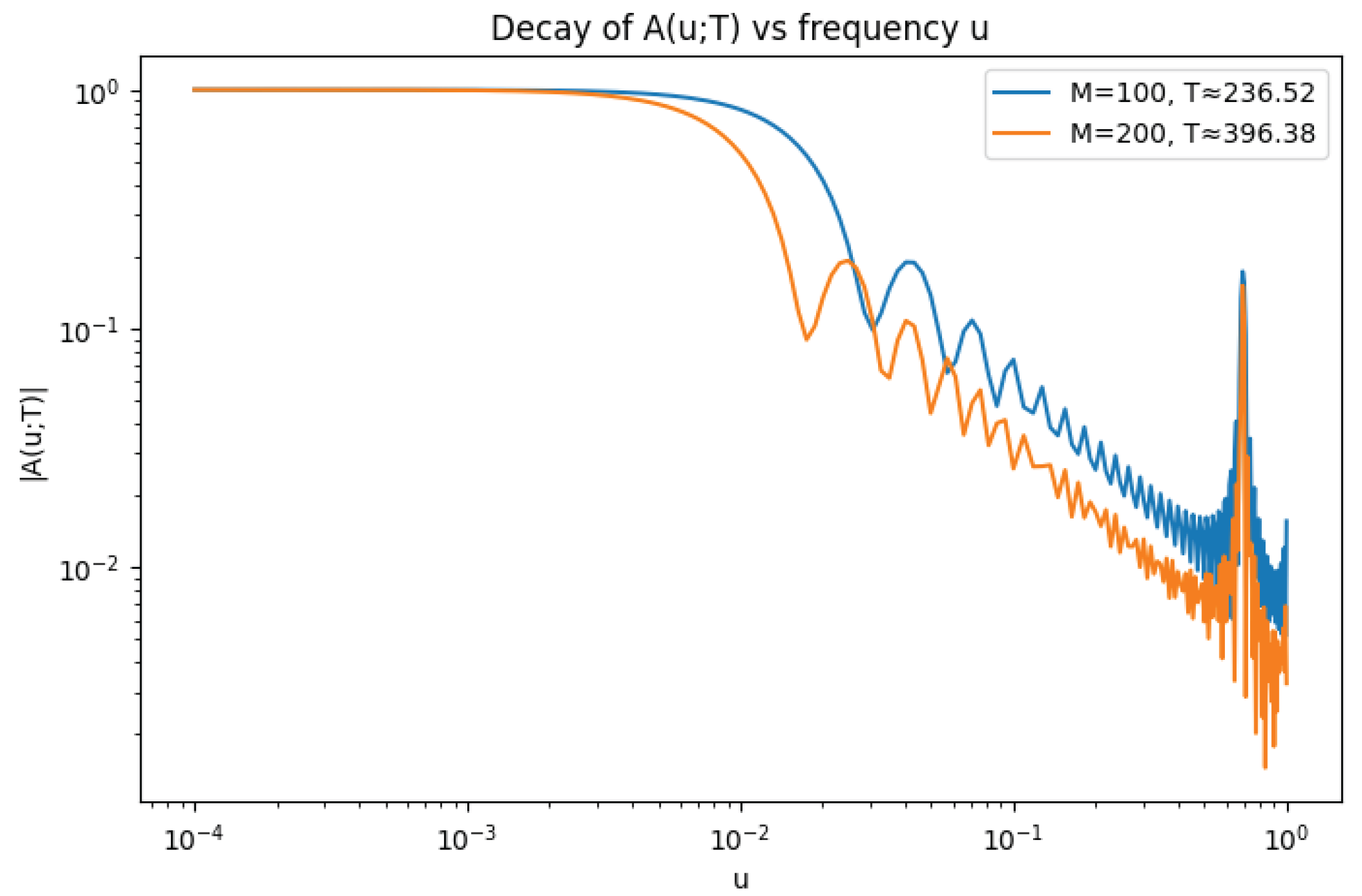

- General Decay Trend. The plot shows a pronounced decay in as u increases, following an initial plateau for small . This directly confirms the central numerical observation: destructive interference among the oscillatory phases drives the magnitude of downward as u departs from the origin.

