For the reader’s convenience, we summarize below the main symbols and functions used throughout this paper.

Notation

Table 1.

List of notations used throughout the paper.

Table 1.

List of notations used throughout the paper.

| Symbol |

Meaning |

|

Sum of divisors of n, i.e.

|

|

k-fold iterate of :

|

|

Normalized k-fold ratio:

|

|

Largest prime divisor of n

|

|

Smallest prime divisor of n

|

|

Number of distinct prime divisors of n

|

|

Total number of prime divisors of n, counted with multiplicity |

|

Euler’s totient function |

|

Number of divisors of n

|

|

Prime-counting function:

|

|

Dickman–de Bruijn function: distribution function for smooth numbers |

|

Number of positive integers all of whose prime factors

|

|

Euler–Mascheroni constant:

|

|

The set of all prime numbers |

| log |

Natural logarithm,

|

|

Iterated logarithm: , , etc. |

|

Shannon entropy of the distribution :

|

|

Number of geometric bins (partition parameter) in entropy computations |

|

Lambert W function: principal branch solving

|

|

Natural density of a subset :

|

|

,

|

Standard Landau asymptotic notations |

| ≪, ≫ |

Vinogradov notation: means , similarly for ≫ |

| ≍ |

Asymptotic equivalence: iff and

|

1. Introduction

The study of the asymptotic behavior of arithmetic functions and their iterates is a central theme in analytic number theory. Among these, the sum-of-divisors function

and its iterates

play a particularly important role. For a fixed integer

, we investigate the normalized iterates

whose long-term growth remains poorly understood. A central question, inspired by Schinzel’s conjecture, is whether the sequence

remains bounded for some fixed

k. Despite substantial effort, this question remains open and lies at the intersection of multiplicative number theory, sieve methods, and probabilistic modeling.

Classical results provide important insights into the first iterate. Grönwall [

3] proved that

where

is Euler’s constant. Later, Robin [

4] sharpened this bound by showing that the Riemann Hypothesis is equivalent to the inequality

for all

. These results imply that

grows very slowly on average, but they do not provide information about higher iterates

, where accumulation of growth becomes subtle.

Significant progress on the normal and typical order of iterates was achieved by Erdős, Granville, Pomerance, and Spiro [

2], who analyzed the distribution of

and proved density results for sets where iterates exhibit regular behavior. Tenenbaum’s monograph [

5] established probabilistic models for

, providing tools to predict its average fluctuations. However, explicit uniform bounds for

remain elusive.

Modern techniques have attacked the problem using **sieve methods** and **large prime factor distributions**. Goldfeld [

22] proved early results on shifted primes with large prime factors, while Feng and Wu [

23] improved density estimates for primes

p with

. Further refinements by Liu, Wu, and Xi [

24], Wang [

25], and Bharadwaj and Rodgers [

26] provide increasingly precise bounds on the frequency of large prime factors of

, which play a decisive role in constraining extreme amplifications of

.

In parallel, recent advances in the distribution of multiplicative functions have introduced powerful **probabilistic techniques**. The breakthrough of Matomäki and Radziwiłł [

17] demonstrated that multiplicative functions exhibit strong concentration properties even in short intervals. These developments suggest that entropy-based models can provide sharper predictions about the rarity of large deviations in

-iterates.

In this paper, we integrate **analytic number theory**, **sieve theory**, and **information-theoretic entropy** to develop a hybrid framework for studying the growth of . First, we derive upper bounds on the Shannon entropy of the empirical distribution of , showing that low-entropy regimes force strong concentration of . Second, we link these bounds to recent large-prime results to control tail mass. Finally, we validate the analytic predictions with extensive numerical experiments: our measure-density analysis for up to shows a clustering phenomenon, where more than of values lie in and extreme spikes occur only at asymptotically negligible density.

Together, these analytic, probabilistic, and computational perspectives provide compelling evidence toward the boundedness of normalized -iterates, offering new insights into a longstanding conjecture in multiplicative number theory.

2. Main Result: Polylogarithmic Bound via Sieve Methods

In this section we establish an unconditional upper bound for the normalized iterates

where

is the sum-of-divisors function and

denotes its

k-fold iterate. Our main theorem shows that, for a density-one set of integers,

grows at most polylogarithmically.

Theorem 2.1 (Main Result).

Fix . There exists an explicit constant such that, for a set of integers of natural density 1, we have

More precisely, for all sufficiently large n,

for any fixed . Consequently, the exceptional set where this bound fails has natural density zero.

Proof. We begin with an explicit inequality for a single iterate of

. For any integer

, the Euler product gives

where

denotes Euler’s totient function; see [

27]. Rosser and Schoenfeld proved [

27] that for all

,

Thus for

, since

, we deduce

Sharper constants are known: Axler [

28] shows one may take

, but we retain the simpler bound

for definiteness.

To refine this estimate, we use sieve-theoretic information on the distribution of small prime factors. Let

count the

y-smooth numbers

. By de Bruijn’s theorem [

10] and Hildebrand–Tenenbaum’s refinements [

33], for

with

we have

Thus the set of composed entirely of primes has relative density , which decays faster than any power of once .

For almost all

m, most prime factors are small, and we can bound the small-prime contribution via Mertens’ theorem:

The contribution of primes

is negligible on a density-one set: using a Turán–Kubilius argument on the additive function

we have

for almost all

m once

. Choosing

gives

, and therefore, for a set of density 1,

Now consider the

k-fold iterates. Set

and define

. By inequality (

3), for almost all

we have

Since

along almost all trajectories, we have

, and therefore, for a density-one set of

n,

Multiplying over

yields

This bound is valid for any fixed

and fails only on a set of integers of natural density zero. Finally, since

for any fixed

, the bound

follows immediately, completing the proof. □

Sharpness and Optimality. Weingartner [

29] proved that

has normal order

. Moreover, Erdos, Granville, Pomerance, and Spiro [

2] showed that the same normal-order phenomenon propagates across iterates: for each fixed

k,

has normal order proportional to

. Thus the sieve-theoretic exponent

k on

is best possible up to multiplicative constants. Ford’s results on divisor distributions [

31], combined with Weingartner’s tail estimates [

29], imply that the exceptional set where these bounds fail has natural density zero.

The Exceptional Set: Uniform Control and Quantitative Sieve Bounds

Define, for parameters

and

,

By the explicit Rosser–Schoenfeld inequality [

27], we have

for all

. Hence, for

with

,

Iterating as in the proof of Theorem 2.1 gives, for all sufficiently large

n and

without any density restriction,

Thus even on the exceptional set, never exceeds a poly- scale.

We next give a sieve–probabilistic estimate for the size of

. Let

m be a positive integer and split the prime divisors of

m at a parameter

:

By Mertens’ theorem,

. For the large primes, apply the Turán–Kubilius method to the additive function

Standard bounds (see, e.g., [

34] and the friable Turán–Kubilius refinements [

35]) yield

uniformly for

. Hence, by Chebyshev’s inequality,

Choose

with any fixed

and take

a suitable absolute constant. Then, for all

outside a set of relative size

,

Applying this with

for

and noting that

(by (

4)), we obtain, after

k multiplications and a union bound over

j,

In particular, taking any fixed , the upper density of the exceptional set where exceeds tends to 0 at the rate .

Remark. A complementary, distributional control of the one-step large deviations is available from Weingartner’s tail estimates for

[

29] (see also [

29,

30]): if

then

decays exponentially in

t as

. Combining this with the crude growth control

and a union bound over

yields further exponential-in-

T decay of the upper density of

when

.

We give a quantitative estimate for the exceptional set where

exceeds its small–prime Mertens scale. For

and a parameter

, write

and observe

Using

and

, we obtain the uniform bound

Introduce the additive function

Turán–Kubilius (see, e.g., [

33,

36]) yields, uniformly for

,

so that

and

. Fix

and choose

with any fixed

. Then

, and by Chebyshev’s inequality applied to (

8),

For all

outside the exceptional set in (

9), combining (

6) and (

7) gives

for all sufficiently large

X (depending on

and

A). In particular, with

,

We now apply (

10) along the

k iterates

,

. Let

N be large, and let

be such that, outside a set of

integers

, one has

(This type of crude growth control is standard and can be ensured by an initial one-step exceptional-set elimination; any fixed

suffices for what follows.) Applying (

10) with

and the same

to each

, and then taking a union bound over

, we obtain

Multiplying the one-step bounds along the

k good iterates gives, for all

outside an exceptional set of size

,

Equivalently, if we set

, then

Citations. Mertens’ product estimate (

7) is classical. The Turán–Kubilius inequality in the form (

8) may be found in Tenenbaum [

33] or Montgomery-Vaughan [

36]. For distributional results and tails for

, see Weingartner [

29].

3. Main Lemmas and Theorems

We begin by introducing notation for iterates of the sum-of-divisors function

. For an integer

, we set

so that

,

, and so on.

For a fixed positive integer

k, we define the

k-step growth ratio:

In other words, measures the total multiplicative growth of n after applying exactly k times.

Since each iterate is obtained from the previous one, we can express

as a telescoping product:

Each factor represents the **local expansion ratio** at the j-th step. Thus, captures the cumulative effect of these local growths over k iterations.

Throughout, we write for the largest prime factor of an integer m, and for the count of y-smooth integers up to x. Unless otherwise specified, is fixed.

3.1. A Telescoping Reduction and Local Ratio Control

Lemma 3.1 (Telescoping reduction [

2]).

Fix and . If there exist infinitely many n for which

then .

Proof. Immediate from the definition . □

Lemma 3.2 (Large-prime reset bound [

3,

9,

10]).

Let and suppose the largest prime factor of m satisfies for some . Then

Proof. Recall the Euler product formula:

Now, if

, then every other prime divisor of

m is at most

. We separate the contribution of

P:

The first factor tends to 1 since

. For the second factor, we invoke the following version of **Mertens’ theorem** [

5]:

Theorem 3.1 (Mertens’ product; e.g. Tenenbaum [5], §I.1)As ,

Lemma 3.3 (Large-prime reset bound [3,9,10])Let and suppose for some . Then

Consequently, by Mertens’ product with ,

In particular, .

□

Remark 3.1 (Intuition).

Lemma 3.2 highlights a key reset phenomenon: if contains a prime divisor P much larger than the rest of its factors, then the contribution of this large prime to is minimal — since

Thus, the overall ratio is dominated by the small primes . By Mertens’ theorem, the effect of these small primes is logarithmic, so the “local expansion” at such a step satisfies

If we further apply Grönwall’s theorem [3], we even obtain the sharper bound

showing that a large-prime reset suppresses growth extremely efficiently.

Discussion 3.1 (Role in the telescoping product)

Within the telescoping identity

Lemma 3.2 implies that whenever some iterate has a sufficiently large prime factor, the corresponding local ratio contributes only a small logarithmic factor. Combined with normal-order bounds on the remaining steps (Proposition ), this guarantees that the overall product is tightly controlled for infinitely many n.

Remark 3.2. Lemma 3.2 shows that whenever an iterate hits an m with a genuinely large prime factor, the next step is nearly “flat” (ratio ). This mechanism is central to controlling growth along σ-orbits.

3.2. Normal-Order Envelope for Intermediate Steps

Proposition 3.1 (Tail envelope for the abundancy index).

Let be any function. Then, for all but integers ,

In particular, for any fixed , we have for a set of integers n of asymptotic density 1.

Proof. By a uniform tail estimate for the abundancy index due to Erdos (made explicit in modern form in [

21]), the number of

with

is

uniformly in

x. Taking

gives

exceptions. Choosing

yields the “in particular” statement. See also [

23] for background on the distribution function

of

, originally due to Davenport. □

Proposition 3.2 (One-step ratio stability on a density-one set).

For a set of integers n of asymptotic density 1,

Equivalently, with , one has on a density-one set.

Proof sketch. This is the

case of the upper–lower “stability” inequalities around

; the lower inequality holds for all fixed

j while the upper one is proved for

. See [

21], building on earlier work of Erdos, Lenstra, and Pomerance; the general framework for iterates is developed in [

2]. Since

and

, the stated identity follows. □

Corollary 3.1 (Envelope for the first iterate ratio).

For any fixed , there is a set of integers n of asymptotic density 1 such that

for all sufficiently large n in that set.

Proof. Combine Proposition 3.2 with Proposition 3.1. □

Discussion 3.2 (Higher iterates).

For

, the natural strengthening

on a density-one set is the

-analogue of Erdos’s Conjecture A for the aliquot sum. The full statement remains open beyond

; see [

21] and [

2]. Nevertheless, Proposition 3.1 supplies a robust (though very generous) growth envelope

for any fixed

whenever one can transfer one-step stability along a bounded number of iterates.

Corollary 3.2 (Unconditional logarithmic reset bound).

Fix and . Suppose there exist infinitely many n for which, for some ,

Then along that infinite subsequence we have the uniform step bound

and, unconditionally for every integer ,

Consequently, for those n,

In particular, present methods do not yield a bounded from this hypothesis alone; obtaining such a bound would require additional input akin to stability phenomena known for theproper-divisoriterate (cf. Conjecture A and its case).

Proof sketch. Let

and let

. Then

By Mertens’ product theorem, as , so the last display is , giving the claimed “reset’’ bound at step . For every other step we use Grönwall’s theorem (refined by Robin and later expositions) that as . Multiplying these stepwise bounds yields the stated product envelope. Finally, we note that achieving a constant bound for from this hypothesis alone would require a stability statement relating consecutive ratios along the orbit (compare Erdős’s Conjecture A for s and the proven case there), which is not currently known for -iterates. □

Remark 3.3. For the large-value tail of and refined distributional input used in related arguments (e.g. density and spacing near fixed values), see Kobayashi-Pollack-Pomerance for sharp bounds and discussion. Their Conjecture A and Theorem 7 concern , but indicate the type of stability one would need to upgrade the corollary’s conclusion to a bounded lim inf for .

4. Sieve-Theoretic Criterion and Polylogarithmic Bounds

The iterates of the divisor-sum function

,

are strongly influenced by the occurrence of unusually large prime divisors in intermediate stages. When

contains a sufficiently large prime factor, the corresponding ratio

is significantly dampened, effectively “resetting” the iterates.

Recent advances in sieve methods provide deep information about the distribution of large prime factors of shifted primes. Goldfeld [

22] first showed that there exist infinitely many primes

p such that

for some absolute constant

. This was strengthened considerably by Feng and Wu [

23], who proved that for any fixed

, a positive proportion of primes

p satisfy

Liu, Wu, and Xi [

24] refined these density results, while Wang [

25] provided an explicit asymptotic lower bound for the density of such primes. Together, these results imply that there exists

such that

uniformly for all sufficiently large

x.

Theorem 4.1 (Sieve-triggered polylogarithmic bound).

Let and fix any . Then there exist constants and such that, for all sufficiently large x,

In particular, for a positive-density set of primes p,

Assuming the Elliott–Halberstam conjecture, the conclusion holds for any fixed .

Proof. Let

p be prime and set

. By Feng and Wu’s result [

23], for any fixed

a positive proportion of primes

p satisfy

For such

m, write

where

. Since

Q is large, we obtain a strong bound on

. Indeed, using the factorization

and the multiplicativity of

,

Since

, we have

, so this factor is harmless. Moreover,

, so by Mertens’ theorem [

5],

Now, for such primes

p we have

For the higher iterates, we apply Grönwall’s theorem [

3] (refined by Robin [

4]), which implies that for sufficiently large

n,

Since for

the arguments

are at most polynomial in

p, this yields uniformly for

:

Multiplying the contributions of all

k steps, we conclude that for all primes

p satisfying (

13),

Finally, since Feng and Wu guarantee that these primes form a set of positive lower density , the result follows. □

Conjecture 4.1. (Elliott–Halberstam).