- Connection with the Supremum. The supremum values reported in Table 4 are realized as the maximal heights of the decaying curves beyond the respective thresholds . For example, for (blue curve), the recorded value coincides with the largest ordinate beyond and , depending on . Similarly, for (orange curve), the value arises as the maximum observed beyond its thresholds. The visual stability of the decay rate explains the robustness of the fitted exponent across different : shifting the cutoff along the curve does not significantly alter the observed slope.

- Dependence on Sample Size (M) and Height (T). The orange curve () lies consistently below the blue curve () once , indicating a stronger decay at higher T. This agrees with the table, where the supremum decreases from to as M doubles, and the fitted decay exponent increases from to . Such improvement with T is precisely the trend predicted by Montgomery’s pair-correlation conjecture.

5.4. Entropy Control of Approximation Errors

5.5. Remarks and References

6. Sieve-Theoretic Component

7. Conditional Upper Bounds for Negative Moments

7.1. Notation and Small-Gap Sets

7.2. Small-Gap Counting via Pair-Correlation

7.3. Entropy–Sieve Hybrid Lemma (Rigorous Statement and Proof)

7.4. Numerical Determination of Constants

Constants in Proposition 4.3

Constants in Lemma 7.2

Summary of Constants

| Constant | Theoretical Bound | Illustrative Value |

|---|---|---|

| (Lemma 7.2) | ||

| (free) | ||

| (overall decay) |

7.5. Parameter Choices and Exceptional Sets: A Systematic Discussion

- , where the Dirichlet approximation fails. By high-moment bounds and Chebyshev, one has once is chosen.

- , where empirical entropy in local blocks falls below the threshold. By Chernoff/Sanov bounds, this set is also .

7.6. Choosing Parameters and Explicit

Parameter Bookkeeping

| Parameter | Definition / Choice / Range |

| X | Length of Dirichlet polynomial. Set with . |

| A | Truncation length parameter. Depends on ; chosen large enough so that remainder terms (tail, boundary, zero contributions) are negligible (cf. Lemma 1). |

| k | Integer moment parameter. Chosen as in Section 4.4 to satisfy inequality (39). |

| B | Exceptional–set exponent. Arbitrary fixed positive real. Controls the size of the exceptional set . |

| C | Deviation exponent in the Markov/Chebyshev step. Coupled to k via (39); explicit choice is admissible. |

| Exponent in the small–gap threshold . Appears in the sieve bound (SGE). Any fixed suffices; we write in Lemma 8. | |

| Small–gap cutoff. Defined by . Converts the algebraic gap frequency into exponential decay in V. | |

| t | Auxiliary MGF/Chernoff parameter. Restricted to

, where

|

| V | Tail/deviation parameter. Range: in Lemma 8; with , so Gaussian-type control is available for . |

7.7. Consequences for Negative Moments

7.8. References and Remarks

7.9. Eliminating Multiple Zeros via the Entropy-Sieve Method

Hadamard Product and Log-Derivative

Dirichlet Polynomial Approximants for and

Joint MGF Bound

Joint Entropy and Exclusion of Multiple Zeros

8. Final Proof of the Negative Moment Bound

Step 1: Entropy–Sieve Tail Decay

Step 2: Chernoff Refinement and DMC+

Step 3: Exclusion of Multiple Zeros

Step 4: Dyadic Summation and Moment Bound

Quantification of the Exponent

- (1)

- the exceptional sets and , of total measure , where is a free parameter;

- (2)

- the small–gap sieve contribution, bounded by with a polynomial factor ;

- (3)

- the truncation of the dyadic summation at height , whose tail contributes .

Discussion

9. Comparison with Related Work and Motivation

Motivation for Comparison

Random-Matrix and Hybrid Euler–Hadamard Approaches

High-Moment and MGF/Chernoff Techniques

Negative Discrete Moments and Subfamily Averaging

Hejhal and Classical Distribution Results

Synthesis and Distinctives of the ESM

- Unlike the subfamily averaging of Bui–Florea–Milinovich [6], the ESM quantifies and sieves exceptional zeros, allowing us to cover (almost) the full set of zeros while maintaining quantitative tail decay.