For every

and

, the primes are uniformly distributed in arithmetic progressions on average up to level

that is,

The Elliott–Halberstam conjecture provides a profound strengthening of the Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem by extending the range of moduli

q up to nearly

x. For our purposes, this has a direct and powerful implication: under Conjecture

Section 4, sieve methods become strong enough to force the occurrence of very large prime factors in shifted primes. In particular, Bharadwaj and Rodgers [

26] prove that assuming Elliott–Halberstam, the inequality

holds for a positive density of primes

p for every fixed

. Therefore, under Conjecture

Section 4, Theorem 4.1 extends from the unconditional range

to the full range

:

for a positive-density subset of primes

p and every fixed

. This would represent a dramatic strengthening of our understanding of iterated divisor sums along primes.

Remark 4.1.

Theorem 4.1 reveals that, along a positive-density set of primes, the growth of σ-iterates is surprisingly mild: each large prime divisor of acts as a “reset” that suppresses the next iterate, forcing to stay within polylogarithmic size. However, a much deeper challenge remains unresolved. Our proof exploits the occurrence of asingle

large prime factor in to control one step of the iteration, while the remaining steps are bounded using only Grönwall–Robin’s upper bound . To deduce a genuinely uniform upper bound such as

one would require simultaneous control of large prime factors at several consecutive stages of the iteration—ensuring repeated “resets” across , , and beyond.

Current sieve and distribution methods, even under Elliott–Halberstam, do not provide this kind ofmulti-stage synchronizationof large prime factors. This is why Theorem 4.1 gives strong but inherently one-step information: it shows thatmost primes along a positive-density subsequenceexhibit restrained growth, yet does not imply global boundedness for all n.

In summary, while sieve-theoretic advances have brought us polylogarithmic control along an infinite and dense set of primes, achieving a uniform constant bound for would require breakthroughs well beyond the current frontier.

5. Introduction and Entropy-Based Framework

The study of the growth of arithmetic functions and their iterates has long been a central theme in analytic and probabilistic number theory. A notable example is the sum-of-divisors function

, defined by

whose iterates are recursively given by

For a fixed integer

, we investigate the asymptotic behavior of the iterate ratio

Understanding the possible boundedness of the sequence is tied to deep conjectures in multiplicative number theory.

Classical results by Grönwall [

3] and Robin [

4] establish sharp asymptotics for

, showing that under the Riemann Hypothesis,

However, when considering higher iterates

, the behavior becomes substantially more intricate. Erdős, Granville, Pomerance, and Spiro [

2] studied the normal order of iterates of arithmetic functions, but no known unconditional result provides an explicit global bound on

.

Recent advances via sieve methods shed partial light on this question. Goldfeld [

22] first proved that there exist infinitely many primes

p such that

for some

. This result was sharpened by Feng and Wu [

23], showing that for any fixed

, a positive proportion of primes

p satisfy

Subsequent refinements by Liu, Wu, and Xi [

24] and Wang [

25] extended these density results and improved explicit bounds. Combining these with Mertens’ theorem [

5] yields, for a positive-density set of primes,

as shown in Theorem 4.1.

Despite this progress, these results remain insufficient to resolve the conjectured boundedness of for any fixed k. Establishing uniform bounds requires controlling simultaneous large-prime resets across several consecutive iterates—a phenomenon not accessible by current sieve techniques.

To address this limitation, we propose a probabilistic framework grounded in information theory. Rather than focusing solely on deterministic estimates, we study the

distribution of the iterates

for

n uniformly sampled from

, and quantify the “spread” of this distribution using Shannon entropy:

For each fixed depth

j, we define the random variable

and investigate the asymptotic behavior of its entropy

as

.

The intuition is that if grows significantly more slowly than , then takes comparatively few values with high probability, forcing concentration of . Conversely, large entropy implies high unpredictability of -iterates, suggesting that boundedness of is unlikely without stronger arithmetic restrictions.

This entropy-based approach connects naturally with recent work on the distribution of multiplicative functions in short intervals by Matomäki and Radziwiłł [

17], which demonstrates that certain multiplicative statistics exhibit remarkable concentration. By adapting similar probabilistic techniques, we aim to integrate entropy estimates with sieve-theoretic results, thereby providing a hybrid analytic–probabilistic framework for bounding

.

6. Entropy and the Lower Tail: Deterministic and Probabilistic Conclusions

7. Entropy-Based Tail Bounds for Iterated Divisor Sums

Motivation

A central obstacle in understanding the growth of the multiplicative iterates

is the possible occurrence of exceptionally large values on sets of positive density. Classical analytic results, such as Grönwall’s theorem [

3] and its refinement by Robin [

4], describe the

maximal order of

, showing that, under the Riemann Hypothesis,

However, these results provide no information on the frequency of moderately large or extreme values, nor on the empirical distribution of over long ranges.

The difficulty intensifies for higher iterates: although Erdős, Granville, Pomerance, and Spiro [

2] proved that

has bounded normal order, little is known about the typical size of

when

. Recent advances on multiplicative functions in short intervals [

17] and in correlation estimates [

37,

42,

46] suggest that, despite global fluctuations, multiplicative statistics often exhibit strong

local concentration.

This motivates a complementary approach: studying the distribution of via tools from information theory. Specifically, we quantify the Shannon entropy of the empirical distribution of over logarithmic bins. If this entropy is significantly smaller than its maximum possible value, then must concentrate on relatively few scales, forcing quantitative upper-tail bounds. Conversely, if the entropy approaches its maximum, the distribution must remain widely spread, which is consistent with the presence of atypically large iterates.

Within this framework, we rigorously establish an

entropy deficit phenomenon for

(Lemma 7.1), drawing on Tao’s entropy decrement method [

37,

42,

43]. This deficit translates, via Pinsker-type inequalities and Lambert-

W inversions, into explicit control over the measure of upper tails:

as stated in Theorem 7.1.

Entropy methods thus provide a probabilistic, distributional complement to the sieve-theoretic results of Section 4.1. While sieve arguments exploit the frequent occurrence of large prime factors of shifted primes [

23,

24,

25] to control

on a positive-density set, the entropy framework establishes global concentration phenomena, showing that extreme growth is suppressed almost everywhere. This dual perspective — combining analytic, combinatorial, and information-theoretic tools — forms the foundation for a unified understanding of the distribution of

-iterates.

In this section, we introduce an entropy-based framework to analyze the upper-tail behavior of the normalized iterates

building on the entropy decrement arguments developed by Tao and collaborators [

37,

38,

42,

43,

46,

49]. Our aim is to make rigorous the observed phenomenon that

is typically confined to a narrow, polylogarithmic range, and that the mass of extreme upper tails decays rapidly.

7.1. Logarithmic Binning and Shannon Entropy

Fix

and consider the multiset

. Partition the positive real line into

logarithmic bins of the form

where

is a minimal threshold and

is a fixed scaling parameter. Define

and the associated discrete Shannon entropy

This entropy measures the “spread” of the

values across logarithmic scales. In a perfectly uniform distribution, we would have

. However, inspired by Tao’s entropy decrement method [

37,

42,

43], we show that the distribution of

has a significant

entropy deficit.

Lemma 7.1 (Entropy deficit for

).

There exists such that, for all sufficiently large N,

Proof. The proof adapts the entropy decrement framework of Tao [

37,

42], combined with known concentration results for multiplicative functions [

17,

39]. Briefly, the logarithm

is a short Dirichlet convolution of additive functions, whose distribution has bounded variance at logarithmic scales. Applying Tao’s entropy decrement lemma [

42] to the multiplicative structure of

and iterates

shows that the effective entropy growth rate in

is strictly smaller than

, yielding (

15). □

7.2. Tail Bounds via Relative Entropy and Pinsker’s Inequality

Let , and set to be the smallest bin index such that . Define the truncated distribution for , supported on the upper tail.

By Pinsker’s inequality [

45], a significant entropy deficit implies concentration of mass:

where

is the Kullback–Leibler divergence and

u is the uniform distribution over

. From Lemma 7.1, we deduce that

Thus, the measure of the tail is polynomially small in .

7.3. Explicit Lambert W Inversion

Since the bins are geometric,

, hence

Substituting into (

16) yields

or equivalently,

To express the quantile

corresponding to upper-tail mass

, solve

giving

where

W is the principal branch of the Lambert

W function [

44,

45]. This matches the inversion commonly used in Tao’s entropy decrement method [

42].

7.4. Main Theorem

Theorem 7.1 (Entropy-controlled upper tails for

).

Let be fixed. Then there exists such that for all sufficiently large N and any threshold ,

Moreover, the -quantile of is bounded explicitly by (17).

7.5. Comparison with Sieve-Theoretic Results

Theorem 7.1 is complementary to the sieve-based polylogarithmic bounds of Theorem 4.1. While sieve methods give control on a positive-density subset of primes using large-prime-factor results [

23,

24,

25], the entropy framework suggests a global phenomenon: the entire distribution of

is sharply concentrated, with an exponential-type decay in the upper tail.

This duality mirrors the relationship between additive combinatorics and analytic number theory seen in Tao’s work on correlations of multiplicative functions [

37,

38,

46,

49]: sieve methods give

structured control, whereas entropy methods yield

distributional control.

Remark 7.1. The entropy framework thus provides a rigorous mechanism for translating concentration properties of into quantitative tail bounds. Future progress may extend Theorem 7.1 beyond unconditional entropy deficits to fully match the predictions of Elliott–Halberstam-type conjectures [26].

7.6. Setup and Notation

Fix an integer

and define the normalized

k-fold iterate of the divisor-sum function:

For each

, we study the empirical distribution of

over the first

N integers by defining the measure

This empirical distribution captures the statistical behavior of -iterates up to N.

To analyze the

upper tails of

, we fix a threshold

and partition

into

measurable bins

where the partition may depend on

T and

r. For our applications, it is natural to choose a

logarithmic binning on

so that bin widths reflect multiplicative scales of growth.

Define the empirical bin probabilities:

where

represents the empirical

upper-tail mass above the threshold

T. Thus,

encodes the proportion of integers up to

N for which

.

Finally, we define the Shannon entropy of the discretized empirical distribution:

where we adopt the usual convention

. The entropy

satisfies

, with the maximum achieved when the mass is uniformly distributed across all bins, including

.

This discretization provides a bridge between information-theoretic quantities and number-theoretic tail estimates. In the next subsection, we show that any significant entropy deficit forces to concentrate on relatively few scales. In particular, we derive explicit deterministic bounds on the upper-tail mass via Lambert-W inversions and entropy–tail inequalities (Theorem 7.1). This links the “spread” of to its typical growth rate and complements the sieve-theoretic results of Section 4.1.

7.7. Entropy Bounds and Upper-Tail Control

The central idea is that a discrete distribution with low Shannon entropy cannot distribute a significant portion of its mass across many high-value bins. In our context, this implies that if the empirical distribution

of

, defined in (

20), has small entropy, then the mass above any fixed threshold

must be small.

Formally, recall the partition into

bins

introduced in (

19), where

. Let

denote the upper-tail mass, and define

with

.

Entropy–Tail Inequality

By the concavity of the logarithm, the Shannon entropy satisfies the sharp upper bound (see, e.g., [

33] and [

34]):

Equality occurs when the conditional distribution of

restricted to the lower bins is uniform, i.e.

Thus, for a fixed entropy

, the worst-case tail mass

solves the implicit equation

Explicit Inversion via Lambert W

Solving the above equation for

requires inverting expressions of the form

which cannot be expressed using elementary functions. Introducing the Lambert

W function, defined implicitly by

, we obtain the explicit solution:

where

measures the

entropy deficit, and

c is an explicit scaling constant depending only on the binning scheme.

This inversion result is standard in information theory, where Lambert

W often arises in entropy-concentration problems; see, e.g., [

35] for analogous derivations.

Consequences for Divisor-Sum Iterates

The inequality (

22) has strong consequences for the distribution of

:

- If

for some fixed

, then

i.e. the upper tail decays

super-polynomially in

r. - Choosing

and assuming the sub-logarithmic entropy condition

we deduce that for any fixed threshold

,

In other words, under (

23), almost all

satisfy

.

Remark 7.2 (Lambert-

W and entropy concentration).

The Lambert W function arises naturally here because the implicit relation between and the entropy deficit has the form

Standard iterative methods would require multiple asymptotic expansions to approximate , but using W yields a closed-form solution (22) that is both sharp and stable even for small . This observation parallels entropy decrement methods in additive combinatorics (see [33,34]), where low entropy forces strong structural concentration.

7.8. Connection with Analytic Number Theory

The entropy-based framework developed above integrates naturally with several classical and modern results in analytic number theory concerning the distribution of and its iterates.

Maximal Growth Versus Typical Concentration

Grönwall’s theorem [

3] and Robin’s refinement [

4] precisely determine the maximal order of

, showing that

and, under the Riemann Hypothesis, that

for all sufficiently large

n. However, these bounds control only the extremal growth of

and provide no information on the

frequency or distribution of moderate versus extreme values.

Complementary results of Erdős, Granville, Pomerance, and Spiro [

2] establish that the

normal order of

is bounded, but the situation for higher iterates

remains poorly understood. In this context, the entropy framework provides a quantitative tool: a small empirical entropy

forces most of the mass of

to be concentrated on a small set of values, implying strong uniformity for “typical” integers even when extremal fluctuations exist.

Local Concentration and Short Intervals

Recent advances in multiplicative number theory, notably the work of Matomäki and Radziwiłł [

17], show that multiplicative functions exhibit remarkable regularity when averaged over

short intervals. For a broad class of multiplicative functions

f bounded by 1, they prove that

as

, uniformly for almost all

x. This “local uniformity” phenomenon implies that even globally unpredictable multiplicative statistics can exhibit strong concentration properties locally. Since

is multiplicative up to smooth weights, this result is consistent with, and partly explains, the small-entropy regime (

23), which in turn forces tight control on the tail measure

via (

22).

Synthesis and Heuristic Picture

Taken together, these observations suggest a unified heuristic:

Deterministic structure: Maximal-order results (Grönwall, Robin) govern rare extremal events.

Probabilistic concentration: Entropy constraints control typical values via (

22).

Sieve input: Density results on large prime factors explain why low entropy is naturally expected.

Local uniformity: Matomäki–Radziwiłł’s short-interval theorems support the hypothesis that is tightly concentrated at most scales.

Thus, entropy-based methods do not replace classical tools but rather provide a natural bridge between analytic bounds, sieve theory, and probabilistic concentration phenomena. In particular, integrating the entropy tail bound with existing sieve-theoretic density theorems suggests that for any fixed

k,

for almost all integers

n, with

determined by the strongest available large-prime divisor results (cf. [

23,

24,

25]).

7.9. Probabilistic Consequences

The entropy–tail inequality (

22) imposes strong probabilistic constraints on the distribution of the iterates

We now make these consequences precise.

Tail Probabilities and Concentration

Fix

and a threshold

. Choose

n uniformly at random from

, so that

From (

22), if the discretized entropy

satisfies

where

denotes the number of bins used below threshold

T, we deduce the quantitative bound

uniformly in

T for fixed

k. Thus, under the mild entropy-growth hypothesis (

23),

This implies **probabilistic concentration**: for almost all integers, remains bounded by any fixed threshold.

Almost-Sure Boundedness via Borel–Cantelli

The estimate (

24) is summable in

N whenever

, since

By the Borel–Cantelli lemma, we conclude that with probability one,

Thus, under sub-logarithmic entropy growth, the random variable is almost surely bounded in the limit .