- Compared to classical results such as Hejhal [3], our method provides explicit exceptional set bounds and parameter optimization (cf. Section 7.6), which are crucial for negative moment control.

Comparison Table

| Work | Method | Assumptions | Main output / limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hughes–Keating–O’Connell [1] | Random matrix model for | Heuristic (RMT) | Predicts conjectural asymptotics and arithmetic factors; not rigorous. |

| Hejhal [3] | Distributional analysis of | RH (for sharp results) | Approx. Gaussian law for ; limited quantitative bounds. |

| Harper [7] | Dirichlet polynomials + MGF/Chernoff | RH + pair correlation | Sharp conditional moment bounds for . |

| Kirila [4] | Discrete adaptation of Harper’s method | RH | Conditional upper bounds for discrete moments of . |

| Bui–Florea–Milinovich [6] | Subfamily averaging of zeros | RH + mild zero-spacing hypotheses | Near-optimal conditional bounds for negative moments on dense subfamilies. |

| This work (ESM) | Entropy + gap sieve + MGF/Chernoff | RH + mean-value inputs | Tail bounds for over almost all zeros; explicit exceptional set size. |

10. Conclusion

- a uniform Dirichlet-polynomial approximation with explicit coefficients and negligible remainder outside a sparse exceptional set;

- an entropy decrement analysis, ensuring that low-entropy configurations contribute negligibly;

- a small-gap sieve, suppressing the influence of unusually clustered zeros.

- Removing logarithmic losses. Pushing the admissible range of the small-gap decay parameter and extending the MGF control could potentially yield a power-saving improvement beyond .

- Higher negative moments. Extending the method to for , or to mixed moments, would deepen our understanding of the fine distribution of .

- Toward unconditional results. Incorporating recent advances in zero-density estimates or numerical pair-correlation data might relax the reliance on DMC+ and provide unconditional partial results.

- Broader applications. The entropy–sieve strategy may adapt to derivatives of automorphic L-functions and to discrete value-distribution problems in random matrix theory.

Future Research

Disclosure Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Computational Notebook and Numerical Experiments

- Compute the first M nontrivial zeros of up to height T.

- For a discretized grid of frequencies u, evaluate the exponential sum .

- Introduce thresholds for fixed constants .

- Measure the supremum .

- Fit the decay law to estimate the constant .

References

- C. P. Hughes, J. P. C. P. Hughes, J. P. Keating, and N. O’Connell. Random matrix theory and the derivative of the Riemann zeta function. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A, 2611. [Google Scholar]

- S. M. Gonek. Mean values of the Riemann zeta function and its derivatives. Invent. Math.

- D. A. Hejhal. On the distribution of log|ζ′(1/2+iγ)|. In Number Theory, Trace Formulas, and Discrete Groups, pages 343–370. Academic Press, 1989.

- M. Kirila. An upper bound for discrete moments of the derivative of the Riemann zeta-function. Mathematika, /: 1–36, 2020. Preprint available at https, 2020; 36.

- M. B. Milinovich and N. Ng. Lower bounds for moments of ζ′(ρ). International Mathematics Research Notices.

- H. M. Bui, A. H. M. Bui, A. Florea, and M. B. Milinovich. Negative discrete moments of the derivative of the Riemann zeta-function. Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, /: Preprint available at https, 2310. [Google Scholar]

- A. J. Harper. Sharp conditional bounds for moments of the Riemann zeta function. Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, 2013.

- H. Davenport. Multiplicative Number Theory, 2000; 74.

- E. C. Titchmarsh. The Theory of the Riemann Zeta-Function, 1986.

- T. Tao. The entropy decrement argument and correlations of the Liouville function. Blog post and lecture notes, /: Available at https, 2015.

- T. Tao. The entropy decrement method in analytic number theory. Lecture notes, /: 2018. Available at https, 2018.

- S. Chatterjee. A short survey of Stein’s method and entropy in large deviations. Probability Surveys.

- K. Matomäki, M. K. Matomäki, M. Radziwiłł, and T. Tao. Sign patterns of the Liouville and Möbius functions. Forum of Mathematics, Sigma.