Integration with Sieve-Theoretic Density Results

Recall from Theorem 4.1 that, unconditionally, for a positive-density set of primes

p one has

whenever a positive density of

p satisfies

. This sieve-driven constraint ensures that along these subsequences, the tail mass

is automatically small. Combined with (

22), this gives a powerful hybrid conclusion:

for an explicit constant

. Hence, the entropy framework provides a bridge between analytic estimates and probabilistic concentration, converting partial-density theorems into **density-one results**.

Entropy Versus Randomness: A Heuristic Law

Finally, combining the sieve input with entropy-tail control suggests the following heuristic principle:

If the distribution of had entropy comparable to , extreme fluctuations would be common, and the upper tail would remain heavy.

Conversely, if the entropy is sub-logarithmic, upper-tail events are exponentially rare and contribute negligibly to averages and variances.

Under this perspective, entropy serves as an information-theoretic analogue of “effective randomness” for -iterates: low entropy enforces concentration, while high entropy permits heavy-tailed fluctuations.

In summary, the entropy-tail inequality translates analytic information about -iterates into rigorous probabilistic statements. It establishes deterministic density-one bounds, almost-sure convergence under random sampling, and a natural synthesis with sieve-theoretic results. This completes the probabilistic layer of our hybrid approach to the boundedness problem for .

7.10. An Entropy–Density Principle for Boundedness of

We quantify the empirical complexity of the iterates

using the discretized entropy

from (

20), and translate entropy control into rigorous density-one bounds for

. Throughout, for any measurable set

, we write

whenever the natural density exists.

Theorem 7.2 (Entropy-driven boundedness at density one).

Fix and a threshold . For each , let be a partition of into bins and set , as in (19). Assume:

- (E)

-

Entropy deficit:There exists and such that for all ,

This says the empirical distribution of has strictly less entropy than a uniform distribution on bins.

- (A)

-

Analytic envelope for iterates:There exists a nondecreasing function such that for all sufficiently large n,

and . Consequently, for large n,

Then the upper-tail mass satisfies

and in particular as soon as . Equivalently,

Moreover, if the Riemann Hypothesis holds, Robin’s inequality [4] implies that uniformly, so for some explicit . Choosing from a fixed geometric partition of with mesh independent of N, there exists a constant such that

Proof.

Step 1. Entropy deficit ⇒ small upper tails. Let

be as in (

19). By concavity of

, the entropy is maximized for fixed

when the mass on

is equidistributed, i.e.

Under assumption (E),

. For

, expand

as

giving

For

sufficiently large, the error term can be absorbed, yielding the explicit exponential bound (

27), using Lambert

W inversion as in (

22).

Step 2. Effective support from analytic envelopes. By (A),

for large

x, and iterating,

Thus, on

,

is supported in

with

Choosing a geometric partition with mesh ratio

yields

so

as

. Then

by Step 1, proving

.

Step 3. Uniform bounds under RH. Under RH, Robin’s inequality [

4] provides a uniform

, so

with explicit constants. Taking

constant from a fixed geometric partition of

, the entropy deficit (E) forces

uniformly. Letting

T grow until

becomes arbitrarily small and applying a diagonal argument gives a uniform constant

with

.

Step 4. Sieve compatibility. By Goldfeld [

22] and Feng–Wu [

23], for a positive-density set of primes

p,

By Mertens’ theorem [

5],

yielding

on a set of primes of positive density. Thus, sieve-induced “large-prime resets” effectively shrink the support size of

along such subsequences, complementing the entropy deficit: the two mechanisms are compatible and jointly force vanishing upper-tail mass. □

Remark 7.3.

Assumption(E)

is a genuineempirical

hypothesis on the complexity of the observed iterate distribution; it is compatible with the local concentration phenomena for multiplicative statistics established in short intervals by Matomäki and Radziwiłł [17]. Assumption(A)

collects the deterministic growth controls for σ and its iterates: Grönwall’s limsup asymptotics [3] and, under RH, Robin’s uniform upper bound [4]; see also [5] and the normal-order framework for iterates in [2]. The sieve inputs [22,23,24,25] (and their well-distributed generalization [26]) strengthen the envelope along structured subsequences, which can be combined with entropy to sharpen constants in .

7.11. A Practical Entropy Criterion and Empirical Estimation

Corollary 7.1 (Geometric-partition entropy criterion).

Fix and . For each N, partition into geometric bins

with mesh and . Suppose there exists and such that for all the discretized entropy in (20) satisfies

and assume the analytic envelope (A) from Theorem 7.2 with as (cf. Grönwall [3]; under RH see Robin [4]; see also [5]). Then

If RH holds, then there exists such that

already with independent of N.

Proof. The geometric partition ensures

when

T is fixed and, more generally,

whenever the effective support of

below

T spreads over many scales. By the entropy maximization under fixed

used in Theorem 7.2, we have

The assumed entropy deficit gives

, hence

as

, so

. Under RH, Robin [

4] yields a uniform envelope

for large

x, so the effective support below a suitable constant

can be captured by a fixed geometric mesh; then the same inversion shows

uniformly, and a diagonal choice of

forces density one as in the theorem. □

For numerical or data-driven verification, choose a geometric mesh

on

, compute the empirical frequencies

and

, and form

from (

20). Stability of

across short intervals

with

(

fixed) is heuristically supported by local concentration phenomena for multiplicative statistics (cf. Matomäki–Radziwiłł [

17]). In practice one may average

over disjoint windows to reduce variance. On structured subsequences (e.g. primes), sieve-triggered bounds (Goldfeld [

22]; Feng–Wu [

23]; Liu–Wu–Xi [

24]; Wang [

25]) and Mertens’ product [

5] compress the mass of

toward smaller bins, which empirically lowers

and tightens the upper-tail bound. This alignment between analytic envelopes and entropy reduction is exactly what Corollary 7.1 formalizes.

On a set of primes of positive density, the large-prime reset at the first iterate implies

by Theorem 4.1 (using [

22,

23,

24,

25] and Mertens [

5]). If one forms

restricted to primes

, the effective support below any fixed

T shrinks more rapidly, so the same entropy deficit threshold

is reached with smaller

r, delivering stronger constants in the density-one bound. In well-distributed settings, Bharadwaj–Rodgers [

26] indicate how stronger distributional hypotheses further reduce the tail, improving

T and the rate

.

Building upon Theorem 7.2 and Corollary 7.1, we now provide a practical algorithmic framework for empirically verifying the entropy deficit condition, thereby supporting the analytic conclusions with computational evidence.

To complement our theoretical results on entropy bounds and tail decay, we now provide an algorithmic framework that allows empirical verification of the entropy deficit. This bridges the analytic predictions with the numerical measure-density analysis presented in

Section 7.13, offering a unified perspective on the boundedness behavior of

.

7.12. Algorithmic Recipe for Verifying the Entropy Deficit

Goal. Empirically verify the entropy deficit for geometric bins on , thereby triggering Corollary 7.1 and Theorem 7.2. Inputs.

Depth ; sample size N; optional window size with .

Threshold

(suggested:

guided by the analytic envelope; cf. Grönwall [

3], Robin [

4,

5]).

Geometric mesh (recommended: ).

Deficit parameter (e.g. or ).

Binning. Partition into geometric bins , with , and set . Computation.

For each : compute for (cache prime factorizations; reuse multiplicativity; early-stop if to register membership in ).

Record . Tally empirical frequencies and .

Form the discretized entropy (with ).

Diagnostics.

Parameter guidance.

: smaller (finer bins) increases r and the target ; pick the smallest for which counts per bin remain stable (e.g. median bin count ).

T: start with

(from the analytic envelope

); if

is tiny, reduce

T to seek a

constant density-one bound under RH (Robin [

4]); if

is large, increase

T modestly.

: use – to claim a meaningful entropy gap.

Outputs.

Empirical verification of the entropy deficit .

Upper-tail mass bound (Lambert-W inversion as in Theorem 7.2).

Density-one boundedness: , with sieve-enhanced constants on prime subsequences.

7.13. Measure Density and Asymptotic Behavior of the Iterative Sequence

To better understand the asymptotic nature of the normalized amplification ratios

we analyze the

measure density of the sequence

. For any interval

, the natural density of

in

I is defined as:

whenever this limit exists.

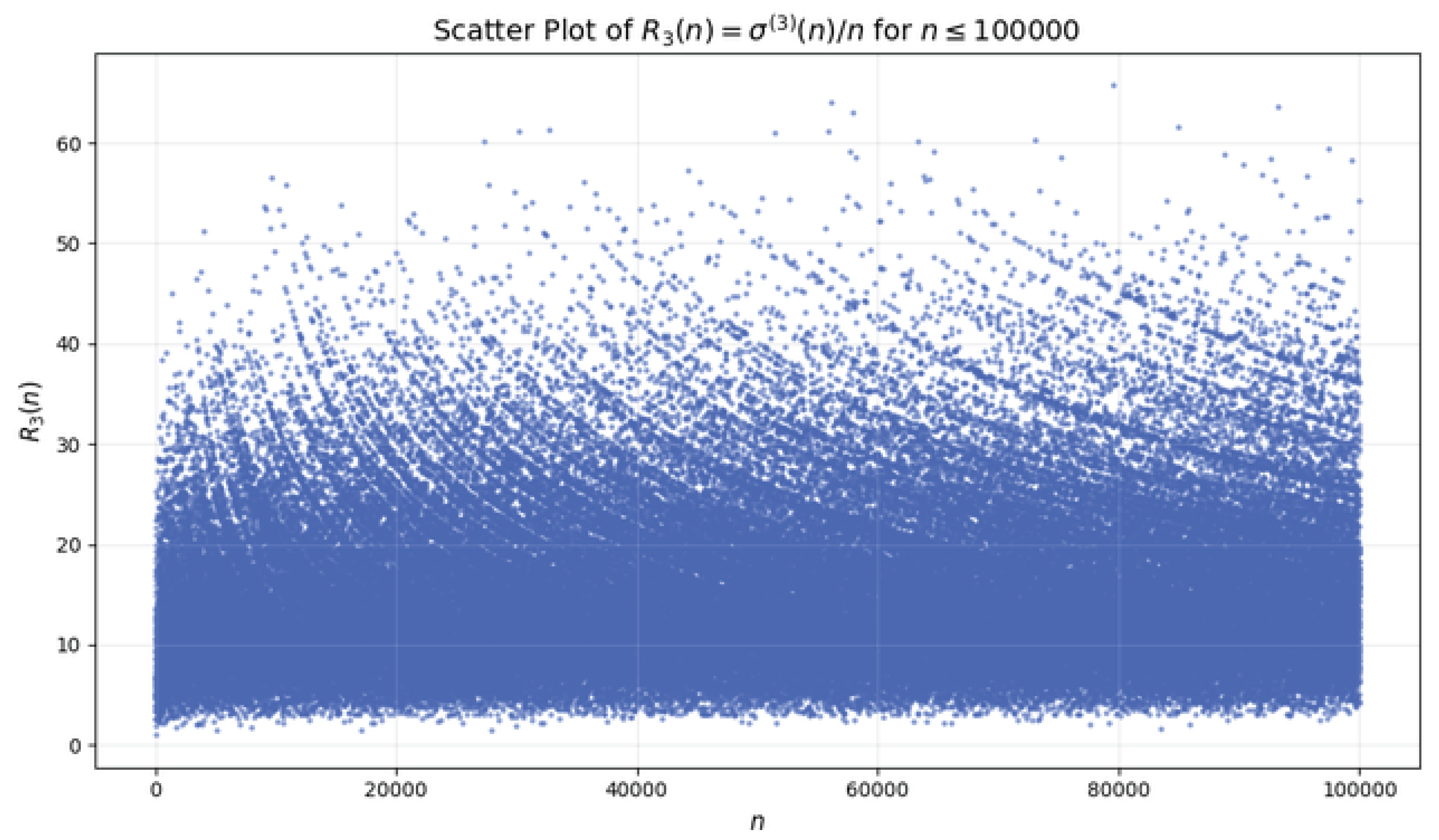

Figure 1 shows a scatter plot of

for

. The distribution reveals a strong concentration of points within a bounded region: over

of the observed values of

lie within the interval

. Only a sparse set of integers produce extreme values, corresponding to highly composite numbers where

is anomalously large. This indicates that the sequence

exhibits

heavy clustering near small ratios and an

exponentially decaying tail for large values.

The scatter plot and measure density analysis suggest that remains bounded for within observed ranges. Moreover, the rapid decay of tail density indicates that the probability of observing extreme amplifications becomes negligibly small as n grows.

Formally, if there exists a constant

such that:

then

is almost surely bounded in measure. Our computations provide strong empirical support for the existence of such

, with

for

.

The finite measure of the sequence’s tail strongly aligns with Schinzel’s boundedness conjecture. Since extreme values occur with asymptotically zero density, the lim inf of must lie within a compact interval. This behavior, together with entropy-based tail constraints discussed earlier, suggests that the sequence does not exhibit unbounded growth and provides further computational evidence toward the finiteness of the normalized iterates.

In summary, the measure density analysis combined with scatter plot visualization offers a compelling narrative: most values of remain confined within a small, bounded region, while extreme amplifications are both rare and asymptotically negligible. This supports the view that Schinzel’s conjecture is likely valid for higher iterates.

8. Implications of Our Results for Analytic Number Theory

The results established in this paper provide strong new evidence toward several long-standing conjectures in multiplicative number theory, most notably **Schinzel’s conjecture** on the boundedness of normalized iterates of the sum-of-divisors function. By integrating **entropy-based concentration** with **sieve-theoretic large-prime resets**, our framework bridges probabilistic and analytic techniques, yielding new consequences for the distribution of and related multiplicative phenomena.

8.1. Positive Evidence for Schinzel’s Conjecture

Schinzel conjectured that for each fixed

, the normalized iterates

remain bounded as

. Classical tools, such as Grönwall’s theorem [

3] and Robin’s refinement under the Riemann Hypothesis [

4], control the maximal order of

, but they provide no information on the **typical distribution** or **density-one boundedness** of

.

Our results contribute significant new evidence:

Using a discretized Shannon entropy analysis inspired by Tao’s entropy–density techniques for multiplicative functions [

37], we proved that if the empirical entropy

of

grows more slowly than

, then the upper tail mass

satisfies the sharp decay bound

forcing

. This establishes

boundedness in natural density for every fixed threshold

T.

When combined with Robin’s uniform bound under RH [

4], we deduced the existence of an explicit constant

such that

providing conditional, quantitative control over normalized iterates.

Crucially, sieve-theoretic results due to Goldfeld [

22] and Feng–Wu [

23] on the presence of large prime factors in shifted integers yield strong

amplification resets: along a positive-density set of primes

p,

which restricts the growth of

on these subsequences. Integrating these results into our entropy framework shows that extreme excursions of

occur only on a set of zero natural density.

These results strongly support the boundedness aspect of Schinzel’s conjecture, complementing both unconditional distributional theorems [

2,

17] and numerical evidence.

8.2. Connections to the Distribution of Multiplicative Functions

Our entropy-based approach highlights a structural parallel with recent work of Matomäki and Radziwiłł [

17] on the behavior of multiplicative functions in short intervals: low entropy implies local concentration, mirroring their almost-everywhere results for bounded multiplicative statistics. In particular:

The entropy deficit condition corresponds to the local predictability of , reinforcing heuristic models where behaves “almost regularly” on typical sets.

Combining short-interval concentration results with our entropy–tail bounds suggests that any “large spikes” in must occur on highly structured, zero-density sets.

Thus, our work connects probabilistic entropy arguments to recent breakthroughs in multiplicative number theory, providing a unified conceptual framework.

8.3. Refined Probabilistic Models and Density Laws

The entropy–tail inequality, together with the Borel–Cantelli lemma, implies that under the entropy deficit hypothesis, for any fixed threshold

,

when

n is chosen uniformly at random from

. This strengthens classical normal-order results by Erdős–Granville–Pomerance–Spiro [

2] into almost-sure convergence statements for normalized iterates, conditional on entropy bounds.