- K. Matomäki and M. Radziwiłł. Multiplicative functions in short intervals. Annals of Mathematics, 1015.

- T. Tao and J. Teräväinen. The structure of correlations of multiplicative functions at almost all scales, with applications to the Chowla and Elliott conjectures. Algebra & Number Theory, /: 2019. Preprint available at https, 2150.

- A. M. Odlyzko. The 1020-th zero of the Riemann zeta function and 70 million of its neighbors. Preprint, /: http, 1992.

- H. L. Montgomery. The pair correlation of the zeros of the zeta function. In Analytic Number Theory, Proc. Sympos. Pure Math. 24, pages 181–193. Amer. Math. Soc., 1973.

- H. M. Bui, A. H. M. Bui, A. Florea, and M. B. Milinovich. Negative discrete moments of the derivative of the Riemann zeta-function. Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, /: 2024. Preprint available at https, 2680. [Google Scholar]

- J. Bourgain. On the correlation of the Möbius function with rank-one systems. Journal d’Analyse Mathématique, 2015; 36.

- H. Bui, A. H. Bui, A. Florea, and M. B. Milinovich. Negative discrete moments of the derivative of the Riemann zeta-function. Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 2680. [Google Scholar]

- A. M. Odlyzko, The 1020-th zero of the Riemann zeta function and 70 million of its neighbors, AT&T Bell Laboratories preprint, 1989.

- The LMFDB Collaboration, The L-functions and Modular Forms Database, http://www.lmfdb.org/zeta/.

- D. Comp. 85 ( 2016), 3009–3027.

- A. H. Barnett, J. A. H. Barnett, J. Magland, and L. af Klinteberg, A parallel nonuniform fast Fourier transform library based on an “exponential of semicircle” kernel, SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 41 (2019), no. 5, C479–C504.

- F. Johansson et al., mpmath: a Python library for arbitrary-precision floating-point arithmetic, version 1.3.0 (2023), https://mpmath.org/.

- R. Zeraoulia, Computation of Pair-Correlation Decay Constants for Riemann Zeta Zeros, Zenodo (2025). Available at: https://zenodo. 1701.

- H. M. Bui and D. R. Heath-Brown, On simple zeros of the Riemann zeta-function, arXiv preprint (2013) (Theorem: at least 19/29 zeros are simple under RH).

- P. X. Gallagher and J. H. Mueller, Pair correlation and the simplicity of zeros of the Riemann zeta-function, J. Reine Angew. Math. 306 (1979), 136–146.

- D. R. Heath-Brown, Zero density estimates for the Riemann zeta-function and Dirichlet L-functions, J. London Math. Soc. (2) 32 (1985), 1–13.

- L.-P. Arguin, P. L.-P. Arguin, P. Bourgade, M. Radziwiłł, K. Soundararajan, and M. Belius. Maximum of the Riemann zeta function on a short interval of the critical line. Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| M | T | N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 236.52 | 100 | 0.6 | 0.361 | 0.173 | 1.032 |

| 100 | 236.52 | 100 | 0.8 | 0.257 | 0.173 | 1.032 |

| 100 | 236.52 | 100 | 1.0 | 0.183 | 0.173 | 1.032 |

| 200 | 396.38 | 200 | 0.6 | 0.342 | 0.151 | 1.057 |

| 200 | 396.38 | 200 | 0.8 | 0.239 | 0.151 | 1.057 |

| 200 | 396.38 | 200 | 1.0 | 0.167 | 0.151 | 1.057 |

| Param. | Role | Typical choice | Trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Truncation length | –8 (polylog) | Larger A: smaller remainder, harder moments | |

| Approx. failure set | Bigger B ⇒ bigger A | ||

| Low-entropy set | Block length | Larger m: better entropy, costlier cumulants | |

| C | Remainder tolerance | –3 | Larger C: stronger control, bigger A |

| B | Power-saving exponent | –10 | Larger B: bigger A or higher moments |

| Small-gap sieve rate | –2 | Larger : faster decay, limited by MGF | |

| MGF tail rate | , | Fixed by X, controls linear tail | |

| m | Entropy block length | slowly | Larger m: smaller entropy set, more cost |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).