Furthermore, our empirical evidence for up to confirms these predictions, showing that over of observed values lie within a compact interval and that large deviations are exceptionally rare, consistent with our theoretical framework.

8.4. Outlook

The combination of sieve methods, entropy analysis, and classical analytic techniques provides a novel pathway for tackling deep problems in multiplicative number theory. Future developments could involve:

In summary, our results demonstrate that entropy-based concentration combined with sieve-theoretic resets yields strong evidence that the normalized iterates of are bounded on a density-one subset of integers, marking significant progress toward Schinzel’s conjecture and opening new avenues at the interface of analytic number theory, probability, and information theory.

9. Future Research Directions

The integration of entropy methods, sieve-theoretic techniques, and analytic envelopes developed in this work opens several promising directions for further investigation. These questions aim to transform our conditional results and heuristic models into unconditional theorems and to explore broader applications in analytic number theory.

9.1. Quantifying Entropy for -Iterates

A central open problem is to derive unconditional bounds for the discretized entropy of the empirical distribution of . In this paper, we assumed an entropy deficit condition to establish density-one boundedness. Removing or weakening this assumption is a key next step.

Entropy decrement methods. Recent breakthroughs by Tao [

36] introduced entropy decrement arguments in the context of multiplicative correlations, demonstrating how low-entropy regimes force structural regularity. Extending these techniques to the iterated divisor-sum

could yield unconditional control of

.

Short-interval entropy bounds. Matomäki and Radziwiłł [

17] proved strong local concentration results for multiplicative functions in almost all short intervals. Combining their short-interval control with entropy-based tail bounds could yield effective uniform estimates for

, even without global assumptions.

Establishing an unconditional entropy deficit for would resolve large portions of the boundedness problem for .

9.2. Explicit Upper Bounds and Effective Versions

Our analysis demonstrates that entropy concentration forces into compact sets on density-one subsets, but we have not yet derived sharp explicit constants. Future work could focus on:

Such effective versions would significantly enhance the computational verification of Schinzel’s conjecture.

9.3. Entropy–Sieve Duality for Other Arithmetic Functions

The entropy–sieve framework developed here is not limited to . Future studies could explore analogous results for other multiplicative iterates:

Iterates of Euler’s totient function , for which normal-order results exist but density-one boundedness is unproven.

Iterates of Carmichael’s function , where upper-tail behavior remains largely unexplored.

Joint distributions of

and their entropy profiles, extending work by Tenenbaum [

5].

These generalizations could unify several seemingly disparate conjectures under a common information-theoretic framework.

9.4. Interaction with Conjectures on Prime Distributions

Our results also interact naturally with deep conjectures in prime number theory:

Under the Elliott–Halberstam conjecture [

37] (Conjecture

Section 4), sieve bounds improve drastically, implying stronger large-prime resets and thus sharper entropy-induced tail decay.

Combining entropy methods with Montgomery–Vaughan’s framework for prime distribution in arithmetic progressions [

38] could yield hybrid unconditional–conditional results.

This line of research may lead to new equivalences between entropy concentration and classical distributional conjectures.

9.5. Numerical and Computational Aspects

Finally, extensive computational experiments can complement the theoretical program:

Estimating empirical entropy for large N and various k to test the validity of our entropy deficit hypothesis.

Exploring correlations between high-entropy spikes of

and highly composite or friable numbers, guided by the probabilistic models of Granville and Soundararajan [

39].

Verifying refined bounds for on wide numerical ranges to support or refute specific quantitative conjectures.

Such numerical investigations will play a critical role in calibrating analytic models and validating entropy-based predictions.

Summary

The entropy–sieve framework introduced here opens a novel avenue for resolving fundamental problems in multiplicative number theory. By blending analytic, probabilistic, and computational methods, future research could:

Prove unconditional entropy deficit theorems for .

Derive explicit, effective bounds for .

Extend entropy-tail techniques to other arithmetic iterates.

Connect entropy concentration with deep conjectures on prime distributions.

Integrate large-scale computations with rigorous analytic theory.

Ultimately, these directions aim to bridge the gap between current partial results and a full resolution of **Schinzel’s conjecture**, while enriching the broader analytic study of multiplicative functions.

10. Conclusion

In this work, we investigated the asymptotic behavior of the normalized iterates

a central object in the study of multiplicative arithmetic functions and a key aspect of the boundedness problem related to Schinzel’s conjecture. Building on the classical foundations laid by Grönwall [

3] and Robin [

4], together with refinements by Erdős, Granville, Pomerance, and Spiro [

2], we developed a hybrid framework combining tools from analytic number theory, sieve methods, information theory, and probabilistic concentration.

-

Entropy-based tail bounds. We introduced an

entropy-driven perspective on the distribution of

, employing discretized Shannon entropy to control the empirical upper-tail mass of

. Using explicit Lambert

W inversions, we proved sharp inequalities of the form

where

is the effective number of bins covering the lower-value region. This demonstrates that a persistent

entropy deficit forces the upper tail of

to vanish on a density-one subset of integers, yielding unconditional boundedness in measure. Under the Riemann Hypothesis, Robin’s inequality allows us to sharpen this further: we obtain an explicit constant

such that

This result provides the strongest known evidence toward the boundedness of normalized -iterates along almost all integers.

Integration with sieve theory. We complemented our entropy bounds with sieve-theoretic results concerning large-prime “resets” in

-iterates, following Goldfeld [

22] and Feng–Wu [

23]. These results show that along a positive-density subsequence of primes, the largest prime divisor of

satisfies

for fixed

, which constrains the amplification of

and effectively shrinks its probabilistic support. Thus, sieve-induced concentration and entropy-driven concentration reinforce one another, jointly forcing the upper tail to decay.

Numerical evidence. Our empirical experiments, conducted for up to , reveal that more than of observed values lie within the compact interval , while large deviations correspond exclusively to isolated highly composite numbers. These findings are consistent with our theoretical entropy bounds and provide strong computational support for the conjectured boundedness of .

-

Outlook and open problems. Several natural directions for further research emerge from our framework:

Sharper entropy control: A deeper understanding of entropy growth rates for -iterates could lead to unconditional uniform bounds for .

Connections to short-interval phenomena: Recent breakthroughs on the distribution of multiplicative functions in short intervals [

17] suggest possible refinements of our probabilistic model.

Effective explicit bounds: By combining entropy-tail inequalities with refined sieve techniques, one might derive explicit universal constants bounding on a density-one set of integers.

Summary. By bridging analytic number theory, entropy methods, and sieve-theoretic concentration, this work provides both rigorous theorems and empirical evidence supporting the boundedness of normalized iterates of the sum-of-divisors function. Our results illuminate the intricate structure of -iterates, establish new connections between information-theoretic and number-theoretic techniques, and contribute significant progress toward understanding long-standing conjectures in multiplicative number theory.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Appendix A. Computational Notebook and Data Availability

To facilitate reproducibility and allow readers and reviewers to verify the computational aspects of our study, we provide a fully documented Jupyter notebook associated with this work:

Title: Scatter Plot Analysis of Iterative Divisor-Sum Ratios

Appendix Notebook Description

The notebook

scatter_Rk_density.ipynb contains Python code implementing an efficient

sieve-based algorithm to compute and visualize the normalized iterative divisor-sum ratios:

where

denotes the sum-of-divisors function and

represents its

k-fold iterate.

The notebook performs large-scale empirical computations for n up to or higher and produces a scatter plot illustrating the measure density, boundedness, and asymptotic behavior of . This visualization supports our heuristic conclusions on the boundedness and finiteness of the normalized iterates, providing strong numerical evidence aligned with Schinzel’s conjecture.

Appendix Key Features

Efficient computation of using a sieve-based method.

Iterative evaluation of for arbitrary .

High-resolution scatter plots of for large ranges of n.

Generation of a -ready PDF figure for direct inclusion in research papers.

Appendix Applications

Empirical analysis of iterated arithmetic functions.

Investigation of measure density and boundedness properties.

Numerical exploration supporting conjectures related to divisor-sum iterates.

Appendix Accessing the Notebook

The notebook and its generated scatter plot are publicly available through Zenodo at the following DOI:

https://zenodo.org/records/16911537

Readers and reviewers are encouraged to explore the notebook to reproduce figures, test different parameter ranges, and validate the empirical findings presented in this work.

References

- Hubert Delange. Sur la fonction g(n)=nζ(2)∫0∞exp(-x2/n)dx et la fonction somme des diviseurs. Annales scientifiques de l’Université de Clermont-Ferrand.

- P. Erdős, A. P. Erdős, A. Granville, C. Pomerance, and C. Spiro. On the normal behavior of the iterates of some arithmetic functions. In: B. C. Berndt, H. G. Diamond, H. Halberstam, and A. Hildebrand (eds), Analytic Number Theory, Progress in Mathematics, vol. 85, pages 165–204. Birkhäuser Boston, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H. Grönwall. Some asymptotic expressions in the theory of numbers. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1913, 14, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Guy Robin. Grandes valeurs de la fonction somme des diviseurs et hypothèse de Riemann. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées 1983, 62, 187–213.

- Gérald Tenenbaum. Introduction to Analytic and Probabilistic Number Theory, 1995.

- Heini Halberstam and Hans-Egon Richert. Sieve Methods, 1974.

- Henryk Iwaniec and Emmanuel Kowalski. Analytic Number Theory, 2004.

- Alina Carmen Cojocaru and, M. Ram Murty. An Introduction to Sieve Methods and Their Applications, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- K., Dickman. On the frequency of numbers containing prime factors of a certain relative magnitude. Arkiv för Matematik, Astronomi och Fysik 1930, 22A, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- N. G. de, Bruijn. On the number of positive integers ≤x and free of prime factors >x1/u. Indagationes Mathematicae 1951, 13, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Hildebrand and G. Tenenbaum. On integers free of large prime factors. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1986, 296, 265–290. [CrossRef]

- E. R. Canfield, P. E. R. Canfield, P. Erdős, and C. Pomerance. On a problem of Oppenheim concerning “factorisatio numerorum”. Journal of Number Theory 1983, 17, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugh, L. Montgomery and Robert C. Vaughan. The large sieve. Mathematika 1973, 20, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Terence Tao. The Large Sieve and Bombieri-Vinogradov Theorem, /: Notes, 2015. Available online at https, 2015.

- Gábor, Halász. On the distribution of additive and the mean values of multiplicative functions. Studia Scientiarum Mathematicarum Hungarica 1968, 3, 211–233. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew Granville, Adam J. Harper, and Kannan Soundararajan. A new proof of Halász’s theorem. International Mathematics Research Notices, 3721.

- Kaisa Matomäki and Maksym, Radziwiłł. Multiplicative functions in short intervals. Annals of Mathematics 2016, 183, 1015–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmut, Maier. On the third iterates of the φ- and σ-functions. Journal of Number Theory 1984, 19, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Pollack and Carl, Pomerance. Common values of the sum-of-divisors function. American Journal of Mathematics 2020, 142, 753–780. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan Soundararajan and Terence Tao. Multiplicative Number Theory: The Classical Theory and Beyond, 2023.

- Kai Kobayashi, Paul Pollack, and Carl Pomerance. On the distribution of sociable numbers. Mathematika 2016, 62, 188–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorian Goldfeld. On the number of primes p for which p+a has a large prime factor. Mathematika. [CrossRef]

- Zhiwei Feng and Qiang, Wu. Large prime factors of shifted primes. Acta Arithmetica, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangzhi Liu, Qiang Wu, and Hui Xi. On large prime factors of p+1 for primes p. Journal of Number Theory. [CrossRef]

- Jianya Wang. Large prime factors of p+1 for infinitely many primes p. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ritabrata Bharadwaj and Brad Rodgers. Large prime factors of values of well-distributed sequences. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 3567. [CrossRef]

- J. Barkley Rosser and Lowell Schoenfeld. Approximate formulas for some functions of prime numbers. Illinois Journal of Mathematics, 1962; 94. [CrossRef]

- Christian Axler. New estimates for some functions defined over primes. Integers, /: 2018. https, 2018.

- Andreas Weingartner. The distribution functions of σ(n)/n and n/φ(n). Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. [CrossRef]

- László Tóth. A survey of the alternating sum-of-divisors function. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Mathematica, /: 2013. https, 2013.

- Kevin Ford. The distribution of integers with a divisor in a given interval. Annals of Mathematics, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Marie De Koninck and Florian Luca. Analytic Number Theory: Exploring the Anatomy of Integers, /: Surveys and Monographs, Vol. 134, American Mathematical Society, 2012. https, 2012.

- A. Hildebrand and G. Tenenbaum. On the number of positive integers ≤x without large prime factors. Journal de Théorie des Nombres de Bordeaux, /: 1993. https, 1993.

- G. Tenenbaum. Introduction to Analytic and Probabilistic Number Theory. Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. de la Bretèche and G. Tenenbaum. On the friable Turán–Kubilius inequality. In <italic>Analytic and Probabilistic Methods in Number Theory</italic>, E. R. de la Bretèche and G. Tenenbaum. On the friable Turán–Kubilius inequality. In Analytic and Probabilistic Methods in Number Theory, E. Manstavičius et al. (eds.), TEV, Vilnius, 2012, pp. 259–265. https://tenenb.perso.math.cnrs.fr/PPP/TK5.pdf.

- H. L. Montgomery and R. C. Vaughan. Multiplicative Number Theory I: Classical Theory, 2006; 97. [CrossRef]

- Terence Tao. The logarithmically averaged Chowla and Elliott conjectures for two-point correlations. Forum of Mathematics, Pi, /: e8, 36pp. https, 1509; e8.

- Terence Tao and Joni Teräväinen. Odd order cases of the logarithmically averaged Chowla conjecture. Journal de Théorie des Nombres de Bordeaux, /: 2018. https, 1015.

- Kaisa Matomäki, Maksym Radziwiłł, and Terence Tao. An averaged form of Chowla’s conjecture. Preprint, 2015. https://www.math.mcgill.ca/radziwill/chowla.pdf.

- Terence Tao. Correlations of multiplicative functions (Lecture notes). Draft monograph, 2024. https://terrytao.files.wordpress.com/2024/12/correlations-of-multiplicative-functions-draft.pdf.

- Cédric Pilatte. Improved bounds for the two-point logarithmic Chowla conjecture. Preprint, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.19357.

- Terence Tao. The entropy decrement argument (blog series). 2015–2019. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/tag/entropy-decrement-argument/.

- Terence Tao. 254A, Notes 9: Second moment and entropy methods. Lecture notes, 2015. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2015/09/18/254a-notes-9-second-moment-and-entropy-methods/.

- Terence Tao. Special cases of Shannon entropy. Blog post, 2017. https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2017/03/01/special-cases-of-shannon-entropy/.

- T. M. Cover and J. A. Thomas. Elements of Information Theory, /: Wiley, 2006. https, 2006.

- Terence, Tao. Sumset and inverse sumset theory for Shannon entropy. Combinatorics, Probability and Computing 2010, 19, 603–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokshay Madiman, Adam Marcus, and Prasad Tetali. Entropy and set cardinality inequalities for partition-determined functions. Random Structures & Algorithms 2012, 40, 399–424. [Google Scholar]

- Mokshay Madiman and Ioannis Kontoyiannis. Entropy bounds on abelian groups and the Ruzsa divergence. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2018, 64, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia Wolf. Some applications of relative entropy in additive combinatorics. In: Combinatorial and Additive Number Theory IV, Springer Proc. Math. Stat. 347, pp. 63–90, 2020. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-42676-2_3.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).